- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- *New* Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

5 Examples of Corporate Social Responsibility That Were Successful

- 06 Jun 2019

Business is about more than just making a profit. Climate change, economic inequality, and other global challenges that impact communities worldwide have compelled companies to be purpose-driven and contribute to the greater good .

In a recent study by Deloitte , 93 percent of business leaders said they believe companies aren't just employers, but stewards of society. In addition, 95 percent reported they’re planning to take a stronger stance on large-scale issues in the coming years and devote significant resources to socially responsible initiatives. With more CEOs turning their focus to the long term, it’s important to consider what you can do in your career to make an impact .

Access your free e-book today.

What Is Corporate Social Responsibility?

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is a business model in which for-profit companies seek ways to create social and environmental benefits while pursuing organizational goals, like revenue growth and maximizing shareholder value .

Today’s organizations are implementing extensive corporate social responsibility programs, with many companies dedicating C-level executive roles and entire departments to social and environmental initiatives. These executives are commonly referred to as a chief officer of corporate social responsibility or chief sustainability officer (CSO).

There are many types of corporate social responsibility and CSR might look different for each organization, but the end goal is always the same: Do well by doing good . Companies that embrace corporate social responsibility aim to maintain profitability while supporting a larger purpose.

Rather than simply focusing on generating profit, or the bottom line, socially responsible companies are concerned with the triple bottom line , which considers the impact that business decisions have on profit, people, and the planet.

It’s no coincidence that some of today’s most profitable organizations are also socially responsible. Here are five examples of successful corporate social responsibility you can use to drive social change at your organization.

5 Corporate Social Responsibility Examples

1. lego’s commitment to sustainability.

As one of the most reputable companies in the world, Lego aims to not only help children develop through creative play, but foster a healthy planet.

Lego is the first, and only, toy company to be named a World Wildlife Fund Climate Savers Partner , marking its pledge to reduce its carbon impact. And its commitment to sustainability extends beyond its partnerships.

By 2030, the toymaker plans to use environmentally friendly materials to produce all of its core products and packaging—and it’s already taken key steps to achieve that goal.

Over the course of 2013 and 2014, Lego shrunk its box sizes by 14 percent , saving approximately 7,000 tons of cardboard. Then, in 2018, the company introduced 150 botanical pieces made from sustainably sourced sugarcane —a break from the petroleum-based plastic typically used to produce the company’s signature building blocks. The company has also recently committed to removing all single-use plastic packaging from its materials by 2025, among other initiatives .

Along with these changes, the toymaker has committed to investing $164 million into its Sustainable Materials Center , where researchers are experimenting with bio-based materials that can be implemented into the production process.

Through all of these initiatives, Lego is well on its way to tackling pressing environmental challenges and furthering its mission to help build a more sustainable future.

Related : What Does "Sustainability" Mean in Business?

2. Salesforce’s 1-1-1 Philanthropic Model

Beyond being a leader in the technology space, cloud-based software giant Salesforce is a trailblazer in the realm of corporate philanthropy.

Since its outset, the company has championed its 1-1-1 philanthropic model , which involves giving one percent of product, one percent of equity, and one percent of employees’ time to communities and the nonprofit sector.

To date, Salesforce employees have logged more than 5 million volunteer hours . Not only that, but the company has awarded upwards of $406 million in grants and donated to more than 40,000 nonprofit organizations and educational institutions.

In addition, through its work with San Francisco Unified and Oakland Unified School Districts, Salesforce has helped reduce algebra repeat rates and contributed to a high percentage of students receiving A’s or B’s in computer science classes.

As the company’s revenue continues to grow, Salesforce stands as a prime example of the idea that profit-making and social impact initiatives don’t have to be at odds with one another.

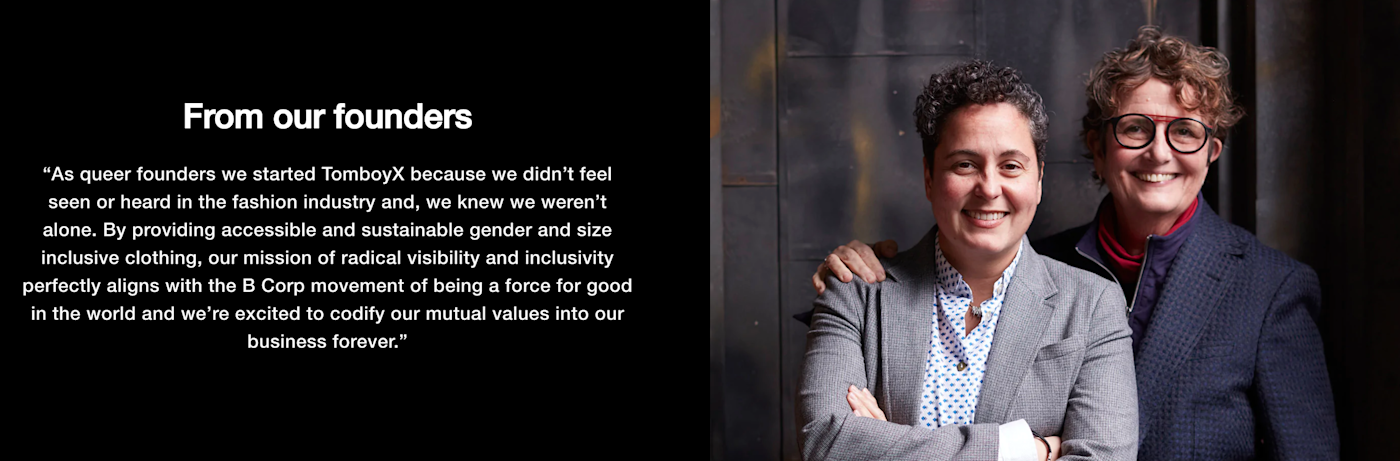

3. Ben & Jerry’s Social Mission

At Ben & Jerry’s, positively impacting society is just as important as producing premium ice cream.

In 2012, the company became a certified B Corporation , a business that balances purpose and profit by meeting the highest standards of social and environmental performance, public transparency, and legal accountability.

As part of its overarching commitment to leading with progressive values, the ice cream maker established the Ben & Jerry’s Foundation in 1985, an organization dedicated to supporting grassroots movements that drive social change.

Each year, the foundation awards approximately $2.5 million in grants to organizations in Vermont and across the United States. Grant recipients have included the United Workers Association, a human rights group striving to end poverty, and the Clean Air Coalition, an environmental health and justice organization based in New York.

The foundation’s work earned it a National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy Award in 2014, and it continues to sponsor efforts to find solutions to systemic problems at both local and national levels.

Related : How to Create Social Change: 4 Business Strategies

4. Levi Strauss’s Social Impact

In addition to being one of the most successful fashion brands in history, Levi’s is also one of the first to push for a more ethical and sustainable supply chain.

In 1991, the brand created its Terms of Engagement , which established its global code of conduct regarding its supply chain and set standards for workers’ rights, a safe work environment, and an environmentally-friendly production process.

To maintain its commitment in a changing world, Levi’s regularly updates its Terms of Engagement. In 2011, on the 20th anniversary of its code of conduct, Levi’s announced its Worker Well-being initiative to implement further programs focused on the health and well-being of supply chain workers.

Since 2011, the Worker Well-being initiative has been expanded to 12 countries and more than 100,000 workers have benefited from it. In 2016, the brand scaled up the initiative, vowing to expand the program to more than 300,000 workers and produce more than 80 percent of its product in Worker Well-being factories by 2025.

For its continued efforts to maintain the well-being of its people and the environment, Levi’s was named one of Engage for Good’s 2020 Golden Halo Award winners, which is the highest honor reserved for socially responsible companies.

5. Starbucks’s Commitment to Ethical Sourcing

Starbucks launched its first corporate social responsibility report in 2002 with the goal of becoming as well-known for its CSR initiatives as for its products. One of the ways the brand has fulfilled this goal is through ethical sourcing.

In 2015, Starbucks verified that 99 percent of its coffee supply chain is ethically sourced , and it seeks to boost that figure to 100 percent through continued efforts and partnerships with local coffee farmers and organizations.

The brand bases its approach on Coffee and Farmer Equity (CAFE) Practices , one of the coffee industry’s first set of ethical sourcing standards created in collaboration with Conservation International . CAFE assesses coffee farms against specific economic, social, and environmental standards, ensuring Starbucks can source its product while maintaining a positive social impact.

For its work, Starbucks was named one of the world’s most ethical companies in 2021 by Ethisphere.

The Value of Being Socially Responsible

As these firms demonstrate , a deep and abiding commitment to corporate social responsibility can pay dividends. By learning from these initiatives and taking a values-driven approach to business, you can help your organization thrive and grow, even as it confronts global challenges.

Do you want to gain a deeper understanding of the broader social and political landscape in which your organization operates? Explore our three-week Sustainable Business Strategy course and other online courses regarding business in society to learn more about how business can be a catalyst for system-level change.

This post was updated on April 15, 2022. It was originally published on June 6, 2019.

About the Author

- Contributors

The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility

Matteo Tonello is Director of Corporate Governance for The Conference Board, Inc. This post is based on a Conference Board Director Note by Archie B. Carroll and Kareem M. Shabana , and relates to a paper by these authors, titled “The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review of Concepts, Research and Practice,” published in the International Journal of Management Reviews .

In the last decade, in particular, empirical research has brought evidence of the measurable payoff of corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives to companies as well as their stakeholders. Companies have a variety of reasons for being attentive to CSR. This report documents some of the potential bottomline benefits: reducing cost and risk, gaining competitive advantage, developing and maintaining legitimacy and reputational capital, and achieving win-win outcomes through synergistic value creation.

The term “corporate social responsibility” is still widely used even though related concepts, such as sustainability, corporate citizenship, business ethics, stakeholder management, corporate responsibility, and corporate social performance, are vying to replace it. In different ways, these expressions refer to the ensemble of policies, practices, investments, and concrete results deployed and achieved by a business corporation in the pursuit of its stakeholders’ interests.

This report discusses the business case for CSR—that is, what justifies the allocation of resources by the business community to advance a certain socially responsible cause. The business case is concerned with the following question: what tangible benefits do business organizations reap from engaging in CSR initiatives? This report reviews the most notable research on the topic and provides practical examples of CSR initiatives that are also good for the business and its bottom line.

The Search for a Business Case: A Shift in Perspective

Business management scholars have been searching for a business case for CSR since the origins of the concept in the 1960s. [1]

An impetus for the research questions for this report was philosophical. It had to do with the long-standing divide between those who, like the late economist Milton Friedman, believed that the corporation should pursue only its shareholders’ economic interests and those who conceive the business organization as a nexus of relations involving a variety of stakeholders (employees, suppliers, customers, and the community where the company operates) without which durable shareholder value creation is impossible. If it could be demonstrated that businesses actually benefited financially from a CSR program designed to cultivate such a range of stakeholder relations, the thinking of the latter school went, then Friedman’s arguments would somewhat be neutralized.

Another impetus to research on the business case of CSR was more pragmatic. Even though CSR came about because of concerns about businesses’ detrimental impacts on society, the theme of making money by improving society has also always been in the minds of early thinkers and practitioners: with the passage of time and the increase in resources being dedicated to CSR pursuits, it was only natural that questions would begin to be raised about whether CSR was making economic sense.

Obviously, corporate boards, CEOs, CFOs, and upper echelon business executives care. They are the guardians of companies’ financial well-being and, ultimately, must bear responsibility for the impact of CSR on the bottom line. At multiple levels, executives need to justify that CSR is consistent with the firm’s strategies and that it is financially sustainable. [a]

However, other groups care as well. Shareholders are acutely concerned with financial performance and sensitive to possible threats to management’s priorities. Social activists care because it is in their long-term best interests if companies can sustain the types of social initiatives that they are advocating. Governmental bodies care because they desire to see whether companies can deliver social and environmental benefits more cost effectively than they can through regulatory approaches. [b] Consumers care as well, as they want to pass on a better world to their children, and many want their purchasing to reflect their values.

[a] K. O’Sullivan, “Virtue rewarded: companies are suddenly discovering the profit potential of social responsibility.” CFO , October 2006, pp. 47–52.

[b] Simon Zadek. Doing Good and Doing Well: Making the Business Case for Corporate Citizenship . New York: The Conference Board Research Report, 2000, 1282-00-RR.

The socially responsible investment movement Establishing a positive relationship between corporate social performance (CSP) and corporate financial performance (CFP) has been a long-standing pursuit of researchers. This endeavor has been described as a “30-year quest for an empirical relationship between a corporation’s social initiatives and its financial performance.” [2] One comprehensive review and assessment of studies exploring the CSP-CFP relationship concludes that there is a positive relationship between CSP and CFP. [3]

In response to this empirical evidence, in the last decade the investment community, in particular, has witnessed the growth of a cadre of socially responsible investment funds (SRI), whose dedicated investment strategy is focused on businesses with a solid track record of CSR-oriented initiatives. Today, the debate on the business case for CSR is clearly influenced by these new market trends: to raise capital, these players promote the belief of a strong correlation between social and financial performance. [4]

As the SRI movement becomes more influential, CSR theories are shifting away from an orientation on ethics (or altruistic rationale) and embracing a performance-driven orientation. In addition, analysis of the value generated by CSR has moved from the macro to the organizational level, where the effects of CSR on firm financial performance are directly experienced. [5]

The CSR of the 1960s and 1970s was motivated by social considerations, not economic ones. “While there was substantial peer pressure among corporations to become more philanthropic, no one claimed that such firms were likely to be more profitable than their less generous competitors.” In contrast, the essence of the new world of CSR is “doing good to do well.” [6]

CSR is evolving into a core business function, central to the firm’s overall strategy and vital to its success. [7] Specifically, CSR addresses the question: “can companies perform better financially by addressing both their core business operations as well as their responsibilities to the broader society?” [8]

One Business Case Just Won’t Do

There is no single CSR business case—no single rationalization for how CSR improves the bottom line. Over the years, researchers have developed many arguments. In general, these arguments can be grouped based on approach, topics addressed, and underlying assumptions about how value is created and defined. According to this categorization, CSR is a viable business choice as it is a tool to:

- implement cost and risk reductions;

- gain competitive advantage;

- develop corporate reputation and legitimacy; and

- seek win-win outcomes through synergistic value creation. [9]

Other widely accepted approaches substantiating the business case include focusing on the empirical research linking CSR with corporate social performance (CSP) and identifying values brought to different stakeholder groups that directly or indirectly benefit the company’s bottom lines.

Broad versus narrow views Some researchers have examined the integration of CSR considerations in the day-to-day business agenda of organizations. The “mainstreaming” of CSR follows from one of three rationales:

- the social values-led model, in which organizations adopt CSR initiatives regarding specific issues for non-economic reasons;

- the business-case model, in which CSR initiatives are primarily assessed in an economic manner and pursued only when there is a clear link to firm financial performance [10] ; and

- the syncretic stewardship model, which combines the social values-led and the business-case models.

The business case model and the syncretic models may be seen as two perspectives of the business case for CSR: one narrow and one broad. The business case model represents the narrow view: CSR is only recognized when there is a clear link to firm financial performance. The syncretic model is broad because it recognizes both direct and indirect relationships between CSR and firm financial performance. The advantage of the broad view is that it enables the firm to identify and exploit opportunities beyond the financial, opportunities that the narrow view would not be able to recognize or justify.

Another advantage of the broad view of the business case, which is illustrated by the syncretic model, is its recognition of the interdependence between business and society. [11]

The failure to recognize such interdependence in favor of pitting business against society leads to reducing the productivity of CSR initiatives. “The prevailing approaches to CSR are so fragmented and so disconnected from business and strategy as to obscure many of the greatest opportunities for companies to benefit society.” [12] The adoption of CSR practices, their integration with firm strategy, and their mainstreaming in the day-to-day business agenda should not be done in a generic manner. Rather, they should be pursued “in the way most appropriate to each firm’s strategy.” [13]

In support of the business case for CSR, the next sections of the report discuss examples of the effect of CSR on firm performance. The discussion is organized according to the framework referenced earlier, which identifies four categories of benefits that firms may attain from engaging in CSR activities. [14]

Reducing Costs and Risks

Cost and risk reduction justifications contend that engaging in certain CSR activities will reduce the firm’s inefficient capital expenditures and exposure to risks. “[T]he primary view is that the demands of stakeholders present potential threats to the viability of the organization, and that corporate economic interests are served by mitigating the threats through a threshold level of social or environmental performance.” [15]

Equal employment opportunity policies and practices CSR activities in the form of equal employment opportunity (EEO) policies and practices enhance long-term shareholder value by reducing costs and risks. The argument is that explicit EEO statements are necessary to illustrate an inclusive policy that reduces employee turnover through improving morale. [16] This argument is consistent with those who observe that “[l]ack of diversity may cause higher turnover and absenteeism from disgruntled employees.” [17]

Energy-saving and other environmentally sound production practices Cost and risk reduction may also be achieved through CSR activities directed at the natural environment. Empirical research shows that being environmentally proactive results in cost and risk reduction. Specifically, data shows hat “being proactive on environmental issues can lower the costs of complying with present and future environmental regulations … [and] … enhance firm efficiencies and drive down operating costs.” [18]

Community relations management Finally, CSR activities directed at managing community relations may also result in cost and risk reductions. [19] For example, building positive community relationships may contribute to the firm’s attaining tax advantages offered by city and county governments to further local investments. In addition, positive community relationships decrease the number of regulations imposed on the firm because the firm is perceived as a sanctioned member of society.

Cost and risk reduction arguments for CSR have been gaining wide acceptance among managers and executives. In a survey of business executives by PricewaterhouseCoopers, 73 percent of the respondents indicated that “cost savings” was one of the top three reasons companies are becoming more socially responsible. [20]

Gaining Competitive Advantage

As used in this section of the report, the term “competitive advantage” is best understood in the context of a differentiation strategy; in other words, the focus is on how firms may use CSR practices to set themselves apart from their competitors. The previous section, which focused on cost and risk reduction, illustrated how CSR practices may be thought of in terms of building a competitive advantage through a cost management strategy. “Competitive advantages” was cited as one of the top two justifications for CSR in a survey of business executives reported in a Fortune survey. [21] In this context, stakeholder demands are seen as opportunities rather than constraints. Firms strategically manage their resources to meet these demands and exploit the opportunities associated with them for the benefit of the firm. [22] This approach to CSR requires firms to integrate their social responsibility initiatives with their broader business strategies.

Reducing costs and risks • Equal employment opportunity policies and practices • Energy-saving and other environmentally sound production practices • Community relations management

Gaining competitive advantage • EEO policies • Customer relations program • Corporate philanthropy

Developing reputation and legitimacy • Corporate philanthropy • Corporate disclosure and transparency practices

Seeking win-win outcomes through synergistic value creation • Charitable giving to education • Stakeholder engagement

EEO policies Companies that build their competitive advantage through unique CSR strategies may have a superior advantage, as the uniqueness of their CSR strategies may serve as a basis for setting the firm apart from its competitors. [23] For example, an explicit statement of EEO policies would have additional benefits to the cost and risk reduction discussed earlier in this report. Such policies would provide the firm with a competitive advantage because “[c]ompanies without inclusive policies may be at a competitive disadvantage in recruiting and retaining employees from the widest talent pool.” [24]

Customer and investor relations programs CSR initiatives can contribute to strengthening a firm’s competitive advantage, its brand loyalty, and its consumer patronage. CSR initiatives also have a positive impact on attracting investment. Many institutional investors “avoid companies or industries that violate their organizational mission, values, or principles… [They also] seek companies with good records on employee relations, environmental stewardship, community involvement, and corporate governance.” [25]

Corporate philanthropy Companies may align their philanthropic activities with their capabilities and core competencies. “In so doing, they avoid distractions from the core business, enhance the efficiency of their charitable activities and assure unique value creation for the beneficiaries.” [26] For example, McKinsey & Co. offers free consulting services to nonprofit organizations in social, cultural, and educational fields. Beneficiaries include public art galleries, colleges, and charitable institutions. [27] Home Depot Inc. provided rebuilding knowhow to the communities victimized by Hurricane Katrina. Strategic philanthropy helps companies gain a competitive advantage and in turn boosts its bottom line. [28]

CSR initiatives enhance a firm’s competitive advantage to the extent that they influence the decisions of the firm’s stakeholders in its favor. Stakeholders may prefer a firm over its competitors specifically due to the firm’s engagement in such CSR initiatives.

Developing Reputation and Legitimacy

Companies may also justify their CSR initiatives on the basis of creating, defending, and sustaining their legitimacy and strong reputations. A business is perceived as legitimate when its activities are congruent with the goals and values of the society in which the business operates. In other words, a business is perceived as legitimate when it fulfills its social responsibilities. [29]

As firms demonstrate their ability to fit in with the communities and cultures in which they operate, they are able to build mutually beneficial relationships with stakeholders. Firms “focus on value creation by leveraging gains in reputation and legitimacy made through aligning stakeholder interests.” [30] Strong reputation and legitimacy sanction the firm to operate in society. CSR activities enhance the ability of a firm to be seen as legitimate in the eyes of consumers, investors, and employees. Time and again, consumers, employees, and investors have shown a distinct preference for companies that take their social responsibilities seriously. A Center for Corporate Citizenship study found that 66 percent of executives thought their social responsibility strategies resulted in improving corporate reputation and saw this as a business benefit. [31]

Corporate philanthropy Corporate philanthropy may be a tool of legitimization. Firms that have negative social performance in the areas of environmental issues and product safety use charitable contributions as a means for building their legitimacy. [32]

Corporate disclosure and transparency practices Corporations have also enhanced their legitimacy and reputation through the disclosure of information regarding their performance on different social and environmental issues, sometimes referred to as sustainability reporting. Corporate social reporting refers to stand-alone reports that provide information regarding a company’s economic, environmental, and social performance. The practice of corporate social reporting has been encouraged by the launch of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) in 1997-1998 and the introduction of the United Nations Global Compact in 1999. Through social reporting, firms can document that their operations are consistent with social norms and expectations, and, therefore, are perceived as legitimate.

Seeking Win-Win Outcomes through Synergistic Value Creation

Synergistic value creation arguments focus on exploiting opportunities that reconcile differing stakeholder demands. Firms do this by “connecting stakeholder interests, and creating pluralistic definitions of value for multiple stakeholders simultaneously.” [33] In other words, with a cause big enough, they can unite many potential interest groups.

Charitable giving to education When companies get the “where” and the “how” right, philanthropic activities and competitive advantage become mutually reinforcing and create a virtuous circle. Corporate philanthropy may be used to influence the competitive context of an organization, which allows the organization to improve its competitiveness and at the same time fulfill the needs of some of its stakeholders. For example, in the long run, charitable giving to education improves the quality of human resources available to the firm. Similarly, charitable contributions to community causes eventually result in the creation and preservation of a higher quality of life, which may sustain “sophisticated and demanding local customers.” [34]

The notion of creating win-win outcomes through CSR activities has been raised before. Management expert Peter Drucker argues that “the proper ‘social responsibility’ of business is to … turn a social problem into economic opportunity and economic benefit, into productive capacity, into human competence, into well-paid jobs, and into wealth.” [35] It has been argued that, “it will not be too long before we can begin to assert that the business of business is the creation of sustainable value— economic, social and ecological.” [36]

An example: the win-win perspective adopted by the life sciences firm Novo Group allowed it to pursue its business “[which] is deeply involved in genetic modification and yet maintains highly interactive and constructive relationships with stakeholders and publishes a highly rated environmental and social report each year.” [37]

Stakeholder engagement The win-win perspective on CSR practices aims to satisfy stakeholders’ demands while allowing the firm to pursue financial success. By engaging its stakeholders and satisfying their demands, the firm finds opportunities for profit with the consent and support of its stakeholder environment.

The business case for corporate social responsibility can be made. While it is valuable for a company to engage in CSR for altruistic and ethical justifications, the highly competitive business world in which we live requires that, in allocating resources to socially responsible initiatives, firms continue to consider their own business needs.

In the last decade, in particular, empirical research has brought evidence of the measurable payoff of CSR initiatives on firms as well as their stakeholders. Firms have a variety of reasons for being CSR-attentive. But beyond the many bottom-line benefits outlined here, businesses that adopt CSR practices also benefit our society at large.

[1] See Edward Freeman, Strategic Management: a Stakeholder Approach , 1984, which traces the roots of CSR to the 1960s and 1970s, when many multinationals were formed. (go back)

[2] J. D. Margolis and Walsh, J.P. “Misery loves companies: social initiatives by business.” Administrative Science Quarterly , 48, 2003, pp. 268–305. (go back)

[3] J. F. Mahon and Griffin, J .J. “Painting a portrait: a reply.” Business and Society , 38, 1999, 126–133. (go back)

[4] See, for an overview, Stephen Gates, Jon Lukomnik, and David Pitt- Watson, The New Capitalists: How Citizen Investors Are Reshaping The Business Agenda , Harvard Business School Press, 2006. (go back)

[5] M.P. Lee, “A review of the theories of corporate social responsibility: its evolutionary path and the road ahead”. International Journal of Management Reviews , 10, 2008, 53–73. (go back)

[6] D.J. Vogel, “Is there a market for virtue? The business case for corporate social responsibility.” California Management Review , 47, 2005, pp. 19–45. (go back)

[7] Ibid. (go back)

[8] Elizabeth Kurucz; Colbert, Barry; and Wheeler, David “The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility.” Chapter 4 in Crane, A.; McWilliams, A.; Matten, D.; Moon, J. and Siegel, D. The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008, 83-112 (go back)

[9] Kurucz, Colbert, and Wheeler , 85-92. (go back)

[10] Berger,I.E., Cunningham, P. and Drumwright, M.E. “Mainstreaming corporate and social responsibility: developing markets for virtue,” California Management Review , 49, 2007, 132-157. (go back)

[11] Ibid. (go back)

[12] M.E. Porter and Kramer, M.R. “Strategy & society: the link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility.” Harvard Business Review , 84, 2006,pp. 78–92. (go back)

[13] Ibid. (go back)

[14] Kurucz, Colbert, and Wheeler, 85-92. (go back)

[15] Ibid., 88. (go back)

[16] T. Smith, “Institutional and social investors find common ground. Journal of Investing , 14, 2005, 57–65. (go back)

[17] S. L. Berman, Wicks, A.C., Kotha, S. and Jones, T.M. “Does stakeholder orientation matter? The relationship between stakeholder management models and firm financial performance.” Academy of Management Journal , 42, 1999, 490. (go back)

[18] Ibid. (go back)

[19] Ibid. (go back)

[20] Top 10 Reasons, PricewaterhouseCoopers 2002 Sustainability Survey Report, reported in “Corporate America’s Social Conscience,” Fortune , May 26, 2003, 58. (go back)

[21] Top 10 Reasons . (go back)

[22] Kurucz, Colbert, and Wheeler (go back)

[23] N. Smith, 2003, 67. (go back)

[24] T. Smith, 2005, 60. (go back)

[25] Ibid., 64. (go back)

[26] Heike Bruch and Walter, Frank (2005). “The Keys to Rethinking Corporate Philanthropy.” MIT Sloan Management Review , 47(1): 48-56 (go back)

[27] Ibid., 50. (go back)

[28] Bruce Seifert, Morris, Sara A.; and Bartkus, Barbara R. (2003). “Comparing Big Givers and Small Givers: Financial Correlates of Corporate Philanthropy.” Journal of Business Ethics , 45(3): 195-211. (go back)

[29] Archie B. Carroll and Ann K. Buchholtz, Business and Society: Ethics, Sustainability and Stakeholder Management , 8th Edition, Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning, 2012, 305. (go back)

[30] Kurucz, Colbert, and Wheeler, 90. (go back)

[31] “Managing Corporate Citizenship as a Business Strategy,” Boston: Center for Corporate Citizenship, 2010. (go back)

[32] Jennifer C. Chen, Dennis M.; & Roberts, Robin. “Corporate Charitable Contributions: A Corporate Social Performance or Legitimacy Strategy?” Journal of Business Ethics , 2008, 131-144. (go back)

[33] Kurucz, Colbert, and Wheeler , 91. (go back)

[34] Porter and Kramer, 60-65. (go back)

[35] Peter F. Drucker, “The New Meaning of Corporate Social Responsibility.” California Management Review , 1984, 26: 53-63 (go back)

[36] C. Wheeler, B. Colbert, and R. E. Freeman. “Focusing on Value: Reconciling Corporate Social Responsibility, Sustainability and a Stakeholder Approach in a Network World.” Journal of General Management , (28)3, 2003, 1-28. (go back)

[37] Ibid. (go back)

Nice blog. CSR has become something very important to all the corporate houses today. However, with the rising growth of CSR activities. It is very important to have an effective software that helps to keep a track of the entire exercise.

Interesting article! Perhaps nice to give Mr. Stephen ‘Gates’ his real name back? After all “The New Capitalists: How Citizen Investors Are Reshaping The Business Agenda” was written by Stephen DAVIS. I think he would like the recognition ;)

5 Trackbacks

[…] original here: The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility — The … This entry was posted in Internet and tagged corporate, corporate-governance, corporate-social, […]

[…] For the entire article, read it here. […]

[…] http://blogs.law.harvard.edu/corpgov/2011/06/26/the-business-case-for-corporate-social-responsibilit … […]

[…] (CSR) and the behavior change awareness/advertising campaigns associated with them. Here is a terrific article in the Harvard Law School Forum that outlines the business benefits gained from CSR initiatives. […]

[…] guru Peter Drucker agreed that business has to make enough profit to secure its future, but insisted that its proper […]

Supported By:

Subscribe or Follow

Program on corporate governance advisory board.

- William Ackman

- Peter Atkins

- Kerry E. Berchem

- Richard Brand

- Daniel Burch

- Arthur B. Crozier

- Renata J. Ferrari

- John Finley

- Carolyn Frantz

- Andrew Freedman

- Byron Georgiou

- Joseph Hall

- Jason M. Halper

- David Millstone

- Theodore Mirvis

- Maria Moats

- Erika Moore

- Morton Pierce

- Philip Richter

- Marc Trevino

- Steven J. Williams

- Daniel Wolf

HLS Faculty & Senior Fellows

- Lucian Bebchuk

- Robert Clark

- John Coates

- Stephen M. Davis

- Allen Ferrell

- Jesse Fried

- Oliver Hart

- Howell Jackson

- Kobi Kastiel

- Reinier Kraakman

- Mark Ramseyer

- Robert Sitkoff

- Holger Spamann

- Leo E. Strine, Jr.

- Guhan Subramanian

- Roberto Tallarita

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

CorporateSocialResponsibilityandImpact →

No results found in working knowledge.

- Were any results found in one of the other content buckets on the left?

- Try removing some search filters.

- Use different search filters.

MBA Knowledge Base

Business • Management • Technology

Home » Management Case Studies » Case Study: Corporate Social Responsibility of Starbucks

Case Study: Corporate Social Responsibility of Starbucks

Starbucks is the world’s largest and most popular coffee company. Since the beginning, this premier cafe aimed to deliver the world’s finest fresh-roasted coffee. Today the company dominates the industry and has created a brand that is tantamount with loyalty, integrity and proven longevity. Starbucks is not just a name, but a culture .

It is obvious that Starbucks and their CEO Howard Shultz are aware of the importance of corporate social responsibility . Every company has problems they can work on and improve in and so does Starbucks. As of recent, Starbucks has done a great job showing their employees how important they are to the company. Along with committing to every employee, they have gone to great lengths to improve the environment for everyone. Ethical and unethical behavior is always a hot topic for the media, and Starbucks has to be careful with the decisions they make and how they affect their public persona.

The corporate social responsibility of the Starbucks Corporation address the following issues: Starbucks commitment to the environment, Starbucks commitment to the employees, Starbucks commitment to consumers, discussions of ethical and unethical business behavior, and Starbucks commitment and response to shareholders.

Commitment to the Environment

The first way Starbucks has shown corporate social responsibility is through their commitment to the environment. In order to improve the environment, with a little push from the NGO, Starbucks first main goal was to provide more Fair Trade Coffee. What this means is that Starbucks will aim to only buy 100 percent responsibly grown and traded coffee. Not only does responsibly grown coffee help the environment, it benefits the farmers as well. Responsibly grown coffee means preserving energy and water at the farms. In turn, this costs more for the company overall, but the environmental improvements are worth it. Starbucks and the environment benefits from this decision because it helps continue to portray a clean image.

Another way to improve the environment directly through their stores is by “going green”. Their first attempt to produce a green store was in Manhattan. Starbucks made that decision to renovate a 15 year old store. This renovation included replacing old equipment with more energy efficient ones. To educate the community, they placed plaques throughout the store explaining their new green elements and how they work. This new Manhattan store now conserves energy, water, materials, and uses recycled/recyclable products. Twelve stores total plan to be renovated and Starbucks has promised to make each new store LEED, meaning a Leader in Energy and Environmental Design. LEED improves performance regarding energy savings, water efficiency, and emission reduction. Many people don’t look into environmentally friendly appliances because the upfront cost is always more. According to Starbucks, going green over time outweighs the upfront cost by a long shot. Hopefully, these new design elements will help the environment and get Starbucks ahead of their market.

Commitment to Consumers

The second way Starbucks has shown corporate social responsibility is through their commitment to consumers. The best way to get the customers what they want is to understand their demographic groups. By doing research on Starbucks consumer demographics, they realized that people with disabilities are very important. The company is trying to turn stores into a more adequate environment for customers with disabilities. A few changes include: lowering counter height to improve easy of ordering for people in wheelchairs, adding at least one handicap accessible entrance, adding disability etiquette to employee handbooks, training employees to educate them on disabilities, and by joining the National Business Disability Council. By joining the National Business Disability Council, Starbucks gains access to resumes of people with disabilities.

Another way Starbucks has shown commitment to the consumers is by cutting costs and retaining loyal customers. For frequent, loyal customers, Starbucks decided to provide a loyalty card. Once a customer has obtained this card, they are given incentives and promotions for continuing to frequent their stores. Promotions include discounted drinks and free flavor shots to repeat visitors. Also, with the economy being at an all time low, Starbucks realized that cheaper prices were a necessity. By simplifying their business practices, they were able to provide lower prices for their customers. For example, they use only one recipe for banana bread, rather than eleven!

It doesn’t end there either! Starbucks recognized that health is part of social responsibility. To promote healthier living, they introduced “skinny” versions of most drinks, while keeping the delicious flavor. For example, the skinny vanilla latte has 90 calories compared to the original with 190 calories. Since Starbucks doesn’t just sell beverages now, they introduced low calorie snacks. Along with the snacks and beverages, nutrition facts were available for each item.

Also one big way to cut costs was outsourcing payroll and Human Resources administration . By creating a global platform for their administration system, Starbucks is able to provide more employees with benefits. Plus, they are able to spend more money on pleasing customers, rather than on a benefits system.

Commitment and Response to Shareholders

One way Starbucks has demonstrated their commitment and response to shareholder needs is by giving them large portions. By large portions, Starbucks is implying that they plan pay dividends equal to 35% or higher of net income to. For the shareholders, paying high dividends means certainty about the company’s financial well-being. Along with that, they plan to purchase 15 million more shares of stock, and hopefully this will attract investors who focus on stocks with good results.

Starbucks made their commitment to shareholders obvious by speaking directly to the media about it. In 2004, Starbucks won a great tax break, but unfortunately the media saw them as “money grubbing”. Their CEO, Howard Shultz, made the decision to get into politics and speak to Washington about expanding health care and the importance of this to the company. Not only does he want his shareholders to see his commitment, but he wants all of America to be able to reap this benefits.

In order to compete with McDonalds and keeping payout to their shareholders high, Starbucks needed a serious turnaround . They did decide to halt growth in North America but not in Japan. Shultz found that drinking coffee is becoming extremely popular for the Japanese. To show shareholders there is a silver lining, he announced they plan to open “thousands of stores” in Japan and Vietnamese markets.

Commitment to Employees

The first and biggest way Starbucks shows their commitment to employees is by just taking care of their workers. For example, they know how important health care, stock options, and compensation are to people in this economy. The Starbucks policy states that as long as you work 20 hours a week you get benefits and stock options. These benefits include health insurance and contributions to employee’s 401k plan. Starbucks doesn’t exclude part time workers, because they feel they are just as valuable as full time workers. Since Starbucks doesn’t have typical business hours like an office job, the part time workers help working the odd shifts.

Another way Starbucks shows their commitment to employees is by treating them like individuals, not just number 500 out of 26,000 employees. Howard Shultz, CEO, always tries to keep humanity and compassion in mind. When he first started at Starbucks, he remembered how much he liked it that people cared about him, so he decided to continue this consideration for employees. Shultz feels that a first impression is very important. On an employee’s first day, he lets each new employee know how happy he is to have them as part of their business, whether it is in person or through a video. His theory is that making a good first impression on a new hire is similar to teaching a child good values. Through their growth, he feels each employee will keep in mind that the company does care about them. Shultz wants people to know what he and the company stand for, and what they are trying to accomplish.

Ethical/Unethical Business Behavior

The last way Starbucks demonstrates corporate social responsibility is through ethical behavior and the occasional unethical behavior. The first ethically positive thing Starbucks involves them self in is the NGO and Fair Trade coffee. Even though purchasing mostly Fair Trade coffee seriously affected their profits, Starbucks knew it was the right thing to do. They also knew that if they did it the right way, everyone would benefit, from farmers, to the environment, to their public image.

In the fall of 2010, Starbucks chose to team up with Jumpstart, a program that gives children a head start on their education. By donating to literacy organizations and volunteering with Jumpstart, Starbucks has made an impact on the children in America, in a very positive way.

Of course there are negatives that come along with the positives. Starbucks isn’t the “perfect” company like it may seem. In 2008, Starbucks made the decision to close 616 stores because they were not performing very well. In order for Starbucks to close this many stores in one year, they had to battle many landlords due to the chain breaking lease agreements. Starbucks tried pushing for rent cuts but some stores did have to break their agreements. On top of breaching lease agreements, Starbucks was not able to grow as much as planned, resulting their future landlords were hurting as well. To fix these problems, tenants typically will offer a buyout or find a replacement tenant, but landlords are in no way forced to go with any of these options. These efforts became extremely time consuming and costly, causing Starbucks to give up on many lease agreements.

As for Starbucks ethical behavior is a different story when forced into the media light. In 2008, a big media uproar arose due to them wanting to re-release their old logo for their 35th anniversary. The old coffee cup logo was basically a topless mermaid, which in Starbucks’ opinion is just a mythological creature, not a sex symbol. Media critics fought that someone needed to protect the creature’s modesty. Starbucks found this outrageous. In order to end the drama and please the critics, they chose to make the image more modest by lengthening her hair to cover her body and soften her facial expression. Rather than ignoring the media concerns, Starbucks met in the middle to celebrate their 35th anniversary.

Related Posts:

- Case Study of Bajaj Auto: Establishment of New Brand Identity

- Case Study: Google's Recruitment and Selection Process

- Case Study of Procter and Gamble (P&G): Structure and Culture

- Case Study of Johnson & Johnson: Using a Credo for Business Guidance

- Case Study of Johnson & Johnson: Creating the Right Fit between Corporate Communication and Organizational Culture

- Case Study: British Petroleum and Corporate Social Responsibility

- Case Study: An Analysis of Competitive Advantages of Honda Corporation

- Case Study: Nissan's Successful Turnaround Under Carlos Ghosn

- Case Study on Marketing Strategy: Starbucks Entry to China

- Case Study: Corporate Social Responsibility at The Body Shop

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, collaborative corporate social responsibility praxis: case studies from india.

Social Responsibility Journal

ISSN : 1747-1117

Article publication date: 25 March 2022

Issue publication date: 26 January 2023

This study aims to explore how corporate social responsibility (CSR) has assumed a new meaning today, with the COVID-19 pandemic. This, in turn, has changed the way companies now view the impact of their activities on the environment, customers, employees, community and other stakeholders.

Design/methodology/approach

This paper uses a qualitative case study approach and draws a critical lens to document the complex interplay between dimensions of CSR, business sustainability and social issues, applying theoretical tools such as social capital theory and stakeholder theory to elucidate the nature of collaborative managerial responses to the organisation’s challenges during the pandemic. This is a case study paper. This paper applies multi method approach to develop a case study analysis through participant observation and report analysis to investigate the CSR approaches undertaken in India by Infosys Genesis, a global leader in technology services and consulting, and Akshaya Patra Foundation, a non-governmental organisation (NGO), which operates the world’s largest lunch school program. This was an appropriate methodology since the focus was on an area that was little understood, while the analysis required an in-depth understanding of a complex phenomenon through observation and a case study. In addition, case study research has been recommended for how, why and what type of research questions that focus on contemporary events (Saunders et al. , 2003; Yin, 1994), such as CSR participation in the existing business environment. Furthermore, the issue under investigation is a real-life situation where the limitations between the phenomenon and the body of knowledge are unclear (Yin, 1994). This was the case because CSR has been probed by numerous disciplines through the application of various theoretical frameworks, each interpreting the context from their own perspective. Leximancer was used for the analysis (a text-mining software for visualising the structure of concepts and themes across case studies). This process differs from the traditional content analysis in that specific word strings are not needed; instead, Leximancer recognises what concepts are present in a set of texts, permitting concepts to be automatically coded in a grounded fashion (Cretchley et al. , 2010, p. 2). The paper will be looked at from three levels comprising themes, concepts and concept profiling to create rich and reliable dimensions of a theoretical model (Myers, 2008). The themes are created in Leximancer software and are built on an algorithm that looks for hidden repeated patterns in interactions. The concepts add a layer and discover which concepts are shared by actors. The concept profiling allows to discover additional concepts and allows to do a discriminant analysis on prior concepts (Cretchley et al. , 2010). Words that come up frequently are treated as concepts. Although the limited number of cases does not represent the entire sector, it enabled collection of rich data through quotes revealing some of the most crucial aspects of large organisations and non-profits in India.

The findings demonstrate how these robust, innovative, collaborative CSR initiatives between a multinational firm and an NGO have been leveraged to combat manifold issues of education, employment and hunger during the pandemic.

Research limitations/implications

Despite significant implications, this study has limitations. A response from only two companies is investigated to the COVID-19 pandemic. The scope of this study is only India, a developing nation, thereby, cross country research is recommended. A comparative study between developed and developing countries may be conducted. A quantitative approach may be used to get empirical findings of the COVID-19 pandemic and post-pandemic policies of companies from an international perspective. Hence, there is ample opportunity to research organisations’ response to the pandemic and CSR as a strong arm to deal with critical disasters.

Practical implications

The paper offers new insights into exploring research and praxis agenda for collaborative potentials towards the evolution of CSR and sustainability.

Social implications

The findings develop new initiatives and combat manifold issues of education, employment and hunger during the pandemic to provide quick relief.

Originality/value

The paper offers new insights into how companies are considering issues related to the crisis, including avoidance of layoffs and maintaining wage payments, and may be in a better position to access fresh capital, relief programs and emergency funds. Taking proactive health and safety measures may avert legal risks to the company. It is likely that the way in which companies are responding to the crises is a real-life test on resilience and adaptation.

- Qualitative case study

- Corporate social responsibility

- Business sustainability

- Collaborative CSR

- Indian MNCs and NGOs

Chavan, M. , Gowan, S. and Vogeley, J. (2023), "Collaborative corporate social responsibility praxis: case studies from India", Social Responsibility Journal , Vol. 19 No. 2, pp. 229-248. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-06-2021-0216

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2022, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

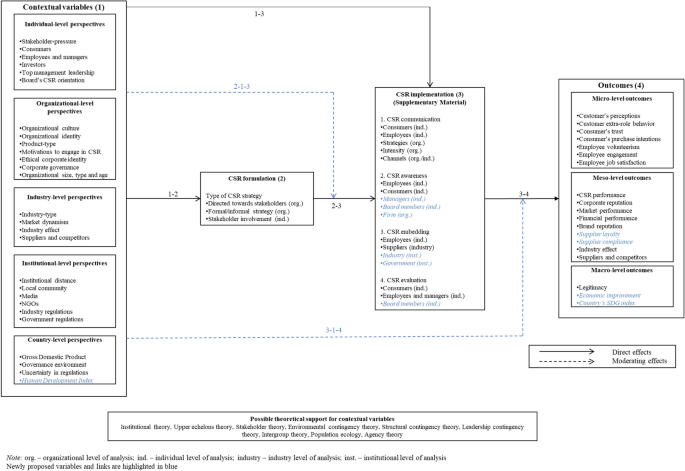

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Implementation: A Review and a Research Agenda Towards an Integrative Framework

- Review Paper

- Published: 02 February 2022

- Volume 183 , pages 105–121, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Tahniyath Fatima ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2383-3390 1 &

- Said Elbanna ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5891-8258 1

81k Accesses

94 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

In spite of accruing concerted scholarly and managerial interest since the 1950s in corporate social responsibility (CSR), its implementation is still a growing topic as most of it remains academically unexplored. As CSR continues to establish a stronger foothold in organizational strategies, understanding its implementation is needed for both academia and industry. In an attempt to respond to this need, we carry out a systematic review of 122 empirical studies on CSR implementation to provide a status quo of the literature and inform future scholars. We develop a research agenda in the form of an integrated framework of CSR implementation that pronounces its multi-dimensional and multi-level nature and provides a snapshot of the current literature status of CSR implementation. Future research avenues relating to multi-level studies, theoretically supported research models, developing economy settings, and more are recommended. Practitioners can also benefit through utilizing the holistic framework to attain a bird’s eye view and proactively formulate and implement CSR strategies that can be facilitated by collaborations with CSR scholars and experts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): The Role of Government in promoting CSR

Asan Vernyuy Wirba

Mandatory CSR and sustainability reporting: economic analysis and literature review

Hans B. Christensen, Luzi Hail & Christian Leuz

A literature review of the history and evolution of corporate social responsibility

Mauricio Andrés Latapí Agudelo, Lára Jóhannsdóttir & Brynhildur Davídsdóttir

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Advocates of corporate social responsibility (hereafter referred to as CSR) propose devising and implementing CSR strategies as an opportunity for organizations. When CSR is looked at from a strategic perspective, it emanates from top management’s vision and values and is not considered an expense but a strategic initiative readily adopted by organizations to differentiate themselves from their competition (Beji et al., 2021 ; Porter & Kramer, 2006 ; Serra-Cantallops et al., 2018 ). The organization’s ulterior motive to receive something in return for going out of its way to do better for the direct and indirect stakeholders indicates extrinsic CSR practices, i.e., strategic CSR (Story & Neves, 2015 ). Currently, CSR is predominantly being viewed as a strategic issue (Zerbini, 2017 ), and such a strategic interest of organizations towards CSR needs to be addressed by scholars when we take into consideration the significant time and resources invested in implementing CSR strategically within the organization (Bansal et al., 2015 ). While CSR has been under the limelight in the academic as well as the industrial sectors since the 1950s, its implementation, however, had not received as much attention (Klettner et al., 2014 ). Furthermore, implementation of CSR like any other strategy implementation is of crucial importance to ensure the successful attainment of one’s goals. Accordingly, an increasing number of academicians, over the past decade, have started focusing on how CSR is implemented in organizations, thereby paving a way for future research (Baumann-Pauly et al., 2013 ; Du & Vieira, 2012 ).

CSR implementation as indicated by Lindgreen, Swaen, et al. ( 2009 ) is a budding field of research and has seen profound growth since they called attention to it in the special issue of Journal of Business Ethics. Although, various empirical papers have proposed CSR implementation frameworks to assist practitioners in implementing and formulating CSR strategies (Baumann-Pauly et al., 2013 ; Ingham & Havard, 2017 ; Lindgreen et al., 2011 ), none of the review studies exclusively looked at CSR implementation from a multi-level and a multi-dimensional perspective. In this study, we define CSR implementation as the process that an organization undertakes to increase the awareness levels of CSR issues and CSR strategies, embed CSR values within the organization, communicate CSR initiatives internally and externally, and evaluate the progress of CSR strategies. The very few scholars who have produced reviews on CSR implementation look at specific dimensions of CSR implementation such as communication (Crane & Glozer, 2016 ) or ways of CSR implementation such as CSR washing (Pope & Wæraas, 2016 ). Therefore, conducting a review such as ours at this stage would allow researchers to attain a better idea on the overall progress of research in CSR implementation literature and provide a clearer perspective on future prospects, thereby filling in an important knowledge gap. In regard to facilitating this main research objective, this review paper proposes an integrative framework for CSR implementation and answers the call for a two-stage systematic review on CSR implementation (Lattemann et al., 2009 ; Lindgreen & Swaen, 2010 ). Hence, through the integrative framework, we illustrate what has been done in CSR implementation literature and how can it be enhanced further.

This review study is guided by three developments: (1) the growing amount of time and efforts organizations are putting in towards implementing CSR, (2) an upsurge in organizations’ interests towards strategic CSR, and (3) recognition among CSR scholars of the need to understand how strategies are implemented (Elbanna et al., 2016 ). The structure of this review study is as follows: “ Defining CSR Implementation ” section begins with the theoretical development of the constructs under study and is followed by “ Review Methodology ” section on methodology that outlines the steps taken to initiate the systematic review and sets the stage for this review study. “ Trends in CSR Implementation Research ” section proceeds to discuss the trends discovered through descriptively analyzing the sampled studies. It also portrays the findings of reviewing the CSR implementation literature in six established categories, namely, level of analysis, research methods, theories being used, geographical focus, journal distribution with years of publication, and time lapse of CSR implementation topics. “ Thematic Analysis: An Integrative Framework of CSR Implementation ” section introduces an integrative CSR implementation framework that thematically distributes the CSR implementation literature and proposes a future research agenda. We conclude with “ Conclusion ” section that provides a summarized overview on theoretical and practical implications of this study.

Defining CSR Implementation

The first step of a systematic review entertains a repetitive process of defining, clarifying, and refining (Tranfield et al., 2003 ). As such, we scoured the CSR implementation literature to find any existing conceptual definitions that can support our review process. In our search for what it means to implement CSR, we found two empirical studies which developed CSR implementation frameworks. We used these studies as the foundation to build our own CSR implementation definition, which is supported with the theory of business citizenship as discussed later in this section. The first study was carried out by Maon et al. ( 2009 ), where a nine-stage integrative framework was developed, based on data collected from case studies and theoretically grounded on Lewin’s change model. The second study of Baumann-Pauly et al. ( 2013 ) regarded the process nature of CSR implementation construct, but generalized it into three separate dimensions; (1) commitment to CSR, (2) internal structures and procedures, and (3) external collaboration. Accordingly, these two frameworks were analyzed to procure specific lenses that can entail a better understanding of CSR implementation process. This phase contributed towards attaining richer and micro-level insights on CSR implementation. In addition, we theoretically based our dimensions of CSR implementation on the theory of business citizenship proposed by Logsdon and Wood ( 2002 ). This theory looks into the ethical, social, and political issues surrounding organizations. According to this theory, an organization can be viewed as a citizen such that there exists moral and structural ties among business organizations, humans, and social institutions where social control is exercised by the society on organizations, thereby protecting and enhancing public welfare and private interests.

As such, we identified four distinct dimensions of CSR implementation that concisely portray the CSR implementation process outlined in the two frameworks proposed by Maon et al. ( 2009 ) and Baumann-Pauly et al. ( 2013 ) and are based on the theory of business citizenship that views a corporation as a citizen, where the responsibilities associated with such citizenship towards society and environment come into play. According to Maon et al. ( 2009 ), CSR design and implementation constitute of nine steps. These are (1) raising CSR awareness, (2) assessing organizational purpose in a societal context, (3) establishing a CSR definition and vision, (4) assessing current status of CSR, (5) developing a CSR strategy, (6) implementing the CSR strategy, (7) communicating about CSR strategy, (8) evaluating CSR strategy, and (9) institutionalizing CSR policy. However, Baumann-Pauly et al. ( 2013 ) consider CSR implementation to comprise three dimensions, namely, commitment to CSR, embedding CSR, and external collaboration.

Of the nine steps proposed by Maon et al. ( 2009 ), we considered steps 1 (raising CSR awareness), 5 (embedding CSR), 6 (implementing CSR activities), 7 (communicating about CSR), and 8 (evaluating CSR) for inclusion in CSR implementation. It is worth noting that though step 5 dealt with formulating CSR strategy, a sub-part of this step (5.2) constituted of embedding CSR in the organization, which is also proposed as a CSR implementation dimension by Baumann-Pauly et al. ( 2013 ). Hence, we included step 5 in our typology of CSR implementation dimensions. Similarly, the commitment to CSR dimension proposed by Baumann-Pauly et al. ( 2013 ) takes into consideration the awareness that organizational members show towards CSR as included in step 1 of Maon et al. ( 2009 ). Although, CSR evaluation (step 8) is primarily not a constituent of strategy implementation process, scholars have begun to indicate its importance in the implementation process, where managers monitor strategy progress and take relevant steps for further improvements in CSR implementation (Graafland & Smid, 2019 ; Laguir et al., 2019 ; Rama et al., 2009 ). Steps 2, 3, and 4 are not considered in this study as they represent a part of CSR design, while step 9 identifies with post-implementation. Hence, the four dimensions relate to the need for an organization to accrue sufficient (1) CSR awareness which manifests itself in the form of organization’s commitment to CSR through (2) communicating and (3) embedding CSR , and placing systematic processes in place to (4) evaluate CSR . Overall, these dimensions entail interactions with various external stakeholders and are not restricted to interorganizational dynamics (Baumann-Pauly et al., 2013 ).

CSR awareness includes the act of raising sensitivity of an organization and its members towards CSR issues, where it may be initiated by managers (top-down approach) or employees (bottom-up approach) for strategic or altruistic reasons and includes commitment to CSR through integrating it into policy documents (Baumann-Pauly et al., 2013 ; Maon et al., 2009 ). Further, CSR communication is directed towards both internal and external stakeholders, where the means or nature of communication and its content need to be identified (Maon et al., 2009 ). The different ways of communication include meetings, corporate internal newsletters, and trainings for internal stakeholders such as employees and board members, while the social and environmental performance of an organization may be disclosed in the form of annual reports or CSR reports and advertisements to external stakeholders.

Embedding CSR entails instilling CSR values among organizational members using tools such as CSR policies, procedures, mission, and vision to reinforce a CSR compliant behavior in operational functions (Baumann-Pauly et al., 2013 ; Maon et al., 2009 ). Lastly, CSR evaluation includes the measurement of how well the CSR objectives have been met, monitoring the progress of these CSR objectives, and exploring ways to improve CSR performance (Maon et al., 2009 ).

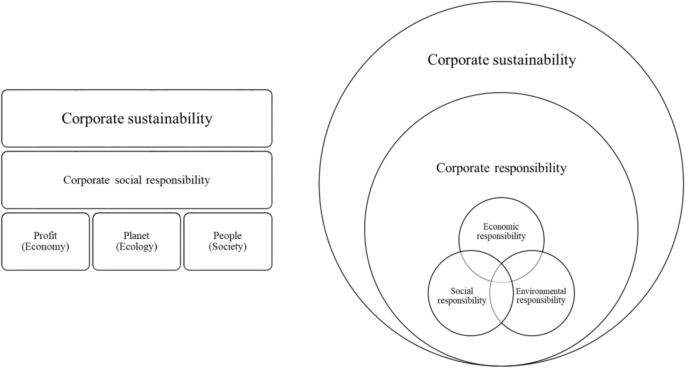

Review Methodology

We utilized a systematic literature approach to accomplish our research goal of surveying the literature on CSR implementation. Systematic reviews are commonly used to ensure transparency and replicability in the review process (Hossain, 2018 ). Given that it is imperative to outline the scope of one’s search prior to ensuing the data collection process (George et al., 2019 ; Tranfield et al., 2003 ), we restricted our range to any research study that exclusively focused on the concept of CSR implementation or its four dimensions, namely, CSR awareness, CSR communication, CSR embedding, and CSR evaluation. The concept of CSR has taken various titular forms in literature, where overlapping constructs like corporate sustainability, corporate social performance, and corporate citizenship have been proposed and are now interchangeably used by researchers (Albinger & Freeman, 2000 ; Evans & Davis, 2014 ; Matten & Crane, 2005 ; Pedersen et al., 2018 ; Wood, 1991 ). However, the terminology of CSR had been most widely used by researchers (Matten & Crane, 2005 ), and as such is adopted in this study. Furthermore, we do not include research examining the concept of sustainability or corporate sustainability as it is an overarching concept that incorporates two different topics of CSR and corporate responsibility (see Fig. 1 ). As such, CSR acts as an intermediary tool that examines the efforts of organizations aimed at balancing the triple bottom line (van Marrewijk, 2003 ).

Mapping of corporate sustainability, CSR, and corporate responsibility (adapted from van Marrewijk, 2003 )

Three databases, namely, EBSCO, Science Direct, and ABI/Inform (ProQuest), were searched with the following set of keywords: “CSR awareness,” “CSR implementation,” “CSR sensitiveness,” “commitment to CSR,” “CSR integration,” “initiating CSR,” “CSR issues,” “CSR communication,” “CSR disclosure,” “CSR report,” “CSR value,” “embedding CSR,” “CSR policies,” “CSR procedure,” “CSR vision,” “CSR mission,” “evaluating CSR,” and “monitoring CSR.” We also took into account different occurrences of the keywords such as “implementing CSR,” “sensitivity to CSR,” and “CSR policy.” Further, our inclusion criteria did not include any time restriction as this would have limited our analysis and inferences of understanding the literature conducted so far on CSR implementation. However, in order to ensure quality of our findings and development of a relevant agenda for future research, we included peer-reviewed journal articles that were published in journals with a rating of at least B and above as per the 2019 ABDC ranking and 3 and above for the 2021 AJG ranking (Hoque, 2014 ). Imposition of the above strict criteria led to collection of 168 research articles. These papers were further analyzed to assess if the focus of their study was related to our research objective. Thus, the selection of the studies was contingent on the main topic of the study in question being either CSR implementation or one of the four dimensions (CSR awareness, CSR communication, CSR embedding, and CSR evaluation). In applying this criteria, we were able to shortlist 140 research studies.

Of the total 140 identified studies, we analyzed the nature of their research and found 18 papers were theoretical in nature. One of the theoretical papers was an editorial and was excluded. The remaining 122 empirical studies Footnote 1 are considered for further review, while the 17 theoretical papers are used to supplement the analysis and findings attained from this systematic review. We now discuss the findings attained from conducting our two-staged narrative synthesis analysis that provides the reader with a descriptive and thematic outlook of CSR implementation literature. In utilizing a narrative synthesis approach, we are able to efficiently provide a narrative on the CSR implementation literature through the use of statistical data (Popay et al., 2006 ). The first stage detailed in Sect. Trends in CSR Implementation Research analyzes the entire empirical literature descriptively (123 studies) and discusses the underlying trends on the basis of the (1) level of analysis, (2) research methods, (3) theories being used, (4) geographical focus, (5) journal distribution with years of publication, and (6) time lapse of CSR implementation topics. The second stage brings a more nuanced understanding of the empirical literature where the literature is analyzed with respect to a comprehensive outlook of CSR implementation in Sect. Thematic Analysis: An Integrative Framework of CSR Implementation .

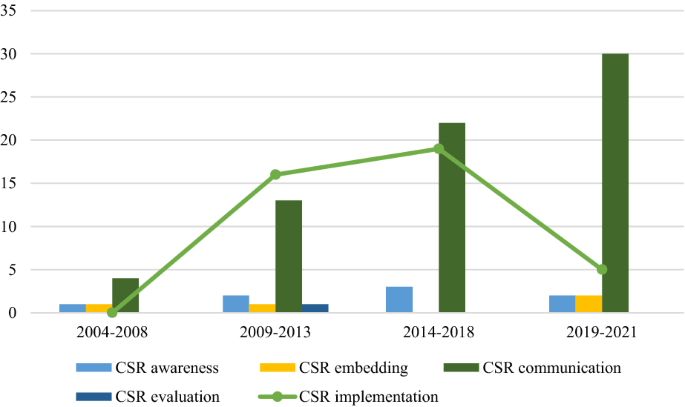

Trends in CSR Implementation Research

Upon analyzing the empirical literature on CSR implementation, we were able to make several inferences that would shed light on research gaps not yet covered in the CSR implementation literature. We followed established review studies in CSR literature (Aguinis & Glavas, 2012 ; Pisani et al., 2017 ) and focused on six aspects to attain a general purview of CSR implementation research conducted to date. First, with respect to the level of analysis , CSR implementation literature, unlike the general CSR literature, does not seem to suffer from lack of focus on individual-level research. However, majority of the empirical research conducted on CSR implementation is at the firm level (refer to Table 1 ). In addition to that, multi-level studies are quite rare with only 8 papers analyzing CSR implementation at multiple levels, e.g., a combination of individual, firm, institutional, industry, and country levels with a combination of at most three levels (Ettinger et al., 2021 ; Helmig et al., 2016 ; Lattemann et al., 2009 ; Lindgreen, Antioco, et al., 2009 a; Lu & Wang, 2021 ; Pomering & Dolnicar, 2009 ; Shen & Benson, 2016 ; Zamir & Saeed, 2020 ). In spite of acknowledging the multi-dimensional nature of CSR implementation (Lindgreen, Swaen, et al., 2009 b), majority of the scholars have failed to conceptualize and operationalize CSR implementation at a multi-dimensional basis. Accordingly, future research needs to take into consideration the multi-dimensional nature of CSR implementation and conduct scientific research that is not limited to a single level of analysis. Other empirical studies looked at various levels of analyses such as advertisement level (Green & Peloza, 2015 ), project level (Rama et al., 2009 ), activity level (Jong & Meer, 2017 ), and interaction level (Muthuri et al., 2009 ).

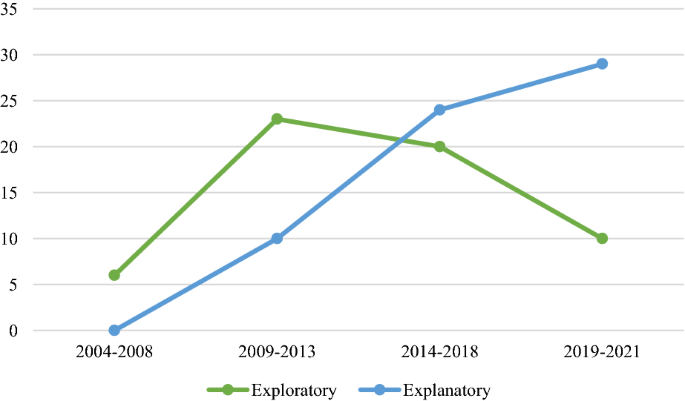

Second, the CSR implementation literature uses a wide variety of research methods . 36% of the research studies used qualitative research methods, 53% used quantitative methods, and only 11% of the studies have used mixed methods. The use of qualitative methods can be explained by the exploratory nature of the studies, which accounted for 49% of the empirical research, while a majority of 51% studies were explanatory in nature. However, given the growing adoption of CSR by different organizations across industries and countries, scholars have delved into examining implementation of CSR from a more explanatory nature as the trend line shows in Fig. 2 . Further, scholars can utilize mixed method studies in future to attain an insightful and a holistic empirical understanding of their research topic. This would allow the research findings to have both theoretical and geographical validity.

Trend of CSR implementation studies’ nature

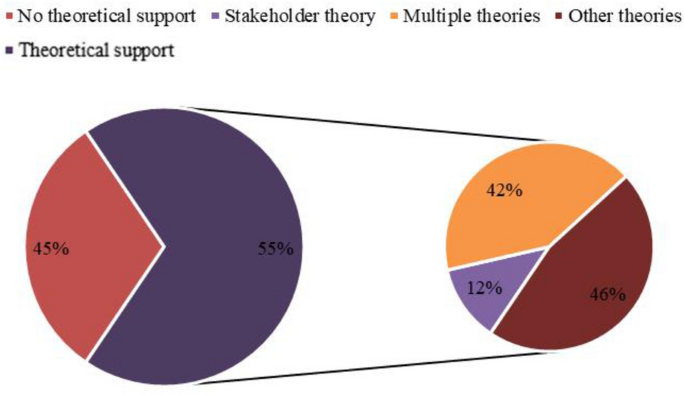

Third, the theoretical underpinning of research on CSR implementation is still emergent, where a considerable proportion of the empirical literature, approximately 45%, was missing a theoretical foundation. Having a proper theory is quite essential to easily illustrate complex concepts (Frynas & Yamahaki, 2016 ), thereby indicating scope for future research to have richer theoretical support. Of the remaining 67 research studies that had theoretical support (54% of total empirical literature), a considerable proportion of research (42%) resorted to the use of multiple theories to substantiate their proposed frameworks. The most commonly used theory was stakeholder theory inclusive of its use in research studies with multiple theories (28%, 19 out of 67 papers) (e.g., Ettinger et al., 2018 ; Lindgreen et al., 2011 ; Park & Ghauri, 2015 ; Zheng et al., 2015 ). Lastly, as depicted in Fig. 3 , the remaining 31 research studies (46%) used a diverse range of theories from other disciplines like psychology (theory of planned behavior, balance theory, attribution theory, and social identity theory), communications (diffusion theory, inoculation theory), sociology (systems theory, social exchange theory, social identity theory), and biology (signaling theory).

Theoretical orientations in CSR implementation literature