ARCHIVEGRID

Tomás ybarra-frausto research material on chicano art, 1965-2004, ybarra-frausto, tomás, 1938-, smithsonian institution - archives of american art, related resources, more like this, organizations.

The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics

Chicanx artists have forged a remarkable history of printmaking grounded in social justice. explore this innovative and vibrant tradition through works in saam's collection..

By Smithsonian American Art Museum

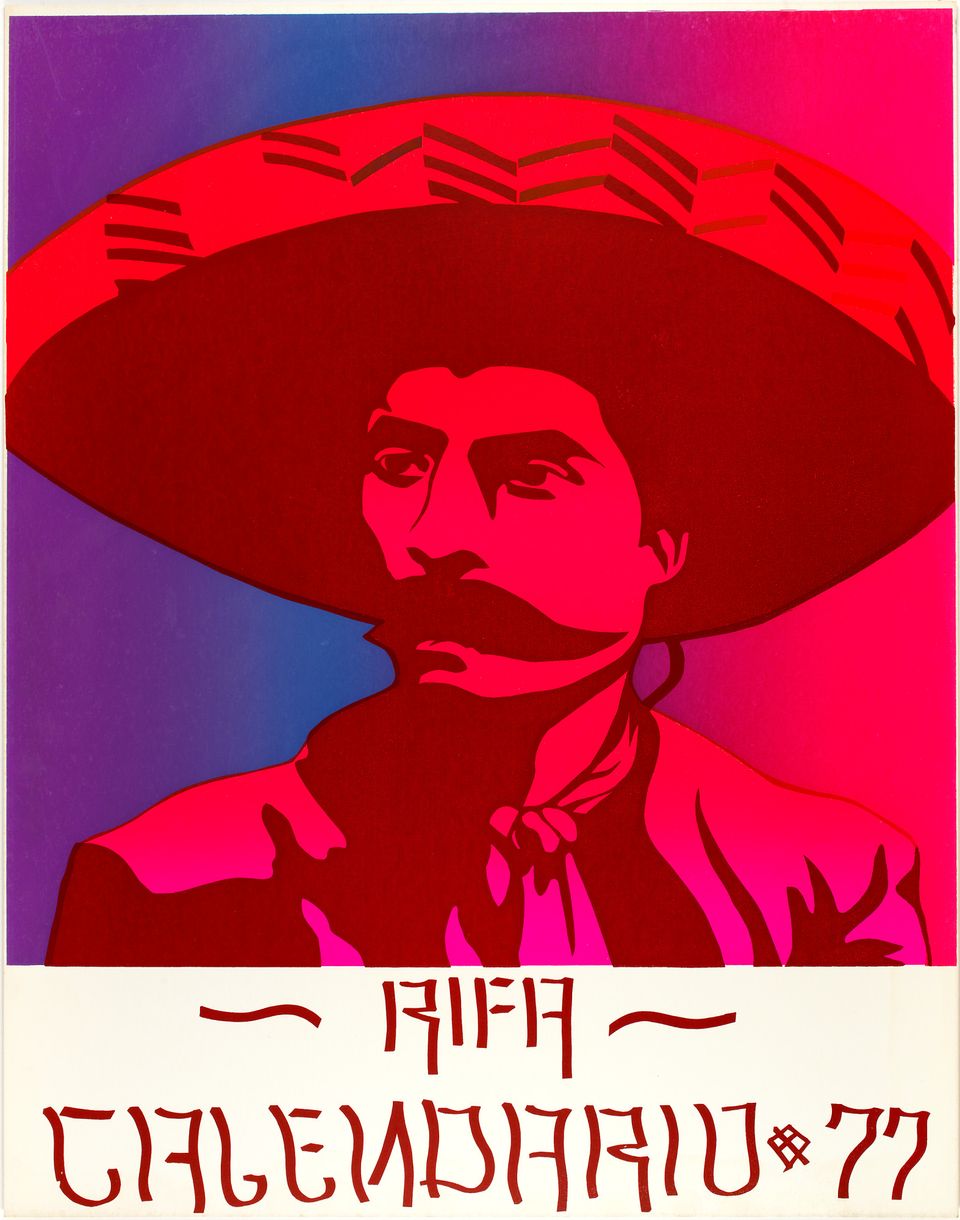

RIFA, from Méchicano 1977 Calendario (1976) by Leonard Castellanos Smithsonian American Art Museum

Artworks from the exhibition, ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now , all part of SAAM's collection, revise notions of Chicanx identity, spur political activism and educate viewers in new understandings of U.S. and international history.

Hasta La Victoria Siempre (1975) by Luis C. González, Héctor D. González, and Royal Chicano Air Force Smithsonian American Art Museum

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Chicano Movement announced a new political and cultural consciousness among people of Mexican descent in the United States.

Chicano activist artists created vivid, eye-catching posters with domestic and global politics in mind.

They channeled social activism in support of farm workers’ rights, civil rights, labor equity, anti-war, and, later, feminist and LGBTQ+ movements into assertive aesthetic statements in the graphic arts.

Mujer de Mucha Enagua, PA' TI XICANA (1999) by Yreina D. Cervántez Smithsonian American Art Museum

By the 1970s, self-identified Chicana artists challenged the overwhelming representation of men in defining the Movement.

Artists such as Ester Hernandez, Yolanda López, and Yreina D. Cervántez sought to challenge ways of conceiving community, aesthetics, and politics that were patriarchal and silenced LGBTQ voices.

Often in the face of hostility, they ushered in new imagery and conceptual frameworks that centered on women’s lives, feminist changemakers, spirituality, and paved the way for future examinations of identity, including Indigeneity.

Migration is Beautiful (2018) by Favianna Rodriguez Smithsonian American Art Museum

Exploring the mentor-mentee relationships that have sustained the field is an illuminating look into the Chicanx artistic community. There is a through-line of direct relationships leading from the founders of the movement to printmakers who are active today.

Chicanx artists and institutions welcomed, nurtured, and supported each other, as well as other cross-cultural collaborators. The artworks map a dense matrix of relationships that reveal the importance of intergenerational support structures and far-reaching networks.

El Animo es Primero (Encouragement Is First) (2018) by Juan de Dios Mora Smithsonian American Art Museum

The broad network that resulted includes Latinx artists with links to other Latin American nations, white allies, card-carrying Chicano activists, or recent Mexican immigrants who may or may not identify as Chicanx.

Included in this broad category of Chicanx graphics are works by more recent Mexican immigrants such as Juan de Dios Mora, whose prints delve into the contemporary nuances of the transnational border space that is South Texas.

The relationships expand throughout the nation, including in Midwest and on the East Coast. Dominican American artist Pepe Coronado's transformative experience at the Serie Project, a print residency established by the late Chicano artist Sam Coronado in Austin, Texas, led him to found the collective, the Dominican York Proyecto GRAFICA, in New York.

Justice for Our Lives (2014-2020) by Oree Originol Smithsonian American Art Museum

The legacy of Chicanx graphics establishes how interracial and cross-cultural solidarity was and remains an important element of Chicanx print networks.

"Justice for Our Lives" is an online and public social justice artwork. Using original photographs, artist Oree Originol creates black-and-white digital portraits of men, women, and children killed during altercations with law enforcement.

Installation of "Justice for Our Lives" (2020) by Oree Originol Smithsonian American Art Museum

The artist makes each portrait available for download for community members to use. He also creates dynamic, large-scale installations, placing them in public spaces to draw the attention of passersby.

I Am UndocuQueer-Reyna W. (2012) by Julio Salgado Smithsonian American Art Museum

Like Originol's prints, the digital works of Julio Salgado, a Dreamer who received legal status through the federal immigration policy called Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), show the innovative practices of today’s Chicanx printmakers that go beyond paper.

"Sun Mad" and "Sun Raid" (1982; 2008) by Ester Hernandez Smithsonian American Art Museum

The long legacy of the activism by Chicanx graphics artists can be seen in the iconic work of Ester Hernandez, who explores the social justice issues facing the community in 1982 and that persist almost 30 years later.

In her 1982 print, "Sun Mad," Hernandez reconfigures the cheerful branding of the Sun-Maid raisin company into a grim warning, a response to her family’s exposure to polluted water and pesticides in California’s San Joaquin Valley.

Twenty-six years later, she reimagines her classic poster as a condemnation of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). She outfits the calavera (skeleton) with an ICE wrist monitor and a huipil, a traditional indigenous garment.

Boycott Grapes, Support the United Farm Workers Union (1973) by Xavier Viramontes Smithsonian American Art Museum

The powerful socially-minded artistic legacy forged by activist Chicano artists working in the Movement and passed through Chicanx mentorship networks, remains visible in the art of printmakers working today.

View a selection of iconic and innovative Chicanx graphics from "Printing the Revolution."

La Curandera (1974) by Carmen Lomas Garza Smithsonian American Art Museum

Frida Kahlo (September), from Galería de la Raza 1975 Calendario (1975) by Rupert García Smithsonian American Art Museum

Undocumented (1980) by Malaquias Montoya Smithsonian American Art Museum

Messages to the Public: Pesticides! (1989) by Barbara Carrasco Smithsonian American Art Museum

Quiero Mis Queerce (2020) by Julio Salgado Smithsonian American Art Museum

Bee Pile (2010) by Sonia Romero Smithsonian American Art Museum

Between the Leopard and the Jaguar (2019) by Melanie Cervantes, Dignidad Rebelde Smithsonian American Art Museum

Who's the Illegal Alien, Pilgrim? (1981) by Yolanda López Smithsonian American Art Museum

El Coyote (2010) by Michael Menchaca Smithsonian American Art Museum

¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now will soon be making its first stop on a national tour. For more information, please visit the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Changemakers Portraits from "Printing the Revolution" (2020) by Various Smithsonian American Art Museum

¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now presents, for the first time, historical civil rights-era prints by Chicano artists alongside works by graphic artists working from the 1980s to today. It was on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum from November 20 - November 22, 2020 and May 14, 2021 - August 8, 2021. For more information on the exhibition and the accompanying catalogue, please visit: https://americanart.si.edu/exhibitions/chicano-graphics

This exhibition is organized by E. Carmen Ramos , former curator of Latinx art at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, with Claudia Zapata , curatorial assistant for Latinx art.

¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now is organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum with generous support from The Latino Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Latino Center, Michael Abrams and Sandra Stewart, The Honorable Aida Alvarez, Joanne and Richard Brodie Exhibitions Endowment, James F. Dicke Family Endowment, Sheila Duignan and Mike Wilkins, Ford Foundation, Dorothy Tapper Goldman, HP, William R. Kenan Jr. Endowment Fund, Robert and Arlene Kogod Family Foundation, Lannan Foundation, and Henry R. Muñoz, III and Kyle Ferari-Muñoz.

African American Art: Harlem Renaissance, Civil Rights Era, and Beyond

Smithsonian american art museum, beauty and struggle, edmonia lewis, the civil war and american art, between worlds: the art of bill traylor.

Site Navigation

Tomas ybarra-frausto research material on chicano art.

In 1997, the Archives of American Art received a donation of 20 linear feet of research material on the Chicano art movement in the United States and Latin America, compiled by Dr. Tomás Ybarra-Frausto. Ybarra-Frausto was a professor at Stanford University in the department of Spanish and Portuguese and has published extensively on Latin American and U.S. Latino culture. Selected items from this collection were exhibited at the Archives New York Research center in the fall of 1998.

For more information about the materials found in Ybarra-Frausto?s extensive files, see the collection description: Tomás Ybarra-Frausto research material on Chicano art, 1967-2008 bulk 1970-1985

In the 1960s, activist Chicano artists forged a remarkable history of printmaking that remains vital today. Many artists came of age during the civil rights, labor, anti-war, feminist, and LGBTQ+ movements and channeled the period’s social activism into assertive aesthetic statements that announced a new political and cultural consciousness among people of Mexican descent in the United States. ¡Printing the Revolution! , organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum, explores the rise of Chicano graphics within these early social movements and the ways in which Chicanx artists since then have advanced innovative printmaking practices attuned to social justice.

Explore ¡Printing the Revolution! from the comfort of your home with our virtual exhibition tour!

More than reflecting the need for social change, the works in this exhibition project and revise notions of Chicanx identity, spur political activism and school viewers in new understandings of U.S. and international history. By employing diverse visual and artistic modes from satire, to portraiture, appropriation, conceptualism, and politicized pop, the artists in this exhibition build an enduring and inventive graphic tradition that has yet to be fully integrated into the history of U.S. printmaking.

This exhibition is the first to unite historic civil rights era prints alongside works by contemporary printmakers, including several that embrace expanded graphics that exist beyond the paper substrate. While the dominant mode of printmaking among Chicanx artists remains screen-printing, this exhibition features works in a wide range of techniques and presentation strategies, from installation art, to public interventions, augmented reality, and shareable graphics that circulate in the digital realm. The exhibition also is the first to consider how Chicanx mentors, print centers, and networks nurtured other artists, including several who drew inspiration from the example of Chicanx printmaking.

April 23, 2–6 p.m.

Ignite your voice and gather for performances, activities, drinks, and more!

Exhibition Highlights

Slide controls.

Leonard Castellanos

Screenprint on paperboard

RIFA, from Méchicano 1977 Calendario

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, 2012.53.1, © 1976, Leonard Castellanos

Oree Originol

78 Digital images

Justice for Our Lives

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Patricia Tobacco Forrester Endowment, 2020.51A-MM, © 2014, Oree Originol

Malaquias Montoya

Screenprint on paper

Yo Soy Chicano

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Gilberto Cárdenas and Dolores García, 2019.51.1, © 1972, Malaquias Montoya

Rupert García

Frida Kahlo (September), from Galería de la Raza’s 1975 Calendario

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Margaret Terrazas Santos Collection, 2019.52.19, © 1975, Rupert García

Carlos A. Cortéz

Linocut on paper mounted on paperboard

José Guadalupe Posada

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Tomás Ybarra-Frausto, 1995.50.9, © 2020, Dora Katsikakis

Melanie Cervantes

Between the Leopard and the Jaguar

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Samuel and Blanche Koffler Acquisition Fund, 2020.39.5, © 2019, Melanie Cervantes

Ester Hernández

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Tomás Ybarra-Frausto, 1995.50.32, © 1982, Ester Hernández

Share your experience with ¡Printing the Revolution! using: #CarterPTR

Note about terms: The exhibition uses the term “Chicano” to refer to the historical Chicano movement in the United States (starting roughly in 1965) and its participants. “Chicana” references women who fought for and prefer this designation. "Chicanx” is a current, inclusive designation that is gender-neutral and non-binary.

Installation Photos

Click a button below to open in gallery. Activating any of the below buttons shows the installation photos gallery

Installation Photos Gallery

Past Events

Tour | ¡printing the revolution.

Adult Workshop: Print Your Protest

¡printing the revolution exhibition celebration.

Exhibition Talk: ¡Printing the Revolution!

Carter playdate: spread the word.

Itty-Bitty Art: Word Play

Toddler Studio: Alphabet Games

Paper Forum: Collecting the Revolution

Bookish: the house on mango street.

Tea & Tours | ¡Printing the Revolution!

Spring Break at the Carter: Powerful Voices

Educator Workshop: Activating Student Engagement

Girl Scouts: Print and Paste!

Member Preview Days | ¡Printing the Revolution!

From the shop.

A groundbreaking look at how Chicano graphic artists and their collaborators have used their work to imagine and sustain identities and political viewpoints during the past half-century.

¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now is organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum with generous support from the Latino Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Latino Center, Michael Abrams and Sandra Stewart, The Honorable Aida Alvarez, Joanne and Richard Brodie Exhibitions Endowment, James F. Dicke Family Endowment, Sheila Duignan and Mike Wilkins, Ford Foundation, Dorothy Tapper Goldman, HP, William R. Kenan Jr. Endowment Fund, Robert and Arlene Kogod Family Foundation, Lannan Foundation, and Henry R. Muñoz, III and Kyle Ferari-Muñoz.

The Carter’s presentation of ¡Printing the Revolution! is generously supported by Susan and Stephen Butt, Lannan Foundation, the Alice L. Walton Foundation Temporary Exhibitions Endowment, and Fernando Yarrito.

Smithsonian Voices

From the Smithsonian Museums

SMITHSONIAN AMERICAN ART MUSEUM AND THE RENWICK GALLERY

Chicano Artists Challenging History and Reclaiming Cultural Memory

Chicano artists use graphics to reframe history with new perspectives

Claudia Zapata

Chicano artists used inventive graphic forms to offer new perspectives on key moments in national and global history

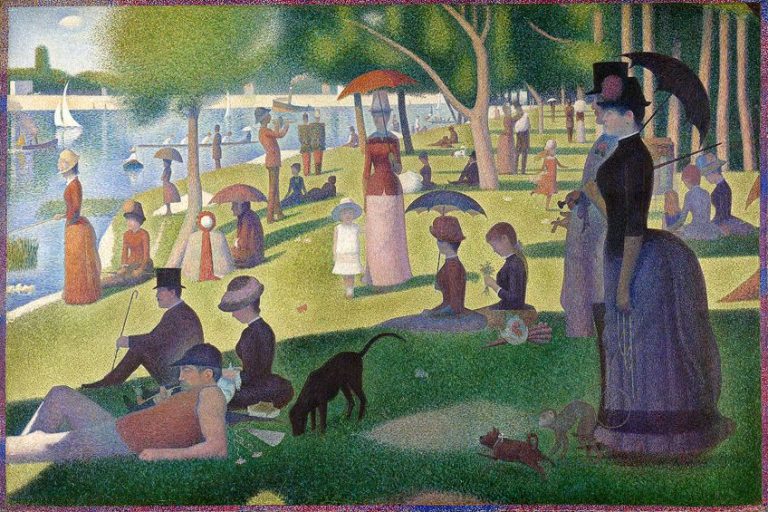

In 1968, graphic artist Rupert García became a pivotal figure in the Third World Liberation Front, a coalition of Chicano, African American, Asian American, and Native students who held a major strike that year at San Francisco State College to demand ethnic studies programs and greater diversity in faculty and students. In later years, the protest had a significant impact on higher education in the United States, as more students demanded ethnic studies and universities eventually responded with new academic departments and teaching positions. Ethnic studies programs marshalled interdisciplinary methodologies focused on Latinx, African American, Asian American, and Native cultures and often told American and global histories through the lens of U.S. colonialism and imperialism, perspectives rarely incorporated in historical texts at that time. Several artists in ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now shared a similar drive to reframe history. Their works explored alternative perspectives of national and global events, from the U.S Bicentennial to the rise of dictatorships in Latin America.

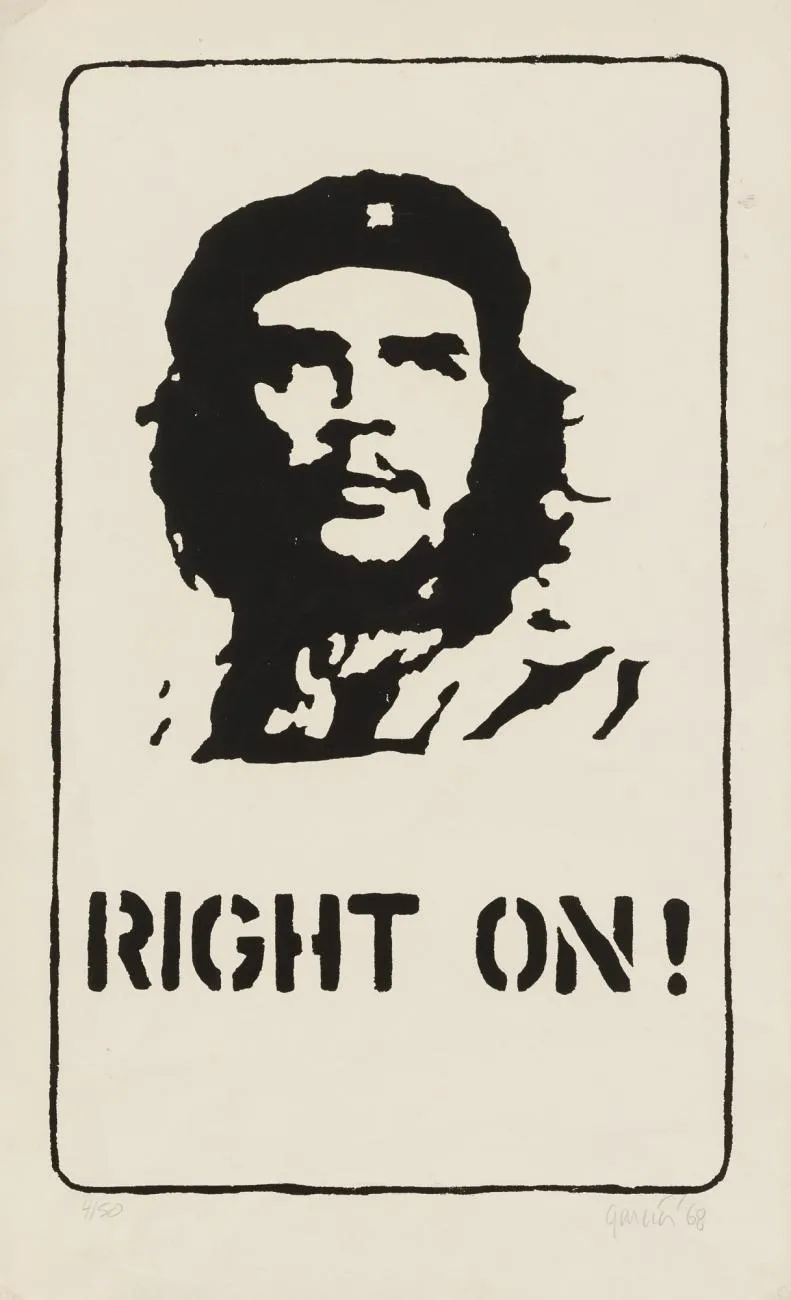

García’s Right On! , created in 1968 during the San Francisco State strike, is based on Alberto Korda’s photograph of Cuban revolutionary leader and icon Ernesto “Che” Guevara. Like San Diego artist Mario Torero, Chicano artists frequently reclaimed this Cuban figure to represent global resistance and revolutionary ideals. To capture the solidarity among the Third World Liberation students, García combined Che’s likeness with the popular Black Power slogan, “Right On!” This print reflects the artist’s signature graphic style of pop art sensibilities and forthright political statements. Early in the protest and related to the urgency of the moment, García created one-color screenprints like this. In fact, he created Right On! to raise funds for students’ bail funds, a common practice among political graphics of the time.

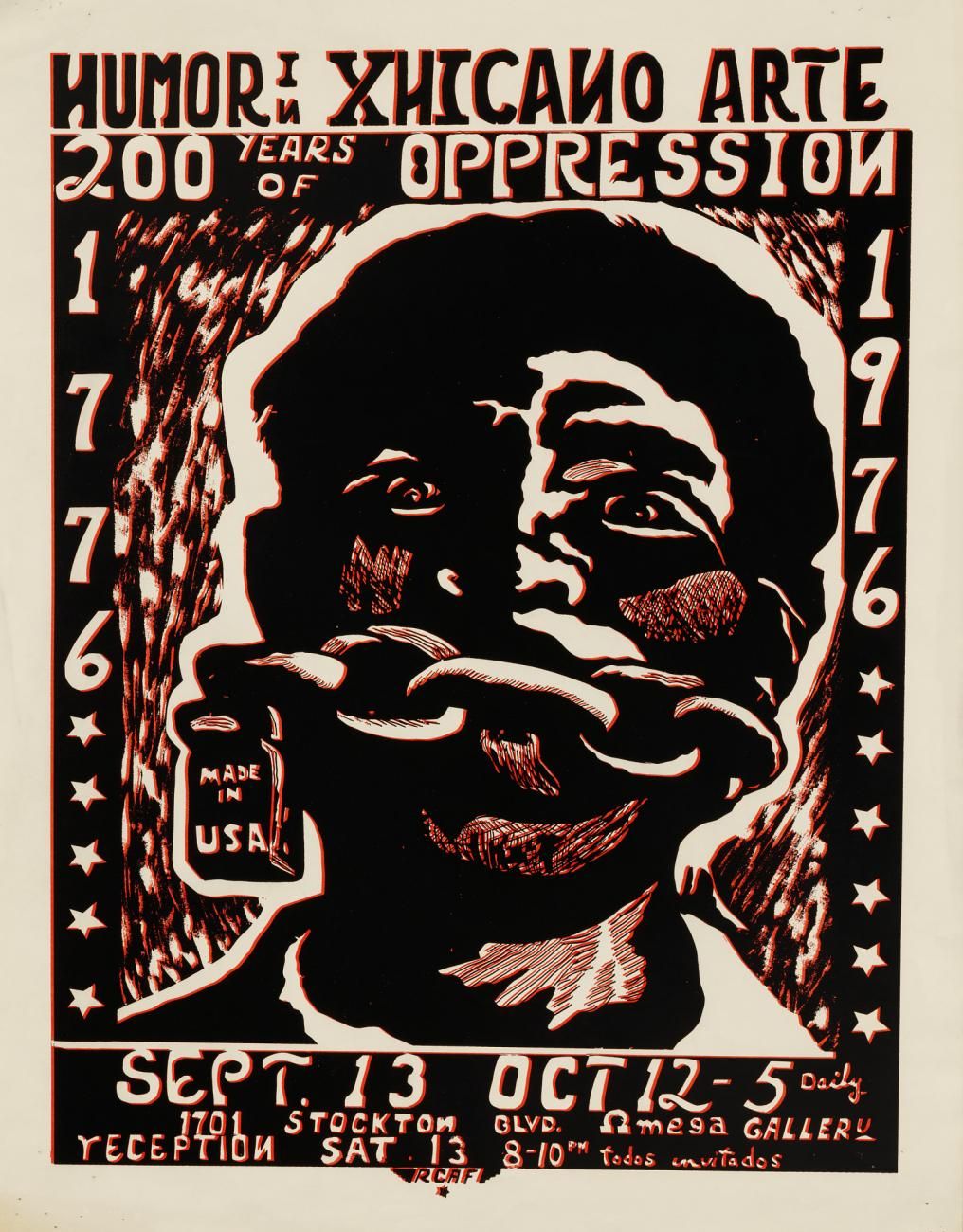

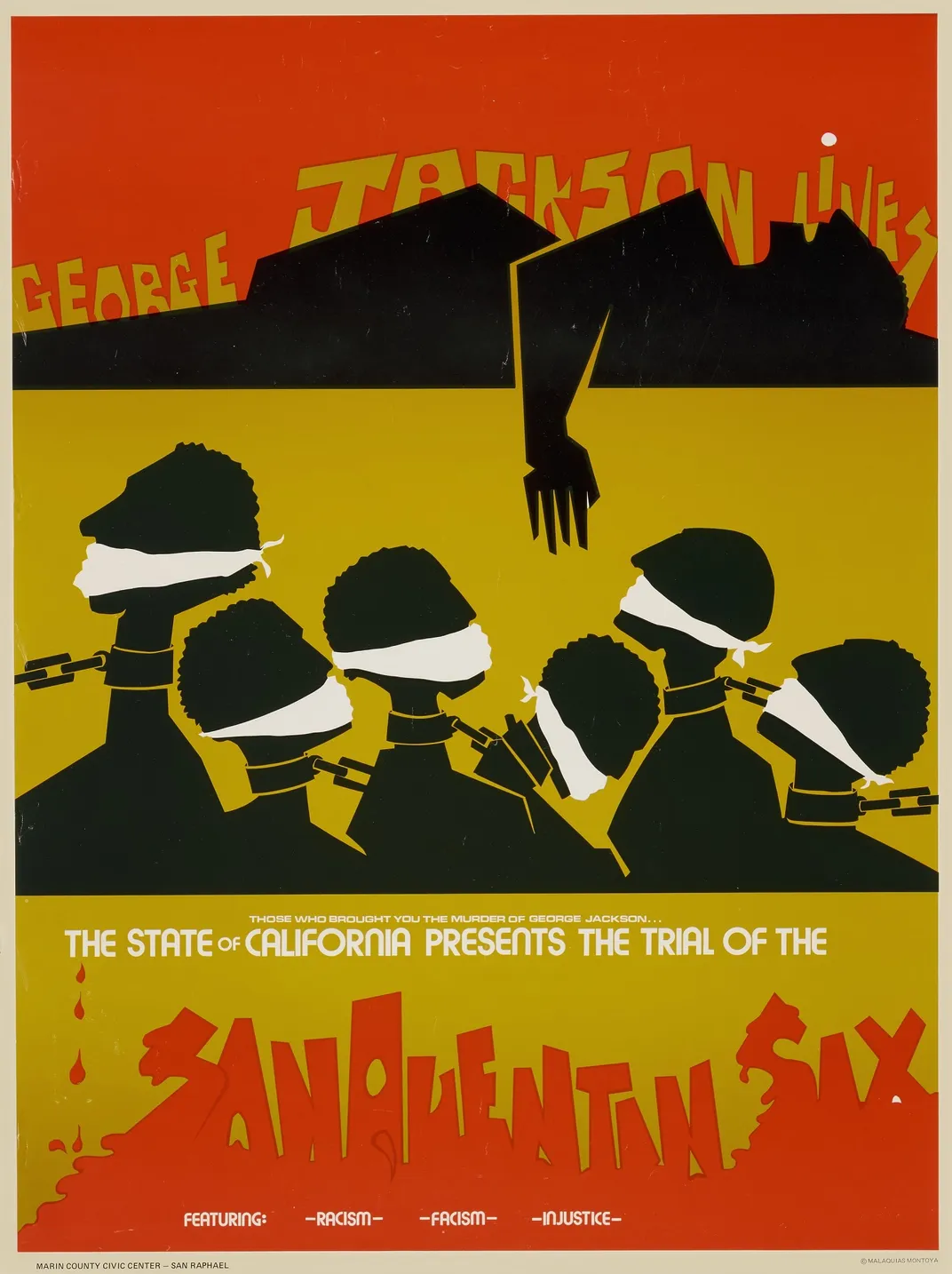

In 1976, as the the U.S. marked its Bicentennial, Chicano and other artists of color like Faith Ringgold questioned the celebratory rhetoric of this national anniversary, approaching it instead as a moment of solemn reflection. The Bicentennial commemorated the two hundred years since the republic’s creation when British colonies in North America overcame colonial rule. Rudy Cuellar, a member of the Royal Chicano Air Force (RCAF) art collective, challenged the national celebration’s overt patriotic imagery in his event poster, Humor in Xhicano Arte 200 Years of Oppression 1776-1976 . The evocative scene focuses on a young Indigenous person chained with a padlock reading “Made in USA.” The chained figure is a remake of Mexican artist Adolfo Mexiac’s 1954/68 print protesting U.S. intervention in Guatemala and Mexican state violence. Many artists and activists like Cuellar, who lived through the early period of the civil rights movement, questioned whether all the people of the United States equally experienced freedom. His image of a gagged and chained figure resonated with the experiences of such figures as Bobby Seale and the San Quentin Six, who were gagged and chained, respectively, during their courtroom trials in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

RCAF member Ricardo Favela’s 1976 print Centennial Means 500 Years of Genocide! calls for the release of Russell Redner and Kenneth Loudhawk, American Indian Movement activists arrested in 1973 after they participated in a staged protest at Wounded Knee, South Dakota. Protesters at Wounded Knee demanded a review of Indian treaties and an investigation into the treatment of Native Americans in the United States. By juxtaposing a series of Lakota war shields with a Native figure whose face is partially obscured by a frayed U.S. flag and adding the words “500 years” and “centennial,” Favela conjures a long history of violent clashes between the United States and Indian nations. The print provides further information to support the activists’ release and acts as a reminder of the violent conquest of Native peoples across the Americas since 1492.

The history of Manifest Destiny, the idea that the United States was destined to inhabit a large swath of North America “from sea to shining sea,” is a central themes for Chicano artists. The Mexican American War (1846-1848), which resulted in the United States annexing former Mexican territories in the Southwest and what would later become California to the U.S., is a recurring historical marker for Chicano artists. Like the RCAF, Eric García turns to a lauded historical moment and inverts its public reception. The artist’s personal experience as a member of the U.S. Air Force who was stop-lossed—given an involuntary extension of his active-duty service—led him to portray military critiques throughout his artistic career. In Chicano Codices , he uses the ancient and colonial accordion-style book form, the codex, and sequential art to reimagine this military history and critique the “victorious” U.S. through its common personification: Uncle Sam.

Chicano artists rethought other graphic forms as an entry point for historical and political reflections, employing familiar household objects such as the calendar. During the civil rights era, artists first adopted the calendar format because of its connection to Chicano daily life. Many artists grew up surrounded by illustrated calendars hanging in their homes. Given as gifts by local stores, they commonly portray scenes of Mexican Indigenous myths. Mexican commercial art from the 1940s and 1950s, which famously feature works by the painter Jesús Helguera, inspired the calendar genre. His paintings and illustrations are epic dramatizations of Mexican myths rendered in a classicizing realist style. These images continue to circulate today in calendars gifted by local businesses, like bakeries and mechanic shops.

In the United States, calendar prints, and in some cases, portfolios of twelve prints devoted to each month, served as a fundraising tool for artists, galleries, and print shops to make art available to community members at an affordable price. SAAM has an extensive collection of calendar prints, underscoring how artists were drawn to this format as a vehicle for historical awareness and international solidarity.

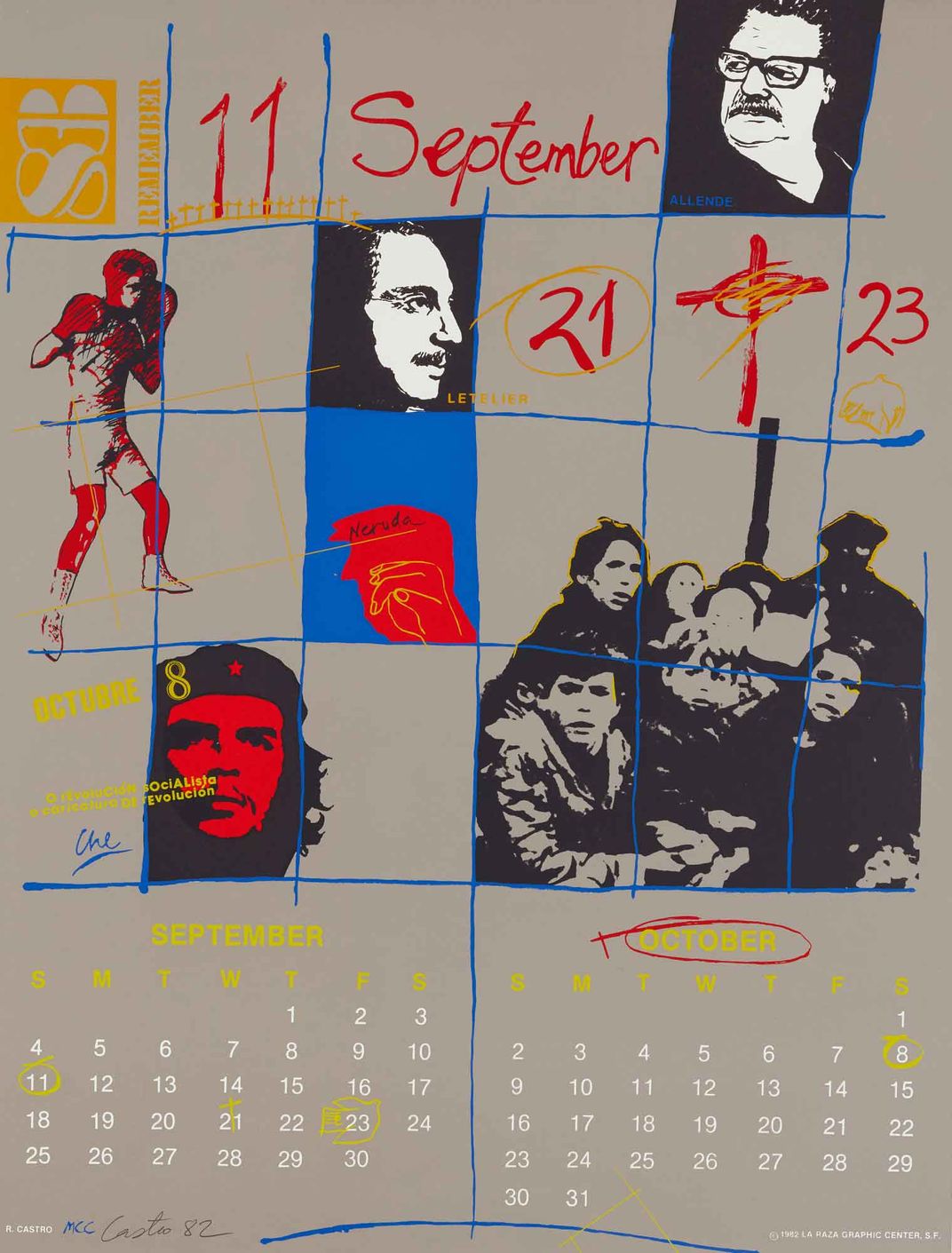

Artists used the calendar as an alternative to mainstream media and to expose U.S. involvement in key international events, like the Chilean military coup of 1973. Chilean artist René Castro used his print September/October from La Raza Graphic Center's 1983 Political Art Calendar to feature critical moments in Chilean history. He highlighted historical dates such as September 11, when Augusto Pinochet’s military violently overthrew the democratically elected Socialist Chilean president Salvador Allende in 1973. Other major moments in Castro’s calendar include Che Guevara’s death on October 9, 1967 and the assassination of Orlando Letelier, Allende’s exiled foreign minister in Washington, D.C., on September 21, 1976.

Castro was directly affected by these moments, having spent two years in a Chilean prison camp as a political prisoner. After this, he moved to San Francisco’s Bay Area as an exile and was active in Chicano print centers, like La Raza Graphics. He eventually founded Mission Gráfica, the print center within Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts (MCCLA), with fellow printmaker Jos Sances.

Artists in ¡Printing the Revolution! creatively subvert widely accepted historical narratives. These ongoing retellings of national and global histories are an essential part of democratic civic discourse. These works create platforms for new understandings of our national past and present.

Claudia Zapata | READ MORE

Claudia E. Zapata is a curatorial assistant of Latinx art at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and is a doctoral candidate at Southern Methodist University. They received their BA and MA in art history from the University of Texas at Austin, specializing in Classic Maya art. Their research interests include curatorial methodologies of identity-based exhibitions, Chicanx and Latinx art, digital humanities, BIPOC zines, and designer toys. Zapata has curated exhibitions at Mexic-Arte Museum in Austin and other Texas institutions. They have published articles in Panhandle-Plains Historical Review, JOLLAS, Aztlán, Hemisphere, and El Mundo Zurdo 7.

Visit Planning

- Plan Your Visit

- Event Calendar

- Current Exhibitions

- Family Activities

- Guidelines and Policies

Access Programs

- Accessibility

- Dementia Programs

- Verbal Description Tours

Explore Art and Artists

Collection highlights.

- Search Artworks

- New Acquisitions

- Search Artists

- Search Women Artists

Something Fun

- Which Artist Shares Your Birthday?

Exhibitions

- Upcoming Exhibitions

- Traveling Exhibitions

- Past Exhibitions

Art Conservation

- Lunder Conservation Center

Research Resources

- Research and Scholars Center

- Nam June Paik Archive Collection

- Photograph Study Collection

- National Art Inventories Databases

- Save Outdoor Sculpture!

- Researching Your Art

Publications

- American Art Journal

- Toward Equity in Publishing

- Catalogs and Books

- Scholarly Symposia

- Publication Prizes

Fellows and Interns

- Fellowship Programs

- List of Fellows and Scholars

- Internship Programs

Featured Resource

- Support the Museum

- Corporate Patrons

- Gift Planning

- Donating Artworks

- Join the Director's Circle

- Join SAAM Creatives

Become a member

Features More Than 100 Artworks From the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Leading Latinx Collection

The Smithsonian American Art Museum and Renwick Gallery were closed as a public health precaution, due to COVID-19, from Nov. 23 to May 13, 2021, during the run of this exhibition. “¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now” is on view from May 14 to Aug. 8, 2021.

In the 1960s, Chicano activist artists forged a remarkable history of printmaking rooted in cultural expression and social justice movements that remains vital today. The exhibition “ ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now ” presents, for the first time, historical civil rights-era prints by Chicano artists alongside works by graphic artists working from the 1980s to today. It considers how artists innovatively use graphic arts to build community, engage the public around ongoing social justice concerns and wrestle with shifting notions of the term “Chicano.” Mexican Americans defiantly adopted the term Chicano in the 1960s and 1970s as a sign of a new political and cultural identity. Graphic artists played a pivotal role in projecting this revolutionary new consciousness, which affirmed the value of Mexican American culture and history and questioned injustice nationally and globally.

The exhibition is on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s main building from Nov. 20 through Aug. 8, 2021. It includes 119 works, ranging from traditional screenprints to digital graphics and augmented reality (AR) works to site-specific installations, by more than 74 artists of Mexican descent and other artists who were active in Chicanx networks. All of the artworks on display are part of the museum’s permanent collection of Latinx art, one of the leading national collections of its kind and one of the most extensive collections of Chicanx graphics in an American art-focused museum. This exhibition features donated artworks from major collectors and an ambitious program to purchase artworks for the collection to create an inclusive view of American art that features Chicanx voices and contributions. The exhibition is organized by E. Carmen Ramos, acting chief curator and curator of Latinx art at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, with Claudia E. Zapata, curatorial assistant for Latinx art.

The museum is limiting the number of visitors permitted in the galleries and has established new safety measures in the museum to accommodate safe crowd management and implement safe social distancing. Visitors are required to obtain free, timed-entry passes in advance and should review new safety measures online before arriving at the museum.

“Since the late 1970s, the Smithsonian American Art Museum has demonstrated a deep commitment to building a rich collection of Latinx art in the nation’s capital,” said Stephanie Stebich, the Margaret and Terry Stent Director at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. “SAAM is uniquely positioned to engage in a conversation about an inclusive view of American history that features Chicanx voices and contributions, and we are proud to present the first major museum exhibition dedicated to this subject matter from a national perspective.”

The artists in the exhibition use graphics as a vehicle to debate larger social causes, reflecting the issues of their time period, including immigrant rights, opposition to the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement and the Black Lives Matter movement. Vibrant posters and images announced labor strikes and cultural events, reimagined national and global histories, and, most significantly, challenged the invisibility of Chicanos in U.S. society. The exhibition offers an expanded view of American art and the history of graphic arts, featuring previously marginalized voices from Chicano art, including women and LGBTQ+ individuals. The influential Chicano graphics movement has been largely excluded from the history of U.S. printmaking. “¡Printing the Revolution!” challenges this historical sidelining of Chicanx artists and their cross-cultural collaborators.

“Chicano graphic artists were among the first to immerse themselves in civil rights activism, many working to support the United Farm Workers union founded by César Chávez and Dolores Huerta,” Ramos said. “The exhibition explores how this early civil rights activity set the foundation for a truly noteworthy, politically engaged graphic arts movement among artists of Mexican descent and their cross-cultural collaborators that continues to thrive today, over five decades later. At a time when U.S. society is grappling with how to face a history of systemic racism, this exhibition presents a long line of artists doing exactly that.”

“¡Printing the Revolution!” includes iconic works by major artists like Rupert García, Malaquias Montoya, Juan Fuentes, Ester Hernandez, Yolanda López and members of the Royal Chicano Air Force collective (RCAF), and later generations working after the height of the civil rights era. It features works produced at major print centers, organizations and collectives located in cities across the U.S., including Austin, Texas; Chicago; Los Angeles; New York City; Sacramento, California; San Francisco; Santa Fe, New Mexico; and Oakland, California. The exhibition is the first to consider how Chicanx mentors, print centers and networks collaborated and nurtured other artists, including multigenerational stories like that of Chicana artist Yreina D. Cervántez, who mentored her student Favianna Rodriguez, born to Peruvian immigrants in Oakland. Rodriguez herself would go on to mentor digital artist Julio Salgado, a Mexican-born artist and DACA recipient, who is well known for his work exploring the intersection of LGBTQ+ and immigrant rights.

Visitors enter the exhibition through a site-specific installation, “Justice for Our Lives,” by San Francisco Bay Area artist Oree Originol. Inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement, this artwork, which Originol also presents online and as public art interventions, includes memorial portraits of Oscar Grant, Alex Nieto, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and others killed during altercations and interactions with law enforcement. Begun in 2014, Originol continues to add portraits to the work. The project reflects a major undercurrent within Chicanx graphic arts to respond immediately to urgent concerns as they are unfolding.

The 74 artists featured in the exhibition are Lalo Alcaraz, David Avalos, Jesus Barraza (Dignidad Rebelde), Francisco X Camplis, Barbara Carrasco, Leonard Castellanos, René Castro, Melanie Cervantes (Dignidad Rebelde), Yreina D. Cervántez, Enrique Chagoya, Sam Coronado, Carlos A. Cortéz, Rodolfo O. Cuellar (RCAF), Alejandro Diaz, Dominican York Proyecto GRAFICA (Carlos Almonte, Yunior Chiqui Mendoza, Pepe Coronado, iliana emilia garcía, Scherezade García, Reynaldo García Pantaleón, Alex Guerrero, Luanda Lozano, Miguel Luciano, Moses Ros-Suárez, René de los Santos, Rider Ureña), Richard Duardo, Roxana Dueñas, Shepard Fairey, Ricardo Favela (RCAF), Sandra C. Fernández, Juan Fuentes, Eric J. García, Max E. Garcia (RCAF), Rupert García, Ramiro Gomez, Daniel González, Héctor D. González (RCAF) , Luis C. González (RCAF), Xico González (RCAF), Ester Hernandez, Nancypili Hernandez, Louis Hock, Nancy Hom, Carlos Francisco Jackson, Luis Jiménez, Carmen Lomas Garza, Alma Lopez, Yolanda López, Linda Zamora Lucero, Gilbert “Magu” Luján, Poli Marichal, Emanuel Martinez, César Maxit, Oscar Melara, Michael Menchaca, José Montoya (RCAF), Malaquias Montoya, Juan de Dios Mora, Oree Originol, Amado M. Peña Jr., Zeke Peña, Favianna Rodriguez, Sonia Romero, Shizu Saldamando, Julio Salgado, Jos Sances, Herbert Sigüenza, Elizabeth Sisco, Mario Torero, Patssi Valdez, Xavier Viramontes, Ernesto Yerena Montejano and Andrew Zermeño.

Note about terms: The museum uses the term “Chicano” to refer to the historical Chicano movement in the United States (starting roughly in 1965) and its participants. “Chicana” references women who fought for and prefer this designation. "Chicanx” is a current, inclusive designation that is gender-neutral and non-binary.

The exhibition catalog, ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now , includes essays by Ramos; Zapata; Tatiana Reinoza, assistant professor of art history at the University of Notre Dame; and Terezita Romo, an art historian, curator and writer. Co-published by the Smithsonian American Art Museum in association with Princeton University Press, it is available for purchase online ($60, hardcover and $49.99, flexicover).

Online Exhibition Resources

Throughout the run of the exhibition, the museum will release digital resources that allow online visitors to experience the exhibition virtually and learn more about its featured artists. An online gallery of selected artworks with related interpretive text in English and in Spanish offers an opportunity for closer examination of the artworks themselves. The museum’s blog “ Eye Level ” will feature a series of stories that contextualizes the history of Chicanx graphic arts and explores key concepts of the exhibition. A short video introduction to the exhibition and recorded panel discussions and artists talks will be available on the museum’s website and YouTube following their live streaming. In early 2021, the museum will present a bilingual 360-degree virtual tour of the exhibition. These resources and more will be available at AmericanArt.si.edu/exhibitions/chicano-graphics .

Public Programs

To celebrate the opening of the exhibition, an online program is scheduled for Thursday, Nov. 19, at 7 p.m. ET. The event is free, but registration is required through Eventbrite. Participants will enjoy a virtual preview of the exhibition with Ramos, before it opens to the public, and a Q&A with artists Ester Hernandez, Zeke Peña and Juan Fuentes in discussion with Ramos and Zapata. Notable collectors of Chicanx graphics Tomás Ybarra-Frausto, Gilberto Cárdenas, Harriett and Ricardo Romo, and Rosa Terrazas (representing the Estate of Margaret Terrazas Santos), who made major gifts to the museum’s collection and who saw their collecting as a form of activism, will also be part of the program. This program will be presented in English with closed captioning in English and Spanish.

Additional online events will take place throughout the run of the exhibition. Information will be available on the museum’s website, AmericanArt.si.edu/events , as details are confirmed.

Planning a Visit to the Museum

The Smithsonian American Art Museum has reopened with new health and safety measures due to the COVID-19 pandemic and a reduced weekly schedule. The museum is open five days a week, Wednesday through Sunday, from 11:30 a.m. to 7 p.m. Visitors must reserve free, timed-entry passes in advance, and masks are required while at the museum. Passes can be reserved online at si.edu/visit or by phone at 1-800-514-3849, ext. 1. An individual will be able to reserve up to six passes for personal use. Each visitor must have a pass, regardless of age. Visitors may choose to print timed-entry passes at home or show a digital timed-entry pass on their mobile device.

The museum will be closed Nov. 26 (Thanksgiving Day), Dec. 24 (Christmas Eve), Dec. 25 (Christmas Day) and Jan. 20, 2021 (Inauguration Day). The museum’s store and its café remain closed at this time, and the museum’s entrance at Eighth and F streets N.W. is closed. All visitors must enter at Eighth and G streets N.W. Additional information is available on the museum’s website at AmericanArt.si.edu/visit .

“¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now” is organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum with support from Michael Abrams and Sandra Stewart, The Honorable Aida Alvarez, Joanne and Richard Brodie Exhibitions Endowment, James F. Dicke Family Endowment, Sheila Duignan and Mike Wilkins, Ford Foundation, Dorothy Tapper Goldman, HP, William R. Kenan Jr. Endowment Fund, Robert and Arlene Kogod Family Foundation, Lannan Foundation, and Henry R. Muñoz, III and Kyle Ferari-Muñoz. Additional significant support was provided by the Latino Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Latino Center.

About the Smithsonian American Art Museum and its Renwick Gallery

The Smithsonian American Art Museum is the flagship museum in the United States for American art and craft. It is home to one of the most significant and inclusive collections of American art in the world. The museum’s main building, located at Eighth and G streets N.W., is open daily from 11:30 a.m. to 7 p.m. The museum’s Renwick Gallery, a branch museum dedicated to contemporary craft, is located on Pennsylvania Avenue at 17th Street N.W. and is open daily from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Check online for current hours and admission information . Admission is free. Follow the museum on Facebook , Instagram , Twitter and YouTube . Smithsonian information: (202) 633-1000. Museum information (recorded): (202) 633-7970. Website: americanart.si.edu .

Press Images

Leonard Castellanos, RIFA, from Méchicano 1977 Calendario, 1976, screenprint on paperboard, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, 2012.53.1, © 1976, Leonard Castellanos

Tomas Ybarra-Frausto Research Material on Chicano Art

In 1997, the Archives of American Art received a donation of 20 linear feet of research material on the Chicano art movement in the United States and Latin America, compiled by Dr. Tomás Ybarra-Frausto. Ybarra-Frausto was a professor at Stanford University in the department of Spanish and Portuguese and has published extensively on Latin American and U.S. Latino culture. Selected items from this collection were exhibited at the Archives New York Research center in the fall of 1998.

For more information about the materials found in Ybarra-Frausto?s extensive files, see the collection description: Tomás Ybarra-Frausto research material on Chicano art, 1967-2008 bulk 1970-1985

Carmen Lomas Garza

Pharr, Texas by Felipe Reyes

Peace on Earth Good Will Towards Men aka Instant Genocide by Felipe Reyes

Fast Buckaroo Politics by Felipe Reyes

Rising Sun of San Juan by Felipe Reyes

Catalog for The Broken Line's The Latino Boom...Boom!!

"Look up Latinas" satiricial artwork from Heresies magazine

Southside Park Mural by Juan Cervantes

Royal Chicano Air Force Retrospective Poster Art Exhibition

Chicanarte: statewide exposicion of Chicano art

The panel 'Artistic Expressions in the Barrio' at the Califas conference on Chicano art and culture in California, held at the University of California at Santa Cruz

Photograph of Carlos Loarca and Rupert García in Balmy Alley, San Francisco

Exhibition chronology.

Read the full chronology of exhibitions organized by the Archives of American Art.

The Lawrence A. Fleischman Gallery

The Archives of American Art’s exhibition space is located two blocks away from our D.C. Research Center in the Donald W. Reynolds Center for American Art and Portraiture (8th and F Streets NW).

Please visit www.si.edu/visit for more information and to review safety requirements before your visit.

Learn more about visiting the gallery .

Hours: Open daily 11:30 a.m.–7:00 p.m.

Admission: Free

Documents of Latin American and Latino Art

International center for the arts of the americas at the museum of fine arts, houston.

Explore over 9,000 Documents of 20th and 21st-century art in Latin America, the Caribbean, and among US Latino communities

A critical perspective on the state of Chicano Art

Document main title, icaa record id.

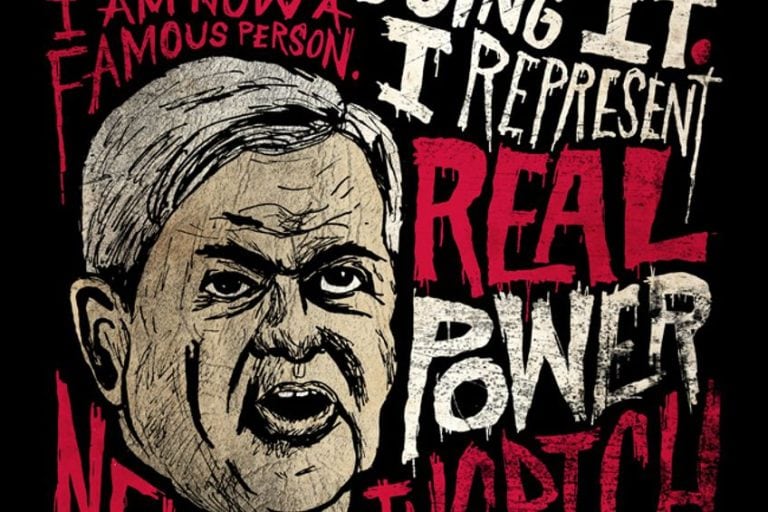

This manifesto written by Chicano artist Malaquías Montoya and his wife, Lezlie Salkowitz-Montoya, derides the developing trend of Chicano artists moving away from a community focus to individual artistic pursuits. According to the Montoyas, the United States capitalist system of oppression requires Chicano artists to produce an art of protest. They caution against the emerging trend of exhibiting and selling art within a mainstream art market that is part of a political and economic system that continues to oppress Third World communities. It also historicizes Chicano art; that is, it outlines its origins and development over the last decade, not only within Chicano/Mexican American art history, but also as part of the international artist sociopolitical movements. It concludes with a call to artists to reaffirm the original goals and values of the Chicano movement to make an art in service of the community that is also a catalyst for social change.

Annotations

This essay by the Montoyas is an important resource for understanding the development of Chicano art. It is the first document to provide one of the most thorough articulations by artists about the role of Chicano art in transforming individuals, as well as entire communities. From its publication, it incited a furious and long-lasting debate on the definition of Chicano art. There were essays in support (Pedro Rodriguez’s Arte Como Expresión del Pueblo ) and counter-perspectives published (Shifra M. Goldman’s Response: Another Opinion on the State of Chicano Art ). Even today, it resonates as one of the key documents that attest to the myriad definitions already in circulation by 1980 and to the reality that Chicano art was never monolithic. This document is also a good example of the role of university-based centers, in this case the Centro de Estudios Chicanos at the University of Washington, in promoting Chicano art and literature, and generating important dialogue among artists, activists, and historians.

Metamórfosis (Seattle, Washington, United States). -- Vol. 3, no. 1 (1980)

Digitized from

Malaquias Montoya and Lezlie Salkowitz-Monoya. "A critical perspective on the state of Chicano Art." Metamórfosis (Seattle, Washington, United States), 3, 1 (1980): 6-7

Before you download

By downloading or printing this document, you expressly agree that your intended use is private, non-commercial, and educational in nature; that you have reviewed the United States Copyright Office circular on fair use of copyright, located at the website: http://www.copyright.gov/fls/fl102.html ; and that you shall indemnify, defend, and hold MFAH and ICAA and their representatives harmless from all claims, allegations, costs, expenses, fees, judgments, liabilities, losses, and damages arising from or relating to your intended use of the downloaded or printed document.

Or cancel the download .

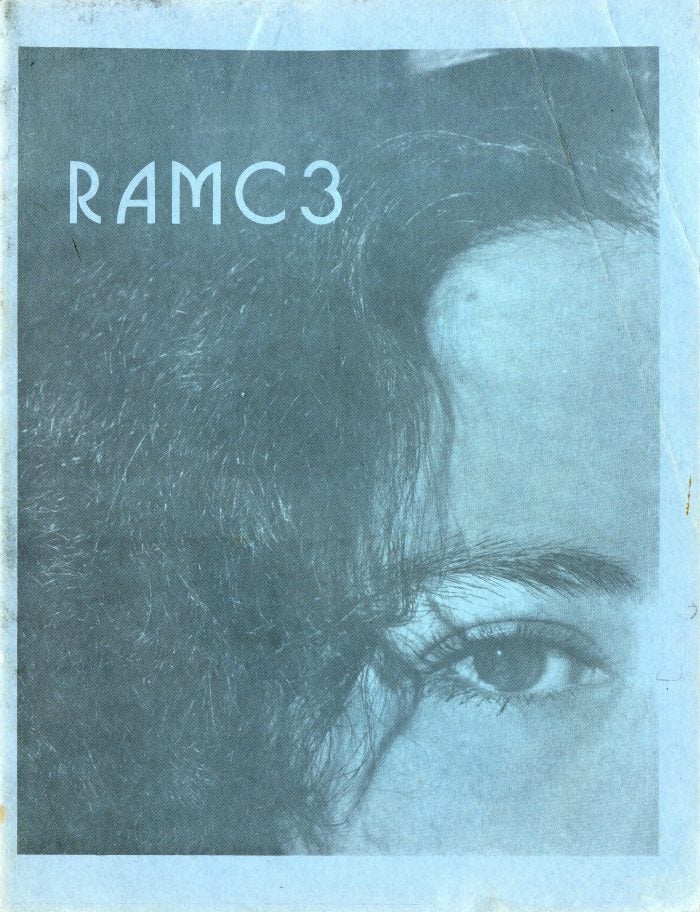

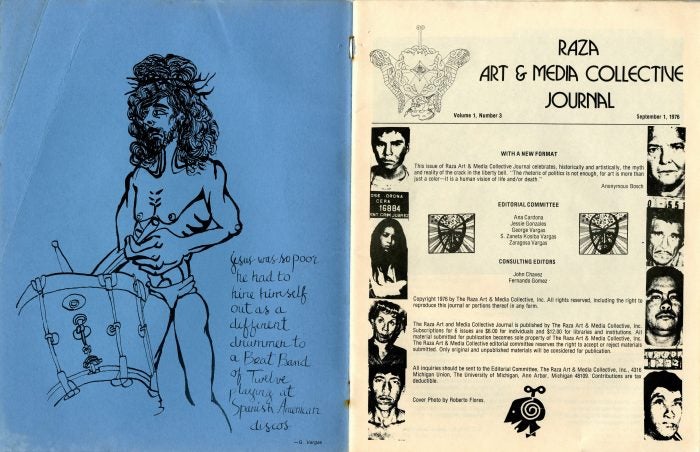

Chicano Art? At Michigan?: The Raza Art and Media Collective

The Chicano movement history has largely been painted as a Southwest/West Coast phenomenon. Even famous Chicano poet Alurista commented after the Denver National Youth Conference of 1969 how, “he was surprised to learn that Mexicans came from exotic places such as Kansas City and Chicago.” 1 Who would have guessed that another one of those “exotic places” would be none other than the University of Michigan, out of the needs of Latino students with an interest in art and media. In 1974, Michigan students Ana Cardona , Zaragosa Vargas, Michael J. Garcia, Jesse Gonzales, George Vargas , Julio Perazza, and S. Zaneta Kosiba Vargas came together to form the Raza Art and Media Collective (RAMC). Despite their relatively short run from 1974-1977, the RAMC gained national recognition for it’s art journal publication by the same name. Started out of growing frustrations from Art History graduate student Ana Cardona, RAMC pulled together a group of Michigan based artists interested in carving a space within an institution that neglected their needs as Latinos. Proud Nuyorican Ana Cardona insisted on the use of the term “Raza” in RAMC because it was more inclusive of all Latinos. For her, it was important that RAMC as an organization not be limited to Chicanos or the larger Chicano Movement terminology. The more inclusive terminology would extend to build solidarity among all Latina/os peoples. 2

This historia examines the Raza Art and Media Collective through the archival collections of the Ana Cardona, and George Vargas at the Bentley Historical Library, oral interview with Ana Cardona recorded in the Chicana por mi raza archive and interview with George Vargas. These materials help tell a three-part story about an important regional Latina/o art movement that intersected with RAMC members Felipe Reyes and Santos Martinez of San Antonio’s Con Safos art group; LA based performance art group ASCO ; and the later contributions of younger member George Vargas and his involvement in the landmark CARA Chicano Art Resistance and Affirmation 1965-1985 .

Early Roots: Flustered Chicano Art Students and MEChA

In Ana Cardona’s oral history she notes that prior to forming the RAMC, she was in conversation with current University of Michigan art graduate students Felipe Reyes and Santos Martinez. Originally from Texas, Reyes and Santos were coming from the then defunct 1972-1975 Chicano art group called Con Safos (meaning with respect). For Cardona and Vargas, their exposure to these artists and their organizing background was very influential towards the formations of the RAMC. Cardona notes that following RAMC volume 1 #2 , Reyes and Santos were very invested in the aesthetics of creating a unique arts publication.

was the first time we see the collective publish something far from its initial six page newsletter format. Cardona argues that this desire to create was sparked from a negative review the two artists had received in the first book written on Chicano art, Jacinto Quirarte’s Mexican American Artists (1973). While definitely considered a novel feat at the time, Quirarte’s text was met with some resistance. Upon speaking to RAMC member, George Vargas, he speculates that Quirarte had the laborious task of defining Chicano art at a time when the term was very controversial. He concludes that Quirate’s text, while very important, did not rub well among artists who aligned themselves with the activist initiatives set by the Plan Espiritual de Aztlan . 3 In this point in time, even amidst the Chicano movement happening in the background, many artists were discouraged from aligning themselves with terms like “Chicano.” Starting from this rocky beginning, early 1970s, 180s art historians such as Shifra Goldman and Jacinto Quirate had to legitimize what we now know as “Chicano art” by first connecting it to Mexican art history in order to establish it as a discipline.

Prior to the creation of RAMC as a formal student organization, RAMC’s initial members had already became vocal regarding Latino and Raza art. A few years before their first 1976 RAMC publication, RAMC members were featured in a University of Michigan MEChA newsletter titled Art and La Raza . Published in 1974 through the Chicano Advocate office at the University of Michigan, Art and La Raza featured artwork by George Vargas, articles by RAMC members Ana Cardona, Jesse Gonzalez, Felipe Reyes, interview with Julio Peraza, and featured spotlight on 1899 Law School graduate J.T. Canales. Reyes’s article in this newsletter Patronage: Chicano Art and Its Consumption voiced his concerns regarding the role of art among la Raza. For Reyes, the exclusion of Chicano art will continue if artists rely on “gavacho patrons” instead of establishing the importance of art in Chicano within their communities.

Aside from her role as an Art History graduate student at the University of Michigan, Cardona notes how her involvement in the arts extended to her work in theatre. In the retelling of the Felipe Reyes and Santos Martinez collaboration with the RAMC, she notes how her true inspiration for starting a Raza arts organization stemmed from the comfort she felt on the set of a student recruitment video sponsored by the University of Michigan’s Chicano Advocate Office. The short film features a segment where university students play with the genre of Teatro Campesino, a rasquache , 4 low budget style of theatre that was popularized by United Farmworker Movement and performed on the backs of pick-up trucks to farmworkers in the fields as a means to educate them on the injustices of non-unionized agricultural labor.

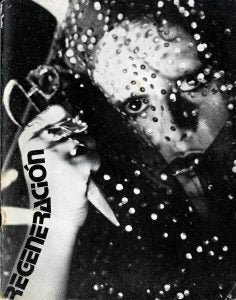

ASCO: Your Journal Disgusts me!

According to Art Historian Olga Herrera, a popular trait of the latter two issues of RAMC were it’s inclusion of the work of the art group ASCO. 5 Similar to RAMC, ASCO also had an arts publication. ASCO first started when Harry Gamboa jr. approached high school friends and artists Patssi Valdez, Gronk and Willie Herron to publish the first issue of their publication Regeneracion. 6 ASCO, meaning “it (your art) disgusts me,” 7 is most notably known for their status as a subversive performance art group playing on public perceptions of what Chicano art is and shouldn’t be.

As a step away from it’s smaller newsletter format, RAMC volume 1, #2 features a call for artists and writers to contribute to the RAMC journal. Immediately after this issue we start to see the black and white collage of ASCO 8 appear in RAMC materials. In the RAMC journal we see snapshots of ASCO’s famous ads for their No Movies , fake ads for movies that did not exist but featured ASCO’s members as commentary on the lack of representation of Chicanos in the media. RAMC member George Vargas notes that the exposure of Michigan based artists to the work of ASCO introduced them to a “new wave” of Chicano art and what it could look like. 9 RAMC member and American Culture graduate student Zaneta Kosiba-Vargas would later go on to write her dissertation, “Harry Gamboa and ASCO: The Emergence and Development of a Chicano Art Group, 1971–1987,” (1988). RAMC members George Vargas (1988) and Zaragosa Vargas (1984) also graduated from American Culture’s PhD program with dissertations in Latino studies.

Beyond RAMC: George Vargas and CARA Chicano Art Resistance and Affirmation 1965-1985

Although George Vargas was an undergraduate around of the RAMC’s inception, Vargas still managed to be involved and provide artwork for various RAMC’s publications. In the first issue of RAMC, Vargas was the creator of the RAMC logo that would later adorn the group’s official letterhead. Beyond his artistic contributions to RAMC, George Vargas went on to work as an art historian. As a graduate student in the Department of American Culture, RAMC Vargas’ dissertation titled Latino Art in Michigan references the work of RAMC affiliated members and helps historize earlier artists like Carlos Lopez—a WPA muralist in the 1930s who later joined the art faculty at the Art and Design school at the University of Michigan—as important antecedents in the Midwest Latina/o arts movement. Vargas’ time at the University of Michigan undeniably influenced his larger observations regarding the art networks of Latino artists in the Midwest. 10

George Vargas’ archive of donated teaching curriculum at the Bentley document his involvement in the El Paso steering committee for the traveling exhibition CARA: Chicano Art Resistance and Affirmation 1965-1985 . CARA traveled to ten major cities from 1990-1993, and for the first time in history, U.S. museum audiences got a chance to view a Chicano art exhibition in mainstream art institutions. Although created long after the run of the RAMC, the date range of the CARA exhibit content, 1965-1985, encompasses the aesthetics and art activism that greatly impacted the work and arts initiatives of the RAMC.

So immersed with this moment in Chicano art history, one of Vargas’ assignments in his miscellaneous files is a CARA research paper assignment that asks students to pick an artwork from the CARA exhibition catalog. Vargas notes that this exhibition was the first Chicano art blockbuster exhibition that laid the groundwork for a nuanced definition of Chicano art as American art. Reflecting on his experience with the 1992 CARA exhibition in El Paso, he notes how the El Paso Museum of Art had recently come under fire after a newspaper article documented a museum board member speaking negatively of the work of Chicana artists Carmen Lomas Garza . Involved in the community outreach for the CARA exhibition in El Paso, Vargas notes how the openings reception was so well attended and brimming with Latinx museum visitors who had never seen themselves reflected in the El Paso museum collection. In line with the RAMC commitment to creating and supporting spaces for celebrating and educating the public about Raza art, the CARA exhibition was a major milestone in U.S. history.

Far from the Chicano movement imaginary, the Raza Art and Media Collective is a unique slice of the rasquache art history of the University of Michigan history. Despite it’s Ann Arbor location, RAMC drew from influences and networks that extended as far away as Chicago, San Antonio and LA to create a larger regional network of the Chicano art movement.

Wanna learn more about the topics covered above?

Check out this list of Recommended Reading!

Raza Art and Media Collective

Herrera, Olga U., and University of Notre Dame Institute for Latino Studies. 2008. Toward the Preservation of a Heritage: Latin American and Latino Art in the Midwestern United States . Institute for Latino Studies.

Chavoya, Ondine. 2000. “Orphans of Modernism: The Performance Art of Asco.” In Corpus Delecti: Performance Art of the Americas . Psychology Press.

McMahon, Marci. 2011. “Self-Fashioning through Glamour and Punk in East Los Angeles: Patssi Valdez in Asco’s Instant Mural and A La Mode.” Aztlan: A Journal of Chicano Studies 36 (2): 21–49.

CARA exhibition

Alba, Alicia Gaspar de. 2010. Chicano Art Inside/Outside the Master’s House: Cultural Politics and the CARA Exhibition . University of Texas Press.

1 Ramirez, Leonard G., Yenelli Flores, Maria Gamboa, Isaura González, Victoria Pérez, Magda Ramirez-Castañeda, and Cristina Vital. 2011. Chicanas of 18th Street: Narratives of a Movement from Latino Chicago . University of Illinois Press. (page 1).

2 Cardona, Ana. “To Our Audience.” RAMC volume 1 #1 Ann Arbor, (January 1, 1976): 1.

3 Phone interview with George Vargas April 22, 2018.

4 This term was later used exclusively to refer to Chicano art in an article by art critic Tomas Ybarra-Frausto. Rasquache is a DIY Chicano art sensibility that uses surrounding materials and lived experiences of Chicanos to create art. It is art based in community circulation and in conversation with the quotidian aesthetics of Mexican culture.

5 Herrera, Olga. n.d. “Raza Art & Media Collective: A Latino Art Group in the Midwestern United States.” Institute for Latino Studies, University of Notre Dame, Indiana. Accessed March 16, 2018. https://icaadocs.mfah.org/icaadocs/Portals/0/WorkingPapers/No1/Olga%20U.%20Herrera.pdf.

6 Chavoya, Ondine. 2000. “Orphans of Modernism: The Performance Art of Asco.” In Corpus Delecti: Performance Art of the Americas . Psychology Press.

7 Noriega, Chon. Nov.18, 2010. “Your Art Disgusts Me: Early Asco 1971-75.” East of Borneo. https://eastofborneo.org/articles/your-art-disgusts-me-early-asco-1971-75/.

8 ASCO’s aesthetic was very informed by the cut and paste nihilistic style of Dada movement artists.

9 George Vargas dissertation

10 Vargas, George. Spring 2915. “¿ Qué Onda?“What’s Happening?” Chicano Art in Twenty-First-Century America Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies. UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.

Chicano Art – Discover the Mexican American Art of Chicano Painters

The Chicano art movement refers to the ground-breaking Mexican-American art movement in which artists developed an artistic identity, heavily influenced by the Chicano movement of the 1960s. Chicano artists aimed to form their own collective identity in the art world, an identity that promoted pride, affirmation, and a rejection of racial stereotypes. The most well-known and famous Chicano artists include Carlos Almaraz, Chaz Bojórquez, Richard Duardo, Yreina Cervántez, and Magú. Chicano artists developed their works to exist as a form of a community-based representation of life in the barrio, but it also acted as a form of activism for social issues faced by Latin-American people in the United States.

Table of Contents

- 1 The Chicano Art Movement

- 2.1 Chicano Art as a Form of Activism

- 2.2 Chicano Art as an Expression of Community

- 2.3 Chicano Art as an Expression of Cultural Identity

- 2.4 Chicano Art as an Expression of Life in the Barrio

- 3.1.1 El Fireboy y el Mingo (1988)

- 3.2.1 Europe and the Jaguar (1982)

- 3.3.1 Placa/Rollcall (1980)

- 3.4.1 Aztlan (1982)

- 3.5.1 Homenaje a Frida Kahlo (1978)

- 3.5.2 La Ofrenda (1989)

- 4.1 What Does the Term Chicano Mean?

- 4.2 Why Is Chicano Art Important?

- 4.3 When Did the Chicano Art Movement Start?

- 4.4 What Was the Main Purpose of the Chicano Art Movement?

- 4.5 What Are Chicano Murals?

- 4.6 What Constitutes Chicano Art?

The Chicano Art Movement

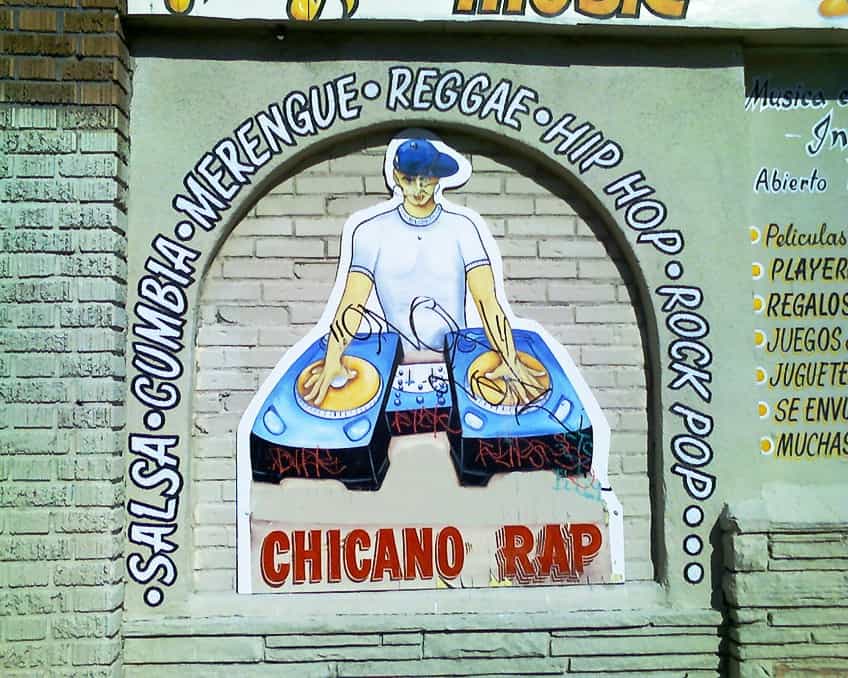

The Chicano art movement began in the late 1960s and early 1970s, alongside the growth of the Chicano movement, or El Movimiento, and was created and defined by Mexican people, or people of Mexican descent living in the United States. The term “Chicano” is used interchangeably with “Mexican-American”, emerging from the youth who rejected assimilation to the Euro-Centric American culture. The term was widely used in the 1960s and 1970s and became associated with indigenous pride, culture affirmation, ethnic solidarity, and political empowerment.

The Chicano art movement involved Chicano artists forming and establishing a specific and unique artistic identity, that diverted from the mainstream United States art forms.

As the movement was meant to represent a rejection of the White-American culture and its forms of art, the Chicano movement aimed to form and develop a collective identity that distinguished itself as Mexican-American. Chicano muralists and Chicano painters drew their inspiration from Mexican murals and Pre-Columbian Art. Pre-Columbian art refers to works made by the Aztec, Inca, Mayan, and Native Mexican people.

These communities, all native to Latin America or South America, were heavily disrupted by the colonization by the Spanish conquistadors. The Chicano movement, and by extension, the Chicano art movement aimed to reject the dominant White American culture, which their ancestors were unable to do when the Spanish invaded. Chicano artists developed their work as an expression of their experiences and culture.

Often, Chicano art drawings feature the subject of “rasquachismo”, which refers to the Spanish word, “rasquache”, which means “poor”.

Rasquachismo refers to the cultural attitude to always be hard-working and resourceful, getting by with the few resources they tend to have in a society dominated by wealthy White Americans. In other words, the Chicano art movement was meant to be a form of protest, with the artwork often being very direct and vibrant. Chicano mural paintings not only promoted community in their subject matter but often involved community members in their creation; discussing and formulating what they wanted to depict based on their cultural history and struggles.

These murals were often painted by self-taught artists, which again shows the movement’s value for resourcefulness. These murals were usually painted on public walls, where entire communities would be able to see by walking or driving by. The public nature of this art form emphasized histories that were often overshadowed by the White-American narrative, which tended to present historical events in a pro-European light. This public nature allowed for audiences to be politicized and mobilized without expecting them to go into an art gallery or museum.

Besides murals, Chicano artists also used silkscreen creations, which allowed for the production of posters and printed images, that could be distributed in large numbers, spreading the political and social aspect of the Chicano movement.

The subject matter of Chicano art commonly features imagery relating to issues of immigration and displacement, issues that the Latin communities of the United States often dealt with. Mexicans often struggle with immigration to the United States and native Mexicans and South Americans were being displaced by Spanish and Portuguese colonization.

The works of Chicano art also specifically depicted the human rights violations faced by the Mexican Americans in the Southwest of the United States, including racial profiling, as well as xenophobic immigration issues faced by undocumented immigrants about the militarization of the border. By 1990, Chicano art began to gain significant exposure, with a traveling exhibition called Chicano Art: Resistance and Affirmation. The exhibition opened at the University of California, Los Angeles, at the Wight Gallery.

The committee stated that “Chicano art is the modern, ongoing expression of the long-term cultural, economic, and political struggle of the Mexicano people within the United States. it is an affirmation of the complex identity and vitality of the Chicano people.” The movement continues to this day, with Chicano artists evolving alongside the subject matter, incorporating newer social issues as they come up in a society that continues to be dominated by the White-American culture, and oppresses Mexicans and other Latin-Americans.

Contemporary Chicano art features a broad range of subject matter, as well as many different mediums.

History of the Chicano Art Movement and Its Forms

The Chicano movement, at its core, was a socio-political movement in which Mexican-Americans came together as a unified entity to create a change for their people. The movement dealt with several issues the Mexican and Latin-American communities faced in the US, such as civil rights issues, the lack of social services that were available for Mexican-Americans, issues of educational rights and quality, as well as police brutality, and the Vietnam War.

The movement was open to all Mexican-Americans, regardless of age or gender, which allowed for discussions on generational issues, as well as the rights of women.

Young artists who took part in the Chicano art movement formed collectives, as the art movement aimed for collective identity and community, such as Asco, a collective located in Los Angeles, California in the 1970s. Asco was a group of high school graduates who were pursuing and contributing to the Chicano art movement.

Another group, known as the National Farm Workers Association, or the NFWA, aimed to unionize Mexican-American workers and servicemen, to improve working conditions and wages. The group was founded by César Chávez, Dolores Huerta, and Gil Padilla, who organized protests, marches, strikes, and boycotts to raise awareness on a national scale.

They made use of symbols, such as the black eagle, and produced posters and union art, which all were incorporated into Chicano art and vice-versa.

Chicano Art as a Form of Activism

Although the Chicano movement dwindled as time went on, the art movement continued to thrive as an outlet for activism, constantly bringing attention to and challenging the dominant social constructions of race and ethnic discrimination, as well as issues of citizenship, gender roles, and the exploitation of labor. This activism through art was expressed by representing alternative narratives and subject matter.

Featuring the Mexican-American as the focus of pieces was in itself new to the more White-Dominated subject matter of the contemporary art forms, but Chicano art also highlighted illustrations of historical injustices and human rights violations that the Mexican-American people faced, becoming a tool of both artistic expression as well as education for audiences who may not be informed on the matter.

Chicano artists often spread their messages through silk-screen posters, which were mass-produced in large quantities, for public consumption, which helped to spread the message of the movement.

Bringing light to these social issues is the first step to bringing about change, and also made Mexican-Americans feel more empowered to fight for their freedom and construct their own identity and solutions. Another example of how Chicano art was used for activism was in the case of the Chicano People’s Park in San Diego, California. The Mexican-American neighborhood of Logan Heights had petitioned for a community park for years but was completely ignored.

Instead, the city began to construct an intersection for the interstate five freeway and an on-ramp for the Coronado Bridge in the 1960s. They tore down large areas of the suburb, displacing 5000 Mexican-American residents. Along with planned peaceful protests, Chicano muralist Victor Ochoa painted murals on the concrete walls in the area, which featured historic Chicano figures such as Cesar Chavez and La Virgin de Guadalupe .

Eventually, the city agreed to the development of a park, with Activist and artist, Salvador Torres establishing the Chicano Park Monumental Mural Program, which encouraged Chicano artists to fill the park with murals.

These murals highlighted the park’s heritage and community with Mexican-American art, including Chicano figures such as the indigenous Aztec imagery, like Coatlicue, the Aztec Earth Goddess.

Chicano Art as an Expression of Community

Chicano art is a form of cultural art, expressing community values and unity amongst Mexican-American people. With the example of the Chicano People’s Park, all the art displayed throughout the park focus on community-oriented ideas, with murals created by Chicano muralists and painters. These murals usually encourage a sense of community participation, often involving other Mexican-Americans in the development and creation of the murals, whether that be formulating ideas for the subject matter or actually painting the murals themselves.

The Chicano art movement is considered widely to be a community-based movement, which has developed into two significant mediums; muralism, which refers to the large paintings or murals painted on walls in public spaces and cultural art centers.

These centers developed during the Chicano movement to act as a space for alternative structures that supported Mexican-American artists, as well as artistic creation in general. These cultural art centers also aided in the unification of communities and helped spread information on the Chicano movement and its messages.

These centers not only encouraged and created a space for community gatherings but also acted as a cultural space; where Chicano artists, muralists, and enthusiasts could engage in discussions and dialogues on the Chicano movement as it developed. It also acted as a space for Mexican-Americans to discuss issues and topics that were coming up in Mexican-American communities in general.

The Self-Help Graphics and Art Inc. center is an example of one of these cultural centers, which served as a venue for silkscreen printmaking as well as a space for housing art exhibitions.

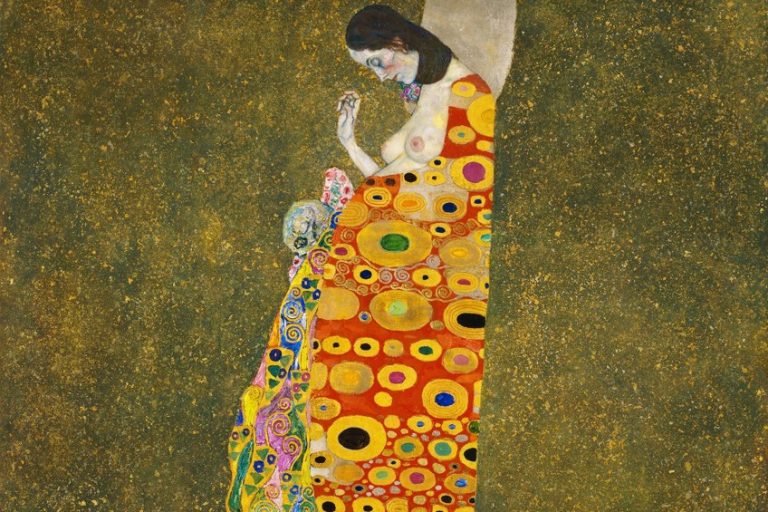

Chicano Art as an Expression of Cultural Identity

As previously stated, Chicano art serves as an expression of identity and cultural affirmation for the Mexican-American people. One way this is expressed in the art is through the Chicano artist’s and muralist’s use of religious imagery. This includes both the indigenous religions of the Aztec, Inca, and Mayan people, as well as Catholicism, which has become a significant element of Mexican culture.

One popular religious figure that often features in Chicano paintings and murals is La Virgen de Guadalupe, or the Virgin of Guadalupe, who is a very prominent figure in Mexican culture.

This was often used to represent hope during difficult times, or even empowerment, particularly female empowerment. Both Mexican, as well as Indigenous Latin-American cultures often celebrate their religious heritage through the use of shrines.

The Chicano art movement has taken the idea of shrines, with its religious imagery, and incorporated it into its murals, often making use of the same type of compositions.

An important cultural and religious holiday within the Mexican culture is what is known as the Day of the Dead, which focuses on family by remembering and honoring their ancestors and loved ones who have passed away. This holiday is celebrated alongside the Catholic All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day, which takes place from November 1st to November 2nd. As this day is a highly honored day within the Mexican culture, it is often featured as the subject matter of Chicano art.

Chicano Art as an Expression of Life in the Barrio

The word barrio is a Spanish term that means “quarter” or “neighborhood”, referring to the city areas that are inhabited by Spanish-speaking citizens. In the modern form of the Spanish language, Barrio usually refers to areas that are delimited by functional, social, or architectural features.

In the United States specifically, barrios refer to inner-city areas that are dominantly populated by Mexican-American, or Latin American, people, often referring to first-generation immigrant families that have not assimilated into the mainstream White American culture. Examples of these inner-city areas include East Los Angeles, Segundo Barrio in Houston, and Spanish Harlem, New York City.

Chicano art often features representations of life in the Barrios.

These areas often have histories of oppression, marginalization, inequity, poverty, gang violence, and dislocation. This art is often expressed by the community, often with the medium of graffiti. Graffiti is generally considered to be a form of vandalism, with Barrios especially, as graffiti is often used by gangs as marks of territory, marking unofficial borders.

Chicano art embraced this, however, as it is usually associated with the rebellion against authority. Chicano artists used graffiti to express their political opinions, as well as their native history and religious iconography.

Thus, graffiti within the barrios became culturally affirming, promoting Latin heritage, facilitating dialogue, and bringing light to injustices that have affected the Mexican-American communities. Graffiti has recently been reclaimed as a form of public art. Art museums and galleries have embraced graffiti, with many artists featuring forms of graffiti in their work. The medium has become recognized by both art institutions and art critics.

Notable Artists and Artworks of the Chicano Art Movement

The Chicano Art movement was built from the ground up, founded by a generation of artists within the Chicano community, the 1960s and 1970s saw some of these artists rise, gaining praise and recognition for their culturally affirming works. Artists like Carlos Almaraz had their work gain so much recognition that they were accepted into the mainstream art scene, joining American art galleries.

Today, many of these artists and their works can be found at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Magú (1940 – 2011)

Gilbert Luján, also known as “Magú”, was a dedicated Chicano artist and intellectual who helped to establish the Chicano art movement in the 1960s and 1970s. He was born to Indigenous Mexican parents but grew up in Los Angeles, where he studied art and ceramics at East Los Angeles College, as well as California State University.

Magú is considered a visionary for the Chicano art movement, painting murals and creating public art installations all around Los Angeles and California, before joining Los Four.

His work had a major influence on the movement, defining the general art style and aesthetics. In 1969, as the Chicano art movement was rising, Magú noted that there was a Chicano art form that had existed for years, without formalization and recognition. He continued to explain that the awareness of one’s “cultural linkage” to Mexico and India illustrates that “the Chicano culture is a real and identifiable body.”

Magú’s art is praised for its rich texture of cultural history, often seen in his use of color and imagery.

These are often incorporated traditional brut and folk art , as well as indigenous Latin American Mythology. His most recognizable trademark is the figure of an anthropomorphized dog figure, similar to those seen in Ancient Egyptian mythology, which is meant to represent indigenous Mexican mythology.

El Fireboy y el Mingo (1988)

This Chicano art drawing perfectly embodies Magú’s rich use of color about his cultural history. The inclusion of the anthropomorphized dog character also highlights indigenous Mexican mythology. The title of this Chicano art drawing translates to “the fireboy and the mingo”.

The word “mingo” in the Spanish language is used to describe men that are well-dressed and composed.

This gives the piece a sense of irony, in that there is decency and composure in the more indigenous-representative character. This piece is currently housed at the Smithsonian Art Museum but is currently not on view.

Carlos Almaraz (1941 – 1989)

Carlos Almaraz was an artist and leading figure of the Chicano art movement in the 1970s. Born in Mexico City before immigrating to East Los Angeles with his family, Almaraz earned his Master’s in Fine Arts from Otis College of Art and Design. He was involved in the political activist part of the movement as well, producing banners, posters, paintings, and murals for the rallies in support of Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers labor union. He also was involved in Luis Valdez’s Teatro Campesino and Mechanicano, which was a cooperative Chicano art gallery in East Los Angeles.

Almaraz, along with a few other Chicano artists, founded the local Chicano art collective, Los Four, which brought the movement to the attention of the Los Angeles art scene.

Almaraz, along with Chicano muralists Frank Romero, Gilbert “Magú” Luján, and Robert de la Rocha, painted public murals throughout the city, which featured representations of the civil rights issues faced by Mexican-Americans, with the expressive use of bold colors, with purple , pink and orange hues commonly used.

Europe and the Jaguar (1982)

This Chicano artwork is an oil painting that shows Almaraz’s, as well as other Chicano painters’, expressive use of bold colors, as seen with the bright orange representation of the jaguar in comparison with the blue European figure. This work is currently housed at the Smithsonian American Art Museum but is currently not available for viewing.

As Chicano painters often used their paintings to express their culture and politics, this piece clearly shows the juxtaposition between the European colonizers, or even the White Americans, and the native Mexican and Central American people.

Chaz Bojórquez (1949 – Present)

Charles Bojórquez, also known as “Chaz” is a Chicano painter and graffiti artist, and is one of Los Angeles’ first well-known graffiti artists. He is widely credited as one of the prominent artists that brought the Chicano art movement to the attention of the mainstream.

Beginning his career in the 1970s, he would tag the name ‘Chaz’ around Highland Park in Los Angeles, which translates to “the one who messes things up and likes to fight.”

He went on to study art at the University of Guadalajara as well as California State and Chouinard Art Institute. His work was highly influenced by the Chicano artists that came before him, such as Gilbert “Magu” Luján.

Chaz is most known for his work in Cholo-style calligraphy. This style is considered to be one of the oldest forms of the medium, having been invented in the 1940s by Mexican-American gang members as marks of territory. These often included roll calls or lists of gang members.

Chaz studied Asian calligraphy at the Pacific Asian Art Museum and visited more than 30 countries to develop his signature style, looking at how other cultures incorporated culture and identity into their calligraphy, graphics, and letters. Bojórquez, along with other Chicano artists, all developed their style of graffiti art, and this eventually went on to be known as West Coast Cholo , which was heavily influenced by Mexican muralism and pachuco placas , which refers to tags indicating territorial boundaries, a homage to how the Mexican-American gang members would mark their territories.

Placa/Rollcall (1980)

This artwork was inspired by the graffiti made by gang members throughout the barrios, with Bojórquez listing his mentors and friends on the roll call, in the same way, that these graffiti artists would list the members of their gangs. The term placa refers to the denotation of territory and neighborhood loyalty.

This connection between graffiti and Chicano art represents how the movement expresses the culture, incorporating traditional calligraphic forms in the piece.

Richard Duardo (1952 – 2014)