Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Family financial management involves decisions based on both economic and social factors, including the quality of life and well-being of all family members. Family composition changes throughout the life course of people, including formation and re-formation, and are affected by laws, regulations and policies at multiple levels, from local or national. Six case studies were developed for students to critically think about and through the myriad of decisions that diverse families make as manage their lives and financial resources. Each case study features a different family type: a relocating family with same-sex parents, an uncoupling family with heterosexual parents, widowhood, coupling, a divorcing gay couple, and a single parent family all within the context of current events in the U.S. For each, students are asked by their employer or in a professional role to prepare a report that makes use of highly credible and trusted sources of information and a chart or table as well as a recommendation for the family. To further student learning, four reflection questions were also developed.

If you’re adopting our textbook, follow this link to share your adoption details.

Family Financial Management Case Studies (an OER resource) Copyright © 2023 by M. E. Betsy Garrison is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Special Issues

- Supplements

- Virtual Collection

- Online Only Articles

- International Spotlight

- Free Editor's Choice

- Free Feature Articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Calls for Papers

- Why Submit to the GSA Portfolio?

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Advertising

- Reprints and ePrints

- Sponsored Supplements

- Journals Career Network

- About The Gerontologist

- About The Gerontological Society of America

- Editorial Board

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- GSA Journals

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Conclusion and implications, acknowledgments, conflict of interest.

- < Previous

Successful Family-Driven Intervention in Elder Family Financial Exploitation: A Case Study

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Tina R Kilaberia, Marlene S Stum, Successful Family-Driven Intervention in Elder Family Financial Exploitation: A Case Study, The Gerontologist , Volume 62, Issue 7, September 2022, Pages 1029–1037, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab145

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The prevalence and consequences of elder family financial exploitation reinforce the need for a range of effective intervention strategies. This article describes how and why one family successfully intervened in the family-based financial exploitation, constructing, and achieving meaningful processes and outcomes for the specific family and context.

Case data analysis and interpretation were guided by Stake’s (2015) systematic phases of case summary (factual information), inductive case themes (issue relevant meanings), and case features (abstractions to the existing knowledge). The case was selected from a larger study examining the meaning and experience of elder family financial exploitation based on the following case boundaries: reliance on family members with minimal private sector support, no report to the authorities, and successful outcomes for the victim, perpetrator, and the family system.

The case family successfully resolved family-based financial exploitation by (a) honoring the victim’s wishes, (b) providing support and accountability for the perpetrator, (c) restoring family relationships and functioning, and (d) family-driven decision making. A family systems approach and the application of restorative justice principles are identified as overarching case features.

As a study of a previously undocumented experience of successful family involvement, the case findings are useful for researchers and practitioners when constructing and examining the effectiveness of future intervention strategies.

Knowledge and understanding of effective interventions and what works to resolve elder abuse of all types is a recognized gap ( Burnes, 2017 ; Burnes et al., 2020 ). Using a single case inquiry ( Stake, 2005 ), considered appropriate when presenting previously undocumented experiences, this article describes how and why one family achieved meaningful intervention processes and outcomes when faced with elder family financial exploitation (EFFE). A review of the literature reinforced that this article contributes the first descriptive case study of a family-defined successful intervention without the involvement of formal systems. We present a case description and several stages of interpretative analysis, providing a needed understanding of the interwoven nature of family-driven successful intervention and the specific family and EFFE contexts ( Stake, 2005 ).

One of the most prevalent types of elder abuse globally, EFFE takes place in the context of family relationships when a family member, often an adult child, illegally or improperly uses an older adult’s funds, property, or assets ( De Liema, 2018 ; Pillemer et al., 2016 ). The prevalence of EFFE is widespread, affecting approximately one in 15 older adults worldwide ( Yon et al., 2017 ). Evidence indicates family members are the most common perpetrators of financial exploitation, not strangers ( De Liema, 2018 ). The consequences of EFFE go beyond economic losses, with significant physical, psychological, and social health and well-being consequences for older victims, and ripple effects for millions of family members, communities, and societies ( Acierno et al., 2019 ).

Existing elder abuse literature has recognized the need to understand a broad range of intervention strategies, including various informal roles and involvement in addition to formal interventions ( Burnes, 2017 ; Burnes et al., 2020 ; Fraga Dominguez et al., 2019 ). A majority of elder abuse intervention strategies to date, including for EFFE, have focused on the role and effectiveness of formal systems (e.g., police, legal systems, adult protective services; Burnes, 2017 ). However, it is well recognized that a majority of victims and family members never interact with formal systems ( Acierno et al., 2020 ). Informal supports have been found to be useful and generally preferred over formal sources of help ( Fraga Dominguez et al., 2019 ).

Breckman et al. (2018) called attention to the critical and unique role and experience of concerned persons, defined as nonabusing family, friends, and neighbors involved in informally supporting elder abuse victims, 60% of whom chose to engage in a helping role. This and other studies of informal support find that concerned persons generally serve as an enabling resource for victims by taking on multiple helping tasks, referring, and linking victims to formal services ( Breckman et al., 2018 ; Burnes et al., 2016 ). Interventions involving victims and concerned family members (CFMs) have shown to be effective financial dispute interventions to avert full court proceedings, such as the Australian mediation-based intervention that prevented or stopped financial abuse for over half (59%) of victims and family members ( Bagshaw et al., 2015 ). This was the only family-focused intervention addressing financial abuse among studies of community-based interventions for elder abuse and neglect reviewed from 2009 to 2015 ( Fearing et al., 2017 ).

The knowledge generated from the above studies demonstrates the interdependent, reciprocal, and nested contexts of individual family members within a family social unit, and families being further imbedded within broader social and cultural systems of the environment, reflecting an ecological systems framework ( Bronfenbrenner, 1979 , 2005 ; Chan & Stum, 2020 ). The importance of applying such frameworks has been recognized when developing and delivering community elder mistreatment interventions ( Burnes, 2017 ). In theory, an ecological systems intervention would recognize the influence of multiple system levels when addressing elder abuse (e.g., victim, perpetrator, larger family systems). A scoping review revealed great disparities in the system levels being addressed in elder abuse interventions, finding a majority of outcomes focused on one system level, typically victims, some on perpetrators, and one on a family system ( Burnes et al., 2020 ). Informal family involvement is largely invisible and unrecognized as a critical piece of the interdependent, nested ecological systems intervention puzzle.

There are significant gaps in understanding success as a result of CFMs intervening on behalf of victims. This is due to several factors. First, there are varying elder abuse definitions, a focus on barriers to service use versus facilitators, and limited studies across elder abuse subtypes and social contexts ( Fraga Dominguez et al., 2019 ). When objective and validated measures of formal system intervention effectiveness have been documented (e.g., reducing/stopping abuse, accessed services, cases resolved), it remains unclear whether victims and family members’ perceptions of success would actually overlap ( Burnes et al., 2020 ; Fraga Dominguez et al., 2019 ). Westmarland and Kelly (2013) illustrated in the broader field of family violence a differentiated understanding of success, including partners’ relationship, empowerment, safety, coparticipation, awareness, and inclusion of children’s voices. This meaning of success extended beyond typical outcome measurements such as no additional calls to the authorities or no recurrence of physical abuse.

Second, the meaning of success can be highly subjective, influenced by the specific EFFE context, individual CFMs, formal and/or informal systems involvement, cultural norms, etc. For example, family contextual factors potentially influencing EFFE family involvement and the meaning of success can include power and control dynamics across generations, issues of mistrust imbedded in a long family history, cultural norms of financial privacy, pride, exchange, and entitlement to family resources, and unresolved relationship conflicts ( Betz-Hamilton & Vincenti, 2018 ; Wendt et al., 2015 ). Understanding the subjective meaning of success from the perspective of victims and other stakeholders in the family system (perpetrators, CFMs) is critical whether interventions are informal, formal, or a mix ( Burnes et al., 2020 ).

A handful of EFFE literature, of which all are descriptive case studies from the perspectives of family members, provides some insight into the meaning of family involvement and offers cues about the subjective meaning of success. Zannettino et al. (2015) described the experience of a concerned son choosing not to intervene to help the victim (his mother), disclose to anyone outside the family, or try to resolve the situation. The case illustrated that assumptions about success were ensconced in cultural and family norms of intergenerational responsibilities, keeping family matters private to avoid shame in the community, and preempting threats and consequences from the perpetrator toward the victim and two nonperpetrator siblings. Two additional cases described personal intervention experiences in the United States ( Beidler, 2012 ; Horry, 2014 ). Both cases rested on assumptions of success by extending intervention to include formal systems: highly engaged CFMs (granddaughter, niece) faced complex challenges, intensely advocated for the victims’ health and well-being, coped with consequences on personal well-being and family relationships, and shared failures of formal systems. In all three cases, the meaning of success varied depending on key helpers, type of help sought, and the extent of formal versus informal help.

Case Study Inquiry

We rely on Stake (2005) for our case study inquiry given the alignment of Stake’s approach with the attributes of social constructivism guiding the larger EFFE study ( Stum, 2014 ) from which the case is drawn. Stake’s case study approach focuses on understanding the complexities and meaning of interpersonal processes and outcomes within contexts. Following Stake’s approach, a single case study inquiry requires a clearly defined and bounded case as the unit of analysis. The “case” (pseudonym “Family K”) is delimited by the following boundaries: (a) the family relied on the involvement of family members with minimal private sector supportive services; (b) the case was not reported to any authorities; (c) the case included intervention processes and outcomes defined by the participating CFM as successful for the victim, perpetrator, and family system. Taken together, these attributes reflect successful family intervention outcomes previously undocumented in the literature, justifying the use of a single case inquiry ( Stake, 2005 ).

Participant Recruitment and Description

Following Institutional Review Board approval, the case study CFM (nonabuser, nonvictim) was recruited as part of a voluntary sample of 28 CFMs who self-identified as having experienced EFFE. A network of practitioners in a Midwestern statewide elder justice network (e.g., private attorneys, county workers, social workers) was utilized to recruit the CFM. The CFM retrospectively shared her family’s EFFE experience that had been occurring in the 3 years prior to the interview. Her account was taken at face value, without being able to substantiate that EFFE occurred, or take into account the views and perspectives of all involved family members. The CFM was the granddaughter-in-law of the victim, in her 40s, White, married, employed full-time, college-educated, and living in a Midwestern metropolitan area.

Data Collection

The CFM completed a semistructured in-depth interview lasting 80 min and a written survey. Interview questions focused on understanding the family composition, key stakeholder roles, and involvement in the EFFE experience (e.g., victim, perpetrator, CFM, family of origin). The CFM was asked to share her EFFE story, including how and why EFFE occurred, discovery processes, reactions, actions taken, intervention motivation and goals, systems involvement (formal elder abuse, other community resources), costs and consequences for the older adults, perpetrator, CFM, and family as a unit, ending with lessons learned. The interview was audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriber, and de-identified. The written survey gathered demographic descriptions of the CFM, victim, and perpetrator, as well as information on the victim’s decision-making plans (e.g., powers of attorney, will) and the quality of family relationships when growing up, as an adult before EFFE, and currently.

Case Analysis and Presentation

Case data analysis and interpretation were guided by Stake’s (2005) systematic and layered phases of case summary (factual information), inductive case themes (issue relevant meanings), and case features (abstractions to existing knowledge). To establish credibility and interrater agreement and reliability in all data analysis phases, both authors (T. R. Kilaberia and M. S. Stum) independently read and re-read data sources, made analytic memos regarding reactions to the data, discussed conflicting data interpretations, explored alternative views, and reached consensus ( Creswell, 2016 ; Stake, 2005 ).

A first analysis step involved constructing a narrative-based descriptive case summary with the purpose of reflecting the “facts” within the specific EFFE and family context. The case summary was developed by both authors reviewing and utilizing all Family K data sources. The CFM’s transcript was then used to inductively identify intervention process and outcome themes (issue-relevant meaning units) attributed as meaningful by the participant based on the family and EFFE context ( Table 1 ). The final phase of case analysis involved direct interpretation, connecting what was meaningful about successful intervention to the participant (the themes) to overarching and higher-order case features identified from the researchers’ frame of reference and grounded in the larger literature ( Table 1 ). The themes were examined as an integrated whole, looking for commonalities and overarching features. For example, the authors identified and discussed specific examples of the restorative justice ethos in each of the individual themes, comparing and contrasting with formal restorative justice principles and assumptions, leading to the identification of restorative justice as a case feature.

Inductive Development of Within-Case Themes and Features

Following Stake’s (2005) suggested presentation approach, we begin with the descriptive case summary, followed by within-case themes and verbatim quotes to illustrate. Discussion follows situating the thematic findings in the extant literature and introducing direct interpretation case features, connecting the features to existing concepts and theories.

Case Summary

The case involved a mother, Ollie, in her 80s, who was the victim, living in a Midwestern city of about 13,000 in population, designated as a Metro area; a daughter, Trina, in her 50s, who was the perpetrator; and 14 other family members from three generations who collectively participated in resolving the EFFE situation. Of nine siblings in total, two brothers and two sisters were highly involved; other siblings and in-laws were involved at a distance. The case as narrated by Sidney, the participating CFM, an in-law to Ollie, and a partner of Sam (one of Ollie’s nine adult children) follows. All names are pseudonyms.

After a third divorce, Trina (the perpetrator), in her 50s, moved in to live with Ollie (her mother and victim), 86 years of age. Ollie had worked as a medical professional well into her advanced age to secure enough savings for herself. Trina worked as a professional in the insurance industry. Trina had always been a major social connection between family members as she organized family events and kept everyone connected. She had also often provided support for her siblings when they needed it.

Part of the shared living arrangement was for Trina to have a place to stay and for Ollie to have a caregiver. Due to Ollie’s forgetfulness (no diagnosis of dementia), Trina had been entrusted by the family members to be the Financial Power of Attorney for Ollie even before Trina moved in to live with her. Trina had had a history of substance abuse, different jobs beginning in her 20s, and unethical job performance. Ollie had helped Trina in times of difficult life transitions, by having Trina’s children live with her temporarily, as needed.

The couple, Sidney (participating CFM) and Sam (Ollie’s adult child), noticed behavior changes in Trina over a period of time: Trina did not participate in a major family event, would not answer phone calls, and would not be available for childcare. Knowing Trina’s history of addiction, they asked Trina whether she was using alcohol or drugs again. Trina responded that she was not. The couple suspected that Trina was gambling, but they did not suspect that Trina “was stealing to gamble. We thought she was just using her own money.” Nine months later, Trina confessed to financially exploiting her mother Ollie. Trina had scheduled a surgery, had hoped to obtain enough pain medication as a result of the surgery to then kill herself with it when the couple would be on vacation.

Over the course of approximately a year and a half, Trina first lost to gambling her own money she had received as a result of divorce proceedings. Trina then lost an estimated $120,000 of Ollie’s money, depleting her bank accounts and taking out joint credit cards to be able to spend money.

Successful Intervention Themes

Four guiding themes were identified as contributing to successful intervention processes and outcomes: (a) honoring victim’s wishes and safety, (b) perpetrator support and accountability, (c) restoring family relationships and functioning, and (d) family-driven decision making.

Honoring Victim’s Wishes and Safety

Family K “took our cues” from Ollie and honored Ollie’s expressed wishes. Ollie had been very involved in the community throughout her life, did not want the EFFE experience widely known, and did not want any reports of the exploitation to be made to authorities. The family honored this expressed wish and kept the matter “very contained. […] everybody followed [Ollie’s] lead in terms of not notifying anybody and having a lot of respect for that.” Family members determined early on that adversarial or punitive accountability mechanisms that required “somebody going to jail” would be undesirable. They perceived it would be a greater stress for Ollie to cope with the intervention of authorities than it would be for the family to resolve the issue without outside intervention:

What was so complicated about this stuff is that if the police had come and intervened and if there’d been a big institutional sort of response to this, that would have aged her [Ollie] even more, because she would have been so ashamed if it would have been public […] she would have watched her daughter suffer these awful consequences. […] Here she is at the end of her life, she was watching her son die [due to an illness], and she didn’t want to lose another kid.

Over a period of 8 weeks after the discovery, Family K worked to establish safeguards. Trina actively participated in the process: checks and balances were put in place to monitor and “comply” with the family plan created with Trina’s input. Trina agreed to immediately move out of Ollie’s house and accepted the offer to move in with Sam (sister) and her family, staying for 8 weeks while she was recovering from her medical surgery. Sam and her family “were ready to figure out how to have [Trina] just live with us permanently. Because we thought it just would not be right for her to go back” [to live with Ollie]. Trina’s access to Ollie’s bank accounts and mail was stopped. Sam took over as Financial Power of Attorney for Ollie. Family K established a third party for Trina to help her manage her own finances.

Perpetrator Support and Accountability

Ollie’s second expressed wish was for Trina to get help and eventually reunite with her. Throughout the helping process, Family K kept the perspective that the exploitation was about “an addict’s calamity versus a criminal activity.” Holding this view, immediate and extended family members offered empathy and understanding to Trina. They listened when Trina relayed that it had been difficult being the sole caregiver to Ollie, that her caregiving had been unseen and unappreciated, and that she had relied on gambling as a way to cope.

Trina actively sought help for her addiction by attending Gamblers Anonymous (GA) and Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meetings. Family members regularly checked in with her to understand and support her recovery. Over time, in treatment, and in periodic conversations with family members, Trina understood that her pattern was that of someone who had relapsed. By considering her actions, changed or lost relationships, and rejections by some siblings, she experienced a renewed perspective. Family members thought that such an awakening was of far greater consequence for her than any she could have experienced as a result of formal systems involvement:

Through the addiction treatment, and also through the deep shame she experienced, and then the rejection by her brothers; all of that sort of together. And then she, you know … she did go through this spiritual transformation through it all […] There are definitely security measures in place. And her promise that it would never happen again, and her recovery through … you know, she went to treatment. She continues with going to GA on a weekly basis, she’s continuing to actively engage in her addiction program. And you know, those are the things that demonstrate to us that she is trustworthy. Even though it’s kind of … you know, she shattered it.

Trina was grateful for the opportunity to pay Ollie back, and did so, in full, over a period of 3years, to compensate for monies taken from Ollie: “She [Trina] is almost done paying her [Ollie] back, which is pretty amazing. Just in a couple of years, three years, she’s almost paid back all the money.”

Restoring Family Relationships and Functioning

As safeguards were put in place to prevent further victimization, and after Trina sought help, she reunited to live with and be a caregiver for Ollie. Over time, Ollie and Trina repaired their relationship and each benefited from the living and caregiving arrangement: “her [Ollie’s] relationship with her daughter [Trina] is still intact. And might be better now than it was before. And I am not saying because of what had happened, but because of the process that [Trina] had to go through.”

Other family members were able to maintain relationships with Trina and as a collective intergenerational family unit (e.g., siblings, in-laws, grandchildren). Although family relationships were reconsidered and were not what they used to be, Trina remained a part of the family’s future. Some family members who had, prior to the exploitation, considered Trina as a decision maker in cases of emergency or major family events no longer trusted her to be able to fulfill such roles in the future. Other family members viewed Trina’s proactive response and involvement as evidence to trust her again, especially given the safeguards put in place. Sidney (participant) attributed this outcome to the fact that Family K was able to both demand accountability and provide support.

Family-Driven Decision Making: “The Family Came Around and Protected Her”

Different family subsystems comprising Family K worked together to ensure that the intervening and supportive entity was the family itself. The victim, the perpetrator, and seven adult children from the family of origin and spouses/partners (in-laws) from in and out of town defined help-seeking, assumed responsibilities, and implemented accountability mechanisms. One brother advocated for the living arrangement between Ollie and Trina to be formalized as a caregiving arrangement. He also oversaw the process of “financial reparation” while another sibling monitored the progress. Specific family members were designated to oversee Trina’s “compliance” with the accountability plan developed by the family. Family decisions took into consideration family members’ strengths in overseeing entrusted parts of the overall plan and attending to their coping, given all were affected by the process. In this way, the family process itself reinforced a “restorative justice kind of approach”:

It was awful what she did. And there should be some accountability for that. But she also had a lot of accountability in the family too, because when people in the family found out she was shunned by her brothers. As [her brother, now deceased] was dying, he wouldn’t see [Trina] because he was so furious about what she had done. So, there were interfamilial consequences that [Trina] faced that I think were probably graver for her and had more meaning for her than going behind bars or whatever.

Family K insured at every step that they would take the reins to define the problem, determine solutions that best fit their shared values, and assume responsibility to carry out needed help-seeking steps. Reaching out to mutual aid community supports demonstrates the awareness of the family to utilize external resources that are empowering, nonbureaucratic, and nonadversarial (e.g., GA and AA support and money manager for Trina, lawyer for Financial Power of Attorney change). Such help-seeking reflects the family’s assumptions and values about what external help meant to them and at what cost they wanted it. Family K feared that the disclosure of exploitation by Trina at GA meetings would prompt the counselor to report, which would initiate formal systems involvement deemed undesirable by the family from the beginning. The family was relieved that no reporting had occurred.

Family K operated with no expectation of involving authorities, in part because of Ollie’s expressed wishes, and in part because of the belief that involving authorities may be merited for some, but clearly not for their family’s situation.

Ultimately […], my, sort of, philosophical understanding of this kind of abuse, where the victim cannot protect herself …. But, the family came around and protected her, and didn’t maybe need the state, to kind of intervene. Because I think she’s protected at this point. Now she is protected in ways that she wasn’t before, because of what had happened. […] I know these things are really complicated and yet I think she experienced justice. […] I think it’s really important to treat these cases very, very cautiously and carefully.

The case study shows how one family’s EFFE experience and intervention broadens the meaning of “intervention” and “success.” By choosing to get involved and take the decision-making reins, Family K constructed meaningful responses to honor the victim’s wishes, provide support and accountability for the perpetrator, and restore family relationships and functioning. In so doing, Family K determined what success would mean for all involved and subsequently accomplished the goal of resolving EFFE. For Family K, success meant remaining a family while at the same time enacting conciliation between the victim–perpetrator dyad and the larger family system.

Varying perceptions of problems and solutions among family members influence if and how decisions are made about EFFE intervention ( Wendt et al., 2015 ). This in turn influences how families may construct the meaning of success. Family K’s ability to come together and seek shared understanding and input iteratively throughout the process enabled tailoring of support by the family in such a way that accounted for the needs of the victim–perpetrator dyad as well as the larger family system. Family K’s intervention processes capitalized on the strengths within the family system, including close interpersonal relationships, a family history of cohesion, communication, and transparency, and shared filial responsibility norms and expectations. Family K demonstrated that a shared understanding and participation likely accelerated EFFE response in a way that allowed Family K to construct what a successful outcome would mean for their individual and collective relationships, investment, and values.

Respecting a victim’s right to self-determination and safety for the victim are expectations guiding elder abuse community-based protective service systems ( Burnes, 2017 ; Fraga Dominguez et al., 2019 ). However, whether informal interventions do the same is a matter of choice. In Family K’s case, the victim had the capacity to communicate her preferences and wishes, understood the consequences of choices and decisions, was actively engaged in the intervention processes, and was honored by her family in her firm request to handle the matter within the family. In similar cases, developing a range of safeguards, driven by a goal of improving quality of life and financial security outcomes for the victim may be useful facets of an intervention.

Previously, Breckman (2018) showed concerned persons’ willingness to intervene when becoming aware of elder abuse, and an overall lack of support and services for families. This case study illustrates a family-organized process and outcomes attained by a family on its own, with minimal community supports. Family K’s involvement is consistent with the preferences of some elder abuse victims for informal over formal sources of help ( Fraga Dominguez et al., 2019 ). The case reflects that CFMs can be optimally positioned to be EFFE responders, in part because they are not distanced or objective, have access to and knowledge of the victims and perpetrators, and the unique family history and dynamics.

Case Features

Viewing the four case themes in the direct interpretation phase of our analysis, two overarching case features of the family’s successful intervention experience became apparent. For Family K, meaningful intervention processes and outcomes involved taking a family systems approach, as well as a complementary focus on restorative justice principles.

A Family Systems Approach

The case featured a contextually grounded family systems approach to EFFE involvement and intervention. Family K approached EFFE as a stressor event happening to all involved in the multigenerational family system, including the primary victim, perpetrator, and extended family members, whether emotionally or geographically close or distant. Consistent with family systems theory ( Whitchurch & Constantine, 2009 ), the processes and outcomes involved benefited individual family members as well as the collective family system. Family K recognized the interdependent and reciprocal nature of individuals within the family system, identifying important outcomes not only for the victim, but also for the perpetrator and family members. Family K prioritized protecting multiple types of lifelong family relationships in a relatively large family of origin (perpetrator/victim, siblings, parent/adult child, in-law relatives, and across multiple generations). The family’s approach to addressing EFFE recognized that a change in one part of the family system affects the rest of the family social system. As the participating CFM described, helping the perpetrator was closely tied to helping the victim’s overall health and well-being and also helped to keep family relationships and functioning intact.

Family K’s ability to resolve the EFFE situation underscores the importance and impact of addressing EFFE as a contextual family system issue. Burnes (2017) recommended testing the hypothesis that multisystemic interventions incorporating victims, perpetrators, and relevant family members would lead to better outcomes than interventions focused solely on the victim. This case study offers support for the validity of such a hypothesis, suggesting potential family and EFFE contextual factors that may influence intervention outcomes. Family systems theory is an appropriate lens to apply as it is grounded in systems thinking, providing insight into how family members mutually influence and interact with one another ( Whitchurch & Constantine, 2009 ). Researchers and practitioners are encouraged to develop and test approaches informed by family systems theory and broader ecological systems theory ( Bronfenbrenner, 1979 , 2005 ) as a means of improving EFFE interventions.

Restorative Justice Approach

The experience of Family K lends support toward applying principles of restorative justice in resolving EFFE cases. Family K’s intervention actions and the CFM’s words emphasized the importance of “enabling justice” by drawing on principles such as accountability, reparation, and empowerment through support. Restorative justice is a process of administering justice that can be used outside of or in tandem with traditional justice-seeking processes, achieving desired outcomes with smaller costs ( Zehr, 2015 ).

Family K’s focus on restoring justice within the family system reflects three core restorative justice principles: (a) engagement of key stakeholders in determining just processes, (b) accountability of perpetrator and family members to each other, and (c) and restoration of harm that was done ( Zehr, 2015 ). Intentional efforts were made to engage the perpetrator/victim dyad and extended family members in deciding and carrying out EFFE intervention steps. The perpetrator was held accountable by the family, took responsibility for the exploitation, paid back the victim for lost funds, and addressed her underlying addiction issues with support from the family system. Accountability to each other in the family system was also expected as new roles and responsibilities were navigated. Restoration processes went beyond financial reparation and focused on repairing damaged family functioning and relationship ethics in terms of safety for the victim, checks and balances, trust, honesty, and respect between the perpetrator–victim dyad, among siblings, and in-law family members. The family’s approach to just processes allowed family members to engage with betrayal, grief, and loss on their own terms, to voice their regrets and wishes, regain equilibrium, and restore and repair ethical dimensions of family relationships.

Although federal and state judicial systems in the United States support restorative justice, implementation has been slow, in part due to the lack of funding, and the practice has been incremental and in specific geographies rather than nationwide ( Karp & Frank, 2016 ). There is, however, increasing evidence of the benefits of restorative justice. Van Camp and Wemmers (2013) found in a study of victims of violent crimes that practicing restorative justice had flexibility, care, dialogue, and prosocial motivation, benefits over and above those resulting from the quality of the experience of a fair process. Australia’s proven family mediation intervention model addresses EFFE specifically and serves as an example guided by similar restorative justice principles ( Bagshaw et al., 2015 ). Future studies may examine shared ethical values, negotiating what being “just” means, and opportunities for agreement of the victim, perpetrator, and extended family members to be engaged and accountable to each other. Researchers and practitioners are especially encouraged to account for how restorative justice, specifically the construction of just processes and outcomes, may result in experiences of success across varied family and EFFE contexts.

Based on the literature informing this case study, this article contributes the first descriptive case inquiry of a successful family EFFE intervention without the involvement of formal elder abuse systems. Informal family support and involvement are largely invisible and unrecognized as a critical factor in EFFE intervention. This single case study contributes a rich understanding of the meaning and experience of successful informal family intervention and resolution in a specific family context and EFFE situation. Victim self-determination, perpetrator support and accountability, protecting family relationships, and family-driven decision making were interwoven case themes. Meaningful intervention involved a family systems approach in which primarily victim-defined goals and then family-supported resolution were attained through a complementary process of restorative justice.

Informal intervention, and the themes and features identified in this case, should not be viewed as a “one size fits all” given the heterogeneity of family systems and EFFE contexts. EFFE may involve victims who may not have the same cognitive capacity and physical wellness and in families that may not have the same values, cohesion, and family functioning context. Not all victims have adult children or extended family available, willing, or able to get involved. Not all families may want the responsibility of determining intervention processes and outcomes. Not all families may be able to articulate and agree on the meaning of just outcomes or success. We note that in Family K, the victim, perpetrator, and CFM were all female, and suspect female gender may influence intervention roles and involvement. As Fraga Dominguez et al. (2019) found, among concerned persons, adult daughters were the most common callers seeking help from elder abuse victim service helplines. Female gender may thus be linked with prosocial motivation. However, gender alignment between perpetrator, victim, and key stakeholders may not occur in every case. Future studies may show that EFFE situations that involve multiple perpetrators and/or victims, or a family with a history of conflicts, unhealthy power and control dynamics, or differences in gender may benefit from a broader range of formal and informal interventions.

The prevalence and potential consequences of EFFE underscore the need for effective interventions. The lessons learned from Family K’s experience reinforced the importance of being able to construct interventions that best fit the realities of the individuals and contexts involved. That is, the meaning of EFFE and the degree of success in intervention cannot be separated from the specific family and EFFE context.

Not all cases may fit well into either restorative justice or family systems models. Tailoring interventions would be especially important in cases where cultural meanings of abuse, exploitation, filial responsibility, resource-sharing, and accessible systems and resources may differ vastly from normative assumptions in mainstream definitions and policy contexts. Evidence of successful interventions meaningful to victims, perpetrators, and CFMs is needed to inform and guide future EFFE interventions.

The authors thank Dr. Barbara Bowers, editor, and the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback.

This study is supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Experiment Station, Project 1013288.

IRB protocol/human participants’ approval number: 1610SS96987.

None declared.

Acierno , R. , Steedley , M. , Hernandez-Tejada , M. A. , Frook , G. , Watkins , J. , & Muzzy , W . ( 2020 ). Relevance of perpetrator identity to reporting elder financial and emotional mistreatment . Journal of Applied Gerontology , 39 ( 2 ), 221 – 225 . doi: 10.1177/0733464818771208

Google Scholar

Acierno , R. , Watkins , J. , Hernandez-Tejada , M. A. , Muzzy , W. , Frook , G. , Steedley , M. , & Anetzberger , G . ( 2019 ). Mental health correlates of financial mistreatment in the National Elder Mistreatment Study Wave II . Journal of Aging and Health , 31 ( 7 ), 1196 – 1211 . doi: 10.1177/0898264318767037

Bagshaw , D. , Adams , V. , Zannettino , L. , & Wendt , S . ( 2015 ). Elder mediation and the financial abuse of older people by a family member . Conflict Resolution Quarterly , 32 ( 4 ), 443 – 480 . doi: 10.1002/crq.21117

Beidler , J. J . ( 2012 ). We are family: When elder abuse, neglect, and financial exploitation hit home . Generations , 36 ( 3 ), 21 – 25 .

Betz-Hamilton , A. E. , & Vincenti , V. B . ( 2018 ). Risk factors within families associated with elder financial exploitation by relatives with powers of attorney . Journal of Family & Consumer Sciences , 110 ( 1 ), 19 – 27 . doi: 10.14307/JFCS110.1.19

Breckman , R. , Burnes , D. , Ross , S. , Marshall , P. C. , Suitor , J. J. , Lachs , M. S. , & Pillemer , K . ( 2018 ). When helping hurts: Nonabusing family, friends, and neighbors in the lives of elder mistreatment victims . The Gerontologist , 58 ( 4 ), 719 – 723 . doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw257

Bronfenbrenner , U . ( 1979 ). The ecology of human development . Harvard University Press .

Google Preview

Bronfenbrenner , U . ( 2005 ). The bioecological theory of human development. In U. Bronfenbrenner (Ed.), Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development (pp. 3 – 15 ). Sage .

Burnes , D . ( 2017 ). Community elder mistreatment intervention with capable older adults: Toward a conceptual practice model . The Gerontologist , 57 ( 3 ), 409 – 416 . doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv692

Burnes , D. , MacNeil , A. , Nowaczynski , A. , Sheppard , C. , Trevors , L. , Lenton , E. , Lachs , M. S. , & Pillemer , K . ( 2020 ). A scoping review of outcomes in elder abuse intervention research: The current landscape and where to go next . Aggression and Violent Behavior , 57 , 1 – 8 . doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2020.101476

Burnes , D. , Rizzo , V. M. , Gorroochurn , P. , Pollack , M. H. , & Lachs , M. S . ( 2016 ). Understanding service utilization in cases of elder abuse to inform best practices . Journal of Applied Gerontology , 35 ( 10 ), 1036 – 1057 . doi: 10.1177/0733464814563609

Chan , A. C. , & Stum , M. S . ( 2020 ). The state of theory in elder family financial exploitation: A systematic review . Journal of Family Theory & Review , 12 ( 4 ), 492 – 509 . doi: 10.1111/jftr.12396

Creswell , J. W. , & Poth , C. N . ( 2016 ). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches . Sage Publications .

De Liema , M . ( 2018 ). Elder fraud and financial exploitation: Application of routine activity theory . The Gerontologist , 58 ( 4 ), 706 – 718 . doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw258

Fearing , G. , Sheppard , C. L. , McDonald , L. , Beaulieu , M. , & Hitzig , S. L . ( 2017 ). A systematic review on community-based interventions for elder abuse and neglect . Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect , 29 ( 2–3 ), 102 – 133 . doi: 10.1080/08946566.2017.1308286

Fraga Dominguez , S. , Storey , J. E. , & Glorney , E . ( 2019 ). Help-seeking behavior in victims of elder abuse: A systematic review . Trauma, Violence & Abuse , 22 ( 3 ), 466 – 480 . doi: 10.1177/1524838019860616

Horry , K . ( 2014 ). Voices from the front lines: Reflections from a family member. New York City Elder Abuse Center eNewsletter . https://nyceac.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/Ill_Stand_by_-You.pdf

Karp , D. R. , & Frank , O . ( 2016 ). Anxiously awaiting the future of restorative justice in the United States . Victims & Offenders , 11 ( 1 ), 50 – 70 .doi: 10.108015564886.2015.1107796

Pillemer , K. , Burnes , D. , Riffin , C. , & Lachs , M. S . ( 2016 ). Elder abuse: Global situation, risk factors, and prevention strategies . The Gerontologist , 56 ( Suppl. 2 ), S194 – S205 .doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw004

Stake , R. E . ( 2005 ). Qualitative case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (p. 443 – 466 ). Sage .

Stum , M . ( 2014 ). Examining elder family financial exploitation to inform prevention education . United States Department of Agriculture Research, Education & Economics Information System . https://portal.nifa.usda.gov/web/crisprojectpages/1013288-examining-elder-family-financial-exploitation-to-inform-prevention-education.html

Van Camp , T. , & Wemmers , J. A . ( 2013 ). Victim satisfaction with restorative justice: More than simply procedural justice . International Review of Victimology , 19 ( 2 ), 117 – 143 . doi: 10.1177/0269758012472764

Wendt , S. , Bagshaw , D. , Zannettino , L. , & Adams , V . ( 2015 ). Financial abuse of older people: A case study . International Social Work , 58 ( 2 ), 287 – 296 .doi: 10.1177/0020872813477882

Westmarland , N. , & Kelly , L . ( 2013 ). Why extending measurements of “success” in domestic violence perpetrator programmes matters for social work . British Journal of Social Work , 43 ( 6 ), 1092 – 1110 . doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcs049

Whitchurch G. G. , & Constantine L. L . ( 2009 ) Systems theory. In P. Boss , W. J. Doherty , R. LaRossa , W. R. Schumm , & S. K. Steinmetz (Eds.), Sourcebook of family theories and methods . Springer . doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-85764-0_14

Yon , Y. , Mikton , C. R. , Gassoumis , Z. D. , & Wilber , K. H . ( 2017 ). Elder abuse prevalence in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis . The Lancet. Global Health , 5 ( 2 ), e147 – e156 . doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30006-2

Zannettino , L. , Bagshaw , D. , Wendt , S. , & Adams , V . ( 2015 ). The role of emotional vulnerability and abuse in the financial exploitation of older people from culturally and linguistically diverse communities in Australia . Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect , 27 ( 1 ), 74 – 89 . doi: 10.1080/08946566.2014.976895

Zehr , H . ( 2015 ). The little book of restorative justice: Revised . Simon & Schuster .

- decision making

- family relationship

- accountability

- financial abuse

- perpetrator of child and adult abuse

Email alerts

Citing articles via, looking for your next opportunity.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1758-5341

- Copyright © 2024 The Gerontological Society of America

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Brought to you by:

Smith Family Financial Plan (A)

By: Brian Lane, Johnstone Nathalie

The Smith family is in a cash crunch. Even with a combined gross family income of $80,000 per year, monthly cash outflows are still greater than inflows. Joel and Amber Smith are aware of these cash…

- Length: 6 page(s)

- Publication Date: Jul 17, 2013

- Discipline: Finance

- Product #: W13292-PDF-ENG

What's included:

- Teaching Note

- Educator Copy

$4.95 per student

degree granting course

$8.95 per student

non-degree granting course

Get access to this material, plus much more with a free Educator Account:

- Access to world-famous HBS cases

- Up to 60% off materials for your students

- Resources for teaching online

- Tips and reviews from other Educators

Already registered? Sign in

- Student Registration

- Non-Academic Registration

- Included Materials

The Smith family is in a cash crunch. Even with a combined gross family income of $80,000 per year, monthly cash outflows are still greater than inflows. Joel and Amber Smith are aware of these cash flow problems, but do not understand where their money goes and struggle to set financial goals. They have contacted a financial advisory firm to help them develop a plan and set realistic future goals. The Smiths face financial problems common to young families such as saving for their retirement and children's education, paying down credit card debt, paying down (and possibly refinancing) their mortgage, buying a new vehicle, and providing adequate healthcare insurance. Students are tasked with playing the role of the family's financial advisor and helping them bring their finances under control. The case is built in two parts, (A) and (B). These can be used in separate 75- to 90-minute classes, with Smith Family Financial Plan (A) covered at the midpoint of the course and Smith Family Financial Plan (B), product 9B13N006, covered near the end. Alternatively, it can be used as a two-part major assignment, with Part (A) as the first major submission and Part (B) as the second.

Authors Brian Lane and Nathalie Johnstone are affiliated with University of Saskatchewan.

Learning Objectives

This case series engages students in evaluating financial-planning alternatives and considering the effects of their recommendations on client goals. It places students in the role of a financial advisor and introduces them to the personal financial-planning process, with emphasis on personal financial statements and liquidity issues, insurance, investments, taxation, and retirement planning. This case was designed to complement the curriculum of an upper year undergraduate personal finance class and simulates the professional financial-planning environment of meeting with clients and developing financial plans. This case asks students to:Assess short-term and long-term financial goals while considering the time value of money.Create personal financial statements.Identify liquidity issues (banking, money management and personal credit).Assist clients in personal tax planning.Discuss the most effective way to finance large purchases to best meet client goals (personal loans and houses).

Jul 17, 2013 (Revised: May 24, 2013)

Discipline:

Geographies:

Industries:

Financial service sector

Ivey Publishing

W13292-PDF-ENG

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

- People Directory

- Safety at UD

Talking with Your Family about Financial Difficulties

- Families and Relationships

- Financial Health

- Health Insurance 4 U

- Mental Well-Being

- Physical Activity

- Community Health Volunteers

- Request a Program

- Mindfulness

- Food Safety

- Mental Wellness & Prevention (ROTA)

- Got Your Back

- Animal Science

- Beginning Farmer Program

- Lima Bean Breeding Program

- Production Recommendations

- Variety Trial Results

- Small Grains

- Pest and Disease Database

- Sustainable Landscapes

- Irrigated Corn Research Project

- Soybean Irrigation Response Study

- Irrigated Lima Bean Yield & Quality

- Subsurface Drip Irrigation

- Irrigation Research Projects and Studies

- Moths and Snap Pea Processing

- Silk Stage Sweet Corn - Action Thresholds

- IPM Hot Topics

- Alfalfa Pest Management

- Field Corn: Pest Management

- Small Grains: Pest Management

- Soybeans: Pest Management

- Commercial Field Crop Disease Management

- Commercial Fruit & Vegetable Crop Pest Management

- EIPM Implementation Projects

- Pollinators

- Research and Extension Demonstration Results

- Brown Marmorated Stink Bug (BMSB) Management, Research, and Resources

- Certified Crop Advisor Program

- Publications

- Applicators and Educators

- UD Plant Diagnostic Clinic

- Weed Science

- Disease Management

- Variety Trials

- Crop Production

- Registration Help

- Delaware 4-H Staff Directory

- New Castle County 4-H

- Kent County 4-H

- Sussex County 4-H

- Delaware 4-H Foundation

- Shooting Sports

- Civil Engagement and Leadership

- Volunteering

- Club Management

- 4-H Afterschool

- Delaware Military 4-H

- Citizenship

- Statewide Drug Prevention & Lifeskills Program

- Resources for Teachers

- MyPI Delaware

- The STEAM Team!

- Leadership Opportunities

- 4-H by County

- Become a 4-H Volunteer

- Scholarships & Awards

- Delaware State Fair

- Farm Succession and Estate Planning

- Building Farm and Farm Family Resilience

- Legal Resources for the Delaware Agriculture Community

- Farm Vitality and Health Project

- Personal Financial Management Initiatives

- Climate Variability and Change

- General Information on what, how, why and where soil is tested

- Soil Testing Program Forms

- Nutrient Recommendations

- New to Delaware

- A Day in the Garden

- Grow Your Own Food

- Backyard Composting

- Become a Master Gardener

- Garden Workshops

- Gardener Helplines

- Garden Smart, Garden Easy

- Junior Gardener Program

- Kent County Scholarships

- Garden Advice Program

- Demonstration Gardens

- Master Naturalist Program

- Nutrient Management Certification

- Continuing Education for Nutrient Management

- Nutrient Management Planning Resources

- Commercial Nutrient Handler Resources

- Poultry Litter and Manure Management

- Turf Management

- Agriculture Notebook

- Horticulture Handbook

- Agriculture & Horticulture Handbooks

- Soil Fertility

- Delaware Climate Change Coordination Initiative (DECCCI)

- Salt Impacted Agricultural Lands

by Maria Pippidis, May 2020

A drop in income is a scary and unsettling situation for both adults and children. It is important to talk through the situation with family members as quickly as possible–even though it may be hard to do. Adults can quickly feel overwhelmed by the added stress and sense of reduced financial security. It is important to remember that children sense the tension in the family and may feel less secure, but don't know what to do about it.

Parents may be less engaged with their children and more likely to become upset or angry over little things, due to higher levels of stress. Keeping the lines of communication open during times like these can help everyone feel more connected. Family communication can also help older children and parents find ways to manage the family finances. Even young children can be taught about wants and needs and how family financial decisions are made.

You may wonder how you will afford to buy food and pay your rent or mortgage... -

Some tips for family money meetings:

- The most important thing to remember is to "leave the blame at the door."

- Recognize and respect each other's different attitudes toward money and approach discussions in an organized way. Work to find common ground so you can all work in the same direction.

- Make sure it is a good time for each of you to talk. If one of you has had a bad day or received difficult news, you may want to reschedule the discussion.

- Set ground rules for the discussion. Make sure you both have an opportunity to be heard and listen to what your partner is saying. Avoid accusations and blame.

- Set and prioritize your goals together and stick to the plan unless something significant occurs and you need to alter it.

- Set aside time each month for a money meeting. Regular meetings will become easier to do and keep you on track.

You may need to meet more frequently during times of financial stress. Try to set goals that are obtainable and leave everyone something that will keep their spirits up. When planning about cutting back on spending, find alternatives for when you have to say, "We can't do that anymore." For example, if you can't afford to go to the movie theater or need to cancel some online viewing subscriptions, then plan to go to the library and borrow them or start a movie-lending group with friends. Finding free and inexpensive alternatives can keep family members from feeling the brunt of financial hardship.

Some financial decisions are harder to make. For example, you may wonder how you will afford to buy food and pay your rent or mortgage. What will happen if you can't pay your credit card bills right now?

You need to take action right away if you are asking these questions. Find out about any available financial supports. You can help keep your family healthy and happy by finding supports like energy assistance, health insurance, and other resources.

If you are worried about overwhelming debt, or unable to make mortgage payments, call your lenders to work on a payment plan before you get behind on payments. Be realistic about what you can afford. This means that you have done the math and know that you can meet your basic needs while doing the best you can to meet your creditors' financial obligations. Meeting with a reputable financial counselor might be helpful.

See www.debtadvice.org for National Foundation for Credit Counseling-accredited agencies. In Delaware, the $tand By Me program offers financial coaching services.

College of Agriculture & Natural Resources

Cooperative Extension

- Health & Well-being

- Sustainable Production Systems

- 4-H, Personal & Economic Development

- Environmental Stewardship

Additional Links

- Faculty & Staff Resources

531 South College Avenue Newark, DE 19716 (302) 831-2501

Job Loss and Unemployment Stress

Dealing with uncertainty, elder scams and senior fraud abuse, stress relief guide, social support for stress relief, 12 ways to reduce stress with music, surviving tough times by building resilience.

- Stress Management: How to Reduce and Relieve Stress

- Online Therapy: Is it Right for You?

- Mental Health

- Health & Wellness

- Children & Family

- Relationships

Are you or someone you know in crisis?

- Bipolar Disorder

- Eating Disorders

- Grief & Loss

- Personality Disorders

- PTSD & Trauma

- Schizophrenia

- Therapy & Medication

- Exercise & Fitness

- Healthy Eating

- Well-being & Happiness

- Weight Loss

- Work & Career

- Illness & Disability

- Heart Health

- Childhood Issues

- Learning Disabilities

- Family Caregiving

- Teen Issues

- Communication

- Emotional Intelligence

- Love & Friendship

- Domestic Abuse

- Healthy Aging

- Aging Issues

- Alzheimer’s Disease & Dementia

- Senior Housing

- End of Life

- Meet Our Team

Understanding financial stress

Effects of financial stress on your health, tip 1: talk to someone, tip 2: take inventory of your finances, tip 3: make a plan—and stick to it, tip 4: create a monthly budget, tip 5: manage your overall stress, coping with financial stress.

Feeling overwhelmed by money worries? Whatever your circumstances, there are ways to get through these tough economic times, ease stress and anxiety, and regain control of your finances.

If you’re worried about money, you’re not alone. Many of us, from all over the world and from all walks of life, are having to deal with financial stress and uncertainty at this difficult time. Whether your problems stem from a loss of work, escalating debt, unexpected expenses, or a combination of factors, financial worry is one of the most common stressors in modern life. Even before the global coronavirus pandemic and resulting economic fallout, an American Psychological Association (APA) study found that 72% of Americans feel stressed about money at least some of the time. The recent economic difficulties mean that even more of us are now facing financial struggles and hardship.

Like any source of overwhelming stress, financial problems can take a huge toll on your mental and physical health, your relationships, and your overall quality of life. Feeling beaten down by money worries can adversely impact your sleep, self-esteem, and energy levels. It can leave you feeling angry, ashamed, or fearful, fuel tension and arguments with those closest to you, exacerbate pain and mood swings, and even increase your risk of depression and anxiety. You may resort to unhealthy coping mechanisms, such as drinking, abusing drugs, or gambling to try to escape your worries. In the worst circumstances, financial stress can even prompt suicidal thoughts or actions. But no matter how hopeless your situation seems, there is help available. By tackling your money problems head on, you can find a way through the financial quagmire, ease your stress levels, and regain control of your finances—and your life.

While we all know deep down there are many more important things in life than money, when you’re struggling financially fear and stress can take over your world. It can damage your self-esteem, make you feel flawed, and fill you with a sense of despair. When financial stress becomes overwhelming, your mind, body, and social life can pay a heavy price.

[Read: Stress Symptoms, Signs, and Causes]

Financial stress can lead to:

Insomnia or other sleep difficulties. Nothing will keep you tossing and turning at night more than worrying about unpaid bills or a loss of income.

Weight gain (or loss). Stress can disrupt your appetite, causing you to anxiously overeat or skip meals to save money.

Depression. Living under the cloud of money problems can leave anyone feeling down, hopeless, and struggling to concentrate or make decisions. According to a study at the University of Nottingham in the UK, people who struggle with debt are more than twice as likely to suffer from depression .

Anxiety. Money can be a safety net; without it, you may feel vulnerable and anxious. And all the worrying about unpaid bills or loss of income can trigger anxiety symptoms such as a pounding heartbeat, sweating, shaking, or even panic attacks.

Relationship difficulties. Money is often cited as the most common issue couples argue about. Left unchecked, financial stress can make you angry and irritable, cause a loss of interest in sex, and wear away at the foundations of even the strongest relationships .

Social withdrawal. Financial worries can clip your wings and cause you to withdraw from friends, curtail your social life, and retreat into your shell—which will only make your stress worse.

Physical ailments such as headaches, gastrointestinal problems, diabetes, high blood pressure , and heart disease. In countries without free healthcare, money worries may also cause you to delay or skip seeing a doctor for fear of incurring additional expenses.

Unhealthy coping methods , such as drinking too much , abusing prescription or illegal drugs, gambling, or overeating. Money worries can even lead to self-harm or thoughts of suicide.

If you are feeling suicidal…

Your money problems may seem overwhelming and permanent right now. But with time, things will get better and your outlook will change, especially if you get help. There are many people who want to support you during this difficult time, so please reach out!

Read Are You Feeling Suicidal? , call 1-800-273-TALK in the U.S., or find a helpline in your country at IASP or Suicide.org .

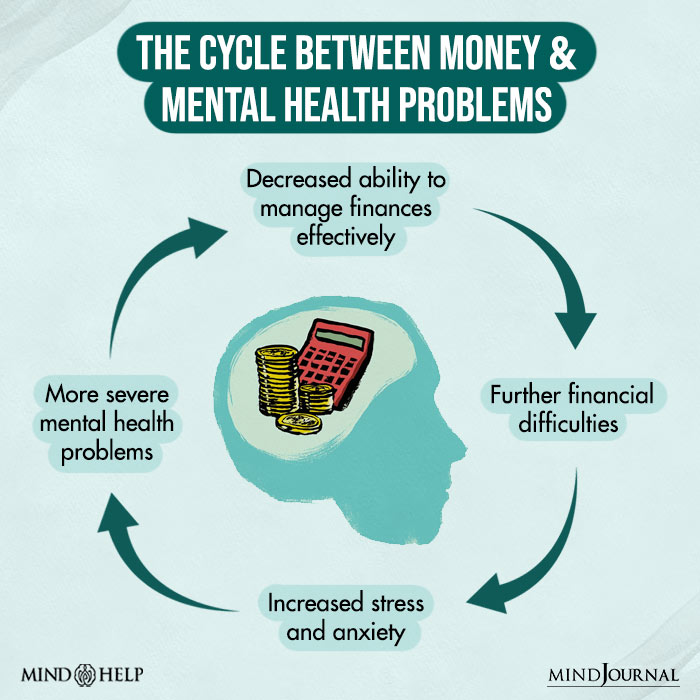

The vicious cycle of poor financial health and poor mental health

A number of studies have demonstrated a cyclical link between financial worries and mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, and substance abuse.

Financial problems adversely impact your mental health. The stress of debt or other financial issues leaves you feeling depressed or anxious.

The decline in your mental health makes it harder to manage money. You may find it harder to concentrate or lack the energy to tackle a mounting pile of bills. Or you may lose income by taking time off work due to anxiety or depression.

These difficulties managing money lead to more financial problems and worsening mental health problems, and so on. You become trapped in a downward spiral of increasing money problems and declining mental health.

No matter how bleak your situation may seem at the moment, there is a way out. These strategies can help you to break the cycle, ease the stress of money problems, and find stability again.

When you’re facing money problems, there’s often a strong temptation to bottle everything up and try to go it alone. Many of us even consider money a taboo subject, one not to be discussed with others. You may feel awkward about disclosing the amount you earn or spend, feel shame about any financial mistakes you’ve made, or embarrassed about not being able to provide for your family. But bottling things up will only make your financial stress worse. In the current economy, where many people are struggling through no fault of their own, you’ll likely find others are far more understanding of your problems.

[Read: Social Support for Stress Relief]

Not only is talking face-to-face with a trusted friend or loved one a proven means of stress relief, but speaking openly about your financial problems can also help you put things in perspective. Keeping money worries to yourself only amplifies them until they seem insurmountable. The simple act of expressing your problems to someone you trust can make them seem far less intimidating.

- The person you talk to doesn’t have to be able to fix your problems or offer financial help.

- To ease your burden, they just need to be willing to talk things out without judging or criticizing.

- Be honest about what you’re going through and the emotions you’re experiencing.

- Talking over your worries can help you make sense of what you’re facing and your friend or loved one may even be able to come up with solutions that you hadn’t thought of alone.

Getting professional advice

Depending on where you live, there are a number of organizations that offer free counseling on dealing with financial problems, whether it’s managing debt, creating and sticking to a budget, finding work, communicating with creditors, or claiming benefits or financial assistance. (See the “Get more help” section below for links).

Whether or not you have a friend or loved one to talk to for emotional support, getting practical advice from an expert is always a good idea. Reaching out is not a sign of weakness and it doesn’t mean that you’ve somehow failed as a provider, parent, or spouse. It just means that you’re wise enough to recognize your financial situation is causing you stress and needs addressing.

Speak to a Licensed Therapist

BetterHelp is an online therapy service that matches you to licensed, accredited therapists who can help with depression, anxiety, relationships, and more. Take the assessment and get matched with a therapist in as little as 48 hours.

Opening up to your family

Financial problems tend to impact the whole family and enlisting your loved ones’ support can be crucial in turning things around. Even if you take pride in being self-sufficient, keep your family up to date on your financial situation and how they can help you save money.

Let them express their concerns. Your loved ones are probably worried—about both you and the financial stability of your family unit. Listen to their concerns and allow them to offer suggestions on how to resolve the financial problems you’re facing.

Make time for (inexpensive) family fun. Set aside regular time where you can enjoy each other’s company, let off steam, and forget about your financial worries. Walking in the park, playing games, or exercising together doesn’t have to cost money but it can help ease stress and keep the whole family positive.

If you’re struggling to make ends meet, you may think you can ease your stress by leaving bills unopened, avoiding phone calls from creditors, or ignoring bank and credit card statements. But denying the reality of your situation will only make things worse in the long run. The first step to devising a plan to solve your money problems is to detail your income, debt, and spending over the course of at least one month.

A number of websites and smartphone apps can help you keep track of your finances moving forward or you can work backwards by gathering receipts and examining bank and credit card statements. Obviously, some money difficulties are easier to solve than others, but by taking inventory of your finances you’ll have a much clearer idea of where you stand. And as daunting or painful as the process may seem, tracking your finances in detail can also help you start to regain a much-needed sense of control over your situation.

Include every source of income. In addition to any salary, include bonuses, benefits, alimony, child support, or any interest you receive.

Keep track of ALL your spending. When you’re faced with a pile of past-due bills and mounting debt, buying a coffee on the way to work may seem like an irrelevant expense. But seemingly small expenses can mount up over time, so keep track of everything. Understanding exactly how you spend your money is key to budgeting and devising a plan to address your financial problems.

List your debts. Include past-due bills, late fees, and list minimum payments due as well as any money you owe to family or friends.

Identify spending patterns and triggers. Does boredom or a stressful day at work cause you to head to the mall or start online shopping? When the kids are acting out, do you keep them quiet with expensive restaurant or takeout meals, rather than cooking at home ? Once you’re aware of your triggers you can find healthier ways of coping with them than resorting to “retail therapy”.

Look to make small changes. Spending money on things like a morning newspaper, lunchtime sandwich, or break-time cigarettes can add up to a significant monthly outlay. While it may be unreasonable to deny yourself every small pleasure, cutting down on nonessential spending and finding small ways to reduce your daily expenditure can really help to free up extra cash to pay off bills.

Eliminate impulse spending. Ever seen something online or in a shop window that you just had to buy? Impulsive buying can wreck your budget and max out your credit cards. To break the habit, try making a rule that you’ll wait a week before making any new purchase.

Go easy on yourself. As you review your debt and spending habits, remember that anyone can get into financial difficulties, especially at times like this . Don’t use this as an excuse to punish yourself for any perceived financial mistakes. Give yourself a break and focus on the aspects you can control as you look to move forward.

When your financial problems go beyond money

Sometimes, the causes for your financial difficulties may lie elsewhere. For example, money troubles can stem from problem gambling , fraud abuse , or a mental health issue, such as overspending during a bipolar manic episode .

To prevent the same financial problems recurring, it’s imperative you address both the underlying issue and the money troubles it’s created in your life.

Just as financial stress can be caused by a wide range of different money problems, so there are an equally wide range of possible solutions. The plan to address your specific problem could be to live within a tighter budget, lower the interest rate on your credit card debt, curb your online spending, seek government benefits, declare bankruptcy, or to find a new job or additional source of income.

If you’ve taken inventory of your financial situation, eliminated discretionary and impulse spending, and your outgoings still exceed your income, there are essentially three choices open to you: increase your income, lower your spending, or both. How you go about achieving any of those goals will require making a plan and following through on it.

- Identify your financial problem. Having taken inventory, you should be able to clearly identify the financial problem you’re facing. It may be that you have too much credit card debt, not enough income, or you overspend on unnecessary purchases when you feel stressed or anxious. Or perhaps, it’s a combination of problems. Make a separate plan for each one.

- Devise a solution. Brainstorm ideas with your family or a trusted friend, or consult a free financial counseling service. You may decide that talking to credit card companies and requesting a lower interest rate would help solve your problem. Or maybe you need to restructure your debt, eliminate your car payment, downsize your home, or talk to your boss about working overtime.

- Put your plan into action. Be specific about how you can follow through on the solutions you’ve devised. Perhaps that means cutting up credit cards, networking for a new job , registering at a local food bank, or selling things on eBay to pay off bills, for example.

- Monitor your progress. As we’ve all experienced recently, events that impact your financial health can happen quickly, so it’s important to regularly review your plan. Are some aspects working better than others? Do changes in interest rates, your monthly expenses, or your hourly wage, for example, mean you should revise your plan?

- Don’t get derailed by setbacks. We’re all human and no matter how tight your plan, you may stray from your goal or something unexpected could happen to derail you. Don’t beat yourself up, but get back on track as soon as possible.

The more detailed you can make your plan, the less powerless you’ll feel over your financial situation.

Whatever your plan to relieve your financial problems, setting and following a monthly budget can help keep you on track and regain your sense of control.

- Include everyday expenses in your budget, such as groceries and the cost of traveling to work, as well as monthly rent, mortgage, and utility bills.

- For items that you pay annually, such as car insurance or property tax, divide them by 12 so you can set aside money each month.

- If possible, try to factor in unexpected expenses, such as a medical co-pay or prescription charge if you fall sick, or the cost of home or car repairs.

- Set up automatic payments wherever possible to help ensure bills are paid on time and you avoid late payments and interest rate hikes.

- Prioritize your spending. If you’re having trouble covering your expenses each month, it can help to prioritize where your money goes first. For example, feeding and housing yourself and your family and keeping the power on are necessities. Paying your credit card isn’t—even if you’re behind on your payments and have debt collection companies harassing you.

- Keep looking for ways to save money. Most of us can find something in our budget that we can eliminate to help make ends meet. Regularly review your budget and look for ways to trim expenses.

- Enlist support from your spouse, partner, or kids. Make sure everyone in your household is pulling in the same direction and understands the financial goals you’re working towards.

Resolving financial problems tends to involve small steps that reap rewards over time. In the current economic climate, it’s unlikely your financial difficulties will disappear overnight. But that doesn’t mean you can’t take steps right away to ease your stress levels and find the energy and peace of mind to better deal with challenges in the long-term.

[Read: Stress Management]

Get moving. Even a little regular exercise can help ease stress, boost your mood and energy, and improve your self-esteem. Aim for 30 minutes on most days, broken up into short 10-minute bursts if that’s easier.

Practice a relaxation technique. Take time to relax each day and give your mind a break from the constant worrying. Meditating , breathing exercises, or other relaxation techniques are excellent ways to relieve stress and restore some balance to your life.