Rubric Best Practices, Examples, and Templates

A rubric is a scoring tool that identifies the different criteria relevant to an assignment, assessment, or learning outcome and states the possible levels of achievement in a specific, clear, and objective way. Use rubrics to assess project-based student work including essays, group projects, creative endeavors, and oral presentations.

Rubrics can help instructors communicate expectations to students and assess student work fairly, consistently and efficiently. Rubrics can provide students with informative feedback on their strengths and weaknesses so that they can reflect on their performance and work on areas that need improvement.

How to Get Started

Best practices, moodle how-to guides.

- Workshop Recording (Spring 2024)

- Workshop Registration

Step 1: Analyze the assignment

The first step in the rubric creation process is to analyze the assignment or assessment for which you are creating a rubric. To do this, consider the following questions:

- What is the purpose of the assignment and your feedback? What do you want students to demonstrate through the completion of this assignment (i.e. what are the learning objectives measured by it)? Is it a summative assessment, or will students use the feedback to create an improved product?

- Does the assignment break down into different or smaller tasks? Are these tasks equally important as the main assignment?

- What would an “excellent” assignment look like? An “acceptable” assignment? One that still needs major work?

- How detailed do you want the feedback you give students to be? Do you want/need to give them a grade?

Step 2: Decide what kind of rubric you will use

Types of rubrics: holistic, analytic/descriptive, single-point

Holistic Rubric. A holistic rubric includes all the criteria (such as clarity, organization, mechanics, etc.) to be considered together and included in a single evaluation. With a holistic rubric, the rater or grader assigns a single score based on an overall judgment of the student’s work, using descriptions of each performance level to assign the score.

Advantages of holistic rubrics:

- Can p lace an emphasis on what learners can demonstrate rather than what they cannot

- Save grader time by minimizing the number of evaluations to be made for each student

- Can be used consistently across raters, provided they have all been trained

Disadvantages of holistic rubrics:

- Provide less specific feedback than analytic/descriptive rubrics

- Can be difficult to choose a score when a student’s work is at varying levels across the criteria

- Any weighting of c riteria cannot be indicated in the rubric

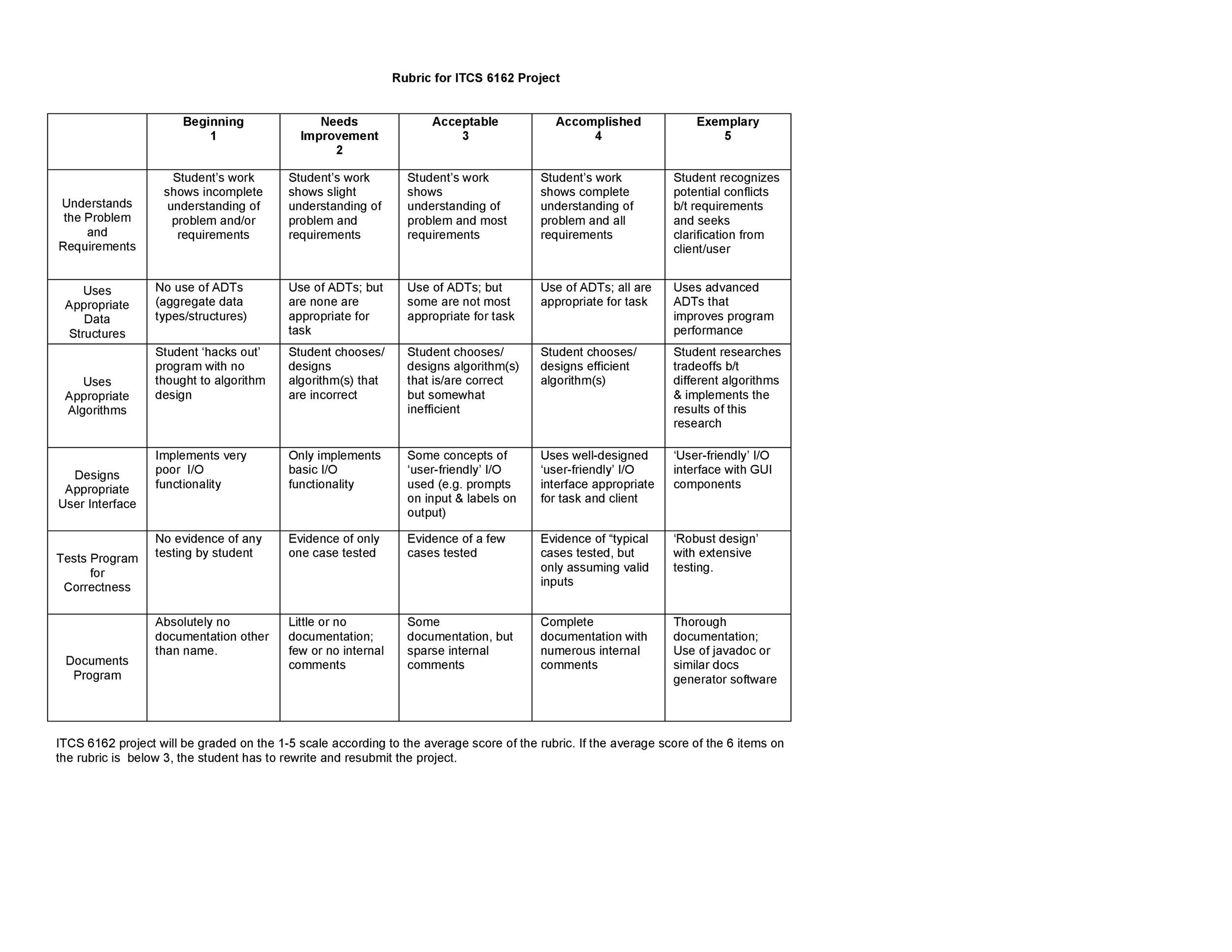

Analytic/Descriptive Rubric . An analytic or descriptive rubric often takes the form of a table with the criteria listed in the left column and with levels of performance listed across the top row. Each cell contains a description of what the specified criterion looks like at a given level of performance. Each of the criteria is scored individually.

Advantages of analytic rubrics:

- Provide detailed feedback on areas of strength or weakness

- Each criterion can be weighted to reflect its relative importance

Disadvantages of analytic rubrics:

- More time-consuming to create and use than a holistic rubric

- May not be used consistently across raters unless the cells are well defined

- May result in giving less personalized feedback

Single-Point Rubric . A single-point rubric is breaks down the components of an assignment into different criteria, but instead of describing different levels of performance, only the “proficient” level is described. Feedback space is provided for instructors to give individualized comments to help students improve and/or show where they excelled beyond the proficiency descriptors.

Advantages of single-point rubrics:

- Easier to create than an analytic/descriptive rubric

- Perhaps more likely that students will read the descriptors

- Areas of concern and excellence are open-ended

- May removes a focus on the grade/points

- May increase student creativity in project-based assignments

Disadvantage of analytic rubrics: Requires more work for instructors writing feedback

Step 3 (Optional): Look for templates and examples.

You might Google, “Rubric for persuasive essay at the college level” and see if there are any publicly available examples to start from. Ask your colleagues if they have used a rubric for a similar assignment. Some examples are also available at the end of this article. These rubrics can be a great starting point for you, but consider steps 3, 4, and 5 below to ensure that the rubric matches your assignment description, learning objectives and expectations.

Step 4: Define the assignment criteria

Make a list of the knowledge and skills are you measuring with the assignment/assessment Refer to your stated learning objectives, the assignment instructions, past examples of student work, etc. for help.

Helpful strategies for defining grading criteria:

- Collaborate with co-instructors, teaching assistants, and other colleagues

- Brainstorm and discuss with students

- Can they be observed and measured?

- Are they important and essential?

- Are they distinct from other criteria?

- Are they phrased in precise, unambiguous language?

- Revise the criteria as needed

- Consider whether some are more important than others, and how you will weight them.

Step 5: Design the rating scale

Most ratings scales include between 3 and 5 levels. Consider the following questions when designing your rating scale:

- Given what students are able to demonstrate in this assignment/assessment, what are the possible levels of achievement?

- How many levels would you like to include (more levels means more detailed descriptions)

- Will you use numbers and/or descriptive labels for each level of performance? (for example 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 and/or Exceeds expectations, Accomplished, Proficient, Developing, Beginning, etc.)

- Don’t use too many columns, and recognize that some criteria can have more columns that others . The rubric needs to be comprehensible and organized. Pick the right amount of columns so that the criteria flow logically and naturally across levels.

Step 6: Write descriptions for each level of the rating scale

Artificial Intelligence tools like Chat GPT have proven to be useful tools for creating a rubric. You will want to engineer your prompt that you provide the AI assistant to ensure you get what you want. For example, you might provide the assignment description, the criteria you feel are important, and the number of levels of performance you want in your prompt. Use the results as a starting point, and adjust the descriptions as needed.

Building a rubric from scratch

For a single-point rubric , describe what would be considered “proficient,” i.e. B-level work, and provide that description. You might also include suggestions for students outside of the actual rubric about how they might surpass proficient-level work.

For analytic and holistic rubrics , c reate statements of expected performance at each level of the rubric.

- Consider what descriptor is appropriate for each criteria, e.g., presence vs absence, complete vs incomplete, many vs none, major vs minor, consistent vs inconsistent, always vs never. If you have an indicator described in one level, it will need to be described in each level.

- You might start with the top/exemplary level. What does it look like when a student has achieved excellence for each/every criterion? Then, look at the “bottom” level. What does it look like when a student has not achieved the learning goals in any way? Then, complete the in-between levels.

- For an analytic rubric , do this for each particular criterion of the rubric so that every cell in the table is filled. These descriptions help students understand your expectations and their performance in regard to those expectations.

Well-written descriptions:

- Describe observable and measurable behavior

- Use parallel language across the scale

- Indicate the degree to which the standards are met

Step 7: Create your rubric

Create your rubric in a table or spreadsheet in Word, Google Docs, Sheets, etc., and then transfer it by typing it into Moodle. You can also use online tools to create the rubric, but you will still have to type the criteria, indicators, levels, etc., into Moodle. Rubric creators: Rubistar , iRubric

Step 8: Pilot-test your rubric

Prior to implementing your rubric on a live course, obtain feedback from:

- Teacher assistants

Try out your new rubric on a sample of student work. After you pilot-test your rubric, analyze the results to consider its effectiveness and revise accordingly.

- Limit the rubric to a single page for reading and grading ease

- Use parallel language . Use similar language and syntax/wording from column to column. Make sure that the rubric can be easily read from left to right or vice versa.

- Use student-friendly language . Make sure the language is learning-level appropriate. If you use academic language or concepts, you will need to teach those concepts.

- Share and discuss the rubric with your students . Students should understand that the rubric is there to help them learn, reflect, and self-assess. If students use a rubric, they will understand the expectations and their relevance to learning.

- Consider scalability and reusability of rubrics. Create rubric templates that you can alter as needed for multiple assignments.

- Maximize the descriptiveness of your language. Avoid words like “good” and “excellent.” For example, instead of saying, “uses excellent sources,” you might describe what makes a resource excellent so that students will know. You might also consider reducing the reliance on quantity, such as a number of allowable misspelled words. Focus instead, for example, on how distracting any spelling errors are.

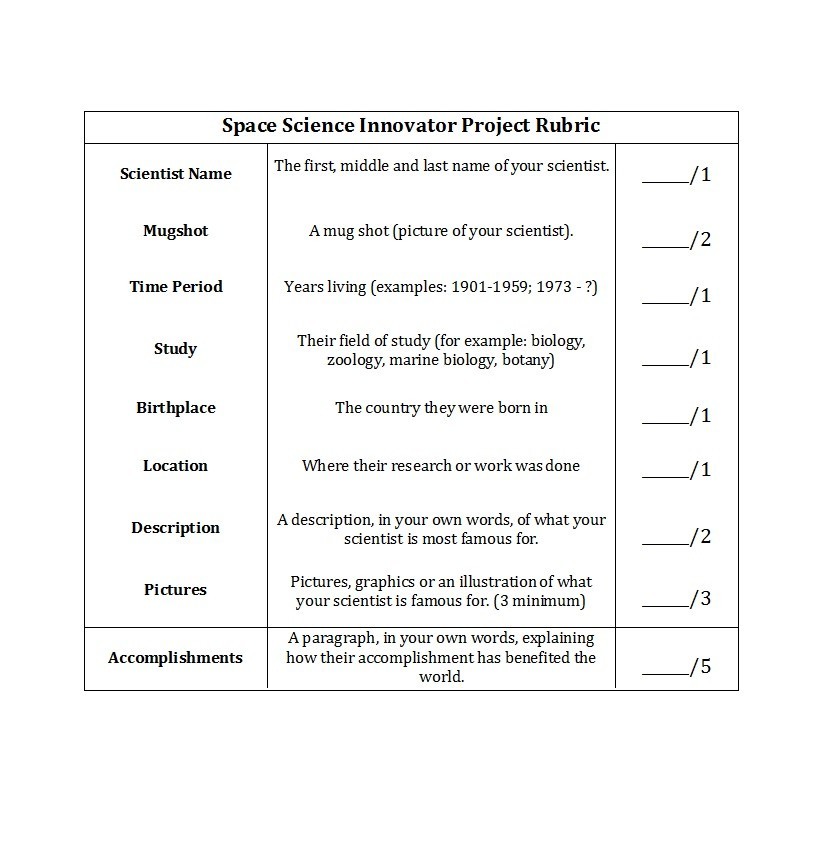

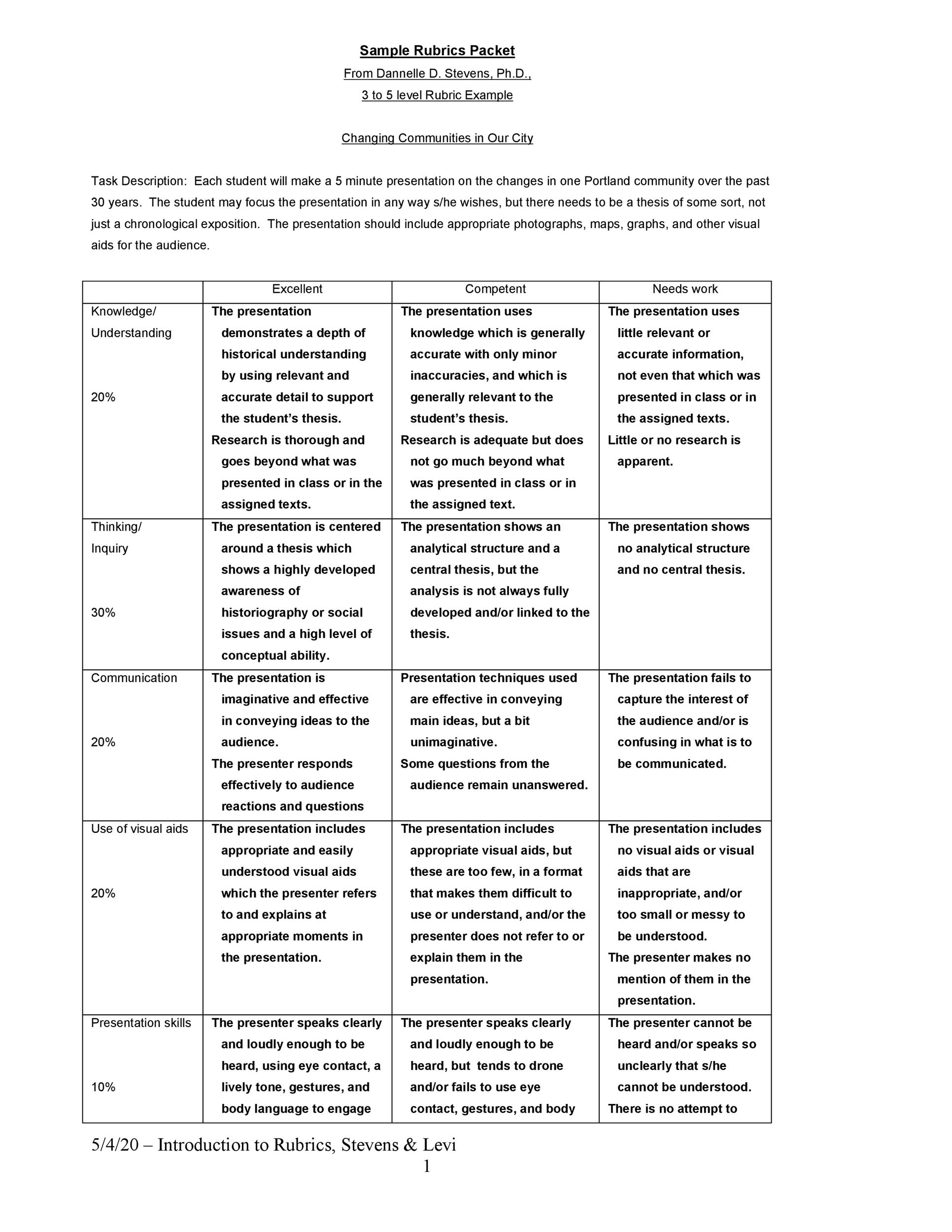

Example of an analytic rubric for a final paper

| Above Average (4) | Sufficient (3) | Developing (2) | Needs improvement (1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Thesis supported by relevant information and ideas | The central purpose of the student work is clear and supporting ideas always are always well-focused. Details are relevant, enrich the work. | The central purpose of the student work is clear and ideas are almost always focused in a way that supports the thesis. Relevant details illustrate the author’s ideas. | The central purpose of the student work is identified. Ideas are mostly focused in a way that supports the thesis. | The purpose of the student work is not well-defined. A number of central ideas do not support the thesis. Thoughts appear disconnected. |

| (Sequencing of elements/ ideas) | Information and ideas are presented in a logical sequence which flows naturally and is engaging to the audience. | Information and ideas are presented in a logical sequence which is followed by the reader with little or no difficulty. | Information and ideas are presented in an order that the audience can mostly follow. | Information and ideas are poorly sequenced. The audience has difficulty following the thread of thought. |

| (Correctness of grammar and spelling) | Minimal to no distracting errors in grammar and spelling. | The readability of the work is only slightly interrupted by spelling and/or grammatical errors. | Grammatical and/or spelling errors distract from the work. | The readability of the work is seriously hampered by spelling and/or grammatical errors. |

Example of a holistic rubric for a final paper

| The audience is able to easily identify the central message of the work and is engaged by the paper’s clear focus and relevant details. Information is presented logically and naturally. There are minimal to no distracting errors in grammar and spelling. : The audience is easily able to identify the focus of the student work which is supported by relevant ideas and supporting details. Information is presented in a logical manner that is easily followed. The readability of the work is only slightly interrupted by errors. : The audience can identify the central purpose of the student work without little difficulty and supporting ideas are present and clear. The information is presented in an orderly fashion that can be followed with little difficulty. Grammatical and spelling errors distract from the work. : The audience cannot clearly or easily identify the central ideas or purpose of the student work. Information is presented in a disorganized fashion causing the audience to have difficulty following the author’s ideas. The readability of the work is seriously hampered by errors. |

Single-Point Rubric

| Advanced (evidence of exceeding standards) | Criteria described a proficient level | Concerns (things that need work) |

|---|---|---|

| Criteria #1: Description reflecting achievement of proficient level of performance | ||

| Criteria #2: Description reflecting achievement of proficient level of performance | ||

| Criteria #3: Description reflecting achievement of proficient level of performance | ||

| Criteria #4: Description reflecting achievement of proficient level of performance | ||

| 90-100 points | 80-90 points | <80 points |

More examples:

- Single Point Rubric Template ( variation )

- Analytic Rubric Template make a copy to edit

- A Rubric for Rubrics

- Bank of Online Discussion Rubrics in different formats

- Mathematical Presentations Descriptive Rubric

- Math Proof Assessment Rubric

- Kansas State Sample Rubrics

- Design Single Point Rubric

Technology Tools: Rubrics in Moodle

- Moodle Docs: Rubrics

- Moodle Docs: Grading Guide (use for single-point rubrics)

Tools with rubrics (other than Moodle)

- Google Assignments

- Turnitin Assignments: Rubric or Grading Form

Other resources

- DePaul University (n.d.). Rubrics .

- Gonzalez, J. (2014). Know your terms: Holistic, Analytic, and Single-Point Rubrics . Cult of Pedagogy.

- Goodrich, H. (1996). Understanding rubrics . Teaching for Authentic Student Performance, 54 (4), 14-17. Retrieved from

- Miller, A. (2012). Tame the beast: tips for designing and using rubrics.

- Ragupathi, K., Lee, A. (2020). Beyond Fairness and Consistency in Grading: The Role of Rubrics in Higher Education. In: Sanger, C., Gleason, N. (eds) Diversity and Inclusion in Global Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore.

Assessment Rubrics

A rubric is commonly defined as a tool that articulates the expectations for an assignment by listing criteria, and for each criteria, describing levels of quality (Andrade, 2000; Arter & Chappuis, 2007; Stiggins, 2001). Criteria are used in determining the level at which student work meets expectations. Markers of quality give students a clear idea about what must be done to demonstrate a certain level of mastery, understanding, or proficiency (i.e., "Exceeds Expectations" does xyz, "Meets Expectations" does only xy or yz, "Developing" does only x or y or z). Rubrics can be used for any assignment in a course, or for any way in which students are asked to demonstrate what they've learned. They can also be used to facilitate self and peer-reviews of student work.

Rubrics aren't just for summative evaluation. They can be used as a teaching tool as well. When used as part of a formative assessment, they can help students understand both the holistic nature and/or specific analytics of learning expected, the level of learning expected, and then make decisions about their current level of learning to inform revision and improvement (Reddy & Andrade, 2010).

Why use rubrics?

Rubrics help instructors:

Provide students with feedback that is clear, directed and focused on ways to improve learning.

Demystify assignment expectations so students can focus on the work instead of guessing "what the instructor wants."

Reduce time spent on grading and develop consistency in how you evaluate student learning across students and throughout a class.

Rubrics help students:

Focus their efforts on completing assignments in line with clearly set expectations.

Self and Peer-reflect on their learning, making informed changes to achieve the desired learning level.

Developing a Rubric

During the process of developing a rubric, instructors might:

Select an assignment for your course - ideally one you identify as time intensive to grade, or students report as having unclear expectations.

Decide what you want students to demonstrate about their learning through that assignment. These are your criteria.

Identify the markers of quality on which you feel comfortable evaluating students’ level of learning - often along with a numerical scale (i.e., "Accomplished," "Emerging," "Beginning" for a developmental approach).

Give students the rubric ahead of time. Advise them to use it in guiding their completion of the assignment.

It can be overwhelming to create a rubric for every assignment in a class at once, so start by creating one rubric for one assignment. See how it goes and develop more from there! Also, do not reinvent the wheel. Rubric templates and examples exist all over the Internet, or consider asking colleagues if they have developed rubrics for similar assignments.

Sample Rubrics

Examples of holistic and analytic rubrics : see Tables 2 & 3 in “Rubrics: Tools for Making Learning Goals and Evaluation Criteria Explicit for Both Teachers and Learners” (Allen & Tanner, 2006)

Examples across assessment types : see “Creating and Using Rubrics,” Carnegie Mellon Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence and & Educational Innovation

“VALUE Rubrics” : see the Association of American Colleges and Universities set of free, downloadable rubrics, with foci including creative thinking, problem solving, and information literacy.

Andrade, H. 2000. Using rubrics to promote thinking and learning. Educational Leadership 57, no. 5: 13–18. Arter, J., and J. Chappuis. 2007. Creating and recognizing quality rubrics. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall. Stiggins, R.J. 2001. Student-involved classroom assessment. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Reddy, Y., & Andrade, H. (2010). A review of rubric use in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation In Higher Education, 35(4), 435-448.

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

Get Your Free 21st Century Timeline Poster ✨

15 Helpful Scoring Rubric Examples for All Grades and Subjects

In the end, they actually make grading easier.

When it comes to student assessment and evaluation, there are a lot of methods to consider. In some cases, testing is the best way to assess a student’s knowledge, and the answers are either right or wrong. But often, assessing a student’s performance is much less clear-cut. In these situations, a scoring rubric is often the way to go, especially if you’re using standards-based grading . Here’s what you need to know about this useful tool, along with lots of rubric examples to get you started.

What is a scoring rubric?

In the United States, a rubric is a guide that lays out the performance expectations for an assignment. It helps students understand what’s required of them, and guides teachers through the evaluation process. (Note that in other countries, the term “rubric” may instead refer to the set of instructions at the beginning of an exam. To avoid confusion, some people use the term “scoring rubric” instead.)

A rubric generally has three parts:

- Performance criteria: These are the various aspects on which the assignment will be evaluated. They should align with the desired learning outcomes for the assignment.

- Rating scale: This could be a number system (often 1 to 4) or words like “exceeds expectations, meets expectations, below expectations,” etc.

- Indicators: These describe the qualities needed to earn a specific rating for each of the performance criteria. The level of detail may vary depending on the assignment and the purpose of the rubric itself.

Rubrics take more time to develop up front, but they help ensure more consistent assessment, especially when the skills being assessed are more subjective. A well-developed rubric can actually save teachers a lot of time when it comes to grading. What’s more, sharing your scoring rubric with students in advance often helps improve performance . This way, students have a clear picture of what’s expected of them and what they need to do to achieve a specific grade or performance rating.

Learn more about why and how to use a rubric here.

Types of Rubric

There are three basic rubric categories, each with its own purpose.

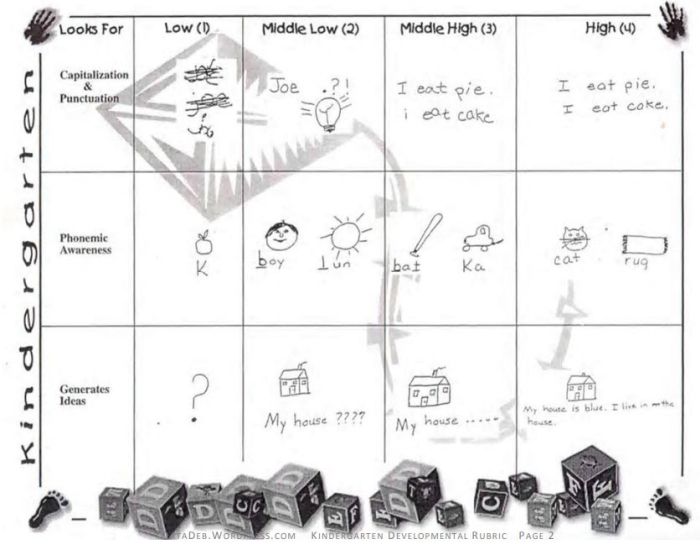

Holistic Rubric

Source: Cambrian College

This type of rubric combines all the scoring criteria in a single scale. They’re quick to create and use, but they have drawbacks. If a student’s work spans different levels, it can be difficult to decide which score to assign. They also make it harder to provide feedback on specific aspects.

Traditional letter grades are a type of holistic rubric. So are the popular “hamburger rubric” and “ cupcake rubric ” examples. Learn more about holistic rubrics here.

Analytic Rubric

Source: University of Nebraska

Analytic rubrics are much more complex and generally take a great deal more time up front to design. They include specific details of the expected learning outcomes, and descriptions of what criteria are required to meet various performance ratings in each. Each rating is assigned a point value, and the total number of points earned determines the overall grade for the assignment.

Though they’re more time-intensive to create, analytic rubrics actually save time while grading. Teachers can simply circle or highlight any relevant phrases in each rating, and add a comment or two if needed. They also help ensure consistency in grading, and make it much easier for students to understand what’s expected of them.

Learn more about analytic rubrics here.

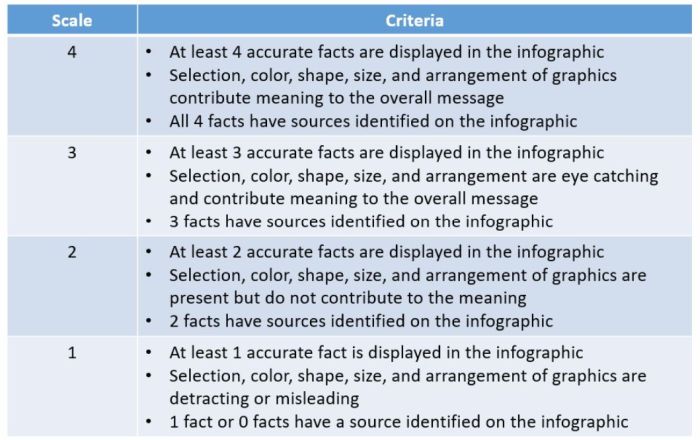

Developmental Rubric

Source: Deb’s Data Digest

A developmental rubric is a type of analytic rubric, but it’s used to assess progress along the way rather than determining a final score on an assignment. The details in these rubrics help students understand their achievements, as well as highlight the specific skills they still need to improve.

Developmental rubrics are essentially a subset of analytic rubrics. They leave off the point values, though, and focus instead on giving feedback using the criteria and indicators of performance.

Learn how to use developmental rubrics here.

Ready to create your own rubrics? Find general tips on designing rubrics here. Then, check out these examples across all grades and subjects to inspire you.

Elementary School Rubric Examples

These elementary school rubric examples come from real teachers who use them with their students. Adapt them to fit your needs and grade level.

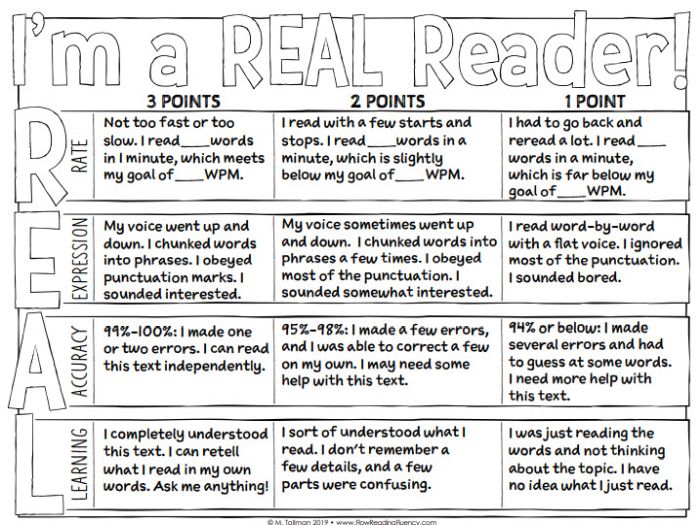

Reading Fluency Rubric

You can use this one as an analytic rubric by counting up points to earn a final score, or just to provide developmental feedback. There’s a second rubric page available specifically to assess prosody (reading with expression).

Learn more: Teacher Thrive

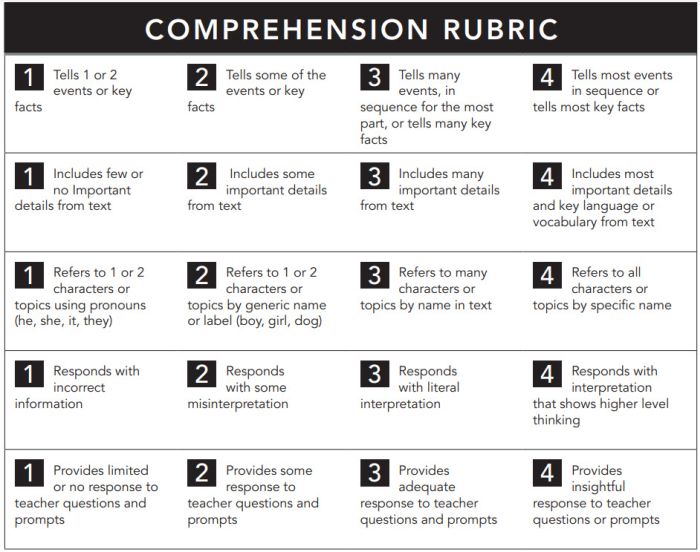

Reading Comprehension Rubric

The nice thing about this rubric is that you can use it at any grade level, for any text. If you like this style, you can get a reading fluency rubric here too.

Learn more: Pawprints Resource Center

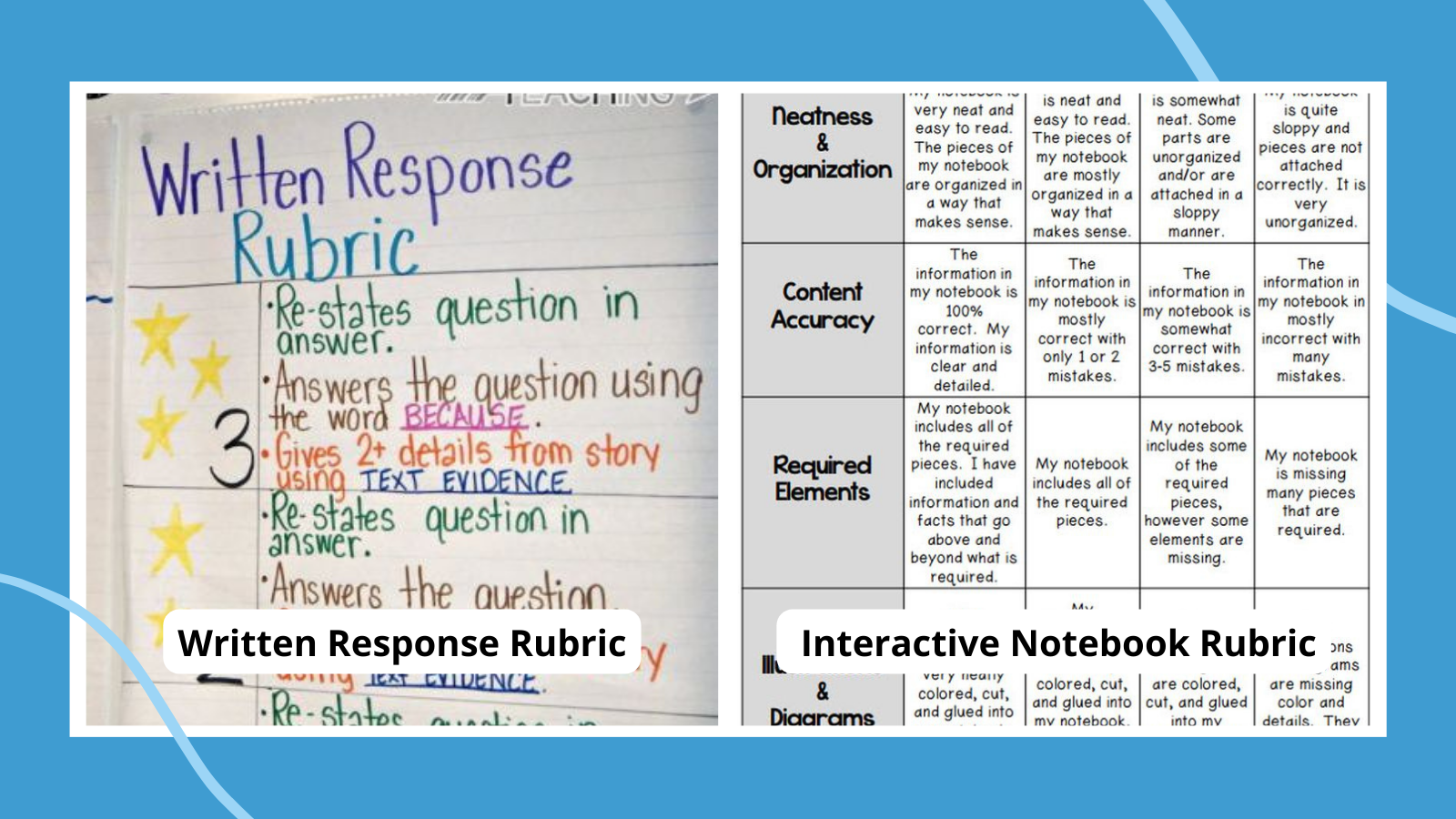

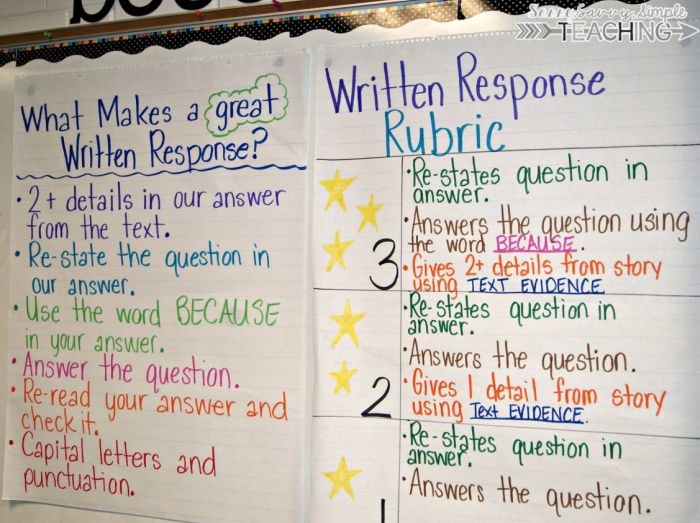

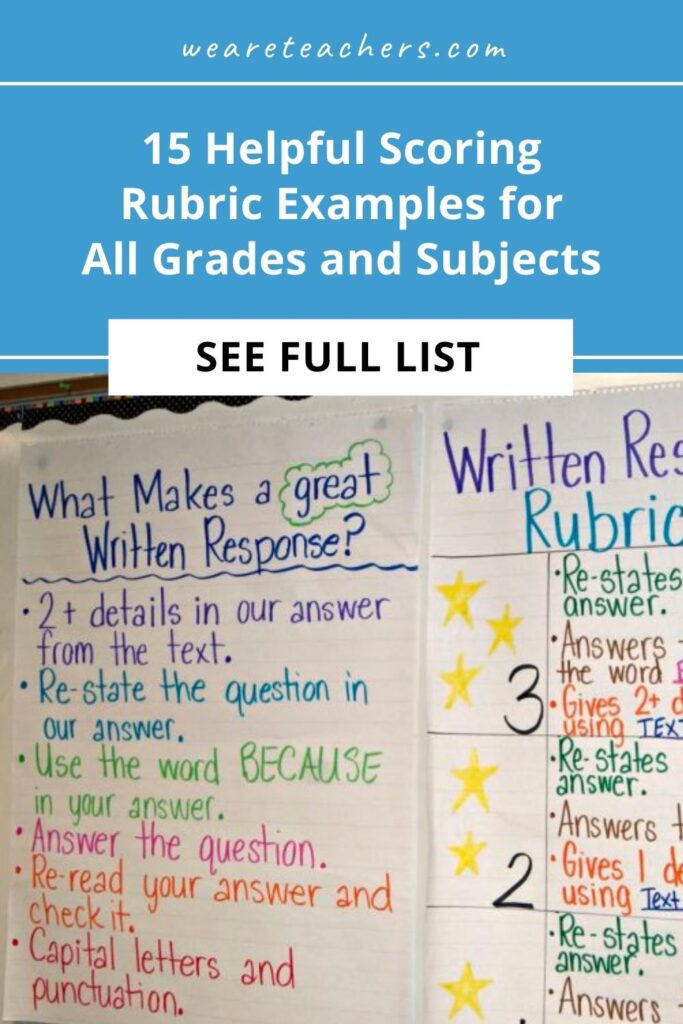

Written Response Rubric

Rubrics aren’t just for huge projects. They can also help kids work on very specific skills, like this one for improving written responses on assessments.

Learn more: Dianna Radcliffe: Teaching Upper Elementary and More

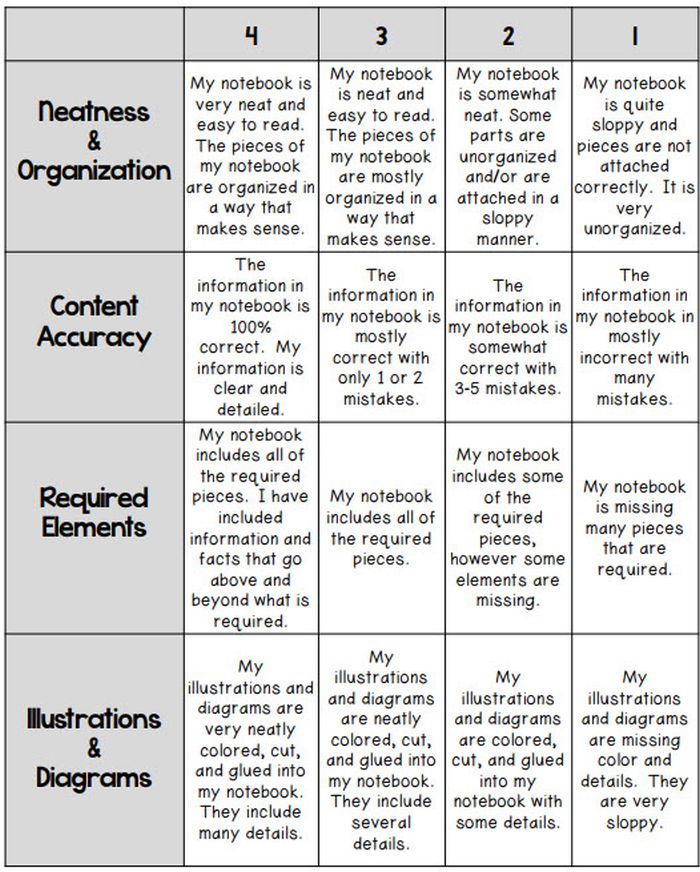

Interactive Notebook Rubric

If you use interactive notebooks as a learning tool , this rubric can help kids stay on track and meet your expectations.

Learn more: Classroom Nook

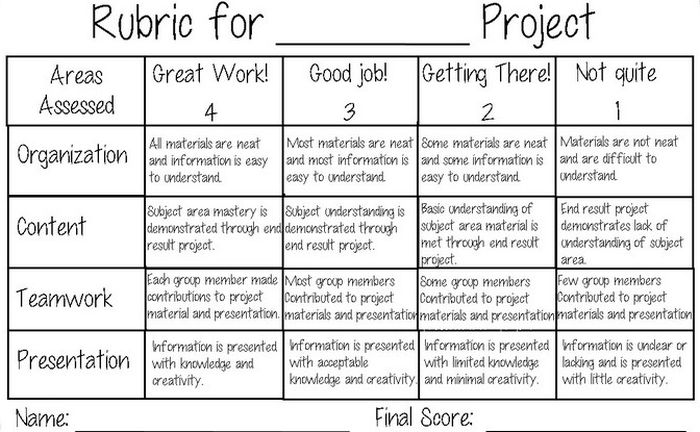

Project Rubric

Use this simple rubric as it is, or tweak it to include more specific indicators for the project you have in mind.

Learn more: Tales of a Title One Teacher

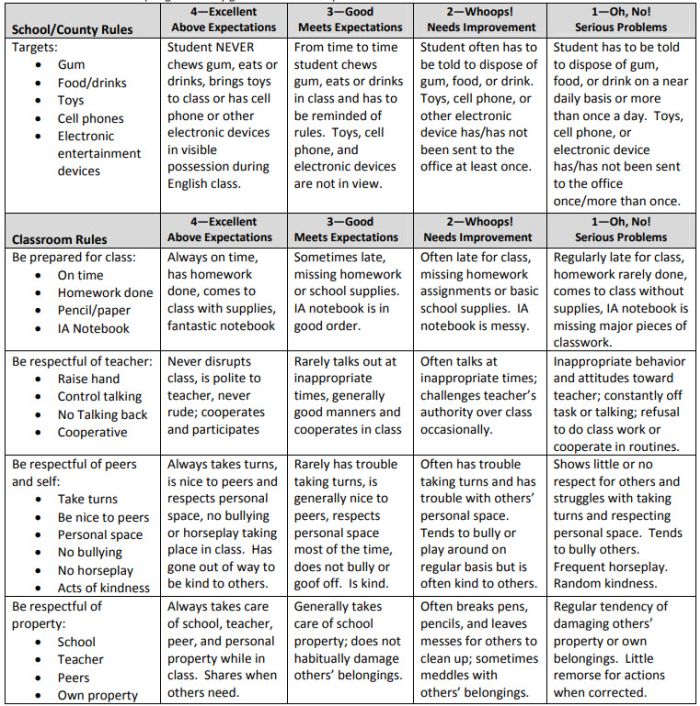

Behavior Rubric

Developmental rubrics are perfect for assessing behavior and helping students identify opportunities for improvement. Send these home regularly to keep parents in the loop.

Learn more: Teachers.net Gazette

Middle School Rubric Examples

In middle school, use rubrics to offer detailed feedback on projects, presentations, and more. Be sure to share them with students in advance, and encourage them to use them as they work so they’ll know if they’re meeting expectations.

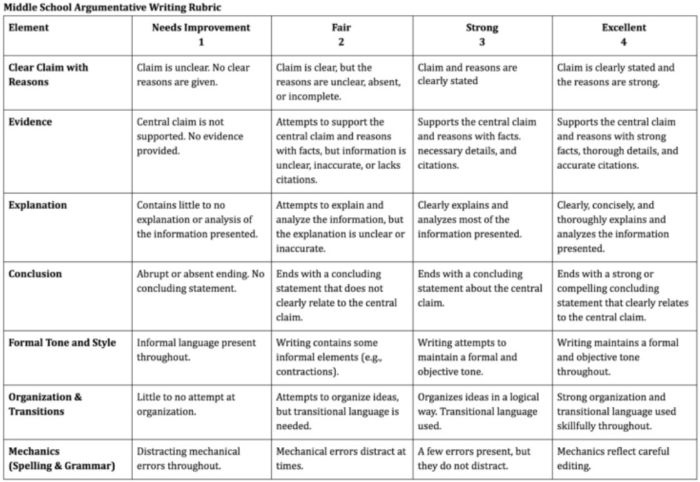

Argumentative Writing Rubric

Argumentative writing is a part of language arts, social studies, science, and more. That makes this rubric especially useful.

Learn more: Dr. Caitlyn Tucker

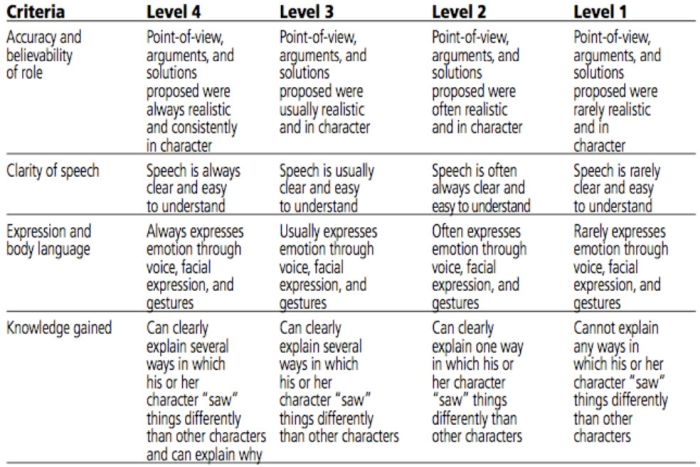

Role-Play Rubric

Role-plays can be really useful when teaching social and critical thinking skills, but it’s hard to assess them. Try a rubric like this one to evaluate and provide useful feedback.

Learn more: A Question of Influence

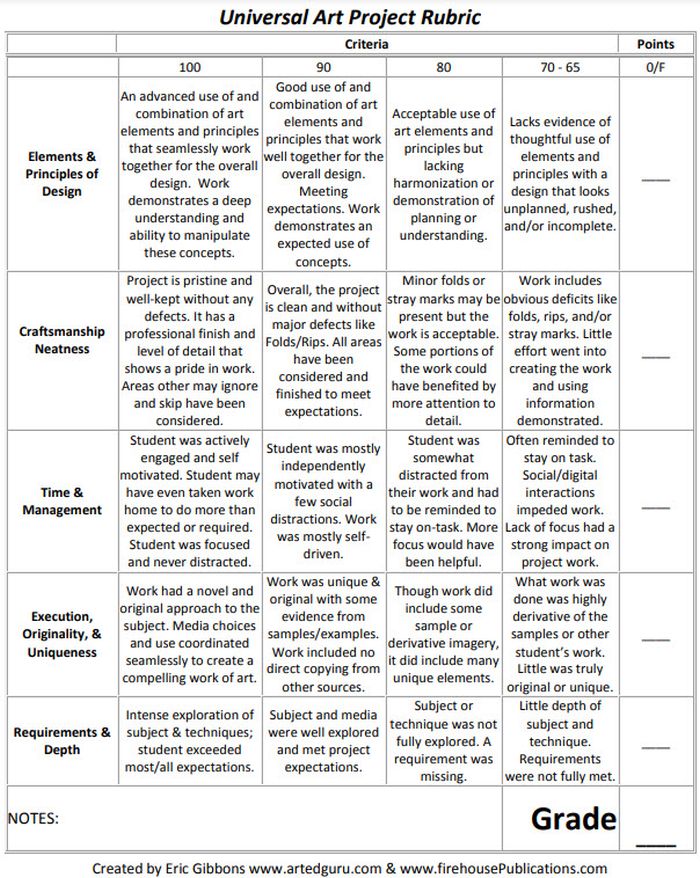

Art Project Rubric

Art is one of those subjects where grading can feel very subjective. Bring some objectivity to the process with a rubric like this.

Source: Art Ed Guru

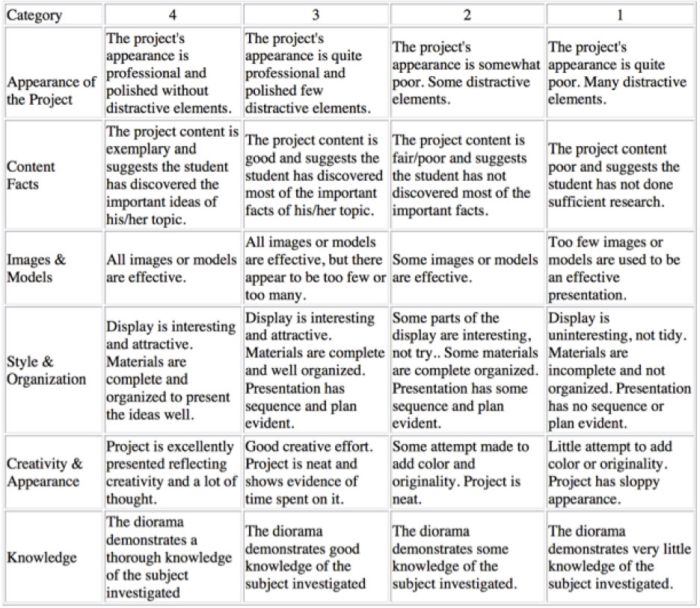

Diorama Project Rubric

You can use diorama projects in almost any subject, and they’re a great chance to encourage creativity. Simplify the grading process and help kids know how to make their projects shine with this scoring rubric.

Learn more: Historyourstory.com

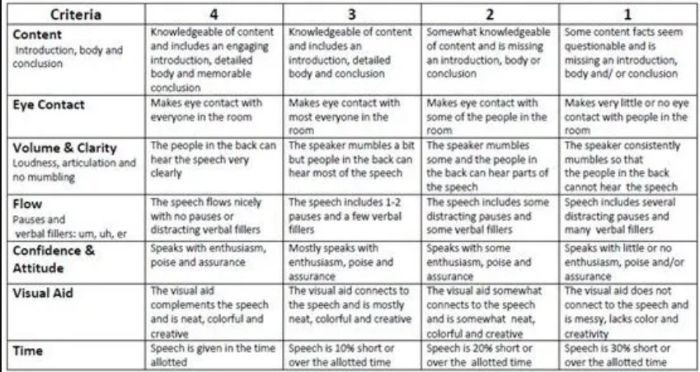

Oral Presentation Rubric

Rubrics are terrific for grading presentations, since you can include a variety of skills and other criteria. Consider letting students use a rubric like this to offer peer feedback too.

Learn more: Bright Hub Education

High School Rubric Examples

In high school, it’s important to include your grading rubrics when you give assignments like presentations, research projects, or essays. Kids who go on to college will definitely encounter rubrics, so helping them become familiar with them now will help in the future.

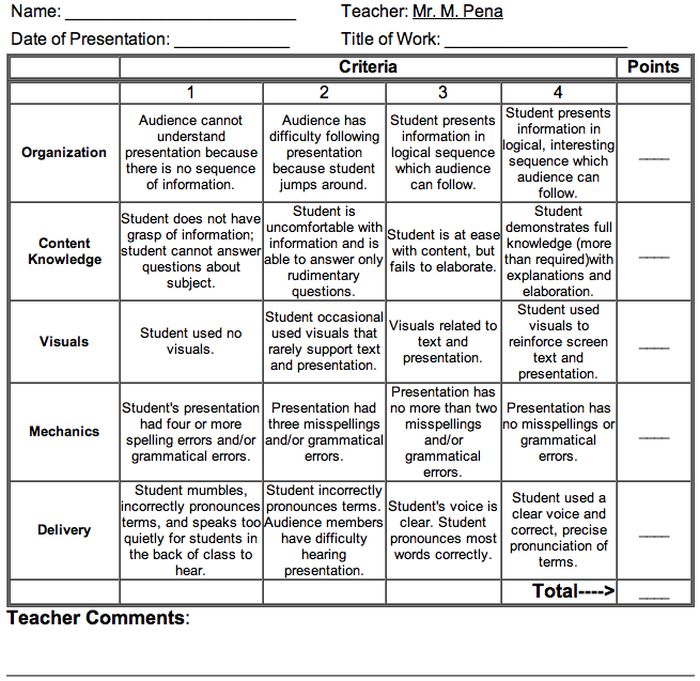

Presentation Rubric

Analyze a student’s presentation both for content and communication skills with a rubric like this one. If needed, create a separate one for content knowledge with even more criteria and indicators.

Learn more: Michael A. Pena Jr.

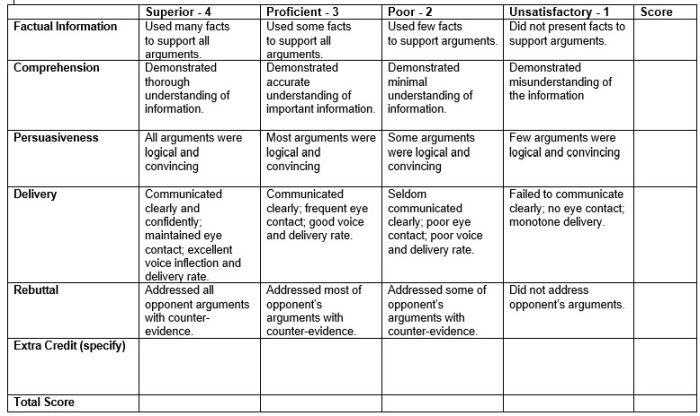

Debate Rubric

Debate is a valuable learning tool that encourages critical thinking and oral communication skills. This rubric can help you assess those skills objectively.

Learn more: Education World

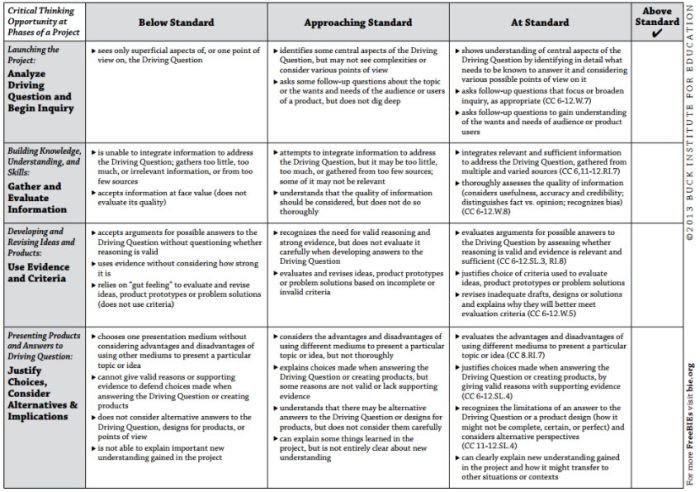

Project-Based Learning Rubric

Implementing project-based learning can be time-intensive, but the payoffs are worth it. Try this rubric to make student expectations clear and end-of-project assessment easier.

Learn more: Free Technology for Teachers

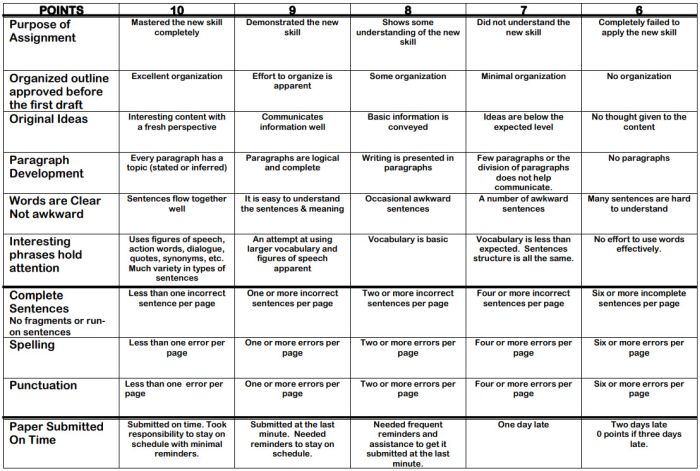

100-Point Essay Rubric

Need an easy way to convert a scoring rubric to a letter grade? This example for essay writing earns students a final score out of 100 points.

Learn more: Learn for Your Life

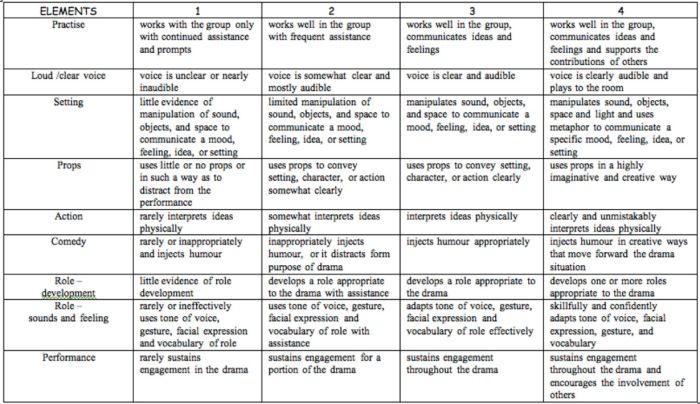

Drama Performance Rubric

If you’re unsure how to grade a student’s participation and performance in drama class, consider this example. It offers lots of objective criteria and indicators to evaluate.

Learn more: Chase March

How do you use rubrics in your classroom? Come share your thoughts and exchange ideas in the WeAreTeachers HELPLINE group on Facebook .

Plus, 25 of the best alternative assessment ideas ..

You Might Also Like

Vocabulary Worksheets To Use With Any Word List (Free Download)

Eight pages of fun and engaging word practice. Continue Reading

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

How to Use Rubrics

A rubric is a document that describes the criteria by which students’ assignments are graded. Rubrics can be helpful for:

- Making grading faster and more consistent (reducing potential bias).

- Communicating your expectations for an assignment to students before they begin.

Moreover, for assignments whose criteria are more subjective, the process of creating a rubric and articulating what it looks like to succeed at an assignment provides an opportunity to check for alignment with the intended learning outcomes and modify the assignment prompt, as needed.

Why rubrics?

Rubrics are best for assignments or projects that require evaluation on multiple dimensions. Creating a rubric makes the instructor’s standards explicit to both students and other teaching staff for the class, showing students how to meet expectations.

Additionally, the more comprehensive a rubric is, the more it allows for grading to be streamlined—students will get informative feedback about their performance from the rubric, even if they don’t have as many individualized comments. Grading can be more standardized and efficient across graders.

Finally, rubrics allow for reflection, as the instructor has to think about their standards and outcomes for the students. Using rubrics can help with self-directed learning in students as well, especially if rubrics are used to review students’ own work or their peers’, or if students are involved in creating the rubric.

How to design a rubric

1. consider the desired learning outcomes.

What learning outcomes is this assignment reinforcing and assessing? If the learning outcome seems “fuzzy,” iterate on the outcome by thinking about the expected student work product. This may help you more clearly articulate the learning outcome in a way that is measurable.

2. Define criteria

What does a successful assignment submission look like? As described by Allen and Tanner (2006), it can help develop an initial list of categories that the student should demonstrate proficiency in by completing the assignment. These categories should correlate with the intended learning outcomes you identified in Step 1, although they may be more granular in some cases. For example, if the task assesses students’ ability to formulate an effective communication strategy, what components of their communication strategy will you be looking for? Talking with colleagues or looking at existing rubrics for similar tasks may give you ideas for categories to consider for evaluation.

If you have assigned this task to students before and have samples of student work, it can help create a qualitative observation guide. This is described in Linda Suskie’s book Assessing Student Learning , where she suggests thinking about what made you decide to give one assignment an A and another a C, as well as taking notes when grading assignments and looking for common patterns. The often repeated themes that you comment on may show what your goals and expectations for students are. An example of an observation guide used to take notes on predetermined areas of an assignment is shown here .

In summary, consider the following list of questions when defining criteria for a rubric (O’Reilly and Cyr, 2006):

- What do you want students to learn from the task?

- How will students demonstrate that they have learned?

- What knowledge, skills, and behaviors are required for the task?

- What steps are required for the task?

- What are the characteristics of the final product?

After developing an initial list of criteria, prioritize the most important skills you want to target and eliminate unessential criteria or combine similar skills into one group. Most rubrics have between 3 and 8 criteria. Rubrics that are too lengthy make it difficult to grade and challenging for students to understand the key skills they need to achieve for the given assignment.

3. Create the rating scale

According to Suskie, you will want at least 3 performance levels: for adequate and inadequate performance, at the minimum, and an exemplary level to motivate students to strive for even better work. Rubrics often contain 5 levels, with an additional level between adequate and exemplary and a level between adequate and inadequate. Usually, no more than 5 levels are needed, as having too many rating levels can make it hard to consistently distinguish which rating to give an assignment (such as between a 6 or 7 out of 10). Suskie also suggests labeling each level with names to clarify which level represents the minimum acceptable performance. Labels will vary by assignment and subject, but some examples are:

- Exceeds standard, meets standard, approaching standard, below standard

- Complete evidence, partial evidence, minimal evidence, no evidence

4. Fill in descriptors

Fill in descriptors for each criterion at each performance level. Expand on the list of criteria you developed in Step 2. Begin to write full descriptions, thinking about what an exemplary example would look like for students to strive towards. Avoid vague terms like “good” and make sure to use explicit, concrete terms to describe what would make a criterion good. For instance, a criterion called “organization and structure” would be more descriptive than “writing quality.” Describe measurable behavior and use parallel language for clarity; the wording for each criterion should be very similar, except for the degree to which standards are met. For example, in a sample rubric from Chapter 9 of Suskie’s book, the criterion of “persuasiveness” has the following descriptors:

- Well Done (5): Motivating questions and advance organizers convey the main idea. Information is accurate.

- Satisfactory (3-4): Includes persuasive information.

- Needs Improvement (1-2): Include persuasive information with few facts.

- Incomplete (0): Information is incomplete, out of date, or incorrect.

These sample descriptors generally have the same sentence structure that provides consistent language across performance levels and shows the degree to which each standard is met.

5. Test your rubric

Test your rubric using a range of student work to see if the rubric is realistic. You may also consider leaving room for aspects of the assignment, such as effort, originality, and creativity, to encourage students to go beyond the rubric. If there will be multiple instructors grading, it is important to calibrate the scoring by having all graders use the rubric to grade a selected set of student work and then discuss any differences in the scores. This process helps develop consistency in grading and making the grading more valid and reliable.

Types of Rubrics

If you would like to dive deeper into rubric terminology, this section is dedicated to discussing some of the different types of rubrics. However, regardless of the type of rubric you use, it’s still most important to focus first on your learning goals and think about how the rubric will help clarify students’ expectations and measure student progress towards those learning goals.

Depending on the nature of the assignment, rubrics can come in several varieties (Suskie, 2009):

Checklist Rubric

This is the simplest kind of rubric, which lists specific features or aspects of the assignment which may be present or absent. A checklist rubric does not involve the creation of a rating scale with descriptors. See example from 18.821 project-based math class .

Rating Scale Rubric

This is like a checklist rubric, but instead of merely noting the presence or absence of a feature or aspect of the assignment, the grader also rates quality (often on a graded or Likert-style scale). See example from 6.811 assistive technology class .

Descriptive Rubric

A descriptive rubric is like a rating scale, but including descriptions of what performing to a certain level on each scale looks like. Descriptive rubrics are particularly useful in communicating instructors’ expectations of performance to students and in creating consistency with multiple graders on an assignment. This kind of rubric is probably what most people think of when they imagine a rubric. See example from 15.279 communications class .

Holistic Scoring Guide

Unlike the first 3 types of rubrics, a holistic scoring guide describes performance at different levels (e.g., A-level performance, B-level performance) holistically without analyzing the assignment into several different scales. This kind of rubric is particularly useful when there are many assignments to grade and a moderate to a high degree of subjectivity in the assessment of quality. It can be difficult to have consistency across scores, and holistic scoring guides are most helpful when making decisions quickly rather than providing detailed feedback to students. See example from 11.229 advanced writing seminar .

The kind of rubric that is most appropriate will depend on the assignment in question.

Implementation tips

Rubrics are also available to use for Canvas assignments. See this resource from Boston College for more details and guides from Canvas Instructure.

Allen, D., & Tanner, K. (2006). Rubrics: Tools for Making Learning Goals and Evaluation Criteria Explicit for Both Teachers and Learners. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 5 (3), 197-203. doi:10.1187/cbe.06-06-0168

Cherie Miot Abbanat. 11.229 Advanced Writing Seminar. Spring 2004. Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT OpenCourseWare, https://ocw.mit.edu . License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA .

Haynes Miller, Nat Stapleton, Saul Glasman, and Susan Ruff. 18.821 Project Laboratory in Mathematics. Spring 2013. Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT OpenCourseWare, https://ocw.mit.edu . License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA .

Lori Breslow, and Terence Heagney. 15.279 Management Communication for Undergraduates. Fall 2012. Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT OpenCourseWare, https://ocw.mit.edu . License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA .

O’Reilly, L., & Cyr, T. (2006). Creating a Rubric: An Online Tutorial for Faculty. Retrieved from https://www.ucdenver.edu/faculty_staff/faculty/center-for-faculty-development/Documents/Tutorials/Rubrics/index.htm

Suskie, L. (2009). Using a scoring guide or rubric to plan and evaluate an assessment. In Assessing student learning: A common sense guide (2nd edition, pp. 137-154 ) . Jossey-Bass.

William Li, Grace Teo, and Robert Miller. 6.811 Principles and Practice of Assistive Technology. Fall 2014. Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT OpenCourseWare, https://ocw.mit.edu . License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA .

How to Create a Rubric in Five Steps (With Examples)

by Amanda Melsby — February 2, 2024

OK, Confession Time

As a new teacher in the early 2000s, I avoided rubrics like the proverbial plague. I had my reasons! Rubrics always felt generic and vague. I wasn’t even sure how to create a rubric. And when I did try my hand at a rubric, it took forever to make.

What did I do before using a rubric, you ask?

I’d simply write a score and brief comment on the student’s work. I apologize to any of my former students who may recognize the following teacher comment:

45/50 Great job on this! Excellent artwork to go with your ideas!

No categories. No criteria. No real feedback. Best practice this was NOT.

What I needed was a rubric.

Download the three rubrics shown in this article.

Many years later, I am here to tell you that rubrics are your friend.

Rubrics can be wonderful tools that streamline grading for the teacher. For students, a rubric communicates the criteria for grading and encourages self-reflection on the quality of their work.

If you are just starting with rubrics, here are key questions to think through to make your rubric work for you. Once you have these components, consider using a rubric generator to begin the process or, for no work involved, start with one of ours and then determine what tweaks you would like to make for future assignments.

How to Create a Rubric in Five Steps

Step 1: identify what you want to grade..

For example, let’s say you’re having students give a presentation. Maybe you want to grade student presentations on the following:

- content of slides

- knowledgeable about the subject

- preparation/smooth presentation

- speaking conventions, eye contact, etc.

Rubrics work best when you want to assess several categories — in this case 4. Any more and it becomes cumbersome for both you and the students. The better you can define what you want to assess, the better you will be able to choose rubric criteria that will assist your grading.

Yes, there are many more categories that you could grade. Rubrics force you to be very clear about what is most important for the assignment and award points only to those categories.

Step 2: Clarify the criteria within those categories to differentiate each level.

Once you have your categories, consider the criteria that differentiate a “meets standards” from an “exceeds standards” and so on. If you use a rubric generator, the criteria will populate itself. That is helpful. Carefully read through it to determine if the AI-generated descriptors work for you. If not, tweak the criteria so it is more in line with your students’ work.

The more specific you are with the criteria, the easier it will make your grading and the clearer your grading will be to the students.

Step 3: Determine what your grading scale looks like. There are three main options.

Option 1: The grading scale uses terms such as “Exceeds Expectations”, “Meets Expectations”, etc.

Option 2: The grading scale uses numbers (for example, 4…3…2…1)

Option 3 : The grading scale uses letters (A-F)

Take a look at the examples below.

The main question to ask yourself is if the scale gives you enough flexibility to accurately identify the category that the work falls into. If you find yourself constantly wanting to circle the middle, you may need an additional level in your rubric.

Step 4: Use the rubric to add objectivity to a subjective grading task.

Rubrics are generally used for writing, presentations, and projects. Often these can be some of the most difficult assignments to grade because they are more subjective than a quiz or exam.

The rubric is there to help you grade more consistently and accurately.

Begin by marking rubrics — simply circling the descriptors that match the student’s work is fine. It’s helpful to practice with 3 to 5 pieces of work (preferably from students of varying abilities) and compare them to the categories and criteria.

Once you start to see patterns in the work, your scoring will become more accurate, consistent, and timely. Practicing with a few first will give you a sense of the quality of the work you are receiving and how they fit into the criteria you have on your rubric.

Step 5: Decide how those circles on a rubric translate into a grade in your grade book.

Chances are, each student has a variety of levels circled throughout the rubric, which will need to be translated into a score.

The easiest way is to decide on the overall point value (say 50 points) and decide on the number of maximum points per category (20 points for analysis of evidence, 20 points for quality of evidence, and 10 points for mechanics).

From there you will need to decide the point value for each level (20 points for a 4, 16 points for a 3, 14 points for a 2, and 10 points for a 1). You then add up the points from each category for the overall grade.

One note of caution: stick to one point value per level. If you try to have a range within each level, it will cause more headaches than not using a rubric at all.

Choose an assignment or two this year to experiment with these time-saving tools.

Building a rubric after having built your assignment may seem like an added step that you do not have time for. However, it can be a great time-saver.

Choose a couple of assignments this year (presentations or group work are great places to start) and jump in. It may feel clunky at first, but once you get into the groove of working with and using rubrics, you’ll be glad you did.

Featured Articles

Why and How You Should Be Randomly Calling On Your Students

The Three Forms of Assessment All New Teachers Should Utilize

For Better Results, Try Student-Centered Assessments

The Four Main Parts of a Lesson Plan Made Simple

10 Simple and Effective Ways to Check for Understanding

New Teacher Self-Care: A Practical Plan You Can Start Tomorrow

New Teachers: Here Are Five Ways You Can Give Yourself A Raise

Three Simple Ways to Boost Engagement in Any Lesson

Rethinking Your Classroom Lectures? Don’t Forget This One Key Step

Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging: Three Takeaways for New Teachers

Student Check-Ins: An Essential Tool for New Teachers

What Are Trauma-Informed Practices? Six Basics for New Teachers

Building a Better Understanding of Culturally Responsive Teaching

About Amanda

Amanda Melsby has been a professional educator for 20 years. She taught English before working as an assistant principal and later as a high school principal. Amanda holds an Ed.D. in Educational Practice and Leadership and is currently a dean of teaching and learning.

Access the FREE Mid-Year Classroom Management Guide

Pin It on Pinterest

- https://twitter.com/New_Teach_Coach

- WordPress.org

- Documentation

- Learn WordPress

Center for Teaching Innovation

Resource library.

- AACU VALUE Rubrics

Using rubrics

A rubric is a type of scoring guide that assesses and articulates specific components and expectations for an assignment. Rubrics can be used for a variety of assignments: research papers, group projects, portfolios, and presentations.

Why use rubrics?

Rubrics help instructors:

- Assess assignments consistently from student-to-student.

- Save time in grading, both short-term and long-term.

- Give timely, effective feedback and promote student learning in a sustainable way.

- Clarify expectations and components of an assignment for both students and course teaching assistants (TAs).

- Refine teaching methods by evaluating rubric results.

Rubrics help students:

- Understand expectations and components of an assignment.

- Become more aware of their learning process and progress.

- Improve work through timely and detailed feedback.

Considerations for using rubrics

When developing rubrics consider the following:

- Although it takes time to build a rubric, time will be saved in the long run as grading and providing feedback on student work will become more streamlined.

- A rubric can be a fillable pdf that can easily be emailed to students.

- They can be used for oral presentations.

- They are a great tool to evaluate teamwork and individual contribution to group tasks.

- Rubrics facilitate peer-review by setting evaluation standards. Have students use the rubric to provide peer assessment on various drafts.

- Students can use them for self-assessment to improve personal performance and learning. Encourage students to use the rubrics to assess their own work.

- Motivate students to improve their work by using rubric feedback to resubmit their work incorporating the feedback.

Getting Started with Rubrics

- Start small by creating one rubric for one assignment in a semester.

- Ask colleagues if they have developed rubrics for similar assignments or adapt rubrics that are available online. For example, the AACU has rubrics for topics such as written and oral communication, critical thinking, and creative thinking. RubiStar helps you to develop your rubric based on templates.

- Examine an assignment for your course. Outline the elements or critical attributes to be evaluated (these attributes must be objectively measurable).

- Create an evaluative range for performance quality under each element; for instance, “excellent,” “good,” “unsatisfactory.”

- Avoid using subjective or vague criteria such as “interesting” or “creative.” Instead, outline objective indicators that would fall under these categories.

- The criteria must clearly differentiate one performance level from another.

- Assign a numerical scale to each level.

- Give a draft of the rubric to your colleagues and/or TAs for feedback.

- Train students to use your rubric and solicit feedback. This will help you judge whether the rubric is clear to them and will identify any weaknesses.

- Rework the rubric based on the feedback.

Search Form

How to design effective rubrics.

Rubrics can be effective assessment tools when constructed using methods that incorporate four main criteria: validity, reliability, fairness, and efficiency. For a rubric to be valid and reliable, it must only grade the work presented (reducing the influence of instructor biases) so that anyone using the rubric would obtain the same grade (Felder and Brent 2016). Fairness ensures that the grading is transparent by providing students with access to the rubric at the beginning of the assessment while efficiency is evident when students receive detailed, timely feedback from the rubric after grading has occurred (Felder and Brent 2016). Because the most informative rubrics for student learning are analytical rubrics (Brookhart 2013), this video on how to construct an analytical rubric explains the relevant steps.

Five Steps to Design Effective Rubrics

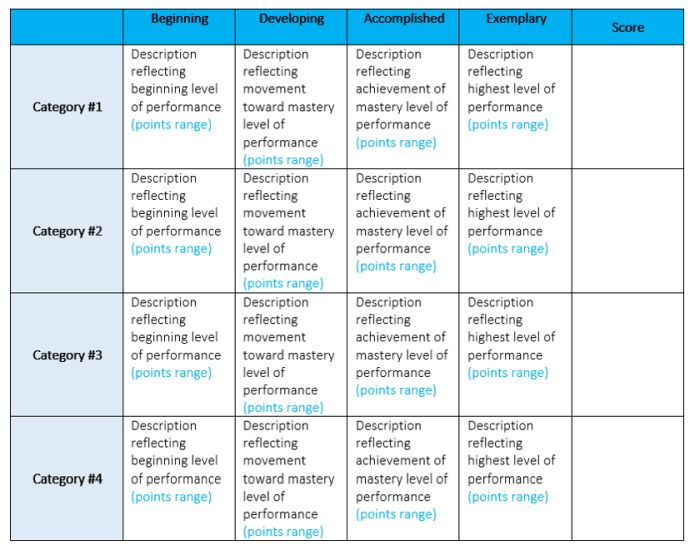

The first step in designing a rubric is determining the content, skills, or tasks you want students to be able to accomplish (Wormeli 2006) by completing an assessment. Thus, two main questions need to be answered:

- What do students need to know or do? and

- How will the instructor know when the students know or can do it?

Another way to think about this is to decide which learning objectives for the course are being evaluated using this assessment (Allen and Tanner 2006, Wormeli 2006). (More information on learning objectives can be found at Teaching@UNL). For most projects or similar assessments, more than one area of content or skill is occurring, so most rubrics assess more than one learning objective. For example, a project may require students to research a topic (content knowledge learning objective) using digital literacy skills (research learning objective) and presenting their findings (communication learning objective). Therefore, it is important to think through all the tasks or skills students will need to complete during an assessment to meet the learning objectives. Additionally, it is advised to review examples of rubrics for a specific discipline or task to find grade-level appropriate rubrics to aid in preparing a list of tasks and activities that are essential to meeting the learning objectives (Allen and Tanner 2006).

Once the learning objectives and a list of essential tasks for students is compiled and aligned to learning objectives, the next step is to determine the number of criteria for the rubric. Most rubrics have three or more criteria with most rubrics having less than a dozen criteria. It is important to remember that as more criteria are added to a rubric, a student’s cognitive load increases making it more difficult for students to remember all the assessment requirements (Allen and Tanner 2006, Wolf et al. 2008). Thus, usually 3-10 criteria are recommended for a rubric (if an assessment has less than 3 criteria, a different format (e.g., grade sheet) can be used to convey grading expectations and if a rubric has more than ten criteria, some criteria can be consolidated into a single larger category; Wolf et al. 2008). Once the number of criteria is established, the final step for the criteria aspect of a rubric is creating descriptive titles for each criterion and determining if some criteria will be weighted and thus be more influential on the grade for the assessment. Once this is accomplished, the right column of the rubric can be designed (Table 1).

| Criteria | Mastery | Proficient | Apprentice | Novice | Absent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content Knowledge (weight = 3) | Details for highest performance level | Details for meeting the criteria | Details for mid-performance level | Details for lowest performance level | No work turned in for project |

| Research Skills (weight = 1) | Details for highest performance level | . | Details for mid-performance level | . | No work turned in for project |

| Presentation Skills (weight = 2) | Details for highest performance level | Details for meeting the criteria | Details for mid-performance level | Details for lowest performance level | No presentation given |

The third aspect of a rubric design is the levels of performance and the labels for each level in the rubric. It is recommended to have 3-6 levels of performance in a rubric (Allen and Tanner 2006, Wormeli 2006, Wolf et al. 2008). The key to determining the number of performance levels for a rubric is based on how easy it is to distinguish between levels (Allen and Tanner 2006). Can the difference in student performance between a “3” and “4” be readily seen on a five-level rubric? If not, should only four levels be used for the rubric for all criteria. If most of the criteria can easily be differentiated with five levels, but only one criterion is difficult to discern, then two levels could be left blank (see “Research Skills” criterion in Table 1). It is also important to note that having fewer levels makes constructing the rubric faster but may result in ambiguous expectations and difficulty providing feedback to students.

Once the number of performance levels are set for the rubric, assign each level a name or title that indicates the level of performance. When creating the name system for the performance levels of a rubric, it is important to use terms that are not subjective, overly negative, or convey judgements (e.g., “Excellent”, “Good”, and “Bad”; Allen and Tanner 2006, Stevens and Levi 2013) and to ensure the terms use the same aspect of language (all nouns, all verbs ending in “-ing”, all adjectives, etc.; Wormeli 2006). Examples of different performance level naming systems include:

- Exemplary, Competent, Not yet competent

- Proficient, Intermediate, Novice

- Strong, Satisfactory, Not yet satisfactory

- Exceeds Expectations, Meets Expectations, Below Expectations

- Proficient, Capable, Adequate, Limited

- Exemplary, Proficient, Acceptable, Unacceptable

- Mastery, Proficient, Apprentice, Novice, Absent

Additionally, the order of the levels needs to be determined with some rubrics designed to increase in proficiency across the levels (lowest, middle, highest performance) and other designed to start with the highest performance level and move toward the lowest (highest, middle, lowest performance).

The final step in developing a rubric is to fill in the details for each performance level for each criterion. It is advised to begin by filling out the requirements for the highest performance level (what constitutes mastery for the criterion for the assessment), then fill out the lowest performance level (what shows little or no understanding for the criterion), before filling in the other performance levels for each criterion (Wormeli 2006, Stevens and Levi 2013). When writing the descriptions for a performance level avoid using subjective language (basic, competent, incomplete, poorly, flawed, etc.) unless these terms are defined explicitly for students. What tangible metrics constitute poor over adequate performance? If the instructor cannot answer this question explicitly, students will have difficulty interpreting the rubric. The details need to be objective, clear, and non-overlapping between performance levels (Wolf et al. 2008). For example, a criterion for grammar in a writing assessment would be difficult to understand or grade if the language in the mastery performance level was “Excellent use of grammar” instead of “Only one or two grammatical errors are present in the paper”.

It is essential to evaluate how well a rubric works for grading and providing feedback to students. If possible, use previous student work to test a rubric to determine how well the rubric functions for grading the assessment prior to giving the rubric to students (Wormeli 2006). After using the rubric in a class, evaluate how well students met the criteria and how easy the rubric was to use in grading (Allen and Tanner 2006). If a specific criterion has low grades associated with it, determine if the language was too subjective or confusing for students. This can be done by asking students to critique the rubric or using a student survey for the overall assessment. Alternatively, the instructor can ask a colleague or instructional designer for their feedback on the rubric. If more than one instructor is using the rubric, determine if all instructors are seeing lower grades on certain criterion. Analyzing the grades can often show where students are failing to understand the content or the assessment format or requirements.

Next, look at how well the rubric reflects the work turned in by the students (Allen and Tanner 2006, Wormeli 2006). Does the grade based on the rubric reflect what the instructor would expect for the student’s assignment? Or does the rubric result in some students receiving a higher or lower grade? If the latter is occurring, determine which aspect of the rubric needs to be “fudged” to obtain the correct grade for the assessment and update the criteria that are problematic. Alternatively, the instructor may find that the rubric is good for all criteria but that some aspects of the assessment are under or over valued in the rubric (Allen and Tanner 2006). For example, if the main learning objective is the content, but 40% of the assessment is on writing skills, the rubric may need to be weighed to allow content criteria to have a stronger influence on the grade over writing criteria.

Finally, analyze how well the rubric worked for grading the assessment overall. If the instructor needed to modify the interpretation of the rubric while grading, then the levels of performance or the number of criteria may need to be edited to better align with the learning objectives and the evidence being shown in the assessment (Allen and Tanner 2006). For example, if only three performance levels exist in the rubric, but the instructor often had to give partial credit on a criterion, then this may indicate that the rubric needs to be expanded to have more levels of performance. If instead, a specific criterion is difficult to grade or distinguish between adjacent performance levels, this may indicate that too much is being assessed in the criterion (and thus should be divided into two or more different criteria) or that the criterion is not well written and needs to be explained with more details. Reflecting on the effectiveness of a rubric should be done each time the rubric is used to ensure it is well-designed and accurately represents student learning.

Rubric Examples & Resources

UNCW College of Arts & Science “ Scoring Rubrics ” contains links to discipline-specific rubrics designed by faculty from many institutions. Most of these rubrics are downloadable Word files that could be edited for use in courses.

Syracuse University “ Examples of Rubrics ” also has rubrics by discipline with some as downloadable Word files that could be edited for use in courses.

University of Illinois – Springfield has pdf files of different types of rubrics on its “ Rubric Examples ” page. These rubrics include many different types of tasks (presenting, participation, critical thinking, etc.) from a variety of institutions

If you are building a rubric in Canvas, the rubric guide in Canvas 101 provides detailed information including video instructions: Using Rubrics: Canvas 101 (unl.edu)

Allen, D. and K. Tanner (2006). Rubrics: Tools for making learning goals and evaluation criteria explicit for both teachers and learners. CBE – Life Sciences Education 5: 197-203.

Stevens, D. D., and A. J. Levi (2013). Introduction to Rubrics: an assessment tool to save grading time, convey effective feedback, and promote student learning. Stylus Publishing, Sterling, VA, USA.

Wolf, K., M. Connelly, and A. Komara (2008). A tale of two rubrics: improving teaching and learning across the content areas through assessment. Journal of Effective Teaching 8: 21-32.

Wormeli, R. (2006). Fair isn’t always equal: assessing and grading in the differentiated classroom. Stenhouse Publishers, Portland, ME, USA.

This page was authored by Michele Larson and last updated September 15, 2022

RELATED LINKS

- How to build and use rubrics in Canvas

- Introduction to rubrics

- Faculty and Staff

Assessment and Curriculum Support Center

Creating and using rubrics.

Last Updated: 4 March 2024. Click here to view archived versions of this page.

On this page:

- What is a rubric?

- Why use a rubric?

- What are the parts of a rubric?

- Developing a rubric

- Sample rubrics

- Scoring rubric group orientation and calibration

- Suggestions for using rubrics in courses

- Equity-minded considerations for rubric development

- Tips for developing a rubric

- Additional resources & sources consulted

Note: The information and resources contained here serve only as a primers to the exciting and diverse perspectives in the field today. This page will be continually updated to reflect shared understandings of equity-minded theory and practice in learning assessment.

1. What is a rubric?

A rubric is an assessment tool often shaped like a matrix, which describes levels of achievement in a specific area of performance, understanding, or behavior.

There are two main types of rubrics:

Analytic Rubric : An analytic rubric specifies at least two characteristics to be assessed at each performance level and provides a separate score for each characteristic (e.g., a score on “formatting” and a score on “content development”).

- Advantages: provides more detailed feedback on student performance; promotes consistent scoring across students and between raters

- Disadvantages: more time consuming than applying a holistic rubric

- You want to see strengths and weaknesses.

- You want detailed feedback about student performance.

Holistic Rubric: A holistic rubrics provide a single score based on an overall impression of a student’s performance on a task.

- Advantages: quick scoring; provides an overview of student achievement; efficient for large group scoring

- Disadvantages: does not provided detailed information; not diagnostic; may be difficult for scorers to decide on one overall score

- You want a quick snapshot of achievement.

- A single dimension is adequate to define quality.

2. Why use a rubric?

- A rubric creates a common framework and language for assessment.

- Complex products or behaviors can be examined efficiently.

- Well-trained reviewers apply the same criteria and standards.

- Rubrics are criterion-referenced, rather than norm-referenced. Raters ask, “Did the student meet the criteria for level 5 of the rubric?” rather than “How well did this student do compared to other students?”

- Using rubrics can lead to substantive conversations among faculty.

- When faculty members collaborate to develop a rubric, it promotes shared expectations and grading practices.

Faculty members can use rubrics for program assessment. Examples:

The English Department collected essays from students in all sections of English 100. A random sample of essays was selected. A team of faculty members evaluated the essays by applying an analytic scoring rubric. Before applying the rubric, they “normed”–that is, they agreed on how to apply the rubric by scoring the same set of essays and discussing them until consensus was reached (see below: “6. Scoring rubric group orientation and calibration”). Biology laboratory instructors agreed to use a “Biology Lab Report Rubric” to grade students’ lab reports in all Biology lab sections, from 100- to 400-level. At the beginning of each semester, instructors met and discussed sample lab reports. They agreed on how to apply the rubric and their expectations for an “A,” “B,” “C,” etc., report in 100-level, 200-level, and 300- and 400-level lab sections. Every other year, a random sample of students’ lab reports are selected from 300- and 400-level sections. Each of those reports are then scored by a Biology professor. The score given by the course instructor is compared to the score given by the Biology professor. In addition, the scores are reported as part of the program’s assessment report. In this way, the program determines how well it is meeting its outcome, “Students will be able to write biology laboratory reports.”

3. What are the parts of a rubric?

Rubrics are composed of four basic parts. In its simplest form, the rubric includes:

- A task description . The outcome being assessed or instructions students received for an assignment.

- The characteristics to be rated (rows) . The skills, knowledge, and/or behavior to be demonstrated.

- Beginning, approaching, meeting, exceeding

- Emerging, developing, proficient, exemplary

- Novice, intermediate, intermediate high, advanced

- Beginning, striving, succeeding, soaring

- Also called a “performance description.” Explains what a student will have done to demonstrate they are at a given level of mastery for a given characteristic.

4. Developing a rubric

Step 1: Identify what you want to assess

Step 2: Identify the characteristics to be rated (rows). These are also called “dimensions.”

- Specify the skills, knowledge, and/or behaviors that you will be looking for.

- Limit the characteristics to those that are most important to the assessment.

Step 3: Identify the levels of mastery/scale (columns).

Tip: Aim for an even number (4 or 6) because when an odd number is used, the middle tends to become the “catch-all” category.

Step 4: Describe each level of mastery for each characteristic/dimension (cells).

- Describe the best work you could expect using these characteristics. This describes the top category.

- Describe an unacceptable product. This describes the lowest category.

- Develop descriptions of intermediate-level products for intermediate categories.

Important: Each description and each characteristic should be mutually exclusive.

Step 5: Test rubric.

- Apply the rubric to an assignment.

- Share with colleagues.

Tip: Faculty members often find it useful to establish the minimum score needed for the student work to be deemed passable. For example, faculty members may decided that a “1” or “2” on a 4-point scale (4=exemplary, 3=proficient, 2=marginal, 1=unacceptable), does not meet the minimum quality expectations. We encourage a standard setting session to set the score needed to meet expectations (also called a “cutscore”). Monica has posted materials from standard setting workshops, one offered on campus and the other at a national conference (includes speaker notes with the presentation slides). They may set their criteria for success as 90% of the students must score 3 or higher. If assessment study results fall short, action will need to be taken.

Step 6: Discuss with colleagues. Review feedback and revise.

Important: When developing a rubric for program assessment, enlist the help of colleagues. Rubrics promote shared expectations and consistent grading practices which benefit faculty members and students in the program.

5. Sample rubrics

Rubrics are on our Rubric Bank page and in our Rubric Repository (Graduate Degree Programs) . More are available at the Assessment and Curriculum Support Center in Crawford Hall (hard copy).

These open as Word documents and are examples from outside UH.

- Group Participation (analytic rubric)

- Participation (holistic rubric)

- Design Project (analytic rubric)

- Critical Thinking (analytic rubric)

- Media and Design Elements (analytic rubric; portfolio)

- Writing (holistic rubric; portfolio)

6. Scoring rubric group orientation and calibration

When using a rubric for program assessment purposes, faculty members apply the rubric to pieces of student work (e.g., reports, oral presentations, design projects). To produce dependable scores, each faculty member needs to interpret the rubric in the same way. The process of training faculty members to apply the rubric is called “norming.” It’s a way to calibrate the faculty members so that scores are accurate and consistent across the faculty. Below are directions for an assessment coordinator carrying out this process.

Suggested materials for a scoring session:

- Copies of the rubric

- Copies of the “anchors”: pieces of student work that illustrate each level of mastery. Suggestion: have 6 anchor pieces (2 low, 2 middle, 2 high)

- Score sheets

- Extra pens, tape, post-its, paper clips, stapler, rubber bands, etc.

Hold the scoring session in a room that:

- Allows the scorers to spread out as they rate the student pieces

- Has a chalk or white board, smart board, or flip chart

- Describe the purpose of the activity, stressing how it fits into program assessment plans. Explain that the purpose is to assess the program, not individual students or faculty, and describe ethical guidelines, including respect for confidentiality and privacy.

- Describe the nature of the products that will be reviewed, briefly summarizing how they were obtained.

- Describe the scoring rubric and its categories. Explain how it was developed.

- Analytic: Explain that readers should rate each dimension of an analytic rubric separately, and they should apply the criteria without concern for how often each score (level of mastery) is used. Holistic: Explain that readers should assign the score or level of mastery that best describes the whole piece; some aspects of the piece may not appear in that score and that is okay. They should apply the criteria without concern for how often each score is used.

- Give each scorer a copy of several student products that are exemplars of different levels of performance. Ask each scorer to independently apply the rubric to each of these products, writing their ratings on a scrap sheet of paper.

- Once everyone is done, collect everyone’s ratings and display them so everyone can see the degree of agreement. This is often done on a blackboard, with each person in turn announcing his/her ratings as they are entered on the board. Alternatively, the facilitator could ask raters to raise their hands when their rating category is announced, making the extent of agreement very clear to everyone and making it very easy to identify raters who routinely give unusually high or low ratings.

- Guide the group in a discussion of their ratings. There will be differences. This discussion is important to establish standards. Attempt to reach consensus on the most appropriate rating for each of the products being examined by inviting people who gave different ratings to explain their judgments. Raters should be encouraged to explain by making explicit references to the rubric. Usually consensus is possible, but sometimes a split decision is developed, e.g., the group may agree that a product is a “3-4” split because it has elements of both categories. This is usually not a problem. You might allow the group to revise the rubric to clarify its use but avoid allowing the group to drift away from the rubric and learning outcome(s) being assessed.

- Once the group is comfortable with how the rubric is applied, the rating begins. Explain how to record ratings using the score sheet and explain the procedures. Reviewers begin scoring.

- Are results sufficiently reliable?

- What do the results mean? Are we satisfied with the extent of students’ learning?

- Who needs to know the results?

- What are the implications of the results for curriculum, pedagogy, or student support services?

- How might the assessment process, itself, be improved?

7. Suggestions for using rubrics in courses

- Use the rubric to grade student work. Hand out the rubric with the assignment so students will know your expectations and how they’ll be graded. This should help students master your learning outcomes by guiding their work in appropriate directions.

- Use a rubric for grading student work and return the rubric with the grading on it. Faculty save time writing extensive comments; they just circle or highlight relevant segments of the rubric. Some faculty members include room for additional comments on the rubric page, either within each section or at the end.

- Develop a rubric with your students for an assignment or group project. Students can the monitor themselves and their peers using agreed-upon criteria that they helped develop. Many faculty members find that students will create higher standards for themselves than faculty members would impose on them.

- Have students apply your rubric to sample products before they create their own. Faculty members report that students are quite accurate when doing this, and this process should help them evaluate their own projects as they are being developed. The ability to evaluate, edit, and improve draft documents is an important skill.

- Have students exchange paper drafts and give peer feedback using the rubric. Then, give students a few days to revise before submitting the final draft to you. You might also require that they turn in the draft and peer-scored rubric with their final paper.

- Have students self-assess their products using the rubric and hand in their self-assessment with the product; then, faculty members and students can compare self- and faculty-generated evaluations.

8. Equity-minded considerations for rubric development

Ensure transparency by making rubric criteria public, explicit, and accessible

Transparency is a core tenet of equity-minded assessment practice. Students should know and understand how they are being evaluated as early as possible.

- Ensure the rubric is publicly available & easily accessible. We recommend publishing on your program or department website.

- Have course instructors introduce and use the program rubric in their own courses. Instructors should explain to students connections between the rubric criteria and the course and program SLOs.

- Write rubric criteria using student-focused and culturally-relevant language to ensure students understand the rubric’s purpose, the expectations it sets, and how criteria will be applied in assessing their work.

- For example, instructors can provide annotated examples of student work using the rubric language as a resource for students.

Meaningfully involve students and engage multiple perspectives

Rubrics created by faculty alone risk perpetuating unseen biases as the evaluation criteria used will inherently reflect faculty perspectives, values, and assumptions. Including students and other stakeholders in developing criteria helps to ensure performance expectations are aligned between faculty, students, and community members. Additional perspectives to be engaged might include community members, alumni, co-curricular faculty/staff, field supervisors, potential employers, or current professionals. Consider the following strategies to meaningfully involve students and engage multiple perspectives:

- Have students read each evaluation criteria and talk out loud about what they think it means. This will allow you to identify what language is clear and where there is still confusion.

- Ask students to use their language to interpret the rubric and provide a student version of the rubric.

- If you use this strategy, it is essential to create an inclusive environment where students and faculty have equal opportunity to provide input.

- Be sure to incorporate feedback from faculty and instructors who teach diverse courses, levels, and in different sub-disciplinary topics. Faculty and instructors who teach introductory courses have valuable experiences and perspectives that may differ from those who teach higher-level courses.

- Engage multiple perspectives including co-curricular faculty/staff, alumni, potential employers, and community members for feedback on evaluation criteria and rubric language. This will ensure evaluation criteria reflect what is important for all stakeholders.

- Elevate historically silenced voices in discussions on rubric development. Ensure stakeholders from historically underrepresented communities have their voices heard and valued.

Honor students’ strengths in performance descriptions

When describing students’ performance at different levels of mastery, use language that describes what students can do rather than what they cannot do. For example:

- Instead of: Students cannot make coherent arguments consistently.

- Use: Students can make coherent arguments occasionally.

9. Tips for developing a rubric

- Find and adapt an existing rubric! It is rare to find a rubric that is exactly right for your situation, but you can adapt an already existing rubric that has worked well for others and save a great deal of time. A faculty member in your program may already have a good one.

- Evaluate the rubric . Ask yourself: A) Does the rubric relate to the outcome(s) being assessed? (If yes, success!) B) Does it address anything extraneous? (If yes, delete.) C) Is the rubric useful, feasible, manageable, and practical? (If yes, find multiple ways to use the rubric: program assessment, assignment grading, peer review, student self assessment.)

- Collect samples of student work that exemplify each point on the scale or level. A rubric will not be meaningful to students or colleagues until the anchors/benchmarks/exemplars are available.

- Expect to revise.

- When you have a good rubric, SHARE IT!

10. Additional resources & sources consulted:

Rubric examples: