- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

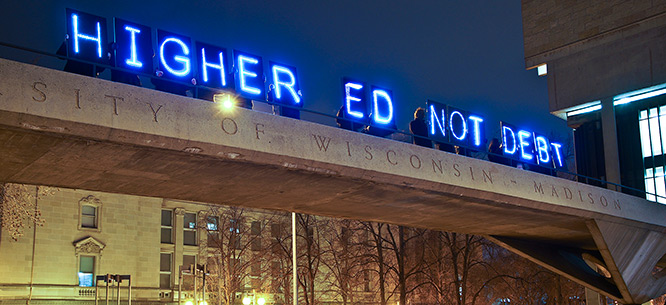

Should Higher Education Be Free?

- Vijay Govindarajan

- Jatin Desai

Disruptive new models offer an alternative to expensive tuition.

In the United States, our higher education system is broken. Since 1980, we’ve seen a 400% increase in the cost of higher education, after adjustment for inflation — a higher cost escalation than any other industry, even health care. We have recently passed the trillion dollar mark in student loan debt in the United States.

- Vijay Govindarajan is the Coxe Distinguished Professor at Dartmouth College’s Tuck School of Business, an executive fellow at Harvard Business School, and faculty partner at the Silicon Valley incubator Mach 49. He is a New York Times and Wall Street Journal bestselling author. His latest book is Fusion Strategy: How Real-Time Data and AI Will Power the Industrial Future . His Harvard Business Review articles “ Engineering Reverse Innovations ” and “ Stop the Innovation Wars ” won McKinsey Awards for best article published in HBR. His HBR articles “ How GE Is Disrupting Itself ” and “ The CEO’s Role in Business Model Reinvention ” are HBR all-time top-50 bestsellers. Follow him on LinkedIn . vgovindarajan

- JD Jatin Desai is co-founder and chief executive officer of The Desai Group and the author of Innovation Engine: Driving Execution for Breakthrough Results .

Partner Center

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

student opinion

Should College Be Free?

New Mexico unveiled a plan to make its public colleges and universities free. Should all states follow?

By The Learning Network

Find all our Student Opinion questions here.

Do you plan to attend college?

How much will cost factor into your consideration and choice of school?

The average cost of tuition and fees at an in-state public college is over $10,000 per year — an increase of more than 200 percent since 1988 , when the average was $3,190; at a private college the cost in now over $36,000 per year; and at over 120 ranked private colleges the sticker price exceeds $50,000 per year.

Additionally, over 44 million Americans collectively hold more than $1.5 trillion in student debt , and last year’s college graduates borrowed an average of $29,200 for their bachelor’s degree.

On Sept 18, New Mexico announced a plan to make tuition at all state colleges free for students regardless of family income.

Should all states follow suit? Or is it an unrealistic plan at the expense of taxpayers?

In “ New Mexico Announces Plan for Free College for State Residents, ” Simon Romero and Dana Goldstein write:

In one of the boldest state-led efforts to expand access to higher education, New Mexico is unveiling a plan on Wednesday to make tuition at its public colleges and universities free for all state residents, regardless of family income. The move comes as many American families grapple with the rising cost of higher education and as discussions about free public college gain momentum in state legislatures and on the presidential debate stage. Nearly half of the states, including New York, Oregon and Tennessee, have guaranteed free two- or four-year public college to some students. But the New Mexico proposal goes further, promising four years of tuition even to students whose families can afford to pay the sticker price. The program, which is expected to be formally announced by Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham on Wednesday and still requires legislative approval, would apply to all 29 of the state’s two- and four-year public institutions. Long one of the poorest states in the country, New Mexico plans to use climbing revenues from oil production to pay for much of the costs. Some education experts, presidential candidates and policymakers consider universal free college to be a squandering of scarce public dollars, which might be better spent offering more support to the neediest students. But others say college costs have become too overwhelming and hail the many drives toward free tuition. “I think we’re at a watershed moment,” said Caitlin Zaloom, a cultural anthropologist at New York University who has researched the impact of college costs on families. “It used to be that a high school degree could allow a young adult to enter into the middle class. We are no longer in that situation. We don’t ask people to pay for fifth grade and we also should not ask people to pay for sophomore year.”

The article continues:

Officials contend that New Mexico would benefit most from a universal approach to tuition assistance. The state’s median household income is $46,744, compared with a national median of $60,336. Most college students in the state also come from relatively disadvantaged backgrounds; almost 65 percent of New Mexico undergraduates are among the nation’s neediest students, according to the state’s higher education department. The new program in New Mexico would be open to recent graduates of high schools or high school equivalency programs in the state, and students must maintain a 2.5 grade point average. In contrast to other states, like Georgia, that have curbed access to public colleges by unauthorized immigrants, New Mexico would open the tuition program to all residents, regardless of immigration status.

It concludes:

In some ways, the burst of interest in free public college is a return to the nation’s educational past. As recently as the 1970s, some public university systems remained largely tuition-free. As a bigger and more diverse group of undergraduates entered college in recent decades, costs rose, and policymakers began to promote the idea of a degree as less of a public benefit than a private asset akin to a mortgage, according to Professor Zaloom, of N.Y.U. Many states raised tuition, and students became more reliant on grants and loans. “We should be looking at the examples from our own history,” Professor Zaloom said. Free college educations from the University of California, the City University of New York and other public systems, she added, have been “some of the most successful engines of mobility in this country.”

Students, read the entire article, then tell us:

Should college be free? Do you believe that students have a right to higher education in the same way they now have a right to elementary and secondary education?

If yes, would you place any restrictions on it, such as requiring that students maintain a 2.5 grade point average?

If not, how would you address the problem of unequal access to college and the debt that often comes with a degree?

Some critics to the plan respond that universal free college would be “a squandering of scarce public dollars” that should be spent on the “neediest students.” Do you think their concerns are justified?

Governor Lujan Grisham says, “This program is an absolute game changer for New Mexico. In the long run, we’ll see improved economic growth, improved outcomes for New Mexican workers and families and parents.” Do you agree? What are possible downsides to the plan? And is it realistic?

How concerned are you about the price of college? Do you worry about graduating with a large debt burden? How do you plan to pay for college?

Students 13 and older are invited to comment. All comments are moderated by the Learning Network staff, but please keep in mind that once your comment is accepted, it will be made public.

Winter 2024

Why Free College Is Necessary

Higher education can’t solve inequality, but the debate about free college tuition does something extremely valuable. It reintroduces the concept of public good to education discourse.

[contentblock id=subscribe-ad]

Free college is not a new idea, but, with higher education costs (and student loan debt) dominating public perception, it’s one that appeals to more and more people—including me. The national debate about free, public higher education is long overdue. But let’s get a few things out of the way.

College is the domain of the relatively privileged, and will likely stay that way for the foreseeable future, even if tuition is eliminated. As of 2012, over half of the U.S. population has “some college” or postsecondary education. That category includes everything from an auto-mechanics class at a for-profit college to a business degree from Harvard. Even with such a broadly conceived category, we are still talking about just half of all Americans.

Why aren’t more people going to college? One obvious answer would be cost, especially the cost of tuition. But the problem isn’t just that college is expensive. It is also that going to college is complicated. It takes cultural and social, not just economic, capital. It means navigating advanced courses, standardized tests, forms. It means figuring out implicit rules—rules that can change.

Eliminating tuition would probably do very little to untangle the sailor’s knot of inequalities that make it hard for most Americans to go to college. It would not address the cultural and social barriers imposed by unequal K–12 schooling, which puts a select few students on the college pathway at the expense of millions of others. Neither would it address the changing social milieu of higher education, in which the majority are now non-traditional students. (“Non-traditional” students are classified in different ways depending on who is doing the defining, but the best way to understand the category is in contrast to our assumptions of a traditional college student—young, unfettered, and continuing to college straight from high school.) How and why they go to college can depend as much on things like whether a college is within driving distance or provides one-on-one admissions counseling as it does on the price.

Given all of these factors, free college would likely benefit only an outlying group of students who are currently shut out of higher education because of cost—students with the ability and/or some cultural capital but without wealth. In other words, any conversation about college is a pretty elite one even if the word “free” is right there in the descriptor.

The discussion about free college, outside of the Democratic primary race, has also largely been limited to community colleges, with some exceptions by state. Because I am primarily interested in education as an affirmative justice mechanism, I would like all minority-serving and historically black colleges (HBCUs)—almost all of which qualify as four-year degree institutions—to be included. HBCUs disproportionately serve students facing the intersecting effects of wealth inequality, systematic K–12 disparities, and discrimination. For those reasons, any effort to use higher education as a vehicle for greater equality must include support for HBCUs, allowing them to offer accessible degrees with less (or no) debt.

The Obama administration’s free community college plan, expanded in July to include grants that would reduce tuition at HBCUs, is a step in the right direction. Yet this is only the beginning of an educational justice agenda. An educational justice policy must include institutions of higher education but cannot only include institutions of higher education. Educational justice says that schools can and do reproduce inequalities as much as they ameliorate them. Educational justice says one hundred new Universities of Phoenix is not the same as access to high-quality instruction for the maximum number of willing students. And educational justice says that jobs programs that hire for ability over “fit” must be linked to millions of new credentials, no matter what form they take or how much they cost to obtain. Without that, some free college plans could reinforce prestige divisions between different types of schools, leaving the most vulnerable students no better off in the economy than they were before.

Free college plans are also limited by the reality that not everyone wants to go to college. Some people want to work and do not want to go to college forever and ever—for good reason. While the “opportunity costs” of spending four to six years earning a degree instead of working used to be balanced out by the promise of a “good job” after college, that rationale no longer holds, especially for poor students. Free-ninety-nine will not change that.

I am clear about all of that . . . and yet I don’t care. I do not care if free college won’t solve inequality. As an isolated policy, I know that it won’t. I don’t care that it will likely only benefit the high achievers among the statistically unprivileged—those with above-average test scores, know-how, or financial means compared to their cohort. Despite these problems, today’s debate about free college tuition does something extremely valuable. It reintroduces the concept of public good to higher education discourse—a concept that fifty years of individuation, efficiency fetishes, and a rightward drift in politics have nearly pummeled out of higher education altogether. We no longer have a way to talk about public education as a collective good because even we defenders have adopted the language of competition. President Obama justified his free community college plan on the grounds that “Every American . . . should be able to earn the skills and education necessary to compete and win in the twenty-first century economy.” Meanwhile, for-profit boosters claim that their institutions allow “greater access” to college for the public. But access to what kind of education? Those of us who believe in viable, affordable higher ed need a different kind of language. You cannot organize for what you cannot name.

Already, the debate about if college should be free has forced us all to consider what higher education is for. We’re dusting off old words like class and race and labor. We are even casting about for new words like “precariat” and “generation debt.” The Debt Collective is a prime example of this. The group of hundreds of students and graduates of (mostly) for-profit colleges are doing the hard work of forming a class-based identity around debt as opposed to work or income. The broader cultural conversation about student debt, to which free college plans are a response, sets the stage for that kind of work. The good of those conversations outweighs for me the limited democratization potential of free college.

Tressie McMillan Cottom is an assistant professor of sociology at Virginia Commonwealth University and a contributing editor at Dissent . Her book Lower Ed: How For-Profit Colleges Deepen Inequality is forthcoming from the New Press.

This article is part of Dissent’s special issue of “Arguments on the Left.” Click to read contending arguments from Matt Bruenig and Mike Konczal .

Sign up for the Dissent newsletter:

Socialist thought provides us with an imaginative and moral horizon.

For insights and analysis from the longest-running democratic socialist magazine in the United States, sign up for our newsletter:

How can we get more Black teachers in the classroom?

California college savings accounts aren’t getting to all the kids who need them

How improv theater class can help kids heal from trauma

Patrick Acuña’s journey from prison to UC Irvine | Video

Family reunited after four years separated by Trump-era immigration policy

School choice advocate, CTA opponent Lance Christensen would be a very different state superintendent

Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

March 21, 2024

Raising the curtain on Prop 28: Can arts education help transform California schools?

February 27, 2024

Keeping options open: Why most students aren’t eligible to apply to California’s public universities

College & Careers

Tuition-free college is critical to our economy

Morley Winograd and Max Lubin

November 2, 2020, 13 comments.

To rebuild America’s economy in a way that offers everyone an equal chance to get ahead, federal support for free college tuition should be a priority in any economic recovery plan in 2021.

Research shows that the private and public economic benefit of free community college tuition would outweigh the cost. That’s why half of the states in the country already have some form of free college tuition.

The Democratic Party 2020 platform calls for making two years of community college tuition free for all students with a federal/state partnership similar to the Obama administration’s 2015 plan .

It envisions a program as universal and free as K-12 education is today, with all the sustainable benefits such programs (including Social Security and Medicare) enjoy. It also calls for making four years of public college tuition free, again in partnership with states, for students from families making less than $125,000 per year.

The Republican Party didn’t adopt a platform for the 2020 election, deferring to President Trump’s policies, which among other things, stand in opposition to free college. Congressional Republicans, unlike many of their state counterparts, also have not supported free college tuition in the past.

However, it should be noted that the very first state free college tuition program was initiated in 2015 by former Tennessee Gov. Bill Haslam, a Republican. Subsequently, such deep red states with Republican majorities in their state legislature such as West Virginia, Kentucky and Arkansas have adopted similar programs.

Establishing free college tuition benefits for more Americans would be the 21st-century equivalent of the Depression-era Works Progress Administration initiative.

That program not only created immediate work for the unemployed, but also offered skills training for nearly 8 million unskilled workers in the 1930s. Just as we did in the 20th century, by laying the foundation for our current system of universal free high school education and rewarding our World War II veterans with free college tuition to help ease their way back into the workforce, the 21st century system of higher education we build must include the opportunity to attend college tuition-free.

California already has taken big steps to make its community college system, the largest in the nation, tuition free by fully funding its California Promise grant program. But community college is not yet free to all students. Tuition costs — just more than $1,500 for a full course load — are waived for low-income students. Colleges don’t have to spend the Promise funds to cover tuition costs for other students so, at many colleges, students still have to pay tuition.

At the state’s four-year universities, about 60% of students at the California State University and the same share of in-state undergraduates at the 10-campus University of California, attend tuition-free as well, as a result of Cal grants , federal Pell grants and other forms of financial aid.

But making the CSU and UC systems tuition-free for even more students will require funding on a scale that only the federal government is capable of supporting, even if the benefit is only available to students from families that makes less than $125,000 a year.

It is estimated that even without this family income limitation, eliminating tuition for four years at all public colleges and universities for all students would cost taxpayers $79 billion a year, according to U.S. Department of Education data . Consider, however, that the federal government spent $91 billion in 2016 on policies that subsidized college attendance. At least some of that could be used to help make public higher education institutions tuition-free in partnership with the states.

Free college tuition programs have proved effective in helping mitigate the system’s current inequities by increasing college enrollment, lowering dependence on student loan debt and improving completion rates , especially among students of color and lower-income students who are often the first in their family to attend college.

In the first year of the TN Promise , community college enrollment in Tennessee increased by 24.7%, causing 4,000 more students to enroll. The percentage of Black students in that state’s community college population increased from 14% to 19% and the proportion of Hispanic students increased from 4% to 5%.

Students who attend community college tuition-free also graduate at higher rates. Tennessee’s first Promise student cohort had a 52.6% success rate compared to only a 38.9% success rate for their non-Promise peers. After two years of free college tuition, Rhode Island’s college-promise program saw its community college graduation rate triple and the graduation rate among students of color increase ninefold.

The impact on student debt is more obvious. Tennessee, for instance, saw its applications for student loans decrease by 17% in the first year of its program, with loan amounts decreasing by 12%. At the same time, Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) applications soared, with 40% of the entire nation’s increase in applications originating in that state in the first year of their Promise program.

Wage inequality by education, already dreadful before the pandemic, is getting worse. In May, the unemployment rate among workers without a high school diploma was nearly triple the rate of workers with a bachelor’s degree. No matter what Congress does to provide support to those affected by the pandemic and the ensuing recession, employment prospects for far too many people in our workforce will remain bleak after the pandemic recedes. Today, the fastest growing sectors of the economy are in health care, computers and information technology. To have a real shot at a job in those sectors, workers need a college credential of some form such as an industry-recognized skills certificate or an associate’s or bachelor’s degree.

The surest way to make the proven benefits of higher education available to everyone is to make college tuition-free for low and middle-income students at public colleges, and the federal government should help make that happen.

Morley Winograd is president of the Campaign for Free College Tuition . Max Lubin is CEO of Rise , a student-led nonprofit organization advocating for free college.

The opinions in this commentary are those of the author. Commentaries published on EdSource represent diverse viewpoints about California’s public education systems. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us .

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.

Share Article

Comments (13)

Leave a comment, your email address will not be published. required fields are marked * *.

Click here to cancel reply.

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy .

Genia Curtsinger 2 years ago 2 years ago

Making community college free to those who meet the admission requirements would help many people. First of all, it would make it easy for students and families, for instance; you go to college and have to pay thousands of dollars to get a college education, but if community college is free it would help so you could be saving money and get a college education for free, with no cost at all. It would make … Read More

Making community college free to those who meet the admission requirements would help many people. First of all, it would make it easy for students and families, for instance; you go to college and have to pay thousands of dollars to get a college education, but if community college is free it would help so you could be saving money and get a college education for free, with no cost at all. It would make it more affordable to the student and their families.

Therefore I think people should have free education for those who meet the admission requirements.

nothing 2 years ago 2 years ago

I feel like colleges shouldn’t be completely free, but a lot more affordable for people so everyone can have a chance to have a good college education.

Jaden Wendover 2 years ago 2 years ago

I think all colleges should be free, because why would you pay to learn?

Samantha Cole 2 years ago 2 years ago

I think college should be free because there are a lot of people that want to go to college but they can’t pay for it so they don’t go and end up in jail or working as a waitress or in a convenience store. I know I want to go to college but I can’t because my family doesn’t make enough money to send me to college but my family makes too much for financial aid.

Nick Gurrs 2 years ago 2 years ago

I feel like this subject has a lot of answers, For me personally, I believe tuition and college, in general, should be free because it will help students get out of debt and not have debt, and because it will help people who are struggling in life to get a job and make a living off a job.

NO 2 years ago 2 years ago

I think college tuition should be free. A lot of adults want to go to college and finish their education but can’t partly because they can’t afford to. Some teens need to work at a young age just so they can save money for college which I feel they shouldn’t have to. If people don’t want to go to college then they just can work and go on with their lives.

Not saying my name 3 years ago 3 years ago

I think college tuition should be free because people drop out because they can’t pay the tuition to get into college and then they can’t graduate and live a good life and they won’t get a job because it says they dropped out of school. So it would be harder to get a job and if the tuition wasn’t a thing, people would live an awesome life because of this.

Brisa 3 years ago 3 years ago

I’m not understanding. Are we not agreeing that college should be free, or are we?

m 2 years ago 2 years ago

it shouldnt

Trevor Everhart 3 years ago 3 years ago

What do you mean by there is no such thing as free tuition?

Olga Snichernacs 3 years ago 3 years ago

Nice! I enjoyed reading.

Anonymous Cat 3 years ago 3 years ago

Tuition-Free: Free tuition, or sometimes tuition free is a phrase you have heard probably a good number of times. … Therefore, free tuition to put it simply is the opportunity provide to students by select universities around the world to received a degree from their institution without paying any sum of money for the teaching.

Mister B 3 years ago 3 years ago

There is no such thing as tuition free.

EdSource Special Reports

Bill to mandate ‘science of reading’ in California schools faces teachers union opposition

The move puts the fate of AB 2222 in question, but supporters insist that there is room to negotiate changes that can help tackle the state’s literacy crisis.

California, districts try to recruit and retain Black teachers; advocates say more should be done

In the last five years, state lawmakers have made earning a credential easier and more affordable, and have offered incentives for school staff to become teachers.

Bias, extra work and feelings of isolation: 5 Black teachers tell their stories

Five Black teachers talk about what they face each day in California classrooms, and what needs to change to recruit and retain more Black teachers.

Bills address sexual harassment in California public colleges

Proposals follow a report detailing deficiencies in how the UC, CSU and California community college systems handle complaints.

EdSource in your inbox!

Stay ahead of the latest developments on education in California and nationally from early childhood to college and beyond. Sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email.

Stay informed with our daily newsletter

- University News

- Faculty & Research

- Health & Medicine

- Science & Technology

- Social Sciences

- Humanities & Arts

- Students & Alumni

- Arts & Culture

- Sports & Athletics

- The Professions

- International

- New England Guide

The Magazine

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

Class Notes & Obituaries

- Browse Class Notes

- Browse Obituaries

Collections

- Commencement

- The Context

- Harvard Squared

- Harvard in the Headlines

Support Harvard Magazine

- Why We Need Your Support

- How We Are Funded

- Ways to Support the Magazine

- Special Gifts

- Behind the Scenes

Classifieds

- Vacation Rentals & Travel

- Real Estate

- Products & Services

- Harvard Authors’ Bookshelf

- Education & Enrichment Resource

- Ad Prices & Information

- Place An Ad

Follow Harvard Magazine:

Right Now | Subsidy Shuffle

Could College Be Free?

January-February 2020

Illustration by Adam Niklewicz

Email David Deming

Visit David Deming's website.

Hear David Deming discuss free college on HKS PolicyCast

etting ahead— or getting by—is increasingly difficult in the United States without a college degree. The demand for college education is at an all-time high, but so is the price tag. David Deming—professor of public policy at the Kennedy School and professor of education and economics at the Graduate School of Education—wants to ease that tension by reallocating government spending on higher education to make public colleges tuition-free.

Deming’s argument is elegant. Public spending on higher education is unique among social services: it is an investment that pays for itself many times over in higher tax revenue generated by future college graduates, a rare example of an economic “free lunch.” In 2016 (the most recent year for which data are available), the United States spent $91 billion subsidizing access to higher education. According to Deming, that spending isn’t as progressive or effective as it could be. The National Center for Education Statistics indicates that it would cost roughly $79 billion a year to make public colleges and universities tuition-free. So, Deming asks, why not redistribute current funds to make public colleges tuition-free, instead of subsidizing higher education in other, roundabout ways?

Of the estimated $91 billion the nation spends annually on higher education, $37 billion go to tax credits and tax benefits. These tax programs ease the burden of paying for both public and private colleges, but disproportionately benefit middle-class children who are probably going to college anyway. Instead of lowering costs for those students, Deming points out, a progressive public-education assistance program should probably redirect funds to incentivize students to go to college who wouldn’t otherwise consider it.

Another $13 billion in federal spending subsidize interest payments on student loans for currently enrolled undergraduates. And the remaining $41 billion go to programs that benefit low-income students and military veterans, including $28.4 billion for Pell Grants and similar programs. Pell Grants are demand-side subsidies: they provide cash directly to those who pay for a service, i.e., students; supply-side subsidies (see below) channel funds to suppliers, such as colleges. Deming asserts that Pell Grant money, which travels with students, voucher-style, is increasingly gobbled up by low-quality, for-profit colleges. These colleges are often better at marketing their services than at graduating students or improving their graduates’ prospects, despite being highly subsidized by taxpayers . “The rise of for-profit colleges has, in some ways, been caused by disinvestment in public higher education. Our public university systems were built for a time when 20 percent of young people attended college,” says Deming. “Now it’s more like 60 percent, and we haven’t responded by devoting more resources to ensuring that young people can afford college and succeed when they get there.” As a result, an expensive, for-profit market has filled the educational shortage that government divestment has caused.

The vast majority of states have continuously divested in public education in recent decades, pushing a higher percentage of the cost burden of schools onto students. Deming believes this state-level divestment is the main reason for the precipitous rise in college tuition, which has outpaced the rest of the Consumer Price Index for 30 consecutive years. (Compounding reasons include rising salaries despite a lack of gains in productivity—a feature of many human-service-focused industries such as education and healthcare.) Against this backdrop, Deming writes, “at least some—and perhaps all—of the cost of universal tuition-free public higher education could be defrayed by redeploying money that the government is already spending.” (The need for some funding programs would remain, however, given the cost of room, board, books, and other college supplies.)

Redirecting current funding to provide tuition-free public-school degrees is only one part of Deming’s proposal. He knows that making public higher education free could hurt the quality of instruction by inciting a race to the bottom, stretching teacher-student ratios and pinching other academic resources. He therefore argues that any tuition-free plan would need to be paired with increased state and federal investment, and programs focused on getting more students to graduate. Because rates of degree completion strongly correlate with per-student spending, Deming proposes introducing a federal matching grant for the first $5,000 of net per-student spending in states that implement free college. “Luckily,” he says, “spending more money is a policy lever we know how to pull.”

Deming argues that shifting public funding to supply-side subsidies, channeled directly to public institutions, could nudge states to reinvest in public higher education. Such reinvestment would dampen the demand for low-quality, for-profit schools; increase college attendance in low-income communities; and improve the quality of services that public colleges and universities could offer. Early evidence of these positive effects has surfaced in some of the areas that are piloting free college-tuition programs, including the state of Tennessee and the city of Kalamazoo, Michigan.

Higher education is an odd market because buyers (students) often don’t have good information about school quality and it’s a once-in-a-lifetime decision. Creating a supply-side subsidy system would take some freedom of choice away from prospective undergraduates who want government funding for private, four-year degrees. But, for Deming, that’s a trade-off worth making, if the state is better able to measure the effectiveness of certain colleges and allocate subsidies accordingly. Education is more than the mere acquisition of facts—which anyone can access freely online—because minds, like markets, learn best through feedback. Quality feedback is difficult to scale well without hiring more teachers and ramping up student-support resources. That’s why Deming thinks it’s high time for the public higher-education market to get a serious injection of cash.

You might also like

Civil Discourse and Institutional Neutrality Task Forces

Two Harvard working groups assess constructive dialogue, institutional voice

Making the Public Record Public

Harvard legal database released

Paying Student-Athletes?

As NIL money flows, Harvard’s approach remains unchanged.

Most popular

Post-COVID Learning Losses

Children face potentially permanent setbacks

AWOL from Academics

Behind students' increasing pull toward extracurriculars

The World’s Costliest Health Care

Administrative costs, greed, overutilization—can these drivers of U.S. medical costs be curbed?

More to explore

Mysterious Minis

Intricate mosaics shrouded in mystery

How Birds Lost Flight

Scott Edwards discovers evolution’s master switches.

Why Americans Love to Hate Harvard

The president emeritus on elite universities’ academic accomplishments—and a rising tide of antagonism

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Student Loans

- Paying for College

Should College Be Free? The Pros and Cons

Should college be free? Understand the debate from both sides

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/KellyDilworthheadshot-c65b9cbc3b284f138ca937b8969079e6.jpg)

Types of Publicly Funded College Tuition Programs

Pros: why college should be free, cons: why college should not be free, what the free college debate means for students, how to cut your college costs now, frequently asked questions (faqs).

damircudic / Getty Images

Americans have been debating the wisdom of free college for decades, and more than 20 states now offer some type of free college program. But it wasn't until 2021 that a nationwide free college program came close to becoming reality, re-energizing a longstanding debate over whether or not free college is a good idea.

And despite a setback for the free-college advocates, the idea is still in play. The Biden administration's proposal for free community college was scrapped from the American Families Plan in October as the spending bill was being negotiated with Congress.

But close observers say that similar proposals promoting free community college have drawn solid bipartisan support in the past. "Community colleges are one of the relatively few areas where there's support from both Republicans and Democrats," said Tulane economics professor Douglas N. Harris, who has previously consulted with the Biden administration on free college, in an interview with The Balance.

To get a sense of the various arguments for and against free college, as well as the potential impacts on U.S. students and taxpayers, The Balance combed through studies investigating the design and implementation of publicly funded free tuition programs and spoke with several higher education policy experts. Here's what we learned about the current debate over free college in the U.S.—and more about how you can cut your college costs or even get free tuition through existing programs.

Key Takeaways

- Research shows that free tuition programs encourage more students to attend college and increase graduation rates, which creates a better-educated workforce and higher-earning consumers who can help boost the economy.

- Some programs are criticized for not paying students’ non-tuition expenses, for not benefiting students who need assistance most, or for steering students toward community college instead of four-year programs.

- If you want to find out about free programs in your area, the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education has a searchable database. You’ll find the link further down in this article.

Before diving into the weeds of the free college debate, it's important to note that not all free college programs are alike. Most publicly funded tuition assistance programs are restricted to the first two years of study, typically at community colleges. Free college programs also vary widely in the ways they’re designed, funded, and structured:

- Last-dollar tuition-free programs : These programs cover any remaining tuition after a student has used up other financial aid , such as Pell Grants. Most state-run free college programs fall into this category. However, these programs don’t typically help with room and board or other expenses.

- First-dollar tuition-free programs : These programs pay for students' tuition upfront, although they’re much rarer than last-dollar programs. Any remaining financial aid that a student receives can then be applied to other expenses, such as books and fees. The California College Promise Grant is a first-dollar program because it waives enrollment fees for eligible students.

- Debt-free programs : These programs pay for all of a student's college expenses , including room and board, guaranteeing that they can graduate debt-free. But they’re also much less common, likely due to their expense.

Proponents often argue that publicly funded college tuition programs eventually pay for themselves, in part by giving students the tools they need to find better jobs and earn higher incomes than they would with a high school education. The anticipated economic impact, they suggest, should help ease concerns about the costs of public financing education. Here’s a closer look at the arguments for free college programs.

A More Educated Workforce Benefits the Economy

Morley Winograd, President of the Campaign for Free College Tuition, points to the economic and tax benefits that result from the higher wages of college grads. "For government, it means more revenue," said Winograd in an interview with The Balance—the more a person earns, the more they will likely pay in taxes . In addition, "the country's economy gets better because the more skilled the workforce this country has, the better [it’s] able to compete globally." Similarly, local economies benefit from a more highly educated, better-paid workforce because higher earners have more to spend. "That's how the economy grows," Winograd explained, “by increasing disposable income."

According to Harris, the return on a government’s investment in free college can be substantial. "The additional finding of our analysis was that these things seem to consistently pass a cost-benefit analysis," he said. "The benefits seem to be at least double the cost in the long run when we look at the increased college attainment and the earnings that go along with that, relative to the cost and the additional funding and resources that go into them."

Free College Programs Encourage More Students to Attend

Convincing students from underprivileged backgrounds to take a chance on college can be a challenge, particularly when students are worried about overextending themselves financially. But free college programs tend to have more success in persuading students to consider going, said Winograd, in part because they address students' fears that they can't afford higher education . "People who wouldn't otherwise think that they could go to college, or who think the reason they can't is because it's too expensive, [will] stop, pay attention, listen, decide it's an opportunity they want to take advantage of and enroll," he said.

According to Harris, students also appear to like the certainty and simplicity of the free college message. "They didn't want to have to worry that next year they were not going to have enough money to pay their tuition bill," he said. "They don't know what their finances are going to look like a few months down the road, let alone next year, and it takes a while to get a degree. So that matters."

Free college programs can also help send "a clear and tangible message" to students and their families that a college education is attainable for them, said Michelle Dimino, an Education Senior Policy Advisor with Third Way. This kind of messaging is especially important to first-generation and low-income students, she said.

Free College Increases Graduation Rates and Financial Security

Free tuition programs appear to improve students’ chances of completing college. For example, Harris noted that his research found a meaningful link between free college tuition and higher graduation rates. "What we found is that it did increase college graduation at the two-year college level, so more students graduated than otherwise would have."

Free college tuition programs also give people a better shot at living a richer, more comfortable life, say advocates. "It's almost an economic necessity to have some college education," noted Winograd. Similar to the way a high school diploma was viewed as crucial in the 20th century, employees are now learning that they need at least two years of college to compete in a global, information-driven economy. "Free community college is a way of making that happen quickly, effectively and essentially," he explained.

Free community college isn’t a universally popular idea. While many critics point to the potential costs of funding such programs, others identify issues with the effectiveness and fairness of current attempts to cover students’ college tuition. Here’s a closer look at the concerns about free college programs.

It Would Be Too Expensive

The idea of free community college has come under particular fire from critics who worry about the cost of social spending. Since community colleges aren't nearly as expensive as four-year colleges—often costing thousands of dollars a year—critics argue that individuals can often cover their costs using other forms of financial aid . But, they point out, community college costs would quickly add up when paid for in bulk through a free college program: Biden’s proposed free college plan would have cost $49.6 billion in its first year, according to an analysis from Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. Some opponents argue that the funds could be put to better use in other ways, particularly by helping students complete their degrees.

Free College Isn't Really Free

One of the most consistent concerns that people have voiced about free college programs is that they don’t go far enough. Even if a program offers free tuition, students will need to find a way to pay for other college-related expenses , such as books, room and board, transportation, high-speed internet, and, potentially, child care. "Messaging is such a key part of this," said Dimino. Students "may apply or enroll in college, understanding it's going to be free, but then face other unexpected charges along the way."

It's important for policymakers to consider these factors when designing future free college programs. Otherwise, Dimino and other observers fear that students could potentially wind up worse off if they enroll and invest in attending college and then are forced to drop out due to financial pressures.

Free College Programs Don’t Help the Students Who Need Them Most

Critics point out that many free college programs are limited by a variety of quirks and restrictions, which can unintentionally shut out deserving students or reward wealthier ones. Most state-funded free college programs are last-dollar programs, which don’t kick in until students have applied financial aid to their tuition. That means these programs offer less support to low-income students who qualify for need-based aid—and more support for higher-income students who don’t.

Community College May Not Be the Best Path for All Students

Some critics also worry that all students will be encouraged to attend community college when some would have been better off at a four-year institution. Four-year colleges tend to have more resources than community colleges and so can offer more support to high-need students.

In addition, some research has shown that students at community colleges are less likely to be academically successful than students at four-year colleges, said Dimino. "Statistically, the data show that there are poorer outcomes for students at community colleges […] such as lower graduation rates and sometimes low transfer rates from two- to four-year schools."

With Congress focused on other priorities, a nationwide free college program is unlikely to happen anytime soon. However, some states and municipalities offer free tuition programs, so students may be able to access some form of free college, depending on where they live. A good resource is the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education’s searchable database of Promise Programs , which lists more than 120 free community college programs, though the majority are limited to California residents.

In the meantime, school leaders and policymakers may shift their focus to other access and equity interventions for low-income students. For example, higher education experts Eileen Strempel and Stephen Handel published a book in 2021 titled "Beyond Free College: Making Higher Education Work for 21st Century Students." The book argues in part that policymakers should focus more strongly on college completion, not just college access. "There hasn't been enough laser-focus on how we actually get people to complete their degrees," noted Strempel in an interview with The Balance.

Rather than just improving access for low-income college students, Strempel and Handel argue that decision-makers should instead look more closely at the social and economic issues that affect students , such as food and housing insecurity, child care, transportation, and personal technology. For example, "If you don't have a computer, you don't have access to your education anymore," said Strempel. "It's like today's pencil."

Saving money on college costs can be challenging, but you can take steps to reduce your cost of living. For example, if you're interested in a college but haven't yet enrolled, pay close attention to where it's located and how much residents typically pay for major expenses, such as housing, utilities, and food. If the college is located in a high-cost area, it could be tough to justify the living expenses you'll incur. Similarly, if you plan to commute, take the time to check gas or public transportation prices and calculate how much you'll likely have to spend per month to go to and from campus several times a week.

Now that more colleges offer classes online, it may also be worth looking at lower-cost programs in areas that are farther from where you live, particularly if they allow you to graduate without setting foot on campus. Also check out state and federal financial aid programs that can help you slim down your expenses, or, in some cases, pay for them completely. Finally, look into need-based and merit-based grants and scholarships that can help you cover even more of your expenses. Also consider applying to no-loan colleges , which promise to help students graduate without going into debt.

Should community college be free?

It’s a big question with varying viewpoints. Supporters of free community college cite the economic contributions of a more educated workforce and the individual benefit of financial security, while critics caution against the potential expense and the inefficiency of last-dollar free college programs.

What states offer free college?

More than 20 states offer some type of tuition-free college program, including Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, Michigan, Nevada, New York, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Virginia, and Washington State. The University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education lists 115 last-dollar community college programs and 16 first-dollar community college programs, though the majority are limited to California residents.

Is there a free college?

There is no such thing as a truly free college education. But some colleges offer free tuition programs for students, and more than 20 states offer some type of tuition-free college program. In addition, students may also want to check out employer-based programs. A number of big employers now offer to pay for their employees' college tuition . Finally, some students may qualify for enough financial aid or scholarships to cover most of their college costs.

The White House. “ Build Back Better Framework ,” see “Bringing Down Costs, Reducing Inflationary Pressures, and Strengthening the Middle Class.”

The White House. “ Fact Sheet: How the Build Back Better Plan Will Create a Better Future for Young Americans ,” see “Education and Workforce Opportunities.”

Coast Community College District. “ California College Promise Grant .”

Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. “ The Dollars and Cents of Free College ,” see “Biden’s Free College Plan Would Pay for Itself Within 10 Years.”

Third Way. “ Why Free College Could Increase Inequality .”

Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. “ The Dollars and Cents of Free College ,” see “Free-College Programs Have Different Effects on Race and Class Equity.”

University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education. “ College Promise Programs: A Comprehensive Catalog of College Promise Programs in the United States .”

What you need to know about the right to education

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights affirms that education is a fundamental human right for everyone and this right was further detailed in the Convention against Discrimination in Education. What exactly does that mean?

Why is education a fundamental human right?

The right to education is a human right and indispensable for the exercise of other human rights.

- Quality education aims to ensure the development of a fully-rounded human being.

- It is one of the most powerful tools in lifting socially excluded children and adults out of poverty and into society. UNESCO data shows that if all adults completed secondary education, globally the number of poor people could be reduced by more than half.

- It narrows the gender gap for girls and women. A UN study showed that each year of schooling reduces the probability of infant mortality by 5 to 10 per cent.

- For this human right to work there must be equality of opportunity, universal access, and enforceable and monitored quality standards.

What does the right to education entail?

- Primary education that is free, compulsory and universal

- Secondary education, including technical and vocational, that is generally available, accessible to all and progressively free

- Higher education, accessible to all on the basis of individual capacity and progressively free

- Fundamental education for individuals who have not completed education

- Professional training opportunities

- Equal quality of education through minimum standards

- Quality teaching and supplies for teachers

- Adequate fellowship system and material condition for teaching staff

- Freedom of choice

What is the current situation?

- About 258 million children and youth are out of school, according to UIS data for the school year ending in 2018. The total includes 59 million children of primary school age, 62 million of lower secondary school age and 138 million of upper secondary age.

155 countries legally guarantee 9 years or more of compulsory education

- Only 99 countries legally guarantee at least 12 years of free education

- 8.2% of primary school age children does not go to primary school Only six in ten young people will be finishing secondary school in 2030 The youth literacy rate (15-24) is of 91.73%, meaning 102 million youth lack basic literacy skills.

How is the right to education ensured?

The right to education is established by two means - normative international instruments and political commitments by governments. A solid international framework of conventions and treaties exist to protect the right to education and States that sign up to them agree to respect, protect and fulfil this right.

How does UNESCO work to ensure the right to education?

UNESCO develops, monitors and promotes education norms and standards to guarantee the right to education at country level and advance the aims of the Education 2030 Agenda. It works to ensure States' legal obligations are reflected in national legal frameworks and translated into concrete policies.

- Monitoring the implementation of the right to education at country level

- Supporting States to establish solid national frameworks creating the legal foundation and conditions for sustainable quality education for all

- Advocating on the right to education principles and legal obligations through research and studies on key issues

- Maintaining global online tools on the right to education

- Enhancing capacities, reporting mechanisms and awareness on key challenges

- Developing partnerships and networks around key issues

How is the right to education monitored and enforced by UNESCO?

- UNESCO's Constitution requires Member States to regularly report on measures to implement standard-setting instruments at country level through regular consultations.

- Through collaboration with UN human rights bodies, UNESCO addresses recommendations to countries to improve the situation of the right to education at national level.

- Through the dedicated online Observatory , UNESCO takes stock of the implementation of the right to education in 195 States.

- Through its interactive Atlas , UNESCO monitors the implementation right to education of girls and women in countries

- Based on its monitoring work, UNESCO provides technical assistance and policy advice to Member States that seek to review, develop, improve and reform their legal and policy frameworks.

What happens if States do not fulfil obligations?

- International human rights instruments have established a solid normative framework for the right to education. This is not an empty declaration of intent as its provisions are legally binding. All countries in the world have ratified at least one treaty covering certain aspects of the right to education. This means that all States are held to account, through legal mechanisms.

- Enforcement of the right to education: At international level, human rights' mechanisms are competent to receive individual complaints and have settled right to education breaches this way.

- Justiciability of the right to education: Where their right to education has been violated, citizens must be able to have legal recourse before the law courts or administrative tribunals.

What are the major challenges to ensure the right to education?

- Providing free and compulsory education to all

- 155 countries legally guarantee 9 years or more of compulsory education.

- Only 99 countries legally guarantee at least 12 years of free education.

- Eliminating inequalities and disparities in education

While only 4% of the poorest youth complete upper secondary school in low-income countries, 36% of the richest do. In lower-middle-income countries, the gap is even wider: while only 14% of the poorest youth complete upper secondary school, 72% of the richest do.

- Migration and displacement

According to a 2019 UNHCR report, of the 7.1 million refugee children of school age, 3.7 million - more than half - do not go to school.

- Privatization and its impact on the right to education

States need to strike a balance between educational freedom and ensuring everyone receives a quality education.

- Financing of education

The Education 2030 Agenda requires States to allocate at least 4-6 per cent of GDP and/or at least 15-20 per cent of public expenditure to education.

- Quality imperatives and valuing the teaching profession

Two-thirds of the estimated 617 million children and adolescents who cannot read a simple sentence or manage a basic mathematics calculation are in the classroom.

- Say no to discrimination in education! - #RightToEducation campaign

Related items

- Right to education

HerAtlas: Background, rationale and objectives 12 March 2024

HerAtlas: Disclaimer and terms of use 12 March 2024

Other recent news

Quality Education pp 328–337 Cite as

Free Education: Origins, Achievements, and Current Situation

- Michael M. Kretzer 6

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2020

312 Accesses

1 Citations

Part of the book series: Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals ((ENUNSDG))

Free Education is defined as the abolishment of school fees. In general, two types of fees exist. Firstly, direct fees or costs such as tuition fees or textbook fees and so on, which means they are spent directly on education. Secondly, indirect fees or costs, which are not directly used for educational purposes, but are a necessity, such as travel expenses to school. There is, however, no consensus about a definition of Free Education or Free Primary Education (FPE), as the predominantly used terminology are used equivalent (Inoue and Oketch 2008 : 44). Free Education is mainly seen as FPE and includes the abolishment of tuition or textbook fees (UNESCO 2002 ). Hence, Free Education is limited most of the time to primary schools and the abolishment of direct fees, but it does not mean a totally free and cost-free education for parents. Research has shown that the best is to lower the direct and the indirect costs for education, as this increases the chances of children being...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Ahmed R, Sayed Y (2009) Promoting access and enhancing education opportunities? The case of ‘no-fees schools’ in South Africa. Compare 39(2):203–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920902750467

Article Google Scholar

Akaguri L (2014) Fee-free public or low-fee private basic education in rural Ghana: how does the cost influence the choice of the poor? Compare 44(2):140–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2013.796816

Akyeampong K (2009) Revisiting Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education (FCUBE) in Ghana. Comp Educ 45(2):175–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060902920534

Al-Samarrai S, Zaman H (2007) Abolishing school fees in Malawi: the impact on education access and equity. Educ Econ 15(3):359–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/09645290701273632

Altbach PG, Klemencic M (2014) Student activism remains a potent force worldwide. Int High Educ 76:2–3

Google Scholar

Booysen S (2016) Fees must fall. Student revolt, decolonisation and governance in South Africa. Wits University Press, Johannesburg

Botha RJ(N) (2002) Outcomes-based education and educational reform in South Africa. Int J Leadersh Educ 5(4):S. 361–S. 371. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603120110118831

Bray M, Kwo O (2013) Behind the façade of fee-free education: shadow education and its implications for social justice. Oxf Rev Educ 39(4):480–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2013.821852

Cabalin C (2012) Neoliberal education and student movements in Chile: inequalities and malaise. Policy Futures Educ 10(2):219–228. https://doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2012.10.2.219

Chimombo J (2009) Changing patterns of access to basic education in Malawi: a story of a mixed bag? Comp Educ 45(2):297–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060902921003

de los Arcos B, Weller M (2018) A tale of two globes: exploring the north/south divide in engagement with open educational resources. In: Schöpfel J, Herb U (eds) Open divide: critical studies on open access. Litwin Books, Sacramento, pp 147–155

Department of Education (2006) Education on no fee schools 2007. https://www.gov.za/education-no-fee-schools-2007

Dzama E (2006) Malawian secondary school students learning of science: historical background, performance and beliefs. PhD thesis, University of Western Cape

Haßler B, Jackson AM (2010) Bridging the bandwidth gap: open educational resources and the digital divide. IEEE Trans Learn Technol 3(2):110–115. https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2010.8

Inoue K, Oketch M (2008) Implementing free primary education policy in Malawi and Ghana: equity and efficiency analysis. Peabody J Educ 83(1):41–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/01619560701649158

Kadzamira EC et al. (2009) Review of the planning and implementation of free primary education in Malawi. In: Birger Frederiksen /Dina Craissati Abolishing school fees in Africa. Lessons from Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, and Mozambique. World Bank, Washington, pp 161–202

Kayambazinthu E (1999) The language planning situation in Malawi. In: Kapman R, Baldauf R (eds) Language planning in Malawi, Mozambique and the Philippine. Multilingual Matters, Sydney, pp 15–86

Kendall N (2007) Education for all meets political democratization: free primary education and the neoliberalization of the Malawian school and state. Comp Educ Rev 51(3):281–305

Kosack S (2009) Realising education for all: defining and using the political will to invest in primary education. Comp Educ 45(4):495–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060903391586

Kretzer MM (2016) Chancen und Grenzen von “Agriculture” als Schulfach für eine nachhaltige Lebensführung. Fallstudie Karonga, Nkahata Bay und Mzimba Distrikt in Malawi. In: Engler S, Bommert W, Stengel O (eds) Regional, innovativ und gesund – Nachhaltige Ernährung als Teil der großen transformation. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen, pp 243–261

Chapter Google Scholar

Kretzer MM (2018) Implementierungspotential der Sprachenpolitik im Bildungssystem Südafrikas. Eine Untersuchung in den Provinzen Gauteng, Limpopo und North West. [Potential of the implementation of language policy in the education system of South Africa: case study of Gauteng, Limpopo and North West Province]. Unpublished PhD thesis, Justus-Liebig-University Giessen

Kretzer MM, Kaschula RH (2019) (Unused) potentials of educators’ covert language policies at public schools in Limpopo, South Africa. Curr Issues Lang Plann. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2019.1641349

Kretzer MM, Engler S, Gondwe J, Trost E (2017) Fighting resource scarcity – sustainability in the education system of Malawi – case study of Karonga, Mzimba and Nkhata Bay district. S Afr Geogr J 99(3):235–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/03736245.2016.1231624

Lewin KM (2011) Policy dialogue and target setting: do current indicators of education for all signify progress? J Educ Policy 26(4):571–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2011.555003

Matear A (2008) English language learning and education policy in Chile: can English really open doors for all? Asia Pac J Educ 28(2):131–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188790802036679

Ministry of Education and Culture Republic of Indonesia, Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan (2003) Act of the Republic of Indonesia Number 20, Year 2003 on National Education System. https://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/sites/planipolis/files/ressources/indonesia_education_act.pdf

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2018) Chile. Overview of the education system (EAG 2018). http://gpseducation.oecd.org/CountryProfile?primaryCountry=CHL&treshold=10&topic=EO

Papua New Guinea Department of Education (2012) Report on the implementation of the Tuition Fee Free (TFF) policy. https://www.education.gov.pg/documents/TFF%20Policy%20Report.pdf

Rosser A, Joshi A (2013) From user fees to fee free: the politics of realising universal free basic education in Indonesia. J Dev Stud 49(2):175–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2012.671473

SADC (1997) Protocol on education and training. https://www.sadc.int/files/3813/5292/8362/Protocol_on_Education__Training1997.pdf

SADC (2012) Education & skills development. https://www.sadc.int/themes/social-human-development/education-skills-development/

Salisbury T (2016) Education and inequality in South Africa: returns to schooling in the post-apartheid era. Int J Educ Dev 46:43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.07.004

Southern and Eastern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality (SACMEQ) (2011) SACMEQ III main report, 2011, S55. http://www.sacmeq.org/sites/default/files/sacmeq/reports/sacmeq-iii/national-reports/mal_sacmeq_iii_report-_final.pdf

Spaull N (2013) Poverty & privilege: primary school inequality in South Africa. Int J Educ Dev 33:436–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2012.00.009

Statistics South Africa (2017) Education series volume III. Educational enrolment and achievement, 2016. http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report%2092-01-03/Report%2092-01-032016.pdf

Stromquist NP, Sanyal A (2013) Student resistance to neoliberalism in Chile. Int Stud Sociol Educ 23(2):152–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/09620214.2013.790662

Takayama K, Sriprakash A, Connell R (2016) Toward a postcolonial comparative and international education. Comp Educ Rev 61(S1):S1–S24, 010-4086/2017/61S1-0001

Tooley J, Dixon P (2006) ‘De facto’ privatisation of education and the poor: implications of a study from sub-Saharan Africa and India. Compare 36(4):443–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920601024891

UNESCO (2002) Education for All: is the world on track? EFA global monitoring report. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000129053

UNESCO (2007) Education for all by 2015: will we make it? Global monitoring report. https://www.unicef.org/easterncaribbean/spmapping/Implementation/ECD/2008_EFA_Global_Report.pdf

UNESCO (2014) EFA global monitoring report 2013/4 – Teaching and learning: Achieving quality for all. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000225660

UNESCO (2015) EFA global monitoring report. Education for all 2000–2015: Achievements and challenges. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000232205

UNESCO (2018) Global education monitoring report. Migration, displacement and education: building bridges, not walls. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000265866/PDF/265866eng.pdf.multi

UNESCO Institute of Statistics (2019) Sustainable development goals. Browse by country. http://uis.unesco.org/en/country/id?theme=education-and-literacy

UNESCO TCG (2016) Working group 1: indicator development. Terms of reference. http://tcg.uis.unesco.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2018/08/TCG_WG1_ToR_20170901.pdf

United Nations General Assembly (1966) International covenant on economic, social and cultural rights. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CESCR.aspx

United Nations General Assembly (1989) Convention on the rights of the child. https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx

University of Minnesota (1980) Constitution of the republic of Chile. http://hrlibrary.umn.edu/research/chile-constitution.pdf

University of Oslo (2002) SAARC convention on regional arrangements for the promotion of child welfare in South Asia. https://www.jus.uio.no/english/services/library/treaties/02/2-05/child-welfare-asia.xml

Walton GW (2019) Fee-free education, decentralisation and the politics of scale in Papua New Guinea. J Educ Policy 34(2):174–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2017.1422027

WCEFA (World Conference on Education for All) (1990) World declaration on education for all. http://www.unesco.org/education/pdf/JOMTIE_E.PDF

Webb A, Radcliffe S (2016) Unfulfilled promises of equity: racism and interculturalism in Chilean education. Race Ethn Educ 19(6):1335–1350. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2015.1095173

Zuilkowski SS, Samanhudi U, Indriana I (2019) ‘There is no free education nowadays’: youth explanations for school dropout in Indonesia. Compare 49(1):16–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2017.1369002

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Languages and Literatures (African Language Studies Section), Rhodes University, Grahamstown/Makhanda, South Africa

Michael M. Kretzer

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Michael M. Kretzer .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

European School of Sustainability Science and Research, Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, Hamburg, Germany

Walter Leal Filho

Center for Neuroscience and Cell Biology, Institute for Interdisciplinary Research, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

Anabela Marisa Azul

Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Passo Fundo University, Passo Fundo, Brazil

Luciana Brandli

Istinye University, Istanbul, Turkey

Pinar Gökçin Özuyar

University of Chester, Chester, UK

Section Editor information

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Kretzer, M.M. (2020). Free Education: Origins, Achievements, and Current Situation. In: Leal Filho, W., Azul, A.M., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P.G., Wall, T. (eds) Quality Education. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95870-5_93

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95870-5_93

Published : 04 April 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-95869-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-95870-5

eBook Packages : Earth and Environmental Science Reference Module Physical and Materials Science Reference Module Earth and Environmental Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

RSS feed Facebook Twitter Donate Share -->

- News & blog

- Monitoring guide

- Education as a right

- United Nations

- Humanitarian Law

- International Human Rights Mechanisms

- Inter-American

- Regional Human Rights Mechanisms

- What information to look at

- Where to find information

- Comparative Table on Minimum Age Legislation

- Adult education & learning

- Education 2030

- Education Financing

- Education in Emergencies

- Educational Freedoms

- Early Childhood Care and Education

Free Education

- Higher education

- Technology in education

- Justiciability

- Marginalised Groups

- Minimum Age

- Privatisation of Education

- Quality Education

- News and blog

You are here

Un_523257_classrom_timor.jpg.

According to international human rights law, primary education shall be compulsory and free of charge. Secondary and higher education shall be made progressively free of charge.

Free primary education is fundamental in guaranteeing everyone has access to education. However, in many developing countries, families often cannot afford to send their children to school, leaving millions of children of school-age deprived of education. Despite international obligations, some states keep on imposing fees to access primary education. In addition, there are often indirect costs associated with education, such as for school books, uniform or travel, that prevent children from low-income families accessing school.

Financial difficulties states may face cannot relieve them of their obligation to guarantee free primary education. If a state is unable to secure compulsory primary education, free of charge, when it ratifies the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR, 1966), it still has the immediate obligation, within two years, to work out and adopt a detailed plan of action for its progressive implementation, within a reasonable numbers of years, to be fixed in the plan (ICESCR, Article 14). For more information, see General Comment 11 (1999) of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

'Progressive introduction of free education' means that while states must prioritise the provision of free primary education, they also have an obligation to take concrete steps towards achieving free secondary and higher education ( General Comment 13 of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1999: Para. 14).

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948, Article 26)

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966, Articles 13 and 14)

- Convention on the Rights of the Child (1982, Article 28)

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (1979, Article 10)

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006, Article 24)

- UNESCO Convention against Discrimination in Education (1960, Articles 4)

- ILO Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention (1999, Preamble, Articles 7 and 8)

- African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (1990, Article 11)

- African Youth Charter (2006, Articles 13 and 16)

- Charter of the Organisation of American States (1967, Article 49)

- Additional Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights, Protocol of San Salvador (1988, Article 13)

- Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2000, Article 14)

- European Social Charter (revised) (1996, Articles 10 and 17)

- Arab Charter on Human Rights (2004, Article 41)

- ASEAN Human Rights Declaration (2012, Article 31)

For more details, see International Instruments - Free and Compulsory Education

The following case-law on free education includes decisions of national, regional and international courts as well as decisions from national administrative bodies, national human rights institutions and international human rights bodies.

Claim of unconstitutionality against article 183 of the General Education Law (Colombia Constitutional Court; 2010)

Other issues.

Getting Into College , Is UoPeople Worth it , Paying for School , Tuition Free , Why UoPeople

5 Reasons Why College Should Be Free: The Case for Debt-Free Education

Updated: December 7, 2023

Published: January 30, 2020