- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write the Results/Findings Section in Research

What is the research paper Results section and what does it do?

The Results section of a scientific research paper represents the core findings of a study derived from the methods applied to gather and analyze information. It presents these findings in a logical sequence without bias or interpretation from the author, setting up the reader for later interpretation and evaluation in the Discussion section. A major purpose of the Results section is to break down the data into sentences that show its significance to the research question(s).

The Results section appears third in the section sequence in most scientific papers. It follows the presentation of the Methods and Materials and is presented before the Discussion section —although the Results and Discussion are presented together in many journals. This section answers the basic question “What did you find in your research?”

What is included in the Results section?

The Results section should include the findings of your study and ONLY the findings of your study. The findings include:

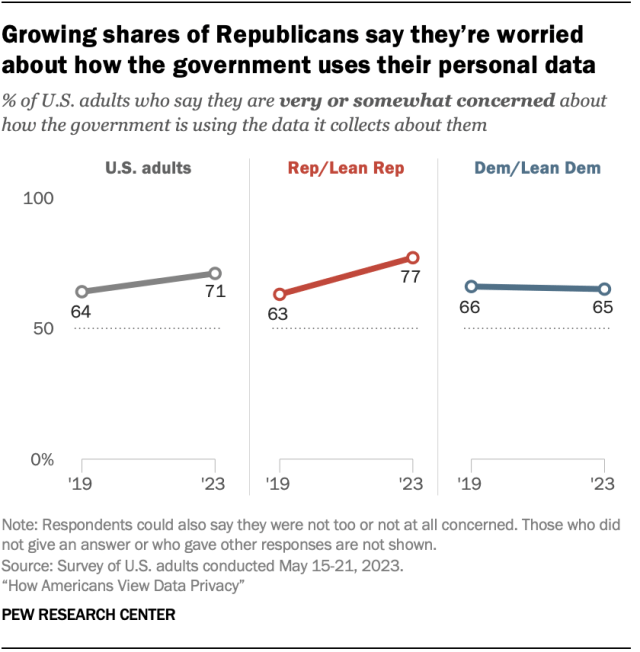

- Data presented in tables, charts, graphs, and other figures (may be placed into the text or on separate pages at the end of the manuscript)

- A contextual analysis of this data explaining its meaning in sentence form

- All data that corresponds to the central research question(s)

- All secondary findings (secondary outcomes, subgroup analyses, etc.)

If the scope of the study is broad, or if you studied a variety of variables, or if the methodology used yields a wide range of different results, the author should present only those results that are most relevant to the research question stated in the Introduction section .

As a general rule, any information that does not present the direct findings or outcome of the study should be left out of this section. Unless the journal requests that authors combine the Results and Discussion sections, explanations and interpretations should be omitted from the Results.

How are the results organized?

The best way to organize your Results section is “logically.” One logical and clear method of organizing research results is to provide them alongside the research questions—within each research question, present the type of data that addresses that research question.

Let’s look at an example. Your research question is based on a survey among patients who were treated at a hospital and received postoperative care. Let’s say your first research question is:

“What do hospital patients over age 55 think about postoperative care?”

This can actually be represented as a heading within your Results section, though it might be presented as a statement rather than a question:

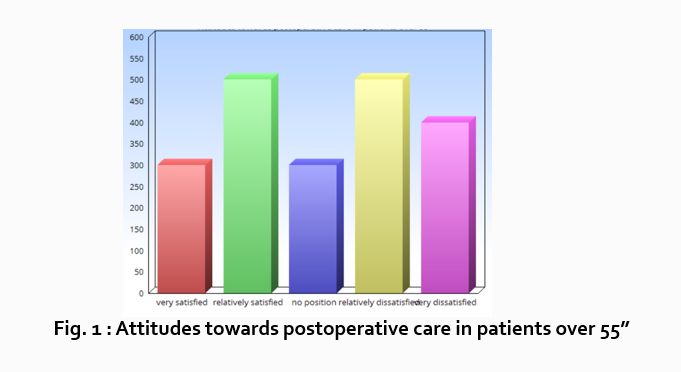

Attitudes towards postoperative care in patients over the age of 55

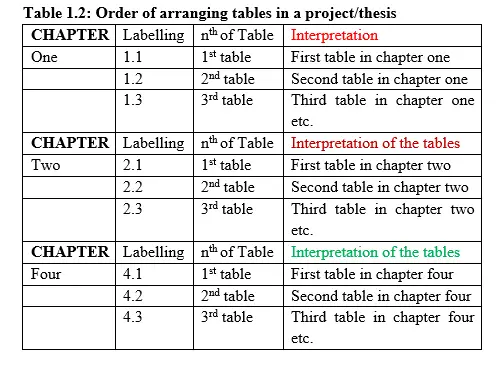

Now present the results that address this specific research question first. In this case, perhaps a table illustrating data from a survey. Likert items can be included in this example. Tables can also present standard deviations, probabilities, correlation matrices, etc.

Following this, present a content analysis, in words, of one end of the spectrum of the survey or data table. In our example case, start with the POSITIVE survey responses regarding postoperative care, using descriptive phrases. For example:

“Sixty-five percent of patients over 55 responded positively to the question “ Are you satisfied with your hospital’s postoperative care ?” (Fig. 2)

Include other results such as subcategory analyses. The amount of textual description used will depend on how much interpretation of tables and figures is necessary and how many examples the reader needs in order to understand the significance of your research findings.

Next, present a content analysis of another part of the spectrum of the same research question, perhaps the NEGATIVE or NEUTRAL responses to the survey. For instance:

“As Figure 1 shows, 15 out of 60 patients in Group A responded negatively to Question 2.”

After you have assessed the data in one figure and explained it sufficiently, move on to your next research question. For example:

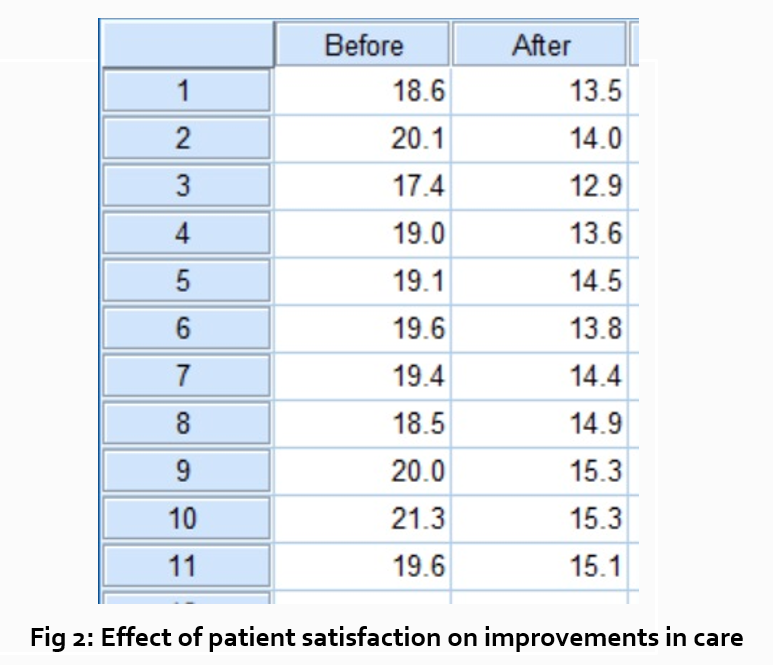

“How does patient satisfaction correspond to in-hospital improvements made to postoperative care?”

This kind of data may be presented through a figure or set of figures (for instance, a paired T-test table).

Explain the data you present, here in a table, with a concise content analysis:

“The p-value for the comparison between the before and after groups of patients was .03% (Fig. 2), indicating that the greater the dissatisfaction among patients, the more frequent the improvements that were made to postoperative care.”

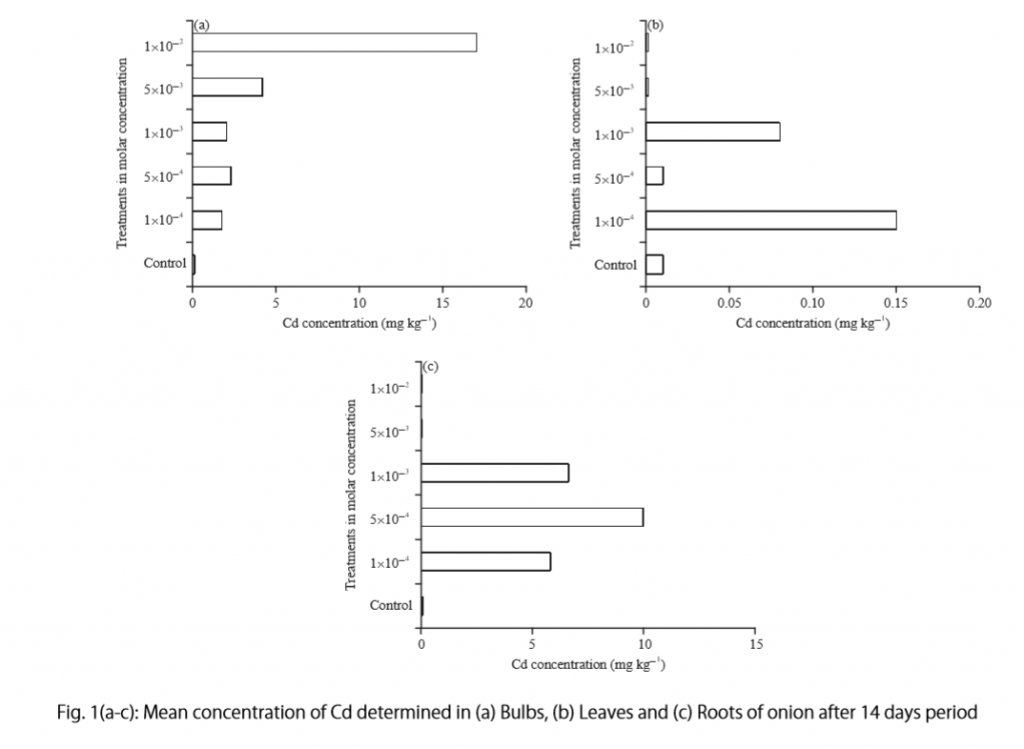

Let’s examine another example of a Results section from a study on plant tolerance to heavy metal stress . In the Introduction section, the aims of the study are presented as “determining the physiological and morphological responses of Allium cepa L. towards increased cadmium toxicity” and “evaluating its potential to accumulate the metal and its associated environmental consequences.” The Results section presents data showing how these aims are achieved in tables alongside a content analysis, beginning with an overview of the findings:

“Cadmium caused inhibition of root and leave elongation, with increasing effects at higher exposure doses (Fig. 1a-c).”

The figure containing this data is cited in parentheses. Note that this author has combined three graphs into one single figure. Separating the data into separate graphs focusing on specific aspects makes it easier for the reader to assess the findings, and consolidating this information into one figure saves space and makes it easy to locate the most relevant results.

Following this overall summary, the relevant data in the tables is broken down into greater detail in text form in the Results section.

- “Results on the bio-accumulation of cadmium were found to be the highest (17.5 mg kgG1) in the bulb, when the concentration of cadmium in the solution was 1×10G2 M and lowest (0.11 mg kgG1) in the leaves when the concentration was 1×10G3 M.”

Captioning and Referencing Tables and Figures

Tables and figures are central components of your Results section and you need to carefully think about the most effective way to use graphs and tables to present your findings . Therefore, it is crucial to know how to write strong figure captions and to refer to them within the text of the Results section.

The most important advice one can give here as well as throughout the paper is to check the requirements and standards of the journal to which you are submitting your work. Every journal has its own design and layout standards, which you can find in the author instructions on the target journal’s website. Perusing a journal’s published articles will also give you an idea of the proper number, size, and complexity of your figures.

Regardless of which format you use, the figures should be placed in the order they are referenced in the Results section and be as clear and easy to understand as possible. If there are multiple variables being considered (within one or more research questions), it can be a good idea to split these up into separate figures. Subsequently, these can be referenced and analyzed under separate headings and paragraphs in the text.

To create a caption, consider the research question being asked and change it into a phrase. For instance, if one question is “Which color did participants choose?”, the caption might be “Color choice by participant group.” Or in our last research paper example, where the question was “What is the concentration of cadmium in different parts of the onion after 14 days?” the caption reads:

“Fig. 1(a-c): Mean concentration of Cd determined in (a) bulbs, (b) leaves, and (c) roots of onions after a 14-day period.”

Steps for Composing the Results Section

Because each study is unique, there is no one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to designing a strategy for structuring and writing the section of a research paper where findings are presented. The content and layout of this section will be determined by the specific area of research, the design of the study and its particular methodologies, and the guidelines of the target journal and its editors. However, the following steps can be used to compose the results of most scientific research studies and are essential for researchers who are new to preparing a manuscript for publication or who need a reminder of how to construct the Results section.

Step 1 : Consult the guidelines or instructions that the target journal or publisher provides authors and read research papers it has published, especially those with similar topics, methods, or results to your study.

- The guidelines will generally outline specific requirements for the results or findings section, and the published articles will provide sound examples of successful approaches.

- Note length limitations on restrictions on content. For instance, while many journals require the Results and Discussion sections to be separate, others do not—qualitative research papers often include results and interpretations in the same section (“Results and Discussion”).

- Reading the aims and scope in the journal’s “ guide for authors ” section and understanding the interests of its readers will be invaluable in preparing to write the Results section.

Step 2 : Consider your research results in relation to the journal’s requirements and catalogue your results.

- Focus on experimental results and other findings that are especially relevant to your research questions and objectives and include them even if they are unexpected or do not support your ideas and hypotheses.

- Catalogue your findings—use subheadings to streamline and clarify your report. This will help you avoid excessive and peripheral details as you write and also help your reader understand and remember your findings. Create appendices that might interest specialists but prove too long or distracting for other readers.

- Decide how you will structure of your results. You might match the order of the research questions and hypotheses to your results, or you could arrange them according to the order presented in the Methods section. A chronological order or even a hierarchy of importance or meaningful grouping of main themes or categories might prove effective. Consider your audience, evidence, and most importantly, the objectives of your research when choosing a structure for presenting your findings.

Step 3 : Design figures and tables to present and illustrate your data.

- Tables and figures should be numbered according to the order in which they are mentioned in the main text of the paper.

- Information in figures should be relatively self-explanatory (with the aid of captions), and their design should include all definitions and other information necessary for readers to understand the findings without reading all of the text.

- Use tables and figures as a focal point to tell a clear and informative story about your research and avoid repeating information. But remember that while figures clarify and enhance the text, they cannot replace it.

Step 4 : Draft your Results section using the findings and figures you have organized.

- The goal is to communicate this complex information as clearly and precisely as possible; precise and compact phrases and sentences are most effective.

- In the opening paragraph of this section, restate your research questions or aims to focus the reader’s attention to what the results are trying to show. It is also a good idea to summarize key findings at the end of this section to create a logical transition to the interpretation and discussion that follows.

- Try to write in the past tense and the active voice to relay the findings since the research has already been done and the agent is usually clear. This will ensure that your explanations are also clear and logical.

- Make sure that any specialized terminology or abbreviation you have used here has been defined and clarified in the Introduction section .

Step 5 : Review your draft; edit and revise until it reports results exactly as you would like to have them reported to your readers.

- Double-check the accuracy and consistency of all the data, as well as all of the visual elements included.

- Read your draft aloud to catch language errors (grammar, spelling, and mechanics), awkward phrases, and missing transitions.

- Ensure that your results are presented in the best order to focus on objectives and prepare readers for interpretations, valuations, and recommendations in the Discussion section . Look back over the paper’s Introduction and background while anticipating the Discussion and Conclusion sections to ensure that the presentation of your results is consistent and effective.

- Consider seeking additional guidance on your paper. Find additional readers to look over your Results section and see if it can be improved in any way. Peers, professors, or qualified experts can provide valuable insights.

One excellent option is to use a professional English proofreading and editing service such as Wordvice, including our paper editing service . With hundreds of qualified editors from dozens of scientific fields, Wordvice has helped thousands of authors revise their manuscripts and get accepted into their target journals. Read more about the proofreading and editing process before proceeding with getting academic editing services and manuscript editing services for your manuscript.

As the representation of your study’s data output, the Results section presents the core information in your research paper. By writing with clarity and conciseness and by highlighting and explaining the crucial findings of their study, authors increase the impact and effectiveness of their research manuscripts.

For more articles and videos on writing your research manuscript, visit Wordvice’s Resources page.

Wordvice Resources

- How to Write a Research Paper Introduction

- Which Verb Tenses to Use in a Research Paper

- How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Research Paper Title

- Useful Phrases for Academic Writing

- Common Transition Terms in Academic Papers

- Active and Passive Voice in Research Papers

- 100+ Verbs That Will Make Your Research Writing Amazing

- Tips for Paraphrasing in Research Papers

- Discoveries

- Right Journal

- Journal Metrics

- Journal Fit

- Abbreviation

- In-Text Citations

- Bibliographies

- Writing an Article

- Peer Review Types

- Acknowledgements

- Withdrawing a Paper

- Form Letter

- ISO, ANSI, CFR

- Google Scholar

- Journal Manuscript Editing

- Research Manuscript Editing

Book Editing

- Manuscript Editing Services

Medical Editing

- Bioscience Editing

- Physical Science Editing

- PhD Thesis Editing Services

- PhD Editing

- Master’s Proofreading

- Bachelor’s Editing

- Dissertation Proofreading Services

- Best Dissertation Proofreaders

- Masters Dissertation Proofreading

- PhD Proofreaders

- Proofreading PhD Thesis Price

- Journal Article Editing

- Book Editing Service

- Editing and Proofreading Services

- Research Paper Editing

- Medical Manuscript Editing

- Academic Editing

- Social Sciences Editing

- Academic Proofreading

- PhD Theses Editing

- Dissertation Proofreading

- Proofreading Rates UK

- Medical Proofreading

- PhD Proofreading Services UK

- Academic Proofreading Services UK

Medical Editing Services

- Life Science Editing

- Biomedical Editing

- Environmental Science Editing

- Pharmaceutical Science Editing

- Economics Editing

- Psychology Editing

- Sociology Editing

- Archaeology Editing

- History Paper Editing

- Anthropology Editing

- Law Paper Editing

- Engineering Paper Editing

- Technical Paper Editing

- Philosophy Editing

- PhD Dissertation Proofreading

- Lektorat Englisch

- Akademisches Lektorat

- Lektorat Englisch Preise

- Wissenschaftliches Lektorat

- Lektorat Doktorarbeit

PhD Thesis Editing

- Thesis Proofreading Services

- PhD Thesis Proofreading

- Proofreading Thesis Cost

- Proofreading Thesis

- Thesis Editing Services

- Professional Thesis Editing

- Thesis Editing Cost

- Proofreading Dissertation

- Dissertation Proofreading Cost

- Dissertation Proofreader

- Correção de Artigos Científicos

- Correção de Trabalhos Academicos

- Serviços de Correção de Inglês

- Correção de Dissertação

- Correção de Textos Precos

- 定額 ネイティブチェック

- Copy Editing

- FREE Courses

- Revision en Ingles

- Revision de Textos en Ingles

- Revision de Tesis

- Revision Medica en Ingles

- Revision de Tesis Precio

- Revisão de Artigos Científicos

- Revisão de Trabalhos Academicos

- Serviços de Revisão de Inglês

- Revisão de Dissertação

- Revisão de Textos Precos

- Corrección de Textos en Ingles

- Corrección de Tesis

- Corrección de Tesis Precio

- Corrección Medica en Ingles

- Corrector ingles

Select Page

How To Write the Findings Section of a Research Paper

Posted by Rene Tetzner | Sep 2, 2021 | Paper Writing Advice | 0 |

How To Write the Findings Section of a Research Paper Each research project is unique, so it is natural for one researcher to make use of somewhat different strategies than another when it comes to designing and writing the section of a research paper dedicated to findings. The academic or scientific discipline of the research, the field of specialisation, the particular author or authors, the targeted journal or other publisher and the editor making the decisions about publication can all have a significant impact. The practical steps outlined below can be effectively applied to writing about the findings of most advanced research, however, and will prove especially helpful for early-career scholars who are preparing a research paper for a first publication.

Step 1 : Consult the guidelines or instructions that the targeted journal (or other publisher) provides for authors and read research papers it has already published, particularly ones similar in topic, methods or results to your own. The guidelines will generally outline specific requirements for the results or findings section, and the published articles will provide sound examples of successful approaches. Watch particularly for length limitations and restrictions on content. Interpretation, for instance, is usually reserved for a later discussion section, though not always – qualitative research papers often combine findings and interpretation. Background information and descriptions of methods, on the other hand, almost always appear in earlier sections of a research paper. In most cases it is appropriate in a findings section to offer basic comparisons between the results of your study and those of other studies, but knowing exactly what the journal wants in the report of research findings is essential. Learning as much as you can about the journal’s aims and scope as well as the interests of its readers is invaluable as well.

Step 2 : Reflect at some length on your research results in relation to the journal’s requirements while planning the findings section of your paper. Choose for particular focus experimental results and other research discoveries that are particularly relevant to your research questions and objectives, and include them even if they are unexpected or do not support your ideas and hypotheses. Streamline and clarify your report, especially if it is long and complex, by using subheadings that will help you avoid excessive and peripheral details as you write and also help your reader understand and remember your findings. Consider appendices for raw data that might interest specialists but prove too long or distracting for other readers. The opening paragraph of a findings section often restates research questions or aims to refocus the reader’s attention, and it is always wise to summarise key findings at the end of the section, providing a smooth intellectual transition to the interpretation and discussion that follows in most research papers. There are many effective ways in which to organise research findings. The structure of your findings section might be determined by your research questions and hypotheses or match the arrangement of your methods section. A chronological order or hierarchy of importance or meaningful grouping of main themes or categories might prove effective. It may be best to present all the relevant findings and then explain them and your analysis of them, or explaining the results of each trial or test immediately after reporting it may render the material clearer and more comprehensible for your readers. Keep your audience, your most important evidence and your research goals in mind.

Step 3 : Design effective visual presentations of your research results to enhance the textual report of your findings. Tables of various styles and figures of all kinds such as graphs, maps and photos are used in reporting research findings, but do check the journal guidelines for instructions on the number of visual aids allowed, any required design elements and the preferred formats for numbering, labelling and placement in the manuscript. As a general rule, tables and figures should be numbered according to first mention in the main text of the paper, and each one should be clearly introduced and explained at least briefly in that text so that readers know what is presented and what they are expected to see in a particular visual element. Tables and figures should also be self-explanatory, however, so their design should include all definitions and other information necessary for a reader to understand the findings you intend to show without returning to your text. If you construct your tables and figures before drafting your findings section, they can serve as focal points to help you tell a clear and informative story about your findings and avoid unnecessary repetition. Some authors will even work on tables and figures before organising the findings section (Step 2), which can be an extremely effective approach, but it is important to remember that the textual report of findings remains primary. Visual aids can clarify and enrich the text, but they cannot take its place.

Step 4 : Write your findings section in a factual and objective manner. The goal is to communicate information – in some cases a great deal of complex information – as clearly, accurately and precisely as possible, so well-constructed sentences that maintain a simple structure will be far more effective than convoluted phrasing and expressions. The active voice is often recommended by publishers and the authors of writing manuals, and the past tense is appropriate because the research has already been done. Make sure your grammar, spelling and punctuation are correct and effective so that you are conveying the meaning you intend. Statements that are vague, imprecise or ambiguous will often confuse and mislead readers, and a verbose style will add little more than padding while wasting valuable words that might be put to far better use in clear and logical explanations. Some specialised terminology may be required when reporting findings, but anything potentially unclear or confusing that has not already been defined earlier in the paper should be clarified for readers, and the same principle applies to unusual or nonstandard abbreviations. Your readers will want to understand what you are reporting about your results, not waste time looking up terms simply to understand what you are saying. A logical approach to organising your findings section (Step 2) will help you tell a logical story about your research results as you explain, highlight, offer analysis and summarise the information necessary for readers to understand the discussion section that follows.

Step 5 : Review the draft of your findings section and edit and revise until it reports your key findings exactly as you would have them presented to your readers. Check for accuracy and consistency in data across the section as a whole and all its visual elements. Read your prose aloud to catch language errors, awkward phrases and abrupt transitions. Ensure that the order in which you have presented results is the best order for focussing readers on your research objectives and preparing them for the interpretations, speculations, recommendations and other elements of the discussion that you are planning. This will involve looking back over the paper’s introductory and background material as well as anticipating the discussion and conclusion sections, and this is precisely the right point in the process for reviewing and reflecting. Your research results have taken considerable time to obtain and analyse, so a little more time to stand back and take in the wider view from the research door you have opened is a wise investment. The opinions of any additional readers you can recruit, whether they are professional mentors and colleagues or family and friends, will often prove invaluable as well.

You might be interested in Services offered by Proof-Reading-Service.com

Journal editing.

Journal article editing services

PhD thesis editing services

Scientific Editing

Manuscript editing.

Manuscript editing services

Expert Editing

Expert editing for all papers

Research Editing

Research paper editing services

Professional book editing services

How To Write the Findings Section of a Research Paper These five steps will help you write a clear & interesting findings section for a research paper

Related Posts

How To Write a Journal Article

September 6, 2021

Tips on How To Write a Journal Article

August 30, 2021

How To Write Highlights for an Academic or Scientific Paper

September 7, 2021

Tips on How To Write an Effective Figure Legend

August 27, 2021

Our Recent Posts

Our review ratings

- Examples of Research Paper Topics in Different Study Areas Score: 98%

- Dealing with Language Problems – Journal Editor’s Feedback Score: 95%

- Making Good Use of a Professional Proofreader Score: 92%

- How To Format Your Journal Paper Using Published Articles Score: 95%

- Journal Rejection as Inspiration for a New Perspective Score: 95%

Explore our Categories

- Abbreviation in Academic Writing (4)

- Career Advice for Academics (5)

- Dealing with Paper Rejection (11)

- Grammar in Academic Writing (5)

- Help with Peer Review (7)

- How To Get Published (146)

- Paper Writing Advice (17)

- Referencing & Bibliographies (16)

From Data to Discovery: The Findings Section of a Research Paper

Discover the role of the findings section of a research paper here. Explore strategies and techniques to maximize your understanding.

Are you curious about the Findings section of a research paper? Did you know that this is a part where all the juicy results and discoveries are laid out for the world to see? Undoubtedly, the findings section of a research paper plays a critical role in presenting and interpreting the collected data. It serves as a comprehensive account of the study’s results and their implications.

Well, look no further because we’ve got you covered! In this article, we’re diving into the ins and outs of presenting and interpreting data in the findings section. We’ll be sharing tips and tricks on how to effectively present your findings, whether it’s through tables, graphs, or good old descriptive statistics.

Overview of the Findings Section of a Research Paper

The findings section of a research paper presents the results and outcomes of the study or investigation. It is a crucial part of the research paper where researchers interpret and analyze the data collected and draw conclusions based on their findings. This section aims to answer the research questions or hypotheses formulated earlier in the paper and provide evidence to support or refute them.

In the findings section, researchers typically present the data clearly and organized. They may use tables, graphs, charts, or other visual aids to illustrate the patterns, trends, or relationships observed in the data. The findings should be presented objectively, without any bias or personal opinions, and should be accompanied by appropriate statistical analyses or methods to ensure the validity and reliability of the results.

Organizing the Findings Section

The findings section of the research paper organizes and presents the results obtained from the study in a clear and logical manner. Here is a suggested structure for organizing the Findings section:

Introduction to the Findings

Start the section by providing a brief overview of the research objectives and the methodology employed. Recapitulate the research questions or hypotheses addressed in the study.

To learn more about methodology, read this article .

Descriptive Statistics and Data Presentation

Present the collected data using appropriate descriptive statistics. This may involve using tables, graphs, charts, or other visual representations to convey the information effectively. Remember: we can easily help you with that.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Perform a thorough analysis of the data collected and describe the key findings. Present the results of statistical analyses or any other relevant methods used to analyze the data.

Discussion of Findings

Analyze and interpret the findings in the context of existing literature or theoretical frameworks . Discuss any patterns, trends, or relationships observed in the data. Compare and contrast the results with prior studies, highlighting similarities and differences.

Limitations and Constraints

Acknowledge and discuss any limitations or constraints that may have influenced the findings. This could include issues such as sample size, data collection methods, or potential biases.

Summarize the main findings of the study and emphasize their significance. Revisit the research questions or hypotheses and discuss whether they have been supported or refuted by the findings.

Presenting Data in the Findings Section

There are several ways to present data in the findings section of a research paper. Here are some common methods:

- Tables : Tables are commonly used to present organized and structured data. They are particularly useful when presenting numerical data with multiple variables or categories. Tables allow readers to easily compare and interpret the information presented. Learn how to cite tables in research papers here .

- Graphs and Charts: Graphs and charts are effective visual tools for presenting data, especially when illustrating trends, patterns, or relationships. Common types include bar graphs, line graphs, scatter plots, pie charts, and histograms. Graphs and charts provide a visual representation of the data, making it easier for readers to comprehend and interpret.

- Figures and Images: Figures and images can be used to present data that requires visual representation, such as maps, diagrams, or experimental setups. They can enhance the understanding of complex data or provide visual evidence to support the research findings.

- Descriptive Statistics: Descriptive statistics provide summary measures of central tendency (e.g., mean, median, mode) and dispersion (e.g., standard deviation, range) for numerical data. These statistics can be included in the text or presented in tables or graphs to provide a concise summary of the data distribution.

How to Effectively Interpret Results

Interpreting the results is a crucial aspect of the findings section in a research paper. It involves analyzing the data collected and drawing meaningful conclusions based on the findings. Following are the guidelines on how to effectively interpret the results.

Step 1 – Begin with a Recap

Start by restating the research questions or hypotheses to provide context for the interpretation. Remind readers of the specific objectives of the study to help them understand the relevance of the findings.

Step 2 – Relate Findings to Research Questions

Clearly articulate how the results address the research questions or hypotheses. Discuss each finding in relation to the original objectives and explain how it contributes to answering the research questions or supporting/refuting the hypotheses.

Step 3 – Compare with Existing Literature

Compare and contrast the findings with previous studies or existing literature. Highlight similarities, differences, or discrepancies between your results and those of other researchers. Discuss any consistencies or contradictions and provide possible explanations for the observed variations.

Step 4 – Consider Limitations and Alternative Explanations

Acknowledge the limitations of the study and discuss how they may have influenced the results. Explore alternative explanations or factors that could potentially account for the findings. Evaluate the robustness of the results in light of the limitations and alternative interpretations.

Step 5 – Discuss Implications and Significance

Highlight any potential applications or areas where further research is needed based on the outcomes of the study.

Step 6 – Address Inconsistencies and Contradictions

If there are any inconsistencies or contradictions in the findings, address them directly. Discuss possible reasons for the discrepancies and consider their implications for the overall interpretation. Be transparent about any uncertainties or unresolved issues.

Step 7 – Be Objective and Data-Driven

Present the interpretation objectively, based on the evidence and data collected. Avoid personal biases or subjective opinions. Use logical reasoning and sound arguments to support your interpretations.

Reporting Statistical Significance

When reporting statistical significance in the findings section of a research paper, it is important to accurately convey the results of statistical analyses and their implications. Here are some guidelines on how to report statistical significance effectively:

- Clearly State the Statistical Test: Begin by clearly stating the specific statistical test or analysis used to determine statistical significance. For example, you might mention that a t-test, chi-square test, ANOVA, correlation analysis, or regression analysis was employed.

- Report the Test Statistic: Provide the value of the test statistic obtained from the analysis. This could be the t-value, F-value, chi-square value, correlation coefficient, or any other relevant statistic depending on the test used.

- State the Degrees of Freedom: Indicate the degrees of freedom associated with the statistical test. Degrees of freedom represent the number of independent pieces of information available for estimating a statistic. For example, in a t-test, degrees of freedom would be mentioned as (df = n1 + n2 – 2) for an independent samples test or (df = N – 2) for a paired samples test.

- Report the p-value: The p-value indicates the probability of obtaining results as extreme or more extreme than the observed results, assuming the null hypothesis is true. Report the p-value associated with the statistical test. For example, p < 0.05 denotes statistical significance at the conventional level of α = 0.05.

- Provide the Conclusion: Based on the p-value obtained, state whether the results are statistically significant or not. If the p-value is less than the predetermined threshold (e.g., p < 0.05), state that the results are statistically significant. If the p-value is greater than the threshold, state that the results are not statistically significant.

- Discuss the Interpretation: After reporting statistical significance, discuss the practical or theoretical implications of the finding. Explain what the significant result means in the context of your research questions or hypotheses. Address the effect size and practical significance of the findings, if applicable.

- Consider Effect Size Measures: Along with statistical significance, it is often important to report effect size measures. Effect size quantifies the magnitude of the relationship or difference observed in the data. Common effect size measures include Cohen’s d, eta-squared, or Pearson’s r. Reporting effect size provides additional meaningful information about the strength of the observed effects.

- Be Accurate and Transparent: Ensure that the reported statistical significance and associated values are accurate. Avoid misinterpreting or misrepresenting the results. Be transparent about the statistical tests conducted, any assumptions made, and potential limitations or caveats that may impact the interpretation of the significant results.

Conclusion of the Findings Section

The conclusion of the findings section in a research paper serves as a summary and synthesis of the key findings and their implications. It is an opportunity to tie together the results, discuss their significance, and address the research objectives. Here are some guidelines on how to write the conclusion of the Findings section:

Summarize the Key Findings

Begin by summarizing the main findings of the study. Provide a concise overview of the significant results, patterns, or relationships that emerged from the data analysis. Highlight the most important findings that directly address the research questions or hypotheses.

Revisit the Research Objectives

Remind the reader of the research objectives stated at the beginning of the paper. Discuss how the findings contribute to achieving those objectives and whether they support or challenge the initial research questions or hypotheses.

Suggest Future Directions

Identify areas for further research or future directions based on the findings. Discuss any unanswered questions, unresolved issues, or new avenues of inquiry that emerged during the study. Propose potential research opportunities that can build upon the current findings.

The Best Scientific Figures to Represent Your Findings

Have you heard of any tool that helps you represent your findings through visuals like graphs, pie charts, and infographics? Well, if you haven’t, then here’s the tool you need to explore – Mind the Graph . It’s the tool that has the best scientific figures to represent your findings. Go, try it now, and make your research findings stand out!

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual communication in science.

Unlock Your Creativity

Create infographics, presentations and other scientifically-accurate designs without hassle — absolutely free for 7 days!

About Sowjanya Pedada

Sowjanya is a passionate writer and an avid reader. She holds MBA in Agribusiness Management and now is working as a content writer. She loves to play with words and hopes to make a difference in the world through her writings. Apart from writing, she is interested in reading fiction novels and doing craftwork. She also loves to travel and explore different cuisines and spend time with her family and friends.

Content tags

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Summary – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Summary – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Summary

Definition:

A research summary is a brief and concise overview of a research project or study that highlights its key findings, main points, and conclusions. It typically includes a description of the research problem, the research methods used, the results obtained, and the implications or significance of the findings. It is often used as a tool to quickly communicate the main findings of a study to other researchers, stakeholders, or decision-makers.

Structure of Research Summary

The Structure of a Research Summary typically include:

- Introduction : This section provides a brief background of the research problem or question, explains the purpose of the study, and outlines the research objectives.

- Methodology : This section explains the research design, methods, and procedures used to conduct the study. It describes the sample size, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques.

- Results : This section presents the main findings of the study, including statistical analysis if applicable. It may include tables, charts, or graphs to visually represent the data.

- Discussion : This section interprets the results and explains their implications. It discusses the significance of the findings, compares them to previous research, and identifies any limitations or future directions for research.

- Conclusion : This section summarizes the main points of the research and provides a conclusion based on the findings. It may also suggest implications for future research or practical applications of the results.

- References : This section lists the sources cited in the research summary, following the appropriate citation style.

How to Write Research Summary

Here are the steps you can follow to write a research summary:

- Read the research article or study thoroughly: To write a summary, you must understand the research article or study you are summarizing. Therefore, read the article or study carefully to understand its purpose, research design, methodology, results, and conclusions.

- Identify the main points : Once you have read the research article or study, identify the main points, key findings, and research question. You can highlight or take notes of the essential points and findings to use as a reference when writing your summary.

- Write the introduction: Start your summary by introducing the research problem, research question, and purpose of the study. Briefly explain why the research is important and its significance.

- Summarize the methodology : In this section, summarize the research design, methods, and procedures used to conduct the study. Explain the sample size, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques.

- Present the results: Summarize the main findings of the study. Use tables, charts, or graphs to visually represent the data if necessary.

- Interpret the results: In this section, interpret the results and explain their implications. Discuss the significance of the findings, compare them to previous research, and identify any limitations or future directions for research.

- Conclude the summary : Summarize the main points of the research and provide a conclusion based on the findings. Suggest implications for future research or practical applications of the results.

- Revise and edit : Once you have written the summary, revise and edit it to ensure that it is clear, concise, and free of errors. Make sure that your summary accurately represents the research article or study.

- Add references: Include a list of references cited in the research summary, following the appropriate citation style.

Example of Research Summary

Here is an example of a research summary:

Title: The Effects of Yoga on Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis

Introduction: This meta-analysis examines the effects of yoga on mental health. The study aimed to investigate whether yoga practice can improve mental health outcomes such as anxiety, depression, stress, and quality of life.

Methodology : The study analyzed data from 14 randomized controlled trials that investigated the effects of yoga on mental health outcomes. The sample included a total of 862 participants. The yoga interventions varied in length and frequency, ranging from four to twelve weeks, with sessions lasting from 45 to 90 minutes.

Results : The meta-analysis found that yoga practice significantly improved mental health outcomes. Participants who practiced yoga showed a significant reduction in anxiety and depression symptoms, as well as stress levels. Quality of life also improved in those who practiced yoga.

Discussion : The findings of this study suggest that yoga can be an effective intervention for improving mental health outcomes. The study supports the growing body of evidence that suggests that yoga can have a positive impact on mental health. Limitations of the study include the variability of the yoga interventions, which may affect the generalizability of the findings.

Conclusion : Overall, the findings of this meta-analysis support the use of yoga as an effective intervention for improving mental health outcomes. Further research is needed to determine the optimal length and frequency of yoga interventions for different populations.

References :

- Cramer, H., Lauche, R., Langhorst, J., Dobos, G., & Berger, B. (2013). Yoga for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depression and anxiety, 30(11), 1068-1083.

- Khalsa, S. B. (2004). Yoga as a therapeutic intervention: a bibliometric analysis of published research studies. Indian journal of physiology and pharmacology, 48(3), 269-285.

- Ross, A., & Thomas, S. (2010). The health benefits of yoga and exercise: a review of comparison studies. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 16(1), 3-12.

Purpose of Research Summary

The purpose of a research summary is to provide a brief overview of a research project or study, including its main points, findings, and conclusions. The summary allows readers to quickly understand the essential aspects of the research without having to read the entire article or study.

Research summaries serve several purposes, including:

- Facilitating comprehension: A research summary allows readers to quickly understand the main points and findings of a research project or study without having to read the entire article or study. This makes it easier for readers to comprehend the research and its significance.

- Communicating research findings: Research summaries are often used to communicate research findings to a wider audience, such as policymakers, practitioners, or the general public. The summary presents the essential aspects of the research in a clear and concise manner, making it easier for non-experts to understand.

- Supporting decision-making: Research summaries can be used to support decision-making processes by providing a summary of the research evidence on a particular topic. This information can be used by policymakers or practitioners to make informed decisions about interventions, programs, or policies.

- Saving time: Research summaries save time for researchers, practitioners, policymakers, and other stakeholders who need to review multiple research studies. Rather than having to read the entire article or study, they can quickly review the summary to determine whether the research is relevant to their needs.

Characteristics of Research Summary

The following are some of the key characteristics of a research summary:

- Concise : A research summary should be brief and to the point, providing a clear and concise overview of the main points of the research.

- Objective : A research summary should be written in an objective tone, presenting the research findings without bias or personal opinion.

- Comprehensive : A research summary should cover all the essential aspects of the research, including the research question, methodology, results, and conclusions.

- Accurate : A research summary should accurately reflect the key findings and conclusions of the research.

- Clear and well-organized: A research summary should be easy to read and understand, with a clear structure and logical flow.

- Relevant : A research summary should focus on the most important and relevant aspects of the research, highlighting the key findings and their implications.

- Audience-specific: A research summary should be tailored to the intended audience, using language and terminology that is appropriate and accessible to the reader.

- Citations : A research summary should include citations to the original research articles or studies, allowing readers to access the full text of the research if desired.

When to write Research Summary

Here are some situations when it may be appropriate to write a research summary:

- Proposal stage: A research summary can be included in a research proposal to provide a brief overview of the research aims, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes.

- Conference presentation: A research summary can be prepared for a conference presentation to summarize the main findings of a study or research project.

- Journal submission: Many academic journals require authors to submit a research summary along with their research article or study. The summary provides a brief overview of the study’s main points, findings, and conclusions and helps readers quickly understand the research.

- Funding application: A research summary can be included in a funding application to provide a brief summary of the research aims, objectives, and expected outcomes.

- Policy brief: A research summary can be prepared as a policy brief to communicate research findings to policymakers or stakeholders in a concise and accessible manner.

Advantages of Research Summary

Research summaries offer several advantages, including:

- Time-saving: A research summary saves time for readers who need to understand the key findings and conclusions of a research project quickly. Rather than reading the entire research article or study, readers can quickly review the summary to determine whether the research is relevant to their needs.

- Clarity and accessibility: A research summary provides a clear and accessible overview of the research project’s main points, making it easier for readers to understand the research without having to be experts in the field.

- Improved comprehension: A research summary helps readers comprehend the research by providing a brief and focused overview of the key findings and conclusions, making it easier to understand the research and its significance.

- Enhanced communication: Research summaries can be used to communicate research findings to a wider audience, such as policymakers, practitioners, or the general public, in a concise and accessible manner.

- Facilitated decision-making: Research summaries can support decision-making processes by providing a summary of the research evidence on a particular topic. Policymakers or practitioners can use this information to make informed decisions about interventions, programs, or policies.

- Increased dissemination: Research summaries can be easily shared and disseminated, allowing research findings to reach a wider audience.

Limitations of Research Summary

Limitations of the Research Summary are as follows:

- Limited scope: Research summaries provide a brief overview of the research project’s main points, findings, and conclusions, which can be limiting. They may not include all the details, nuances, and complexities of the research that readers may need to fully understand the study’s implications.

- Risk of oversimplification: Research summaries can be oversimplified, reducing the complexity of the research and potentially distorting the findings or conclusions.

- Lack of context: Research summaries may not provide sufficient context to fully understand the research findings, such as the research background, methodology, or limitations. This may lead to misunderstandings or misinterpretations of the research.

- Possible bias: Research summaries may be biased if they selectively emphasize certain findings or conclusions over others, potentially distorting the overall picture of the research.

- Format limitations: Research summaries may be constrained by the format or length requirements, making it challenging to fully convey the research’s main points, findings, and conclusions.

- Accessibility: Research summaries may not be accessible to all readers, particularly those with limited literacy skills, visual impairments, or language barriers.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 8. The Discussion

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The purpose of the discussion section is to interpret and describe the significance of your findings in relation to what was already known about the research problem being investigated and to explain any new understanding or insights that emerged as a result of your research. The discussion will always connect to the introduction by way of the research questions or hypotheses you posed and the literature you reviewed, but the discussion does not simply repeat or rearrange the first parts of your paper; the discussion clearly explains how your study advanced the reader's understanding of the research problem from where you left them at the end of your review of prior research.

Annesley, Thomas M. “The Discussion Section: Your Closing Argument.” Clinical Chemistry 56 (November 2010): 1671-1674; Peacock, Matthew. “Communicative Moves in the Discussion Section of Research Articles.” System 30 (December 2002): 479-497.

Importance of a Good Discussion

The discussion section is often considered the most important part of your research paper because it:

- Most effectively demonstrates your ability as a researcher to think critically about an issue, to develop creative solutions to problems based upon a logical synthesis of the findings, and to formulate a deeper, more profound understanding of the research problem under investigation;

- Presents the underlying meaning of your research, notes possible implications in other areas of study, and explores possible improvements that can be made in order to further develop the concerns of your research;

- Highlights the importance of your study and how it can contribute to understanding the research problem within the field of study;

- Presents how the findings from your study revealed and helped fill gaps in the literature that had not been previously exposed or adequately described; and,

- Engages the reader in thinking critically about issues based on an evidence-based interpretation of findings; it is not governed strictly by objective reporting of information.

Annesley Thomas M. “The Discussion Section: Your Closing Argument.” Clinical Chemistry 56 (November 2010): 1671-1674; Bitchener, John and Helen Basturkmen. “Perceptions of the Difficulties of Postgraduate L2 Thesis Students Writing the Discussion Section.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 5 (January 2006): 4-18; Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing an Effective Discussion Section. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Rules

These are the general rules you should adopt when composing your discussion of the results :

- Do not be verbose or repetitive; be concise and make your points clearly

- Avoid the use of jargon or undefined technical language

- Follow a logical stream of thought; in general, interpret and discuss the significance of your findings in the same sequence you described them in your results section [a notable exception is to begin by highlighting an unexpected result or a finding that can grab the reader's attention]

- Use the present verb tense, especially for established facts; however, refer to specific works or prior studies in the past tense

- If needed, use subheadings to help organize your discussion or to categorize your interpretations into themes

II. The Content

The content of the discussion section of your paper most often includes :

- Explanation of results : Comment on whether or not the results were expected for each set of findings; go into greater depth to explain findings that were unexpected or especially profound. If appropriate, note any unusual or unanticipated patterns or trends that emerged from your results and explain their meaning in relation to the research problem.

- References to previous research : Either compare your results with the findings from other studies or use the studies to support a claim. This can include re-visiting key sources already cited in your literature review section, or, save them to cite later in the discussion section if they are more important to compare with your results instead of being a part of the general literature review of prior research used to provide context and background information. Note that you can make this decision to highlight specific studies after you have begun writing the discussion section.

- Deduction : A claim for how the results can be applied more generally. For example, describing lessons learned, proposing recommendations that can help improve a situation, or highlighting best practices.

- Hypothesis : A more general claim or possible conclusion arising from the results [which may be proved or disproved in subsequent research]. This can be framed as new research questions that emerged as a consequence of your analysis.

III. Organization and Structure

Keep the following sequential points in mind as you organize and write the discussion section of your paper:

- Think of your discussion as an inverted pyramid. Organize the discussion from the general to the specific, linking your findings to the literature, then to theory, then to practice [if appropriate].

- Use the same key terms, narrative style, and verb tense [present] that you used when describing the research problem in your introduction.

- Begin by briefly re-stating the research problem you were investigating and answer all of the research questions underpinning the problem that you posed in the introduction.

- Describe the patterns, principles, and relationships shown by each major findings and place them in proper perspective. The sequence of this information is important; first state the answer, then the relevant results, then cite the work of others. If appropriate, refer the reader to a figure or table to help enhance the interpretation of the data [either within the text or as an appendix].

- Regardless of where it's mentioned, a good discussion section includes analysis of any unexpected findings. This part of the discussion should begin with a description of the unanticipated finding, followed by a brief interpretation as to why you believe it appeared and, if necessary, its possible significance in relation to the overall study. If more than one unexpected finding emerged during the study, describe each of them in the order they appeared as you gathered or analyzed the data. As noted, the exception to discussing findings in the same order you described them in the results section would be to begin by highlighting the implications of a particularly unexpected or significant finding that emerged from the study, followed by a discussion of the remaining findings.

- Before concluding the discussion, identify potential limitations and weaknesses if you do not plan to do so in the conclusion of the paper. Comment on their relative importance in relation to your overall interpretation of the results and, if necessary, note how they may affect the validity of your findings. Avoid using an apologetic tone; however, be honest and self-critical [e.g., in retrospect, had you included a particular question in a survey instrument, additional data could have been revealed].

- The discussion section should end with a concise summary of the principal implications of the findings regardless of their significance. Give a brief explanation about why you believe the findings and conclusions of your study are important and how they support broader knowledge or understanding of the research problem. This can be followed by any recommendations for further research. However, do not offer recommendations which could have been easily addressed within the study. This would demonstrate to the reader that you have inadequately examined and interpreted the data.

IV. Overall Objectives

The objectives of your discussion section should include the following: I. Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings

Briefly reiterate the research problem or problems you are investigating and the methods you used to investigate them, then move quickly to describe the major findings of the study. You should write a direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results, usually in one paragraph.

II. Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important

No one has thought as long and hard about your study as you have. Systematically explain the underlying meaning of your findings and state why you believe they are significant. After reading the discussion section, you want the reader to think critically about the results and why they are important. You don’t want to force the reader to go through the paper multiple times to figure out what it all means. If applicable, begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most significant or unanticipated finding first, then systematically review each finding. Otherwise, follow the general order you reported the findings presented in the results section.

III. Relate the Findings to Similar Studies

No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for your research. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps to support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your study differs from other research about the topic. Note that any significant or unanticipated finding is often because there was no prior research to indicate the finding could occur. If there is prior research to indicate this, you need to explain why it was significant or unanticipated. IV. Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings

It is important to remember that the purpose of research in the social sciences is to discover and not to prove . When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations for the study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. This is especially important when describing the discovery of significant or unanticipated findings.

V. Acknowledge the Study’s Limitations

It is far better for you to identify and acknowledge your study’s limitations than to have them pointed out by your professor! Note any unanswered questions or issues your study could not address and describe the generalizability of your results to other situations. If a limitation is applicable to the method chosen to gather information, then describe in detail the problems you encountered and why. VI. Make Suggestions for Further Research

You may choose to conclude the discussion section by making suggestions for further research [as opposed to offering suggestions in the conclusion of your paper]. Although your study can offer important insights about the research problem, this is where you can address other questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or highlight hidden issues that were revealed as a result of conducting your research. You should frame your suggestions by linking the need for further research to the limitations of your study [e.g., in future studies, the survey instrument should include more questions that ask..."] or linking to critical issues revealed from the data that were not considered initially in your research.

NOTE: Besides the literature review section, the preponderance of references to sources is usually found in the discussion section . A few historical references may be helpful for perspective, but most of the references should be relatively recent and included to aid in the interpretation of your results, to support the significance of a finding, and/or to place a finding within a particular context. If a study that you cited does not support your findings, don't ignore it--clearly explain why your research findings differ from theirs.

V. Problems to Avoid

- Do not waste time restating your results . Should you need to remind the reader of a finding to be discussed, use "bridge sentences" that relate the result to the interpretation. An example would be: “In the case of determining available housing to single women with children in rural areas of Texas, the findings suggest that access to good schools is important...," then move on to further explaining this finding and its implications.

- As noted, recommendations for further research can be included in either the discussion or conclusion of your paper, but do not repeat your recommendations in the both sections. Think about the overall narrative flow of your paper to determine where best to locate this information. However, if your findings raise a lot of new questions or issues, consider including suggestions for further research in the discussion section.

- Do not introduce new results in the discussion section. Be wary of mistaking the reiteration of a specific finding for an interpretation because it may confuse the reader. The description of findings [results section] and the interpretation of their significance [discussion section] should be distinct parts of your paper. If you choose to combine the results section and the discussion section into a single narrative, you must be clear in how you report the information discovered and your own interpretation of each finding. This approach is not recommended if you lack experience writing college-level research papers.

- Use of the first person pronoun is generally acceptable. Using first person singular pronouns can help emphasize a point or illustrate a contrasting finding. However, keep in mind that too much use of the first person can actually distract the reader from the main points [i.e., I know you're telling me this--just tell me!].

Analyzing vs. Summarizing. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University; Discussion. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Hess, Dean R. "How to Write an Effective Discussion." Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004); Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing to Writing an Effective Discussion Section. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sauaia, A. et al. "The Anatomy of an Article: The Discussion Section: "How Does the Article I Read Today Change What I Will Recommend to my Patients Tomorrow?” The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 74 (June 2013): 1599-1602; Research Limitations & Future Research . Lund Research Ltd., 2012; Summary: Using it Wisely. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Schafer, Mickey S. Writing the Discussion. Writing in Psychology course syllabus. University of Florida; Yellin, Linda L. A Sociology Writer's Guide . Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2009.

Writing Tip

Don’t Over-Interpret the Results!

Interpretation is a subjective exercise. As such, you should always approach the selection and interpretation of your findings introspectively and to think critically about the possibility of judgmental biases unintentionally entering into discussions about the significance of your work. With this in mind, be careful that you do not read more into the findings than can be supported by the evidence you have gathered. Remember that the data are the data: nothing more, nothing less.

MacCoun, Robert J. "Biases in the Interpretation and Use of Research Results." Annual Review of Psychology 49 (February 1998): 259-287; Ward, Paulet al, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Expertise . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Write Two Results Sections!

One of the most common mistakes that you can make when discussing the results of your study is to present a superficial interpretation of the findings that more or less re-states the results section of your paper. Obviously, you must refer to your results when discussing them, but focus on the interpretation of those results and their significance in relation to the research problem, not the data itself.

Azar, Beth. "Discussing Your Findings." American Psychological Association gradPSYCH Magazine (January 2006).

Yet Another Writing Tip

Avoid Unwarranted Speculation!

The discussion section should remain focused on the findings of your study. For example, if the purpose of your research was to measure the impact of foreign aid on increasing access to education among disadvantaged children in Bangladesh, it would not be appropriate to speculate about how your findings might apply to populations in other countries without drawing from existing studies to support your claim or if analysis of other countries was not a part of your original research design. If you feel compelled to speculate, do so in the form of describing possible implications or explaining possible impacts. Be certain that you clearly identify your comments as speculation or as a suggestion for where further research is needed. Sometimes your professor will encourage you to expand your discussion of the results in this way, while others don’t care what your opinion is beyond your effort to interpret the data in relation to the research problem.

- << Previous: Using Non-Textual Elements

- Next: Limitations of the Study >>

- Last Updated: Apr 18, 2024 12:20 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Communicating Research Findings

- First Online: 03 January 2022

Cite this chapter

- Rob Davidson 5 &

- Chandra Makanjee 6

379 Accesses

Research is a scholarship activity and a collective endeavor, and as such, its finding should be disseminated. Research findings, often called research outputs, can be disseminated in many forms including peer-reviewed journal articles (e.g., original research, case reports, and review articles) and conference presentations (oral and poster presentations). There are many other options, such as book chapters, educational materials, reports of teaching practices, curriculum description, videos, media (newspapers/radio/television), and websites. Irrespective of the approach that is chosen as the mode of communicating, all modes of communication entail some basic organizational aspects of dissemination processes that are common. These are to define research project objectives, map potential target audience(s), relay target messages, define mode of communication/engagement, and create a dissemination plan.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bavdekar, S. B., Vyas, S., & Anand, V. (2017). Creating posters for effective scientific communication. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, 65 (8), 82–88.

PubMed Google Scholar

Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2011). Building theory about theory building: What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 36 (1), 12–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0486

Article Google Scholar

Gopal, A., Redman, M., Cox, D., Foreman, D., Elsey, E., & Fleming, S. (2017). Academic poster design at a national conference: A need for standardised guidance? The Clinical Teacher, 14 (5), 360–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12584

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Hoffman, T., Bennett, S., & Del Mar, C. (2017). Evidence-based practice across the health professions, ISBN: 9780729586078 . Elsevier.

Google Scholar

Iny, D. (2012). Four proven strategies for finding a wider audience for your content . Rainmaker Digital. http://www.copyblogger.com/targeted-content-marketing . Accessed January 2021.

Mir, R., Willmott, H., & Greenwood, M. The routledge companion to philosophy in organization studies (pp. 113–124). Routledge.

Myers, M. D. (2013). Qualitative research in business & management (2nd ed.). Sage.

Myers, M. D. (2018). Writing for different audiences. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Business and Management Research Methods (pp. 532–545). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526430212.n31

Chapter Google Scholar

Nikolian, V. C., & Ibrahim, A. M. (2017). What does the future hold for scientific journals? Visual abstracts and other tools for communicating research. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery, 30 (4), 252–258. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1604253

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ranse, J., & Hayes, C. (2009). A novice’s guide to preparing and presenting an oral presentation at a scientific conference. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine, 7 (1). https://doi.org/10.33151/ajp.7.1.151

Rowe, N., & Ilic, D. (2015). Rethinking poster presentations at large-scale scientific meetings—Is it time for the format to evolve? FEBS Journal, 282 , 3661–3668

Richardson, L., & St. Pierre, E. A. (2005). Writing: A method of inquiry. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 959–978). Sage.

Tress, G., Tress, B., & Saunders, D. A. (2014). How to write a paper for successful publication in an international peer-reviewed journal. Pacific Conservation Biology, 20 (1), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1071/PC140017

Verde Arregoitia, L. D., & González-Suárez, M. (2019). From conference abstract to publication in the conservation science literature. Conservation Biology, 33 (5), 1164–1173. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13296

Wellstead, G., Whitehurst, K., Gundogan, B., & Agha, R. (2017). How to deliver an oral presentation. International Journal of Surgery Oncology, 2 (6), e25. https://doi.org/10.1097/IJ9.0000000000000025

Woolston, C. (2016). Conference presentations: Lead the poster parade. Nature, 536 (7614), 115–117

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Health Science, Faculty of Health, University of Canberra, Canberra, Australia

Rob Davidson

Discipline of Medical Radiation Science, Faculty of Health, University of Canberra, Canberra, Australia

Chandra Makanjee

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Chandra Makanjee .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Medical Imaging, Faculty of Health, University of Canberra, Burnaby, BC, Canada

Euclid Seeram

Faculty of Health, University of Canberra, Canberra, ACT, Australia

Robert Davidson

Brookfield Health Sciences, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland

Andrew England

Mark F. McEntee

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter