What you need to know about literacy

What is the global situation in relation to literacy.

Great progress has been made in literacy with most recent data (UNESCO Institute for Statistics) showing that more than 86 per cent of the world’s population know how to read and write compared to 68 per cent in 1979. Despite this, worldwide at least 763 million adults still cannot read and write, two thirds of them women, and 250 million children are failing to acquire basic literacy skills. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused the worst disruption to education in a century, 617 million children and teenagers had not reached minimum reading levels.

How does UNESCO define literacy?

Acquiring literacy is not a one-off act. Beyond its conventional concept as a set of reading, writing and counting skills, literacy is now understood as a means of identification, understanding, interpretation, creation, and communication in an increasingly digital, text-mediated, information-rich and fast-changing world. Literacy is a continuum of learning and proficiency in reading, writing and using numbers throughout life and is part of a larger set of skills, which include digital skills, media literacy, education for sustainable development and global citizenship as well as job-specific skills. Literacy skills themselves are expanding and evolving as people engage more and more with information and learning through digital technology.

What are the effects of literacy?

Literacy empowers and liberates people. Beyond its importance as part of the right to education, literacy improves lives by expanding capabilities which in turn reduces poverty, increases participation in the labour market and has positive effects on health and sustainable development. Women empowered by literacy have a positive ripple effect on all aspects of development. They have greater life choices for themselves and an immediate impact on the health and education of their families, and in particular, the education of girl children.

How does UNESCO work to promote literacy?

UNESCO works through its global network, field offices and institutes and with its Member States and partners to advance literacy in the framework of lifelong learning, and address the literacy target 4.6 in SDG4 and the Education 2030 Framework for Action . Its Strategy for Youth and Adult Literacy (2020-2025) pays special attention to the member countries of the Global Alliance for Literacy which targets 20 countries with an adult literacy rate below 50 per cent and the E9 countries, of which 17 are in Africa. The focus is on promoting literacy in formal and non-formal settings with four priority areas: strengthening national strategies and policy development on literacy; addressing the needs of disadvantaged groups, particularly women and girls; using digital technologies to expand and improve learning outcomes; and monitoring progress and assessing literacy skills. UNESCO also promotes adult learning and education through its Institute for Lifelong Learning , including the implementation of the 2015 Recommendation on Adult Learning and Education and its monitoring through the Global Report on Adult Learning and Education.

What is digital literacy and why is it important?

UNESCO defines digital literacy as the ability to access, manage, understand, integrate, communicate, evaluate and create information safely and appropriately through digital technologies for employment, decent jobs and entrepreneurship. It includes skills such as computer literacy, ICT literacy, information literacy and media literacy which aim to empower people, and in particular youth, to adopt a critical mindset when engaging with information and digital technologies, and to build their resilience in the face of disinformation, hate speech and violent extremism.

How is UNESCO helping advance girls' and women's literacy?

UNESCO’s Global Partnership for Women and Girls Education, launched in 2011, emphasizes quality education for girls and women at the secondary level and in the area of literacy; its Literacy Initiative for Empowerment (LIFE) project (2005–15) targeted women; and UNESCO’s international literacy prizes regularly highlight the life-changing power of meeting women’s and girls’ needs for literacy in specific contexts. Literacy acquisition often brings with it positive change in relation to harmful traditional practices, forms of marginalization and deprivation. Girls’ and women’s literacy seen as lifelong learning is integral to achieving the aims of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

How has youth and adult literacy been impacted in times of COVID-19?

Since the start of the pandemic, several surveys have been conducted but very little is still known about the effect on youth and adult literacy of massive disruptions to learning, growing inequalities and projected increases in school dropouts. To fill this gap UNESCO will conduct a global survey “Learning from the COVID-19 crisis to write the future: National policies and programmes for youth and adult literacy” collecting information from countries worldwide regarding the situation and policy and programme responses. Its results will help UNESCO, countries and other partners respond better to the recovery phase and advance progress towards achieving Sustainable Development Goal 4 on education and its target 4.6 on youth and adult literacy. In addition, for International Literacy Day 2020, UNESCO prepared a background paper on the impact of the crisis on youth and adult literacy.

What is the purpose of the Literacy Prize and Literacy Day?

Every year since 1967, UNESCO celebrates International Literacy Day and rewards outstanding and innovative programmes that promote literacy through the International Literacy Prizes. Every year on 8 September UNESCO comes together for the annual celebration with Field Offices, institutes, NGOs, teachers, learners and partners to remind the world of the importance of literacy as a matter of dignity and human rights. The event emphasizes the power of literacy and creates awareness to advance the global agenda towards a more literate and sustainable society.

The International Literacy Prizes reward excellence and innovation in the field of literacy and, so far, over 506 projects and programmes undertaken by governments, non-governmental organizations and individuals around the world have been recognized. Following an annual call for submissions, an International Jury of experts appointed by UNESCO's Director-General recommends potential prizewinning programmes. Candidates are submitted by Member States or by international non-governmental organizations in official partnership with UNESCO.

Related items

- Lifelong education

Chapter 1. What is Literacy? Multiple Perspectives on Literacy

Constance Beecher

“Once you learn to read, you will be forever free.” – Frederick Douglass

Download Tar Beach – Faith Ringgold Video Transcript [DOC]

Keywords: literacy, digital literacy, critical literacy, community-based literacies

Definitions of literacy from multiple perspectives

Literacy is the cornerstone of education by any definition. Literacy refers to the ability of people to read and write (UNESCO, 2017). Reading and writing in turn are about encoding and decoding information between written symbols and sound (Resnick, 1983; Tyner, 1998). More specifically, literacy is the ability to understand the relationship between sounds and written words such that one may read, say, and understand them (UNESCO, 2004; Vlieghe, 2015). About 67 percent of children nationwide, and more than 80 percent of those from families with low incomes, are not proficient readers by the end of third grade ( The Nation Assessment for Educational Progress; NAEP 2022 ). Children who are not reading on grade level by third grade are 4 times more likely to drop out of school than their peers who are reading on grade level. A large body of research clearly demonstrates that Americans with fewer years of education have poorer health and shorter lives. In fact, since the 1990s, life expectancy has fallen for people without a high school education. Completing more years of education creates better access to health insurance, medical care, and the resources for living a healthier life (Saha, 2006). Americans with less education face higher rates of illness, higher rates of disability, and shorter life expectancies. In the U.S., 25-year-olds without a high school diploma can expect to die 9 years sooner than college graduates. For example, by 2011, the prevalence of diabetes had reached 15% for adults without a high -school education, compared with 7% for college graduates (Zimmerman et al., 2018).

Thus, literacy is a goal of utmost importance to society. But what does it mean to be literate, or to be able to read? What counts as literacy?

Learning Objectives

- Describe two or more definitions of literacy and the differences between them.

- Define digital and critical literacy.

- Distinguish between digital literacy, critical literacy, and community-based literacies.

- Explain multiple perspectives on literacy.

Here are some definitions to consider:

“Literacy is the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate, and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts. Literacy involves a continuum of learning in enabling individuals to achieve their goals, to develop their knowledge and potential, and to participate fully in their community and wider society.” – United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)

“The ability to understand, use, and respond appropriately to written texts.” – National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), citing the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC)

“An individual’s ability to read, write, and speak in English, compute, and solve problems, at levels of proficiency necessary to function on the job, in the family of the individual, and in society.” – Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), Section 203

“The ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate, and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts. Literacy involves a continuum of learning in enabling individuals to achieve their goals, to develop their knowledge and potential, and to participate fully in their community and wider society.” – Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), as cited by the American Library Association’s Committee on Literacy

“Using printed and written information to function in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.” – Kutner, Greenberg, Jin, Boyle, Hsu, & Dunleavy (2007). Literacy in Everyday Life: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2007-480)

Which one of these above definitions resonates with you? Why?

New literacy practices as meaning-making practices

In the 21 st century, literacy increasingly includes understanding the roles of digital media and technology in literacy. In 1996, the New London Group coined the term “multiliteracies” or “new literacies” to describe a modern view of literacy that reflected multiple communication forms and contexts of cultural and linguistic diversity within a globalized society. They defined multiliteracies as a combination of multiple ways of communicating and making meaning, including such modes as visual, audio, spatial, behavioral, and gestural (New London Group, 1996). Most of the text’s students come across today are digital (like this textbook!). Instead of books and magazines, students are reading blogs and text messages.

For a short video on the importance of digital literacy, watch The New Media Literacies .

The National Council for Teachers of English (NCTE, 2019) makes it clear that our definitions of literacy must continue to evolve and grow ( NCTE definition of digital literacy ).

“Literacy has always been a collection of communicative and sociocultural practices shared among communities. As society and technology change, so does literacy. The world demands that a literate person possess and intentionally apply a wide range of skills, competencies, and dispositions. These literacies are interconnected, dynamic, and malleable. As in the past, they are inextricably linked with histories, narratives, life possibilities, and social trajectories of all individuals and groups. Active, successful participants in a global society must be able to:

- participate effectively and critically in a networked world.

- explore and engage critically and thoughtfully across a wide variety of inclusive texts and tools/modalities.

- consume, curate, and create actively across contexts.

- advocate for equitable access to and accessibility of texts, tools, and information.

- build and sustain intentional global and cross-cultural connections and relationships with others to pose and solve problems collaboratively and strengthen independent thought.

- promote culturally sustaining communication and recognize the bias and privilege present in the interactions.

- examine the rights, responsibilities, and ethical implications of the use and creation of information.

- determine how and to what extent texts and tools amplify one’s own and others’ narratives as well as counterproductive narratives.

- recognize and honor the multilingual literacy identities and culture experiences individuals bring to learning environments, and provide opportunities to promote, amplify, and encourage these variations of language (e.g., dialect, jargon, and register).”

In other words, literacy is not just the ability to read and write. It is also being able to effectively use digital technology to find and analyze information. Students who are digitally literate know how to do research, find reliable sources, and make judgments about what they read online and in print. Next, we will learn more about digital literacy.

- Malleable : can be changed.

- Culturally sustaining : the pedagogical preservation of the cultural and linguistic competence of young people pertaining to their communities of origin while simultaneously affording dominant-culture competence.

- Bias : a tendency to believe that some people, ideas, etc., are better than others, usually resulting in unfair treatment.

- Privilege : a right or benefit that is given to some people and not to others.

- Unproductive narrative : negative commonly held beliefs such as “all students from low-income backgrounds will struggle in school.” (Narratives are phrases or ideas that are repeated over and over and become “shared narratives.” You can spot them in common expressions and stories that almost everyone knows and holds as ingrained values or beliefs.)

Literacy in the digital age

The Iowa Core recognizes that today, literacy includes technology. The goal for students who graduate from the public education system in Iowa is:

“Each Iowa student will be empowered with the technological knowledge and skills to learn effectively and live productively. This vision, developed by the Iowa Core 21st Century Skills Committee, reflects the fact that Iowans in the 21st century live in a global environment marked by a high use of technology, giving citizens and workers the ability to collaborate and make individual contributions as never before. Iowa’s students live in a media-suffused environment, marked by access to an abundance of information and rapidly changing technological tools useful for critical thinking and problem-solving processes. Therefore, technological literacy supports preparation of students as global citizens capable of self-directed learning in preparation for an ever-changing world” (Iowa Core Standards 21 st Century Skills, n.d.).

NOTE: The essential concepts and skills of technology literacy are taken from the International Society for Technology in Education’s National Educational Technology Standards for Students: Grades K-2 | Technology Literacy Standards

Literacy in any context is defined as the ability “ to access, manage, integrate, evaluate, and create information in order to function in a knowledge society” (ICT Literacy Panel, 2002). “ When we teach only for facts (specifics)… rather than for how to go beyond facts, we teach students how to get out of date ” (Sternberg, 2008). This statement is particularly significant when applied to technology literacy. The Iowa essential concepts for technology literacy reflect broad, universal processes and skills.

Unlike the previous generations, learning in the digital age is marked using rapidly evolving technology, a deluge of information, and a highly networked global community (Dede, 2010). In such a dynamic environment, learners need skills beyond the basic cognitive ability to consume and process language. To understand the characteristics of the digital age, and what this means for how people learn in this new and changing landscape, one may turn to the evolving discussion of literacy or, as one might say now, of digital literacy. The history of literacy contextualizes digital literacy and illustrates changes in literacy over time. By looking at literacy as an evolving historical phenomenon, we can glean the fundamental characteristics of the digital age. These characteristics in turn illuminate the skills needed to take advantage of digital environments. The following discussion is an overview of digital literacy, its essential components, and why it is important for learning in the digital age.

Literacy is often considered a skill or competency. Children and adults alike can spend years developing the appropriate skills for encoding and decoding information. Over the course of thousands of years, literacy has become much more common and widespread, with a global literacy rate ranging from 81% to 90% depending on age and gender (UNESCO, 2016). From a time when literacy was the domain of an elite few, it has grown to include huge swaths of the global population. There are several reasons for this, not the least of which are some of the advantages the written word can provide. Kaestle (1985) tells us that “literacy makes it possible to preserve information as a snapshot in time, allows for recording, tracking and remembering information, and sharing information more easily across distances among others” (p. 16). In short, literacy led “to the replacement of myth by history and the replacement of magic by skepticism and science.”

If literacy involves the skills of reading and writing, digital literacy requires the ability to extend those skills to effectively take advantage of the digital world (American Library Association [ALA], 2013). More general definitions express digital literacy as the ability to read and understand information from digital sources as well as to create information in various digital formats (Bawden, 2008; Gilster, 1997; Tyner, 1998; UNESCO, 2004). Developing digital skills allows digital learners to manage a vast array of rapidly changing information and is key to both learning and working in the evolving digital landscape (Dede, 2010; Koltay, 2011; Mohammadyari & Singh, 2015). As such, it is important for people to develop certain competencies specifically for handling digital content.

ALA Digital Literacy Framework

To fully understand the many digital literacies, we will look at the American Library Association (ALA) framework. The ALA framework is laid out in terms of basic functions with enough specificity to make it easy to understand and remember but broad enough to cover a wide range of skills. The ALA framework includes the following areas:

- understanding,

- evaluating,

- creating, and

- communicating (American Library Association, 2013).

Finding information in a digital environment represents a significant departure from the way human beings have searched for information for centuries. The learner must abandon older linear or sequential approaches to finding information such as reading a book, using a card catalog, index, or table of contents, and instead use more horizontal approaches like natural language searches, hypermedia text, keywords, search engines, online databases and so on (Dede, 2010; Eshet, 2002). The shift involves developing the ability to create meaningful search limits (SCONUL, 2016). Previously, finding the information would have meant simply looking up page numbers based on an index or sorting through a card catalog. Although finding information may depend to some degree on the search tool being used (library, internet search engine, online database, etc.) the search results also depend on how well a person is able to generate appropriate keywords and construct useful Boolean searches. Failure in these two areas could easily return too many results to be helpful, vague, or generic results, or potentially no useful results at all (Hangen, 2015).

Part of the challenge of finding information is the ability to manage the results. Because there is so much data, changing so quickly, in so many different formats, it can be challenging to organize and store them in such a way as to be useful. SCONUL (2016) talks about this as the ability to organize, store, manage, and cite digital resources, while the Educational Testing Service also specifically mentions the skills of accessing and managing information. Some ways to accomplish these tasks is using social bookmarking tools such as Diigo, clipping and organizing software such as Evernote and OneNote, and bibliographic software. Many sites, such as YouTube, allow individuals with an account to bookmark videos, as well as create channels or collections of videos for specific topics or uses. Other websites have similar features.

Understanding

Understanding in the context of digital literacy perhaps most closely resembles traditional literacy because it is the ability to read and interpret text (Jones-Kavalier & Flannigan, 2006). In the digital age, however, the ability to read and understand extends much further than text alone. For example, searches may return results with any combination of text, video, sound, and audio, as well as still and moving pictures. As the internet has evolved, a whole host of visual languages have also evolved, such as moving images, emoticons, icons, data visualizations, videos, and combinations of all the above. Lankshear & Knoble (2008) refer to these modes of communication as “post typographic textual practice.” Understanding the variety of modes of digital material may also be referred to as multimedia literacy (Jones-Kavalier & Flannigan, 2006), visual literacy (Tyner, 1998), or digital literacy (Buckingham, 2006).

Evaluating digital media requires competencies ranging from assessing the importance of a piece of information to determining its accuracy and source. Evaluating information is not new to the digital age, but the nature of digital information can make it more difficult to understand who the source of information is and whether it can be trusted (Jenkins, 2018). When there are abundant and rapidly changing data across heavily populated networks, anyone with access can generate information online. This results in the learner needing to make decisions about its authenticity, trustworthiness, relevance, and significance. Learning evaluative digital skills means learning to ask questions about who is writing the information, why they are writing it, and who the intended audience is (Buckingham, 2006). Developing critical thinking skills is part of the literacy of evaluating and assessing the suitability for use of a specific piece of information (SCONUL, 2016).

Creating in the digital world makes the production of knowledge and ideas in digital formats explicit. While writing is a critical component of traditional literacy, it is not the only creative tool in the digital toolbox. Other tools are available and include creative activities such as podcasting, making audio-visual presentations, building data visualizations, 3D printing, and writing blogs. Tools that haven’t been thought of before are constantly appearing. In short, a digitally literate individual will want to be able to use all formats in which digital information may be conveyed in the creation of a product. A key component of creating with digital tools is understanding what constitutes fair use and what is considered plagiarism. While this is not new to the digital age, it may be more challenging these days to find the line between copying and extending someone else’s work.

In part, the reason for the increased difficulty in discerning between plagiarism and new work is the “cut and paste culture” of the Internet, referred to as “reproduction literacy” (Eshet 2002, p.4), or appropriation in Jenkins’ New Media Literacies (Jenkins, 2018). The question is, what kind and how much change is required to avoid the accusation of plagiarism? This skill requires the ability to think critically, evaluate a work, and make appropriate decisions. There are tools and information to help understand and find those answers, such as the Creative Commons. Learning about such resources and how to use them is part of digital literacy.

Communicating

Communicating is the final category of digital skills in the ALA digital framework. The capacity to connect with individuals all over the world creates unique opportunities for learning and sharing information, for which developing digital communication skills is vital. Some of the skills required for communicating in the digital environment include digital citizenship, collaboration, and cultural awareness. This is not to say that one does not need to develop communication skills outside of the digital environment, but that the skills required for digital communication go beyond what is required in a non-digital environment. Most of us are adept at personal, face- to-face communication, but digital communication needs the ability to engage in asynchronous environments such as email, online forums, blogs, social media, and learning platforms where what is written may not be deleted and may be misinterpreted. Add that to an environment where people number in the millions and the opportunities for misunderstanding and cultural miscues are likely.

The communication category of digital literacies covers an extensive array of skills above and beyond what one might need for face-to-face interactions. It is comprised of competencies around ethical and moral behavior, responsible communication for engagement in social and civic activities (Adam Becker et al., 2017), an awareness of audience, and an ability to evaluate the potential impact of one’s online actions. It also includes skills for handling privacy and security in online environments. These activities fall into two main categories: digital citizenship and collaboration.

Digital citizenship refers to one’s ability to interact effectively in the digital world. Part of this skill is good manners, often referred to as “netiquette.” There is a level of context which is often missing in digital communication due to physical distance, lack of personal familiarity with the people online, and the sheer volume of the people who may encounter our words. People who know us well may understand exactly what we mean when we say something sarcastic or ironic, but people online do not know us, and vocal and facial cues are missing in most digital communication, making it more likely we will be misunderstood. Furthermore, we are more likely to misunderstand or be misunderstood if we are unaware of cultural differences. So, digital citizenship includes an awareness of who we are, what we intend to say, and how it might be perceived by other people we do not know (Buckingham, 2006). It is also a process of learning to communicate clearly in ways that help others understand what we mean.

Another key digital skill is collaboration, and it is essential for effective participation in digital projects via the Internet. The Internet allows people to engage with others they may never see in person and work towards common goals, be they social, civic, or business oriented. Creating a community and working together requires a degree of trust and familiarity that can be difficult to build when there is physical distance between the participants. Greater effort must be made to be inclusive , and to overcome perceived or actual distance and disconnectedness. So, while the potential of digital technology for connecting people is impressive, it is not automatic or effortless, and it requires new skills.

Literacy narratives are stories about reading or composing a message in any form or context. They often include poignant memories that involve a personal experience with literacy. Digital literacy narratives can sometimes be categorized as ones that focus on how the writer came to understand the importance of technology in their life or pedagogy. More often, they are simply narratives that use a medium beyond the print-based essay to tell the story:

Create your own literacy narrative that tells of a significant experience you had with digital literacy. Use a multi-modal tool that includes audio and images or video. Share it with your classmates and discuss the most important ideas you notice in each other’s narratives.

Critical literacy

Literacy scholars recognize that although literacy is a cognitive skill, it is also a set of practices that communities and people participate in. Next, we turn to another perspective on literacy – critical literacy. “Critical” here is not meant as having a negative point of view, but rather using an analytic lens that detects power, privilege, and representation to understand different ways of looking at texts. For example, when groups or individuals stage a protest, do the media refer to them as “protesters” or “rioters?” What is the reason for choosing the label they do, and what are the consequences?

Critical literacy does not have a set definition or typical history of use, but the following key tenets have been described in the literature, which will vary in their application based on the individual social context (Vasquez, 2019). Table 1 presents some key aspects of critical literacy, but this area of literacy research is growing and evolving rapidly, so this is not an exhaustive list.

An important component of critical literacy is the adoption of culturally responsive and sustaining pedagogy. One definition comes from Dr. Django Paris (2012), who stated that Culturally Responsive-Sustaining (CR-S) education recognizes that cultural differences (including racial, ethnic, linguistic, gender, sexuality, and ability ones) should be treated as assets for teaching and learning. Culturally sustaining pedagogy requires teachers to support multilingualism and multiculturalism in their practice. That is, culturally sustaining pedagogy seeks to perpetuate and foster—to sustain—linguistic, literary, and cultural pluralism as part of the democratic project of schooling.

For more, see the Culturally Responsive and Sustaining F ramework . The framework helps educators to think about how to create student-centered learning environments that uphold racial, linguistic, and cultural identities. It prepares students for rigorous independent learning, develops their abilities to connect across lines of difference, elevates historically marginalized voices, and empowers them as agents of social change. CR-S education explores the relationships between historical and contemporary conditions of inequality and the ideas that shape access, participation, and outcomes for learners.

- What can you do to learn more about your students’ cultures?

- How can you build and sustain relationships with your students?

- How do the instructional materials you use affirm your students’ identities?

Community-based literacies

You may have noticed that communities are a big part of critical literacy – we understand that our environment and culture impact what we read and how we understand the world. Now think about the possible differences among three Iowa communities: a neighborhood in the middle of Des Moines, the rural community of New Hartford, and Coralville, a suburb of Iowa City:

You may not have thought about how living in a certain community might contribute to or take away from a child’s ability to learn to read. Dr. Susan Neuman (2001) did. She and her team investigated the differences between two neighborhoods regarding how much access to books and other reading materials children in those neighborhoods had. One middle-to-upper class neighborhood in Philadelphia had large bookstores, toy stores with educational materials, and well-resourced libraries. The other, a low-income neighborhood, had no bookstores or toy stores. There was a library, but it had fewer resources and served a larger number of patrons. In fact, the team found that even the signs on the businesses were harder to read, and there was less environmental printed word. Their findings showed that each child in the middle-class neighborhood had 13 books on average, while in the lower-class neighborhood there was one book per 300 children .

Dr. Neuman and her team (2019) recently revisited this question. This time, they looked at low-income neighborhoods – those where 60% or more of the people are living in poverty . They compared these to borderline neighborhoods – those with 20-40% in poverty – in three cities, Washington, D.C., Detroit, and Los Angeles. Again, they found significantly fewer books in the very low-income areas. The chart represents the preschool books available for sale in each neighborhood. Note that in the lower-income neighborhood of Washington D.C., there were no books for young children to be found at all!

Now watch this video from Campaign for Grade Level Reading. Access to books is one way that children can have new experiences, but it is not the only way!

What is the “summer slide,” and how does it contribute to the differences in children’s reading abilities?

The importance of being literate and how to get there

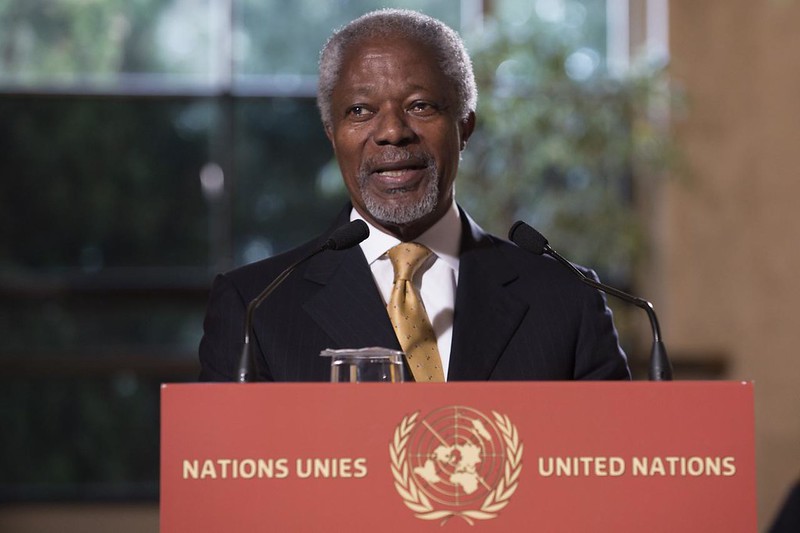

“Literacy is a bridge from misery to hope” – Kofi Annan, former United Nations Secretary-General.

Our economy is enhanced when citizens have higher literacy levels. Effective literacy skills open the doors to more educational and employment opportunities so that people can lift themselves out of poverty and chronic underemployment. In our increasingly complex and rapidly changing technological world, it is essential that individuals continuously expand their knowledge and learn new skills to keep up with the pace of change. The goal of our public school system in the United States is to “ensure that all students graduate from high school with the skills and knowledge necessary to succeed in college, career, and life, regardless of where they live.” This is the basis of the Common Core Standards, developed by the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) and the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGA Center). These groups felt that education was too inconsistent across the different states, and today’s students are preparing to enter a world in which colleges and businesses are demanding more than ever before. To ensure that all students are ready for success after high school, the Common Core State Standards established clear universal guidelines for what every student should know and be able to do in math and English language arts from kindergarten through 12th grade: “The Common Core State Standards do not tell teachers how to teach, but they do help teachers figure out the knowledge and skills their students should have” (Common Core State Standards Initiative, 2012).

Explore the Core!

Go to iowacore.gov and click on Literacy Standards. Spend some time looking at the K-3 standards. Notice how consistent they are across the grade levels. Each has specific requirements within the categories:

- Reading Standards for Literature

- Reading Standards for Informational Text

- Reading Standards for Foundational Skills

- Writing Standards

- Speaking and Listening Standards

- Language Standards

Download the Iowa Core K-12 Literacy Manual . You will use it as a reference when you are creating lessons.

Next, explore the Subject Area pages and resources. What tools does the state provide to teachers to support their use of the Core?

Describe a resource you found on the website. How will you use this when you are a teacher?

Watch this video about the Iowa Literacy Core Standards:

- Literacy is typically defined as the ability to ingest, understand, and communicate information.

- Literacy has multiple definitions, each with a different point of focus.

- “New literacies,” or multiliteracies, are a combination of multiple ways of communicating and making meaning, including visual, audio, spatial, behavioral, and gestural communication.

- As online communication has become more prevalent, digital literacy has become more important for learners to engage with the wealth of information available online.

- Critical literacy develops learners’ critical thinking by asking them to use an analytic lens that detects power, privilege, and representation to understand different ways of looking at information.

- The Common Core State Standards were established to set clear, universal guidelines for what every student should know after completing high school.

Resources for teacher educators

- Culturally Responsive-Sustaining Education Framework [PDF]

- Common Core State Standards

- Iowa Core Instructional Resources in Literacy

Gonzalez, N., Moll, L. C., & Amanti, C. (Eds.). (2006). Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households, communities, and classrooms . New York, NY: Routledge.

Lau, S. M. C. (2012). Reconceptualizing critical literacy teaching in ESL classrooms. The Reading Teacher, 65 , 325–329.

Literacy. (2018, March 19). Retrieved March 2, 2020, from https://en.unesco.org/themes/literacy

Neuman, S. B., & Celano, D. (2001). Access to print in low‐income and middle‐income communities: An ecological study of four neighborhoods. Reading Research Quarterly, 36 (1), 8-26.

Neuman, S. B., & Moland, N. (2019). Book deserts: The consequences of income segregation on children’s access to print. Urban education, 54 (1), 126-147.

New London Group (1996). A Pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66 (1), 60-92.

O’Brien, J. (2001). Children reading critically: A local history. In B. Comber & A. Simpson (Eds.), Negotiating critical literacies in classrooms (pp. 41–60). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ordoñez-Jasis, R., & Ortiz, R. W. (2006). Reading their worlds: Working with diverse families to enhance children’s early literacy development. Y C Young Children, 61 (1), 42.

Saha S. (2006). Improving literacy as a means to reducing health disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 21 (8):893-895. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00546.x

UNESCO. (2017). Literacy rates continue to rise from one generation to the next global literacy trends today. Retrieved from http://on.unesco.org/literacy-map.

Vasquez, V.M., Janks, H. & Comber, B. (2019). Critical Literacy as a Way of Being and Doing. Language Arts, 96 (5), 300-311.

Vlieghe, J. (2015). Traditional and digital literacy. The literacy hypothesis, technologies of reading and writing, and the ‘grammatized’ body. Ethics and Education, 10 (2), 209-226.

Zimmerman, E. B., Woolf, S. H., Blackburn, S. M., Kimmel, A. D., Barnes, A. J., & Bono, R. S. (2018). The case for considering education and health. Urban Education, 53 (6), 744-773.U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences.

U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), 2022 Reading Assessment.

Methods of Teaching Early Literacy Copyright © 2023 by Constance Beecher is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

The Complete Guide to Educational Literacy

Educational literacy is hugely important and is the driving factor in how well students make progress, but why? Why is it that literacy is important in all subjects?

What is Educational Literacy? Educational literacy is the driving factor in all subjects. In order for students to learn, they need to be able to access the learning. Educational literacy is more than just being able to read, write and spell, it is about students being able to interpret, react, articulate and express their thoughts.

In the introduction to the Education Endowment Foundation’s Literacy guidance reports , Sir Kevan Collins states that:

“ disadvantaged students in England are still significantly more likely than their classmates to leave formal education without being able to read, write and communicate effectively ”

“young people who leave school without good literacy skills are held back at every stage of life”.

What is Literacy?

We cannot, and should not, assume that the literacy of children is a solely academic pursuit and school responsibility; literacy is a ‘Life Skill’ and as such we as teachers and instructors play only a part in its development – hence why so much of literacy must be seen as domain-specific; the prefix of ‘educational’ helps to signpost this.

“We believe literacy is the ability to read, write, speak and listen well. A literate person is able to communicate effectively with others and to understand written information.”

The National Literacy Trust (NLT)

Literacy is the gateway to accurate communication, to being understood.

If, like me, you seethe with rage whenever someone can’t read or interpret ‘Parent & Child Parking’ or ‘Keep Dogs on Leads’ then the foundation of this ire is perhaps the lack of literacy (if we are being generous) of the supposed culprit.

To be literate (in all its forms) is to understand.

This understanding can be on a surface (explicit) level or can be deeper, using inference and association to draw out hidden or implied meanings. Literacy is more than just being able to spell – it is being able to interpret, react, articulate and express across a range of mediums.

The NLT in 2008 also stated that literacy has a “ significant relationship with a person’s happiness and success “; if we can, as they cite above, read, write, speak and listen well we can succeed in a range of contexts and scenarios.

However, these skills, unlike many, are not innate; they have to be taught to some degree of fluency to ensure that success.

The development of Literacy skills within a child is a journey that starts from their very first breath and continues throughout their school career, across the phases and subjects, and then into their varied and respective disciplines of work and adult life.

Every area of society has its own language and method of communication, and Literacy therefore becomes an essential aspect of everyone’s existence; to read, write, speak and listen in these is to exist within them.

In 2009 Beck and McKeown stated that “ reports from research and the larger educational community demonstrate that too many students have limited ability to comprehend texts “.

We cannot let this continue.

Why is Literacy Important in an Educational Context?

Essentially, in order to enable students to communicate and express themselves in the wider world they need to be able to read and write!

Every subject and phase has its own literacy requirements but ultimately we need to ensure students can access the learning , wherever that is taking place.

Much literacy is inadvertently picked up from home and social interactions, which is where the Matthew Effect begins to take hold. In 1983 Wahlberg & Tsai coined the term ‘Matthew Effect’ in order to describe the cumulative advantage of educative factors such as reading, based on the verses from Matthew’s Gospel. –

“ For unto every one that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance: but from him that hath not shall be taken away even that which he hath “.

Essentially, the rich get richer, the poor get poorer.

In 1986 Stanovich took this further to look specifically at literacy acquisition, looking at how to solve what he called “ rich-get-richer and poor-get-poorer patterns of reading achievement “.

His paper is lengthy but the main and relevant findings are that reading well from an early age helps to build not only sequential understanding but also syntactic skills, vocabulary knowledge, general knowledge and develops memory and cognitive functioning, as well as building empathy and confidence in students.

The link here to cognition and the processes of learning are made explicit, and the idea that we need those facts to develop that knowledge are reinforced.

In the mid-1990s Hart and Risley conducted some research into American families that looked at the everyday language encountered by children in their early years and noted some startling data in relation to social and family dynamic and the early acquisition of words.

To quote their 2003 American Educator paper , the children grew “like their parents ” in “ vocabulary resources and in language and interaction styles “.

They found that vocabulary use at the age of 3 was “ predictive of measures of language skill at age 9 -10 ” and said vocabulary was also “ strongly associated with reading comprehension ” in later stages of Primary development.

The 30 Million Word Gap

They came up with the concept of a 30 Million Word Gap; those children growing up in disadvantaged or literacy-poor households were, by the age of 4, exposed to 30 million fewer total words in interaction and conversation with them than those from a more prosperous and literacy-rich environment.

Essentially, students from disadvantaged backgrounds suffer from an early age and continue to suffer because of it – that Matthew Effect cited above.

Naturally, if you aren’t good at something and are not encouraged in it you lose interest in it and then become almost fearful of it.

…and we wonder why so many students claim to not like reading!

There is a growing need to ensure that students are trained to access the academic language and conventions of different subjects.

Strategies grounded in disciplinary literacy aim to meet this need, building on the premise that each subject has its own unique language, ways of knowing, doing, and communicating.

This starts as soon as communication and interactions are recognized. Child Language Acquisition is a fascinating area of research and interest.

It can also be argued that much of the poor behavior in classrooms can be attributed to the students’ disengagement when a text is too complex or the vocabulary has not been properly decoded.

One of the key things to force home early in the great literacy battle is that it is not all about spelling and grammar – far from it.

Too often the focus is on the written word and how literacy (or the lack thereof) can manifest itself in poor quality extended writing or badly spelt student responses.

In fact much of literacy is around the ability to read and understand material in a range of contexts – reading must be taught explicitly across the key stages, and reading ages and ability must be taken into account when preparing material.

David Didau puts it nice and bluntly – “ just because students struggle to read doesn’t mean they’re thick “.

We have to constantly cater for the development of the literacy in the disciplines we are working within.

Literacy – in particular reading – can be taught alongside or in conjunction with all content within lessons and follows similar cognitive paths; working memory (and the capacity thereof) has a direct effect on reading ability as students can feel overwhelmed by poorly edited or presented material.

Their comprehension of the material they are presented with is also hugely context specific and relates to their general or disciplinary knowledge. I often find that I assume a student can infer a particular idea or emotion when in fact they lack the factual wherewithal to make the connection.

Understanding a text is a problem to be solved, and we cannot solve problems without facts!

What are the Barriers to Effective Literacy Instruction?

There are many barriers, of course – a lot of them are systemic and difficult to shift, but often these are also attitudinal; expectations are low so outcomes remain capped.

Yes, many students come to education significantly behind their chronological age in terms of reading ability and comprehension, but we must be positive and outward-facing in our approach, as well as realistic about what the barriers to understanding really are.

We must never make assumptions!

Let’s take an example :

If we read the following with a knowledge of cricket we can understand entirely what is going on, but if we have no working knowledge of that wonderful game then we are at a loss; lots of words we might understand, but absolutely no context!

Danger of assumption!

Jos Buttler hit a century but England were unable to force victory in their final warm-up match against New Zealand A in Whangarei. Resuming on 88 on day three, Buttler made 110 to help his side post 405 in reply to the hosts’ 302-6 declared.

( I have zero cricket knowledge, I can read the words but I have no idea what they mean! Paul Stevens-Fulbrook ).

Context is King!

The ITT Core Content Framework (2019) uses a “ Learn That ” and “ Learn How To By ” format to provide a basis for each Teaching Standard. Literacy falls under TS3, so we can benefit by looking at the basic statements of competency and performance in this area. Firstly:

Learn that…

“Every teacher can improve pupils’ literacy, including by explicitly teaching reading, writing and oral language skills specific to individual disciplines.”

This is key as it firmly places the responsibility at the door of all teachers, not just the cardigan-wearing book lovers in the English department.

Literacy must be seen as a whole-school responsibility with a discipline-by-discipline adaptive strategy – key generic ideas that can be modified to suit each subject area. To go back to George Sampson in 1922:

“Every teacher is a teacher of English because every teacher is a teacher in English”.

Pithy, but apt !

Now let’s look at the next stage of the framework – HOW to teach Literacy:

Learn how to by…

• Discussing and analyzing with expert colleagues how to support younger pupils to become fluent readers and to write fluently and legibly.

• Receiving clear, consistent and effective mentoring in how to model reading comprehension by asking questions, making predictions, and summarizing when reading.

• Receiving clear, consistent and effective mentoring in how to promote reading for pleasure (e.g. by using a range of whole class reading approaches and regularly reading high-quality texts to children).

• Discussing and analyzing with expert colleagues how to teach different forms of writing by modelling, planning, drafting and editing.

Key phrases for me here are the “ expert colleagues ” and “effective mentoring”.

Standards only really improve if people share and collaborate to ensure mutual success; just as we as teachers model best practice in our classrooms so must we as teacher educators model the highest standards of pedagogy.

We also see herein the repetition of the word ‘ model ’ – students need to be shown the process of literacy; they need to hear the words being used in correct (and incorrect) contexts, they need to have explained to them why choices have been made, they need to see good writing and Oracy modeled and developed over time.

They need to be told stories that help them align concepts with understanding and where vocabulary is championed and celebrated.

Teaching Literacy Across From Early Years to Secondary

For more support and ideas the Education Endowment Foundation reports are an excellent starting point, summarizing and synthesizing the best evidence in Literacy development from Early Years through to Secondary.

They are too detailed and phase-specific to go into individual details here but the common threads running through the recommendations are as follows:

- Prioritizing development of Literacy skills, including Oracy

- Developing self-regulation and motivation when planning, drafting and developing written pieces

- Extensive practice, including modelling and guidance until independence can be obtained and fluency reached

- Promotion of active reading strategies

- Disciplinary approach (moving to Secondary), prioritized across the curriculum and promoting the specialist vocabulary of each subject area (discipline).

- Balanced and engaged approach to reading ability that integrates decoding and comprehension

- High-quality (a much-repeated phrase in the literature) assessment to identify issues and support to solve them

We learn more about Literacy and its development from their work:

- There is a growing need to ensure that students are trained to access the academic language and conventions of different subjects.

- Strategies grounded in disciplinary literacy aim to meet this need, building on the premise that each subject has its own unique language, ways of knowing, doing, and communicating

We have a duty to ensure that the development of disciplinary literacy is coherently aligned with curriculum development.

For example, in Art, that the development of drawing skill is paired with teaching students how to make high quality annotations utilizing specialist vocabulary.

A good way of explaining this is to look at the command words used in each subject for the purposes of assessment and instruction – does ‘evaluate’ in English mean the same as ‘Evaluate’ in Mathematics?

Not directly, no; a very different process using different tools but the same word – how easy it is for students to become confused if the vocabulary is not taught explicitly within the domain.

If they can’t read or understand what the question is asking them to do, how on earth can they get to the right answer!

As Geoffrey Petty states in his excellent Evidence Based Teaching from 2009, “ many students believe that ‘describe’, ‘explain’, ‘analyze’ and ‘evaluate’ all mean pretty much the same thing: ‘write about’. “.

Our approach to literacy development must be strategic and planned, not random or one-off. It must be iterative, monitored and evaluated, knowing of course what ‘success’ looks like.

As with anything, know what you want to achieve and plan towards it; the starting point is ‘what problem do I need to solve?’, and this should be aligned with the specific disciplinary need of the literacy – extended writing? Spelling of key terms? Grammar? Paragraphing? Expression? Response to a source text? Labeling a diagram? Writing in bullet points? Inference?

The best approach from a subject perspective is to consider the specific literacy needs within the subject itself, especially the final assessment papers – how do students have to read or write in order to achieve?

A great source of material are the annual exam board reports which often cite where questions have been misunderstood, material misinterpreted or errors made that can be grouped under ‘literacy’.

Use assessment and judgment to diagnose the problem, ascertain the need and then prescribe the appropriate solution; focus on the outcomes and vary the process dependent on the cohort to ensure an equitable approach.

Practical Approaches to Teaching Literacy. Where to Start.

So, what can we do? Let’s start with vocabulary – to quote Mary Myatt from Gallimaufry to Curriculum :

“If we are serious about closing the gap between those pupils who come from language-rich backgrounds and those who do not then we need to pay careful attention to the building of vocabulary”.

Here are some suggestions from Margaret McKeown in her 2019 paper ‘ Effective Vocabulary Instruction ’:

- Choosing words to teach

- Inclusion of morphological information

- Engaging students in interactions around words

McKeown states that “ effective instruction means bringing students’ attention to words in ways that promote not just knowing word meanings but also understanding how words work and how to utilize word knowledge effectively “.

The building blocks of literacy; understanding meaning.

When we learn to read we follow a process – Basic, Intermediary, Disciplinary – moving from ‘learning to read’ to ‘reading to learn’; this takes time and no shortage of effort from all concerned, including the students!

Time and effort are the constituents of practice, and practice is very much what is needed!

An understanding of memory and cognition is essential to embedding literacy concepts in students from an early age and encouraging the recall and application of appropriate vocabulary, so we as teachers have to keep ourselves abreast of the literacy skills and needs of our students in their domain so we can plan and instruct appropriately.

As far back as 1985 McKeown et al stated that “ a desirable goal of vocabulary instruction is to enhance higher order processing skills such as comprehension ” and urged that the method chosen was carefully researched in order to ensure it was the most effective way of getting to the desired end-goal.

As we know, one size very rarely fits all so be careful to design an intervention or strategy that will optimize the chances of achieving your desired outcome(s).

McKeown et al’s key message though was a simple one:

Regular encounters with the vocabulary in a range of contexts to see how words function in different settings is the best approach; practice, practice, practice!

The more students hear words, read words, write words and experience words in action the greater their exposure, the greater their confidence and the higher their motivation and self-efficacy, no matter how transient in this your role as the classroom teacher who sees them for 3 hours a week may feel.

A good starting point for your own practice and what to teach when is to consider the three ‘tiers’ of vocabulary:

- Tier 1 – basic vocabulary

- Tier 2 – high frequency and multiple use / meaning vocabulary (cross-discipline)

- Tier 3 – subject-related / domain specific.

The focus for teaching varies according to phase, age and need but much work in schools is focused around Tier 2 and Tier 3.

Teachers need to understand the basic cognitive processes and the way students take on information, as well as transfer from working to long-term memory and the subsequent retrieval.

A good way to reinforce and practice vocabulary and its use is of course through regular review and retrieval practice, interleaving and re-visiting it throughout a teaching sequence, as with any concept or key idea.

Information needs to regularly recalled otherwise it will be completely forgotten – especially vocabulary!

Strategies for Teaching Literacy

As mentioned above, once you have identified your students and their needs you can begin to offer interventions and use a range of strategies to promote and develop the literacy in your classrooms; start where you have the most control!

Literacy does need to be a whole-school focus but the groundwork is done through the individual instruction of the teachers.

Here are a few techniques you can try:

- The Frayer Model – a great technique for exploring definitions, meanings, non-meanings and vocabulary use, and very good for retrieval

- Morphology – explicit deconstruction of words and their formations and meanings to help create connections promote what Alex Quigley calls “ word consciousness ” (a curiosity for and about words)

- Quizzing and low-stakes testing – again a great way to retrieve and practice using vocabulary in correct contexts

- Sketching, Mapping, Graphic Organizing and Drawing (not explicitly Dual Coding – careful!), in particular the Drawing Effect*(See reference section below); to return to Beck and McKeown (2009), “ The importance of making connections among ideas is paramount “

- Scaffolds such as Structure Strips (which can be gradually removed or adapted to fade out the teacher support and promote independent practice from students)

- Flashcards – the Leitner method, perhaps? Try combining aspects of Paivio’s work on Dual Coding Theory and have the term and image on one side and the definition on the other; the students can create these themselves or you can help avoid those “ seductive details ” (Harp & Mayer) and create models yourself

- Encouraging reading out loud, making the link to performance – reading out loud has benefits; this is The Production Effect – producing something with new information straight away to anchor it in your mind (Forrin and MacLeod 2018)

- Story-telling; give words and phrases life, character, worlds and settings – connect them to personal experiences and emotions to make them more concrete

- Oracy – promote academic and intellectual debate within your classroom at all times; celebrate the use of language and how it can be a tool for critical and analytical debate

In Closing The Vocabulary Gap , Alex Quigley suggests the following considerations when teaching vocabulary in context:

- Mis-directive contexts; these are unhelpful and guide students towards incorrect meanings (irony / sarcasm / word play)

- Non-directive contexts; these offer little help at all with the definition of a word

- General contexts; non-specific surrounding descriptions to allow a student to possibly infer the meaning of a word

- Directive contexts; where enough precise information or description is given in order to make meaning clear

Quigley promotes a SEEC model – Select, Explain, Explore, Consolidate – when working with vocabulary, and from then on into reading.

Beck & McKeown also promote exploring words in a range of contexts so they think about how the words work.

Once students can understand the texts and see writing at work they then become more able to emulate and mirror these skills in their own work. Remember that literacy is not just vocabulary, but vocabulary is Literacy!

As ever, small steps are important to avoid swamping students or unbalancing that cognitive load that is so important to their ability to take on, retain and use material – less is often more!

Also, if you can, consider the power of support outside the classroom – the impact of parental engagement (remember the Matthew Effect?).

Senechal and LeFevre (2002) found that the amount of books a child was exposed to by the age of 6 was a positive predictor of their reading ability by the time they turned 8 – a cross-stage approach!

Conclusions in Educational Literacy

You will always be modelling to students, either consciously or not; you teach because you care and you want to develop students and their opportunities and chances for success.

There can be a clear link drawn between Literacy, Social Mobility and Cultural Capital and cycles can be broken, gaps can be closed, but those gaps have to be acknowledged in order to help find suitable solutions.

Whatever subject you teach, you have a responsibility to ensure students know and understand it – all of this knowledge and understanding comes from words and language, meaning that you have a responsibility as a teacher to promote words and language – literacy.

Don’t go for a scattergun approach; use the evidence, use your assessment (high-quality), use what you garner from your assessment to help make informed decisions (otherwise there was little point in conducting the assessment in the first place…) and put in place robust, supported and well-monitored strategies, allowing that degree of autonomy so valuable to success.

Trust your professional judgment and, above all, promote a love of reading!

References:

Rethinking Reading Comprehension Instruction: A Comparison of Instruction for Strategies and Content Approaches; Margaret G. McKeown, Isabel L. Beck, Ronette G.K. Blake (2009)

Some Effects of the Nature and Frequency of Vocabulary Instruction on the Knowledge and Use of Words: Margaret G. McKeown, Isabel L. Beck, Richard C. Omanson and Martha T. Pople: Reading Research Quarterly, Vol. 20, No. 5 (Autumn, 1985), pp. 522-535

Matthew Effects in Reading: Some Consequences of Individual Differences in the Acquisition of Literacy: Keith E. Stanovich; Reading Research Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 4 (Autumn, 1986), pp. 360-407

Matthew Effects in Education; Wahlberg and Tsai; American Educational Research Journal Fall 1983, Vol. 20, No. 3, Pp. 359-373

* The Drawing Effect’ (Wammes, Meade and Fernandez, 2016).

(Taken from my article for Impact for the Chartered College):

The study had found that ‘drawing a to-be-remembered stimulus was superior to writing it out’ and that ‘drawing pictures of words presented during an incidental study phase [provided] a measurable boost to later memory performance’.

Many studies show information presented as pictures compared to words (e.g., Paivio) is more likely to be remembered. Paivio’s theory was that the creation or formation of mental images aids retention and retrieval of information, which is the essence of learning. At its heart it is the use of pictures associated with key learning goals – in this case vocabulary. Where information is taken in via two channels – the verbal and the visual, retention and retrieval are strengthened; memory traces are doubled.

Essentially, ‘The Drawing Effect’ proposes that drawing leads to better later memory performance, and therefore enhances retrieval (Cohen’s d for Draw vs Write = 1.51 – other data published within the paper itself). They also suggest that ‘drawing improves memory by encouraging a seamless integration of semantic, visual, and motor aspects.’

Their feeling was that as well as deepening the semantic processing, the act of drawing provided mechanical information and response, similar to that gained from acting something out. There is a process behind the creation of an image that requires thought (and ‘memory is the residue of thought’ (Willingham)!). To take a word heard and manifest it as a visual representation requires the listener to process the word and generate its physical characteristics (‘elaboration’), see it in their mind (‘visual imagery’) and then draw it (‘motor action’). The picture is then a multi-pathway memory cue for later retrieval.

JD. Wammes, Melissa E. Meade & Myra A. Fernandes (2016) The drawing effect: Evidence for reliable and robust memory benefits in free recall, The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 69:9, 1752-1776,

Paivio (1990) A Dual Coding Approach; Oxford University Press

Educational Literacy FAQ

Put simply, it is the different literacy skills needed to access and understand key concepts in subjects at school, as well as the overspill this has into the day-to-day life and success of an individual.

The OECD report of 2002 claimed that reading for pleasure is perhaps the single most important indicator of a child’s future success!

Similar Posts:

- 35 of the BEST Educational Apps for Teachers (Updated 2024)

- 25 Tips For Improving Student’s Performance Via Private Conversations

- Discover Your Learning Style – Comprehensive Guide on Different Learning Styles

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name and email in this browser for the next time I comment.

We use necessary cookies that allow our site to work. We also set optional cookies that help us improve our website.

For more information about the types of cookies we use, and to manage your preferences, visit our Cookies policy here.

What is literacy?

The word literacy is defined as the ability to read, write, speak and listen in a way that lets us communicate effectively and make sense of the world.

The importance of literacy

However, understanding the significance of literacy goes far beyond its definition.

Literacy is essential. Without literacy, it’s hard to live the life you want. From your earliest years, literacy skills help you develop and communicate. But when you have a tough start in life, it’s easy to fall behind.

At school, having the literacy skills to read, write, speak and listen are vital for success. If you find these things hard, then you struggle to learn. It affects your confidence and self-esteem.

As an adult, without these same literacy skills, you can’t get the jobs you want, and navigating every day life can be difficult – from using the internet, to filling out forms or making sense of instructions on medicines or road signs. If you have children, it’s hard to support their learning, and so the cycle continues.

Low levels of literacy undermine the UK’s economic competitiveness, costing the taxpayer £2.5 billion every year ( KPMG, 2009 ). A third of businesses are not satisfied with young people’s literacy skills when they enter the workforce and a similar number have organised remedial training for young recruits to improve their basic skills, including literacy and communication.

Literacy statistics

Our research underpins our programmes, campaigns and policy work to improve literacy skills, attitudes and habits across the UK.

Children who enjoy reading and writing are happier with their lives

Children who enjoy reading are three times more likely to have good mental wellbeing than children who don’t enjoy it. Read our research report from 2019.

1 in 15 children and young people aged 8 to 18 do not have a book of their own at home.

Children who say they have a book of their own are six times more likely to read above the level expected for their age than their peers who don’t own a book. Read our Book ownership in 2022 report.

Children born into communities with the most serious literacy challenges have some of the lowest life expectancies in England

A boy born in Stockton Town Centre (an area with serious literacy challenges) has a life expectancy 26.1 years shorter than a boy born in North Oxford. Read more.

1 in 2 children in the UK enjoy reading

Only 1 in 2 children and young people said they enjoy reading in early 2022, which is as low as the number has ever been since we first asked the question in 2005. Read more.

1 in 3 children in the UK enjoy writing

In 2023, 1 in 3 children and young people aged 8 to 18 said that they enjoy writing in their free time. Our 2023 report into children and young peoples' writing in 2023 showed that levels of writing enjoyment have reduced by 12.2 percentage points over the past 13 years. Read our full report.

Audiobooks can support wider literacy engagement

1 in 5 children and young people said that listening to an audiobook or podcast has got them interested in reading books. Read more.

Adult literacy rate

16.4% of adults in England, or 7.1 million people, can be described as having 'very poor literacy skills.' Adults with poor literacy skills will be locked out of the job market and, as a parent, they won’t be able to support their child’s learning.

But that's not the end of the story...

We believe that together, we can break the cycle. We believe that literacy is for everyone so we continue to work in schools and with communities to bring real change through our inspiring and evidence-based programmes, resources and activities.

More information about literacy

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Critical literacy.

- Vivian Maria Vasquez Vivian Maria Vasquez American University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.20

- Published online: 29 March 2017

Changing student demographics, globalization, and flows of people resulting in classrooms where students have variable linguistic repertoire, in combination with new technologies, has resulted in new definitions of what it means to be literate and how to teach literacy. Today, more than ever, we need frameworks for literacy teaching and learning that can withstand such shifting conditions across time, space, place, and circumstance, and thrive in challenging conditions. Critical literacy is a theoretical and practical framework that can readily take on such challenges creating spaces for literacy work that can contribute to creating a more critically informed and just world. It begins with the roots of critical literacy and the Frankfurt School from the 1920s along with the work of Paulo Freire in the late 1940s (McLaren, 1999; Morrell, 2008) and ends with new directions in the field of critical literacy including finding new ways to engage with multimodalities and new technologies, engaging with spatiality- and place-based pedagogies, and working across the curriculum in the content areas in multilingual settings. Theoretical orientations and critical literacy practices are used around the globe along with models that have been adopted in various state jurisdictions such as Ontario, in Canada, and Queensland, in Australia.

- critical literacy

- critical pedagogy

- social justice

- multiliteracies

- text analysis

- discourse analysis

- everyday politics

- language ideologies

Changing student demographics, globalization, and flows of people resulting in classrooms where students have variable linguistic repertoire, in combination with new technologies, has resulted in new definitions of what it means to be literate and how to teach literacy. Today, more than ever, we need frameworks for literacy teaching and learning that can withstand such shifting conditions across time, space, place, and circumstance, and thrive in challenging conditions. Critical literacy is a theoretical and practical framework that can readily take on such challenges creating spaces for literacy work that can contribute to creating a more critically informed and just world.

Historical Orientation

Luke ( 2014 ) describes critical literacy as “the object of a half-century of theoretical debate and practical innovation in the field of education” (p. 21). Discussion about the roots of critical literacy often begin with principles associated with the Frankfurt School from the 1920s and their focus on Critical Theory. The Frankfurt School was created by intellectuals who carved out a space for developing theories of Marxism within the academy and independently of political parties. While focusing on political and economic philosophy, they emphasized the importance of class struggle in society. More prominently associated with the roots of critical literacy is Paulo Freire, beginning with his work in the late 1940s (McLaren, 1999 ; Morrell, 2008 ), which focused on critical consciousness and critical pedagogy. Freire’s work was centered on key concepts, which included the notion that literacy education should highlight the critical consciousness of learners. In his work in the 1970s Freire wrote that if we consider learning to read and write as acts of knowing, then readers and writers must assume the role of creative subjects who reflect critically on the process of reading and writing itself along with reflecting on the significance of language ( 1972 ). Together with Macedo in the 1980s, Freire popularized the concept that reading is not just about decoding words. In their work, Freire and Macedo ( 1987 ) noted that reading the word is simultaneously about reading the world. This means that our reading of any text is mediated through our day-to-day experience and the places, spaces, and languages that we encounter, use, and occupy. This critical reading can lead to disrupting and “unpacking myths and distortions and building new ways of knowing and acting upon the world” (Luke, 2014 , p. 22). As such this conceptualization of critical literacy disrupts the notion of false consciousness described earlier by Hegel and Marx (Luke, 2014 ).

The Frankfurt School scholars and Freire focused their work on adult education. For instance in the 1960s Freire organized a campaign for hundreds of sugar cane workers in Brazil to participate in a literacy program that centered on critical pedagogy. His work became known as liberatory, whereby he worked to empower oppressed workers. Critiques of Freire have focused primarily on claims that the liberatory pedagogy he espoused was unidirectional because educators liberated students. The binary represented here was also seen as problematic. Nevertheless his grounding work pushed to the fore the importance and effects of critical pedagogy as a way of making visible and examining relations of power to change inequitable ways of being. Work done by the Frankfurt School and Freire were overtly political and inspired the political nature and democratic potential of education as central to critical approaches to pedagogy (Comber, 2016 ) as seen in work done by researchers and educators such as Campano, Ghiso and Sánchez ( 2013 ), Janks ( 2010 ), and Vasquez ( 2004 ).