Essays About Beauty: Top 5 Examples and 10 Prompts

Writing essays about beauty is complicated because of this topic’s breadth. See our examples and prompts to you write your next essay.

Beauty is short for beautiful and refers to the features that make something pleasant to look at. This includes landscapes like mountain ranges and plains, natural phenomena like sunsets and aurora borealis, and art pieces such as paintings and sculptures. However, beauty is commonly attached to an individual’s appearance, fashion, or cosmetics style, which appeals to aesthetical concepts. Because people’s views and ideas about beauty constantly change , there are always new things to know and talk about.

Below are five great essays that define beauty differently. Consider these examples as inspiration to come up with a topic to write about.

1. Essay On Beauty – Promise Of Happiness By Shivi Rawat

2. defining beauty by wilbert houston, 3. long essay on beauty definition by prasanna, 4. creative writing: beauty essay by writer jill, 5. modern idea of beauty by anonymous on papersowl, 1. what is beauty: an argumentative essay, 2. the beauty around us, 3. children and beauty pageants, 4. beauty and social media, 5. beauty products and treatments: pros and cons, 6. men and makeup, 7. beauty and botched cosmetic surgeries, 8. is beauty a necessity, 9. physical and inner beauty, 10. review of books or films about beauty.

“In short, appreciation of beauty is a key factor in the achievement of happiness, adds a zest to living positively and makes the earth a more cheerful place to live in.”

Rawat defines beauty through the words of famous authors, ancient sayings, and historical personalities. He believes that beauty depends on the one who perceives it. What others perceive as beautiful may be different for others. Rawat adds that beauty makes people excited about being alive.

“No one’s definition of beauty is wrong. However, it does exist and can be seen with the eyes and felt with the heart.”

Check out these essays about best friends .

Houston’s essay starts with the author pointing out that some people see beauty and think it’s unattainable and non-existent. Next, he considers how beauty’s definition is ever-changing and versatile. In the next section of his piece, he discusses individuals’ varying opinions on the two forms of beauty: outer and inner.

At the end of the essay, the author admits that beauty has no exact definition, and people don’t see it the same way. However, he argues that one’s feelings matter regarding discerning beauty. Therefore, no matter what definition you believe in, no one has the right to say you’re wrong if you think and feel beautiful.

“The characteristic held by the objects which are termed “beautiful” must give pleasure to the ones perceiving it. Since pleasure and satisfaction are two very subjective concepts, beauty has one of the vaguest definitions.”

Instead of providing different definitions, Prasanna focuses on how the concept of beauty has changed over time. She further delves into other beauty requirements to show how they evolved. In our current day, she explains that many defy beauty standards, and thinking “everyone is beautiful” is now the new norm.

“…beauty has stolen the eye of today’s youth. Gone are the days where a person’s inner beauty accounted for so much more then his/her outer beauty.”

This short essay discusses how people’s perception of beauty today heavily relies on physical appearance rather than inner beauty. However, Jill believes that beauty is all about acceptance. Sadly, this notion is unpopular because nowadays, something or someone’s beauty depends on how many people agree with its pleasant outer appearance. In the end, she urges people to stop looking at the false beauty seen in magazines and take a deeper look at what true beauty is.

“The modern idea of beauty is taking a sole purpose in everyday life. Achieving beautiful is not surgically fixing yourself to be beautiful, and tattoos may have a strong meaning behind them that makes them beautiful.”

Beauty in modern times has two sides: physical appearance and personality. The author also defines beauty by using famous statements like “a woman’s beauty is seen in her eyes because that’s the door to her heart where love resides” by Audrey Hepburn. The author also tackles the issue of how physical appearance can be the reason for bullying, cosmetic surgeries, and tattoos as a way for people to express their feelings.

Looking for more? Check out these essays about fashion .

10 Helpful Prompts To Use in Writing Essays About Beauty

If you’re still struggling to know where to start, here are ten exciting and easy prompts for your essay writing:

While defining beauty is not easy, it’s a common essay topic. First, share what you think beauty means. Then, explore and gather ideas and facts about the subject and convince your readers by providing evidence to support your argument.

If you’re unfamiliar with this essay type, see our guide on how to write an argumentative essay .

Beauty doesn’t have to be grand. For this prompt, center your essay on small beautiful things everyone can relate to. They can be tangible such as birds singing or flowers lining the street. They can also be the beauty of life itself. Finally, add why you think these things manifest beauty.

Little girls and boys participating in beauty pageants or modeling contests aren’t unusual. But should it be common? Is it beneficial for a child to participate in these competitions and be exposed to cosmetic products or procedures at a young age? Use this prompt to share your opinion about the issue and list the pros and cons of child beauty pageants.

Today, social media is the principal dictator of beauty standards. This prompt lets you discuss the unrealistic beauty and body shape promoted by brands and influencers on social networking sites. Next, explain these unrealistic beauty standards and how they are normalized. Finally, include their effects on children and teens.

Countless beauty products and treatments crowd the market today. What products do you use and why? Do you think these products’ marketing is deceitful? Are they selling the idea of beauty no one can attain without surgeries? Choose popular brands and write down their benefits, issues, and adverse effects on users.

Although many countries accept men wearing makeup, some conservative regions such as Asia still see it as taboo. Explain their rationale on why these regions don’t think men should wear makeup. Then, delve into what makeup do for men. Does it work the same way it does for women? Include products that are made specifically for men.

There’s always something we want to improve regarding our physical appearance. One way to achieve such a goal is through surgeries. However, it’s a dangerous procedure with possible lifetime consequences. List known personalities who were pressured to take surgeries because of society’s idea of beauty but whose lives changed because of failed operations. Then, add your thoughts on having procedures yourself to have a “better” physique.

People like beautiful things. This explains why we are easily fascinated by exquisite artworks. But where do these aspirations come from? What is beauty’s role, and how important is it in a person’s life? Answer these questions in your essay for an engaging piece of writing.

Beauty has many definitions but has two major types. Discuss what is outer and inner beauty and give examples. Tell the reader which of these two types people today prefer to achieve and why. Research data and use opinions to back up your points for an interesting essay.

Many literary pieces and movies are about beauty. Pick one that made an impression on you and tell your readers why. One of the most popular books centered around beauty is Dave Hickey’s The Invisible Dragon , first published in 1993. What does the author want to prove and point out in writing this book, and what did you learn? Are the ideas in the book still relevant to today’s beauty standards? Answer these questions in your next essay for an exiting and engaging piece of writing.

Grammar is critical in writing. To ensure your essay is free of grammatical errors, check out our list of best essay checkers .

Maria Caballero is a freelance writer who has been writing since high school. She believes that to be a writer doesn't only refer to excellent syntax and semantics but also knowing how to weave words together to communicate to any reader effectively.

View all posts

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.1: What is beauty?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 222897

“ What is Beauty? ” YouTube, uploaded by CNN, 16 Mar. 2018.

What is beauty?

In 2018 CNN made a brief video tracing how women’s beauty has been defined over time and how those perceptions of beauty “leave women in constant pursuit of the ideal.” How have perceptions of beauty changed over time? How do those definitions apply to things beyond women’s beauty? Rory Corbett addresses beauty from an interesting perspective in his essay, “What is Beauty?” in which he notes that, “beauty is not just a visual experience; it is a characteristic that provides a perceptual experience to the eye, the ear, the intellect, the aesthetic faculty, or the moral sense. It is the qualities that give pleasure, meaning or satisfaction to the senses, but in this talk I wish to concentrate on the eye, the intellect and the moral sense.” What does the author mean by “the moral sense”? How does Corbett’s essay expand your thinking of what beauty is?

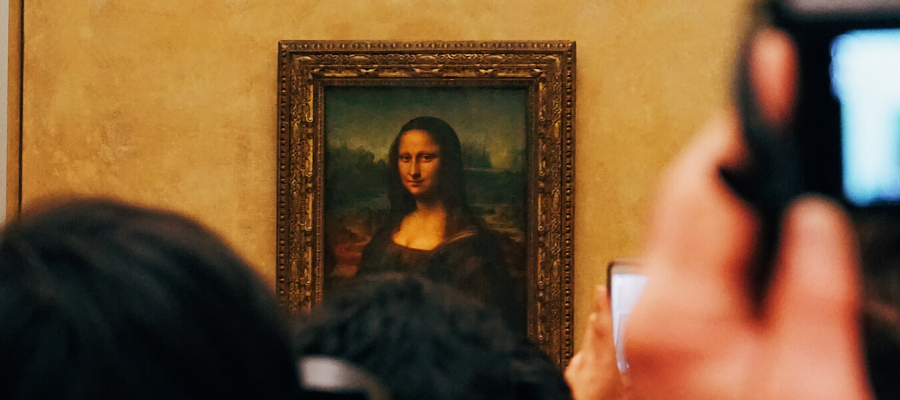

Art and the Aesthetic Experience

Beauty is something we perceive and respond to. It may be a response of awe and amazement, wonder and joy, or something else. It might resemble a “peak experience” or an epiphany. It might happen while watching a sunset or taking in the view from a mountaintop, for example. This is a kind of experience, an aesthetic response that is a response to the thing’s representational qualities , whether it is man-made or natural (Silverman). The subfield of philosophy called aesthetics is devoted to the study and theory of this experience of the beautiful; in the field of psychology, aesthetics is studied in relation to the physiology and psychology of perception.

Aesthetic analysis is a careful investigation of the qualities which belong to objects and events that evoke an aesthetic response. The aesthetic response is the thoughts and feelings initiated because of the character of these qualities and the particular ways they are organized and experienced perceptually (Silverman).

The aesthetic experience that we get from the world at large is different than the art-based aesthetic experience. It is important to recognize that we are not saying that the natural wonder experience is bad or lesser than the art world experience; we are saying it is different. What is different is the constructed nature of the art experience. The art experience is a type of aesthetic experience that also includes aspects, content, and context of humanness. When something is made by a human, people know that there is some level of commonality and/or communal experience.

Why aesthetics is only the beginning in analyzing an artwork

We are also aware that beyond sensory and formal properties, all artwork is informed by its specific time and place or the specific historical and cultural milieu it was created in (Silverman). For this reason people analyze artwork through not only aesthetics, but also, historical and cultural contexts. Think about what you bring to the viewing of a work of art. What has influenced the lens through which you analyze beauty?

How we engage in aesthetic analysis

Often the feelings or thoughts evoked as a result of contemplating an artwork are initially based primarily upon what is actually seen in the work. The first aspects of the artwork we respond to are its sensory properties, its formal properties, and its technical properties (Silverman). Color is an example of a sensory property. Color is considered a kind of form and how form is arranged is a formal property. What medium (e.g., painting, animation, etc.) the artwork is made of is an example of a technical property. These will be discussed further in the next module. As Dr. Silverman, of California State University explains, the sequence of questions in an aesthetic analysis could be: what do we actually see? How is what is seen organized? And, what emotions and ideas are evoked as a result of what has been observed?

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

What has influenced the lens through which you analyze beauty?

Works Cited

Corbett, J Rory. “What Is Beauty?: Royal Victoria Hospital, Wednesday 1st October 2008.” The Ulster Medical Journal , U.S. National Library of Medicine, May 2009, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2699193/ .

Ginsburg, Anna. “What Is Beauty? .” YouTube , CNN, 16 Mar. 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5utnc_yspSo .

Silverman, Ronald. Learning About Art: A Multicultural Approach. California State University, 2001. Web. 24, June 2008.

“What is Beauty?” YouTube , uploaded by Merav Richter, 16 Mar. 2.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

The nature of beauty is one of the most enduring and controversial themes in Western philosophy, and is—with the nature of art—one of the two fundamental issues in the history of philosophical aesthetics. Beauty has traditionally been counted among the ultimate values, with goodness, truth, and justice. It is a primary theme among ancient Greek, Hellenistic, and medieval philosophers, and was central to eighteenth and nineteenth-century thought, as represented in treatments by such thinkers as Shaftesbury, Hutcheson, Hume, Burke, Kant, Schiller, Hegel, Schopenhauer, Hanslick, and Santayana. By the beginning of the twentieth century, beauty was in decline as a subject of philosophical inquiry, and also as a primary goal of the arts. However, there was revived interest in beauty and critique of the concept by the 1980s, particularly within feminist philosophy.

This article will begin with a sketch of the debate over whether beauty is objective or subjective, which is perhaps the single most-prosecuted disagreement in the literature. It will proceed to set out some of the major approaches to or theories of beauty developed within Western philosophical and artistic traditions.

1. Objectivity and Subjectivity

2.1 the classical conception, 2.2 the idealist conception, 2.3 love and longing, 2.4 hedonist conceptions, 2.5 use and uselessness, 3.1 aristocracy and capital, 3.2 the feminist critique, 3.3 colonialism and race, 3.4 beauty and resistance, other internet resources, related entries.

Perhaps the most familiar basic issue in the theory of beauty is whether beauty is subjective—located ‘in the eye of the beholder’—or rather an objective feature of beautiful things. A pure version of either of these positions seems implausible, for reasons we will examine, and many attempts have been made to split the difference or incorporate insights of both subjectivist and objectivist accounts. Ancient and medieval accounts for the most part located beauty outside of anyone’s particular experiences. Nevertheless, that beauty is subjective was also a commonplace from the time of the sophists. By the eighteenth century, Hume could write as follows, expressing one ‘species of philosophy’:

Beauty is no quality in things themselves: It exists merely in the mind which contemplates them; and each mind perceives a different beauty. One person may even perceive deformity, where another is sensible of beauty; and every individual ought to acquiesce in his own sentiment, without pretending to regulate those of others. (Hume 1757, 136)

And Kant launches his discussion of the matter in The Critique of Judgment (the Third Critique) at least as emphatically:

The judgment of taste is therefore not a judgment of cognition, and is consequently not logical but aesthetical, by which we understand that whose determining ground can be no other than subjective . Every reference of representations, even that of sensations, may be objective (and then it signifies the real [element] of an empirical representation), save only the reference to the feeling of pleasure and pain, by which nothing in the object is signified, but through which there is a feeling in the subject as it is affected by the representation. (Kant 1790, section 1)

However, if beauty is entirely subjective—that is, if anything that anyone holds to be or experiences as beautiful is beautiful (as James Kirwan, for example, asserts)—then it seems that the word has no meaning, or that we are not communicating anything when we call something beautiful except perhaps an approving personal attitude. In addition, though different persons can of course differ in particular judgments, it is also obvious that our judgments coincide to a remarkable extent: it would be odd or perverse for any person to deny that a perfect rose or a dramatic sunset was beautiful. And it is possible actually to disagree and argue about whether something is beautiful, or to try to show someone that something is beautiful, or learn from someone else why it is.

On the other hand, it seems senseless to say that beauty has no connection to subjective response or that it is entirely objective. That would seem to entail, for example, that a world with no perceivers could be beautiful or ugly, or perhaps that beauty could be detected by scientific instruments. Even if it could be, beauty would seem to be connected to subjective response, and though we may argue about whether something is beautiful, the idea that one’s experiences of beauty might be disqualified as simply inaccurate or false might arouse puzzlement as well as hostility. We often regard other people’s taste, even when it differs from our own, as provisionally entitled to some respect, as we may not, for example, in cases of moral, political, or factual opinions. All plausible accounts of beauty connect it to a pleasurable or profound or loving response, even if they do not locate beauty purely in the eye of the beholder.

Until the eighteenth century, most philosophical accounts of beauty treated it as an objective quality: they located it in the beautiful object itself or in the qualities of that object. In De Veritate Religione , Augustine asks explicitly whether things are beautiful because they give delight, or whether they give delight because they are beautiful; he emphatically opts for the second (Augustine, 247). Plato’s account in the Symposium and Plotinus’s in the Enneads connect beauty to a response of love and desire, but locate beauty itself in the realm of the Forms, and the beauty of particular objects in their participation in the Form. Indeed, Plotinus’s account in one of its moments makes beauty a matter of what we might term ‘formedness’: having the definite shape characteristic of the kind of thing the object is.

We hold that all the loveliness of this world comes by communion in Ideal-Form. All shapelessness whose kind admits of pattern and form, as long as it remains outside of Reason and Idea, is ugly from that very isolation from the Divine-Thought. And this is the Absolute Ugly: an ugly thing is something that has not been entirely mastered by pattern, that is by Reason, the Matter not yielding at all points and in all respects to Ideal-Form. But where the Ideal-Form has entered, it has grouped and coordinated what from a diversity of parts was to become a unity: it has rallied confusion into co-operation: it has made the sum one harmonious coherence: for the Idea is a unity and what it moulds must come into unity as far as multiplicity may. (Plotinus, 22 [ Ennead I, 6])

In this account, beauty is at least as objective as any other concept, or indeed takes on a certain ontological priority as more real than particular Forms: it is a sort of Form of Forms.

Though Plato and Aristotle disagree on what beauty is, they both regard it as objective in the sense that it is not localized in the response of the beholder. The classical conception ( see below ) treats beauty as a matter of instantiating definite proportions or relations among parts, sometimes expressed in mathematical ratios, for example the ‘golden section.’ The sculpture known as ‘The Canon,’ by Polykleitos (fifth/fourth century BCE), was held up as a model of harmonious proportion to be emulated by students and masters alike: beauty could be reliably achieved by reproducing its objective proportions. Nevertheless, it is conventional in ancient treatments of the topic also to pay tribute to the pleasures of beauty, often described in quite ecstatic terms, as in Plotinus: “This is the spirit that Beauty must ever induce: wonderment and a delicious trouble, longing and love and a trembling that is all delight” (Plotinus 23, [ Ennead I, 3]).

At latest by the eighteenth century, however, and particularly in the British Isles, beauty was associated with pleasure in a somewhat different way: pleasure was held to be not the effect but the origin of beauty. This was influenced, for example, by Locke’s distinction between primary and secondary qualities. Locke and the other empiricists treated color (which is certainly one source or locus of beauty), for example, as a ‘phantasm’ of the mind, as a set of qualities dependent on subjective response, located in the perceiving mind rather than of the world outside the mind. Without perceivers of a certain sort, there would be no colors. One argument for this was the variation in color experiences between people. For example, some people are color-blind, and to a person with jaundice much of the world allegedly takes on a yellow cast. In addition, the same object is perceived as having different colors by the same the person under different conditions: at noon and midnight, for example. Such variations are conspicuous in experiences of beauty as well.

Nevertheless, eighteenth-century philosophers such as Hume and Kant perceived that something important was lost when beauty was treated merely as a subjective state. They saw, for example, that controversies often arise about the beauty of particular things, such as works of art and literature, and that in such controversies, reasons can sometimes be given and will sometimes be found convincing. They saw, as well, that if beauty is completely relative to individual experiencers, it ceases to be a paramount value, or even recognizable as a value at all across persons or societies.

Hume’s “Of the Standard of Taste” and Kant’s Critique Of Judgment attempt to find ways through what has been termed ‘the antinomy of taste.’ Taste is proverbially subjective: de gustibus non est disputandum (about taste there is no disputing). On the other hand, we do frequently dispute about matters of taste, and some persons are held up as exemplars of good taste or of tastelessness. Some people’s tastes appear vulgar or ostentatious, for example. Some people’s taste is too exquisitely refined, while that of others is crude, naive, or non-existent. Taste, that is, appears to be both subjective and objective: that is the antinomy.

Both Hume and Kant, as we have seen, begin by acknowledging that taste or the ability to detect or experience beauty is fundamentally subjective, that there is no standard of taste in the sense that the Canon was held to be, that if people did not experience certain kinds of pleasure, there would be no beauty. Both acknowledge that reasons can count, however, and that some tastes are better than others. In different ways, they both treat judgments of beauty neither precisely as purely subjective nor precisely as objective but, as we might put it, as inter-subjective or as having a social and cultural aspect, or as conceptually entailing an inter-subjective claim to validity.

Hume’s account focuses on the history and condition of the observer as he or she makes the judgment of taste. Our practices with regard to assessing people’s taste entail that judgments of taste that reflect idiosyncratic bias, ignorance, or superficiality are not as good as judgments that reflect wide-ranging acquaintance with various objects of judgment and are unaffected by arbitrary prejudices. Hume moves from considering what makes a thing beautiful to what makes a critic credible. “Strong sense, united to delicate sentiment, improved by practice, perfected by comparison, and cleared of all prejudice, can alone entitle critics to this valuable character; and the joint verdict of such, wherever they are to be found, is the true standard of taste and beauty” (“Of the Standard of Taste” 1757, 144).

Hume argues further that the verdicts of critics who possess those qualities tend to coincide, and approach unanimity in the long run, which accounts, for example, for the enduring veneration of the works of Homer or Milton. So the test of time, as assessed by the verdicts of the best critics, functions as something analogous to an objective standard. Though judgments of taste remain fundamentally subjective, and though certain contemporary works or objects may appear irremediably controversial, the long-run consensus of people who are in a good position to judge functions analogously to an objective standard and renders such standards unnecessary even if they could be identified. Though we cannot directly find a standard of beauty that sets out the qualities that a thing must possess in order to be beautiful, we can describe the qualities of a good critic or a tasteful person. Then the long-run consensus of such persons is the practical standard of taste and the means of justifying judgments about beauty.

Kant similarly concedes that taste is fundamentally subjective, that every judgment of beauty is based on a personal experience, and that such judgments vary from person to person.

By a principle of taste I mean a principle under the condition of which we could subsume the concept of the object, and thus infer, by means of a syllogism, that the object is beautiful. But that is absolutely impossible. For I must immediately feel the pleasure in the representation of the object, and of that I can be persuaded by no grounds of proof whatever. Although, as Hume says, all critics can reason more plausibly than cooks, yet the same fate awaits them. They cannot expect the determining ground of their judgment [to be derived] from the force of the proofs, but only from the reflection of the subject upon its own proper state of pleasure or pain. (Kant 1790, section 34)

But the claim that something is beautiful has more content merely than that it gives me pleasure. Something might please me for reasons entirely eccentric to myself: I might enjoy a bittersweet experience before a portrait of my grandmother, for example, or the architecture of a house might remind me of where I grew up. “No one cares about that,” says Kant (1790, section 7): no one begrudges me such experiences, but they make no claim to guide or correspond to the experiences of others.

By contrast, the judgment that something is beautiful, Kant argues, is a disinterested judgment. It does not respond to my idiosyncrasies, or at any rate if I am aware that it does, I will no longer take myself to be experiencing the beauty per se of the thing in question. Somewhat as in Hume—whose treatment Kant evidently had in mind—one must be unprejudiced to come to a genuine judgment of taste, and Kant gives that idea a very elaborate interpretation: the judgment must be made independently of the normal range of human desires—economic and sexual desires, for instance, which are examples of our ‘interests’ in this sense. If one is walking through a museum and admiring the paintings because they would be extremely expensive were they to come up for auction, for example, or wondering whether one could steal and fence them, one is not having an experience of the beauty of the paintings at all. One must focus on the form of the mental representation of the object for its own sake, as it is in itself. Kant summarizes this as the thought that insofar as one is having an experience of the beauty of something, one is indifferent to its existence. One takes pleasure, rather, in its sheer representation in one’s experience:

Now, when the question is whether something is beautiful, we do not want to know whether anything depends or can depend on the existence of the thing, either for myself or anyone else, but how we judge it by mere observation (intuition or reflection). … We easily see that, in saying it is beautiful , and in showing that I have taste, I am concerned, not with that in which I depend on the existence of the object, but with that which I make out of this representation in myself. Everyone must admit that a judgement about beauty, in which the least interest mingles, is very partial and is not a pure judgement of taste. (Kant 1790, section 2)

One important source of the concept of aesthetic disinterestedness is the Third Earl of Shaftesbury’s dialogue The Moralists , where the argument is framed in terms of a natural landscape: if you are looking at a beautiful valley primarily as a valuable real estate opportunity, you are not seeing it for its own sake, and cannot fully experience its beauty. If you are looking at a lovely woman and considering her as a possible sexual conquest, you are not able to experience her beauty in the fullest or purest sense; you are distracted from the form as represented in your experience. And Shaftesbury, too, localizes beauty to the representational capacity of the mind. (Shaftesbury 1738, 222)

For Kant, some beauties are dependent—relative to the sort of thing the object is—and others are free or absolute. A beautiful ox would be an ugly horse, but abstract textile designs, for example, may be beautiful without a reference group or “concept,” and flowers please whether or not we connect them to their practical purposes or functions in plant reproduction (Kant 1790, section 16). The idea in particular that free beauty is completely separated from practical use and that the experiencer of it is not concerned with the actual existence of the object leads Kant to conclude that absolute or free beauty is found in the form or design of the object, or as Clive Bell (1914) put it, in the arrangement of lines and colors (in the case of painting). By the time Bell writes in the early twentieth century, however, beauty is out of fashion in the arts, and Bell frames his view not in terms of beauty but in terms of a general formalist conception of aesthetic value.

Since in reaching a genuine judgment of taste one is aware that one is not responding to anything idiosyncratic in oneself, Kant asserts (1790, section 8), one will reach the conclusion that anyone similarly situated should have the same experience: that is, one will presume that there ought to be nothing to distinguish one person’s judgment from another’s (though in fact there may be). Built conceptually into the judgment of taste is the assertion that anyone similarly situated ought to have the same experience and reach the same judgment. Thus, built into judgments of taste is a ‘universalization’ somewhat analogous to the universalization that Kant associates with ethical judgments. In ethical judgments, however, the universalization is objective: if the judgment is true, then it is objectively the case that everyone ought to act on the maxim according to which one acts. In the case of aesthetic judgments, however, the judgment remains subjective, but necessarily contains the ‘demand’ that everyone should reach the same judgment. The judgment conceptually entails a claim to inter-subjective validity. This accounts for the fact that we do very often argue about judgments of taste, and that we find tastes that are different than our own defective.

The influence of this series of thoughts on philosophical aesthetics has been immense. One might mention related approaches taken by such figures as Schopenhauer (1818), Hanslick (1891), Bullough (1912), and Croce (1928), for example. A somewhat similar though more adamantly subjectivist line is taken by Santayana, who defines beauty as ‘objectified pleasure.’ The judgment of something that it is beautiful responds to the fact that it induces a certain sort of pleasure; but this pleasure is attributed to the object, as though the object itself were having subjective states.

We have now reached our definition of beauty, which, in the terms of our successive analysis and narrowing of the conception, is value positive, intrinsic, and objectified. Or, in less technical language, Beauty is pleasure regarded as the quality of a thing. … Beauty is a value, that is, it is not a perception of a matter of fact or of a relation: it is an emotion, an affection of our volitional and appreciative nature. An object cannot be beautiful if it can give pleasure to nobody: a beauty to which all men were forever indifferent is a contradiction in terms. … Beauty is therefore a positive value that is intrinsic; it is a pleasure. (Santayana 1896, 50–51)

It is much as though one were attributing malice to a balky object or device. The object causes certain frustrations and is then ascribed an agency or a kind of subjective agenda that would account for its causing those effects. Now though Santayana thought the experience of beauty could be profound or could even be the meaning of life, this account appears to make beauty a sort of mistake: one attributes subjective states (indeed, one’s own) to a thing which in many instances is not capable of having subjective states.

It is worth saying that Santayana’s treatment of the topic in The Sense of Beauty (1896) was the last major account offered in English for some time, possibly because, once beauty has been admitted to be entirely subjective, much less when it is held to rest on a sort of mistake, there seems little more to be said. What stuck from Hume’s and Kant’s treatments was the subjectivity, not the heroic attempts to temper it. If beauty is a subjective pleasure, it would seem to have no higher status than anything that entertains, amuses, or distracts; it seems odd or ridiculous to regard it as being comparable in importance to truth or justice, for example. And the twentieth century also abandoned beauty as the dominant goal of the arts, again in part because its trivialization in theory led artists to believe that they ought to pursue more urgent and more serious projects. More significantly, as we will see below, the political and economic associations of beauty with power tended to discredit the whole concept for much of the twentieth century. This decline is explored eloquently in Arthur Danto’s book The Abuse of Beauty (2003).

However, there was a revival of interest in beauty in something like the classical philosophical sense in both art and philosophy beginning in the 1990s, to some extent centered on the work of art critic Dave Hickey, who declared that “the issue of the 90s will be beauty” (see Hickey 1993), as well as feminist-oriented reconstruals or reappropriations of the concept (see Brand 2000, Irigaray 1993). Several theorists made new attempts to address the antinomy of taste. To some extent, such approaches echo G.E. Moore’s: “To say that a thing is beautiful is to say, not indeed that it is itself good, but that it is a necessary element in something which is: to prove that a thing is truly beautiful is to prove that a whole, to which it bears a particular relation as a part, is truly good” (Moore 1903, 201). One interpretation of this would be that what is fundamentally valuable is the situation in which the object and the person experiencing are both embedded; the value of beauty might include both features of the beautiful object and the pleasures of the experiencer.

Similarly, Crispin Sartwell in his book Six Names of Beauty (2004), attributes beauty neither exclusively to the subject nor to the object, but to the relation between them, and even more widely also to the situation or environment in which they are both embedded. He points out that when we attribute beauty to the night sky, for instance, we do not take ourselves simply to be reporting a state of pleasure in ourselves; we are turned outward toward it; we are celebrating the real world. On the other hand, if there were no perceivers capable of experiencing such things, there would be no beauty. Beauty, rather, emerges in situations in which subject and object are juxtaposed and connected.

Alexander Nehamas, in Only a Promise of Happiness (2007), characterizes beauty as an invitation to further experiences, a way that things invite us in, while also possibly fending us off. The beautiful object invites us to explore and interpret, but it also requires us to explore and interpret: beauty is not to be regarded as an instantaneously apprehensible feature of surface. And Nehamas, like Hume and Kant, though in another register, considers beauty to have an irreducibly social dimension. Beauty is something we share, or something we want to share, and shared experiences of beauty are particularly intense forms of communication. Thus, the experience of beauty is not primarily within the skull of the experiencer, but connects observers and objects such as works of art and literature in communities of appreciation.

Aesthetic judgment, I believe, never commands universal agreement, and neither a beautiful object nor a work of art ever engages a catholic community. Beauty creates smaller societies, no less important or serious because they are partial, and, from the point of view of its members, each one is orthodox—orthodox, however, without thinking of all others as heresies. … What is involved is less a matter of understanding and more a matter of hope, of establishing a community that centers around it—a community, to be sure, whose boundaries are constantly shifting and whose edges are never stable. (Nehamas 2007, 80–81)

2. Philosophical Conceptions of Beauty

Each of the views sketched below has many expressions, some of which may be incompatible with one another. In many or perhaps most of the actual formulations, elements of more than one such account are present. For example, Kant’s treatment of beauty in terms of disinterested pleasure has obvious elements of hedonism, while the ecstatic neo-Platonism of Plotinus includes not only the unity of the object, but also the fact that beauty calls out love or adoration. However, it is also worth remarking how divergent or even incompatible with one another many of these views are: for example, some philosophers associate beauty exclusively with use, others precisely with uselessness.

The art historian Heinrich Wölfflin gives a fundamental description of the classical conception of beauty, as embodied in Italian Renaissance painting and architecture:

The central idea of the Italian Renaissance is that of perfect proportion. In the human figure as in the edifice, this epoch strove to achieve the image of perfection at rest within itself. Every form developed to self-existent being, the whole freely co-ordinated: nothing but independently living parts…. In the system of a classic composition, the single parts, however firmly they may be rooted in the whole, maintain a certain independence. It is not the anarchy of primitive art: the part is conditioned by the whole, and yet does not cease to have its own life. For the spectator, that presupposes an articulation, a progress from part to part, which is a very different operation from perception as a whole. (Wölfflin 1932, 9–10, 15)

The classical conception is that beauty consists of an arrangement of integral parts into a coherent whole, according to proportion, harmony, symmetry, and similar notions. This is a primordial Western conception of beauty, and is embodied in classical and neo-classical architecture, sculpture, literature, and music wherever they appear. Aristotle says in the Poetics that “to be beautiful, a living creature, and every whole made up of parts, must … present a certain order in its arrangement of parts” (Aristotle, volume 2, 2322 [1450b34]). And in the Metaphysics : “The chief forms of beauty are order and symmetry and definiteness, which the mathematical sciences demonstrate in a special degree” (Aristotle, volume 2, 1705 [1078a36]). This view, as Aristotle implies, is sometimes boiled down to a mathematical formula, such as the golden section, but it need not be thought of in such strict terms. The conception is exemplified above all in such texts as Euclid’s Elements and such works of architecture as the Parthenon, and, again, by the Canon of the sculptor Polykleitos (late fifth/early fourth century BCE).

The Canon was not only a statue deigned to display perfect proportion, but a now-lost treatise on beauty. The physician Galen characterizes the text as specifying, for example, the proportions of “the finger to the finger, and of all the fingers to the metacarpus, and the wrist, and of all these to the forearm, and of the forearm to the arm, in fact of everything to everything…. For having taught us in that treatise all the symmetriae of the body, Polyclitus supported his treatise with a work, having made the statue of a man according to his treatise, and having called the statue itself, like the treatise, the Canon ” (quoted in Pollitt 1974, 15). It is important to note that the concept of ‘symmetry’ in classical texts is distinct from and richer than its current use to indicate bilateral mirroring. It also refers precisely to the sorts of harmonious and measurable proportions among the parts characteristic of objects that are beautiful in the classical sense, which carried also a moral weight. For example, in the Sophist (228c-e), Plato describes virtuous souls as symmetrical.

The ancient Roman architect Vitruvius epitomizes the classical conception in central, and extremely influential, formulations, both in its complexities and, appropriately enough, in its underlying unity:

Architecture consists of Order, which in Greek is called taxis , and arrangement, which the Greeks name diathesis , and of Proportion and Symmetry and Decor and Distribution which in the Greeks is called oeconomia . Order is the balanced adjustment of the details of the work separately, and as to the whole, the arrangement of the proportion with a view to a symmetrical result. Proportion implies a graceful semblance: the suitable display of details in their context. This is attained when the details of the work are of a height suitable to their breadth, of a breadth suitable to their length; in a word, when everything has a symmetrical correspondence. Symmetry also is the appropriate harmony arising out of the details of the work itself: the correspondence of each given detail to the form of the design as a whole. As in the human body, from cubit, foot, palm, inch and other small parts come the symmetric quality of eurhythmy. (Vitruvius, 26–27)

Aquinas, in a typically Aristotelian pluralist formulation, says that “There are three requirements for beauty. Firstly, integrity or perfection—for if something is impaired it is ugly. Then there is due proportion or consonance. And also clarity: whence things that are brightly coloured are called beautiful” ( Summa Theologica I, 39, 8).

Francis Hutcheson in the eighteenth century gives what may well be the clearest expression of the view: “What we call Beautiful in Objects, to speak in the Mathematical Style, seems to be in a compound Ratio of Uniformity and Variety; so that where the Uniformity of Bodys is equal, the Beauty is as the Variety; and where the Variety is equal, the Beauty is as the Uniformity” (Hutcheson 1725, 29). Indeed, proponents of the view often speak “in the Mathematical Style.” Hutcheson goes on to adduce mathematical formulae, and specifically the propositions of Euclid, as the most beautiful objects (in another echo of Aristotle), though he also rapturously praises nature, with its massive complexity underlain by universal physical laws as revealed, for example, by Newton. There is beauty, he says, “In the Knowledge of some great Principles, or universal Forces, from which innumerable Effects do flow. Such is Gravitation, in Sir Isaac Newton’s Scheme” (Hutcheson 1725, 38).

A very compelling series of refutations of and counter-examples to the idea that beauty can be a matter of any specific proportions between parts, and hence to the classical conception, is given by Edmund Burke in A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Beautiful and the Sublime :

Turning our eyes to the vegetable kingdom, we find nothing there so beautiful as flowers; but flowers are of every sort of shape, and every sort of disposition; they are turned and fashioned into an infinite variety of forms. … The rose is a large flower, yet it grows upon a small shrub; the flower of the apple is very small, and it grows upon a large tree; yet the rose and the apple blossom are both beautiful. … The swan, confessedly a beautiful bird, has a neck longer than the rest of its body, and but a very short tail; is this a beautiful proportion? we must allow that it is. But what shall we say of the peacock, who has comparatively but a short neck, with a tail longer than the neck and the rest of the body taken together? … There are some parts of the human body, that are observed to hold certain proportions to each other; but before it can be proved, that the efficient cause of beauty lies in these, it must be shewn, that wherever these are found exact, the person to whom they belong is beautiful. … For my part, I have at several times very carefully examined many of these proportions, and found them to hold very nearly, or altogether alike in many subjects, which were not only very different from one another, but where one has been very beautiful, and the other very remote from beauty. … You may assign any proportions you please to every part of the of the human body; and I undertake, that a painter shall observe them all, and notwithstanding produce, if he pleases, a very ugly figure. (Burke 1757, 84–89)

There are many ways to interpret Plato’s relation to classical aesthetics. The political system sketched in the Republic characterizes justice in terms of the relation of part and whole. But Plato was also no doubt a dissident in classical culture, and the account of beauty that is expressed specifically in the Symposium —perhaps the key Socratic text for neo-Platonism and for the idealist conception of beauty—expresses an aspiration toward beauty as perfect unity.

In the midst of a drinking party, Socrates recounts the teachings of his instructress, one Diotima, on matters of love. She connects the experience of beauty to the erotic or the desire to reproduce (Plato, 558–59 [ Symposium 206c–207e]). But the desire to reproduce is associated in turn with a desire for the immortal or eternal: “And why all this longing for propagation? Because this is the one deathless and eternal element in our mortality. And since we have agreed that the lover longs for the good to be his own forever, it follows that we are bound to long for immortality as well as for the good—which is to say that Love is a longing for immortality” (Plato, 559, [ Symposium 206e–207a]). What follows is, if not classical, at any rate classic:

The candidate for this initiation cannot, if his efforts are to be rewarded, begin too early to devote himself to the beauties of the body. First of all, if his preceptor instructs him as he should, he will fall in love with the beauty of one individual body, so that his passion may give life to noble discourse. Next he must consider how nearly related the beauty of any one body is to the beauty of any other, and he will see that if he is to devote himself to loveliness of form it will be absurd to deny that the beauty of each and every body is the same. Having reached this point, he must set himself to be the lover of every lovely body, and bring his passion for the one into due proportion by deeming it of little or no importance. Next he must grasp that the beauties of the body are as nothing to the beauties of the soul, so that wherever he meets with spiritual loveliness, even in the husk of an unlovely body, he will find it beautiful enough to fall in love with and cherish—and beautiful enough to quicken in his heart a longing for such discourse as tends toward the building of a noble nature. And from this he will be led to contemplate the beauty of laws and institutions. And when he discovers how every kind of beauty is akin to every other he will conclude that the beauty of the body is not, after all, of so great moment. … And so, when his prescribed devotion to boyish beauties has carried our candidate so far that the universal beauty dawns upon his inward sight, he is almost within reach of the final revelation. … Starting from individual beauties, the quest for universal beauty must find him mounting the heavenly ladder, stepping from rung to rung—that is, from one to two, and from two to every lovely body, and from bodily beauty to the beauty of institutions, from institutions to learning, and from learning in general to the special lore that pertains to nothing but the beautiful itself—until at last he comes to know what beauty is. And if, my dear Socrates, Diotima went on, man’s life is ever worth living, it is when he has attained this vision of the very soul of beauty. (Plato, 561–63 [ Symposium 210a–211d])

Beauty here is conceived—perhaps explicitly in contrast to the classical aesthetics of integral parts and coherent whole—as perfect unity, or indeed as the principle of unity itself.

Plotinus, as we have already seen, comes close to equating beauty with formedness per se: it is the source of unity among disparate things, and it is itself perfect unity. Plotinus specifically attacks what we have called the classical conception of beauty:

Almost everyone declares that the symmetry of parts towards each other and towards a whole, with, besides, a certain charm of colour, constitutes the beauty recognized by the eye, that in visible things, as indeed in all else, universally, the beautiful thing is essentially symmetrical, patterned. But think what this means. Only a compound can be beautiful, never anything devoid of parts; and only a whole; the several parts will have beauty, not in themselves, but only as working together to give a comely total. Yet beauty in an aggregate demands beauty in details; it cannot be constructed out of ugliness; its law must run throughout. All the loveliness of colour and even the light of the sun, being devoid of parts and so not beautiful by symmetry, must be ruled out of the realm of beauty. And how comes gold to be a beautiful thing? And lightning by night, and the stars, why are these so fair? In sounds also the simple must be proscribed, though often in a whole noble composition each several tone is delicious in itself. (Plotinus, 21 [ Ennead I,6])

Plotinus declares that fire is the most beautiful physical thing, “making ever upwards, the subtlest and sprightliest of all bodies, as very near to the unembodied. … Hence the splendour of its light, the splendour that belongs to the Idea” (Plotinus, 22 [ Ennead I,3]). For Plotinus as for Plato, all multiplicity must be immolated finally into unity, and all roads of inquiry and experience lead toward the Good/Beautiful/True/Divine.

This gave rise to a basically mystical vision of the beauty of God that, as Umberto Eco has argued, persisted alongside an anti-aesthetic asceticism throughout the Middle Ages: a delight in profusion that finally merges into a single spiritual unity. In the sixth century, Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite characterized the whole of creation as yearning toward God; the universe is called into being by love of God as beauty (Pseudo-Dionysius, 4.7; see Kirwan 1999, 29). Sensual/aesthetic pleasures could be considered the expressions of the immense, beautiful profusion of God and our ravishment thereby. Eco quotes Suger, Abbot of St Denis in the twelfth century, describing a richly-appointed church:

Thus, when—out of my delight in the beauty of the house of God—the loveliness of the many-colored gems has called me away from external cares, and worthy meditation has induced me to reflect, transferring that which is material to that which is immaterial, on the diversity of the sacred virtues: then it seems to me that I see myself dwelling, as it were, in some strange region of the universe which neither exists entirely in the slime of the earth nor entirely in the purity of Heaven; and that, by the grace of God, I can be transported from this inferior to that higher world in an anagogical manner. (Eco 1959, 14)

This conception has had many expressions in the modern era, including in such figures as Shaftesbury, Schiller, and Hegel, according to whom the aesthetic or the experience of art and beauty is a primary bridge (or to use the Platonic image, stairway or ladder) between the material and the spiritual. For Shaftesbury, there are three levels of beauty: what God makes (nature); what human beings make from nature or what is transformed by human intelligence (art, for example); and finally, the intelligence that makes even these artists (that is, God). Shaftesbury’s character Theocles describes “the third order of beauty,”

which forms not only such as we call mere forms but even the forms which form. For we ourselves are notable architects in matter, and can show lifeless bodies brought into form, and fashioned by our own hands, but that which fashions even minds themselves, contains in itself all the beauties fashioned by those minds, and is consequently the principle, source, and fountain of all beauty. … Whatever appears in our second order of forms, or whatever is derived or produced from thence, all this is eminently, principally, and originally in this last order of supreme and sovereign beauty. … Thus architecture, music, and all which is of human invention, resolves itself into this last order. (Shaftesbury 1738, 228–29)

Schiller’s expression of a similar series of thoughts was fundamentally influential on the conceptions of beauty developed within German Idealism:

The pre-rational concept of Beauty, if such a thing be adduced, can be drawn from no actual case—rather does itself correct and guide our judgement concerning every actual case; it must therefore be sought along the path of abstraction, and it can be inferred simply from the possibility of a nature that is both sensuous and rational; in a word, Beauty must be exhibited as a necessary condition of humanity. Beauty … makes of man a whole, complete in himself. (1795, 59–60, 86)

For Schiller, beauty or play or art (he uses the words, rather cavalierly, almost interchangeably) performs the process of integrating or rendering compatible the natural and the spiritual, or the sensuous and the rational: only in such a state of integration are we—who exist simultaneously on both these levels—free. This is quite similar to Plato’s ‘ladder’: beauty as a way to ascend to the abstract or spiritual. But Schiller—though this is at times unclear—is more concerned with integrating the realms of nature and spirit than with transcending the level of physical reality entirely, a la Plato. It is beauty and art that performs this integration.

In this and in other ways—including in the tripartite dialectical structure of his account—Schiller strikingly anticipates Hegel, who writes as follows.

The philosophical Concept of the beautiful, to indicate its true nature at least in a preliminary way, must contain, reconciled within itself, both the extremes which have been mentioned [the ideal and the empirical] because it unites metaphysical universality with real particularity. (Hegel 1835, 22)

Beauty, we might say, or artistic beauty at any rate, is a route from the sensuous and particular to the Absolute and to freedom, from finitude to the infinite, formulations that—while they are influenced by Schiller—strikingly recall Shaftesbury, Plotinus, and Plato.

Hegel, who associates beauty and art with mind and spirit, holds with Shaftesbury that the beauty of art is higher than the beauty of nature, on the grounds that, as Hegel puts it, “the beauty of art is born of the spirit and born again ” (Hegel 1835, 2). That is, the natural world is born of God, but the beauty of art transforms that material again by the spirit of the artist. This idea reaches is apogee in Benedetto Croce, who very nearly denies that nature can ever be beautiful, or at any rate asserts that the beauty of nature is a reflection of the beauty of art. “The real meaning of ‘natural beauty’ is that certain persons, things, places are, by the effect which they exert upon one, comparable with poetry, painting, sculpture, and the other arts” (Croce 1928, 230).

Edmund Burke, expressing an ancient tradition, writes that, “by beauty I mean, that quality or those qualities in bodies, by which they cause love, or some passion similar to it” (Burke 1757, 83). As we have seen, in almost all treatments of beauty, even the most apparently object or objectively-oriented, there is a moment in which the subjective qualities of the experience of beauty are emphasized: rhapsodically, perhaps, or in terms of pleasure or ataraxia , as in Schopenhauer. For example, we have already seen Plotinus, for whom beauty is certainly not subjective, describe the experience of beauty ecstatically. In the idealist tradition, the human soul, as it were, recognizes in beauty its true origin and destiny. Among the Greeks, the connection of beauty with love is proverbial from early myth, and Aphrodite the goddess of love won the Judgment of Paris by promising Paris the most beautiful woman in the world.

There is an historical connection between idealist accounts of beauty and those that connect it to love and longing, though there would seem to be no entailment either way. We have Sappho’s famous fragment 16: “Some say thronging cavalry, some say foot soldiers, others call a fleet the most beautiful sights the dark world offers, but I say it’s whatever you love best” (Sappho, 16). (Indeed, at Phaedrus 236c, Socrates appears to defer to “the fair Sappho” as having had greater insight than himself on love [Plato, 483].)

Plato’s discussions of beauty in the Symposium and the Phaedrus occur in the context of the theme of erotic love. In the former, love is portrayed as the ‘child’ of poverty and plenty. “Nor is he delicate and lovely as most of us believe, but harsh and arid, barefoot and homeless” (Plato, 556 [Symposium 203b–d]). Love is portrayed as a lack or absence that seeks its own fulfillment in beauty: a picture of mortality as an infinite longing. Love is always in a state of lack and hence of desire: the desire to possess the beautiful. Then if this state of infinite longing could be trained on the truth, we would have a path to wisdom. The basic idea has been recovered many times, for example by the Romantics. It fueled the cult of idealized or courtly love through the Middle Ages, in which the beloved became a symbol of the infinite.

Recent work on the theory of beauty has revived this idea, and turning away from pleasure has turned toward love or longing (which are not necessarily entirely pleasurable experiences) as the experiential correlate of beauty. Both Sartwell and Nehamas use Sappho’s fragment 16 as an epigraph. Sartwell defines beauty as “the object of longing” and characterizes longing as intense and unfulfilled desire. He calls it a fundamental condition of a finite being in time, where we are always in the process of losing whatever we have, and are thus irremediably in a state of longing. And Nehamas writes that “I think of beauty as the emblem of what we lack, the mark of an art that speaks to our desire. … Beautiful things don’t stand aloof, but direct our attention and our desire to everything else we must learn or acquire in order to understand and possess, and they quicken the sense of life, giving it new shape and direction” (Nehamas 2007, 77).

Thinkers of the 18 th century—many of them oriented toward empiricism—accounted for beauty in terms of pleasure. The Italian historian Ludovico Antonio Muratori, for example, in quite a typical formulation, says that “By beautiful we generally understand whatever, when seen, heard, or understood, delights, pleases, and ravishes us by causing within us agreeable sensations” (see Carritt 1931, 60). In Hutcheson it is not clear whether we ought to conceive beauty primarily in terms of classical formal elements or in terms of the viewer’s pleasurable response. He begins the Inquiry Into the Original of Our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue with a discussion of pleasure. And he appears to assert that objects which instantiate his ‘compound ratio of uniformity and variety’ are peculiarly or necessarily capable of producing pleasure:

The only Pleasure of sense, which our Philosophers seem to consider, is that which accompanys the simple Ideas of Sensation; But there are vastly greater Pleasures in those complex Ideas of objects, which obtain the Names of Beautiful, Regular, Harmonious. Thus every one acknowledges he is more delighted with a fine Face, a just Picture, than with the View of any one Colour, were it as strong and lively as possible; and more pleased with a Prospect of the Sun arising among settled Clouds, and colouring their Edges, with a starry Hemisphere, a fine Landskip, a regular Building, than with a clear blue Sky, a smooth Sea, or a large open Plain, not diversify’d by Woods, Hills, Waters, Buildings: And yet even these latter Appearances are not quite simple. So in Musick, the Pleasure of fine Composition is incomparably greater than that of any one Note, how sweet, full, or swelling soever. (Hutcheson 1725, 22)

When Hutcheson then goes on to describe ‘original or absolute beauty,’ he does it, as we have seen, in terms of the qualities of the beautiful thing (a “compound ratio” of uniformity and variety), and yet throughout, he insists that beauty is centered in the human experience of pleasure. But of course the idea of pleasure could come apart from Hutcheson’s particular aesthetic preferences, which are poised precisely opposite Plotinus’s, for example. That we find pleasure in a symmetrical rather than an asymmetrical building (if we do) is contingent. But that beauty is connected to pleasure appears, according to Hutcheson, to be necessary, and the pleasure which is the locus of beauty itself has ideas rather than things as its objects.

Hume writes in a similar vein in the Treatise of Human Nature :

Beauty is such an order and construction of parts as, either by the primary constitution of our nature, by custom, or by caprice, is fitted to give a pleasure and satisfaction to the soul. … Pleasure and pain, therefore, are not only necessary attendants of beauty and deformity, but constitute their very essence. (Hume 1740, 299)

Though this appears ambiguous as between locating the beauty in the pleasure or in the impression or idea that causes it, Hume is soon talking about the ‘sentiment of beauty,’ where sentiment is, roughly, a pleasurable or painful response to impressions or ideas, though the experience of beauty is a matter of cultivated or delicate pleasures. Indeed, by the time of Kant’s Third Critique and after that for perhaps two centuries, the direct connection of beauty to pleasure is taken as a commonplace, to the point where thinkers are frequently identifying beauty as a certain sort of pleasure. Santayana, for example, as we have seen, while still gesturing in the direction of the object or experience that causes pleasure, emphatically identifies beauty as a certain sort of pleasure.

One result of this approach to beauty—or perhaps an extreme expression of this orientation—is the assertion of the positivists that words such as ‘beauty’ are meaningless or without cognitive content, or are mere expressions of subjective approval. Hume and Kant were no sooner declaring beauty to be a matter of sentiment or pleasure and therefore to be subjective than they were trying to ameliorate the sting, largely by emphasizing critical consensus. But once this fundamental admission is made, any consensus seems contingent. Another way to formulate this is that it appears to certain thinkers after Hume and Kant that there can be no reasons to prefer the consensus to a counter-consensus assessment. A.J. Ayer writes:

Such aesthetic words as ‘beautiful’ and ‘hideous’ are employed … not to make statements of fact, but simply to express certain feelings and evoke a certain response. It follows…that there is no sense attributing objective validity to aesthetic judgments, and no possibility of arguing about questions of value in aesthetics. (Ayer 1952, 113)

All meaningful claims either concern the meaning of terms or are empirical, in which case they are meaningful because observations could confirm or disconfirm them. ‘That song is beautiful’ has neither status, and hence has no empirical or conceptual content. It merely expresses a positive attitude of a particular viewer; it is an expression of pleasure, like a satisfied sigh. The question of beauty is not a genuine question, and we can safely leave it behind or alone. Most twentieth-century philosophers did just that.

Philosophers in the Kantian tradition identify the experience of beauty with disinterested pleasure, psychical distance, and the like, and contrast the aesthetic with the practical. “ Taste is the faculty of judging an object or mode of representing it by an entirely disinterested satisfaction or dissatisfaction. The object of such satisfaction is called beautiful ” (Kant 1790, 45). Edward Bullough distinguishes the beautiful from the merely agreeable on the grounds that the former requires a distance from practical concerns: “Distance is produced in the first instance by putting the phenomenon, so to speak, out of gear with our practical, actual self; by allowing it to stand outside the context of our personal needs and ends” (Bullough 1912, 244).

On the other hand, many philosophers have gone in the opposite direction and have identified beauty with suitedness to use. ‘Beauty’ is perhaps one of the few terms that could plausibly sustain such entirely opposed interpretations.

According to Diogenes Laertius, the ancient hedonist Aristippus of Cyrene took a rather direct approach.

Is not then, also, a beautiful woman useful in proportion as she is beautiful; and a boy and a youth useful in proportion to their beauty? Well then, a handsome boy and a handsome youth must be useful exactly in proportion as they are handsome. Now the use of beauty is, to be embraced. If then a man embraces a woman just as it is useful that he should, he does not do wrong; nor, again, will he be doing wrong in employing beauty for the purposes for which it is useful. (Diogenes Laertius, 94)

In some ways, Aristippus is portrayed parodically: as the very worst of the sophists, though supposedly a follower of Socrates. And yet the idea of beauty as suitedness to use finds expression in a number of thinkers. Xenophon’s Memorabilia puts the view in the mouth of Socrates, with Aristippus as interlocutor:

Socrates : In short everything which we use is considered both good and beautiful from the same point of view, namely its use. Aristippus : Why then, is a dung-basket a beautiful thing? Socrates : Of course it is, and a golden shield is ugly, if the one be beautifully fitted to its purpose and the other ill. (Xenophon, Book III, viii)

Berkeley expresses a similar view in his dialogue Alciphron , though he begins with the hedonist conception: “Every one knows that beauty is what pleases” (Berkeley 1732, 174; see Carritt 1931, 75). But it pleases for reasons of usefulness. Thus, as Xenophon suggests, on this view, things are beautiful only in relation to the uses for which they are intended or to which they are properly applied. The proper proportions of an object depend on what kind of object it is and, again, a beautiful car might make an ugly tractor. “The parts, therefore, in true proportions, must be so related, and adjusted to one another, as they may best conspire to the use and operation of the whole” (Berkeley 1732, 174–75; see Carritt 1931, 76). One result of this is that, though beauty remains tied to pleasure, it is not an immediate sensible experience. It essentially requires intellection and practical activity: one has to know the use of a thing and assess its suitedness to that use.

This treatment of beauty is often used, for example, to criticize the distinction between fine art and craft, and it avoids sheer philistinism by enriching the concept of ‘use,’ so that it might encompass not only performing a practical task, but performing it especially well or with an especial satisfaction. Ananda Coomaraswamy, the Ceylonese-British scholar of Indian and European medieval arts, adds that a beautiful work of art or craft expresses as well as serves its purpose.

A cathedral is not as such more beautiful than an airplane, … a hymn than a mathematical equation. … A well-made sword is not less beautiful than a well-made scalpel, though one is used to slay, the other to heal. Works of art are only good or bad, beautiful or ugly in themselves, to the extent that they are or are not well and truly made, that is, do or do not express, or do or do not serve their purpose. (Coomaraswamy 1977, 75)

Roger Scruton, in his book Beauty (2009) returns to a modified Kantianism with regard to both beauty and sublimity, enriched by many and varied examples. “We call something beautiful,” writes Scruton, “when we gain pleasure from contemplating it as an individual object, for its own sake, and in its presented form ” (Scruton 2009, 26). Despite the Kantian framework, Scruton, like Sartwell and Nehamas, throws the subjective/objective distinction into question. He compares experiencing a beautiful thing to a kiss. To kiss someone that one loves is not merely to place one body part on another, “but to touch the other person in his very self. Hence the kiss is compromising – it is a move from one self toward another, and a summoning of the other into the surface of his being” (Scruton 2009, 48). This, Scruton says, is a profound pleasure.

3. The Politics of Beauty

Kissing sounds nice, but some kisses are coerced, some pleasures obtained at a cost to other people. The political associations of beauty over the last few centuries have been remarkably various and remarkably problematic, particularly in connection with race and gender, but in other aspects as well. This perhaps helps account for the neglect of the issue in early-to-mid twentieth-century philosophy as well as its growth late in the century as an issue in social justice movements, and subsequently in social-justice oriented philosophy.

The French revolutionaries of 1789 associated beauty with the French aristocracy and with the Rococo style of the French royal family, as in the paintings of Fragonard: hedonist expressions of wealth and decadence, every inch filled with decorative motifs. Beauty itself became subject to a moral and political critique, or even to direct destruction, with political motivations (see Levey 1985). And by the early 20th century, beauty was particularly associated with capitalism (ironically enough, considering the ugliness of the poverty and environmental destruction it often induced). At times even great art appeared to be dedicated mainly to furnishing the homes of rich people, with the effect of concealing the suffering they were inflicting. In response, many anti-capitalists, including many Marxists, appeared to repudiate beauty entirely. And in the aesthetic politics of Nazism, reflected for example in the films of Leni Riefenstahl, the association of beauty and right wing politics was sealed to devastating effect (see Spotts 2003).

Early on in his authorship, Karl Marx could hint that the experience of beauty distinguishes human beings from all other animals. An animal “produces only under the dominion of immediate physical need, whilst man produces even when he is free from physical need and only truly produces in freedom therefrom. Man therefore also forms objects in accordance with the laws of beauty” (Marx 1844, 76). But later Marx appeared to conceive beauty as “superstructure” or “ideology” disguising the material conditions of production. Perhaps, however, he also anticipated the emergence of new beauties, available to all both as makers and appreciators, in socialism.

Capitalism, of course, uses beauty – at times with complete self-consciousness – to manipulate people into buying things. Many Marxists believed that the arts must be turned from providing fripperies to the privileged or advertising that helps make them wealthier to showing the dark realities of capitalism (as in the American Ashcan school, for example), and articulating an inspiring Communist future. Stalinist socialist realism consciously repudiates the aestheticized beauties of post-impressionist and abstract painting, for example. It has urgent social tasks to perform (see Bown and Lanfranconi 2012). But the critique tended at times to generalize to all sorts of beauty: as luxury, as seduction, as disguise and oppression. The artist Max Ernst (1891–1976), having survived the First World War, wrote this about the radical artists of the early century: “To us, Dada was above all a moral reaction. Our rage aimed at total subversion. A horrible futile war had robbed us of five years of our existence. We had experienced the collapse into ridicule and shame of everything represented to us as just, true, and beautiful. My works of that period were not meant to attract, but to make people scream” (quoted in Danto 2003, 49).

Theodor Adorno, in his book Aesthetic Theory , wrote that one symptom of oppression is that oppressed groups and cultures are regarded as uncouth, dirty, ragged; in short, that poverty is ugly. It is art’s obligation, he wrote, to show this ugliness, imposed on people by an unjust system, clearly and without flinching, rather to distract people by beauty from the brutal realities of capitalism. “Art must take up the cause of what is proscribed as ugly, though no longer to integrate or mitigate it or reconcile it with its own existence,” Adorno wrote. “Rather, in the ugly, art must denounce the world that creates and reproduces the ugly in its own image” (Adorno 1970, 48–9).

The political entanglements of beauty tend to throw into question various of the traditional theories. For example, the purity and transcendence associated with the essence of beauty in the realm of the Forms seems irrelevant, as beauty shows its centrality to politics and commerce, to concrete dimensions of oppression. The austere formalism of the classical conception, for example, seems neither here nor there when the building process is brutally exploitative.

As we have seen, the association of beauty with the erotic is proverbial from Sappho and is emphasized relentlessly by figures such as Burke and Nehamas. But the erotic is not a neutral or universal site, and we need to ask whose sexuality is in play in the history of beauty, with what effects. This history, particularly in the West and as many feminist theorists and historians have emphasized, is associated with the objectification and exploitation of women. Feminists beginning in the 19th century gave fundamental critiques of the use of beauty as a set of norms to control women’s bodies or to constrain their self-presentation and even their self-image in profound and disabling ways (see Wollstonecraft 1792, Grimké 1837).

In patriarchal society, as Catherine MacKinnon puts it, the content of sexuality “is the gaze that constructs women as objects for male pleasure. I draw on pornography for its form and content,” she continues, describing her treatment of the subject, “for the gaze that eroticizes the despised, the demeaned, the accessible, the there-to-be-used, the servile, the child-like, the passive, and the animal. That is the content of sexuality that defines gender female in this culture, and visual thingification is its method” (MacKinnon 1987, 53–4). Laura Mulvey, in “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” reaches one variety of radical critique and conclusion: “It is said that analyzing pleasure, or beauty, destroys it. That is the intention of this article” (Mulvey 1975, 60).

Mulvey’s psychoanalytic treatment was focused on the scopophilia (a Freudian term denoting neurotic sexual pleasure configured around looking) of Hollywood films, in which men appeared as protagonists, and women as decorative or sexual objects for the pleasure of the male characters and male audience-members. She locates beauty “at the heart of our oppression.” And she appears to have a hedonist conception of it: beauty engenders pleasure. But some pleasures, like some kisses, are sadistic or exploitative at the individual and at the societal level. Art historians such as Linda Nochlin (1988) and Griselda Pollock (1987) brought such insights to bear on the history of painting, for example, where the scopophilia is all too evident in famous nudes such as Titian’s Venus of Urbino or Velazquez’s Rokeby Venus , which a feminist slashed with knife in 1914 because “she didn’t like the way men gawked at it”.