MINI REVIEW article

Professional development of teacher trainers: the role of teaching skills and knowledge.

- School of Marxism, Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, China

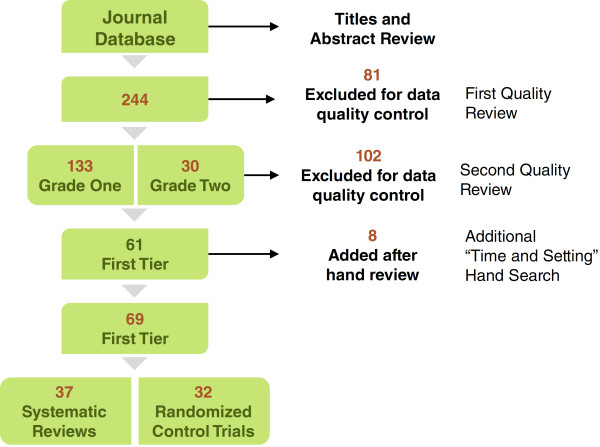

Since the 1990s, the essential function of teacher trainers in academic courses has gradually attained more attention from scholars. Also, the teacher trainers’ professional development has acquired worldwide attraction following the concept that teacher trainers are deeply liable for educator education quality. The present mini-review of literature indicates that while teacher trainers have several complicated functions, they obtain the least preparation or opportunities for professional development to perform such functions. Consequently, they require getting the related knowledge and skills after accepting the role of teacher trainers. Besides numerous aspects affecting teacher trainers’ professional development, teaching skills, and knowledge have important functions that are at the center of attention in this mini-review of literature. In brief, several implications are presented for the instructional addressees.

Introduction

The important function of pre-service and in-service educator training platforms in providing educators is a controversial topic in educator training literature ( Smith, 2010 ). Within such programs, educators take the primary measures toward being specialists, achieve higher confidence in their education, and expand the scope of their knowledge reservoir ( Akbari and Dadvand, 2011 ). The teaching job demands ongoing education and growth since it is directly involved with human capital ( Harris and Jones, 2010 ). Educator quality needs educators to have the knowledge and skills in the field they instruct. Educators obtain these skills during their program ( Blank and Alas, 2010 ; Butler, 2015 ) through Professional Development (PD) which has a vital function in an educator’s future profess and development. Educators require chances to upsurge their knowledge and skills, maintain their incentives, and expand their cooperation with others in their careers ( Margolis, 2008 ). In the history of academia, no attempt at advancement has ever been effective and successful without carefully arranged and well-executed PD actions planned to improve teachers’ knowledge and skills ( Guskey, 2009 ).

The literature on learning has taken part in discussions for years on whether educator standard is the most significant school factor affecting learners’ success and enhancing the standard of the school ( Kang et al., 2013 ; Macia and García, 2016 ). Similarly, academic leaders, theorists, and scholars have emphasized how to best improve the standard of teaching to enhance learners’ education and success. Each year, nations spend billions of dollars on enhancing the standard of their educators’ skills and eligibilities by building their chances for professional development (PD) ( DeMonte, 2013 ). The standard of teacher education has been known as a central issue influencing the standard of teaching and learners’ success. Therefore, there has been increasing attention to teacher trainers: their individuality, skills, functions, and PD ( Loughran, 2014 ; Lunenberg et al., 2014 ).

Until recently, teacher trainers were characterized as concealed experts who are not always presented with the help and challenge they require, for instance concerning their learning and PD ( Livingston, 2014 ). Teacher trainers are among those who are engaged in the learning of learners, educators, and ongoing PD of in-service educators ( Czerniawski et al., 2017 ). Nonetheless, in the last 20 years, scholars, and teacher trainers themselves began to growingly notice the particular quality of their jobs, and so, they have begun to emphasize teacher trainers’ PD ( Berry, 2016 ; Lunenberg et al., 2017 ).

The teacher trainer is considered the most affecting factor when preparing better-organized educators ( Snoek et al., 2010 ), and their function can be explained as a facilitator who links the distance among highpoint level policymakers at the countrywide and/or nearby area. Consequently, they must satisfy the knowledge and function criteria set by employing political organizations and practically display those criteria ( Lunenberg et al., 2017 ). Educator trainers have numerous roles, which need PD and learning ( Swennen et al., 2010 ; Lunenberg et al., 2014 ) and professional educators should be able to grow knowledge in making well-informed choices regarding activities with approaches that can respond to complicated conditions according to complicated knowledge and reflection ( Loughran and Hamilton, 2016 ).

Classes today have altered with time due to higher levels of diversities and have become more intricate as a result of technology and the generational gap ( Gomes et al., 2015 ; Sonmark et al., 2017 ). Thus, an educational space is a place for learners to attain novel knowledge and skills and a workplace where educators can study and enhance their careers. And EFL educators necessary need to gain the most recent education knowledge and skills within the milieu of English language education and learning to enhance the learners’ development and growth and perform the international necessities of the universal time ( Zhiyong et al., 2020 ). To comprehend and assist educator trainers’ PD in the best way, it’s vital to understand what skills and knowledge they require and how they efficiently obtain such skills and knowledge during their profession ( MacPhail et al., 2019 ).

Just as the excellence of teachers influences the learning results of students, the eminence of teacher educators impacts the quality of teachers ( Darling-Hammond, 2010 ). The study was done by Buchberger et al. (2000) regarding the growth and the future of teacher education, in which the authors declared that development in the proficiencies of teacher educators may well contribute to significant growth in the quality of teachers. Despite their crucial function in the training and assisting of future educators, research literature and documents on who educator trainers are and how they professionally influence education are not examined until recently ( Czerniawski et al., 2017 ). Overall, presently, there appears to be an agreement that teacher educators are a significant element in deciding the standard of educators, who, in turn, are a significant element in deciding the standard of the education of their learners at different levels of education ( Murray and Kosnik, 2011 ). The professional development literature review indicated that educators’ PD activities mostly reveal their restrained obtaining of knowledge and skills. The issue is caused by the providers’ inability to design PD applications that address the educators’ needs ( Darling-Hammond, 2010 ). Teacher trainers are sometimes held accountable for their vagueness in determining the action purpose and theory in their PD program, however, educators in some other cases are even unwilling to be responsible for their own PD ( Daniel and Peercy, 2014 ). Nonetheless, based on the literature when perspectives from educators merge with that of educator trainers, it can probably ascertain congruence between the contents of educator training and the educators’ needs in addition to higher facilitation of educators’ PD ( He et al., 2011 ). However, based on the researcher’s knowledge, on the one hand, not enough consideration has been paid to teacher educator studies ( Lunenberg et al., 2014 ; Van der Klink et al., 2017 ) and on the other hand, there is little information regarding educator trainers and their PD: how they are educated and taught and what leads to a proper teacher trainer ( Villegas-Reimers, 2003 ; Lin, 2013 ).

Review of the Literature

Professional development of teacher trainers.

Professional development (PD) has been characterized as an inner cycle in which experts are involved in a formal or informal model embedded in the precarious assessment of expert practice ( Smith, 2010 ). Professional development alludes to these types of elevations in knowledge and skills. It is considered the foundation of expert practice in all careers. Villegas-Reimers (2003) argued that the PD of teacher trainers is not famous in comparison with educator PD. Research has suggested that educator PD is one of the impactful elements in learners’ education and success ( Villegas-Reimers, 2003 ; Darling-Hammond, 2010 ). Professional development is specifically essential for novice educators who must become accustomed to the standards of their careers. Certainly, as stated by Futernick (2007) , educators who quit this job regularly state the absence of PD as one of the reasons. PD can also enable educators’ exposure to growing leadership roles. This is particularly crucial to educators in the final level of their profession, whose devotion and inspiration may be falling ( Day and Gu, 2007 ).

Teacher trainers’ PD has been characterized as formal educational and expert progress classes to prepare teachers with pertinent and updated knowledge and capabilities crucial to standard improvement ( Sierra-Piedrahita, 2007 ). In addition, teacher trainers’ PD has been explained as the growth of a question as a position, which alludes to the cycle of ongoing and structured questions wherein they contemplate their own and other’s presumptions and develop local and public knowledge that is suitable for the altering settings in which they work ( Loughran, 2014 ). The aim of teacher educator PD is four-fold: enhancing teacher education, satisfying outer requirements, and inner zeal for studying, enhancing, and fortifying the expert position within higher education ( Smith, 2010 ).

Knowledge and Skills

Knowledge pertains to the collective term for notions, fundamentals, and activities in a particular area of professional expertise and the overall information, and experience that are critical to efficient functioning in learning and using what is taught ( Sierra-Piedrahita, 2007 ). Pedagogical knowledge is important for educators since it portrays the body of knowledge on educational cycles and settings for learners ( O’Riordan, 2018 ). Alternatively, skills allude to the things “people know how to fulfill” and which are “achieved through practicing” ( Sierra-Piedrahita, 2007 ). Skill or ability refers to the people’s capability to do numerous tasks in a profession and it is also defined by Khorasgani (2019) as something one is familiar with how to perform. Having attempted to designate the knowledge base of education, seven classes of educators’ knowledge are recommended which encompass material knowledge, overall educational knowledge, curriculum knowledge, educational material knowledge, knowledge of learners and their features, knowledge of scholastic settings, knowledge of academic goals, goals, and principles, and their theoretical basis ( Ingvarson et al., 2005 ). Such scope of knowledge is highly difficult for educator trainers and learners similar, because ethnicity, social status, cultural variations, and inequality are sensitive, filled with sense and affection, and links to everybody’s central ideas and values ( Goodwin and Kosnik, 2013 ).

Conclusion and Implications

Professional development for educators is now deemed as a crucial element of guidelines to improve the standard of teaching and education in colleges. Therefore, there is prominent attention to studies that determine attributes of successful professional education ( Ingvarson et al., 2005 ). The educational intention of the PD for educators was to attain the skills required to enable learners’ education through explorations that aimed at scientific inquiry skills covered in their teaching process. However, teacher trainers are being considered professionals and their PD is inevitably on the rise. Teacher educators’ PD is an inevitable cycle and a crucial component of enhancing learning overall; therefore, teacher trainers should be dynamic mediators in their growth by keeping themselves up to date with novel information developing and improving knowledge on education and teacher instruction to enhance and boost their own teaching.

In addition, educator trainers need to teach educators with enough knowledge of learners’ learning patterns and tactics. Educators require learning regarding various methods of learning as employed by different individuals, such that they can efficiently goal education in the direction of learners’ learning requirements. Education knowledge and skills are anticipated to be designed by educator trainers during their educator training classes as they are typically liable to make them explicit and reachable to learner educators. Teacher trainers are predicted to build novel knowledge, including knowledge in practice in the framework of recent curricula and learning programs for educator trainers and schools besides knowledge in theory produced from studies.

Based on the literature, an effective teacher educator needs to have enough knowledge of particular and efficient approaches to expose scholar-teachers to numerous diverse techniques of teaching and they are also capable of assisting them to collect a remarkable style of their own teaching. Thus, educator trainers must get acquainted with the knowledge of research and skills, and with the skills to monitor learner educators in doing studies. Professional development practices were made to make them ready for it. Teacher educators feel better equipped for the new tasks if they are provided with the prospects to be present at PD tasks with the accurate situations. There is a need to hold seminars and conferences as they are the main paths to PD for educator trainers and they are sometimes employed for bringing in new knowledge and activity. More studies specifically empirical should be conducted that employ interview as through implementing the interviews, more in-depth understanding can be achieved.

Author Contributions

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

This work was supported by Research on the integration of the historical experience of the CPC’s hundred years of struggle into the teaching of Ideological and Political Course, Teaching reform project of Dalian Maritime University in 2022; Construction of red practice curriculum under the background of “party history integrated into Ideological and political teaching,” Liaoning Social Science Planning Fund project in 2022.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Akbari, R., and Dadvand, B. (2011). Does formal teacher education make a difference? A comparison of pedagogical thought units of B.A. versus M.A. teachers. Modern Lang. J. 95, 44–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2010.01142.x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Berry, A. (2016). “Teacher educators’ professional learning: a necessary case of ‘on your own’?,” in Proceedings of the Biennial International Study Association of Teachers and Teaching Conference 2013 , eds B. De Wever, B. R. Vanderlinde, M. Tuytens, and A. Aelterman (Cambridge, MA: Academia Press), 39–56.

Google Scholar

Blank, R. K., and Alas, N. (2010). Effects of Teacher Professional Development on Gains in Student Achievement: How Meta-Analysis Provides Scientific Evidence useful to Education Leaders. Washington, DC: Council of Chief State School.

Buchberger, F., Campos, B. P., Kallos, D., and Stevenson, J. (2000). Green Paper on Teacher Education in Europe: High Quality Teacher Education for High Quality Education and Training . Umeå: Umea University, Thematic Network for Teacher Education in Europe (TNTEE).

Butler, Y. G. (2015). English language education among young learners in East Asia: a review of current research (2004–2014). Lang. Teach. 48, 303–342. doi: 10.1017/S0261444815000105

Czerniawski, G., MacPhail, A., and Guberman, A. (2017). The professional development needs of higher education-based teacher educators: an international comparative needs analysis. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 40, 127–140. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2016.1246528

Daniel, S., and Peercy, M. M. (2014). Expanding roles: teacher educators’ perspectives on educating English learners. Act. Teach. Educ. 36, 100–116. doi: 10.1080/01626620.2013.864575

Darling-Hammond, L. (2010). Evaluating Teacher Effectiveness: How Teacher Performance Assessments can Measure and Improve Teaching. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress.

Day, C., and Gu, Q. (2007). Variations in the conditions for teachers’ professional learning and development: sustaining commitment and effectiveness over a career. Oxford Rev. Educ. 33, 423–443. doi: 10.1080/03054980701450746

DeMonte, J. (2013). High- Quality Professional Development for Teachers: Supporting Teacher Training to Improve Student Learning. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress.

Futernick, K. (2007). A Possible Dream: Retaining California Teachers so all Students can Learn. Long Beach, CA: California State University.

Gomes, C., Kruguanska, S., Gouvea, I., Madruga, L., and Schuch, V. (2015). Conditioning factors for learning-oriented organizations. Int. J. Innovat. Learn. 17, 453–469. doi: 10.1504/IJIL.2015.069631

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Goodwin, A. L., and Kosnik, C. (2013). Quality teacher educators= quality teachers? Conceptualizing essential domains of knowledge for those who teach teachers. Teach. Dev. 17, 334–346. doi: 10.1111/josh.13076

Guskey, T. R. (2009). Closing the knowledge gap on effective professional development. Educ. Horiz. 87, 224–233.

Harris, A., and Jones, M. (2010). Professional learning communities and system development. Improving Schools 13, 172–181. doi: 10.1177/1365480210376487

He, Y., Prater, K., and Steed, T. (2011). Moving beyond ‘just good teaching’: ESL professional development for all teachers. Prof. Dev. Educ. 37, 7–18. doi: 10.1080/19415250903467199

Ingvarson, L., Meiers, M., and Beavis, A. (2005). Factors affecting the impact of professional development programs on teachers’ knowledge, practice, student outcomes & efficacy. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 13, 1–28. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1423-5

Kang, H. S., Cha, J., and Ha, B. W. (2013). What should we consider in teachers’ professional development impact studies? Based on the conceptual framework of DeSimone. Creat. Educ. 4, 11–18. doi: 10.4236/ce.2013.44A003

Khorasgani, A. T. (2019). The contribution of teaching skills and teachers’ professionalism toward students’ achievement in Isfahan, Iran. Int. J. Latest Res. Human. Soc. Sci. 2, 29–40.

Lin, E. (2013). “Preparing teacher educators in U.S. Doctoral programs,” in Preparing Teachers for the 21st Century, New Frontiers of Educational Research , eds X. Zhu and K. Zeichner (Berlin: Springer-Verlag), 189–200. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-36970-4_11

Livingston, K. (2014). Teacher educators: hidden professionals? Eur. J. Educ. 49, 218–232. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12074

Loughran, J. (2014). Professionally developing as a teacher educator. J. Teach. Educ. 65, 271–283. doi: 10.1177/0022487114533386

Loughran, J., and Hamilton, M. L. (2016). “Developing an understanding of teacher education,” in International Handbook of Teacher Education , eds J. Loughran and M. L. Hamilton (Singapore: Springer), 2–22. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-0366-0_1

Lunenberg, M., Jurriën, J., and Korthagen, F. (2014). The Professional Teacher Educator: Roles, Behavior, and Professional Development of Teacher Educators. Amsterdam: Sense publisher.

Lunenberg, M., Murray, J., Smith, K., and Vanderlinde, R. (2017). Collaborative teacher educator professional development in Europe: different voices, one goal. Prof. Dev. Educ. 43, 556–572. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2016.1206032

Macia, M., and García, I. (2016). Informal online communities and networks as a source of teacher professional development: a review. Teach. Teacher Educ. 55, 291–307. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.01.021

MacPhail, A., Ulvik, M., Guberman, A., Czerniawski, G., Oolbekkink-Marchand, H., and Bain, Y. (2019). The professional development of higher education-based teacher educators: needs and realities. Prof. Dev. Educ. 45, 848–861. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2018.1529610

Margolis, J. (2008). What will keep today’s teachers teaching? Looking for a hook as a new career cycle emerges. Teach. Coll. Rec. 110, 160–194.

Murray, J., and Kosnik, C. (2011). Academic work and identities in teacher education. J. Educ. Teach. 37, 243–246. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2011.587982

O’Riordan, F. (2018). Transformational pedagogy through curriculum development discourse. Int. J. Innovat. Learn. 23, 244–260.

Sierra-Piedrahita, A. M. (2007). Developing knowledge, skills and attitudes through a study group: a study on teachers’ professional development. Ikala 12, 279–305.

Smith, P. K. (2010). “Professional development of teacher educators,” in International Encyclopedia of Education , eds E. Baker, B. McGaw, and P. Peterson (Oxford: Oxford Elsevier), 681–688. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-044894-7.00675-8

Snoek, M., Swennen, A., and van der Klink, M. (2010). “The teacher educator: a Neglected factor in the contemporary debate on teacher education,” in Advancing Quality Cultures for Teachers’ Education in Europe: Tensions and Opportunities , eds B. Hudson, P. Zgaga, and B. Astrand (Sweden: Umea University), 33–48.

Sonmark, K., Revai, N., Gottschalk, F., Deligiannidi, K., and Burns, T. (2017). Understanding teachers’ pedagogical knowledge: report on an international pilot study. OECD Educ. Work. Papers 159, 1–11.

Swennen, A., Jones, K., and Volman, M. (2010). Teacher educators: their identities, sub-identities and implications for professional development. Prof. Dev. Educ. 36, 131–148. doi: 10.1080/19415250903457893

Van der Klink, M., Kools, Q., Avissar, G., White, S., and Sakata, T. (2017). Professional development of teacher educators: What do they do? Findings from an explorative international study. Prof. Dev. Educ. 43, 163–178. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2015.111450

Villegas-Reimers, E. (2003). Teacher Professional Development: An International Review of the Literature. Paris: International Institute for Educational Planning, UNESCO.

Zhiyong, S., Muthukrishnan, P., and Sidhu, G. K. (2020). College English language teaching reform and key factors determining EFL teachers’ professional development. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 9, 1393–1404. doi: 10.12973/eu-jer.9.4.1393

Keywords : knowledge, professional development, teacher trainers, teaching skills, teaching knowledge

Citation: Su H and Wang J (2022) Professional Development of Teacher Trainers: The Role of Teaching Skills and Knowledge. Front. Psychol. 13:943851. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.943851

Received: 14 May 2022; Accepted: 31 May 2022; Published: 28 June 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Su and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hang Su, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Role of Field Training in STEM Education: Theoretical and Practical Limitations of Scalability

Kseniia nepeina, natalia istomina, olga bykova.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence: [email protected] ; Tel.: +996-(312)613140 or +996-755-77-07-50; Fax: +996-312611459

Received 2020 Feb 18; Accepted 2020 Mar 1; Collection date 2020 Mar.

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ).

In this article, we consider the features of the perception of student information in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education, in order to draw the attention of researchers to the topic of learning in practice through field training. The article shows the results of these studies in Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS countries: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, as an example) to reflect the global trends. For this purpose, we examined the expectations of students in Russia and the CIS countries from training related to lectures and field training. We created a questionnaire and distributed it in three Moscow-based universities (Moscow State University of Geodesy and Cartography—MIIGAiK, Moscow Aviation Institute—MAI, and Moscow City University—MCU). Our key assumption is that field practices in Russian universities are qualitatively different from the phenomenon described in European literature, where digital or remote field practices have already emerged. The results obtained through the survey show the tendency of students’ perceptions to fulfill practical duties (in a laboratory with instruments of field training) in STEM education.

Keywords: new educational model, higher education, skills, qualification, STEM education, geopolygon, test site, field training, Earth sciences

1. Introduction

The history of human society is divided into the three areas of its functioning—state and legislative, economic life, and cultural environment—through the development of which we can observe human history. The education system, i.e., the transfer of culture from generation to generation, is an essential element in the development of human society [ 1 ]. Global key trends and obstacles in the progress of higher education are connected by two facts. First of all, the personality of a contemporary student has changed. A separate structure has replaced the transition from homeschooling (parental) education. Second, educational technologies have been altered too. Due to knowledge transfer, nowadays there is an increasing number of technologies in higher education, and teachers can be trained in these new presenting methods. The specifics of studying science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) require mandatory support from theoretical courses with unique practices at training polygons.

Another change in the field of education that can be discovered from observations of the history of the development of human society is the introduction of the state–legal side to the cultural side of society. Initially, education was transmitted through the family. Then, for example, in England, in the 18th and 19th centuries, schools were a matter of social initiative. Nowadays, the ideas of economic life penetrate the education system; education is transferred to the service sector, while the state and legal influence on it does not wane. This position leads to opposite points of view, listed in [ 2 ]. That is why, currently, a person is considered uneducated without a state-approved document, and in the context of globalization, this trend is becoming global [ 3 ]. Unification of programs is appearing, education standards are being revealed, and the degree of uniformity in the transfer of knowledge is growing. Thus, more formal specialized methods for knowledge transfer must be forced to change. This is linked with the solution of using psychological and pedagogical tasks, as well as utilizing soft skills (teamwork training, leadership development, etc.).

Now, we are witnessing the separation of intellect from personality. Industry 4.0 proclaims automatization that exalts the organization’s intelligence in the decision-making system, while the managerial role of the person is excluded. Personal changes are manifested in modern users of education. They differ from their predecessors in pragmatism, a sense of independence, lack of concentration of attention and inability to listen, clip thinking, and the need for self-expression [ 4 ]. Also, one of the most required abilities is to do patient and accurate fulfillment of similar tasks, which vary by visualization type.

The personal contemporary portrait of individual students is changing, as evident in the separation of the human “me” from nature, the appearance of a landscape in painting, the birth of nation states, the appearance of abstract thought in mathematics, and formal laws. However, this is not a complete list of the phenomena that indicate a change of eras, or the onset of the era of the new time. Such external conditions correspond to their own set of teaching aids for knowledge transfer: textbooks, learning aurally, or knowledge transfer using language concepts when using lectures. Note that the digital model of education does not scale to the study of scientific subjects related to the study of the history, evolution, and structure of the Earth.

Changes in the environment, including those due to the globalization process, the use of new tools such as online courses, and most importantly, a shift in personality, require a change in learning tools and methods. For learning, you need to use a different set of teaching aids: clips, teaching through visual images, knowledge transfer using new language concepts, replacing lectures with forms of independent work, followed by giving the student the opportunity for public expression to gain approval from members of the social group, but not the teacher. At the same time, it is precisely at the student age that the possibilities of perception, attention, memory, and thinking reach their maximum [ 5 ].

The most significant changes are currently taking place in the Eurasian space since the process of changes takes place in the context of the formation of new states and is inextricably linked with the creation of national education systems with new values. To date, this is the Consortium, whose partners are 16 leading universities in Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine, as well as Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Moldova, and Armenia. The digitalization of the Russian and The Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan) economy poses more challenges and prospects for the implementation of new educational technologies.

It turns out that many students cannot master a specialty by only using visual images. The specifics of the disciplines related to the study of the Earth’s structure presupposes the mandatory follow-up of theoretical courses by particular training at the test site, which helps to neutralize the negative factors of indoor schooling. Knowledge could be improved during training when students solve a specific task in the field. Furthermore, the interaction between the teacher and students at the test site helps to resolve those problems that may not be solvable in the classroom or with online training (the formation of practical work skills goes along with the solution of psychological and pedagogical issues, the study of teamwork, and the creation of leadership qualities). It is necessary to satisfy students’ expectations from training related to lectures and field training. Afterwards, we can compare them with real trends in the dynamics of changes in educational technologies. Since these trends are global, it is necessary to identify the differences that distinguish them in the study of STEM. The purpose of this article is to show the results of experimental studies in Russia and in CIS countries in order to reflect the global nature of trends and the scalability limitations of modern educational technologies on the disciplines of studying Earth sciences. The work consists of an experimental study of the representations of students of specialties related to Earth Sciences, practical skills in STEM education. However, we still mention, as highlights, the problem of real STEM education training in terms of improving the quality of public management in the digital model of education. This article highlights today’s point of view in the academic environment; significance is placed on the non-European pedagogical model, in which the novelty lies inside the real analysis of student requests, although some European countries (for example, Latvia ( www.lu.lv/en ); Germany, University of Applied Sciences of Neubrandenburg, Albania, Serbia) and Latin America (for example, Mexico) also fit well into this system.

2. Methodology

The general forms of knowledge transfer have not changed. On the one hand, more formal specialized methods for knowledge transfer should be forced to change. On the other hand, a change in the personality structure of a contemporary person also requires an alteration in the methods of knowledge transfer from a teacher to a student. Although, the considerable flow of information and the need for its processing complicates the process of growing up, and young people remain infantile for much longer. Therefore, it is difficult to talk about a deliberate choice of a profession or about an uncompromising attitude to study. Thus, we consider the educational environment in Russia and the CIS countries (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan) to highlight global trends regarding the features of the perception of student information in STEM education.

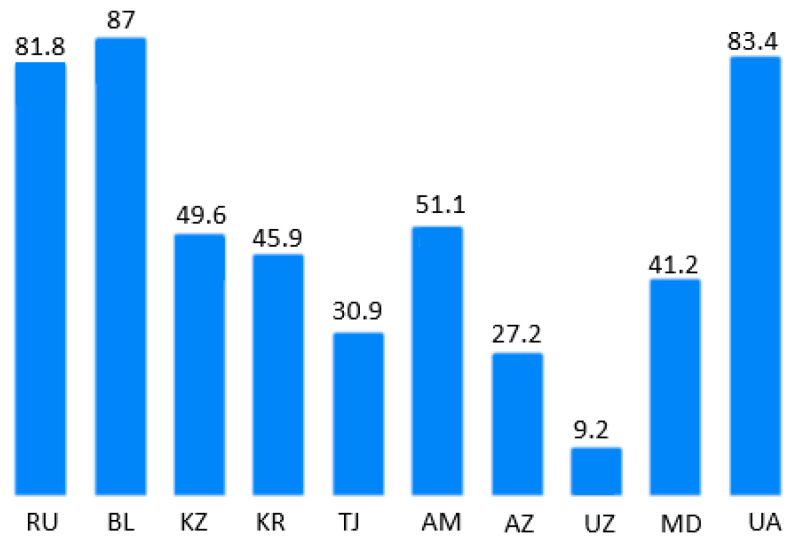

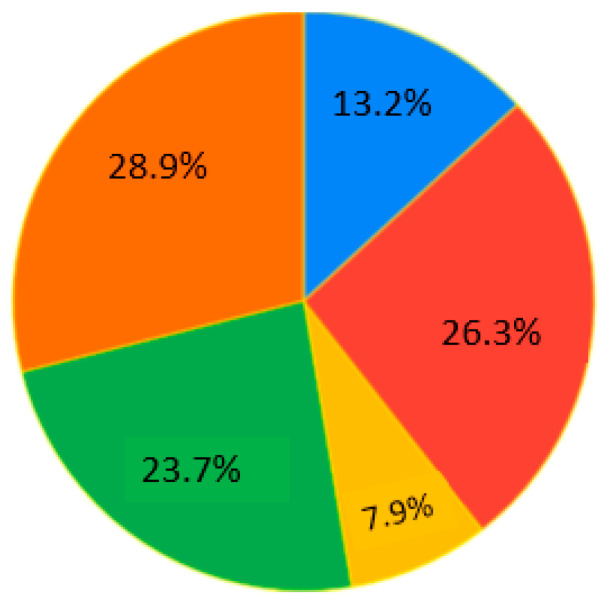

First of all, we are interested in the proportion of the population getting an education in Russia and CIS countries. It is obvious ( Figure 1 ) that three countries, in particular, have the most significant percentages of educative mass—Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia.

Percentage of the population getting the education in CIS countries (RU—Russian Federation, BL—Belarus; Republics: KZ—Kazakhstan, KR—Kyrgyzstan, TJ—Tajikistan, AM—Armenia, AZ—Azerbaijan, UZ—Uzbekistan, MD—Moldova, UA—Ukraine) in 2018 after [ 6 ].

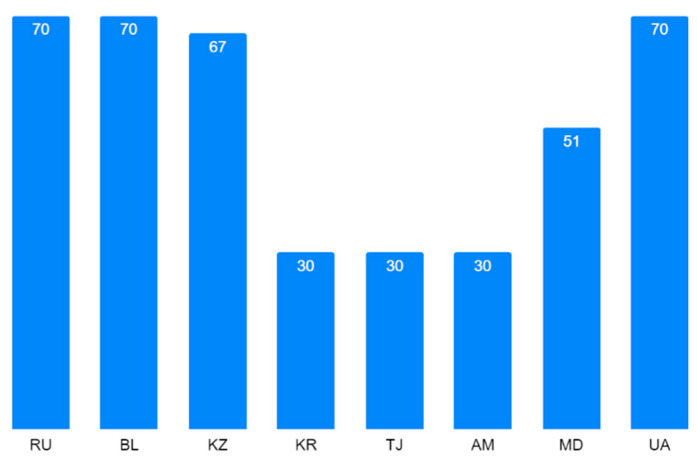

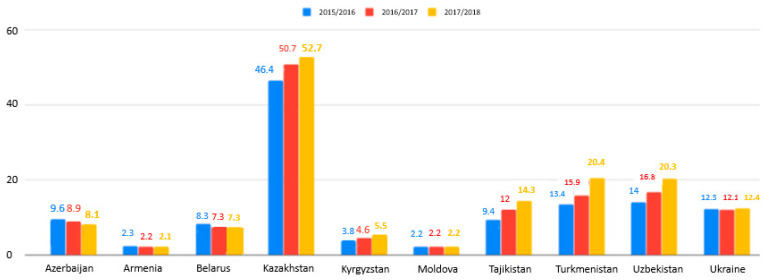

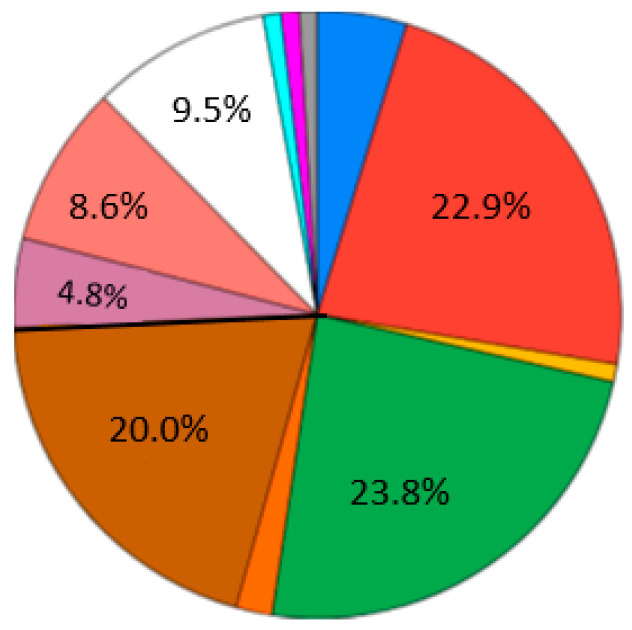

Learning in foreign languages opens up possibilities to study internationally. In [ 6 ], a list was given, showing the CIS ranging by English speaking skills between 80 different countries: Russia was in 38th place, Ukraine in 47th place, Azerbaijan in 64th place, and Kazakhstan in 67th place. Therefore, there is quite a low possibility to teach and to integrate into a globalization context. For Russia and CIS, Russian is the prime language ( Figure 2 ). That is why the number of students from CIS countries studying in Russian state and municipal higher education institutions and scientific organizations with bachelor’s, specialist, and master’s programs in terms of standard admission has been increasing each academic year since 2015 ( Figure 3 ): It was 124 K in 2015/2016, 132.7 K in 2016/2017, and 145.2 K in 2017/2018 in total.

Percentage of the population speaking Russian (RU—Russian Federation, BL—Belarus; Republics: KZ—Kazakhstan, KR—Kyrgyzstan, TJ—Tajikistan, AM—Armenia, AZ—Azerbaijan, UZ—Uzbekistan, MD—Moldova, UA—Ukraine) in 2018 after [ 6 ].

Students from the CIS countries studying in Russian state and municipal higher education institutions and scientific organizations with bachelor’s, specialist, and master’s programs in terms of standard admission at the beginning of the academic year (thousand persons) [ 6 ].

Note that higher STEM education programs at Russian Universities tend to be taught in English. For example, St. Petersburg Mining University ( https://spmi.ru ) and Moscow Gubkin University ( https://www.gubkin.ru ) have been realizing such programs for a few years now. STEM education is in high demand in the mining and geophysics industry. However, it is not a popular program for the students, as the plentiful number of applied tasks frightens young and inexperienced students. In fact, in common with field training, the studying year passes with no summer holidays, and therefore, STEM education in Earth Sciences (which means subjects such as: geography, geodesy, geoecology, geotechnical engineering, geodesy, geomorphology, geology, and geophysics) is rather rare.

2.1. The Place of STEM Education in Russian Universities

According to the Russian Education portal, bachelor students of Geography study at 54 universities and master students study at 31 universities. In recent years, on a federal budgetary basis, about 1.4–1.8 K students were enrolled at the bachelor level in Geography, and 970–3400 students were enrolled at the master level (admission to the magistracy was significantly increased). Fourteen universities are currently preparing bachelor’s programs of hydrometeorology; master’s programs in this direction have been opened at 5 universities. General admission to the bachelor’s program includes more than 500 students, and to the master’s program, about 540 students. General admission to the bachelor’s degree in Applied Meteorology does not exceed 380 students, a set of undergraduates—about 400 students. Bachelor-cartographers study at 13 universities, and masters at 3 universities. The admission quota to the bachelor’s degree in Cartography and Geoinformatics is about 490 students. Herein, higher geographic and environmental education means the preparation of bachelors and masters in the fields of Geography, Hydrometeorology, Cartography and Geoinformatics, and Ecology and nature management. This direction is the only one in which the number of budget places for undergraduate studies has increased in recent years. In the course Ecology and Nature Management, bachelor students graduate in 168 and masters in 75 universities. Admission figures are compiled by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Ecology. In terms of quantitative training indicators for student geographers and ecologists, Russia lags behind many countries. For example, in the UK, geography is studied in more than 80 universities (the number of undergraduate geography students is 30 K); in Germany, in 60 universities; and in France, in 178 universities. In the USA, a bachelor’s degree in geography can be obtained at more than 200 Universities (annual graduation is more than 6 K), a master’s degree in geography in about 90 universities, and a doctor of geography (Ph.D.) in 60 universities. In India, an average of 12.5 K students study annually in undergraduate programs in geographical programs, 4–5 K students are enrolled in graduate and postgraduate studies annually, and these numbers are planned to increase significantly by 2020 [ 7 ].

The real state of education in STEM with Pedagogical Examples is given in [ 8 ]. Navigation skills and STEM learning, specifically related to the field of Geography and Geoscience (Earth Sciences), are essential as they help to pursue professional development. The ability to integrate and connect different routes to create a map of the environment, to relate them to each other, and to investigate them is a specialty of field training. From this point of view, research examining the effectiveness of geoinformation systems (GIS) training is under consideration [ 9 ]. “A geophysics class may also incorporate labor field-based activities using a particular instrument (e.g., radar, gravimeter) to measure variations in material properties, and then discuss potential limitations in the measurements that aid interpretations of the data. With both types of activities, developing that capacity to make logical conclusions that flow from the available data is a key focus of the learning experience” [ 10 ].

2.2. Field Training

The basic principle of practical training is a combination of practical exercises with simulation methods in the development of practical skills and fluency with new equipment. Field training is one of the main activities to ensure the development of hard skills. Field training in STEM education is much more effective because it connects both types of skills: soft and hard. The collective work using professional devices, for example, a surveying instrument with a theodolite (a rotating telescope for measuring horizontal and vertical angles), is usually made by at least two persons together.

Moscow State University of Geodesy and Cartography (MIIGAiK) educates students in the scope of problems of geodesy, cartography, and cadastre, as well as such specific fields as precise instrument-making, geoinformatics, ecology, and remote sensing [ 11 ]. The glorious past of MIIGAiK, deep-rooted in pedagogical and scientific traditions accumulated throughout the 225 years of its development, the importance and vitality of geodetic science and practice for many branches of national economy, with a wide range of specialists being trained at the University—all of these factors assure the leading role of MIIGAiK as a specialized institution of higher education [ 12 ]. More than 2000 foreign students have graduated from the University. The University study provides theoretical and practical training, and STEM education disciplines (such are geographic information technologies (GIS)) are educated at the Department of Cartography of MIIGAiK [ 11 , 12 , 13 ].

The evidence that has emerged from the studies [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ] has proved that the field-based approach is effective in helping students to attain the required knowledge for the understanding of the natural context, and to illustrate phenomena and confirm their skills. As well as soft skills, other competencies such as scientific reasoning and inquiry capacities are also developed. Training offers the opportunity to work as part of a team (as you know, this particular skill in recent years has been a weak spot among students of MIIGAiK, for example, as teachers who travel to practice with students have repeatedly stated). Students also learn safety rules, which are more crucial than in general conditions in classrooms.

Another critical difference between domestic and European geographic education is that, in Russia, many more hours are devoted to training and production practices [ 19 , 20 ], particularly in undergraduate studies, with up to 36 h, which is 9%–15% of the total complexity. In Europe, the most widespread field practices are preserved at universities in the Netherlands (4 weeks), and in the UK, France, and Sweden, which do not exceed two weeks. During training, students travel not only to various regions of their country but also to non-CIS countries (for example, Africa, Central America, etc.). In most European universities, field practices are study tours lasting 1–2 days, the purpose of which is to teach students to work on a specific topic in small groups. Such trips are usually paid for by the students themselves; in an academic year, there are only 2–3 trips [ 7 ].

In Russia, in recent years, the problem of financing field training practices has come to the fore, especially in regional universities [ 7 ]. There is the threat of losing rich experience in conducting field training as the practice, which has always been not only a way to acquire and consolidate knowledge, but also a form of preparation for professional activity. In addition to funding problems [ 19 ], Russian universities are faced with organizational issues in conducting training and production practices, in their methodological and instrumental support, and in being equipped with modern laboratory equipment.

Principally, training in STEM education has a number of disadvantages. “There may be gendered issues, cultural and language barriers, logistical issues, security issues and problem in creating accurate risk assessments without prior visits by staff. There are also issues around privileged, educated, and relatively affluent university students going to view and study underprivileged groups or locations in poorer societies, often without their consent” [ 20 ]. There is a potentially high risk for safety violations because of weather conditions. Virtual reality (VR) classes could be limited by technology and have struggled to expand due to a lack of computing power and memory [ 21 ].

Education is mostly impacted by new spatial visualization software and virtual reality (VR) in higher education, which is a big trend [ 21 ]. Also, in some places, geological virtual field experiences (VFEs) have been developed that consist of form high-resolution two-dimensional (2-D) photomosaics and three-dimensional (3-D) computer models [ 10 ]. VFEs can potentially eliminate some of the issues that physical field trips can create.

According to new educational technologies, some countries use Virtual reality techniques, such as in [ 8 , 10 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ]. This is because the students need visualization in order to provide evidence of some geological processes, for example, plate tectonics. A comparison of the most popular models of head-mounted display systems for virtual reality (VR) used for educational purposes is given in [ 10 ]. However, we agree with [ 10 ] that sometimes, some test scenarios would be too difficult or dangerous to perform in real life.

Based on the analysis of some institutional changes in the higher education system, we aim to justify the conclusion that the problem of obtaining knowledge in real space in the digital age is growing. Comparing the collected data with descriptions of the problem in foreign literature, we show that the domestic higher education system is characterized by a particular type of student dropout, associated with physical limitations in the admission of students, which requires individual study and targeted measures of educational policy in connection with the characteristics of the profession. At the moment, even if there is no possibility of an internship within the university, students are forced to undergo field practices outside the university. That is why it is so essential to create and maintain the stability of field test training sites or geopolygons. The requirements for geopolygons are restricted. First of all, remoteness from the noise is needed. Second, pure nature is essential in order to conduct experiments (such as drone test). Field scientific and educational centers will provide cooperation of the educational, scientific, and production organizations in the sphere of Earth sciences. They will be based on the principle of unity of technologies of scientific expedition support [ 19 ]. As such, the Research Station of the Russian Academy of Sciences at the Bishkek Geodynamic polygon is suitable for these conditions [ 33 , 34 , 35 ]. The network of field test sites will include regional field scientific and educational centers. At MIIGAiK University, there is a Site called Chekhov Geopolygon [ 36 ]. Moscow State University established a geophysical training site 200 km from Moscow on the Russian platform in 1992 [ 37 , 38 , 39 ]. The development of field test sites and saving the key long-term field reference areas are both possible as part of a national network. The unified standard infrastructure of field test sites will allow the efficient scaling and distribution of modern methods of researches in expeditions. The optimization of a network of field test sites is possible on the basis of their inventory, determination of their uniqueness, status, and perspectives of development [ 19 ].

2.3. STEM Online Education at the National Universities

Massive open online courses (MOOC) is a new tool in education [ 40 , 41 ]. However, serious pedagogical concerns associated with the inability of an instructor to provide individualized instruction to thousands of students have emerged [ 42 , 43 ]. Also, according to [ 42 ], the analysis of the completion of the course from the “Satellite Technologies in Geography” section concludes that: “It is not true that a MOOC must necessarily be absent of any faculty presence, just as it is also not true that a successful MOOC must only feature lecture videos or be taught by a faculty member who is famous”.

It should be noted that the grant support is aimed today at the digitalization of education “Modern Digital Educational Environment in the Russian Federation” [ 44 ]. The results are visible via digital platforms [ 45 , 46 ].

The online resource aggregator http://neorusedu.ru/ [ 45 ] provides access to courses from Russian Universities, expanding exclusively for Russian citizens the opportunity to study throughout their life at any convenient time, wherever they are at that moment—the main requirement for these types of courses is that an Internet connection is available. Additionally, this resource pays excellent attention to attracting the cooperation of employers. If the electronic certificate received after the final exam serves as a confirmation that students completed the test (more than a hundred universities are connected to the “one window” resource, whose students master some of the disciplines online), then for the rest of the students, it is a certificate of new knowledge and competencies. One of the educational models provides for the complete replacement of the discipline in the curriculum with online courses. The second educational model is that of blended learning, where online courses replace only the theoretical part of the subject. The practical part—laboratory, workshops, seminars—is accompanied by a university teacher. Today, educational organizations are more likely to lean toward the second model.

Another national platform of open education, “Open Education” https://openedu.ru/ [ 46 ], is a modern educational platform that offers online courses in basic disciplines studied at Russian universities. The Association “National Platform created the platform for Open Education” was established by the leading universities Moscow State University M.V. Lomonosov, St. Petersburg Polytechnic University, St. Petersburg State University, National University of Economics “MISiS”, Higher School of Economics “HSE, MIPT”, Ural Federal University “UrFU”, and Saint Petersburg National Research University of Information Technologies, Mechanics and Optics “ITMO”. All courses posted on the Platform are available free of charge and without formal requirements of a basic level of education. Compared to courses of other online learning platforms, courses of the national platform have certain features:

all courses are developed following the requirements of federal state educational standards;

all courses meet the requirements for the results of training of educational programs implemented in universities;

special attention is paid to the effectiveness and quality of online courses, as well as to the procedures for evaluating learning outcomes.

The international Coursera portal ( https://www.coursera.org/ ) contains programs from prestigious universities and employers from around the world, from Russian Moscow State University and St. Petersburg State University to Stanford University and Google [ 47 ]. More than 50 courses are now offered in Russian or with Russian subtitles. However, on international platforms, all courses are covered in English, while on national platforms, they are in their native language. However, we are faced with a problem: most online courses are aimed at first-year or second-year students.

As a procedure for understanding trends in STEM education in Russia and CIS countries, we examined the students’ expectations. As an instrument, we have used the online survey (see Table 1 ), which we have created in later 2019. The participants present three Moscow-based universities (Moscow State University of Geodesy and Cartography—MIIGAiK, Moscow Aviation Institute—MAI, and Moscow City University—MCU) and some academic staff. In the results section we provide data analysis.

Survey questions and answers (powered by Istomina N.L. and Nepeina K.S.).

The educational environment in Russia and CIS countries reflects the global world trends in learning processes. With the introduction of digital learning technologies, knowledge transfer has changed. Massive open online courses and open learning platforms are designed to show that distance learning can be scaled to all educational specialties. However, teaching technologies in the form of passive contemplation by students of the visual range and solutions of test problems cannot be scalable to study the disciplines necessary to obtain professional competencies and knowledge in STEM education (Earth sciences). STEM education specifically requires the mandatory support of theoretical courses with individual practices at the test sites. Inversely, we observe a decrease in the educational time units designed for training practices in STEM and Earth sciences (geography, geodesy, geoecology, geotechnical engineering, geodesy, geomorphology, geology, and geophysics) —there is a tendency to replace off-site activities with online and VR technologies.

In order to show the limited scalability of modern educational technologies to disciplines related to the study of Earth sciences, we give arguments confirming the importance of the formation of practical work skills, which goes hand in hand with the solution of psychological and pedagogical tasks, teamwork training, leadership formation, and patient and thorough implementation of the same tasks. Based on the results of an empirical study conducted in three Moscow universities, and including a survey of some students and some respondents who recently graduated from the university, we consider the peculiarities of students’ perceptions of information in STEM (Earth sciences) and their expectations from the learning process. We proceed from the fact that field practices in Russian universities are qualitatively different from the phenomenon described in the European literature, where digital or distance field practices for people with disabilities are already appearing. Thus, we developed a special online survey, with the idea to highlight the point of view of a modern student on educational technology.

The level of preparedness of students to work with electronic resources is very heterogeneous. Thus, the development of resources and Internet technologies comes to the fore. At the same time, there has been a rapid growth in information and communication technologies (video conferencing, webinars, groups on social networks, and many others), which makes it possible to organize not only the passive perception of online courses, but also the active remote interaction of students, a collective discussion of the material, and joint execution of tasks, all while at significant physical distances from each other. Therefore, the university teacher is now faced with the need to possess not only subject knowledge and modern technical means, but also management techniques of computer-mediated educational communication. Mastering the educational form of information education is an urgent task of our time.

The students’ lack of understanding of the concepts of a map section, a cross-section of a complex technical object (spatial ability into constituent spatial skills), and aberrations of an optical image of a star in a telescope observed by students moves us toward a change in the methods and technologies of teaching technical disciplines for students of geodesic, cartographic, and geophysical specialties from visual static illustrations to dynamic pictures as of films. To handle the material, it is necessary that when reading a lecture, an interactive way of conducting classes is used [ 6 ]. Such tools can provide access to the Internet and gadgets. American physicist Michio Kaku believes that the basis of future education is Google Glass, and those who study through lectures are losing out [ 20 ].

However, if in the case of training, the student is gaining courses following the curriculum, then such an instrument does not exist for the employee of the company (teacher, researcher, engineering, and technical personnel). In this case, the employee sometimes must forcibly acquire knowledge at any other possible sites.

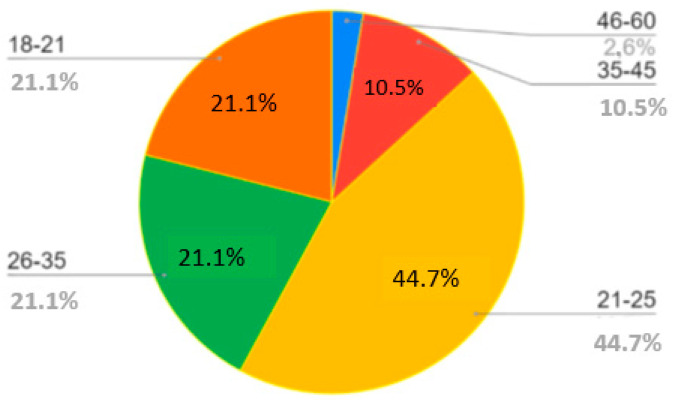

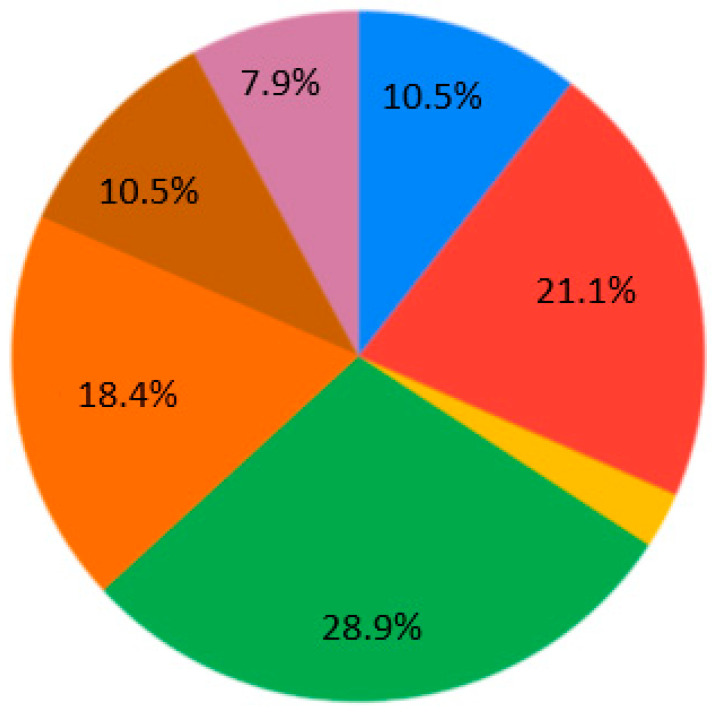

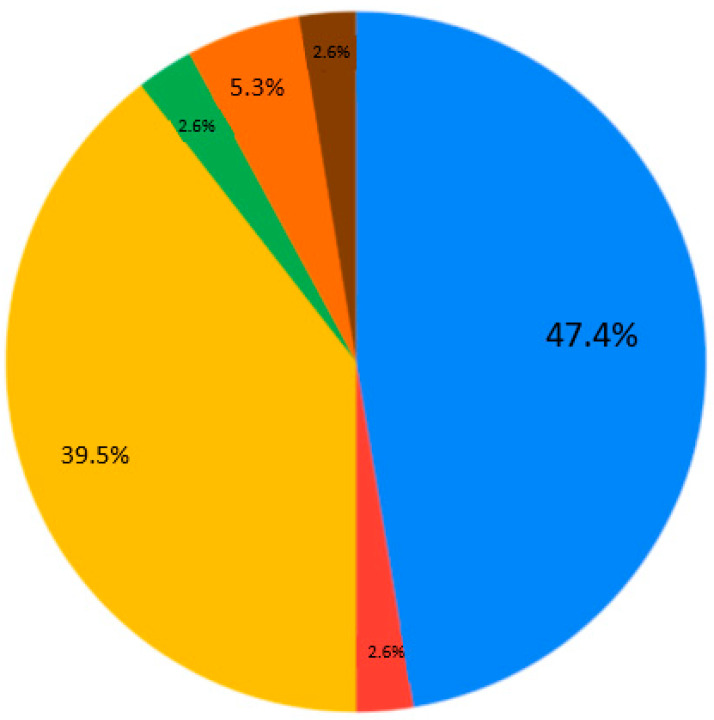

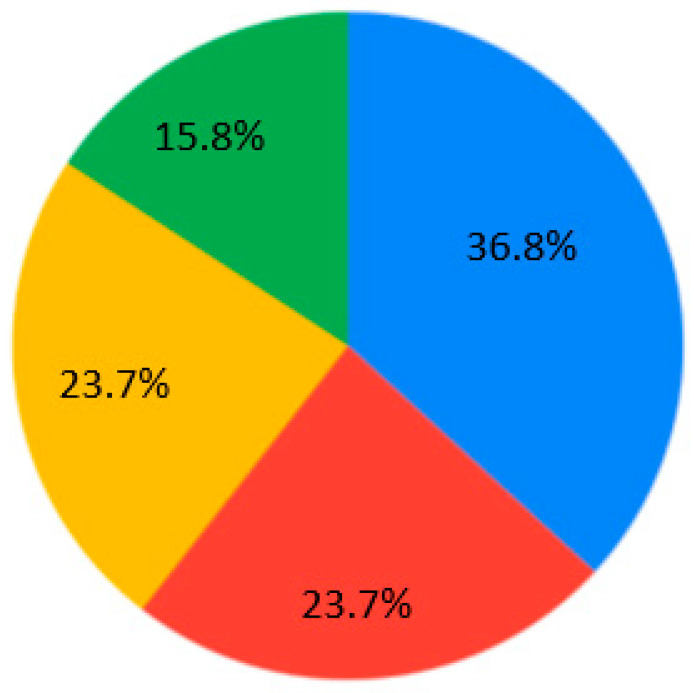

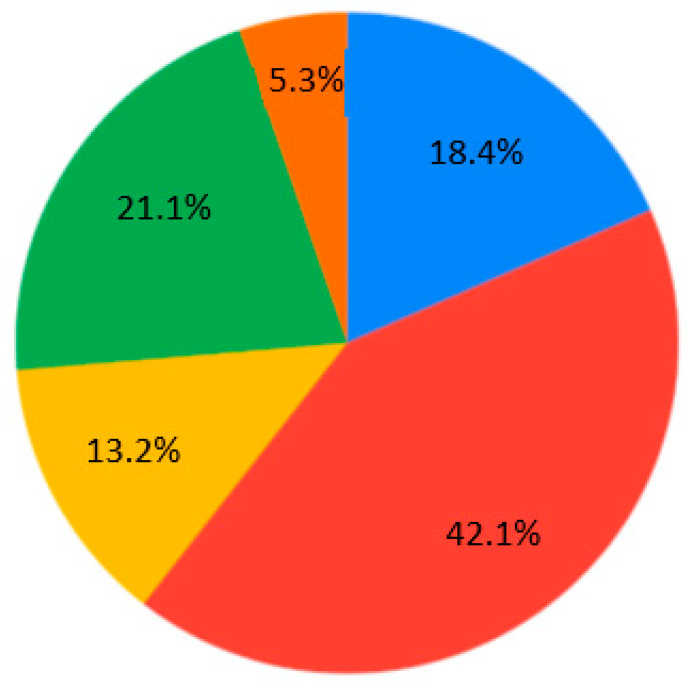

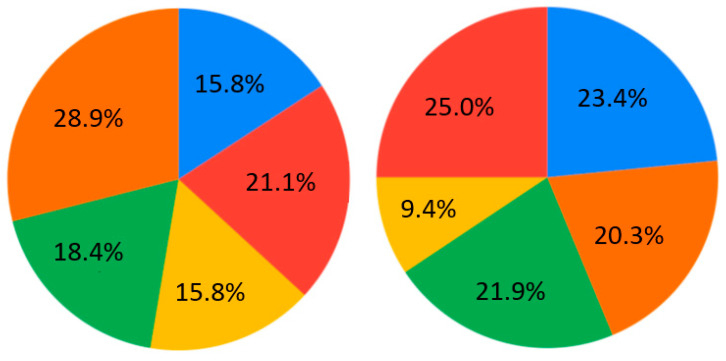

In 2019, a voluntary Survey (details in the Table 1 ) about state-of-the-art education in the Geoscience Faculty of MIIGAiK, the faculty of Innovations and a pedagogical group of students answered questions. Short questionnaires were administered to 64 respondents, including students from the bachelor’s and master’s programs, with ages ranging from 18 to 25 (average age, 23 years). The observation reports were powered by the researchers (the authors). The advantage of resorting to diverse techniques and instruments to collect data was the possibility to triangulate quantitative and qualitative methods, thus enhancing the validity of the results. The validation of the short survey was carried out by the authors. The questionnaires that were administered to evaluate the preparatory and summary units had the following closed questions ( Table 1 ), which had to be answered at least in 5 variants. Reports were written after the class to verify the relevant (positive and negative) aspects of the mediation process, the difficulties of the students’ engagement in the process, and an overall evaluation of the model that was implemented. Circle charts were used to group the items (see Figure 4 , Figure 5 , Figure 6 , Figure 7 , Figure 8 , Figure 9 , Figure 10 , Figure 11 and Figure 12 ) and the description of results (below).

Survey results. Question 1. Age.

Survey results. Question 2. Occupation. Sectors: blue—employee, red—researcher, yellow—unemployed, green—master’s student, orange—bachelor’s student.

Survey results. Question 3. Study objectives. Sectors: blue—there are so many changes in the world that my skills quickly become obsolete (4.8%); red—obtaining skills for mastering a specialty; yellow—none, don’t know (1%); green—obtaining knowledge; orange—while there is no universal and suitable program for me, I have to study in different places; brown—I want to learn everything new; purple—I want to gain an additional specialty; pink—Social status and prestige; white—have a good time within the student auditorium; other (~3%), please specify: light blue—learning ability; magenta—opportunity to “find” interesting topics for professional development; grey—I need education. Development is interesting, I hope to get into an adequate structure, where you really learn and develop, and do not waste time talking and talking for the sake of reporting.

Survey results. Question 4. Lectures perception. Sectors: blue—independently (in the library, in the book); red—as presentations, communication with a lively person; yellow—I do not like to learn new material; green—solving case studies (a method of specific situations) or a game; orange—tête-à-tête with teacher/lecturer/mentor; brown—as a joint discussion as a type of crowdsourcing; purple—as lectures, the audience is communicating with a lively person. Nobody selected the answer “As lectures, communication via Skype, but with one person”.

Survey results. Question 5. Lectures repetition. Sectors: blue—need to take and learn new topics and not to repeat; red—needs to be repeated if necessary; yellow—does not need to be repeated; green—needs to be repeated 1–2 times in the school year; orange—needs to be repeated 1–2 times per semester; answers added by the students (other): brown—regular and straightforward control of knowledge and study of the material helps a lot; purple—the most effective way to consolidate knowledge is to drive through various mechanisms of perception and reproduction by a person: listen, write something, try to convey it to someone; pink—needs to be repeated 1–2 times per semester through case studies, seminars, and lab classwork.

Survey results. Question 6. Proving skills. Sectors: blue—as practical work with geodevices; red—I do not need practical exercises to consolidate skills, as I remember everything; yellow—to create a specific project; green—cogitation tasks that can then be discussed with the teacher and other students, and not just tests; orange—as competition among students, during which my strengths and weaknesses are determined; brown—answers to tests via a computer, where my answers are checked by a robot.

Survey results. Question 7. Visual displays. Sectors: blue—paper versions; red—computer screen; yellow—Virtual Reality headset; green—Movie Screen. The answer “I don’t need to watch. I remember aurally” was not chosen.

Survey results. Question 8. Lecture time. Sectors: blue—I can withstand more than 2 h if I am allowed to move, rather than just sitting in one place; red—45 min; yellow—lying down, I can listen as long as I like; green—1.5 h; orange—15–18 min.

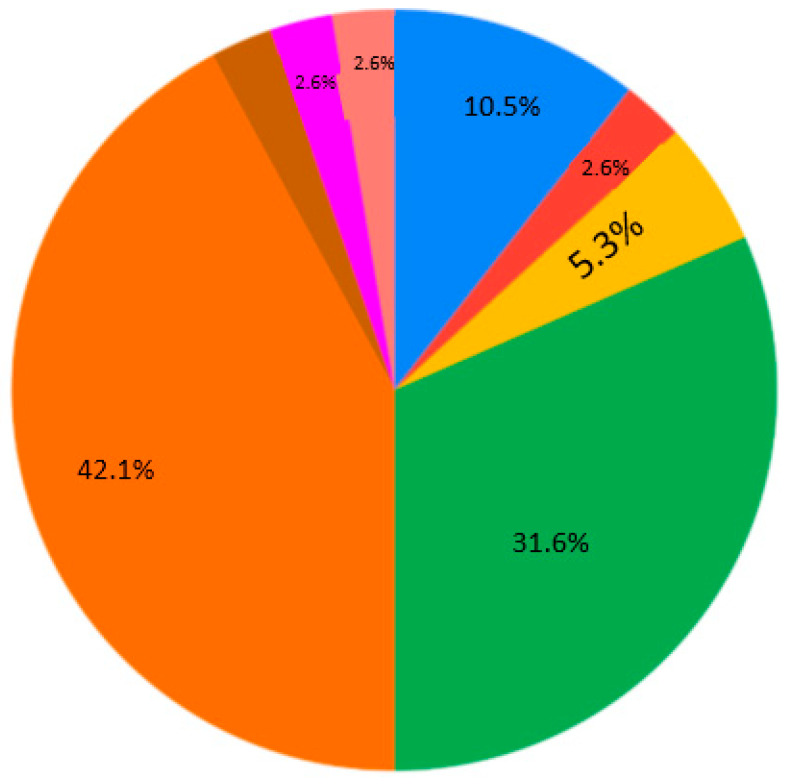

Survey results. Questions 9 and 10. Future work perspectives. Left—the first option, right—the second option. Sectors: blue—I like to travel and do field research; red—remotely as a freelancer; yellow—I do not want to work, I want to continue to study; green—in the office among other employees; orange—managing innovations.

This is a description of the survey. It contains details and data supplemental to the main text. The main flow of questions is with answers ( Table 1 ) using Google Forms online. We were oriented toward inclusive learning environments in undergraduate courses [ 48 ]. We are sure that such a kind of questionnaire provides new information on the current state of teaching practices in STEM education concerning inclusive practices. We expect to compare results in future projects. These results could lead to maintaining focused STEM education development.

The self-reported use of practices across these four categories of ages ( Figure 4 ) and five categories of occupation ( Figure 5 ) are also highlighted. The most significant numbers of testimonials were provided by bachelor’s and master’s students aged 21–25.

The largest proportion of respondents chose their study objectives as getting knowledge (23.8%), followed by obtaining skills for mastering a specialty (22.9%) ( Figure 6 ). Note, that there is still a large number who want to study for learning everything new (20% in Figure 6 ). This means that education is still not only implied for getting a job.

The contemporary generation of students is interested in case studies at the universities (28.9%) ( Figure 7 ). Generally, nobody selected the answer “As lectures, communication via Skype, but with one person” for Q4 ( Figure 7 ). Near equally, the presentation and real communication or tet-a-tet conversation with the teacher are preferable ( Figure 7 ). Concerning material repetition, it is an individual aspect. Most of the students are ready to repeat some material 1–2 times per semester/school year ( Figure 8 ). Regarding the survey results ( Table 1 ), the students are encouraged to test their skills as practical work with geodevices (47.4%) or by creating a case study project (39.5%) ( Figure 9 ). It is also important that, for Q7, the answer “I don’t need to watch. I remember aurally” was not chosen ( Figure 10 ). Despite the implementation of digital technologies, the students gain new information mostly via paper versions (36.8%), and equally less on a computer screen or a virtual reality headset ( Figure 10 ). Most of them are ready for 45-min lectures (42.1%) or 1.5-h lectures (21.1%) ( Figure 11 ). The greater proportion of respondents in the future desire, firstly, to manage innovation (28.9%) or to work remotely as a freelancer (21.1%) ( Figure 12 ). Therefore, it is necessary to think about why modern methods of education are aimed to educate specific skills to rear the ideal workers, while not all graduates are ready to work for specific enterprises.

We obtained survey results that, accordingly, show students’ desires to fulfill practical activities (in a laboratory with field training tools) during STEM classes. We believe that these training practices will be taken into account in the future.

4. Discussion

This article notes that the education system is a part of the national culture that is formed under the influence of history, geography of the country, social and social conditions of life, and which depends on the national mentality and the psychological activity characteristics of both students and teachers alike. The authors conclude that there are some difficulties in the higher education conditions of the 21st century. The new digital era raises the problem of the discrepancy between the skills that a student receives online and the skills he must master during on-site field training.

We agree with Kuznetsov [ 41 ] that Russian students themselves are not ready to accept digital education as a fully-fledged learning method. “The correction of this situation requires the introduction of technological and organizational solutions in the field of education, aimed at adapting the educational system to the dynamically changing needs of the labor market, individualization of educational trajectories and increasing the involvement of students in the educational process”. There is a deficient percentage of students who complete online courses successfully. The teaching of speech disciplines in technical universities is unusual and does not involve everyday usage. Particular attention is paid to the interactive form of conducting classes.

It has been shown [ 41 ] that the education system, formed in the previous technological way, does not meet the needs of contemporary society. The main issue is that there still does not exist a system of recognition of the equality of online education in comparison to traditional forms of education. The fact that there is a continuing lack of implementation of online technologies in the educational process by educational organizations themselves impacts on the process speed. So, if today, in the enterprises and organizations of Russia, 50 personal computers are accounted for 100 employees, of which 33 are connected to the Internet, then in our universities, there are only 228 of these equipped workplaces. Against this fact, the general level of financing of educational organizations in Russia, which is 4.7% of the gross domestic product, seems insufficient. According to the accumulated statistics of the largest educational online platforms, the number of students who reach the end of the training is 5%–13% of the initial admission [ 41 , 49 ]. There are circumstances that highlight the lack of development of the digital infrastructure and the need to train teachers. STEM teachers should mix their identities as a teacher, learner, risk-taker, inquirer, collaborator, and inspector at the same time, especially during field training. Educational institutes need to take into account the difference in the pedagogical culture of international students and Russian teachers. Therefore, educational organizations should find more time and sponsor lecturer training too.

Educational methodological approaches are directly related to existing technologies and the needs of students. However, on the other hand, they are under pressure from official directions of governmental control. Teachers always have to adapt to the available technology and the needs of the students in accordance with state strategy. In fact, we are talking about a change in the general model of higher education. Instead of a humanistic model, which interprets higher education as a human right to enrich oneself with the highest intellectual achievements of humankind and put them at the service of social progress, the economic model is legitimized, which treats higher education as a sphere of investment that brings additional income, financial dividends, and other bonuses—which is no longer consistent with the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. Hence the direct path to the commercialization of relations between teachers and students, to the growth and the dominance of university management, to emasculating from university life everything that does not contribute to economic efficiency, i.e., profitability. The strategy of the digital economy in STEM education leads to a strong university bias toward scientific business services, the transfer of the center of gravity to paid custom research, which leads professors to devote most of their time to it because their status and well-being depend on their scientific activity. The situation emasculates from university life, everything that has little to do with applied tasks, especially with the preservation and development of social and art sciences.

5. Conclusions

The digital world is as essential and immersive as the real one. In a controlled environment, a pre-field trip can increase engagement in the topic studied. There are also benefits to the educator, such as reduced cost, more efficient students on fieldwork tasks, and the ability to tailor and update their field guides to suit their needs. However, there are drawbacks to the challenge of creation and their outcome as standalone educational tools. Online education will definitely develop, and at the same time, the skills of human communication will remain the most critical, which, as practice shows, is the most difficult to learn online. That is why we suggest that educational policymakers insights’ pay attention to and finance the outdoor learning environment as a potential obligatory activity for STEM education. A method of teaching using electronic learning management systems such as e-university and MOODLE can exist only as an addition to the usual forms of educational interaction with lectures and seminars. We agree with authors [ 20 , 21 , 41 ] that the tendency leading to a lack of teacher-student interaction through virtual reality technology is extremely scary. The potential balance between teaching hard and soft skills is a significant issue in the contemporary workplace. There must be an equilibrium between state-of-the-art solutions and human interaction, mentoring, and teacher–student relationships.

It is important to incorporate the outdoor learning environment as an integral part of the learning of STEM education. The best place to train geophysical or geonavigation competences is in well-prepared geopolygons with suitable infrastructure (such as internet access, remote low-noise area, well conditions, etc.). The teacher, having left the school department for the field training, is forced to change the official style of pedagogical communication into a familiar one, creating comfortable working conditions and increasing the effectiveness of learning outcomes.

Results section contains a description of the research methodology (survey, target group set, etc.). The study reveals that opportunities to be involved in practices are useful for students.

This article discussed the processes of global changes in STEM education of higher education, with flashbacks to Russia, linked to the acceptance of the Bologna declaration and digitalization, which is the outcome of global trends in higher education. This resulted, in particular, in the reduction of field training in STEM education. It also poses new requirements of lecturers in the system of higher education, and is involved in the process of new identity formation of being STEM teachers with the many roles and responsibilities associated with such an identity. Backlighted by active integration processes with international systems of education, it becomes evident that many Russian lecturers do not comply with the new requirements of the educational process: lack of or limited knowledge of foreign languages (English), lagging in “informatization” of education, mismatch in humanization and art science of the educational process. Thus, this article underlines the necessity for an anticipatory strategy in education, which is a crucial factor in the progressive development of the country.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their colleagues for their help and for the survey distribution, as well as students and staff of the MIIGAiK, MAI, MCU for participation and MIIGAiK University for the basis. The authors are also thankful for online open-source Google Form utilities ( https://support.google.com/a/users/answer/9302965?hl=en ). We are grateful to the reviewers for their comments, which were helpful in manuscript improving. We also express our gratitude to the academic editor and EJIHPE as a part of MDPI for enabling our research to be published.

Author Contributions

All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Conceptualization, N.I. and K.N.; analysis, data curation, and visualization, K.N.; methods and technologies, and writing of original draft, N.I.; original draft writing and translating, K.N.; methodological approaches and technologies, O.B.; resources, O.B. and N.I.

This research was partly supported by the Russian State Governmental Task of RS RAS № AAAA-A19-119020190063-2.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Due to the funders, the collection data was built. The funders had no role in the interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

- 1. Istomina N.L., Trubetskova E.G. From Haeckel to global ecology (through the view of two cultures). V Congress «Globalistics-2017». Moscow, Moscow State University. Russia, 2017, 2. [(accessed on 29 November 2019)]; Available online: https://lomonosov-msu.ru/archive/Globalistics_2017/data/10131/uid160785_report.pdf . (In Russian)

- 2. Montserrat D.-M., Parede M.R., Saren M. Improving Society by Improving Education through Service-Dominant Logic: Reframing the Role of Students in Higher Education. Sustainability. 2019;11:5292. doi: 10.3390/su11195292. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Loshkareva E., Luksha P., Ninenko I., Smagin I., Sudakov D. Skills of the Future: How to Thrive in the Complex New World. Global Education Futures. World Skills Russia. Report 2014–2017. 2017, 93. [(accessed on 29 November 2019)]; Available online: https://worldskills.ru/assets/docs/media/WSdoklad_12_okt_eng.pdf .

- 4. Loshchikhina A. High Reading Science. Volume 12. Russian World.ru; Moscow, Russia: 2015. pp. 6–9. (In Russian) [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Bykova O., Martynova M., Siromaha V. The Problem of Continuity in the Development of Creative Critical Thinking in the System of Modern School and University Education in Russia. Sci. Res. Dev. Mod. Commun. Stud. 2018;7:37–41. doi: 10.12737/article_5bf5154c93c384.40839949. (In Russian) [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Russia in Numbers 2018. Brief Statistical Bulletin. Moscow, Rosstat 2018, 522. [(accessed on 29 November 2019)]; Available online: https://www.gks.ru/free_doc/doc_2018/year/year18.pdf .

- 7. Universities in the Eurasian Educational Space/Editorial Team: Sadovnichiy, V. et al. Publishing house of the Moscow State University; Moscow, Russia: MAKS Press, 2017, 392 (Series «Eurasian universities of the XXI century») [(accessed on 29 November 2019)]; Available online: http://www.eau-msu.ru/files/eau_mono.pdf . (In Russian)

- 8. Tong V.C.H. Geoscience Research and Education Innovations in Science Education and Technology. Volume 20. Springer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2014. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Nazareth A., Newcombe N.S., Shipley T.F., Velazquez M., Weisberg S.M. Beyond Small-Scale Spatial Skills: Navigation Skills and Geoscience Education. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2019;4:17. doi: 10.1186/s41235-019-0167-2. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Dolphin G., Dutchak A., Karchewski B., Cooper J. Virtual Field Experiences in Introductory Geology: Addressing a Capacity Problem, but Finding a Pedagogical One. J. Geosci. Educ. 2019;67:114–130. doi: 10.1080/10899995.2018.1547034. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Krylov S.A., Zagrebin G.I., Dvornikov A.V., Kotova O.I. Geoinformation technologies in the educational process of the department of cartography of MIIGAiK. Actual Quest. Educ. 2019;1:217–222. (In Russian) [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Site of the University MIIGAiK. [(accessed on 24 November 2019)]; Available online: http://www.miigaik.ru/eng/history.htm .

- 13. Bykova O.P., Martynova M.A., Siromaha V.G. Dynamics Of Language And Cultural Processes In Modern Russia. Volume 6. Non-Profit Partnership Publishing House Society of Teachers of Russian Language and Literature; St. Petersburg, Russia: 2018. University Audience as A Glade of Meanings: To the Problem Statement; pp. 1199–1204. (In Russian) [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Esteves H., Fernandes I., Vasconcelos C. A Field-Based Approach to Teach Geoscience: A Study with Secondary Students. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015;191:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.323. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Boyle A., Maguire S., Martin A., Milsom C., Nash R., Rawlinson S., Turner A., Wurthmann S., Conchie S. Fieldwork Is Good: The Student Perception and the Affective Domain. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2007;31:299–317. doi: 10.1080/03098260601063628. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Gilley B., Atchison C., Feig A., Stokes A. Impact of inclusive field trips. Nat. Geosci. 2015;8:579–580. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2500. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Elkins J.T., Elkins N.M.L. Teaching Geology in the Field: Significant Geoscience Concept Gains in Entirely Field-Based Introductory Geology Courses. J. Geosci. Educ. 2007;55:126–132. doi: 10.5408/1089-9995-55.2.126. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Teasdale R., Ryker K., Bitting K. Training Graduate Teaching Assistants in the STEM education: Our Practices vs. Perceived Needs. J. Geosci. Educ. 2019;67:64–82. doi: 10.1080/10899995.2018.1542476. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Gruzinov V.S. Educational field test sites: Problems and ways of development. Izvestia vuzov «Geodesy and Aerophotosurveying». 2019;63:45–51. doi: 10.30533/0536-101X-2019-63-1-45-51. (In Russian) [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]