Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Eight Instructional Strategies for Promoting Critical Thinking

- Share article

(This is the first post in a three-part series.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom?

This three-part series will explore what critical thinking is, if it can be specifically taught and, if so, how can teachers do so in their classrooms.

Today’s guests are Dara Laws Savage, Patrick Brown, Meg Riordan, Ph.D., and Dr. PJ Caposey. Dara, Patrick, and Meg were also guests on my 10-minute BAM! Radio Show . You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

You might also be interested in The Best Resources On Teaching & Learning Critical Thinking In The Classroom .

Current Events

Dara Laws Savage is an English teacher at the Early College High School at Delaware State University, where she serves as a teacher and instructional coach and lead mentor. Dara has been teaching for 25 years (career preparation, English, photography, yearbook, newspaper, and graphic design) and has presented nationally on project-based learning and technology integration:

There is so much going on right now and there is an overload of information for us to process. Did you ever stop to think how our students are processing current events? They see news feeds, hear news reports, and scan photos and posts, but are they truly thinking about what they are hearing and seeing?

I tell my students that my job is not to give them answers but to teach them how to think about what they read and hear. So what is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom? There are just as many definitions of critical thinking as there are people trying to define it. However, the Critical Think Consortium focuses on the tools to create a thinking-based classroom rather than a definition: “Shape the climate to support thinking, create opportunities for thinking, build capacity to think, provide guidance to inform thinking.” Using these four criteria and pairing them with current events, teachers easily create learning spaces that thrive on thinking and keep students engaged.

One successful technique I use is the FIRE Write. Students are given a quote, a paragraph, an excerpt, or a photo from the headlines. Students are asked to F ocus and respond to the selection for three minutes. Next, students are asked to I dentify a phrase or section of the photo and write for two minutes. Third, students are asked to R eframe their response around a specific word, phrase, or section within their previous selection. Finally, students E xchange their thoughts with a classmate. Within the exchange, students also talk about how the selection connects to what we are covering in class.

There was a controversial Pepsi ad in 2017 involving Kylie Jenner and a protest with a police presence. The imagery in the photo was strikingly similar to a photo that went viral with a young lady standing opposite a police line. Using that image from a current event engaged my students and gave them the opportunity to critically think about events of the time.

Here are the two photos and a student response:

F - Focus on both photos and respond for three minutes

In the first picture, you see a strong and courageous black female, bravely standing in front of two officers in protest. She is risking her life to do so. Iesha Evans is simply proving to the world she does NOT mean less because she is black … and yet officers are there to stop her. She did not step down. In the picture below, you see Kendall Jenner handing a police officer a Pepsi. Maybe this wouldn’t be a big deal, except this was Pepsi’s weak, pathetic, and outrageous excuse of a commercial that belittles the whole movement of people fighting for their lives.

I - Identify a word or phrase, underline it, then write about it for two minutes

A white, privileged female in place of a fighting black woman was asking for trouble. A struggle we are continuously fighting every day, and they make a mockery of it. “I know what will work! Here Mr. Police Officer! Drink some Pepsi!” As if. Pepsi made a fool of themselves, and now their already dwindling fan base continues to ever shrink smaller.

R - Reframe your thoughts by choosing a different word, then write about that for one minute

You don’t know privilege until it’s gone. You don’t know privilege while it’s there—but you can and will be made accountable and aware. Don’t use it for evil. You are not stupid. Use it to do something. Kendall could’ve NOT done the commercial. Kendall could’ve released another commercial standing behind a black woman. Anything!

Exchange - Remember to discuss how this connects to our school song project and our previous discussions?

This connects two ways - 1) We want to convey a strong message. Be powerful. Show who we are. And Pepsi definitely tried. … Which leads to the second connection. 2) Not mess up and offend anyone, as had the one alma mater had been linked to black minstrels. We want to be amazing, but we have to be smart and careful and make sure we include everyone who goes to our school and everyone who may go to our school.

As a final step, students read and annotate the full article and compare it to their initial response.

Using current events and critical-thinking strategies like FIRE writing helps create a learning space where thinking is the goal rather than a score on a multiple-choice assessment. Critical-thinking skills can cross over to any of students’ other courses and into life outside the classroom. After all, we as teachers want to help the whole student be successful, and critical thinking is an important part of navigating life after they leave our classrooms.

‘Before-Explore-Explain’

Patrick Brown is the executive director of STEM and CTE for the Fort Zumwalt school district in Missouri and an experienced educator and author :

Planning for critical thinking focuses on teaching the most crucial science concepts, practices, and logical-thinking skills as well as the best use of instructional time. One way to ensure that lessons maintain a focus on critical thinking is to focus on the instructional sequence used to teach.

Explore-before-explain teaching is all about promoting critical thinking for learners to better prepare students for the reality of their world. What having an explore-before-explain mindset means is that in our planning, we prioritize giving students firsthand experiences with data, allow students to construct evidence-based claims that focus on conceptual understanding, and challenge students to discuss and think about the why behind phenomena.

Just think of the critical thinking that has to occur for students to construct a scientific claim. 1) They need the opportunity to collect data, analyze it, and determine how to make sense of what the data may mean. 2) With data in hand, students can begin thinking about the validity and reliability of their experience and information collected. 3) They can consider what differences, if any, they might have if they completed the investigation again. 4) They can scrutinize outlying data points for they may be an artifact of a true difference that merits further exploration of a misstep in the procedure, measuring device, or measurement. All of these intellectual activities help them form more robust understanding and are evidence of their critical thinking.

In explore-before-explain teaching, all of these hard critical-thinking tasks come before teacher explanations of content. Whether we use discovery experiences, problem-based learning, and or inquiry-based activities, strategies that are geared toward helping students construct understanding promote critical thinking because students learn content by doing the practices valued in the field to generate knowledge.

An Issue of Equity

Meg Riordan, Ph.D., is the chief learning officer at The Possible Project, an out-of-school program that collaborates with youth to build entrepreneurial skills and mindsets and provides pathways to careers and long-term economic prosperity. She has been in the field of education for over 25 years as a middle and high school teacher, school coach, college professor, regional director of N.Y.C. Outward Bound Schools, and director of external research with EL Education:

Although critical thinking often defies straightforward definition, most in the education field agree it consists of several components: reasoning, problem-solving, and decisionmaking, plus analysis and evaluation of information, such that multiple sides of an issue can be explored. It also includes dispositions and “the willingness to apply critical-thinking principles, rather than fall back on existing unexamined beliefs, or simply believe what you’re told by authority figures.”

Despite variation in definitions, critical thinking is nonetheless promoted as an essential outcome of students’ learning—we want to see students and adults demonstrate it across all fields, professions, and in their personal lives. Yet there is simultaneously a rationing of opportunities in schools for students of color, students from under-resourced communities, and other historically marginalized groups to deeply learn and practice critical thinking.

For example, many of our most underserved students often spend class time filling out worksheets, promoting high compliance but low engagement, inquiry, critical thinking, or creation of new ideas. At a time in our world when college and careers are critical for participation in society and the global, knowledge-based economy, far too many students struggle within classrooms and schools that reinforce low-expectations and inequity.

If educators aim to prepare all students for an ever-evolving marketplace and develop skills that will be valued no matter what tomorrow’s jobs are, then we must move critical thinking to the forefront of classroom experiences. And educators must design learning to cultivate it.

So, what does that really look like?

Unpack and define critical thinking

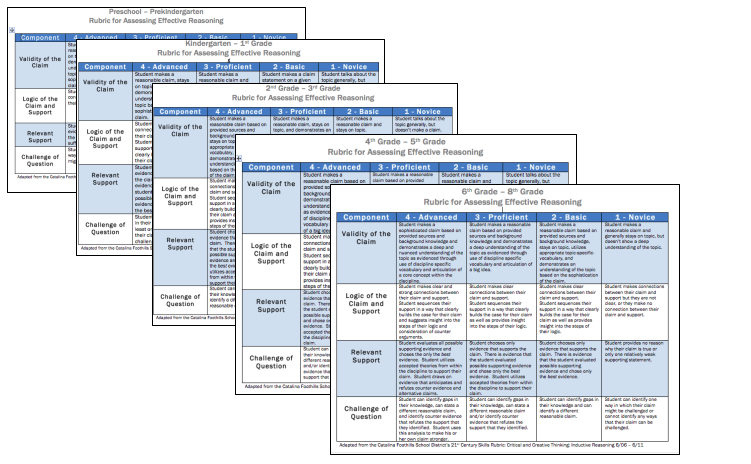

To understand critical thinking, educators need to first unpack and define its components. What exactly are we looking for when we speak about reasoning or exploring multiple perspectives on an issue? How does problem-solving show up in English, math, science, art, or other disciplines—and how is it assessed? At Two Rivers, an EL Education school, the faculty identified five constructs of critical thinking, defined each, and created rubrics to generate a shared picture of quality for teachers and students. The rubrics were then adapted across grade levels to indicate students’ learning progressions.

At Avenues World School, critical thinking is one of the Avenues World Elements and is an enduring outcome embedded in students’ early experiences through 12th grade. For instance, a kindergarten student may be expected to “identify cause and effect in familiar contexts,” while an 8th grader should demonstrate the ability to “seek out sufficient evidence before accepting a claim as true,” “identify bias in claims and evidence,” and “reconsider strongly held points of view in light of new evidence.”

When faculty and students embrace a common vision of what critical thinking looks and sounds like and how it is assessed, educators can then explicitly design learning experiences that call for students to employ critical-thinking skills. This kind of work must occur across all schools and programs, especially those serving large numbers of students of color. As Linda Darling-Hammond asserts , “Schools that serve large numbers of students of color are least likely to offer the kind of curriculum needed to ... help students attain the [critical-thinking] skills needed in a knowledge work economy. ”

So, what can it look like to create those kinds of learning experiences?

Designing experiences for critical thinking

After defining a shared understanding of “what” critical thinking is and “how” it shows up across multiple disciplines and grade levels, it is essential to create learning experiences that impel students to cultivate, practice, and apply these skills. There are several levers that offer pathways for teachers to promote critical thinking in lessons:

1.Choose Compelling Topics: Keep it relevant

A key Common Core State Standard asks for students to “write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.” That might not sound exciting or culturally relevant. But a learning experience designed for a 12th grade humanities class engaged learners in a compelling topic— policing in America —to analyze and evaluate multiple texts (including primary sources) and share the reasoning for their perspectives through discussion and writing. Students grappled with ideas and their beliefs and employed deep critical-thinking skills to develop arguments for their claims. Embedding critical-thinking skills in curriculum that students care about and connect with can ignite powerful learning experiences.

2. Make Local Connections: Keep it real

At The Possible Project , an out-of-school-time program designed to promote entrepreneurial skills and mindsets, students in a recent summer online program (modified from in-person due to COVID-19) explored the impact of COVID-19 on their communities and local BIPOC-owned businesses. They learned interviewing skills through a partnership with Everyday Boston , conducted virtual interviews with entrepreneurs, evaluated information from their interviews and local data, and examined their previously held beliefs. They created blog posts and videos to reflect on their learning and consider how their mindsets had changed as a result of the experience. In this way, we can design powerful community-based learning and invite students into productive struggle with multiple perspectives.

3. Create Authentic Projects: Keep it rigorous

At Big Picture Learning schools, students engage in internship-based learning experiences as a central part of their schooling. Their school-based adviser and internship-based mentor support them in developing real-world projects that promote deeper learning and critical-thinking skills. Such authentic experiences teach “young people to be thinkers, to be curious, to get from curiosity to creation … and it helps students design a learning experience that answers their questions, [providing an] opportunity to communicate it to a larger audience—a major indicator of postsecondary success.” Even in a remote environment, we can design projects that ask more of students than rote memorization and that spark critical thinking.

Our call to action is this: As educators, we need to make opportunities for critical thinking available not only to the affluent or those fortunate enough to be placed in advanced courses. The tools are available, let’s use them. Let’s interrogate our current curriculum and design learning experiences that engage all students in real, relevant, and rigorous experiences that require critical thinking and prepare them for promising postsecondary pathways.

Critical Thinking & Student Engagement

Dr. PJ Caposey is an award-winning educator, keynote speaker, consultant, and author of seven books who currently serves as the superintendent of schools for the award-winning Meridian CUSD 223 in northwest Illinois. You can find PJ on most social-media platforms as MCUSDSupe:

When I start my keynote on student engagement, I invite two people up on stage and give them each five paper balls to shoot at a garbage can also conveniently placed on stage. Contestant One shoots their shot, and the audience gives approval. Four out of 5 is a heckuva score. Then just before Contestant Two shoots, I blindfold them and start moving the garbage can back and forth. I usually try to ensure that they can at least make one of their shots. Nobody is successful in this unfair environment.

I thank them and send them back to their seats and then explain that this little activity was akin to student engagement. While we all know we want student engagement, we are shooting at different targets. More importantly, for teachers, it is near impossible for them to hit a target that is moving and that they cannot see.

Within the world of education and particularly as educational leaders, we have failed to simplify what student engagement looks like, and it is impossible to define or articulate what student engagement looks like if we cannot clearly articulate what critical thinking is and looks like in a classroom. Because, simply, without critical thought, there is no engagement.

The good news here is that critical thought has been defined and placed into taxonomies for decades already. This is not something new and not something that needs to be redefined. I am a Bloom’s person, but there is nothing wrong with DOK or some of the other taxonomies, either. To be precise, I am a huge fan of Daggett’s Rigor and Relevance Framework. I have used that as a core element of my practice for years, and it has shaped who I am as an instructional leader.

So, in order to explain critical thought, a teacher or a leader must familiarize themselves with these tried and true taxonomies. Easy, right? Yes, sort of. The issue is not understanding what critical thought is; it is the ability to integrate it into the classrooms. In order to do so, there are a four key steps every educator must take.

- Integrating critical thought/rigor into a lesson does not happen by chance, it happens by design. Planning for critical thought and engagement is much different from planning for a traditional lesson. In order to plan for kids to think critically, you have to provide a base of knowledge and excellent prompts to allow them to explore their own thinking in order to analyze, evaluate, or synthesize information.

- SIDE NOTE – Bloom’s verbs are a great way to start when writing objectives, but true planning will take you deeper than this.

QUESTIONING

- If the questions and prompts given in a classroom have correct answers or if the teacher ends up answering their own questions, the lesson will lack critical thought and rigor.

- Script five questions forcing higher-order thought prior to every lesson. Experienced teachers may not feel they need this, but it helps to create an effective habit.

- If lessons are rigorous and assessments are not, students will do well on their assessments, and that may not be an accurate representation of the knowledge and skills they have mastered. If lessons are easy and assessments are rigorous, the exact opposite will happen. When deciding to increase critical thought, it must happen in all three phases of the game: planning, instruction, and assessment.

TALK TIME / CONTROL

- To increase rigor, the teacher must DO LESS. This feels counterintuitive but is accurate. Rigorous lessons involving tons of critical thought must allow for students to work on their own, collaborate with peers, and connect their ideas. This cannot happen in a silent room except for the teacher talking. In order to increase rigor, decrease talk time and become comfortable with less control. Asking questions and giving prompts that lead to no true correct answer also means less control. This is a tough ask for some teachers. Explained differently, if you assign one assignment and get 30 very similar products, you have most likely assigned a low-rigor recipe. If you assign one assignment and get multiple varied products, then the students have had a chance to think deeply, and you have successfully integrated critical thought into your classroom.

Thanks to Dara, Patrick, Meg, and PJ for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones won’t be available until February). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

- Race & Racism in Schools

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Facing Gender Challenges in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech in the Classroom

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in Schools

- Teaching English-Language Learners

- Reading Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- Entering the Teaching Profession

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in Schools

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- Our Mission

Helping Students Hone Their Critical Thinking Skills

Used consistently, these strategies can help middle and high school teachers guide students to improve much-needed skills.

Critical thinking skills are important in every discipline, at and beyond school. From managing money to choosing which candidates to vote for in elections to making difficult career choices, students need to be prepared to take in, synthesize, and act on new information in a world that is constantly changing.

While critical thinking might seem like an abstract idea that is tough to directly instruct, there are many engaging ways to help students strengthen these skills through active learning.

Make Time for Metacognitive Reflection

Create space for students to both reflect on their ideas and discuss the power of doing so. Show students how they can push back on their own thinking to analyze and question their assumptions. Students might ask themselves, “Why is this the best answer? What information supports my answer? What might someone with a counterargument say?”

Through this reflection, students and teachers (who can model reflecting on their own thinking) gain deeper understandings of their ideas and do a better job articulating their beliefs. In a world that is go-go-go, it is important to help students understand that it is OK to take a breath and think about their ideas before putting them out into the world. And taking time for reflection helps us more thoughtfully consider others’ ideas, too.

Teach Reasoning Skills

Reasoning skills are another key component of critical thinking, involving the abilities to think logically, evaluate evidence, identify assumptions, and analyze arguments. Students who learn how to use reasoning skills will be better equipped to make informed decisions, form and defend opinions, and solve problems.

One way to teach reasoning is to use problem-solving activities that require students to apply their skills to practical contexts. For example, give students a real problem to solve, and ask them to use reasoning skills to develop a solution. They can then present their solution and defend their reasoning to the class and engage in discussion about whether and how their thinking changed when listening to peers’ perspectives.

A great example I have seen involved students identifying an underutilized part of their school and creating a presentation about one way to redesign it. This project allowed students to feel a sense of connection to the problem and come up with creative solutions that could help others at school. For more examples, you might visit PBS’s Design Squad , a resource that brings to life real-world problem-solving.

Ask Open-Ended Questions

Moving beyond the repetition of facts, critical thinking requires students to take positions and explain their beliefs through research, evidence, and explanations of credibility.

When we pose open-ended questions, we create space for classroom discourse inclusive of diverse, perhaps opposing, ideas—grounds for rich exchanges that support deep thinking and analysis.

For example, “How would you approach the problem?” and “Where might you look to find resources to address this issue?” are two open-ended questions that position students to think less about the “right” answer and more about the variety of solutions that might already exist.

Journaling, whether digitally or physically in a notebook, is another great way to have students answer these open-ended prompts—giving them time to think and organize their thoughts before contributing to a conversation, which can ensure that more voices are heard.

Once students process in their journal, small group or whole class conversations help bring their ideas to life. Discovering similarities between answers helps reveal to students that they are not alone, which can encourage future participation in constructive civil discourse.

Teach Information Literacy

Education has moved far past the idea of “Be careful of what is on Wikipedia, because it might not be true.” With AI innovations making their way into classrooms, teachers know that informed readers must question everything.

Understanding what is and is not a reliable source and knowing how to vet information are important skills for students to build and utilize when making informed decisions. You might start by introducing the idea of bias: Articles, ads, memes, videos, and every other form of media can push an agenda that students may not see on the surface. Discuss credibility, subjectivity, and objectivity, and look at examples and nonexamples of trusted information to prepare students to be well-informed members of a democracy.

One of my favorite lessons is about the Pacific Northwest tree octopus . This project asks students to explore what appears to be a very real website that provides information on this supposedly endangered animal. It is a wonderful, albeit over-the-top, example of how something might look official even when untrue, revealing that we need critical thinking to break down “facts” and determine the validity of the information we consume.

A fun extension is to have students come up with their own website or newsletter about something going on in school that is untrue. Perhaps a change in dress code that requires everyone to wear their clothes inside out or a change to the lunch menu that will require students to eat brussels sprouts every day.

Giving students the ability to create their own falsified information can help them better identify it in other contexts. Understanding that information can be “too good to be true” can help them identify future falsehoods.

Provide Diverse Perspectives

Consider how to keep the classroom from becoming an echo chamber. If students come from the same community, they may have similar perspectives. And those who have differing perspectives may not feel comfortable sharing them in the face of an opposing majority.

To support varying viewpoints, bring diverse voices into the classroom as much as possible, especially when discussing current events. Use primary sources: videos from YouTube, essays and articles written by people who experienced current events firsthand, documentaries that dive deeply into topics that require some nuance, and any other resources that provide a varied look at topics.

I like to use the Smithsonian “OurStory” page , which shares a wide variety of stories from people in the United States. The page on Japanese American internment camps is very powerful because of its first-person perspectives.

Practice Makes Perfect

To make the above strategies and thinking routines a consistent part of your classroom, spread them out—and build upon them—over the course of the school year. You might challenge students with information and/or examples that require them to use their critical thinking skills; work these skills explicitly into lessons, projects, rubrics, and self-assessments; or have students practice identifying misinformation or unsupported arguments.

Critical thinking is not learned in isolation. It needs to be explored in English language arts, social studies, science, physical education, math. Every discipline requires students to take a careful look at something and find the best solution. Often, these skills are taken for granted, viewed as a by-product of a good education, but true critical thinking doesn’t just happen. It requires consistency and commitment.

In a moment when information and misinformation abound, and students must parse reams of information, it is imperative that we support and model critical thinking in the classroom to support the development of well-informed citizens.

How to teach critical thinking, a vital 21st-century skill

A well-rounded education doesn’t just impart academic knowledge to students — it gives them transferable skills they can apply throughout their lives. Critical thinking is widely hailed as one such essential “ 21st-century skill ,” helping people critically assess information, make informed decisions, and come up with creative approaches to solving problems.

This means that individuals with developed critical thinking skills benefit both themselves and the wider society. Despite the widespread recognition of critical thinking’s importance for future success, there can be some ambiguity about both what it is and how to teach it . 1 Let’s take a look at each of those questions in turn.

What is critical thinking?

Throughout history, humanity has attempted to use reason to understand and interpret the world. From the philosophers of Ancient Greece to the key thinkers of the Enlightenment, people have sought to challenge their preconceived notions and draw logical conclusions from the available evidence — key elements that gave rise to today’s definition of “critical thinking.”

At its core, critical thinking is the use of reason to analyze the available evidence and reach logical conclusions. Educational scholars have defined critical thinking as “reasonable reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do,” 2 and “interpretation or analysis, followed by evaluation or judgment.” 3 Some have pared their definition down to simply “good” or “skillful thinking.”

At the same time, being a good critical thinker relies on certain values like open-mindedness, persistence, and intellectual humility. 4 The ideal critical thinker isn’t just skilled in analysis — they are also curious, open to other points of view, and creative in the path they take towards tackling a given problem.

Alongside teaching students how to analyze information, build arguments, and draw conclusions, educators play a key role in fostering the values conducive to critical thinking and intellectual inquiry. Students who develop both skills and values are well-placed to handle challenges both academically and in their personal lives.

Let’s examine some strategies to develop critical thinking skills and values in the classroom.

How to teach students to think critically — strategies

1. build a classroom climate that encourages open-mindedness.

Fostering a classroom culture that allows students the time and space to think independently, experiment with new ideas, and have their views challenged lays a strong foundation for developing skills and values central to critical thinking.

Whatever your subject area, encourage students to contribute their own ideas and theories when addressing common curricular questions. Promote open-mindedness by underscoring the importance of the initial “brainstorming” phase in problem-solving — this is the necessary first step towards understanding! Strive to create a classroom climate where students are comfortable thinking out loud.

Emphasize to students the importance of understanding different perspectives on issues, and that it’s okay for people to disagree. Establish guidelines for class discussions — especially when covering controversial issues — and stress that changing your mind on an issue is a sign of intellectual strength, not weakness. Model positive behaviors by being flexible in your own opinions when engaging with ideas from students.

2. Teach students to make clear and effective arguments

Training students’ argumentation skills is central to turning them into adept critical thinkers. Expose students to a wide range of arguments, guiding them to distinguish between examples of good and bad reasoning.

When guiding students to form their own arguments, emphasize the value of clarity and precision in language. In oral discussions, encourage students to order their thoughts on paper before contributing.

In the case of argumentative essays , give students plenty of opportunities to revise their work, implementing feedback from you or peers. Assist students in refining their arguments by encouraging them to challenge their own positions.

They can do so by creating robust “steel man” counterarguments to identify potential flaws in their own reasoning. For example, if a student is passionate about animal rights and wants to argue for a ban on animal testing , encourage them to also come up with points in favor of animal testing. If they can rebut those counterarguments, their own position will be much stronger!

Additionally, knowing how to evaluate and provide evidence is essential for developing argumentation skills. Teach students how to properly cite sources , and encourage them to investigate the veracity of claims made by others — particularly when dealing with online media .

3. Encourage metacognition — guide students to think about their own and others’ thinking

Critical thinkers are self-reflective. Guide students time to think about their own learning process by utilizing metacognitive strategies, like learning journals or having reflective periods at the end of activities. Reflecting on how they came to understand a topic can help students cultivate a growth mindset and an openness to explore alternative problem-solving approaches during challenging moments.

You can also create an awareness of common errors in human thinking by teaching about them explicitly. Identify arguments based on logical fallacies and have students come up with examples from their own experience. Help students recognize the role of cognitive bias in our thinking, and design activities to help counter it.

Students who develop self-awareness regarding their own thinking are not just better at problem-solving, but also managing their emotions .

4. Assign open-ended and varied activities to practice different kinds of thinking

Critical thinkers are capable of approaching problems from a variety of angles. Train this vital habit by switching up the kinds of activities you assign to students, and try prioritizing open-ended assignments that allow for varied approaches.

A project-based learning approach can reap huge rewards. Have students identify real-world problems, conduct research, and investigate potential solutions. Following that process will give them varied intellectual challenges, while the real-world applicability of their work can motivate students to consider the potential impact their thinking can have on the world around them.

Classroom discussions and debates are fantastic activities for building critical thinking skills. As open-ended activities, they encourage student autonomy by requiring them to think for themselves.

They also expose students to a diversity of perspectives , inviting them to critically appraise these different positions in a respectful context. Class discussions are applicable across disciplines and come in many flavors — experiment with different forms like fishbowl discussions or online, asynchronous discussions to keep students engaged.

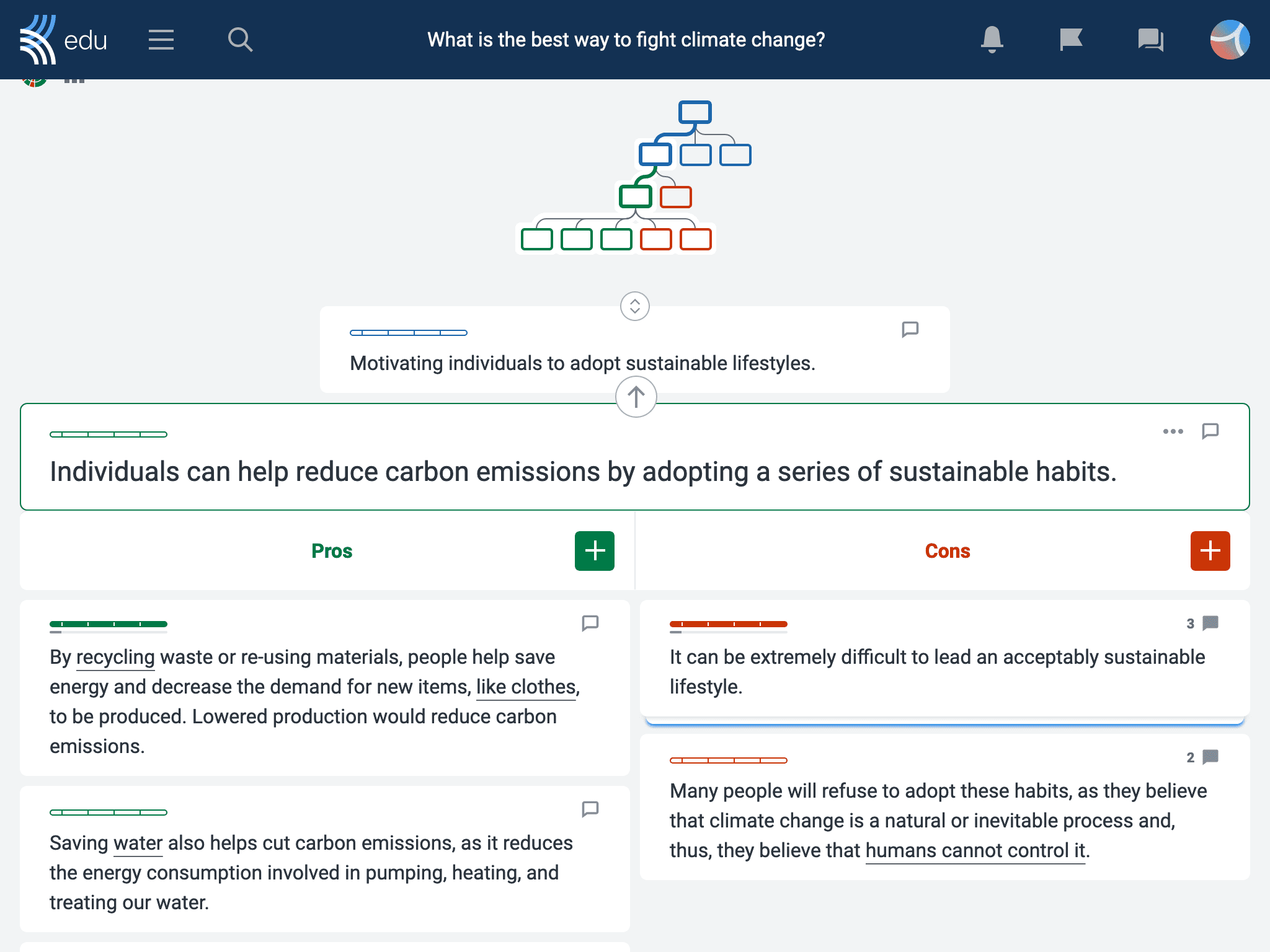

5. Use argument-mapping tools such as Kialo Edu to train students in the use of reasoning

One of the most effective methods of improving students’ critical thinking skills is to train them in argument mapping .

Argument mapping involves breaking an argument down into its constituent parts, and displaying them visually so that students can see how different points are connected. Research has shown that university students who were trained in argument mapping significantly out-performed their peers on critical thinking assessments. 5

While it’s possible — and useful — to map out arguments by hand, there are clear benefits to using digital argument maps like Kialo Edu. Students can contribute simultaneously to a Kialo discussion to collaboratively build out complex discussions as an argument map.

Individual students can plan essays as argument maps before writing. This helps them to stay focused on the line of argument and encourages them to preempt counterarguments. Kialo discussions can even be assigned as an essay alternative when teachers want to focus on argumentation as the key learning goal. Unlike traditional essays, they defy the use of AI chatbots like ChatGPT!

Kialo discussions prompt students to use their reasoning skills to create clear, structured arguments. Moreover, students have a visual, engaging way to respond to the content of the arguments being made, promoting interpretive charity towards differing opinions.

Best of all, Kialo Edu offers a way to track and assess your students’ progress on their critical thinking journey. Educators can assign specific tasks — like citing sources or responding to others’ claims — to evaluate specific skills. Students can also receive grades and feedback on their contributions without leaving the platform, making it easy to deliver constructive, ongoing guidance to help students develop their reasoning skills.

Improving students’ critical thinking abilities is something that motivates our work here at Kialo Edu. If you’ve used our platform and have feedback, thoughts, or suggestions, we’d love to hear from you. Reach out to us on social media or contact us directly at [email protected] .

- Lloyd, M., & Bahr, N. (2010). Thinking Critically about Critical Thinking in Higher Education. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 4 (2), Article 9. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2010.040209

- Ennis, R. H. (2015). Critical Thinking: A Streamlined Conception. In: Davies, M., Barnett, R. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

- Lang-Raad, N. D. (2023). Never Stop Asking: Teaching Students to be Better Critical Thinkers . Jossey-Bass.

- Ellerton, Peter (2019). Teaching for thinking: Explaining pedagogical expertise in the development of the skills, values and virtues of inquiry . Dissertation, The University of Queensland. Available here .

- van Gelder, T. (2015). Using argument mapping to improve critical thinking skills. In The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education (pp. 183–192). doi:10.1057/9781137378057_12.

Want to try Kialo Edu with your class?

Sign up for free and use Kialo Edu to have thoughtful classroom discussions and train students’ argumentation and critical thinking skills.

Why Schools Need to Change Yes, We Can Define, Teach, and Assess Critical Thinking Skills

Jeff Heyck-Williams (He, His, Him) Director of the Two Rivers Learning Institute in Washington, DC

Today’s learners face an uncertain present and a rapidly changing future that demand far different skills and knowledge than were needed in the 20th century. We also know so much more about enabling deep, powerful learning than we ever did before. Our collective future depends on how well young people prepare for the challenges and opportunities of 21st-century life.

Critical thinking is a thing. We can define it; we can teach it; and we can assess it.

While the idea of teaching critical thinking has been bandied around in education circles since at least the time of John Dewey, it has taken greater prominence in the education debates with the advent of the term “21st century skills” and discussions of deeper learning. There is increasing agreement among education reformers that critical thinking is an essential ingredient for long-term success for all of our students.

However, there are still those in the education establishment and in the media who argue that critical thinking isn’t really a thing, or that these skills aren’t well defined and, even if they could be defined, they can’t be taught or assessed.

To those naysayers, I have to disagree. Critical thinking is a thing. We can define it; we can teach it; and we can assess it. In fact, as part of a multi-year Assessment for Learning Project , Two Rivers Public Charter School in Washington, D.C., has done just that.

Before I dive into what we have done, I want to acknowledge that some of the criticism has merit.

First, there are those that argue that critical thinking can only exist when students have a vast fund of knowledge. Meaning that a student cannot think critically if they don’t have something substantive about which to think. I agree. Students do need a robust foundation of core content knowledge to effectively think critically. Schools still have a responsibility for building students’ content knowledge.

However, I would argue that students don’t need to wait to think critically until after they have mastered some arbitrary amount of knowledge. They can start building critical thinking skills when they walk in the door. All students come to school with experience and knowledge which they can immediately think critically about. In fact, some of the thinking that they learn to do helps augment and solidify the discipline-specific academic knowledge that they are learning.

The second criticism is that critical thinking skills are always highly contextual. In this argument, the critics make the point that the types of thinking that students do in history is categorically different from the types of thinking students do in science or math. Thus, the idea of teaching broadly defined, content-neutral critical thinking skills is impossible. I agree that there are domain-specific thinking skills that students should learn in each discipline. However, I also believe that there are several generalizable skills that elementary school students can learn that have broad applicability to their academic and social lives. That is what we have done at Two Rivers.

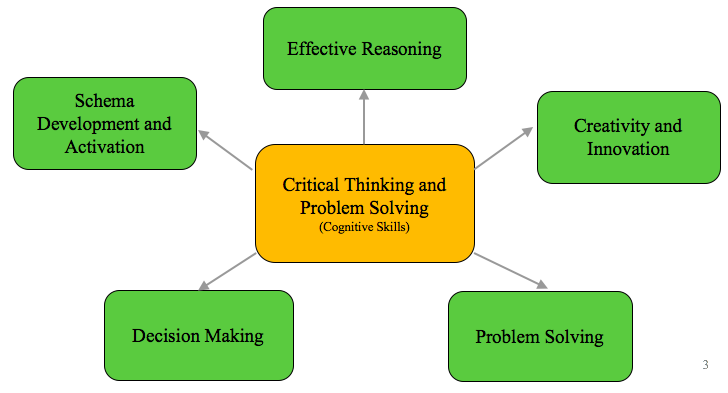

Defining Critical Thinking Skills

We began this work by first defining what we mean by critical thinking. After a review of the literature and looking at the practice at other schools, we identified five constructs that encompass a set of broadly applicable skills: schema development and activation; effective reasoning; creativity and innovation; problem solving; and decision making.

We then created rubrics to provide a concrete vision of what each of these constructs look like in practice. Working with the Stanford Center for Assessment, Learning and Equity (SCALE) , we refined these rubrics to capture clear and discrete skills.

For example, we defined effective reasoning as the skill of creating an evidence-based claim: students need to construct a claim, identify relevant support, link their support to their claim, and identify possible questions or counter claims. Rubrics provide an explicit vision of the skill of effective reasoning for students and teachers. By breaking the rubrics down for different grade bands, we have been able not only to describe what reasoning is but also to delineate how the skills develop in students from preschool through 8th grade.

Before moving on, I want to freely acknowledge that in narrowly defining reasoning as the construction of evidence-based claims we have disregarded some elements of reasoning that students can and should learn. For example, the difference between constructing claims through deductive versus inductive means is not highlighted in our definition. However, by privileging a definition that has broad applicability across disciplines, we are able to gain traction in developing the roots of critical thinking. In this case, to formulate well-supported claims or arguments.

Teaching Critical Thinking Skills

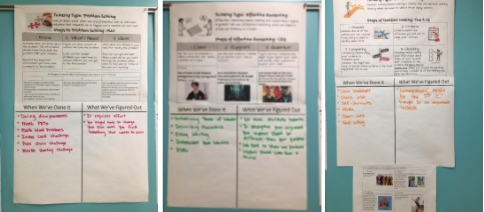

The definitions of critical thinking constructs were only useful to us in as much as they translated into practical skills that teachers could teach and students could learn and use. Consequently, we have found that to teach a set of cognitive skills, we needed thinking routines that defined the regular application of these critical thinking and problem-solving skills across domains. Building on Harvard’s Project Zero Visible Thinking work, we have named routines aligned with each of our constructs.

For example, with the construct of effective reasoning, we aligned the Claim-Support-Question thinking routine to our rubric. Teachers then were able to teach students that whenever they were making an argument, the norm in the class was to use the routine in constructing their claim and support. The flexibility of the routine has allowed us to apply it from preschool through 8th grade and across disciplines from science to economics and from math to literacy.

Kathryn Mancino, a 5th grade teacher at Two Rivers, has deliberately taught three of our thinking routines to students using the anchor charts above. Her charts name the components of each routine and has a place for students to record when they’ve used it and what they have figured out about the routine. By using this structure with a chart that can be added to throughout the year, students see the routines as broadly applicable across disciplines and are able to refine their application over time.

Assessing Critical Thinking Skills

By defining specific constructs of critical thinking and building thinking routines that support their implementation in classrooms, we have operated under the assumption that students are developing skills that they will be able to transfer to other settings. However, we recognized both the importance and the challenge of gathering reliable data to confirm this.

With this in mind, we have developed a series of short performance tasks around novel discipline-neutral contexts in which students can apply the constructs of thinking. Through these tasks, we have been able to provide an opportunity for students to demonstrate their ability to transfer the types of thinking beyond the original classroom setting. Once again, we have worked with SCALE to define tasks where students easily access the content but where the cognitive lift requires them to demonstrate their thinking abilities.

These assessments demonstrate that it is possible to capture meaningful data on students’ critical thinking abilities. They are not intended to be high stakes accountability measures. Instead, they are designed to give students, teachers, and school leaders discrete formative data on hard to measure skills.

While it is clearly difficult, and we have not solved all of the challenges to scaling assessments of critical thinking, we can define, teach, and assess these skills . In fact, knowing how important they are for the economy of the future and our democracy, it is essential that we do.

Jeff Heyck-Williams (He, His, Him)

Director of the two rivers learning institute.

Jeff Heyck-Williams is the director of the Two Rivers Learning Institute and a founder of Two Rivers Public Charter School. He has led work around creating school-wide cultures of mathematics, developing assessments of critical thinking and problem-solving, and supporting project-based learning.

Read More About Why Schools Need to Change

Bring Your Vision for Student Success to Life with NGLC and Bravely

March 13, 2024

For Ethical AI, Listen to Teachers

Jason Wilmot

October 23, 2023

Turning School Libraries into Discipline Centers Is Not the Answer to Disruptive Classroom Behavior

Stephanie McGary

October 4, 2023

Complementary strategies for teaching collaboration and critical thinking skills

Subscribe to the center for universal education bulletin, tara barnett , tb tara barnett 4th grade teacher - knollwood school, fair haven, new jersey ben lawless , bl ben lawless history teacher - aiken college, melbourne, australia helyn kim , and helyn kim former brookings expert @helyn_kim alvin vista alvin vista former brookings expert @alvin_vista.

December 12, 2017

This is the fifth piece in a six-part blog series on teaching 21st century skills , including problem solving , metacognition , critical thinking , and collaboration, in classrooms.

In today’s changing world, students need a broader range of skills beyond traditional academic subject areas that they can apply to a wide range of real-life situations. Students will encounter many future situations where they have to bring together multiple complex skills to complete tasks. Using examples from the U.S. and Australia, we will outline two complementary methods that teach these complex skillsets. In the U.S., a 4th grade reading class uses a method to develop collaboration skills, while simultaneously developing critical thinking skills. Similarly, an example from Australia will show how a secondary level history class also teaches these two skills simultaneously, but with a different method.

An American classroom

Being able to discuss our ideas and opinions thoughtfully with others is a crucial life skill. Collaborative discussion relies on peer interaction, communication, sharing, and at times expert guidance to extend student thinking. Students—not teachers—should drive conversations as they present, defend, elaborate upon, and respond to each other. As they make connections, they will clarify their understanding, refine their thinking, and synthesize information. To help illustrate this important skill, Tara Barnett, a 4th grade teacher in Fair Haven, New Jersey, supports and enhances collaborative talk through a number of strategies.

When Tara thinks back to her own schooling, she remembers the many times she was asked questions designed to check her knowledge; rarely was she asked to engage in discussion around a text or issue. Now, it is common practice to ask students to turn and talk to each other. However, it is not enough just to provide opportunities; teachers need to teach collaborative discussion skills explicitly and systematically. Tara uses accountable talk stems as a strategy to structure meaningful conversation. This gives students the language they need to engage in discussion with each other. All too often, however, students go through the motions of talking without full engagement. Kids will say, “I agree” or “I disagree” and even give reasons, but conversations often stay at a surface level. They seem to think that using these phrases are the end rather than a means to an end.

To address this issue in classrooms, use the following strategies—they are related to literacy lessons but can, of course, be applied more widely.

1) Launch entire-class conversations before moving students to less-supported conversations with partners. Beginning with the entire class helps to establish norms for conversation in the classroom and gives a model for what a conversation can and should look like.

2) Give students a question in which they have to take a stance . In order to have good discussions, ideas need to be worth discussing. If the idea is simply stating the obvious or agreeing with a previously mentioned idea, the conversation will stall.

3) If you use accountable talk stems, preface them as a “way to enter the conversation” and list 1-2 stems for each path. The stems support students in thinking about what they are trying to accomplish by making their talk more purposeful and thoughtful. It might look something like what is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Entering a conversation

4) Explicitly teach vocabulary that will support students to enter a discussion. For example, when we want to discuss the characters in Fox by Margaret Wild and Ron Brooks , we introduce words like cunning , optimistic, and pessimistic . After introducing students to these words, they begin to see the connections between the words and the characters, which prompts students to use them in a discussion. Vocabulary support is a game changer for students.

5) Once students are having discussions more independently, have them record their discussions for the purpose of self-assessment. After the discussion, they can watch their discussion and ask themselves questions such as:

- Is there one person who is overpowering the discussion or one person who isn’t getting a chance to say much?

- Are we sticking with a topic for at least one round, maybe more? (Teach the students that they should be “catching” ideas and not just bouncing from one idea to the next like popcorn.)

Students can use their self-assessment to set goals. Reflection and goal setting really helps focus and elevate conversations and makes students accountable to themselves—an essential learning to learn characteristic.

An Australian classroom

On the other side of the world, Ben teaches secondary students at Aitken College, a co-educational independent school in Melbourne, Australia. Although Ben’s class subject is History, when people ask him what he teaches, Ben points out that he teaches “conceptual analysis.” This is his approach to developing critical thinking skills in a collaborative setting as the students learn history. Irrespective of the content or skills learned the ability to analyze material and concepts is crucial.

Conceptual analysis can be applied to building structures based on hierarchies or progressions, such as when students are tasked to create their own developmental or progression-based rubrics . It is important to demonstrate to students how rubrics are created and why they are useful because understanding rubrics also helps them structure their task output to match the task requirements. To help them with this skill, have the students to generate a rubric together. Pick a common school assignment, such as a history essay. Ask students to list some of the skills they use when producing a history essay; support the students in doing this by querying statements of what they produce to help them distinguish the actual processes they use. Choose three or four of these processes. Now ask students to describe what different levels of quality of these processes would look like, i.e., a description of an advanced example, and a middle-level example, and a basic level example.

Figure 2. Analyzing the skills used in a history essay

Figure 2 shows how this class activity would look like when completed as a grid, where for each step in “researching,” the students provided what they think are different levels of quality. Students are demonstrating sub-skills that are important components of conceptual analysis: differentiating, organizing, and attributing. They are differentiating by recognizing that the words generated in a brainstorm can be classified. They are organizing by placing them in different categories. We could extend the task by asking students to come up with sub-categories and sub-sub-categories. This helps students deconstruct a concept. Students who can understand how to break a task down like this are much more likely to develop and demonstrate the skills and sub-skills involved. With this task, we could also show students a few examples of other student work and ask them to grade them according to the rubric they created.

Critical thinking is a systematic way of looking at the world for the purposes of reasoning and making decisions effectively. Although we may define critical thinking in a more complex manner, it is essentially a practical or applied activity because reasoning and decisionmaking are applied activities. Conceptual analysis is a useful tool to help students do critical thinking activities collaboratively, and it can be taught in a team-based or collaborative setting.

Both conceptual analysis and collaborative discussion strategies show that they can be applied practically in diverse classroom tasks for teaching multiple complex skills such as working collaboratively and thinking critically—two of the 21st century skills that will become increasingly important as the new generation of students move into the workforce of the future.

Related Content

Loren Clarke, Esther Care

December 5, 2017

Kate Mills, Helyn Kim

October 31, 2017

Esther Care, Helyn Kim, Alvin Vista

October 17, 2017

Global Education K-12 Education

Global Economy and Development

Center for Universal Education

Ariell Bertrand, Melissa Arnold Lyon, Rebecca Jacobsen

April 18, 2024

Modupe (Mo) Olateju, Grace Cannon

April 15, 2024

Phillip Levine

April 12, 2024

Radiologic Technology

Skip to main page content

- CURRENT ISSUE

- Institution: Google Indexer

Review of Teaching Methods and Critical Thinking Skills

- NINA KOWALCZYK , PhD, R.T.(R)(CT)(QM), FASRT

Background Critical information is needed to inform radiation science educators regarding successful critical thinking educational strategies. From an evidence-based research perspective, systematic reviews are identified as the most current and highest level of evidence. Analysis at this high level is crucial in analyzing those teaching methods most appropriate to the development of critical thinking skills.

Objectives To conduct a systematic literature review to identify teaching methods that demonstrate a positive effect on the development of students’ critical thinking skills and to identify how these teaching strategies can best translate to radiologic science educational programs.

Methods A comprehensive literature search was conducted resulting in an assessment of 59 full reports. Nineteen of the 59 reports met inclusion criteria and were reviewed based on the level of evidence presented. Inclusion criteria included studies conducted in the past 10 years on sample sizes of 20 or more individuals demonstrating use of specific teaching interventions for 5 to 36 months in postsecondary health-related educational programs.

Results The majority of the research focused on problem-based learning (PBL) requiring standardized small-group activities. Six of the 19 studies focused on PBL and demonstrated significant differences in student critical thinking scores.

Conclusion PBL, as described in the nursing literature, is an effective teaching method that should be used in radiation science education.

This Article

- radtech November/December 2011 vol. 83 no. 2 120-132

- Full Text (PDF)

Classifications

- Peer Reviewed

- Email this article to a colleague

- Alert me when this article is cited

- Alert me if a correction is posted

- Similar articles in this journal

- Similar articles in Web of Science

- Download to citation manager

Citing Articles

- Load citing article information

- Citing articles via Web of Science

- Citing articles via Google Scholar

Google Scholar

- Articles by KOWALCZYK, N.

- Search for related content

Related Content

- Load related web page information

This Week's Issue

- March-April 2024, 95 (4)

- Alert me to new issues of radtech

- Instructions to authors

- Subscriptions

- About the journal

- Editorial Board

- Email alerts

- Advertising

Radiologic Technology is published by the American Society of Radiologic Technologists.

Copyright © 2024 by the American Society of Radiologic Technologists

- Print ISSN: 0033-8397

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Healthcare (Basel)

- PMC10779280

Teaching Strategies for Developing Clinical Reasoning Skills in Nursing Students: A Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials

Associated data.

Data are contained within the article.

Background: Clinical reasoning (CR) is a holistic and recursive cognitive process. It allows nursing students to accurately perceive patients’ situations and choose the best course of action among the available alternatives. This study aimed to identify the randomised controlled trials studies in the literature that concern clinical reasoning in the context of nursing students. Methods: A comprehensive search of PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and the Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials (CENTRAL) was performed to identify relevant studies published up to October 2023. The following inclusion criteria were examined: (a) clinical reasoning, clinical judgment, and critical thinking in nursing students as a primary study aim; (b) articles published for the last eleven years; (c) research conducted between January 2012 and September 2023; (d) articles published only in English and Spanish; and (e) Randomised Clinical Trials. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tool was utilised to appraise all included studies. Results: Fifteen papers were analysed. Based on the teaching strategies used in the articles, two groups have been identified: simulation methods and learning programs. The studies focus on comparing different teaching methodologies. Conclusions: This systematic review has detected different approaches to help nursing students improve their reasoning and decision-making skills. The use of mobile apps, digital simulations, and learning games has a positive impact on the clinical reasoning abilities of nursing students and their motivation. Incorporating new technologies into problem-solving-based learning and decision-making can also enhance nursing students’ reasoning skills. Nursing schools should evaluate their current methods and consider integrating or modifying new technologies and methodologies that can help enhance students’ learning and improve their clinical reasoning and cognitive skills.

1. Introduction

Clinical reasoning (CR) is a holistic cognitive process. It allows nursing students to accurately perceive patients’ situations and choose the best course of action among the available alternatives. This process is consistent, dynamic, and flexible, and it helps nursing students gain awareness and put their learning into perspective [ 1 ]. CR is an essential competence for nurses’ professional practice. It is considered crucial that its development begin during basic training [ 2 ]. Analysing clinical data, determining priorities, developing plans, and interpreting results are primary skills in clinical reasoning during clinical nursing practise [ 3 ]. To develop these skills, nursing students must participate in caring for patients and working in teams during clinical experiences. Among clinical reasoning skills, we can identify communication skills as necessary for connecting with patients, conducting health interviews, engaging in shared decision-making, eliciting patients’ concerns and expectations, discussing clinical cases with colleagues and supervisors, and explaining one’s reasoning to others [ 4 ].

Educating students in nursing practise to ensure high-quality learning and safe clinical practise is a constant challenge [ 5 ]. Facilitating the development of reasoning is challenging for educators due to its complexity and multifaceted nature [ 6 ], but it is necessary because clinical reasoning must be embedded throughout the nursing curriculum [ 7 ]. Such being the case, the development of clinical reasoning is encouraged, aiming to promote better performance in indispensable skills, decision-making, quality, and safety when assisting patients [ 8 ].

Nursing education is targeted at recognising clinical signs and symptoms, accurately assessing the patient, appropriately intervening, and evaluating the effectiveness of interventions. All these clinical processes require clinical reasoning, and it takes time to develop [ 9 ]. This is a significant goal of nursing education [ 10 ] in contemporary teaching and learning approaches [ 6 ].

Strategies to mitigate errors, promote knowledge acquisition, and develop clinical reasoning should be adopted in the training of health professionals. According to the literature, different methods and teaching strategies can be applied during nursing training, as well as traditional teaching through lectures. However, the literature explains that this type of methodology cannot enhance students’ clinical reasoning alone. Therefore, nursing educators are tasked with looking for other methodologies that improve students’ clinical reasoning [ 11 ], such as clinical simulation. Clinical simulation offers a secure and controlled setting to encounter and contemplate clinical scenarios, establish relationships, gather information, and exercise autonomy in decision-making and problem-solving [ 12 ]. Different teaching strategies have been developed in clinical simulation, like games or case studies. Research indicates a positive correlation between the use of simulation to improve learning outcomes and how it positively influences the development of students’ clinical reasoning skills [ 13 ].

The students of the 21st century utilise information and communication technologies. With their technological skills, organisations can enhance their productivity and achieve their goals more efficiently. Serious games are simulations that use technology to provide nursing students with a safe and realistic environment to practise clinical reasoning and decision-making skills [ 14 ] and can foster the development of clinical reasoning through an engaging and motivating experience [ 15 ].

New graduate nurses must possess the reasoning skills required to handle complex patient situations. Aware that there are different teaching methodologies, with this systematic review we intend to discover which RCTs published focus on CR in nursing students, which interventions have been developed, and their effectiveness, both at the level of knowledge and in increasing clinical reasoning skills. By identifying the different techniques used during the interventions with nursing students in recent years and their effectiveness, it will help universities decide which type of methodology to implement to improve the reasoning skills of nursing students and, therefore, obtain better healthcare results.

This study aims to identify and analyse randomised controlled trials concerning clinical reasoning in nursing students. The following questions guide this literature review:

Which randomised controlled trials have been conducted in the last eleven years regarding nursing students’ clinical reasoning? What are the purposes of the identified RCTs? Which teaching methodologies or strategies were used in the RCTs studies? What were the outcomes of the teaching strategies used in the RCTs?

2. Materials and Methods

This review follows the PRISMA 2020 model statement for systematic reviews. That comprises three documents: the 27-item checklist, the PRISMA 2020 abstract checklist, and the revised flow diagram [ 16 ].

2.1. Search Strategy

A systematic literature review was conducted on PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and the Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials (CENTRAL) up to 15th October 2023.

The PICOS methodology guided the bibliographic search [ 17 ]: “P” being the population (nursing students), “I” the intervention (clinical reasoning), “C” comparison (traditional teaching), “O” outcome (dimension, context, and attributes of clinical reasoning in the students’ competences and the results of the teaching method on nursing students), and “S” study type (RCTs).

The search strategy used in each database was the following: (“nursing students” OR “nursing students” OR “pupil nurses” OR “undergraduate nursing”) AND (“clinical reasoning” OR “critical thinking” OR “clinical judgment”). The filters applied were full text, randomised controlled trial, English, Spanish, and from 1 January 2012 to 15 October 2023. The search strategy was performed using the same process for each database. APP performed the search, and AZ supervised the process.

During the search, the terms clinical reasoning, critical thinking, and clinical judgement were used interchangeably since clinical judgement is part of clinical reasoning and is defined by the decision to act. It is influenced by an individual’s previous experiences and clinical reasoning skills [ 18 ]. Critical thinking and clinical judgement involve reflective and logical thinking skills and play a vital role in the decision-making and problem-solving processes [ 19 ].

The first search was conducted between March and September 2022, and an additional search was conducted during October 2023, adding the new articles published between September 2022 and September 2023, following the same strategy. The search strategy was developed using words from article titles, abstracts, and index terms. Parallel to this process, the PRISMA protocol was used to systematise the collection of all the information presented in each selected article. This systematic review protocol was registered in the international register PROSPERO: CRD42022372240.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

The following inclusion criteria were examined: (a) clinical reasoning, clinical judgment, and critical thinking in nursing students as a primary aim; (b) articles published in the last eleven years; (c) research conducted between January 2012 and September 2023; (d) articles published only in English and Spanish; and (e) RCTs. On the other hand, the exclusion criteria were studies conducted with students from other disciplines other than nursing, not random studies or review articles.

2.3. Data Collection and Extraction

After this study selection, the following information was extracted from each article: bibliographic information, study aims, teaching methodology, sample size and characteristics, time of intervention, and conclusions.

2.4. Risk of Bias

The two reviewers, APP and AZ, worked independently to minimise bias and mistakes. The titles and abstracts of all papers were screened for inclusion. All potential articles underwent a two-stage screening process based on the inclusion criteria. All citations were screened based on title, abstract, and text. Reviewers discussed the results to resolve minor discrepancies. All uncertain citations were included for full-text review. The full text of each included citation was obtained. Each study was read thoroughly and assessed for inclusion following the inclusion and exclusion criteria explained in the methodology. The CASP tool was utilised to appraise all included studies. The CASP Randomized Controlled Trial Standard Checklist is an 11-question checklist [ 20 ], and the components assessed included the appropriateness of the objective and aims, methodology, study design, sampling method, data collection, reflexivity of the researchers, ethical considerations, data analysis, rigour of findings, and significance of this research. These items of the studies were then rated (“Yes” = with three points; “Cannot tell” = with two points; “No” = with one point). The possible rates for every article were between 0 and 39 points.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

Since this study was a comprehensive, systematic review of the existing published literature, there was no need for us to seek ethical approval.

3.1. Search Results

The initial search identified 158 articles using the above-mentioned strategy (SCOPUS ® n = 72, PUBMED ® n = 56, CENTRAL ® n = 23, and EMBASE ® n= 7), and the results are presented in Figure 1 . After retrieving the articles and excluding 111, 47 were selected for a full reading. Finally, 17 articles were selected. To comply with the methodology, the independent reviewers analysed all the selected articles one more time after the additional search, and they agreed to eliminate two of them because this study sample included nursing students as well as professional nurses. Therefore, to have a clear outcome focused on nursing students, two articles were removed, and the very final sample size was fifteen articles, following the established selection criteria ( Figure 1 ). The reasons for excluding studies from the systematic review were: nurses as targets; other design types of studies different from RCTs; focusing on other health professionals such as medical students; review studies; and being published in full text in other languages other than Spanish or English.

Flowchart of screening of clinical reasoning RCTs that underwent review.

3.2. Risk of Bias in CASP Results

All studies included in the review were screened with the CASP tool. Each study was scored out of a maximum of 39 points, showing the high quality of the randomised control trial methodology. The studies included had an average score of 33.1, ranging from 30 to 36 points. In addition, this quantitative rate of the items based on CASP, there were 13 studies that missed an item in relation to assessing/analysing outcome/s ‘blinded or not’ or not, and 11 studies that missed the item whether the benefits of the experimental intervention outweigh the harms and costs.

3.3. Data Extraction

Once the articles had undergone a full reading and the inclusion criteria were applied, data extraction was performed with a data extraction table ( Appendix A ). Their contents were summarised into six different cells: (1) CASP total points result, (2) purpose of this study, (3) teaching strategy, (4) time of intervention, (5) sample size, and (6) author and year of publication. After the review by the article’s readers, fifteen RCTs were selected. Of the fifteen, the continent with the highest number of studies was Asia, with 53.33% of the studies (n = 8) (Korea n = 4, Taiwan n = 2, and China n = 2), followed by Europe with 26.66% (n = 4) (Turkey n = 2, Paris n = 1, and Norway n = 1), and lastly South America with 20% (n = 3), all of them from Brazil.

3.4. Teaching Strategies

Different teaching strategies have been identified in the reviewed studies: simulation methods (seven articles) and learning programmes (eight articles). There are also two studies that focus on comparing different teaching methodologies.

3.4.1. Clinical Simulation

The simulation methods focused on in the studies were virtual simulation (based on mobile applications), simulation games, and high-fidelity clinical simulation. Of the total number of nursing students in the studies referring to clinical simulations, 43.85% were in their second year, while 57.1% were senior-year students. The most used method in the clinical simulation group was virtual simulation, and 57.14% of studies included only one-day teaching interventions.

Virtual simulations were used to increase knowledge about medication administration and nasotracheal suctioning in different scenarios [ 21 ], to evaluate the effect of interactive nursing skills, knowledge, and self-efficacy [ 11 ], and to detect patient deterioration in two different cases [ 22 ]. Simulation game methodology was used to improve nursing students’ cognitive and attention skills, strengthen judgment, time management, and decision-making [ 14 ].

Clinical simulation was used to develop nursing students’ clinical reasoning in evaluating wounds and their treatments [ 12 ], to evaluate and compare the perception of stressors, with the goal of determining whether simulations promote students’ self-evaluation and critical-thinking skills [ 23 ], and also to evaluate the impact of multiple simulations on students’ self-reported clinical decision-making skills and self-confidence [ 24 ].

3.4.2. Learning Programs

Different types of learning programmes have been identified in this systematic review: team-based learning, reflective training programs, person-centred educational programmes, ethical reasoning programmes, case-based learning, mapping, training problem-solving skills, and self-instructional guides. Of the total number of nursing students in the studies referring to learning programs, 57.1% were junior-year students, while 43.85% were in their senior year.