Complementary Medicine Research

Practice, methods, perspectives.

Editor: Musial, F. (Tromsø)

Editorial Board

Novel Aspects of Research and Clinical Practice in Complementary Medicine

Complementary Medicine Research is an international peer-reviewed journal. We aim to bridge the gap between conventional and complementary/alternative medicine (CAM) on a sound scientific basis, promoting their mutual integration. The journal publishes papers relevant to complementary patient-centered care, especially those with emphases on novel, creative and clinically relevant approaches. It covers the entire spectrum of original research, clinical trials, views, conceptual papers, and reviews on complementary practice and methods, as well as clinical case studies of high quality and relevance.

About this Journal

Calls for papers.

See the latest calls for papers from our extensive journal range.

CHECK OUT NOW

Journal Details

More Details

For Authors

Publish your paper with us.

Author Guidelines

Cost of Publication

Editors and Reviewers

Login to our peer review system.

Affiliations

Schweizerischen Medizinischen Gesellschaft für Phytotherapie

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Naturheilkunde

News & Highlights

Congress announcements.

Have a look at all events related to this journal.

Issues & Articles

Online-First Articles

Accepted and fully citable articles not yet assigned to an issue.

View articles

Connect with Us

Follow us on x @researchkarger.

Check out our X feed.

- Stay Up-to-Date

Get news according to your interests.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

Recommend this Journal

Suggest this journal via social media or e-mail to your colleagues.

- Online ISSN 2504-2106

- Print ISSN 2504-2092

INFORMATION

- Contact & Support

- Information & Downloads

- Rights & Permissions

- Terms & Conditions

- Catalogue & Pricing

- Policies & Information

- People & Organization

- Regional Offices

- Community Voice

SERVICES FOR

- Researchers

- Healthcare Professionals

- Patients & Supporters

- Health Sciences Industry

- Medical Societies

- Agents & Booksellers

Karger International

- S. Karger AG

- P.O Box, CH-4009 Basel (Switzerland)

- Allschwilerstrasse 10, CH-4055 Basel

- Tel: +41 61 306 11 11

- Fax: +41 61 306 12 34

- Contact: Front Office

- Experience Blog

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Journal of Integrative and Complementary Medicine Advancing Whole Health

Editor-in-Chief: Holger Cramer, PhD

Impact Factor: 2.6* *2022 Journal Citation Reports™ (Clarivate, 2023) ^ Formerly known as The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine

Citescore™: 4.2.

The leading peer-reviewed journal providing scientific research for the evaluation and integration of complementary medicine into mainstream medical practice.

- View Aims & Scope

- Indexing/Abstracting

- Editorial Board

- Featured Content

- About This Publication

- Reprints & Permissions

- News Releases

- Sample Issue

Aims & Scope

Journal of Integrative and Complementary Medicine is the leading peer-reviewed journal providing scientific research for the evaluation and integration of complementary and integrative medicine into mainstream medical practice. The Journal delivers original research that directly impacts patient care therapies, protocols, and strategies, ultimately improving the quality of healing.

Journal of Integrative and Complementary Medicine coverage includes:

- Botanical Medicine

- Acupuncture and Traditional Chinese Medicine

- Other Traditional Medicine Practices

- Mind-Body Medicine

- Nutrition and Dietary Supplements

- Integrative Health / Medicine

- Naturopathy

- Creative Arts Therapies

- Integrative Whole Systems / Whole Practices

- Massage Therapy

- Subtle Energies and Energy Medicine

- Integrative Cost Studies / Comparative Effectiveness

- Neurostimulation

- Integrative Biophysics

Journal of Integrative and Complementary Medicine is under the editorial leadership of Editor-in-Chief Holger Cramer, PhD and other leading investigators. View the entire editorial board .

Audience: Conventional medicine, nursing, psychiatric, and psychology practitioners; alternative medicine practitioners, researchers, and specialists; schools of Oriental medicine; and pharmaceutical, herbal, and other therapeutic industry professionals; among others

Indexing/Abstracting:

- PubMed/MEDLINE

- PubMed Central

- Web of Science: Science Citation Index Expanded™ (SCIE)

- Current Contents®/Clinical Medicine

- Journal Citation Reports/Science Edition

- Prous Science Integrity®

- International Pharmaceutical Abstracts

- EMBASE/Excerpta Medica

- CINAHL® database

- ProQuest databases

- CAB Abstracts

- Global Health

- Centralised Information Service for Complementary Medicine (CISCOM)

- AMED - Allied and Contemporary Medicine Database

- The MANTIS database

Society Affiliations

The Official Journal of:

Society for Integrative Oncology

An Official Journal of:

International Society for Traditional, Complementary, & Integrative Medicine Research

Column Partners with:

Special Issue: Global Public Health

More Special Issues...

Recommended Publications

Integrative and Complementary Therapies

Medical Acupuncture

Journal of Medicinal Food

- Open access

- Published: 14 January 2022

Acceptance and use of complementary and alternative medicine among medical specialists: a 15-year systematic review and data synthesis

- Phanupong Phutrakool ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0792-0275 1 &

- Krit Pongpirul ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3818-9761 1 , 2 , 3

Systematic Reviews volume 11 , Article number: 10 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

18k Accesses

24 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) has gained popularity among the general population, but its acceptance and use among medical specialists have been inconclusive. This systematic review aimed to identify relevant studies and synthesize survey data on the acceptance and use of CAM among medical specialists.

We conducted a systematic literature search in PubMed and Scopus databases for the acceptance and use of CAM among medical specialists. Each article was assessed by two screeners. Only survey studies relevant to the acceptance and use of CAM among medical specialists were reviewed. The pooled prevalence estimates were calculated using random-effects meta-analyses. This review followed both PRISMA and SWiM guidelines.

Of 5628 articles published between 2002 and 2017, 25 fulfilled the selection criteria. Ten medical specialties were included: Internal Medicine (11 studies), Pediatrics (6 studies), Obstetrics and Gynecology (6 studies), Anesthesiology (4 studies), Surgery (3 studies), Family Medicine (3 studies), Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (3 studies), Psychiatry and Neurology (2 studies), Otolaryngology (1 study), and Neurological Surgery (1 study). The overall acceptance of CAM was 52% (95%CI, 42–62%). Family Medicine reported the highest acceptance, followed by Psychiatry and Neurology, Neurological Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Pediatrics, Anesthesiology, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Internal Medicine, and Surgery. The overall use of CAM was 45% (95% CI, 37–54%). The highest use of CAM was by the Obstetrics and Gynecology, followed by Family Medicine, Psychiatry and Neurology, Pediatrics, Otolaryngology, Anesthesiology, Internal Medicine, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, and Surgery. Based on the studies, meta-regression showed no statistically significant difference across geographic regions, economic levels of the country, or sampling methods.

Acceptance and use of CAM varied across medical specialists. CAM was accepted and used the most by Family Medicine but the least by Surgery. Findings from this systematic review could be useful for strategic harmonization of CAM and conventional medicine practice.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42019125628

Graphical abstract

Peer Review reports

Medical specialist is a healthcare professional who has undertaken specialized medical studies to diagnose, treat and prevent illness, disease, injury, and other physical and mental impairments in humans, using specialized testing, diagnostic, medical, surgical, physical, and psychiatric techniques, through application of the principles and procedures of modern medicine [ 1 ]. The specialized and general medical care have dominated as ‘conventional’ medical care in several countries, including Thailand.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) is defined as medicine or treatment which is not considered as conventional (standard) medicine. The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) categorized most types of complementary medicines under two categories: (1) natural products and (2) mind-body practices [ 2 ]. Natural products include herbs, vitamins, minerals, and probiotics whereas mind-body practices include yoga, chiropractic, massage, acupuncture, yoga, meditation, and massage therapy. Types of CAM may vary across studies, but they overlap in most senses.

CAM is used by people throughout the world. A study showed that the prevalence estimate of CAM usage from 32 countries from all regions of the world to be 26.4%, ranging from 25.9 to 26.9%. For example, in 2013, the prevalence use of CAM in Australia, the USA, UK, and China were 34.7%, 21.0%, 23.6%, and 53.3%, respectively. The prevalence estimate of CAM satisfaction was as high as 71.9%, ranging from 71.0 to 72.7% [ 3 ].

Although patients are highly satisfied with CAM treatment, professional health care providers who are medical doctors do not offer CAM because it is not part of the standard conventional medical care. Although the majority of physicians who have used CAM were pleased with the results [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ] and were more likely to recommend it to patients, friends, and family [ 9 , 10 ] as a non-toxic treatment option; less than one third of the medical doctors were very comfortable in answering questions about CAM [ 9 , 11 , 12 , 13 ] so patients who do not have the option to use CAM instead of standard medical care might be lost to follow-up. Some doctors are still skeptical of CAM because of a lack of specific knowledge and qualification as well as a lack of evidence from high-quality experimental studies on the efficacy of the CAM treatments [ 4 , 12 , 14 , 15 ]. In the field of oncology, for example, the 5-year survival rate of breast cancer patients who refused standard treatment was 43.2%, compared with 81.9% of those who underwent the standard treatment [ 16 ]. When CAM was used, the 5-year survival rate was significantly worse. The 5-year survival rate of cancer patients who used CAM versus those who used standard treatment were stratified by cancer type were as follows: [ 17 ] for breast cancer 58.1% vs 86.6% ( p value < 0.01; HR = 5.68), lung cancer 19.9% vs 41.3% ( p value < 0.01; HR = 2.17), and colorectal cancer 32.7% vs 79.4% ( p value < 0.01; HR = 4.57). On the contrary, the 28-day mortality of patient with sepsis and acute gastrointestinal injury who received CAM bundle with conventional therapy was statistically significantly lower than those who received only conventional therapy (21.2% vs 32.5%, p value = 0.038) [ 18 ]. These differential clinical benefits of CAM across various medical specialties could be partly explained by how CAM is perceived by the medical specialists in conventional medicine dominated contexts.

Several studies have surveyed the acceptance and use of CAM from laypersons [ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ] to healthcare professional perspectives [ 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Nonetheless, these surveys did not cover all medical specialists so the findings could not reflect the comparative acceptance and use of CAM across medical specialties. Also, previous studies could not determine whether the acceptance and use of CAM by medical specialists differ across contexts (i.e., regions and economic levels of the country) and study designs (i.e., survey and sampling methods). A better understanding of how various medical specialists perceive of CAM is strategically essential for harmonizing CAM into conventional medicine practices. This systematic review aimed to identify relevant studies and synthesize survey data on the acceptance and use of CAM among medical specialists.

Materials and methods

Protocol and registration.

This systematic review has been registered in PROSPERO (CRD42019125628) and the protocol can be accessed at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42019125628 .

Literature search

This systematic review was conducted and reported according to the PRISMA statement as well as the Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM) guidelines [ 30 ]. A systematic literature search was performed by two independent authors (PP and KP) using PubMed and Scopus databases. The search was limited to observational studies of human subjects and the English language. The medical specialist’s perspective related to CAM studies were focused. The search strategy was based on various combinations of words and focused on two main concepts: acceptance and usage of CAM. The last search was conducted on March 1, 2019.

For the PubMed database, the following combinations were applied: ("Traditional Medicine"[All Fields] OR "Alternative Medicine"[All Fields] OR "Complementary Medicine"[All Fields] OR "Acupuncture Therapy"[All Fields] OR "Holistic Health"[All Fields] OR "Homeopathy"[All Fields] OR "Spiritual Therapies"[All Fields] OR "Faith Healing"[All Fields] OR "Yoga"[All Fields] OR "Witchcraft"[All Fields] OR "Shamanism"[All Fields] OR "Meditation"[All Fields] OR "Aromatherapy"[All Fields] OR "Medical Herbalism"[All Fields] OR "Mind-Body Therapies"[All Fields] OR "Laughter Therapy"[All Fields] OR "Hypnosis"[All Fields] OR "Tai Ji"[All Fields] OR "Tai Chi"[All Fields] OR "Relaxation Therapy"[All Fields] OR "Mental Healing"[All Fields] OR "Meditation"[All Fields]) AND ("Health care provider"[All Fields] OR "Health care providers"[All Fields] OR "Health personnel"[All Fields]) AND ("2002/01/01"[PDAT]: "2017/12/31"[PDAT]) AND "humans"[MeSH Terms].

For the Scopus database, the following combinations were applied: (ALL("Traditional Medicine") OR ALL("Alternative Medicine") OR ALL("Complementary Medicine") OR ALL("Acupuncture Therapy") OR ALL("Holistic Health") OR ALL("Homeopathy") OR ALL("Spiritual Therapies") OR ALL("Faith Healing") OR ALL("Yoga") OR ALL("Witchcraft") OR ALL("Shamanism") OR ALL("Meditation") OR ALL("Aromatherapy") OR ALL("Medical Herbalism") OR ALL("Mind-Body Therapies") OR ALL("Laughter Therapy") OR ALL("Hypnosis") OR ALL("Tai Ji") OR ALL("Tai Chi") OR ALL("Relaxation Therapy") OR ALL("Mental Healing") OR ALL("Meditation")) AND (ALL("Health care provider") OR ALL("Health care providers") OR ALL("Health personnel")) AND PUBYEAR AFT 2001 AND PUBYEAR BEF 2018 AND DOCTYPE(ar) AND INDEXTERMS("Humans")

Selection of studies

The titles and abstracts of the primary studies identified in the electronic search were screened by the same two authors. Duplicated studies were excluded. For the meta-analysis, the following inclusion criteria were set: (1) medical specialist’s perspective, (2) prevalence of acceptance or usage of CAM, (3) observational study design, and (4) published between 2002 to 2017. The following exclusion criterion was set: (1) Not relevant to the practice. We contacted the authors for studies that had incomplete and unclear information. If the authors did not respond within 14 days, we proceeded to analyze the data we had. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion and the final determination was made by the first author (PP).

Data extraction and management

Two authors worked independently to review and extract the following variables: (1) general information, including the name of the studies, authors, and publication year, (2) characteristics of the studies, including the design of the studies, sampling method, country, and setting, (3) characteristics of the participants, including sample size, response, and type of specialty, and (4) outcomes, including the prevalence of acceptance, and usage of CAM. All relevant text, tables, and figures were examined for data extraction. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved by the first author (PP).

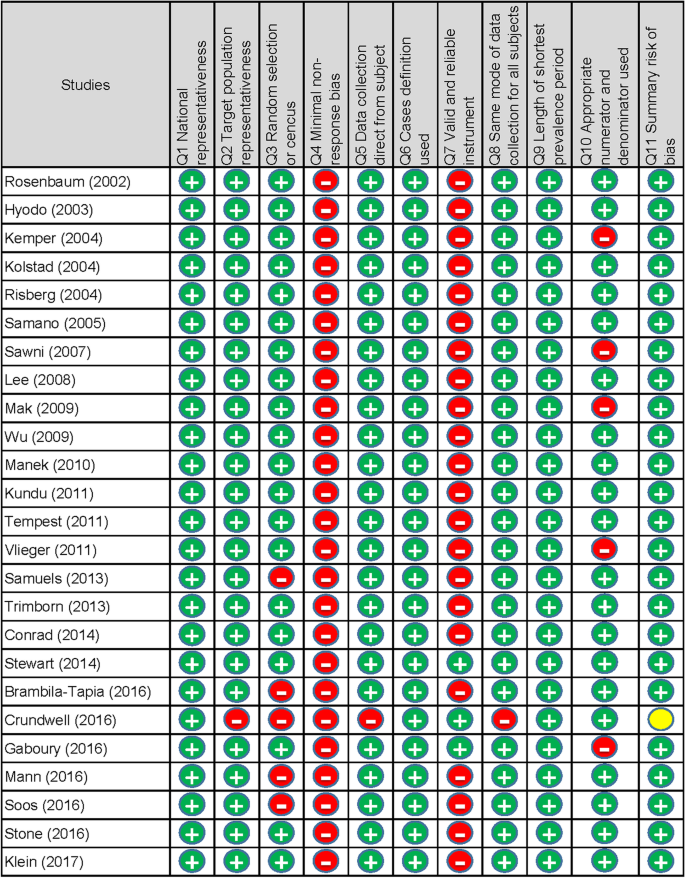

Study quality/risk of bias

We used the tool developed by Hoy et al. [ 31 ] to evaluate the study quality/risk of bias of the studies included in the analysis. The tool has 11 items: (1) national representativeness, (2) target population representativeness, (3) random selection or census undertaken, (4) minimal non-response bias, (5) data collection direct from the subject, (6) definition of the case used, (7) valid and reliable instrument, (8) the same mode of data collection for all subjects, (9) length of shortest prevalence period, (10) appropriate numerator and denominator used, and (11) summary assessment. Items 1 to 4 assessed the external validity, items 5 to 10 assessed the internal validity, and items 11 evaluated the overall study quality/risk of bias. Each item was assigned a score of 1 (high quality/low risk) or 0 (low quality/high risk), and the scores were summed to generate an overall quality score that ranged from 0 to 10. According to the overall score, we classified the studies as having a high quality/low risk of bias (>6), moderate quality/risk of bias (4 to 6), and low quality/high risk of bias (<4). Two authors (PP and KP) independently assessed the study quality/risk of bias and any disagreement was resolved by discussion and consensus.

Conflict of interest

We assessed the conflict of interest of the authors’ declarations in the studies.

Statistical analysis

Unadjusted prevalence estimates of acceptance and usage of CAM were calculated based on the information of crude numerators and denominators provided by the studies and medical specialty [ 32 ]. Pooled prevalence was estimated from the prevalence as reported by the eligible studies. For each study and specialty, forest plots were generated displaying the prevalence with a 95% CI. The overall random-effects pooled estimate with its 95% CI were reported. To examine the magnitude of the variation between the studies, we quantified the heterogeneity by using I 2 and its 95% CI.

To assess the level of heterogeneity as defined in Chapter 9 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, the following I 2 cut-offs for 0 to 40% represented that the heterogeneity may not be important, 30 to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity, 50 to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity, and 75 to 100% represented that there was a considerable heterogeneity. For the X 2 test, statistical heterogeneity of the included trials was assessed with a p value of less than 0.05 (statistically significant). The random-effects meta-analysis by DerSimonian and Laird method was used, and statistical heterogeneity was encountered. The meta-analysis was performed using Stata/MP software version 15 (StataCorp 2017, College Station, TX).

Additional analysis

Meta-regression was performed to investigate the pooled prevalence differences between various regions (African region, region of the Americas, Eastern Mediterranean region, European region, Southeast Asia region, Western Pacific region, and mixed region) [ 33 ], economic levels of the country (low-income, lower-middle-income, upper-middle-income, high-income, and mixed-income) [ 34 ], and the sampling method (random and convenience sampling) for each study.

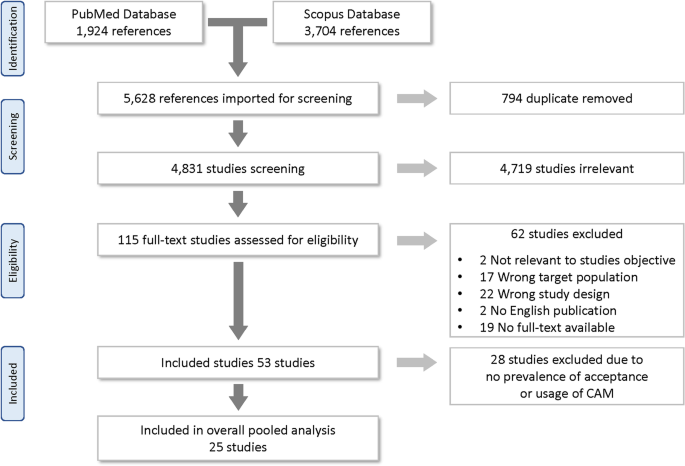

Selection of the studies

The literature search yielded 5628 articles. After 794 duplicates were removed, 4831 titles and abstracts were screened, and 4719 irrelevant articles were removed. Of 115 articles selected for full-text screening, 62 were excluded for the following reasons: two were not relevant to this study’s objective, 17 had the wrong target population, 22 did not have the study design required for this review, two study was not published in English, 19 did not have full-text available, and 28 did not provide the prevalence. Finally, a total of 25 articles, published between 2002 and 2017, fulfilled the selection criteria and were included in this meta-analysis (Fig. 1 ).

Characteristics of the studies

All included studies were cross-sectional. The publication years ranged from 2002 to 2017 in various countries: European region ( n = 11, 44%), region of the Americas ( n = 10, 40%), Western Pacific region ( n = 3, 12%), and mixed region ( n = 1, 4%). Twenty-three studies (88%) were from high-income countries, 2 (8%) from upper-middle income countries, and 1 (4%) was from mixed-economic level country. The included studies indicated which type of collection method was used: online survey ( n = 8, 32%), postal survey ( n = 8, 32%), online and postal survey ( n = 3, 12%), online and phone survey ( n = 1, 4%), and the collection method was not reported ( n = 5, 20%). The studies included a total of 7320 participants who were categorized as medical specialty ( n = 5445, 74%), and non-medical specialty ( n = 1875, 26%) (Table 1 ).

The included studies had the following medical specialties: internal medicine (11 studies, n = 2253), pediatrics (6 studies, n = 2,130), obstetrics and gynecology (6 studies, n = 707), anesthesiology (4 studies, n = 342), surgery (3 studies, n = 564), family medicine (3 studies, n = 296), physical medicine and rehabilitation (3 studies, n = 104), psychiatry and neurology (2 studies, n = 22), otolaryngology (1 study, n = 49), and neurological surgery (1 study, n = 24) (Table 2 )

Based on the specialty

Prevalence of cam acceptance.

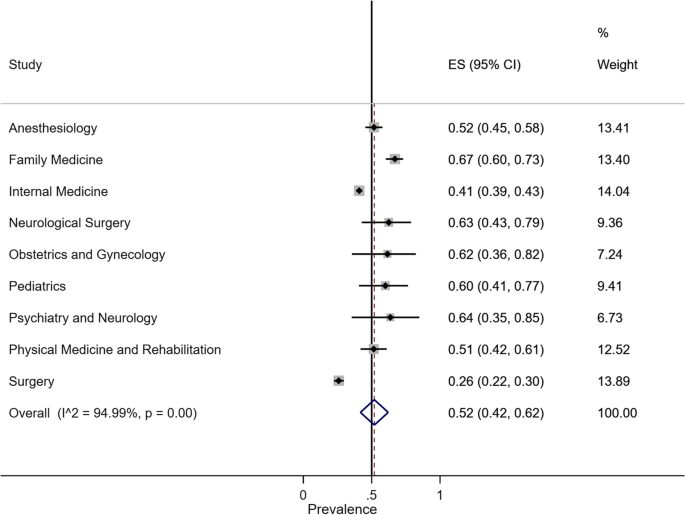

The overall random-effect pooled prevalence of CAM acceptance in medical specialty was 52% (95% CI, 42–62%). The prevalence of CAM acceptance in Family Medicine was 67% (95% CI, 60–73%), Psychiatry and Neurology was 64% (95% CI, 35–85%), Neurological Surgery was 63% (95% CI, 43–79%), Obstetrics and Gynecology was 62% (95% CI, 36–82%), Pediatrics was 60% (95% CI, 41–77%), Anesthesiology was 52% (95% CI, 45–58%), Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation was 51% (95% CI, 42–61%), Internal Medicine was 41% (95% CI, 39–43%), and Surgery was 26% (95% CI, 22–30%). The overall heterogeneity was significant ( I 2 = 94.99%, p value < 0.001) (Fig. 2 ).

Forest plot of CAM acceptance by specialty

Prevalence of CAM usage

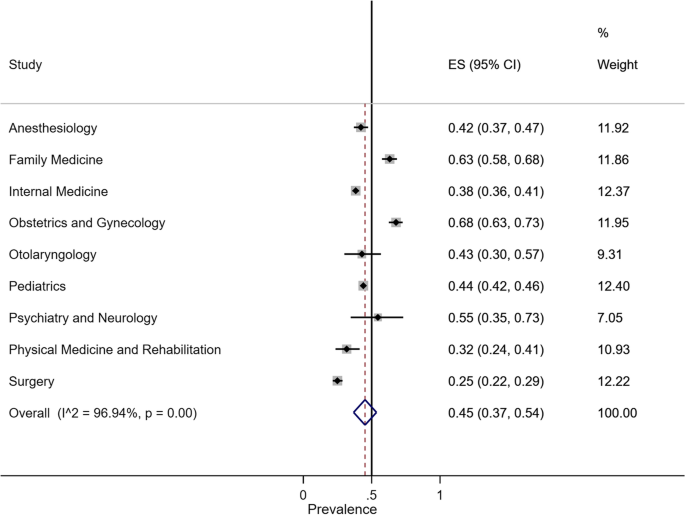

The overall random-effect pooled prevalence of CAM usage in medical specialty was 45% (95% CI, 37–54%). The prevalence of CAM usage in Obstetrics and Gynecology was 68% (95% CI, 63–73%), Family Medicine was 63% (95% CI, 58–68%), Psychiatry and Neurology was 55% (95% CI, 35–73%), Pediatrics was 44% (95% CI, 42–46%), Otolaryngology was 43% (95% CI, 30–57%), Anesthesiology was 42% (95% CI, 37–47%), Internal Medicine was 38% (95% CI, 36–41%), Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation was 32% (95% CI, 24–41%), and Surgery was 25% (95% CI, 22–29%). The overall heterogeneity was significant ( I 2 = 94.90%, p value < 0.001) (Fig. 3 ).

Forest plot of CAM usage by specialty

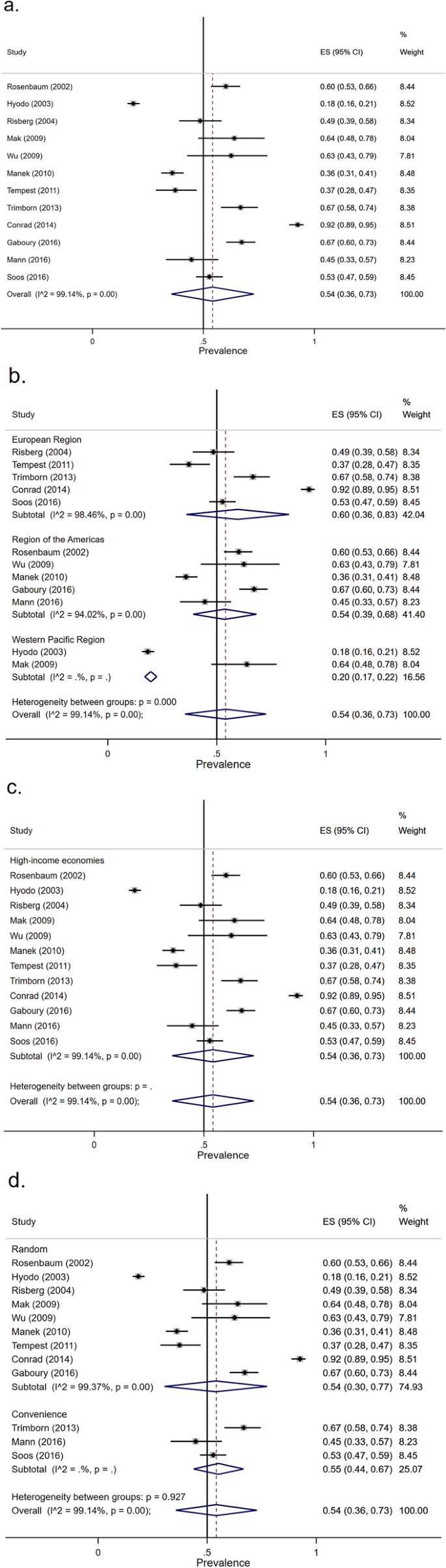

Based on the studies

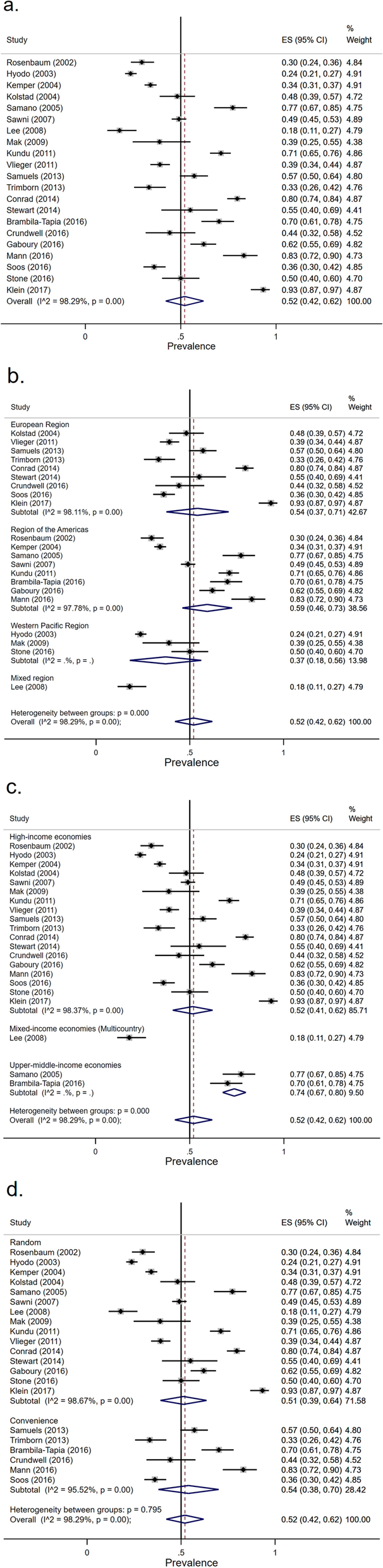

The overall random-effect pooled prevalence of CAM acceptance was 54% (95% CI, 36–73%) (Fig. 4 a). Twelve studies provided CAM acceptance: five studies in the European region, five studies in the region of the Americas, and two studies in the Western Pacific region. The pooled prevalence of the European region, region of the Americas, and Western Pacific region that accepted CAM were 60% (95% CI, 36–83%), 54% (95% CI, 39–68%), and 20% (95% CI, 17–22%), respectively (Fig. 4 b). All 12 studies were done in high-income economic countries (Fig. 4 c). Based on the sampling method, the pooled prevalence of random sampling method, and non-random sampling method were 54% (95% CI, 30–77%), and 55% (95% CI, 44–67%), respectively (Fig. 4 d). The overall heterogeneity was significant ( I 2 = 99.14%, p value < 0.001) as was the between-group heterogeneity ( p value < 0.001). Meta-regression showed that there were no significant differences in the pooled prevalence of CAM acceptance by region, economic levels of the country, and the sampling method (Table 3 ).

Forest plot of CAM acceptance

The overall random-effect pooled prevalence of CAM usage was 52% (95% CI, 42–62%) (Fig. 5 a). Twenty-one studies provided CAM usage information: nine studies in the European region, eight studies in the region of the Americas, three studies in the Western Pacific region, and one study in the mixed region. The pooled prevalence of European region, region of the Americas, Western Pacific region, and mixed region that used CAM were 54% (95% CI, 37–71%), 59% (95% CI, 46–73%), 37% (95% CI, 18–56%), and 18% (95% CI, 11–27%), respectively (Fig 5 b). All 18 studies were conducted in high-income economic countries, two studies were conducted in upper-middle-income economic countries, and one study was conducted in a mixed-income economic country. The pooled prevalence of high-income economic countries, upper-middle-income economic, and mixed-income economic countries that used CAM was 52% (95% CI, 41–62%), 74% (95% CI, 67–80%), and 18% (95% CI, 11–27%), respectively (Fig. 5 c). Based on the sampling method, the pooled prevalence of the random sampling method, and non-random sampling method were 51% (95% CI, 39–64%), and 54% (95% CI, 38–70%), respectively (Fig. 5 d). The overall heterogeneity was significant ( I 2 = 98.29%, p value < 0.001) as was between-group heterogeneity ( p value < 0.001). Meta-regression showed that there were no significant differences in the pooled prevalence of CAM usage by region, economic levels of the country, and the sampling method (Table 3 ).

Forest plot of CAM usage

Assessment of study quality/risk of bias/conflict of interest

A total of 24 (96%) studies were categorized as high quality/low risk of bias, whereas one (4%) was categorized as moderate quality/moderate risk of bias. No study met the criteria of low quality/high risk of bias (Fig 6 ). Only five studies (20%) declared that there were conflicts of interest.

Study quality/risk of bias of the included studies

This study is the first of its kind to compare the acceptance and use of CAM across various medical specialties in different contexts. As nearly three-quarters of the specialties accepted CAM more than 50% whereas nearly a third were using CAM more than 50%.

The synthesis of all prevalence estimates of acceptance and usage was 52% and 45%, respectively. The highest prevalence of acceptance was in Family Medicine, followed by Psychiatry and Neurology, Neurological Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Pediatrics, Anesthesiology, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Internal Medicine, and Surgery. The highest prevalence of usage was in Obstetrics and Gynecology, followed by Family Medicine, Psychiatry and Neurology, Pediatrics, Otolaryngology, Anesthesiology, Internal Medicine, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, and Surgery. These findings were useful in terms of improving care plan, decision-making processes, and communication in terms of CAM between the doctors and the patients.

All of the medical specialties mentioned above had a higher prevalence of acceptance than the prevalence of CAM use, except for Obstetrics and Gynecology because the gynecologic oncologists have used CAM to treat a large number of breast cancer patients [ 14 ]. There was a small difference in the prevalence (<5%) between the acceptance and the usage in Family Medicine (4%), Obstetrics and Gynecology (4%), Internal Medicine (3%), and Surgery (1%).

A highest difference of prevalence of CAM acceptance and usage was in the field of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (19%). This difference may be due to the reduction in the use of acupuncture in the academic hospitals [ 7 ] as well as personal use. Nearly two thirds of the rehabilitation physicians advised against the use of CAM as a therapeutic option [ 41 ]. The lowest prevalence of acceptance and usage of CAM was observed in Surgery. This relatively low prevalence compared to other medical specialties may be due to the belief that CAM products were ineffective. Many surgeons lacked information regarding CAM usage.

The acceptance of CAM was neutral in European region and region of the Americas. The World Health Organization reported that the prevalence of CAM usage in the European region, region of the Americas, and Western Pacific region in 2018 was 89%, 80%, and 95%, respectively [ 33 ], while this review found that the corresponding prevalence was 54%, 59%, and 37%, respectively. The lower prevalence may be from the dominating studies that were conducted before 2010 whereas CAM has used more often after 2010.

The variation of prevalence of CAM used was investigated in relation to the economic level of the countries. There was a higher prevalence of CAM use in the upper-middle-income economies than the high-income economies which may be due to cultural, historical influences, and implementation of CAM in the national health system as seen in Brazil [ 39 ] and Mexico [ 49 ].

Our study has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. Only two databases—PubMed and Scopus—were included so this review might have missed some relevant studies that were indexed elsewhere. Nonetheless, both databases were considered efficiently sufficient and most relevant to our research question within a specific domain [ 53 ]. While Web of Science and Scopus share several common features, Scopus is a relatively smaller database but covers more modern studies than Web of Science. The included studies did not cover some medical specialties that might have different acceptance and usage of CAM. Therefore, the prevalence of acceptance and usage of CAM in these populations need additional surveys. The prevalence of acceptance in some specialties like Neurological Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Otolaryngology, Pediatrics, and Psychiatry and Neurology was reported by a single study, thus limiting the generality of such findings. High heterogeneity of acceptance and usage of CAM between medical specialty referred to the variation in professional characteristic and practice, measurement methods, and study questionnaire. Most of the studies were from high-income economic countries. There were no studies from low-middle and low-income economic countries which is of concern. We found that no studies compared the relevant demographic characteristics between the responders and non-responders that would increase non-response bias when estimating the prevalence of CAM use. Although most of the studies demonstrated low risk of bias, over 88% of the studies did not use a validated instrument. Finally, the conflict of interest was not declared in more than 80% of the studies which may result in unintentional bias in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data. This can consequently lead to claims that the CAM used was beneficial because the researcher and/or entity may have a financial or management interest in the CAM used.

Conclusions

Acceptance and use of CAM varied across medical specialties. Based on available survey data, CAM was accepted and used the most by Family Medicine but the least by Surgery. Findings from this systematic review could be useful for strategic harmonization of CAM and conventional medicine practice.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

WHO European health information at your fingertips. 2020; Available from: https://gateway.euro.who.int/en/indicators/hlthres_242-specialist-medical-practitioners-total/ .

Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What’s In a Name? 2020; Available from: https://nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative-health .

Peltzer K, Pengpid S. Prevalence and determinants of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine provider use among adults from 32 countries. Chin J Integr Med. 2018;24(8):584–90.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Asadi-Pooya AA, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine in epilepsy: a global survey of physicians' opinions. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;117:107835.

Kolstad A, et al. Use of complementary and alternative therapies: a national multicentre study of oncology health professionals in Norway. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12(5):312–8.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Manek NJ, et al. What rheumatologists in the United States think of complementary and alternative medicine: results of a national survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010;10:5.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mann B, Burch E, Shakeshaft C. Attitudes toward acupuncture among pain fellowship directors. Pain Med. 2016;17(3):494–500.

PubMed Google Scholar

Trimborn A, et al. Attitude of employees of a university clinic to complementary and alternative medicine in oncology. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(10):2641–5.

Babbar S, Williams KB, Maulik D. Complementary and alternative medicine use in modern obstetrics: a survey of the central Association of Obstetricians & gynecologists members. J Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2017;22(3):429–35.

Article Google Scholar

Crundwell G, Baguley DM. Attitudes towards and personal use of complementary and alternative medicine amongst clinicians working in audiovestibular disciplines. J Laryngol Otol. 2016;130(8):730–3.

Kim S, et al. Using a survey to characterize rehabilitation Professionals' perceptions and use of complementary, integrative, and alternative medicine. J Altern Complement Med. 2020;26(8):663–5.

Land MH, Wang J. Complementary and alternative medicine use among allergy practices: results of a Nationwide survey of allergists. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(1):95–98 e3.

Stub T, et al. Complementary and conventional providers in cancer care: experience of communication with patients and steps to improve communication with other providers. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):301.

Klein E, et al. Gynecologic oncologists' attitudes and practices relating to integrative medicine: results of a nationwide AGO survey. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;296(2):295–301.

Lee RT, et al. An international pilot study of oncology physicians' opinions and practices on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Integr Cancer Ther. 2008;7(2):70–5.

Joseph K, et al. Outcome analysis of breast cancer patients who declined evidence-based treatment. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:118.

Johnson SB, et al. Use of alternative medicine for cancer and its impact on survival. JNCI: J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(1):121–4.

Xing X, et al. Traditional Chinese medicine bundle therapy for septic acute gastrointestinal injury: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2019;47:102194.

Lanski SL, et al. Herbal therapy use in a pediatric emergency department population: expect the unexpected. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5 Pt 1):981–5.

Callahan LF, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among patients with arthritis. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6(2):A44.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Chase DM, et al. Appropriate use of complementary and alternative medicine approaches in gynecologic cancers. Curr Treat Options in Oncol. 2014;15(1):14–26.

Bauml JM, et al. Do attitudes and beliefs regarding complementary and alternative medicine impact its use among patients with cancer? A cross-sectional survey. Cancer. 2015;121(14):2431–8.

Godin G, et al. Intention to encourage complementary and alternative medicine among general practitioners and medical students. Behav Med. 2007;33(2):67–77.

Chen L, et al. A survey of selected physician views on acupuncture in pain management. Pain Med. 2010;11(4):530–4.

Chang KH, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in oncology: a questionnaire survey of patients and health care professionals. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:196.

Gardiner P, et al. Family medicine residency program directors attitudes and knowledge of family medicine CAM competencies. Explore (NY). 2013;9(5):299–307.

Jakovljevic MB, et al. Cross-sectional survey on complementary and alternative medicine awareness among health care professionals and students using CHBQ questionnaire in a Balkan country. Chin J Integr Med. 2013;19(9):650–5.

Loh KP, et al. Medical students' knowledge, perceptions, and interest in complementary and alternative medicine. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19(4):360–6.

Munstedt K, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in obstetrics and gynaecology: a survey of office-based obstetricians and gynaecologists regarding attitudes towards CAM, its provision and cooperation with other CAM providers in the state of Hesse, Germany. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;290(6):1133–9.

Campbell M, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ. 2020;368:l6890.

Hoy D, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(9):934–9.

American Board of Medical Specialty. ABMS guide to medical specialties; 2019. July 9, 2019]; Available from: https://www.abms.org/member-boards/specialty-subspecialty-certificates/

Google Scholar

World Health Organization. WHO global report on traditional and complementary medicine 2019; 2019. July 23, 2019]; Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/312342/9789241515436-eng.pdf

World Bank. World Bank country and lending groups; 2019. June 29, 2019]; Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

Rosenbaum ME, et al. Academic physicians and complementary and alternative medicine: an institutional survey. Am J Med Qual. 2002;17(1):3–9.

Hyodo I, et al. Perceptions and attitudes of clinical oncologists on complementary and alternative medicine: a nationwide survey in Japan. Cancer. 2003;97(11):2861–8.

Kemper KJ, O'Connor KG. Pediatricians' recommendations for complementary and alternative medical (CAM) therapies. Ambul Pediatr. 2004;4(6):482–7.

Risberg T, et al. Knowledge of and attitudes toward complementary and alternative therapies; a national multicentre study of oncology professionals in Norway. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40(4):529–35.

Samano ES, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by Brazilian oncologists. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2005;14(2):143–8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Sawni A, Thomas R. Pediatricians' attitudes, experience and referral patterns regarding complementary/alternative medicine: a national survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007;7:18.

Mak JC, et al. Perceptions and attitudes of rehabilitation medicine physicians on complementary and alternative medicine in Australia. Intern Med J. 2009;39(3):164–9.

Wu C, et al. A survey of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) awareness among neurosurgeons in Washington state. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(5):551–5.

Kundu A, et al. Attitudes, patterns of recommendation, and communication of pediatric providers about complementary and alternative medicine in a large metropolitan children's hospital. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2011;50(2):153–8.

Tempest H, et al. Acupuncture in urological practice--a survey of urologists in England. Complement Ther Med. 2011;19(1):27–31.

Vlieger AM, van Vliet, Jong MC. Attitudes toward complementary and alternative medicine: a national survey among paediatricians in the Netherlands. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170(5):619–24.

Samuels N, et al. Use of and attitudes toward complementary and alternative medicine among obstetricians in Israel. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;121(2):132–6.

Conrad AC, et al. Attitudes of members of the German Society for Palliative Medicine toward complementary and alternative medicine for cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140(7):1229–37.

Stewart D, et al. Healthcare professional views and experiences of complementary and alternative therapies in obstetric practice in north East Scotland: a prospective questionnaire survey. Bjog. 2014;121(8):1015–9.

Brambila-Tapia AJ, et al. Attitudes, knowledge, use, and recommendation of complementary and alternative medicine by health professionals in Western Mexico. Explore (NY). 2016;12(3):180–7.

Gaboury I, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine: do physicians believe they can meet the requirements of the college des medecins du Quebec? Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(12):e772–5.

Soos SA, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine: attitudes, knowledge and use among surgeons and anaesthesiologists in Hungary. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16(1):443.

Stone AB, et al. Are anesthesia providers ready for hypnosis? Anesthesia Providers' attitudes toward hypnotherapy. Am J Clin Hypn. 2016;58(4):411–8.

Albahri AS, et al. IoT-based telemedicine for disease prevention and health promotion: state-of-the-art. J Netw Comput Appl. 2020.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Kulthanit Wanaratna and Dr. Monthaka Teerachaisakul of the Department of Thai Traditional and Alternative Medicine, Ministry of Public Health for their administrative supports.

This study received financial support from the Ratchadapiseksompotch Fund, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University (Grant Number RA62/059), and Department of Thai Traditional and Alternative Medicine, Ministry of Public Health. The sponsors have no involvement in the systematic search, abstract screening, data extraction, or manuscript preparation. Phutrakool P received the 90th anniversary of Chulalongkorn University Fund (Ratchadaphiseksomphot Endowment Fund).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Global Health and Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, 1873 Rama IV Road, Patumwan, Bangkok, 10330, Thailand

Phanupong Phutrakool & Krit Pongpirul

Department of International Health and Department of Health, Behavior and Society, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA

Krit Pongpirul

Bumrungrad International Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Phutrakool P conceptualized and designed the study, collected the data, analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the article, and finalized the manuscript for submission. Pongpirul K conceptualized and designed the study, collected the data, analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the article, and finalized the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Krit Pongpirul .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supported by Ratchadapiseksompotch Fund, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University (Grant Number RA62/059), and Department of Thai Traditional and Alternative Medicine, Ministry of Public Health. The sponsors have no involvement in the systematic search, abstract screening, data extraction, or manuscript preparation. PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: Uploaded

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

PRISMA Checklist.

Additional file 2.

The citation for the Synthesis Without Meta-analysis explanation and elaboration article is: Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, Katikireddi SV, Brennan SE, Ellis S, Hartmann-Boyce J, Ryan R, Shepperd S, Thomas J, Welch V, Thomson H. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline BMJ 2020;368:l6890 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6890 .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Phutrakool, P., Pongpirul, K. Acceptance and use of complementary and alternative medicine among medical specialists: a 15-year systematic review and data synthesis. Syst Rev 11 , 10 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01882-4

Download citation

Received : 19 January 2021

Accepted : 27 December 2021

Published : 14 January 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01882-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Complementary and alternative medicine

- Medical specialist

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 20 March 2019

A critical integrative review of complementary medicine education research: key issues and empirical gaps

- Alastair C. Gray ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4520-4560 1 , 2 , 3 , 6 ,

- Amie Steel 4 &

- Jon Adams 5

BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine volume 19 , Article number: 73 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

9049 Accesses

22 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

Complementary Medicine (CM) continues to thrive across many countries. Closely related to the continuing popularity of CM has been an increased number of enrolments at CM education institutions across the public and private tertiary sectors. Despite the popularity of CM across the globe and growth in CM education/education providers, to date, there has been no critical review of peer-reviewed research examining CM education undertaken. In direct response to this important gap, this paper reports the first critical review of contemporary literature examining CM education research.

A review was undertaken of research to identify empirical research papers reporting on CM education published between 2005 and 17. The search was conducted in May 2017 and included the search of PubMed and EBSCO (CINAHL, MEDLINE, AMED) for search terms embracing CM and education. Identified studies were evaluated using the STROBE, SRQP and MMAT appraisal tools.

From 9496 identified papers, 18 met the review inclusion criteria (English language, original empirical research data, reporting on the prevalence or nature of the education of CM practitioners), and highlighted four broad issues: CM education provision; the development of educational competencies to develop clinical skills and standards; the application of new educational theory, methods and technology in CM; and future challenges facing CM education. This critical integrative review highlights two key issues of interest and significance for CM educational institutions, CM regulators and researchers, and points to number of significant gaps in this area of research. There is very sporadic coverage of research in CM education. The clear absence of the robust and mature research regarding educational technology and e-learning taking place in medical and or allied health education research is notably absent within CM educational research.

Despite the high levels of CM use in the community, and the thriving nature of CM educational institutions globally, the current evidence evaluating the procedures, effectiveness and outcomes of CM education remains limited on a number of fronts. There is an urgent need to establish a strategic research agenda around this important aspect of health care education with the overarching goal to ensure a well-educated and effective health care workforce.

Peer Review reports

The practice, uptake and economics of Complementary Medicine (CM) - a range of therapies, products and approaches to health and illness not traditionally associated with the medical profession or medical curriculum [ 1 ] - continues to thrive in many countries [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ] and concurrently the enrolments at CM education institutions have steadily increased [ 8 , 9 ]. CM education institutions providing training and qualifications including naturopathy, nutritional medicine, homeopathy, acupuncture, massage therapy and herbal medicine are located across both the public and private tertiary sector in many regions, Australia [ 10 ], USA [ 11 ], UK [ 12 ], Asia [ 13 ]. The professionalization of the CM education sector appears to be evolving with continuing professional education, education standards, levels of foundational medical science and higher levels of qualifications emerging in recent years [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ].

These education institutions face innumerable challenges. These include preparing CM graduates to function as health professionals in a contemporary health system when they apply predominantly traditional principles and concepts [ 19 , 20 ]. Another challenge is training students in inter-professional care when the focus during training is often on mastering a traditional technique or philosophy [ 21 ]. Further challenges involve providing education about evidence-based healthcare when the focus during training is often on learning and applying traditional evidence - defined here as evidence with a long and coherent history of use, well documented in monographs such as materia medica and other texts, mainly inductive in nature, and passed on orally over many generations [ 22 ]. This is pertinent in a field that has 700 Cochrane systematic reviews yet one where traditional evidence and knowledge is also highly regarded. Further, providing education on patient-centred care [ 23 ], supporting non-traditional students [ 24 , 25 ] and also gaining funding for and providing education related to perceived non-credible CM modalities in conventional tertiary education settings are challenges [ 26 ]. In addition, challenges continue to arise for education leaders both within and beyond CM regarding technological advances and the consequences for students, educators and institutions [ 27 , 28 , 29 ]. New developments in healthcare such as e-health/tele-health [ 30 ] and a growth in interest in the pedagogy and andragogy of online learning [ 31 , 32 ] in general, present challenges for educational institutions, professional associations and regulators. Alongside these general educational challenges, faculty resistance to change, the digital divide between students, and between students and faculty, and online readiness for study has been a focus of recent research and discourse in health education [ 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ]. More broadly, beyond CM-specific education, tertiary students are increasingly engaging with technology in both their personal and study lives [ 37 , 38 ] and technology-based learning and teaching in higher education is becoming almost a presumed proposition in many undergraduate courses [ 39 , 40 ]. CM education is not exempt from such circumstances and there is a necessity for future research on this topic.

In direct contrast to research related to CM practitioner education, there are numerous studies investigating the degree of, and attitudes to CM in conventional medical training [ 41 , 42 , 43 ], in biomedical education [ 44 ], midwifery [ 45 ], pharmacy [ 46 , 47 , 48 ] and in nursing training [ 44 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 ]. Paradoxically, much of the research regarding CM education relates to its importance and application in nursing education [ 53 ], or the experience of integrating naturopathy into nursing educational programs [ 54 ], the education of physicians about their patients and CM [ 55 ], or addressing the obstacles to success in the implementing of change in science delivery in nursing [ 56 ].

The growing CM workforce requires training appropriate to performing evidence-informed, co-ordinated and inter-professional care within the broader health system and developing the evidence-base on this topic will not only aid the CM field but also provide potential insights for health/medical education more broadly [ 57 ]. The development of a robust evidence-base on this topic requires a clear understanding of the current landscape. Unfortunately, there has been no critical review of the peer-reviewed research examining CM education to date. In direct response to this important research gap, this paper reports the first critical review of contemporary literature examining a number of key issues across the CM education field.

The aim of this critical integrative review [ 58 ] was to review all published original research found in peer-reviewed literature examining education within higher educational institutions that provide training for CM professionals.

A database search was undertaken to identify original peer-reviewed literature published from 2005 to 2017 reporting on issues relating to CM education. This date range was chosen to reflect contemporary issues and ensure findings were as pertinent to current practice and policy as possible.

Search strategy

The search was conducted in May 2017 and included the systematic search of PubMed and EBSCO (CINAHL, MEDLINE, AMED). MESH terms and keywords from related papers were explored to guide the process of selecting search terms, and the process was further refined after referral to a related 2014 review [ 59 ]. The first stage was conducted in PubMed. Search A - The search terms embracing CM included, Complementary Therapies, Complementary Medicine, Homeopathy, Naturopathy, Herbal Medicine, Acupuncture, Acupuncture Therapy, Medicine, Chinese Traditional, Massage, Therapy, Soft Tissue, Integrative Medicine, Medicine, Traditional, Holistic Health, Osteopathic Medicine, Manipulation, Chiropractic, Musculoskeletal Manipulations, Physical Therapy Modalities. Filter 2005–2017. ( n = 258,099). Search B - The search terms embracing education included, education, learning, curriculum, teaching, health occupation students, eLearning, E-Learning, online learning, educational technologies, blended learning. Filter 2005–2017. ( n = 906,575). A + B Combined ( n = 38,441). Stage 2 was conducted in EBSCO. The same search terms used in PubMed when entered into EBSCO provided millions of hits, education ( n = 160 + M) hits, Complementary Therapies ( n = 629,674) hits and too many potential papers to work. Including ‘eLearning’ and ‘e-learning’ was manageable but these two terms with ‘learning technologies’ made it impossible to proceed. In the process, a review was located which had used similar terms but a different strategy, Milanes 2014 systematic review, Is a blended learning approach effective for learning in allied health clinicians? Because of the enormous number of hits using the EBSCO database, and based on this article a revised search method was undertaken for the EBSCO search. Search C - EBSCO Search terms, 1. Online learning OR blended learning or web-based learning, 2. e-learning OR elearning, 3. education* OR curriculum* OR teaching* OR learn*, 4. Combine all (1–3) with AND 5. Complementary Therapies*, 6. Search 4 AND 5 ( n = 637), 7 Limit to articles from 2005 ( n = 567 (with duplicates removed)). Search D - This process was completed again searching on the slightly different terminology. Search terms, 1. Online learning OR blended learning or web-based learning, 2. e-learning OR elearning, 3. education* OR curriculum* OR teaching* OR learn*, 4. Combine all (1–3) with AND, 5. Complementary Medicine*, 6. Search 4 AND 5 = 1203, 7. Limit to articles from 2005 = ( n = 1013 (with duplicates removed)). Stage 3 (Milanes Refined) PubMed. Search E - The search terms Health occupation students OR educational technologies OR teaching OR curriculum AND complementary therapies, filter to last 10 years. Search results = ( n = 8439). Totals: Search C – n = 567, Search D – n = 1013, Search E – n = 8439. Total Papers n = 10,019. Duplicates removed n = 523. Grand Total 9496. Manual searching of reference lists of identified papers was also conducted to ensure as full coverage of literature as possible.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Papers written in English, presenting original empirical research data, related to courses where graduates receive a qualification in a CM to a standard accepted by those professions and reporting on the prevalence or nature of the education of CM practitioners in some way were included in the review. Papers reporting conference presentations, or studies relating to how pharmacy, nursing or registered medical professionals are educated regarding their patient behaviours or looking to how they accumulate CPD points in short term CM topics were excluded.

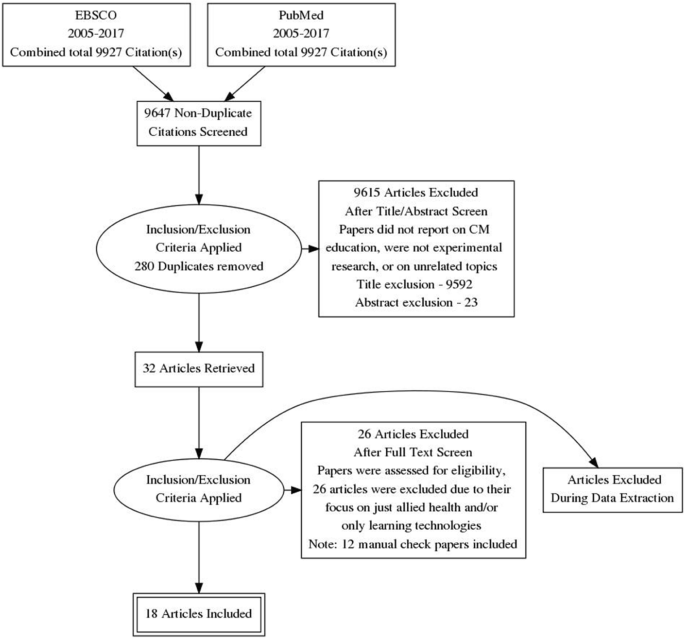

Search outcomes

The combined (Complementary Therapies n = 420,476 and Education n = 102,024) search results ( n = 9927) were imported into Endnote. Of these, 9895 papers were excluded via title and abstract due to not meeting the inclusion criteria, and all identified duplicates ( n = 280) were excluded leaving 32 papers. Upon reviewing full papers an additional 26 articles were excluded due to their focus on just allied health and / or only learning technologies with no CM focus; leaving 6 papers. A total of 12 additional papers were identified for review following manual searches. In total, 18 papers were identified for this review. The process undertaken for this review is presented in Fig. 1 .

Literature Review Methodology and Selection Process flowchart for articles reporting education and CM (PRISMA Guidelines)

Critical analysis of included papers

Our critical literature appraisal employed three analytical tools, STROBE [ 60 , 61 ], SRQR [ 62 ] and MMAT [ 63 ]. Papers were evaluated for quality and the findings are collated in Table 1 .

Of 9927 identified papers, 18 papers met the review inclusion criteria. An overall synopsis of all papers included in the review incorporated preliminary categorical analysis is outlined in Table 2 . The identified studies were conducted in Australia ( n = 7), the US ( n = 5), Norway ( n = 2) and one each from Canada, Taiwan, Israel and India. The research designs reported in the reviewed literature varied widely with quantitative, qualitative and mixed methodologies reported. The quantitative studies selected for review utilized a number of survey design approaches and attracted samples of between 10 and 246 individual participants. The qualitative studies identified employed survey methods [1, 2, 8–14, 18] as well as interviews [1, 6, 11, 15, 16], open essays [2] and focus groups [17]. The spread, focus and identification of themes and topics by CM therapy is represented in Table 2 . The naturopathic profession has received most attention from researchers within the international CM education landscape, followed by acupuncture. There are three studies on homeopathy, two studies of chiropractic, and one each of osteopathy, herbal medicine, ayurveda and massage. Six of the included studies focus on a specific class inside of a CM college [1–4, 7, 17], four on academics in CM institutions [6, 12, 16], four studies surveyed members of professional associations [5, 10, 17], and four surveyed College directors [8, 9, 13, 18]. Thematic categorization of the included papers identified four substantive topic areas: (1) CM education provision, (2) the development of educational competencies to develop clinical skills and standards, (3) the application of existing and new educational theory, methods and technology in CM, and (4) future challenges facing CM education.

CM education provision

The review identified three papers that reported a simple description of educational provision in an area of CM. One study compared naturopathy and chiropractic curricular in Australia. Course structures and subject unit descriptions for accredited naturopathic courses were examined from websites where they existed and in some instances short follow-up interviews were conducted. This study reported the percentage of curriculum devoted to medical sciences and clinical training whereby it was found that on average, chiropractic courses allocated 45.9% of their curricula to medical sciences, whereas university-based naturopathy courses allocated 26.2% to medical science and non-university naturopathy courses allocated 23.1% [ 64 ]. Another study reported on the scope of education provision in homeopathy and examined the preponderance of accredited full-time and part-time courses and accredited and non-accredited courses in Europe. This cross-sectional survey of 85 homeopathy education providers found an average of 47 enrolled students and 142 graduates in these generally small schools. Course duration lasted on average 3.6 years part-time, less than half had entry requirements, provided any medical science education or required students to obtain medical science tuition elsewhere. Average teaching hours at surveyed schools were 992 overall, with 555 h devoted to didactic homeopathy study, while the rest focused on clinical training [ 65 ]. A similar 2009 study focused on the demographics, satisfaction, challenges and expectations of homeopathy students, teachers and school administrators in North America. The study consisted of three separate surveys targeted at homeopathy students, faculty and school directors consisting of 40 questions with a 91.5% completion rate [ 66 ]. It was found that there were 29 homeopathy schools, with 250 teachers and 1080 students currently enrolled in the United States. Programs varied considerably in length; however the average program (670 h) was barely sufficient to meet the minimum standards for homeopathic certification. Homeopathy teachers tend to be older than both homeopathy students or practitioners. The average age of students is 54.3 years old. Although the vast majority of students are female (90%) and practitioners are female (75%), males are much more common as teachers (43.5%) and school directors (45%). As with homeopathy students, practitioners, and teachers, homeopathy school directors are nearly all Caucasian (85%). An important conclusion was that education in homeopathy in the United States has largely remained stagnant in the last 10 years. Although many new schools have been formed, many have closed. It was not speculated as to the cause.

The development of educational competencies to develop clinical skills and standards

Eight papers from the review focused on improving education and clinical skills in CM. One study reporting findings from 43 education providers of naturopathy and western herbal medicine in Australia found educational standards varied widely, including unsustainable variations in award types, contact hours, clinical education, length of courses and course content with some practitioners unlikely to be trained to professional standards. This study found a need for better integration of complementary care with mainstream healthcare necessitating education to rise to the level of a bachelor degree [ 67 ]. The development or application of learning competencies was a focus of these eight papers. Competencies and competency models refer to how the knowledge, skills, and abilities required by these standards are structured. In a study focussing on the skills, knowledge, attributes and competencies of homeopaths and homeopathy education provision, telephone interviews with 17 educators from different schools in 10 European countries were conducted [ 68 ]. This qualitative study used constant/simultaneous comparison and analysis to develop categories and properties of educational needs and theoretical constructs and to describe behaviour and social processes and showed educators define a competent homeopath as a professional able to help patients in the best way possible. It was found that course providers and teachers required the competency to be student-centred, and students and homeopaths to be patient-centred [ 68 ]. In an Australian study, CM practitioners were reported as having a low level of confidence in identifying clients requiring referral to registered health practitioners, despite the reported high frequency of educational training in, and use of, Western and CM diagnostic techniques [ 69 ].

Two identified papers focused on teaching aspects of practitioner communication skills and the integration of complementary and conventional medicine in CM schools. Using a pre-course ‘semi-structured questionnaire’ plus surveys after an educational intervention, 62 students in Israel reported on how the communication gap with conventional physicians and CM practitioners could be improved [ 70 ]. This study found that CM practitioners perceived themselves as better equipped to communicate with conventional health care practitioners when critical thinking, patient-centered care, and communicating skills were emphasized in their course of undergraduate study [ 70 ]. In addition, a Canadian study published findings derived from 28 directors of colleges of CM. The author reported that student’s ability to understand research findings, to rely on high quality research and to engage in continuing education was important in communicating with conventional care providers [ 71 ].

Meanwhile, the need for schools to adopt research literacy and evidence based practice competencies was the focus of three papers. One study that examined the attitudes towards research and scholarly activity of 202 faculty academics in an Australian CM college reported low confidence in undertaking research [ 72 ]. Respondents in this Australian study perceived research as important to their personal professional goals (86.0%) although confidence in being able to undertake research was less common (56.5%). The perceived importance of publication of research to the respondents’ personal professional goals was also notably high (80.0%) although confidence in their own ability to produce research publications was lower (52.9%) [ 72 ]. Another study conducted in the US examined the approaches of 9 CM colleges to develop evidence-informed skills and knowledge with the aim of developing both students and faculty to critically appraise evidence and then employ that evidence to guide clinical practice [ 73 ]. This study found that in developing the framework for their educational programs, educational institutions used strategies that were viewed critical for success, including making them multifaceted and unique to their specific institutional needs. It was found that these strategies, in conjunction with existing instructional approaches, were of practical use in other CM and non-CM academic environments where administrators were considering the introduction of research literacy and EBP competencies into their curricula. Training programs and workshops were found to be the most useful way to train faculty in evidence based medicine and research literacy [ 74 ]. Finally, one reviewed paper reported on the educational competencies and institutional teaching strategies that had been developed and implemented to enhance research literacy at all nine R25-funded CM institutions in the US [ 73 ]. This study found that while each institution designed approaches suitable for its own research culture, the guiding principles were similar across all, and the need to develop evidence-informed skills and knowledge was important to help students and faculty to critically appraise evidence and then use that evidence to guide their clinical practice. The strategies adopted by these institutions included a need for course content to be conducive to reinforcing EBM competencies using spiral learning strategies, and that faculty were willing to learn and teach EBM skills [ 73 ].

Application of existing and new educational theory, methods and technology in CM

The changing role of the trainer/lecturer in didactic and clinical subjects, the application of existing and new educational theory and problem-based learning within the context of CM curricula in bachelor and medical college programs, as well as the growing use of learning technologies was highlighted by six papers included in the review. In one study three educational interventions testing new teaching methods were introduced in an ayurveda program [ 75 ]. The instructional methods that were evaluated were an integrative module on cardiovascular physiology, case-stimulated learning and classroom small group discussion with findings showing the development of testable integrative teaching methods is possible in the context of Ayurveda education [ 75 ]. In contrast, findings from an educational intervention, the implementation of an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) model as well as a patient-centered training approach within traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) practitioner education in one Taiwanese medical school, found this examination approach effective in evaluating, teaching, and certifying TCM clinical competencies to improve the quality of TCM practices. In this study the training program subjects included TCM internal medicine, TCM genecology, TCM paediatrics, TCM dietetics, acupuncture, TCM orthopaedics, and traumatology [ 76 ].

When it comes to resources and the use of technologies, Wardle’s 2014 study used focus groups with current and recent students of 4-year naturopathic degree programs in Australia to ascertain how they interact with clinical teaching materials, and their perceptions and attitudes towards teaching materials in naturopathic education. This study described a desire among naturopathy students for existing curriculum to focus on evidence-based approaches and information that both supported and was critical of traditional naturopathic practices. These students remained largely ambivalent about new teaching technologies and preferred that these develop organically as an evolution from printed materials, rather than depart dramatically and radically from these previously established materials [ 17 ]. CM student’s preferred learning methods are often based on levels of computer skills and experience, their current use of computers as an educational tool, and attitudes regarding the role of computers in medical education according to a cross sectional survey study from a 27-item questionnaire distributed to 1–4-year Osteopathic medical students in the US [ 77 ]. One ethnographic study based on interviews conducted in the Australian university system with Naturopathic Faculty found an openness to the utilization of a number of technologies for flexible learning, including wikis, podcasts and synchronous audio-based online interactions [ 78 ]. In contrast, another study in the US found acupuncture, chiropractic, and massage therapy faculty lacked awareness of the capabilities of online education and the elements of good online learning and described a perception that what they taught could not be taught online because of its hands-on kinaesthetic requirements such as palpation [ 79 ].

Future challenges facing CM education

Lastly, one paper included in our review identified some of the challenges ahead for the Australian naturopathic profession including naturopathic education, the changing student body in naturopathic education, naturopathic student expectations, and the growing tension between traditional and scientific evidence [ 80 ]. This study, involving semi-structured interviews with 20 naturopaths, found that participants articulated a paradox whereby on the one hand, they supported the teaching of increased levels of biomedical sciences in naturopathic education, yet also complained of the trend of contemporary naturopathic education to “become more scientific” – a trend they attributed to their desire for the discipline to be “accepted in the university sector”. The participants claimed that such a development would be undertaken at the expense of the philosophical underpinnings of the profession. The authors found the continued development of minimum standards of practice and education that value traditional naturopathic principles and philosophies in tandem with the development of appropriate regulatory regimes, was vital in ensuring continued ethical and effective clinical practice.

Quality of papers

Based on the STROBE reporting guidelines [ 60 ] the quantitative papers included in this study, while rich in design, descriptive data and discussion of results exhibited a broad weakness in stating clear objectives. In addition, statements and acknowledgement of bias were mostly absent. Other elements commonly missing from these papers were descriptions of statistical methods and generalisability leaving a general impression of low quality among the included papers. Based on the SRQR [ 62 ] tool for evaluating qualitative studies, all selected papers omitted a discussion on the qualitative approach and research paradigm used. A description of researcher characteristics and reflexivity, and techniques to enhance trustworthiness and credibility of data analysis were mostly missing. In addition, potential sources of influence or perceived influence on study conduct and conclusions and how these were managed were also under-reported across this collected literature. In addition, a lack of reporting on sources of funding and other support, the role of funders in data collection, interpretation, and write-up were other weaknesses identified. The application of the MMAT critical appraisal tool for the mixed methods studies [ 63 ] in this instance found all papers used, included and reported appropriate sources of data relevant to answer the research question, took into account the context in data analysis, used appropriate sampling to answer the research question, and integrated qualitative and quantitative data and/or results. On the other hand, only some papers applied features of the tool such as data analysis relevant to answer the research question, and only a few reported on complete outcome data, or dropout rate, reported on recruitment minimizing bias and appropriate follow-up, used appropriate randomization, appropriate measurement, sample representative of the population, or appropriate measurement. No papers reported on the reflexivity of researchers, nor concealment allocation, and only a few reported on the mixed method design relevant to answer the research questions, integrated the mixed qualitative and quantitative data and results nor took into consideration any limitations associated with this integration, leaving an overall impression of poor quality.

This critical integrative review highlights two key issues and large current empirical gaps. Firstly, given the growing popularity of CM and as a consequence the growth in CM education, there is very sporadic coverage of research in the CM education field. Across the 18 included papers, research from 7 countries is represented with 4 of those countries having only one identified relevant paper. In addition, the quantity and quality of available evidence invariably relates to disparate, random and unrelated parts of CM education philosophy and practice. Our review findings highlight that much of the research is now relatively dated [ 81 ]. In addition, there is extreme diversity in the represented professions and ultimately the quality of papers. Many papers were excluded due to inconsistencies between title, abstract and findings [ 82 ]. Some papers were relevant but not published in peer reviewed journals and thus excluded; highlighting how in a maturing field there is a need to publish in both professional industry journals and the peer reviewed literature. One such example was the result of a survey of ‘profession-wide’ educational acupuncture institutions in the US as well as an extensive literature review, subject matter expert interviews, community discussions, strategic planning, analysis, and evaluation, that called for the development of educational competencies [ 83 ]. Others examples were the Survey on Inter-institutional and Interprofessional Relationships of Accredited Complementary and Alternative Medicine Schools and Consortium of Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine Programs [ 84 ], the National Education Dialogue to Advance Integrated Health Care: Creating Common Ground [ 84 ], the Project for Inter- Institutional Education Relationships [ 85 ]: Examples of Real Life Inter-Institutional Collaborations [ 84 ], and the Credentialing Licensed Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine Professionals for Practice in Healthcare Organizations: An Overview and Guidance for Hospital Administrators, Acupuncturists and Educators [ 84 ].