An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

The etiology of social anxiety disorder: An evidence-based model

Affiliations.

- 1 School of Applied Psychology and Australian Institute for Suicide Prevention and Research, Griffith University, Brisbane, QLD 4121, Australia. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Centre for Emotional Health, Department of Psychology, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW 2109, Australia.

- PMID: 27406470

- DOI: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.06.007

The current paper presents an update to the model of social anxiety disorder (social phobia) published by Rapee and Spence (2004). It evaluates the research over the intervening 11 years and advances the original model in response to the empirical evidence. We review the recent literature regarding the impact of genetic and biological influences, temperament, cognitive factors, peer relationships, parenting, adverse life events and cultural variables upon the development of SAD. The paper draws together recent literature demonstrating the complex interplay between these variables, and highlights the many etiological pathways. While acknowledging the considerable progress in the empirical literature, the significant gaps in knowledge are noted, particularly the need for further longitudinal research to clarify causal pathways, and moderating and mediating effects. The resulting model will be valuable in informing the design of more effective treatment and preventive interventions for SAD and will provide a useful platform to guide future research directions.

Copyright © 2016 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

PubMed Disclaimer

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Elsevier Science

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Social context and the real-world consequences of social anxiety

1 Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 USA

Kathryn A. DeYoung

2 Department of Family Science, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 USA

4 Department of Center for Healthy Families, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 USA

Samiha Islam

Allegra s. anderson.

7 Department of Psychological Sciences, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37240 USA

Matthew G. Barstead

3 Department of Human Development and Quantitative Methodology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 USA

Alexander J. Shackman

5 Department of Neuroscience and Cognitive Science Program, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 USA

6 Department of Maryland Neuroimaging Center, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 USA

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Associated Data

Social anxiety lies on a continuum, and young adults with elevated symptoms are at risk for developing a range of debilitating psychiatric disorders. Yet, relatively little is known about the factors that govern the hour-by-hour experience and expression of social anxiety in daily life.

Here, we used smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to intensively sample emotional experience across different social contexts in the daily lives of 228 young adults selectively recruited to represent a broad spectrum of social anxiety symptoms.

Leveraging data from over 11,000 real-world assessments, results highlight the central role of close friends, family members, and romantic partners. The presence of close companions is associated with enhanced mood, yet socially anxious individuals have smaller confidant networks and spend less time with their close companions. Although higher levels of social anxiety are associated with a general worsening of mood, socially anxious individuals appear to derive larger benefits—lower levels of negative affect, anxiety, and depression—from the presence of their closest companions. In contrast, variation in social anxiety was unrelated to the amount of time spent with strangers, co-workers, and acquaintances; and we uncovered no evidence of emotional hypersensitivity to less-familiar individuals.

Conclusions

Collectively, these findings provide a framework for understanding the deleterious consequences of social anxiety in emerging adulthood and set the stage for developing improved intervention strategies.

INTRODUCTION

Socially anxious individuals are prone to heightened fear, anxiety, and avoidance of social interactions and situations associated with potential social scrutiny ( Alden and Taylor 2004 , Heimberg et al. 2014 ). In addition to heightened negative affect (NA), socially anxious individuals tend to report lower levels of positive affect (PA) ( Kashdan and Collins 2010 , Anderson and Hope 2008 , Kashdan et al. 2011 , Geyer et al. 2018 ). Social anxiety symptoms lie on a continuum and, when extreme, can become debilitating ( Rapee and Spence 2004 , Craske et al. 2017 , Kessler 2003 , Lipsitz and Schneier 2000 , Katzelnick et al. 2001 , Stein et al. 2017 , Conway et al. 2019 , Krueger et al. 2018 , Ruscio 2019 ). Social anxiety disorder is among the most prevalent mental illnesses; contributes to the development of other psychiatric disorders, such as depression; and is challenging to treat ( Mathew et al. 2011 , Schneier et al. 1992 , Stein et al. 2017 , Craske et al. 2017 , Acarturk et al. 2009 , Rodebaugh et al. 2004 , Neubauer et al. 2013 ). Relapse and recurrence are common, and pharmaceutical treatments are associated with significant adverse effects ( Gordon and Redish 2016 , Batelaan et al. 2017 , Spinhoven et al. 2016 , Scholten et al. 2013 , Scholten et al. 2016 , Bruce et al. 2005 , Rhebergen et al. 2011 ). Yet the situational factors that govern the momentary experience and expression of social anxiety in the real world remain incompletely understood. To date, most of what it known is based on either retrospective report or acute laboratory challenges ( Afram and Kashdan 2015 , Alden and Wallace 1995 , Beck et al. 2006 , Buote et al. 2007 , Crişan et al. 2016 ).

As part of an on-going prospective-longitudinal study focused on individuals at risk for the development of mood and anxiety disorders, we used smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to intensively sample momentary levels of negative and positive affect in the daily lives of 228 young adults. Subjects were selectively recruited from a pool of 6,594 individuals screened for individual differences in dispositional negativity (i.e., negative emotionality), the tendency to experience more intense, frequent, or persistent levels of depression, worry, fear and anxiety—including social anxiety ( Shackman et al. 2016 , Hur et al. in press ). This ‘enrichment’ strategy enabled us to examine a broader spectrum of social anxiety symptoms than alternate approaches, such as convenience sampling. Because EMA data are captured in real time (e.g., Who are you with? ), they circumvent the biases that can distort retrospective reports, providing insights into how emotional experience dynamically responds to moment-by-moment changes in social context ( Lay et al. 2017 , Barrett 1997 , Csikszentmihalyi et al. 2013 , Shiffman et al. 2008 ). We focused on young adulthood because it is a time of profound, often stressful developmental transitions (e.g., moving away from home, forging new social relationships; Hays and Oxley 1986 , Alloy and Abramson 1999 , Arnett 2000 , Pancer et al. 2000 ). In fact, more than half of undergraduate students report overwhelming anxiety, with many experiencing the first onset or a recurrence of anxiety and mood disorders during this period ( Stein et al. 2017 , Global Burden of Disease Collaborators 2016 , Auerbach et al. 2016 , Auerbach et al. in press, Lipson et al. in press, American College Health Association 2016 ). In particular, those with elevated levels of social anxiety tend to experience substantial distress and impairment and are more likely to develop psychopathology ( Merikangas et al. 2002 ).

We were particularly interested in understanding how the momentary emotional experience of socially anxious individuals varies as a function of social context. Emotion is often profoundly social ( Fox and Shackman 2018 ). For instance, emotional experiences are routinely shared and dissected with friends, family, and romantic partners ( Rime 2009 ). Humans and other primates routinely seek the company of close companions in response to stressors, and increased social engagement promotes positive affect ( Shackman et al. 2018 , Cottrell and Epley 1977 ). Indeed, there is abundant evidence that close companions play a critical role in coping with stress and regulating negative affect ( Bolger and Eckenrode 1991 , Buote et al. 2007 , Coan and Sbarra 2015 , Marroquin 2011 , Myers 1999 , Zaki and Williams 2013 , Wade and Kendler 2000 , Kendler and Gardner 2014 , Ramsey and Gentzler 2015 , Reeck et al. 2016 ). Yet, many of these beneficial effects appear to be disrupted in socially anxious individuals ( Alden and Taylor 2004 ).

We began by testing whether social anxiety is associated with the amount of time allocated to different social contexts (e.g., with close companions) and whether this reflects the number of self-reported confidants. Social avoidance is diagnostic of social anxiety disorder, is a key component of dimensional measures of social anxiety, and contributes to functional impairment and reduced quality of life ( Liebowitz 1987 , APA 2013 , Beidel et al. 1999 , Strahan and Conger 1999 , Turner et al. 1986 ). Among community samples, adults with elevated levels of social anxiety are less likely to have a close friend and more likely to be unmarried by mid-life ( Davidson et al. 1994 ). They are also more likely to be lonely ( Lim et al. 2016 ). Recent work using unobtrusive, smartphone-based global positioning system (GPS) data provides additional evidence suggestive of social inhibition and avoidance ( Boukhechba et al. 2018 ), demonstrating that socially anxious university students spend significantly less time at ‘leisure’ (e.g., gymnasiums, pubs, cinemas, and coffee shops) and ‘food’ (e.g., restaurants, food courts, and dining halls) locations during peak hours in the evening. Socially anxious students also spent more time at home or off-campus (e.g., parents’ home), particularly on weekends, and visited fewer locations overall, suggesting a more restricted range of activities (see also Chow et al. 2017 ). Whether this pattern reflects generalized avoidance, specific avoidance of socially ‘distant’ individuals (e.g., strangers, acquaintances), or a lack of confidants remains unknown.

Next, we used a series of multilevel models (MLMs) to understand the interactive effects of social anxiety and the social environment on momentary affect. This enabled us to test whether socially anxious individuals experience heightened NA and attenuated PA in the presence of distant others, as one would expect based on laboratory studies of semi-structured and unstructured interactions with unfamiliar peers and researchers ( Kashdan et al. 2013b , Kashdan and Roberts 2004 , Kashdan and Roberts 2006 , Kashdan and Roberts 2007 , Heerey and Kring 2007 , Crişan et al. 2016 , Coles et al. 2002 , Creed and Funder 1998 , Meleshko and Alden 1993 ). Likewise, EMA research indicates that children with social anxiety disorder experience diminished PA in the presence of distant others ( Morgan et al. 2017 ). Whether this pattern is evident in adults is, as yet, unknown.

Using a MLM approach, we also tested two competing predictions about the consequences of close companions. One possibility is that socially anxious individuals derive increased emotional benefits (e.g., lower levels of NA) from close companions. Consistent with this view, the presence of a friend has been shown to normalize behavioral signs of anxiety and reduce negative self-thoughts in socially anxious adults exposed to an experimental speech challenge ( Pontari 2009 ). Likewise, diary studies suggest that spousal support plays a key role in dampening negative affect among patients with social anxiety disorder ( Zaider et al. 2010 ) and EMA studies suggests that the presence of close companions is associated with disproportionately enhanced PA in children with social anxiety disorder ( Morgan et al. 2017 ) and adults with elevated levels of dispositional negativity ( Shackman et al. 2018 ). More broadly, a variety of work suggests that individuals with low levels of psychological well-being and patients with depression reap larger emotional benefits from positive daily events ( Rottenberg 2017 , Lamers et al. 2018 , Grosse Rueschkamp et al. in press ). Although socially anxious adults often show symptoms of depression and anhedonia, it is unclear whether similar benefits extend to this population.

A competing possibility is that socially anxious individuals fail to capitalize on available socio-emotional support. Indeed, socially anxious individuals tend to be less emotionally expressive, disclosing, and intimate with companions ( Cuming and Rapee 2010 , Meleshko and Alden 1993 , Sparrevohn and Rapee 2009 , Vernberg et al. 1992 , Williams et al. 2018 ). They perceive themselves as receiving less social support ( Torgrud et al. 2004 , Cuming and Rapee 2010 , La Greca and Lopez 1998 ); perceive their friendships to be of a lower quality ( Rodebaugh 2009 , Rodebaugh et al. 2015 ); are less satisfied with friends, family, and romantic partners ( Stein and Kean 2000 , Wong et al. 2012 , Starr and Davila 2008 ); and are prone to emotional neediness and overreliance ( Davila and Beck 2002 , Darcy et al. 2005 ). Perhaps as a consequence, socially anxious individuals report elevated levels of interpersonal conflict ( Cuming and Rapee 2010 ) and, among patients, marked impairment of interpersonal relationships ( Wittchen et al. 2000 , Rapaport et al. 2005 , Olatunji et al. 2007 , Stein et al. 2017 ). Collectively, these observations motivate the prediction that socially anxious individuals derive smaller emotional benefits or even costs (e.g., higher levels of NA) from close companions.

Discovering the situational factors associated with the real-world experience of social anxiety is important. The identification of potentially modifiable targets, such as social context, has the potential to guide the development of improved intervention strategies.

As part of an on-going prospective-longitudinal study focused on individuals at risk for the development of internalizing disorders, we used well-established measures of dispositional negativity (often termed neuroticism or negative emotionality; Shackman et al. 2016 , Shackman et al. 2018 ) to screen 6,594 young adults (57.1% female; 59.0% White, 19.0% Asian, 9.9% African American, 6.3% Hispanic, 5.8% Multiracial/Other; M = 19.2 years, SD = 1.1 years). Screening data were stratified into quartiles (top quartile, middle quartiles, bottom quartile) separately for males and females. Individuals who met preliminary inclusion criteria were independently recruited from each of the resulting six strata. Approximately half the subjects were recruited from the top quartile, with the remainder split between the middle and bottom quartiles (i.e., 50% high, 25% medium, and 25% low). Given the typically robust relations between measures of dispositional negativity and social anxiety— R 2 = .25 in the present sample—this ‘enrichment’ strategy allowed us to examine a relatively wide range of social anxiety symptoms without gaps or discontinuities. All subjects were first-year university students in good physical health and access to a smartphone. All reported the absence of a lifetime psychotic, bipolar, neurological, or developmental disorder. Given the focus of the larger prospective-longitudinal study on risk for the development of mental illness, all subjects reported the absence of current alcohol/substance abuse, suicidal ideation, internalizing disorder (past 2 months), and psychiatric treatment. To maximize the range of psychiatric risk, subjects with a lifetime history of anxiety and mood disorders were not excluded, consistent with prior work (Alloy, Abramson et al. 2000). At the baseline laboratory session, subjects provided informed written consent, were familiarized with the EMA protocol (see below), and completed the social anxiety and social network assessments. Beginning the next day, subjects completed up to 8 EMA surveys/day for 7 days. All procedures were approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board and the sample does not overlap with that detailed in prior work by our group ( Shackman et al. 2018 ).

Two-hundred and forty-two subjects completed the baseline assessment and EMA protocol. Fourteen subjects were excluded from analyses: 2 withdrew and 12 (~5%) failed to complete >39 survey prompts (70% compliance). The final sample included 228 subjects (51.3% female; 62.7% White, 17.5% Asian, 8.3% African American, 4.9% Hispanic, 6.6% Multiracial/Other; M = 18.76 years, SD = 0.35 years).

Power Analysis

Sample size was determined a priori as part of the application for the award that supported this research (R01-MH107444). The target sample size ( N ≈ 240) was chosen to afford acceptable power and precision given available resources (Schönbrodt & Perugini, 2013). At the time of study design, G-power 3.1.9.2 ( http://www.gpower.hhu.de ) indicated >99% power to detect a benchmark medium-sized effect ( r = .30) with up to 20% planned attrition ( N = 192 usable datasets) using α = .05 (two-tailed).

Social Anxiety

At baseline, the self-report version of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) was used to quantify social anxiety ( Liebowitz 1987 ). Subjects used a 0 ( none ) to 3 ( severe ) scale to rate the amount of fear and anxiety they typically experience in response to 24 everyday situations (e.g., going to a party , meeting strangers , returning goods to a store , speaking up at meeting ). They used a 0 ( never ) to 3 ( usually ) rating scale to rate frequency of avoiding the 24 situations. Social anxiety was quantified by summing the 48 responses. As shown in Figure 1 , LSAS scores were approximately normally distributed ( M = 41.7, SD = 22.0, Range = 1–121, α = .95) and somewhat higher than that previously reported in large university convenience samples (N = 856, M = 34.7, SD = 20.4; Russell and Shaw 2009 ) 1 , 2 .

Social anxiety was assessed at baseline using the self-report version of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS). The two highest cases were not excluded because they are sensible—given the nature of the scale and the sample—and because they did not exert undue statistical leverage ( Hoaglin and Iglewicz, 1987 , Hoaglin et al., 1986 ). Exploratory analyses indicated that the exclusion of these cases did not meaningfully alter the results (not reported).

Social Network Size

At baseline, the number of close companions was measured using an item ( How many people do you know where you have a close, confiding relationship and can share your most private feelings? ) from the modified Kendler Social Support Inventory (MKSSI; Spoozak et al. 2009 ). Single-item measures of social network size are routinely used in epidemiology research (e.g., Kendler et al. 2005 , Kocalevent et al. 2018 , Van Lente et al. 2012 ). The resulting descriptive statistics ( M = 5.6, SD = 4.1, Range = 0 – 30) are broadly consistent with the results of past work focused on confidant networks in university students ( Sarason et al. 1983 , Freberg et al. 2010 ) and friendship networks in community-dwelling adults ( Wang and Wellman 2010 ).

EMA Procedures

SurveySignal ( Hofmann and Patel 2015 ) was used to automatically deliver 8 text messages/day to each subject’s smartphone. On weekdays, messages were delivered every 1.5 to 3 hours ( M = 115 minutes, SD = 25) between 8:30 AM and 10:30 PM. As in prior work by our group ( Shackman et al. 2018 ), weekday messages were delivered during the ‘passing periods’ between regularly scheduled university courses to maximize compliance. On weekends, messages were delivered every 1.5 to 2.5 hours ( M = 99 minutes, SD = 17) between 11:00 AM and 11:00 PM. Messages were delivered according to a fixed schedule that varied across days (e.g., the third message was delivered at 12:52 PM on Mondays and 12:16 PM on Tuesdays). Messages contained a link to a secure on-line survey. Subjects were instructed to respond within 30 minutes (Latency: Median = 2 min, SD = 7 min, Interquartile Range = 9 min) and to refrain from responding at unsafe or inconvenient moments (e.g., while driving). A reminder was sent when subjects failed to respond within 15 minutes. During the baseline laboratory session, several well-established procedures were used to maximize compliance ( Palmier‐Claus et al. 2011 ), including: (1) delivering a test message in the laboratory and confirming that the subject was able to successfully complete the on-line EMA survey, (2) 24/7 technical support, and (3) monetary bonuses. Base compensation was $10, with $20 bonuses for ≥70% and ≥80% compliance, respectively ( Total = $10-$50). In the final sample, EMA compliance was acceptable ( M = 87.9%, SD = 6.2%, Minimum = 71.4%, Total = 11,224) and unrelated to social anxiety, p = .77.

Current NA ( afraid, nervous, worried, hopeless, sad ) and PA ( calm, cheerful, content, enthusiastic, joy, relaxed ) at the time of the survey prompt was rated using a 0 ( not at all ) to 4 ( extremely ) scale. Subjects also indicated their current social context ( “At the time of ping, who was around?” ): alone, close friend(s), family, friend(s), romantic partner, acquaintance(s), co-worker(s), and/or stranger(s). Composite measures of NA and PA were computed by averaging the relevant items ( α s > .92). To enable follow-up assessments of generality, composite anxiety ( afraid, nervous, worried ) and depression ( hopeless, sad ) facet scales were computed ( α s > .88). Building on prior work by our group and others ( Shackman et al. 2018 , Diener and Seligman 2002 ), friends, close friends, family, and romantic partners were re-coded as ‘Close’ companions. Acquaintances, co-workers, and strangers were re-coded as ‘Distant’ companions. This approach is conceptually similar to the distinction between ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ social connections ( Granovetter 1973 ). Analyses indicated that assessments completed in the presence of a mixture of Close and Distant companions (8%) showed intermediate effects and are omitted from the report.

Analytic Strategy

The overarching aim of the present study was to understand the joint explanatory influence of Social Anxiety (LSAS) and Social Context (EMA) on real-world Affect (EMA-derived NA, PA). In all cases, hypothesis testing employed a continuous measure of Social Anxiety.

We began by testing whether variation in Social Anxiety prospectively predicts the aggregate amount of time allocated to different social contexts. A standard multivariate mediation framework was then used to test whether relations between Social Anxiety and Social Context were statistically attributable, in part, to variation in Social Network Size (e.g., elevated social anxiety → fewer confidants → less time with close companions ) ( Hayes 2017 ), where Size was indexed using the MKSSI. As in prior work by our group ( Stout et al. 2017 ), the significance of the indirect effect (‘mediation’) was assessed using non-parametric bootstrapping (5,000 samples). Although the mediation framework provides useful information, it rests on strong assumptions and positive results do not license causal inferences ( Green et al. 2010 , Bullock et al. 2010 ). Pirateplots were created using the yaRrr package for R ( Phillips 2017 ). Hotelling’s test for dependent correlations was computed using FZT ( https://psych.unl.edu/psycrs/statpage/comp.html ).

Next, a series of MLMs was implemented in SPSS (version 24.0.0.0) with momentary assessments of Affect and Social Context nested within subjects and intercepts free to vary across subjects. Separate MLMs were computed for NA and PA. Level 2 variables (i.e., Social Anxiety) were mean centered.

The equations defined below outline the basic structure of our final MLMs in standard notation ( Raudenbush and Bryk 2002 ). At the first level, Affect during EMA t for individual i was modeled as a function of Social Context:

Alone served as the dummy-coded reference category for primary analyses (as in Equation 1 ). Distant companions served as the reference category for follow-up analyses 3 .

At the second level, the association between Social Context and Affect was modeled as a function of individual differences in Social Anxiety:

Conceptually, this enabled us to test prospective relations between Social Anxiety and Affect, cross-sectional relations between EMA-derived measures of Social Context and Affect, and the potentially interactive effects of Social Anxiety and Social Context. We also explored the impact of incorporating variation in the amount of time allocated to different contexts as a nuisance variable. For significant effects, we examined generality across NA facets (i.e., anxious and depressed mood). As an additional validity check, we confirmed that similar results were obtained when two authors independently analyzed the data using SPSS (J.H.) and R (M.G.B.), respectively.

Momentary Emotional Experience Covaries with Social Context

Consistent with other work in young adults ( Shackman et al. 2018 , Reed W Larson 1990 , Berry and Hansen 1996 ), our sample spent slightly more than half their time with others (Close = 44.1%, Distant = 13.4%, Alone = 42.5%), although there were marked individual differences in the amount of time devoted to each social environment ( Figure 2 ). Individuals who spent more time with close others reported lower average levels of NA ( r = −.14, p = .03) and higher average levels of PA ( r = .31, p < .000). Conversely, those who spent more time alone reported higher average levels of NA ( r = .14, p = .03) and lower average levels of PA ( r = −.28, p < .001), replicating past work (e.g., Diener and Seligman 2002 , Shackman et al. 2018 , Oishi et al. 2007 , Diener et al. 2018 , Rogers et al. 2018 ). The average amount of time spent with distant others was unrelated to average mood ( p s > .20). In sum, individuals who spend more time with close companions report modestly enhanced mood, whereas those who are prone to seclusion show the opposite effect.

Figure depicts the data ( jittered gray points; individual participants ), density distribution ( colored bean plots ), Bayesian 95% highest density interval (HDI; white bands ), and mean ( black bars ) for each social context. HDIs permit population-generalizable visual inferences about mean differences and were estimated using 1,000 samples from a posterior Gaussian distribution

Socially Anxious Individuals Spend Less Time with Close Companions and Have Smaller Confidant Networks

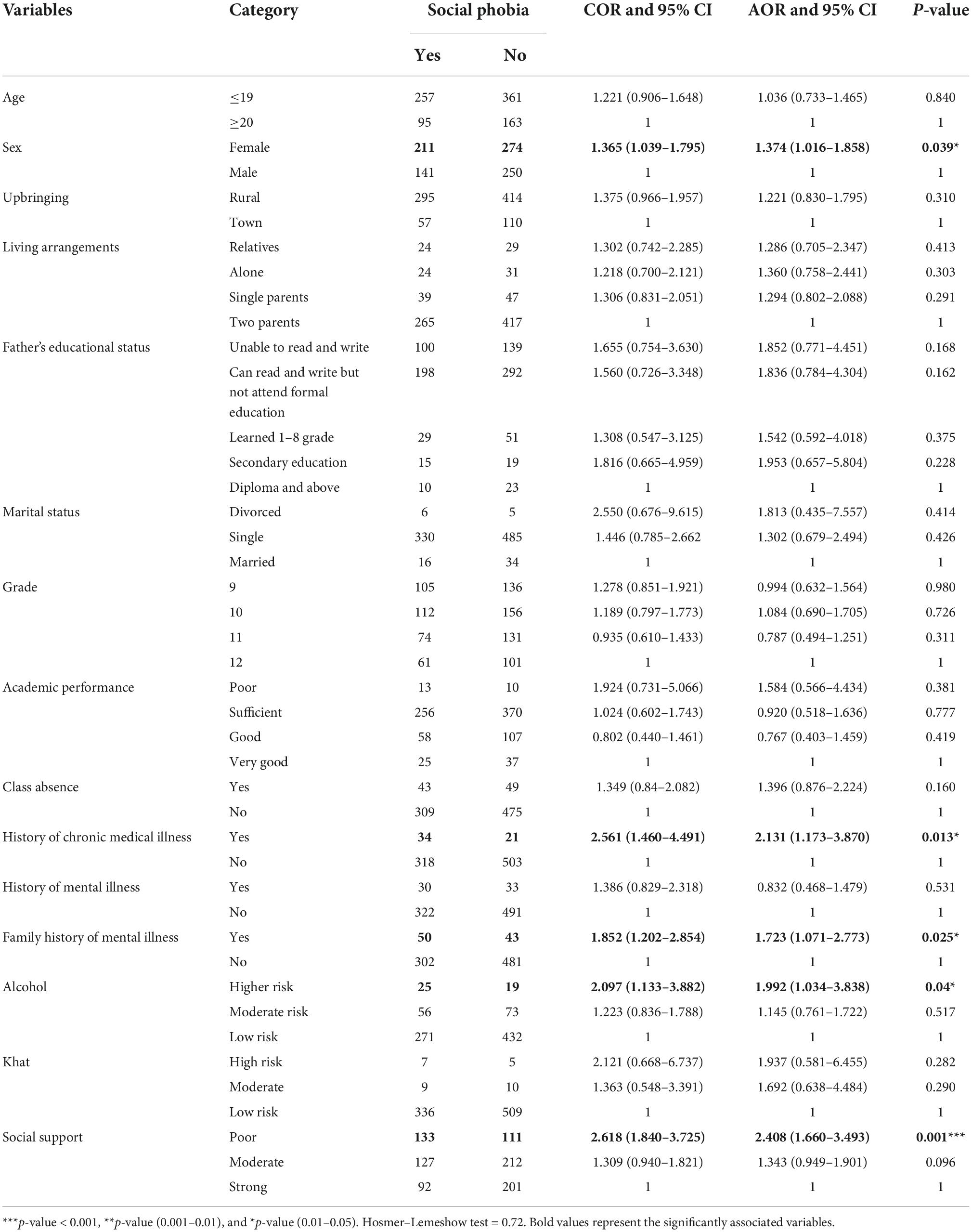

On average, individuals with higher levels of social anxiety spent significantly less time in the company of close companions ( r = −.16, p = .01) and showed a trend to spend more time alone ( r = .13, p = .06), as in prior work ( Afram and Kashdan 2015 , Alden and Taylor 2004 ). A mediation analysis suggested that this reflects reduced access to close companions. As shown in Figure 3 , individuals with higher levels of social anxiety report fewer confidants ( a = −.19, p = .005), consistent with prior work ( Davidson et al. 1994 , Montgomery et al. 1991 , La Greca and Lopez 1998 ). Individuals with fewer confidants were, in turn, less likely to be in the presence of close companions ( b = .31, p < .001) at the time of momentary assessment 4 . Bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effect excluded zero, indicating significant mediation. Likewise, the direct effect of social anxiety on the amount of time spent with close companions was no longer significant after accounting for variation in the number of confidants ( c ’ path in Figure 3 ; p > .10). 5 Notably, social anxiety was not significantly related to the amount of time spent with distant companions ( p = .20), contraindicating a general bias to avoid others. The association between social anxiety and the amount of time allocated to close companions was significantly stronger than that with distant companions, t Hotelling = 2.18, p = .03.

Figure depicts significant mediation models for the amount of time allocated to close companions. Path labels indicate standardized regression coefficients, with c’ indicating the coefficient while controlling for variation in the self-reported number of confidants. Socially anxious individuals report fewer confidants, and individuals with fewer confidants were, in turn, less likely to be in the presence of close companions at the time of momentary assessment.

Social Anxiety is Associated with Diminished Real-World Emotional Experience

MLM analyses demonstrated that social anxiety is associated with reduced quality of real-world emotional experience. Individuals with higher levels of social anxiety report significantly increased NA ( t = 25.2, b = .12, SE = .005, p < .001) and reduced PA ( t = −24.1, b = −.19, SE = .008, p < .001), consistent with past research ( Kashdan 2004 , Kashdan et al. 2013a , Kashdan et al. 2013b , Kashdan and Steger 2006 ) 6 .

The Quality of Momentary Emotional Experience Covaries with the Presence of Close Companions

Relative to seclusion or the presence of distant others, MLM results showed that close companions are associated with lower levels of NA (Alone: t = −.7.51, b = −.09, SE = .012, p < .001; Distant: t = −6.71, b = −.10, SE = .015, p < .001) and higher levels of PA (Alone: t = 15.79, b = .31, SE = .019, p < .001; Distant: t = 15.03, b = .37, SE = .025, p <.001). Relative to seclusion, distant companions are associated with lower levels of PA (PA: t = −2.59, b = −.06, SE = .024, p = .01; NA: p > .30). Results were similar when controlling for variation in the amount of time allocated to different social contexts ( Supplementary Table S1 ). These findings reinforce the conclusion that the quality of momentary emotional experience is positively associated with the presence of close friends, family, and romantic partners.

Socially Anxious Individuals Derive Larger Emotional Benefits from Close Companions

We next considered the joint impact of social anxiety and social context on momentary mood ( Table 1 ). As shown in Figure 4 , the results of this more comprehensive MLM revealed that socially anxious individuals derive larger emotional benefits—indexed by significantly lower levels of NA—from close companions relative to seclusion (Social Anxiety × Close-Alone, t = −2.27, b = −.03, SE = .012, p = .02). In short, individuals with higher levels of social anxiety tend to experience the least intense, most normative levels of NA in the company of friends, family, and romantic partners. This effect remained significant after controlling for the amount of time allocated to different social contexts ( Supplementary Table S2 ) 7 . Other interactions were not significant for NA or PA ( p > .80). That is, social anxiety was not associated with an exaggerated emotional response in the presence of co-workers, strangers, and other distant companions ( Figure 4 and Table 1 ). The same general pattern of results was evident for analyses focused on the anxious and depressed facets of momentary NA ( Supplementary Tables S3 – S4 ).

The deleterious impact of social anxiety on momentary emotional experience critically depends on social context. Individuals with higher levels of social anxiety derive larger emotional benefits—larger decrements in negative affect (NA)—from close companions relative to being alone ( left side of display ). Hypothesis testing relied on a continuous measure of social anxiety. For illustrative purposes, predicted values derived from multilevel modeling are depicted for extreme levels (±1 SD) of social anxiety. Abbreviation—SA: Social anxiety.

The Impact of Social Anxiety and Social Context on Momentary Emotional Experience

| NA | PA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Anxiety | 5.81 | .13 | −4.72 | −.19 |

| Close vs. Alone | −7.56 | −.09 | 15.72 | .31 |

| Distant vs. Alone | .98 | .01 | −2.57 | −.06 |

| Social Anxiety × Close vs. Alone | −2.27 | −.03 | −.13 | −.00 |

| Social Anxiety × Distant vs. Alone | −1.91 | −.02 | .09 | .00 |

Social anxiety lies on a continuum, from mild to debilitating, and young adults with elevated symptoms of social anxiety are more likely to show significant impairment and develop frank psychopathology. The present study provides new insights into the ways in which real-world emotional experience varies as a function of social anxiety and the social environment. Our results demonstrate that the presence of close companions is associated with lower levels of momentary NA ( Figure 4 ), including anxiety and depression. Importantly, individuals with higher levels of social anxiety were found to spend significantly less time with close companions and a mediation analysis suggested that this association is partially explained by smaller confidant networks ( Figure 3 ). Social anxiety was unrelated to the number of assessments completed in the presence of co-workers, strangers, and other distant companions, contraindicating a general social avoidance bias. Although social anxiety was prospectively associated with a diminished quality of momentary emotional experience (i.e., increased NA and reduced PA), MLM analyses demonstrated that individuals with higher levels of social anxiety derive significantly larger benefits—manifesting as lower levels of NA, anxiety, and depression—from the company of close companions ( Figure 4 ). In contrast, socially anxious individuals were not disproportionately sensitive to the presence of distant companions ( Table 1 and Figure 4 ). Indeed, they showed similarly high levels of NA when they were alone. Although social anxiety research and treatment has predominantly focused on responses to novelty and potential threat, our results underscore the centrality of friends, family, and romantic partners. These findings provide a framework for understanding the deleterious consequences of extreme social anxiety and guiding the development of improved intervention strategies.

The present findings extend developmental and laboratory research highlighting the importance of social and interpersonal processes for emotion regulation and mental wellbeing ( Coan and Sbarra 2015 , Zaki and Williams 2013 , Reeck et al. 2016 , Maresh et al. 2013 , Rubin et al. 2018 ). Our observations motivate the hypothesis that the pervasive NA characteristic of socially anxious young adults partially reflects difficulties forming or maintaining close relationships, consistent with work focused on children and adolescents at risk for developing social anxiety disorder ( Shackman et al. 2016 , Markovic and Bowker 2017 , Rubin et al. 2018 , Frenkel et al. 2015 , Ladd et al. 2011 ). With fewer confidants, socially anxious individuals spend significantly less time with close companions and are less frequent beneficiaries of their mood-enhancing effects ( Figures 3 – 4 ). Socially anxious individuals appear to have an intact capacity for social mood enhancement. Indeed, they show lower levels of NA in the company of close companions, in broad accord with work focused on depressed samples ( Rottenberg 2017 ). This model is well aligned with evidence from prospective longitudinal studies which indicate that close friendships and other kinds of social support and intimacy reduce the risk of developing anxiety symptoms in adolescence and early adulthood ( Narr et al. 2019 , Frenkel et al. 2015 , Tillfors et al. 2012 , Teachman and Allen 2007 , Rodebaugh 2009 ). Likewise, among patients undergoing treatment for social anxiety, higher levels of perceived social support are associated with a more favorable prognosis ( Rapee et al. 2015 ).

Naturally, our results do not license causal inferences. We cannot rule out the possibility that reduced access to confidants begets higher levels of social anxiety or, more likely, that these two constructs exert bi-directional effects ( Rubin et al. 2018 ). Likewise, it could be that socially anxious individuals actively seek out the company of close companions when they are experiencing lower levels of NA. Nevertheless, randomized laboratory studies reinforce the conclusion that close companions play a key role in mitigating NA. For example, the presence of a close companion has been shown to normalize negative affect and catastrophic cognitions ( ‘I’m going to die’ ) in anxiety patients exposed to a panic-inducing CO 2 challenge ( Carter et al. 1995 ) and to normalize behavioral signs of anxiety in socially anxious young adults during a videotaped speech challenge ( Pontari 2009 ). Taken with the present results, these observations motivate the hypothesis that friends, romantic partners, and family members serve as a regulatory ‘prosthesis’ for socially anxious individuals.

Relying on close companions is risky. This is particularly true for socially anxious individuals, who tend to experience elevated levels of interpersonal conflict ( Cuming and Rapee 2010 ) and, among patients, profound impairment of interpersonal relationships ( Wittchen et al. 2000 , Rapaport et al. 2005 , Olatunji et al. 2007 , Stein et al. 2017 ). Relationship distress and dissolution reduces or eliminates the possibility of interpersonal emotion regulation and, ultimately, can contribute to the development, maintenance, and recurrence of psychopathology ( Baucom et al. 2014 , Whisman and Baucom 2012 , Rehman et al. 2008 , Marroquin 2011 ). Even in the absence of relationship problems, as young adults transition to full-time employment, marriage, and parenting, social network size begins to decline and more time is spent with distant companions or alone ( Wrzus et al. 2016 , Wrzus et al. 2013 , R. W. Larson 1990 , Sander et al. 2017 , Lansford et al. 1998 )—effects that may be amplified in more recent cohorts, which tend to allocate less time to face-to-face social interaction and experience elevated levels of loneliness ( Twenge et al. 2019 ). Many middle-aged and older adults report that they have no confidant ( McPherson and Smith-Lovin 2006 ), depriving them of the emotional benefits of close companions. This is likely to be exacerbated among individuals with elevated levels of social anxiety, who are less likely to have close friends and more likely to be unmarried by mid-life ( Davidson et al. 1994 , Montgomery et al. 1991 , La Greca and Lopez 1998 ). Extending the present approach to earlier and later developmental periods is an important challenge for future research, and prospective-longitudinal studies are likely to be especially fruitful.

Social anxiety is often cast as an increased sensitivity to scrutiny from others, especially unfamiliar others, which manifests as heightened avoidance, fear (‘phobia’), and anxiety ( American Psychiatric Association 2013 ). The present results underscore the need to broaden this perspective. As indexed by EMA, social anxiety was unrelated to the amount of time spent with distant companions. Moreover, socially anxious individuals did not experience heightened NA in the presence of distant companions ( Table 1 and Figure 4 ). This suggests that, in the absence of clear signs of rejection, scrutiny, or threat, socially anxious individuals tend to show normative emotional responses to distant companions. Another possibility is that hyper-reactivity to strangers is specific to pathological levels of social anxiety or is only evident in a subset of socially anxious individuals. Adjudicating between these accounts represents another important avenue for future research.

From a clinical perspective, these observations suggest that naturally occurring social relationships are a potentially important target for intervention. Existing treatments for social anxiety typically focus on the individual, but our results highlight the value of simultaneously considering the role of close companions and developing supplementary interventions to enhance social connection, acceptance, and support. This could take the form of nurturing social-cognitive skills (e.g., emotional disclosure), cultivating stronger and more frequent ties with existing companions and social networks (e.g., via behavioral activation approaches), or reducing maladaptive thoughts and behaviors (e.g., neediness, overreliance) that promote conflict and rejection ( Masi et al. 2011 , Cacioppo et al. 2015 , Kok and Singer 2017 ). The development of smartphone-based interventions would provide a scalable and cost-effective alternative to more traditional modalities—already, 77% of U.S. adults, and 94% of U.S. adults aged 18–29 own a smartphone ( Pew Research Center 2018 ). Mobile applications may be especially effective for individuals who are unable or unwilling to use traditional care delivery systems and for subclinical presentations of social anxiety that do not warrant resource-intensive treatments ( Ruscio 2019 ). Regardless of delivery method, intervention research would also provide a crucial opportunity for testing the causal contribution of close companions to the everyday experience of social anxiety.

Our results highlight some additional avenues for future research. To understand the generalizability of our inferences, it will be useful to extend the present approach to larger and more representative samples and to populations with more severe symptoms, distress, and impairment. Future EMA studies may benefit from using larger sampling windows or selectively targeting periods of increased stress or disrupted social intimacy (e.g., transition from high school or university, or from university to full-time work) in order to capture a wider range of social interactions and their association with momentary affect. It will also be helpful to examine the nature and quality of naturalistic social interactions—including momentary perceptions of social connection, emotional support, and conflict—in more detail using either EMA (e.g., context- or event-triggered) or behavioral observations. Developing a clearer understanding of the processes that promote heightened levels of NA during periods of solitude—when both social support and social threat are absent ( Figure 4 )—is also likely to be fruitful ( Shackman et al. 2016 ).

In sum, the present study suggests that close companions play an important role in the momentary experience of socially anxious young adults. The use of well-established techniques for intensive EMA and a relatively large sample selectively recruited from a pool of more than 6,000 young adults increases our confidence in the reproducibility and translational relevance of these findings. These results set the stage for developing improved strategies for treating or preventing the sequelae of extreme social anxiety.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements.

The authors acknowledge the assistance of C. Garbin, L. Friedman, R. Tillman, and members of the Affective and Translational Neuroscience laboratory and constructive feedback from four anonymous reviewers and K. Rubin. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (DA040717, MH107444) and University of Maryland. Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

DATA SHARING

Raw data have been or will be made available via the National Institute of Mental Health’s RDoC Database ( https://data-archive.nimh.nih.gov/rdocdb ).

1. The mean and dispersion of the present sample is similar to that of unselected individuals drawn from the same university population. For example, exploratory analyses of data collected as part of the University of Maryland Department of Psychology’s on-line survey during the 2015–2018 academic years ( N = 1,596) revealed that among the subset of respondents 18–19 years old, women reported significantly greater social anxiety ( N = 601, M = 46.8, SD = 23.2) than men ( N = 229, M = 40.3, SD = 22.7), t = 3.67, p = .001. When the on-line survey data were adjusted to reflect the percentage of women in the EMA study (51.3%), the resulting weighted distribution ( M = 43.6, Range = 2–122) was similar to the present EMA sample ( M = 41.7, Range = 1–121).

2. For descriptive purposes, depression was assessed using the General Depression subscale of the revised Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS-II) Watson, D., O’Hara, M. W., Naragon-Gainey, K., Koffel, E., Chmielewski, M., Kotov, R., Stasik, S. M. and Ruggero, C. J. (2012) ‘Development and validation of new anxiety and bipolar symptom scales for an expanded version of the IDAS (the IDAS-II)’, Assessment, 19, 399–420.. As expected, levels of depression were somewhat elevated in the present sample ( M = 39.9, SD = 12.8), which corresponds to the 60 th percentile in U.S. normative data Nelson, G. H., O’Hara, M. W. and Watson, D. (2018) ‘National norms for the expanded version of the inventory of depression and anxiety symptoms (IDAS-II)’, J Clin Psychol, 74, 953–968..

3. Similar results were obtained for the model using the log-transformed NA scores as a DV (not reported).

4. The zero-order correlation between self-reported social network size and the proportion of momentary assessments completed in the presence of close companions was r = .29, p < .001.

5. Although the complementary pattern ( elevated social anxiety → fewer confidants → greater solitude ) was evident for a model focused on time spent alone, we refrain from reporting or interpreting it, given the strong dependency between time allocated to close companions vs. solitude. That is, social contexts were mutually exclusive ( Figure 2 ), and most assessments were completed either in the presence of close companions or alone. From this perspective, the results of the ‘alone’ model are almost entirely predictable knowing the results of the ‘close companions’ model.

6. Momentary NA and PA were negatively correlated within momentary assessments ( t = −18.7, b = −.26, SE = .014, p < .001).

7. It also remained significant when controlling for variation in depressive symptoms, indexed using the General Depression subscale of the IDAS-II (Social Anxiety × Close-Alone, t = −2.28, b = −.03, SE = .012, p = .02).

- Acarturk C, Cuijpers P, Van Straten A and De Graaf R (2009) ‘ Psychological treatment of social anxiety disorder: a meta-analysis ’, Psychol Med , 39 ( 2 ), 241–254. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Afram A and Kashdan TB (2015) ‘ Coping with rejection concerns in romantic relationships: An experimental investigation of social anxiety and risk regulation ’, Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science , 4 ( 3 ), 151–156. [ Google Scholar ]

- Alden LE and Taylor CT (2004) ‘ Interpersonal processes in social phobia ’, Clin Psychol Rev , 24 ( 7 ), 857–882. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alden LE and Wallace ST (1995) ‘ Social phobia and social appraisal in successful and unsuccessful social interactions ’, Behaviour Research and Therapy , 33 ( 5 ), 497–505. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alloy LB and Abramson LY (1999) ‘ The Temple-Wisconsin Cognitive Vulnerability to Depression Project: Conceptual background, design, and methods ’, Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy , 13 , 227–62. [ Google Scholar ]

- American College Health Association (2016) American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group Executive Summary Fall 2015 Hanover, MD: American College Health Association. [ Google Scholar ]

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) , Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson ER and Hope DA (2008) ‘ A review of the tripartite model for understanding the link between anxiety and depression in youth ’, Clin Psychol Rev , 28 ( 2 ), 275–287. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- APA (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®) , American Psychiatric Pub. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Arnett JJ (2000) ‘ Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties ’, Am Psychol , 55 , 469–80. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Auerbach RP, Alonso J, Axinn WG, Cuijpers P, Ebert DD, Green JG, Hwang I, Kessler RC, Liu H, Mortier P, Nock MK, Pinder-Amaker S, Sampson NA, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, Andrade LH, Benjet C, Caldas-de-Almeida JM, Demyttenaere K, Florescu S, de Girolamo G, Gureje O, Haro JM, Karam EG, Kiejna A, Kovess-Masfety V, Lee S, McGrath JJ, O’Neill S, Pennell BE, Scott K, Ten Have M, Torres Y, Zaslavsky AM, Zarkov Z and Bruffaerts R (2016) ‘ Mental disorders among college students in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys ’, Psychol Med , 46 , 1–16. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Auerbach RP, Mortier P, Bruffaerts R, Alonso J, Benjet C, Cuijpers P, Demyttenaere K, Ebert DD, Green JG, Hasking P, Murray E, Nock MK, Pinder-Amaker S, Sampson NA, Stein DJ, Vilagut G, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC and Collaborators WW-I (in press) ‘ WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders ’, J Abnorm Psychol . [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barrett LF (1997) ‘ The relationships among momentary emotion experiences, personality descriptions, and retrospective ratings of emotion ’, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 23 ( 10 ), 1100–1110. [ Google Scholar ]

- Batelaan NM, Bosman RC, Muntingh A, Scholten WD, Huijbregts KM and van Balkom A (2017) ‘ Risk of relapse after antidepressant discontinuation in anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis of relapse prevention trials ’, BMJ , 358 , j3927. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baucom DH, Belus JM, Adelman CB, Fischer MS and Paprocki C (2014) ‘ Couple-based interventions for psychopathology: a renewed direction for the field ’, Fam Process , 53 , 445–61. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck JG, Davila J, Farrow S and Grant D (2006) ‘ When the heat is on: Romantic partner responses influence distress in socially anxious women ’, Behaviour Research and Therapy , 44 ( 5 ), 737–748. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beidel DC, Turner SM and Morris TL (1999) ‘ Psychopathology of childhood social phobia ’, Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry , 38 ( 6 ), 643–650. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berry DS and Hansen JS (1996) ‘ Positive affect, negative affect, and social interaction ’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 71 ( 4 ), 796. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bolger N and Eckenrode J (1991) ‘ Social relationships, personality, and anxiety during a major stressful event ’, J Pers Soc Psychol , 61 , 440–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Boukhechba M, Chow P, Fua K, Teachman BA and Barnes LE (2018) ‘ Predicting Social Anxiety From Global Positioning System Traces of College Students: Feasibility Study ’, JMIR mental health , 5 ( 3 ). [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bruce SE, Yonkers KA, Otto MW, Eisen JL, Weisberg RB, Pagano M, Shea MT and Keller MB (2005) ‘ Influence of psychiatric comorbidity on recovery and recurrence in generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and panic disorder: a 12-year prospective study ’, Am J Psychiatry , 162 , 1179–87. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bullock JG, Green DP and Ha SE (2010) ‘ Yes, but what’s the mechanism? (don’t expect an easy answer) ’, J Pers Soc Psychol , 98 , 550–8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Buote VM, Pancer SM, Pratt MW, Adams G, Birnie-Lefcovitch S, Polivy J and Wintre MG (2007) ‘ The importance of friends. Friendship and adjustment among 1st-year university students ’, Journal of Adolescent Research , 22 , 665–89. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cacioppo S, Grippo AJ, London S, Goossens L and Cacioppo JT (2015) ‘ Loneliness: clinical import and interventions ’, Perspect Psychol Sci , 10 , 238–49. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carter MM, Hollon SD, Carson RE and Shelton RC (1995) ‘ Effects of a safe person on induced distress following a biological challenge in panic disorder with agoraphobia ’, Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 104 , 156–63. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chow PI, Fua K, Huang Y, Bonelli W, Xiong H, Barnes LE and Teachman BA (2017) ‘ Using mobile sensing to test clinical models of depression, social anxiety, state affect, and social isolation among college students ’, Journal of medical Internet research , 19 ( 3 ). [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Coan JA and Sbarra DA (2015) ‘ Social baseline theory: The social regulation of risk and effort ’, Curr Opin Psychol , 1 , 87–91. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Coles ME, Turk CL and Heimberg RG (2002) ‘ The role of memory perspective in social phobia: Immediate and delayed memories for role-played situations ’, Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy , 30 ( 4 ), 415–425. [ Google Scholar ]

- Conway CC, Forbes MK, Forbush KT, Fried EI, Hallquist MN, Kotov R, Mullins-Sweatt SN, Shackman AJ, Skodol AE, South SC, Sunderland M, Waszczuk MA, Zald DH, Afzali MH, Bornovalova MA, Carragher N, Docherty AR, Jonas KG, Krueger RF, Patalay P, Pincus AL, Tackett JL, Reininghaus U, Waldman ID, Wright AGC, Zimmerman J, Bach B, Bagby RM, Chmielewski M, Cicero DC, Clark LA, Dalgleish T, DeYoung CG, Hopwood CJ, Ivanova MY, Latzman RD, Patrick CJ, Ruggero CJ, Samuel DB, Watson D and Eaton NR (2019) ‘ A Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology can reform mental health research ’, Perspectives on psychological science , 14 , 419–436. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cottrell NB and Epley SW (1977) ‘Affiliation, social comparison, and socially mediated stress reduction’ in Suls JM and Miller RL, eds., Social comparison processes: Theoretical and empirical perspectives , Washington, DC: Hemisphere, 43–68. [ Google Scholar ]

- Craske MG, Stein MB, Eley TC, Milad MR, Holmes A, Rapee RM and Wittchen H-U (2017) ‘ Anxiety disorders ’, Nature Reviews Disease Primers , 3 , 17024. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Creed A and Funder D (1998) ‘ Social anxiety: From the inside and outside ’, Personality and Individual Differences , 25 ( 1 ), 19–33. [ Google Scholar ]

- Crişan LG, Vulturar R, Miclea M and Miu AC (2016) ‘ reactivity to social stress in subclinical social anxiety: emotional experience, cognitive appraisals, Behavior, and Physiology ’, Front Psychiatry , 7 , 5. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Csikszentmihalyi M, Mehl MR and Conner TS (2013) Handbook of research methods for studying daily life , New York, NY: Guilford. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cuming S and Rapee RM (2010) ‘ Social anxiety and self-protective communication style in close relationships ’, Behaviour Research and Therapy , 48 ( 2 ), 87–96. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Darcy K, Davila J and Beck JG (2005) ‘ Is social anxiety associated with both interpersonal avoidance and interpersonal dependence? ’, Cognit Ther Res , 29 ( 2 ), 171–186. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davidson JR, Hughes DC, George LK and Blazer DG (1994) ‘ The boundary of social phobia: Exploring the threshold ’, Archives of General Psychiatry , 51 ( 12 ), 975–983. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davila J and Beck JG (2002) ‘ Is social anxiety associated with impairment in close relationships? A preliminary investigation ’, Behav Ther , 33 ( 3 ), 427–446. [ Google Scholar ]

- Diener E and Seligman ME (2002) ‘ Very happy people ’, Psychol Sci , 13 , 81–4. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Diener E, Seligman MEP, Choi H and Oishi S (2018) ‘ Happiest People Revisited ’, Perspect Psychol Sci , 13 , 176–184. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fox AS and Shackman AJ (2018) ‘How are emotions embodied in the social world’ in Fox AS, Lapate RC, Shackman AJ and Davidson RJ, eds., The nature of emotion. Fundamental questions , 2nd ed., New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 237–239. [ Google Scholar ]

- Freberg K, Adams R, McGaughey K and Freberg L (2010) ‘ The rich get richer: Online and offline social connectivity predicts subjective loneliness ’, Media Psychology Review , 3 , n.p. [ Google Scholar ]

- Frenkel TI, Fox NA, Pine DS, Walker OL, Degnan KA and Chronis-Tuscano A (2015) ‘ Early childhood behavioral inhibition, adult psychopathology and the buffering effects of adolescent social networks: a twenty-year prospective study ’, J Child Psychol Psychiatry , 56 , 1065–73. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Geyer EC, Fua KC, Daniel KE, Chow PI, Bonelli W, Huang Y, Barnes LE and Teachman BA (2018) ‘ I Did OK, but Did I Like It? Using Ecological Momentary Assessment to Examine Perceptions of Social Interactions Associated With Severity of Social Anxiety and Depression ’, Behav Ther . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborators (2016) ‘ Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 ’, Lancet , 388 , 1545–1602. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gordon JA and Redish AD (2016) ‘On the cusp. Current challenges and promises in psychiatry’ in Redish AD and Gordon JA, eds., Computational psychiatry: New perspectives on mental illness , Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 3–14. [ Google Scholar ]

- Granovetter MS (1973) ‘ The strength of weak ties ’, American Journal of Sociology , 78 , 1360–1380. [ Google Scholar ]

- Green DP, Ha SE and Bullock JG (2010) ‘ Enough already about “black box” experiments: Studying mediation is more difficult than most scholars suppose ’, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science , 628 , 200–208. [ Google Scholar ]

- Grosse Rueschkamp JM, Kuppens P, Riediger M, Blanke ES and Brose A (in press) ‘ Higher well-being is related to reduced affective reactivity to positive events in daily life ’, Emotion . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hayes AF (2017) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach , 2nd ed, New York, NY: Guilford. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hays RB and Oxley D (1986) ‘ Social network development and functioning during a life transition ’, J Pers Soc Psychol , 50 , 305–13. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Heerey EA and Kring AM (2007) ‘ Interpersonal consequences of social anxiety ’, Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 116 ( 1 ), 125. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Heimberg RG, Hofmann SG, Liebowitz MR, Schneier FR, Smits JA, Stein MB, Hinton DE and Craske MG (2014) ‘ Social anxiety disorder in DSM‐5 ’, Depression and Anxiety , 31 ( 6 ), 472–479. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hofmann W and Patel PV (2015) ‘ SurveySignal: A convenient solution for experience sampling research using participants’ own smartphones ’, Social Science Computer Review , 33 ( 2 ), 235–253. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hur J, Stockbridge MD, Fox AS and Shackman AJ (in press) ‘ Dispositional negativity, cognition, and anxiety disorders: An integrative translational neuroscience framework ’, Progress in brain research . [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kashdan TB (2004) ‘ The neglected relationship between social interaction anxiety and hedonic deficits: Differentiation from depressive symptoms ’, J Anxiety Disord , 18 ( 5 ), 719–730. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kashdan TB and Collins RL (2010) ‘ Social anxiety and the experience of positive emotion and anger in everyday life: An ecological momentary assessment approach ’, Anxiety, Stress, & Coping , 23 ( 3 ), 259–272. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kashdan TB, Farmer AS, Adams LM, Ferssizidis P, McKnight PE and Nezlek JB (2013a) ‘ Distinguishing healthy adults from people with social anxiety disorder: Evidence for the value of experiential avoidance and positive emotions in everyday social interactions ’, Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 122 ( 3 ), 645. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kashdan TB, Ferssizidis P, Farmer AS, Adams LM and McKnight PE (2013b) ‘ Failure to capitalize on sharing good news with romantic partners: Exploring positivity deficits of socially anxious people with self-reports, partner-reports, and behavioral observations ’, Behaviour Research and Therapy , 51 ( 10 ), 656–668. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kashdan TB and Roberts JE (2004) ‘ Social anxiety’s impact on affect, curiosity, and social self-efficacy during a high self-focus social threat situation ’, Cognit Ther Res , 28 ( 1 ), 119–141. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kashdan TB and Roberts JE (2006) ‘ Affective outcomes in superficial and intimate interactions: Roles of social anxiety and curiosity ’, Journal of Research in Personality , 40 ( 2 ), 140–167. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kashdan TB and Roberts JE (2007) ‘ Social anxiety, depressive symptoms, and post-event rumination: Affective consequences and social contextual influences ’, J Anxiety Disord , 21 ( 3 ), 284–301. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kashdan TB and Steger MF (2006) ‘ Expanding the topography of social anxiety: An experience-sampling assessment of positive emotions, positive events, and emotion suppression ’, Psychol Sci , 17 ( 2 ), 120–128. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kashdan TB, Weeks JW and Savostyanova AA (2011) ‘ Whether, how, and when social anxiety shapes positive experiences and events: A self-regulatory framework and treatment implications ’, Clin Psychol Rev , 31 ( 5 ), 786–799. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Katzelnick DJ, Kobak KA, DeLeire T, Henk HJ, Greist JH, Davidson JR, Schneier FR, Stein MB and Helstad CP (2001) ‘ Impact of generalized social anxiety disorder in managed care ’, Am J Psychiatry , 158 , 1999–2007. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kendler KS and Gardner CO (2014) ‘ Sex differences in the pathways to major depression: a study of opposite-sex twin pairs ’, Am J Psychiatry , 171 , 426–35. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kendler KS, Myers J and Prescott CA (2005) ‘ Sex differences in the relationship between social support and risk for major depression: a longitudinal study of opposite-sex twin pairs ’, American Journal of Psychiatry , 162 ( 2 ), 250–256. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kessler RC (2003) ‘ The impairments caused by social phobia in the general population: implications for intervention ’, Acta Psychiatr Scand , 108 ( Suppl. 417 ), 19–27. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kocalevent RD, Berg L, Beutel ME, Hinz A, Zenger M, Harter M, Nater U and Brahler E (2018) ‘ Social support in the general population: standardization of the Oslo social support scale (OSSS-3) ’, BMC Psychol , 6 , 31. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kok BE and Singer T (2017) ‘ Effects of contemplative dyads on engagement and perceived social connectedness over 9 months of mental training: A randomized clinical trial ’, JAMA Psychiatry , 74 , 126–134. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Krueger RF, Kotov R, Watson D, Forbes MK, Eaton NR, Ruggero CJ, Simms LJ, Widiger TA, Achenbach TM, Bach B, Bagby RM, Bornovalova MA, Carpenter WT, Chmielewski M, Cicero D, Clark LA, Conway C, DeClercq B, DeYoung CG, Docherty AR, Drislane LE, First MB, Forbush KT, Hallquist M, Haltigan JD, Hopwood CJ, Ivanova MY, Jonas KG, Latzman RD, Markon KE, Miller JD, Morey LC, Mullins-Sweatt SN, Ormel J, Patalay P, Patrick CJ, Pincus AL, Regier DA, Reininghaus U, Rescorla LA, Samuel DB, Sellbom M, Shackman AJ, Skodol A, Slade T, South SC, Sunderland M, Tackett JL, Venables NC, Waldman ID, Waszczuk MA, Waugh MH, Wright AGC, Zald DH and Zimmerman J (2018) ‘ Progress in achieving empirical classification of psychopathology ’, World Psychiatry , 17 , 282–293. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- La Greca AM and Lopez N (1998) ‘ Social anxiety among adolescents: Linkages with peer relations and friendships ’, Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology , 26 , 83–94. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ladd GW, Kochenderfer-Ladd B, Eggum ND, Kochel KP and McConnell EM (2011) ‘ Characterizing and comparing the friendships of anxious-solitary and unsociable preadolescents ’, Child development , 82 , 1434–53. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lamers F, Swendsen J, Cui L, Husky M, Johns J, Zipunnikov V and Merikangas KR (2018) ‘ Mood reactivity and affective dynamics in mood and anxiety disorders ’, Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 127 ( 7 ), 659. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lansford JE, Sherman AM and Antonucci TC (1998) ‘ Satisfaction with social networks: an examination of socioemotional selectivity theory across cohorts ’, Psychol Aging , 13 , 544–52. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Larson RW (1990) ‘ The solitary side of life: An examination of the time people spend alone from childhood to old age ’, Developmental review , 10 ( 2 ), 155–183. [ Google Scholar ]

- Larson RW (1990) ‘ The solitary side of life: An examination of the time people spend alone from childhood to old age ’, Developmental Review , 1990 ( 10 ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Lay JC, Gerstorf D, Scott SB, Pauly T and Hoppmann CA (2017) ‘ Neuroticism and extraversion magnify discrepancies between retrospective and concurrent affect reports ’, Journal of Personality , 85 ( 6 ), 817–829. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liebowitz MR (1987) ‘ Social phobia’ in Modern Problems in Pharmacopsychiatry , Karger Publishers, 141–173. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lim MH, Rodebaugh TL, Zyphur MJ and Gleeson JF (2016) ‘ Loneliness over time: The crucial role of social anxiety ’, J Abnorm Psychol , 125 ( 5 ), 620–30. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lipsitz JD and Schneier FR (2000) ‘ Social phobia. Epidemiology and cost of illness ’, Pharmacoeconomics , 18 , 23–32. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lipson SK, Lattie EG and Eisenberg D (in press) ‘ Increased rates of mental health service utilization by U.S. college students: 10-Year population-level trends (2007–2017) ’, Psychiatr Serv , appips201800332. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maresh EL, Beckes L and Coan JA (2013) ‘ The social regulation of threat-related attentional disengagement in highly anxious individuals ’, Frontiers in human neuroscience , 7 , 515. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Markovic A and Bowker JC (2017) ‘ Friends also matter: Examining friendship adjustment indices as moderators of anxious-withdrawal and trajectories of change in psychological maladjustment ’, Psychiatr Serv , 53 , 1462–1473. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marroquin B (2011) ‘ Interpersonal emotion regulation as a mechanism of social support in depression ’, Clin Psychol Rev , 31 , 1276–90. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Masi CM, Chen HY, Hawkley LC and Cacioppo JT (2011) ‘ A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness ’, Pers Soc Psychol Rev , 15 , 219–66. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mathew AR, Pettit JW, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR and Roberts RE (2011) ‘ Co-morbidity between major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders: shared etiology or direct causation? ’, Psychol Med , 41 , 2023–34. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McPherson M and Smith-Lovin L (2006) ‘ Social isolation in America: Changes in core discussion networks over two decades ’, Am Sociol Rev , 71 , 353–75. [ Google Scholar ]

- Meleshko KG and Alden LE (1993) ‘ Anxiety and self-disclosure: toward a motivational model ’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 64 ( 6 ), 1000. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Merikangas KR, Avenevoli S, Acharyya S, Zhang H and Angst J (2002) ‘ The spectrum of social phobia in the Zurich cohort study of young adults ’, Biological psychiatry , 51 ( 1 ), 81–91. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Montgomery RL, Haemmerlie FM and Edwards M (1991) ‘ Social, personal, and interpersonal deficits in socially anxious people ’, Journal of Social Behavior and Personality , 6 ( 4 ), 859. [ Google Scholar ]

- Morgan JK, Lee GE, Wright AG, Gilchrist DE, Forbes EE, McMakin DL, Dahl RE, Ladouceur CD, Ryan ND and Silk JS (2017) ‘ Altered positive affect in clinically anxious youth: the role of social context and anxiety subtype ’, J Abnorm Child Psychol , 45 ( 7 ), 1461–1472. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Myers DG (1999) ‘Close relationships and quality of life’ in Kahneman D, Diener E and Schwartz N, eds., Well-being , NY: Sage, 374–391. [ Google Scholar ]

- Narr RK, Allen JP, Tan JS and Loeb EL (2019) ‘ Close friendship strength and broader peer group desirability as differential predictors of adult mental health ’, Child Dev , 90 , 298–313. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nelson GH, O’Hara MW and Watson D (2018) ‘ National norms for the expanded version of the inventory of depression and anxiety symptoms (IDAS-II) ’, J Clin Psychol , 74 , 953–968. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Neubauer K, von Auer M, Murray E, Petermann F, Helbig-Lang S and Gerlach AL (2013) ‘ Internet-delivered attention modification training as a treatment for social phobia: A randomized controlled trial ’, Behaviour Research and Therapy , 51 ( 2 ), 87–97. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oishi S, Diener E and Lucas RE (2007) ‘ The optimum level of well-being: Can people be too happy? ’, Perspect Psychol Sci , 2 , 346–60. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Olatunji BO, Cisler JM and Tolin DF (2007) ‘ Quality of life in the anxiety disorders: a meta-analytic review ’, Clin Psychol Rev , 27 ( 5 ), 572–581. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Palmier‐Claus JE, Myin‐Germeys I, Barkus E, Bentley L, Udachina A, Delespaul P, Lewis SW and Dunn G (2011) ‘ Experience sampling research in individuals with mental illness: reflections and guidance ’, Acta Psychiatr Scand , 123 ( 1 ), 12–20. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pancer SM, Hunsberger B, Pratt MW and Alisat S (2000) ‘ Cognitive complexity of expectations and adjustment to university in the first year ’, Journal of Adolescent Research , 15 , 38–57. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pew Research Center (2018) ‘ Mobile fact sheet ’, [online], available: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/ [accessed

- Phillips ND (2017) ‘ YaRrr! The pirate’s guide to R ’, APS Observer , 30 , 22–23. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pontari BA (2009) ‘ Appearing socially competent: The effects of a friend’s presence on the socially anxious ’, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 35 ( 3 ), 283–294. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ramsey MA and Gentzler AL (2015) ‘ An upward spiral: Bidirectional associations between positive affect and positive aspects of close relationships across the life span ’, Developmental review , 36 , 58–104. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rapaport MH, Clary C, Fayyad R and Endicott J (2005) ‘ Quality-of-life impairment in depressive and anxiety disorders ’, American Journal of Psychiatry , 162 ( 6 ), 1171–1178. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rapee RM, Peters L, Carpenter L and Gaston JE (2015) ‘ The Yin and Yang of support from significant others: Influence of general social support and partner support of avoidance in the context of treatment for social anxiety disorder ’, Behav Res Ther , 69 , 40–7. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rapee RM and Spence SH (2004) ‘ The etiology of social phobia: Empirical evidence and an initial model ’, Clin Psychol Rev , 24 ( 7 ), 737–767. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Raudenbush SW and Bryk AS (2002) Hierarchical linear models. Applications and data analysis methods , 2nd ed, Thousand Oakes, CA: Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Reeck C, Ames DR and Ochsner KN (2016) ‘ The social regulation of emotion: An integrative, cross-disciplinary model ’, Trends Cogn Sci , 20 , 47–63. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rehman US, Gollan J and Mortimer AR (2008) ‘ The marital context of depression: research, limitations, and new directions ’, Clin Psychol Rev , 28 , 179–98. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rhebergen D, Batelaan NM, de Graaf R, Nolen WA, Spijker J, Beekman AT and Penninx BW (2011) ‘ The 7-year course of depression and anxiety in the general population ’, Acta Psychiatr Scand , 123 , 297–306. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rime B (2009) ‘ Emotion elicits the social sharing of emotion: Theory and empirical review ’, Emotion Review , 1 , 60–85. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodebaugh TL (2009) ‘ Social phobia and perceived friendship quality ’, J Anxiety Disord , 23 , 872–8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodebaugh TL, Holaway RM and Heimberg RG (2004) ‘ The treatment of social anxiety disorder ’, Clin Psychol Rev , 24 ( 7 ), 883–908. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodebaugh TL, Lim MH, Shumaker EA, Levinson CA and Thompson T (2015) ‘ Social anxiety and friendship quality over time ’, Cogn Behav Ther , 44 , 502–11. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rogers AA, Updegraff KA, Iida M, Dishion TJ, Doane LD, Corbin WC, Van Lenten SA and Ha T (2018) ‘ Trajectories of positive and negative affect across the transition to college: The role of daily interactions with parents and friends ’, Dev Psychol , 54 , 2181–2192. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rottenberg J (2017) ‘ Emotions in depression: What do we really know? ’, Annu Rev Clin Psychol , 13 , 241–263. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rubin KH, Barstead MG, Smith KA and Bowker JC (2018) ‘Peer relations and the behaviorally inhibited child’ in Pérez-Edgar K and Fox NA, eds., Behavioral inhibition: Integrating theory, research, and clinical perspectives , Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 157–184. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ruscio AM (2019) ‘ Normal versus pathological mood: Implications for diagnosis ’, Annu Rev Clin Psychol , 15 , 179–205. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Russell GS and Shaw S (2009) ‘ A study to investigate the prevalence of social anxiety in a sample of higher education students in the United Kingdom ’, Journal of Mental Health , 18 , 198–206. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sander J, Schupp J and Richter D (2017) ‘ Getting together: Social contact frequency across the life span ’, Dev Psychol , 53 , 1571–1588. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sarason IG, Levine HM, Basham RB and Sarason BR (1983) ‘ Assessing social support: The social support questionnaire ’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 44 , 127–139. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schneier FR, Johnson J, Hornig CD, Liebowitz MR and Weissman MM (1992) ‘ Social phobia: comorbidity and morbidity in an epidemiologic sample ’, Archives of General Psychiatry , 49 ( 4 ), 282–288. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Scholten WD, Batelaan NM, Penninx BW, van Balkom AJ, Smit JH, Schoevers RA and van Oppen P (2016) ‘ Diagnostic instability of recurrence and the impact on recurrence rates in depressive and anxiety disorders ’, J Affect Disord , 195 , 185–90. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Scholten WD, Batelaan NM, van Balkom AJ, Wjh Penninx B, Smit JH and van Oppen P (2013) ‘ Recurrence of anxiety disorders and its predictors ’, J Affect Disord , 147 , 180–5. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shackman AJ, Tromp DPM, Stockbridge MD, Kaplan CM, Tillman RM and Fox AS (2016) ‘ Dispositional negativity: An integrative psychological and neurobiological perspective ’, Psychological bulletin , 142 , 1275–1314. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shackman AJ, Weinstein JS, Hudja SN, Bloomer CD, Barstead MG, Fox AS and Lemay EP Jr. (2018) ‘ Dispositional negativity in the wild: Social environment governs momentary emotional experience ’, Emotion , 18 , 707–724. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA and Hufford MR (2008) ‘ Ecological momentary assessment ’, Annu Rev Clin Psychol , 4 , 1–32. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sparrevohn RM and Rapee RM (2009) ‘ Self-disclosure, emotional expression and intimacy within romantic relationships of people with social phobia ’, Behaviour Research and Therapy , 47 ( 12 ), 1074–1078. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Spinhoven P, Batelaan N, Rhebergen D, van Balkom A, Schoevers R and Penninx BW (2016) ‘ Prediction of 6-yr symptom course trajectories of anxiety disorders by diagnostic, clinical and psychological variables ’, J Anxiety Disord , 44 , 92–101. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Spoozak L, Gotman N, Smith MV, Belanger K and Yonkers KA (2009) ‘ Evaluation of a social support measure that may indicate risk of depression during pregnancy ’, J Affect Disord , 114 ( 1–3 ), 216–223. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]