Careers in Qual

Quick answers, considering a career in research, what attracts people to a career in qualitative research, what do new researchers think of the industry.

What exactly is qualitative research?

How does qualitative research work, as a qualitative researcher, what would i be doing, where do qualitative researchers work, what are the areas of specialisation within qualitative research, what's great about a career in qual, what would my career prospects be in qualitative research, am i suited to a career in qualitative research what skills are needed, what are the entry requirements for qualitative researchers, typical career paths as a qualitative researcher, typical career paths in fieldwork agencies, typical career paths in viewing facilities, other sites with more information about careers in market research.

Qualitative Research Associate

🔍 graduate school of education, stanford, california, united states.

Who We Are:

The Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE) is a top ranked school of education, known for its prestigious faculty, rigorous graduate degree programs, and its impact on the quality of education across the world. The GSE is committed to developing leaders in education research, practice and policy. Our community includes over 60 faculty, 350 students, 200 staff, 14,000 alumni and countless people from the local and global communities making a difference in the field of education. The work is dynamic, fast-paced, and energetic.

What You’ll Bring:

The John Gardner Center in the Graduate School of Education seeks a Qualitative Research Associate to be responsible for conducting qualitative research with an emphasis on policy-relevant and actionable topic areas. The Researcher will lead and contribute to qualitative research: they will assist community partners in formulating research questions and conducting community driven studies resulting in policy briefs and other products focused on topics related to youth development and education. The candidate will also lead and contribute to qualitative research projects, conducting formative assessments of community-based programs, including data collection, coding, analysis and writing reports and briefs. For all research and analyses, the incumbent will present research findings to community partners and other stakeholders on a regular basis. They will supervise graduate level research assistants and potentially some staff; work collaboratively with other Gardner Center staff; and report to the Executive Director.

What You’ll Do:

Work in partnership with community entities to design and conduct policy-relevant research related to youth development in a community setting:

- Collaborate with Gardner Center staff and community partners to identify key research needs in the community and design and carry out research that responds to these.

- Design research projects that respond to community questions and needs using a variety of tools, including the JGC’s Youth Data Archive); youth and adult surveys; secondary data analysis; and qualitative data collection and analyses.

- Conduct primary research and produce written products and presentations that are appropriate for community audiences and parallel materials that inform academic debates and audiences.

Conduct Qualitative Research and Other Analyses:

- Design studies in conjunction with the community and other partners.

- Collect data using a variety of qualitative methods (interviews, focus groups, observations).

- Contribute to data cleaning, verification and documentation.

- Contribute to discussions about coding and analysis schemes. Code data and conduct analyses.

Write, Present and Otherwise Communicate Research Findings to a Wide Range of Stakeholders and Entities:

- Write reports and briefs of findings for partners and broader academic field.

- Write and present academic articles, issue briefs, summaries, conference paper and other products to a variety of audiences.

- Meet with partners on an ongoing basis to review and evolve analyses.

- Work with Gardner Center Communications team on additional communications opportunities for analyses, including newspaper articles, blogs, panel discussions and more.

Participate actively as a collaborative member of the Gardner Center team, and connect the Gardner Center to the greater Stanford community and the broader research field:

- Attend regular staff meetings and retreats.

- Supervise graduate students and junior staff on specific projects.

- Where appropriate, contribute to grant development and report writing.

- Assist the Center in developing processes, tools, and products to enhance the future direction of the Center.

The job duties listed are typical examples of work performed by positions in this job classification and are not designed to contain or be interpreted as a comprehensive inventory of all duties, tasks, and responsibilities. Specific duties and responsibilities may vary depending on department or program needs without changing the general nature and scope of the job or level of responsibility. Employees may also perform other duties as assigned.

To be successful in this position, you will bring :

- Advanced degree and five years of relevant experience in area of specialization or combination of relevant education, training, and/or experience. For jobs with financial responsibilities, experience managing a budget and developing financial plans. Experience developing program partnerships and funding sources.

- Ability to develop program partnerships and funding sources.

- Advanced oral, written, and analytical skills, exhibiting fluency in area of specialization.

- Ability to oversee and direct staff.

- Ability to manage budgets and develop financial plans.

Education and Experience Preferred: A doctorate (or equivalent) in a relevant field (education, public policy, sociology, anthropology, psychology, or related field) is required as is capacity to oversee graduate students as they design, carry out, and write about their research projects.

Experience with qualitative data collection and analysis is required. Demonstrated experience with designing qualitative studies is required, as is proficiency with data analysis software such as NVIVO. Excellent oral, analytic, organizational, and interpersonal skills are required; writing as demonstrated in the candidate’s own writing and publications is essential. Ability to write for multiple audiences, including policy makers and practitioners, is preferred. The candidate must have strong interpersonal and collaboration skills in working with researchers and practitioners as well as organizational skills that demonstrate their ability to handle multiple tasks, timelines and priorities in a team environment. Familiarity with California K-12 education context, and English language learners is preferred. This may be substituted with familiarity with juvenile justice, mental health or foster care systems or a related youth policy issue. Familiarity with school enrichment and youth development programs, such as after-school programs is a plus.

The expected pay range for this position is $113,000 to $120,000 per annum. Stanford University provides pay ranges representing its good faith estimate of what the university reasonably expects to pay for a position. The pay offered to a selected candidate will be determined based on factors such as (but not limited to) the scope and responsibilities of the position, the qualifications of the selected candidate, departmental budget availability, internal equity, geographic location and external market pay for comparable jobs.

At Stanford University, base pay represents only one aspect of the comprehensive rewards package. The Cardinal at Work website ( https://cardinalatwork.stanford.edu/benefits-rewards ) provides detailed information on Stanford’s extensive range of benefits and rewards offered to employees. Specifics about the rewards package for this position may be discussed during the hiring process.

Why Stanford is for You

We provide market competitive salaries, excellent health care and retirement plans, and a generous vacation policy, including additional time off during our winter closure. Our unique perks align with what matters to you:

- Freedom to grow. As one of the greatest intellectual hubs in the world, take advantage of development programs, tuition reimbursement plus $800 you receive annually towards skill-building classes, or audit a Stanford course. Join a TedTalk, film screening, or listen to a renowned author or leader discuss global issues.

- A caring culture. We understand the importance of your personal and family time and provide you access to wellness programs, child-care resources, parent education and consultation, elder care and caregiving support.

- A healthier you. We make wellness a priority by providing access to world-class exercise facilities. Climb our rock wall, or participate in one of hundreds of health or fitness classes.

- Discovery and fun. Stroll through historic sculptures, trails, and museums. Create an avatar and participate in virtual reality adventures or join one with fellow staff on Stanford vacations!

- Enviable resources. We offer free commuter programs and ridesharing incentives. Enjoy discounts for computing, cell phones, outdoor recreation, travel, entertainment, and more! We pride ourselves in being a culture that encourages and empowers you.

How to Apply

The John W. Gardner Center for Youth and Their Communities invites you to apply for this position by clicking on the “Apply Online” link. Please submit an online application, resume, and cover letter.

- Finalist must successfully complete a background check prior to working at Stanford University.

- This is a fixed-term position with an end date of one year and is renewable based on performance and funding.

- Applicants to this position must be available to work in the United States without sponsorship for 2 years or more.

Consistent with obligations under the law, the University will provide reasonable accommodation to any employee with any disability who requires accommodation to perform the essential functions of his or her job.

Stanford is an equal opportunity employment opportunity and affirmative action employer. All qualified applicants will receive consideration for employment without regard to race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, disability, protected veteran status, or another other characteristic protected by law.

- Schedule: Full-time

- Job Code: 4113

- Employee Status: Fixed-Term

- Requisition ID: 100027

- Work Arrangement : Hybrid Eligible

My Submissions

Track your opportunities.

Similar Listings

Graduate School of Education, Stanford, California, United States

📁 Administration

Post Date: 2 days ago

Post Date: Apr 16, 2024

Post Date: Aug 02, 2024

Global Impact We believe in having a global impact

Climate and sustainability.

Stanford's deep commitment to sustainability practices has earned us a Platinum rating and inspired a new school aimed at tackling climate change.

Medical Innovations

Stanford's Innovative Medicines Accelerator is currently focused entirely on helping faculty generate and test new medicines that can slow the spread of COVID-19.

From Google and PayPal to Netflix and Snapchat, Stanford has housed some of the most celebrated innovations in Silicon Valley.

Advancing Education

Through rigorous research, model training programs and partnerships with educators worldwide, Stanford is pursuing equitable, accessible and effective learning for all.

Working Here We believe you matter as much as the work

I love that Stanford is supportive of learning, and as an education institution, that pursuit of knowledge extends to staff members through professional development, wellness, financial planning and staff affinity groups.

School of Engineering

I get to apply my real-world experiences in a setting that welcomes diversity in thinking and offers support in applying new methods. In my short time at Stanford, I've been able to streamline processes that provide better and faster information to our students.

Phillip Cheng

Office of the Vice Provost for Student Affairs

Besides its contributions to science, health, and medicine, Stanford is also the home of pioneers across disciplines. Joining Stanford has been a great way to contribute to our society by supporting emerging leaders.

Denisha Clark

School of Medicine

I like working in a place where ideas matter. Working at Stanford means being part of a vibrant, international culture in addition to getting to do meaningful work.

Office of the President and Provost

Getting Started We believe that you can love your job

Join Stanford in shaping a better tomorrow for your community, humanity and the planet we call home.

- 4.2 Review Ratings

- 81% Recommend to a Friend

View All Jobs

Jobs for Social Research

| < Prev | 1 - 8 of 8 | Next > | Last » |

| Active locations for Social Research |

|---|

| « First | < Prev | 1 - 8 of 8 | Next > | Last » |

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 27 September 2024

Empowerment and integration of refugee women: a transdisciplinary approach

- Maissa Khatib 1 na1 ,

- Tanya Purwar 2 na1 ,

- Rushabh Shah 1 ,

- Maricarmen Vizcaino 1 &

- Luciano Castillo 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 1277 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

- Business and management

- Science, technology and society

Female refugees encounter unique challenges in host societies. These challenges often surpass those faced by male refugees, particularly in accessing the job market and making economic contributions to their new communities. Despite substantial literature on the challenges faced by refugee women, there remains a significant gap in research specifically focused on targeted educational and entrepreneurial interventions for this demographic. Additionally, studies exploring effective integration strategies through such targeted initiatives are notably scarce. This study, motivated by the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, seeks to fill this gap by examining the intersection of gender, immigration status, and climate change adaptation. It evaluates the effectiveness of an educational intervention tailored for refugee women within a transdisciplinary framework incorporating STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, & Math) and social science disciplines. This intervention aims to enhance subjective well-being, particularly by fostering sustainable entrepreneurship, facilitating integration into host societies, and fostering long-term contributions to climate change adaptation and resilience. Employing a mixed-methods approach, the study yields quantitative findings suggesting positive shifts in participants’ overall well-being post-intervention, albeit not reaching statistical significance. Qualitative analysis reveals four central themes: pre-program feelings of isolation and detachment, personal growth, supportive ecosystems, and increased sense of belonging. The qualitative findings serve to complement and enrich our understanding of the intervention’s effectiveness, offering valuable insights that may not be fully captured through quantitative measures alone. From these findings, it is evident that a gender-focused approach is essential for providing tailored integration support. These insights are valuable for policymakers, educators, and stakeholders alike. By recognizing and addressing the specific challenges faced by refugee women during resettlement, this intervention not only facilitates their integration into host societies but also enhances their overall well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Inclusive education of refugee students with disabilities in higher education: a comparative case study

Investigating the effect of vocational education and training on rural women’s empowerment

A convergence research perspective on graduate education for sustainable urban systems science

Introduction.

The global refugee crisis has reached unprecedented levels, with around 110 million individuals forcibly displaced from their homes, including 26 million refugees who have crossed borders and 82 million internally displaced persons (UNHCR 2021 , 2022 ) Footnote 1 . Refugees are individuals who have been forcibly displaced from their home countries due to serious human rights violations and persecution (Duthie, 2011 ), armed conflicts (Bradley, 2017 ), political instability (Lischer, 2017 ), or environmental degradation (Atapattu, 2009 ; Naser, 2011 ), seeking safety outside their borders where their own government fails to protect them (Boswell, 2003 ; Ferwerda and Gest, 2021 ; Parkins, 2010 ; Phillips, 2013 ). Clark ( 2020 ) suggests that mass migration poses intricate and multifaceted challenges for both refugees and the host countries they seek refuge in. The influx of refugees can strain host countries’ limited resources, leading to chronic dependence on governmental assistance, eroding their skills, and hindering their contribution to sustainable development (Irvine and Rome, 2007 ). Moreover, refugees contend with a myriad of challenges encompassing societal, political, and socioeconomic aspects, which impede their ability to establish a satisfactory standard of living within the host society (Mangrio and Sjögren Forss, 2017 ; Segal and Mayadas, 2005 ; Silove et al., 2017 ; Vasey and Manderson, 2012 ).

The challenges persist throughout the journey and continue upon arrival in host countries, where the refugees face additional obstacles to integration and well-being. Their physical well-being is at risk during the arduous journey, as they face dangerous travel conditions, exploitation by human smugglers, or the threat of violence and conflict (Arsenijević et al., 2017 ; Koser, 2011 ). The psychological impact is profound (Kirmayer et al., 2011 ; Li et al., 2016 ; Schweitzer et al., 2006 ). Additionally, refugees often encounter significant barriers in accessing basic necessities such as food, clean water, healthcare, and education in the host countries (McBrien, 2005 ; Morris et al., 2009 ). Connor ( 2010 ) highlights that refugees are educationally disadvantaged compared to other types of immigrants. Regardless of education level and skill set, most refugees face employment challenges in the host society and barriers to inclusion in local economies. The high skilled men and women have limited pathways to get their credentials evaluated and certified. Some research findings from Sweden (Bevelander, 2011 ) and Canada (Picot et al., 2019 ) suggest that even after controlling for various individual characteristics, such as age and education, country-of-origin effects persist and significantly impact the labor market outcomes of refugee men and women. It is also common for host countries to impose additional restrictions on the access of refugees to the labor market (Ruiz and Vargas-Silva, 2017b ; Zetter and Ruaudel, 2016 ). Most theories define successful integration for newcomers, including refugees, as equitable access to opportunities and resources, participation in the community and society, and feelings of security and belonging in their new homes (Ager and Strang, 2008 ; Hynie et al., 2016 ; Phillimore and Goodson, 2008 ; Scott Smith, ( 2008 )). However, despite changes in immigration status and employment, many refugees still feel isolated within their ethnic communities and lack integration into the host society. This lack of social integration is attributed to factors such as limited interaction outside their communities due to job nature or unemployment (Crisp, 2004 ). Language barriers (Kletĕcka-Pulker et al., 2019 ), cultural differences, and legal complexities (Kubal, 2013 ) further compound these challenges, making it difficult for refugees to establish a sense of belonging (Boda et al., 2023 ; Fuchs et al., 2021 ). Moreover, refugees may face discrimination, racism, and social exclusion (Taylor et al., 2004 ), which can further hinder their integration and overall well-being.

The integration of refugees is a multifaceted process. It requires them to adapt to the host society while maintaining their cultural identity, and for host communities to welcome and support them (Phillimore, 2021 ). Recent studies have identified education as a key dimension of refugee integration and social inclusion (Crea and McFarland, 2015 ; Dryden-Peterson, 2022 ; Hek, 2005 ). According to United Nations High Com- missioner for Refugees (UNHCR) Footnote 2 , tertiary education is recognized as a fundamental human right for refugees, contributing to personal development, empowerment, and socioeconomic integration. Along with education, entrepreneurial capacity can facilitate social mobility and effective integration by providing refugees with the skills and opportunities needed to succeed in their new environment (Atasü-Topcuoğlu, 2019 ; Khoudour and Andersson, 2017 ; Meister and Mauer, 2019 ; Shneikat and Alrawadieh, 2019 ; Verme and Schuettler, 2021 ). A study shows that refugees often turn to entrepreneurship, particularly informal ventures for their economic integration and well-being (Zehra and Usmani, 2023 ). Entrepreneurship not only boosts the labor force and drives consumer market demand but also has the potential to enhance productivity and catalyze structural changes in the host society (S. Braun and Kvasnicka, 2014 ; Hornung, 2014 ; Paserman, 2013 ; Peters, 2017 . Meister and Mauer ( 2019 ) study the development of the refugee incubator model through participatory focus group workshops and semi-structured interviews with refugee entrepreneurs and incubator stakeholders. They emphasize the need for a customized incubation model specifically tailored to the needs of refugee entrepreneurs. Furthermore, refugees engaged in entrepreneurial endeavors can spur innovation, leading to the creation of new patents (Moser et al., 2014 ) and the establishment of start-up enterprises (Akgündüz et al., 2018 ; Altındağ et al., 2020 ). Additionally, such initiatives may facilitate trade relations with their countries of origin (Ghosh and Enami, 2015 ; Mayda et al., 2017 ; Mayda et al., 2017 ; Parsons and Vézina, 2018 ) and contribute to sustainable development of the host country. It is essential to underscore the notable scarcity of prior research investigating the role of entrepreneurship in fostering the integration of refugees (Shneikat and Alrawadieh, 2019 ). Specifically, there is a lack of studies focusing on targeted programs that combine elements of education and entrepreneurship within the refugee integration context.

In delving deeper into the existing dearth of initiatives concerning the pivotal roles of education and entrepreneurship in refugee integration, it becomes evident that a crucial dimension has been overlooked: the gender perspective. Young and Chan ( 2015 ) emphasize the historical gender-blindness in refugee research and stress the need to consider gender dynamics to understand the unique challenges faced by both men and women during migration and resettlement. Researchers have noted that recent refugee arrivals tend to be more women than men (Connor, 2010 ). According to the UNHCR ( 2021 , 2022 ) Footnote 3 , 50% of refugees, internally displaced, or stateless populations are women and girls. Liebig and Tronstad ( 2018 ) point that refugee women face a potential “triple disadvantage”, combining challenges related to gender, immigrant status, and forced migration, which may compound or reinforce each other. They face marginalization, sexual exploitation, gender-based violence and, forced and child marriage (Davies and True, 2017 ; Hossain et al., 2021 ; Pittaway and Bartolomei, 2000 ; Roupetz et al., 2020 ) at the origin as well as host country. In general, female refugees face limited autonomy, restricted mobility, and diminished agency, hindering their ability to make decisions about their own lives and well-being (Catolico, 1997 ; McMichael and Manderson, 2004 ; Murphy, 2004 ; Simich et al., 2010 ). Refugee women have lower education levels and fewer basic qualifications compared to other migrant women and refugee men (Liebig and Tronstad, 2018 ). They often come from countries with high gender inequality and low female employment rates which can additionally impact their state in the host country (Ruiz and Vargas-Silva, 2017a ). Additionally, they typically possess lower proficiency in the host-country language during the initial years after arrival (Marshall, 2015 ). Refugee women also face prolonged challenges in entering the labor market compared to refugee men (Dumont et al., 2016 ; Minor and Cameo, 2018 ). Employment rates for refugee women, particularly in countries like Germany, are notably lower, with only 29% employed compared to 57% of men Footnote 4 .

It is noteworthy to mention that despite challenges, refugee women show resilience and a strong determination to rebuild their lives and contribute to their communities (Warriner, 2004 ). In contrast to findings linking refugee status with country-of-origin effects, several studies indicate that refugee women in countries such as Sweden demonstrated higher levels of labor market participation than in their countries of origin (CO-OPERATION, O.-O.F.E., & DEVELOPMENT ( 2015 ); Gutiérrez-Martínez et al., 2021 ; Khoudja and Platt, 2018 ). Customized support measures can reduce obstacles to workforce engagement among refugee women. Research indicates that higher qualifications and mentorship programs lead to increased employment and social networks for these women (Liebig and Tronstad, 2018 ). Many of them are desperate to work and become more educated but do not know how. They understand that employment is key for improving lives for themselves and their families (Glastra and Meerman, 2012 ). According to a recent study (Kabir and Klugman, 2019 ), refugee women have the potential to contribute to $1.4 trillion to the annual global GDP of the top 30 refugee-hosting countries provided all income gender gaps are addressed beforehand. Stempel and Alemi ( 2021 ) highlight a case where empowering female Afghan refugees was key to realizing significant economic growth and sustainable development. These women receive less integration support than their male counterparts; especially with respect to employment-related measures (Cheung et al., 2019 ; Hernes et al., 2019 ). The combination of education and economic support prove to be particularly beneficial for female refugees, highlighting the importance of targeted interventions for this vulnerable population (Young and Chan, 2015 ). Al-Rousan et al. ( 2018 ) emphasize that a scholarship program has a significant positive effect on the overall well-being of female refugee youth, enhancing their feelings of peace, security, and agency. Balaam et al. ( 2022 ) highlight that women value interventions that adopt a community-based befriending or peer support approach, as these approaches cater to a more comprehensive range of women’s needs. Recognizing and addressing their specific needs can help in establishing stronger, more prosperous, and equitable communities while advancing United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs) of promoting livelihoods and economic inclusion for refugees (Cf, 2015 ). The UNSDGs offer a framework to address the social, economic, and environmental challenges faced by refugee women. Emphasizing inclusivity, equity, and targeted support for vulnerable populations, the SDGs are crucial for refugee integration. Specifically, SDG 5 focuses on gender equality, SDG 8 on decent work and economic growth, SDG 10 on reducing inequalities, and SDG 13 on climate action. Integrating these goals allows for a holistic approach to developing interventions that will address the specific needs of refugee women, empowering them to become resilient to climate change, contributing to sustainable development.

While existing literature examines the challenges faced by refugee women during migration and in host societies, there is a significant gap in research on targeted, interdisciplinary interventions to address these issues. Specifically, studies focusing on gender-specific interventions that combine educational and entrepreneurial training to empower refugee women and enhance their integration into the labor market are scarce. To address this gap and align with the UNSDGs (Cf 2015 ) Footnote 5 , the “Building Entrepreneurial Capacity for Refugee Women” (BECRW) program was developed. BECRW was tailored to the needs of the selected refugee women Footnote 6 residing in the southwestern United States (U.S). The specific challenges faced by refugee women in this region include broader community integration, access to education and employment, digital literacy, and language barrier. By situating our study in this context, we aim to provide insights that are both locally relevant and globally applicable (refer to “Institute Framework”, “Intervention Framework”, “Study Population”). This program was conducted over a period of 6 weeks through a virtual platform under the auspices of the Summer Institute for Sustainability and Climate Change (SISCC) in the College of Engineering at Purdue University. BECRW employed STEM and social science disciplines, adopting a transdisciplinary framework. Engineers, researchers, and social scientists collaborated to design a comprehensive and context-specific framework tailored to the unique needs of the refugee women, ensuring a holistic approach to addressing their challenges. Studies (Davaki, 2021 ; Murray et al., 2023 ) highlight the significance of interdisciplinary collaboration between STEM and social science disciplines in addressing complex challenges such as forced migration, climate change, and sustainable development. The aim of the BECRW program was to assist 20 refugee women to personally and professionally advance by providing them with a meticulously curated curriculum that combines elements of research, innovation, sustainability, and entrepreneurship. The objective of this study is to emphasize the non-traditional framework of the program while assessing the effectiveness of the intervention. Employing a mixed methods approach, we investigated the influence of this program on participants’ personal and professional development, state of being, and social inclusion. The following sections of this paper will delve into the design (“Design”), the methods (“Method”), the results (“Results”) and the discussion (“Discussion”) that substantiate the research question and hypothesis regarding the intervention’s effectiveness.

Institute framework

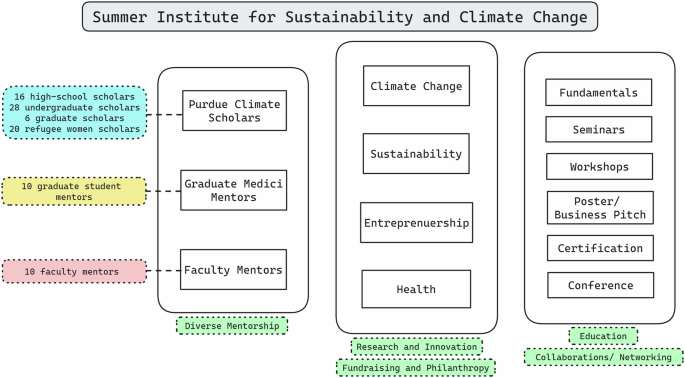

The SISCC, held over a period of six weeks, provided an immersive online learning experience as shown in Fig. 1 . The institute placed a strong emphasis on addressing critical challenges associated with energy & sustainability, climate change & global warming, social inclusion & gender equality, and sustainable entrepreneurship & small business. Its primary goal was to bring together individuals from diverse educational backgrounds and academic stages, creating an inclusive and transdisciplinary community. Participants encompassed high school students, undergraduate and graduate students, and refugee women. Including refugee women in the SISCC was crucial to the goal of the institute. By including refugee women we not only address the specific needs and vulnerabili- ties of this population but also recognize their potential contributions to sustainable development efforts. Refugee women bring unique perspectives, knowledge, and lived experiences that enrich the discourse on climate change adaptation, mitigation, and resilience. The structure of the institute comprised of daily lectures and discussions on the research fundamentals. All participants were given a choice to select a particular research group and projects they were interested in. This provided a valuable platform for knowledge exchange and collaboration. It encouraged interdisciplinary dialog and meaningful connections among participants through a variety of interactive activities. These activities included project-based learning, workshops, seminars, and innovation using various scientific tools, which allowed them to apply their knowledge and skills to real-world scenarios. This structure was established through a diverse mentorship model. Participants received guidance and support from a range of mentors from multiple disciplines and varying academic levels. This included graduate mentors (PhD students and postdocs) and esteemed faculty members from renowned national and international institutions. The Summer Institute also provided opportunities for participants to showcase their work and receive feedback. Poster competition, research presentations and business pitches allowed participants to present their projects and receive valuable input from peers and experts. Additionally, participants were given stipends and reimbursements to support their research and participation.

Overview of the Summer Institute for Sustainability and Climate Change.

An integral part of the SISCC was the conference on Blue Integrated Partnerships and the 2050 Workforce of Tomorrow Footnote 7 . This four-day conference brought together academia, government agencies, and industry leaders to address climate change-related challenges. The conference provided a platform for participants to engage with federal government officials and scholars, learn about the latest advancements in sustainability, and explore potential collaborations with historically black colleges, universities/minority serving institutions (HBCUs/MSIs) and minority-owned companies. The combined design of the Summer Institute and the conference reflected a holistic and comprehensive approach to addressing climate change and sustainability. SISCC framework aligned with multiple United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (Cf 2015 ) Footnote 8 , reflecting its commitment to addressing climate change (Soergel et al., 2021 ), promoting gender equality (Esquivel and Sweetman, 2016 ), providing quality education (Webb et al., 2017 ), fostering innovation (Denoncourt, 2020 ), building sustainable communities (Griggs et al., 2013 ) and fostering partnerships (Hübscher et al., 2022 ) for sustainable development.

Intervention framework

SISCC initiated a collaborative effort merging STEM and social science disciplines, forming a partnership between the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP) and Purdue University. This collaboration resulted in the establishment of the BECRW program, which recruited 20 refugee women. The design of this six weeks long educational and entrepreneurial initiative was tailored to address the specific gender needs identified by these women, shaping every aspect accordingly. The primary aim of the program was to support the personal and professional advancement of refugee women, with a particular focus on entrepreneurship. By emphasizing research, innovation, sustainability, and entrepreneurship, the program sought to enhance the economic capacity of participants, contribute to sustainable development, and improve overall well-being. Recognizing the importance of long-term solutions and economic self-sufficiency, the program aimed to provide opportunities for participants to rebuild their lives, gain independence, and actively contribute to their local communities through entrepreneurship.

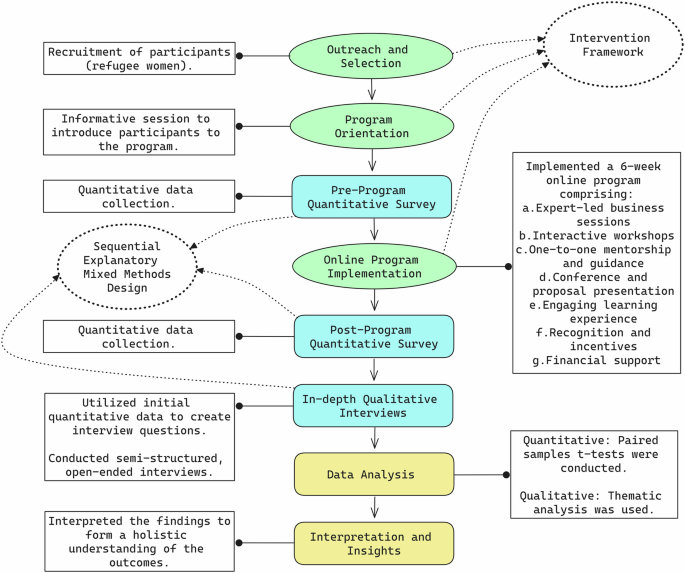

The BECRW program was structured around a comprehensive four-phase framework as shown in Fig. 2 . The first phase centered on recruitment and enrollment. It is important to note that refugee women often fall within the category of “difficult to access” or “hard to reach” populations due to various challenges such as socio-cultural barriers, trauma-related mental health issues, legal obstacles, and stigma (Read and Fenge, 2019 ). In recruiting participants for our study, we utilized a combination of convenience sampling and snowball sampling techniques to engage with diverse groups of refugee women in El Paso, Texas, and Phoenix, Arizona. Convenience sampling allowed us to leverage existing connections with centers supporting refugees and women in both regions, facilitating easy access to potential participants (Spring et al., 2003 ). Our team member, who had established connections with these centers, distributed flyers featuring her contact information to stakeholders and community members frequenting these facilities. This approach ensured that interested refugee women could easily reach out to inquire about the project and determine if they met the inclusion criteria. Additionally, our team member’s affiliation with the Valleywise Refugee Women’s Clinic Footnote 9 in Phoenix provided an avenue for recruitment, offering a trusted environment where refugee women could learn about the study and express their interest in participation. Interested individuals reached out to our team member, and utilizing a snowballing technique, referrals from initial participants expanded our pool of potential candidates. Through informal interactions and focus groups held at these centers, we engaged with refugee women who met the inclusion criteria: being 18 years old and older, having entered the U.S. as an asylum seeker or refugee, speaking basic English, and demonstrating interest in entrepreneurship and sustainability.

Intervention Framework and Mixed Methods Design.

The second phase of the BECRW program encompassed the completion of the six-week summer institute, during which participants were immersed in a carefully crafted curriculum integrating theory-driven and research-based approaches. The curriculum ensured inclusion of content related to the diverse educational backgrounds, skills, and aspirations of refugee women. This included addressing specific challenges such as language barriers, cultural differences, and family responsibilities, while also integrating subjects that built capacity in areas like professional skills training, financial literacy, and environmental sustainability. Modules addressing gender bias, the impact of migration on women, and issues of gender-based violence, discrimination, and harassment were also incorporated. Synchronous and asynchronous online courses were provided, allowing participants to join live sessions or watch recorded courses at their convenience. The program recognized that refugee women often faced dual challenges: significant family caregiving responsibilities affecting their access to education and hindering their professional aspirations (Cole et al., 2013 ; Crawford et al., 2023 ; Sansonetti, 2016 ; Wight et al., 2021 ). The study revealed that many participants juggled childcare and family care daily, limiting their time for personal development. To address this, the BECRW program offered flexible schedules, supportive services, and a learner community chat group. This tailored approach enhanced accessibility and relevance, boosting participation and success rates among refugee women, enabling them in fulfilling the multiple roles they play.

As part of this intervention, all 20 female participants were mandated to attend or watch specialized lectures on entrepreneurship and small businesses as well as to submit assignments and presentations. These activities aimed to equip them with the knowledge and skills necessary to develop their entrepreneurial ventures. The program offered a flexible learning format to accommodate the diverse responsibilities and constraints faced by refugee women, such as childcare or household duties. Furthermore, the program also created a safe and inclusive learning environment, considering potential trauma and psychological challenges experienced by participants. This involved trauma-informed teaching practices, flexible attendance policies, trigger warning policies, and peer support groups. Each participant was paired with a graduate mentor to provide support throughout the duration of the program, ensuring adaptability and responsiveness to their requirements. Additionally, the program focused on capacity- building for participants by facilitating networking opportunities, peer support groups, and access to resources such as laptops and financial support. Involvement of the local community and potential employers further enhanced inclusivity, breaking down stereotypes and creating tailored business opportunities for refugee women. Encouraging a sustainable approach, participants were prompted to explore entrepreneurial ideas with an eco-friendly focus, fostering a culture of environmentally responsible business practices.

In the third phase, the BECRW program implemented a robust evaluation and post-program follow-up process. This involved a pre-and post-test study design with the 20 participants taking a survey before and after their participation in the program. This survey aimed to measure the impact of the program on participants’ emotional, social, and psychological well-being as well as life satisfaction. Furthermore, a qualitative evaluation was conducted three months after the program’s conclusion, allowing participants to reflect on how their engagement in the SISCC and BECRW had influenced their lives, personally and professionally. The final phase of the program involved post-program evaluation, data analysis, and the generation of a comprehensive final report. By collating and analyzing the data collected, program’s effectiveness and impact were assessed, providing valuable insights for project improvement and future dissemination. In this context, the effectiveness metric, referred to how well the BECRW program achieved its intended outcomes in real-world settings among refugee women participants. It assessed the program’s ability to improve participants’ personal and professional development, well-being, and social inclusion within their actual experiences and environments. This evaluation was conducted with a feasible degree of control, aimed at minimizing the influence of external factors on the results. Furthermore, the anonymous feedback provided by the participants served as a key resource for understanding their perspectives and experiences, further refining the program’s design and delivery.

Study population

The BECRW program engaged a group of 20 refugee women, recruited from the cities of El Paso, Texas, and Phoenix, Arizona in the U.S. While the demographic characteristics of these participants were diverse, they were representative of the population in the southwestern U.S. Nonetheless, these characteristics may not fully encompass the diversity of refugee women globally, as different regions may present distinct challenges and resources for refugee integration. For instance, Texas, as one of the largest refugee resettlement centers in the United States, has welcomed over 44,000 refugees in the last ten years, whereas Arizona has welcomed over 20,000 refugees in the same period. American Immigration Council Footnote 10 indicates varying levels of consumer power among refugees, with Texas boasting a consumer power of $5.4 billion compared to Arizona’s $1.0 billion. Among the 20 participants in the BECRW program, half entered the US as asylum seekers, while the remaining half arrived as refugees. Throughout the program duration, all participants maintained permanent residency status in the U.S. It is essential to underscore that both refugees and asylum seekers encounter profound challenges in their host countries, stemming from their escape from war, violence, or persecution in their home countries. While refugees benefit from recognized status and certain rights, asylum seekers grapple with the uncertainty surrounding their legal standing, which can impede their access to vital services and protection (Davaki, 2021 ; Fonteneau, 1992 ). The challenges faced by refugees and asylum seekers have a lasting impact, persisting even after resettlement. Adjusting to a new country, navigating cultural differences, and rebuilding one’s life after displacement are complex processes requiring time and support. Barriers such as language, discrimination, and trauma persist even after obtaining permanent residency or being employed (O’Donnell et al., 2020 ). During the pre-program informal meetings with the participants, all of them expressed the lack of their ability to integrate into the host society irrespective of their employment status. In the BECRW program, the participants represent a diverse refugee women population with different migratory journeys, backgrounds, country of origin, education, age, employment, and marital status and number of years in the U.S. as shown in Table 1 . It is important to note that one participant discontinued their participation midway, and the demographics discussed above pertain to the remaining 19 participants.

Grand research question

Can a gender-focused educational intervention, exemplified by the BECRW program, effectively enhance the subjective well-being and empowerment of female refugees, particularly in the context of fostering sustainable practices, integration into host societies, and long-term contributions to climate change adaptation and resilience? This study expands upon several key points, including:

Developing targeted interventions to foster advancement among refugee women.

Investigating the potential of refugee women as agents of change and resilience within their host communities, while identifying effective strategies and approaches to enable their meaningful contributions to sustainable practices and solutions.

Analyzing the intersectionality of gender and immigration status and its implications for climate change adaptation among refugee women.

Investigating the synergistic relationship between STEM and social science disciplines in building the capacity of refugee women to engage in climate change adaptation efforts.

Providing recommendations for policymakers, educators, and stakeholders on inclusive and empowering interventions that address the specific needs and potential of refugee women in the context of climate change adaptation.

Inspired by the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (Cf 2015 ) Footnote 11 , particularly Goal 5: Gender Equality, Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth, Goal 10: Reducing Inequalities and Goal 13: Climate Action, this study emphasizes the importance of empowering women and addressing climate change impacts through an intersectional lens. The intersectionality between gender and migratory status adds layers of complexity to the challenges faced by refugee women. This intersectionality influences their vulnerability and capacity to adapt to climate change. They often experience compounded discrimination and marginalization, which affects their ability to access resources and participate in adaptation strategies effectively (Davies and True, 2018 ; Liebig and Tronstad, 2018 ). Understanding these intersections is crucial for developing inclusive and effective adaptation programs.

The present study investigated the effectiveness of the BECRW educational program for refugee women’s empowerment through a sequential explanatory mixed methods design (Ivankova et al., 2006 ). Empowerment in this context refers to equipping participants with tools and resources to achieve economic independence, community integration, and control over their circumstances, given their limited access to formal employment and entrepreneurial opportunities. Drawing from Adams ( 2017 ), empowerment involves individual and collective efforts to maximize quality of life, build capacity for strength, confidence, and financial independence. It encompasses both self-empowerment and professional support to overcome isolation, powerlessness, and lack of influence while facilitating access to resources. In this study, the mixed methods design was embedded within the intervention program as shown in Fig. 2 . The design involved two phases: quantitative data collection and analysis followed by qualitative data collection and analysis. The rationale behind this design was to first establish a general understanding of the research problem through quantitative data, and then explain the quantitative results by exploring participants’ views through qualitative data. The quantitative phase utilized a pre-and post-program survey to gather numerical data on participants’ well-being, while the qualitative phase involved semi-structured interviews to gain in-depth insights into participants’ experiences. The survey scales and interview questions were purposefully selected and designed to align with the study’s conceptualization of how the educational program facilitated the empowerment of the refugee women participants. The sequential mixed methods design was chosen for its strengths in providing a more comprehensive understanding of the research question. By integrating quantitative and qualitative methods, the research team aimed to gain a deeper insight into the experiences, perspectives, and outcomes of the refugee women participating in the educational program (Fetters et al., 2013 ). This allowed for a nuanced and multifaceted evaluation of the research objectives, capturing the complexity of the participants’ experiences within the program. The subsequent sections will provide a detailed overview of the study’s quantitative and qualitative research designs.

Quantitative study design

The hypothesis of this study posits that the designed BERCW program is effective in improving the participants’ satisfaction with life, emotional, social, and psychological well-being and confidence, facilitating their integration into the host society. To investigate this hypothesis, surveys were employed as the primary mode of data collection. Surveys offer several advantages, including statistical analysis, scalability for a large number of participants, and the potential for anonymous responses that encourage openness and honesty (Braun et al., 2021 ; Mathers et al., 1998 ). A pre-, post-test study design was administered to the 19 participating refugee women. The surveys were collected through an online medium. The pre-program survey served as a baseline assessment. The survey consisted of closed-ended questions. Following the completion of the program, the same group of participants completed the post-program survey. The post-program survey mirrored the pre-program survey, enabling a direct comparison of participants’ responses before and after the program.

This study utilized validated scales to measure various aspects of participants’ well-being and life satisfaction. The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) was employed to assess participants’ overall life satisfaction. The SWLS consists of five items answered on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Higher scores on the SWLS indicate greater life satisfaction. The SWLS has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties, including discriminant validity (Diener et al., 1985 ). The Mental Health Continuum Short Form (MHC-SF) was used to measure participants’ emotional, psychological, and social well-being. The MHC-SF comprises 14 items answered on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (every day). The scale provides three scores: hedonic well-being, eudaimonic well-being, and social well-being. Higher scores on the MHC-SF indicate greater well-being. The MHC-SF has been validated for use in individuals aged 12 years and older, demonstrating satisfactory psychometric properties across diverse samples (Lamers et al., 2011 ).

The utilization of the SWL and the MHC-SF scales in this study was highly relevant to examine the hypothesis. The SWL scale directly measures the program’s impact on participants’ satisfaction with their lives, which is an essential indicator of the intervention’s effectiveness in enhancing their overall well-being and integration as defined earlier in “Institute Framework”. The MHC-SF scale complements the SWLS by capturing multiple dimensions of well-being, including emotional, psychological, and social well-being (Tiberius and Hall, 2010 ), which are closely associated with participants’ confidence and empowerment that facilitate their integration. Notably, these scales serve as valuable measures of empowerment, a crucial factor in determining the program’s effectiveness as discussed in “Method”. The psychological well-being dimension of the MHC-SF scale assesses aspects such as personal growth, purpose, and meaning in life, which are essential for empowerment and self-confidence. Additionally, the social well-being dimension captures participants’ social relationships and connections, which contribute to their empowerment by overcoming feelings of isolation and fostering access to resources. Together, the SWL and MHC-SF scales provide a comprehensive evaluation of the program’s effectiveness in improving participants’ satisfaction with life, emotional, social, and psychological well-being, confidence, empowerment, and facilitating their integration into the host society.

In this one-group pre-and post-test design, several limitations were encountered by the researchers. This study can be categorized as a pre-experimental design due to the absence of randomization in sampling, lack of a control group, and inability to control for potential confounding variables arising from small sample size, high variability in demographics, and challenges in recruiting from vulnerable populations such as refugee women (Agadjanian and Zotova, 2012 ; Steel et al., 2009 ). Pre-experimental designs, typically exploratory in nature, are employed when resources, time, or participant access are limited (Campbell and Riecken, 1968 ). While such studies offer preliminary insights into variable relationships and trends, they are less robust in establishing causal relationships compared to true experimental designs. Previous studies have accounted for demographic characteristics as control variables that have a confounding effect on the dependent and independent variables of the study (Cheung and Phillimore, 2017 ). In this study, variables such as age, employment status, education level, and, years in the US could potentially confound the relationship between the BERCW program intervention and outcomes like satisfaction with life and overall well-being. Therefore, for future true experimental designs, it is imperative to control for these variables to accurately assess the intervention’s effects. Additionally, incorporating random sampling and a control group is essential to enhance generalizability, allowing findings to be extended to broader populations or contexts beyond the study’s specific sample or setting.

As previously noted, the limitation of a small sample size and substantial variability in demographics underscores the need for future research to ensure adequate representation across demographic categories. According to established literature guidelines (Hertzog, 2008 ), having a minimum of 30 samples in each category is considered good practice to mitigate biased outcomes regarding intervention effectiveness. Based on calculations considering factors such as confidence level (95%), margin of error (5%), population size (approx. 6000 female refugee population in Texas and Arizona in 2023 Footnote 12 ), and standard deviation, it is recommended that future studies aim for a sample size of 350–400 participants to conduct a robust analysis. This larger sample size would better facilitate meaningful insights and statistical significance in evaluating intervention effectiveness. Given the exploratory nature of our study, an a priori power analysis was not conducted; instead, our focus was on identifying trends to inform subsequent qualitative investigation. Paired samples t-tests (De Winter, ( 2013 )) were conducted to explore differences between pre-and post-intervention SWLS and MHC- SF scores. Statistical significance was set at alpha 0.05. In “Results”, the descriptive data is presented as means and standard deviations for overall pre- and post-program comparison and as means across different demographic and background categories, for the continuous data. Descriptive data is presented as proportions for categorical data in “Study Population”. The data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 28.

Qualitative study design

The research question guiding the inquiry and exploration in the qualitative study design is: Is the BECRW intervention effective in improving the participant’s satisfaction with life, emotional, social, and psychological well-being and confidence, facilitating their integration into society? While the quantitative study provided valuable numerical data and statistical analysis, it did not capture the context, personal experiences, and subjective perspectives of the participants (Sandelowski, 2010 ). The aim for using both approaches was to complement each method’s limitations and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the research objective as discussed in “Grand Research Question”. The sample size used in qualitative research methods is often smaller compared to quantitative research methods and does not tend to rely on hypothesis testing but rather is more inductive and emergent in its process (Boddy, 2016 ). A sample size of 20–30 participants is the common average sample size required to reach saturation and redundancy in qualitative research that utilizes in-depth interviews. In this study, 19 refugee women were interviewed.

In qualitative research, the selection of an appropriate interview technique is crucial to effectively capture the data that aligns with the study’s objectives. Cohen and Manion ( 1994 ) identified four interview techniques: structured, semi-structured/unstructured, non-directive, and focused. For this study, the investigative team purposefully chose semi-structured, open-ended interviews as the data collection method. Semi-structured, open-ended interviews were selected due to their flexibility and ability to gather rich and detailed information from participants. This interview format provided participants with the freedom to express their thoughts, experiences, and emotions openly, allowing for a deeper exploration of their perspectives. The open-ended nature of the interviews enabled participants to provide in-depth and comprehensive responses, shedding light on their lives before and after their involvement in the BECRW program.

A demographic questionnaire and observation through field notes were utilized alongside the interviews. The data collection process prioritized the protection of participants’ privacy. The informed consent form emphasized the confidentiality of the data and outlined the measures taken to safeguard participants’ identities. Participants were assured that only the team would have access to the data. They were assigned a participant study identification number (PXX) to de-identify the data, that were securely stored on a password-protected computer and accessible only to approved researchers. The semi-structured, open-ended interviews were conducted both virtually and in person, lasting approximately 60 min. A Zoom audio recording and auto-mated transcription were generated. The demographic questionnaire aimed to gather basic information about participants such as name, place of origin, education, and marital status. The team employed the active or moderate participatory observer role as defined by Spradley ( 2016 ) to generate a context for the interview paying attention to the participant’s setting, clothes, and body language.

The interview questions in this study were thoughtfully developed, drawing insights from the observations and field notes collected throughout the program, and the preliminary quantitative outcomes. The aim was to design questions that would comprehensively explore multiple dimensions of the participants’ experiences. The questions sought to gain insights into their daily routines, highlighting any changes observed during and post the program. Participants were encouraged to share their experiences of interacting with STEM researchers and graduate students, providing a deeper understanding of the program’s impact on their engagement with the academic community. Questions delved into the resources available to the participants for project development which allowed the investigative team to gain insight into the practical support and opportunities provided by the program. Participants were also prompted to reflect on how the program had influenced them personally and how it had affected their immediate family. These questions aimed to uncover the transformative potential of the educational program on both an individual and familial level. The interview questions explored the participants’ sharing of their program experiences with others in their communities and their role as potential agents of change. Finally, the questions invited participants to reflect on the whole program, providing an opportunity to share their thoughts and emotions about their overall experience. This allowed the team to capture the immediate and lasting effects of the program, as well as the participants’ perspectives on future participation in similar initiatives. To ensure the quality and rigor of this qualitative descriptive research, several trustworthiness criteria were employed. Four criteria were utilized: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. Credibility was established through prolonged engagement with participants, persistent observation, and peer debriefing (Sandelowski, 2000 ), which involved a thorough review and discussion of the findings. Transferability was achieved through a detailed description of the research process, allowing readers to assess the applicability of the results to other settings. Dependability and confirmability were ensured through audibility (Khatib, 2013 ), maintaining a clear trail of decision-making and research progression. Strategies such as coordination between investigators, cross-checking codes, and external auditing were employed to enhance the quality and rigor of the research (Creswell and Zhang, 2009 ; Sandelowski, 1986 ).

The researchers acknowledge that their positionality influences the research process and outcomes. Their backgrounds and experiences shape their interactions with participants and data interpretation. Recognizing the power dynamics inherent in working with a vulnerable population of refugee women, they adopted a participatory approach to ensure that the women’s voices are central to the analysis. One team member, having lived as a refugee, provided valuable insights that helped bridge the gap between researchers and participants. Each team member engaged in self-reflection aligning with Van Manen ( 2016 )’s “reflective journaling” to set aside biases. This practice, supported by Creswell and Poth ( 2016 ) and Patton ( 2014 ), aimed to create a balanced and authentic representation of the participants’ experiences.

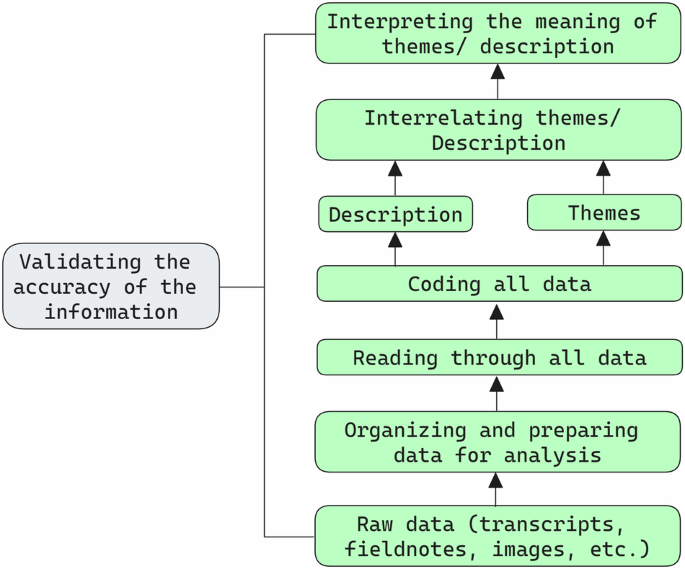

The data analysis process involved a recursive and iterative approach, closely tied to the data collection phase. The analysis process for this qualitative study involved a systematic approach to derive emerging themes from the transcribed verbatim data as shown in Fig. 3 . After the Zoom automated transcription, the research team carefully reviewed and compared the transcriptions with the audio files to ensure accuracy. The analysis followed an inductive and bottom-up approach, focusing on understanding the meaning held by the participants. The researchers engaged in multiple reexaminations of the data, seeking a deeper understanding and making interpretations of the larger meaning. Marginal comments were placed on the text during these readings, and color-coded categories were created on a spreadsheet to record potential themes that emerged from the data. Both interview and observational data were considered during this process. The researchers further examined and discussed the developing themes among themselves, seeking agreement and refining the speculative themes. Additional perspectives from the research team members were sought to reevaluate, modify, or eliminate themes. This iterative process of analysis allowed for a thorough exploration and interpretation of the data, resulting in the identification of meaningful and representative themes.

Model of Qualitative Data Analysis, Creswell and Creswell ( 2017 ).

Quantitative results

The quantitative results of the study indicate that there were slight improvements in the scores of participants’ subjective well-being measures after the implementation of the BECRW program as shown in Table 2 . Specifically, the scores on the SWLS increased from 5.15 to 5.17, although this change was not statistically significant ( t (18) = −0.11, p = 0.91). Similarly, there were improvements in eudaimonic well-being, both in terms of social well-being and psychological well-being, but these changes did not reach statistical significance. Social well-being increased from 4.55 to 4.77 ( t (18) = −1.62, p = 0.12), and psychological well-being increased from 4.92 to 5.19 ( t (18) = −1.79, p = 0.08). On the other hand, there were no significant changes in hedonic (emotional) well-being, which remained relatively stable throughout the study period ( t (18) = 0.00, p = 1.00). In the presented results, the standard deviation values for each characteristic were relatively high, indicating considerable variability in participants’ scores. This variability suggests that participants’ experiences and responses varied widely, which could be influenced by individual differences or external factors. It is important to note that while the observed changes were not statistically significant, they provide some indications of positive shifts in participants’ well-being following their participation in the BECRW program. Table 3 shows the effect size (Cohen’s d) and statistical power for the outcomes. It indicates small to medium effects across the scores, with notably low statistical power, highlighting the need for caution in interpreting the results due to potential under-powering of the study. Table 4 illustrates variations across different demographic and background variables. It highlights the influence of factors such as age, education, years in the USA, and employment status on participants’ subjective well-being. As explained earlier, with a larger sample size and by accounting for the control variables, the uncertainties can be reduced and significance of this study can be increased. These quantitative findings are complemented by qualitative results, that will be discussed in “Qualitative Results”.

Qualitative results

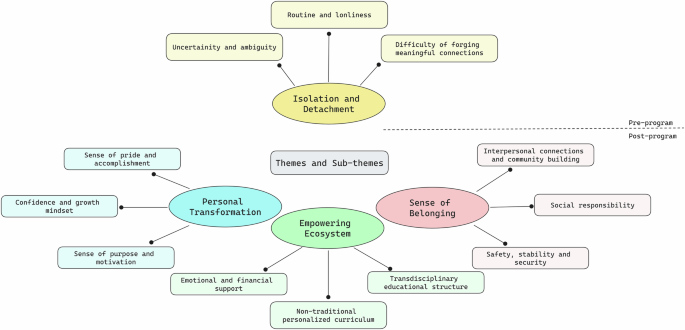

The qualitative analysis revealed that participants felt isolated and detached before the program, but after the program they experienced personal transformation, felt empowered by the supportive environment, and developed a sense of belonging within the community. These themes suggest that the BECRW program was effective in fostering societal integration by addressing challenges, enabling personal growth, and cultivating community connections. The analysis of the data centered on three primary areas at two distinct time points, namely, before and after the program. These areas served as the basis for identifying the four emerging themes that capture the participants’ experiences in this study as shown in Fig. 4 . The key domains for theme extraction were as follows:

personal /daily schedule & activities,

academic/professional development, and

state of being

Emerging Themes and Sub-themes.

The four emerging themes were categorized into two phases: pre-program and post-program. These themes are presented and examined as follows:

Pre-program emerging theme

Isolation and Detachment . The participants candidly shared their pre- program experiences, offering insights into their daily routines, social interactions, and life in the United States. These narratives collectively unveiled a prevailing theme of isolation and detachment, which stemmed from their refugee journeys, as detailed in Table 5 . Within this thematic exploration, participants eloquently recounted the hurdles they encountered while navigating unfamiliar terrain and striving to reconstruct their lives as refugees. They described the daily routines and solitude that consumed their lives, leaving little time for social interactions and meaningful connections. They expressed feelings of loneliness and the struggle to establish relationships in their new surroundings. The participants also faced uncertainty and ambiguity in pursuing their goals, lacking clarity and direction due to their circumstances. Overall, this theme highlights the profound impact of displacement and the challenges faced in building a sense of belonging in their new environment.

Post-program emerging themes

Personal Transformation . The second theme centers on personal transformation, underscored by the journey of growth and empowerment through the program as highlighted by the participants in Table 6 . They shared how the program equipped them with valuable business and sustainability knowledge and skills, resulting in a profound sense of pride, accomplishment, and boosted confidence. This newfound confidence fostered a growth mindset, motivating them to pursue entrepreneurial aspirations. Moreover, the program instilled a sense of purpose and motivation, propelling them to address sustainability challenges within their business ventures. Ultimately, this theme highlights the program’s transformative influence on the participants’ personal and entrepreneurial paths.

Empowering Ecosystem . The third theme revolves around the program’s empowering ecosystem, as revealed by the participants in Table 7 . They emphasized the invaluable support provided by the program, providing emotional and financial support, which created a safe and nurturing learning environment. The one-to-one mentorship and the sense of belonging to a supportive community were particularly highlighted. Furthermore, participants highlighted key milestones in their journey, such as participation in the conference and business pitch presentations, as pivotal sources of confidence and advancement. They praised the program’s non-traditional and personalized curriculum, which equipped them with practical knowledge and critical thinking skills, specifically tailored to address sustainability and climate change challenges. The transdisciplinary educational structure, merging STEM and social science disciplines, broadened their perspectives and aligned seamlessly with their career aspirations. In sum, this theme underscores the program’s role in providing a comprehensive and empowering ecosystem that significantly contributed to the participants’ growth and positive experiences.

Sense of Belonging . The final theme delves into participants’ profound sense of belonging, encompassing various dimensions as outlined in Table 8 . This study explores three critical facets of belonging: personal, professional, and within the broader host community. Participants described the meaningful connections and networks that flourished both within and beyond the program, enriching their experiences and facilitating personal growth. Moreover, they consistently expressed a deep commitment to social responsibility, a fervent desire to empower others, and a strong aspiration to make a positive impact in their communities. This sense of purpose and altruism further solidified their connection to the host community. The program’s supportive structure and nurturing learning environment played a pivotal role in creating a profound sense of safety, stability, and security among the participants. This theme serves as a poignant reminder of the paramount importance of fostering belonging and empowering individuals to chase their entrepreneurial dreams while actively contributing to the betterment of their communities.

The findings of this study illuminate the critical need for tailored and gender-specific interventions at the intersection of educational and entrepreneurial capacity building for refugees. Moreover, it emphasizes the importance of integrating an intersectional perspective in policies and programs for refugee women. By acknowledging the unique intersections of gender, migratory status, and climate vulnerability, interventions can be better tailored to address their specific needs and challenges. Thompson-Hall et al. ( 2016 ) highlight the importance of intersectional research in climate change adaptation, advocating for inclusive strategies that consider the diverse and overlapping vulnerabilities of different social groups. Similarly, Crenshaw ( 2013 ) underscores the need to empower those who are marginalized due to their intersecting identities, such as the refugee women population. To the best of our knowledge, there is a gap in the existing literature on the social integration and empowerment of refugee women into the host society through such targeted approaches. This study contributes to the refugee integration and refugee empowerment literature by developing and evaluating the effectiveness of a gender-specific, culturally sensitive, and community-focused program (BECRW). The non-traditional and transdisciplinary framework employed in this study focuses on the overall well-being, personal growth, and professional development of refugee women. It aligns with the broader key United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs), particularly those related to climate change, sustainability, and gender equality. By equipping these women, it empowers them to become valuable contributors to the host society and actively participate in building climate resilience within their communities.

In their systematic review article, Gower et al. ( 2022 ) emphasize the scarcity of intervention-focused studies in refugee integration, particularly those lacking a gender dimension. Among the 12 studies they reviewed, only three utilized a mixed methods approach, with three based in the U.S. Notably, five peer mentoring programs were tailored specifically to women, yet the majority of these studies involved fewer than 20 female refugee and migrant participants. They acknowledge difficulty in reaching the refugee community for participation in such initiatives. Only two programs combined group workshops with individual mentoring sessions, and nearly all interventions were conducted in person. In contrast, the BECRW program stands out as an educational, gender-focused intervention empowering refugee women with entrepreneurial skills. This program employs a mixed methods approach, capturing both numerical trends and qualitative insights. It targets refugee women in the U.S., recognizing and addressing their unique challenges such as limited employment opportunities and social isolation. One of the strengths of the BECRW program lies in its structure and curriculum, which combines theory-driven and research-based approaches. This program distinguishes itself through the synergy between STEM and social sciences disciplines. Notably, the BECRW program organized a conference where refugee women participants had the opportunity to showcase their work alongside scientific communities from various disciplines and levels, highlighting the program’s inclusivity and impact. The program was flexible and incorporated group activities, one-on-one mentoring, and hands-on experience. The entire BECRW program was conducted online, with support offered to those who wished to attend the conference in person.

Cheung and Phillimore ( 2017 ) conduct a pioneering quantitative analysis of integration outcomes among refugees in the United Kingdom (U.K.), focusing on broader integration and social outcomes. In contrast, this study specifically targets empowerment and well-being among refugee women by providing tailored instructional training and mentorship to address their specific needs and equip them with the skills and knowledge necessary for building entrepreneurial capacity. Street et al. ( 2022 ) explore the impact of refugee women entrepreneurs serving as mentors to others in the U.K., while Senthanar et al. ( 2021 ) investigate the motivations and challenges of entrepreneurship among Syrian refugee women in Canada, highlighting systemic barriers and gendered contexts that shape their entrepreneurial endeavors in industries like food/catering and tailoring. Similarly, Mangrio et al. ( 2019 ) and Spehar ( 2021 ) primarily discuss the challenges and barriers faced by refugee women without proposing solutions. In contrast, this study not only identifies these barriers but also contributes to the literature by proposing a solution through the development of the BECRW intervention. This intervention addresses both the technical and socio-cultural dimensions of entrepreneurship for refugee women by adopting a gender-focused, culturally embedded approach.