- Open access

- Published: 12 December 2017

Acceptance of a systematic review as a thesis: survey of biomedical doctoral programs in Europe

- Livia Puljak ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8467-6061 1 , 2 , 3 &

- Damir Sapunar 3

Systematic Reviews volume 6 , Article number: 253 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

15k Accesses

21 Citations

66 Altmetric

Metrics details

Systematic reviews (SRs) have been proposed as a type of research methodology that should be acceptable for a graduate research thesis. The aim of this study was to analyse whether PhD theses in European biomedical graduate programs can be partly or entirely based on SRs.

In 2016, we surveyed individuals in charge of European PhD programs from 105 institutions. The survey asked about acceptance of SRs as the partial or entire basis for a PhD thesis, their attitude towards such a model for PhD theses, and their knowledge about SR methodology.

We received responses from 86 individuals running PhD programs in 68 institutions (institutional response rate of 65%). In 47% of the programs, SRs were an acceptable study design for a PhD thesis. However, only 20% of participants expressed a personal opinion that SRs meet the criteria for a PhD thesis. The most common reasons for not accepting SRs as the basis for PhD theses were that SRs are ‘not a result of a PhD candidate’s independent work, but more of a team effort’ and that SRs ‘do not produce enough new knowledge for a dissertation’. The majority of participants were not familiar with basic concepts related to SRs; questions about meta-analyses and the type of plots frequently used in SRs were correctly answered by only one third of the participants.

Conclusions

Raising awareness about the importance of SRs and their methodology could contribute to higher acceptance of SRs as a type of research that forms the basis of a PhD thesis.

Peer Review reports

Systematic reviews (SRs) are a type of secondary research, which refers to the analysis of data that have already been collected through primary research [ 1 ]. Even though SRs are a secondary type of research, a SR needs to start with a clearly defined research question and must follow rigorous research methodology, including definition of the study design a priori, data collection, appraisal of study quality, numerical analyses in the form of meta-analyses and other analyses when relevant and formulation of results and conclusions. Aveyard and Sharp defined SRs as ‘original empirical research’ because they ‘review, evaluate and synthesise all the available primary data, which can be either quantitative or qualitative’ [ 2 ]. Therefore, a SR represents a new research contribution to society and is considered the highest level in the hierarchy of evidence in medicine [ 3 ].

SRs have been proposed as a type of research methodology that should be acceptable as the basis for a graduate research thesis [ 4 , 5 ]. To the best of our knowledge, there are no reports on the acceptance of SRs as the basis for PhD theses. A recent review addressed potential advantages and disadvantages of such a thesis type and presented opposing arguments about the issue [ 5 ]. However, there were no actual data that would indicate how prevalent one opinion is over another with regard to the acceptance of a SR as the primary research methodology for a PhD thesis. The aim of this cross-sectional study was to assess whether a PhD thesis in European biomedical graduate programs can be partly or entirely based on a SR, as well as to explore the attitudes and knowledge of individuals in charge of PhD programs with regard to a thesis of this type.

Participants

The Organization of PhD Education in Biomedicine and Health Sciences in the European System (ORPHEUS) includes 105 institutional members from 40 countries and six associate members from Canada, Georgia, Iran, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and the USA [ 6 ]. The ORPHEUS encompasses a network of higher education institutions committed to developing and disseminating best practice within PhD training programs in biomedicine, health sciences and public health. ORPHEUS approved the use of their mailing list for the purpose of this study. The mailing list had 1049 contacts. The study authors were not given the mailing list due to data protection and privacy. Instead, it was agreed that ORPHEUS officials would send the survey via email to the mailing list. The General Secretary of the ORPHEUS contacted individuals responsible for PhD programs (directors or deputy directors) among the institutional members, via e-mail, on 5th of July 2016. These individuals were sent an invitation to complete an online survey about SRs as the basis for PhD theses. We invited only individuals responsible for PhD programs (e.g., directors, deputy directors, head of graduate school, vice deans for graduate school or similar). We also asked them to communicate with other individuals in charge of their program to make sure that only one person per PhD program filled out the survey. If there were several PhD programs within one institution, we asked for participation of one senior person per program.

The survey was administered via Survey Monkey (Portland, OR, USA). The survey took 5–10 min to complete. One reminder was sent to the targeted participants 1 month after the first mail.

The ethics committee of the University of Split School of Medicine approved this study, which formed part of the Croatian Science Foundation grant no. IP-2014-09-7672 ‘Professionalism in Health Care’.

Questionnaire

The 20-item questionnaire, designed specifically for this study by both authors (LP and DS), was first tested for face validity and clarity among five individuals in charge of PhD programs. The questionnaire was then modified according to their feedback. The questionnaire included questions about their PhD program; whether PhD candidates are required to publish manuscript(s) before thesis defence; the minimum number of required manuscripts for defending a PhD thesis; the authorship requirements for a PhD candidate with regard to published manuscript(s); whether there is a requirement for a PhD candidate to publish manuscript(s) in journals indexed in certain databases or journals of certain quality, and how the quality is defined; the description about other requirements for defending a PhD thesis; whether a SR partly or fully meets requirements for approval of a PhD thesis in their graduate program; what are the rules related to the use of a SR as the basis for a PhD thesis; and the number of PhD theses based on SRs relative to other types of research methods.

Participants were also asked about their opinion with regard to the main reasons that SRs are not recognised in some institutions as the basis for a doctoral dissertation, and their opinion about literature reviews, using a four-item Likert scale, ranging from ‘agree’ to ‘disagree’, including an option for ‘don’t know’. In the last question, the participants’ knowledge about SR methodology was examined using nine statements; participants had to rate each statement as either ‘correct’, ‘incorrect’, ‘unsure’ or ‘I don’t know’. Finally, participants were invited to leave their email address if they wanted to receive survey results. The survey sent to the study participants can be found in an additional file (Additional file 1 ).

Data analysis

Survey responses were entered into a spreadsheet, checked by both authors and analysed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Inc., Redmond, WA, USA). Descriptive data are presented as frequencies and percentages. All raw data and analysed data sets used in the manuscript are available from authors on request. A point-biserial correlation (SPSS, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to measure the strength of the association between results on the knowledge test (continuous variable) and the attitude towards SRs as the basis for dissertations (dichotomous variable; we used the answer to the following question as this measure: ‘Do you agree that a systematic review, in whole or in part, meets the criteria for a publication on which a doctoral dissertation can be based?’).

Study participants

There are 105 institutions included in the ORPHEUS network. We received a response from 86 individuals representing 68 institutions from 37 countries (65% institutional response rate). There were more respondents than institutions because some institutions have several PhD programs and thus several program directors. Those responders were used as a unit of analysis in the analysis of attitudes and knowledge; institutions were the unit of analysis when analysing criteria for theses. Some of the questionnaires ( n = 15) were only partly completed. In most cases, the missing data were related to knowledge about SR methodology.

Overview of requirements for a dissertation

Based on the information provided by the graduate program directors, in the majority of the included PhD programs, students were required to publish a research manuscript prepared within their PhD thesis prior to their thesis defence (83%; n = 64). Among 13 programs (17%) that did not have this requirement, five respondents (38%) indicated that in their opinion their school’s rules related to a PhD thesis should be changed such as to specify that each thesis should be based on work that is already published in a journal.

The minimum number of published manuscripts necessary for the PhD thesis defence was prespecified in 94% ( n = 60) of the programs that required publication of research manuscripts prior to the thesis defence. In most of the programs (37%; n = 22), the number of required manuscripts was three or more. Two manuscripts were required in 30% ( n = 18) and one was required in 33% ( n = 20) of the programs. In four programs, there was no formal policy on this matter, but there was a strong expectation that the student will have contributed substantially to several manuscripts in peer-reviewed journals.

In most cases, the PhD candidates’ contribution to published manuscripts within the PhD thesis was determined through first authorship. A requirement that a PhD candidate should be the first author on a manuscript(s) that constitutes a PhD thesis was reported in 82% ( n = 64) of the graduate programs.

In 60% ( n = 52) of the graduate programs, the quality of the journals where a PhD candidate has to publish research manuscripts as a part of a PhD thesis was defined by the database in which these journals are indexed. The most commonly specified databases were Web of Science (41%; n = 35) and MEDLINE/PubMed (13%; n = 11), followed by Science Citation Index, Scopus, Current Contents, a combination of several databases or, in two cases, a combination of journals from a list defined by some governing body.

Systematic reviews as a PhD thesis

SRs, in whole or in part, met the criteria for acceptable research methodology for a PhD thesis in 47% ( n = 40) of programs, whereas 53% ( n = 46) of programs specifically stated that they did not accept SRs in this context (Fig. 1 a, b). Among the programs that accepted SRs, theses could be exclusively based on a SR in 42% ( n = 17) of programs, while in the remaining programs, SRs were acceptable as one publication among others in a dissertation.

a European PhD programs that recognise a systematic review as a PhD thesis (green dot) and those that do not (red dot). Half red and half green dots indicate the five universities with institutions that have opposite rules regarding recognition of a systematic review as a PhD thesis. The pie chart presents b the percentage of the programs in which systematic reviews, in whole or in part, meet the criteria for a dissertation and c the opinion of participants about whether systematic reviews should form the basis of a publication within a PhD dissertation

The majority of participants (80%; n = 69) indicated that SRs did not meet criteria for a publication on which a PhD dissertation should be based (Fig. 1 c). The main arguments for not recognising a SR as the basis for a PhD thesis are listed in Table 1 . The majority of respondents were neutral regarding the idea that scoping reviews or SRs should replace traditional narrative reviews preceding the results of clinical and basic studies in doctoral theses. Most of the respondents agreed that narrative or critical/discursive literature reviews preceding clinical studies planned as part of a dissertation should be replaced with systematic reviews (Table 2 ).

Most of the programs that accepted SRs as a research methodology acceptable for PhD theses had defined rules related to the use of an SR as part of a PhD thesis (Fig. 2 ). The most common rule was that a SR can be one publication among others within a PhD thesis. Some of the respondents indicated that empty (reviews that did not find a single study that should be included after literature search) or updated reviews could also be used for a PhD thesis (Fig. 2 ).

Frequency of different rules that define the use of systematic reviews as a part of a PhD thesis in European biomedical graduate programs

The results of the survey regarding knowledge about SR methodology indicated that the majority of respondents were not familiar with this methodology. Only three out of nine questions were correctly answered by more than 80% of the participants, and questions about meta-analyses and the type of plots frequently used in a SR were correctly answered by only one third of the participants (Table 3 ). The association between participants’ results on the knowledge test and attitudes towards SRs was tested using a point-biserial correlation; this revealed that lack of knowledge was not correlated with negative attitudes towards SRs ( r pb = 0.011; P = 0.94).

In this study conducted among individuals in charge of biomedical graduate programs in Europe, we found that 47% of programs accepted SRs as research methodology that can partly or fully fulfil the criteria for a PhD thesis. However, most of the participants had negative attitudes about such a model for a PhD thesis, and most had insufficient knowledge about the basic aspects of SR methodology. These negative attitudes and lack of knowledge likely contribute to low acceptance of SRs as an acceptable study design to include in a PhD thesis.

A limitation of this study was that we relied on participants’ responses and not on assessments of formal rules of PhD programs. Due to a lack of familiarity with SRs, it is possible that the respondents gave incorrect answers. We believe that this might be the case since we received answers from different programs in the same university, where one person claimed that SRs were accepted in their program, and the other person claimed that they were not accepted in the other program. We had five such cases, so it is possible that institutions within the same university have different rules related to accepted research methodology in graduate PhD programs. This study may not be generalisable to different PhD programs worldwide that were not surveyed. The study is also not generalisable to Europe, as there are no universal criteria or expectations for PhD theses in Europe. Even in the same country, there may be different models and expectations for a PhD in different higher education institutions.

A recent study indicated a number of opposing views and disadvantages related to SRs as research methodology for graduate theses, including lack of knowledge and understanding by potential supervisors, which may prevent them from being mentors and assisting students to complete such a study [ 5 ]. This same manuscript emphasised that there may be constraints if the study is conducted in a resource-limited environment without access to electronic databases, that there may be a very high or very low number of relevant studies that can impact the review process, that methods may not be well developed for certain types of research syntheses and that it may be difficult to publish SRs [ 5 ].

Some individuals believe that a SR is not original research. Indeed, it has been suggested that SRs as ‘secondary research’ are different than ‘primary or original research’, implying that they are inferior and lacking in novelty and methodological rigour as compared to studies that are considered primary research. In 1995, Feinstein suggested that such studies are ‘statistical alchemy for the 21st century’ and that a meta-analysis removes or destructs ‘scientific requirements that have been so carefully developed and established during the 19th and 20th centuries’ [ 7 ]. There is little research about this methodological issue. Meerpohl et al. surveyed journal editors and asked whether they consider SRs to be original studies. The majority of the editors indicated that they do think that SRs are original scientific contributions (71%) and almost all journals (93%) published SRs. That study also highlighted that the definition of original research may be a grey area [ 8 ]. They argued that, in an ideal situation, ‘the research community would accept systematic reviews as a research category of its own, which is defined by methodological criteria, as is the case for other types of research’ [ 8 ]. Biondi-Zoccai et al. pointed out that the main criteria to judge a SR should be its novelty and usefulness, and not whether it is original/primary or secondary research [ 9 ].

In our study, 80% of the participants reported negative attitudes, and more than half of the respondents agreed with a statement that SRs are ‘not a result of the candidate’s independent work since systematic reviews tend to be conducted by a team’. This opinion is surprising since other types of research are also conducted within a team, and single authorship is very rare in publications that are published within a PhD thesis. On the contrary, the mean number of authors of research manuscripts is continuously increasing [ 10 ]. At the very least, the authors of manuscripts within a PhD will include the PhD candidate and a mentor, which is a team in and of itself. Therefore, it is unclear why somebody would consider it a problem that a SR is conducted within a team.

The second most commonly chosen argument against such a thesis was that SRs ‘do not produce enough new knowledge for a dissertation’. The volume of a SR largely depends on the number of included studies and the available data for numerical analyses. Therefore, it is unfair to label a SR as a priori lacking in new knowledge. There are SRs with tens or hundreds of included studies, and some of them not only include meta-analyses, but also network meta-analyses, which are highly sophisticated statistical methods. However, limiting SRs within a thesis only to those with meta-analysis would be unfair because sometimes meta-analysis is not justified due to clinical or statistical heterogeneity [ 11 ] and the presence or absence of a meta-analysis is not an indicator of the quality of a SR. Instead, there are relevant checklists for appraising methodological and reporting quality of a SR [ 12 , 13 ].

The third most commonly chosen argument against SRs within PhD theses was ‘lack of adequate training of candidates in methodology of systematic reviews’. This could refer to either insufficient formal training or insufficient mentoring. The graduate program and the mentor need to ensure that a PhD candidate receives sufficient knowledge to complete the proposed thesis topic. Successful mentoring in academic medicine requires not only commitment and interpersonal skills from both the mentor and mentee, but also a facilitating institutional environment [ 14 ]. This finding could be a result of a lack of capacity and knowledge for conducting SRs in the particular institutions where the survey was conducted, and not general opinion related to learning a research method when conducting a PhD study. Formal training in skills related to SRs and research synthesis methods [ 15 , 16 ], as well as establishing research collaborations with researchers experienced in this methodology, could alleviate this concern.

One third of the participants indicated a ‘lack of appreciation of systematic review methodology among faculty members’ as a reason against such a thesis model. This argument, as well as the prevalent negative attitude towards SRs as PhD theses, perhaps can be traced to a lack of knowledge about SR methodology; however, although the level of knowledge was quite low in our study, there was no statistically significant correlation between knowledge and negative attitudes. Of the nine questions about SR research methodology, only three questions were correctly answered by more than half of the participants. This could be a cause for concern because it has been argued that any health research should begin with a SR of the literature [ 17 ]. It has also been argued that the absence of SRs in the context of research training might severely hamper research trainees and may negatively impact the research conducted [ 18 ]. Thus, it has been recommended that SRs should be included ‘whenever appropriate, as a mandatory part of any PhD program or candidature’ [ 18 ].

It has recently been suggested that the overwhelming majority of investment in research represents an ‘avoidable waste’ [ 19 ]. Research that is not necessary harms both the public and patients, because funds are not invested where they are really necessary, and necessary research may not be conducted [ 17 ]. This is valid not only for clinical trials, but also for other types of animal and human experiments [ 20 ]. SRs can help improve the design of new experiments by relying on current evidence in the field and by helping to clarify which questions still need to be addressed. SRs can be instrumental in improving methodological quality of new experiments, providing evidence-based recommendations for research models, reducing avoidable waste, and enabling evidence-based translational research [ 20 ].

Four respondents from three institutions indicated that empty SRs are accepted as a PhD thesis. While it makes sense to include such a SR as a part of the thesis to indicate lack of evidence in a certain field, it is highly unlikely that an entire thesis can be based on an empty SR, without a single included study.

There are many advantages of a SR as a graduate thesis [ 4 , 5 ], especially as a research methodology suitable for low-resource settings. A PhD candidate can prepare a Cochrane SR as a part of the PhD thesis, yielding a high-impact publication [ 4 ]. Non-Cochrane SRs can also be published in high-impact journals. A PhD candidate involved in producing a SR within a PhD thesis goes through the same research process as those conducting primary research, from setting up a hypothesis and a research question, to development of a protocol, data collection, data analysis and appraisal, and formulation of conclusions. Graduate programs can set limits, such as the prevention of empty reviews and the recognition of updated reviews as valid for a PhD thesis, and engage experienced researchers as advisors and within thesis evaluation committees, to ensure that a candidate will conduct a high-quality SR [ 4 ]. Conducting a SR should not be mandatory, but candidates and mentors willing to produce such research within a graduate program should be allowed to do so.

Further studies in this field could provide better insight into attitudes related to SRs as graduate theses and explore interventions that can be used to change negative attitudes and improve knowledge of SRs among decision-makers in graduate education.

Raising awareness about the importance of SRs in biomedicine, the basic aspects of SR methodology and the status of SRs as original secondary research could contribute to greater acceptance of SRs as potential PhD theses. Our results can be used to create strategies that will enhance acceptance of SRs among graduate education program directors.

Gopalakrishnan S, Ganeshkumar P. Systematic reviews and meta-analysis: understanding the best evidence in primary healthcare. J. Fam. Med Prim Care. 2013;2(1):9–14.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Aveyard H, Sharp P. A beginner’s guide to evidence-based practice in health and social care. Glasgow: McGraw Open Press University; 2011.

Google Scholar

Cook DJ, Mulrow CD, Haynes RB. Systematic reviews: synthesis of best evidence for clinical decisions. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(5):376–80.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Puljak L, Sambunjak D. Cochrane systematic review as a PhD thesis: an alternative with numerous advantages. Biochemia Medica. 2010;20(3):319–2.

ten Ham-Baloyi W, Jordan P. Systematic review as a research method in post-graduate nursing education. Health SA Gesondheid. 2016;21:120–8.

Article Google Scholar

Organisation for PhD Education in Biomedicine and Health Sciences in the European System (ORPHEUS). Available at: http://www.orpheus-med.org/ .

Feinstein AR. Meta-analysis: statistical alchemy for the 21st century. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48(1):71–9.

Meerpohl JJ, Herrle F, Reinders S, Antes G, von Elm E. Scientific value of systematic reviews: survey of editors of core clinical journals. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e35732.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Biondi-Zoccai G, Lotrionte M, Landoni G, Modena MG. The rough guide to systematic reviews and meta-analyses. HSR proc intensive care cardiovascular anesth. 2011;3(3):161–73.

CAS Google Scholar

Baethge C. Publish together or perish: the increasing number of authors per article in academic journals is the consequence of a changing scientific culture. Some researchers define authorship quite loosely. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2008;105(20):380–3.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statist Med. 2002;21:1539–58.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, Porter AC, Tugwell P, Moher D, Bouter LM. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:10.

Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):72–8.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Balajic K, Barac-Latas V, Drenjancevic I, Ostojic M, Fabijanic D, Puljak L. Influence of a vertical subject on research in biomedicine and activities of the Cochrane collaboration branch on medical students’ knowledge and attitudes toward evidence-based medicine. Croat Med J. 2012;53(4):367–73.

Marusic A, Sambunjak D, Jeroncic A, Malicki M, Marusic M. No health research without education for research—experience from an integrated course in undergraduate medical curriculum. Med Teach. 2013;35(7):609.

Mahtani KR. All health researchers should begin their training by preparing at least one systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2016;109(7):264–8.

Olsson C, Ringner A, Borglin G. Including systematic reviews in PhD programmes and candidatures in nursing - ‘Hobson’s choice’? Nurse Educ Pract. 2014;14(2):102–5.

Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet. 2009;374(9683):86–9.

de Vries RB, Wever KE, Avey MT, Stephens ML, Sena ES, Leenaars M. The usefulness of systematic reviews of animal experiments for the design of preclinical and clinical studies. ILAR J. 2014;55(3):427–37.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the ORPHEUS secretariat for administering the survey and the study participants for taking time to participate in the survey. We are grateful to Prof. Ana Marušić for the critical reading of the manuscript.

This research was funded by the Croatian Science Foundation, grant no. IP-2014-09-7672 ‘Professionalism in Health Care’. The funder had no role in the design of this study or its execution and data interpretation.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed for the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Cochrane Croatia, University of Split School of Medicine, Šoltanska 2, 21000, Split, Croatia

Livia Puljak

Department for Development, Research and Health Technology Assessment, Agency for Quality and Accreditation in Health Care and Social Welfare, Planinska 13, 10000, Zagreb, Croatia

Laboratory for Pain Research, University of Split School of Medicine, Šoltanska 2, 21000, Split, Croatia

Livia Puljak & Damir Sapunar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Both authors participated in the study design, data collection and analysis and writing of the manuscript, and both read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Livia Puljak .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The Ethics Committee of the University of Split School of Medicine approved the study. All respondents consented to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:.

Online survey used in the study. Full online survey that was sent to the study participants. (PDF 293 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Puljak, L., Sapunar, D. Acceptance of a systematic review as a thesis: survey of biomedical doctoral programs in Europe. Syst Rev 6 , 253 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0653-x

Download citation

Received : 29 August 2017

Accepted : 30 November 2017

Published : 12 December 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0653-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Systematic review

- PhD program

- Biomedicine

- Study design

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Writing your thesis and conducting a literature review

- Writing your thesis

Your literature review

- Defining a research question

- Choosing where to search

- Search strings

- Limiters and filters

- Developing inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Managing your search results

- Screening, evaluating and recording

- Snowballing and grey literature

- Further information and resources

Most PhD and masters’ theses contain some form of literature review to provide the background for the research. The literature review is an essential step in the research process. A successful literature review will offer a coherent presentation and analysis of the existing research in your field, demonstrating:

- Your understanding of the subject area

- Gaps in current knowledge (that may in turn influence the direction of your research)

- Relevant methodologies

There are different approaches and methods to literature reviews, and you may have heard of terms like systematic, structured, scoping or meta-analysis. This is when the literature review becomes the research methodology in its own right, instead of forming part of the research process.

This table shows the differences between a traditional literature review and a structured or systematic literature review.

Structured vs traditional literature reviews

What is a traditional literature review?

A traditional literature review is a critical review of the literature on a particular topic. The aim of this type of literature review is to identify any background research on your topic and to evaluate the quality and relevance of the literature. You will use your literature review to understand what has already been researched, help develop your research questions and the methodology that you should follow to collect and to identify any areas that your research can explore. You want your research to be unique so you will use a literature review to prevent you duplicating any previous research but also identifying any errors or mistakes that you would want to avoid.

A literature review is aimed at Masters (MSc students) and research level.

What is a structured literature review?

A structured literature review involves bringing many research studies together to use them as the data to determine findings (known as secondary research). There is no other form of data collection involved such as creating your own surveys and questionnaires (primary research). This approach allows you to look beyond one dataset and synthesise the findings of many studies to answer your clearly formulated research question.

Sometimes a structured review can be described as being a systematic literature review. A structured review typically does not fulfil all of the criteria for a full systematic review but may take a similar approach by taking a systematic, step by step method to find literature. They tend to follow a set protocol for determining the research studies to be included and every stage is documented.

To help you prepare for your structured literature review please complete this interactive workbook.

For Logistics students only

To help you prepare for your systematic literature review please complete this interactive workbook.

What is a systematic literature review?

A systematic literature review is a specific research methodology to identify, select, evaluate, and synthesise relevant published and unpublished literature to answer a particular research question. The systematic literature review should be transparent and replicable, you should follow a predetermined set of inclusion and exclusion criteria to select studies and help minimise bias. A systematic literature review may be registered, so that others can discover and minimise duplication, and can take several years to complete.

The systematic literature review is aimed at research (PhD students) level.

Useful background reading

Cranfield Libraries have several books offering guidance on how to approach and conduct literature reviews, and structured or systematic literature reviews:

- Reading list for literature review and study skills

- Reading list of items to support a structured or systematic literature review

Looking at previous structured and systematic literature reviews is an effective way to understand what is required and how they should be structured and written up. Structured literature reviews can be found in the Masters Thesis Archive (MTA) and systematic literature reviews can be found in the Cranfield University institutional Repository, CERES. Check out the Theses link.

- << Previous: Writing your thesis

- Next: Defining a research question >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 10:52 AM

- URL: https://library.cranfield.ac.uk/writing-your-thesis

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Systematic review article, a systematic review of doctoral graduate attributes: domains and definitions.

- 1 Department of Psychology, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, South Africa

- 2 Research and Innovation, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, South Africa

Doctoral graduate attributes are the qualities, skills, and competencies that graduates possess, having completed their doctorate degree. Graduate attributes, in general, lack conceptual clarity, making the investigation into and quality assurance processes attached to doctoral outcomes challenging. As many graduate attributes are “unseen” or implicit, the full range of attributes that doctoral graduate actually possess needs to be synthesized, so that they may be recognized and utilized by educational stakeholders. The aim of this study was to establish and describe what attributes graduates from doctoral degrees possess. A systematic review of peer-reviewed, primary literature published between January 2016 and June 2021 was conducted, identifying 1668 articles. PRISMA reporting was followed, and after screening and full text critical appraisal, 35 articles remained for summation through thematic synthesis. The doctoral graduate attribute domains identified included knowledge, research skills, communication skills, organizational skills, interpersonal skills, reputation, scholarship, higher order thinking skills, personal resourcefulness, and active citizenship. Many of the domains were conceptualized as transferable or interdisciplinary, highlighting the relevance of the attributes doctoral graduates possess. The review findings align with existing frameworks yet extend those that tend to focus on generic “seen” attributes, and include a range of “unseen”, intrinsic qualities as outcomes of the doctoral degree. The review contributes to the conceptual development of doctoral graduate attributes, by synthesizing actual outcomes, as opposed to prospective attributes or attributes-in-process. Doctoral graduate attributes should be conceptualized to integrate both generic attributes alongside intrinsic qualities that are important for employability. Increased awareness as to the scope of doctoral graduate attributes among stakeholders, such as doctoral supervisors, students, graduates and employers, may facilitate improved educational outcomes and employability. Future research into the contextual relevance of the domains identified and how they are developed may be beneficial. Future research could involve the development of context-relevant scales to empirically measure doctoral graduate attributes among alumni populations, as a quality assurance outcome indicator. Such findings could inform program reform, improving the relevance of doctoral education and the employability of doctoral graduates.

Introduction

Doctoral graduate attributes are defined as the qualities or characteristics of a doctoral graduate, integrating skills, knowledge and competencies with doctoral identity ( Yazdani and Shokooh, 2018 ). Graduate attributes are of interest within the context of higher education quality assurance and the international focus on producing skilled and employable graduates ( Bitzer and Withering, 2020 ). Graduate attributes are typically defined institutionally and embedded in curriculum learning outcomes ( Bridgstock, 2009 ; Mashiyi, 2015 ). However, doctoral degrees often lack a standardized curriculum, with the primary focus being original research under supervision ( Elliot et al., 2016 ; Molla and Cuthbert, 2016 ), leaving no formal frame into which doctoral graduate attributes may be embedded. The transferability of graduate attributes is an important consideration for higher education institutions, so that the attributes instilled are relevant to multiple work contexts, enhancing graduate employability ( Kensington-Miller et al., 2018 ). This is particularly relevant in the context of doctoral education, with the shift away from the thesis as the primary outcome, and the increased demand for transferable skills to the increasingly competitive world of work ( Denicolo and Reeves, 2014 ). Doctoral graduate attributes, as outcomes of doctoral education, are important to consider for quality assurance, the employability of graduates, and the relevance of doctoral education.

Graduate attributes are generally critiqued as lacking conceptual clarity ( Mowbray and Halse, 2010 ; Bitzer and Withering, 2020 ). This conceptual ambiguity is reflected in the “range of adjectives such as “transferable”, “generic”, “soft”, “key”, “graduate” and “employability” [that] have been diversely paired with nouns such as “skills”, “attributes”, “outcomes” and “capabilities”” ( Kensington-Miller et al., 2018 , p. 1440). In short, the following differentiations between terms may be made: “competence” is a performance-based term, referring to successful or efficient performance whereas “competencies” refers to the knowledge and behaviors that, if utilized effectively, result in competent performance ( Potolea, 2013 ; Durette et al., 2016 ). “Skills” are typically learned abilities or expertise, but can be more broadly defined to include “the acquisition or development of specific capacities, abilities, aptitudes or competencies” ( Gilbert et al., 2004 , as cited by Mowbray and Halse, 2010 , p. 655). “Attributes” refers to the inherent characteristics or features of someone or something. By extension, doctoral graduate attributes would be the features or characteristics of doctoral graduates, and may thus be an umbrella term that integrates skills, knowledge and competencies, as expressed by Yazdani and Shokooh (2018) . This definition allows for the multidimensional and interrelated nature of the qualities and skills doctoral graduates possess ( Mowbray and Halse, 2010 ).

Measuring graduate attributes is complicated, partly due to the conceptual ambiguity noted. Graduate attributes are typically developed longitudinally, making them challenging to operationalize, and context dependent, limiting the generalizability of scales ( Hughes and Barrie, 2010 ; Cavanagh et al., 2015 ; Nell and Bosman, 2017 ). Graduate attributes often include a combination of skills, dispositions, values, and competencies that may be more abstract and difficult to quantify ( Hinchliffe and Jolly, 2011 ). Many graduate attributes are “unseen” or “invisible” as they may reflect the qualities of the person, and are not as explicit as those clearly embedded in the curriculum or formal degree processes ( Kensington-Miller et al., 2018 ). These “invisible” attributes are often implied, yet are important to consider for a graduates' overall profile, such as resilience ( Kensington-Miller et al., 2018 ). It is important to synthesize evidence on what attributes doctoral graduates actually do possess, in order to reconsider the scope of what is included in traditional lists of doctoral graduate attributes. In so doing, due consideration may be given to the “unseen” attributes that are outcomes of the doctoral degree. The notion of implicit attributes in parallel to those explicit to the “product” of the degree, aligns with the shift of focus in doctoral education from focusing exclusively on the production of the doctoral thesis, to include the holistic development and tacit learning involved in the doctoral journey ( Mowbray and Halse, 2010 ; Yazdani and Shokooh, 2018 ). Despite the challenges associated with conceptualizing graduate attributes, they remain pertinent to assess ( Bitzer and Withering, 2020 ).

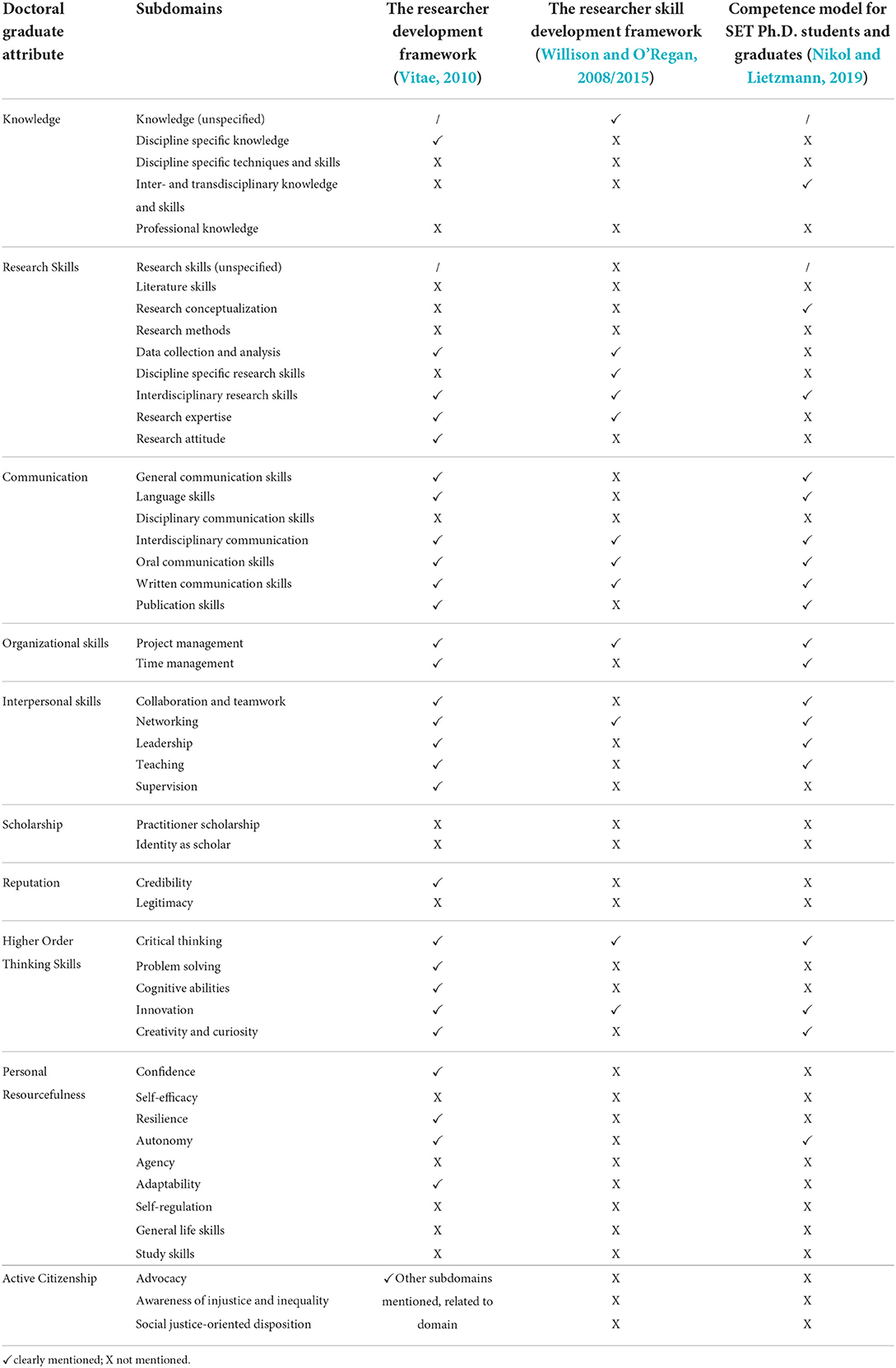

There has been significant investment in improving postgraduate education, including the implementation of transferable skills development, particularly in the Global North ( Denicolo and Reeves, 2014 ). This has given rise to various models and frameworks related to researcher attributes and doctoral competencies. One of the most widely used frameworks, particularly in the United Kingdom, is the Researcher Development Framework ( Vitae, 2010 ). According to Reeves et al. (2012 , p. 4), “the purpose of the framework is to support the development of individual researchers while enhancing our capacity to build a workforce of world-class researchers within the UK higher education research base.” As such, it can be used to facilitate qualitative reflection on one's development, and encompasses a wider view of researcher career progression, beyond the doctorate degree. Similarly, the Researcher Skill Development Framework ( Willison and O'Regan, 2008/2015 ), developed in the Australian context, provides a developmental framework of research-related skills and agency, from first year undergraduate studies to established academics. The framework includes a qualitative matrix that may be well suited for developmental use in the context of doctoral supervision, or for curriculum development, rather than as an outcome indicator. The competence model for science, engineering and technology (SET) Ph.D. students and graduates ( Nikol and Lietzmann, 2019 ), in the broader European context, pertains to the doctorate, yet is focused on SET disciplines only and is curriculum focused, rather than outcomes focused. Notably, all of the above frameworks were developed in the Global North. In general, these models have been used with focus on the development of doctoral education and training, including formal curriculum and transferable skills development programs. They are well suited to use for personal, qualitative reflection on one's skill development. In the South African context, the Council for Higher Education ( CHE, 2018 ) has compiled the qualification standards for doctoral degrees, including a prospective list of graduate attributes, with five knowledge and four skill domains. However, these domains are not theoretically defined or clearly operationalized.

The Researcher Development Framework was validated prior to its launch in 2011 ( Reeves et al., 2012 ). Since then, there has been extensive ongoing work in the field of doctoral education and efforts to develop context and field specific models, such as CHE (2018) and Nikol and Lietzmann (2019) . Further, many institutional or governmental frameworks are aspirational ideals of the attributes institutions hope graduates will possess ( Kensington-Miller et al., 2018 ) that do not necessarily reflect the attributes that graduates actually do possess when they graduate. As such, there is a need to identify what recent evidence there is of the attributes doctoral graduates possess after completing their doctorate degrees. The focus of the models above aligns with the typical focus of doctoral education evaluation: the doctoral process and student experiences during the doctorate ( Luo et al., 2018 ). However, doctoral graduate attributes also need to be conceptualized as outcomes, rather than prospective qualities, in order to facilitate good, empirical quality assurance ( Harley, 2020 ). Therefore, the target population for evaluating graduate attributes as outcomes should be graduates who have completed their degree. As noted by Durette et al. (2016 , p. 1356):

Ph.D. students might not be the adequate population to study competencies developed during doctoral training since (1) they have not finished it entirely and (2) Ph.D. students might not be well aware of the competencies they have developed… in particular because they have not had the opportunity to exercise these competencies in other professional contexts.

There is a need to consolidate evidence of doctoral graduate attributes from the perspective of graduates only, excluding student populations. In so doing, a synthesis of the doctoral graduate attributes as outcomes, once the doctorate has been completed, may be possible. This may give preliminary indications of the extent to which developmental models used in curriculum and personal development, such as those identified above, have translated into real outcomes for doctoral graduates.

Limited empirical research exists attempting to synthesize graduate attributes ( Bridgstock, 2009 ). The Researcher Development Framework is an example of extensive work toward synthesizing doctoral graduate attributes ( Reeves et al., 2012 ). A recent example is the conceptual analysis of “doctorateness” by Yazdani and Shokooh (2018) that included literature published between 1995 and 2016. While the study appears to follow some review processes, it does not reflect the rigor required of a systematic review ( Page et al., 2021 ). The article provides a synthesis of “doctorateness” as a concept, however, the findings were limited to broad categories of attributes, without definitions or detail as to what these domains entail. Further, much literature has been published since 2016 that warrants consideration. Therefore, there is a gap in the consolidation of more recent literature that bears global evidence of the attributes that doctoral graduates possess.

The aim of this review was to establish and describe what attributes graduates from doctoral degrees possess, through a systematic review of recent, high-quality research literature. The objectives of the review were: (1) to identify doctoral graduate attribute domains and sub-domains, and (2) to clarify their theoretical and/or operational definitions.

Study design

A systematic review is a rigorous, systematic process used to filter and synthesize available evidence on a topic ( Laher and Hassem, 2020 ). There is a need to filter evidence to focus on a specific perspective, i.e., that of doctoral graduates, to the exclusion of doctoral students, in order to consolidate recent evidence of what attributes doctoral graduates actually possess, specifically focusing on the conceptualization of doctoral graduate attributes as outcomes of the doctoral degree. A systematic review is a suitable method to filter the available evidence and synthesize the various definitions and iterations of doctoral graduate attributes. Systematic reviews are recommended for use in scale development, as part of identifying and clarifying the scale construct ( Munnik and Smith, 2019 ), and thus are a suitable method for facilitating conceptual clarity of a constructs, such as graduate attributes.

Review question

The systematic review question was: what attributes do graduates from doctoral degrees possess? The formulation of PEO (population, exposure and outcome) was used ( Moola et al., 2020 ), with doctoral graduates as the population, the doctoral degree as the exposure, and doctoral graduate attributes being the outcome.

Eligibility

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were set a priori , to systematically determine which articles to include ( Gough et al., 2017 ). Articles had to meet the following criteria to be eligible for inclusion:

1. The participants were graduates from doctoral degree programs (any discipline, no geographic limitation, no specified timeframe since graduation);

2. A clear focus on the attributes of doctoral graduates must be present (e.g., skills, competencies, abilities);

3. Qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods research were considered; and

4. Published between January 2016 and June 2021, to ensure that recent literature on the topic was included.

Articles were excluded if they were not published and peer reviewed. Gray literature, such as theses and conference proceedings, were excluded. Articles that were not accessible in full text and in English were excluded. The University of the Western Cape (UWC) library assisted in locating full text and English translations, where necessary.

Information sources

Databases were accessed through uKwazi, a composite search function available through the UWC library. Databases included: Academic Search Complete, Directory of Open Access Journals, EBSCOhost, Emerald Journals, JSTOR, Sabinet, SAGE, Springer, Taylor and Francis, and Wiley. The use of uKwazi allowed for a comprehensive, composite search of all databases simultaneously, using the same search terms and limiters, thus enhancing the systematic nature of the review. The use of this platform automatically excluded duplicate articles, streamlining the screening process.

Search strategy

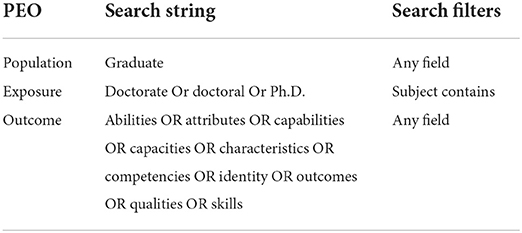

The PEO model was used to develop search strings, as shown in Table 1 . The population of interest was doctoral graduates who completed their degree, thus excluding students, as the focus was specifically on attributes as outcomes. The term “graduate” was used to ensure specificity, as the inclusion of “student” would have resulted in too wide a search. The search terms related to exposure referred to the pursuit of the doctoral degree and was intentionally general to include various formats of doctoral degree study. The search terms included “doctorate OR doctoral OR Ph.D.”, which would include any combination of fields of study, for example, professional doctorate, Doctor of Education, or Doctor of Philosophy. This was intentionally kept broad, as many studies did not specify what kind of doctorate was reported on or included mixed groupings from various types of doctorates. The outcome of doctorate graduate attributes, for which the search string was kept general, to include various iterations of nouns used in relation to doctoral graduate attributes.

Table 1 . Search strategy.

The search strings were compiled into a Boolean phrase, as indicated in Table 1 that was entered into uKwazi for a composite search of all databases simultaneously. The first and third strings were searched in all fields, to include titles, abstract and subject. The second string was searched only in the subject field, to exclude irrelevant articles that were included in the search due to the authors' credentials (e.g., Ph.D.). The composite search was limited to include only articles, available in English, peer reviewed, with full text available online, and published between 2016 and 2021—in alignment with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. These limiters were applied on the search platform as part of the search process, prior to recording the search results.

A second search, using the single search term “doctorateness” (any field) was conducted through uKwazi. The same limiters were applied. The supplementary search was conducted to ensure that potentially relevant articles were not unintentionally excluded.

Study selection

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) was followed to ensure methodological rigor and transparency in reporting ( Page et al., 2021 ). The citation information of each article identified in the search was imported into Rayyan, an online systematic review platform ( Ouzzani et al., 2016 ). Rayyan was utilized to streamline the review process and enhance reporting, as it facilitated dual review and tracking of exclusion reasons. Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts for relevance against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles that did not meet all the inclusion criteria or met at least one of the exclusion criteria were excluded. The full texts of all remaining articles were retrieved and screened for eligibility, against the inclusion criteria. Reviewers independently screened each article, noting reasons for inclusion or exclusion. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Quality appraisal tool

The methodological quality of the remaining articles was assessed through the Smith, Franciscus and Swartbooi (SFS) full text critical appraisal tool, version E ( Smith et al., 2015 ). The tool includes three sections: (A) purpose, including problem statement, literature and theoretical framework (22 points); (B) methodological rigor, including design, sampling, data collection, data analysis, results, discussion and conclusion (52 points); and (C), general considerations of publication and peer review status (5 points). A minimum threshold score of 60% (strong to excellent quality) was set that must be met for inclusion in the review ( Smith et al., 2015 ), to ensure that only high quality research was included. The critical appraisals were independently conducted by two reviewers. Articles with scores that differed by five or more points were reviewed through discussion ( n = 4), until consensus was reached.

Data extraction and synthesis

A self-developed data extraction table was used to extract descriptive data (location, design, sample etc.) and analytic information relating to the doctoral graduate attribute domains and definitions. The review findings were analyzed using thematic synthesis ( Gough et al., 2017 ). Thematic synthesis is the equivalent of thematic analysis in primary research, and follows a similar process of coding and theme development ( Gough et al., 2017 ). The coding process employed was selective, focusing primarily on the findings reported ( Gough et al., 2017 ), for example, the attributes doctoral graduates indicated they possessed after having completed their studies. A hybrid inductive-deductive approach was used, with a primarily inductive approach was used for the initial coding, with codes emerging from the text ( Xu and Zammit, 2020 ). A deductive approach was utilized for subsequent readings of the articles, to identify potential codes that may have been overlooked in the initial coding, and for theme development to group the codes into subdomains and domains. The deductive approach drew on existing literature related to doctoral graduate attributes, such as Vitae (2010) , Yazdani and Shokooh (2018) , and Nikol and Lietzmann (2019) . In order to compare the findings of the review to existing models, selected frameworks were coded, using a deductive approach, to facilitate mapping against the domains and subdomains identified in the review. In some instances, the detail of descriptions differed, and so it was not always possible to map to the models exactly.

Ethics considerations

This review is part of a broader study, which obtained ethics clearance from the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee at UWC (HS21/7/19). Secondary data collection in the form of a systematic review does not require consent. However, consideration of the ethical practice and quality of each article under review, through critical appraisal, ensured the quality of the review findings. The authors of the original work were appropriately cited, so that there was no infringement on intellectual property or copyright. Only sources available in the public domain were utilized, and those that the researchers had legal access to through their institution. Furthermore, permission for the use of the SFS critical appraisal tool was obtained from the author.

The findings of the review include the outcome of the study selection process, the quality appraisal of articles, the descriptive characteristics of the studies in the review, and the doctoral graduate attributes domains, subdomains and descriptions that were identified.

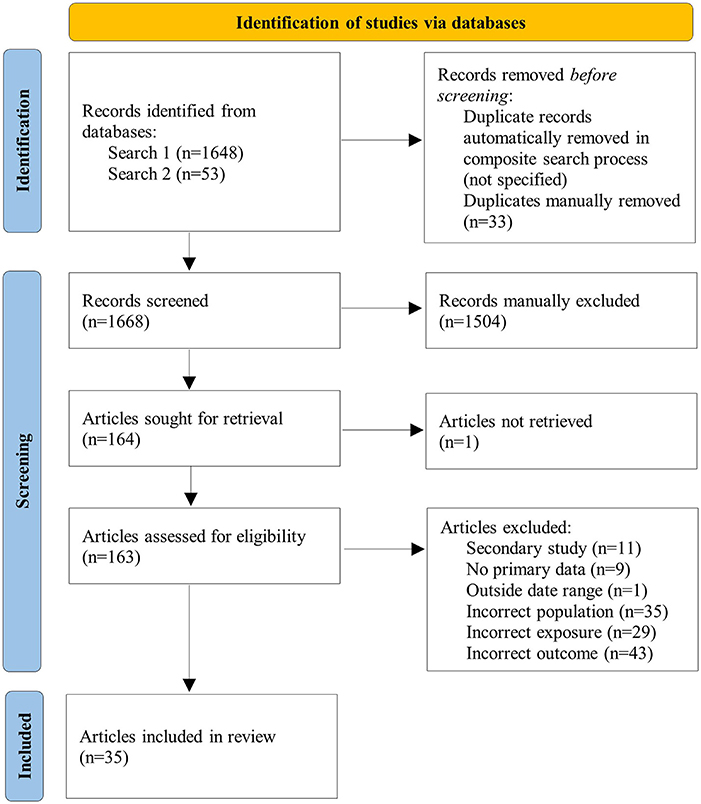

Process results

A total of 1,701 articles were identified in the review ( Figure 1 ). Duplicates were automatically excluded in the comprehensive, integrated search through uKwazi. Duplicates between searches one and two were manually removed ( n = 33). Studies were manually excluded if they were secondary studies (e.g., reviews; secondary analysis), did not include reporting on primary data (e.g., letter to editor; theoretical papers), were outside of the publication range (first published prior to January 2016 or after June 2021); included the incorrect population (graduates from other degree levels; Ph.D. student populations without any Ph.D. graduates represented; or did not allow for differentiation between graduates and students); the incorrect exposure (e.g., did not explicitly relate to the Ph.D.); or the incorrect outcome (e.g., focus on doctoral experience or attributes needed for completion, without explicit mention of attributes possessed on completion). A total of 35 articles met all criteria and were included in the review.

Figure 1 . PRISMA flowchart of data collection and screening [Adapted from Page et al. (2021) ].

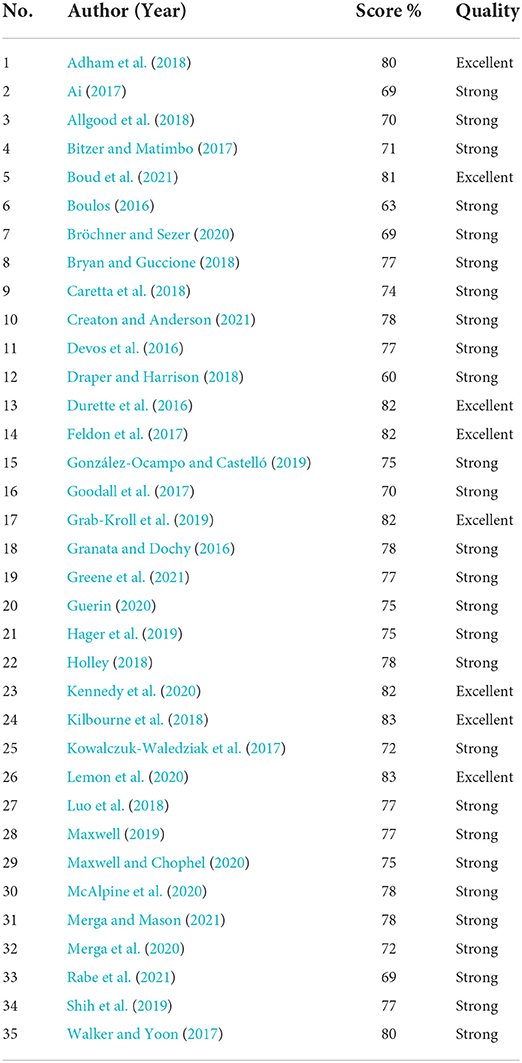

Quality appraisal results

All studies included in the review ( n = 35) exceeded the threshold score of 60% in the quality appraisal stage ( Table 2 ), and thus had strong to excellent methodological quality ( Smith et al., 2015 ). A common methodological gap identified in articles through the appraisal was not reporting on the analysis methods used ( n = 18). The focus of the review was on the domains relating to doctoral graduate attributes covered, so the actual results of the studies under review were not the primary focus. Further, the review was descriptive, thus the goal was not generalizability. There was sufficient evidence of methodological quality in the articles included for synthesis.

Table 2 . Quality appraisal scores of included articles.

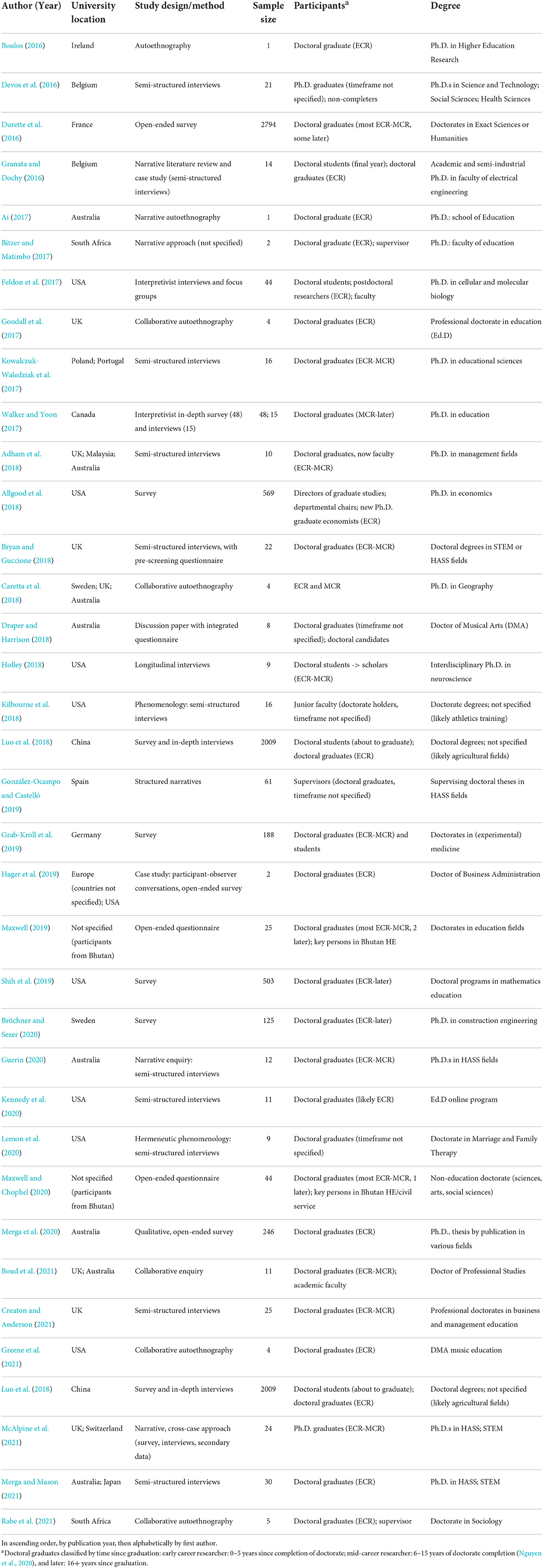

Study characteristics

The studies included in the review ( n = 35) represented various universities internationally ( Table 3 ). Graduates from universities in the United States of America (USA) ( n = 9), Australia ( n = 8), and the United Kingdom (UK) ( n = 7) were most strongly represented. Graduates from universities across Europe (Belgium, France, Germany, Ireland, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK), North America (USA and Canada); Asia (Bhutan, China, Japan, and Malaysia), and Africa (South Africa) were represented. Most studies focused on a single country ( n = 28), if not a single university within that country. Cross-country comparisons were evident in seven studies. The studies reflected greater representation of graduates from institutions in the USA, Australia and the UK. This aligns with the USA and UK being among the top producers of doctoral graduates among Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries ( OECD, 2019 ). There was low representation of graduates from universities in Asia, yet there has been noted growth in doctoral enrolments in China specifically since the early 2000s ( Luo et al., 2018 ). While there was lower representation of graduates from African institutions, it is unsurprising that the two studies included represented graduates from South African institutions, as there has been significant local investment in doctoral education in recent years, and South African higher education institutions attract doctoral students from various African countries ( Molla and Cuthbert, 2016 ). There was no representation of graduates from institutions in the Middle East or South America. Due to increased trends of mobility and internationalization in higher education ( OECD, 2019 ), it is likely that doctoral graduates from various nationalities were represented in the study, however, the nationalities of graduates were not consistently reported on.

Table 3 . Study characteristics.

The articles under review reported various methodologies, primarily interviews ( n = 13), surveys ( n = 11) or autoethnographies ( n = 7). Sample sizes ranged from 1 ( Boulos, 2016 ; Ai, 2017 ) to 2794 ( Durette et al., 2016 ). According to the inclusion criteria, all studies included doctoral graduates. In Table 3 , the graduate samples were classified as early career researchers (ECR) who graduated within the 5 years, mid-career researchers (MCR) who graduated between 6 and 15 years prior ( Nguyen et al., 2020 ), and those who graduated more than 15 years prior. Studies focused primarily on ECR and MCR. Samples of only doctoral graduates were most common ( n = 23). Mixed populations were included, where differentiation of the perspectives of graduates from other participants was possible. Some studies included faculty, supervisors, key persons in higher education, doctoral students and non-completers as participants. Most studies focused on a specific degree ( n = 26), with education-related fields having the highest frequency ( n = 10). The remaining studies ( n = 9) included cross-disciplinary samples of doctoral degrees in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) and humanities, arts, and social sciences (HASS). There was a range of disciplines and fields represented, with good representation of both HASS and STEM fields. In half of the studies ( n = 17), the doctoral degrees reported on were Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.). Professional doctorates were specified in a fifth of the articles ( n = 7), indicated by “Doctor of [field name]”, for example “Doctor of Education” or “Ed.D”. The remaining articles did not specify if it was a Ph.D. or professional doctorate ( n = 11). Given the greater prevalence of Ph.D. programs in comparison to professional doctorate programs, this may demonstrate good representation of both degree types. Neither type of doctorate nor field of study were gaps in the review. There were no notable trends in the type of doctorate, field of study, geographic location and emerging domains.

Scalar information on subscale(s) measuring dimensions related to doctoral graduate attributes were reported in six studies. Subscales addressing teaching ( Allgood et al., 2018 ; Shih et al., 2019 ) and research skills ( Luo et al., 2018 ; Shih et al., 2019 ) were used in two studies each. Subscales of general scientific competencies ( Grab-Kroll et al., 2019 ), and universal skills ( Luo et al., 2018 ) were identified. Two other studies ( Walker and Yoon, 2017 ; Bröchner and Sezer, 2020 ) provided nominal information on the scales utilized, with insufficient detail to identify what domains were covered. The scales were either adapted from other studies ( Allgood et al., 2018 ; Shih et al., 2019 ; Bröchner and Sezer, 2020 ), or self-developed for the study ( Walker and Yoon, 2017 ; Luo et al., 2018 ; Grab-Kroll et al., 2019 ). Shih et al. (2019) was the only study to report on psychometric properties. Where information was available, subscales had between 2 and 13 items per domain. Items were most often in Likert scale format ( Allgood et al., 2018 ; Luo et al., 2018 ; Grab-Kroll et al., 2019 ; Shih et al., 2019 ). Other formats used included continuous scales ( Bröchner and Sezer, 2020 ) and multiple-choice formats ( Walker and Yoon, 2017 ).

Doctoral graduate attributes

The studies under review rarely defined or mentioned doctoral graduate attributes explicitly, referring more often to the impact of the doctorate or the experiences of doctoral graduates. Related terms, such as competence, competency and competencies were noted. Greene et al. (2021) defined competence as “knowing negotiated within a single community of practice” (p. 95), suggesting that competence is context specific. Durette et al. (2016) defined competency by differentiating between the output, competent performance, and input—the “underlying attributes required for a person to achieve competent performance” ( Hoffmann, 1999 , as cited by Durette et al., 2016 , p. 1356). Durette et al. (2016) further defined competencies as “the resources available to doctorate holders to act competently” (p.1357). While these definitions differ, they all point to the definition of doctoral graduate attributes adopted for this study, which includes the qualities, skills, and competencies that doctoral graduates possess. Interestingly, of the frameworks and models identified previously, only two articles mentioned the Researcher Development Framework ( Bryan and Guccione, 2018 ; Creaton and Anderson, 2021 ), and this was in the introduction of the articles. These articles were two of the seven articles reflecting research conducted in the UK context, where the Researcher Development Framework was developed. As such, is appears that none of the articles under review explicitly drew on the conceptual and theoretical development that is evidenced in the existing models.

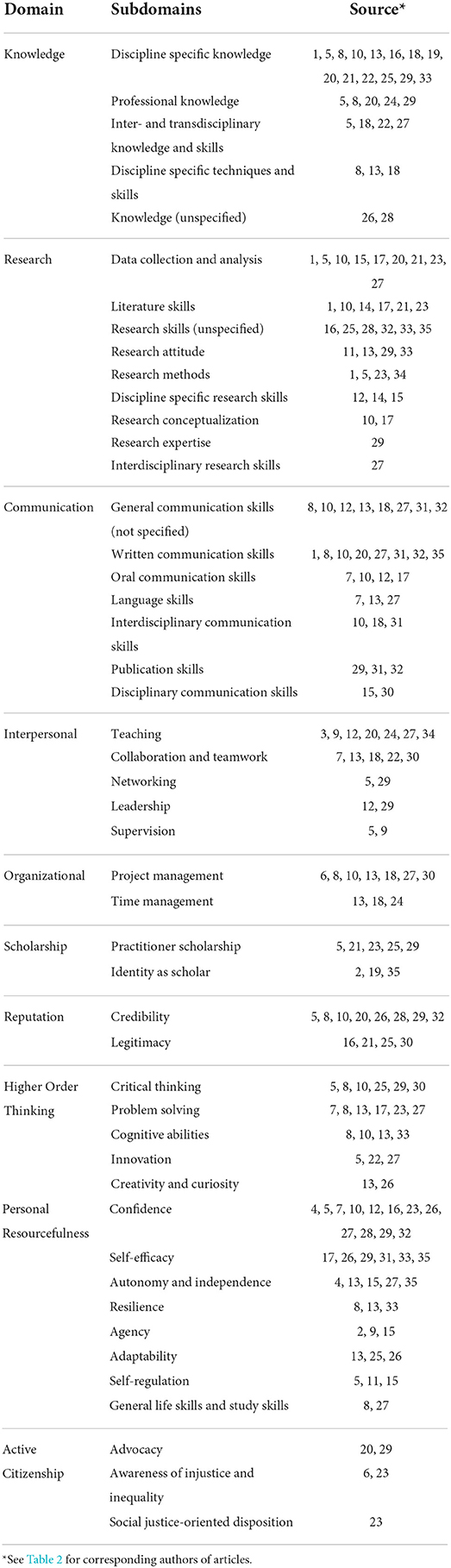

The studies addressed a wide range of doctoral graduate attributes identified as outcomes of the doctoral degrees mentioned in the studies. The domains include: knowledge, research, communication, organizational skills, interpersonal skills, scholarship, reputation, higher order thinking skills, personal resourcefulness, and active citizenship ( Table 4 ). Theoretical definitions of the actual domains identified in the studies were sparse, lacking theoretical or conceptual frameworks. These definitions were more general and process-oriented, not linked to a specific domain. Theoretical definitions for the identified domains and/or subdomains are provided, where available. Thereafter, descriptions of what these attributes entail are provided, i.e., how they may be operationalized.

Table 4 . Doctoral graduate attributes domains and subdomains.

The first domain of “knowledge” included codes that related to the knowledge doctoral graduates possessed ( n = 18). This excluded knowledge that explicitly related to “research”, as these were included under a subsequent domain. There was no explicit definition of “knowledge” in the articles under review. However, Adham et al. (2018) made reference to explicit and tacit knowledge, differentiating between knowledge that can be communicated or shared with others, and knowledge that is not as easily communicated. Knowledge development was defined as the processing of information within the individuals' “foundations, understanding, experience and beliefs” ( Adham et al., 2018 , p. 813). The various types of knowledge that doctoral graduates possessed were grouped into the following subdomains: discipline specific knowledge, interdisciplinary knowledge, and professional knowledge. In some instances, doctoral graduates were vaguely noted to possess “knowledge”, with no further explanation of what type of knowledge was indicated ( n = 2). In some studies, doctoral graduates were found to possess discipline specific knowledge, referring to the breadth and depth of their disciplinary knowledge base. Studies found that doctoral graduates' disciplinary expertise included the theoretical knowledge ( n = 14) and practical or technical skills of their discipline ( n = 3). Both their research and coursework were noted as sources of these forms of knowledge. In some instances, doctoral graduates had interdisciplinary knowledge from related or complementary disciplines ( n = 4), and had a unique and/or holistic perspective. Interdisciplinarity was defined as “integrating knowledge from two or more disciplines” ( Holley, 2018 , p. 107). Some studies found that doctoral graduates possessed professional knowledge relating to navigating the administrative and operational functioning of higher education institutions and/or work environment ( n = 5). The domain of knowledge, as a doctoral graduate attribute, thus includes subdomains of disciplinary and interdisciplinary knowledge, and professional knowledge.

Research skills

The domain of “research” included all codes that reflected skills utilized in the various stages of research, and included competencies related to research methods and processes, and attitudes related to research ( n = 21). This was labeled as the domain of research skills. There were no theoretical definitions related to research skills provided in the articles under review. In some instances, research skills were generally mentioned, without specific description ( n = 6). Studies identified that doctoral graduates were noted to possess skills related to the various stages of research: literature review ( n = 6), conceptualization ( n = 2), methods ( n = 4), and/or data collection and analysis ( n = 9). Literature skills reflected their ability to search, critically evaluate, synthesize, and write a literature review. Skills related to conceptualization included the ability to formulate research hypotheses, understand research ethics, and select suitable methods. Research methods included the knowledge of methods, and the ability to conduct quantitative and/or qualitative research. Data collection and data analysis skills included the context-relevant use of quantitative and/or qualitative data collection and data analysis methods. Consideration of discipline-specific methods skills ( n = 3), such as designing appropriate experimental controls, and the reflexive process of artistic research, and interdisciplinary research skills were noted ( n = 1). Doctoral graduates were noted to possess research expertise ( n = 1), and a research attitude ( n = 4) denoted by a respect for knowledge, a broadened outlook, research ownership and rigor. The domain of research skills that doctoral graduates possess included subdomains of range of methodological competencies, from conceptualization to data analysis, as well as research attitude and research expertise.

Communication skills

The domain of “communication” included codes that referenced various formats and forms of communication ( n = 16). There was no evidence of theoretical definitions of communication skills. In some studies, doctoral graduates were noted to possess language skills ( n = 3), and were articulate and confident in their communication skills ( n = 8). The written communication skills doctoral graduates possessed ( n = 8) included academic, scientific and technical writing skills, and being able to construct persuasive arguments. These writing skills ( n = 8) were utilized for various purposes and formats of written documents. Further, it was found that doctoral graduates possessed confidence in their written skills. Doctoral graduates' publication skills ( n = 3) were differentiated from their general writing skills, as this included knowledge of the journal landscape and publication process, and the skills to prepare an article, work with co-authors, negotiate and manage the publication process, and deal with rejection and reviewer feedback. Doctoral graduates possessed oral communication skills ( n = 4), including general presentation skills, and the dissemination of research findings through the presentation of scientific content. As with the domain of knowledge, some studies indicated that doctoral graduates possessed discipline specific communication skills ( n = 2), such as interviewing skills, and interdisciplinary communication skills ( n = 3), in their ability to communicate with non-academic audiences and produce non-academic outputs. The interdisciplinary nature of these communication skills is linked to the concept of research translation, that is defined as the “multidirectional nature of knowledge exchange between researchers and end-users” ( Merga and Mason, 2021 , p. 673). Communication skills as a domain thus included various modes and formats of communication, reflected in the subdomains.

Organizational skills

The domain of “organizational skills” reflects the skills that were learnt through managing the thesis project ( n = 8). In some studies, doctoral graduates possessed organizational skills, including project management and time management. Project management was defined as a transferable skill, that is developed “through a range of experiences… [as students] learned to determine priorities and achieve deadlines, became skillful in producing outcomes despite a limited budget, equipment failures or administrative impediment” ( Mowbray and Halse, 2010 , p. 661). Studies indicated that doctoral graduates were able to manage and run projects, and demonstrated coordinating skills, people skills, and goal-directed vision ( n = 7). Doctoral graduates possessed time management skills ( n = 3), being able to plan, work to deadlines and balance responsibilities. The organizational skills domain included subdomains of organizational and management skills at both a project and personal level.

Interpersonal skills

Interpersonal skills as a domain reflects a group of attributes that relate to interpersonal interaction in some form or another ( n = 14). Doctoral graduates possessed a range of interpersonal skills including collaboration and teamwork, networking, leadership, teaching and supervision. Collaboration was defined as “any type of joint effort of two or more people pursuing a common goal” ( Granata and Dochy, 2016 , p. 998). Collaboration and teamwork ( n = 5) were identified as being transferable skills. Doctoral graduates in the studies were able to demonstrate internal and external collaboration and teamwork, with clients, experts and industry. This involved the ability to work with people from different sectors and across research boundaries, including “working daily with close colleagues, data exchange with external partners and joint publications of findings with researchers in other faculties and universities” ( Granata and Dochy, 2016 , p. 998). Some doctoral graduates were able to network and connect with the scientific community ( n = 2), resulting in access to resources and information. Other studies highlighted that doctoral graduates demonstrated leadership capacity ( n = 2), which was cross-cutting of some other domains, including articulate communication skills (both written and verbal), the ability to work within structure, discipline of thought, investment in research, and university visibility through publication and collaboration. Doctoral graduates in some studies were noted to possess teaching skills ( n = 7), including being prepared to teach, the ability to deal with students, teaching at undergraduate level and facilitating groups effectively, and supervision skills ( n = 2) at under- and/or post-graduate level. The domain of interpersonal skills that doctoral graduates possessed, included subdomains that reflect various skills for collaborative engagement with others, for work, research and teaching.

Scholarship