Crisis management process for project-based organizations

International Journal of Managing Projects in Business

ISSN : 1753-8378

Article publication date: 30 May 2023

Issue publication date: 18 December 2023

The purpose of this paper is to study the crisis management process for project-based organizations (PBOs) by developing a comprehensive model and propositions.

Design/methodology/approach

This paper is based on a conceptual study. A literature review is considered a primary source for studying contemporary research, including 171 publications in total, which embody qualitative, quantitative, conceptual and theoretical studies. For data analysis, content analysis is used, which is comprised of descriptive and thematic analysis.

This study identifies five imperative elements of crisis management for PBOs which include (1) sense-making (information gathering and crisis interpretation), (2) decision-making (accurate and timely decision), (3) response (reactive response), (4) outcome (success/failure) and (5) learning. Based on these findings, this study proposes an integrative model of the interplay between sense-making, decision-making, response, outcome and learning. Furthermore, the findings lead to propositions for each of the elements. The paper contributes to the literature on dynamic capability theory.

Originality/value

This paper explores the crisis management process for PBOs. The proposed model deepens the understanding of the practices and processes of project-based crisis management.

- Crisis management

Sense-making

Decision-making, project-based organizations.

Iftikhar, R. , Majeed, M. and Drouin, N. (2023), "Crisis management process for project-based organizations", International Journal of Managing Projects in Business , Vol. 16 No. 8, pp. 100-125. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMPB-10-2020-0306

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2023, Rehab Iftikhar, Mehwish Majeed and Nathalie Drouin

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Introduction

The research on crises started to develop in the 1960s and 1970s, particularly in the fields of psychology, sociology and disaster response ( Jaques, 2009 ). It is generally accepted that a crisis is an unexpected event for which there are no contingency plans in place ( Hermann, 1963 ). Some of the major characteristics of a crisis are that it is an unforeseen, immeasurable, unknown and unplanned event ( Seeger, 2002 ; Oh et al. , 2013 ). A crisis is considered as “a low-probability, high impact event” ( Pearson and Clair, 1998 , as cited in Wilding and Paraskevas, 2006 ; Oh et al. , 2013 ; Iftikhar and Müller, 2019 ). Typically, a crisis is seen as a negative phenomenon, an event that threatens the organization ( Valackiene, 2011 ). In addition, crises can degrade organizational performance ( Scott, 1987 ); project-based organizations (PBOs) are no exception to this. Any organization, including PBOs in both the private and public sectors, does not want to fail and cannot afford poor performance ( Zeyanalian et al. , 2013 ). Despite the significance of crises for PBOs, surprisingly little research has been carried out so far ( Loosemore, 2000 ; Loosemore and Teo, 2000 ). Given the lack of research and the importance of the topic ( Hällgren and Wilson, 2008 ), it is clearly important to study how PBOs manage crises.

As mentioned above, crises in project settings are rarely discussed ( Hällgren and Wilson, 2011 ). A more neutral term of risk is used interchangeably with crisis ( Meyer et al. , 2002 ; Geraldi et al. , 2010 ; Iftikhar and Müller, 2019 ). Risk is “identifiable” ( Sicotte and Bourgault, 2008 , p. 468), involving foreseen and known events, which can be managed, but no one knows when they will occur ( Knight, 1921 ; Meyer et al. , 2002 ). Risk contains the property of the known-unknown, which means it is identifiable, but it is not possible to find out if exactly it will occur. Risk is measurable, predictable and manageable ( Knight, 1921 ). However, a crisis is an unforeseen, unmeasurable and unpredictable event ( Seeger, 2002 ). Crisis is commonly described as an unanticipated, surprising and ambiguous event posing a significant threat, leaving only a short decision time ( Hermann, 1963 ; Pearson and Clair, 1998 ). According to Iftikhar and Müller (2019) , risk is a potential future event, characterized by a certain probability of occurrence and, if it occurs, leading to negative consequences. Unlike crises, contingencies can be planned for risks, whereas a crisis is a threat with a high level of uncertainty with no contingency plan. This difference places emphasis on crisis management as crisis contains an element of surprise and required prompt decision-making.

Crisis management is a systematic process (step-wise approach) by which an organization attempts to effectively identify potential crises that an organization may encounter and plan how to manage them in such a way as to minimize the effects of the crisis ( Pearson and Clair, 1998 ; Gonzalez-Herrero and Smith, 2010 ; Ulmer et al. , 2017 ). The objective of crisis management is to avoid or minimize the negative impact of a crisis on an organization and its objectives ( Gonzalez-Herrero and Smith, 2010 ). It is an attempt to avoid or manage crisis events ( Pearson and Clair, 1998 ) that disturb the entire organization and concern the survival and durability of an organization. There are different crisis management approaches involved in the process, such as preparing, identifying and planning to respond to and resolve the crisis ( Ponis and Koronis, 2012 ). Coombs (1999) suggests a crisis management model which is based on prevention (detecting warning signals and taking action to mitigate the crisis), preparation (developing a crisis plan), response (trying to return to normal routines) and revision (determining what was done right). However, the common attributes of crisis management are the identification of crisis types and sources; responses to crises; and recovery from damage ( Ponis and Koronis, 2012 ). Researchers are of the view that the crisis management process should be divided into different stages. For instance, Mitroff et al. (1987) , Pearson and Mitroff (1993) and Mitroff (1994) proposed five phases of crisis management: signal detection (detecting early warning signals and then preparing for the crisis), preparation (trying to reduce the potential harm of a known crisis including developing crisis teams, training and exercises), damage containment (intended to limit the effects of the crisis, restraining parts of the organization or environment), recovery (fixing the damage caused by the crisis, trying to go back to normal business operation as soon as possible), followed by learning (the organization should examine what happened before, during and after the crisis and then identify the lessons that have been learned).

Although the research on crisis management is gaining popularity, it is, however, limited to traditional organizations ( Valackiene, 2011 ) by particularly focusing on exogenous phenomena, such as antecedents, management and consequences of crisis ( Simard and Laberge, 2018 ; Wang and Pitsis, 2020 ) while ignoring PBOs. The need for crisis management in PBOs is more substantial than in traditional organizations, and PBOs are an especially interesting context for crises given that most of their undertakings are unique and difficult to plan in advance ( Loosemore, 2000 ; Geraldi et al. , 2010 ). PBOs are different from conventional organizations since they are temporarily formed to perform unique and complex tasks ( Sydow et al. , 2004 ; Turner, 2006 ). According to Lundin and Söderholm (1995) , there are four attributes that make temporary organizations different from permanent ones: (1) time (temporary organizations have a built-in time dimension that contains the starting and ending time periods); (2) task (the reason for establishing of the temporary organization; the task is unique and complex, so the task seems to be more relevant to project team despite being members of permanent organizations); (3) team (temporary organizations rely on teams in which interdependent sets of people work together, and these teams are groups of individual, not organizational entities); and (4) transition (temporary organizations consider transition something important and useful, e.g. to overcome inertia, which is inherent in most of the permanent organizations). Permanent organizations have more naturally defined goals (rather than tasks), survival (rather than time), a working organization (rather than teams) and production processes, and continual development (rather than transition) ( Lundin and Söderholm, 1995 ). PBOs are temporary organizations and coexist with permanent organizations ( Kutsch and Hall, 2005 ).

Several studies have highlighted the dire need to investigate crisis management in the context of PBOs ( Pourbabaei et al. , 2015 ; Simard and Laberge, 2018 ), but the field of crisis management is very vast and still in its infancy because there is not a standardized process for crisis management ( Shrivastava, 1994 ; Hussain, 2019 ). Moreover, PBOs are different from permanent organizations. So far, little is known about crisis management in PBOs. It is necessary to develop a core framework which directs the crisis management process in PBOs. As a result, there is a need to further study crisis management in the context of PBOs. Keeping in view the scarcity of research, this conceptual study bridges the aforementioned gaps by developing a comprehensive model of the crisis management process and propositions for PBOs, which will advance the knowledge of crisis management in the project management field. In doing so we make several contributions. First, we clarify the process of crisis management for PBOs. Despite an increase in scholarly attention (e.g. Pearson and Clair, 1998 ; Ponis and Koronis, 2012 ), there is not generally accepted theoretical or conceptual delineation of crisis management for PBOs. We felt our contribution could be the development of a framework that could help researchers and practitioners in different fields to reflect on their research and to provide guidance from the developed crisis management model. Second, scholars and practitioners have a clear understanding of the factors that contribute to crisis management for PBOs, this will enhance their understanding of crisis and prepare them for crisis management. Third, we explore processes such as sense-making and decision-making, response and learning through which crisis is managed. Finally, we extend dynamic capability theory, in which we considered crisis management as a capability to perform a task. The organization uses its crisis management capabilities to identify crises and to minimize their impact on performance as well as learn from the outcome, i.e. the success or failure of the crisis management process which will refine and enhance further the crisis management process.

Literature review

PBOs have received increasing attention as an emerging organizational form ( Hobday, 2000 ). PBOs first became famous in the late 1990s. PBOs are found in a wide range of industries ( Thiry and Deguire, 2007 ). These include consulting and professional services (e.g. accounting, advertising, architectural design, law, management consulting and public relations), cultural industries (e.g. fashion, theatre, film-making, video games, advertisement and publishing), high technology (e.g. software, computer hardware, multimedia, aerospace, ICT and IT) and complex products and systems (e.g. construction, shipbuilding, transportation, telecommunications, oil and gas, defense, infrastructure, pharmaceutical, biotech, semi-conductors, automotive and electric equipment) ( Midler, 1995 ; Hobday, 2000 ; Berggren et al. , 2001 ; Ebers and Powell, 2007 ). Organizations that work predominantly or entirely performed in projects are commonly referred to as PBOs ( DeFillipi and Arthur, 1998 ).

A project is “a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product or service” ( PMI, 2004 , p. 4). A comprehensive definition of the project is a temporary organization in which human, material and financial resources are organized in a novel way to undertake a unique and transient endeavor to achieve an objective conforming to specific requirements (have defined start and end dates and funding limits), managing the inherent uncertainty and need for integration in order to deliver beneficial objectives of change ( Toor and Ogunlana, 2010 ; Yang et al. , 2011 ). Generally, projects as temporary systems refer to groups comprising a mix of different specialist competences, which have to achieve a certain goal or carry out a specific task within limits set as to costs and time ( Sydow et al. , 2004 ).

There are several definitions of crisis, but we choose the most widely cited and well-recognized definition, proposed by Pearson and Clair, which is also cited by other contemporary researchers (such as Wilding and Paraskevas, 2006 ; Oh et al. , 2013 ; Iftikhar and Müller, 2019 ). Pearson and Clair view crisis as “a low-probability, high impact event that threatens the viability of the organization [in our case, it is a project-based organization] and is characterized by ambiguity of cause, effect, and means of resolution, as well as by a belief that decisions must be made swiftly” (1998, p. 60). The most recent study ( Williams et al. , 2017) defines a crisis as a low-probability, unanticipated, high-impact event that, which is aligned with Pearson and Clair's perspective of crisis.

The definition highlights crisis as (1) a major, unpredictable event that is likely to interfere with normal business operations and has the potential to threaten survival, (2) a rare event which includes an element of surprise and (3) being characterized by time pressures, requiring a quick decision and response to minimize its impact ( Bonn and Rundle-Thiele, 2007 ; Yang et al. , 2022 ). Examining the above definition, there are a few characteristics. First, a crisis is an unplanned event that has the potential of dismantling the internal and external structure of an organization. A crisis may affect not only the employees and other members internal to the organization but also key stakeholders external to the organization. Second, a crisis may occur in any organization (small, medium or large and national or international) and in any industry ( Coleman, 2004 ; Keeffe and Darling, 2008 ). Finally, a crisis may affect the legitimacy of an organization ( Ray, 1999 ).

Several studies have found that crises may have positive as well as negative consequences ( Darling, 1994 ; Veil, 2011 ). In that respect, crises can present critical challenges to organizations, both externally and internally, and there is no guarantee that high-performing organizations will continue to perform well in times of crisis ( Lin et al. , 2006 ; Hällgren and Wilson, 2008 ). According to Wang and Pitsis (2020) , crisis is an unexpected event that threatens the security of PBOs, which makes it an especially interesting context of crises as the PBOs undertakings are unique and difficult to plan in advance ( Loosemore, 2000 ; Geraldi et al. , 2010 ). At the same time, prior research indicates that crisis management is crucial to the operations of any PBO, and that these organizations must develop capabilities to maintain a steady state of operations as well as the ability to respond to crises ( Söderlund and Tell, 2009 ). Effective crisis management requires knowing the particular nature of each crisis and what caused it, how to make prompt decisions and respond to it ( Najafbagy, 2011 ). However, different researchers have come up with different strategies to minimize the negative consequences of the crisis. For instance, Alkharabsheh et al. (2014) suggest the development of an “early warning system” that can help project managers in surviving a crisis with minimal loss. Patil et al. (2016) emphasized on transparent communication and reporting during a crisis and recommended team members to develop and strictly follow rules for minimizing the crisis.

Despite, the abundance of crisis management strategies, there is limited literature available on the crisis management framework. The existing studies on crisis management have devised strategies which can only be implemented to megaprojects ( Wang and Pitsis, 2020 ; Iftikhar et al. , 2021 ; Wang, 2022 ) and specific industries, such as housing projects ( Patil et al. , 2016 ), infrastructure project ( Van Os et al. , 2015 ) and software projects ( Sangaiah et al. , 2018 ). Moreover, contemporary research gives importance to crisis, but we find that the integrated crisis management process model is not developed for PBOs which can provide guidance to PBOs in crisis situations. There is a need to develop an integrated framework for crisis management that can be applied to project-based settings ( Bundy et al. , 2017 ; Williams et al. , 2017 ). Keeping in view these important research gaps, the current study aims to develop a comprehensive conceptual crisis management framework that can be used by PBOs to manage the crisis.

Dynamic capability theory

This paper considers the theoretical lens of dynamic capability theory. Dynamic capabilities theory examines how organizations integrate, build and reconfigure their internal and external organization-specific competencies into new competencies that match their turbulent environment, which enables organizations to effectively respond to changes in dynamic environments ( Teece et al. , 1997 ). Davies et al. (2016) study that to achieve organizational dynamic capabilities, flexibility and adaptability are required to handle crises. According to Killen and Hunt (2010) , dynamic capability consists of people, structures and processes that are continually monitored and adjusted to meet the changing requirements of the dynamic environment. Although, studies on crisis management have recently adopted insights from dynamic capability theory ( Mayr et al. , 2022 ; Sahebalzamani et al. , 2023 ); however, research on crisis management in PBO's under the lens of dynamic capability theory is still lacking. Since PBO's are different from traditional organizations, the nature of the crisis, its sources and solutions may also vary for PBOs. Relying on dynamic capability theory, this study aims to explore the crisis management process for PBO's. The PBO uses its crisis management capabilities to identify crisis and minimize their impact on performance ( Helfat et al. , 2007 ). In the suggested crisis management process model, we considered crisis as a turbulent environment containing external and internal crises and PBOs integrate, build and reconfigure their sense-making, decision-making, response and learning competencies, particularly for crisis management.

A systematic literature review synthesizes the existing body of knowledge and creates new knowledge ( Tranfield et al. , 2003 ). We implement a systematic literature review in three steps, as illustrated in Figure 1 .

The first step includes searching for articles using electronic databases (EBSCO Business Source Complete, Google Scholar and ISI Web of Science). The search rule employed in the title/abstract/keyword (T/A/K) field of the selected databases was (“crisis, “crisis management,” “project,” and “project-based organizations”) and (“sense-making”, “information gathering”, “crisis interpretation”, “decision-making”, “response” and “learning”). We also deployed a snowball approach by tracing the references in the articles found to incorporate the most imperative research work. This revealed 365 articles, all published between 1963 and 2022. Manual screening of each article's publication source and abstract was then conducted according to the following predefined inclusion criteria: articles must be (1) written in English; (2) published in peer-reviewed journals, books or book chapters and conference papers; and (3) published in high-ranking journals. Book reviews and editorials were eliminated, and only peer-reviewed papers were considered in this research. This led to the inclusion of articles published in journals such as the Academy of Management Journal ( AMJ ), Academy of Management Executive (AME), Academy of Management Review ( AMR ), Administrative Science Quarterly ( ASQ ), Journal of Management Studies ( JMS ), Management Learning (ML), Organization Science ( OS ), Business Ethics Quarterly , the International Journal of Project Management (IJPM), Project Management Journal (PMJ) , International Journal of Managing Projects in Business and Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. To these, we added two of the leading practitioner-oriented journals, namely, the California Management Review ( CMR ) and Harvard Business Review ( HBR ).

The literature was selected for review based on its relevance to the topic under study. So far that reason in the next step, we excluded irrelevant papers by reading their titles, abstracts and keywords. The abstract was read if the title did not explicitly exclude the relevancy of the article. However, the abstract did not always provide enough information to decide whether the article included relevant information or not. In that case, the first author decides whether an article was useful by going through the introduction section. To avoid unnecessarily excluding other relevant studies published in lower ranking journals, the abstract was reviewed, and if it met the required standards, these articles were also considered for review. This stage yielded a total of 171 publications. We incorporated both empirical (qualitative and quantitative), conceptual and theoretical studies in the review. Moreover, the literature review also includes textbooks/reports relevant to our study.

The next step is to analyze those publications, the technique of content analysis is employed to “classify large amounts of text into an efficient number of categories that represent similar meanings” ( Hsieh and Shannon, 2005 , p. 1278). This content analysis comprises two parts: descriptive and thematic. The descriptive analysis was achieved by providing a description of the studies gathered in the data extraction form. The thematic analysis was done by analyzing the studies and defining the different themes presented in each study. As discussed by Tranfield et al. (2003) , it is essential to connect themes across the diverse core contributions and highlight any connections. The process creates an overview of the main findings and generates a solid basis to identify research gaps ( Tranfield et al. , 2003 ). The following sections detail and analyze each of the identified themes.

Findings: conceptual framework: crisis management process model – a multidimensional perspective

In Figure 2 , we provide a comprehensive model of the crisis management process for PBOs. We begin our presentation of the model by discussing the importance of sense-making, followed by decision-making, response, outcome and learning. Sense-making is about developing an understanding of crisis ( Weick et al. , 2005 ). This is considered the first step in our model as once a crisis strike, it is of utmost important to understand the crisis. Once an understanding of crisis is developed through sense-making, the next crucial step is to make decisions. A crisis needs rapid and right decision-making in order to minimize its impact as described by Pearson and Clair (1998) . Decision-making is a process of selecting the best option ( Anderson, 1983 ). The next step is to apply the decision by taking appropriate actions. According to Brunsson (1982) , actions are supposed to be initiated by rational decision procedures. The response is actually an implementation of the best option derived from decision-making process. It leads to outcome which could be success and failure ( Bundy and Pfarrer, 2015 ). The outcome which could be either success or failure, leads to organizational learning ( Haunschild and Sullivan, 2002 ; Baum and Dahlin, 2007 ).

Prior studies have considered how sense-making unfolds in a crisis in a wide range of contexts, including the Bhopal accident ( Weick, 2010 ), the Mann Gulch fire ( Weick, 1993 ), etc., which are illustrations of life-threatening events ( Iftikhar et al. , 2021 ). It does not take fire or a life-threatening event to precipitate a crisis, but it also includes normal accidents ( Kornberger et al ., 2019 ), which is the focus of this study. Much of the work examines sense-making in a single high-reliability organization (such as firefighting and aircraft carrier flight decks) ( Maitlis, 2005 ; Rudolph et al. , 2009 ; Clark and Geppert, 2011 ; Cornelissen, 2012 ; Monin et al. , 2013 ). In addition, prior research considered decisions as a result of a sense-making process ( Weick, 1995 ; Musca et al. , 2014 ). Decision-making is integral to the management of projects ( Stingl and Geraldi, 2017 ) and at time of crisis, it is extremely important.

We explored the role of response for crises; a response is an action which could alter the environment under consideration ( Porac et al. , 1989 ). The literature talks about proactive and reactive responses to abrupt events ( Barber and Warn, 2005 ). In addition, following the response, the outcome is either success or failure. There is a learning process whereby an organization acquires new information ( Miner and Robinson, 1994 ), and this helps to improve its prospects in environments ( Cyert and March, 1963 ; Sommer et al. , 2016 ).

The term “sense-making” is introduced by Karl Weick and simply means “the making of sense.” It refers to how we structure the unknown to be able to act in it ( Weick, 1995 , p. 4). Sense-making is the process through which people work to understand issues or events that are novel, ambiguous, confusing or in some other way violate expectations. Sense-making is triggered by cues such as issues, events or situations, for which the meaning is ambiguous and the outcome is uncertain ( Meyer, 1982 ), and where events, issues and actions are somehow surprising and confusing ( Weick, 1993 , 1995 ; Maitlis, 2005 ). According to Cornelissen (2012 , p. 118), “Sense-making refers to processes of meaning construction whereby people interpret events and issues within and outside of their organizations that are somehow surprising, complex, or confusing to them”.

Sense-making involves a few steps. The foremost step is sensing the problem. A problem is perceived when a discrepancy or gap occurs between the existing state (perceived reality, initial state) and the desired state (goal, standard of how things should be in the terminal state). Sensing a discrepancy between the existing and desired state is the first step in the process. When a situation feels “different,” it is experienced as a situation of discrepancy ( Orlikowski and Gash, 1994 ), breakdown ( Patriotta, 2003 ), surprise ( Louis, 1980 ), disconfirmation ( Weick and Sutcliffe, 2001 ), opportunity ( Dutton, 1993 ) or interruption ( Mandler, 1984 ). There are three main “sense-making moves” or key processes: scanning/information seeking, interpreting/creating interpretations and responding/taking action. These are all important aspects of the more general notion of sense-making ( Daft and Weick, 1984 ; Milliken, 1990 ; Gioia and Chittipeddi, 1991 ; Weber and Glynn, 2006 ; Rudolph et al. , 2009 ). According to Weick et al. (2005) , sense-making is about how something comes to be an event for organizational members. Second, sense-making is about the question: What does an event mean? In the context of everyday life, when people confront something unintelligible and ask, “What's the story here?” they then ask, “Now what should I do?” ( Weick et al. , 2005 ). We believe that information seeking, and the interpretation of the situation are the two pillars of the sense-making process; however, response is a separate dimension.

Information gathering

Dealing with uncertainty requires information from the environment ( Braybrooke, 1964 ). Information gathering is defined as the process of monitoring the environment and providing environmental data to managers ( Daft and Weick, 1984 ). Information can come from external or internal, and personal or impersonal sources ( Aguilar, 1967 ; Keegan, 1974 ). In external sources, managers have direct contact with information outside the organization and search the external environment to identify important events or issues ( Daft and Weick, 1984 ; Milliken, 1990 ). Internal sources pertain to information collected and provided to managers by other people in the organization through internal channels). Personal sources involve direct contact with other individuals, whereas impersonal sources are written documents such as newspapers and magazines or reports from the organization's information system ( Daft and Weick, 1984 ). As per Iftikhar et al . (2022a) , these information-gathering sources are equally relevant for PBOs. On the one hand, hazardous and rapidly unfolding situations are difficult to comprehend, so people want to gather more information to determine the most appropriate action. On the other hand, the demands of the situation often require them to take action with incomplete information, since in a crisis, there is pressure (and sometimes immense pressure) to make sense of the world quickly ( Maitlis, 2005 ) and the pressure built-ups in the temporary setting of PBOs. According to Ajmal et al. (2010) , PBOs suffer adversely when they do not have proper information systems in place, affecting their knowledge management activities.

Of course, all of the information received is not necessarily relevant. Accessing the right information at the right time can also be problematic. One of the problems with information gathering is information overload. Information overload means having more information than one can acquire, process, store or retrieve ( Brennan, 2011 ). In their comprehensive review of the literature on information overload, Eppler and Mengis (2004 , p. 326) offered the following description: “Information overload occurs when the supply exceeds the capacity, and a diminished decision quality are the result.” Overload often leads to stress, inefficiency and mistakes that can result in poor decisions, bad analysis and/or miscommunication ( Eppler and Mengis, 2004 ). Therefore, we need quality information, which means the right information at the right time in the right amount.

Rich information gathering (internal and external) will positively impact the accuracy of PBOs' decision-making.

Rich information gathering (internal and external) will negatively impact the timeliness of PBOs' decision-making.

Decision quality depends upon three factors: (a) the quality of information inputs into the decision process (it depends on the ability of the system to effectively absorb information flows, thus preventing overloads and reducing noise in communication channels. Noise depends upon the distance between units in the organization); (b) the fidelity of objective articulation and tradeoff evaluation (input: cognitive abilities and group think; output: quality decisions); and (c) the cognitive abilities of the decision group (the abilities of the decision unit to interpret information, generate options creatively, calculate and make choices between alternative courses of action) ( Smart and Vertinsky, 1977 ).

Crisis interpretation

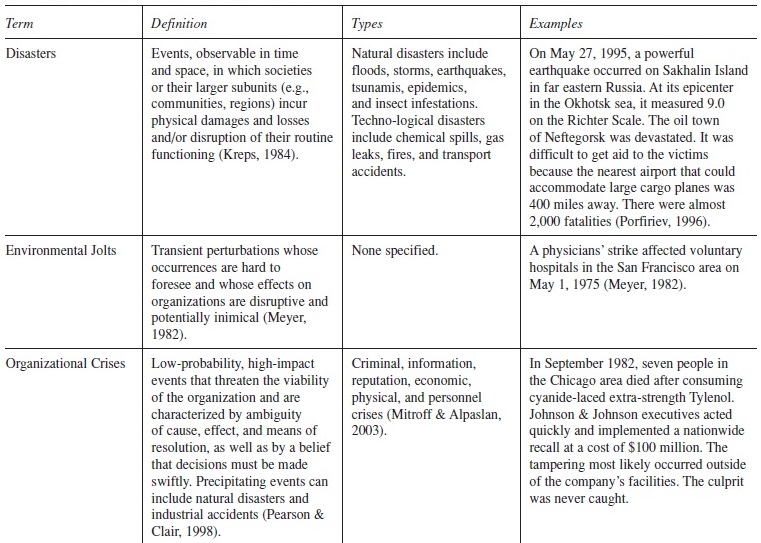

Interpretation is the process of translating events and developing shared understanding, but it occurs before action ( Daft and Weick, 1984 ). We consider crisis as “a low-probability, high impact event” ( Pearson and Clair, 1998 , p. 60). Crisis interpretation defines where the crisis lies and what the sources and characteristics of the crisis are, meaning whether the crisis lies internally or externally, the reason for the crisis and whether the crisis is technical, economic or social in nature ( Iftikhar et al. , 2022a ). In this paper, we draw on the classic work of Mitroff et al. (1987 , 1988) and Shrivastava and Mitroff (1987) to develop a typology, where crises are categorized into four types relying on a framework consisting of two dimensions. First, the internal-external dimension determines the source of factors that result in a crisis, which can be the failure of an internal organization system or a failure in the organization's external environment. Second, the technical-social dimension involves the characteristics of factors that cause a crisis; these include technical and/or economic failures or issues associated with human, organizational or social concerns. Following Mitroff et al. 's (1987) and Shrivastava and Mitroff's (1987) typologies of crises, we derived Table 1 .

Cell 1 represents failures in internal social processes and systems. These crises are most often caused by operator or managerial errors, intentional harm by saboteurs, faulty control systems, unhealthy working conditions or the failure of decision-making systems. The miscommunication of vital safety information, unsafe decisions or deliberate harm may result from these failures ( Shrivastava and Mitroff, 1987 ). In 1986, the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded 74 s after takeoff, killing all six crew members and one civilian passenger. This tragedy was a crisis for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). The explosion was caused by the failure of the solid rocket booster that powered the shuttle. The launch took place at an extremely low air temperature, which caused the seals of the booster to lose their elasticity and malfunction. The problem was in the design of booster seals ( Shrivastava et al. , 1988 ; Vaughan, 1996 ).

Cell 2 represents technical and economic failures in internal organizational systems. These are caused by failures in the core technology of firms. Crises in this cell are triggered by major industrial accidents, such as Bhopal, Three Mile Island or Chernobyl. Defects in plant equipment, design or supplies are the primary cause of these crises. For example, a reactor meltdown at a nuclear power plant in Chernobyl caused the deaths of about 30 people. Hundreds of thousands of those living in the vicinity of the plant were severely irradiated ( Shrivastava and Mitroff, 1987 ; Liberatore, 2013 ).

Cell 3 represents failures in the social environment of corporations. These crises occur when agents or institutions in the social environment react adversely to the corporation. Incidents of sabotage, terrorism or off-site product tampering or misuse are examples of such failures ( Shrivastava and Mitroff, 1987 ). For example, in 1982, dozens of Tylenol capsules were found to be contaminated with cyanide. Eight people who ingested these capsules died immediately. This created a nationwide public health scandal and a crisis for Johnson & Johnson, who had manufactured the capsules. The full cost of withdrawing products from shelves and switching from the production of capsules to other forms of medication exceeded $500 million ( Shrivastava and Mitroff, 1987 ; Mitroff et al. , 1988 ; Olaniran et al. , 2012 ).

Cell 4 displays crises primarily related to technological and economic failures in the firm's environment, which cause crises within the organization. Examples might include hostile takeover attempts prompted by the restructuring of industries, drastic currency rate changes and other macroeconomic occurrences or attacks by corporate raiders. In 1985, for instance, cheese contaminated with poisonous bacteria was sold in California, which killed 84 people, creating a major public health crisis that affected the entire state. The victims' relatives sued the manufacturer for billions of dollars, forcing it into a hostile takeover ( Shrivastava and Mitroff, 1987 ).

Crises are characterized by low probability/high consequence events that threaten the most fundamental goals of an organization. Because of their low probability, these events defy interpretations and impose severe demands on sense-making. It is crucial to give meaning to crises in order to make appropriate decisions. According to studies done on the causes of real-life crises that took place in PBOs such as defense and healthcare; in formal, the majority of the crises took place due to the misinterpretation of the whole situation ( Fisher et al. , 2003 ); in the latter, a misinterpretation of information led to the death of a patient ( Albrecht et al. , 2004 ). Both these studies highlight the serious consequences of poor interpretations of crises. A crisis is an unknown situation that brings with it a lot of questions with no obvious answers, thus, creating the challenge of interpreting the situation properly ( Williams et al. , 2017 ). Those organizations which fail to interpret crises end up facing serious losses ( Li et al. , 2018 ). People who fail to interpret a crisis efficiently and effectively end up indulging in irrational decision-making ( Leung and Law, 2016 ). Decision-making is shaped by the quality of information sharing and information processing during and after a crisis ( Uitdewilligen and Waller, 2018 ).

Crisis interpretation is likely to lead to accurate and timely PBOs' decision-making.

During a crisis, decision-making is critical to make accurate and timely decisions ( Loosemore, 1998 ). The consequences of a crisis are high, as it is a low-probability, high-severity event; however, its impact can be reduced by rapid and accurate decision-making ( Mallak and Kurstedt, 1997 ; Kahn et al. , 2013 ). Good decisions must be made quickly, despite the uncertainty, time pressure and high stakes associated with a crisis ( Pearson and Clair, 1998 ). As Sawle (1991) said of the importance of decisions in a crisis, “the worst decision is no decision, and the second worst decision is a late one”. It is critical to integrate crises in decision-making process. The objective is to make the right decisions and execute them effectively. Decision-making is complex and at times of crisis, it is more complicated ( Wilson, 2013 ), as a crisis is an unexpected, unusual and abnormal event ( Lacombe, 2002 ). The core elements that define a crisis – ambiguity, urgency and high stakes – are also severe constraints on the ability of individuals to make decisions effectively ( Pearson and Clair, 1998 ).

Decision-making in crises is characterized by a high level of uncertainty, urgency to act, a narrowing of options and high-stakes implications for organizational survival. At the time of crisis, the challenge for any organization is to make decisions quickly and accurately ( Bonn and Rundle-Thiele, 2007 ) as individuals make decisions based on their perceptions ( Wang and Pitsis, 2020 ). In a crisis, one must secure a high-quality decision-making process. A decision process consists of the articulation of objectives, the generation of alternate courses of action, an appraisal of their feasibility, an evaluation of the consequences of the given alternatives, and a choice of the alternative which contributes most to the attainment of organizational objectives ( Smart and Vertinsky, 1977 ). In conventional terms, the task of making a decision can be decomposed into five subtasks: (1) identifying the relevant goals; (2) searching for alternative courses of action; (3) predicting the consequences of following each alternative; (4) evaluating each alternative in terms of its consequences for goal achievement; and (5) selecting the best alternative for achieving the goal ( Anderson, 1983 ).

Timely and accurate PBOs' decisions will lead to an appropriate crisis response.

Response is a capacity where people feel they can do something about the crisis ( Weick, 1988 ). Organizations increasingly face crises, yet little is known about how they develop their responses to unexpected events that enable their work to continue. According to Wang and Pitsis (2020) , the agreement of key stakeholders on response strategies is critical to resolving a crisis. One of the characteristics of a crisis is that it contains an element of surprise. A surprise is a break in expectations that arises from situations that are not anticipated or do not proceed as planned ( Cunha et al. , 2006 ) and encompasses any element within an organization that is unexpected and draws attention away from the standard progression of the work. Crises can occur in various ways. They can be generated by events and by processes. It is impossible for people to know in advance the form a crisis will take, what its source will be or which members it might involve.

Crises are turning points in organizations. The crisis situation will determine the appropriate action. People often do not know what the “appropriate action” is until they take some action and see what happens. Thus, actions determine the situation. Once a person becomes committed to an action, he/she then builds an explanation that justifies that action ( Weick, 1988 ). There are two ways to respond to the crisis, namely, firefighting and fire lighting. Fire fighter style is reactive behavior, where the focus is on tackling immediate problems. Fire lighter style is proactive behavior, able to explain the big picture, anticipate events and even prevent problems ( Barber and Warn, 2005 ). It is almost impossible for people to know in advance the form a crisis might take, what its source will be or which stakeholders it might involve. Since a crisis is a low probability and high-impact event, it is not possible to plan contingencies for it, hence only a reactive response can be taken.

A reactive response will lead either to success or failure outcomes for PBOs and for their projects.

It is important to determine the appropriate action. It is our contention that actions play a central role in the genesis of crises and therefore need to be understood if we are to manage crises ( Weick, 1988 ).

Outcomes (success/failure)

According to Pearson and Clair (1998) , any crisis process results in relative degrees of success and failure. The novelty, magnitude and frequency of decisions, actions and interactions demanded by a crisis suggest that no organization will respond in a manner that is completely effective or completely ineffective. Much of the literature treats organizational consequences in the event of a crisis as though alternative outcomes were dichotomous: the organization either failed ( Turner, 1976 ; Vaughan, 1990 ; Weick, 1993 ) or succeeded (e.g. Roberts, 1989 ) in managing any particular crisis incident. Pearson and Clair (1998) proposed that “an organizational crisis will lead to both success and failure outcomes for the organization and its stakeholders” (1998, p. 68). However, it is not the crisis itself but its management which will lead to success or failure as an outcome for the organization. If a crisis is efficiently managed it will lead to success; in contrast, if the crisis is poorly managed, it will lead to failure. Researchers of organizational crises have examined a variety of factors that contribute to crisis management successes and failures. However, we suggest a subprocess for the crisis management process.

Crisis management outcomes (success/ failure) will lead to PBOs' learning.

Organizational learning is not simply the sum of individual learning ( Hedberg, 1981 ); rather, it is the process whereby knowledge is created, distributed across the organization, communicated among organization members and integrated into the strategy and management of the organization ( Duncan and Weiss, 1978 ). Organizational learning occurs when an organization institutionalizes new routines or acquires new information ( Miner and Robinson, 1994 ). Organizational learning helps organizations to enhance their practices and to improve their prospects in dynamic and competitive environments ( Cyert and March, 1963 ; Argote, 2011 ).

Learning can occur at several different levels (such as at the individual, project, firm or industry levels) and often as an unintended by-product of the project activity ( DeFillipi and Arthur, 2002 ). Project-based learning practices are a subset of organizational learning practices ( Keegan and Turner, 2001 ). Learning in PBOs most commonly refers to the process of making newly created project-level learning available to the organization as a whole by sharing, transferring, retaining and using it ( DeFillipi and Arthur, 1998 ; Prencipe and Tell, 2001 ; Scarbrough et al. , 2004 ; Argote and Ophir, 2005 ). However, previous research has emphasized the difficulties that organizations face when they attempt to capture the learning gained through projects and transfer it to their wider organizations (e.g. Middleton, 1967 ; Keegan and Turner, 2001 ). There is a risk that the experience gained is lost when the project finishes, the team dissolves and its members move on to other projects or are reabsorbed into the organization. Unless lessons learned are communicated, and experience gained on one project is transmitted to subsequent projects, there is also a risk that the same mistakes are repeated ( Middleton, 1967 ; Iftikhar and Wiewiora, 2022 ). “Lessons learned” is a popular term; however, it is often only lip service paid to the idea of learning from experience ( Smith and Elliot, 2007 ). As Williams et al. (2012) have stated, there are many lessons identified, but not very many learned.

To date, the study of crisis management has focused on crisis causality, prevention, response and turnaround, with limited consideration given to organizational learning from crisis ( Elliott and Smith, 2006 ). Organizations tend to engage in major changes mainly after they have been confronted with crises ( Miller and Friesen, 1984 ; Tushman and Anderson, 1986 ). Learning from crises involves understanding the causes of the crises, as well as identifying ways of preventing similar rare events from recurring and understanding what took place in the right or wrong direction ( Rerup, 2009 ; Locatelli and Mancini, 2010 ). Learning must focus on the ability to create resilience to cope with unforeseen high-impact events. It only becomes meaningful when lessons are put into practice; they have to be translated and used to make sense of new situations and enacted in order to manage an unfolding scenario ( Elliott and Macpherson, 2010 ). Project members can learn from their own crisis management experiences as well as others involved in the process. Moreover, learning from crises can improve future projects and future stages of current projects ( Iftikhar et al. , 2022b ).

Learning from crisis management outcomes (success/ failure) alleviate PBOs and their projects.

Despite an increase in the frequency of crises, the research on crisis management, particularly in the context of PBOs, is still in its initial stages. More specifically, there is a lack of a comprehensive crisis management model that can be applied to PBOs. Keeping in view this research gap, the current study presented a crisis management framework with special attention to PBOs. The novel insights this study has brought by proposing a crisis management framework which identified the importance and association of sense-making, timely decision-making and quick responses to crises and interplay among each other for the effectiveness of crisis management.

Theoretical implications

The current study adds to the literature on crisis management, particularly in the context of PBOs. This study has conceptualized a framework for crisis management, which consists of all those important factors that are underexplored. This study advances research on crisis management by proposing a comprehensive model for crisis management. The paper considers the theoretical lens of dynamic capability theory. The dynamic capability theory focuses on the processes used in organizations to integrate, build and reconfigure their internal and external resources and competencies to compete in dynamic environments ( Teece et al. , 1997 ; Killen and Hunt, 2010 ). An organization has dynamic capabilities when it can integrate, build and reconfigure its internal and external organization-specific capabilities in response to its changing environment. In our study, we considered sense-making, decision-making, response and learning as PBOs capabilities for handling changing environment of crisis. This study validates the dynamic capability theory in the context of crisis management and PBOs.

Practical implications

This study helps scholars and practitioners to develop a clear understanding of the factors that contribute to crisis management for PBOs. For academics, this contributes to a better understanding of the crisis and its management, which allows for more precise and focused investigations in the future. The results of the study not only add value to the scarce literature on crisis management in PBOs but also offer valuable insights to project managers who can take help from this study. Practitioners such as senior management, project managers and project team members benefit from being in a position to better describe the status of their organization or project and to identify actions appropriate for their particular situation. This includes taking managerial actions to make sense, decisions and responses for intra-organizational projects to manage the crisis. Practitioners' crisis awareness is an invisible force behind the crisis management process that affects their subsequent actions to handle the crisis. Another takeaway from this study is the revelation that crises, despite all their negativity, promote learning in organizations, improving the crisis management process in the future. The conceptual framework proposed in the study acts as a guideline for all those project managers who are either currently facing a crisis or are expected to come across a crisis. The steps proposed in the framework must be used by the project managers as standard operating procedures to minimize the financial and non-financial impact of the crisis. The project managers should be trained to enhance their sense-making and decision-making skills. They should also be taught about the importance of taking a reactive response. Another important insight from this study is the identification of crisis triggers. The project managers should keep an eye on all the factors that can trigger a crisis, so they have the necessary information during a crisis. This study also highlights the importance of learning in crisis. Managers should be bound to submit a report in which they should list down all the lessons they learned from the crisis. They should also be asked to share their opinion regarding the most suitable course of action in a similar situation. This report should be shared with all the employees and made accessible so that managers can take help from it if they face any similar situation in the future.

Limitations and future research

The first limitation of this study is that it is a conceptual study, presenting the crisis management process model and propositions. Although this model allows the identification of crisis and crisis management relationship with sense-making, decision-making, response and learning. This model will improve the field of crisis management. However, it is important to understand whether it works as we suggested, as it has not been tested empirically. Future researchers might test the model by studying it empirically. Another limitation of this study is that it has only highlighted the role of crisis triggers. Future studies might also discuss different factors that might trigger a crisis.

Moreover, this study has not mentioned the decision-making styles needed for crisis management. Future studies may also shed light on the most suitable decision-making style during a crisis. The current study has developed a standardized model that can be applied to PBOs in different industries, which strengthens the study due to generalizability. However, a more customized crisis management model which is specific to a particular industry might prove to be useful as the nature of crisis varies from one industry to the other. Future researchers might propose crisis management models that can be applied to a particular industry.

Stepwise approach for systematic literature review

Crisis management process model for project-based organizations

Different typology of crisis

Source(s): Created by Iftikhar (2023)

Aguilar , F. ( 1967 ), Scanning the Business Environment , Macmillan , New York .

Ajmal , M. , Helo , P. and Kekäle , T. ( 2010 ), “ Critical factors for knowledge management in project business ”, Journal of Knowledge Management , Vol. 14 No. 1 , pp. 156 - 168 .

Albrecht , B. , Bender , B. , Katz , R. , Pirani , J.A. and Salaway , G. ( 2004 ), “ Information technology alignment in higher education ”, available at: https://library.educause.edu/resources/2004/6/information-technology-alignment-in-higher-education ( accessed 7 October 2020 ).

Alkharabsheh , A. , Ahmad , Z.A. and Kharabsheh , A. ( 2014 ), “ Characteristics of crisis and decision making styles: the mediating role of leadership styles ”, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences , Vol. 129 , pp. 282 - 288 .

Almeida , M.V. and Soares , A.L. ( 2014 ), “ Knowledge sharing in project-based organizations: overcoming the informational limbo ”, International Journal of Information Management , Vol. 34 No. 6 , pp. 770 - 779 .

Alonso-Almeida , M.D.M. , Bremser , K. and Llach , J. ( 2015 ), “ Proactive and reactive strategies deployed by restaurants in times of crisis: effects on capabilities, organization and competitive advantage ”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management , Vol. 27 No. 7 , pp. 1641 - 1661 .

Anderson , P.A. ( 1983 ), “ Decision making by objection and the Cuban missile crisis ”, Administrative Science Quarterly , Vol. 28 No. 2 , pp. 201 - 222 .

Argote , L. ( 2011 ), “ Organizational learning research: past, present, and future ”, Management Learning , Vol. 42 No. 4 , pp. 439 - 446 .

Argote , L. and Ophir , R. ( 2005 ), “ Intraorganizational learning ”, in Baum , J.A.C. (Ed.), The Blackwell Companion to Organizations , Blackwell , Oxford , pp. 181 - 207 .

Barber , E. and Warn , J. ( 2005 ), “ Leadership in project management: from firefighter to firelighter ”, Management Decision , Vol. 43 Nos 7/8 , pp. 1032 - 1039 .

Baum , J.A.C. and Dahlin , K.B. ( 2007 ), “ Aspiration performance and railroads' patterns of learning from train wrecks and crashes ”, Organization Science , Vol. 18 No. 3 , pp. 368 - 385 .

Bechky , B.A. and Okhuysen , G.A. ( 2011 ), “ Expecting the unexpected? How swat officers and film crew handle surprises ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 54 No. 2 , pp. 239 - 261 .

Berggren , C. , Söderlund , J. and Anderson , C. ( 2001 ), “ Clients, contractors, and consultants: the consequences of organizational fragmentation in contemporary project environments ”, Project Management Journal , Vol. 32 No. 3 , pp. 39 - 48 .

Bertels , S. , Cody , M. and Pek , S. ( 2014 ), “ A responsive approach to organizational misconduct: rehabilitation, reintegration, and the reduction of reoffense ”, Business Ethics Quarterly , Vol. 24 No. 3 , pp. 343 - 370 .

Bonn , I. and Rundle-Thiele , S. ( 2007 ), “ Do or die – strategic decision-making following a shock event ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 28 No. 2 , pp. 615 - 620 .

Braybrooke , D. ( 1964 ), “ The mystery of executive success re-examined ”, Administrative Science Quarterly , Vol. 8 No. 4 , pp. 533 - 560 .

Brennan , L.L. ( 2011 ), “ The scientific management of information overload ”, Journal of Business and Management , Vol. 17 No. 1 , pp. 121 - 134 .

Brown , J.A. , Buchholtz , A.K. and Dunn , P. ( 2016 ), “ Moral salience and the role of goodwill in firm-stakeholder trust repair ”, Business Ethics Quarterly , Vol. 26 No. 2 , pp. 181 - 199 .

Brunsson , N. ( 1982 ), “ The irrationality of action and action rationality: decisions, ideologies and organizational actions ”, Journal of Management Studies , Vol. 19 No. 1 , pp. 29 - 44 .

Bundy , J. and Pfarrer , M.D. ( 2015 ), “ A burden of responsibility: the role of social approval at the onset of a crisis ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 40 No. 3 , pp. 345 - 369 .

Bundy , J. , Pfarrer , M.D. , Short , C.E. and Coombs , W.T. ( 2017 ), “ Crises and crisis management: integration, interpretation, and research development ”, Journal of Management , Vol. 43 No. 6 , pp. 1661 - 1692 .

Choi , S. , Cho , I. , Han , S.H. , Kwak , Y.H. and Chih , Y.Y. ( 2018 ), “ Dynamic capabilities of project-based organization in global operations ”, Journal of Management in Engineering , Vol. 34 No. 5 , 04018027 .

Christianson , M.K. , Farkas , M.T. , Sutcliffe , K.M. and Weick , K.E. ( 2009 ), “ Learning through rare events: significant interruptions at the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Museum ”, Organization Science , Vol. 20 No. 5 , pp. 846 - 860 .

Claeys , A.S. and Cauberghe , V. ( 2012 ), “ Crisis response and crisis timing strategies: two sides of the same coin ”, Public Relations Review , Vol. 38 No. 1 , pp. 83 - 88 .

Claeys , A.S. and Cauberghe , V. ( 2014 ), “ What makes crisis response strategies work? The impact of crisis involvement and message framing ”, Journal of Business Research , Vol. 67 No. 2 , pp. 182 - 189 .

Clark , E. and Geppert , M. ( 2011 ), “ Subsidiary integration as identity construction and institution building: a political sensemaking approach ”, Journal of Management Studies , Vol. 48 No. 2 , pp. 395 - 416 .

Coleman , L. ( 2004 ), “ The frequency and cost of corporate crises ”, Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management , Vol. 12 No. 1 , pp. 2 - 13 .

Coombs , W.T. ( 1999 ), Ongoing Crisis Communication: Planning, Managing, and Responding , Sage Publications , London .

Cornelissen , J. ( 2012 ), “ Sensemaking under pressure: the influence of professional roles and social accountability on the creation of sense ”, Organization Science , Vol. 23 No. 1 , pp. 118 - 137 .

Cunha , M.P. , Clegg , S.R. and Kamoche , K. ( 2006 ), “ Surprises in management and organization: concept, sources, and a typology ”, British Journal of Management , Vol. 17 No. 4 , pp. 317 - 329 .

Cyert , R. and March , J.G. ( 1963 ), A Behavioral Theory of the Firm , Prentice-Hall , Englewood Cliffs, NJ .

Daft , R.L. and Weick , K.E. ( 1984 ), “ Toward a model of organizations as interpretation systems ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 9 No. 2 , pp. 284 - 295 .

Darling , J.R. ( 1994 ), “ Crisis management in international business: keys to effective decision making ”, Leadership and Organization Development Journal , Vol. 15 No. 8 , pp. 3 - 8 .

Davies , A. , Dodgson , M. and Gann , D. ( 2016 ), “ Dynamic capabilities in complex projects: the case of London Heathrow terminal 5 ”, Project Management Journal , Vol. 47 No. 2 , pp. 26 - 46 .

DeFillipi , R. and Arthur , M. ( 1998 ), “ Paradox in project-based enterprise: the case of film making ”, California Management Review , Vol. 40 No. 2 , pp. 125 - 139 .

DeFillipi , R. and Arthur , M. ( 2002 ), “ Project based learning: embedded learning contexts and the management of knowledge ”, Paper presented at the 3rd European Conference on Organization, Knowledge and Capabilities , Athens, Greece .

Duncan , R.B. and Weiss , A. ( 1978 ), “ Organizational learning: implications for organizational design ”, in Staw , B. (Ed.), Research in Organizational Behavior , pp. 75 - 123 .

Dutton , J.E. ( 1993 ), “ The making of organizational opportunities: an interpretive pathway to organizational change ”, in Cummings , L.L. and Staw , B.M. (Eds), Research in Organizational Behavior , JAI Press , Greenwich, CT , pp. 195 - 226 .

Ebers , M. and Powell , W. ( 2007 ), “ Biotechnology: its origins, organization, and outputs ”, Research Policy , Vol. 36 No. 4 , pp. 433 - 437 .

Edmunds , A. and Morris , A. ( 2000 ), “ The problem of information overload on business organisations: a review of literature ”, International Journal of Information Management , Vol. 20 No. 1 , pp. 17 - 28 .

Elliott , D. and Smith , D. ( 2006 ), “ Patterns of regulatory behavior in the UK football industry ”, Journal of Management Studies , Vol. 43 No. 2 , pp. 291 - 318 .

Elliott , D. and Macpherson , A. ( 2010 ), “ Policy and practice: recursive learning from crisis ”, Group and Organization Management , Vol. 35 No. 5 , pp. 572 - 605 .

Eppler , M.J. and Mengis , J. ( 2004 ), “ The concepts of information overload: a review of literature from organisation science, accounting, marketing, MIS and related disciplines ”, The Information Society , Vol. 20 No. 5 , pp. 325 - 344 .

Farhoomand , A.F. and Drury , D.H. ( 2002 ), “ Managerial information overload ”, Communications of the ACM , Vol. 45 No. 10 , pp. 127 - 131 .

Ferreira , J. , Coelho , A. and Moutinho , L. ( 2020 ), “ Dynamic capabilities, creativity and innovation capability and their impact on competitive advantage and firm performance: the moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation ”, Technovation , Vols 92-93 , 102061 .

Fisher , C.W. , Chengalur-Smith , I. and Ballou , D.P. ( 2003 ), “ The impact of experience and time on the use of data quality information in decision making ”, Information Systems Research , Vol. 14 No. 2 , pp. 170 - 188 .

Geraldi , J.G. , Lee-Kelley , L. and Kutsch , E. ( 2010 ), “ The Titanic sunk, so what? Project manager response to unexpected events ”, International Journal of Project Management , Vol. 28 No. 6 , pp. 547 - 558 .

Gillespie , N. and Dietz , G. ( 2009 ), “ Trust repair after an organization-level failure ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 34 No. 1 , pp. 127 - 145 .

Gillespie , N. , Dietz , G. and Lockey , S. ( 2014 ), “ Organizational reintegration and trust repair after an integrity violation: a case study ”, Business Ethics Quarterly , Vol. 24 No. 3 , pp. 371 - 410 .

Gioia , D.A. and Chittipeddi , K. ( 1991 ), “ Sensemaking and sensegiving in strategic change initiation ”, Strategic Management Journal , Vol. 12 No. 6 , pp. 433 - 448 .

Gonzalez-Herrero , A. and Smith , S. ( 2010 ), “ Crisis communications management 2.0: organizational principles to manage crisis in an online world ”, Organization Development Journal , Vol. 28 No. 1 , pp. 97 - 105 .

Graffin , S.D. , Haleblian , J. and Kiley , J.T. ( 2016 ), “ Ready, aim, acquire: impression offsetting and acquisitions ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 59 No. 1 , pp. 232 - 252 .

Hällgren , M. and Wilson , T.L. ( 2008 ), “ The nature and management of crises in construction projects: projects as practice observations ”, International Journal of Project Management , Vol. 26 No. 8 , pp. 830 - 838 .

Hällgren , M. and Wilson , T.L. ( 2011 ), “ Opportunities for learning from crises in projects ”, International Journal of Managing Projects in Business , Vol. 4 No. 2 , pp. 196 - 217 .

Haunschild , P.R. and Sullivan , B.N. ( 2002 ), “ Learning from complexity: effects of prior accidents and incidents on airlines' learning ”, Administrative Science Quarterly , Vol. 47 No. 4 , pp. 609 - 643 .

Haunschild , P.R. , Polidoro , F. Jr. and Chandler , D. ( 2015 ), “ Organizational oscillation between learning and forgetting: the dual role of serious errors ”, Organization Science , Vol. 26 No. 6 , pp. 1682 - 1701 .

Hedberg , B. ( 1981 ), “ How organizations learn and unlearn ”, in Nystrom , P.C. and Starbuck , W.H. (Eds), Handbook of Organizational Design: Adapting Organizations to Their Environments , Oxford University Press , New York , pp. 3 - 26 .

Helfat , C.E. , Finkelstein , S. , Mitchell , W. , Peteraf , M. , Singh , H. , Teece , D. and Winter , S.G. ( 2007 ), Dynamic Capabilities: Understanding Strategic Change in Organizations , Blackwell , Oxford .

Hermann , C.F. ( 1963 ), “ Some consequences of crisis which limit the viability of organizations ”, Administrative Science Quarterly , Vol. 8 No. 1 , pp. 61 - 82 .

Himma , H.E. ( 2007 ), “ The concept of information overload: a preliminary step in understanding the nature of a harmful information-related condition ”, Ethics and Information Technology , Vol. 9 No. 4 , pp. 259 - 272 .

Hobday , M. ( 2000 ), “ The project-based organization: an ideal form for managing complex products and systems ”, Research Policy , Vol. 29 Nos 7-8 , pp. 871 - 893 .

Houhamdi , Z. and Athamena , B. ( 2015 ), “ Information quality framework ”, Global Business and Economics Anthology , Vol. 1 , pp. 182 - 191 .

Hsieh , H.-F. and Shannon , S.E. ( 2005 ), “ Three approaches to qualitative content analysis ”, Qualitative Health Research , Vol. 15 No. 9 , pp. 1277 - 1288 .

Hung , R.Y.Y. , Yang , B. , Lien , B.Y.H. , McLean , G.N. and Kuo , Y.M. ( 2010 ), “ Dynamic capability: impact of process alignment and organizational learning culture on performance ”, Journal of World Business , Vol. 45 No. 3 , pp. 285 - 294 .

Hussain , H.H. ( 2019 ), “ Evaluating the effectiveness of crisis management projects ”, Tikrit Journal of Administrative and Economic Sciences , Vol. 13 No. 37 , pp. 210 - 218 .

Iftikhar , R. and Müller , R. ( 2019 ), “ Taxonomy among triplets: opening the black box ”, International Journal of Management , Vol. 10 No. 2 , pp. 63 - 85 .

Iftikhar , R. , Müller , R. and Ahola , T. ( 2021 ), “ Crises and coping strategies in megaprojects: the case of the islamabad–rawalpindi metro bus project in Pakistan ”, Project Management Journal , Vol. 52 No. 4 , pp. 394 - 409 .

Iftikhar , R. , Momeni , K. and Ahola , T. ( 2022a ), “ Decision-making in crisis during megaprojects ”, The Journal of Modern Project Management , Vol. 9 No. 3 , pp. 33 - 49 .

Iftikhar , R. ( 2023 ), “ Crises and capabilities in project-based organizations: conceptual model and empirical evidence ”, International Journal of Managing Projects in Business , Vol. 16 No. 3 , pp. 543 - 570 .

Iftikhar , R. , Ahola , T. and Butt , A. ( 2022b ), “ Learning from interorganizational projects ”, International Journal of Managing Projects in Business , Vol. 15 No. 1 , pp. 102 - 120 .

Iftikhar , R. and Wiewiora , A. ( 2022 ), “ Learning processes and mechanisms for interorganizational projects: insights from the Islamabad–Rawalpindi metro bus project ”, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management , Vol. 69 No. 6 , pp. 3379 - 3391 .

Jaques , T. ( 2009 ), “ Issue management as a post-crisis discipline: identifying and responding to issue impacts beyond the crisis ”, Journal of Public Affairs , Vol. 9 No. 1 , pp. 35 - 44 .

Jiang , Y. , Ritchie , B.W. and Verreynne , M.L. ( 2019 ), “ Building tourism organizational resilience to crises and disasters: a dynamic capabilities view ”, International Journal of Tourism Research , Vol. 21 No. 6 , pp. 882 - 900 .

Kahn , W.A. , Barton , M.A. and Fellows , S. ( 2013 ), “ Organizational crises and the disturbance of relational systems ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 38 No. 3 , pp. 377 - 396 .

Kamoche , K. ( 2003 ), “ Riding the typhoon: the HR response to the economic crisis in Hong Kong ”, International Journal of Human Resource Management , Vol. 14 No. 2 , pp. 199 - 221 .

Keeffe , M.J. and Darling , J.R. ( 2008 ), “ Transformational crisis management of organization development: the case of talent loss at Microsoft ”, Organization Development Journal , Vol. 26 No. 4 , pp. 43 - 58 .

Keegan , W.J. ( 1974 ), “ Multinational scanning: a study of information sources utilized by headquarters executives in multinational companies ”, Administrative Science Quarterly , Vol. 19 No. 3 , pp. 411 - 421 .

Keegan , A. and Turner , J.R. ( 2001 ), “ Quantity versus quality in project based learning practices ”, Management Learning , Vol. 32 No. 1 , pp. 77 - 98 .

Killen , C.P. and Hunt , R.A. ( 2010 ), “ Dynamic capability through project portfolio management in service and manufacturing industries ”, International Journal of Managing Projects in Business , Vol. 3 No. 1 , pp. 157 - 169 .

Knight , F.H. ( 1921 ), Risk, Uncertainty and Profit , Hart, Schaffner & Marx; Houghton Mifflin , Boston, MA .

Kornberger , M. , Leixnering , S. and Meyer , R.E. ( 2019 ), “ The logic of tact: how decisions happen in situations of crisis ”, Organization Studies , Vol. 40 No. 2 , pp. 239 - 266 .

Kutsch , E. and Hall , M. ( 2005 ), “ Intervening conditions on the management of project risk: dealing with uncertainty in information technology projects ”, International Journal of Project Management , Vol. 23 No. 8 , pp. 591 - 599 .

Lacombe , P. ( 2002 ), “ Agronomic research and research into crisis situation ”, Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management , Vol. 10 No. 4 , pp. 205 - 206 .

Lampel , J. , Shamsie , J. and Shapira , Z. ( 2009 ), “ Experiencing the improbable: rare events and organizational learning ”, Organization Science , Vol. 20 No. 5 , pp. 835 - 845 .

Lanham , R.A. ( 2006 ), The Economics of Attention: Style and Substance in the Age of Information , University of Chicago Press , Chicago .

Leung , L. and Law , N. ( 2016 ), “ Exploring the effectiveness of online role play simulations in tackling groupthink in crisis management training ”, International Journal of Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations , Vol. 8 No. 3 , pp. 1 - 18 .

Li , H. , Nair , A. , Song , M. , Tian , Y. and Singh , P.J. ( 2018 ), “ Uncovering the relationship between organizational crisis and innovation speed ”, Academy of Management Proceedings , Vol. 2018 No. 1 , 11413 .

Liberatore , A. ( 2013 ), The Management of Uncertainty: Learning from Chernobyl , Routledge , London .

Lin , Z. , Zhao , X. , Ismail , K.M. and Carley , K.M. ( 2006 ), “ Organizational design and restructuring in response to crises: lessons from computational modelling and real-world cases ”, Organization Science , Vol. 17 No. 5 , pp. 598 - 618 .

Locatelli , G. and Mancini , M. ( 2010 ), “ Risk management in a mega-project: the universal Expo 2015 case ”, International Journal of Project Organizations and Management , Vol. 2 No. 3 , pp. 236 - 253 .

Loosemore , M. ( 1998 ), “ The three ironies of crisis management in construction projects ”, International Journal of Project Management , Vol. 16 No. 3 , pp. 139 - 144 .

Loosemore , M. ( 2000 ), Crisis Management in Construction Projects , American Society of Civil Engineers , Reston .

Loosemore , M. and Teo , M. ( 2000 ), “ Crisis preparedness of construction companies ”, Journal of Management in Engineering , Vol. 16 No. 5 , pp. 60 - 65 .

Louis , M.R. ( 1980 ), “ Surprise and sensemaking: what newcomers experience in entering unfamiliar settings ”, Administrative Science Quarterly , Vol. 25 No. 2 , pp. 226 - 251 .

Lundin , R.A. and Söderholm , A. ( 1995 ), “ A theory of temporary organization ”, Scandinavian Journal of Management , Vol. 11 No. 4 , pp. 437 - 455 .

Madsen , P.M. ( 2009 ), “ These lives will not be lost in vain: organizational learning from disaster in U.S. coal mining ”, Organization Science , Vol. 20 No. 5 , pp. 861 - 875 .

Maitlis , S. ( 2005 ), “ The social processes of organizational sense making ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 48 No. 1 , pp. 21 - 29 .

Mallak , L.A. and Kurstedt , H.S. Jr. ( 1997 ), “ Planning for crises in project management ”, Project Management Journal , Vol. 28 No. 2 , pp. 14 - 24 .

Mandler , G. ( 1984 ), Mind and Body , Free Press , New York .

Mansour , H.E. , Holmes , K. , Butler , B. and Ananthram , S. ( 2019 ), “ Developing dynamic capabilities to survive a crisis: tourism organizations' responses to continued turbulence in Libya ”, International Journal of Tourism Research , Vol. 21 No. 4 , pp. 493 - 503 .

Mayr , S. , Duller , C. and Königstorfer , M. ( 2022 ), “ How to manage a crisis: entrepreneurial and learning orientation in out-of-court reorganization ”, Journal of Small Business Strategy , Vol. 32 No. 2 , pp. 11 - 24 .

McAfee , A. and Brynjolfsson , E. ( 2012 ), “ Big data: the management revolution ”, Harvard Business Review , Vol. 90 No. 10 , pp. 60 - 68 .

Meyer , A.D. ( 1982 ), “ Adapting to environmental jolts ”, Administrative Science Quarterly , Vol. 27 No. 4 , pp. 515 - 537 .

Meyer , D.A. , Loch , H.C. and Pich , T.M. ( 2002 ), “ Managing project uncertainty: from variation to chaos ”, MIT Sloan Management Review , Vol. 43 No. 2 , pp. 60 - 67 .

Middleton , C.J. ( 1967 ), “ How to set up a project organization ”, Harvard Business Review , Vol. 45 No. 2 , pp. 73 - 82 .

Midler , C. ( 1995 ), “ Projectification of the firm: the Renault case ”, Scandinavian Journal of Management , Vol. 11 No. 4 , pp. 363 - 375 .

Miller , D. and Friesen , P.H. ( 1984 ), Organization: A Quantum View , Prentice-Hall , Englewood Cliffs, NJ .

Milliken , F.J. ( 1990 ), “ Perceiving and interpreting environmental change: an examination of college administrators' interpretation of changing demographics ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 33 No. 1 , pp. 42 - 63 .

Miner , A. and Robinson , D. ( 1994 ), “ Organizational and population level learning as engines for career transitions ”, Journal of Organizational Behavior , Vol. 15 No. 4 , pp. 345 - 364 .

Mitroff , I.I. ( 1994 ), “ Crisis management and environmentalism: a natural fit ”, California Management Review , Vol. 36 No. 2 , pp. 101 - 113 .

Mitroff , I.I. , Shrivastava , P. and Udwadia , F.E. ( 1987 ), “ Effective crisis management ”, Academy of Management Executive , Vol. 1 No. 4 , pp. 283 - 292 .

Mitroff , I.I. , Pauchant , T.C. and Shrivastava , P. ( 1988 ), “ The structure of man-made organizational crises: conceptual and empirical issues in the development of a general theory of crisis management ”, Technological Forecasting and Social Change , Vol. 33 No. 2 , pp. 83 - 107 .

Monin , P. , Noorderhaven , N. , Vaara , E. and Kroon , D. ( 2013 ), “ Giving sense to and making sense of justice in postmerger integration ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 56 No. 1 , pp. 256 - 284 .

Musca , G.N. , Mellet , C. , Simoni , G. , Sitri , F. and de Vogüé , S. ( 2014 ), “ Drop your boat!: the discursive co-construction of project renewal. the case of the Darwin mountaineering expedition in Patagonia ”, International Journal of Project Management , Vol. 32 No. 7 , pp. 1157 - 1169 .

Najafbagy , R. ( 2011 ), “ The crisis management capabilities and preparedness of organizations: a study of Iranian Hospital ”, International Journal of Management , Vol. 28 No. 2 , pp. 573 - 584 .

Oh , O. , Agrawal , M. and Rao , H.R. ( 2013 ), “ Community intelligence and social media services: a rumor theoretical analysis of tweets during social crisis ”, MIS Quarterly , Vol. 37 No. 2 , pp. 407 - 426 .

Olaniran , B.A. , Scholl , J.C. , Williams , D.E. and Boyer , L. ( 2012 ), “ Johnson and Johnson phantom recall: a fall from grace or a re-visit of the ghost of the past ”, Public Relations Review , Vol. 38 No. 1 , pp. 153 - 155 .

Orlikowski , W.J. and Gash , D.C. ( 1994 ), “ Technological frames: making sense of information technology in organizations ”, ACM Transactions Information Systems , Vol. 12 No. 2 , pp. 174 - 207 .

Patil , M.S.N. , Desai , D.B. and Gupta , A.K. ( 2016 ), “ An overview of crisis management in Housing project ”, Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research , Vol. 2 No. 7 , pp. 886 - 889 .

Patriotta , G. ( 2003 ), “ Sensemaking on the shop floor: narratives of knowledge in organizations ”, Journal Management Studies , Vol. 40 No. 2 , pp. 349 - 376 .

Pearce , J.A. and Michael , S.C. ( 2006 ), “ Strategies to prevent economic recessions from causing business failure ”, Business Horizons , Vol. 49 No. 3 , pp. 201 - 209 .

Pearson , C.M. and Clair , J.A. ( 1998 ), “ Reframing crisis management ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 23 No. 1 , pp. 59 - 76 .

Pearson , C.M. and Mitroff , I.I. ( 1993 ), “ From crisis prone to crisis prepared: a framework for crisis management ”, Academy of Management Executive , Vol. 7 No. 1 , pp. 48 - 59 .

PMI ( 2004 ), A Guide to Project Management Body of Knowledge , 3rd ed. , Project Management Institute , Newtown Square .

Ponis , S.T. and Koronis , E. ( 2012 ), “ A knowledge management process-based approach to support corporate crisis management ”, Knowledge and Process Management , Vol. 19 No. 3 , pp. 148 - 159 .

Pourbabaei , H. , Tabatabaei , M. , Jalalian , Z. and Afrazeh , A. ( 2015 ), “ Crisis management through creating and transferring knowledge in project-based organizations ”, Journal of Applied Environmental and Biological Science , Vol. 5 No. 5S , pp. 204 - 210 .

Porac , J. , Thomas , H. and Baden-Fuller , C. ( 1989 ), “ Competitive groups as cognitive communities: the case of Scottish knitwear manufacturers ”, Journal of Management Studies , Vol. 26 No. 4 , pp. 397 - 416 .

Prencipe , A. and Tell , F. ( 2001 ), “ Inter-project learning: processes and outcomes of knowledge codification in project-based firms ”, Research Policy , Vol. 30 No. 9 , pp. 1373 - 1394 .

Pun , K.F. ( 2005 ), “ An empirical investigation of strategy determinants and choices in manufacturing enterprises ”, Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management , Vol. 16 No. 3 , pp. 282 - 301 .

Ray , S.J. ( 1999 ), Strategic Communication in Crisis Management: Lessons from the Airline Industry , Quorum Books , London .

Rerup , C. ( 2009 ), “ Attentional triangulation: learning from unexpected rare crisis ”, Organization Science , Vol. 20 No. 5 , pp. 876 - 893 .

Roberts , K. ( 1989 ), “ New challenges in organizational research: high reliability organizations ”, Industrial Crisis Quarterly , Vol. 3 No. 2 , pp. 111 - 125 .

Roberts , K.H. ( 1990 ), “ Some characteristics of one type of high reliability organization ”, Organization Science , Vol. 1 No. 2 , pp. 160 - 176 .

Rudolph , J.W. , Morrison , J.B. and Carroll , J.S. ( 2009 ), “ The dynamics of action-oriented problem solving: linking interpretation and choice ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 34 No. 4 , pp. 733 - 756 .

Sahebalzamani , S. , Jørgensen , E.J.B. , Bertella , G. and Nilsen , E.R. ( 2023 ), “ A dynamic capabilities approach to business model innovation in times of crisis ”, Tourism Planning and Development , Vol. 20 No. 2 , pp. 138 - 161 .

Sangaiah , A.K. , Samuel , O.W. , Li , X. , Abdel-Basset , M. and Wang , H. ( 2018 ), “ Towards an efficient risk assessment in software projects–fuzzy reinforcement paradigm ”, Computers and Electrical Engineering , Vol. 71 , pp. 833 - 846 .