FREE SHIPPING FOR ORDERS P3,000 & UP | WE SHIP NATIONWIDE

10% OFF ON ALL BOOKS! Discount Code: HAPPY12

Item added to your cart

Online or offline reading: which is better for learning.

In today's digital world, many of us are turning to online sources for reading materials, but is it really the best way to learn? Is online or offline reading better for learning? In this blog post, we'll examine the pros and cons of both online and offline reading to see which one is better for learning. We'll also take a look at some of the research that has been done to better understand the differences between these two methods. Finally, we'll provide some tips on how to make the most of either approach so that you can maximize your learning potential.

Advantages of Online Reading

This blog post will focus on the advantages of reading online. By reading online, one can access a much larger library of information than is available through traditional offline sources like books and newspapers. Additionally, the internet provides access to a wealth of resources that are up-to-date and relevant to the topics you are studying. This can make it easier to stay current on the latest developments in your field.

Online reading also provides a more interactive learning experience than traditional offline reading. For example, you can use online forums and discussion boards to interact with experts in your field and ask questions that can help you better understand the material. Additionally, many online resources feature multimedia content like videos and audio recordings that can help enhance your understanding of a particular subject. Finally, some online reading materials feature interactive tools and activities that can help you practice and reinforce what you’ve learned. These tools can also be helpful for taking notes and keeping track of your progress.

Disadvantages of Online Reading

One of the major disadvantages of online reading is the lack of focus and concentration. When we read online, we’re often bombarded with ads, pop-ups, and other distractions. Studies have found that when people read on a screen they tend to skim more, which can lead to a less complete understanding of the material. Additionally, online readers tend to become easily distracted and lose focus if they are interrupted or need to switch tasks.

Furthermore, online readers may be prone to reading more quickly than they would offline. This is because they can scan the text and jump from one point to the next without taking the time to fully absorb the material. This can lead to a lack of comprehension and lead to misunderstandings of the material. Studies have also shown that when people read online, they often take shortcuts when searching for information and may not even read the entire text.

Finally, the quality of the material that you can access online is often questionable. With the prevalence of fake news and inaccurate information, it can be difficult to ascertain the reliability and accuracy of the content. Additionally, the quality of the visuals and graphics on a website can vary greatly, making it difficult to effectively learn from the material.

Advantages of Offline Reading

One of the biggest advantages of offline reading is that it is a more reliable and secure way to read. When you're reading offline, you don't need to worry about your connection dropping or your device experiencing a power outage. Plus, you don't need to worry about your data being stolen or hacked, as is possible with online reading.

Another advantage of offline reading is that it helps you to be more focused and engaged. When you're reading from a physical book or magazine, you can stay in the moment, undistracted by notifications or pop-ups from the internet. Furthermore, when you're reading from a physical book or magazine, you can take notes, highlight important passages, or even write down your own thoughts and insights.

Last but not least, offline reading can also help to reduce eye strain. When you read from a digital device, like a laptop or tablet, the blue light emitted by the screen can put a strain on your eyes. However, when you're reading from a physical book or magazine, you won't experience this same strain. In addition, offline reading can be a more pleasurable experience, as the feeling of flipping through a physical book or magazine can be calming.

Disadvantages of Offline Reading

One of the main disadvantages of offline reading is its lack of interactivity. Unlike online reading, which often has interactive elements like videos, quizzes, and games, offline reading is a much more passive activity. This can be a major limitation for learners who need more immediate feedback and reinforcement to fully understand and retain new information. Additionally, offline reading materials can quickly become outdated. As new information is published, reading material in books and magazines can quickly become obsolete, so readers must be sure to keep up with the latest information if they want to stay current.

Another disadvantage of offline reading is its limited scope. Because offline reading materials are often limited to one specific topic, it can be difficult for readers to get a broader understanding of a subject. Additionally, offline reading materials tend to be more expensive than online materials, so readers may be limited in the amount of content they can access. Finally, the material available in offline reading sources may be limited by the physical space, making it difficult to find the exact material needed.

Overall, while offline reading can be beneficial, its lack of interactivity, limited scope, and higher cost can make it less effective than online reading for many learners.

Research-Backed Insights on Online and Offline Reading

Online reading has become a popular way to access information in the digital age. It has made it easier and faster to find what you need quickly. Plus, reading online often offers more interactive elements such as videos, audio, and interactive quizzes. However, research has found that reading online is not always the best way to learn. Studies have shown that reading online can leave readers with shorter attention spans, are more easily distracted, and are likely to forget what they’ve read more quickly.

Offline reading has been around for centuries and remains an important way to learn. It has been proven to support more meaningful learning that sticks with readers longer. Physical books are more likely to be read in their entirety as well as be revisited at a later date. The tactile nature of physical books can also be more engaging and immersive.

Studies also show that the best way to learn is to use a combination of both online and offline reading. The combination of the two can be beneficial for information retention, comprehension, and overall learning. Using online sources to supplement physical books can help readers increase their knowledge and better understand the material. Additionally, online sources like videos and podcasts can provide a different perspective on the subject and can be used to further reinforce what has been learned.

Tips for Making the Most of Online and Offline Reading

Online reading has become increasingly popular in recent years, due to the vast amount of information available on the internet. However, the more traditional form of reading offline has been around for centuries, and both methods have their advantages and disadvantages when it comes to learning.

When reading online, the convenience and accessibility of the material is one major advantage. Moreover, the wealth of resources, multimedia content, and interactivity of the web make it easier to engage in the material and learn more effectively. On the other hand, offline reading can provide a more focused environment to read the material, and can also be easier on the eyes due to the lack of screens and computer monitors.

In order to make the most of either online or offline reading, it is important to create an effective learning environment. This means setting aside a quiet, distraction-free space where you can focus on the material, as well as setting a specific time each day for studying. Additionally, it can be helpful to break down the material into manageable chunks in order to ensure that you are comprehending the information and retaining it for later use. Finally, taking notes while reading can help you to easily review and recall the material at a later date.

Leave a comment

Please note, comments need to be approved before they are published.

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

Online Reading or Offline? Which is Better for Learning? (2024)

Reading is undoubtedly the gateway to freedom. There has only been one avenue for reading for centuries: on paper.

That said, the digital age has opened the floodgates to information via the internet, and with over 85.88% of the world’s population owning smartphones, online reading has become the new normal.

The recent pandemic also played a significant role in thrusting the education systems worldwide into the digital realm, and this move was made possible by digital publishing platforms like KITABOO .

Table of Contents:

I. Types of Reading – A Brief

II. Offline Reading

The Advantages of Offline Reading

The downsides of offline reading.

III. Online Reading

The Advantages of Reading Online

The downsides of online reading.

IV. Is it Better to Read from Books or Online?

Types of Reading - A Brief

Learning a language is the beginning of how we do almost everything in life. Even though reading comes third in terms of LSRW (listening, speaking, reading, and writing) skills when it comes to learning a new language, it gains the top spot in the field of education.

Most people subconsciously approach reading in two primary ways depending on what they are reading, which are:

- Extensive Reading : This technique is used when the reader is simply reading for pleasure. There is no aim or object here, and nor is the reader overly focused on the details.

- Scanning : This is a technique where one reads quickly through a large block of text while looking for specific keywords or pieces of information.

- Skimming : Skimming is a technique where you quickly glance through text to understand what the text is about.

- Critical Reading : Critical Reading is a technique used when a reader intends to understand the intricacies of what they are reading. This form of reading is all about analysis and is key to understanding complex information.

With this in mind, let’s dive into the nitty-gritty of offline and online reading.

Offline Reading

Let’s start with the obvious. No matter how intertwined we get with technology, it can never replace offline reading, and this holds true, especially in the field of education.

Reading and writing are a critical part of education and will continue to be into the future. While the benefits of online reading do exceed offline reading, it still has a few aces up its sleeve.

Although considered old-fashioned, offline reading does boast numerous advantages, such as:

Well, It’s Offline

As the title suggests, good old-fashioned books do not require an internet connection. With this comes the added advantage of not having a device to read from that can be hacked, broken, or worry about running out of juice.

Better Focus Due to Minimal Distractions

Offline reading allows for higher levels of focus due to minimal distractions.

With smart devices comes a barrage of notifications and the temptation to switch to a different app. When you sit with a book, you sit with the intention to read, and you automatically switch into an intensive reading mode.

You Get a Break from Screens

Most of us spend a large chunk of our day staring at either a smartphone, a laptop, or a television. This can put a significant amount of strain on one’s eyes.

But when it comes to offline reading, as long as you are reading in a well-lit space, you don’t strain your eyes as much.

Offline reading does have its downsides as well, such as:

A Lack of Interactivity

Reading large chunks of text can get mundane over a period of time. Add to this the fact that not every one of us learns best from reading and you can see how its merits start to drop.

Statistics show that over 65% of the world’s population are visual learners. Relying only on offline learning leaves a large chunk of the student population at a disadvantage.

Offline Reading is Limited in its Scope

Offline reading limits your scope of knowledge to the book or books you access to. Unless you have access to a library, getting more information solely from books can be an expensive endeavor.

Online Reading

Based on the current landscape, it is evident that digital content creation is going to continue into the foreseeable future.

Reading online has become the go-to option for getting the latest news, reading up on new topics, and, since the pandemic, a large part of the education system.

So, how does reading online fare in comparison to reading offline? Let’s find out.

Reading online has changed the very fabric of how we consume and interact with information. With it comes a host of advantages, such as:

Access to All the Information in the World

Online reading gives you access to infinite amounts of information, which, unlike offline reading materials, can be up to date with the latest information.

You no longer need to buy additional books or run to the library and spend additional time and effort looking for relevant sources of information.

It is a Multimedia-Rich and Interactive Experience

Depending on the source material, online reading can be infused with multimedia-rich elements that are proven to make comprehension of complex topics easier and boost knowledge retention.

The interactive nature of these materials also leads to higher engagement levels in students.

Improves Scanning and Skimming Reading Skills

Reading online is often visually cluttered, and readers scan and skim more often to find the necessary information.

As a result, readers tend to develop these skills quickly to identify the key information and ignore the less important details.

Online Reading is More Accessible

Reading online transcends the limitation of offline reading when it comes to accessibility.

Whether a reader is visually impaired or hard of hearing, online reading has technology like Closed Captions and text-to-speech to overcome them.

Also Read: Best eBook Creation Softwares

As with everything, there is always a flip side, which also holds true for online reading. Here are the disadvantages of reading online:

Too Many Distractions

Reading online does come with several distractions in the form of ads, pop-up notifications, and social media, to name a few, which can make it difficult to focus on the task at hand.

Due to this, studies have often found that readers then skim rather than critically read online.

The Health Implications

Staring at a screen for extended periods puts a lot of strain on one’s eyes. You can also strain your neck or back if you do not maintain a proper posture while spending extended time on online devices.

Is it Better to Read from Books or Online?

Reading online does pull ahead of reading offline in terms of its benefits. However, there is no one correct answer to this question.

Instead of an either this or that approach, the best possible course of action is to maintain a careful balance of both, especially in the field of education. That way, readers reap both forms’ benefits while negating each other’s downsides.

If you prefer reading online and want to help create or read eBooks, you should check out KITABOO. They are a cloud-based platform that supports various digital publishing needs. Explore now to know more.

Contact our expert team now and get started!

To know more, please write to us at [email protected] .

Suggested Reads:

- Advantages of ePUB over PDF

- Create a Custom eBook App to Reach a Wider Audience

- What is eBook DRM and Why Do Publishers Need it?

- Role of Technology in the Workplace

- Best eBook Hosting Platforms for Digital Publishing

- Create Effective Interactive Training Content

- Evaluate Training Effectiveness and Impact

Discover How An Ebook Conversion, Publishing & Distribution Platform Can Help You

Kitaboo is a cloud-based content platform to create-publish & securely distribute interactive mobile-ready ebooks.

You May Also Like

8 Top interactive learning software for online education (2024)

Digital Publishing , eBook solution / March 18, 2024

Learning Management Systems: eLearning Training Solutions

Blog , Digital Publishing , eBook solution / March 10, 2024

Epub Book: Best Practices in 2024

Blog , Digital Publishing , eBook solution , Education Technology / December 13, 2023

Mike Harman

Mike is the SVP Business Development at HurixDigital. He has over 30 years experience in achieving consistent top-line revenue growth and building mutually beneficial relationships

More Resources

- Whitepapers

- How To Guides

- Product Videos

- Infographics

- Kitaboo FAQs

Request a Demo

An enterprise platform that 15 million users trust

Kitaboo Product Video

Recent Posts

How Do I Create an ePub From a Document?: A Step-by-Step Tutorial

Are Digital Textbooks Worth It?

Interactive Content Builder: Unleashing the Power of Engaging Content

The Best ePUB Readers for Windows (2024)

- Digital Publishing

- eBook solution

- eBook Store

- Education Technology

- Employee Training

- ePUB Conversion

- Frankfuter Buchmesse

- Nonprofit Organizations & Associations

- Self-publishing

- Uncategorized

- XML Conversion

Get the latest posts delivered right to your email.

Sign up to Newsletter

Press & media.

- Press Releases

- News Section

Quick links

- About Hurix Systems

- KITABOO for K12 Publishers

- KITABOO for Associations and Non-profit

- KITABOO for Higher Education Publishers

- Digital Content Solutions – HurixDigital

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

Resources Links

- Product videos

- Kitaboo Partner Program

Kitaboo Reader

- Convert Fixed PDF / InDesign to Dynamic Content

- Training Solutions

- Online Reader

- Android App

- Windows Store Installer

- Mac Store Installer

- Kitaboo SDK

- Case Studies

- Request A Demo

Privacy Overview

It’s a wonderful world — and universe — out there.

Come explore with us!

Science News Explores

Will you learn better from reading on screen or on paper.

One size doesn’t fit all situations. But for now, experts say, don’t throw away your books

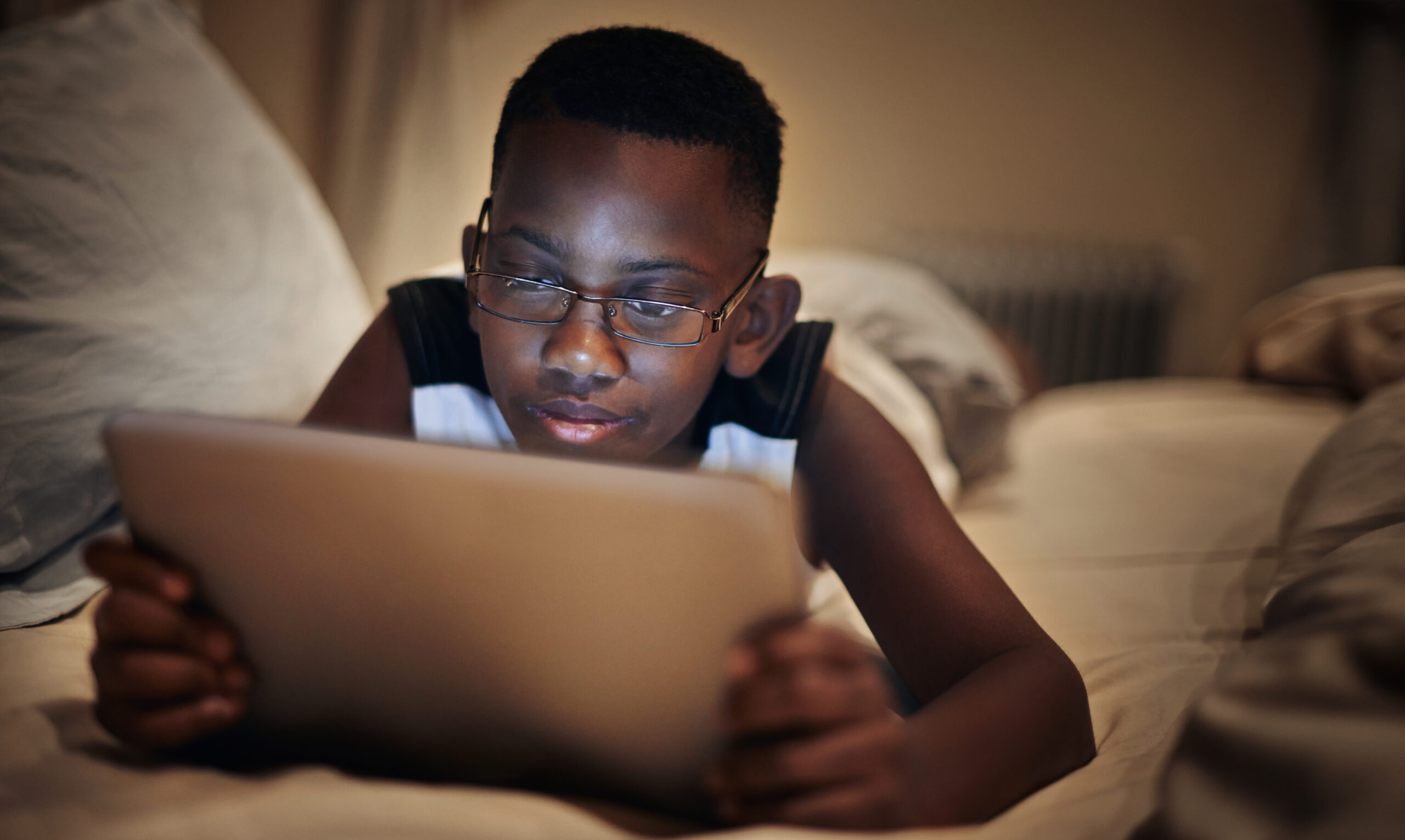

Computers are very much a part of education today. But books and paper are still a good way to learn information. Depending on the material, they can be the easiest way, studies find.

Carol Yepes/Moment/Getty Images Plus

Share this:

- Google Classroom

By Avery Elizabeth Hurt

October 18, 2021 at 6:30 am

Want to know the current population of India? The internet is your best bet. Need a quick refresher on the phases of the moon ? Go ahead, read a story online (or two or three). But if you really need to learn something, you’re probably better off with print. Or at least that’s what a lot of research now suggests.

Many studies have shown that when people read on-screen, they don’t understand what they’ve read as well as when they read in print. Even worse, many don’t realize they’re not getting it. For example, researchers in Spain and Israel took a close look at 54 studies comparing digital and print reading. Their 2018 study involved more than 171,000 readers. Comprehension, they found, was better overall when people read print rather than digital texts. The researchers shared the results in Educational Research Review .

Patricia Alexander is a psychologist at the University of Maryland in College Park. She studies how we learn. Much of her research has delved into the differences between reading in print and on-screen. Alexander says students often think they learn more from reading online. When tested, though, it turns out that they actually learned less than when reading in print.

The question is: Why?

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Reading is reading, right? Not exactly. Maryanne Wolf works at the University of California, Los Angeles. This neuroscientist specializes in how the brain reads. Reading is not natural, she explains. We learn to talk by listening to those around us. It’s pretty automatic. But learning to read takes real work. Wolf notes it’s because the brain has no special network of cells just for reading.

To understand text, the brain borrows networks that evolved to do other things. For example, the part that evolved to recognize faces is called into action to recognize letters. This is similar to how you might adapt a tool for some new use. For example, a coat hanger is great for putting your clothes in the closet. But if a blueberry rolls under the refrigerator, you might straighten out the coat hanger and use it to reach under the fridge and pull out the fruit. You’ve taken a tool made for one thing and adapted it for something new. That’s what the brain does when you read.

It’s great that the brain is so flexible. It’s one reason we can learn to do so many new things. But that flexibility can be a problem when it comes to reading different types of texts. When we read online, the brain creates a different set of connections between cells from the ones it uses for reading in print. It basically adapts the same tool again for the new task. This is like if you took a coat hanger and instead of straightening it out to fetch a blueberry, you twisted it into a hook to unclog a drain. Same original tool, two very different forms.

As a result, the brain might slip into skim mode when you’re reading on a screen. It may switch to deep-reading mode when you turn to print.

That doesn’t just depend on the device, however. It also depends on what you assume about the text. Naomi Baron calls this your mindset. Baron is a scientist who studies language and reading. She works at American University in Washington, D.C. Baron is the author of How We Read Now , a new book about digital reading and learning. She says one way mindset works is in anticipating how easy or hard we expect the reading to be. If we think it will be easy, we might not put in much effort.

Much of what we read on-screen tends to be text messages and social-media posts. They’re usually easy to understand. So, “when people read on-screen, they read faster,” says Alexander at the University of Maryland. “Their eyes scan the pages and the words faster than if they’re reading on a piece of paper.”

But when reading fast, we may not absorb all the ideas as well. That fast skimming, she says, can become a habit associated with reading on-screen. Imagine that you turn on your phone to read an assignment for school. Your brain might fire up the networks it uses for skimming quickly through TikTok posts. That’s not helpful if you’re trying to understand the themes in that classic book, To Kill a Mockingbird . It also won’t get you far if you’re preparing for a test on the periodic table .

Where was I?

Speed isn’t the only problem with reading on screens. There’s scrolling, too. When reading a printed page or even a whole book, you tend to know where you are. Not just where you are on some particular page, but which page — potentially out of many. You might, for instance, remember that the part in the story where the dog died was near the top of the page on the left side. You don’t have that sense of place when some enormously long page just scrolls past you. (Though some e-reading devices and apps do a pretty good job of simulating page turns.)

Why is a sense of page important? Researchers have shown that we tend to make mental maps when we learn something. Being able to “place” a fact somewhere on a mental map of the page helps us remember it.

It’s also a matter of mental effort. Scrolling down a page takes a lot more mental work than reading a page that’s not moving. Your eyes don’t just focus on the words. They also have to keep chasing the words as you scroll them down the page.

Mary Helen Immordino-Yang is a neuroscientist at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. She studies how we read. When your mind has to keep up with scrolling down a page, she says, it doesn’t have a lot of resources left for understanding what you’re reading. This can be especially true if the passage you’re reading is long or complicated. While scrolling down a page, your brain has to continually account for the placement of words in your view. And this can make it harder for you to simultaneously understand the ideas those words should convey.

Alexander found that length matters, too. When passages are short, students understand just as much of what they read on-screen as do when reading in print. But once the passages are longer than 500 words, they learn more from print.

Even genre matters. Genre refers to what type of book or article you’re reading. The articles here on Science News for Students are nonfiction. News stories and articles about history are nonfiction. Stories invented by an author are fiction. The Harry Potter books are fiction, for example. So are Song for a Whale and A Wrinkle in Time .

In How We Read Now , Baron reviewed much of the research that’s been published about reading online. Most studies showed people understand nonfiction better when they read it in print. How it affects the understanding of fictional accounts is less clear.

Jenae Cohn works at California State University, Sacramento. Her work focuses on the use of technology in education. This past June, she published a book about digital reading: Skim, Dive, Surface . The biggest problem may not be the words on the screen, she finds. It’s the other things that pop up and get in the way of reading. It can be difficult to concentrate when something interrupts you every few minutes. She’s referring to pings and rings from texts or emails, pop-up advertisements and TikTok updates. All can quickly ruin concentration. Links and boxes that are meant to add to your understanding can be a problem, too. Even when they’re meant to be helpful, some can prove a distraction from what you’re reading.

Not all bad

If you want to do better in school (and who doesn’t?), it’s not quite as simple as turning off your tablet and picking up a book. There are plenty of good reasons to read on screens.

As the pandemic taught us, sometimes we have no choice. When libraries and bookstores close or it’s dangerous to visit them, digital reading can be a lifesaver. Expense is also an important factor. Digital books usually cost less than print ones. And, of course, you have to consider the environmental advantages of digital. It doesn’t take trees to make a digital book.

Digital reading has other advantages, too. In most cases, when you’re reading on-screen you can adjust the size of the letters. You also can change the background color and maybe the typeface. This is a huge help for people who don’t see well. It’s also useful for people with reading disabilities. People who have dyslexia, for instance, often find it easier to read material when it’s displayed in a typeface called Open Dyslexic . Computers, tablets and digital reading devices, such as Amazon’s Kindle, can offer this option. Many e-readers have apps that can be used on tablets, too. That makes it possible to get these advantages on a tablet or phone.

Reading online also allows editors to insert hyperlinks. These may help a reader dive deeper to understand a particular point or even just to learn the definition of a term that may be new or confusing.

Michelle Luhtala is a school librarian in New Canaan, Conn. She helps her school make the best use of digital material. She also trains teachers. Luhtala is not alarmed about digital reading. She points out that there are many ways to read on screens. Some e-textbooks and databases used in schools come with tools that make it easier, not harder, to learn, she says. Some e-books, for instance, let you highlight a passage. Then the computer will read it out loud. Other tools allow you to make notes about passages you’re reading and keep those notes after you’ve returned a book to the library. Most of these texts have pop-up definitions. Some link to maps, keywords and quizzes. Such tools can make digital material extremely useful, she argues.

Getting the most out of your digital reading

All experts agree on one thing: There’s no going back. Digital reading is here to stay. So it pays to make the most of it.

One obvious trick: Print anything that needs careful reading. You have this option when reading Science News for Students . (There’s a print icon at the top of every article.) But that may not be necessary. Other things can also make sure you retain the most from what you read on screens.

The most important thing, says Baron at American University, is to slow down. Again, this is about mindset. When you read something important, slow down and pay attention. “You can concentrate when you read digitally,” she says. But you have to make an effort. She suggests saying to yourself, “I’m going to take half an hour and just read. No text messages. No Instagram updates.” Turn off notifications on your phone or tablet. Only turn them back on when you’re done reading.

It’s also a good idea to do a little prep. Baron compares reading to sports or to playing music. “Watch a pianist or an athlete. Before they run the race or play the concerto, they get themselves in the zone,” she says. “It’s the same thing for reading. Before you read something you really want to focus on, get in the zone. Think about what you’ll be reading, and what you want to get from it.”

To really get the most from reading, Baron says, you have to engage with the words on the page. One great technique for this is making notes. You can write summaries of what you’ve read. You can make lists of key words. But one of the most useful ways to engage with what you’re reading is to ask questions. Argue with the author. If something doesn’t make sense, write down your question. You can look up the answer later. If you disagree, write down why. Make a good case for your point of view.

If you’re reading a print book, you can take notes on paper. If it’s a printout or if you own the book, you can write directly on the page. You can do this when you’re reading on your phone or tablet, too. Just keep a pad of paper handy while you read. Many apps also allow you to make virtual notes directly on a digital document, Luhtala points out. Some allow you to add virtual stickies. With some you can even write in the margins and turn down the corners of the virtual pages.

Like most things, what you get from reading on-screen depends on what you put into it. You don’t have to make a choice between print or digital. Alexander points out that when it comes to print versus digital, one is not better than the other. Both have their place. But they are different. So keep in mind that to learn well, how you interact with them may have to differ, too.

More Stories from Science News Explores on Tech

How to design artificial intelligence that acts nice — and only nice

‘Jailbreaks’ bring out the evil side of chatbots

A new tool could guard against deepfake voice scams

AI learned how to influence humans by watching a video game

Scientists Say: Bionic

Could we build a mecha?

Artificial intelligence helped design a new type of battery

Analyze This: Marsupial gliders may avoid the ground to dodge predators

You can Choose category

The Difference Between Online Reading and Offline Reading

Introduction, the new literacies of online research and comprehension, developing students’ online reading comprehension, tpack framework, the use of tpac in planning lessons, my skill level in the tpac method.

With the integration of technology in education, there is a shift from offline reading to online reading. Based on the definition, offline reading occurs through printed texts, while online reading happens through screens and electronic texts, especially web-based reading materials (Dwyer, 2016). Unlike offline reading, where text is bound within the covers of a book, an online reader has the mandate of assembling potential text for reading. As a result, reading online requires the readers to deepen their skills to navigate, locate and synthesize the information presented through various websites. In addition, online readers must have computer skills to navigate through the internet and obtain the required texts (Dwyer, 2016). Therefore, contrary to offline reading, online reading depends entirely on information technology.

Compared with online reading, offline reading is better for focus and memory retention. Offline reading is free from distractions from online ads that may take the reader’s attention. It offers more fixity and solidity to the reader’s sense of the progress of the text (Dwyer, 2016). This is an indication that the reader has the ability to concentrate when reading. However, online reading exposes an individual to several distractions. A digital text reader can easily shift from reading to other web pages such as Facebook, YouTube, and others. With this distraction, it is challenging for an online reader to focus on the text. As a result, students have more focus when reading printed texts than when reading digital texts.

Teachers play an integral role in developing online reading comprehension and internet research skills. To achieve this, a teacher can use socially mediated experiences where they directly interact with students. This will assist a teacher in creating a positive relationship with learners. The second approach to teaching the concept is using an internet workshop (Zhang et al., 2011). The model is important because it introduces students to internet sites and develops crucial background knowledge. It involves activities such as locating a site, creating tasks requiring the students to use the site, assigning the tasks, and conducting a workshop. The third approach that a teacher can use is internet inquiry. In this case, students examine the information and prepare a report. Therefore, teachers should use models such as socially mediated, internet workshop, and internet inquiry to equip the students with online reading comprehension skills.

TPACK is an acronym for technological pedagogical content and knowledge. The framework provides a new model for integrating technology into education and how to offer the best educational experience for students. In addition, it was designed to illustrate a set of knowledge that educators need to teach their learners, teach efficiently and use technology (Koehler et al., 2013). The TPACK framework strives to enhance this study and scholarly heritage by incorporating technology into the types of knowledge that teachers must examine when teaching. The framework plays an important role in facilitating effective teaching. For example, with the advancement in technology, an educator is supposed to integrate technological concepts when teaching students (Koehler et al., 2013). As a result, the framework aims to aid in the development of improved tools for identifying and documenting how technology-related professional knowledge is implemented and instantiated in practice.

The three cores of TPACK are content, pedagogy, and technology. Content knowledge refers to the teacher’s knowledge of the subject matter. For example, this knowledge includes scientific facts, theories, and evidence-based reasoning. Pedagogy knowledge is an educator’s deep knowledge of the operations of teaching and learning (Koehler et al., 2013). For instance, it includes designing engaging classroom environments that allow maximum student activity and self-regulation. Technological knowledge is the educators’ knowledge of or ability to use different technical tools. For example, a teacher’s ability to use the internet or smart boards as tools for learning. Therefore, the main components of the model are content, pedagogy, and technological knowledge.

TPAC plays an integral role in developing a lesson plan because it provides the main aspects that should be included in the plan. The three primary components of the model; content, pedagogy, and technology, help design a teaching plan (Koehler et al., 2013). Firstly, an educator must create content that meets learners’ needs. The content is the core of the lesson plan because it shows the concepts that it explores. Secondly, the plan should incorporate the pedagogical knowledge of teaching (Koehler et al., 2013). For example, some of the methods used for new concepts are experiential and inquiry-based learning. Experiential learning allows a learner to explore and practice. Thirdly, the lesson plan should integrate technology, especially in the contemporary environment. For instance, an educator can consider using google meet and other technologies to conduct online learning.

My skill level in the TPAC model has increased tremendously after reading the texts. I discovered that TPAC is an important part of the education system because it incorporates the growing demand for technology, a good understanding of teaching practices, and the creation of effective content (Koehler et al., 2013). It forms the efficiency in the delivery of the lesson plan with the integration of technology. It is an application in all aspects of learning, which are integral in teaching and learning. I now understand that TPAC is a model that assists educators to contemplate on their learning domains interconnect to effectively teach and engage learners with technology (Koehler et al., 2013). It offers educators an opportunity to develop professional development and competency. For example, there is a need for educators to integrate technology into teaching. Therefore, I now have the ability to incorporate the TPAC model into learning.

I have strengths and weaknesses in using the TPAC model in teaching and learning. Based on my strength, I can apply the three components of the framework in developing an effective lesson plan. It allows teachers to analyze and reflect on their practices and how technology is integrated into the class. In addition, through the model, I now understand the intersection between content, pedagogy, and technology. It promotes contemporary learning as I recognize the importance of technology in teaching and learning. In terms of weaknesses, I feel that the meaning of various knowledge domains is inadequate. I believe that more can be done to describe the domains effectively. The model has strengths and weaknesses that should be considered during application.

To increase my command of the TPAC model, I will focus on increasing my knowledge. Firstly, I collect reliable and peer-reviewed sources that address the model from various sources. Then, I will read and analyze the contents and identify shortcomings. Secondly, I will conduct research to address the problems identified and questions derived from the reading. Based on this, I will be able to improve my understanding of the TPAC model.

Dwyer, B. (2016). Engaging all students in internet research and inquiry. The Reading Teacher , 69 (4), 383-389.

Koehler, M. J., Mishra, P., & Cain, W. (2013). What is technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK)? Journal of education , 193 (3), 13-19.

Zhang, S., Duke, N. K., & Jiménez, L. M. (2011). The WWWDOT approach to improving students’ critical evaluation of websites. The Reading Teacher , 65 (2), 150-158.

- Submit A Post

- EdTech Trainers and Consultants

- Your Campus EdTech

- Your EdTech Product

- Your Feedback

- Your Love for Us

- EdTech Product Reviews

ETR Resources

- Mission/Vision

- Testimonials

- Our Clients

- Press Release

Online vs Offline Reading

Language development starts with the ‘LSRW’ skill development.

Reading, though is third in the row plays a vital role in learning. It is not only required to concentrate on vocabulary development in languages but also for developing creative thinking. Reading closes windows and opens doors of wisdom. This activity is considered the base of revolutions around the world. Ideas formed and expressed while writing, when transforms, influences other minds to become ‘ enlightened ’.

Reading took a new dimension during industrial revolution with the advent of ‘ printed books ’. This was an activity which when cultivated among the intellects, changed the face of the world. Today, reading has become more than a medium of expression. Globalization has changed the very outlook of this skill as – knowledge, applicable and building a digitally aware citizen. Reading is more online rather than offline. Era of sending letters and postcards has changed to exchanging emails and online greeting cards. Chat rooms, forum discussions, blogs are sources where people can upload and connect with the like-minded.

In this fast changing scenario, what change has happened in the field of Reading?

Online Reading has taken prominence, let’s take a quick look at the differences between online and offline reading.

Offline reading means carry the book on move. It becomes difficult as it is both bulky and time consuming. A book often does not give meanings of basal words for which it is not recommended. Example: A book of chemistry, may carry the word ‘statistically’ but no emphasize of what statistics means would be provided. The reader needs a dictionary to look up into the meaning and apply to the context, which is again time consuming. Offline reading is directional and may have only one topic to move forward. References provided need another book or article to be read to understand the base of the material.

Online reading can be called as multidimensional. Words and phrases which are difficult can be searched either through hyperlinks provided by the author or in the very next tab opened besides the reading article. Online reading is becoming more operative due to the very ease of carrying. Space and storage has shrunk, and a library load of books can be accommodated in a mobile phone or a USB.

The major advantage of online reading is in the availability of multitude of media plugins along the reading material. Articles embedded with podcasts, videos give the reader an experience that helps them reinforce their reading. Online reading facilitates ‘zoom’ option for better visual experience.

All said the reader needs to understand the basic necessities of online reading. The major problem countries are facing are due to cutting down of trees. One of the prime purposes to cut down trees is to make paper. Use of e-paper will help us build a sustainable future. Schools have already started their focus in this direction by giving tablets to their students rather than text books. Students can use mobile apps of text books which help them visualise the content of the material and allow them to look into diverse features of the same material. Understanding the very fact that opening the internet needs to done ‘ with care ’, avoidance may not be the best resolution. ‘ Kindling thought process ’ and ‘ making them aware ’ are the only options available, since we cannot stop the fast moving digital natives.

Latest EdTech News To Your Inbox

Stay connected.

Sign in to your account

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

- Literary Events

- Recommendations

- How To Publish

Online Reading Vs Traditional Reading In Today’s World

Online reading has been growing more popular each year. This trend has sparked a debate between online reading and traditional reading. For anyone who hasn’t picked a side yet, we are going to help you make your mind!

What is Online Reading?

Online reading is when you take information or text from a digital format. It is also called digital reading. PDF files, EBooks, audiobooks, blogs, etc. are all considered to be online reading, whether it’s through a PC or a phone. There are many advantages of online reading which include:

Advantages of Online Reading

1. it’s fast paced.

In today’s quick world, online reading makes it easy to look for books. You don’t need to plan a whole trip to the bookstore to stock up on your books. You can simply download your book. Even if you’re busy with work, you can save the book on a click!

2. It is More Versatile

Generally, if you download a book, it would be on your phone. And you take your phone everywhere. It doesn’t get easier than that. You can highlight important lines through the tools available on your laptop or even learn meanings of difficult words through the internet just in one click.

3. Easy To Understand

Sometimes while reading you get stuck on a word or a phrase you don’t really understand. Or sometimes you miss a point and get confused. Online reading provides the readers with hyperlinks which provides ease to the reader and reduces the chances of any confusion.

Disadvantages of Online Reading

Unfortunately nothing in the world comes with only advantages. There are certain disadvantages to online reading which include:

1. Attention is Diverted

While reading a book your eyes and mind are focused on the words and read them in the sequence they’re written. But while reading something online, your eyes keep wandering around the screen and you often skip over parts and details of the book.

2. Needs Power

It doesn’t matter if you read on your PC, phone or kindle, anything electronic will run out of power and you’ll need to charge it which can be annoying at times.

3. Loss of Details

Since you can’t give your full attention to the content on the screen, you’re more likely to loss information and details or wouldn’t be able to understand the ongoing situation in the book.

What Is Traditional Reading?

The process of getting information or text from a print format is called traditional reading . Reading books, magazines, newspapers, dictionaries, etc. is all considered to be traditional reading. Traditional readers find it hard to adap to newer ways of Online Reading. Book collectors and people who regularly visit traditional libraries also stick to their habits of reading printed books.

Advantages of Traditional Reading

1. linear reading.

When you’re reading something that is in your hand, it grasps your full attention and you read it in the sequence that it’s written. This gives you a better understanding of the book.

2. Does Not Need Power

You don’t need any power or charging for print formats. So if you’re reading the plot twist of the book and are gripped with suspense, you won’t have to worry about the battery dying.

3. Satisfaction

The satisfying feeling of buying your book, holding it, reading it, understanding it, sympathizing with the characters, going through the suspense and then finally finishing it can never be digitalized.

Disadvantages of Traditional Reading

1. time consuming.

Reading something physically requires at least a few hours to finish and sadly you can’t really multitask while reading either. It requires your full attention and time which is hard to give in today’s fast world.

2. Less Versatile

Books come in all sizes but mostly they aren’t small enough to carry around in a pocket. Carrying huge volumes of books can cause an inconvenience.

3. Take Up Space

Books usually take up a lot of space and can get damages if kept in an unfavourable environment.

Research shows that kids prefer reading online as it gives them more privacy. It also allows them to access more material online, reading in the dark and multitask.

But on the other hand, it has also impacted their patience. Children are getting more and more impatient. Online Reading has also decreased their attention span, since there are more distractions online than in reality. Online Reading has increased the number of eyestrains being caused by digital devices. Also, rather than reading from beginning to end, online readers increase their ability to skim through the pages and just search for keywords and phrases.

Traditional reading on the other hand encourages readers to do a more in-depth analysis. Research shows that since reading online makes us want to avoid long material and read just enough to understand.

So here was a list of advantages and disadvantages of both mediums. To be honest, both of them are already established in our daily lives to an extent. Both of them have certain advantages which the other doesn’t so it’s not an either or question, it more about how can we use both of them to the fullest to get the best out of them!

So head on to meraqissa and choose an eBook or order a printed copy today to vote for the medium you prefer!

- #Onlinereading

- #Publishing

Related Articles

Daastan published authors at pre-book conference at umt ila, leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Top Book Publishers of Pakistan

Top 10 book publishing companies in 2024, stay in touch, follow our instagram.

- Publish Books

- Miscellaneous

Want to study better? Don’t ditch your books for online study materials

During the pandemic, many college professors abandoned assignments from printed textbooks and turned instead to digital texts or multimedia coursework.

As a professor of linguistics , I have been studying how electronic communication compares to traditional print when it comes to learning. Is comprehension the same whether a person reads a text onscreen or on paper? And are listening and viewing content as effective as reading the written word when covering the same material?

The answers to both questions are often “no,” as I discuss in my book “ How We Read Now ,” released in March 2021. The reasons relate to a variety of factors, including diminished concentration, an entertainment mindset and a tendency to multitask while consuming digital content.

Studies have shown that students do more mind-wandering when listening to audio than when reading. Source: Cindy Ord/Getty Images/AFP

Print versus digital reading

When reading texts of several hundred words or more, learning is generally more successful when it’s on paper than onscreen. A cascade of research confirms this finding.

The benefits of print particularly shine through when experimenters move from posing simple tasks – like identifying the main idea in a reading passage – to ones that require mental abstraction – such as drawing inferences from a text. Print reading also improves the likelihood of recalling details – like “What was the colour of the actor’s hair?” – and remembering where in a story events occurred – “Did the accident happen before or after the political coup?”

Studies show that both grade school students and college students assume they’ll get higher scores on a comprehension test if they have done the reading digitally. And yet, they actually score higher when they have read the material in print before being tested.

Educators need to be aware that the method used for standardised testing can affect results. Studies of Norwegian tenth graders and US third through eighth graders report higher scores when standardised tests were administered using paper. In the US study, the negative effects of digital testing were strongest among students with low reading achievement scores, English language learners and special education students.

My own research and that of colleagues approached the question differently. Rather than having students read and take a test, we asked how they perceived their overall learning when they used print or digital reading materials. Both high school and college students overwhelmingly judged reading on paper as better for concentration, learning and remembering than reading digitally.

The discrepancies between print and digital results are partly related to paper’s physical properties. With paper, there is a literal laying on of hands, along with the visual geography of distinct pages. People often link their memory of what they’ve read to how far into the book it was or where it was on the page.

But equally important is mental perspective, and what reading researchers call a “ shallowing hypothesis .” According to this theory, people approach digital texts with a mindset suited to casual social media, and devote less mental effort than when they are reading print.

Podcasts and online video

Given the increased use of flipped classrooms – where students listen to or view lecture content before coming to class – along with more publicly available podcasts and online video content, many school assignments that previously entailed reading have been replaced with listening or viewing. These substitutions have accelerated during the pandemic and moved to virtual learning.

Surveying US and Norwegian university faculty in 2019, University of Stavanger Professor Anne Mangen and I found that 32% of US faculty were now replacing texts with video materials, and 15% reported doing so with audio. The numbers were somewhat lower in Norway. But in both countries, 40% of respondents who had changed their course requirements over the past five to 10 years reported assigning less reading today.

A primary reason for the shift to audio and video is students refusing to do assigned reading. While the problem is hardly new , a 2015 study of more than 18,000 college seniors found only 21% usually completed all their assigned course reading.

Audio and video can feel more engaging than text, and so faculty increasingly resort to these technologies – say, assigning a TED talk instead of an article by the same person.

Maximising mental focus

Psychologists have demonstrated that when adults read news stories or transcripts of fiction , they remember more of the content than if they listen to identical pieces.

Researchers found similar results with university students reading an article versus listening to a podcast of the text. A related study confirms that students do more mind-wandering when listening to audio than when reading.

Results with younger students are similar, but with a twist. A study in Cyprus concluded that the relationship between listening and reading skills flips as children become more fluent readers. While second graders had better comprehension with listening, eighth graders showed better comprehension when reading.

Research on learning from video versus text echoes what we see with audio. For example, researchers in Spain found that fourth through sixth graders who read texts showed far more mental integration of the material than those watching videos. The authors suspect that students “read” the videos more superficially because they associate video with entertainment, not learning.

The collective research shows that digital media have common features and user practices that can constrain learning. These include diminished concentration, an entertainment mindset, a propensity to multitask, lack of a fixed physical reference point, reduced use of annotation and less frequent reviewing of what has been read, heard or viewed.

Digital texts, audio and video all have educational roles, especially when providing resources not available in print. However, for maximising learning where mental focus and reflection are called for, educators – and parents – shouldn’t assume all media are the same, even when they contain identical words.

Naomi S. Baron , Professor of Linguistics Emerita, American University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .

Popular stories

The most prestigious canadian universities in 2024, you’re doing resumes the hard way: 10 best resume-maker apps that are free, fast and easy to use, no coding skills, no problem: these high-paying jobs in ai welcome everyone, the most affordable canadian universities in 2024 that won’t break the bank, can bionic reading make you a speed reader not so fast, why are certain genres of music more effective in helping you study than others, important lessons from 'atomic habits' students can draw from.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Online and Offline Reading Comprehension

Modern perspectives on the innovation of teaching pedagogies, language assessments, theories and practice were introduced. However, limited attention was given to ESL users' modality of reading comprehension and preference. This empirical study explores the difference between Online and Offline Reading Comprehension of Filipino Grade Eleven students based on their raw scores. The study sought to answer the question: Is there a significant difference between Online and Offline Reading Comprehension of participants? Mixed methods were employed to strengthen the validity and reliability of the study. Statistical analysis was initially conducted followed by observation and focus group discussion. New Literacies and online-based language assessments are primary concerns that opens for further researches.

Related Papers

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature

Chingyi Tien

English Language Teaching

Abdul Rashid Mohamed

The purpose of the study is to have a relook at the ESL reading comprehension assessment system for Malaysian Year Five students. Traditionally, the ESL teachers have been assessing and reporting on their primary year’s students by merely giving a composite grade with some vague remarks. This process has been used and is still being employed in spite of the numerous advances and progress that have been made in the realm of education. To gauge the students’ reading ability there is a need to take a serious look into the way teachers assess the students. In this ESL reading comprehension assessment system, a set of standardised generic reading comprehension test, a reading matrix and reading performance descriptors were developed. The findings revealed that Year Five respondents at reading performance Band 1, Band 2, Band 3, Band 4 and Band 5 have acquired the literal, reorganization and inferential reading sub-skills to a certain extent. The results obtained were found to be consiste...

This study was conducted to systematically track and benchmark upper primary school students " ESL reading comprehension ability and subsequently generate data at the micro and macro levels according to individual achievement, school location, gender and ethnicity at the school, district, state and national levels. The main intention of this initiative was to provide information to assist ESL teachers about their students " reading ability and to determine students' reading comprehension performance standards. The auto generated data is expected to facilitate classroom instructional process without necessitating teachers to prepare test materials or manage data of their students " reading comprehension track records. The respondents were 1,514 Year 5 students from urban and rural schools from a district in northern Malaysia. The idea was conceptualised through a series of tests and development of the Reading Evaluation and Decoding System (READS) for Primary Schools. The findings indicated that majority of the respondents were " below standard " and " at academic warning ". We believe the generated data can assist the Ministry of Education to develop better quality instructional processes that are evidence based with a more focused reading instruction and reading material to tailor to the needs of students.

Fabio Arismendi

Few studies in Colombia have explored and compared students’ reading comprehension processes in EFL, in different modalities of instruction. This article reports on some findings of a larger study in which two groups of graduate Law students took a reading comprehension course in English, delivered in two different modalities of instruction: face-to-face and web-based. Both courses were served by an English teacher from the School of Languages at Universidad de Antioquia. The data gathered from class observations, in-depth interviews, questionnaires, tests, the teacher’s journal and data records in the platform provided insights about the students’ use of reading and language learning strategies in both modalities. Findings suggest that students applied the reading strategies explicitly taught during the courses and some language learning strategies for which they did not receive any instruction.

International Journal of Social Science Research

Andang Suhendi

Reading is an important language skill for second-language learners. Effective reading is essential for undergraduates to understand academic texts and become critical thinkers in identifying and evaluating opinions and arguments. This study examines students' achievement in reading tests conducted in three different modes: physical face-to-face, online and blended learning platforms. The selection of respondents was made using purposive sampling. The data for this study consist of secondary data obtained from 392 participants from three different faculties in a local university. The data were analyzed using the SPSS version 20 tool. The results indicate significant differences in teaching and learning modes and students' achievement in reading tests. The findings show that physical face-to-face mode produced the highest test scores, while blended learning produced the lowest test scores. Next, the findings also showed that girls performed better in reading tests than boys. ...

Hamid Mojarrad

Julie Coiro

This mixed-method study investigated the extent to which new reading comprehension proficiencies may be required on the Internet. It also explored the nature of online reading comprehension among adolescent readers who read online at different levels of proficiency. Results of a hierarchical regression analysis of data from a stratified random sample of 109 seventh graders indicated performance on one measure of online reading comprehension ability accounted for a significant amount of the variance in performance on a second measure of online reading comprehension ability over and above offline reading comprehension ability and a measure of topic-specific prior knowledge. Further, a developmental, contrastive case study analysis of retrospective think-aloud protocol data obtained from three purposefully selected focal students revealed a developmental progression of online reading skills and strategies that appeared to distinguish three diverse readers’ performance within six observed phases of online reading comprehension.

UAD TEFL International Conference

Indah Fajar

This study focused on reading comprehension ability of the English Department students in answering READS, MCQ questions. READS is an alternative standardized assessment system that is capable of measuring reading comprehension ability. This is a descriptive study based on Barrett's Taxonomy levels, such as literal comprehension, reorganization, and inferential comprehension. This study consisted of 122 students of the English Department academic year 2015 through 2018 at one of the private universities in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. This study analysis utilized the three Barrett's taxonomy scales to identify whether the students were at meet the standard, below standard, above standard or at academic warning. Finding of the research indicated that 27.8 % students categorized into academic warning (Band 2 and 3), 46.7% students categorized into below standard (Band 4) and 25.5% students categorized into meet standard (Band 5). Consequently, READS as an alternative assessment will...

The 6th International Conference on Multidisciplinary Research (ICMR) 2023

Septhia Irnanda

This study aims to identify both linguistic and non-linguistic reading comprehension problems during online learning. This qualitative study used a descriptive design focusing on 18 of the fifth and seventh semester students from the English Education Department in the Teacher Training and Education Faculty in Serambi Mekah University. The instrument used in this study was a questionnaire. The data was analyzed by using qualitative analysis to explore the students' reading comprehension difficulties during online learning. The results indicated that the students experienced the most reading problems in the areas of facilities (69.46%). This means the participants considered it as the most frequent problems that interfered with their reading comprehension during online learning

Psychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary Journal

Psychology and Education , Shara Jeane D. Niala

The purpose of this study was to find out whether Project e-Localized (eBooks and Printed localized reading materials) will enhance the level of reading comprehension in Filipino among Grade 3 pupils section Masunurin of Villa Perez Elementary School. This study utilized the quantitative method of research using a quasiexperimental design. The researcher statistically analyzed the pre-test and a post-test result to determine the significant difference in the level of reading comprehension in Filipino before and after the utilization of the Project e-Localized. Purposive sampling was used by the researcher composing of thirty-eight (38) Grade 3 pupils as the respondents. The statistical tools used were Mean Percentage Score and T-test. The study showed that after implementing Project e-Localized, the pretest MPS 57.37% with the descriptive analysis of "good" increased from the posttest resulted to 84.61%, with the descriptive analysis of "excellent" given the difference of 27.24 % and the value of the t-test is 22.9236 which is greater than t-Critical value of 2.0262, with 37 degrees of freedom at 0.05 level of significance. It is evident that there is a significant difference; therefore, the null hypothesis is rejected. Thus, the utilization of Project e-Localized wherein the researcher used electronic books and printed localized materials greatly enhanced the level of comprehension in Filipino of Grade Three pupils. Teachers must keep in mind that enhancing reading comprehension takes time and effort. It is educators' duties and responsibilities to enhance the level of comprehension of every pupil.

RELATED PAPERS

Gerardo Dominguez

Thierry Van Hees

Dr. Bhupendra Prajapati

Marcello Sarini

Forestry in the Midst of Global Changes

Adrina C . Bardekjian

Plant Physiology

S. Somerville

Mongolian Journal of Agricultural Sciences

Davaasuren Nergui

Revista médica de Chile

Alejandro de Marinis

Shyam Singh

dimas doyie

Michael Smart

Metabolites

Rosa Perestrelo

Nature Biotechnology

NAIMUL ISLAM

SQUALEN, Bulletin of Marine and Fisheries Postharvest and Biotechnology

Gemilang Rahmadara

Ensayos sobre Política Económica

Rolando Martinez

International Journal of Hyperthermia

ananda kumar

Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología

Francesc Formiga

Journal of Surgical Technique and Case Report

NASIRU ISMAIL

Springer eBooks

Corinne Young

Behavioral and Neural Biology

Lawrence Wichlinski

UCLA文凭证书 加州大学洛杉矶分校文凭证书 klhjkgh

Jurnal Komunikasi

Urip Tri Wijayanti

Applied Surface Science

Cristián Mauricio Covarrubias

The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry

Antoine Bret

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Psicol Reflex Crit

- v.35; 2022 Dec

Reading digital- versus print-easy texts: a study with university students who prefer digital sources

Noemí bresó-grancha.

1 Escuela de Doctorado, Universidad Católica de Valencia San Vicente Mártir, San Agustín 3, Esc. A, Entresuelo 1, 46002 València, Spain

María José Jorques-Infante

2 MEB lab, Faculty of Psychology|, Universidad Católica de Valencia San Vicente Mártir, Avenida de la Ilustración, 4, Burjassot, Valencia, 46100 Spain

Carmen Moret-Tatay

3 Dipartimento di Neuroscienze Salute Mentale e Organi di Senso (NESMOS), La Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

The transition from on-paper to on-screen reading seems to make it necessary to raise some considerations, as a greater attentional effort has been claimed for print texts than digital ones. Not surprisingly, most university students prefer this digital medium. This research aims to examine reading times by contextualizing this phenomenon into two processes: namely, word recognition and reading comprehension task on paper and on screen. Thus, two different tasks—counterbalanced into digital and print mediums—were carried out per each participant with a preference for a digital medium: a reading comprehension task (RCT) and a lexical decision task (LDT) after reading a specific story. Participants were slower reading print texts and no statistically significant differences were found in RCT accuracy. This result suggests that the task required more cognitive resources under the print medium for those with a worse comprehension performance in reading, and a more conservative pattern in digital RCT for those with a better performance.

Introduction

Reading has different effects on the brain, is considered as an activity that can reduce stress (Corazon et al., 2010 ), improves people’s memories (Peng et al., 2018 ), and enhances empathic skills (Gabay, Dundas, Plaut, & Behrmann, 2017 ; Kuzmičová, Mangen, Støle, & Begnum, 2017 ; Mangen, 2016 ), among others. This process has also been linked to longer life spans (Chang, Wu, & Hsiung, 2020 ; Peng et al., 2018 ), but, surprisingly for most, it is not innate. It must be learned through specific exercises for this purpose, usually in our childhood. In this way, networks of connections are developed through an architecture which is already used for recognizing visual patterns and understanding spoken language (Vogel et al., 2013 ). This architecture has been mainly addressed by studying response times (RTs) (Luce, 1986 ) and the specificity of reading-related regions through fMRI (Vogel et al., 2013 ).

When describing the reading process, an abstraction is developed in the fusiform gyrus that allows our brain to recognize strings of letters in milliseconds. This occurs even if stimuli are presented in different typographies, sizes, or even upper or lower cases, among others (Perea, Moret-Tatay, & Panadero, 2011 ). The changing nature and circumstances of reading, as digitization is growing, is a subject of debate that might influence our reading process. Literature has suggested a greater attentional effort for print texts than for digital texts (Mangen & Kuiken, 2014 ). While some studies stipulate higher reading comprehension on paper (Kim & Kim, 2013 ; Mangen, Walgermo, & Brønnick, 2013 ), others find no such differences between mediums (Porion, Aparicio, Megalakaki, Robert, & Baccino, 2016 ; Rockinson- Szapkiw, Courduff, Carter, & Bennett, 2013 ). These differences on results might be explained through the effect of modulating variables (Delgado, Vargas, Ackerman, & Salmerón, 2018 ) such as time constraints, genre or type of text, and temporal moment. Moreover, a piece of research (Mangen, Olivier, & Velay, 2019 ) stands out by assessing this variable in Kindle DX, as a digital medium, and print. Participants were assessed in their reconstruction of the story from both mediums. The authors concluded that kinesthetic feedback was less informative in a Kindle. Another study comparing print, e-reader, and a tablet computer by combining EEG and eye-tracking measures showed shorter mean fixation durations and lower EEG theta band voltage density in the digital medium for older participants (Kretzschmar et al., 2013 ). However, comprehension accuracy did not differ between mediums.

Comparisons in this front have also been addressed from fields such as ergonomics and perception (Benedetto, Drai-Zerbib, Pedrotti, Tissier, & Baccino, 2013 , 2014 ). It should be noted that the physical interaction that occurs while reading on paper or on screen is significantly different. Actions like turning a page or feeling the paper of a book produce a multisensory experience that increases the cognitive, affective, and emotional insertion in the subject matter (Jacobs, 2015 ; Kuzmičová et al., 2017 ; Mangen et al., 2019 ). In this context, a shallowing hypothesis is theorized, which tries to explain how recent media technologies might lead to a decline in reflective thought and an increase in superficial learning, as an immediate reward is expected (Annisette & Lafreniere, 2017 ). Given this change in pattern, could decoding be different from one medium to the other, being more superficial in digital, and thus affecting comprehension?

Classical authors such as Eldredge ( 1988 ) claimed that repeated exposure to frequently words in print mediums is likely to improve learners’ visual recognition of those words, which in turn is also likely to improve reading comprehension. Not surprisingly, this is an accepted strategy in fluency interventions (Brown et al., 2018 ). One of the main classical models on text comprehension defines this process as the result of the interaction of text features and readers' knowledge, involving variables such as propositional representation and readers' prior knowledge (Hsu, Clariana, Schloss, & Li, 2019 ; McNamara & Kintsch, 1996 ). In this way, familiarity with the medium is a variable of interest, and differences can be stipulated between samples that are more familiar with the digital versus print environment. On the other hand, considering the simple view of reading (Hoover & Gough, 1990 ) as one of the most influential approaches which has been developed to address early reading comprehension, reading must be addressed from a cognitive perspective. More precisely, this cognitive model of reading comprehension (RC) stipulates that RC is a consequence of the interaction between decoding and linguistic comprehension, where word recognition can be considered part of the decoding process (de Oliveira, da Silva, Dias, Seabra, & Macedo, 2014 ; Kirby & Savage, 2008 ).

According to the literature, the most commonly employed cognitive tasks involved in printed word identification have been lexical decision (LDT) and naming (Imbir et al., 2020 ; Katz et al., 2012 ; Navarro-Pardo, Navarro-Prados, Gamermann, & Moret-Tatay, 2013 ), bearing in mind that in both tasks RTs and accuracy are the main dependent variables. Moreover, one of the dependent variables that RC and lexical decision tasks have in common is the analysis of reaction time or response latency. Within this field, processing speed has been described as an indicator of reading performance in groups such as participants with dyslexia (Norton & Wolf, 2012 ), and is considered a reflection of brain architecture (Luce, 1986 ; Moret-Tatay, Gamermann, Navarro-Pardo, de Córdoba, & Castellá, 2018 ). Some studies seem to indicate that readers in digital media spend less time than in printed texts; however, their understanding may also be affected (Ackerman & Lauterman, 2012 ). Therefore, the literature has stipulated that readers may overestimate their understanding of digital texts.

According to the literature, a decline of long-form reading in higher education is diminishing (Baron & Mangen, 2021 ). In this way, university students seem to prefer, or more frequently used, digital sources than print ones for short times of reading (Terra, 2015 ). Differences between mediums, which were previously described, might be of interest for to be addressed, particularly for short texts. For this reason, this research aims to examine the differences between digital and print easy-texts reading in University students who prefer digital sources. We hypothesize that university students with a preference for digital texts have lower reading latency for simple digital texts than print ones. In addition, we expect, in this profile of participants, shorter lexical decision latencies in digital versus print easy-texts. If comprehension is not compromised in easy texts, previous literature might reflect a cost optimization, which becomes more controversial in long texts, as previous literature has shown. A RC and word recognition across mediums were selected for this research question. Moreover, if word recognition is considered directly linked to RC, it is expected a similar pattern for both processes in terms of speed processing. Lastly, a Bayesian approach was considered as an alternative strategy to support traditional analysis as described in prior literature (Nuzzo, 2014 ; Puga, Krzywinski, & Altman, 2015 ).

Materials and methods