What Is Negative Reinforcement?

Charlotte Nickerson

Research Assistant at Harvard University

Undergraduate at Harvard University

Charlotte Nickerson is a student at Harvard University obsessed with the intersection of mental health, productivity, and design.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

Key Takeaways

- In negative reinforcement, first devised by B. F. Skinner, an undesirable stimulus is removed to increase a behavior.

- If an organism is exposed to an aversive situation, and the termination of that situation is made contingent upon some response, then we say that the organism is being negatively reinforced.

- There are two types of negative reinforcement: escape and avoidance learning. Escape learning occurs when an animal performs a behavior to end an aversive stimulus, while avoidance learning involves performing a behavior to prevent the aversive stimulus.

- Negative reinforcement can be effective, but scholars generally agree that it must be used sparingly and is best for reinforcing short-term behaviors.

How Does It Work?

Negative reinforcement refers to the process of removing an unpleasant stimulus after the desired behavior is displayed in order to increase the likelihood of that behavior being repeated.

Negative reinforcement is a basic principle of Skinner’s operant conditioning , which focuses on how animals and humans learn by observing the consequences of their own actions (Dozier, Foley, Goddard, & Jess, 2019).

Skinner argued that learning is an active process. When humans and animals act on and in their environment, consequences follow these behaviors. If the consequences are pleasant, they repeat the behavior, but if the consequences are unpleasant, they do not repeat the behavior.

The word “negative” in the phrase “negative reinforcement” means simply to “take something away. It is this removal of a stimulus that is intended to strengthen a desirable behavior.

Thus, negative reinforcement is not intended to reinforce negative or undesirable behavior (Dozier, Foley, Goddard, & Jess, 2019).

Negative reinforcement occurs when performing an action stops something unpleasant from happening. For example, in one of Skinner’s experiments, a rat had to press a lever to stop receiving an electric shock.

One example of negative reinforcement that often appears in adult life involves driving. Imagine that someone is driving to work and is running late.

The driver sees that the speed limit is 55 mph but decides to go 65 mph so that they can get to work on time.

Suddenly, they see a police car in their rearview mirror with its lights on. The aversive stimulus (getting pulled over) is now present, and so they slow down to the speed limit.

In this case, the desired behavior (driving the speed limit) has occurred as a result of the aversive stimulus (getting pulled over).

In another scenario, someone could drive through rush hour traffic to get to work.

Their commute could take an hour or more, and it is very stressful. They may decide to leave work early one day so that they can avoid the traffic.

Alternatively, they may decide to take a route that has very little traffic and make it to work in 45 minutes.

That person, after getting the same results later in the week, may start taking this new route everyday. In this case, removing the negative stimulus of bad traffic changes the behavior of the driver (Chen, Zhang, Gong, & Lee, 2019).

Types of Negative Reinforcement

There are two main types of negative reinforcement: escape and avoidance. These differ when the aversive stimulus is removed.

Escape Learning

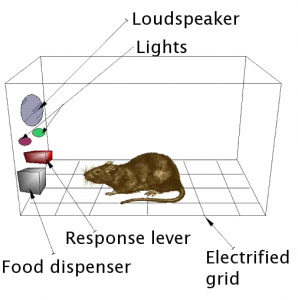

Escape learning occurs when an animal performs a behavior (such as pressing a lever) to stop or avoid an aversive stimulus (such as an electric shock) (Dozier, Foley, Goddard, & Jess, 2019).

For example, a rat in a Skinner box may learn to press a lever to stop the delivery of an electric shock.

Once the animal has learned this behavior, the delivery of shock serves as an aversive stimulus that can be used to reinforce other desired behaviors (such as pressing a different lever).

Avoidance Learning

Avoidance learning occurs when an animal performs a behavior (such as jumping over a hurdle) to avoid or escape an aversive stimulus (such as an electric shock).

For example, a bird in a laboratory experiment may learn to go into a dark compartment to avoid being exposed to a loud noise.

Once the animal has learned this behavior, the loud noise serves as an aversive stimulus that can be used to reinforce other desired behaviors (such as going into dark compartments, even when there is no aversive stimulus present) (Dozier, Foley, Goddard, & Jess, 2019).

How is it different than punishment?

Many people confuse negative reinforcement with punishment in operant conditioning, but they are two very different mechanisms.

Remember that reinforcement, even when it is negative, always increases a behavior. In contrast, punishment always decreases behavior.

Negative reinforcement, on the other hand, removes an unpleasant condition after a desired behavior is displayed to increase the likelihood of that behavior being repeated in the future (Dozier, Foley, Goddard, & Jess, 2019).

Punishment involves bringing an unpleasant consequence after a behavior has already occurred to decrease its likelihood of happening again in the future.

For example, a child may lie about doing his chores, provoking his parents to give him extra chores. In this case, extra chores are an undesirable consequence to eliminate the behavior of lying.

As another example of punishment, a teacher may take away a student’s recess because they were talking too much in class.

This is not negative reinforcement because the teacher is taking away a positive consequence (recess) after the behavior (talking too much in class) has already occurred (Dozier, Foley, Goddard, & Jess, 2019).

All in all, punishment is intended to be an aversive stimulus that decreases the likelihood of a behavior being repeated, while negative reinforcement is intended to remove an aversive stimulus in order to increase the likelihood of a behavior being repeated.

Negative reinforcement is not the opposite of positive reinforcement

Both positive and negative reinforcement increases the likelihood of a behavior being repeated. The only difference is the type of consequence used to achieve this goal.

While positive reinforcement uses a desirable consequence to increase the likelihood of a behavior being repeated, negative reinforcement removes an unpleasant condition after the behavior is displayed in order to increase its future occurrence (Dozier, Foley, Goddard, & Jess, 2019).

For example, imagine a parent trying to potty train their child. Every time they use the toilet, the parent praises them and gives them a sticker.

This is an example of positive reinforcement because the parent is providing a desirable consequence (praise and stickers) after the desired behavior (using the toilet) has occurred to increase its future occurrence.

Now imagine that instead of praising and rewarding your child every time they use the toilet, the parent simply stops nagging them about it.

This is an example of negative reinforcement because you are removing an aversive stimulus (nagging) after the desired behavior (using the toilet) has occurred in order to increase its future occurrence.

In the classroom

Negative reinforcement can be used in any situation where behavior change needs to occur.

One common example of negative reinforcement in the classroom is when a teacher gives students extra credit for turning in their homework on time.

Imagine this is a scenario where students are avoiding turning in their homework on time because they wish to do it more thoroughly in order to avoid a lower grade.

In this case, the extra credit is intended to remove the unpleasant condition (receiving a poor grade) after the desired behavior (turning in homework on time) has occurred in order to increase its future occurrence (Gunter & Coutinho, 1997).

In this example, the extra credit is not given if the student does not turn in their homework on time. This is because negative reinforcement is only intended to work when it follows the desired behavior.

If the extra credit was given regardless of whether or not the homework was turned in on time, then it would simply be a reward and would not function as negative reinforcement.

Another common example of negative reinforcement in the classroom is when a teacher threatens to give students detention if they do not complete their homework.

In this case, the removal of the aversive stimulus (detention) is contingent on the desired behavior (completing homework) being displayed (Gunter & Coutinho, 1997).

Again, it is important to note that negative reinforcement should only be used after the desired behavior has already been displayed.

If students are given detention regardless of whether or not they complete their homework, then it is simply punishment and will not function as negative reinforcement.

Although this negative reinforcement could be effective in encouraging positive behavior, some researchers contend that positive reinforcement should be emphasized and negative reinforcement used sparingly.

They argue that focusing on the positive (e.g., rewarding students for completing their homework) is more likely to result in long-term behavior change than focusing on the negative (e.g., threatening students with detention if they do not complete their homework).

In this view, negative reinforcement is best for immediate behavioral changes (Gunter & Coutinho, 1997).

Effectiveness

Whether or not negative reinforcement is an effective way to change behavior depends on a number of factors, including the age and maturity of the learner, the severity of the aversive stimulus, and the desirability of the desired behavior.

Negative reinforcement can be particularly effective when the aversive stimulus is something that the learner genuinely wants to avoid.

For example, if a student is trying to study for an exam but is easily distracted by social media, using negative reinforcement (e.g., threatening to take away their phone if they do not study) could be an effective way to get them to focus on their work (Dad, Ali, Janjua, Shazad, & Khan, 2010).

However, if the aversive stimulus is not something that the learner cares about, then it is unlikely to be effective.

For example, if a student does not care about detention, then threatening them with detention is not likely to be an effective way to get them to do their homework.

In general, negative reinforcement is most effective when it is used sparingly and only for behaviors that are genuinely undesirable.

Using it too frequently or for minor infractions can result in the learner becoming Ortony, Clore, & Collins (1988) argue that punishment (including negative reinforcement) should only be used “as a last resort” after other methods of behavior change have failed (Dad, Ali, Janjua, Shazad, & Khan, 2010).

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Chen, C., Zhang, K. Z., Gong, X., & Lee, M. (2019). Dual mechanisms of reinforcement reward and habit in driving smartphone addiction: the role of smartphone features. Internet Research .

Dad, H., Ali, R., Janjua, M. Z. Q., Shahzad, S., & Khan, M. S. (2010). Comparison of the frequency and effectiveness of positive and negative reinforcement practices in schools. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 3 (1), 127-136.

Dozier, C. L., Foley, E. A., Goddard, K. S., & Jess, R. L. (2019). Reinforcement. The Encyclopedia of Child and Adolescent Development , 1-10.

Ferster, C. B., & Skinner, B. F. (1957). Schedules of reinforcement . New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Gunter, P. L., & Coutinho, M. J. (1997). Negative reinforcement in classrooms: What we”re beginning to learn. Teacher Education and Special Education, 20 (3), 249-264.

Kohler, W. (1924). The mentality of apes. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis . New York: Appleton-Century.

Skinner, B. F. (1948). Superstition” in the pigeon . Journal of Experimental Psychology, 38 , 168-172.

Skinner, B. F. (1951). How to teach animals . Freeman.

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior . SimonandSchuster.com.

Skinner, B. F. (1963). Operant behavior. American Psychologist, 18 (8), 503.

Thorndike, E. L. (1898). Animal intelligence: An experimental study of the associative processes in animals. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 2(4), i-109.

Watson, J. B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist views it . Psychological Review, 20 , 158–177.

Further Reading

Sprouls, K., Mathur, S. R., & Upreti, G. (2015). Is positive feedback a forgotten classroom practice? Findings and implications for at-risk students. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 59 (3), 153-160.

- Anxiety Disorder

- Bipolar Disorder

- Schizophrenia

- Adjustment Disorder

- Agoraphobia

- Antisocial Personality Disorder

- Borderline Personality Disorder

- Childhood ADHD

- Dissociative Identity Disorder

- Narcissistic Personality Disorder

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder

- Panic Attack

- Postpartum Depression

- Schizoaffective Disorder

- Seasonal Affective Disorder

- Sex Addiction

- Social Anxiety

- Specific Phobias

- Teenage Depression

- Black Mental Health

- Emotional Health

- Sex & Relationships

- Understanding Therapy

- Workplace Mental Health

- My Life with OCD

- Caregivers Chronicles

- Empathy at Work

- Sex, Love & All of the Above

- Parent Central

- Mindful Moment

- Mental Health News

- Live Town Hall: Mental Health in Focus

- Inside Mental Health

- Inside Schizophrenia

- Inside Bipolar

- ADHD Symptoms Quiz

- Anxiety Symptoms Quiz

- Autism Quiz: Family & Friends

- Autism Symptoms Quiz

- Bipolar Disorder Quiz

- Borderline Personality Test

- Childhood ADHD Quiz

- Depression Symptoms Quiz

- Eating Disorder Quiz

- Narcissim Symptoms Test

- OCD Symptoms Quiz

- Psychopathy Test

- PTSD Symptoms Quiz

- Schizophrenia Quiz

- Attachment Style Quiz

- Career Test

- Do I Need Therapy Quiz?

- Domestic Violence Screening Quiz

- Emotional Type Quiz

- Loneliness Quiz

- Parenting Style Quiz

- Personality Test

- Relationship Quiz

- Stress Test

- What's Your Sleep Like?

- Find Support

- Suicide Prevention

- Drugs & Medications

- Find a Therapist

Understanding Negative Reinforcement

Negative reinforcement is a learning method that reinforces desired behaviors instead of punishing unwanted ones.

Humans learn in many different ways.

One of the main ways that we — along with other animal species — learn is through behavior reinforcement. We learn to behave in certain ways to seek a reward or to avoid (uncomfortable) consequences.

A classic example of an award for desired behaviors is a child studying hard for their exam, so they get to go out for an ice cream cone when they get an A+.

Positive reinforcement (rewards) and punishment are both well-known learning and behavior management strategies. But there’s another learning method that you may not have heard of: negative reinforcement.

What is negative reinforcement?

Negative reinforcement is a behavior management strategy that parents and teachers can use with children. It involves taking away something unpleasant in response to a stimulus.

With time, children learn that when they engage in “good” behaviors, then this unpleasant thing or experience goes away.

Both negative and positive reinforcement have been studied since the 1930s as part of a learning method called operant conditioning .

Operant conditioning was first described by a behavior scientist named B.F. Skinner. Skinner ran experiments on rats to see what consequences led the animals to change their behaviors.

Operant conditioning centers around the concept of behavior reinforcement and punishment. By reinforcing desired behaviors (either through negative or positive reinforcement), these behaviors become more likely to reoccur.

And by punishing undesired behaviors, those behaviors start to decrease in an effort to avoid the punishment.

Examples of negative reinforcement

Whether you know it or not, negative reinforcement has probably affected your behavior at some point in your life. For example:

- You take prescribed medication so health symptoms go away.

- You let the car tailgating you pass so they stop honking.

- You get out of bed so your alarm stops ringing.

These are all ways in which negative reinforcement might unknowingly be changing your behavior. You adjust your behavior so that the unpleasant or negative “stimulus” (experience) goes away.

Is negative reinforcement good for kids?

Many educators and behavior therapists are very familiar with the general concept of positive and negative reinforcement. According to a 2019 meta-analysis , it can effectively manage children’s behavior.

Let’s look at some examples of how negative reinforcement could work with kids.

Imagine a child who doesn’t want to do his homework. Their parent scolds and nags them about it, which the child finds unpleasant.

When the child does their homework (the desired behavior), the parent stops nagging. The unpleasant experience goes away. The child learns that the unpleasant experience will go away if they do their homework.

Here are some other examples of negative reinforcement with children:

- You take away your child’s chores for the weekend because they kept their room clean all week.

- You remove your child’s grounding period because they worked on their homework.

- Your child’s sibling stops crying loudly when they stop arguing with them.

When used well, negative reinforcement can be an excellent tool for behavior management. But when used incorrectly, it could unintentionally reinforce misbehavior that you don’t want your child to repeat.

For example, say your child doesn’t want to eat what you’ve cooked for them. The meal is aversive or unpleasant to them, and they begin to throw a tantrum. Overwhelmed, you take the offending trigger — the food — away.

This is negative reinforcement, but could actually reinforce an unwanted behavior: tantrums.

In this interaction, you removed the food so that you could avoid hearing your child tantrum (your child would become calm).

But your child learns that if they throw a tantrum, then the unpleasant experience (having to eat the food cooked for them) goes away.

Positive vs. negative reinforcement

Another type of operant conditioning is positive reinforcement .

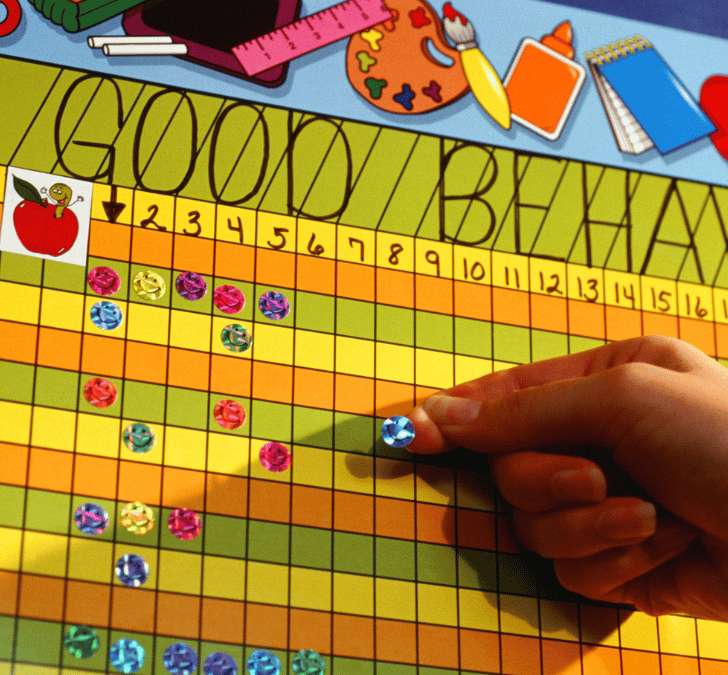

Most parents, and other adults working with children, have heard about positive reinforcement strategies for behavior management. Examples of positive reinforcement are:

- sticker charts

When using positive reinforcement with kids, you give them some type of reward after every time they engage in positive behavior.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) , rewards such as hugs and praise can also increase your child’s self-esteem.

The idea is that this will reinforce this behavior and make it more likely that the child will repeat this behavior in the future.

Positive reinforcement and negative reinforcement have a lot more in common than you might think. They’re both ways to reinforce desired behavior through operant conditioning.

The main difference between them is that a good or pleasant thing (a reward) is added in response to a stimulus (desired behavior) in positive reinforcement.

For negative reinforcement, an unpleasant thing is subtracted in response to the desired behavior.

They both have the same goal: to reinforce desired behavior.

Here are some examples:

Is negative reinforcement the same as punishment?

Some people confuse negative reinforcement with punishment, but these two things are more opposite than similar.

Negative reinforcement has more in common with positive reinforcement than it does with punishment.

The main difference between the two is that punishment is about discouraging unwanted behavior. Both types of reinforcement (both positive and negative) are about reinforcing and encouraging wanted behaviors.

To illustrate the differences between punishment and negative reinforcement, take a look at the following examples.

The differences are sometimes subtle, but they’re important to be aware of.

Important note

Spanking, or any kind of corporal punishment, has been found by 2021 research to raise the risk of problems like mental health disorders, physical health conditions, and defiant behaviors, such as aggression toward others. It’s not an effective parenting strategy.

Let’s recap

Negative reinforcement involves reinforcing desired behaviors instead of punishing unwanted ones.

Negative reinforcement is a type of learning and behavior modification method that can work well when used in the right way and in the right circumstances.

It may unintentionally reinforce undesired behaviors if used incorrectly or without knowledge of underlying behavior modification theory.

Last medically reviewed on October 28, 2022

6 sources collapsed

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How to use rewards. https://www.cdc.gov/parents/essentials/consequences/rewards.html

- Dad H, et al. (2010). Comparison of the frequency and effectiveness of positive and negative reinforcement practices in schools. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1072573.pdf

- Fortier J, et al. (2021). Associations between lifetime spanking/slapping and adolescent physical and mental health and behavioral outcomes. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9014670/

- Leitjen P, et al. (2019). Meta-analyses: Key parenting program components for disruptive child behavior. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0890856718319804

- Lukowiak T, et al. (2010). Punishment strategies: First choice or last resort. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1137137.pdf

- Staddon JER, et al. (2003). Operant conditioning. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1473025/

Read this next

Parenting can feel like an uphill battle at times, but there are ways you can harness patience, even in the most frustrating situations.

Emotional dysregulation can feel overwhelming for kids and caregivers. Here's how to help a dysregulated child regain balance.

Caregivers can cultivate the adaptability and problem-solving skills that are building blocks of resilience.

Positive thinking is an essential practice to improve your overall health and well-being. Discover how to incorporate positive thinking into your…

Dreaming about babies can hold different meanings for everyone. Although theories vary, biological and psychological factors may influence your dreams.

If you're seeking to boost your concentration, practicing mindfulness, chewing gum, and brain games are just a few techniques to try. Learn how they…

Creating a schedule and managing stress are ways to make your days go by faster. Changing your perception of time can also improve your overall…

Experiencing unwanted and difficult memories can be challenging. But learning how to replace negative memories with positive ones may help you cope.

Engaging in brain exercises, like sudoku puzzles and learning new languages, enhances cognitive abilities and improves overall well-being.

There are many reasons why spider dreams may occur, like unresolved feelings or chronic stress. Learning how to interpret your dream may help you cope.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How Negative Reinforcement Works

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Steven Gans, MD is board-certified in psychiatry and is an active supervisor, teacher, and mentor at Massachusetts General Hospital.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/steven-gans-1000-51582b7f23b6462f8713961deb74959f.jpg)

How Does Negative Reinforcment Work?

- Versus Positive Reinforcement

- Versus Punishment

Effectiveness

Negative reinforcement strengthens a response or behavior by stopping, removing, or avoiding a negative outcome or aversive stimulus. B. F. Skinner first described the term in his theory of operant conditioning .

Rather than delivering an aversive stimulus (punishment) or a reward (positive reinforcement), negative reinforcement works by taking away something that the individual finds undesirable. This removal reinforces the behavior that proceeds it, making it more likely that the response will occur again in the future.

This article discusses how negative reinforcement works, how it compares to other behavioral learning methods, and how effective it can be in the learning process.

Negative reinforcement works to strengthen certain behaviors by removing some type of aversive outcome. As a form of reinforcement, it strengthens the behavior that precedes it. In the case of negative reinforcement, it is the action of removing the undesirable outcome or stimulus that serves as the reward for performing the behavior.

Aversive stimuli tend to involve some type of discomfort, either physical or psychological. Behaviors are negatively reinforced when they allow you to escape from aversive stimuli that are already present or allow you to completely avoid the aversive stimuli before they happen.

Deciding to take an antacid before you indulge in a spicy meal is an example of negative reinforcement. You engage in an action in order to avoid a negative result.

One of the best ways to remember negative reinforcement is to think of it as something being subtracted from the situation.

There are two different types of negative reinforcement: example and avoidance learning. Escape learning involves being able to escape an undesirable stimulus, while avoidance learning involves being able to prevent experiencing the aversive stimulus altogether.

Examples of Negative Reinforcement

Looking at some real-world examples can be a great way to get a better idea about what negative reinforcement is and how it works. Consider the following situations:

- Before heading out for a day at the beach, you slather on sunscreen (the behavior) to avoid getting sunburned (removal of the aversive stimulus).

- You decide to clean up your mess in the kitchen (the behavior) to avoid getting into a fight with your roommate (removal of the aversive stimulus).

- On Monday morning, you leave the house early (the behavior) to avoid getting stuck in traffic and being late for work (removal of an aversive stimulus).

- At dinner time, a child pouts and refuses to eat her vegetables for dinner. Her parents quickly take the offending veggies away. Since the behavior (pouting) led to the removal of the aversive stimulus (the veggies), this is an example of negative reinforcement.

Can you identify the negative reinforcer in each of these examples? Sunburn, a fight with your roommate, being late for work, and having to eat vegetables are all negative outcomes that were avoided by performing a specific behavior. By eliminating these undesirable outcomes, preventive behaviors become more likely to occur again in the future.

Negative vs. Positive Reinforcement

Positive reinforcement is a type of reinforcement that involves giving someone the desired reward in response to a behavior. This might involve offering praise, money, or other incentives.

Both positive and negative reinforcement work to increase the likelihood that a behavior will occur again in the future. You can distinguish between the two by noticing whether something is being taken away or added to the situation. If something desirable is being added, then it is positive reinforcement. If something aversive is being taken away, then it is negative reinforcement.

Negative Reinforcement vs. Punishment

One mistake that people often make is confusing negative reinforcement with punishment . Remember, however, that negative reinforcement involves the removal of a negative condition to strengthen a behavior.

Punishment involves either presenting or taking away a stimulus to weaken a behavior.

Consider the following example and determine whether you think it is an example of negative reinforcement or punishment:

Luke is supposed to clean his room every Saturday morning. Last weekend, he went out to play with his friend without cleaning his room. As a result, his father made him spend the rest of the weekend doing other chores like cleaning out the garage, mowing the lawn, and weeding the garden, in addition to cleaning his room.

If you said that this was an example of punishment , then you are correct. Because Luke didn't clean his room, his father punished him by making him do extra chores.

If you are trying to distinguish between negative reinforcement or punishment, consider whether something is being added or taken away from a situation.

If an unwanted outcome is being added or applied as a consequence of a behavior, then it is an example of punishment. If something is being removed in order to avoid or relieve an unwanted outcome, then it is an example of negative reinforcement.

Uses for Negative Reinforcement

Negative reinforcement can be utilized in a variety of ways in many different settings. A few examples include:

Parents can use negative reinforcement to encourage positive behaviors in various ways. For example, a parent might eliminate a chore that their child is supposed to do if they finish all of the other tasks on their list. Another example is giving children more time to play on their tablets if they finish all of their homework first.

One example of negative reinforcement in the classroom is canceling a task that students dislike (such as a pop quiz) if they complete all their assigned work on time.

Psychotherapy

Negative reinforcement is often utilized as a part of addiction treatment and behavioral therapy . People who have been convicted of drug-related offenses, for example, might be able to have their sentences reduced if they participate in drug and alcohol treatment.

In behavioral therapy, negative reinforcement can help strengthen positive behaviors. As people develop skills, they may find that practicing new coping skills eliminates unpleasant outcomes, which can help further reinforce new behaviors.

Negative reinforcement can be an effective way to strengthen the desired behavior. However, it is most effective when reinforcers are presented immediately following a behavior. When a long period elapses between the behavior and the reinforcer, the response is likely to be weaker.

In some cases, behaviors that occur in the intervening time between the initial action and the reinforcer are may also be inadvertently strengthened as well.

Some experts believe that negative reinforcement should be used sparingly in classroom settings, while positive reinforcement should be emphasized.

While negative reinforcement can produce immediate results, it may be best suited for short-term use.

Benefits of Negative Reinforcement

While the name of this type of reinforcement often leads people to think that it is a "negative" type of reinforcement, negative reinforcement can have several benefits that can make it a valuable tool in the learning process. Potential advantages include:

- It can increase desirable behaviors : Because it involves the removal of an undesirable stimulus, it can help strengthen more positive behaviors.

- It can lead to lasting changes : When applied correctly, negative reinforcement can contribute to long-lasting changes in behavior.

- It can work quickly : The removal of an aversive stimulus can lead to relatively quick behavior change.

Potential Pitfalls of Negative Reinforcement

While negative reinforcement can be a helpful learning tool, it can have some potential downsides.

- It can be misinterpreted : When a negative stimulus is removed, usually without explanation, it can sometimes lead to problems with communication. It can potentially create misunderstandings in relationships where people misread the other person's intentions.

- Poor timing can render it ineffective : If the delivery of negative reinforcement is not timed correctly, it can be less effective. A large gap between the behavior and the removal of an aversive stimulus means that people will be less likely to form a connection between the action and the consequences of the action.

A Word From Verywell

Negative reinforcement can have a powerful effect on behavior, but it tends to be most useful when used as a short-term solution. The type of reinforcement used is important, but how quickly and how often the reinforcement is given also plays a major role in the strength of the response. The schedule of reinforcement that is used can have an important impact not only how quickly a behavior is learned, but also on the strength of the response.

Skinner BF. Operant behavior. American Psychologist, 1963;18(8): 503–515. doi:10.1037/h0045185

American Psychological Association. Negative reinforcement .

American Psychological Association. Aversive stimulus .

American Psychological Association. Positive reinforcement .

Sprouls K, Mathur SR, Upreti G. Is positive feedback a forgotten classroom practice? Findings and implications for at-risk students. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth. 2015;59(3), 153-160. doi:10.1080/1045988X.2013.876958

Segers E, Beckers T, Geurts H, Claes L, Danckaerts M, van der Oord S. Working memory and reinforcement schedule jointly determine reinforcement learning in children: Potential implications for behavioral parent training. Front Psychol . 2018;9:394. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00394

Coon, D & Mitterer, JO. Introduction to Psychology: Gateways to Mind and Behavior . Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning; 2010.

Domjan, MP. The Principles of Learning and Behavior: Active Learning Edition . Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning; 2010.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Reinforcement and Punishment

Learning objectives.

- Explain the difference between reinforcement and punishment (including positive and negative reinforcement and positive and negative punishment)

- Define shaping

- Differentiate between primary and secondary reinforcers

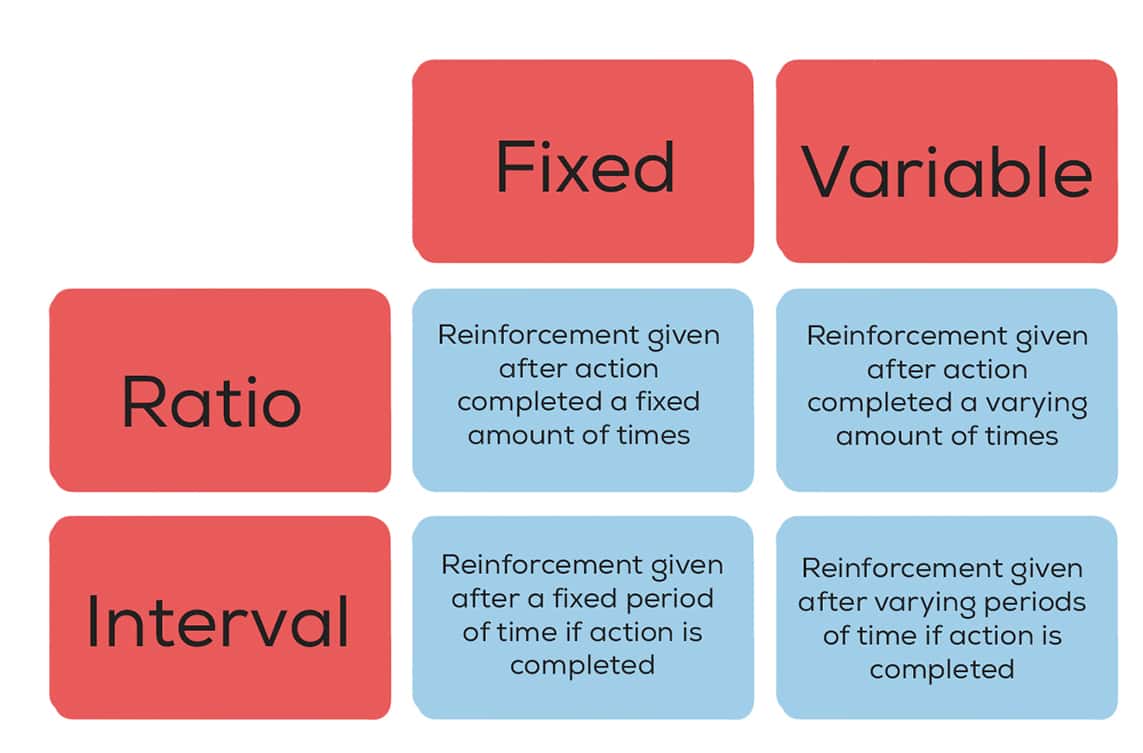

In discussing operant conditioning, we use several everyday words—positive, negative, reinforcement, and punishment—in a specialized manner. In operant conditioning, positive and negative do not mean good and bad. Instead, positive means you are adding something, and negative means you are taking something away. Reinforcement means you are increasing a behavior, and punishment means you are decreasing a behavior. Reinforcement can be positive or negative, and punishment can also be positive or negative. All reinforcers (positive or negative) increase the likelihood of a behavioral response. All punishers (positive or negative) decrease the likelihood of a behavioral response. Now let’s combine these four terms: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment (Table 1).

Reinforcement

The most effective way to teach a person or animal a new behavior is with positive reinforcement. In positive reinforcement , a desirable stimulus is added to increase a behavior.

For example, you tell your five-year-old son, Jerome, that if he cleans his room, he will get a toy. Jerome quickly cleans his room because he wants a new art set. Let’s pause for a moment. Some people might say, “Why should I reward my child for doing what is expected?” But in fact we are constantly and consistently rewarded in our lives. Our paychecks are rewards, as are high grades and acceptance into our preferred school. Being praised for doing a good job and for passing a driver’s test is also a reward. Positive reinforcement as a learning tool is extremely effective. It has been found that one of the most effective ways to increase achievement in school districts with below-average reading scores was to pay the children to read. Specifically, second-grade students in Dallas were paid $2 each time they read a book and passed a short quiz about the book. The result was a significant increase in reading comprehension (Fryer, 2010). What do you think about this program? If Skinner were alive today, he would probably think this was a great idea. He was a strong proponent of using operant conditioning principles to influence students’ behavior at school. In fact, in addition to the Skinner box, he also invented what he called a teaching machine that was designed to reward small steps in learning (Skinner, 1961)—an early forerunner of computer-assisted learning. His teaching machine tested students’ knowledge as they worked through various school subjects. If students answered questions correctly, they received immediate positive reinforcement and could continue; if they answered incorrectly, they did not receive any reinforcement. The idea was that students would spend additional time studying the material to increase their chance of being reinforced the next time (Skinner, 1961).

In negative reinforcement , an undesirable stimulus is removed to increase a behavior. For example, car manufacturers use the principles of negative reinforcement in their seatbelt systems, which go “beep, beep, beep” until you fasten your seatbelt. The annoying sound stops when you exhibit the desired behavior, increasing the likelihood that you will buckle up in the future. Negative reinforcement is also used frequently in horse training. Riders apply pressure—by pulling the reins or squeezing their legs—and then remove the pressure when the horse performs the desired behavior, such as turning or speeding up. The pressure is the negative stimulus that the horse wants to remove.

Link to Learning

Watch this clip from The Big Bang Theory to see Sheldon Cooper explain the commonly confused terms of negative reinforcement and punishment.

Many people confuse negative reinforcement with punishment in operant conditioning, but they are two very different mechanisms. Remember that reinforcement, even when it is negative, always increases a behavior. In contrast, punishment always decreases a behavior. In positive punishment, you add an undesirable stimulus to decrease a behavior. An example of positive punishment is scolding a student to get the student to stop texting in class. In this case, a stimulus (the reprimand) is added in order to decrease the behavior (texting in class). In negative punishment , you remove a pleasant stimulus to decrease a behavior. For example, when a child misbehaves, a parent can take away a favorite toy. In this case, a stimulus (the toy) is removed in order to decrease the behavior.

Punishment, especially when it is immediate, is one way to decrease undesirable behavior. For example, imagine your four year-old son, Brandon, hit his younger brother. You have Brandon write 50 times “I will not hit my brother” (positive punishment). Chances are he won’t repeat this behavior. While strategies like this are common today, in the past children were often subject to physical punishment, such as spanking. It’s important to be aware of some of the drawbacks in using physical punishment on children. First, punishment may teach fear. Brandon may become fearful of the hitting, but he also may become fearful of the person who delivered the punishment—you, his parent. Similarly, children who are punished by teachers may come to fear the teacher and try to avoid school (Gershoff et al., 2010). Consequently, most schools in the United States have banned corporal punishment. Second, punishment may cause children to become more aggressive and prone to antisocial behavior and delinquency (Gershoff, 2002). They see their parents resort to spanking when they become angry and frustrated, so, in turn, they may act out this same behavior when they become angry and frustrated. For example, because you spank Margot when you are angry with her for her misbehavior, she might start hitting her friends when they won’t share their toys.

While positive punishment can be effective in some cases, Skinner suggested that the use of punishment should be weighed against the possible negative effects. Today’s psychologists and parenting experts favor reinforcement over punishment—they recommend that you catch your child doing something good and reward her for it.

Make sure you understand the distinction between negative reinforcement and punishment in the following video:

You can view the transcript for “Learning: Negative Reinforcement vs. Punishment” here (opens in new window) .

Still confused? Watch the following short clip for another example and explanation of positive and negative reinforcement as well as positive and negative punishment.

You can view the transcript for “Operant Conditioning” here (opens in new window) .

In his operant conditioning experiments, Skinner often used an approach called shaping. Instead of rewarding only the target behavior, in shaping , we reward successive approximations of a target behavior. Why is shaping needed? Remember that in order for reinforcement to work, the organism must first display the behavior. Shaping is needed because it is extremely unlikely that an organism will display anything but the simplest of behaviors spontaneously. In shaping, behaviors are broken down into many small, achievable steps. The specific steps used in the process are the following: Reinforce any response that resembles the desired behavior. Then reinforce the response that more closely resembles the desired behavior. You will no longer reinforce the previously reinforced response. Next, begin to reinforce the response that even more closely resembles the desired behavior. Continue to reinforce closer and closer approximations of the desired behavior. Finally, only reinforce the desired behavior.

Shaping is often used in teaching a complex behavior or chain of behaviors. Skinner used shaping to teach pigeons not only such relatively simple behaviors as pecking a disk in a Skinner box, but also many unusual and entertaining behaviors, such as turning in circles, walking in figure eights, and even playing ping pong; the technique is commonly used by animal trainers today. An important part of shaping is stimulus discrimination. Recall Pavlov’s dogs—he trained them to respond to the tone of a bell, and not to similar tones or sounds. This discrimination is also important in operant conditioning and in shaping behavior.

Here is a brief video of Skinner’s pigeons playing ping pong.

You can view the transcript for “BF Skinner Foundation – Pigeon Ping Pong Clip” here (opens in new window) .

It’s easy to see how shaping is effective in teaching behaviors to animals, but how does shaping work with humans? Let’s consider parents whose goal is to have their child learn to clean his room. They use shaping to help him master steps toward the goal. Instead of performing the entire task, they set up these steps and reinforce each step. First, he cleans up one toy. Second, he cleans up five toys. Third, he chooses whether to pick up ten toys or put his books and clothes away. Fourth, he cleans up everything except two toys. Finally, he cleans his entire room.

Primary and Secondary Reinforcers

Rewards such as stickers, praise, money, toys, and more can be used to reinforce learning. Let’s go back to Skinner’s rats again. How did the rats learn to press the lever in the Skinner box? They were rewarded with food each time they pressed the lever. For animals, food would be an obvious reinforcer.

What would be a good reinforce for humans? For your daughter Sydney, it was the promise of a toy if she cleaned her room. How about Joaquin, the soccer player? If you gave Joaquin a piece of candy every time he made a goal, you would be using a primary reinforcer. Primary reinforcers are reinforcers that have innate reinforcing qualities. These kinds of reinforcers are not learned. Water, food, sleep, shelter, sex, and touch, among others, are primary reinforcers . Pleasure is also a primary reinforcer. Organisms do not lose their drive for these things. For most people, jumping in a cool lake on a very hot day would be reinforcing and the cool lake would be innately reinforcing—the water would cool the person off (a physical need), as well as provide pleasure.

A secondary reinforcer has no inherent value and only has reinforcing qualities when linked with a primary reinforcer. Praise, linked to affection, is one example of a secondary reinforcer, as when you called out “Great shot!” every time Joaquin made a goal. Another example, money, is only worth something when you can use it to buy other things—either things that satisfy basic needs (food, water, shelter—all primary reinforcers) or other secondary reinforcers. If you were on a remote island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and you had stacks of money, the money would not be useful if you could not spend it. What about the stickers on the behavior chart? They also are secondary reinforcers.

Sometimes, instead of stickers on a sticker chart, a token is used. Tokens, which are also secondary reinforcers, can then be traded in for rewards and prizes. Entire behavior management systems, known as token economies, are built around the use of these kinds of token reinforcers. Token economies have been found to be very effective at modifying behavior in a variety of settings such as schools, prisons, and mental hospitals. For example, a study by Cangi and Daly (2013) found that use of a token economy increased appropriate social behaviors and reduced inappropriate behaviors in a group of autistic school children. Autistic children tend to exhibit disruptive behaviors such as pinching and hitting. When the children in the study exhibited appropriate behavior (not hitting or pinching), they received a “quiet hands” token. When they hit or pinched, they lost a token. The children could then exchange specified amounts of tokens for minutes of playtime.

Everyday Connection: Behavior Modification in Children

Parents and teachers often use behavior modification to change a child’s behavior. Behavior modification uses the principles of operant conditioning to accomplish behavior change so that undesirable behaviors are switched for more socially acceptable ones. Some teachers and parents create a sticker chart, in which several behaviors are listed (Figure 1). Sticker charts are a form of token economies, as described in the text. Each time children perform the behavior, they get a sticker, and after a certain number of stickers, they get a prize, or reinforcer. The goal is to increase acceptable behaviors and decrease misbehavior. Remember, it is best to reinforce desired behaviors, rather than to use punishment. In the classroom, the teacher can reinforce a wide range of behaviors, from students raising their hands, to walking quietly in the hall, to turning in their homework. At home, parents might create a behavior chart that rewards children for things such as putting away toys, brushing their teeth, and helping with dinner. In order for behavior modification to be effective, the reinforcement needs to be connected with the behavior; the reinforcement must matter to the child and be done consistently.

Time-out is another popular technique used in behavior modification with children. It operates on the principle of negative punishment. When a child demonstrates an undesirable behavior, she is removed from the desirable activity at hand (Figure 2). For example, say that Sophia and her brother Mario are playing with building blocks. Sophia throws some blocks at her brother, so you give her a warning that she will go to time-out if she does it again. A few minutes later, she throws more blocks at Mario. You remove Sophia from the room for a few minutes. When she comes back, she doesn’t throw blocks.

There are several important points that you should know if you plan to implement time-out as a behavior modification technique. First, make sure the child is being removed from a desirable activity and placed in a less desirable location. If the activity is something undesirable for the child, this technique will backfire because it is more enjoyable for the child to be removed from the activity. Second, the length of the time-out is important. The general rule of thumb is one minute for each year of the child’s age. Sophia is five; therefore, she sits in a time-out for five minutes. Setting a timer helps children know how long they have to sit in time-out. Finally, as a caregiver, keep several guidelines in mind over the course of a time-out: remain calm when directing your child to time-out; ignore your child during time-out (because caregiver attention may reinforce misbehavior); and give the child a hug or a kind word when time-out is over.

Think It Over

- Explain the difference between negative reinforcement and punishment, and provide several examples of each based on your own experiences.

- Think of a behavior that you have that you would like to change. How could you use behavior modification, specifically positive reinforcement, to change your behavior? What is your positive reinforcer?

CC licensed content, Original

- Modification and adaptation, addition of Big Bang Learning example. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Operant conditioning interactive. Authored by : Jessica Traylor for Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

CC licensed content, Shared previously

- Operant Conditioning. Authored by : OpenStax College. Located at : https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/6-3-operant-conditioning . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

All rights reserved content

- BF Skinner Foundation – Pigeon Ping Pong Clip. Provided by : bfskinnerfoundation. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vGazyH6fQQ4 . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Learning: Negative Reinforcement vs. Punishment. Authored by : ByPass Publishing. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=imkbuKomPXI . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Operant Conditioning. Authored by : Dr. Mindy Rutherford. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LSHJbIJK9TI . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

implementation of a consequence in order to increase a behavior

adding a desirable stimulus to increase a behavior

implementation of a consequence in order to decrease a behavior

adding an undesirable stimulus to stop or decrease a behavior

taking away a pleasant stimulus to decrease or stop a behavior

rewarding successive approximations toward a target behavior

has innate reinforcing qualities (e.g., food, water, shelter, sex)

has no inherent value unto itself and only has reinforcing qualities when linked with something else (e.g., money, gold stars, poker chips)

General Psychology Copyright © by OpenStax and Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- All Access Pass

- PLR Articles

- PLR Courses

- PLR Social Media

Grab Our Free eBook to Learn How to Grow Your Wellness Business Exponentially!

What is negative reinforcement (a definition), theory of negative reinforcement.

Examples of Negative Reinforcement

Negative punishment vs. negative reinforcement.

- Objective: Negative reinforcement aims to increase the likelihood of a behavior by removing or avoiding an aversive or unpleasant stimulus when the behavior occurs.

- Process: In negative reinforcement, a behavior is strengthened because it leads to the removal or avoidance of something undesirable.

- Example: A student studies hard to avoid failing a test. The aversive stimulus is the threat of failure, and the behavior of studying is reinforced by its removal.

- Objective: Negative punishment, also known as punishment by removal, seeks to decrease the likelihood of a behavior by removing a desirable or positive stimulus when the behavior occurs.

- Process: In negative punishment, a behavior is weakened because it results in the removal of something rewarding or pleasant.

- Example: A child loses their video game privileges (a desirable stimulus) for misbehaving. The behavior that led to the punishment (misbehavior) is less likely to occur in the future.

Negative Reinforcement vs. Positive Reinforcement

- Process: In negative reinforcement, a behavior is strengthened because it leads to the removal or avoidance of something undesirable. The behavior helps escape or avoid the aversive stimulus.

- Example: If a person fastens their seat belt to stop the annoying seat belt reminder sound in their car, the removal of the aversive sound reinforces the behavior of wearing the seat belt.

- Objective: Positive reinforcement aims to increase the likelihood of a behavior by adding a rewarding or pleasant stimulus when the behavior occurs.

- Process: In positive reinforcement, a behavior is strengthened because it results in the addition of something enjoyable or desirable. The behavior is encouraged by the prospect of obtaining a positive stimulus.

- Example: If a child receives a sticker for completing their homework, the addition of the sticker as a reward reinforces the behavior of doing homework.

The Negative Reinforcement Trap

Negative Reinforcement in the Workplace

Negative reinforcement in the classroom, negative reinforcement and drug addiction.

Articles Related to Negative Reinforcement

- Mistakes: Definition, Examples, & How To Learn From Them

- Mind Mapping: Definition & Examples in Psychology

- Perfectionism: Definition, Examples, & Traits

Books Related to Negative Reinforcement

- Reinforcements: How to Get People to Help You

- NEGATIVE REINFORCEMENT & TIME-OUT!: Two POSITIVE Strategies of Classroom Management

- Breaking Negative Thinking Patterns: A Schema Therapy Self-Help and Support Book

Final Thoughts on Negative Reinforcement

Video: negative reinforcement.

Don't Forget to Grab Our Free eBook to Learn How to Grow Your Wellness Business Exponentially!

- Gunter, P. L., & Coutinho, M. J. (1997). Negative reinforcement in classrooms: What we're beginning to learn. Teacher Education and Special Education , 20 (3), 249–264.

- Iwata, B. A. (1987). Negative reinforcement in applied behavior analysis: An emerging technology. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis , 20 (4), 361–378.

- Koob, G. F. (2013). Negative reinforcement in drug addiction: the darkness within. Current Opinion in Neurobiology , 23 (4), 559–563.

- Magoon, M. A., & Critchfield, T. S. (2008). Concurrent schedules of positive and negative reinforcement: differential-impact and differential-outcomes hypothesis. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior , 90 (1), 1–22.

- Papageorgi, I. (2021). Positive and Negative Reinforcement and Punishment. In Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science (pp. 6079–6081). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Perez, R. (2021). Investigating the effects of utilizing motivative augmentals that emphasize positive versus negative reinforcement . California State University, Fresno.

- Staddon, J. E., & Cerutti, D. T. (2003). Operant conditioning. Annual Review of Psychology , 54 (1), 115–144.

- Happiness

- Stress Management

- Self-Confidence

- Manifestation

- All Articles...

- All-Access Pass

- PLR Content Packages

- PLR Courses

Negative Reinforcement (Definition + Examples)

At first glance, “negative reinforcement” might sound uncomfortable or contradictory. Is there such a thing as negative reinforcement or positive punishment?

In the world of behaviorism, yes. Both of those terms exist. You might be surprised to learn that negative reinforcement actually encourages a behavior to happen again!

What is Negative Reinforcement?

Negative Reinforcement is when a stimulus is removed to increase a certain behavior. For example, if a young adult gets up early in the morning to avoid being last in the bathroom, they have increased a certain behavior to avoid the stimulus of waiting in the bathroom.

Punishments and reinforcements could be broken down into positive or negative categories. This doesn’t signify the outcome of the reinforcement; rather, “positive” or “negative” refers to whether a stimulus was added or removed as a response to a behavior. In the case of negative reinforcement, a stimulus is removed. This stimulus was probably burdensome or cumbersome, so removing the stimulus often feels like a relief.

Operant Conditioning

During the early 1900s, psychological experiments focused on understanding behavior, yielding notable works from psychologists Ivan Pavlov and B.F. Skinner, each establishing distinct theories – classical and operant conditioning , respectively.

Ivan Pavlov, an eminent Russian psychologist, is renowned for his pioneering research on classical conditioning , a learning process involving involuntary responses. His widely recognized experiments with dogs provide profound insights into associative learning, where a neutral stimulus (the sound of a bell) became associated with an unconditioned stimulus (food). The dogs eventually began to salivate (an involuntary response) merely at the sound of the bell, even without food, illustrating that behavior can be conditioned through association and reflex responses. Notably, classical conditioning underscores learning through association, primarily involving automatic, reflexive behaviors triggered by environmental stimuli.

Contrastingly, B.F. Skinner, arriving a few decades post-Pavlov, concentrated on operant conditioning, which pivots on voluntary behaviors and their consequences. Unlike Pavlov’s work, Skinner's experiments, often involving rats or pigeons, sought to understand how behavior can be shaped and modified by systematically applying rewards (reinforcements) or penalties (punishments).

His objective was to illustrate that behaviors can be manipulated by controlling their outcomes: positive outcomes (reinforcements) tend to increase the probability of a behavior's recurrence, while negative outcomes (punishments) typically decrease it. Skinner was particularly interested in observing how intentional actions, resulting from free will and control, can be predictably influenced by manipulating environmental factors.

In essence, while both psychologists investigated behavioral conditioning, Pavlov’s classical conditioning emphasized involuntary, reflexive behaviors triggered by external stimuli, whereas Skinner’s operant conditioning focused on deliberate behaviors shaped by orchestrated consequences. Both theories, although focusing on different types of behaviors, have substantially informed the understanding of learning and behavior modification, spotlighting how environments influence behaviors in varied contexts.

Examples of Negative Reinforcement in Psychology

One of the most famous yet ethically controversial examples of negative reinforcement emerges from a study in positive psychology conducted by Martin Seligman in the 1960s. Seligman observed an experiment involving dogs placed in harnesses. Some of these dogs were subjected to electric shocks; however, they could be halted if they moved to the other side of an apparatus. Thus, removing the unpleasant stimulus (the electric shock) encouraged the dogs to repeat the behavior (moving to the other side) in the future.

It's crucial to note that while this experiment offers insights into negative reinforcement, it raises significant ethical concerns. The use of electric shocks and the apparent distress caused to the animals involved starkly contrast to modern-day ethical standards for conducting experiments, particularly those involving living beings. Contemporary researchers prioritize minimizing harm and ensuring the welfare of animals used in experimental settings, guided by a comprehensive ethical framework that would prohibit replicating Seligman's original study in present times.

In the context of this experiment, there are additional underlying psychological principles beyond negative reinforcement, such as learned helplessness, which will be further discussed later in the article.

Here are some other examples of negative reinforcement that you may have observed or even experienced:

- A teacher declares that there is no more assigned homework after their class has behaved well at an assembly.

- Every time you go to the beach, you get sunburnt - unless you remember to put sunscreen beforehand.

- You finish all of your work early to avoid rush-hour traffic.

- Your lactose-intolerant friend orders a dairy-free ice cream so they do not experience a stomachache.

- When your child screams loud enough about not wanting to take a bath, you give in, and the child doesn’t have to.

In each example, a stimulus is removed in response to a behavior. The next time the person (or animal) has the choice to do that behavior, they are more likely to do it because they know the negative stimulus may be removed again.

Continuous vs. Partial Negative Reinforcement

Expanding on the concept of continuous reinforcement, it's essential to underscore why this method, despite its efficacy, might be impractical or unfeasible in various situations. Continuous reinforcement entails rewarding every time a desired behavior is executed. Although this approach can rapidly establish and solidify a behavior, it is often impractical due to time, resources, and logistics constraints.

Firstly, continuous reinforcement may be resource-intensive. Rewarding a behavior each time it occurs demands a significant supply of reinforcements, whether they be treats, praise, or other rewards. This could be impractical or economically unviable in real-world scenarios, particularly in contexts like classroom settings or large-scale animal training.

Secondly, administering continuous reinforcement can be incredibly time-consuming and attention-demanding for the one providing the reinforcement. In environments where one individual is managing the behaviors of many, such as a teacher with a large class or a trainer with multiple animals, maintaining a consistent and immediate reward schedule for every instance of a desired behavior can become a logistic challenge.

Moreover, once a behavior is established through continuous reinforcement, it may become notably susceptible to extinction if the reinforcement ceases. If the reward is suddenly no longer provided, the learned behavior might quickly diminish or disappear.

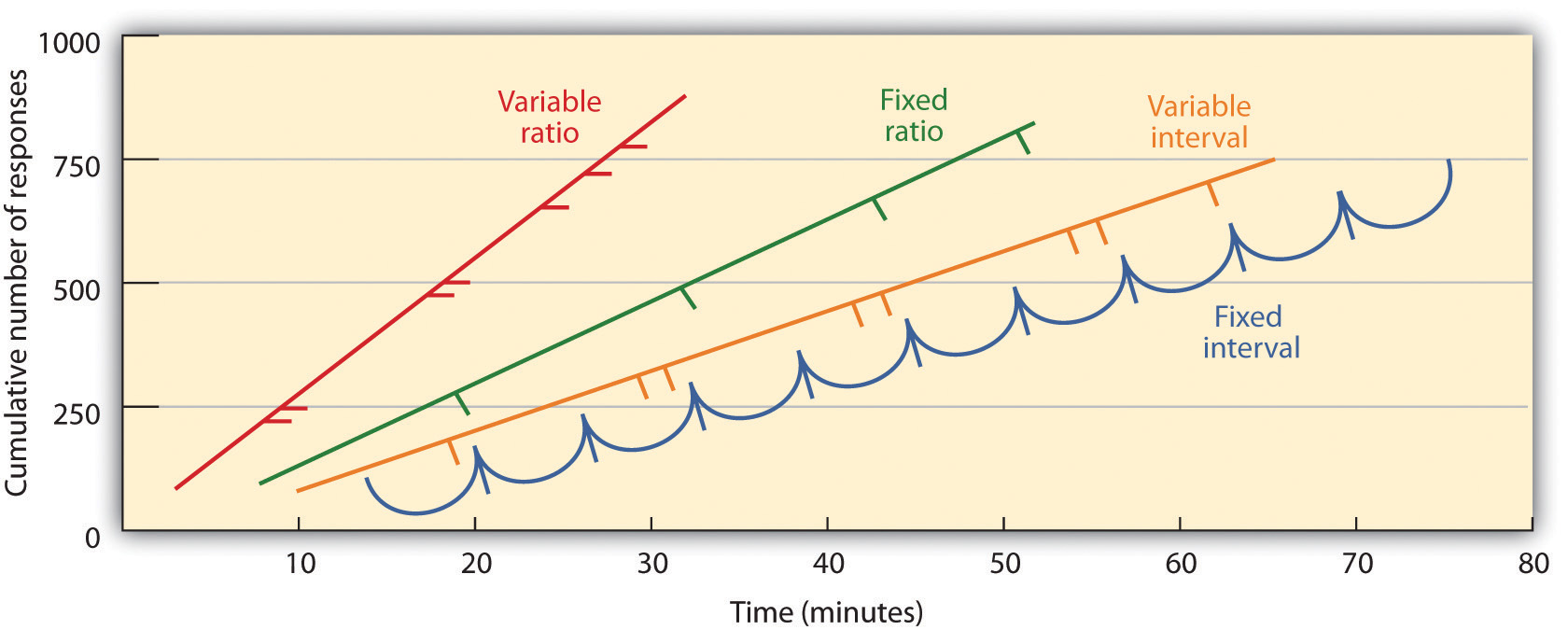

While continuous reinforcement has its challenges and limitations, psychologists like B.F. Skinner has examined alternative reinforcement schedules , notably partial or intermittent reinforcement schedules. These schedules, which include:

- Fixed-ratio: Reinforcement is provided after a specified number of responses.

- Variable-ratio: Reinforcement is provided after an unpredictable number of responses, maintaining an average.

- Fixed-interval: Reinforcement is provided for the first response after a specified time interval has elapsed.

- Variable-interval: Reinforcement is provided for the first response after an unpredictable time interval, maintaining an average.

These schedules introduce an element of variability and unpredictability in reinforcement delivery, which can often be more manageable and similarly effective in maintaining established behaviors, and in some instances, even more resistant to extinction. Exploring these varied schedules allows researchers and practitioners to adapt reinforcement strategies to the practical and contextual demands of different learning and training environments.

Reinforcement Schedules

Fixed-ratio.

In educational psychology, a fixed-ratio schedule provides reinforcement after a set number of desired behaviors. For instance, a teacher might implement this by rewarding students with a "free homework pass" after displaying positive behavior at five assemblies consecutively. This approach can effectively motivate students due to its clarity and predictability: exhibit the desired behavior a specified number of times, and a reward will follow.

However, educators must choose a realistic and achievable ratio to keep students motivated and ensure that the reinforcement is valuable and equitable to all students, considering their diverse needs and abilities. This method provides a clear, straightforward incentive for positive behavior while requiring the mindful application to maintain engagement and fairness in the learning environment.

Variable-ratio

A variable-ratio schedule removes the stimulus in response to an inconsistent number of behaviors. Maybe the assignments are removed after four assemblies of good behavior. Next time, the homework is removed after six assemblies of good behavior. Next time, the homework is removed after two assemblies of good behavior.

Another example of this is the example with the bath mentioned earlier. Every now and again, a parent may be so tired of their child screaming that they take away the stimulus of giving them a dreaded bath. In most cases, this reinforcement is doled out randomly. Yet, the child is still more likely to try at least screaming so that the negative stimulus may be removed. Although negative reinforcement can encourage positive outcomes, being unintentional about reinforcement can also encourage a person (or animal) to encourage negative outcomes.

Fixed-interval

Fixed-interval schedules remove the stimulus in response to a behavior after a fixed interval. The snooze button is a great example of this. You typically have nine minutes to perform a behavior (getting up and turning off your alarm.) If you can perform this behavior, the stimulus (the sound of the alarm) is removed. If you do not perform this behavior, the stimulus remains.

Fixed-interval schedules can be effective, but they often encourage people to just perform the behavior right before the interval. Let’s say children are encouraged to help other students - if they are observed doing so, their homework will be removed on Friday. Every Friday, the teacher goes down the list of students and removes the stimulus from the students who performed the behavior. While some students will be encouraged to perform the behavior early in the week, many will “cram” that behavior into Thursday or Friday. If you are a procrastinator, this isn’t the best schedule for training yourself.

Variable-interval

The final reinforcement schedule is a variable-interval schedule. Instead of taking away homework every Friday for students who helped others throughout the week, the “schedule” is more sporadic. One week, the teacher may take away homework on Friday afternoon. The following week, they may not take it away at all. Next week, they may take it away on Tuesday for students who were observed helping a classmate in the past week.

This is another reinforcement schedule that keeps people on their toes. If they are motivated enough to have the stimulus removed, they are likely to complete the behavior more often. However, this type of conditioning takes time, as the person does not always know when they “should” be performing the behavior.

Is Negative Reinforcement Effective? Exploring Ethical and Long-Term Implications

Negative reinforcement can be a powerful tool to enhance or modify behavior by allowing an individual or an animal to “escape” an aversive stimulus or prevent it from occurring. Everyday actions, such as applying sunscreen to avoid sunburn or paying taxes to sidestep fines, exemplify negative reinforcement in practice – we undertake these actions to dodge undesired outcomes.

However, the efficiency and ethicality of negative reinforcement are multidimensional, varying broadly across situations, populations, and time frames. Consider the ethical aspects: using aversive stimuli, especially in vulnerable populations like children or animals, might raise concerns about welfare and emotional well-being. Moreover, negative reinforcement can sometimes encourage unintended behaviors, such as a child yelling to avoid eating vegetables, particularly if their avoidance behavior is consistently rewarded by conceding parents.

In some instances, the failure to appropriately implement negative reinforcement at initial stages might result in miscomprehensions about the possibility to “escaping” a negative stimulus, leading to variations in its effectiveness.

Long-Term Impacts: Unveiling "Learned Helplessness"

Reflecting on the dog experiment exposes negative reinforcement's potential perils, such as inducing learned helplessness. Dogs unable to escape the shock collar in early trials, irrespective of their actions, became disinclined to attempt desired behaviors due to this learned helplessness. Contrastingly, those who comprehended their ability to control the situation (and thus the removal of the negative stimulus) were more likely to engage in the desired behavior.

In educational or training contexts, prolonged reliance on negative reinforcement might stifle intrinsic motivation, creating individuals or animals that respond merely to avoid adverse outcomes rather than being propelled by internal drive or positive outcomes.

Alternatives to Negative Reinforcement: A Multifaceted Approach

Amidst efforts to navigate behavioral training, whether teaching a dog to sit or encouraging children to consume vegetables, a keen awareness of the stimuli being manipulated in response to behaviors is paramount. It's beneficial to explore diverse forms of operant conditioning, encompassing positive reinforcement and both positive and negative punishment, always ensuring ethical considerations are paramount.

Reddit user shoebox asked the DogTraining subreddit , "If negative reinforcement isn't the right strategy, how do you get your dog to stop behaviors?" The comment section contains ways to reinforce, punish, and prevent behaviors! The ensuing dialogue unveiled many methods to reinforce, punish, and preempt behaviors, underscoring the wealth of alternatives available beyond negative reinforcement.

In summary, negative reinforcement can be potent yet warrants judicious and ethical application, always with an eye toward minimizing any potential negative emotional or psychological impact, particularly in vulnerable populations or in scenarios where the establishment of trust and positive relationship dynamics are crucial.

Related posts:

- Schedules of Reinforcement (Examples)

- Operant Conditioning (Examples + Research)

- Positive Reinforcement (Definition + Examples)

- Variable Interval Reinforcement Schedule (Examples)

- Fixed Ratio Reinforcement Schedule (Examples)

Reference this article:

About The Author

Classical Conditioning

Observational Learning

Latent Learning

Experiential Learning

The Little Albert Study

Bobo Doll Experiment

Spacing Effect

Von Restorff Effect

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

6.3 Operant Conditioning

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define operant conditioning

- Explain the difference between reinforcement and punishment

- Distinguish between reinforcement schedules

The previous section of this chapter focused on the type of associative learning known as classical conditioning. Remember that in classical conditioning, something in the environment triggers a reflex automatically, and researchers train the organism to react to a different stimulus. Now we turn to the second type of associative learning, operant conditioning . In operant conditioning, organisms learn to associate a behavior and its consequence ( Table 6.1 ). A pleasant consequence makes that behavior more likely to be repeated in the future. For example, Spirit, a dolphin at the National Aquarium in Baltimore, does a flip in the air when her trainer blows a whistle. The consequence is that she gets a fish.

Psychologist B. F. Skinner saw that classical conditioning is limited to existing behaviors that are reflexively elicited, and it doesn’t account for new behaviors such as riding a bike. He proposed a theory about how such behaviors come about. Skinner believed that behavior is motivated by the consequences we receive for the behavior: the reinforcements and punishments. His idea that learning is the result of consequences is based on the law of effect, which was first proposed by psychologist Edward Thorndike . According to the law of effect , behaviors that are followed by consequences that are satisfying to the organism are more likely to be repeated, and behaviors that are followed by unpleasant consequences are less likely to be repeated (Thorndike, 1911). Essentially, if an organism does something that brings about a desired result, the organism is more likely to do it again. If an organism does something that does not bring about a desired result, the organism is less likely to do it again. An example of the law of effect is in employment. One of the reasons (and often the main reason) we show up for work is because we get paid to do so. If we stop getting paid, we will likely stop showing up—even if we love our job.

Working with Thorndike’s law of effect as his foundation, Skinner began conducting scientific experiments on animals (mainly rats and pigeons) to determine how organisms learn through operant conditioning (Skinner, 1938). He placed these animals inside an operant conditioning chamber, which has come to be known as a “Skinner box” ( Figure 6.10 ). A Skinner box contains a lever (for rats) or disk (for pigeons) that the animal can press or peck for a food reward via the dispenser. Speakers and lights can be associated with certain behaviors. A recorder counts the number of responses made by the animal.

Link to Learning

Watch this brief video to see Skinner's interview and a demonstration of operant conditioning of pigeons to learn more.

In discussing operant conditioning, we use several everyday words—positive, negative, reinforcement, and punishment—in a specialized manner. In operant conditioning, positive and negative do not mean good and bad. Instead, positive means you are adding something, and negative means you are taking something away. Reinforcement means you are increasing a behavior, and punishment means you are decreasing a behavior. Reinforcement can be positive or negative, and punishment can also be positive or negative. All reinforcers (positive or negative) increase the likelihood of a behavioral response. All punishers (positive or negative) decrease the likelihood of a behavioral response. Now let’s combine these four terms: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment ( Table 6.2 ).

Reinforcement

The most effective way to teach a person or animal a new behavior is with positive reinforcement. In positive reinforcement , a desirable stimulus is added to increase a behavior.