IResearchNet

Deficit Hypothesis

Social science and medical literature, including research on mental health and counseling, has frequently been based on presuppositions that all individuals who differ from members of the sociopolitically dominant cultural group in the United States (i.e., male, heterosexual, Caucasian, Western European Americans of middle-class socioeconomic status and Christian religious affiliation) are deficient by comparison. This deficit hypothesis is particularly apparent in scientific literature presumptions that attribute psychological differences from Caucasians to deviance and pathology.

Deficit Hypothesis and Inferiority Premise

Regarding members of U.S. racial and ethnic minority groups (or people of color)—African American, Hispanic/Latino/a American, Asian American, and American Indian people—the inferiority model is one example of a deficit hypothesis. The inferiority model assumes that the dominant Caucasian group represents the standard for normal or ideal behavior and that cultural groups who differ from these norms are biologically limited and genetically inferior by comparison. In contrast, psychology literature includes critiques that cite how data have been distorted or fabricated to support the inferiority model.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

For example, based on the belief that smaller skull size and underdeveloped brains were biologically determined measures of the inferior intelligence of people of color, Samuel George Morton, in the 19th century, published research findings that supported the prevailing inferiority view. Subsequent scholars (e.g., Stephen Jay Gould) disputed these findings by examining Morton’s data and reporting errors of calculation and omission. Nevertheless, the inferiority deficit hypothesis persisted in the mental health and social science literature and practices of the 20th century. Eminent leaders in early American and British psychology perpetuated the inferiority belief of their times.

In 1904 G. Stanley Hall, the first president of the American Psychological Association, published his belief that Africans, American Indians, and Chinese people were in an adolescent or immature stage of biological evolution compared with the more advanced and civilized development of Caucasian people. Cyril Burt, an influential British psychologist whom many consider the father of educational psychology, published fabricated data to support his contention that Negros inherit inferior brains and lower intelligence compared with Caucasians. In 1976, Robert Guthrie presented a critique of the flawed scientific evidence offered by several researchers who had claimed to verify the inferior intelligence of American Indians and Mexican Americans. In part due to the conclusions drawn from an inferiority deficit hypothesis, people of color who exhibited symptoms of psychological distress were considered unworthy or incapable of benefiting from most psychological or educational interventions. Thus, they were ignored, jailed, or confined to segregated mental hospitals.

The inferiority premise has resurfaced in current times, for example, in the 1994 publication of Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray’s The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life.

Similar to previous investigations based on an inferiority hypothesis, the research of these authors concluded that intelligence is largely inherited and correlated with race; that those who have inferior intelligence (i.e., people of color) should serve those who have superior intelligence (i.e., Caucasians); and that programs purported to promote the intellectual functioning of people of color (e.g., Head Start) are useless, and thus their resources and funding should be reallocated to serve people who are capable of benefiting (i.e., Caucasians of superior intelligence). Subsequently, scholars (e.g., Ronald Samuda, Franz Samelson, Alan Reifman) have refuted these findings and presented empirical evidence that challenges and rejects these conclusions.

Deficit Hypothesis and Cultural Deprivation Premise

In the context of the social activism of the 1950s and 1960s in the United States, the genetic inferiority premise of the deficit hypothesis shifted to a cultural deprivation premise. Similar to the inferiority model, the cultural deprivation model assumes that the dominant Caucasian group represents the standard for normal or ideal behavior. However, this model attributes psychological differences from Caucasians to the various ways in which people of color are socially oppressed, deprived, underprivileged, or deficient in comparison.

The term cultural deprivation emerged from scholars’ writing about poverty in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s (e.g., Frank Riessman’s 1962 book, The Culturally Deprived Child). The deficit hypothesis of cultural deprivation posits that poverty-stricken racial/ethnic minority groups perform poorly in psychological and educational testing and exhibit psychologically unhealthy characteristics because they lack the advantages of Caucasian middle-class culture (e.g., in presumably superior education, books, toys, and formal language). Not only does this premise mistakenly imply that people of color have no valuable cultures of their own, but it also infers that the destructive influences of poverty and racial/ethnic discrimination cause irreparable negative psychosocial differences in their personality characteristics, behavior, and achievement compared with more favorable middle-class Caucasian standards.

In rebuttal, scholars have criticized the scientific merit of the research design and interpretations of findings from studies claiming to support the cultural deprivation model. For example, Abram Kardiner and Lionel Ovesey published a book in 1951, titled The Mark of Oppression, in which they concluded that the basic Negro personality, compared with the general Caucasian personality, is a manifestation of permanent damage, in response to the stigma and obstacles of the social conditions faced by Negroes in U.S. society, which prevents them from developing healthy self-esteem and promotes self-hatred. Scholarly critiques have noted that the authors made these generalizations on the basis of 25 psychoanalytic interviews with African American participants, all of whom but one had identified psychological disturbances, in comparison to a so-called control group of one Caucasian man. Furthermore, Kardiner and Ovesey’s conclusions were disputed for failing to recognize that individuals may respond in a variety of ways (including healthy and unhealthy responses) to stress, hardships, and oppression.

One useful purpose served by studies based on the cultural deprivation premise was the attention paid to the psychosocial and environmental barriers facing people of color and their families. On the other hand, most studies focused only on abnormal and negative aspects in the lives of people of color (e.g., crime and juvenile delinquency). One detrimental implication for cross-cultural counseling is that counselors may similarly attend to and focus on only negative aspects in their assessment and interventions with clients of color. Thus (as noted by scholars such as Elaine Pinderhughes), counselors may misattribute as pathological these clients’ responses to oppression instead of recognizing aspects that may be positive, healthy, and resilient.

Deficit Hypothesis Applications to Other Nondominant Groups

In addition to applications with people of color, the deficit hypothesis may form the basis for some counseling research and practice with other nondominant groups (e.g., by gender, sexual orientation, or religious affiliation). In other words, the deficit hypothesis may be apparent in presumptions that attribute psychological differences from the dominant group in U.S. society (e.g., male, heterosexual, or Christian) to deficiency or pathology. For example, Carol Gilligan’s research findings have disputed an underlying deficit hypothesis regarding gender differences in moral development (i.e., that female participants are deficient in moral reasoning compared with males).

Her research has demonstrated that the moral reasoning of girls and women is different from, instead of inferior to, that of boys and men.

Alternative Premises

Two alternative premises to those that use only one standard of comparison (e.g., Caucasians) are models of counseling and psychotherapy based on cultural differences or diversity. Another alternative perspective to the deficit hypothesis is that of optimal human functioning. In contrast to presuming mental health deficiency in cultural group members who differ from the dominant group, the basic premise of optimal human functioning is that there are many ways to be human and promote healthy development in response to different cultural contexts and human conditions. One implication for cross-cultural counseling research and practice is that this model for conceptualizing healthy development includes both emic (culturally specific) and etic (universal) considerations. These alternative models of personality and human development offer propositions to explore beyond the ethnocentric limitations of the deficit hypothesis.

References:

- Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Guthrie, R. V. (2004). Even the rat was White: A historical view of psychology (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

- Walsh, W. B. (Ed.). (2003). Counseling psychology and optimal human functioning. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Counseling Theories

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Are Twin Deficits?

- First Twin: Fiscal Deficit

- Second Twin: Current Account Deficit

- Current Account Deficit

Twin Deficit Hypothesis

The bottom line.

- Government Spending & Debt

- Government Debt

The Twin Deficits of the U.S.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/image0-MichaelBoyle-d90f2cc61d274246a2be03cdd144f699.jpeg)

Economies that have both a fiscal deficit and a current account deficit are often referred to as having "twin deficits." This means that government revenues are lower than the government's expenses and that the price of the country's imports is greater than the income from its exports.

The United States has had twin deficits since the early 2000s. The opposite scenario—a fiscal surplus and a current account surplus—is generally viewed as preferable, but much depends on the circumstances. China is often cited as an example of a nation that has enjoyed long-term fiscal and current account surpluses.

Key Takeaways

- The U.S.'s twin deficits usually refer to its fiscal and current account deficits.

- A fiscal deficit is a budget shortfall. A current account deficit, roughly speaking, means a country is sending more money overseas for goods and services than it is receiving.

- Many economists argue that the twin deficits are correlated, but there is no clear consensus on the issue.

The First Twin: Fiscal Deficit

A fiscal deficit , or budget deficit, occurs when a nation's spending exceeds its revenues. The U.S. has run fiscal deficits almost every year for decades.

Intuitively, a fiscal deficit doesn't sound like a good thing. But Keynesian economists argue that deficits aren't necessarily harmful, and deficit spending can be a useful tool for jump-starting a stalled economy. When a nation is experiencing a recession , deficit spending on infrastructure and other big projects can contribute to aggregate demand. Workers hired for the projects spend their money, fueling the economy and boosting corporate profits.

Governments often fund fiscal deficits by issuing bonds . Investors buy the bonds, in effect loaning money to the government and earning interest on the loan. When the government repays its debts, investors' principal is returned. Making a loan to a stable government is often viewed as a safe investment. Governments can generally be counted on to repay their debts because their ability to levy taxes gives them a reliable way to generate revenue.

The combined current accounts deficit and budget deficit as a percentage of U.S. GDP, as of July 2023.

The Second Twin: Current Account Deficit

A current account is a measure of a country’s trade and financial transactions with the rest of the world. This includes the difference between the value of its exports of goods and services and its imports, as well as net payments on foreign investments and other transfers from abroad.

In short, a country with a current account deficit is spending more overseas than it is taking in. Again, intuition suggests this isn't good. Those countries must continually borrow money to make up the shortfall, and interest must be paid to service that debt. For smaller, developing countries, especially, this can leave them exposed to international investors and markets.

A sustained deficit of exports versus imports may indicate a country has lost its competitiveness, or reflect an unsustainably low savings rate among the deficit-running country's people.

Current Account Deficit: It's Complicated

But like budget deficits, the truth about current accounts isn't that simple. In practice, a current account deficit can reflect that a country is an attractive destination for investment , as is the case with the U.S. Consider that advanced economies such as the U.S. often run current account deficits while developing economies typically run surpluses.

Some economists believe a large budget deficit is correlated to a large current account deficit. This macroeconomic theory is known as the twin deficit hypothesis. The logic behind the theory is that government tax cuts, which reduce revenue and increase the deficit, result in increased consumption as taxpayers spend their new-found money. The increased spending reduces the national savings rate , causing the nation to increase the amount it borrows from abroad.

When a nation runs out of money to fund its fiscal spending, it often turns to foreign investors as a source of borrowing. At the same time, the nation is borrowing from abroad, its citizens are often using borrowed money to purchase imported goods. At times, economic data supports the twin deficit hypothesis. Other times, the data does not.

Which Country Has the Highest Budget Deficit?

According to World Bank data, Croatia has the highest level of public debt, with a total deficit of 688% of the country's GDP as of 2021. Note that for many countries, the most recent data was unavailable or out of date.

Which Country Has the Highest Trade Deficit?

According to World Bank data, Mozambique has the highest trade deficit as of 2022. The country's current account balance shows a deficit of 35% of the country's GDP. Note that many countries did not have recent figures to report.

Why Is a Trade Deficit Bad?

A trade deficit means that a country is importing more goods than it exports, resulting in high demand for foreign currency and low demand for domestic currency. A consistent trade deficit can be harmful to the domestic economy because local producers do not have enough demand for their goods.

Twin deficits refer to a combined shortfall between a country's government revenues and its export income. Some economists believe that these deficits are related, because low tax revenues can result in increased borrowing from abroad. The United States consistently runs both budget deficits and trade deficits, which some economists predict may lead to unexpected disruptions.

Reuters. " US Twin Deficits Matter for the Dollar, Just Not that Much ."

Cornell Law School. " Taxing Power ."

World Bank. " Central Government Debt, Total (% of GDP) ."

World Bank. " Current Account Balance (% of GDP). "

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-182369493-ab6fd002e31c466ea0aa66fa80b61109.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

What is the Double Deficit in Dyslexia?

Oct 11, 2012 | DM News Blog | 0 comments

You will hear references to the “double deficit” in dyslexics. This is a theory that dyslexics both have a weak phonological awareness (of the sounds in words) and also a poor naming speed rate, when asked to recall words.

We see this pattern in a subset of the children we help learn to read. Phonological weakness is very common, but sometimes you can teach a child to decode confidently yet it never becomes automatic and fluent.

The reason we most commonly find for that is that there is some specialised cortex that can see patterns in apparently random combinations. In these children that is not being engaged. I have no data for it, but my suspicion is that they would be poor at rapid naming too. Anecdotally they tend to have difficulty with word recall.

We engage this bit of cortex with a game we call Word Mash. It forces them to try and spot an anagram of a word in a list of decoys.

When the cortex is engaged, this becomes surprisingly easy. One can scan the list and immediately spot the right word in 1-2 seconds. When you try to do it without engaging the cortex designed for the job, it takes 10-20 seconds.

By making the children try to do the task in a game setting, they seem to engage the cortex and then their reading becomes more fluent.

—–

David Morgan is CEO of Oxford Learning Solutions, publisher of the Easyread System. Easyread is an online course that helps children with dyslexia, auditory processing disorder, and highly visual learning styles improve their reading and spelling through short daily lessons. Find out more at www.easyreadsystem.com or on Facebook at www.facebook.com/easyreadsystem

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- October 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- January 2009

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

The double-deficit hypothesis: a comprehensive analysis of the evidence

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Educational Psychology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

- PMID: 16512081

- DOI: 10.1177/00222194060390010401

The double-deficit hypothesis of developmental dyslexia proposes that deficits in phonological processing and naming speed represent independent sources of dysfunction in dyslexia. The present article is a review of the evidence for the double-deficit hypothesis, including a discussion of recent findings related to the hypothesis. Studies in this area have been characterized by variability in methodology--how dyslexia is defined and identified, and how dyslexia subtypes are classified. Such variability sets limitations on the extent to which conclusions may be drawn with respect to the double-deficit hypothesis. Furthermore, the literature is complicated by the persistent finding that measures of phonological processing and naming speed are significantly correlated, resulting in a statistical artifact that makes it difficult to disentangle the influence of naming speed from that of phonological processing. Longitudinal and intervention studies of the double-deficit hypothesis are needed to accumulate evidence that investigates a naming speed deficit that is independent of a phonological deficit for readers with dyslexia. The existing evidence does not support a persistent core deficit in naming speed for readers with dyslexia.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Dyslexia / etiology*

- Psychological Theory*

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 20 August 2019

Twin deficit hypothesis and reverse causality: a case study of China

- Umer Jeelanie Banday 1 &

- Ranjan Aneja 1

Palgrave Communications volume 5 , Article number: 93 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

12 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

A Correction to this article was published on 01 October 2019

This article has been updated

This paper analyses the causal relationship between budget deficit and current account deficit for the Chinese economy using time series data over the period of 1985–2016. We initially analyzed the theoretical framework obtained from the Keynesian spending equation and empirically test the hypothesis using autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) bounds testing and the Zivot and Andrew (ZA) structural break for testing the twin deficits hypothesis. The results of ARDL bound testing approach gives evidence in support of long-run relationship among the variables, validating the Keynesian hypothesis for the Chinese economy. The result of Granger causality test accepts the twin deficit hypothesis. Our results suggest that the negative shock to the budget deficit reduces current account balance and positive shock to the budget deficit increases current account balance. However, higher effect growth shocks and extensive fluctuation in interest rate and exchange rate lead to divergence of the deficits. The interest rate and inflation stability should, therefore, be the target variable for policy makers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Monetary policy models: lessons from the Eurozone crisis

Pedro J. Gutiérrez-Diez & Tibor Pàl

A systematic review of investment indicators and economic growth in Nigeria

Yusuf Abdulkarim

Military spending crowding out health and education spending: which views are valid in Egypt?

Eman Elish, Hossam Eldien Ahmed & Mostafa E. AboElsoud

Introduction

Fiscal and monetary strategies, when executed lucidly, assume a conclusive part in general macroeconomic stability. The macroeconomic theory which assumes an ideal connection between budget (or fiscal) deficit and trade balance is known as twin deficit hypothesis. The growing literature on twin deficit hypothesis (TDH) has been theoretically and empirically researched by researchers like Kim and Roubini ( 2008 ), Darrat ( 1998 ), Miller and Russek ( 1989 ), Lau and Tang ( 2009 ), Abbas et al. ( 2011 ), Bernheim and Bagwell ( 1988 ), Lee et al. ( 2008 ), Corestti and Muller ( 2006 ), Altintas and Taban ( 2011 ), and Banday and Aneja ( 2016 ).

A study by Tang and Lau ( 2011 ) found that a 1% increase in budget deficit causes 0.43% increase in current account deficit in the US from 1973 to 2008. After the currency crises and Asian financial crises, various countries simultaneously experienced budget deficit and current account deficit. Lau and Tang ( 2009 ) confirmed the twin deficits hypothesis for Cambodia based on cointegration and Granger causality testing. Banday and Aneja ( 2016 ) and Basu and Datta ( 2005 ) confirmed the twin deficits hypothesis for India by applying cointegration and Granger causality testing. Kulkarni and Erickson ( 2011 ) found that, in India and Pakistan trade deficit was driven by the budget deficit. Thomas Laubach ( 2003 ) found that for every one percentage increase in the deficit to GDP ratio, long-term interest rates increase by roughly 25 basis points. The recent study by Engen and Hubbard ( 2004 ) found that when debt increased by 1% of GDP, interest rate would go up by two basis points. China needs to take care of lower interest rate rather than higher interest rate especially on home loans which is very low in real estate market and has created a serious trouble in the economy.

The literature identifies that the FDI “crowding in effect” as an important source of China’s current account surpluses. In fact, the World Developmental Report (1985) demonstrated that a country can promote growth using FDI and technology transfers. China employed such strategies to a remarkable effect on foreign exchange reserves which increased from US$ 155 billion in 1999 to US$ 3.8 trillion by the end of 2013. Since then, there has been a sharp decline in the capital account surplus. The data from the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) showed that in 2015, China recorded a deficit of US$142.4 billion on the capital and financial account. However, it posted a current account surplus of US$ 330.6 billion.

However, majority of the countries are facing both budget deficit and current account deficit. The increasing budget deficit alongside with current account deficit has been an imperative issue for policy makers in China. Besides, given the importance on free trade, decentralization and development there is a need to understand the association between budget deficit and trade imbalance in Chinese economy. Few researchers like Burney et al. ( 1992 ), Banday and Aneja ( 2015 ), Lau and Tang ( 2009 ), Corsetti and Müller ( 2006 ) and Ghatak and Ghatak ( 1996 ) have emphasized the issue emerged because of growing budget deficit and its relationship with macroeconomic factors likes interest rate, exchange rate, inflation, and consumption.

In the economic literature there are two distinct theories that show the linkage between budget deficit and current account deficit. The first theory is based on the traditional Keynesian approach, which postulates that current account deficit has a positive relationship with budget deficit. This means that an increase in budget deficit will lead to a current account deficit and a budget surplus will have a positive impact on the current account deficit. The increase in budget deficit will lead to domestic absorption and, thus, increase domestic income, which will lead to an increase in imports and widen the current account deficit. The twin deficits hypothesis is based on the Mundell-Fleming model (Fleming, 1962 ; Mundell, 1963 ), which asserts that an increase in budget deficit will cause an upward shift in interest rate and exchange rate. The increase in interest rates makes it attractive for foreign investors to invest in the domestic market. This increases the domestic demand and leads to an appreciation of the currency, which in turn causes imports to be cheaper and exports costlier. However, the appreciation of domestic currency will increase imports and lead to a current account deficit (Leachman and Francis, 2002 ; Salvatore, 2006 ). Conversely, the Ricardian Equivalence Hypothesis (REH) disagrees with the Keynesian approach. It states that, in a setting of an open economy, there is no correlation between the budget and current account deficits and hence the former would not cause the latter. In other words, a change in governmental tax structure will not have any impact on real interest rate, investments or consumption (Barro, 1989 ; and Neaime, 2008 ). The assumption here is that consumption patterns of consumers will be based on the life cycle model, formulated by Modigliani and Ando in 1957 , which suggests that current consumption depends on the expected lifetime income, rather than on the current income as proposed by the Keynesian model. Furthermore, the permanent income hypothesis developed by Milton Friedman in 1957, states that private consumption will increase only with a permanent increase in income. This means that a temporary rise in income fueled by tax cuts or deficit-financed public spending will increase private savings rather than spending (Barro, 1989 , p. 39; Hashemzadeh and Wilson, 2006 ). As private savings rise, the need for a foreign capital inflow declines. In this situation a current account deficit will not occur (Khalid and Guan, 1999 , p. 390).

This paper attempts to find out how strong is the relationship between budget and current account deficits in China? Addressing this question is relevant for both policy and academic perspectives. Policymakers would like to know to what extent fiscal adjustment contributes to addressing external disequilibria, especially in the case of increasing external and fiscal imbalances. Secondly, we examined the effects of budget deficit on the current account in the multivariate framework, and also have derived the general relationship among those variables. The study is based on ARDL model to investigate twin deficit hypothesis for china both in short-run and long-run. Further, we analyze the direction of causality if such a relationship exists. We utilize econometric methods for example, ARDL bound testing approach and Granger causality test to achieve these goals. In section “Theoretical Background and Literature Review” we explore the theoretical foundation of the twin deficits hypothesis. Section “Macroeconomics Aspects of the Chinese Economy” will give Macroeconomics Aspects of the Chinese Economy. Section “Data and Empirical results” describes data and empirical results. Section “Results and Discussion” provides empirical results and section “Conclusions”, provides conclusion to the study.

Theoretical background and literature review

The theoretical relationship between budget deficit and current account deficit can be represented by the national income accounting identity:

where IM stand for imports, EX for exports, S p for private savings, I for real investments, G for government expenditure, T for taxes, and TR for transfer payments. When IM is greater than EX, the country has current account deficit. From the right-hand side of the equation, when (G + TR − T) is greater than 0, the country is running a budget deficit. The difference between budget deficit and current account deficit must equal the private savings and investments which are shown below.

In the literature, various studies attempt to find the relationship between budget deficit and current account deficit for different countries or groups of countries using various methods depending upon the sample size and pre-testing of the data. The researchers have generally focused on the U.S economy because of its simultaneous budget and current account deficit since 1980s (Miller and Russek, 1989 ; Darrat, 1998 ; Tallman and Rosensweig, 1991 ; Bahmani-Oskooee, 1992 ). However, researchers from different countries have studied twin deficit hypothesis and obtained different results for different countries (Like India, U.S and Brazil) ((Bernheim, 1988 ; Holmes, 2011 ; Salvatore, 2006 ; Mukhtar et al. 2007 ; Kulkarni and Erickson, 2011 ; Banday and Aneja, 2016 ; Ganchev, 2010 ; Lau and Tang, 2009 ; Rosensweig and Tallman, 1993 ; Fidrmuc, 2002 ; Khalid and Guan, 1999 )). These studies do not support the REH but rather accept the Keynesian traditional theory, finding that budget deficit does have an impact on current account deficit in the long run. There are studies that support the Ricardian equivalence theorem which denies any correlation between budget deficit and current account deficit (Feldstein, 1992 ; Abell, 1990 ; Kaufmann et al. 2002 ; Enders and Lee, 1990 ; Kim, 1995 ; Boucher, 1991 ; Nazier and Essam, 2012 ; Khalid, 1996 ; Modigliani and Sterling, 1986 ; Ratha, 2012 ; Kim and Roubini, 2008 ; Algieri, 2013 ; Rafiq, 2010 ). These contradictory results may be due to differences in the sample period and the methods of measuring variables, which use different econometric techniques.

Khalid ( 1996 ) researched 21 developing countries from the period of 1960–1988, taking three variables into consideration: real private consumption, real per capita gross domestic product (GDP) as a proxy of real disposable income and real per capita government consumption expenditure as a proxy of real public consumption. This was done using Johansen cointegration (1988) and full information maximum likelihood (FIML) for parameter estimates. The model gives us restricted and unrestricted parameter estimations when restricted parameters are used, meaning that parameter estimation is non-linear when testing the REH for the sample countries. The results did not reject the REH for twelve of the countries, but the remaining five countries do diverge from the REH. The rejection of Ricardian equivalence in the latter group of countries demonstrates lack of substitutability between government spending and private consumption. Ghatak and Ghatak ( 1996 ) studied variables such as private consumption, government expenditure, income, taxes, private wealth, government bonds, government deficits, investments, government spending and interest on bonds to test the Ricardian Equivalence hypothesis for India for the period from 1950 to 1986. The study employed multi-cointegration analysis and rational expectation estimation, and both the tests rejected the REH, finding evidence that tax cuts induce consumption. Thus, the results invalidate the REH for India.

Ganchev ( 2010 ) rejected the Ricardian equivalence theorem for the Bulgarian economy using monthly time series data for the period 2000–2010. The long-run results of the vector error correlation model (VECM) showed evidence of the structural gap theory, which states that fiscal deficit influences current account deficit. However, vector autoregression (VAR) results did not show any evidence of a short-run relationship between budget deficit and current account deficit. The study, therefore, found that fiscal policy should not be used, in the Bulgarian economy, as a substitute for monetary policies in maintaining the internal equilibrium.

Nazier and Essam ( 2012 ) studied the Egyptian economic data from 1992 to 2010. The data included five variables: GDP, government budget deficit (as primary deficit), current account deficit, real lending interest rate (RIR) and real exchange rate (RER). The study used structural vector autoregression (SVAR) analysis, which also gave an impulse response function (IRF) to capture the impact of budget deficit on current account deficit and real exchange rate. The findings support the twin divergence hypothesis. This contradicts the theoretical framework, which finds that a shock given to a budget deficit leads to an improvement in the current account deficit and exchange rate. Sobrino ( 2013 ) investigated the causality between budget deficit and current account deficit for the small open economy of Peru for the period 1980–2012 using the Granger causality and Wald tests, generalized variance decomposition and the generalized impulse-response function. The study found no evidence of a causal relationship between budget deficit and current account in the short run.

Goyal and Kumar ( 2018 ) investigates the connection between the current account and budget deficit, and the exchange rate, in a structural vector autoregression for India over the period 1996Q2 to 2015 Q4. The impact of oil stuns and the differential effect of consumption and venture propose compositional impacts and supply stuns rule the conduct of India's CAD, directing the total request channel. Ricardian hypothesis is not supported.

Afonso et al. ( 2018 ) studied 193 countries over the period of 1980–2016 using fixed effect model and system GMM model. The results find the existence of fiscal policy reduces the effect of budget deficit on current account deficit. When there is an absence of fiscal policy rule twin deficit hypothesis exists.

Bhat and Sharma ( 2018 ) examines the association between current account deficit and budget deficit for India over the period of 1970–1971 to 2015–2016 using ARDL model. The results accepts Keynesian proposition and rejects Ricardian equivalence theorem. The results find long-run relationship between current account deficit and budget deficit. Rajasekar and Deo ( 2016 ) find the long-run relationship and bidirectional causality between the two deficits in India. Garg and Prabheesh ( 2017 ) investigate the twin deficit for India by using ARDL model and confirm the twin deficit hypothesis. Badinger et al. ( 2017 ) investigated the role of fiscal rules in the relationship between fiscal and external balances for 73 countries over the period of 1985–2012. Their results confirm the twin deficits hypothesis. Litsios and Pilbeam ( 2017 ) investigates Greece, Portugal and Spain using ARDL model. The empirical results suggest negative relationship between saving and current account deficit in all three countries.

It is clear that the research so far has not yielded any concrete evidence regarding the causal relationship between budget deficit and current account deficit. As such there is a disagreement on the causality between the two deficits. In this paper we test the theory with the support of autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) bounds testing approach using data for the emerging country China.

Macroeconomics aspects of the Chinese economy

The Chinese economy has experienced an unparalleled growth rate over the past few decades, with increases in exports, investments and free market reforms from 1979 and an annual GDP growth rate of 10%. The Chinese economy has emerged as the world’s largest economy in terms of purchasing power parity, manufacturing and foreign exchange reserves.

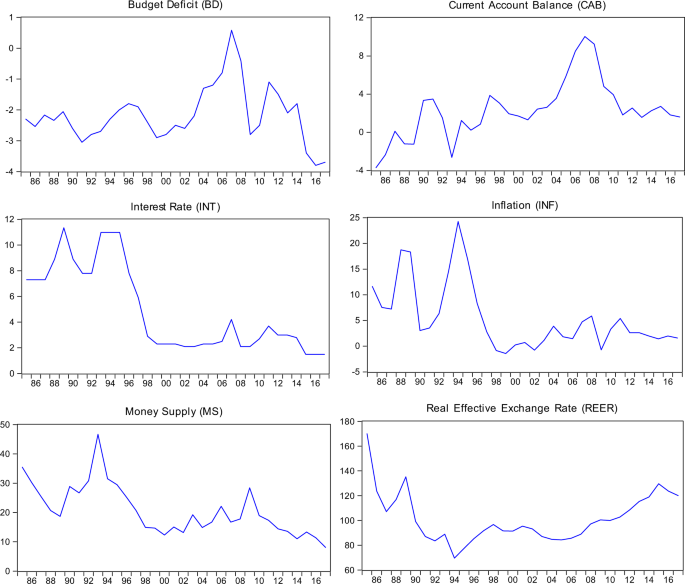

In 2008, the global economic crisis badly affected the Chinese economy, resulting in a decline in exports, imports and foreign direct investments (FDI) inflow and millions of workers losing their jobs. It is visible from the Fig. 1 that China’s current account surplus has dropped significantly from its boom during 2007–2008 financial crises. After the financial crisis, China’s exports fell by 25.7% in February 2009. Further, the exclusive demand for Chinese goods in the international market pushed up current account surplus to 11% of the GDP in 2007, in a global economy (Schmidt and Heilmann, 2010 ). It is said that China responded to the 2008 crisis with a greater fiscal stimulus in terms of tax reduction, infrastructure and subsidies when compared to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries (Herd et al., 2011 ; Morrison, 2011 ).

Behavior of Macroeconomic variables. Overview of Budget Deficit (BD), Current Account Balance (CAB), Interest Rate (INT), Inflation (INF), Money Supply (MS) and Real effective Exchange Rate (REER) from 1985 to 2017. Source: Compiled based on data taken from the World Bank. BD and CAB are expressed as percentage of GDP

However, we draw an important inference from the Fig. 1 , when the budget deficit was lowest (−0.41% of GDP in 2008), the current account surplus increased to 9.23% of the GDP. The negative shock to the budget deficit reduces current account surplus and positive shock to the budget deficit increases current account surplus.

The deprecation of the exchange rate is directly related to the elasticity of demand which improves the exports of the country and finally enhances current account surplus. However, the negative shift in the current account is due to structural and cyclical forces. The cyclic forces can be seen from the trade prospective: the increasing prices of Chinese imports like oil and semiconductors, pulls the current account balance downwards. However, the structural shift can be seen from the financial side, which affects Chinese saving and investments. The investments got reduced to 40% and household savings has reduced from 50% to 40% of GDP.

Data and empirical results

For undertaking the empirical analysis, we use the World Bank data for the following variables. The study covers the period from 1985–2016 and is based secondary data.

Current account deficit (CAD) indicates the value of goods, services and investments imported in comparison with exports on the basis of percentage of the GDP

Budget deficit (BD) indicates the financial health in which expenditure exceeds revenue as a percentage of the GDP

Deposit interest rate (DIR) as a proxy of interest rate (INT) the amount charged by lender to a borrower on the basis of percentage of principals

Inflation (INF) is measured on the basis of consumer price index which reflects annual percentage change in the cost of goods and services

Broad money (MS) a measure of the money supply that indicates the amount of liquidity in the economy. It includes currency, coins, institutional money market funds and other liquid assets based on annual growth rate and real effective exchange rate (REER)

The basic model to find out the relationship among BD, CAD, INF, INT, REER, and MS is as follows:

where INF is inflation and DIR is direct interest rate.

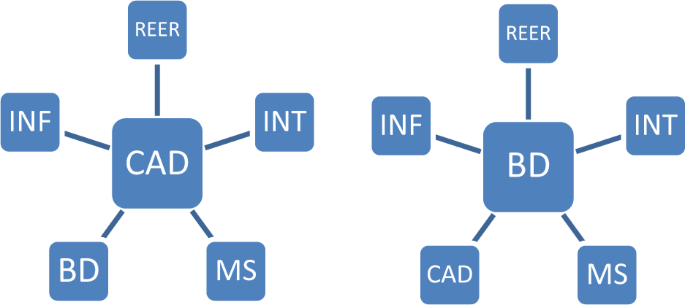

Based on Fig. 2 we will estimate the two models in which CAD and BD is dependent variables and others are independent variables which is as below:

Relationship of the dependent variables (CAD and BD) with other macroeconomic variables

To estimate the above models we have employed various econometric techniques to achieve the objective of the study are as below:

Unit root test to check stationarity of the variables.

ARDL bound testing for long-run and short-run relationship among the variables.

Granger causality to check the causal relationship among the variables.

Empirical results

Unit root test.

As we are using time series data, it is important to check the properties of the data; otherwise, the results of non-stationary variables may be spurious (Granger and Newbold, 1974 ). To assess the integration and unit root among the variables, numerous unit root tests were performed. Apart from applying the unit root test with one structural break (Zivot and Andrews, 1992 ), we also employed a traditional Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) unit root test ( 1981 ) and Phillips-Perron test (PP 1988 ).

To ascertain the order of integration, we first applied the ADF and PP unit root tests. The results of the unit root test suggest that the RER and INF series is integrated of order zero I(0), and other variables are integrated of order I(1). The Zivot and Andrews (ZA) unit root test begins with three models based on Perron ( 1989 ). The ZA model is as follows:

From the above equations, DU t ( λ ) = 1, if t > Tλ , 0 otherwise: DT t ( λ ) = t − T λ if t > T λ , 0 otherwise. The null hypothesis for Eqs. 4 – 6 is α = 0, which implies that ( Yt ) contains a unit root with drift and excludes any structural breakpoints. When α < 0 it simply means that the series having trend-stationary process with a structural break that happens at an unknown point of time. DT t is a dummy variable which implies that shift appears at time TB, where DT t = 1 and DT t = t − TB if t > TB; 0 otherwise. The ZA test (1992) suggests that small sample size distribution can deviate, eventually forming asymptotic distribution. The results of the unit root tests are given below.

The first step in ascertaining the order of integration is to perform ADF and PP unit root tests. Table 1 , above, provides the results of the ADF and PP tests, which suggest that four out of six variables are non-stationary at level and two variable is stationary at level. However, it is important to check the structural breaks and their implications, and the ADF and PP tests are unable to find the structural break in the data series. To avoid this obstacle, we applied a ZA (1992) test with one break, the results of which are given in Table 2 . The structural break test reveals four breaks in Model A. The first, in 1992, may be due to inflation caused by privatization; the second, in 1994 may be due to higher inflation which caused the consumer price index to shot up by 27.5% and imposition of a 17% value-added tax on goods; the third, in 2003, may be due to a 48% decline in state owned enterprises at the same time as a reduction on trade barriers, tariffs and regulations was put in place and the banking system was reformed; the fourth, in 2008, is probably due to the global financial crisis

The ZA test with one structural break gives different results, as all six variables are non-stationary at a 1% level.

ARDL bounds testing approach

We applied the ARDL bounds testing approach to check the cointegration long-run relationship by comparing F -statistics against the critical values for the sample size from 1985 to 2016. The bounds testing framework has an advantage over the cointegration test developed by Pesaran et al. ( 2001 ), in that the bounds testing approach can be applied to variables when that have different orders of integration. Thus, it is inappropriate to apply a Johansen test of cointegration, and we applied ARDL bounds testing to determine the long-run and short-run relationships. The F -statistics are compared with the top and bottom critical values, and if the F -statistics are greater than the top critical values, it means there is a cointegrating relationship among the variables Table 3 .

All values are calculated by using Microfit which defines bounds test critical values as “ k ” which denotes the number of non-deterministic regressors in the long-run relationship, while critical values are taken from Pesaran et al. ( 2001 ). The critical value changes as ‘ k ’ changes. The null hypothesis of the ARDL bound test is Ho: no relationship. We accept the null hypothesis when F is less than the critical value for I(0) regressors and we reject null hypothesis when F is greater than critical value for I(1) regressors. For t-statistics we accept the null hypothesis when t is greater than the critical value and reject the null hypothesis when t is less than the critical value.

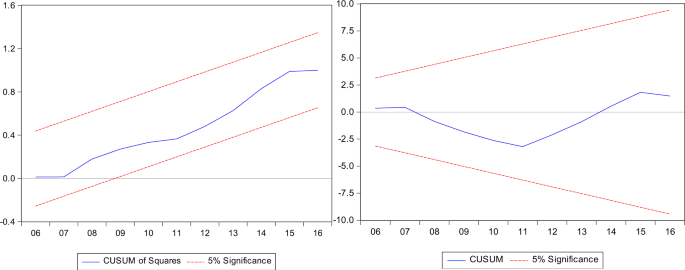

As seen in Table 4 , the calculated F -statistic F = 9.439 is higher than the upper bound critical value 3.99 at the 5% level. The results over the period of 1985 to 2016 suggest that there is a long run relationship among the variables and the null-hypothesis of no cointegration is rejected meaning acceptance of traditional Keynesian approach for China. The bounds test results conclude that there is strong cointegration relationship among budget deficit, current account deficit, interest rate, exchange rate, inflation and money supply. Since the F-statistic was greater than the upper bound critical value, we performed a diagnostic testing based on auto-correlation, normality and heteroskedasticity, the results of which were insignificant based on the respective P -values. The Fig. 3 gives the results of CUSUM and CUSUMSQ tests which check the stability of the coefficient of the regression model. The CUSUM test is based on the sum of recursive residuals, and the CUSUMSQ test is based on the sum of the squared recursive residual. Both the graphs are stable, and the sum does not touch the red lines. Hence there were no issue of serial corelation, Heteroscedasticity and normaility in this model see Table 5 .

CUSUM and CUSUMSQ stability tests. Plot of cumulative sum of recursive residuals and plot of cumulative sum of squares of recursive residuals

Long-run and short-run relationship

After discovering the cointegrating relationship among the variables, it is important to determine the long-run and short-run relationships using the ARDL model.

The above Eqs. 7 , 8 of the ARDL model capture the short and long-run relationship among the variables. The model is based on Schwarz Bayesian Criteria (SBC) optimized over 20,000 replications. The lagged error correction term (ECM) is estimated from the ARDL model. The coefficient ECM t −1 should be negative and significant to yield the evidence of a long run relationship and speed of equilibrium (Banerjee et al. 1993). The results of Eqs. 7 , 8 are provided in Table 6 . The results find a strong long-run relationship among the variables for the period from 1985 to 2016.

At 5% level of significance the long-term estimates of the ARDL model find evidence of the twin deficits hypothesis for China, as all the variables are found to be significant at this level. Thus, our study upholds the empirical validity of the Keynesian proposition for China, while rejecting the Ricardian equivalence hypothesis.

The short-run results are significant; the coefficients of BD, CAD, INF, and INT are significant at a 5% level. This shows that a small change in the budget deficit has a significant impact on the current account deficit; similarly most of the macroeconomic variableshave a significant impact on the current account deficit. As we found evidence of a long-run relationship, we calculated the lagged ECM from the long-run equations. The negative (−0.95348) ECM coefficient and the high speed of adjustment brought equilibrium to the economy, with the exogenous shocks and endogenous shocks restoring it after a long period.

The Chinese economy is one of the most integrated economies in the world and has emerged as a powerful actor in the global economy. The pace of growth in china’s economy has accelerated since the decades in which there was a higher export promotion due to market liquidity and flexible governmental policies. In the early 1990s, it was reported in the Chinese print media that although the Chinese economy was expanding rapidly, the deficits still existed. These were called ‘hard deficits’ primarily because they were financed by expanding money supply and hence exerted inflationary pressure on the economy (People’s Daily, March 28, 1993). Deficit financing may also increase interest rates because once the monetary accommodation of the deficit is ruled out, the government has to incentivize consumers and firms to buy more government bonds. If the purchase of government bonds does not increase in direct proportion to the rise in deficit, government must borrow more money. This, in turn, crowds out private investment. Such a reduction in the private sector's demand for capital has been summarized by Douglas Holtz–Eakin, the director of the U.S Congressional Budget Office, as a “modestly negative” effect of the tax cut or budget deficits on long - term economic growth.

This study finds that a higher interest rate significantly affects the budget deficit and current account deficit in both the short-run and long-run. Chinese banks are increasing interest rates on home loans that had previously been very low; however, because of its economic bubble, especially in the real estate market, this is creating serious trouble in the economy. This is similar to the American bubble, in which most people were unable to repay loans, creating a financial crisis. Still, China must work within the existing bubble, even though it creates a lack of investments and can cause trouble for economies worldwide. The debt bubble is due to the elimination of loan quotas for banks in an attempt to increase small business. These companies are still struggling to repay that debt, which is almost half the amount of GDP of both private and public debt (The Economist, 2015).

While empirical research shows a statistically significant relationship between higher budget deficits and long-term interest rates, there are differences on the magnitude of the impact. Chinese needs to take care of lower interest rate rather than higher interest rate especially on home loans which was very low; in real estate market which has created a serious trouble in the economy.

It is also important to note that the concept of the deficit includes both hard and soft deficits. The “hard” part of the deficit, being financed by printing money, is inflationary. The “soft” part, being financed by the government's domestic and foreign debts, is non-inflationary. However, they are not reported by the Chinese government.

Moreover, hard deficits and consequent inflation increases capital inflows (to prevent interest rates from rising) and causes current account deficit. In China, deficits occurred as a result of overestimating revenues or underestimating expenditures (Shen and Chen, 1981 ) and contributed to the development of bottle-necks in sectors such as energy, transportation, and communications sectors that are of vital importance for the long-term growth of China. However, given the reluctance of the non-government investors to venture into such low pay-back sectors, the Chinese government’s policy to balance budgets by cutting its capital expenditure can severely restrict the development of these sectors (Luo, 1990 , and Colm and Young, 1968 ).

However, the natural explanation for the external surplus is that the economy follows an export-driven growth model by increasing FDI inflows. In the rising tide of economies, China’s demographic boom has created an economic miracle, allowing them to invest in education and skilled workers that will accordingly benefit the economy.

During the global financial crisis of 2008, the Chinese government combined active fiscal policy and loose monetary policy and introduced a stimulus package of $580 billion (around 20% of China’s GDP) for 2009 and 2010. The package partially offset the drop-in exports and its effect on the economy, so that the economic growth of China remained well above international averages. During this period (2008–2009) the current account surplus, as a percentage of GDP was at its highest and the budget deficit was at its lowest point of the entire decade. Our findings suggest that a strong long-run and short-run relationship exists among the variables. The empirical findings support the Keynesian proposition for Chinese economy.

Granger causality

In this section we attempt to estimate the causality from X t to Y t and vice versa. We apply Granger causality to check the robustness of our results and to detect the nature of the causal relationship among the variables based on Eqs. 9 , 10 .

Table 7 describes the results of Granger causality test. The reverse causality holds in light of the fact that budget deficit cause Granger to the current account deficit. For all the variables, the reverse causality from budget deficit to macro variables and current account deficit to macro variables holds at 5% level of significance. Thus, the results of Granger causality gives us more evidences in support of the Keynesian proposition for China in the light of above data. The reverse causality was not apparent because Chinese economy is one of the most integrated economies with higher capital outflows, export-led growth and export promotion due to market liquidity and flexible governmental policies. While the capital inflow determines a tight fiscal policy to avoid overheating of economy (see author Castillo and Barco ( 2008 ) and Rossini et al. ( 2008 ).

Results and discussion

The ambiguous verdict on the twin deficits hypothesis based on two competing theories: the Keynesian preposition and the Ricardian Equivalence theorem. In this paper we investigated the link between budget deficit and current account deficit with an emphasis on the impact of macro-variables shock on current account balance and budget deficit in the Chinese economy over the period 1985–2016.

The conclusion of this study is based on ARDL bound testing approach. The model is based on Schwarz Bayesian Criteria (SBC) optimized over 20,000 replications. With this data and analysis, we conclude that there is a long-run and short-run relationship among the variables. We accept the Keynesian hypothesis, which means we did not find evidence in support of the Ricardian Equivalence theorem in the Chinese economy. This was surprising because higher governmental expenditure and flexible governmental policies could have pushed up the current account deficit. We further applied Granger causality test the results concluded that there is a strong inverse causal relationship between budget deficit and current account deficit meaning that Keynesian preposition is more plausible than Ricardian Equivalence theorem in the light of above data. Our results are consistent with Banday and Aneja, ( 2019 ); Banday and Aneja, ( 2016 ); Ganchev, 2010 ; Bhat and Sharma ( 2018 ); Badinger et al. ( 2017 ), and Afonso et al. ( 2018 ).

The findings of the Granger causality test revealed that there exists bidirectional causality running from budget deficit to current account balance and vice versa in China. A similar movement of the budget deficit and the current account balance is the thing that one would expect when there are cyclic shocks to output. Detailed empirical findings highlight that the interest rate bubble and higher inflated housing prices are becoming a challenge for the Chinese economy, as they are now nearing the prices of the US bubble before the financial crisis popped it. If the US increases interest rates, the money will flow out of the Chinese market, which could cause a similar crisis in China. It will be a challenge for the monetary authority to bring stability in China where inflation, interest rate bubble and exchange rate volatility are of primary concern. Expenditure reduction for low payback sectors, such as energy and communication, could also be a worry in the future. Rising inflation can significantly increase the inflow of capital due to an increase in domestic demand; this can lead to a current account deficit, as it is now more than half of the GDP. The indebtedness in the economy is at its peak, and this can crush the financial cycle and cause financial crisis.

Conclusions

The cointegration investigation confirms the presence of a long-run relationship between the variables. The results propose that there is a positive connection between the current account deficit and fiscal deficit. Our outcomes show that increase in money supply and the devaluation of the exchange rate increases current account balance. The effects of the current account deficit and the exchange rate have been taken as exogenous. A long-run stationary association between the fiscal deficit, current account deficit, interest rate, inflation, money supply, and the exchange rate has been found for China. Granger causality tests reveal bidirectional causality running from budget deficit to current account balance and macroeconomic variables to budget deficit and current account balance.

A genuine answer for the issue of budget deficit and current account deficit lies with a coherent package comprising of both fiscal and monetary approaches. It must concentrate on stable interest rate, inflation target and monetary position will supplement the budget-cut policies. The findings of the paper will be helpful for future empirical models, which attempt to further highlight the transmission mechanism.

Data availability

For undertaking the empirical analysis, we use the World Bank data for the following variables. The study covers the period from 1985 to 2016 and is based on secondary data which are available at: https://data.worldbank.org/country/china .

Change history

01 october 2019.

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

Abell JD (1990) Twin deficits during the 1980s: an empirical investigation. J Macroecon 12(1):81–96

Article Google Scholar

Abbas SA, Bouhga-Hagbe J, Fatás A, Mauro P, Velloso RC (2011) Fiscal policy and the current account. IMF Econ Rev 59(4):603–629

Afonso A, Huart F, Jalles JT, Stanek, PL (2018) Twin deficits revisited: a role for fiscal institutions? REM working paper, 031-2018

Algieri B (2013) An empirical analysis of the nexus between external balance and government budget balance: the case of the GIIPS countries. Econ Syst 37(2):233–253

Altintas H, Taban S (2011) Twin deficit problem and Feldstein-Horioka hypothesis in Turkey: ARDL bound testing approach and investigation of causality. Int Res J Financ Econ 74:30–45

Google Scholar

Badinger H, Fichet de Clairfontaine A, Reuter WH (2017) Fiscal rules and twin deficits: the link between fiscal and external balances. World Econ 40(1):21–35

Bahmani-Oskooee M (1992) What are the long-run determinants of the US trade balance? J Post Keynes Econ 15(1):85–97

Banday UJ, Aneja R (2015) The link between budget deficit and current account deficit in Indian economy. Jindal J Bus Res 4(1-2):1–10

Banday UJ, Aneja R (2016) How budget deficit and current account deficit are interrelated in Indian economy. Theor Appl Econ 23(1 (606):237–246

Banday UJ, Aneja R (2019) Ricardian equivalence: empirical evidences from China. Asian Aff Am Rev 0(1–18):2019

Barro RJ (1989) The Ricardian approach to budget deficits. J Econ Perspect 3(2):37–54

Basu S, Datta D (2005) Does fiscal deficit influence trade deficit?: an econometric enquiry. Economic and Political Weekly, 3311–3318

Bernheim BD (1988) Budget deficits and the balance of trade. Tax policy Econ 2:1–31

Bernheim BD, Bagwell K (1988) Is everything neutral? J Political Econ 96(2):308–338

Bhat JA, Sharma NK (2018) The twin-deficit hypothesis: revisiting Indian economy in a nonlinear framework. J Financ Econ Policy 10(3):386–405

Boucher JL (1991) The US current account: a long and short run empirical perspective. South Econ J 93–111

Burney NA, Akhtar N, Qadir G (1992) Government budget deficits and exchange rate determination: evidence from Pakistan [with Comments]. Pak Dev Rev 31(4):871–882

Castillo P, Barco D (2008) Facing up a sudden stop of capital flows: Policy lessons from the 90’s Peruvian experience (No. 2008-002)

Colm G, Young M (1968) In search of a new budget rule. Public Budgeting and Finance: Readings in Theory and Practice. FE Peacock Publishers, Itasca, IL, p 186–202

Corsetti G, Müller GJ (2006) Twin deficits: squaring theory, evidence and common sense. Econ Policy 21(48):598–638

Darrat AF (1998) Tax and spend, or spend and tax? An inquiry into the Turkish budgetary process. South Econ J 940–956

Dickey DA, Fuller WA (1981) Likelihood ratio statistics for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Econometrica: J Econometric Soc 1057–1072

Enders W, Lee BS (1990) Current account and budget deficits: twins or distant cousins? The Review of economics and Statistics 72(3):373–381

Engen EM, Hubbard RG (2004) Federal government debt and interest rates. NBER Macroecon Annu 19:83–138

Feldstein M (1992) Analysis: the budget and trade deficits aren’t really twins. Challenge 35(2):60–63

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Fidrmuc J (2002) Twin deficits: Implications of current account and fiscal imbalances for the accession countries. Focus Transit 2(2002):72–83

Fleming JM (1962) Domestic financial policies under fixed and under floating exchange rate. Staff Pap Int Monet Fund 10:369–380

Ganchev GT (2010) The twin deficit hypothesis: the case of Bulgaria. Financ theory Pract 34(4):357–377

Garg B, Prabheesh KP (2017) Drivers of India’s current account deficits, with implications for ameliorating them. J Asian Econ 51:23–32

Ghatak A, Ghatak S (1996) Budgetary deficits and Ricardian equivalence: the case of India, 1950–1986. J Public Econ 60(2):267–282

Goyal A, Kumar A (2018) The effect of oil shocks and cyclicality in hiding Indian twin deficits. J Econ Stud 45(no. 1):27–45

Granger CW, Newbold P (1974) Spurious regressions in econometrics. J Econ 2(2):111–120

Article MATH Google Scholar

Hashemzadeh N, Wilson L (2006) The dynamics of current account and budget deficits in selected countries if the Middle East and North. Afr Int Res J Financ Econ 5:111–129

Herd R, Conway P, Hill S, Koen V, Chalaux T (2011) Can India achieve double-digit growth?. OECD Economic Department Working Papers, (883), 0_1

Holmes MJ (2011) Threshold cointegration and the short-run dynamics of twin deficit behaviour. Res Econ 65(3):271–277

Kaufmann S, Scharler J, Winckler G (2002) The Austrian current account deficit: driven by twin deficits or by intertemporal expenditure allocation? Empir Econ 27(3):529–542

Khalid AM (1996) Ricardian equivalence: empirical evidence from developing economies. J Dev Econ 51(2):413–432

Khalid AM, Guan TW (1999) Causality tests of budget and current account deficits: cross-country comparisons. Empir Econ 24(3):389–402

Kim KH (1995) On the long-run determinants of the US trade balance: a comment. J Post Keynes Econ 17(3):447–455

Kim S, Roubini N (2008) Twin deficit or twin divergence? Fiscal policy, current account, and real exchange rate in the US. J Int Econ 74(2):362–383

Kulkarni KG, Erickson EL (2001) Twin deficit revisited: evidence from India, Pakistan and Mexico. Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR) 17(2):(90–104)

Lau LJ (1990) Chinese economic reform: how far, how fast? In: Bruce J. Reynolds (ed) Academic Press, New York, 1988. pp. viii+ 233

Lau E, Tang TC (2009) Twin deficits in Cambodia: are there reasons for concern? An empirical study. Monash University, Deartment Economics, Disscussion Papers 11(09):1–9

Laubach T (2003) New evidence on the interest rate effects of budget deficits and debt. Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2003-12, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, May

Leachman LL, Francis B (2002) Twin deficits: apparition or reality? Appl Econ 34:1121–1132

Lee MJ, Ostry MJD, Prati MA, Ricci MLA, Milesi-Ferretti MGM (2008) Exchange rate assessments: CGER methodologies (No. 261). International Monetary Fund

Litsios I, Pilbeam K (2017) An empirical analysis of the nexus between investment, fiscal balances and current account balances in Greece, Portugal and Spain. Econ Model 63:143–152

Miller SM, Russek FS (1989) Are the twin deficits really related? Contemp Econ Policy 7(4):91–115

Mukhtar T, Zakaria M, Ahmed M (2007) An empirical investigation for the twin deficits hypothesis in Pakistan. J Econ Coop 28(4):63–80

Mundell RA (1963) Capital mobility and stabilization policy under fixed and flexible exchange rate. Can J Econ Political Sci 29(4):475–85

Modigliani F, Ando AK (1957) Tests of the life cycle hypothesis of savings: comments and suggestions. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 19(2):99–124

Modigliani F, Sterling A (1986) Government debt, government spending and private sector behavior: comment. Am Econ Rev 76(5):1168–1179

Morrison WM (2011) China-US trade issues. Curr Polit Econ North West Asia 20(3):409

Nazier H, Essam M (2012) Empirical investigation of twin deficits hypothesis in Egypt (1992–2010). Middle East Financ Econ J 17:45–58

Neaime S (2008) Twin Deficits in Lebanon: A Time Series Analysis, American University of Beirut Institute of Financial Economics, Lecture and Working Paper Series, No. 2

Perron P (1989) The great crash, the oil price shock, and the unit root hypothesis. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 57(6):1361–1401

Pesaran MH, Shin Y, Smith RJ (2001) Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J Appl Econ 16(3):289–326

Phillips PC, Perron P (1988) Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika 75:335–346

Rafiq S (2010) Fiscal stance, the current account and the real exchange rate: some empirical estimates from a time-varying framework. Struct Change Econ Dyn 21(4):276–290

Rajasekar T, Deo M (2016) The Relationship Between Fiscal Deficit and Trade Deficit in India: An Empirical Enquiry Using Time Series Data. The IUP Journal of Applied 28 Economics 15(1)

Ratha A (2012) Twin deficits or distant cousins? Evidence from India1. South Asia Econ J 13(1):51–68

Article ADS Google Scholar

Rosensweig JA, Tallman EW (1993) Fiscal policy and trade adjustment: are the deficits really twins? Econ Inq 31(4):580–594

Rossini R, Quispe Z, Gondo R (2008) Macroeconomic implications of capital inflows: Peru 1991–2007. In Participants in the meeting (p. 363–387), BIS Papers No 44

Salvatore D (2006) Twin deficits in the G-7 countries and global structural imbalances. J Policy Model 28(6):701–712

Schmidt D, Heilmann S (2010) Dealing with economic crisis in 2008-09: The Chinese Government’s crisis management in comparative perspective. China Anal 77:1–24

Shen J, Chen B (1981) China’s Fiscal System. Economic Research Center, the State Council of the People’s Republic of China (Ed.), Almanac of China’s Economy. Modern Cultural Company Limited, Hong Kong, p 634–654

Sobrino CR (2013) The twin deficits hypothesis and reverse causality: a short-run analysis of Peru. J Econ Financ Adm Sci 18(34):9–15

Tallman EW, Rosensweig JA (1991) Investigating US government and trade deficits. Econ Rev-Fed Reserve Bank Atlanta 76(3):1

Tang TC, Lau E (2011) General equilibrium perspective on the twin deficits hypothesis for the USA. Empir Econ Lett 10(3):245–251

Zivot E, Andrews DWK (1992) Further evidence on the Great Crash, the Oil Price Shock, and the unit root hypothesis. J Bus Econ Stat 10:251–70

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Central University of Haryana, Haryana, India

Umer Jeelanie Banday & Ranjan Aneja

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

UJB did the write-up and then analyzed the results. RA read the paper and made necessary corrections prior to submission. Both authors read and approved the final paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Umer Jeelanie Banday .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Banday, U.J., Aneja, R. Twin deficit hypothesis and reverse causality: a case study of China. Palgrave Commun 5 , 93 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0304-z

Download citation

Received : 21 May 2019

Accepted : 23 July 2019

Published : 20 August 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0304-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

A dynamic analysis of the twin-deficit hypothesis: the case of a developing country.

- Ibrar Hussain

Asia-Pacific Financial Markets (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

- PMC10148703

A Dynamic Analysis of the Twin-Deficit Hypothesis: the Case of a Developing Country

Ibrar hussain.

1 Department of Economics, University of Malakand, Chakdara, Pakistan

2 Department of Economics and Development Studies, University of Swat, Swat, Pakistan

Md Shabbir Alam

3 Department of Economics and Finance College of Business Administration, University of Bahrain, Zallaq, Bahrain

4 Department of Finance, College of Business Administration, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Al kharj, Saudi Arabia

Associated Data

Data will be made available upon request.

The main economic challenge is rising aggregate demand, which leaves the economy short on resources and leads to expanding fiscal and external account deficits. The current study uses autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model to evaluate the twin deficit hypothesis in the context of Pakistan in an effort to find an answer to this question. The study uses augmented ARDL, popularized by McNown et al. (Appl Econ 50:1509–1521, 2018) and Sam et al. (Econ Model 80:130–141, 2019), to address the degenerate problems that might arise while applying the ARDL approach. Two separate models were estimated, one with the current account balance as the dependent variable and the other with the balance of trade. In the long run, both models confirm the conventional interpretation of twin deficit hypothesis in Pakistan, with the causality running only from the fiscal deficit to the balance of trade. Other control variables in both models are crucial in understanding the current account balance and balance of trade. According to models, an increase in the exchange rate, as measured by the log of the nominal effective exchange rate, improves both current account and trade balance, verifying the elasticity approach in the long run. The openness of the economy is found to worsen current account balance, and the result is statistically significant. Contrarily, openness has been improved trade balance, but the result is statistically insignificant. To control a large and persistent external deficit, the government has to reduce its fiscal deficit, and such a strategy would be successful when monetary policy is accommodative.

Introduction

Pakistan’s economy underwent a significant transformation throughout the 1990s, with phases of expansion followed by deflation. To stabilize the economy during the periodic boom and bust cycles, which span three to four years each, fiscal and monetary measures are required. The economy is currently under increasing strain on both the fiscal and foreign fronts as a result of large budget and current account deficits (Hussain et al., 2021 , 2022 ). In order to pay off debt, which takes up a sizeable chunk of the federal budget, in light of declining foreign exchange reserves, the government allocates a sizeable portion of its budget to this purpose. Because of the slow pace of ineffective policy changes, the economy’s structural obstacles have mostly been overlooked for decades (Hussain et al., 2020 ). In contrast to the goal growth rate of 5.4%, the economy has grown at an average annual rate of 4.7% over the past five years, largely as a result of consumer-driven growth. The twin-deficit issue facing the nation is a result of low revenue growth, stagnant exports, and increasing imports. The economy grew at a pitiful 3.29% annual pace in fiscal year 2018–19, much below the optimistic prediction of 6.2%. In the year in question, total investments were 15.4% and total savings were 10.7% of gross domestic product (GDP), resulting in a 4.7% saving-investment difference. With average total revenues of 14.9% and average total expenditures of 20.5% of GDP for the last five years, the average fiscal deficit was 5.6%. The consumers price index (CPI) based inflation rate between July and April of this year averaged 4.8%, and the current account deficit for the 2017–18 fiscal year came to $19.897 billion, or 6.3% of GDP (Economic Survey of Pakistan, 2019 ). Pakistan is currently transitioning from indirect to direct taxation as a result of these reforms. This is why more research is needed on the topic at hand due to factors such as political unrest, erratic macroeconomic policies, natural disasters like flooding, and internal insurgency.