- Open access

- Published: 18 March 2015

A narrative review of research impact assessment models and methods

- Andrew J Milat 1 , 2 ,

- Adrian E Bauman 2 &

- Sally Redman 2 , 3

Health Research Policy and Systems volume 13 , Article number: 18 ( 2015 ) Cite this article

24k Accesses

92 Citations

36 Altmetric

Metrics details

Research funding agencies continue to grapple with assessing research impact. Theoretical frameworks are useful tools for describing and understanding research impact. The purpose of this narrative literature review was to synthesize evidence that describes processes and conceptual models for assessing policy and practice impacts of public health research.

The review involved keyword searches of electronic databases, including MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, EBM Reviews, and Google Scholar in July/August 2013. Review search terms included ‘research impact’, ‘policy and practice’, ‘intervention research’, ‘translational research’, ‘health promotion’, and ‘public health’. The review included theoretical and opinion pieces, case studies, descriptive studies, frameworks and systematic reviews describing processes, and conceptual models for assessing research impact. The review was conducted in two phases: initially, abstracts were retrieved and assessed against the review criteria followed by the retrieval and assessment of full papers against review criteria.

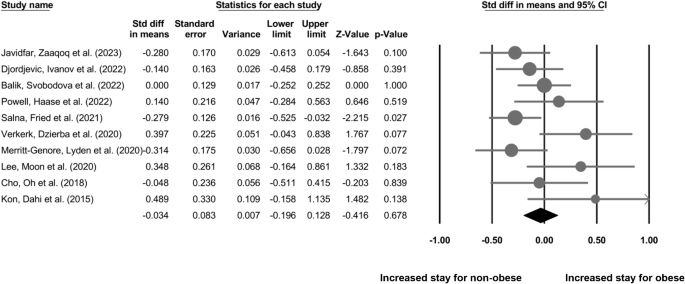

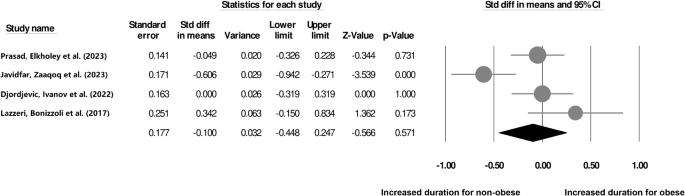

Thirty one primary studies and one systematic review met the review criteria, with 88% of studies published since 2006. Studies comprised assessments of the impacts of a wide range of health-related research, including basic and biomedical research, clinical trials, health service research, as well as public health research. Six studies had an explicit focus on assessing impacts of health promotion or public health research and one had a specific focus on intervention research impact assessment. A total of 16 different impact assessment models were identified, with the ‘payback model’ the most frequently used conceptual framework. Typically, impacts were assessed across multiple dimensions using mixed methodologies, including publication and citation analysis, interviews with principal investigators, peer assessment, case studies, and document analysis. The vast majority of studies relied on principal investigator interviews and/or peer review to assess impacts, instead of interviewing policymakers and end-users of research.

Conclusions

Research impact assessment is a new field of scientific endeavour and there are a growing number of conceptual frameworks applied to assess the impacts of research.

Peer Review reports

There is increasing recognition that health research investment should lead to improvements in policy [ 1 - 3 ], practice, resource allocation, and, ultimately, the health of the community [ 4 , 5 ]. However, research impacts are complex, non-linear, and unpredictable in nature and there is a propensity to ‘count what can be easily measured’, rather than measuring what ‘counts’ in terms of significant, enduring changes [ 6 ].

Traditional academic-oriented indices of research productivity, such as number of papers, impact factors of journals, citations, research funding, and esteem measures, are well established and widely used by research granting bodies and academic institutions [ 7 ], but they do not always relate well to the ultimate goals of applied health research [ 6 , 8 , 9 ]. Governments are signaling that research metrics of research quality and productivity are insufficient to determine research value because they say little about the real world benefits of research [ 10 - 12 ]. At the same time, research funders continue to grapple with the fundamental problem of assessing broader impacts of research. This task is made more challenging because there are currently no agreed systematic approaches to measuring broader research impacts, particularly impacts on health policy and practice [ 13 , 14 ].

Recent years have seen the development of a number of frameworks that can assist in better describing and understanding the impact of research. Conceptual frameworks can help organize data collection, analysis, and reporting to promote clarity and consistency in the impact assessments made. In the context of this review, research impact is defined as: “… any type of output of research activities which can be considered a ‘positive return’ for the scientific community, health systems, patients, and the society in general ” [ 13 ], p. 2.

In light of these gaps in the literature, the purpose of this narrative literature review was to synthesize evidence that describes processes and conceptual models for assessing research impacts, with a focus on policy and practice impacts of public health research.

Literature review search strategy

The review involved keyword searches of electronic databases including MEDLINE (general medicine), CINAHL (nursing and allied health), PsycINFO (psychology and related behavioural and social sciences), EBM Reviews, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005 to May 2013, and Google Scholar. Review search terms included ‘research impact’ OR ‘policy and practice’ AND ‘intervention research’ AND ‘translational research’ AND ‘health promotion’ AND ‘public health’.

The review included theoretical and opinion pieces, case studies, descriptive studies, frameworks and systematic reviews describing processes, and conceptual models for assessing research impact.

The review was conducted in two phases in July/August 2013. In phase 1, abstracts were retrieved and assessed against the review criteria. For abstracts that met the review criteria in phase 1, full papers were retrieved and were assessed for inclusion in the final review. Studies included in the review met the following criteria: i) published in English from January 1990 to June 2013; ii) described processes, theories, or frameworks associated with the assessment of research impact; and iii) were theoretical and opinion pieces, case studies, descriptive studies, frameworks, or systematic reviews.

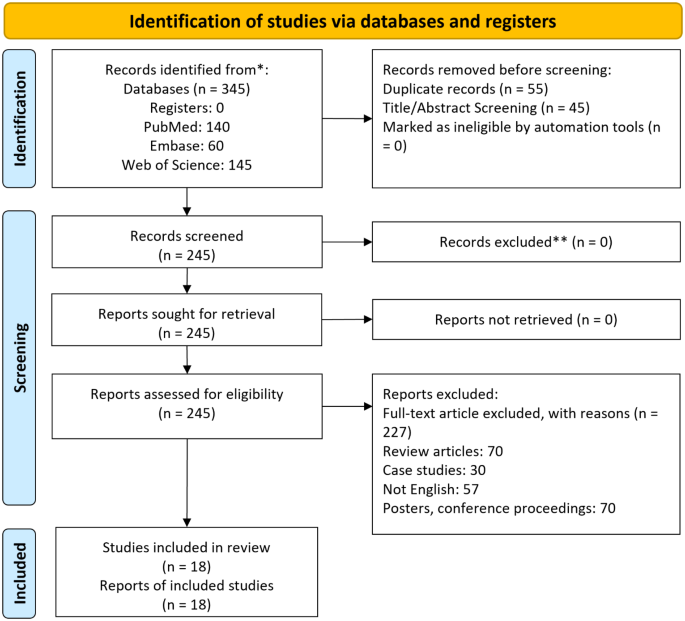

Due the dearth of public health and health promotion-specific research impact assessment, papers with a focus on clinical or health services research impact assessment were included. The reference lists of the final papers were checked to ensure inclusion of further relevant papers; where such articles were considered relevant, they were included in the review. The search process is shown in Figure 1 .

Literature search process and numbers of papers identified, excluded, and included in the review of research impact assessment.

Findings of the literature review

An initial review of abstracts in electronic databases against the inclusion criteria yielded 431 abstracts and searches of reference lists and the grey literature identified a further 9 documents. Of the 434 abstracts and documents reviewed, 39 met the inclusion criteria and full papers were retrieved. Upon review of the full publications against the review criteria, a further 7 papers were excluded as they did not meet the review criteria, leaving 32 publications in the review [ 8 , 9 , 13 , 15 - 44 ]. A summary of characteristics of studies included in the review that have a focus on processes, theories, or frameworks associated with the assessment of research impact including reference details, study type, domains of impact, methods and indicators, frameworks applied or proposed, and key lessons learned is provided in Additional file 1 : Table S1.

Study characteristics

The review identified 31 primary studies and 1 systematic review that met the review criteria. Six of the studies were reports found in the grey literature. Interestingly, 88% of studies that met the review criteria were published since 2006. The studies in the review included assessments of the impacts of a wide range of health-related research, including basic and biomedical research, clinical trials, health service research, as well as public health research. Six studies [ 22 , 23 , 34 , 36 , 40 , 43 ] had an explicit focus on assessing impacts of health promotion or public health research and 1 had a specific focus on intervention research impact assessment [ 36 ].

The majority of studies were conducted in Australia, United Kingdom, and North America, noting that the review was limited to studies published in English. The unit of assessment varied greatly from researchers (research teams [ 22 ] to whole institutions [ 15 ]) to research disciplines (e.g., prevention research [ 23 ], cancer research [ 41 ], tobacco control research [ 43 ]) or type of grants, for example, from public funding bodies [ 17 , 24 ]. The most frequently applied research methods across studies in rank order were publication and citation analysis, interviews with principal investigators, peer assessment, case studies, and document analysis. The nature of frameworks and methods used to measure research impacts will now be examined in greater detail.

Frameworks and methods for measuring research impacts

Indices of traditional research productivity such as number of papers, impact factors of journals, and citations figured prominently in studies in the literature review [ 18 , 23 , 41 ].

Across the majority of studies in this review, research impact was assessed using multiple dimensions and methodological approaches. A total of 16 different impact assessment models were identified, with the ‘payback model’ being the most frequently used conceptual framework [ 15 , 24 , 29 , 31 , 44 ]. Other frequently used models included health economics frameworks [ 19 , 21 , 37 ], variants of Research Program Logic Models [ 9 , 35 , 42 ], and the Research Impact Framework [ 8 , 30 ]. A number of recent frameworks, including the Health Services Research Impact Framework [ 20 ] and the Banzi Health Research Impact Framework [ 13 , 34 , 36 ], are hybrids of previous conceptual approaches and categorize impacts and benefits in many dimensions, trying to integrate them. Commonly applied frameworks identified in the review, including the Payback model, Research Impact Framework, health economics models, and the new hybrid Health Research Impact Framework, will now be examined in greater detail.

The payback model was developed by Buxton and Hanney [ 45 ] and takes into account resources, research processes, primary outputs, dissemination, secondary outputs and applications, and benefits or final outcomes provided by the research. Categories of outcome in the ‘payback’ framework include i) knowledge production (journal articles, books/book chapters, conference proceeding, reports); ii) use of research in the research system (acquisition of formal qualifications by members of the research team, career advancement, and use of project findings for methodology in subsequent research); iii) use of research project findings in health system policy/decision making (findings used in policy/decision making at any level of the health service such as geographic level and organisation level); iv) application of the research findings through changed behaviour (changes in behaviour observed or expected through the application of findings to research-informed policies at a geographical, organisation and population level); v) factors influencing the utilization of research (impact of research dissemination in terms of policy/decision making/behavioural change); and vi) health/health service/economic benefits (improved service delivery, cost savings, improved health, or increased equity).

The model is usually applied as a semi-structured interview guide for researchers to identify the impact of their research and is often accompanied by bibliometric analysis and verification processes. The payback categories have been found to be applicable to assessing impact of research [ 15 , 24 , 29 ], especially the more proximal impacts on knowledge production, research targeting, capacity building and absorption, and informing practice, policy, and product development. The model has been found to be less effective in eliciting information about the longer term categories of impact on health and health sector benefits and economics [ 29 ].

The Research Impact Framework was developed in the UK by Kuruvilla et al. [ 8 , 30 ], and draws upon both the research impact literature and UK research assessment criteria for publically funded research, and was validated through empirical analysis of research projects at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. The framework is built around four categories of impact, namely i) research related, ii) policy, iii) service, and iv) societal. Within each of these areas, further descriptive categories are identified. For example, the nature of research impact on policy can be described using the Weiss categorisation of ‘instrumental use’, where research findings drive policy-making; ‘mobilisation of support’, where research provides support for policy proposals; ‘conceptual use’, where research influences the concepts and language of policy deliberations; and ‘redefining/wider influence’, where research leads to rethinking and changing established practices and beliefs [ 30 ]. The framework is applied as a semi-structured interview guide for researchers to identify the impact of their research. Users of the framework have reported that it enables the systematic identification of a range of specific and verifiable impacts and allows consideration of the unintended effects of research [ 30 ].

The framework proposed by Banzi et al. [ 13 ] is an adaption of the Canadian Academy of Health Science impact model [ 25 ] in light of a systematic review and includes five broad categories of research impact, namely i) advancing knowledge, ii) capacity building, iii) informing decision-making, iv) health and other sector benefits, and v) broad socio-economic benefits. The Banzi framework proposes a set of indicators for each domain. To illustrate, indicators for informing decision making include citation in guidelines, policy documents, and plans; references used as background for successful funding proposals; consulting, support activity, and contributing to advisory committees; patents and industrial collaboration; packages of material and communication to key target audiences about findings. This multidimensional framework takes into account several aspects of research impact and use, as well as comprehensive analytical approaches including bibliometric analysis, surveys, audit, document review, case studies, and panel assessment. Panel assessments generally involve a process asking experts to assess the merits of research against impact criteria.

Economic models used to assess impacts of research varied from cost benefit analysis to return on investment and employed a variety of methods for determining economic benefits of research. The National Institutes of Medicine study in 1993 was among the first studies to attempt to systematically monetize the benefits of medical research. It provided estimates of savings for health care systems (direct costs) and savings for the community as a whole (indirect costs), and quantified benefits in terms of quality adjusted life years. On the other hand, the Deloitte Access Economics study [ 21 ] built on the foundations of the 1993 analysis to estimate the returns on investment in research in Australia for the main disease areas and employed of health system expenditure modelling and monetised total quality adjusted life years gained. According to Buxton et al. [ 19 ], measuring only health care savings is generally seen as too narrow a focus, and their analysis considered the benefits, or indirect cost savings, in avoiding lost production and the further activity stimulated by research.

The aforementioned models all attempted to quantify a mix of more proximal research and policy and practice impacts, as well as more distal societal and economic benefits of research. It is also interesting to note that across the studies in this review, only four [ 16 , 29 , 34 , 36 ] interviewed non-academic end-users of research in impact assessment processes, with the vast majority of studies relying on principal investigator interviews and/or peer review processes to assess impacts.

Comprehensive monitoring and measurement of research impact is a complex undertaking requiring the involvement of many actors within the research pipeline [ 13 ]. Interestingly, 90% of studies that met the review criteria were published since 2006, indicating that this is a new field of research. Given the dearth of literature on public health research impact assessment, this review included assessments of the impacts of a wide range of health-related research, including basic and biomedical research, clinical trials, and health service research as well as public health research.

The review of both the published and grey literature also revealed that there are a number of conceptual frameworks currently being applied that describe processes of assessing research impact. These frameworks differ in their terminology and approaches. The lack of a common understanding of terminology and metrics makes the task of quantifying research efforts, outputs, and, ultimately, performance in this area more difficult.

Most of the models identified in the review used multidimensional conceptualization and categorization of research impact. These multidimensional models, such as the Payback model, Research Impact Framework, and Banzi Health Research Impact Framework, shared common features including assessment of traditional research outputs, such as publication and research funding, but also a broader range of potential benefits, including capacity, building, policy and product development, and service development, as well as broader societal and economic impacts. Assessments that considered more than one category were valued for their ability to capture multifaceted impact processes [ 13 , 36 , 44 ]. Interestingly, these frameworks recognised that research often impacts not only in the country within which research is conducted, but also internationally. However, for practical reasons, most studies limited assessment and verification of impacts to a single country [ 19 , 34 , 36 ].

Several methods were used to practically assess research impact, including desk analysis, bibliometrics, panel assessments, interviews, and case studies. A number of studies highlighted the utility of case study methods noting that a considerable range of research paybacks and perspectives would not have been identified without employing a structured case study approach [ 13 , 36 , 44 ]. However, it was noted that case studies can be at risk of ‘conceptualization bias’ and ‘reporting bias’ especially when they are designed or carried out retrospectively [ 13 ]. The costs of conducting case studies can also be a barrier when assessing large volumes of research [ 13 , 36 ].

Despite recent efforts, little is known about the nature and mechanisms that underpin the influence that health research has on health policy or practice. This review suggests that, to date, most primary studies of health research impacts have been small scale case studies or reviews of medical and health services research funding [ 27 , 31 , 35 , 39 , 41 ], with only two studies offering comprehensive assessments of the policy and practice impacts of public health research, with both focusing on prevention research in Australia.

The first of these aforementioned studies examined impact of population health surveillance studies on obesity prevention policy and practice [ 34 ], while the second [ 36 ] examined the policy and practice impacts of intervention research funded through the NSW Health Promotion Demonstration Research Grants Scheme 2000–2006. Both of these studies utilised comprehensive mixed methods to assess impacts that included semi-structured interviews with both investigators and end-users, bibliometric analysis, document review, verification processes, and case studies. These studies concluded that research projects can achieve the greatest policy and practice impacts if they address proximal needs of the policy context by engaging end-users from the inception of research projects and utilizing existing policy networks and structures, as well as using a range of strategies to disseminate findings that go beyond traditional peer review publications.

This review suggests that the research sector often still uses bibliometric indices to assess research impacts, rather than measuring more enduring and arguably more important policy and practice outcomes [ 6 ]. However, governments are increasingly signaling that research metrics of research quality are insufficient to determine research value because they say little about real world benefits of research [ 10 - 12 ]. The Australian Excellence in Innovation trial [ 26 ] and the UK’s Research Excellence Framework trials [ 28 , 46 ] were commissioned by governments to determine the public benefit from research spending [ 10 , 16 , 47 ].

These attempts raise an important question of how to construct an impact assessment process that can assess multi-dimensional impacts while being feasible to implement on a system level. For example, can 28 indicators across 4 domains of Research Impact Framework be realistically measured in practice? This could also be said of the Research Impact Model [ 13 ], which has 26 indicators, and the Research Excellent Framework by Ovseiko et al. [ 38 ], which has a total of 20 impact indicators. If such methods are to be widely used in practice by research funders and academic institutions to assess research impacts, the right balance between comprehensiveness and feasibility must be struck.

Though a number of studies suggest it is difficult to determine longer-term societal and economic benefits of research as part of multi-dimensional research impact assessment processes [ 13 , 36 , 44 ], the health economic impact models presented in this review and the broader literature demonstrate that it is feasible to undertake these analyses, particularly if the right methods are used [ 19 , 21 , 37 , 48 ].

The review revealed that, where broader policy and practice impacts of research have been assessed in the literature, the vast majority of studies have relied on principal investigator interviews and/or peer review to assess impacts, instead of interviewing policymakers and other important end-users of research. This would seem to be a methodological weakness of previous research, as solely relying on principal investigator assessments, particularly of impacts of their own research, has an inherent bias, leaving the research impact assessment process open to ‘gilding the lily’. In light of this, future impact assessment processes should routinely engage end-users of research in interviews and assessment processes, but also include independent documentary verification, thus addressing methodological limitations of previous research.

One of the greatest practical issues in measuring research impact, including the impact of public health research, are the long lag times before impacts manifest. It has been observed that, on average, it takes over 6 years for research evidence to reach reviews, papers, and textbooks, and a further 9 years for this evidence to be implemented into practice [ 49 ]. In light of this, it is important to allow sufficient time for impacts to manifest, while not waiting so long that these impacts cannot be verified by stakeholders involved in the production and use of the research. Studies in this review have addressed this issue by only assessing studies that had been completed for at least 24 months [ 36 ].

As identified in previous research [ 13 ], a major challenge is attribution of impacts and understanding what would have happened without individual research activity or what some describe as the ‘counterfactual’. Creating a control situation for this type of research is difficult, but, where possible, identification of baseline measures and contextual factors is important in understanding what counterfactual situations may have arisen. Confidence in attribution of effects can be improved by undertaking independent verification of processes and engaging end-users in assessments instead of solely relying on investigators accounts of impacts [ 36 ].

The research described in this review has some limitations that merit closer examination. Given the paucity of research in this area, review criteria had to be adjusted to include assessment of impacts beyond public health research to include all health research. It was also challenging to make direct comparisons across studies mostly due to the heterogeneity of studies and the lack of a standard terminology, hence the broad definition of ‘research impact’ finally applied in the review criteria. Although the majority of studies were found in the traditional biomedical databases (i.e., Medline, etc.), 18% were found in the grey literature highlighting the importance of using multiple data sources in future review processes. Another methodological limitation also identified in previous reviews [ 13 ], is that we did not estimate the level of publication bias and selective publication in this emerging field. Finally, as our analysis included studies published up to June 2013, we may not have captured more recent approaches to impact assessment.

Research impact assessment is a new field of scientific endeavour and typically impacts are assessed using mixed methodologies, including publication and citation analysis, interviews with principal investigators, peer assessment, case studies, and document analysis. The literature is characterised by an over reliance on bibliometric methods to assess research impact. Future impact assessment processes could be strengthened by routinely engaging the end-users of research in interviews and assessment processes. If multidimensional research impact assessment methods are to be widely used in practice by research funders and academic institutions, the right balance between comprehensiveness and feasibility must be determined.

Anderson W, Papadakis E. Research to improve health practice and policy. Med J Aust. 2009;191(11/12):646–7.

PubMed Google Scholar

Cooksey D. A review of UK health research funding. London: HMSO; 2006.

Google Scholar

Health and Medical Research Strategic Review Committee. The virtuous cycle: working together for health and medical research. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 1998.

National Health and Medical Research Council Public Health Advisory Committee. Report of the Review of Public Health Research Funding in Australia. Canberra: NHMRC; 2008.

Campbell DM. Increasing the use of evidence in health policy: practice and views of policy makers and researchers. Aust New Zealand Health Policy. 2009;6:21.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wells R, Whitworth JA. Assessing outcomes of health and medical research: do we measure what counts or count what we can measure? Aust New Zealand Health Policy. 2007;4:14.

Australian Government Australian Research Council. Excellence in Research in Australia 2012. Canberra: Australian Research Council; 2012.

Kuruvilla S, Mays N, Walt G. Describing the impact of health services and policy research. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2007;12 Suppl 1:S1. -23-31.

Weiss AP. Measuring the impact of medical research: moving from outputs to outcomes. Am J Psychiatr. 2007;164(2):206–14.

Bornmann L. Measuring the societal impact of research. Eur Mol Biol Organ. 2012;13(8):673–6.

CAS Google Scholar

Holbrook JB. Re-assessing the science–society relation: The case of the US National Science Foundation’s broader impacts merit review criterion (1997–2011). In: Frodeman R, Holbrook JB, Mitcham C, Xiaonan H, editors. Peer Review, Research Integrity, and the Governance of Science–Practice, Theory, and Current Discussions. Dalian: People’s Publishing House and Dalian University of Technology; 2012. p. 328–62.

Holbrook JB, Frodeman R. Science’s social effects. Issues in Science and Technology. 2007. http://issues.org/23-3/p_frodeman-3/ .

Banzi R, Moja L, Pistotti V, Facchini A, Liberati A. Conceptual frameworks and empirical approaches used to assess the impact of health research: an overview of reviews. health Res Policy Syst. 2011;9:26.

Boaz A, Fitzpatrick S, Shaw B. Assessing the impact of research on policy: A review of the literature for a project on bridging research and policy through outcome evaluation. London: Policy Studies Institute London; 2008.

Aymerich M, Carrion C, Gallo P, Garcia M, López-Bermejo A, Quesada M, et al. Measuring the payback of research activities: a feasible ex-post evaluation methodology in epidemiology and public health. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(3):505–10.

Barber R, Boote JD, Parry GD, Cooper CL, Yeeles P, Cook S. Can the impact of public involvement on research be evaluated? A mixed methods study. Health Expect. 2012;15(3):229–41.

Barker K, The UK. Research Assessment Exercise: the evolution of a national research evaluation system. Res Eval. 2007;16(1):3–12.

Boyack KW, Jordan P. Metrics associated with NIH funding: a high-level view. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(4):423–31.

Buxton M, Hanney S, Morris S, Sundmacher L, Mestre-Ferrandiz J, Garau M, et al. Medical research: what’s it worth. Estimating the economic benefits from medical research in the UK. Report for MRC, Wellcome Trust and the Academy of Medical Sciences. 2008. http://www.wellcome.ac.uk/stellent/groups/corporatesite/@sitestudioobjects/documents/web_document/wtx052110.pdf .

Buykx P, Humphreys J, Wakerman J, Perkins D, Lyle D, McGrail M, et al. ‘Making evidence count’: A framework to monitor the impact of health services research. Aust J Rural Health. 2012;20(2):51–8.

Deloitte Access Economics. Extrapolated returns on investment in NHMRC medical research. Canberra: Australian Society for Medical Research; 2012.

Derrick GE, Haynes A, Chapman S, Hall WD. The association between four citation metrics and peer rankings of research influence of Australian researchers in six fields of public health. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18521.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Franks AL, Simoes EJ, Singh R, Gray BS. Assessing prevention research impact: a bibliometric analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(3):211–6.

Graham KE, Chorzempa HL, Valentine PA, Magnan J. Evaluating health research impact: development and implementation of the Alberta Innovates–Health Solutions impact framework. Res Eval. 2012;21(5):354–67.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Developing a CIHR framework to measure the impact of health research. Ottawa: Canadian Institutes of Health Research; 2005.

Group of Eight. Excellence in innovation: research impacting our nation’s future – assessing the benefits. Adelaide: Australian Technology Network of Universities; 2012.

Hanney S. An assessment of the impact of the NHS Health Technology Assessment Programme. Southampton: National Coordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment, University of Southampton; 2007.

Higher Education Funding Council for England. Panel criteria and working methods. London: Higher Education Funding Council for England; 2012.

Kalucy EC, Jackson-Bowers E, McIntyre E, Reed R. The feasibility of determining the impact of primary health care research projects using the Payback Framework. Health Res Policy Syst. 2009;7:11.

Kuruvilla S, Mays N, Pleasant A, Walt G. Describing the impact of health research: a Research Impact Framework. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6(1):134.

Kwan P, Johnston J, Fung AYK, Chong DSY, Collins RA, Lo SV. A systematic evaluation of payback of publicly funded health and health services research in Hong Kong. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7(1):121.

Landry R, Amara N, Lamari M. Climbing the ladder of research utilization: Evidence from social science research. Sci Commun. 2001;22:396–422.

Lavis J, Ross S, McLeod C, Gildiner A. Measuring the impact of health research. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003;8(3):165–70.

Laws R, King L, Hardy LL, Milat AJ, Rissel C, Newson R, et al. Utilization of a population health survey in policy and practice: a case study. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11:4.

Liebow E, Phelps J, Van Houten B, Rose S, Orians C, Cohen J, et al. Toward the assessment of scientific and public health impacts of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Extramural Asthma Research Program using available data. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(7):1147.

Milat AJ, Laws R, King L, Newson R, Rychetnik L, Rissel C, et al. Policy and practice impacts of applied research: a case study analysis of the New South Wales Health Promotion Demonstration Research Grants Scheme 2000–2006. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11:5.

National Institutes of Health. Cost savings resulting from NIH research support. Bethesda, MD: United States Department of Health and Human Services National Institute of Health; 1993.

Ovseiko PV, Oancea A, Buchan AM. Assessing research impact in academic clinical medicine: a study using Research Excellence Framework pilot impact indicators. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:478.

Schapper CC, Dwyer T, Tregear GW, Aitken M, Clay MA. Research performance evaluation: the experience of an independent medical research institute. Aust Health Rev. 2012;36(2):218–23.

Spoth RL, Schainker LM, Hiller-Sturmhöefel S. Translating family-focused prevention science into public health impact: illustrations from partnership-based research. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;34(2):188.

Sullivan R, Lewison G, Purushotham AD. An analysis of research activity in major UK cancer centres. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(4):536–44.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Taylor J, Bradbury-Jones C. International principles of social impact assessment: lessons for research? J Res Nurs. 2011;16(2):133–45.

Warner KE, Tam J. The impact of tobacco control research on policy: 20 years of progress. Tob Control. 2012;21(2):103–9.

Wooding S, Hanney S, Buxton M, Grant J. The returns from arthritis research. Volume 1: Approach analysis and recommendations. Netherlands: RAND Europe; 2004.

Buxton M, Hanney S. How can payback from health services research be assessed? J Health Serv Res Policy. 1996;1(1):35–43.

Higher Education Funding Council for England. Decisions on assessing research impact. Bristol: Higher Education Funding Council for England; 2011.

Grant J, Brutscher P-B, Kirk SE, Butler L, Wooding S. Capturing research impacts: a review of international practice. Documented Briefing. RAND Corporation; 2010. http://www.rand.org/pubs/documented_briefings/DB578.html .

Murphy KM, Topel RH. Measuring the gains from medical research: an economic approach. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2010.

Balas EA, Boren SA. Managing clinical knowledge for health care improvement. In: Bemmel J, McCray AT, editors. Yearbook of Medical Informatics 2000: Patient-Centered Systems. Stuttgart, Germany: Schattauer Verlagsgesellschaft mbH; 2000. p. 65–70.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

New South Wales Ministry of Health, 73 Miller St North, Sydney, NSW, 2060, Australia

Andrew J Milat

School of Public Health, University of Sydney, Level 2, Medical Foundation, Building, K25, Sydney, NSW, 2006, Australia

Andrew J Milat, Adrian E Bauman & Sally Redman

Sax Institute, Sydney, Level 2, 10 Quay, St Haymarket, NSW, 2000, Australia

Sally Redman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Andrew J Milat .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AJM conceived the study, designed the methods, and conducted the literature searches. AJM drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed to data interpretation and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional file

Additional file 1: table s1..

Characteristics of studies focusing on processes, theories, or frameworks assessing research impact.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Milat, A.J., Bauman, A.E. & Redman, S. A narrative review of research impact assessment models and methods. Health Res Policy Sys 13 , 18 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-015-0003-1

Download citation

Received : 07 November 2014

Accepted : 16 February 2015

Published : 18 March 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-015-0003-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Policy and practice impact

- Research impact

- Research returns

Health Research Policy and Systems

ISSN: 1478-4505

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Skip to main content

- Accessibility help

Information

We use cookies to collect anonymous data to help us improve your site browsing experience.

Click 'Accept all cookies' to agree to all cookies that collect anonymous data. To only allow the cookies that make the site work, click 'Use essential cookies only.' Visit 'Set cookie preferences' to control specific cookies.

Your cookie preferences have been saved. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

Impact assessment in governments: literature review

This report reviews literature regarding five types of policy level impact assessments (environment, equity, health, regulatory, rural) in five countries (Ireland, Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden & Wales). It was commissioned by the Scottish Government to inform their approach to impact assessment.

Key messages from this review

This literature review was commissioned by the Scottish Government to inform their approach to impact assessment. We reviewed the literature regarding five types of policy level impact assessments (environment, equity, health, regulatory, rural) in five countries (Ireland, Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden and Wales). These countries were most likely to require regulatory impact assessment, and least likely to require rural proofing.

More than 1000 potentially useful documents were identified using search engines. Of these, more than 110 plus legislation and guidance informed this report. Much of the literature is somewhat dated; relies on a limited number of case studies; and is carried out by academics who may be testing a hypothesis rather than presenting a balanced view. As such, the findings of this research need to be taken with caution.

What types of assessments are carried out? Scotland has more different types of impact assessment than any other countries studied. New Zealand has climate impact assessment and Wales has wellbeing of future generations assessment, neither of which is carried out in Scotland. Several countries have integrated impact assessments ( e.g. Ireland's RIA , Wales' wellbeing assessment).

What assessment systems are particularly interesting? Welsh wellbeing assessment is interesting because it covers a wide range of impacts, is clearly future-looking, and seems to have strong government support. US 'environmental justice' assessment brings together environmental, health and equality dimensions, and seems effective at leading to changes. These assessment systems apply at the programme or plan level, rather than at policy level.

Are assessments actually carried out? Legally-required assessments are generally carried out, but based on evidence from this review many seem to be a formality, carried out late and/or with little influence on policy-making. However, gaps in the literature were identified relating to the timing of actual assessments and how their findings are used in policy-making.

How effective are the assessments that are carried out? In terms of:

- changes to policies – assessment effectiveness is mixed/limited

- public participation – this is very important for transparency and policy improvement. In practice public engagement is limited, but stakeholder engagement is more common.

- knowledge and learning – there is often learning by policy-makers, with consequent long-term organisational change

- costs v. benefits – not enough information exists to be able to come to a conclusion

In particular, even where an impact assessment does not lead to changes in a policy, it can have benefits in terms of improved transparency and accountability of decision-making, increased awareness of the public, and increased trust between stakeholders.

Is integration of impact assessments advisable? Integration of impact assessments – for instance bringing together environmental, social and economic impact assessment into a 'sustainability assessment' - may promote a more holistic approach to assessment, but care needs to be taken in terms of which elements get the most emphasis. Integration is not just a matter of new legal requirements and guidance: it involves issues of data availability, the number of indicators to use, terminology and frames of reference, build-up of expertise, and intersectoral cooperation. The level of integration depends on issues like what minimum standards or thresholds must be achieved and what trade-offs are permitted.

There is also the 'detail paradox', which states that the power of each objective diminishes with the addition of other objectives: in other words, the more detailed the assessment is, the less significance, on average, is attached to each detail.

What are preconditions for effective assessment? In rough order of importance:

- High-level commitment and supportive organisations

- Policy-makers' willingness to learn and change in response to the assessment findings

- Legal requirement for the impact assessment to be carried out

- Oversight and quality review of the assessments

- Fitting the assessment to the decision in terms of timing, types of alternatives considered, recommendations etc.

- Involvement of the public/stakeholders

- Starting the impact assessment early in the policy-making process

- Adequate funding

- Adequate data and expertise

- Collaboration and information sharing between assessors and government departments

- Follow up to check whether the policy incorporated the assessment recommendations, whether the assessment adequately identified impacts, and how the assessment process can be improved

Email: [email protected]

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback

Your feedback helps us to improve this website. Do not give any personal information because we cannot reply to you directly.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Health Res Policy Syst

Evaluating cancer research impact: lessons and examples from existing reviews on approaches to research impact assessment

Catherine r. hanna.

1 CRUK Clinical Trials Unit, Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom

Kathleen A. Boyd

2 Health Economics and Health Technology Assessment, Institute of Health and Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom

Robert J. Jones

Associated data.

Additional files included. No primary research data analysed.

Performing cancer research relies on substantial financial investment, and contributions in time and effort from patients. It is therefore important that this research has real life impacts which are properly evaluated. The optimal approach to cancer research impact evaluation is not clear. The aim of this study was to undertake a systematic review of review articles that describe approaches to impact assessment, and to identify examples of cancer research impact evaluation within these reviews.

In total, 11 publication databases and the grey literature were searched to identify review articles addressing the topic of approaches to research impact assessment. Information was extracted on methods for data collection and analysis, impact categories and frameworks used for the purposes of evaluation. Empirical examples of impact assessments of cancer research were identified from these literature reviews. Approaches used in these examples were appraised, with a reflection on which methods would be suited to cancer research impact evaluation going forward.

In total, 40 literature reviews were identified. Important methods to collect and analyse data for impact assessments were surveys, interviews and documentary analysis. Key categories of impact spanning the reviews were summarised, and a list of frameworks commonly used for impact assessment was generated. The Payback Framework was most often described. Fourteen examples of impact evaluation for cancer research were identified. They ranged from those assessing the impact of a national, charity-funded portfolio of cancer research to the clinical practice impact of a single trial. A set of recommendations for approaching cancer research impact assessment was generated.

Conclusions

Impact evaluation can demonstrate if and why conducting cancer research is worthwhile. Using a mixed methods, multi-category assessment organised within a framework, will provide a robust evaluation, but the ability to perform this type of assessment may be constrained by time and resources. Whichever approach is used, easily measured, but inappropriate metrics should be avoided. Going forward, dissemination of the results of cancer research impact assessments will allow the cancer research community to learn how to conduct these evaluations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12961-020-00658-x.

Cancer research attracts substantial public funding globally. For example, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in the United States of America (USA) had a 2020 budget of over $6 billion United States (US) dollars. In addition to public funds, there is also huge monetary investment from private pharmaceutical companies, as well as altruistic investment of time and effort to participate in cancer research from patients and their families. In the United Kingdom (UK), over 25,000 patients were recruited to cancer trials funded by one charity (Cancer Research UK (CRUK)) alone in 2018 [ 1 ]. The need to conduct research within the field of oncology is an ongoing priority because cancer is highly prevalent, with up to one in two people now having a diagnosis of cancer in their lifetime [ 2 , 3 ], and despite current treatments, mortality and morbidity from cancer are still high [ 2 ].

In the current era of increasing austerity, there is a desire to ensure that the money and effort to conduct any type of research delivers tangible downstream benefits for society with minimal waste [ 4 – 6 ]. These wider, real-life benefits from research are often referred to as research impact. Given the significant resources required to conduct cancer research in particular, it is reasonable to question if this investment is leading to the longer-term benefits expected, and to query the opportunity cost of not spending the same money directly within other public sectors such as health and social care, the environment or education.

The interest in evaluating research impact has been rising, partly driven by the actions of national bodies and governments. For example, in 2014, the UK government allocated its £2 billion annual research funding to higher education institutions, in part based on an assessment of the impact of research performed by each institution in an assessment exercise known as the Research Excellence Framework (REF). The proportion of funding dependent on impact assessment will increase from 20% in 2014, to 25% in 2021[ 7 ].

Despite the clear rationale and contemporary interest in research impact evaluation, assessing the impact of research comes with challenges. First, there is no single definition of what research impact encompasses, with potential differences in the evaluation approach depending on the definition. Second, despite the recent surge of interest, knowledge of how best to perform assessments and the infrastructure for, and experience in doing so, are lagging [ 6 , 8 , 9 ]. For the purposes of this review, the definition of research impact given by the UK Research Councils is used (see Additional file 1 for full definition). This definition was chosen because it takes a broad perspective, which includes academic, economic and societal views of research impact [ 10 ].

There is a lack of clarity on how to perform research impact evaluation, and this extends to cancer research. Although there is substantial interest from cancer funders and researchers [ 11 ], this interest is not accompanied by instruction or reflection on which approaches would be suited to assessing the impact of cancer research specifically. In a survey of Australian cancer researchers, respondents indicated that they felt a responsibility to deliver impactful research, but that evaluating and communicating this impact to stakeholders was difficult. Respondents also suggested that the types of impact expected from research, and the approaches used, should be discipline specific [ 12 ]. Being cognisant of the discipline specific nature of impact assessment, and understanding the uniqueness of cancer research in approaching such evaluations, underpins the rationale for this study.

The aim of this study was to explore approaches to research impact assessment, identify those approaches that have been used previously for cancer research, and to use this information to make recommendations for future evaluations. For the purposes of this study, cancer research included both basic science and applied research, research into any malignant disease, concerning paediatric or adult cancer, and studies spanning nursing, medical, public health elements of cancer research.

The study objectives were to:

- i. Identify existing literature reviews that report approaches to research impact assessment and summarise these approaches.

- ii. Use these literature reviews to identify examples of cancer research impact evaluations, describe the approaches to evaluation used within these studies, and compare them to those described in the broader literature.

This approach was taken because of the anticipated challenge of conducting a primary review of empirical examples of cancer research impact evaluation, and to allow a critique of empirical studies in the context of lessons learnt from the wider literature. A primary review would have been difficult because examples of cancer research impact evaluation, for example, the assessment of research impact on clinical guidelines [ 13 ], or clinical practice [ 14 – 16 ], are often not categorised in publication databases under the umbrella term of research impact. Reasons for this are the lack of medical subject heading (MeSH) search term relating to research impact assessment and the differing definitions for research impact. In addition, many authors do not recognise their evaluations as sitting within the discipline of research impact assessment, which is a novel and emerging field of study.

General approach

A systematic search of the literature was performed to identify existing reviews of approaches to assess the impact of research. No restrictions were placed on the discipline, field, or scope (national/global) of research for this part of the study. In the second part of this study, the reference lists of the literature reviews identified were searched to find empirical examples of the evaluation of the impact of cancer research specifically.

Data sources and searches

For the first part of the study, 11 publication databases and the grey literature from January 1998 to May 2019 were searched. The electronic databases were Medline, Embase, Health Management and Policy Database, Education Resources Information Centre, Cochrane, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstract, Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, Health Business Elite and Emerald. The search strategy specified that article titles must contain the word “impact”, as well as a second term indicating that the article described the evaluation of impact, such as “model” or “measurement” or “method”. Additional file 1 provides a full list of search terms. The grey literature was searched using a proforma. Keywords were inserted into the search function of websites listed on the proforma and the first 50 results were screened. Title searches were performed by either a specialist librarian or the primary researcher (Dr. C Hanna). All further screening of records was performed by the primary researcher.

Following an initial title screen, 800 abstracts were reviewed and 140 selected for full review. Articles were kept for final inclusion in the study by assessing each article against specific inclusion criteria (Additional file 1 ). There was no assessment of the quality of the included reviews other than to describe the search strategy used. If two articles drew primarily on the same review but contributed a different critique of the literature or methods to evaluate impact, both were kept. If a review article was part of a grey literature report, for example a thesis, but was also later published in a journal, the journal article only was kept. Out of 140 articles read in full, 27 met the inclusion criteria and a further 13 relevant articles were found through reference list searching from the included reviews [ 17 ].

For the second part of the study, the reference lists from the literature reviews were manually screened [ 17 ] ( n = 4479 titles) by the primary researcher to identify empirical examples of assessment of the impact of cancer research. Summary tables and diagrams from the reviews were also searched using the words “cancer” and “oncology” to identify relevant articles that may have been missed by reference list searching. After removal of duplicates, 57 full articles were read and assessed against inclusion criteria (Additional file 1 ). Figure 1 shows the search strategy for both parts of the study according to the guidelines for preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) [ 18 ].

Search strategies for this study

Data extraction and analysis

A data extraction form produced in Microsoft ® Word 2016 was used to collect details for each literature review. This included year of publication, location of primary author, research discipline, aims of the review as described by the authors and the search strategy (if any) used. Information on approaches to impact assessment was extracted under three specific themes which had been identified from a prior scoping review as important factors when planning and conducting research impact evaluation. These themes were: (i) categorisation of impact into different types depending on who or what is affected by the research (the individuals, institutions, or parts of society, the environment), and how they are affected (for example health, monetary gain, sustainability) (ii) methods of data collection and analysis for the purposes of evaluation, and (iii) frameworks to organise and communicate research impact. There was space to document any other key findings the researcher deemed important. After data extraction, lists of commonly described categories, methods of data collection and analysis, and frameworks were compiled. These lists were tabulated or presented graphically and narrative analysis was used to describe and discuss the approaches listed.

For the second part of the study, a separate data extraction form produced in Microsoft ® Excel 2016 was used. Basic information on each study was collected, such as year of publication, location of primary authors, research discipline, aims of evaluation as described by the authors and research type under assessment. Data was also extracted from these empirical examples using the same three themes as outlined above, and the approaches used in these studies were compared to those identified from the literature reviews. Finally, a set of recommendations for future evaluations of cancer research impact were developed by identifying the strengths of the empirical examples and using the lists generated from the first part of the study to identify improvements that could be made.

Part one: Identification and analysis of literature reviews describing approaches to research impact assessment

Characteristics of included literature reviews.

Forty literature reviews met the pre-specified inclusion criteria and the characteristics of each review are outlined in Table Table1. 1 . A large proportion (20/40; 50%) were written by primary authors based in the UK, followed by the USA (5/40; 13%) and Australia (5/40; 13%), with the remainder from Germany (3/40; 8%), Italy (3/40; 8%), the Netherlands (1/40; 3%), Canada (1/40; 3%), France (1/40; 3%) and Iran (1/40; 3%). All reviews were published since 2003, despite the search strategy dating from 1998. Raftery et al. 2016 [ 19 ] was an update to Hanney et al. 2007 [ 20 ] and both were reviews of studies assessing research impact relevant to a programme of health technology assessment research. The narrative review article by Greenhalgh et al. [ 21 ] was based on the same search strategy used by Raftery et al. [ 19 ].

Summary of literature reviews

Approximately half of the reviews (19/40; 48%) described approaches to evaluate research impact without focusing on a specific discipline and nearly the same amount (16/40; 40%) focused on evaluating the impact of health or biomedical research. Two reviews looked at approaches to impact evaluation for environmental research and one focused on social sciences and humanities research. Finally, two reviews provided a critique of impact evaluation methods used by different countries at a national level [ 22 , 23 ]. None of these reviews focused specifically on cancer research.

Twenty-five reviews (25/40; 63%) specified search criteria and 11 of these included a PRISMA diagram. The articles that did not outline a search strategy were often expert reviews of the approaches to impact assessment methods and the authors stated they had chosen the articles included based on their prior knowledge of the topic. Most reviews were found by searching traditional publication databases, however seven (7/40; 18%) were found from the grey literature. These included four reports written by an independent, not-for-profit research institution (Research and Development (RAND) Europe) [ 23 – 26 ], one literature review which was part of a Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D) thesis [ 27 ], a literature review informing a quantitative study [ 28 ] and a review that provided background information for a report to the UK government on the best use of impact metrics [ 29 ].

Key findings from the reviews: approaches to research impact evaluation

Nine reviews attempted to categorise the type of research impact being assessed according to who or what is affected by research, and how they are affected. In Fig. 2 , colour coding was used to identify overlap between impact types identified in these reviews to produce a summary list of seven main impact categories.

Categories of impact identified in the included literature reviews

The first two categories of impact refer to the immediate knowledge produced from research and the contribution research makes to driving innovation and building capacity for future activities within research institutions. The former is often referred to as the academic impact of research. The academic impact of cancer research may include the knowledge gained from conducting experiments or performing clinical trials that is subsequently disseminated via journal publications. The latter may refer to securing future funding for cancer research, providing knowledge that allows development of later phase clinical trials or training cancer researchers of the future.

The third category identified was the impact of research on policy. Three of the review articles included in this overview specifically focused policy impact evaluation [ 30 – 32 ]. In their review, Hanney et al. [ 30 ] suggested that policy impact (of health research) falls into one of three sub-categories: impact on national health policies from the government, impact on clinical guidelines from professional bodies, and impact on local health service policies. Cruz Rivera and colleagues [ 33 ] specifically distinguished impact on policy making from impact on clinical guidelines, which they described under health impact. This shows that the lines between categories will often blur.

Impact on health was the next category identified and several of the reviews differentiated health sector impact from impact on health gains. For cancer research, both types of health impact will be important given that it is a health condition which is a major burden for healthcare systems and the patients they treat. Economic impact of research was the fifth category. For cancer research, there is likely to be close overlap between healthcare system and economic impacts because of the high cost of cancer care for healthcare services globally.

In their 2004 article, Buxton et al. [ 34 ] searched the literature for examples of the evaluation of economic return on investment in health research and found four main approaches, which were referenced in several later reviews [ 19 , 25 , 35 , 36 ]. These were (i) measuring direct cost savings to the health-care system, (ii) estimating benefits to the economy from a healthy workforce, (iii) evaluating benefits to the economy from commercial development and, (iv) measuring the intrinsic value to society of the health gain from research. In a later review [ 25 ], they added an additional approach of estimating the spill over contribution of research to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of a nation.

The final category was social impact. This term was commonly used in a specific sense to refer to research improving human rights, well-being, employment, education and social inclusion [ 33 , 37 ]. Two of the reviews which included this category focused on the impact of non-health related research (social sciences and agriculture), indicating that this type of impact may be less relevant or less obvious for health related disciplines such as oncology. Social impact is distinct from the term societal impact, which was used in a wider sense to describe impact that is external to traditional academic benefits [ 38 , 39 ]. Other categories of impact identified that did not show significant overlap between the reviews included cultural and technological impact. In two of the literature reviews [ 33 , 40 ], the authors provided a list of indicators of impact within each of their categories. In the review by Thonon et al. [ 40 ], only one (1%) of these indicators was specific to evaluating the impact of cancer research.

In total, 36 (90%) reviews discussed methods to collect or analyse the data required to conduct an impact evaluation. The common methods described, and the strengths and weaknesses of each approach, are shown in Additional file 2 : Table S1. Many authors advocated using a mixture of methods and in particular, the triangulation of surveys, interviews (of researchers or research users), and documentary analysis [ 20 , 30 – 32 ]. A large number of reviews cautioned against the use of quantitative metrics, such as bibliometrics, alone [ 29 , 30 , 41 – 48 ]. Concerns included that these metrics were often not designed to be comparable between research programmes [ 49 ], their use may incentivise researchers to focus on quantity rather than quality [ 42 ], and these metrics could be gamed and used in the wrong context to make decisions about researcher funding, employment and promotion [ 41 , 43 , 45 ].

Several reviews explained that the methods for data collection and analysis chosen for impact evaluation depended on both the unit of research under analysis and the rationale for the impact analysis [ 23 , 24 , 26 , 31 , 36 , 50 , 51 ]. Specific to cancer research, the unit of analysis may be a single clinical trial or a programme of trials, research performed at a cancer centre or research funded by a specific institution or charity. The rationale for research impact assessment was categorised in multiple reviews under four headings (“the 4 As”): advocacy, accountability, analysis and allocation [ 19 , 20 , 23 , 24 , 30 – 33 , 36 , 46 , 52 , 53 ]. Finally, Boaz and colleagues found that there was a lack of information on the cost-effectiveness of research impact evaluation methods but suggested that pragmatic, but often cheaper approaches to evaluation, such as surveys, were least likely to give in depth insights into the processes through which research impact occurred [ 31 ].

Applied to research impact evaluation, a framework provides a way of organising collected data, which encourages a more objective and structured evaluation than would be possible with an ad hoc analysis. In total, 27 (68%) reviews discussed the use of a framework in this context. Additional file 2 : Table S2 lists the frameworks mentioned in three or more of the included reviews. The most frequently described framework was the Payback Framework, developed by Buxton and Hanney in 1996 [ 54 ], and many of the other frameworks identified reported that they were developed by adapting key elements of the Payback framework. None of the frameworks identified were specifically developed to assess the impact of cancer research, however several were specific to health research. The unit of cancer research being evaluated will dictate the most suitable framework to use in any evaluation. The unit of research most suited to each framework is outlined in Additional file 2 : Table S2.

Additional findings from the included reviews

The challenges of research impact evaluation were commonly discussed in these reviews. Several mentioned that the time lag [ 24 , 25 , 33 , 35 , 38 , 46 , 50 , 53 , 55 ] between research completion and impact occurring should influence when an impact evaluation is carried out: too early and impact will not have occurred, too late and it is difficult to link impact to the research in question. This overlapped with the challenge of attributing impact to a particular piece of research [ 24 , 26 , 33 – 35 , 37 – 39 , 46 , 50 , 56 ]. Many authors argued that the ability to show attribution was inversely related to the time since the research was carried out [ 24 , 25 , 31 , 46 , 53 ].

Part II: Empirical examples of cancer research impact evaluation

Study characteristics.

In total, 14 empirical impact evaluations relevant to cancer research were identified from the references lists of the literature reviews included in the first part of this study. These empirical studies were published between 1994–2015 by primary authors located in the UK (7/14; 50%), USA (2/14; 14%), Italy (2/14; 14%), Canada (2/14; 14%) and Brazil (1/14; 14%). Table Table2 2 lists these studies with the rationale for each assessment (defined using the “4As”), the unit of analysis of cancer research evaluated and the main findings from each evaluation. The categories of impact evaluated, methods of data collection and analysis, and impact frameworks utilised are also summarised in Table Table2 2 and discussed in more detail below.

Examples of primary studies assessing the impact of cancer research

Approaches to cancer research impact evaluation used in empirical studies

Several of the empirical studies focused on academic impact. For example, Ugolini and colleagues evaluated scholarly outputs from one cancer research centre in Italy [ 57 ] and in a second study looked at the academic impact of cancer research from European countries [ 58 ]. Saed et al. [ 59 ] used submissions to an international cancer conference (American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)) to evaluate the dissemination of cancer research to the academic community, and Lewison and colleagues [ 60 – 63 ] assessed academic, as well as policy impact and dissemination of cancer research findings to the lay media.

The category of the health impact was also commonly evaluated, with particular focus on the assessment of survival gains. Life years gained or deaths averted [ 64 ], life expectancy gains [ 65 ] and years of extra survival [ 66 ] were all used as indicators of the health impact attributable to cancer research. Glover and colleagues [ 67 ] used a measure of health utility, the quality adjusted life year (QALY), which combines both survival and quality of life assessments. Lakdawalla and colleagues [ 66 ] considered the impact of both research on cancer screening and treatments, and concluded that survival gains were 80% attributable to treatment improvement. In contrast, Glover and colleagues [ 67 ] acknowledged the importance of improved cancer therapies due to research but also highlight the major impacts from research around smoking cessation, as well as cervical and bowel cancer screening. Several of these studies that assessed health impact, also used the information on health gains to assess the economic impact of the same research [ 64 – 67 ].

Finally, two studies [ 68 , 69 ] performed multi-dimensional research impact assessments, which incorporated nearly all of the seven categories of impact identified from the previous literature (Fig. 2 ). In their assessment of the impact of research funded by one breast cancer charity in Australia, Donovan and colleagues [ 69 ] evaluated academic, capacity building, policy, health, and wider economic impacts. Montague and Valentim [ 68 ] assessed the impact of one randomised clinical trial (MA17) which investigated the use of a hormonal medication as an adjuvant treatment for patients with breast cancer. In their study, they assessed the dissemination of research findings, academic impact, capacity building for future trials and international collaborations, policy citation, and the health impact of decreased breast cancer recurrence attributable to the clinical trial.

Methods for data collection and analysis used in these studies aligned with the categories of impact assessed. For example, studies assessing academic impact used traditional bibliometric searching of publication databases and associated metrics. Ugolini et al. [ 57 ] applied a normalised journal impact factor to publications from a cancer research centre as an indicator of the research quality and productivity from that centre. This analysis was adjusted for the number of employees within each department and the scores were used to apportion 20% of future research funding. The same bibliometric method of analysis was used in a second study by the same authors to compare and contrast national level, cancer research efforts across Europe [ 58 ]. They assessed the quantity and the mean impact factor of the journals for publications from each country and compared this to the location-specific population and GDP. A similar approach was used for the manual assessment of 10% of cancer research abstracts submitted to an international conference (ASCO) between 2001–2003 and 2006–2008 [ 59 ]. These authors examined if the location of authors affected the likelihood of the abstract being presented orally, as a face-to-face poster or online only.

Lewison and colleagues, who performed four of the studies identified [ 60 – 63 ], used a different bibliometric method of publication citation count to analyse the dissemination, academic, and policy impact of cancer research. The authors also assigned a research level to publications to differentiate if the research was a basic science or clinical cancer study by coding the words in the title of each article or the journal in which the paper was published. The cancer research types assessed by these authors included cancer research at a national level for two different countries (UK and Russia) and research performed by cancer centres in the UK.

To assess policy impact these authors extracted journal publications from cancer clinical guidelines and for media impact they looked at publications cited in articles stored within an online repository from a well-known UK media organisation (British Broadcasting Co-operation). Interestingly, most of the cancer research publications contained in guidelines and cited in the UK media were clinical studies whereas a much higher proportion published by UK cancer centres were basic science studies. These authors also identified that funders of cancer research played an critical role as commentators to explain the importance of the research in the lay media. The top ten most frequent commentators (commenting on > 19 media articles (out of 725) were all representatives from the UK charity CRUK.

A combination of clinical trial findings and documentary analysis of large data repositories were used to estimate health system or health impact. In their study, Montague and Valentim [ 68 ] cited the effect size for a decrease in cancer recurrence from a clinical trial and implied the same health gains would be expected in real life for patients with breast cancer living in Canada. In their study of the impact of charitable and publicly funded cancer research in the UK, Glover et al. [ 67 ] used CRUK and Office for National Statistics (ONS) cancer incidence data, as well as national hospital databases listing episodes of radiotherapy delivered, number of cancer surgeries performed and systemic anti-cancer treatments prescribed, to evaluate changes in practice attributable to cancer research. In their USA perspective study, Lakdawalla et al. [ 66 ] used the population-based Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program (SEER) database to evaluate the number of patients likely to be affected by the implementation of cancer research findings [ 66 ]. Survival calculations from clinical trials were also applied to population incidence estimates to predict the scale of survival gain attributable to cancer research [ 64 , 66 ].

The methods of data collection and analysis used for economic evaluations aligned with the categories of assessment identified by Buxton in their 2004 literature review [ 34 ]. For example, three studies [ 65 – 67 ] estimated direct healthcare cost savings from implementation of cancer research. This was particularly relevant in one ex-ante assessment of the potential impact of a clinical trial testing the equivalence of using less intensive follow up for patients following cancer surgery [ 65 ]. These authors assessed the number of years it would take (“years to payback”) of implementing the hypothetical clinical trial findings to outweigh the money spent developing and running the trial. The return on investment calculation was performed by estimating direct cost savings to the healthcare system by using less intensive follow up without any detriment to survival.

The second of Buxton’s categories was an estimation of productivity loss using the human capital approach. In this method, the economic value of survival gains from cancer research are calculated by measuring the monetary contribution from patients surviving longer who are of working age. This approach was used in two studies [ 64 , 66 ] and in both, estimates of average income (USA) were utilised. Buxton’s fourth category, an estimation of an individual’s willingness to pay for a statistical life, was used in two assessments [ 65 , 66 ], and Glover and colleagues [ 67 ] adapted this method, placing a monetary value on the opportunity cost of QALYs forgone in the UK health service within a fixed budget [ 70 ]. One of the studies that used this method identified that there may be differences in how patients diagnosed with distinct cancer types value the impact of research on cancer specific survival [ 66 ]. In particular, individuals with pancreatic cancer seemed to be willing to spend up to 80% of their annual income for the extra survival attributable to implementation of cancer research findings, whereas this fell to below 50% for breast and colorectal cancer. Only one of the studies considered Buxton’s third category of benefits to the economy from commercial development [ 66 ]. These authors calculated the gain to commercial companies from sales of on-patent pharmaceuticals and concluded that economic gains to commercial producers were small relative to gains from research experienced by cancer patients.