A Step-by-Step Guide to Doing Historical Research [without getting hysterical!] In addition to being a scholarly investigation, research is a social activity intended to create new knowledge. Historical research is your informed response to the questions that you ask while examining the record of human experience. These questions may concern such elements as looking at an event or topic, examining events that lead to the event in question, social influences, key players, and other contextual information. This step-by-step guide progresses from an introduction to historical resources to information about how to identify a topic, craft a thesis and develop a research paper. Table of contents: The Range and Richness of Historical Sources Secondary Sources Primary Sources Historical Analysis What is it? Who, When, Where, What and Why: The Five "W"s Topic, Thesis, Sources Definition of Terms Choose a Topic Craft a Thesis Evaluate Thesis and Sources A Variety of Information Sources Take Efficient Notes Note Cards Thinking, Organizing, Researching Parenthetical Documentation Prepare a Works Cited Page Drafting, Revising, Rewriting, Rethinking For Further Reading: Works Cited Additional Links So you want to study history?! Tons of help and links Slatta Home Page Use the Writing and other links on the lefhand menu I. The Range and Richness of Historical Sources Back to Top Every period leaves traces, what historians call "sources" or evidence. Some are more credible or carry more weight than others; judging the differences is a vital skill developed by good historians. Sources vary in perspective, so knowing who created the information you are examining is vital. Anonymous doesn't make for a very compelling source. For example, an FBI report on the antiwar movement, prepared for U.S. President Richard Nixon, probably contained secrets that at the time were thought to have affected national security. It would not be usual, however, for a journalist's article about a campus riot, featured in a local newspaper, to leak top secret information. Which source would you read? It depends on your research topic. If you're studying how government officials portrayed student activists, you'll want to read the FBI report and many more documents from other government agencies such as the CIA and the National Security Council. If you're investigating contemporary opinion of pro-war and anti-war activists, local newspaper accounts provide a rich resource. You'd want to read a variety of newspapers to ensure you're covering a wide range of opinions (rural/urban, left/right, North/South, Soldier/Draft-dodger, etc). Historians classify sources into two major categories: primary and secondary sources. Secondary Sources Back to Top Definition: Secondary sources are created by someone who was either not present when the event occurred or removed from it in time. We use secondary sources for overview information, to familiarize ourselves with a topic, and compare that topic with other events in history. In refining a research topic, we often begin with secondary sources. This helps us identify gaps or conflicts in the existing scholarly literature that might prove promsing topics. Types: History books, encyclopedias, historical dictionaries, and academic (scholarly) articles are secondary sources. To help you determine the status of a given secondary source, see How to identify and nagivate scholarly literature . Examples: Historian Marilyn Young's (NYU) book about the Vietnam War is a secondary source. She did not participate in the war. Her study is not based on her personal experience but on the evidence she culled from a variety of sources she found in the United States and Vietnam. Primary Sources Back to Top Definition: Primary sources emanate from individuals or groups who participated in or witnessed an event and recorded that event during or immediately after the event. They include speeches, memoirs, diaries, letters, telegrams, emails, proclamations, government documents, and much more. Examples: A student activist during the war writing about protest activities has created a memoir. This would be a primary source because the information is based on her own involvement in the events she describes. Similarly, an antiwar speech is a primary source. So is the arrest record of student protesters. A newspaper editorial or article, reporting on a student demonstration is also a primary source. II. Historical Analysis What is it? Back to Top No matter what you read, whether it's a primary source or a secondary source, you want to know who authored the source (a trusted scholar? A controversial historian? A propagandist? A famous person? An ordinary individual?). "Author" refers to anyone who created information in any medium (film, sound, or text). You also need to know when it was written and the kind of audience the author intend to reach. You should also consider what you bring to the evidence that you examine. Are you inductively following a path of evidence, developing your interpretation based on the sources? Do you have an ax to grind? Did you begin your research deductively, with your mind made up before even seeing the evidence. Historians need to avoid the latter and emulate the former. To read more about the distinction, examine the difference between Intellectual Inquirers and Partisan Ideologues . In the study of history, perspective is everything. A letter written by a twenty- year old Vietnam War protestor will differ greatly from a letter written by a scholar of protest movements. Although the sentiment might be the same, the perspective and influences of these two authors will be worlds apart. Practicing the " 5 Ws " will avoid the confusion of the authority trap. Who, When, Where, What and Why: The Five "W"s Back to Top Historians accumulate evidence (information, including facts, stories, interpretations, opinions, statements, reports, etc.) from a variety of sources (primary and secondary). They must also verify that certain key pieces of information are corroborated by a number of people and sources ("the predonderance of evidence"). The historian poses the " 5 Ws " to every piece of information he examines: Who is the historical actor? When did the event take place? Where did it occur? What did it entail and why did it happen the way it did? The " 5 Ws " can also be used to evaluate a primary source. Who authored the work? When was it created? Where was it created, published, and disseminated? Why was it written (the intended audience), and what is the document about (what points is the author making)? If you know the answers to these five questions, you can analyze any document, and any primary source. The historian doesn't look for the truth, since this presumes there is only one true story. The historian tries to understand a number of competing viewpoints to form his or her own interpretation-- what constitutes the best explanation of what happened and why. By using as wide a range of primary source documents and secondary sources as possible, you will add depth and richness to your historical analysis. The more exposure you, the researcher, have to a number of different sources and differing view points, the more you have a balanced and complete view about a topic in history. This view will spark more questions and ultimately lead you into the quest to unravel more clues about your topic. You are ready to start assembling information for your research paper. III. Topic, Thesis, Sources Definition of Terms Back to Top Because your purpose is to create new knowledge while recognizing those scholars whose existing work has helped you in this pursuit, you are honor bound never to commit the following academic sins: Plagiarism: Literally "kidnapping," involving the use of someone else's words as if they were your own (Gibaldi 6). To avoid plagiarism you must document direct quotations, paraphrases, and original ideas not your own. Recycling: Rehashing material you already know thoroughly or, without your professor's permission, submitting a paper that you have completed for another course. Premature cognitive commitment: Academic jargon for deciding on a thesis too soon and then seeking information to serve that thesis rather than embarking on a genuine search for new knowledge. Choose a Topic Back to Top "Do not hunt for subjects, let them choose you, not you them." --Samuel Butler Choosing a topic is the first step in the pursuit of a thesis. Below is a logical progression from topic to thesis: Close reading of the primary text, aided by secondary sources Growing awareness of interesting qualities within the primary text Choosing a topic for research Asking productive questions that help explore and evaluate a topic Creating a research hypothesis Revising and refining a hypothesis to form a working thesis First, and most important, identify what qualities in the primary or secondary source pique your imagination and curiosity and send you on a search for answers. Bloom's taxonomy of cognitive levels provides a description of productive questions asked by critical thinkers. While the lower levels (knowledge, comprehension) are necessary to a good history essay, aspire to the upper three levels (analysis, synthesis, evaluation). Skimming reference works such as encyclopedias, books, critical essays and periodical articles can help you choose a topic that evolves into a hypothesis, which in turn may lead to a thesis. One approach to skimming involves reading the first paragraph of a secondary source to locate and evaluate the author's thesis. Then for a general idea of the work's organization and major ideas read the first and last sentence of each paragraph. Read the conclusion carefully, as it usually presents a summary (Barnet and Bedau 19). Craft a Thesis Back to Top Very often a chosen topic is too broad for focused research. You must revise it until you have a working hypothesis, that is, a statement of an idea or an approach with respect to the source that could form the basis for your thesis. Remember to not commit too soon to any one hypothesis. Use it as a divining rod or a first step that will take you to new information that may inspire you to revise your hypothesis. Be flexible. Give yourself time to explore possibilities. The hypothesis you create will mature and shift as you write and rewrite your paper. New questions will send you back to old and on to new material. Remember, this is the nature of research--it is more a spiraling or iterative activity than a linear one. Test your working hypothesis to be sure it is: broad enough to promise a variety of resources. narrow enough for you to research in depth. original enough to interest you and your readers. worthwhile enough to offer information and insights of substance "do-able"--sources are available to complete the research. Now it is time to craft your thesis, your revised and refined hypothesis. A thesis is a declarative sentence that: focuses on one well-defined idea makes an arguable assertion; it is capable of being supported prepares your readers for the body of your paper and foreshadows the conclusion. Evaluate Thesis and Sources Back to Top Like your hypothesis, your thesis is not carved in stone. You are in charge. If necessary, revise it during the research process. As you research, continue to evaluate both your thesis for practicality, originality, and promise as a search tool, and secondary sources for relevance and scholarliness. The following are questions to ask during the research process: Are there many journal articles and entire books devoted to the thesis, suggesting that the subject has been covered so thoroughly that there may be nothing new to say? Does the thesis lead to stimulating, new insights? Are appropriate sources available? Is there a variety of sources available so that the bibliography or works cited page will reflect different kinds of sources? Which sources are too broad for my thesis? Which resources are too narrow? Who is the author of the secondary source? Does the critic's background suggest that he/she is qualified? After crafting a thesis, consider one of the following two approaches to writing a research paper: Excited about your thesis and eager to begin? Return to the primary or secondary source to find support for your thesis. Organize ideas and begin writing your first draft. After writing the first draft, have it reviewed by your peers and your instructor. Ponder their suggestions and return to the sources to answer still-open questions. Document facts and opinions from secondary sources. Remember, secondary sources can never substitute for primary sources. Confused about where to start? Use your thesis to guide you to primary and secondary sources. Secondary sources can help you clarify your position and find a direction for your paper. Keep a working bibliography. You may not use all the sources you record, but you cannot be sure which ones you will eventually discard. Create a working outline as you research. This outline will, of course, change as you delve more deeply into your subject. A Variety of Information Sources Back to Top "A mind that is stretched to a new idea never returns to its original dimension." --Oliver Wendell Holmes Your thesis and your working outline are the primary compasses that will help you navigate the variety of sources available. In "Introduction to the Library" (5-6) the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers suggests you become familiar with the library you will be using by: taking a tour or enrolling for a brief introductory lecture referring to the library's publications describing its resources introducing yourself and your project to the reference librarian The MLA Handbook also lists guides for the use of libraries (5), including: Jean Key Gates, Guide to the Use of Libraries and Information Sources (7th ed., New York: McGraw, 1994). Thomas Mann, A Guide to Library Research Methods (New York: Oxford UP, 1987). Online Central Catalog Most libraries have their holdings listed on a computer. The online catalog may offer Internet sites, Web pages and databases that relate to the university's curriculum. It may also include academic journals and online reference books. Below are three search techniques commonly used online: Index Search: Although online catalogs may differ slightly from library to library, the most common listings are by: Subject Search: Enter the author's name for books and article written about the author. Author Search: Enter an author's name for works written by the author, including collections of essays the author may have written about his/her own works. Title Search: Enter a title for the screen to list all the books the library carries with that title. Key Word Search/Full-text Search: A one-word search, e.g., 'Kennedy,' will produce an overwhelming number of sources, as it will call up any entry that includes the name 'Kennedy.' To focus more narrowly on your subject, add one or more key words, e.g., "John Kennedy, Peace Corps." Use precise key words. Boolean Search: Boolean Search techniques use words such as "and," "or," and "not," which clarify the relationship between key words, thus narrowing the search. Take Efficient Notes Back to Top Keeping complete and accurate bibliography and note cards during the research process is a time (and sanity) saving practice. If you have ever needed a book or pages within a book, only to discover that an earlier researcher has failed to return it or torn pages from your source, you understand the need to take good notes. Every researcher has a favorite method for taking notes. Here are some suggestions-- customize one of them for your own use. Bibliography cards There may be far more books and articles listed than you have time to read, so be selective when choosing a reference. Take information from works that clearly relate to your thesis, remembering that you may not use them all. Use a smaller or a different color card from the one used for taking notes. Write a bibliography card for every source. Number the bibliography cards. On the note cards, use the number rather than the author's name and the title. It's faster. Another method for recording a working bibliography, of course, is to create your own database. Adding, removing, and alphabetizing titles is a simple process. Be sure to save often and to create a back-up file. A bibliography card should include all the information a reader needs to locate that particular source for further study. Most of the information required for a book entry (Gibaldi 112): Author's name Title of a part of the book [preface, chapter titles, etc.] Title of the book Name of the editor, translator, or compiler Edition used Number(s) of the volume(s) used Name of the series Place of publication, name of the publisher, and date of publication Page numbers Supplementary bibliographic information and annotations Most of the information required for an article in a periodical (Gibaldi 141): Author's name Title of the article Name of the periodical Series number or name (if relevant) Volume number (for a scholarly journal) Issue number (if needed) Date of publication Page numbers Supplementary information For information on how to cite other sources refer to your So you want to study history page . Note Cards Back to Top Take notes in ink on either uniform note cards (3x5, 4x6, etc.) or uniform slips of paper. Devote each note card to a single topic identified at the top. Write only on one side. Later, you may want to use the back to add notes or personal observations. Include a topical heading for each card. Include the number of the page(s) where you found the information. You will want the page number(s) later for documentation, and you may also want page number(s)to verify your notes. Most novice researchers write down too much. Condense. Abbreviate. You are striving for substance, not quantity. Quote directly from primary sources--but the "meat," not everything. Suggestions for condensing information: Summary: A summary is intended to provide the gist of an essay. Do not weave in the author's choice phrases. Read the information first and then condense the main points in your own words. This practice will help you avoid the copying that leads to plagiarism. Summarizing also helps you both analyze the text you are reading and evaluate its strengths and weaknesses (Barnet and Bedau 13). Outline: Use to identify a series of points. Paraphrase, except for key primary source quotations. Never quote directly from a secondary source, unless the precise wording is essential to your argument. Simplify the language and list the ideas in the same order. A paraphrase is as long as the original. Paraphrasing is helpful when you are struggling with a particularly difficult passage. Be sure to jot down your own insights or flashes of brilliance. Ralph Waldo Emerson warns you to "Look sharply after your thoughts. They come unlooked for, like a new bird seen on your trees, and, if you turn to your usual task, disappear...." To differentiate these insights from those of the source you are reading, initial them as your own. (When the following examples of note cards include the researcher's insights, they will be followed by the initials N. R.) When you have finished researching your thesis and you are ready to write your paper, organize your cards according to topic. Notecards make it easy to shuffle and organize your source information on a table-- or across the floor. Maintain your working outline that includes the note card headings and explores a logical order for presenting them in your paper. IV. Begin Thinking, Researching, Organizing Back to Top Don't be too sequential. Researching, writing, revising is a complex interactive process. Start writing as soon as possible! "The best antidote to writer's block is--to write." (Klauser 15). However, you still feel overwhelmed and are staring at a blank page, you are not alone. Many students find writing the first sentence to be the most daunting part of the entire research process. Be creative. Cluster (Rico 28-49). Clustering is a form of brainstorming. Sometimes called a web, the cluster forms a design that may suggest a natural organization for a paper. Here's a graphical depiction of brainstorming . Like a sun, the generating idea or topic lies at the center of the web. From it radiate words, phrases, sentences and images that in turn attract other words, phrases, sentences and images. Put another way--stay focused. Start with your outline. If clustering is not a technique that works for you, turn to the working outline you created during the research process. Use the outline view of your word processor. If you have not already done so, group your note cards according to topic headings. Compare them to your outline's major points. If necessary, change the outline to correspond with the headings on the note cards. If any area seems weak because of a scarcity of facts or opinions, return to your primary and/or secondary sources for more information or consider deleting that heading. Use your outline to provide balance in your essay. Each major topic should have approximately the same amount of information. Once you have written a working outline, consider two different methods for organizing it. Deduction: A process of development that moves from the general to the specific. You may use this approach to present your findings. However, as noted above, your research and interpretive process should be inductive. Deduction is the most commonly used form of organization for a research paper. The thesis statement is the generalization that leads to the specific support provided by primary and secondary sources. The thesis is stated early in the paper. The body of the paper then proceeds to provide the facts, examples, and analogies that flow logically from that thesis. The thesis contains key words that are reflected in the outline. These key words become a unifying element throughout the paper, as they reappear in the detailed paragraphs that support and develop the thesis. The conclusion of the paper circles back to the thesis, which is now far more meaningful because of the deductive development that supports it. Chronological order A process that follows a traditional time line or sequence of events. A chronological organization is useful for a paper that explores cause and effect. Parenthetical Documentation Back to Top The Works Cited page, a list of primary and secondary sources, is not sufficient documentation to acknowledge the ideas, facts, and opinions you have included within your text. The MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers describes an efficient parenthetical style of documentation to be used within the body of your paper. Guidelines for parenthetical documentation: "References to the text must clearly point to specific sources in the list of works cited" (Gibaldi 184). Try to use parenthetical documentation as little as possible. For example, when you cite an entire work, it is preferable to include the author's name in the text. The author's last name followed by the page number is usually enough for an accurate identification of the source in the works cited list. These examples illustrate the most common kinds of documentation. Documenting a quotation: Ex. "The separation from the personal mother is a particularly intense process for a daughter because she has to separate from the one who is the same as herself" (Murdock 17). She may feel abandoned and angry. Note: The author of The Heroine's Journey is listed under Works Cited by the author's name, reversed--Murdock, Maureen. Quoted material is found on page 17 of that book. Parenthetical documentation is after the quotation mark and before the period. Documenting a paraphrase: Ex. In fairy tales a woman who holds the princess captive or who abandons her often needs to be killed (18). Note: The second paraphrase is also from Murdock's book The Heroine's Journey. It is not, however, necessary to repeat the author's name if no other documentation interrupts the two. If the works cited page lists more than one work by the same author, include within the parentheses an abbreviated form of the appropriate title. You may, of course, include the title in your sentence, making it unnecessary to add an abbreviated title in the citation. > Prepare a Works Cited Page Back to Top There are a variety of titles for the page that lists primary and secondary sources (Gibaldi 106-107). A Works Cited page lists those works you have cited within the body of your paper. The reader need only refer to it for the necessary information required for further independent research. Bibliography means literally a description of books. Because your research may involve the use of periodicals, films, art works, photographs, etc. "Works Cited" is a more precise descriptive term than bibliography. An Annotated Bibliography or Annotated Works Cited page offers brief critiques and descriptions of the works listed. A Works Consulted page lists those works you have used but not cited. Avoid using this format. As with other elements of a research paper there are specific guidelines for the placement and the appearance of the Works Cited page. The following guidelines comply with MLA style: The Work Cited page is placed at the end of your paper and numbered consecutively with the body of your paper. Center the title and place it one inch from the top of your page. Do not quote or underline the title. Double space the entire page, both within and between entries. The entries are arranged alphabetically by the author's last name or by the title of the article or book being cited. If the title begins with an article (a, an, the) alphabetize by the next word. If you cite two or more works by the same author, list the titles in alphabetical order. Begin every entry after the first with three hyphens followed by a period. All entries begin at the left margin but subsequent lines are indented five spaces. Be sure that each entry cited on the Works Cited page corresponds to a specific citation within your paper. Refer to the the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers (104- 182) for detailed descriptions of Work Cited entries. Citing sources from online databases is a relatively new phenomenon. Make sure to ask your professor about citing these sources and which style to use. V. Draft, Revise, Rewrite, Rethink Back to Top "There are days when the result is so bad that no fewer than five revisions are required. In contrast, when I'm greatly inspired, only four revisions are needed." --John Kenneth Galbraith Try freewriting your first draft. Freewriting is a discovery process during which the writer freely explores a topic. Let your creative juices flow. In Writing without Teachers , Peter Elbow asserts that "[a]lmost everybody interposes a massive and complicated series of editings between the time words start to be born into consciousness and when they finally come off the end of the pencil or typewriter [or word processor] onto the page" (5). Do not let your internal judge interfere with this first draft. Creating and revising are two very different functions. Don't confuse them! If you stop to check spelling, punctuation, or grammar, you disrupt the flow of creative energy. Create; then fix it later. When material you have researched comes easily to mind, include it. Add a quick citation, one you can come back to later to check for form, and get on with your discovery. In subsequent drafts, focus on creating an essay that flows smoothly, supports fully, and speaks clearly and interestingly. Add style to substance. Create a smooth flow of words, ideas and paragraphs. Rearrange paragraphs for a logical progression of information. Transition is essential if you want your reader to follow you smoothly from introduction to conclusion. Transitional words and phrases stitch your ideas together; they provide coherence within the essay. External transition: Words and phrases that are added to a sentence as overt signs of transition are obvious and effective, but should not be overused, as they may draw attention to themselves and away from ideas. Examples of external transition are "however," "then," "next," "therefore." "first," "moreover," and "on the other hand." Internal transition is more subtle. Key words in the introduction become golden threads when they appear in the paper's body and conclusion. When the writer hears a key word repeated too often, however, she/he replaces it with a synonym or a pronoun. Below are examples of internal transition. Transitional sentences create a logical flow from paragraph to paragraph. Iclude individual words, phrases, or clauses that refer to previous ideas and that point ahead to new ones. They are usually placed at the end or at the beginning of a paragraph. A transitional paragraph conducts your reader from one part of the paper to another. It may be only a few sentences long. Each paragraph of the body of the paper should contain adequate support for its one governing idea. Speak/write clearly, in your own voice. Tone: The paper's tone, whether formal, ironic, or humorous, should be appropriate for the audience and the subject. Voice: Keep you language honest. Your paper should sound like you. Understand, paraphrase, absorb, and express in your own words the information you have researched. Avoid phony language. Sentence formation: When you polish your sentences, read them aloud for word choice and word placement. Be concise. Strunk and White in The Elements of Style advise the writer to "omit needless words" (23). First, however, you must recognize them. Keep yourself and your reader interested. In fact, Strunk's 1918 writing advice is still well worth pondering. First, deliver on your promises. Be sure the body of your paper fulfills the promise of the introduction. Avoid the obvious. Offer new insights. Reveal the unexpected. Have you crafted your conclusion as carefully as you have your introduction? Conclusions are not merely the repetition of your thesis. The conclusion of a research paper is a synthesis of the information presented in the body. Your research has led you to conclusions and opinions that have helped you understand your thesis more deeply and more clearly. Lift your reader to the full level of understanding that you have achieved. Revision means "to look again." Find a peer reader to read your paper with you present. Or, visit your college or university's writing lab. Guide your reader's responses by asking specific questions. Are you unsure of the logical order of your paragraphs? Do you want to know whether you have supported all opinions adequately? Are you concerned about punctuation or grammar? Ask that these issues be addressed. You are in charge. Here are some techniques that may prove helpful when you are revising alone or with a reader. When you edit for spelling errors read the sentences backwards. This procedure will help you look closely at individual words. Always read your paper aloud. Hearing your own words puts them in a new light. Listen to the flow of ideas and of language. Decide whether or not the voice sounds honest and the tone is appropriate to the purpose of the paper and to your audience. Listen for awkward or lumpy wording. Find the one right word, Eliminate needless words. Combine sentences. Kill the passive voice. Eliminate was/were/is/are constructions. They're lame and anti-historical. Be ruthless. If an idea doesn't serve your thesis, banish it, even if it's one of your favorite bits of prose. In the margins, write the major topic of each paragraph. By outlining after you have written the paper, you are once again evaluating your paper's organization. OK, you've got the process down. Now execute! And enjoy! It's not everyday that you get to make history. VI. For Further Reading: Works Cited Back to Top Barnet, Sylvan, and Hugo Bedau. Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing: A Brief Guide to Argument. Boston: Bedford, 1993. Brent, Doug. Reading as Rhetorical Invention: Knowledge,Persuasion and the Teaching of Research-Based Writing. Urbana: NCTE, 1992. Elbow, Peter. Writing without Teachers. New York: Oxford University Press, 1973. Gibladi, Joseph. MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers. 4th ed. New York: Modern Language Association, 1995. Horvitz, Deborah. "Nameless Ghosts: Possession and Dispossession in Beloved." Studies in American Fiction , Vol. 17, No. 2, Autum, 1989, pp. 157-167. Republished in the Literature Research Center. Gale Group. (1 January 1999). Klauser, Henriette Anne. Writing on Both Sides of the Brain: Breakthrough Techniques for People Who Write. Philadelphia: Harper, 1986. Rico, Gabriele Lusser. Writing the Natural Way: Using Right Brain Techniques to Release Your Expressive Powers. Los Angeles: Houghton, 1983. Sorenson, Sharon. The Research Paper: A Contemporary Approach. New York: AMSCO, 1994. Strunk, William, Jr., and E. B. White. The Elements of Style. 3rd ed. New York: MacMillan, 1979. Back to Top This guide adapted from materials published by Thomson Gale, publishers. For free resources, including a generic guide to writing term papers, see the Gale.com website , which also includes product information for schools.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes .

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more variables . An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls. A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Step 1: ask a question.

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2: Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalise more complex constructs.

Step 3: Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

Step 4: Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

Step 5: Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if … then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

Step 6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

| Research question | Hypothesis | Null hypothesis |

|---|---|---|

| What are the health benefits of eating an apple a day? | Increasing apple consumption in over-60s will result in decreasing frequency of doctor’s visits. | Increasing apple consumption in over-60s will have no effect on frequency of doctor’s visits. |

| Which airlines have the most delays? | Low-cost airlines are more likely to have delays than premium airlines. | Low-cost and premium airlines are equally likely to have delays. |

| Can flexible work arrangements improve job satisfaction? | Employees who have flexible working hours will report greater job satisfaction than employees who work fixed hours. | There is no relationship between working hour flexibility and job satisfaction. |

| How effective is secondary school sex education at reducing teen pregnancies? | Teenagers who received sex education lessons throughout secondary school will have lower rates of unplanned pregnancy than teenagers who did not receive any sex education. | Secondary school sex education has no effect on teen pregnancy rates. |

| What effect does daily use of social media have on the attention span of under-16s? | There is a negative correlation between time spent on social media and attention span in under-16s. | There is no relationship between social media use and attention span in under-16s. |

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

A hypothesis is not just a guess. It should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (‘ x affects y because …’).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses. In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, May 06). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 15 October 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/hypothesis-writing/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, operationalisation | a guide with examples, pros & cons, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples.

- Thesis Action Plan New

- Academic Project Planner

Literature Navigator

Thesis dialogue blueprint, writing wizard's template, research proposal compass.

- See Success Stories

- Access Free Resources

- Why we are different

- All Products

- Coming Soon

What Makes a Good Hypothesis? Key Elements and Examples

A well-crafted hypothesis is the cornerstone of effective scientific research. It serves as a tentative explanation or prediction that guides the direction of study and experimental design. Understanding what makes a good hypothesis is essential for students, researchers, and anyone involved in scientific inquiry. This article delves into the key elements of a good hypothesis, its types, formulation steps, common pitfalls, and examples across various fields.

Key Takeaways

- A good hypothesis should be clear, precise, and testable, providing a focused direction for research.

- Distinguishing between a hypothesis and a research question is crucial for proper scientific investigation.

- Testability and falsifiability are fundamental characteristics of a robust hypothesis, ensuring it can be empirically examined.

- Formulating a hypothesis involves identifying variables, crafting if-then statements, and ensuring specificity and measurability.

- Avoiding common pitfalls such as ambiguity, overly broad statements, and double-barreled hypotheses enhances the quality and reliability of research.

Defining a Hypothesis: The Foundation of Scientific Inquiry

A hypothesis is a tentative, declarative statement about the relationship between two or more variables that can be observed empirically. It serves as a scientific guess about these relationships, grounded in intuition, theories, or relevant facts from previous observations, research, or experience. Hypotheses offer explanations for certain phenomena and guide the collection and analysis of research data. Implicit in hypothesis formulation is the notion that these statements must be tested, guiding the discovery of new knowledge.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

A well-crafted hypothesis is essential for any scientific inquiry. It serves as a foundation for your research and guides your experimental design. Here are the key characteristics that define a good hypothesis:

Types of Hypotheses in Research

Understanding the different types of hypotheses is crucial for targeted research . Each type serves a unique purpose and is formulated based on the specific research question at hand.

Steps to Formulate a Strong Hypothesis

Formulating a strong hypothesis is a critical step in the research process. It involves several key stages that ensure your hypothesis is clear, testable, and grounded in existing knowledge. Here are the essential steps to follow:

Identifying Variables and Relationships

Begin by identifying the key variables in your study. These include the independent variable, which you will manipulate, and the dependent variable, which you will measure. Understanding the relationship between these variables is crucial. Research always starts with a question , but one that takes into account what is already known.

Crafting If-Then Statements

A well-formulated hypothesis often takes the form of an if-then statement. This structure clearly defines the expected relationship between the variables. For example, "If the amount of sunlight increases, then the growth rate of the plant will increase." This format helps in making your hypothesis specific and testable.

Ensuring Measurability and Specificity

Your hypothesis should be specific enough to be measurable. Avoid vague terms and ensure that the variables can be quantified. This specificity enhances the testability of your hypothesis, making it easier to design experiments and analyze data. Clear, testable, and grounded hypotheses enhance research credibility and reliability.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid When Writing Hypotheses

Avoiding ambiguity and vagueness.

A hypothesis should be clear and specific. Ambiguity can lead to confusion and misinterpretation, which can undermine the entire research process. Ensure your hypothesis is straightforward and leaves no room for multiple interpretations. This clarity is crucial for demystifying research and understanding the difference between a problem and a hypothesis .

Steering Clear of Double-Barreled Hypotheses

A double-barreled hypothesis addresses two issues simultaneously, which can complicate the testing process. Instead, focus on one relationship or variable at a time. This approach not only simplifies your research but also enhances the precision of your findings.

Ensuring Hypotheses are Not Overly Broad

An overly broad hypothesis can be difficult to test and may lack the specificity needed for meaningful results. Narrow down your hypothesis to a manageable scope. This focus is essential for effective study design and impactful contributions to knowledge. By doing so, you can better apply key stats in experimental research, emphasizing hypothesis testing, significance, and practical implications in drawing conclusions from data .

Examples of Effective Hypotheses

Hypotheses in natural sciences.

In the natural sciences, hypotheses often predict relationships between variables in a clear and testable manner. For instance, a hypothesis might state, " Plants grow better with bottled water than tap water ." This hypothesis is specific and can be tested through controlled experiments, making it a strong example of an effective hypothesis.

Hypotheses in Social Sciences

Social science hypotheses frequently address human behavior and societal trends. An example could be, "Reducing prices will make customers happy." This hypothesis is grounded in existing knowledge about consumer behavior and can be tested through surveys or market analysis.

Hypotheses in Applied Research

Applied research hypotheses are designed to solve practical problems. For example, "Fixing the hard-to-use comment form will increase user engagement" is a hypothesis that is both relevant and specific to a particular issue. It can be tested by implementing changes and observing the outcomes, ensuring that the hypothesis is both observable and testable.

Testing and Refining Hypotheses

Designing experiments to test hypotheses.

To effectively test your hypothesis, you must design a robust experiment. This involves identifying the independent and dependent variables and ensuring that you have control over the independent variable. A well-designed experiment will allow you to isolate the effects of the independent variable on the dependent variable, thereby providing clear insights into the validity of your hypothesis. Remember, the essential function of the hypothesis in scientific inquiry is to guide the collection of research data and the subsequent discovery of new knowledge.

Analyzing Data and Drawing Conclusions

Once your experiment is complete, the next step is to analyze the collected data. This involves statistical analysis to determine whether the results support or refute your hypothesis. Pay close attention to statistical significance and p-values , as these will help you understand the reliability of your findings. If your data contradicts your hypothesis, consider revisiting your research design and evaluating alternative explanations.

Revising Hypotheses Based on Findings

Scientific inquiry is an iterative process. If your initial hypothesis is not supported by the data, don't be discouraged. Instead, refine your hypothesis based on the new insights gained from your experiment. This may involve adjusting your variables, refining your research question, or implementing additional controls. By continuously refining your hypothesis, you contribute to the advancement of knowledge and improve the robustness of your research.

Testing and refining hypotheses is a crucial step in any research journey. It allows you to validate your ideas and ensure that your thesis stands on solid ground. If you're struggling with this process, our step-by-step Thesis Action Plan can guide you through each stage, making it easier and more manageable. Don't let uncertainty hold you back. Visit our website to learn more and claim your special offer now !

In conclusion, a well-crafted hypothesis is the cornerstone of any scientific inquiry. It serves as a guiding framework that directs the research process, ensuring that the study remains focused and relevant. The key elements of a good hypothesis include clarity, testability, and a clear cause-and-effect relationship. By adhering to these principles, researchers can formulate hypotheses that are not only robust but also capable of withstanding rigorous scientific scrutiny. As demonstrated through various examples, a good hypothesis not only predicts an outcome but also provides a clear pathway for testing and validation. Therefore, mastering the art of hypothesis formulation is essential for any researcher aiming to contribute meaningful and impactful findings to their field.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a hypothesis in scientific research.

A hypothesis is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon, serving as a starting point for further investigation. It is a statement that can be tested through experiments and observations.

How does a hypothesis differ from a research question?

A hypothesis is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in your study. A research question, on the other hand, is a broad question that guides your research but does not predict the outcome.

What are the key characteristics of a good hypothesis?

A good hypothesis should be clear and precise, testable and falsifiable, and grounded in existing knowledge. It should also include variables that can be measured and analyzed.

What are null and alternative hypotheses?

The null hypothesis states that there is no effect or no relationship between variables, while the alternative hypothesis states that there is an effect or a relationship. These hypotheses are tested to determine which one is supported by the data.

Why is it important for a hypothesis to be testable and falsifiable?

A hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable to allow for empirical investigation. This means that it should be possible to design an experiment that can either support or refute the hypothesis.

Can you provide an example of a good hypothesis in social sciences?

Sure! An example of a good hypothesis in social sciences could be: "If students participate in group study sessions, then their academic performance will improve compared to those who study alone." This hypothesis is specific, testable, and based on existing knowledge.

Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics: A Fun and Informative Guide

Unlocking the Power of Data: A Review of 'Essentials of Modern Business Statistics with Microsoft Excel'

Discovering Statistics Using SAS: A Comprehensive Review

How to Type Your Thesis Fast Without Compromising Quality

Looking for the Perfect Thesis Literature Review Sample? Here’s What You Should Know

Explanatory vs. Argumentative Thesis: Which Style Fits Your Paper Best?

Thesis Action Plan

- Rebels Blog

- Blog Articles

- Affiliate Program

- Terms and Conditions

- Payment and Shipping Terms

- Privacy Policy

- Return Policy

© 2024 Research Rebels, All rights reserved.

Your cart is currently empty.

Thesis Statements

What is a thesis statement.

Your thesis statement is one of the most important parts of your paper. It expresses your main argument succinctly and explains why your argument is historically significant. Think of your thesis as a promise you make to your reader about what your paper will argue. Then, spend the rest of your paper–each body paragraph–fulfilling that promise.

Your thesis should be between one and three sentences long and is placed at the end of your introduction. Just because the thesis comes towards the beginning of your paper does not mean you can write it first and then forget about it. View your thesis as a work in progress while you write your paper. Once you are satisfied with the overall argument your paper makes, go back to your thesis and see if it captures what you have argued. If it does not, then revise it. Crafting a good thesis is one of the most challenging parts of the writing process, so do not expect to perfect it on the first few tries. Successful writers revise their thesis statements again and again.

A successful thesis statement:

- makes an historical argument

- takes a position that requires defending

- is historically specific

- is focused and precise

- answers the question, “so what?”

How to write a thesis statement:

Suppose you are taking an early American history class and your professor has distributed the following essay prompt:

“Historians have debated the American Revolution’s effect on women. Some argue that the Revolution had a positive effect because it increased women’s authority in the family. Others argue that it had a negative effect because it excluded women from politics. Still others argue that the Revolution changed very little for women, as they remained ensconced in the home. Write a paper in which you pose your own answer to the question of whether the American Revolution had a positive, negative, or limited effect on women.”

Using this prompt, we will look at both weak and strong thesis statements to see how successful thesis statements work.

While this thesis does take a position, it is problematic because it simply restates the prompt. It needs to be more specific about how the Revolution had a limited effect on women and why it mattered that women remained in the home.

Revised Thesis: The Revolution wrought little political change in the lives of women because they did not gain the right to vote or run for office. Instead, women remained firmly in the home, just as they had before the war, making their day-to-day lives look much the same.

This revision is an improvement over the first attempt because it states what standards the writer is using to measure change (the right to vote and run for office) and it shows why women remaining in the home serves as evidence of limited change (because their day-to-day lives looked the same before and after the war). However, it still relies too heavily on the information given in the prompt, simply saying that women remained in the home. It needs to make an argument about some element of the war’s limited effect on women. This thesis requires further revision.

Strong Thesis: While the Revolution presented women unprecedented opportunities to participate in protest movements and manage their family’s farms and businesses, it ultimately did not offer lasting political change, excluding women from the right to vote and serve in office.

Few would argue with the idea that war brings upheaval. Your thesis needs to be debatable: it needs to make a claim against which someone could argue. Your job throughout the paper is to provide evidence in support of your own case. Here is a revised version:

Strong Thesis: The Revolution caused particular upheaval in the lives of women. With men away at war, women took on full responsibility for running households, farms, and businesses. As a result of their increased involvement during the war, many women were reluctant to give up their new-found responsibilities after the fighting ended.

Sexism is a vague word that can mean different things in different times and places. In order to answer the question and make a compelling argument, this thesis needs to explain exactly what attitudes toward women were in early America, and how those attitudes negatively affected women in the Revolutionary period.

Strong Thesis: The Revolution had a negative impact on women because of the belief that women lacked the rational faculties of men. In a nation that was to be guided by reasonable republican citizens, women were imagined to have no place in politics and were thus firmly relegated to the home.

This thesis addresses too large of a topic for an undergraduate paper. The terms “social,” “political,” and “economic” are too broad and vague for the writer to analyze them thoroughly in a limited number of pages. The thesis might focus on one of those concepts, or it might narrow the emphasis to some specific features of social, political, and economic change.

Strong Thesis: The Revolution paved the way for important political changes for women. As “Republican Mothers,” women contributed to the polity by raising future citizens and nurturing virtuous husbands. Consequently, women played a far more important role in the new nation’s politics than they had under British rule.

This thesis is off to a strong start, but it needs to go one step further by telling the reader why changes in these three areas mattered. How did the lives of women improve because of developments in education, law, and economics? What were women able to do with these advantages? Obviously the rest of the paper will answer these questions, but the thesis statement needs to give some indication of why these particular changes mattered.

Strong Thesis: The Revolution had a positive impact on women because it ushered in improvements in female education, legal standing, and economic opportunity. Progress in these three areas gave women the tools they needed to carve out lives beyond the home, laying the foundation for the cohesive feminist movement that would emerge in the mid-nineteenth century.

Thesis Checklist

When revising your thesis, check it against the following guidelines:

- Does my thesis make an historical argument?

- Does my thesis take a position that requires defending?

- Is my thesis historically specific?

- Is my thesis focused and precise?

- Does my thesis answer the question, “so what?”

Download as PDF

6265 Bunche Hall Box 951473 University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA 90095-1473 Phone: (310) 825-4601

Other Resources

- UCLA Library

- Faculty Intranet

- Department Forms

- Office 365 Email

- Remote Help

Campus Resources

- Maps, Directions, Parking

- Academic Calendar

- University of California

- Terms of Use

Social Sciences Division Departments

- Aerospace Studies

- African American Studies

- American Indian Studies

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Asian American Studies

- César E. Chávez Department of Chicana & Chicano Studies

- Communication

- Conservation

- Gender Studies

- Military Science

- Naval Science

- Political Science

Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

How to create a hypothesis for a historical research? [closed]

When writing a dissertation or a thesis about history, students and researchers are asked to state a problem and a hypothesis for that problem. My question is how to state a problem and a hypothesis for a historical event where we all know that history never changes and that it is restricted to already given facts? Supposing that someone is writing a thesis about the Battle of Waterloo ...All the info about the Battle of Waterloo are the same everywhere, what can this researcher add?? Nothing actually, he/she is going to end up summarizing a dozen of books about it without bringing anything new to the topic (not because he/she cannot but because it's history). What kind of problem statement that one can write about a Battle, a king, a conflict, ... I mean how can someone see problems in history and give hypotheses for them?? Please illustrate if you can

- research-process

- methodology

- 3 Why was German unification a peaceful process and not a violent revolution cum annexation? Can you answer this by just stating the facts? Which facts would you consider relevant? How would you ascertain their truthfulness? – henning no longer feeds AI Commented Apr 8, 2019 at 17:26

- According to u, how a question like yours could be answered? Thnx! – Maria_mimi Commented Apr 8, 2019 at 17:36

- 1 This seems to be a discussion to have with your advisor. – Solar Mike Commented Apr 8, 2019 at 19:31

This sounds like trying to force a restricted view of the scientific method to research in history. One learns during many years of studying history how research in history is performed, what is expected, what constitutes verification and evidence, just as one learns during many years of studying mathematics how research in mathematics is performed, what constitutes proof, the accepted standards of rigor, etc. And similar things can be said about Physics, Computer Engineering, Linguistics, Philosophy, Comparative Literature, Botany, Aerospace Engineering, Archaeology, etc.

Here's one way to at least superficially research your question without going through years of study in history. First, search for "Battle of Waterloo" (without quotes) in the title field at the ProQuest search page. Then google the titles of some of the (over 40) results to see whether freely available copies can be found. Then, for the theses you are able to get copies of, look over the abstract and/or introduction and/or summary, using the table of contents to locate these if you can't immediately find them.

When I did this, the 7th listed item was Waterloo in Myth and Memory: The Battles of Waterloo 1815-1915 (2013), and its abstract begins with the following:

This work examines memory of the Battle of Waterloo. There have been hundreds of works on the Battle of Waterloo but what this work does is to examine how works in several genres change over time. The memory of Waterloo was not static but changed several times over and over again. The myth of Waterloo was created, challenged and renegotiated several times.

- Thnx a million! – Maria_mimi Commented Apr 9, 2019 at 6:29

Not the answer you're looking for? Browse other questions tagged research-process thesis methodology history .

- Featured on Meta

- Upcoming initiatives on Stack Overflow and across the Stack Exchange network...

- Preventing unauthorized automated access to the network

Hot Network Questions

- "Riiiight," he said. What synonym of said can be used here?

- How to cover up a kitchen pass-through window without permanent changes?

- Compressing by a projection and applying a positive linear functional

- Offering shelter to homeless employees

- Why is pqxdh of Signal is not secure against active adversaries while PQ3 of iMessage is?

- Why aren't activation functions variable as well instead of being fixed?

- Horror / Thriller film with a mother and her baby surviving after a virus has turned people into zombie-like killers

- Will I have enough time to connect between Paris Gare du Nord and Gare de l’Est accounting for any passport control?

- What was Adam Smith's position on the American Revolution?

- How to check die temperatures on an Apple silicon Mac?

- How good is Quicken Spell as a feat?

- Can we choose to believe our beliefs, for example, can we simply choose to believe in God?

- A grid of Primes

- What type of radiation on Io (moon)

- Why/how am I over counting here?

- How can patients afford expensive surgeries but not lawsuits in the U.S. medical system in "Dr. Death"?

- Why the title The Silver Chair?

- What expressions (verbs) are used for the actions of adding ingredients (solid, fluid, powdery) into a container, specifically while cooking?

- Is my sauerkraut fermenting safely?

- Reference on why finding a feasible solution to the Set Partitioning problem is NP-Hard?

- How should I handle students who are very disengaged in class?

- Are these trill instructions correct?

- How can I seal the joint between my wall tile and bathroom countertop?

- How did Vladimir Arnold explain the difference in approaches between mathematicians and physicists?

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

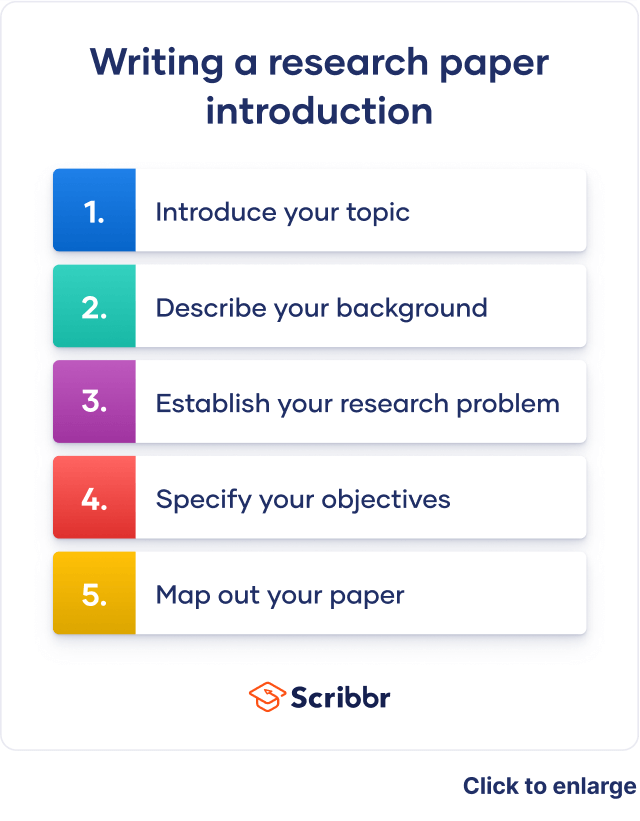

Writing a Research Paper Introduction | Step-by-Step Guide

Published on September 24, 2022 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on September 5, 2024.

The introduction to a research paper is where you set up your topic and approach for the reader. It has several key goals:

- Present your topic and get the reader interested

- Provide background or summarize existing research

- Position your own approach

- Detail your specific research problem and problem statement

- Give an overview of the paper’s structure

The introduction looks slightly different depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or constructs an argument by engaging with a variety of sources.

The five steps in this article will help you put together an effective introduction for either type of research paper.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: introduce your topic, step 2: describe the background, step 3: establish your research problem, step 4: specify your objective(s), step 5: map out your paper, research paper introduction examples, frequently asked questions about the research paper introduction.

The first job of the introduction is to tell the reader what your topic is and why it’s interesting or important. This is generally accomplished with a strong opening hook.

The hook is a striking opening sentence that clearly conveys the relevance of your topic. Think of an interesting fact or statistic, a strong statement, a question, or a brief anecdote that will get the reader wondering about your topic.

For example, the following could be an effective hook for an argumentative paper about the environmental impact of cattle farming:

A more empirical paper investigating the relationship of Instagram use with body image issues in adolescent girls might use the following hook:

Don’t feel that your hook necessarily has to be deeply impressive or creative. Clarity and relevance are still more important than catchiness. The key thing is to guide the reader into your topic and situate your ideas.

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

This part of the introduction differs depending on what approach your paper is taking.

In a more argumentative paper, you’ll explore some general background here. In a more empirical paper, this is the place to review previous research and establish how yours fits in.

Argumentative paper: Background information

After you’ve caught your reader’s attention, specify a bit more, providing context and narrowing down your topic.

Provide only the most relevant background information. The introduction isn’t the place to get too in-depth; if more background is essential to your paper, it can appear in the body .

Empirical paper: Describing previous research

For a paper describing original research, you’ll instead provide an overview of the most relevant research that has already been conducted. This is a sort of miniature literature review —a sketch of the current state of research into your topic, boiled down to a few sentences.

This should be informed by genuine engagement with the literature. Your search can be less extensive than in a full literature review, but a clear sense of the relevant research is crucial to inform your own work.

Begin by establishing the kinds of research that have been done, and end with limitations or gaps in the research that you intend to respond to.

The next step is to clarify how your own research fits in and what problem it addresses.

Argumentative paper: Emphasize importance

In an argumentative research paper, you can simply state the problem you intend to discuss, and what is original or important about your argument.

Empirical paper: Relate to the literature

In an empirical research paper, try to lead into the problem on the basis of your discussion of the literature. Think in terms of these questions:

- What research gap is your work intended to fill?

- What limitations in previous work does it address?

- What contribution to knowledge does it make?

You can make the connection between your problem and the existing research using phrases like the following.

| Although has been studied in detail, insufficient attention has been paid to . | You will address a previously overlooked aspect of your topic. |

| The implications of study deserve to be explored further. | You will build on something suggested by a previous study, exploring it in greater depth. |

| It is generally assumed that . However, this paper suggests that … | You will depart from the consensus on your topic, establishing a new position. |

Now you’ll get into the specifics of what you intend to find out or express in your research paper.

The way you frame your research objectives varies. An argumentative paper presents a thesis statement, while an empirical paper generally poses a research question (sometimes with a hypothesis as to the answer).

Argumentative paper: Thesis statement

The thesis statement expresses the position that the rest of the paper will present evidence and arguments for. It can be presented in one or two sentences, and should state your position clearly and directly, without providing specific arguments for it at this point.

Empirical paper: Research question and hypothesis

The research question is the question you want to answer in an empirical research paper.

Present your research question clearly and directly, with a minimum of discussion at this point. The rest of the paper will be taken up with discussing and investigating this question; here you just need to express it.

A research question can be framed either directly or indirectly.

- This study set out to answer the following question: What effects does daily use of Instagram have on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls?

- We investigated the effects of daily Instagram use on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls.

If your research involved testing hypotheses , these should be stated along with your research question. They are usually presented in the past tense, since the hypothesis will already have been tested by the time you are writing up your paper.

For example, the following hypothesis might respond to the research question above:

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

The final part of the introduction is often dedicated to a brief overview of the rest of the paper.

In a paper structured using the standard scientific “introduction, methods, results, discussion” format, this isn’t always necessary. But if your paper is structured in a less predictable way, it’s important to describe the shape of it for the reader.

If included, the overview should be concise, direct, and written in the present tense.

- This paper will first discuss several examples of survey-based research into adolescent social media use, then will go on to …

- This paper first discusses several examples of survey-based research into adolescent social media use, then goes on to …

Scribbr’s paraphrasing tool can help you rephrase sentences to give a clear overview of your arguments.

Full examples of research paper introductions are shown in the tabs below: one for an argumentative paper, the other for an empirical paper.

- Argumentative paper

- Empirical paper

Are cows responsible for climate change? A recent study (RIVM, 2019) shows that cattle farmers account for two thirds of agricultural nitrogen emissions in the Netherlands. These emissions result from nitrogen in manure, which can degrade into ammonia and enter the atmosphere. The study’s calculations show that agriculture is the main source of nitrogen pollution, accounting for 46% of the country’s total emissions. By comparison, road traffic and households are responsible for 6.1% each, the industrial sector for 1%. While efforts are being made to mitigate these emissions, policymakers are reluctant to reckon with the scale of the problem. The approach presented here is a radical one, but commensurate with the issue. This paper argues that the Dutch government must stimulate and subsidize livestock farmers, especially cattle farmers, to transition to sustainable vegetable farming. It first establishes the inadequacy of current mitigation measures, then discusses the various advantages of the results proposed, and finally addresses potential objections to the plan on economic grounds.

The rise of social media has been accompanied by a sharp increase in the prevalence of body image issues among women and girls. This correlation has received significant academic attention: Various empirical studies have been conducted into Facebook usage among adolescent girls (Tiggermann & Slater, 2013; Meier & Gray, 2014). These studies have consistently found that the visual and interactive aspects of the platform have the greatest influence on body image issues. Despite this, highly visual social media (HVSM) such as Instagram have yet to be robustly researched. This paper sets out to address this research gap. We investigated the effects of daily Instagram use on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls. It was hypothesized that daily Instagram use would be associated with an increase in body image concerns and a decrease in self-esteem ratings.

The introduction of a research paper includes several key elements:

- A hook to catch the reader’s interest

- Relevant background on the topic

- Details of your research problem

and your problem statement

- A thesis statement or research question

- Sometimes an overview of the paper

Don’t feel that you have to write the introduction first. The introduction is often one of the last parts of the research paper you’ll write, along with the conclusion.

This is because it can be easier to introduce your paper once you’ve already written the body ; you may not have the clearest idea of your arguments until you’ve written them, and things can change during the writing process .

The way you present your research problem in your introduction varies depending on the nature of your research paper . A research paper that presents a sustained argument will usually encapsulate this argument in a thesis statement .

A research paper designed to present the results of empirical research tends to present a research question that it seeks to answer. It may also include a hypothesis —a prediction that will be confirmed or disproved by your research.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2024, September 05). Writing a Research Paper Introduction | Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved October 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-paper/research-paper-introduction/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, writing a research paper conclusion | step-by-step guide, research paper format | apa, mla, & chicago templates, what is your plagiarism score.

- Researching

- 1. Key Question

How to write a key inquiry question

At the beginning of the research process , you need to be clear about what you are trying to discover as a result of your research.

To create a focus to drive your research, you are required to create a Key Inquiry Question.

What is a 'key inquiry question'?

A Key Inquiry Question is the question that your research is aiming to answer.

A key inquiry question is a question that helps guide historical research by focusing the investigation on a particular aspect of a historical event, trend, or development.

A good key inquiry question should be specific, open-ended, and focused on a historical issue or problem.

By reducing your focus down to a single Key Inquiry Question, it will help you to avoid wasting time on needless research, but also help you tell if your research has ultimately been successful.

At the end of the research process , you will write a one-sentence answer to your Key Inquiry Question, which will become your hypothesis .

How do you create a key inquiry question?

Great inquiry questions must abide by the following rules:

1. Start with an interrogative

An interrogative is a question word. Here are some common interrogatives with which you can start a key inquiry question:

| Interrogative | Explanation |

| How | Explain the process, steps or key events |

| To what extent | Quantify the importance (to a great extent? to a limited extent?) |

| Why | Explain the , reasons or |

2. Do not make it a 'closed question'

Closed questions are ones that can be answered with a single word (e.g., yes, no, Churchill, 1943, etc.).

Most 'closed questions' start with the interrogatives 'does', 'did', 'was' or 'are'.

A great key question starts with either 'what', 'why', or 'how'.

3. Base it on a historical knowledge skill

Make your question focus on one of the historical knowledge skills in history.

Here is a list of the most common historical knowledge skills:

| Historical Knowledge Skill | Explanation |

| What things led to or the historical event? | |

| What was different as a of this event or person? | |

| What happened as a of the historical event or person | |

| How have people interpreted this event or person differently over time? | |

| What , or ? | |

| The for their actions | |

| Why is it important? |

4. Be extremely specific

Limit your topic by mentioning specific historical information, including people, times, places or concepts.