Welcome to MozPortal

We have a curated list of the most noteworthy news from all across the globe. With MozPortal you get access to Exclusive articles that let you stay ahead of the curve.

- South Africa

- United State

History Grade 10 - Topic 6 Essay Questions and Answers

Impact of the 1913 Land Act

Based on the 2012 Grade 10 NSC Exemplar Paper:

Grade 10 Past Exam Paper

Grade 10 Source Addendum

Grade 10 Past Exam Memo

The Land Act of 1913 was the final nail in the coffin for Black South Africans in the 20th century and a step to Apartheid. Discuss this statement with reference to the social and economic impact of the Land Act and how it laid the foundation for the system of Apartheid. [1]

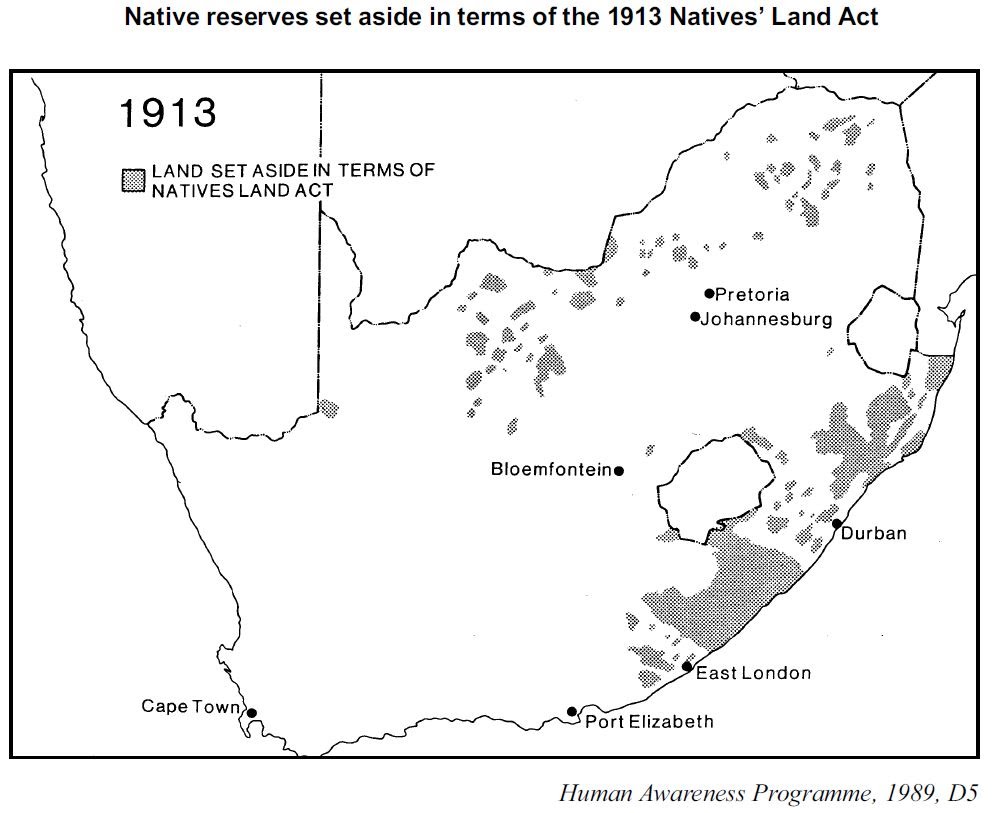

Sol Plaatje, a member of the SANNC and an activist against the implementation of the 1913 Natives Land Act wrote in his book, Native Life in South Africa, concerning the Act that: “Africans were born as pariahs in the land of their birth”. [2] The 1913 Land Act stipulated that Africans were restricted to own 7% of the land in South Africa, while the remaining 93% of the land were allocated to white settlers. [3] The impact of this new law was far-reaching since it impoverished African communities, while enforcing racial segregation. The following essay will discuss the economic and social impact of the Natives Land Act and how it laid the foundation for the system of Apartheid.

Firstly, the Natives Land Act impoverished black South Africans, since they were not given enough land to become independent farmers. [4] The land allocated to them were also overused and infertile which lessened their agricultural production and their income. According to the law, Africans were also not allowed to rent land allocated to white settlers, which forced them to live in overpopulated and impoverished reserves. [5] Since Africans were not allowed to rent land, sharecropping also became illegal. Sharecropping refers to the practice where various farmers, regardless of race, could sow on the same land and split the profit. Under the Natives Land Act this practice was declared illegal and previous sharecroppers were destitute and impoverished without a source of income. [6] This forced many Africans to become cheap labour tentants or farm labourers, since they could not farm independently on the land allocated to them. Other Africans were forced into the mining industry and were given minimum wages. [7] Ultimately, the Native Land Act impoverished Africans, since they were left destitute without their land, roaming around without enough fertile soil to feed their cattle or themselves. This forced Africans to sell their livestock to survive or kill the livestock for meat while becoming cheap labour as labour tenants or miners. [8]

Secondly, the Natives Land Act had a vast social impact on Africans. The Act promoted the racial ideology that white settlers were superior to Africans and therefore the races had to be divided by law. [9] This enabled the Union of South Africa to pass legislation that gave 93% of the country, with its rich resources, to the white population, while forcing Africans into servitude. After this legislation was accepted, Africans were evicted from their land and were forced to wander around with their cattle and possessions in extremely hot and cold weather. [10] Those who pitied destitute Africans were also forbidden by law to give them a place to stay, since they would be fined 100 pounds or be imprisoned. [11] This forced Africans to live in overpopulated and infertile areas, where they were malnourished and sick. [12] Africans hardly had enough food to feed themselves and therefore it was no surprise that they were often forced to kill their livestock or sell them before they died of hunger. [13]

After the implementation of the Natives Land Act, the SANNC was established in 1913 to fight against the new law and to promote racial equality. [14] Members of the SANNC, which included Sol Plaatje, sent a delegation to Prime Minister, Louis Botha in 1914 which showed the impact of the Natives Land Act. This delegation failed, which resulted in the SANNC travelling abroad to Britain to ask for them to intervene [15] . However, since the delegation occurred at the start of the First World War, Britain did not want to lose the support of the white settlers in South Africa. After the South African War, Britain’s relationship with the Afrikaners were still fragile and they did not want to lose their support by intervening with their new racist policies. This led to Sol Plaatje writing his book, Native Life in South Africa, which documents the delegations sent to Louis Botha and to Britain, while portraying how Africans became “pariahs” in the land of their birth. [16]

While the SANNC actively fought against the Natives Land Act, they could not overturn it. The Natives Land Act became the precursor to Apartheid, since it led to the establishment of various other laws, such as the Urban Areas Act (1923), the Natives and Land Trust Act (1936), The Group Areas Act (1950) and the Natives Act (1952). These laws controlled the movement of employed Africans into the cities (Urban Areas Act) [17] , while illegalizing ownership of land by Africans that are allocated to white settlers (Native Land Act, Land Trust Act, Group Areas Act) [18] and forced Africans to wear passes (Natives Act). [19]

In conclusion, the Natives Land Act impoverished Africans and forced them into destitution based on their race. This then made the Act a precursor to further racist legislation that segregated black and white South Africans based on the racial hierarchy where the white man was viewed as superior to the black man. Africans became pariahs in their home country and while they tried to oppose the Natives Land Act, Britain refused to intervene, which enabled the Union of South Africa to continue issuing racist legislation.

Tips & Notes:

- Check out our Essay Writing Skills for more tips on writing essays.

- Remember, this is just an example essay. You still need to use the work provided by your teacher or learned in class.

- It is important to check in with your teacher and make sure this meets his/her requirements. For example, they might prefer that you do not use headings in your essay.

This article was originally produced for the SAHO classroom by Ilse Brookes, Amber Fox-Martin & Simone van der Colff

[1] The Department of Basic Education, “National Senior Certificate: Grade 10 History Marking Guideline 2017”, (Uploaded: November 2017), (Accessed: 28 October 2020), Available at: https://www.awsumnews.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/HISTORY-GR10-MEMO-NOV2017_English.pdf

[2] Sol Plaatje, Native Life in South Africa, 16.

[3] Author Unknown, “1913 Natives Land Act Centenary”, South African Government, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 13 September 2020), Available at: https://www.gov.za/1913-natives-land-act-centenary

[4] Author Unknown, “The Natives Land Act of 1913”, South African History Online, (Uploaded: 27 August 2019), (Accessed: 13 September 2020), Available at: https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/natives-land-act-1913

[6] Mtshiselwa, N., & Modise, L. “The Natives Land Act of 1913 engineered the poverty of Black South Africans: a historico-ecclesiastical perspective”, Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae, (Vol. 39), (2013).

[7] The Department of Basic Education, “National Senior Certificate: Grade 10 History Marking Guideline 2017”, (Uploaded: November 2017), (Accessed: 28 October 2020), Available at: https://www.awsumnews.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/HISTORY-GR10-MEMO-NOV2017_English.pdf

[9] Author Unknown, “The Homelands”, South African History Online, (Uploaded: 17 April 2011), (Accessed: 13 September 2020), Available at: https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/homelands

[10] The Department of Basic Education, “National Senior Certificate: Grade 10 History Marking Guideline 2017”, (Uploaded: November 2017), (Accessed: 28 October 2020), Available at: https://www.awsumnews.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/HISTORY-GR10-MEMO-NOV2017_English.pdf

[11] Ibid.

[12] The Department of Basic Education, “National Senior Certificate: Grade 10 History Marking Guideline 2017”, (Uploaded: November 2017), (Accessed: 28 October 2020), Available at: https://www.awsumnews.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/HISTORY-GR10-MEMO-NOV2017_English.pdf

[16] Sol Plaatje, Native Life in South Africa, 16.

[17] Author Unknown, “1923. Native Urban Areas Act (No.21), O’Malley: The Heart of Hope, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 20 September 2020) Available at: https://omalley.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/index.php/site/q/03lv01538/04lv01646/05lv01758.htm

[18] Author Unknown, “1936. Native Trust and Land Act No. 18”, O’Malley: The Heart of Hope, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 20 September 2020), Available at: https://omalley.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/index.php/site/q/03lv01538/04lv01646/05lv01784.htm

[19] Author Unknown, “Pass laws in South Africa, 1800 – 1994”, South African History Online, (Uploaded: 21 March 2011), (Accessed: 20 September 2020), Available at: https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/pass-laws-south-africa-1800-199

- Author Unknown, “Pass laws in South Africa, 1800 – 1994”, South African History Online, (Uploaded: 21 March 2011), (Accessed: 20 September 2020), Available at: https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/pass-laws-south-africa-1800-199

- Author Unknown, “1936. Native Trust and Land Act No. 18”, O’Malley: The Heart of Hope, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 20 September 2020), Available at: https://omalley.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/index.php/site/q/03lv01538/04lv01646/05lv01784.htm

- Author Unknown, “1923. Native Urban Areas Act (No.21), O’Malley: The Heart of Hope, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 20 September 2020) Available at: https://omalley.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/index.php/site/q/03lv01538/04lv01646/05lv01758.htm

- Author Unknown, “The Homelands”, South African History Online, (Uploaded: 17 April 2011), (Accessed: 13 September 2020), Available at: https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/homelands

- Author Unknown, “The Natives Land Act of 1913”, South African History Online, (Uploaded: 27 August 2019), (Accessed: 13 September 2020), Available at: https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/natives-land-act-1913

- Author Unknown, “1913 Natives Land Act Centenary”, South African Government, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 13 September 2020), Available at: https://www.gov.za/1913-natives-land-act-centenary

- Mtshiselwa, N., & Modise, L. “The Natives Land Act of 1913 engineered the poverty of Black South Africans: a historico-ecclesiastical perspective”, Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae, (Vol. 39), (2013).

- Plaatje, S., Native life in South Africa, Before and Since the European War and the Boer Rebellion, Fourth Edition, 1914, (Uploaded: 26 August 2019), (Accessed: 8 November 2020), Available at: https://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/native-life-south-africa-and-european-war-and-boer-rebellion-sol-t-plaatje

- The Department of Basic Education, “National Senior Certificate: Grade 10 History Marking Guideline 2017”, (Uploaded: November 2017), (Accessed: 28 October 2020), Available at: https://www.awsumnews.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/HISTORY-GR10-MEMO-NOV2017_English.pdf

Return to topic: The South African War and Union

Return to SAHO Home

Return to History Classroom

Collections in the Archives

Know something about this topic.

Towards a people's history

GetGoodEssay

Essay On Heritage Day in South Africa

Heritage Day, celebrated annually on September 24th in South Africa, holds great significance as a national holiday that promotes cultural diversity, unity, and the preservation of the country’s rich and varied heritage. Previously known as Shaka Day, it was officially renamed Heritage Day in 1996 to emphasize inclusivity and recognize the importance of various cultural backgrounds that make up the nation’s unique identity. This essay delves into the history and significance of Heritage Day, its impact on South African society, and the initiatives taken to preserve and celebrate the country’s heritage.

The History of Heritage Day

The roots of Heritage Day can be traced back to the commemoration of Shaka Day, which originally honored the legendary Zulu king, King Shaka Zulu. King Shaka was a prominent figure in Zulu history, known for his military prowess and leadership during the early 19th century. The day was initially celebrated primarily by Zulu communities in KwaZulu-Natal, the province where the Zulu Kingdom thrived.

However, with the dawning of democracy in 1994 and the end of apartheid, South Africa embarked on a journey of reconciliation and inclusivity. As part of this transformative process, the government decided to rename Shaka Day to Heritage Day to embrace all cultures and recognize the nation’s diverse heritage. The aim was to promote social cohesion, inclusivity, and respect for different cultural traditions and practices that exist within the country.

why do heritage day is celebrated in South Africa

Heritage Day is celebrated in South Africa on 24 September to recognize and celebrate the cultural diversity of the country. The day was first celebrated in 1996, after the end of apartheid, as a way to promote unity and reconciliation among South Africans of all backgrounds.

The date of 24 September was chosen because it is the anniversary of the death of King Shaka Zulu, a Zulu leader who is considered to be one of the most important figures in South African history. However, the day is now more broadly seen as a celebration of all the different cultures that make up South Africa, including the Zulu, Xhosa, Ndebele, Afrikaner, and British cultures.

On Heritage Day, South Africans celebrate their culture in a variety of ways. They may attend cultural events, such as festivals or performances, or they may simply spend time with family and friends sharing food, music, and stories from their heritage. The day is also a time to learn about the history and traditions of different cultures, and to appreciate the diversity of South Africa.

Heritage Day is an important day for South Africa because it helps to promote unity and understanding among its people. It is a day to celebrate the richness of South Africa’s cultural heritage, and to reaffirm the country’s commitment to diversity and equality.

Here are some of the ways that South Africans celebrate Heritage Day:

- Attending cultural events, such as festivals, performances, or traditional ceremonies.

- Visiting museums and historical sites.

- Learning about the history and traditions of different cultures.

- Sharing food, music, and stories from their own heritage with family and friends.

- Wearing traditional clothing.

- Participating in traditional dances or ceremonies.

- Volunteering at organizations that promote cultural heritage.

Heritage Day is a day for all South Africans to come together and celebrate their rich and diverse culture. It is a day to learn about each other’s heritage and to appreciate the unique qualities that make South Africa such a special country.

The Significance of Heritage Day

Heritage Day is more than just a public holiday; it is a symbol of unity and respect for South Africa’s rich cultural tapestry. In a country with eleven official languages and a multitude of ethnicities, religions, and traditions, Heritage Day plays a pivotal role in fostering national pride and social cohesion. It is a day that encourages South Africans to celebrate their unique identities while embracing their shared humanity.

One of the key elements of Heritage Day is the promotion of cultural exchange and understanding. Communities across the country come together to share their customs, music, dance, and cuisine, providing a platform for individuals to learn about and appreciate the diverse cultural heritage of their fellow citizens. By participating in these festivities, people can gain insight into the experiences and histories of others, bridging the gaps that may exist between different cultural groups.

Heritage Day and Cultural Preservation

In addition to fostering unity and understanding, Heritage Day serves as a reminder of the importance of preserving the nation’s heritage. South Africa boasts a plethora of traditional practices, languages, rituals, and historical landmarks that reflect the country’s rich history. Preserving this heritage is crucial not only for cultural reasons but also for the social and economic development of the nation.

One notable aspect of South Africa’s heritage is its indigenous knowledge systems. These systems, passed down through generations, hold valuable insights into sustainable practices, herbal medicine, and environmental conservation. By acknowledging and preserving indigenous knowledge, South Africa can tap into the wisdom of its ancestors and find solutions to modern challenges such as climate change and environmental degradation.

Moreover, the preservation of cultural heritage contributes to tourism and economic development. South Africa’s unique cultural offerings attract tourists from all over the world, providing an economic boost to local communities. Through the promotion of heritage sites , museums, and cultural festivals, Heritage Day plays a significant role in supporting the tourism industry and creating employment opportunities for locals.

Celebrating Heritage Day: Festivals and Activities

Heritage Day celebrations take various forms across the country, with communities organizing events that showcase their distinctive traditions and customs. Some of the most popular activities and festivals held on this day include:

1. Cultural Festivals: Various cultural festivals are organized, featuring traditional music, dance, and storytelling. These festivals provide a platform for artists and performers to showcase their talents and preserve their cultural heritage.

2. Braai Day: A prominent and widely enjoyed aspect of Heritage Day is the tradition of braai (barbecue). South Africans of all backgrounds come together to enjoy a delicious feast, reinforcing the spirit of unity and togetherness.

3. Heritage Walks and Tours: Guided walks and tours are organized in different cities, allowing people to explore historical landmarks, museums, and sites of cultural significance.

4. Traditional Attire: Many South Africans take pride in wearing traditional clothing on Heritage Day, showcasing their cultural identity with pride.

5. Indigenous Knowledge Exhibitions: Events that highlight indigenous knowledge systems and traditional practices are held to educate and raise awareness about the country’s diverse heritage.

6. Heritage Food and Craft Markets: Local artisans and food vendors set up markets to showcase traditional crafts and cuisine, providing an opportunity for economic empowerment for small businesses.

The Role of Education and Media

To ensure the continued significance of Heritage Day, education and media play a crucial role in raising awareness and promoting cultural understanding. Schools incorporate lessons on cultural heritage, history, and traditions, encouraging young generations to appreciate their heritage and respect the cultures of others.

Similarly, the media plays a vital role in shaping the narrative around Heritage Day. Television programs, radio shows, and newspaper articles can promote cultural diversity and foster a sense of national pride. By highlighting the unique aspects of different cultural groups and promoting positive interactions between communities, the media can contribute to a more cohesive and harmonious society.

Challenges and Future Prospects

While Heritage Day serves as a positive force in South African society, it also faces challenges that need to be addressed to maximize its impact. One major challenge is the lingering effects of apartheid, which created divisions and inequalities between different cultural groups. Overcoming these deep-rooted issues requires sustained efforts from the government, civil society, and individuals to promote reconciliation and understanding.

Another challenge is the risk of cultural commodification. As Heritage Day gains popularity, there is a danger of turning cultural practices into mere tourist attractions or commercial products. It is essential to strike a balance between celebrating heritage and respecting its sacredness and authenticity.

Moreover, as South Africa embraces modernization and globalization, there is a risk of losing some traditional practices and languages. Preserving these aspects of heritage requires proactive measures, such as revitalizing indigenous languages in schools and supporting initiatives to pass down traditional knowledge to younger generations.

In conclusion, Heritage Day in South Africa represents a powerful celebration of cultural diversity, unity, and national pride. Renamed from Shaka Day to Heritage Day in the spirit of inclusivity, this holiday has become an integral part of the country’s social fabric, promoting understanding and respect among diverse cultural groups. By celebrating and preserving its rich heritage, South Africa can move towards a more united and harmonious society.

Embracing Diversity: The Significance of Heritage Day in South Africa’s Cultural Landscape

Introduction: A Tapestry of Diversity

South Africa, a nation known for its rich cultural mosaic, celebrates Heritage Day as a testament to the profound significance of its diverse heritage. This essay delves into the cultural landscape of South Africa and explores the profound role of Heritage Day in fostering unity, understanding, and respect among its people while preserving the nation’s intricate tapestry of traditions.

Heritage Day: A Celebration of Unity in Diversity

Heritage Day, observed annually on September 24th, encapsulates the ethos of unity in diversity that defines South Africa. It invites citizens to celebrate their diverse cultural backgrounds, languages, beliefs, and traditions. The day serves as a reminder that while these elements may differ, they collectively contribute to the unique identity of the nation.

Preserving Traditions and Identity

Heritage Day stands as a cultural cornerstone, preserving and honoring the traditions that have been passed down through generations. From indigenous rituals to culinary practices, the celebration is a testament to the resilience of South Africa’s people in preserving their cultural identity even in the face of adversity.

Fostering Cultural Exchange and Understanding

At its core, Heritage Day encourages cultural exchange and understanding. It offers a platform for people from various backgrounds to engage in dialogue, learn about each other’s customs, and gain insights into the rich histories that shape the nation. This spirit of curiosity promotes tolerance, acceptance, and an appreciation for the nation’s collective history.

Acknowledging Historical Complexities

The celebration of Heritage Day is not devoid of the historical complexities that have shaped South Africa. It is a day to acknowledge the legacy of apartheid and colonialism, as well as the struggles and triumphs of the nation’s diverse communities. Heritage Day serves as a space for dialogue about the past and its impact on the present.

Celebrating the Rainbow Nation

The term “Rainbow Nation” was famously coined by Archbishop Desmond Tutu to describe South Africa’s diverse population. Heritage Day exemplifies this concept by highlighting the harmony that can arise from the coexistence of myriad cultures. The nation’s various ethnicities, languages, and traditions contribute to a vibrant social fabric that has come to define South Africa’s modern identity.

Cultural Expression and Creativity

Heritage Day provides a platform for creative expression as well. Art, music, dance, and literature become powerful tools to convey the rich narratives of different communities. Creative endeavors celebrate the beauty of cultural diversity, capturing the essence of South African heritage in various art forms.

Looking Ahead: The Legacy of Heritage Day

As South Africa looks to the future, the legacy of Heritage Day remains pivotal. It reinforces the importance of unity, tolerance, and mutual respect in a nation that has overcome immense challenges. The celebration is a call to build bridges, forge relationships, and embrace the uniqueness that each cultural group brings to the table.

Conclusion: A Vibrant Nation United by Heritage

Heritage Day embodies the spirit of unity in diversity that defines South Africa. It is a day of celebration, reflection, and connection, where citizens come together to honor their shared history and individual backgrounds. Through the celebration of Heritage Day, South Africa showcases to the world the power of embracing diversity and finding strength in the collective story of its people.

Heritage Day and the Celebration of Identity: Navigating the Intersection of Past and Present

Introduction: An Exploration of Identity

Heritage Day in South Africa offers a unique lens through which the nation’s past and present converge. This essay delves into the celebration’s significance as a moment of reflection, acknowledgment, and forward-looking celebration, showcasing how South Africans navigate the intricate intersection of their historical legacy and contemporary realities.

Heritage Day: A Journey Through Time

Heritage Day, observed annually on September 24th, encapsulates the essence of a nation’s identity journey. It invites South Africans to revisit their roots, rekindle connections with their heritage, and contemplate the stories that have shaped them. As individuals and communities engage in these reflections, they contribute to a collective narrative that weaves together the past and the present.

Honoring Ancestral Traditions

At the heart of Heritage Day is the honoring of ancestral traditions. Whether it’s through rituals, storytelling, or passing down traditional knowledge, South Africans use this day to remember their ancestors and the ways in which their wisdom and customs continue to influence contemporary life . Heritage Day thus serves as a bridge between generations, fostering a sense of continuity and connection.

A Platform for Cross-Cultural Dialogue

Heritage Day also acts as a platform for cross-cultural dialogue. In a nation as diverse as South Africa , individuals from different backgrounds have the opportunity to learn about one another’s traditions, languages, and histories. This exchange of knowledge and understanding nurtures social cohesion and contributes to a sense of national unity.

Reckoning with Historical Complexities

Celebrating identity through Heritage Day requires a nuanced reckoning with the historical complexities that have shaped South Africa’s trajectory. Acknowledging the scars of apartheid, colonialism, and injustices of the past is essential for building an inclusive future. Heritage Day becomes a space for dialogue about these issues, encouraging reflection on how historical legacies continue to affect present-day experiences.

Contemporary Expression of Heritage

While Heritage Day is steeped in history, it’s also a platform for the contemporary expression of heritage. The celebration encourages South Africans to infuse their unique cultural identities with modern interpretations, demonstrating that heritage is not stagnant but a living, evolving entity. This fusion of tradition and modernity showcases the adaptability and resilience of the nation’s diverse communities.

The Power of Unity in Diversity

Heritage Day reinforces the concept of unity in diversity, a core tenet of South Africa’s national identity. By embracing their own cultural backgrounds and appreciating those of others, citizens contribute to a sense of togetherness that transcends differences. This unity is a testament to the nation’s capacity to overcome historical divisions and emerge stronger as a collective entity.

Toward a Shared Future

As South Africa navigates the intersection of past and present, Heritage Day offers a glimpse into the shared future that its people are working to create. It serves as a reminder that while history shapes identity, it need not dictate the course of the nation. By celebrating heritage and fostering a sense of unity, South Africans lay the groundwork for a future that embraces diversity while forging common goals.

Conclusion: Celebrating the Intersection of Stories

Heritage Day is a celebration that encapsulates the intersection of South Africa’s diverse stories. It is a day to honor the past, acknowledge its complexities, and shape a future that builds on the nation’s cultural riches. By navigating this intersection, South Africans take part in a transformative journey that not only enriches their individual lives but also contributes to the vibrant tapestry of their collective identity.

- Recent Posts

- Essay on Criminological Theories in ‘8 Mile’ - September 21, 2023

- Essay on Employment Practices in South Africa: Sham Hiring for Compliance - September 21, 2023

- Essay on The Outsiders: Analysis of Three Deaths and Their Impact - September 21, 2023

2 thoughts on “Essay On Heritage Day in South Africa”

You didn’t write why is it celebrated

Thank you very much for highlighting such an important aspect. we have added this to essay. please have a look and do share your feedback.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

How to write an introduction for a history essay

Every essay needs to begin with an introductory paragraph. It needs to be the first paragraph the marker reads.

While your introduction paragraph might be the first of the paragraphs you write, this is not the only way to do it.

You can choose to write your introduction after you have written the rest of your essay.

This way, you will know what you have argued, and this might make writing the introduction easier.

Either approach is fine. If you do write your introduction first, ensure that you go back and refine it once you have completed your essay.

What is an ‘introduction paragraph’?

An introductory paragraph is a single paragraph at the start of your essay that prepares your reader for the argument you are going to make in your body paragraphs .

It should provide all of the necessary historical information about your topic and clearly state your argument so that by the end of the paragraph, the marker knows how you are going to structure the rest of your essay.

In general, you should never use quotes from sources in your introduction.

Introduction paragraph structure

While your introduction paragraph does not have to be as long as your body paragraphs , it does have a specific purpose, which you must fulfil.

A well-written introduction paragraph has the following four-part structure (summarised by the acronym BHES).

B – Background sentences

H – Hypothesis

E – Elaboration sentences

S - Signpost sentence

Each of these elements are explained in further detail, with examples, below:

1. Background sentences

The first two or three sentences of your introduction should provide a general introduction to the historical topic which your essay is about. This is done so that when you state your hypothesis , your reader understands the specific point you are arguing about.

Background sentences explain the important historical period, dates, people, places, events and concepts that will be mentioned later in your essay. This information should be drawn from your background research .

Example background sentences:

Middle Ages (Year 8 Level)

Castles were an important component of Medieval Britain from the time of the Norman conquest in 1066 until they were phased out in the 15 th and 16 th centuries. Initially introduced as wooden motte and bailey structures on geographical strongpoints, they were rapidly replaced by stone fortresses which incorporated sophisticated defensive designs to improve the defenders’ chances of surviving prolonged sieges.

WWI (Year 9 Level)

The First World War began in 1914 following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The subsequent declarations of war from most of Europe drew other countries into the conflict, including Australia. The Australian Imperial Force joined the war as part of Britain’s armed forces and were dispatched to locations in the Middle East and Western Europe.

Civil Rights (Year 10 Level)

The 1967 Referendum sought to amend the Australian Constitution in order to change the legal standing of the indigenous people in Australia. The fact that 90% of Australians voted in favour of the proposed amendments has been attributed to a series of significant events and people who were dedicated to the referendum’s success.

Ancient Rome (Year 11/12 Level)

In the late second century BC, the Roman novus homo Gaius Marius became one of the most influential men in the Roman Republic. Marius gained this authority through his victory in the Jugurthine War, with his defeat of Jugurtha in 106 BC, and his triumph over the invading Germanic tribes in 101 BC, when he crushed the Teutones at the Battle of Aquae Sextiae (102 BC) and the Cimbri at the Battle of Vercellae (101 BC). Marius also gained great fame through his election to the consulship seven times.

2. Hypothesis

Once you have provided historical context for your essay in your background sentences, you need to state your hypothesis .

A hypothesis is a single sentence that clearly states the argument that your essay will be proving in your body paragraphs .

A good hypothesis contains both the argument and the reasons in support of your argument.

Example hypotheses:

Medieval castles were designed with features that nullified the superior numbers of besieging armies but were ultimately made obsolete by the development of gunpowder artillery.

Australian soldiers’ opinion of the First World War changed from naïve enthusiasm to pessimistic realism as a result of the harsh realities of modern industrial warfare.

The success of the 1967 Referendum was a direct result of the efforts of First Nations leaders such as Charles Perkins, Faith Bandler and the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders.

Gaius Marius was the most one of the most significant personalities in the 1 st century BC due to his effect on the political, military and social structures of the Roman state.

3. Elaboration sentences

Once you have stated your argument in your hypothesis , you need to provide particular information about how you’re going to prove your argument.

Your elaboration sentences should be one or two sentences that provide specific details about how you’re going to cover the argument in your three body paragraphs.

You might also briefly summarise two or three of your main points.

Finally, explain any important key words, phrases or concepts that you’ve used in your hypothesis, you’ll need to do this in your elaboration sentences.

Example elaboration sentences:

By the height of the Middle Ages, feudal lords were investing significant sums of money by incorporating concentric walls and guard towers to maximise their defensive potential. These developments were so successful that many medieval armies avoided sieges in the late period.

Following Britain's official declaration of war on Germany, young Australian men voluntarily enlisted into the army, which was further encouraged by government propaganda about the moral justifications for the conflict. However, following the initial engagements on the Gallipoli peninsula, enthusiasm declined.

The political activity of key indigenous figures and the formation of activism organisations focused on indigenous resulted in a wider spread of messages to the general Australian public. The generation of powerful images and speeches has been frequently cited by modern historians as crucial to the referendum results.

While Marius is best known for his military reforms, it is the subsequent impacts of this reform on the way other Romans approached the attainment of magistracies and how public expectations of military leaders changed that had the longest impacts on the late republican period.

4. Signpost sentence

The final sentence of your introduction should prepare the reader for the topic of your first body paragraph. The main purpose of this sentence is to provide cohesion between your introductory paragraph and you first body paragraph .

Therefore, a signpost sentence indicates where you will begin proving the argument that you set out in your hypothesis and usually states the importance of the first point that you’re about to make.

Example signpost sentences:

The early development of castles is best understood when examining their military purpose.

The naïve attitudes of those who volunteered in 1914 can be clearly seen in the personal letters and diaries that they themselves wrote.

The significance of these people is evident when examining the lack of political representation the indigenous people experience in the early half of the 20 th century.

The origin of Marius’ later achievements was his military reform in 107 BC, which occurred when he was first elected as consul.

Putting it all together

Once you have written all four parts of the BHES structure, you should have a completed introduction paragraph. In the examples above, we have shown each part separately. Below you will see the completed paragraphs so that you can appreciate what an introduction should look like.

Example introduction paragraphs:

Castles were an important component of Medieval Britain from the time of the Norman conquest in 1066 until they were phased out in the 15th and 16th centuries. Initially introduced as wooden motte and bailey structures on geographical strongpoints, they were rapidly replaced by stone fortresses which incorporated sophisticated defensive designs to improve the defenders’ chances of surviving prolonged sieges. Medieval castles were designed with features that nullified the superior numbers of besieging armies, but were ultimately made obsolete by the development of gunpowder artillery. By the height of the Middle Ages, feudal lords were investing significant sums of money by incorporating concentric walls and guard towers to maximise their defensive potential. These developments were so successful that many medieval armies avoided sieges in the late period. The early development of castles is best understood when examining their military purpose.

The First World War began in 1914 following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The subsequent declarations of war from most of Europe drew other countries into the conflict, including Australia. The Australian Imperial Force joined the war as part of Britain’s armed forces and were dispatched to locations in the Middle East and Western Europe. Australian soldiers’ opinion of the First World War changed from naïve enthusiasm to pessimistic realism as a result of the harsh realities of modern industrial warfare. Following Britain's official declaration of war on Germany, young Australian men voluntarily enlisted into the army, which was further encouraged by government propaganda about the moral justifications for the conflict. However, following the initial engagements on the Gallipoli peninsula, enthusiasm declined. The naïve attitudes of those who volunteered in 1914 can be clearly seen in the personal letters and diaries that they themselves wrote.

The 1967 Referendum sought to amend the Australian Constitution in order to change the legal standing of the indigenous people in Australia. The fact that 90% of Australians voted in favour of the proposed amendments has been attributed to a series of significant events and people who were dedicated to the referendum’s success. The success of the 1967 Referendum was a direct result of the efforts of First Nations leaders such as Charles Perkins, Faith Bandler and the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. The political activity of key indigenous figures and the formation of activism organisations focused on indigenous resulted in a wider spread of messages to the general Australian public. The generation of powerful images and speeches has been frequently cited by modern historians as crucial to the referendum results. The significance of these people is evident when examining the lack of political representation the indigenous people experience in the early half of the 20th century.

In the late second century BC, the Roman novus homo Gaius Marius became one of the most influential men in the Roman Republic. Marius gained this authority through his victory in the Jugurthine War, with his defeat of Jugurtha in 106 BC, and his triumph over the invading Germanic tribes in 101 BC, when he crushed the Teutones at the Battle of Aquae Sextiae (102 BC) and the Cimbri at the Battle of Vercellae (101 BC). Marius also gained great fame through his election to the consulship seven times. Gaius Marius was the most one of the most significant personalities in the 1st century BC due to his effect on the political, military and social structures of the Roman state. While Marius is best known for his military reforms, it is the subsequent impacts of this reform on the way other Romans approached the attainment of magistracies and how public expectations of military leaders changed that had the longest impacts on the late republican period. The origin of Marius’ later achievements was his military reform in 107 BC, which occurred when he was first elected as consul.

Additional resources

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Heritage in contemporary grade 10 South African history textbooks: A case study

2012, Masters Dissertation in History Education

Related Papers

Yesterday&Today No 10

Dr Raymond Nkwenti Fru

Yesterday and Today

Johan Wassermann

Southern African journal of environmental education

Cryton Zazu

This conceptual paper is based on experiences and insights which have emerged from my quest to develop a conceptual framework for working with the term 'heritage' within an education for sustainable development study that I am currently conducting. Of specific interest to me, and having potential to improve the relevance and quality of heritage education in southern Africa, given the region's inherent cultural diversity and colonial history, is the need for 'heritage construct inclusivity' within the processes constituting heritage education practices. Working around this broad research goal, I therefore needed to be clear about what I mean or refer to as heritage. I realised, however, how elusive and conceptually problematic the term 'heritage' is. I therefore, drawing from literature and experiences gained during field observations and focus group interviews, came up with the idea of working with three viewpoints of heritage. Drawing on real life cases ...

Alta Engelbrecht

This article focuses on the analysis of three textbooks that are based on the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS), a revised curriculum from the National Curriculum Statement which was implemented in 2008. The article uses one element of a historical thinking framework, the analysis of primary sources, to evaluate the textbooks. In the analysis of primary sources the three heuristics distilled by Wineburg (2001) such as sourcing, corroborating and contextualizing are used to evaluate the utilisation of the primary sources in the three textbooks. According to the findings of this article, the writing of the three textbooks is still framed in an outdated mode of textbooks' writing in a dominant narrative style, influenced by Ranke's scientific paradigm or realism. The three textbooks have many primary sources that are poorly contextualized and which inhibit the implementation of sourcing, corroborating and contextualizing heuristics. Although, some primary sources are contextualized, source-based questions are not reflecting most of the elements of sourcing, corroborating and contextualizing heuristics. Instead, they are mostly focused on the information on the source which is influenced by the authors' conventional epistemological beliefs about school history as a compendium of facts. This poor contextualization of sources impacted negatively on the analysis of primary sources by learners as part and parcel of " doing history " in the classroom.

abram mothiba

School history textbooks are seen to embody ideological messages about whose history is important, as they aim both to develop an 'ideal' citizen and teach the subject of history. Since the 1940s, when the first study was done, there have been studies of South African history textbooks that have analysed different aspects of textbooks. These studies often happen at a time of political change (for example, after South Africa became a republic in 1961 or post-apartheid) which often coincides with a time of curriculum change. This article provides an overview of all the studies of South African history textbooks since the 1940s. We compiled a data base of all studies conducted on history textbooks, including post graduate dissertations, published journal articles, books and book chapters. This article firstly provides a broad overview of all the peer-reviewed studies, noting in particular how the number of studies has increased since 2000. The second section then engages in a more detailed analysis of the studies that did content analysis of textbooks. We compare how each study has engaged with the following issues: the object of study, the methodological approach, the sample of textbooks and the theoretical or philosophical orientation. The aim is to provide a broad picture of the state of textbook analysis studies over the past 75 years, and to build up a database of these studies so as to provide an overview of the nature of history textbook research in South Africa.

Pranitha Bharath

The Southern African Journal of Environmental Education

Felisa Tibbitts

RELATED PAPERS

쇼타임카지노주소〃〃GCN777。COM〃〃바카라신규가입쿠폰

Melquesedeque Cardoso Borrete

Julien Divay

Babatunde Adeoye

Etienne Simiclah

Zeitschrift f�r Physik D Atoms, Molecules and Clusters

Elisabeth Rachlew

Latin American Journal of Aquatic Research

Luisa Saavedra

Guillermo Nuñez

Journal of the American Chemical Society

Liat Spasser

Nindy Puspitasari Giarto

Fergus Neville

Organizational Dynamics

RSC Advances

Orawan Wiranwetchayan

Ralf Schneider

Bernard Deprez

Ravindra Mane

Research in Psychotherapy : Psychopathology, Process, and Outcome

DOAJ (DOAJ: Directory of Open Access Journals)

Octavian Pastravanu

AAPG Bulletin

Ronald Nelson

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition

Felix Sánchez-Valverde

Journal of Clinical Investigation

Wendy Mathes

British Small Animal Veterinary Association eBooks

Friederike Rau

Arturo Garcia S

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Projects Heartlines Fathers Matter What's Your Story? Values & Money

Nothing in your cart yet, add something .

Heritage Day reflections

We recently celebrated Heritage Day in our beloved South Africa. This led me to reflect on the heritage we have as a country with its diverse people and eleven official languages, which are Afrikaans, English, isiNdebele, Sepedi, Sesotho, siSwati, Xitsonga, Setswana), Tshivenda, isiXhosa and isiZulu. Language is part of our heritage and is linked to our identity. Sadly, for the Khoi and San people, South Africa’s first inhabitants do not have their languages recognised as official.

As a person of mixed race I struggled with my identity through childhood and my first few years at high school. This is a common challenge for many mixed race people in our country. During my high school years, I began to read the Bible more intensely and discovered my true identity in its pages – right from Genesis through to Revelation. In Genesis we discover Adam and Eve as the mother and father of all humankind. We also discover that we were made in God’s image. We learn in Ephesians 1:5 that “God decided in advance to adopt us into his own family by bringing us to himself through Jesus Christ. This is what he wanted to do, and it gave him great pleasure.” This discovery was life changing and brought about a freedom and acceptance of myself even though I do not know the full story of my biological heritage.

“…and there was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages, standing before the throne and before the Lamb, robed in white, with palm branches in their hands” Revelation 7:9. So, turn to the Bible with renewed curiosity to discover your true identity and family heritage for yourself.

Rainbow dream

Heritage Day also made me ask the question, “Is the dream of a true rainbow nation still possible?” Following the recent unrest and violence which took place in our country, particularly the murders in Phoenix, and with the narrative in the media of racism, and many conversations taking place referencing the 1949 riots, you begin to wonder if there is hope for our rainbow nation.

Last week I was privileged to be a part of a two-day Bridge Leadership Engagement with church leaders from the PINKU Region (Phoenix, Inanda, Ntuzuma, Kwa Mashu, Umhlanga/Durban North. I watched this group of ministers representing all the racial diversity in our country, connecting at a deeper level through the sharing of their stories. Watching them working together, identifying the problems in their communities and a commitment to finding solutions to build their communities and our beloved country. Part of our godly heritage is love and reconciliation which was exemplified in the life of Jesus Christ. Let us be practitioners of love and reconciliation because of Christ.

God put the first rainbow in the sky as a beacon of hope for Noah. This gives me a reason to hope that the dream of a rainbow nation is still alive!

Craig Bouchier

Craig is a Heartlines' regional representative who has worked in in different ministry roles for many years. Read more about Craig and his journey from playing soccer for AmaZulu FC, to climbing the corporate ladder and taking up his calling into ministry.

We're taking Values & Money into communities!

You may also like, rise up with hope.

Brett 'Fish' Anderson encourages us to fight for hope in the midst of the darkness and suffering we see in the world around us.

Remembering Sharpeville and reflecting on human rights

Olefile Masangane shares his thoughts on why we need to remember where we have come from as we commemorate Human Right's Day and observe Lent this March.

Advent reflection for 2021

Edwin Arrison shares how the hope of Christ can change our perspective and focus in a chaotic, painful world.

The hope of Spring

Relationship and family therapist Merrishia Singh-Naicker shares her thoughts on how we can enter into the new season of Spring with renewed hope, even as we honestly face the reality of increasing violence against women and girls.

We see you're enjoying the site

We have hundreds of digital downloads, guides, videos and other resources to help you and your community live out positive values. Sign up now to get access to resources, online courses and more from across all our projects.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

HISTORY Gr. 10 T1 W7: The Heritage Research Assignment: Theory - the nature of heritage and debates around it

This term will now focus on The Heritage Research Assignment: Theory. This week will focus on the nature of heritage and debates around it.

Do you have an educational app, video, ebook, course or eResource?

Contribute to the Western Cape Education Department's ePortal to make a difference.

Home Contact us Terms of Use Privacy Policy Western Cape Government © 2024. All rights reserved.

Services on Demand

Related links, yesterday and today, on-line version issn 2309-9003 print version issn 2223-0386, y&t n.10 vanderbijlpark jan. 2013.

The contested nature of heritage in Grade 10 South African History textbooks: a case study

Nkwenti Fru; Johan Wassermann; Marshall Maposa

University of Kwa-Zulu Natal [email protected] , [email protected] & [email protected]

Using the interpretivist paradigm and approached from a qualitative perspective, this case study produced data on three purposively selected contemporary South African history textbooks with regards to their representation ofheritage. Lexicalisation, a form of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), was used as method to analyse the pre-generated data from the selected textbooks. In this Fairclough's (2003) three dimensions of describing, interpreting, and explaining the text was followed. The study adopted a holistic approach to heritage as a conceptual framework whilst following social constructionism as the lens through which heritage was explored in the selected textbooks. The findings from this study concluded that although educational policy in the form of the National Curriculum Statement - NCS-History clearly stipulates the expectations to be achieved from the teaching and learning ofheritage at Grade 10 level, there are inconsistencies and contradictions at the level of implementation of the heritage outcome in the history textbooks. Key among the findings are the absence of representation of natural heritage, lack of clear conceptualisation of heritage, many diverse pedagogic approaches towards heritage depiction, a gender and race representation of heritage that suggests an inclination towards patriarchy and a desire to retain apartheid and colonial dogma respectively, and finally a confirmation of the tension in the heritage/history relationship.

Keywords: Heritage; History; Textbooks; Lexicalisation; CDA.

Introduction and Background

There have been significant developments in education in South Africa since the demise of apartheid in 1994. The ultimate goal of these changes has been to redress the injustices of the apartheid curriculum. Msila (2007) submits that education is not a neutral act; it is always political. Education in the apartheid era was used as a weapon to divide society as it constructed different identities amongst learners. This is evidenced in the statement made by Dr H.F. Verwoerd, the then Minister of Native Affairs in 1955, "when I have control over native education, I will reform it so that natives will be taught from childhood that equality with Europeans is not for them" (Christie, 1985, p. 12. Cited in Naiker, 1998, p. 9).

The national policy on South African living heritage (2009) of the Department of Arts and Culture explains this situation further by revealing that the history of apartheid ensured that heritage aspects such as the practice and promotion of languages, the performing arts, rituals, social practices and indigenous knowledge of various social groups were not balanced and were strongly and systematically discouraged. Summarily, it is evident that the apartheid authorities ensured that the heritage of the people of colour in South Africa was never appreciated or promoted. An example of this was the false impression that was created that traditional dress code and traditional dances of certain groups were backward and clashed with colonial adopted practices such as Christianity (Department of Arts and Culture, 2009).

With the end of apartheid, heritage was included as one of the outcomes of the NCS-History. The NCS-History stated that in addition to enquiry skills, historical conceptual understanding and knowledge construction and communication, learners of history were to be introduced to issues and debates around heritage and public representations, and they were expected to work progressively towards engaging with them (Department of Education, 2003). The implication here is that learners were expected to engage with different customs, cultures, traditions and in other words, different heritages. It should be noted that the NCS was replaced in 2011 with the Curriculum Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) as part of the process of curriculum transformation in South Africa. The new CAPS-History for Grade 10 document deals with heritage by explicitly inviting learners to engage with what constitutes heritage as well as to investigate this in a research project. Notwithstanding, the scope of this article was limited to the NCS and selected Grade 10 history textbooks.

Furthermore, in the context of this article it is necessary to understand that the curriculum is articulated by means of textbooks. As the most commonly used teaching resource and the vehicle through which the curriculum is made public, the history textbook has the potential to play a significant part in the implementation of heritage education. History textbooks and textbooks in general have been widely acknowledged as very important instructional materials to support teachers, lecturers, pupils and students in following a curriculum (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2011; Lin et al., 2009; Johannesson, 2002; Romanowski, 1996; Schoeman, 2009; Sewall, 2004; and Wakefield, 2006). However, in spite of this vital pedagogic role, some scholars have questioned their neutrality. In light of this, Apple and Christian-Smith (1991, p. 3) argued that "...texts are not simply delivery systems of facts. They are at once the result of political, economic and cultural activities, battles and compromised. They are conceived, designed and authored by people with real interest. They are published within the political and economic constraints of markets, resources and power". Therefore history textbooks by their nature tend to "control knowledge as well as transmit it, and reinforce selective cultural values in learners (Engelbrecht, 2006, p. 1). The implication of this nature of history textbooks in terms of this study is that the textbooks are not neutral even in the way they represent heritage as an outcome of the curriculum.

It is necessary to note that the presence of heritage in the curriculum and the textbooks has not eliminated some of the controversies and the contestations surrounding heritage. The reality on the ground is not always congruent with the lofty aims of the constitution and the aspirations of the post-1994 South African government. A major concern here is about shared heritage, if indeed this notion exists. Recently the South African national and some local government structures have embarked on a project to change place names and street names. Though this can be understood in the context of reconstruction of a post-conflict society, such actions, however, provoke questions such as: whose heritage is being promoted? Is national heritage actually the heritage of the nation or its inhabitants? It equally increases the debate on the place of history as well as the heritage/history dichotomy. What should be retained and preserved? What should be discarded and why? On the one hand there is the will to acknowledge the past and create inclusiveness in society as proclaimed in the constitution and the curriculum, but on the other hand there is the difficulty of its practicability.

Towards a conceptual framework of Heritage

Many scholars have indicated that heritage as a concept is a malleable one. It is largely ambiguous, very difficult and debatable, and full of paradoxes (Copeland, 2004; Edson, 2004; Kros, 2003; Marschall, 2010; Morrow, 2002; van Wijk, no date & Vecco, 2010). It is therefore evident that heritage as a concept has numerous meanings based on context, time and ideology. Whilst some of the scholars mentioned above place more emphasis on tangible objects such as monuments to comprise heritage, others are of the firm view that heritage surpasses the tangible and includes aspects that are intangible. These two opinions largely characterise discussions on the meaning of heritage and have rendered it difficult to establish a dichotomy for heritage.

From a simple understanding, the word tangible would mean, items that can be seen, touched and/or felt physically while intangible would refer to the opposite of the above. In relation to heritage, this knowledge seems to have an influence in the general understanding of the tangible and the intangible nature of it. Tangible heritage would be heritage resources that can be experienced, seen, touched, and walked around and through (Adler et al., 1987). Examples of such resources include historic architecture, artefacts in museums, monuments, buildings, graves, landscapes, remains of dwellings and military sites including memorials and battle fields that form part of the history of a given community.

Articles one and two of the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (UNESCO, 1972) identify two categories of tangible heritages, cultural and natural tangible heritage. In the first part, it considers cultural tangible heritage to be monuments, groups of buildings and sites and work of people or the combined works of nature and people that are of outstanding value whether from the point of view of history, art or science, or from the historical, aesthetic, ethnological or even anthropological view point. The second part of the convention considers natural tangible heritage in three dimensions, namely: as natural features consisting of physical and biological formations; as geological and physiological formations and precisely delineated areas which constitute the habitat of threatened species of animals and plants, and finally as precisely delineated natural areas of outstanding value from the point of view of science conservation and natural beauty. The connotation therefore is that tangible heritage could either appear in natural or cultural form. Copeland (2004) however, cautions that in whichever form it appears, it must be able to stimulate the imagination for it to be considered as heritage. It is also possible that some properties might satisfy more than one of these definitions. For example, a property can be both a monument and a group of buildings.

Regarding intangible heritage, a succinct meaning is provided by Deacon, Dondolo, Mrubata, and Prosalindis (2004). Their view is that intangible heritage consists of oral traditions, memories, languages, performing arts or rituals, knowledge systems and values and know-how that a family or community wish to safeguard and pass on to future generations. This involves the way of life of a people and is usually embedded in their customs, traditions and cultural practices. In other terms, it "refers to aesthetic, spiritual, symbolic or other social values that ordinary people associate with an object or a site" (Marschall, 2010, p. 35). Intangible heritage is also known as living heritage and can appear in cultural form (Bredekamp, 2004; Department of Arts and Culture, 2009). As with tangible heritage, some intangible heritage resources also have cultural properties which are sometimes called intangible cultural heritage such as songs.

One common aspect among researchers is the idea that all these different forms of heritage do not stand independent of each other (Bredekamp, 2004; Edson, 2004; Jones, 2009; Marschall, 2010; Munjeri, 2004). They are so interconnected to the extent that a study on one will require a systematic understanding of the other and vice versa. Whether tangible or intangible; natural, cultural or living; movable or immovable, it is evident that they all complement each other. Therefore a full understanding of heritage can only be achieved through a study of the multiple reciprocal relationships between the tangible and the intangible elements.

It is this inter-relationship that is termed IN-Tangible heritage in this article. This means that intangible can be part of the tangible with the former defining the latter. In the tangible is the intangible and the reverse might also be true. An example of this scenario is of distinctive cultural landscapes that have spiritual significance (Bredekamp, 2004). The landscape in this example is an IN-Tangible resource because it contains elements of both the tangible and the intangible through the physical landscape and its underlying spiritual significance.

In Image 1 above, A represents aspects of heritage that are tangible while B stands for the intangible heritage. C represents the relationship between A and B which is the IN-Tangible in this framework. The link attaching the three components symbolises their inter-connected relationship as explained earlier. These three aspects together portray a holistic understanding of heritage.

This understanding of heritage is therefore a holistic one and embraces both the tangible and the intangible components of heritage. It is this approach that will serve as the conceptual framework for this study. Contrary to a reductionist approach, the holistic perspective is more inclusive (Perez et al, 2010). In addition to accommodating tangible and intangible components of heritage in cultural and/or natural forms, holistic heritage also acknowledges heritage at personal, family, community, state and world levels. The table below is a representation of the holistic manifestation of heritage as identified by Perez et al (2010):

Methodology

This study adopts a qualitative design. Gonzales et al., cited in Cohen et al (2011) submit that this form of research is concerned with an in-depth, intricate and detailed understanding of phenomenon, attitudes, intentions and behaviours. By implication, a qualitative study should produce findings that are not reached by means of quantification. The qualitative study is approached from the interpretive paradigm. Blanche and Kelly (2002, p. 123) submit that "interpretivist research methods try to describe and interpret people's feelings and experiences in human terms rather than through quantification and measurements".

The link between the qualitative research design and the interpretive paradigm is highlighted by Stevens et al (1993) who suggests that research carried out in the interpretive paradigm is called qualitative research. The focus of this article is to gain an understanding of the nature of heritage representation in selected Grade 10 South African history textbooks. This merges with the interpretive paradigm, especially considering Henning's view that the core of the interpretive paradigm is not about the search for broadly applicable laws and rules, but rather it seeks to produce descriptive analysis that emphasises deep, interpretive understanding of social phenomena (Henning, 2004). As a result, this study will produce rich descriptions of the characteristics, processes, transactions and contexts that constitute the nature of heritage in the selected history textbooks as the phenomena being studied.

The sample choice adopted for this article is non-random sampling. Christensen (2011) explains that the aim of non-random sampling is to study phenomena and interpret results in their specific context. Therefore the primary concern of a researcher using this sampling method is not to generalise research outcomes to the entire population but to provide detailed descriptions and analysis within the confines of the selected units of analysis - in this study the selected Grade 10 history textbooks. Explained differently, the focus of this study is to generate rich qualitative data as oppose to achieving statistical accuracy or representativeness of data to an entire population.

The specific genre of non-random sampling employed in this article was the purposive sampling method. This kind of sampling is a feature of qualitative research in which "researchers purposely choose subjects who, in their opinion, are relevant to the project" (Sarantakos, 2005, p. 164). In light of the above, the sample choice in this article were handpicked based on their possession of the phenomenon being sought - heritage. Furthermore, an implication of the study being qualitative is that the sample size is irrelevant since the interest is in attaining in-depth understanding. The Table below is a representation of this sample.

The methodology employed to analyse the data from the textbooks was the Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA). The overarching theme derived from the literature reviewed on CDA is the idea that it is concerned with the analysis of how language and discourse is used to achieve social goals and also the part the use of language plays in social maintenance and change. The broad and complex nature of discourse itself, and CDA in particular, also reflects that there are many methods involved in using it for analysis. With this in mind, the choices made for analysis in this study are borrowed from both Fairclough's idea of the structure of the text and Halliday's notion of the grammatical aspects of the text otherwise known as interactional analysis, which deals with the linguistic features of the text (Meyer, 2001). These two aspects that are illustrated in Image 2 below constituted the method used to analyse the data for this study.

In his analytical framework for CDA, Fairclough proposes three dimensions of analysing texts that include description (text analysis), interpretation (processing analysis), and explanation (social analysis) (Fairclough, 1989, 1992, 1995, cited in Locke, 2004, p. 42 and Rogers et al., 2005, p. 371). As Image 2 indicates, the first goal therefore is to deal with the internal mechanisms of the text and the focus is on aspects of text analysis that include grammar and vocabulary, as influenced by Halliday.

In the second level of analysis which is interpretation, the goal is to interpret the data captured and described in the previous section. This is done in relation to the conceptual framework in such a way that the indicators in the framework, serves as signifiers in the analytical instrument. Aspects of lexicalisation are then checked against the indicators in the conceptual framework. Table 3 below is an example of the instrument recruited for analysis at step two.

Finally, the last step of analysis is the level of explanation known as social analysis. At this stage, data obtained from the description and interpretation of the textbooks are compared and contrasted with the purpose of establishing the trends and patterns of heritage representation as obtained in the three textbooks across the publications. This stage particularly exposed how heritage is conceptualised and portrayed in the history textbooks - which is the research question underpinning this study.

Moreover, the methods considered for analysis in this study also included an examination of issues of gender, race, and geography within the selected textbooks as part of CDA. This was inspired by van Dijk (2001) who suggested that CDA is mainly interested in the role of discourse in the abuse and reproduction of power and hence particularly interested in the detailed study of the interface between the structures of discourse and the structures of society. Therefore the analysis progressed systematically from description to interpretation and then to explanation of the data.

Analysis and Findings

In search of history, Grade 10, Learner's book (Bottaro et al., 2005)

In its conceptualisation of heritage, this textbook ignores natural heritage as a form of heritage. This is evident in the absence of lexicons relating to this indicator of heritage. Emphasis is therefore on cultural heritage, with symbolic-identity heritage being the main form of cultural heritage represented in the conceptualisation. The other indicators of scientific-technological and ethnological heritage are also absent. The implication, therefore, in this textbook, is that heritage is a cultural concept of a mainly symbolic-identity nature. This trend is also replicated in the two case studies of heritage in the book with lexicons of symbolic-identity nature prioritised over other indicators. However, with the case study on 'Great Zimbabwe', mention is made of natural heritage resources namely 'the Limpopo and Zambezi rivers'. Yet the context in which natural heritage is used in the text does not seem to promote this form of heritage but rather it is used within the framework of symbolism and identity as it only serves to locate the habitat of the Shona people who are seen as "descendants of the people of builders of Great Zimbabwe" (Bottaro et al., 2005, p. 220).

The analysis of the above indicators also revealed the nature of representation of other discourses relevant to post-conflict societies such as gender, race, and geography. Although in some of these instances, some discrepancy in the nature of these representations was noted, this could also be seen within the context of a historiographical turn in post-conflict South Africa with attempts to make heritage and history more inclusive as required by the constitution and sanctioned by the NCS-History. Therefore to a large extent, the representation shows an attempt to portray shared, inclusive and international heritage from the perspective of the indicators noted above.

Furthermore, the textbook's view of heritage also concurs with the conceptual framework on heritage as being tangible, intangible or IN-Tangible. Even though the findings show more affinity towards intangible heritage, some aspects of tangible heritage are also mentioned. However, evidence from the textbook suggests that heritage cannot be purely tangible - it can only be intangible or IN-Tangible. This claim is made based on the lexical examples used in the conceptualisation and the two case studies. For example, monuments and historic buildings are tangible but they are only heritage icons because of what they represent, which is intangible - meaning they are both tangible and intangible.

Attempts to present heritage as a shared and inclusive practice is also truly illustrated by pronoun choices. At the level of conceptualisation, the text makes use of personal pronouns as the first person plural form such as "we", "our" and "us" to refer to heritage.

Therefore by means of CDA, the analysis of this textbook revealed that it views heritage as a cultural concept of mainly symbolic-identity nature. Through the choice of pronouns used the book attempts to portray a shared and inclusive heritage in terms of geography, gender and race. However lexicons such as 'their heritage' are also used to imply that not all heritages can be shared, and this confirms the complex nature of the heritage concept itself.

Shuters history, Grade 10, Learner's book (Dlamini et al., 2005)

The first realisation was that this textbook has no clear narration or discourse that runs through the heritage chapter - chapter 8 (pp. 222-240). It is published in the form of visuals (pictures), sources, with assessment activities to support and enhance meaning in the textual content. This style has an implication in the way the book presents heritage because in this sense, heritage is seen as a highly contested and sometimes controversial concept whose presentation must be backed by relevant sources and evidence - therefore the choice of this book to provide as many sources to support its use of lexicons in portraying heritage.

Moreover, findings from this book on the concept ofheritage show a limitation of heritage representation to South Africa and the southern African region. International heritage in this book therefore manifests in the representation of geographical spaces of these regions only. This dimension of heritage is also supported by the choice of pronouns used in the text, such as 'we' and 'our'. The choice of the first person plural pronouns also indicates collective, shared and inclusive heritage, in the South African and southern African region, but also that heritage is an inclusive and shared concept that could and should be understood beyond individual perspectives or national frontiers.

But this inclusive and shared form of heritage is unfortunately weakened by the fact that there is evidence of unequal representation of lexical indicators of heritage linked to issues of gender and race. For example, in most instances throughout the book, with the exception of Saartjie Baartman, women are only implicitly expressed while masculinity is overtly used in more than one occasion to illustrate examples of heritage icons. Regarding racial bias, a case in point is the South African context where the choice of examples selected is not fully representative of the South African diverse ethno-racial landscape. Generally, there is an emphasis on southern African heritage with examples of the Khoisan represented by Baartman, El Negro and rock art, advanced to illustrate this (p. 318). It is also portrayed in the example of Great Zimbabwe and Mapungubwe.

Apropos of the heritage conceptual indicators, the conceptualisation and the case study analysis of this book show evidence of a lack of representation of lexicons of the natural heritage category, resulting in a focus on cultural heritage. In this regard the different indicators of cultural heritage are applied in different proportions and subsequently, symbolic-identity heritage as a category of cultural heritage is promoted at the expense of other indicators of the same category such as ethnological heritage and scientific-technological heritage, which are used sparingly.