Global value chains: A review of the multi-disciplinary literature

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 25 February 2020

- Volume 51 , pages 577–622, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Liena Kano 1 ,

- Eric W. K. Tsang 2 &

- Henry Wai-chung Yeung 3

85k Accesses

283 Citations

29 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This article reviews the rapidly growing domain of global value chain (GVC) research by analyzing several highly cited conceptual frameworks and then appraising GVC studies published in such disciplines as international business, general management, supply chain management, operations management, economic geography, regional and development studies, and international political economy. Building on GVC conceptual frameworks, we conducted the review based on a comparative institutional perspective that encompasses critical governance issues at the micro-, GVC, and macro-levels. Our results indicate that some of these issues have garnered significantly more scholarly attention than others. We suggest several future research topics such as microfoundations of GVC governance, GVC mapping, learning, impact of lead firm ownership and strategy, dynamics of GVC arrangements, value creation and distribution, financialization, digitization, the impact of renewed protectionism, the impact of GVCs on their macro-environment, and chain-level performance management.

Cet article passe en revue le domaine en pleine expansion de la recherche sur la chaîne de valeur mondiale (CVM) en analysant plusieurs cadres conceptuels très cités, puis en évaluant les études sur la CVM publiées dans des disciplines telles que l’ international business , le management général, la gestion de la chaîne logistique, la gestion de production, la géographie économique, les études régionales et de développement, et l’économie politique internationale. En s’appuyant sur les cadres conceptuels de la CVM, nous avons mené la revue en nous fondant sur une perspective institutionnelle comparative qui englobe les questions de gouvernance essentielles aux niveaux micro, de la CVM et macro. Nos résultats indiquent que certaines de ces questions ont suscité beaucoup plus d’attention de la part des chercheurs que d’autres. Nous proposons plusieurs sujets de recherche pour l’avenir, tels que les micro-fondations de la gouvernance des CVM, la cartographie des CVM, l’apprentissage, l’impact de la propriété et de la stratégie des entreprises chefs de file, la dynamique des arrangements des CVM, la création et la distribution de la valeur, la financiarisation, la numérisation, l’impact du protectionnisme renouvelé, l’impact des CVM sur leur macro-environnement et la gestion des performances au niveau de la chaîne.

Este artículo revisa el dominio de rápido crecimiento de la investigación sobre la cadena de valor global (GVC por sus iniciales en inglés) analizando varios marcos conceptuales altamente citados y luego evalúa los estudios sobre GVC publicados en disciplinas como negocios internacionales, gerencia general, gestión de la cadena de suministro, gestión de operaciones, geografía económica, estudios regionales y de desarrollo, y economía política internacional. Sobre la base de los marcos conceptuales de GVC, realizamos la revisión basada en una perspectiva institucional comparativa que abarca cuestiones críticas de gobernanza a nivel micro, GVC y macro. Nuestros resultados indican que algunos de estos asuntos han recogido mucha más atención académica que otros. Sugerimos varios temas de investigación futuros, tales como los microfundamentos de la gobernanza de las GVC, el mapeo de las GVC, el aprendizaje, impacto de la propiedad y estrategia de la empresa líder, la dinámica de los acuerdos de la GVC, la creación y distribución de valor, la financiarización, la digitalización, el impacto del proteccionismo renovado, el impacto de las GVC en su macroambiente y la gestión del desempeño a nivel de cadena.

Este artigo analisa o domínio em rápido crescimento da pesquisa sobre a cadeia global de valor (GVC) analisando vários modelos conceituais altamente citados e avaliando os estudos sobre GVC publicados em disciplinas como negócios internacionais, administração geral, gestão da cadeia de suprimentos, gerenciamento de operações, geografia econômica, estudo regionais e de desenvolvimento e economia política internacional. Com base nos modelos conceituais da GVC, realizamos a revisão com base em uma perspectiva institucional comparativa que abrange questões críticas de governança nos níveis micro, GVC e macro. Nossos resultados indicam que algumas dessas questões atraíram a atenção de acadêmicos mais significativamente do que outras. Sugerimos vários tópicos para futuras pesquisas, como microfundamentos da governança da GVC, mapeamento da GVC, aprendizado, impacto da propriedade e estratégia da empresa líder, dinâmica de acordos da GVC, criação e distribuição de valor, financeirização, digitalização, impacto do protecionismo renovado, impacto das GVCs no seu ambiente macro e gerenciamento de desempenho em nível de cadeia.

本文通过分析几个被高度引用的理论框架,回顾了快速成长的全球价值链(GVC)研究领域,然后评估了在国际商务、通用管理、供应链管理、运营管理、经济地理、区域及发展研究和国际政治经济学中发表的GVC研究。我们建议了一些未来研究主题,例如GVC治理的微观基础、GVC制图、学习、牵头公司所有权及战略的影响,GVC安排的动态性,价值创造与分配、金融化、数字化、新保护主义的影响、GVC对它们的宏观环境的影响,以及链层面上的绩效管理。

Similar content being viewed by others

How digital technologies reshape marketing: evidence from a qualitative investigation

Supply chain disruptions and resilience: a major review and future research agenda

The role of digitalization in business and management: a systematic literature review

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

During the last few decades, the gradual liberalization and deregulation of international trade and investment, coupled with the rapid development and spread of information and communication technologies (ICT), have fundamentally changed how multinational enterprises (MNEs) operate and compete in the globalizing world economy. A clear and yet sophisticated pattern of organizationally fragmented and spatially dispersed international business activity has emerged, whereby offshore production sites located in low-cost developing countries are closely linked with lead firm buyers and MNEs from major consumer markets in North America and Europe (Coe & Yeung, 2015 ; Dicken, 2015 ; Gereffi, 2018 ). New MNEs have also emerged from developing economies, particularly those in East and Southeast Asia, as major strategic partners and manufacturing service providers for traditional MNEs from advanced industrialized economies (Yeung, 2016 ). This pattern signals a new divide in industrial organization on a worldwide scale: a transition from hierarchically organized MNEs, with their traditional focus on managing internalized overseas investments, to MNEs as international lead firms. These firms work with and integrate their geographically dispersed strategic partners, specialized suppliers, and customer bases into complex structures, referred to variously as global commodity chains (GCCs), global value chains (GVCs), global production networks (GPNs), or global factories.

Since Gereffi and Korzeniewicz’s ( 1994 ) collection in the early 1990s, this phenomenon of organizationally fragmented international production has been subject to investigation in a wide range of academic disciplines, including economic sociology, international economics, regional and development studies, economic geography, international political economy, supply chain management, operations management, and international business (IB) (Buckley, 2009a , b ; Coe & Yeung, 2015 , 2019 ; Funk, Arthurs, Treviño, & Joireman, 2010 ; Gereffi, 1994 , 2018 ; Gereffi, Humphrey, & Sturgeon, 2005 ; Henderson, Dicken, Hess, Coe, & Yeung, 2002 ). In economic sociology and development studies, the earliest work was concerned with global commodity trade and the governance structure of such commodity chains in labor-intensive and high-tech industries (Bair, 2009 ; Gereffi, 1999 , 2018 ; Gereffi & Korzeniewicz, 1994 ). This literature has developed a simple typology of buyer-driven and producer-driven GCCs on the basis of the power and control exerted by buyers (retailers and brand name firms) or producers (original equipment manufacturers [OEMs]) in governing their international suppliers and service providers.

In 2000, the Rockefeller Foundation funded a large-scale GVC convention, which marked the beginning of a rapid growth of GVC research (Gereffi, Humphrey, Kaplinsky, & Sturgeon, 2001 ). By the early 2000s – near the beginning point of our review – the GCC literature moved away from its earlier focus on commodities (e.g., clothing, footwear, automobiles) to examining value chains that connected spatially dispersed production activities. In their introduction to a special issue of IDB Bulletin on globalization, value chains, and development, Gereffi et al. ( 2001 ) identified several pressing challenges for value chain researchers and pushed for the use of GVC as a common terminology. Since then, GVC has become the primary focus of research and analytical attention in the social sciences and, lately, international policy communities. The economic sociology view of GVC remains concerned mainly with the social consequences of economic exchange, and with mapping the governance structures/developing typologies of GVCs and their consequences for local upgrading (Gereffi, 2018 ; Gereffi et al., 2005 ; Humphrey & Schmitz, 2002 ). The study of GVCs within the international economics literature focuses on efficiency of contractual organization and economic exchanges in GVCs, and on mapping the geography of international trade flows and value creation (Aichele & Heiland, 2018 ; Antràs & Chor, 2013 ; Grossman & Rossi-Hansberg, 2008 ; Johnson & Noguera, 2012 ; Lee & Yi, 2018 ). IB researchers are interested mainly in how firms can profitably strengthen and exploit their unique firm-specific advantages, and create value by forging business relationships across national borders through MNE activity in GVCs (Buckley, 2009a ; Kano, 2018 ; Laplume, Petersen, & Pearce, 2016 ; Mudambi, 2008 ).

Closely related to the GVC concept is the GPN construct. The GPN concept was developed in the late 1990s by a group of researchers in economic geography, and emerged from a growing dissatisfaction with existing theories of economic development that failed to account for the increasingly complex, networked nature of production activities, which spanned across national borders and led to uneven development in different regions and countries (Coe & Yeung, 2015 , 2019 ; Henderson et al., 2002 ; Hess, 2017 ; Yeung, 2009 , 2018 ). The idea of a GPN goes beyond the simple notions of trading and outsourcing, and highlights firm-specific coordination and cooperation strategies through which such relational networks are constructed, managed, and sustained, as well as the networks’ geographical reach in specific territories, such as sub-national regions and industrial clusters. It also considers the strategic responses of other corporate and non-corporate actors within the GPN, such as the state and business associations. This central focus on economic actors, such as MNEs and their strategic partners, and territorialized institutions, such as state agencies and business associations, also distinguishes GPN thinking from GCC research’s focus on a particular commodity or GVC research’s concern with the aggregation of different value chains into industries.

While the term “GPN” accurately reflects the fact that the firms involved often form intricate intra- and inter-firm networks (rather than linear chains), we propose to use the term “GVCs” in an inclusive fashion throughout this review, to reflect the fact that disaggregation and geographic dispersion presently occurs in various parts of the value chain and encompasses both primary and support activities, with increasingly sophisticated knowledge-intensive processes being offshored and outsourced (Gereffi & Fernandez-Stark, 2010 ). The term “GVC” thus not only refers to manufacturing firms but also characterizes a variety of modern MNEs, including service multinationals and the so called “digital MNEs,” (i.e., firms that use advanced technologies to generate revenues from dispersed foreign locations without investing in production in a conventional sense) (Coviello, Kano, & Liesch, 2017 ). Since the 2010s, the concept and terminology of GVCs have also resonated very well with the development practice and policy communities in many international and regional organizations. A 2010 World Bank report on the post-2008 world economy, for example, claims: “given that production processes in many industries have been fragmented and moved around on a global scale, GVCs have become the world economy’s backbone and central nervous system” (Cattaneo, Gereffi, & Staritz, 2010 : 7). To most observers in these international organizations, GVCs are now recognized as the new long-term structural feature of the global economy (Elms & Low, 2013 ; UNCTAD, 2013 ; World Bank, 2019 , 2020 ).

While we draw on the above complementary research streams and theoretical lenses, we conduct our review from an IB - centric perspective. Following Mudambi ( 2007 , 2008 ) and Buckley ( 2009a , b ), we define a GVC as a governance arrangement that utilizes, within a single structure, multiple governance modes for distinct, geographically dispersed and finely sliced parts of the value chain. In other words, a GVC is the nexus of interconnected functions and operations through which goods and services are produced, distributed, and consumed on a global basis (Coe, Hess, Yeung, Dicken, & Henderson, 2004 ; Coe & Yeung, 2015 ; Henderson et al., 2002 ). IB scholars have recently acknowledged that the rapid rise of GVCs represents one of the most salient features of today’s economy (Turkina & Van Assche, 2018 ), and great strides have been made within mainstream IB literature to understand GVCs (Buckley, Craig, & Mudambi, 2019 ; Gereffi, 2019 ). Yet, surprisingly, there has not been, to the best of our knowledge, a paper that systematically reviews the social scientific and management literatures on GVCs and suggests pointers for future research, specifically for IB scholars. Our review aims to fill this important void.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. We start by developing an organizing framework to guide our systematic review of multidisciplinary literature. This framework is premised on an inclusive theoretical coverage of the seminal works on GVC governance, upgrading, competitive dynamics, and territorial outcomes, and follows comparative institutional analysis logic. We then discuss our review methodology, and present the results of the review of 87 empirical and conceptual studies, organized according to the framework developed. We conclude by assessing the body of literature reviewed, identifying knowledge gaps, and suggesting avenues for future research.

A COMPARATIVE INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK FOR GUIDING LITERATURE REVIEW

Given the complexity of GVC-related phenomena and the resultant multifarious nature of published studies, a guiding conceptual framework is needed to help us systematically categorize and analyze these studies. We have adopted an IB-centric comparative institutional perspective, embodied in internalization theory/transaction cost economics (TCE) (Buckley & Casson, 1976 ; Hennart, 2009 ; Verbeke, 2013 ), as the foundation of our framework. We consider this approach particularly suitable for systematizing our review for two reasons. First, it focuses on comparative efficiency of various types of governance, and therefore explains under what circumstances GVC governance is preferable to other alternatives. Second, a comparative institutional approach incorporates and links together different levels of analysis, such as micro/individual, transaction/a class of transactions, firm, network, and macro environment; such an integrative approach to governance accurately reflects the multifacetedness and complexity of the GVC phenomenon. However, before we elaborate on this organizing framework for reviewing GVC studies, it is useful and necessary to revisit some of the seminal theoretical works on GVC governance and upgrading (Gereffi, 2018 ; Gereffi et al., 2005 ; Humphrey & Schmitz, 2002 ), and network organization and territorial development outcomes (Coe et al., 2004 ; Coe & Yeung, 2015 ; Henderson et al., 2002 ). These social science studies provided content for designing our IB-centric organizing framework.

Seminal Theoretical Works on GVCs and GPNs in the Social Sciences: From GVC to GPN 2.0

In the early 1990s, Gereffi ( 1994 , also 2018 : Chapter 2) developed the first original framework for explaining the organization of international production networks on the basis of the economic power of giant buyers (e.g., largest retailers, supermarkets, and brand-name merchandisers) and producers (e.g., OEMs in automotive and other high-tech industries) in driving these commodity chains. Attempting to move beyond the then national state-centric modes of analyzing the global economy, Gereffi, Korzeniewicz, and Korzeniewicz ( 1994 : 2) defined commodity chains as “sets of interorganizational networks clustered around one commodity or product, linking households, enterprises, and states to one another within the world economy. These networks are situationally specific, socially constructed, and locally integrated, underscoring the social embeddedness of economic organization.” Their idea was to promote a meso scale of analysis that could probe “above and below the level of the nation-state” and reveal the “macro–micro links between processes that are generally assumed to be discretely contained within global, national, and local units of analysis.”

To operationalize these conceptual ideas and the overall “drivenness” (buyer- or producer -driven) of particular commodity chains, Gereffi ( 1994 ) expanded on three main dimensions of commodity chains and networks: (1) an input – output structure that refers to a set of products and services connected together in a sequence of value-adding economic activities; (2) a territoriality that refers to the spatial configuration of the various actors involved, such as spatial dispersion or concentration of production and distribution networks; and (3) a governance structure that reflects the authority and power relationships within the chain, which determine the allocation and flows of materials, capital, technology, and knowledge therein. Despite this early theoretical development, many of the subsequent empirical studies suffered from a “theoretical deficit.” As argued by Dussel Peters ( 2008 : 14), “most research on global commodity chains approaches the GCC framework as a ‘methodology’ and not a ‘theory’. The result of this is vast quantities of empirical work on particular chains and the experiences of particular firms and regions in them, and relatively little theoretical work attempting to account for these findings in a systematic and integrated way.”

Since Gereffi ( 1994 ), nevertheless, much of GVC theory work in the next decade has been focused on the third dimension of commodity chains – inter - firm governance – through mapping GVC governance structures as independent variables and developing typologies of these structures in order to postulate their consequences for industrial upgrading , as dependent variables, at the firm level and in local/regional development (see recent reviews in Coe & Yeung, 2015 , 2019 ; Gereffi, 2018 : Chapter 1). 1 In their important theoretical formulation following Gereffi’s ( 1999 ) influential empirical work on East Asian apparel upgrading trajectories and Kaplinsky and Morris’s ( 2001 ) highly cited handbook for value chain research, Humphrey and Schmitz ( 2002 ) conceptualized four types of GVC-related upgrading in industrial clusters: process upgrading, whereby the production system is made more efficient, perhaps through superior technology; product upgrading, in which firms move into more sophisticated product lines; functional upgrading, in which they acquire new functions to increase their value added; and chain or inter - sectoral upgrading, whereby firms move into new categories of production altogether. More recently, Pietrobelli and Rabellotti ( 2011 ) further theorized the relationships between these upgrading possibilities and different learning mechanisms embedded in local and regional innovation systems.

The most significant theorization of GVC governance , as an independent variable shaping local and regional upgrading outcomes, was Gereffi et al.’s ( 2005 , also in 2018 : Chapter 4) conceptual typology that came a decade after Gereffi’s ( 1994 ) work. In this most cited conceptual GVC study, Gereffi et al. ( 2005 ) drew upon earlier theoretical work on production fragmentation in international business and trade economics, coordination problems in transaction cost economics (TCE), and networks in economic geography and economic sociology. To them, the then recent work by geographers, such as Dicken, Kelly, Olds, and Yeung ( 2001 ) and Henderson et al. ( 2002 ), “has emphasized the complexity of inter-firm relationships in the global economy. The key insight is that coordination and control of global-scale production systems, despite their complexity, can be achieved without direct ownership” (Gereffi et al., 2005 : 81). To theorize this complexity of inter-firm relationships, Gereffi et al. ( 2005 ) constructed a typology of value chain governance by intersecting the three supply-chain variables of complexity of transactions, codifiability of transactions, and the capabilities within the supply base. By ascribing only two values – high or low – to these three variables, they identified a fivefold typology of governance within GVCs. In addition to the pure forms of market and hierarchy , the authors distinguished modular , relational , and captive forms of governance that rely on intermediate levels of coordination and control. While highly influential, this conceptual typology is still arguably somewhat limiting, and underplays the extent to which governance is also shaped by place-specific institutional conditions and intra- and extra-firm dynamics (Coe & Yeung, 2015 ). Further theoretical work mobilized convention theory to focus on the different modes and levels of governance operating within GVCs, distinguishing between overall drivenness, different forms of coordination (the five types of governance noted above), and the wider normalization and standards-setting processes that operate along the value chain (e.g., Gibbon & Ponte, 2008 ; Ponte & Gibbon, 2005 ).

As noted in the Introduction, a parallel theoretical development in the social sciences was the GPN framework developed by Dicken et al. ( 2001 ) and Henderson et al. ( 2002 ). Table 1 offers a comparison between GVC and GPN theoretical approaches that enable the “modular” theory-building efforts proposed by Ponte and Sturgeon ( 2014 ). As part of these efforts, Henderson et al.’s ( 2002 ) GPN 1.0 schema emphasized the complex intra-, inter-, and extra-firm networks involved in any economic activity, and elaborated on how these are structured both organizationally and geographically. This theoretical framework for analyzing the global economy was intended to delimit the globally organized nexus of interconnected functions and operations of firms and extra-firm institutions through which goods and services are produced, distributed, and consumed. The central concern of any GPN analysis therefore should not simply be about considering the networks in their own terms, but should reveal the dynamic developmental impacts on locations and territories interconnected through these networks. GPN 1.0 thus extends beyond the above-mentioned GVC governance approach by (1) bringing extra-firm actors, such as state agencies, non-governmental organizations, and consumer groups, into GPNs; (2) considering firm–territory interactions at multiple spatial scales, from the local and the sub-national to the macro-regional and the global; (3) examining intersecting vertical (intra-firm) and horizontal (inter-firm) connections in production systems; and (4) taking a more complex and contingent view of how GVC governance is shaped by the wider regulatory and institutional contexts.

The most recent and comprehensive theorization of GVCs is found in Coe and Yeung’s ( 2015 ) monograph. This work seeks to develop a dynamic theory of GPNs by specifying the causal mechanisms that explicitly link earlier conceptual categories of value, power, and embeddedness to the dynamic configurations of GPNs and their uneven development outcomes. In this GPN 2.0 framework, the aim is to conceptually connect the structural capitalist dynamics that underpin GPN formation/operation to the on-the-ground development outcomes for local and regional economies. The underlying capitalist dynamics encompass key dimensions such as drivers of lowering cost-capability ratios, market development, financialization and its disciplining effects on firms, and risk management; together, these dimensions distil the inherent imperatives of contemporary global capitalism. These dynamics are key variables driving the strategies adopted by economic actors in (re)configuring their GPNs, and consequent value capture trajectories and developmental outcomes in different industries, regions, and countries. Interestingly, these competitive dynamics are not well theorized in the existing GVC literature, which is much more concerned with governance aspects of the operation of such chains and networks after they are formed. Coe and Yeung ( 2015 ) considered how these causal drivers shaped the strategies of different kinds of firms in GPNs. These firms organize their activities through different configurations of intra-, inter-, and extra-firm network relationships. Conceptually, these network configurations are shaped by different interactions of the underlying dynamics. The authors then examined the consequences of these causal mechanisms – comprising varying dynamics and strategies – for firms in GPNs.

Fuller and Phelps ( 2018 ) further explained how parent–subsidiary relationships in MNEs can significantly influence the way that these competitive dynamics shape their network embeddedness in and strategic coupling with specific regional economies (Yeung, 2009 , 2016 ). Departing from the industrial upgrading literature that often takes on a unidirectional pathway to upgrading (from process to value chain upgrading in Humphrey and Schmitz ( 2002 )), Coe and Yeung ( 2015 ) further developed the concept of “value capture trajectories” to frame in dynamic terms whether firms are able or not to capture the gains from strategic coupling in GPNs. Ultimately, this GPN 2.0 work seeks to understand the impacts on territorial development by exploring how firm-specific value capture trajectories can coalesce in particular places and locations into dominant modes and types of strategic coupling, with different potential for value capture in the regional and the national economies.

Similar to other theories in the social sciences, the GVC/GPN frameworks discussed above are primarily explanatory rather than predictive in nature. The validity of predictions depends upon ceteris paribus conditions, which do not apply in open systems where social phenomena occur. Hence, “it is unrealistic to assume that all relevant data will be consistent with a theory even if the theory is correct” (Lieberson, 1992 : 7). As such, the predictive power of social science theories is curtailed (see Bhaskar, 1998 for a detailed discussion).

A Comparative Institutional Framework on GVCs

The above brief review of foundational works in GVCs and GPNs has clearly pointed to the general tendency in the social science literature to examine GVC governance, upgrading dynamics, and territorial outcomes. Still, there is a limited conceptualization of how different actors – from MNE lead firms to their strategic partners, key suppliers and customers, and other related firms – (1) structurally organize their business transactions to exercise control and coordination, determine locational choices, and configure networks; and (2) strategically manage their firm-specific activities to enhance learning and knowledge accumulation, create advantageous impacts, and orchestrate GVCs for better performance outcomes. These firm-specific considerations fall within the core premise and competence of IB research that can add much value to the existing GVC theoretical frameworks. In particular, we suggest that comparative institutional analysis can help link social science and IB approaches in GVC research. Comparative institutional analysis, as applied in firm-level studies, builds on the premise that economic actors will make decisions about the most efficient governance mechanisms to conduct economic exchange or to organize a given set of transactions. For example, they may choose between organizing production activities within the firm or through the market, and select coordination and control methods, such as the market system versus managerial hierarchy versus socialization (Gereffi et al., 2005 ; Hennart, 1993 ). Comparative institutional analysis has a number of branches, including internalization theory (Buckley & Casson, 1976 ), which is most relevant for exploring GVCs. Internalization theory applies the economic essence of comparative institutional analysis in an international setting, arguing that economic actors will select and retain the most efficient governance mechanisms to conduct cross-border transactions (Verbeke & Kenworthy, 2008 ).

From a comparative institutional perspective, a GVC represents a distinct form of governance, which is likely to emerge and thrive only if it enables superior efficiency when compared to other real-world alternatives (e.g., vertical integration or market contracting). Efficiency is served by aligning governance systems (both structural and strategic ) with the attributes of transactions in a cost-economizing way (Hennart, 1993 ). Ultimately, competitive advantage arises from the firm’s ability to choose the most efficient, economizing mix of internal and external contracts as a function of various micro - and macro - level characteristics of transactions – decisions made by economic actors at the micro level and demand/technological/institutional characteristics at the macro level (Antràs & Chor, 2013 ; Gereffi et al., 2005 ; Hennart, 1994 ). The most efficient governance forms are those that are comparatively superior in terms of enabling the firm to: (1) economize on bounded rationality; (2) economize on bounded reliability 2 ; and (3) create an organizational context conducive to innovation in its entirety (Verbeke & Kenworthy, 2008 ). Further, the firm must adjust its economizing mix of contracts over time as a function of changes in the micro- and macro-environments. Finally, the firm continually impacts both its micro-level and macro-level environments through changes in governance. Such changes evolve in a continuous, mutually reinforcing cycle (Williamson, 1996 ).

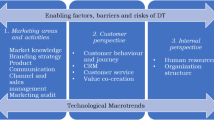

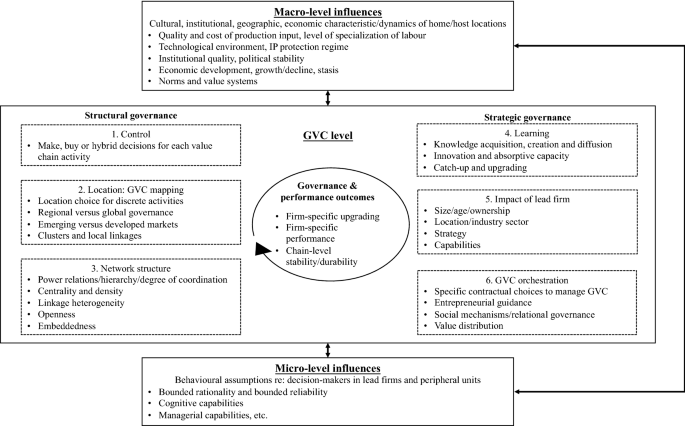

We combine comparative institutional logic with foundational GVC work discussed in the previous section to build an organizing framework, which facilitates our subsequent review of a large number of empirical and conceptual studies of GVCs. This framework, presented in Figure 1 , arranges extant studies along the three main layers impacting the functioning of GVCs, and conceptually connects these layers with each other and, ultimately, with GVC governance and performance outcomes. While incorporating some of the key conceptual variables in Gereffi et al.’s ( 2005 ) governance typology and Coe and Yeung’s ( 2015 ) GPN 2.0 theory, this integrative framework seeks to highlight IB - specific issues in relation to not only GVC-level variables, but also, crucially, micro- and macro-level influences that shape the organization and performance outcomes of MNEs and other firms in GVCs.

A comparative institutional framework of GVC governance.

First, at the micro - level , we identify studies that explore specific assumptions about the behavior of decision-makers in both the lead firm and peripheral units, and ways in which these assumptions explain processes within the GVC; that is, how knowledge is exchanged and processed, how the hazards of reliability are managed, and how new capabilities are developed and obsolete ones are discarded. Second, at the GVC level , we discuss studies that focus on governance and performance of the GVC. Here, we identify six broad dimensions that constitute critical elements of GVC governance: control, location, network structure, learning, impact of the lead firm, and GVC orchestration. GVC performance outcomes, to the extent that they are explored in the reviewed studies, are also addressed at this level. In accordance with comparative institutional analysis principles, and consistent with conceptual foundations of much GVC research, we view overall GVC performance in terms of sustainability of GVC as a governance form or its success in delivering value to participants, including capability development and upgrading. Third, at the macro - level , we focus on studies exploring the relationships between the GVC and its environment, including cultural, institutional, geographic, and economic make-ups of both home and host locations. Studies that constitute this group address both macro-level impacts on GVC configurations and the GVCs’ impact on macro-environments within which they operate. In the following sections, we use this integrative framework to review 87 conceptual and empirical studies of GVCs.

METHODOLOGY

We focused on published journal articles and excluded books, because more often than not, authors of books also published journal articles that contained much of the reported results (e.g., Gereffi, 2018 ). We also excluded book chapters, which usually went through a less rigorous review process than journal articles and were less accessible digitally. We conducted a multi-disciplinary literature search that covered IB, general management, supply chain management, operations management, and a selected group of social science journals that published GVC research, namely economic geography, economic sociology, regional and development studies, and international political economy 3 . This extensive scope should cover most of the key GVC studies published in academic journals. We included leading journals of each discipline that attracted researchers to submit their best-quality GVC studies.

For each journal, we searched articles published in the past 20 years – the period characterized by rapid growth and increased sophistication of GVC research, as discussed in the Introduction. We used four search terms: global value chain, global commodity chain, global production network, and global factory. We shortlisted conceptual articles with GVCs as their major foci, and empirical articles, whether qualitative or quantitative, that had at least one of the search terms as a major variable. That is, we excluded articles that casually cited or had any of the four terms serving as a control variable. Moreover, shortlisted studies targeted at the firm or network level, instead of other units of analysis, such as international organizations (e.g., Haworth’s ( 2013 ) case study of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation), industries, or locations.

Since the social science journals have a very large number of publications on GVCs that amounted to several hundreds, we applied additional criteria to narrow down this considerable volume of literature to a proportionate number of articles. We started with identifying nine theoretical pieces that constituted the foundation of the theory section above. For empirical papers, we implemented three additional screening criteria. First, we included more recent papers published after 2005. Second, we focused on papers that were closest to the research interests of IB scholars. Third, we ensured that our selection covered a reasonable mix of authors from different disciplines, institutions, and geographical locations, and that selected studies included both GVC and GPN approaches with a variety of research methods, industry coverage, and empirical locations in both developed and developing countries.

Based on the above criteria, a total of 21 journals publishing 22 theory papers (including the nine foundational pieces mentioned above) and 65 empirical articles were included in our review, as listed in Table 2 . Notably we also searched the Academy of Management Journal , Administrative Science Quarterly , Journal of Management and Management Science (all commonly regarded as leading management journals), but failed to find any relevant articles. The same applies to the leading journals in sociology (e.g., American Journal of Sociology and American Sociological Review ) and political sciences (e.g., American Political Science Review and International Organization ).

The 33 shortlisted articles in mainstream IB journals (i.e., GSJ, IBR, JIBS, JWB, and MIR) provide the most comprehensive picture of our field’s current state of knowledge on GVCs. Articles published in these journals, however, constitute about 58% of the group of non-social science journals, indicating that GVC is an important research topic attracting the attention of researchers working in disciplines beyond the IB turf. In the group of social science journals during the review period, GVC and GPN research has been particularly influential in the fields of economic geography, economic sociology, and regional and development studies. Here, we included only a small selection of 30 articles published in the leading journals, based on the criteria discussed above.

We studied each article and extracted two to three key GVC-related findings with respect to our organizing framework presented in Figure 1 . Table 3 lists these 87 articles’ key information (year of publication, authors, journal abbreviation, research method, and sample characteristics) and their most significant findings. The sample spans the time period from 1999 to the end of July 2019; however, for the non-social science journals, the more recent articles published after 2010 represent the bulk of the sample, reflecting a broad upward trend in GVC publications in the last decade. There is almost an equal split of research methods between qualitative case studies and quantitative studies based on archival or survey data. There are both single-country and multi-country studies, together covering a wide geographic scope. Most of the studies analyze firms, networks or clusters in manufacturing industries. It is not surprising that the automotive industry is the most popular context for these studies, given the industry’s requirement for many suppliers, large and small, manufacturing various components of an automotive. The studies as a whole investigate a variety of IB-related issues, as described in the next section.

REVIEW OF GVC LITERATURE

Micro-level: microfoundational assumptions and their impact on gvc.

Microfoundations refer to generic human behavioral conditions that impact firm-level (and, in the case of GVCs, network-level) outcomes (Kano & Verbeke, 2019 ). Scholars have argued that individual-level characteristics, such as bounded rationality, bounded reliability, cognitive biases, and entrepreneurial orientation, impact GVC governance (Denicolai, Strange, & Zucchella, 2015 ; Kano, 2018 ; Levy, 1995 ; Verbeke & Kano, 2016 ), in terms of how transactions are organized and orchestrated. Therefore, systematic attention to microfoundations is necessary in order to meaningfully advance the GVC research agenda. However, few empirical studies directly observe or measure individual-level variables. Further, while certain behavioral assumptions are frequently implied – e.g., the nature of individual-level knowledge and capabilities is inherent in the idea of learning and upgrading; the need for knowledge sharing across units implies bounded rationality of individual actors and associated information asymmetries; the notions of power balance and the need for intellectual property (IP) protection assume a certain level of bounded reliability of actors involved – these assumptions are, for the most part, neither articulated explicitly nor examined empirically.

Only seven studies in our sample directly address the impact of microfoundations (either stated or implied) on GVC geographic configurations, knowledge acquisition and dissemination within the GVC network, and efficient functioning and orchestration of the network. In an early qualitative study of supply chain management, Akkermans, Bogerd and Vos ( 1999 ) discuss how bounded rationality, as expressed in supply chain partners’ diverging beliefs and goals, contributes to functional silos and erects barriers to effective value chain management. Lipparini, Lorenzoni and Ferriani ( 2014 ) argue that GVC networks that benefit the most from knowledge transfer among partners are those where partners share common identity and language. These features serve as safeguards against the potential threat of opportunism and allow participating firms to learn from partners with reduced risk of proprietary knowledge spillover outside of the immediate network. Eriksson, Nummella and Saarenketo ( 2014 ) suggest that individual-level cognitive and managerial capabilities of lead firm managers, such as cultural awareness, entrepreneurial orientation, global mindset, interface competences and analytical capabilities, constitute a critical building block for firm-level ability to successfully orchestrate cross-border transactions in a GVC. Seppälä, Kenney and Ali-Yrkkö (2018) focus on boundedly rational accounting decisions in lead MNEs, and argue that lead firms’ accounting systems may misrepresent where the most value is created in a GVC. This mismatch implies that GVC activities to which value is allocated may be selected somewhat arbitrarily, and this further impacts location decisions. Kano ( 2018 ) argues that bounded rationality and reliability of decision-makers in participating firms impact the efficiency of the GVC; as such, the role of lead firm managers is to control bounded rationality and reliability through a mix of relational mechanisms, so as to improve the likelihood that the GVC will be sustainable over time. Treiblmaier ( 2018 ) theoretically predicts structural and managerial changes introduced into GVCs by blockchain technologies, by analyzing four behavioral assumptions of major economic theories: bounded rationality, opportunism, goal conflict, and trust. Finally, Sinkovics, Choksy, Sinkovics and Mudambi ( 2019 : 151) explore the relationship between three variables – information complexity, information codifiability, and supplier capabilities – and knowledge connectivity in a GVC, and conclude that individual characteristics of lead firm managers – specifically, their risk perceptions and associated “comfort zones” – moderate this relationship.

GVC Level: Components of GVC Governance

The term “governance” refers to the organizational framework within which economic exchange takes place, including the processes associated with the exchange (Zaheer & Venkatraman, 1995 ). In the context of a GVC, governance includes the overarching principles, structures and decision making processes that guide the “checks and balances” in network functioning, so as to make sure that the interests of the entire network (and broader societal/environmental interests where relevant) are served above and beyond localized interests of participating firms and individual decision-makers within these firms. These principles, structures and processes encompass considerations related to boundaries of the network and its geographic make-up, control and orchestration mechanisms for economic activities performed within the GVC, value distribution, relationship management, and direction of knowledge flows. Outcomes of successful governance include meeting of individual participants’ performance goals, as well as, ultimately, long-term sustainability of the GVC as a whole.

Here, a distinction can be made between structural and strategic governance of the GVC, as shown in Figure 1 . The former refers to the actual structure governing economic activities, e.g., make versus buy decisions, organizational structure of the network (number of players, power balance, boundaries, etc.), geographic and functional allocation of activities, level of centralization of decision-making, and so on. In contrast, strategic governance is concerned with dynamics of actors’ behavior in respect to strategic decision making (Schmidt & Brauer, 2006 ; Zaheer & Venkatraman, 1995 ). In the context of GVCs, strategic governance is about orchestrating the usage of resources, through codified and uncodified routines and managerial practices, to ensure smooth functioning of the entire network (Kano, 2018 ). Our review identified six broad, interrelated conceptual dimensions (Figure 1 ) that constitute critical elements of structural and strategic governance of a GVC. These dimensions, as well as outcomes of governance practices, are discussed below.

Control decisions establish the governance structure of the GVC, that is, whether each value chain activity should be internalized, outsourced, or controlled through hybrid forms such as joint ventures (JVs) (Buckley et al., 2019 ). It has been argued that in a GVC, control of critical knowledge and intangible assets (e.g., brand names and technological platforms) takes precedence over ownership of physical assets (Buckley, 2011 , 2014 ; Mudambi, 2008 ), and ownership advantages can be exploited without internalizing operations (Strange & Newton, 2006 ). This core premise underlying the GVC is supported in Hillemann and Gestrin’s ( 2016 ) analysis of OECD data on foreign direct investment (FDI) and cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&As), which shows that cross-border financial flows related to intangible assets continue to increase relative to those related to tangible assets. An analysis of about 25,000 Italian firms also suggests that control of GVC activities, as compared to ownership, yields benefits in terms of greater propensity toward innovation, increased productivity, and faster sales growth (Brancati, Brancati, & Maresca, 2017 ). The preference for control without ownership is enabled by increasing digital connectivity, which allows lead firms to influence various units in the GVC without directly managing them (Foster, Graham, Mann, Waema, & Friederici, 2018 ).

To some extent, control decisions are impacted by host countries’ regulatory environments, particularly when national political institutions create pressure for local content on MNEs that are trying to gain access to large downstream markets in emerging economies (Lund-Thomsen & Coe, 2015 ; Morris & Staritz, 2014 ; Sturgeon, Van Biesebroeck, & Gereffi, 2008 ). This is the case with “obligated embeddedness” (Liu & Dicken, 2006 : 1238) of automotive MNEs in China, where the government’s industrial policy dictates that inward FDI should take a JV form. Further, control decisions are linked to sectoral and functional factors – for example, lead MNEs operating in high- and medium-technology sectors and/or locating knowledge-intensive functions (e.g., innovation) in host markets are more likely to pursue ownership in jurisdictions that offer weaker IP protection (Ascani, Crescenzi, & Iammarino, 2016 ). Ownership allows the MNE to have better control over the creation, transfer and leakage of propriety knowledge, and is thus a pre-emptive measure for knowledge protection.

However, considerable heterogeneity in control decisions exists among lead firms operating in the same geographic regions and industry sectors, which suggests that firm-level strategic considerations, and not only macro-level forces, are powerful drivers of control patterns in GVCs (Dallas, 2015 ; Sako & Zylberberg, 2019 ). These considerations include lead firms’ levels of specialization, the nature of their relationships with partners, the need for flexibility versus stability in offshore operations, and the value of the operations to the lead firm (Amendolagine, Presbitero, Rabellotti, & Sanfilippo, 2019 ; Dallas, 2015 ; Kleibert, 2016 ). Control decisions can be also driven by the level of local adaptation required, whereby the lead MNE may need to source external expertise in order to perform the desired degree of customization. Here, a carefully designed mix of internalized and externalized, yet managerially or technologically linked, activities is argued to allow the lead firm to achieve the ultimate balance between integration and responsiveness (Buckley, 2014 ).

Location decisions determine the most advantageous geographical configuration of the GVC, namely, where activities should be located, and how they should be distributed in order to maximize the value created in and captured through the GVC. Location decisions encompass such considerations as the regional effect (Rugman & Verbeke, 2004 ), the nature of industrial clusters (Turkina & Van Assche, 2018 ), and the links between GVCs and local clusters. Location decisions are tightly intertwined with control decisions discussed earlier. For example, FDI (as opposed to market contracting) enables the MNE to construct a regional, or even global, network under its control to supply wide-ranging, differentiated and low cost products in a flexible manner. Chen’s ( 2003 ) study of electronics firms in Taiwan indicates that FDI often starts at a location close to the home base, where resources from domestic networks can be drawn, and subsequently moves on to more distant locations, after the lead firm has developed a regional sub-network to support its further expansion.

Location considerations are linked to macro-level characteristics of host and home countries, including level of economic development and corresponding factors such as cost of labor, technological environment, and institutional quality. Among these factors, favorable business regulations, IP protection, and significant education spending typically attract technologically and functionally sophisticated activities (Amendolagine et al., 2019 ; Ascani et al., 2016 ; Pipkin & Fuentes, 2017 ). Control of the GVC resides in the hands of technology and/or market leaders, which are typically (although not always) located in developed economies and extract value from their GVCs through global orchestration capabilities (Buckley & Tian, 2017 ). Countries with more advanced production technologies are naturally engaged more in the upstream segments of the GVC, and become key suppliers to other countries in the region, thus supporting regional integration of production (Amendolagine et al., 2019 ; Suder, Liesch, Inomata, Mihailova, & Meng, 2015 ).

Most empirical studies address location of production activities, whereby labor cost emerges as one of the core determinants for GVCs led by both advanced economy MNEs (AMNEs) and emerging economy MNEs (EMNEs). For example, Asian tier 1 suppliers to MNEs and OEMs become GVC lead firms in their own right by shifting production to lower cost locations in the region (Azmeh & Nadvi, 2014 ; Chen, Wei, Hu, & Muralidharan, 2016 ). Yet efficiency-seeking offshoring may create strategic issues, particularly when inefficient local institutions fail to prevent unwanted knowledge dissipation. Issues can also emerge on the demand side due to sustainability and ethical breaches in large MNEs’ value chains, as evidenced in multiple, recent instances of public backlash in response to poor working conditions in manufacturing factories in South and Southeast Asia (Malesky & Mosley, 2018 ). Funk et al.’s ( 2010 ) survey of US consumers suggests that developed economy consumers’ willingness to purchase is negatively affected by partial production shifts to animosity-invoking countries (countries with poor human rights records/with poor diplomatic relationships with the home country). As the wave of consumer movement spreads to less developed countries, it is in the best interest of the lead firm to evaluate carefully the undesirable attributes of a potential host country when making FDI decisions (Amendolagine et al., 2019 ; Morris & Staritz, 2014 ).

Desire to access large and fast-growing consumer markets drives production activities close to end markets, for example, when host country governments in emerging markets pressure MNEs for local operations (Sturgeon et al., 2008 ). Co-location of manufacturing and sales also allows lead firms to be more responsive to customer demands, and to off-set the costs of globally dispersed activities by reducing investment in transportation and logistics (Lampel & Giachetti, 2013 ).

Strategic asset seeking by lead firms and suppliers explains much of the geographic configuration of GVCs, whereby MNEs locate value chain activities in globally specialized units to exploit international division of labor (Asmussen, Pedersen, & Petersen, 2007 ). This is particularly pronounced in knowledge-intensive industries, where lead firms often locate operations in innovation hubs and global cities (Taylor, Derudder, Faulconbridge, Hoyler, & Ni, 2014 ). In their analysis of clusters in the aerospace, biopharma, and ICT industries, Turkina and Van Assche ( 2018 ) demonstrate that innovation in knowledge-intensive clusters benefits from horizontal connection to global hotspots, as opposed to labor-intensive clusters where innovation gains from vertical GVC connections.

While much has been written about fine-slicing and fragmentation of value chain activities in a GVC (Buckley, 2009a , b ), few empirical studies measure the costs and benefits of geographic diversification of operations within the same part of the value chain. Lampel and Giachetti ( 2013 ) address a relationship between international diversification of manufacturing and financial performance in the context of the global automotive industry, and find an inverted U-shaped relationship, whereby advantages of diversified manufacturing (i.e., greater flexibility and access to internationally dispersed strategic resources) are eventually off-set by increased organizational complexity and managerial inefficiencies. Further, location decisions are tied to firms’ strategic priorities beyond cost reduction – for example, increased needs for customer responsiveness and/or enhanced quality control. Focus on such priorities may prompt backshoring initiatives (Ancarani, Di Mauro, & Mascali, 2019 ). Yet, geographic diversification may serve strategic purposes such as IP protection. Gooris and Peeters’ ( 2016 ) survey of offshore service production units demonstrates that lead firms may opt to fragment their global business processes across multiple service production units, rather than co-locating processes, with the explicit purpose of reducing the hazard of knowledge misappropriation.

Finally, technological advances continue to shape geographic make-up of GVCs (MacCarthy, Blome, Olhager, Srai, & Zhao, 2016 ). Few studies in our sample measure the impact of digital technologies on location choice, but several studies address current and potential influences of technology indirectly and/or conceptually. Ancarani et al. ( 2019 ) suggest that adoption of labor-saving technologies leads to backshoring in instances when lead firms compete on quality, rather than on cost. While digital connectivity enables exploiting complementarities between geographically dispersed processes (Gooris & Peeters, 2016 ), it may limit participation by suppliers located in technologically underdeveloped regions (Foster et al., 2018 ). Further, the latest technology, such as 3D printing, is likely to impact GVCs of relevant industries by making them shorter, more dispersed, more local, and closer to end users (Laplume et al., 2016 ; Rehnberg & Ponte, 2018 ).

Network structure

Network structure refers to the structural make-up of a GVC and has been well theorized in some of the most cited GVC conceptual frameworks (e.g., Coe & Yeung, 2015 ; Gereffi, 2018 ; Gereffi et al., 2005 ; Henderson et al., 2002 ). While a GVC can typically be conceptualized as an asymmetrical or high centrality network with a lead firm at its centre (Kano, 2018 ), these networks can also be heterogeneous in terms of such characteristics as depth, density, openness, and the presence of structural holes (Capaldo, 2007 ; Rowley, 1997 ). These characteristics affect power relations in the GVC, the level of control afforded to the lead firm, and innovation and business performance. Not surprisingly, a large number of empirical studies in our review address various dimensions of the nature and/or role of network structures in GVC governance and performance outcomes.

The network structure in a typical GVC can be dyadic or multi-actor in nature, and can affect knowledge flows (Lipparini et al., 2014 ), new venture formation (Carnovale & Yeniyurt, 2014 ), and operational performance (Golini, Deflorin, & Scherrer, 2016 ). A firm with high centrality (i.e., most links in a network) has greater power over other firms in a dyadic or multi-actor network, whereby control can be exerted by the lead firm beyond its legal boundaries over independent – but captive – suppliers (Yamin, 2011 ). In supply chain management, Carnovale and Yeniyurt’s ( 2014 ) study of automotive OEMs and automotive parts suppliers shows that manufacturing JV formation between lead firms and potential partners can be enhanced by higher network centrality of either the lead firm or the potential JV partner. This network centrality is seen as a proxy for greater legitimacy and credibility within the network. However, the study found mixed outcomes in relation to network density. High network density is not necessarily favorable to new JV formation due to “lock-in” effects through structural homophily. This network structure in turn limits access of lead firms to a diverse set of potential partners and hinders learning and innovation. Similarly, the studies of manufacturing plants in various countries by Golini et al. ( 2016 ) and Golini and Gualandris ( 2018 ) demonstrate that a higher level of external supply chain integration (e.g., through GVC activities) can improve the operational performance of and the adoption of sustainable production by manufacturing MNEs due to information sharing, learning, and innovation through supply chain partners.

The density of network structure in GVCs, however, may change over time in relation to the emergence of new technologies and platforms, some of which may favor greater density in localized networks. In their perspective article on 3D printing and GVCs, Laplume et al. ( 2016 ) question if technological advancements can influence the relative density of globally dispersed and localized production networks. As more local firms can participate in the production of high-value components through 3D printing, their need for technological acquisition and/or specialized components through MNE lead firms in GVCs may be reduced, leading to what Rehnberg and Ponte ( 2018 ) call “unbundling” and “rebundling” of GVC activities towards regionalized or even localized GVCs. In this scenario for decentralized GVC network structure, local producers can engage in more transactions with each other, and thus localized production networks may get denser over time.

In addition to centrality and density, network structures in GVCs can also be distinguished by linkage heterogeneity – the mix of horizontal linkages (between firms with similar value chain specialization) and vertical MNE-supplier linkages (with different value chain specialization). This structural mix has significant influence on the innovation performance of firms in different industries (Amendolagine et al., 2019 ; Brancati et al., 2017 ). Drawing on a social network approach, Turkina and Van Assche’s ( 2018 ) study of industrial clusters shows that network structures underpinned by dense horizontal linkages among local firms tend to enhance innovation performance in knowledge-intensive industries, whereas strong vertical linkages between local firms and MNEs can promote innovation in labor-intensive clusters. The former network structure tends to promote innovation through intra-task knowledge capability development among horizontally linked firms. As to the latter case of local suppliers in labor-intensive industries, inter-task capability development can be better served through vertical and international linkages with global lead firms.

Finally, power relations among GVC actors play out very differently in different network structures (Dallas, Ponte, & Sturgeon, 2019 ; Grabs & Ponte, 2019 ). In one of the earliest studies of industrial upgrading through GVC participation, Humphrey and Schmitz ( 2002 ) observed that network structures characterized by quasi-hierarchical power relations in favor of one party – often global lead firms or global buyers – were generally not conducive to the upgrading of local firms. Sturgeon et al. ( 2008 ) followed up with this line of research by examining major American and Japanese automotive lead firms and over 150 suppliers in North America. They found that upgrading of local suppliers was more likely if the GVC network structure moved towards a relational form of power dynamics. Such a relational form of network structure tends to favor inter-firm cooperation and credible commitment (e.g., IKEA and its suppliers in Ivarsson & Alvstam, 2011 and tuna canning firms in Havice & Campling, 2017 ). Similarly, Khan, Lew and Sinkovics’s ( 2015 ) study of the Pakistani automotive industry shows that local firms are more likely to acquire technological know-how and develop new capabilities by participating in geographically dispersed rather than locally oriented networks. Through international JVs (IJVs) with global lead firms, these local firms can access different knowledge base and know-how in those international networks.

As noted earlier, network structures are embedded in different national and institutional contexts. Pipkin & Fuentes ( 2017 ) find that domestic institutional environment, such as state policies and support from business associations, is more significant than lead firms’ influence in shaping network dynamics in developing countries. Horner and Murphy’s ( 2018 ) study of manufacturing firms in India’s pharmaceutical industry shows that network structures characterized by firms from similar national contexts (e.g., the Global South) can be more open and cooperative in relation to production and quality standards, market access, and innovation. This greater openness in South–South GVCs entails different business practices toward their end markets due to lower entry barriers, lower margins, and higher volumes. The opportunities for learning in these GVCs are also different from those tightly controlled and coordinated by lead firms from the Global North. Another study of chocolate GVCs in Indonesia by Neilson, Pritchard, Fold and Dwiartama ( 2018 ) also points to the importance of contextual heterogeneity in shaping the influence of different network structures on lead firm behavior and relationships with suppliers and distributors. Drawing upon Yeung and Coe’s ( 2015 ) GPN 2.0 theory, Neilson et al. ( 2018 ) argue that network structures differ significantly between branded chocolate manufacturing and cocoa farming/processing in agrofood manufacturing. Owing to domestic industrial policy and international business lobbying, the role of national context is much more pronounced in the network structure of cocoa farming/processing that favors inter-firm partnership and cooperative learning.

Conceptual studies have identified knowledge diffusion and transfer as an important aspect of network governance (Ernst & Kim, 2002 ; Inkpen & Tsang, 2005 ). Empirical studies take note of this topic and examine various dimensions of learning in a GVC. Most of such studies in our sample focus on interfirm learning in the context of capability development, technological catch-up and upgrading by peripheral GVC actors – that is, emerging economy suppliers’ progression from OEM to original design manufacturing (ODM) and to own brand manufacturing (OBM). As touched upon in the previous section, macro-level conditions such as market forces and state policies, rather than lead firm initiatives, are argued to be the main force in spurring supplier upgrading (Pipkin & Fuentes, 2017 ). Upgrading initiatives can produce a wide range of results, from incremental to significant leaps in market position (Pipkin & Fuentes, 2017 ), depending on a number of factors. Eng and Spickett-Jones ( 2009 ) argue that upgrading hinges on suppliers’ ability to simultaneously develop three sets of marketing capabilities: product development, marketing communication, and channel management. Wang, Wei, Liu, Wang and Lin’s ( 2014 ) study of manufacturing firms in China indicates that the presence of MNEs alone does not guarantee knowledge spillovers, and may in fact have a negative impact on indigenous firms’ domestic performance due to increased competition. Hatani ( 2009 ) describes barriers to learning by emerging market GVC suppliers. Her study of autoparts suppliers in China suggests that excessive inward FDI limits interactions between lead firms and local suppliers and thus creates structural obstacles to technology spillovers to lower GVC tiers. Also researching the autoparts industry (but in Argentina rather than China), McDermott and Corredoira ( 2010 ) suggest that supplier upgrading is facilitated by regular, disciplined discussions with the lead firm about product and process improvement; in this context, a limited amount of direct social ties to international assemblers appears to be the most beneficial.

In a follow-up study, Corredoira and McDermott ( 2014 ) find that lead firms alone do not help process upgrading, but add value particularly when emerging market suppliers’ ties to MNEs are augmented with multiple, strong ties to non-market institutions (e.g., universities and business associations), which act as knowledge-bridgers and help suppliers tap into knowledge embedded in the home country. These types of ties are particularly useful for accessing knowledge for the development of exploitative innovation, while exploratory innovation is best achieved through participation in trade fairs and collaboration with international (rather than domestic) institutions, according to the study of Pakistani motorcycle part suppliers by Khan, Rao-Nicholson and Tarba ( 2018 ). Similarly, Jean’s ( 2014 ) study of new technology ventures in China indicates that firms that participate in trade shows and have strong quality control practices are more likely to develop requisite knowledge to pursue upgrading, while firms engaging in Internet-based business-to-business transactions are less likely to upgrade. Based on their studies of the garment and toy industries, Azmeh and Nadvi ( 2014 ) as well as Chen et al. ( 2016 ) describe alternative paths to upgrading: some OEMs invest in R&D to enter the ODM business, or invest in marketing and branding and move toward the downstream end of the value chain to become OBMs. Others achieve competitive gains by shifting production to different locations and learning how to effectively coordinate multiple production locations (see also detailed case studies of ODMs from Taiwan and Singapore and OBMs from South Korea in Yeung, 2016 ). Buckley ( 2009b ) suggests that both options – incremental upgrading within the established GVC and developing a new GVC under local control – are difficult in that they require mobilization of entrepreneurial abilities and development of sophisticated managerial skills. Successful upgrading hinges not only on suppliers’ acquisition of knowledge, but also on their ability to absorb it and transform it into innovation, which ultimately improves suppliers’ position in GVCs (Khan et al., 2019 ).

Specific knowledge acquisition strategies required for upgrading vary depending on the nature of home institutions and labor markets (Barrientos, Knorringa, Evers, Visser, & Opondo, 2016 ; Pipkin & Fuentes, 2017 ; Werner, 2012 ). Weak home institutions hinder the transformation of knowledge into actual innovative products and processes (Jean, 2014 ). This explains why catch-up and upgrading by GVC suppliers often mirrors the evolution of home institutions (Kumaraswamy, Mudambi, Saranga, & Tripathy, 2012 ): as institutions evolve toward liberalization, upgrading strategies change from upgrading technical competencies through licensing and collaborations, to upgrading internal R&D and developing strong relationships with lead firms. The weakness of local institutions can be overcome by gaining knowledge through participation in international networks and collaboration with global suppliers (Khan et al., 2018 ).

The nature of relationship among parties in GVCs matters for technological knowledge transfer, as network ties are channels through which knowledge flows. Khan et al.’s ( 2015 ) above-mentioned study indicates that IJVs represent a governance vehicle that facilitates the creation of social capital between focal MNEs and automotive parts suppliers located in emerging economies, and thus facilitate development and acquisition of complex technological knowledge by local firms.

Learning and knowledge accumulation and diffusion in the lead firm, as well as lead-firm initiated network-wide learning, garnered significantly less scholarly attention, with one notable exception. Through analyzing Italian motorcycle industry projects carried out via dyads of buyers and suppliers, Lipparini et al. ( 2014 ) develop a framework that addresses multi-directional, multilevel and multiphase knowledge flows in a GVC, and describe practices implemented by lead firms to successfully cultivate creation, transfer and recombination of specialized knowledge to facilitate network-wide learning. In such a dynamic and somewhat open context of knowledge sharing, the threat of opportunism is likely to be outweighed by the advantages of learning from other network members.

There appears to be consensus in the literature that strong linkages within the GVC – frequently referred to as embeddedness of actors in the network (Henderson et al., 2002 ) – are conducive to transferring various types of knowledge, including production processes, sourcing practices, technological knowledge, and innovation capabilities (Golini et al., 2016 ; Golini & Gualandris, 2018 ; Ivarsson & Alvstam, 2011 ). Such linkages are the most effective when purposefully facilitated by strong lead firms. Lead firms can impel capability upgrading on peripheral units by leveraging their central positions and complementary assets, as indicated by the acquisition of UK-based Dynex by China’s Times Electric (He, Khan, & Shenkar, 2018 ). Ivarsson and Alvstam’s ( 2011 ) case study of IKEA and its suppliers in China and Southeast Asia similarly shows that lead firms can contribute to peripheral units’ upgrading by fostering close, long-term interactions, and by offering technological support. Conversely, weak strategic coupling between lead firms and peripheral units hurts knowledge transfer and capability development (Yeung, 2016 ). For example, Pavlínek’s ( 2018 ) study of automotive firms in Slovakia suggests that weak and dependent supplier linkages between MNEs and domestic firms undermine the potential for technology and knowledge transfer from the former to the domestic economy.

Lead firms are often motivated to drive their suppliers’ capability upgrading, because they themselves benefit from suppliers’ enhanced capabilities through improved sourcing efficiency, higher-quality inputs, and more generally valuable knowledge diffusion throughout the GVC. In the next section, we discuss how characteristics of the lead firm impact its position and role in the GVC.

Impact of lead firm

Extant conceptual research has acknowledged that smooth and efficient functioning of the GVC is contingent on the lead firm’s ability to establish, coordinate and lead the network (Kano, 2018 ; Yamin, 2011 ; Yeung, 2016 ; Yeung & Coe, 2015 ). Buckley ( 2009a ) argues that the role of headquarters is more important in a GVC than in a conventional hierarchical MNE, because leading a GVC demands specific management capabilities such as the ability to fine-slice the value chain, control information, and coordinate strategies of external organizations. Yet few studies directly investigate the specific impact of lead firm characteristics on the boundaries, configurations and performance of the GVC. The studies that do use lead firm features as independent variables focus on such aspects of the lead firm as size (small versus large), industry sector (and associated sector-specific value chain strategies), location (headquarters location in a particular region/in emerging versus developed markets, and proximity to clusters), and technological leadership.

Lead firm size appears to be seen as a proxy for power and influence in a network. Eriksson et al. ( 2014 ), in a case study of a Finnish high-tech SME at the centre of a globally dispersed value chain, argue that SMEs face additional liabilities of smallness and newness when managing a GVC, and suggest that in order to manage successfully a GVC over the long term, the SME must develop three distinct yet related sets of dynamic capabilities: cognitive, managerial, and organizational. Dallas ( 2015 ) takes a finer-grained view of firm size as a determinant of GVC management strategy. While his analysis of transactional data of Chinese electronics/light industry firms uses size as a control, rather than independent, variable, he concludes that ways in which GVCs are organized vary not simply by lead firm size and productivity, but also by other heterogeneous firm level features, such as distinct governance channels available to lead firms. Dallas ( 2015 ) thus cautions GVC researchers not to make assumptions about the distinctiveness of large lead firms as a group, and to focus on other potential sources of heterogeneity, which can be linked to sector-specific features as well as firm-level strategies.

One of such sources of heterogeneity appears to be the level of economic development of home country, dichotomized in some GVC papers as emerging versus advanced. Two studies explore differences in GVCs led by EMNEs versus AMNEs. He et al. ( 2018 ), based on a case analysis of China’s Times Electric-led GVC, argue that power relationships in the GVC seem to be more balanced when EMNEs, rather than AMNEs, are in lead positions. Buckley and Tian ( 2017 ) compare internationalization patterns of top non-financial EMNEs and AMNEs, and find that AMNEs are more likely to achieve profitability through global GVC orchestration, while EMNEs’ ability to develop orchestration know-how is restricted by home institutions. Therefore, EMNEs are more likely to extract monopoly-based rents from internationalization, but to remain constrained to the periphery position in GVCs.

It follows, then, that control of the GVC is likely to remain in the hands of technology leaders (Buckley & Tian, 2017 ). Jacobides and Tae ( 2015 ) describe such technology leaders as “kingpins,” operationalized as firms with superior market capitalization and comparatively high R&D investment. In their study of firms active in various segments in the US computer industry, the authors show that “kingpins” impact value distribution and migration through the value chain. Technological and R&D capabilities, however, need to be accompanied by global orchestration know-how in order for lead firms to achieve profitability from fragmented, globally dispersed operations (Buckley & Tian, 2017 ). We address GVC orchestration in the next section.

GVC orchestration

Orchestration refers to decisions and actions by lead firm managers – a managerial toolkit – aimed at connecting, coordinating, leading, and serving GVC partners, and ultimately shaping the network’s strategy (Rugman & D’Cruz, 1997 ). Orchestration encompasses such elements as, inter alia , formal and informal components of each relationship within the network, the entrepreneurial element of resource bundling, interest alignment among parties achieved through strategic leadership by the lead firm, knowledge management 4 , and value distribution.

Formal orchestration tools – that is, codified rules, specific contractual choices to manage partner relationships, and price-like incentives and penalties – are typically easier to observe and operationalize than informal tools such as social mechanisms deployed by lead firms to govern relationships. Yet, only a few studies in our sample investigate contractual choices in a GVC. Lojacono, Misani and Tallman ( 2017 ) examine nuances of cooperative governance in the dispersed value chain of the home appliances industry, and find that more complex transactions requiring greater coordination are more likely to be governed through equity participation. Specifically, non-equity contracts are more efficient for coordinating offshore production, while equity JVs are preferable for managing local strategic relationships, such as production alliances whose primary objective is to serve local markets. Chiarvesio and Di Maria ( 2009 ) explore differences in GVC orchestration between lead firms located within industrial districts versus those located outside. Their quantitative study of Italian firms active in the country’s four dominant industries – furniture, engineering, fashion, and food – shows that there are subtle differences in ways district and non-district lead firms manage their GVCs to achieve optimal efficiency: while lead firms located within industrial districts rely more on local systems through subcontracting networks, non-district firms invest in national level subcontracting. Here, local subcontracting networks allow lead firms to exploit flexibility, and national subcontracting facilitates greater efficiency and acquisition of value-added competences through the GVC. Of note, these differences decrease as firm size increases. Finally, Enderwick ( 2018 ) conceptually studies responsibility boundaries in a GVC, and argues that the full extent of lead firm responsibility for actions of indirect GVC participants depends on whether indirect partners’ contracts are exclusive or non-exclusive.