Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Oncology — Prostate Cancer

Essay Examples on Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer: practice essentials, background, anatomy, family genetics and associated risks of developing prostate cancer, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Vitamin D for Human Body

Relevant topics.

- Breast Cancer

- Ovarian Cancer

- Skin Cancer

- Mental Health

- Eating Disorders

- Affordable Care Act

- Healthy Food

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Prostate cancer

Learn more about prostate cancer from Mayo Clinic urologist Mitchell Humphreys, M.D.

Hi. I'm Dr. Humphreys, a urologist at Mayo Clinic. In this video, we'll cover the basics of prostate cancer: What is it? Who gets it? The symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. Whether you're looking for answers about your own health or that of someone you love, we're here to provide you with the best information available. Prostate cancer, unfortunately, is common. It affects one in seven men, making it the second most common cancer among men worldwide. The good news is, is that prostate cancer can be curable, especially when identified and treated early. That is why I and most urologists and medical professionals you talk to encourage men over a certain age to get regular prostate screenings. First, let's talk about what the prostate is and how it functions. The prostate is a small gland that is involved in reproduction and makes some of the essential components in semen. While it is small, it has an important role in reproductive health and can cause voiding or urinary symptoms as men age, as well becoming a source of cancer. Like other kinds of cancer, prostate cancer starts when cells mutate. These small changes in DNA cause the cells to grow faster and live longer than they normally would. As these abnormal cells accumulate, they monopolize resources from normal cells, which can damage surrounding tissue. These cancerous cells can then spread to other parts of the body.

By definition, prostate cancer only affects bodies with male reproductive organs. But in addition, there are some other risk factors that we can monitor. Age is a big one, as prostate cancer is more prevalent in older men, which is why testing is encouraged as men age. For reasons that are unclear, Black men also have a greater risk compared to other races or ethnicities. Being at a higher weight as another possible risk factor. Genetics can also play a role in prostate cancer. A family history of prostate cancer or certain kinds of breast cancer increases the likelihood of being diagnosed with prostate cancer. Well, it's not a guarantee, there are plenty of steps you can take to reduce your risk. A healthy diet and exercise helps your body's overall well-being and can lower your chances of getting prostate cancer.

A big reason to get regular testing is that prostate cancer usually has no presenting symptoms. And when they do show up, it generally indicates a worse stage of cancer. When symptoms do occur, they can include: trouble urinating or decreased force of stream, blood in the urine or semen, bone pain, unexpected weight loss, and unexplained fevers. If you consistently notice any of these symptoms, you should see your doctor right away. How is it diagnosed? There are a variety of ways to detect prostate cancer in both physical exam and from the blood. For starters, there's the DRE, the digital rectal exam. Just like the name suggests, the doctor inserts their finger and your rectum to feel the prostate to detect any abnormalities. You can also get a blood test to look for prostate-specific antigen, or PSA. It is recommended that you have this as well as the physical exam. And if there are any abnormalities, there are additional tests that can be used. If prostate cancer is detected, the next step is figuring out how fast it grows. Fortunately, prostate cancer often doesn't grow very fast. Prostate cancer is graded by a Gleason score, which measures how abnormal or different from normal cells are. There are also other tests to see if the cancer has spread: bone scan, CT scan, MRI, and even specific PET scans. Your doctor will be able to determine which, if any, is appropriate for you.

Treatments are most effective when the cancer is caught early. In fact, immediate treatment isn't always necessary. Keeping an eye on the cancer until it grows bigger is sometimes enough. When cancer is localized only to the prostate, surgery to remove the prostate, or a radical prostatectomy, could be your best option. Radiation is another possibility. With external beam radiation, high-energy beams that deliver photons, target and kill the abnormal cells of the prostate from outside your body. Another treatment is chemotherapy, which uses powerful chemicals, destroy the cancer cells. Cryotherapy, which freezes the cancer cells, or heat, can be used to kill the cancer cells with high-intensity focused ultrasound. Consider that prostate cancer uses male hormone or testosterone as an important factor for growth. In some prostate cancers, it may be beneficial to block that hormone with androgen deprivation therapy, or ADT, which can slow the cancer or even put it in remission. It is generally not curative and usually the cancer will find a way to grow even with the lack of testosterone. Sometimes ADT is used in combination to enhance the treatment success of other therapies, such as with radiation. All of these treatments have side effects of various degrees and have different success rates of treating prostate cancer. It's important that you have a candid discussion with your family and your care team and weigh all that information to make the best choice for you. Support groups for cancer survivors can be helpful in dealing with the stress of the diagnosis and treatments.

As we've seen here, research and scientific advancement has provided us with a host of options for this extremely treatable form of cancer. And with early detection, your chances are even better. While it may not be a thing people want to think about, it's an important part of your health and an expert medical care team can guide you to the solutions that are most tailored for you, your wishes and your body. If you'd like to learn even more about prostate cancer, watch our other related videos or visit mayoclinic.org. We wish you well.

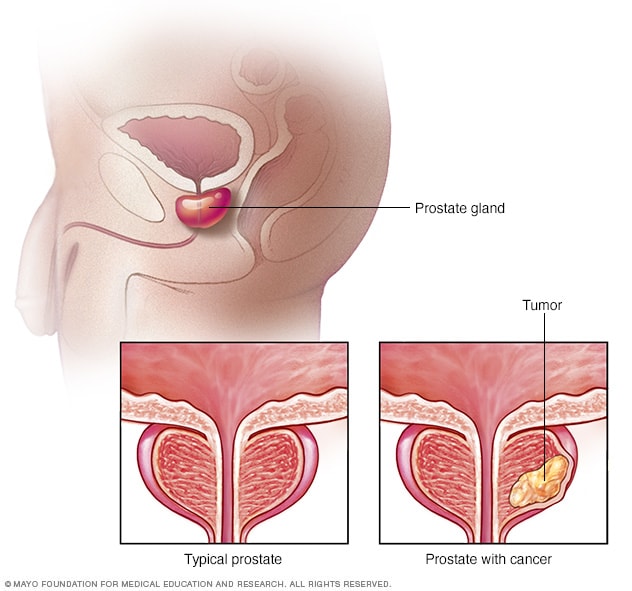

Prostate cancer occurs in the prostate gland. The gland sits just below the bladder in males. It surrounds the top part of the tube that drains urine from the bladder, called the urethra. This illustration shows a healthy prostate gland and a prostate gland with cancer.

Prostate cancer is cancer that occurs in the prostate. The prostate is a small walnut-shaped gland in males that produces the seminal fluid that nourishes and transports sperm.

Prostate cancer is one of the most common types of cancer. Many prostate cancers grow slowly and are confined to the prostate gland, where they may not cause serious harm. However, while some types of prostate cancer grow slowly and may need minimal or even no treatment, other types are aggressive and can spread quickly.

Prostate cancer that's detected early — when it's still confined to the prostate gland — has the best chance for successful treatment.

Products & Services

- A Book: Man Overboard!

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Healthy Aging

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Prostate Health

- Assortment of Pill Aids from Mayo Clinic Store

Prostate cancer may cause no signs or symptoms in its early stages.

Prostate cancer that's more advanced may cause signs and symptoms such as:

- Trouble urinating

- Decreased force in the stream of urine

- Blood in the urine

- Blood in the semen

- Losing weight without trying

- Erectile dysfunction

When to see a doctor

Make an appointment with your doctor if you have any persistent signs or symptoms that worry you.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

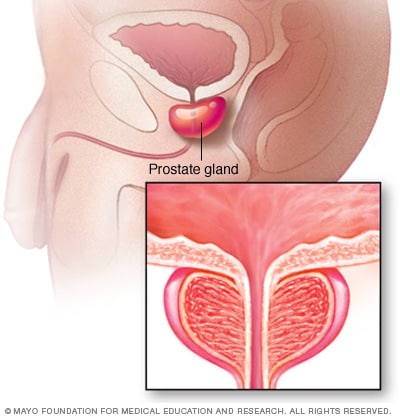

- Prostate gland

The prostate gland is located just below the bladder in men and surrounds the top portion of the tube that drains urine from the bladder (urethra). The prostate's primary function is to produce the fluid that nourishes and transports sperm (seminal fluid).

It's not clear what causes prostate cancer.

Doctors know that prostate cancer begins when cells in the prostate develop changes in their DNA. A cell's DNA contains the instructions that tell a cell what to do. The changes tell the cells to grow and divide more rapidly than normal cells do. The abnormal cells continue living, when other cells would die.

The accumulating abnormal cells form a tumor that can grow to invade nearby tissue. In time, some abnormal cells can break away and spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body.

Risk factors

Factors that can increase your risk of prostate cancer include:

- Older age. Your risk of prostate cancer increases as you age. It's most common after age 50.

- Race. For reasons not yet determined, Black people have a greater risk of prostate cancer than do people of other races. In Black people, prostate cancer is also more likely to be aggressive or advanced.

- Family history. If a blood relative, such as a parent, sibling or child, has been diagnosed with prostate cancer, your risk may be increased. Also, if you have a family history of genes that increase the risk of breast cancer (BRCA1 or BRCA2) or a very strong family history of breast cancer, your risk of prostate cancer may be higher.

- Obesity. People who are obese may have a higher risk of prostate cancer compared with people considered to have a healthy weight, though studies have had mixed results. In obese people, the cancer is more likely to be more aggressive and more likely to return after initial treatment.

Complications

Complications of prostate cancer and its treatments include:

- Cancer that spreads (metastasizes). Prostate cancer can spread to nearby organs, such as your bladder, or travel through your bloodstream or lymphatic system to your bones or other organs. Prostate cancer that spreads to the bones can cause pain and broken bones. Once prostate cancer has spread to other areas of the body, it may still respond to treatment and may be controlled, but it's unlikely to be cured.

- Incontinence. Both prostate cancer and its treatment can cause urinary incontinence. Treatment for incontinence depends on the type you have, how severe it is and the likelihood it will improve over time. Treatment options may include medications, catheters and surgery.

- Erectile dysfunction. Erectile dysfunction can result from prostate cancer or its treatment, including surgery, radiation or hormone treatments. Medications, vacuum devices that assist in achieving erection and surgery are available to treat erectile dysfunction.

More Information

Prostate cancer care at Mayo Clinic

- Prostate cancer metastasis: Where does prostate cancer spread?

You can reduce your risk of prostate cancer if you:

Choose a healthy diet full of fruits and vegetables. Eat a variety of fruits, vegetables and whole grains. Fruits and vegetables contain many vitamins and nutrients that can contribute to your health.

Whether you can prevent prostate cancer through diet has yet to be conclusively proved. But eating a healthy diet with a variety of fruits and vegetables can improve your overall health.

- Choose healthy foods over supplements. No studies have shown that supplements play a role in reducing your risk of prostate cancer. Instead, choose foods that are rich in vitamins and minerals so that you can maintain healthy levels of vitamins in your body.

- Exercise most days of the week. Exercise improves your overall health, helps you maintain your weight and improves your mood. Try to exercise most days of the week. If you're new to exercise, start slow and work your way up to more exercise time each day.

- Maintain a healthy weight. If your current weight is healthy, work to maintain it by choosing a healthy diet and exercising most days of the week. If you need to lose weight, add more exercise and reduce the number of calories you eat each day. Ask your doctor for help creating a plan for healthy weight loss.

Talk to your doctor about increased risk of prostate cancer. If you have a very high risk of prostate cancer, you and your doctor may consider medications or other treatments to reduce the risk. Some studies suggest that taking 5-alpha reductase inhibitors, including finasteride (Propecia, Proscar) and dutasteride (Avodart), may reduce the overall risk of developing prostate cancer. These drugs are used to control prostate gland enlargement and hair loss.

However, some evidence indicates that people taking these medications may have an increased risk of getting a more serious form of prostate cancer (high-grade prostate cancer). If you're concerned about your risk of developing prostate cancer, talk with your doctor.

- Prostate cancer prevention

- Frequent sex: Does it protect against prostate cancer?

- Prostate Cancer Q and A

Living with prostate cancer?

Connect with others like you for support and answers to your questions in the Prostate Cancer support group on Mayo Clinic Connect, a patient community.

Prostate Cancer Discussions

54 Replies Tue, Mar 26, 2024

105 Replies Thu, Mar 28, 2024

18 Replies Sat, Mar 23, 2024

- AskMayoExpert. Prostate cancer (adult). Mayo Clinic; 2018.

- Niederhuber JE, et al., eds. Prostate cancer. In: Abeloff's Clinical Oncology. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2020. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed May 29, 2020.

- Partin AW, et al., eds. In: Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed May 29, 2020.

- AskMayoExpert. Prostate biopsy (adult). Mayo Clinic; 2019.

- Prostate cancer. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx. Accessed May 29, 2020.

- AskMayoExpert. Radical prostatectomy (adult). Mayo Clinic; 2019.

- Rock CL, et al. American Cancer Society guideline for diet and physical activity for cancer prevention. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2020; doi:10.3322/caac.21591.

- Distress management. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx. Accessed May 29, 2020.

- Thompson RH, et al. Radical prostatectomy for octogenarians: How old is too old? Journal of Urology. 2006; doi:10.1016/j.urology.2006.05.031.

- Choline C-11 injection (prescribing information). Mayo Clinic PET Radiochemistry Facility; 2012. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=203155. Accessed June 23, 2020.

- Woodrum DA, et al. Targeted prostate biopsy and MR-guided therapy for prostate cancer. Abdominal Radiology. 2016; doi:10.1007/s00261-016-0681-3.

- Agarwal DK, et al. Initial experience with da Vinci single-port robot-assisted radical prostatectomies. European Urology. 2020; doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2019.04.001.

- Gettman MT, et al. Current status of robotics in urologic laparoscopy. European Urology. 2003; doi:10.1016/S0302-2838(02)00579-1.

- Krambeck AE, et al. Radical prostatectomy for prostatic adenocarcinoma: A matched comparison of open retropubic and robot-assisted techniques. BJU International. 2008; doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08012.x.

- Warner KJ. Allscripts EPSi. Mayo Clinic. Feb. 4, 2020.

- Digital rectal exam

- Prostate Cancer backgrounder

- Prostate cancer stages

- Prostate cancer: Does PSA level affect prognosis?

- Transrectal biopsy of the prostate

Associated Procedures

- Ablation therapy

- Active surveillance for prostate cancer

- Brachytherapy

- Chemotherapy

- Choline C-11 PET scan

- Cryoablation for cancer

- External beam radiation for prostate cancer

- Prostatectomy

- Proton therapy

- Radiation therapy

News from Mayo Clinic

- Prostate cancer: screening and treatment options Jan. 22, 2024, 11:55 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Signs there is a problem with your prostate Nov. 07, 2022, 05:20 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic researchers identify drug resistance factors for advanced prostate cancer Sept. 22, 2022, 02:00 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Importance of exercise for men with prostate cancer Sept. 13, 2022, 04:30 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Prostate biopsy technique reduces infection risk June 13, 2022, 04:20 p.m. CDT

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Let’s celebrate our doctors!

Join us in celebrating and honoring Mayo Clinic physicians on March 30th for National Doctor’s Day.

Skip to Content

- Conquer Cancer

- ASCO Journals

- f Cancer.net on Facebook

- t Cancer.net on Twitter

- q Cancer.net on YouTube

- g Cancer.net on Google

Types of Cancer

- Navigating Cancer Care

- Coping With Cancer

- Research and Advocacy

- Survivorship

Prostate Cancer: Introduction

ON THIS PAGE: You will find some basic information about this disease and the parts of the body it may affect. This is the first page of Cancer.Net’s Guide to Prostate Cancer. Use the menu to see other pages. Think of that menu as a roadmap for this entire guide.

About the prostate

The prostate is a walnut-sized gland located behind the base of the penis, in front of the rectum, and below the bladder. It surrounds the urethra, the tube-like channel that carries urine and semen through the penis. The prostate's main function is to make seminal fluid, the liquid in semen that protects, supports, and helps transport sperm.

The prostate continues to enlarge as people age. This can lead to a condition called benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH), which is when the urethra becomes blocked. BPH is a common condition associated with growing older, and it has not been associated with a greater risk of having prostate cancer.

About prostate cancer

Cancer begins when healthy cells in the prostate change and grow out of control, forming a tumor. A tumor can be cancerous or benign. A cancerous tumor is malignant, meaning it can grow and spread to other parts of the body. A benign tumor means the tumor can grow but will not spread.

Prostate cancer is somewhat unusual when compared with other types of cancer. This is because many prostate tumors do not spread quickly to other parts of the body. Some prostate cancers grow very slowly and may not cause symptoms or problems for years or ever. Even when prostate cancer has spread to other parts of the body, it often can be managed with treatment for a long time. So people with prostate cancer, and even those with advanced prostate cancer, may live with good health and quality of life for many years. However, if the cancer cannot be well controlled with existing treatments, it can cause symptoms like pain and fatigue and can sometimes lead to death. An important part of managing prostate cancer is watching for growth over time to find out if it is growing slowly or quickly. Based on the pattern of growth, your doctor can decide the best available treatment options and when to give them.

Histology is how cancer cells look under a microscope. The most common histology found in prostate cancer is called adenocarcinoma. Other, less common histologic types, called variants, include neuroendocrine prostate cancer and small cell prostate cancer. These variants tend to be more aggressive, produce much less prostate-specific antigen (PSA), and spread outside the prostate earlier. Read more about neuroendocrine tumors .

About prostate-specific antigen (PSA)

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is a protein produced by cells in the prostate gland and released into the bloodstream. PSA levels are measured using a blood test. Although there is no such thing as a “normal PSA” for anyone at any given age, a higher-than-normal level of PSA can be found in people with prostate cancer. Other non-cancerous prostate conditions, such as BPH (see above) or prostatitis can also lead to an elevated PSA level. Prostatitis is the inflammation or infection of the prostate. In addition, some activities like ejaculation can temporarily increase PSA levels. Ejaculations should be avoided before a PSA test to avoid falsely elevated tests. People should discuss with their primary care doctor the pros and cons of PSA testing before using it to screen for prostate cancer. See the Screening section for more information.

Looking for More of an Introduction?

If you would like more of an introduction, explore these related items. Please note that these links will take you to other sections on Cancer.Net:

ASCO Answers Fact Sheet: Read a 1-page fact sheet that offers an introduction to prostate cancer. This free fact sheet is available as a PDF, so it is easy to print.

ASCO Answers Guide: Get this free 52-page booklet that helps you better understand the disease and treatment options. The booklet is available as a PDF, so it is easy to print.

Cancer.Net En Español: Read about prostate cancer in Spanish or read a 1-page ASCO Answers Fact Sheet in Spanish. Infórmase sobre cáncer de próstata en español o una hoja informativa de una página, Respuestas sobre el cáncer .

The next section in this guide is Statistics . It helps explain the number of people who are diagnosed with prostate cancer and general survival rates. Use the menu to choose a different section to read in this guide.

Prostate Cancer Guide

Cancer.Net Guide Prostate Cancer

- Introduction

- Medical Illustrations

- Risk Factors and Prevention

- Symptoms and Signs

- Stages and Grades

- Types of Treatment

- About Clinical Trials

- Latest Research

- Coping with Treatment

- Follow-Up Care

- Questions to Ask the Health Care Team

- Additional Resources

View All Pages

Timely. Trusted. Compassionate.

Comprehensive information for people with cancer, families, and caregivers, from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the voice of the world's oncology professionals.

Find a Cancer Doctor

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Published: 31 July 2018

Landmarks in prostate cancer

- Niranjan J. Sathianathen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3710-014X 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Badrinath R. Konety 1 ,

- Juanita Crook 4 ,

- Fred Saad 5 &

- Nathan Lawrentschuk 2 , 3

Nature Reviews Urology volume 15 , pages 627–642 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

6574 Accesses

66 Citations

47 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cancer screening

- Health care

- Outcomes research

- Prostate cancer

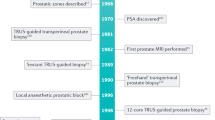

The field of prostate cancer has been the subject of extensive research that has resulted in important discoveries and shaped our appreciation of this disease and its management. Advances in our understanding of the epidemiology, natural history, anatomy, detection, diagnosis, grading, staging, imaging, and management of prostate cancer have changed clinical practice and influenced guideline recommendations. The development of the Gleason score and subsequent modifications enabled accurate prediction of prognosis. Increased anatomical understanding and improved surgical techniques resulted in the development of nerve-sparing surgery for radical prostatectomy. The advent of active surveillance has changed the management of low-risk disease, and chemotherapy and hormonal therapy have improved the outcomes of patients with distant disease. Ongoing research and clinical trials are expected to yield more practice-changing results in the near future.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

195,33 € per year

only 16,28 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Reproduced from ref. 5 , Springer Nature Limited.

Similar content being viewed by others

Landmarks in the evolution of prostate biopsy

Martin J. Connor, Michael A. Gorin, … Hashim U. Ahmed

Impact of preoperative prostate magnetic resonance imaging on the surgical management of high-risk prostate cancer

Janet Baack Kukreja, Tharakeswara K. Bathala, … Brian F. Chapin

A critical evaluation of visual proportion of Gleason 4 and maximum cancer core length quantified by histopathologists

Lina Maria Carmona Echeverria, Aiman Haider, … Hayley C. Whitaker

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J. Clin. 65 , 5–29 (2015).

PubMed Google Scholar

Ferlay, J. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer. 136 , E359–E386 (2015).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Tasian, G. E. et al. PSA screening: determinants of primary-care physician practice patterns. Prostate Cancer Prostat. Dis. 15 , 189–194 (2012).

CAS Google Scholar

Shoag, J. et al. Decline in prostate cancer screening by primary care physicians: an analysis of trends in the use of digital rectal examination and prostate specific antigen testing. J. Urol. 196 , 1047–1052 (2016).

Fleshner, K., Carlsson, S. V. & Roobol, M. J. The effect of the USPSTF PSA screening recommendation on prostate cancer incidence patterns in the USA. Nat. Rev. Urol. 14 , 26 (2016).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Howard, D. H. Declines in prostate cancer incidence after changes in screening recommendations. Arch. Intern. Med. 172 , 1267–1268 (2012).

Potosky, A. L., Miller, B. A., Albertsen, P. C. & Kramer, B. S. The role of increasing detection in the rising incidence of prostate cancer. JAMA 273 , 548–552 (1995).

Gaylis, F. D. et al. Change in prostate cancer presentation coinciding with USPSTF screening recommendations at a community-based urology practice. Urol. Oncol. 35 , 663.e1–663 (2017).

Google Scholar

Cooperberg, M. R. The new US Preventive Services Task Force “C” draft recommendation for prostate cancer screening. Eur. Urol. 72 , 326–328 (2017).

US Preventive Services Task Force. Draft prostate cancer screening recommendation statement (US Preventive Services, 2017).

Patel, A. R. & Klein, E. A. Risk factors for prostate cancer. Nat. Clin. Practice Urol. 6 , 87 (2009).

Odedina, F. T. et al. Prostate cancer disparities in Black men of African descent: a comparative literature review of prostate cancer burden among Black men in the United States, Caribbean, United Kingdom, and West Africa. Infect. Agent Cancer. 4 (Suppl. 1), S2 (2009).

Steinberg, G. D., Carter, B. S., Beaty, T. H., Childs, B. & Walsh, P. C. Family history and the risk of prostate cancer. Prostate 17 , 337–347 (1990).

Bancroft, E. K. et al. Targeted prostate cancer screening in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from the initial screening round of the IMPACT study. Eur. Urol. 66 , 489–499 (2014).

Albertsen, P. C., Hanley, J. A., Gleason, D. F. & Barry, M. J. Competing risk analysis of men aged 55 to 74 years at diagnosis managed conservatively for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA 280 , 975–980 (1998).

Albertsen, P. C., Hanley, J. A. & Fine, J. 20-year outcomes following conservative management of clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA 293 , 2095–2101 (2005).

Johansson, J. E. et al. Natural history of early, localized prostate cancer. JAMA 291 , 2713–2719 (2004).

Pound, C. R. et al. Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. JAMA 281 , 1591–1597 (1999).

Wang, M. C., Valenzuela, L. A., Murphy, G. P. & Chu, T. M. Purification of a human prostate specific antigen. Invest. Urol. 17 , 159–163 (1979).

Stamey, T. A. et al. Prostate-specific antigen as a serum marker for adenocarcinoma of the prostate. N. Engl. J. Med. 317 , 909–916 (1987).

Carter, H. et al. Longitudinal evaluation of prostate-specific antigen levels in men with and without prostate disease. JAMA 267 , 2215–2220 (1992).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Carter, H. B. et al. Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA Guideline. J. Urol. 190 , 419–426 (2013).

Wolf, A. M. et al. American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of prostate cancer: update 2010. CA Cancer J. Clin. 60 , 70–98 (2010).

Cooner, W. H. et al. Prostate cancer detection in a clinical urological practice by ultrasonography, digital rectal examination and prostate specific antigen. J. Urol. 143 , 1146–1152; discussion 52–54 (1990).

Catalona, W. J. et al. Measurement of prostate-specific antigen in serum as a screening test for prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 324 , 1156–1161 (1991).

Catalona, W. J. et al. Comparison of digital rectal examination and serum prostate specific antigen in the early detection of prostate cancer: results of a multicenter clinical trial of 6,630 men. J. Urol. 151 , 1283–1290 (1994).

Thompson, I. M. et al. Prevalence of prostate cancer among men with a prostate-specific antigen level ≤4.0 ng per milliliter. N. Engl. J. Med. 350 , 2239–2246 (2004).

Mottet, N. et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG Guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur. Urol. 71 , 618–629 (2017).

Carroll, P. R. et al. NCCN Guidelines insights: prostate cancer early detection, version 2.2016. J. Natl Compr. Cancer Netw. 14 , 509–519 (2016).

Draisma, G. et al. Lead times and overdetection due to prostate-specific antigen screening: estimates from the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 95 , 868–878 (2003).

Andriole, G. L. et al. Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 360 , 1310–1319 (2009).

Schroder, F. H. et al. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N. Engl. J. Med. 360 , 1320–1328 (2009).

Moyer, V. A. et al. Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 157 , 120–134 (2012).

Jemal, A. et al. Prostate cancer incidence and psa testing patterns in relation to uspstf screening recommendations. JAMA 314 , 2054–2061 (2015).

Bhindi, B. et al. Impact of the US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations against prostate specific antigen screening on prostate biopsy and cancer detection rates. J. Urol. 193 , 1519–1524 (2015).

Weiner, A. B., Matulewicz, R. S., Eggener, S. E. & Schaeffer, E. M. Increasing incidence of metastatic prostate cancer in the United States (2004–2013). Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 19 , 395–397 (2016).

Hu, J. C. et al. Increase in prostate cancer distant metastases at diagnosis in the united states. JAMA Oncol. 3 , 705–707 (2017).

Rezaee, M. E., Ward, C. E., Odom, B. D. & Pollock, M. Prostate cancer screening practices and diagnoses in patients age 50 and older, Southeastern Michigan, pre/post 2012. Prev. Med. 82 , 73–76 (2016).

Bibbins-Domingo, K., Grossman, D. C. & Curry, S. J. The US preventive services task force 2017 draft recommendation statement on screening for prostate cancer: an invitation to review and comment. JAMA 317 , 1949–1950 (2017).

US Preventive Services Task Force et al. Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 319 , 1901–1913 (2018).

Schroder, F. H. et al. Screening for prostate cancer decreases the risk of developing metastatic disease: findings from the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC). Eur. Urol. 62 , 745–752 (2012).

Schroder, F. H. et al. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet 384 , 2027–2035 (2014).

Martin, R. M. et al. Effect of a low-intensity PSA-based screening intervention on prostate cancer mortality: the cap randomized clinical trial. JAMA 319 , 883–895 (2018).

Thompson, I. M. et al. The influence of finasteride on the development of prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 349 , 215–224 (2003).

Thompson, I. M. et al. Long-term survival of participants in the prostate cancer prevention trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 369 , 603–610 (2013).

Unger, J. M. et al. Using medicare claims to examine long-term prostate cancer risk of finasteride in the prostate cancer prevention trial. Natl Cancer Inst. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy035 (2018).

Article Google Scholar

Kramer, B. S. et al. Use of 5-α-reductase inhibitors for prostate cancer chemoprevention: American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Urological Association 2008 Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 27 , 1502–1516 (2009).

Lippman, S. M. et al. Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of prostate cancer and other cancers: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA 301 , 39–51 (2009).

Klein, E. A. et al. Vitamin E and the risk of prostate cancer: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA 306 , 1549–1556 (2011).

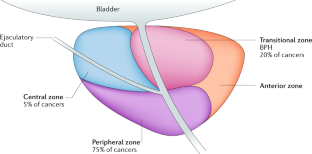

McNeal, J. E. The zonal anatomy of the prostate. Prostate 2 , 35–49 (1981).

Kourambas, J., Angus, D. G., Hosking, P. & Chou, S. T. A histological study of Denonvilliers’ fascia and its relationship to the neurovascular bundle. Br. J. Urol. 82 , 408–410 (1998).

Costello, A. J., Brooks, M. & Cole, O. J. Anatomical studies of the neurovascular bundle and cavernosal nerves. BJU Int. 94 , 1071–1076 (2004).

Walsh, P. C. & Donker, P. J. Impotence following radical prostatectomy: insight into etiology and prevention. J. Urol. 128 , 492–497 (1982).

Walsh, P. C. & Lepor, H. The role of radical prostatectomy in the management of prostatic cancer. Cancer 60 , 526–537 (1987).

Walsh, P. C., Lepor, H. & Eggleston, J. C. Radical prostatectomy with preservation of sexual function: anatomical and pathological considerations. Prostate 4 , 473–485 (1983).

Barringer, B. S. Carcinoma of the prostate. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 34 , 168–176 (1922).

Young, H. H. & Davis, D. M. Young’s Practice of Urology (Philadelphia & London, WB Saunders, 1926).

Hodge, K. K., McNeal, J. E. & Stamey, T. A. Ultrasound guided transrectal core biopsies of the palpably abnormal prostate. J. Urol. 142 , 66–70 (1989).

Levine, M. A., Ittman, M., Melamed, J. & Lepor, H. Two consecutive sets of transrectal ultrasound guided sextant biopsies of the prostate for the detection of prostate cancer. J. Urol. 159 , 471–475; discussion 5–6 (1998).

Presti, J. C. et al. Extended peripheral zone biopsy schemes increase cancer detection rates and minimize variance in prostate specific antigen and age related cancer rates: results of a community multi-practice study. J. Urol. 169 , 125–129 (2003).

Siddiqui, M. M. et al. Comparison of MR/ultrasound fusion-guided biopsy with ultrasound-guided biopsy for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. JAMA 313 , 390–397 (2015).

Chang, D. T. S., Challacombe, B. & Lawrentschuk, N. Transperineal biopsy of the prostate — is this the future? Nat. Rev. Urol. 10 , 690 (2013).

Wright, J. L. & Ellis, W. J. Improved prostate cancer detection with anterior apical prostate biopsies. Urol. Oncol. 24 , 492–495 (2006).

Bott, S. R. et al. Extensive transperineal template biopsies of prostate: modified technique and results. Urology 68 , 1037–1041 (2006).

Hu, Y. et al. A biopsy simulation study to assess the accuracy of several transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS)-biopsy strategies compared with template prostate mapping biopsies in patients who have undergone radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 110 , 812–820 (2012).

Grummet, J. P. et al. Sepsis and ‘superbugs’: should we favour the transperineal over the transrectal approach for prostate biopsy? BJU Int. 114 , 384–388 (2014).

Kasivisvanathan, V. et al. MRI-targeted or standard biopsy for prostate-cancer diagnosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 378 , 1767–1777 (2018).

Gleason, D. F. Classification of prostatic carcinomas. Cancer Chemother. Rep. 50 , 125–128 (1966).

Gleason, D. in Pathology of the Prostate (ed. Bostwick D.G. ) 83–93 (Churchill Livingstone, 1990).

Humphrey, P. A. Gleason grading and prognostic factors in carcinoma of the prostate. Mod. Pathol. 17 , 292–306 (2004).

Delahunt, B., Miller, J., Srigley, J. R., Evans, A. J. & Samaratunga, H. Gleason grading: past, present and future. Histopathology 60 , 75–86 (2012).

Billis, A., et al. The impact of the 2005 international society of urological pathology consensus conference on standard Gleason grading of prostatic carcinoma in needle biopsies. J. Urol. 180 , 548–552; discussion 52–53 (2008).

Epstein, J. I. et al. The 2014 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason grading of prostatic carcinoma: definition of grading patterns and proposal for a new grading system. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 40 , 244–252 (2016).

Wymenga, L. F., Boomsma, J. H., Groenier, K., Piers, D. A. & Mensink, H. J. Routine bone scans in patients with prostate cancer related to serum prostate-specific antigen and alkaline phosphatase. BJU Int. 88 , 226–230 (2001).

Sanda, M. G. et al. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO guideline. Part I: risk stratification, shared decision making, and care options. J. Urol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2017.11.095 (2017).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Taneja, S. S. Imaging in the diagnosis and management of prostate cancer. Rev. Urol. 6 , 101–113 (2004).

Umbehr, M. H., Muntener, M., Hany, T., Sulser, T. & Bachmann, L. M. The role of 11C-choline and 18F-fluorocholine positron emission tomography (PET) and PET/CT in prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. 64 , 106–117 (2013).

Afshar-Oromieh, A. et al. The diagnostic value of PET/CT imaging with the 68Ga-labelled PSMA ligand HBED-CC in the diagnosis of recurrent prostate cancer. Eur. J. Nuclear Med. Mol. Imag. 42 , 197–209 (2015).

Eiber, M. et al. Evaluation of hybrid 68Ga-PSMA-ligand PET/CT in 248 patients with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. J. Nucl. Med. 55 , 668–674 (2015).

Boorjian, S. A., Karnes, R. J., Rangel, L. J., Bergstralh, E. J. & Blute, M. L. Mayo Clinic validation of the D’amico risk group classification for predicting survival following radical prostatectomy. J. Urol. 179 , 1354–1360; discussion 60–61 (2008).

Lee, S. E. et al. Application of the Epstein criteria for prediction of clinically insignificant prostate cancer in Korean men. BJU Int. 105 , 1526–1530 (2010).

D’Amico, A. V. et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA 280 , 969–974 (1998).

Partin, A. W. et al. Combination of prostate-specific antigen, clinical stage, and Gleason score to predict pathological stage of localized prostate cancer. A multi-institutional update. JAMA 277 , 1445–1451 (1997).

Kattan, M. W., Eastham, J. A., Stapleton, A. M., Wheeler, T. M. & Scardino, P. T. A preoperative nomogram for disease recurrence following radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 90 , 766–771 (1998).

Kattan, M. W., Wheeler, T. M. & Scardino, P. T. Postoperative nomogram for disease recurrence after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 17 , 1499–1507 (1999).

Stephenson, A. J. et al. Preoperative nomogram predicting the 10-year probability of prostate cancer recurrence after radical prostatectomy. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 98 , 715–717 (2006).

Cooperberg, M. R. et al. The University of California, San Francisco Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment score: a straightforward and reliable preoperative predictor of disease recurrence after radical prostatectomy. J. Urol. 173 , 1938–1942 (2005).

Cooperberg, M. R., Hilton, J. F. & Carroll, P. R. The CAPRA-S score: a straightforward tool for improved prediction of outcomes after radical prostatectomy. Cancer 117 , 5039–5046 (2011).

Brajtbord, J. S., Leapman, M. S. & Cooperberg, M. R. The CAPRA score at 10 years: contemporary perspectives and analysis of supporting studies. Eur. Urol . 71 , 705–709.

Hricak, H. et al. Prostatic carcinoma: staging by clinical assessment, CT, and MR imaging. Radiology 162 , 331–336 (1987).

Kurhanewicz, J., Swanson, M. G., Nelson, S. J. & Vigneron, D. B. Combined magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopic imaging approach to molecular imaging of prostate cancer. J. Magnet. Resonance Imag. 16 , 451–463 (2002).

Langer, D. L. et al. Prostate cancer detection with multi-parametric MRI: Logistic regression analysis of quantitative T2, diffusion-weighted imaging, and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. J. Magnet. Resonance Imag. 30 , 327–334 (2009).

Tanimoto, A., Nakashima, J., Kohno, H., Shinmoto, H. & Kuribayashi, S. Prostate cancer screening: the clinical value of diffusion-weighted imaging and dynamic MR imaging in combination with T2-weighted imaging. J. Magnet. Resonance Imag. 25 , 146–152 (2007).

Barentsz, J. O. et al. ESUR prostate MR guidelines 2012. Eur. Radiol. 22 , 746–757 (2012).

Vargas, H. A. et al. Updated prostate imaging reporting and data system (PIRADS v2) recommendations for the detection of clinically significant prostate cancer using multiparametric MRI: critical evaluation using whole-mount pathology as standard of reference. Eur. Radiol. 26 , 1606–1612 (2016).

Ahmed, H. U. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of multi-parametric MRI and TRUS biopsy in prostate cancer (PROMIS): a paired validating confirmatory study. Lancet 389 , 815–822 (2017).

Fulgham, P. F. et al. AUA policy statement on the use of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis, staging and management of prostate cancer. J. Urol. 198 , 832–838 (2017).

Newschaffer, C. J., Otani, K., McDonald, M. K. & Penberthy, L. T. Causes of death in elderly prostate cancer patients and in a comparison nonprostate cancer cohort. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 92 , 613–621 (2000).

Montie, J. E. & Smith, J. A. Whitmoreisms: memorable quotes from Willet F. Whitmore Jr, M. D. Urology 63 , 207–209 (2004).

Bill-Axelson, A. et al. Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in localized prostate cancer: the Scandinavian prostate cancer group-4 randomized trial. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 100 , 1144–1154 (2008).

Johansson, E. et al. Long-term quality-of-life outcomes after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting: the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group-4 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 12 , 891–899 (2011).

Hamdy, F. C. et al. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 375 , 1415–1424 (2016).

Wilt, T. J. et al. Radical prostatectomy versus observation for localized prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 367 , 203–213 (2012).

Wilt, T. J. et al. Follow-up of prostatectomy versus observation for early prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 377 , 132–142 (2017).

Choo, R. et al. Feasibility study: watchful waiting for localized low to intermediate grade prostate carcinoma with selective delayed intervention based on prostate specific antigen, histological and/or clinical progression. J. Urol. 167 , 1664–1669 (2002).

Lawrentschuk, N. & Klotz, L. Active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer: an update. Nat. Rev. Urol. 8 , 312–320 (2011).

Parker, C. Active surveillance: towards a new paradigm in the management of early prostate cancer. Lancet Oncol. 5 , 101–106 (2004).

Klotz, L. et al. Long-term follow-up of a large active surveillance cohort of patients with prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 33 , 272–277 (2015).

Tosoian, J. J. et al. Active surveillance of prostate cancer: use, outcomes, imaging, and diagnostic tools. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 35 , e235–e245 (2016).

Adolfsson, J. Watchful waiting and active surveillance: the current position. BJU Int. 102 , 10–14 (2008).

Young, H. H. The early diagnosis and radical cure of carcinoma of the prostate. Being a study of 40 cases and presentation of a radical operation which was carried out in four cases. 1905. J. Urol. 168 , 914–921 (2002).

Millin T. Retropubic urinary surgery. London: Livingstone 35 , 442 (1947).

Millin, T. Retropubic prostatectomy a new extravesical technique: report on 20 cases. Lancet. 246 , 693–696 (1945).

Walsh, P. C. The discovery of the cavernous nerves and development of nerve sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy. J. Urol. 177 , 1632–1635 (2007).

Saranchuk, J. W. et al. Achieving optimal outcomes after radical prostatectomy. J. Clin. Oncol. 23 , 4146–4151 (2005).

Schuessler, W. W., Kavoussi, L. R., Clayman, R. V. & Vancaille, T. Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: initial case report. J. Urol. 147 , 246A (1992).

Guillonneau, B. & Vallancien, G. Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: the Montsouris technique. J. Urol. 163 , 1643–1649 (2000).

Carlucci, J. R., Nabizada-Pace, F. & Samadi, D. B. Robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: technique and outcomes of 700 cases. Int. J. Biomed. Sci. 5 , 201–208 (2009).

Abbou, C. C. et al. Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy with a remote controlled robot. J. Urol. 165 , 1964–1966 (2001).

Menon, M., Hemal, A. K. & VIP Team. Vattikuti Institute prostatectomy: a technique of robotic radical prostatectomy: experience in more than 1000 cases. J. Endourol. 18 , 611–619 (2004).

Yaxley, J. W. et al. Robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy versus open radical retropubic prostatectomy: early outcomes from a randomised controlled phase 3 study. Lancet 388 , 1057–1066 (2016).

Glickman, L., Godoy, G. & Lepor, H. Changes in continence and erectile function between 2 and 4 years after radical prostatectomy. J. Urol. 181 , 731–735 (2009).

Bagshaw, M. A., Kaplan, H. S. & Sagerman, R. H. Linear accelerator supervoltage radiotherapy. VII. Carcinoma of the prostate. Radiology 85 , 121–129 (1965).

Bolla, M. et al. Duration of androgen suppression in the treatment of prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 360 , 2516–2527 (2009).

D’Amico, A. V., Chen, M. H., Renshaw, A. A., Loffredo, M. & Kantoff, P. W. Androgen suppression and radiation versus radiation alone for prostate cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA 299 , 289–295 (2008).

Denham, J. W. et al. Short-term androgen deprivation and radiotherapy for locally advanced prostate cancer: results from the Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group 96.01 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 6 , 841–850 (2005).

Horwitz, E. M. et al. Ten-year follow-up of radiation therapy oncology group protocol 92-02: a phase III trial of the duration of elective androgen deprivation in locally advanced prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 26 , 2497–2504 (2008).

Jones, C. U. et al. Radiotherapy and short-term androgen deprivation for localized prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 365 , 107–118 (2011).

Pilepich, M. V. et al. Androgen suppression adjuvant to definitive radiotherapy in prostate carcinoma — long-term results of phase III RTOG 85–31. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 61 , 1285–1290 (2005).

Roach, M. et al. Short-term neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy and external-beam radiotherapy for locally advanced prostate cancer: long-term results of RTOG 8610. J. Clin. Oncol. 26 , 585–591 (2008).

Bolla, M. et al. Improved survival in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy and goserelin. N. Engl. J. Med. 337 , 295–300 (1997).

Pilepich, M. V. et al. Phase III radiation therapy oncology group (RTOG) trial 86–10 of androgen deprivation adjuvant to definitive radiotherapy in locally advanced carcinoma of the prostate. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 50 , 1243–1252 (2001).

Widmark, A. et al. Endocrine treatment, with or without radiotherapy, in locally advanced prostate cancer (SPCG-7/SFUO-3): an open randomised phase III trial. Lancet 373 , 301–308 (2009).

Warde, P. et al. Combined androgen deprivation therapy and radiation therapy for locally advanced prostate cancer: a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 378 , 2104–2111 (2011).

Zelefsky, M. J., Fuks, Z. & Leibel, S. A. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 12 , 229–237 (2002).

Das, S. et al. Comparison of image-guided radiotherapy technologies for prostate cancer. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 37 , 616–623 (2014).

Wiegel, T. et al. Phase III postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy compared with radical prostatectomy alone in pT3 prostate cancer with postoperative undetectable prostate-specific antigen: ARO 96-02/AUO AP 09/95. J. Clin. Oncol. 27 , 2924–2930 (2009).

Wiegel, T. et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy versus wait-and-see after radical prostatectomy: 10-year follow-up of the ARO 96-02/AUO AP 09/95 trial. Eur. Urol. 66 , 243–250 (2014).

Thompson, I. M. et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy for pathologic T3N0M0 prostate cancer significantly reduces risk of metastases and improves survival: long-term followup of a randomized clinical trial. J. Urol. 181 , 956–962 (2009).

Thompson, I. M. et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy for pathologically advanced prostate cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 296 , 2329–2335 (2006).

Bolla, M. et al. Postoperative radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy: a randomised controlled trial (EORTC trial 22911). Lancet 366 , 572–578 (2005).

Bolla, M. et al. Postoperative radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy for high-risk prostate cancer: long-term results of a randomised controlled trial (EORTC trial 22911). Lancet 380 , 2018–2027 (2012).

Morris, W. J. et al. Low-dose-rate brachytherapy is superior to dose-escalated EBRT for unfavourable risk prostate cancer: the results of the ASCENDE-RT* randomized control trial. Brachytherapy 14 , S12 (2015).

Stock, R. G., Cahlon, O., Cesaretti, J. A., Kollmeier, M. A. & Stone, N. N. Combined modality treatment in the management of high-risk prostate cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 59 , 1352–1359 (2004).

Dearnaley, D. et al. Conventional versus hypofractionated high-dose intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: 5-year outcomes of the randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 CHHiP trial. Lancet Oncol. 17 , 1047–1060 (2016).

Huggins, C., Stevens, R. E. Jr & Hodges, C. V. Studies on prostatic cancer. The effects of castration on advanced carcinoma of the prostate gland. Arch. Surg. 43 , 209–223 (1941).

Huggins, C., Stevens, R. E. Jr & Hodges, C. V. Studies on prostatic cancer. The effect of castration, of oestrogen and of androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate. Arch. Surg. 43 , 209–223 (1941).

Ahmann, F. R. et al. Zoladex: a sustained-release, monthly luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analogue for the treatment of advanced prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 5 , 912–917 (1987).

Goldenberg, S. L. & Bruchovsky, N. Use of cyproterone acetate in prostate cancer. Urol. Clin. North Am. 18 , 111–122 (1991).

Labrie, F. et al. New hormonal therapy in prostatic carcinoma: combined treatment with an LHRH agonist and an antiandrogen. Clin. Invest. Med. 5 , 267–275 (1982).

Crawford, E. D. et al. A controlled trial of leuprolide with and without flutamide in prostatic carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 321 , 419–424 (1989).

Duchesne, G. M. et al. Timing of androgen-deprivation therapy in patients with prostate cancer with a rising PSA (TROG 03.06 and VCOG PR 01–03 [TOAD]): a randomised, multicentre, non-blinded, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 17 , 727–737 (2016).

Messing, E. M. et al. Immediate hormonal therapy compared with observation after radical prostatectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy in men with node-positive prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 341 , 1781–1788 (1999).

Messing, E. M. et al. Immediate versus deferred androgen deprivation treatment in patients with node-positive prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy. Lancet Oncol. 7 , 472–479 (2006).

Crook, J. M. et al. Intermittent androgen suppression for rising PSA level after radiotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 367 , 895–903 (2012).

Hussain, M. et al. Intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation in prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 368 , 1314–1325 (2013).

Walker, L. M., Tran, S. & Robinson, J. W. Luteinizing hormone — releasing hormone agonists: a quick reference for prevalence rates of potential adverse effects. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 11 , 375–384 (2013).

Green, H. J. et al. Quality of life compared during pharmacological treatments and clinical monitoring for non-localized prostate cancer: a randomized controlled trial. BJU Int. 93 , 975–979 (2004).

Rhee, H. et al. Adverse effects of androgen-deprivation therapy in prostate cancer and their management. BJU Int. 115 (Suppl. 5), 3–13 (2015).

Keating, N. L., O’Malley, A. J., Freedland, S. J. & Smith, M. R. Does comorbidity influence the risk of myocardial infarction or diabetes during androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer? Eur. Urol. 64 , 159–166 (2013).

Hamilton, E. J. et al. Structural decay of bone microarchitecture in men with prostate cancer treated with androgen deprivation therapy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95 , E456–463 (2010).

Cornford, P. et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Part II: treatment of relapsing, metastatic, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 71 , 630–642 (2017).

Berthold, D. R., Sternberg, C. N. & Tannock, I. F. Management of advanced prostate cancer after first-line chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 23 , 8247–8252 (2005).

Wozniak, A. J. et al. Cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil in the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer. A Southwest Oncology Group study. Cancer 71 , 3975–3978 (1993).

Sridhar, S. S. et al. Castration-resistant prostate cancer: from new pathophysiology to new treatment. Eur. Urol. 65 , 289–299 (2014).

Petrylak, D. P. et al. Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 351 , 1513–1520 (2004).

Tannock, I. F. et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 351 , 1502–1512 (2004).

Berthold, D. R. et al. Treatment of hormone-refractory prostate cancer with docetaxel or mitoxantrone: relationships between prostate-specific antigen, pain, and quality of life response and survival in the TAX-327 study. Clin. Cancer Res. 14 , 2763–2767 (2008).

de Bono, J. S. et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet 376 , 1147–1154 (2010).

Gravis, G. et al. Androgen-deprivation therapy alone or with docetaxel in non-castrate metastatic prostate cancer (GETUG-AFU 15): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 14 , 149–158 (2013).

Sweeney, C. J. et al. Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 373 , 737–746 (2015).

James, N. D. et al. Addition of docetaxel, zoledronic acid, or both to first-line long-term hormone therapy in prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): survival results from an adaptive, multiarm, multistage, platform randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 387 , 1163–1177 (2016).

James, N. D. et al. Abiraterone for prostate cancer not previously treated with hormone therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 377 , 338–351 (2017).

Fizazi, K. et al. LATITUDE: a phase III, double-blind, randomized trial of androgen deprivation therapy with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone or placebos in newly diagnosed high-risk metastatic hormone-naive prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 35 , LBA3 (2017).

Mohler, J. L. et al. The androgen axis in recurrent prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 10 , 440–448 (2004).

Kumar, A. et al. Substantial interindividual and limited intraindividual genomic diversity among tumors from men with metastatic prostate cancer. Nat. Med. 22 , 369–378 (2016).

Veldscholte, J. et al. A mutation in the ligand binding domain of the androgen receptor of human LNCaP cells affects steroid binding characteristics and response to anti-androgens. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 173 , 534–540 (1990).

Pienta, K. J. & Bradley, D. Mechanisms underlying the development of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 12 , 1665–1671 (2006).

Antonarakis, E. S. et al. AR-V7 and resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone in prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 371 , 1028–1038 (2014).

Guo, Z. et al. A novel androgen receptor splice variant is up-regulated during prostate cancer progression and promotes androgen depletion-resistant growth. Cancer Res. 69 , 2305–2313 (2009).

Beer, T. M. et al. Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 371 , 424–433 (2014).

Shore, N. D. et al. Efficacy and safety of enzalutamide versus bicalutamide for patients with metastatic prostate cancer (TERRAIN): a randomised, double-blind, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 17 , 153–163 (2016).

Scher, H. I. et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 367 , 1187–1197 (2012).

Ryan, C. J. et al. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 368 , 138–148 (2013).

Ryan, C. J. et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone versus placebo plus prednisone in chemotherapy-naive men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (COU-AA-302): final overall survival analysis of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 16 , 152–160 (2015).

Fizazi, K. et al. Abiraterone acetate for treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: final overall survival analysis of the COU-AA-301 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 13 , 983–992 (2012).

Parker, C. et al. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 369 , 213–223 (2013).

Saad, F. et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of zoledronic acid in patients with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate carcinoma. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 94 , 1458–1468 (2002).

Saad, F. et al. Long-term efficacy of zoledronic acid for the prevention of skeletal complications in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 96 , 879–882 (2004).

Fizazi, K. et al. Denosumab versus zoledronic acid for treatment of bone metastases in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: a randomised, double-blind study. Lancet 377 , 813–822 (2011).

Litwin, M. S. et al. The UCLA Prostate Cancer Index: development, reliability, and validity of a health-related quality of life measure. Med. Care. 36 , 1002–1012 (1998).

Wei, J. T., Dunn, R. L., Litwin, M. S., Sandler, H. M. & Sanda, M. G. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology 56 , 899–905 (2000).

Szymanski, K. M., Wei, J. T., Dunn, R. L. & Sanda, M. G. Development and validation of an abbreviated version of the expanded prostate cancer index composite instrument (epic-26) for measuring health-related quality of life among prostate cancer survivors. Urology 76 , 1245–1250 (2010).

Resnick, M. J. et al. Long-term functional outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 368 , 436–445 (2013).

Feldman, H. A., Goldstein, I., Hatzichristou, D. G., Krane, R. J. & McKinlay, J. B. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J. Urol. 151 , 54–61 (1994).

Kim, E. H. & Andriole, G. L. A simplified prostate cancer grading system. Nat. Rev. Urol. 12 , 601–602 (2015).

Epstein, J. I., Walsh, P. C., Carmichael, M. & Brendler, C. B. Pathologic and clinical findings to predict tumor extent of nonpalpable (stage T1c) prostate cancer. JAMA 271 , 368–374 (1994).

de Bono, J. S. et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 364 , 1995–2005 (2011).

Penson, D. F. et al. Enzalutamide versus bicalutamide in castration-resistant prostate cancer: the STRIVE Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 34 , 2098–2106 (2016).

Kantoff, P. W. et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 363 , 411–422 (2010).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Urology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA

Niranjan J. Sathianathen & Badrinath R. Konety

University of Melbourne, Department of Surgery, Urology Unit and Olivia Newton-John Cancer Research Institute Austin Health, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Niranjan J. Sathianathen & Nathan Lawrentschuk

Department of Surgical Oncology, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Department of Radiation Oncology and Developmental Radiotherapeutics, University of British Columbia, Kelowna, British Columbia, Canada

Juanita Crook

Division of Urology, Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montreal, University of Montreal, Montreal, Québec, Canada

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Niranjan J. Sathianathen .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary tables 1 and 2, rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Sathianathen, N.J., Konety, B.R., Crook, J. et al. Landmarks in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol 15 , 627–642 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41585-018-0060-7

Download citation

Published : 31 July 2018

Issue Date : October 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41585-018-0060-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

External validation of predictive models of sexual, urinary, bowel and hormonal function after surgery in prostate cancer subjects.

- Matthew A. Borg

- Michael E. O’Callaghan

- Andrew D. Vincent

BMC Urology (2024)

Diagnosis and management of indeterminate testicular lesions

- Stefanie M. Croghan

- Jamil W. Malak

- Niall F. Davis

Nature Reviews Urology (2024)

N6-methyladenosine regulator YTHDF1 represses the CD8 + T cell-mediated antitumor immunity and ferroptosis in prostate cancer via m6A/PD-L1 manner

- Yibing Wang

Apoptosis (2024)

The role of GCNT1 mediated O-glycosylation in aggressive prostate cancer

- Kirsty Hodgson

- Margarita Orozco-Moreno

- Jennifer Munkley

Scientific Reports (2023)

- Martin J. Connor

- Michael A. Gorin

- Hashim U. Ahmed

Nature Reviews Urology (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: Cancer newsletter — what matters in cancer research, free to your inbox weekly.

Prostate Cancer Research Results and Study Updates

See Advances in Prostate Cancer Research for an overview of recent findings and progress, plus ongoing projects supported by NCI.

Under a new FDA approval, enzalutamide (Xtandi) can now be used alone, or in combination with leuprolide, to treat people with nonmetastatic prostate cancer that is at high risk of returning after surgery or radiation.

FDA approved enzalutamide (Xtandi) combined with talazoparib (Talzenna) for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with alterations in any of 12 DNA repair genes. The drug combination, which blocks both DNA repair activities and hormones that fuel cancer growth, was more effective than the standard treatment in a large clinical trial.

The Decipher genomic test found high-risk prostate cancer even when conventional tests said the tumors were lower risk. This discrepancy appeared to happen more frequently for African-American men.

Men diagnosed with low-risk prostate cancer are increasingly opting against immediate treatment and choosing active surveillance instead, a new study finds. In fact, rates of active surveillance more than doubled between 2014 and 2021.

Adding darolutamide (Nubeqa) to ADT and docetaxel (Taxotere) can improve how long men with hormone-sensitive metastatic prostate cancer live without causing more side effects, results from the ARASENS trial show.

Many with prostate cancer can safely receive shorter, higher-dose radiation therapy after surgery, a new study has found. The approach, called HYPORT, didn’t harm patients’ quality of life compared with the standard radiation approach, trial finds.

A drug called Lu177-PSMA-617 may be a new option for treating advanced prostate cancer. In a large clinical trial, adding the drug—a type of radiopharmaceutical—to standard treatments improved how long participants lived.

For some men with prostate cancer, a genetic biomarker test called Decipher may help predict if their cancer will spread elsewhere in the body. The test could help determine whether hormone therapy, which can cause distressing side effects, is needed.

FDA’s recent approval of relugolix (Orgovyx) is expected to affect the treatment of men with advanced prostate cancer. A large clinical trial showed that relugolix was more effective at reducing testosterone levels than another common treatment.

FDA has approved olaparib (Lynparza) and rucaparib (Rubraca) to treat some men with metastatic prostate cancer. The PARP inhibitors are approved for men whose cancers have stopped responding to hormone treatment and have specific genetic alterations.

For some men with prostate cancer at high risk of spreading, a large clinical trial shows an imaging method called PSMA PET-CT is more likely to detect metastatic tumors than the standard imaging approach used in many countries.

Testing for prostate cancer with a combined biopsy method led to more accurate diagnosis and prediction of the course of the disease in an NCI study. The method is poised to reduce the risk of prostate cancer overtreatment and undertreatment.

In the Veterans Affairs health care system—where all patients have equal access to care—African American men did not appear to have more-aggressive prostate cancer when diagnosed or a higher death rate from the disease than non-Hispanic white men.

In two large clinical trials, the drugs enzalutamide (Xtandi) and apalutamide (Erleada), respectively, combined with the androgen deprivation therapy, improved the survival of men with metastatic prostate cancer that still responds to hormone-suppressing therapies.

The Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial showed that finasteride can reduce the risk of prostate cancer, but might increase the risk of aggressive disease. NCI’s Howard Parnes talks about subsequent findings and what they mean for men aged 55 and older.

The investigational drug darolutamide can help delay the spread of prostate cancer in some men with the disease, a recent clinical trial shows. In addition, the drug caused fewer side effects than similar prostate cancer drugs.

For African American men, the risk of dying from low-grade prostate cancer is double that of men of other races, a new study has found. But, despite the increase, the risk is still small.

Researchers have found that men with advanced prostate cancer may be more likely than previously thought to develop a more aggressive form of the disease. The subtype, called t-SCNC, was linked with shorter survival than other subtypes.

RESPOND is the largest coordinated study on biological and non-biological factors associated with aggressive prostate cancer in African-American men. The study is an effort to learn why these men disproportionally experience aggressive disease.

In a small clinical trial, researchers compared the efficacy of a much lower dose of the cancer drug abiraterone (Zytiga) taken with a low-fat breakfast with a full dose taken on an empty stomach, as directed on the drug’s label.

In the trial that led to the approval, apalutamide (Erleada) delayed cancer metastasis for men with prostate cancer that is resistant to androgen deprivation therapy.

A new study in mice has revealed a molecular link between a high-fat diet and the growth and spread of prostate cancer. The findings, the study leaders believe, raise the possibility that changes in diet could potentially improve treatment outcomes in some men.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the approval of abiraterone (Zytiga®) for men with prostate cancer. The agency approved abiraterone, in combination with the steroid prednisone, for men with metastatic prostate cancer that is responsive to hormone-blocking treatments (also known as castration-sensitive) and is at high risk of progressing.

Researchers have identified an emerging subtype of metastatic prostate cancer that is resistant to therapies that block hormones that fuel the disease.

In two large clinical trials, adding the hormone-blocking drug abiraterone to androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) allowed men with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer to live longer than men who were treated with ADT alone.

Findings from a new study show testing for two biomarkers in urine may help some men avoid an unnecessary biopsy to detect a suspected prostate cancer.

Long-term results from an NCI-sponsored clinical trial suggest that adding androgen deprivation therapy to radiation therapy can improve survival for some men with recurrent prostate cancer.

Researchers estimate that nearly 12% of men with advanced prostate cancer have inherited mutations in genes that play a role in repairing damaged DNA.

Researchers have identified a potential alternative approach to blocking a key molecular driver of an advanced form of prostate cancer, called androgen-independent or castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Essay: Raising awareness about prostate cancer

Other than skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men and is the second most common cause of cancer death in the United States.

The American Cancer Society estimates that in 2021 more than 248,000 American men will be diagnosed and more than 34,000 men will die of prostate cancer. Nearly 1 in 8 men will be afflicted by this disease in their lifetime and 1 in 41 men will die of prostate cancer.

Most commonly, prostate cancer manifests as a localized, silent disease, progressing slowly with minimal to no symptoms. Once the disease has spread out of the prostate to adjacent organs, lymph nodes or bones, symptoms become more prevalent. These include pain, urinary problems, neurologic symptoms, and more.

Data have shown that active screening can lead to early diagnosis. Studies with long-term follow-up have demonstrated an approximate 30 percent decrease in prostate cancer mortality when screening is implemented. In fact, the implementation of prostate cancer screening has been one of the main reasons for the decrease in prostate cancer-specific death by more than 50 percent from 1993 to 2017.

Screening for prostate cancer is simple and quick, performed with a digital rectal exam (DRE) assessing prostate size and contour and a blood test for prostate-specific antigen (PSA). PSA is a protein made by cells located in the prostate gland (both normal cells and cancer cells). The risk of being diagnosed with prostate cancer increases as the PSA blood level increases.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that men over the age of 45 should discuss prostate cancer screening with their physicians. For men at increased risk (known family history, known genetic risk factors, or African ancestry) discussion about screening should start even earlier at age 40.

When prostate cancer is diagnosed at an early stage, and is still localized, the cure rate is incredibly high, with a nearly 100 percent five-year cancer-free survival rate. Once prostate cancer is diagnosed, various treatment options are available, ranging from “active surveillance” (frequent monitoring of the disease with no active treatment) to radiation or surgery and other therapeutic options.

Novel scientific discoveries, new treatment options and robust research published in the last decade have led to significant advances in the diagnosis and treatment of this common malignancy.

Despite the continuous increase in the incidence and prevalence of prostate cancer and a constant rising rate of cancer-specific death, not all men actively seek preventive care and undergo screening.

September is Prostate Cancer Awareness Month. During this time, various attempts are made across the country to raise awareness of this highly prevalent cancer and promote screening and early detection.

At Upstate Urology at the Mohawk Valley Health System (MVHS), we are organizing a free screening event at various dates and times throughout the month of September. These events are being scheduled so as to adhere to social distancing guidelines, with individual appointments being made.

It’s important that you don’t put off screenings during this time of COVID, and we encourage all men between the ages of 45-75 to use this opportunity to be screened for prostate cancer.

Visit mvhealthsystem.org/urology for more information.

As a urologist treating prostate cancer patients and as a son of a prostate cancer survivor, I hope our call is answered, and with your help, we will succeed in raising awareness and spreading the word.

Please join our important quest to fight this cancer by reaching out to more men and improving early detection rates.

Dr. Hanan Goldberg, MD, MSc, is assistant professor at SUNY Upstate Medical University and chief of Upstate Urology at the Mohawk Valley Health System (MVHS).

bestessayhelp.com

Prostate Cancer – Essay Sample