Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Americans’ complicated feelings about social media in an era of privacy concerns

Amid public concerns over Cambridge Analytica’s use of Facebook data and a subsequent movement to encourage users to abandon Facebook , there is a renewed focus on how social media companies collect personal information and make it available to marketers.

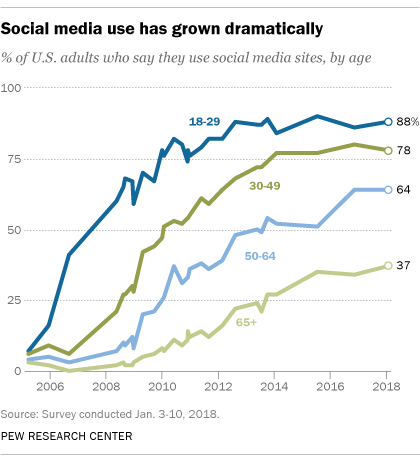

Pew Research Center has studied the spread and impact of social media since 2005, when just 5% of American adults used the platforms. The trends tracked by our data tell a complex story that is full of conflicting pressures. On one hand, the rapid growth of the platforms is testimony to their appeal to online Americans. On the other, this widespread use has been accompanied by rising user concerns about privacy and social media firms’ capacity to protect their data.

All this adds up to a mixed picture about how Americans feel about social media. Here are some of the dynamics.

People like and use social media for several reasons

About seven-in-ten American adults (69%) now report they use some kind of social media platform (not including YouTube) – a nearly fourteenfold increase since Pew Research Center first started asking about the phenomenon. The growth has come across all demographic groups and includes 37% of those ages 65 and older.

The Center’s polls have found over the years that people use social media for important social interactions like staying in touch with friends and family and reconnecting with old acquaintances. Teenagers are especially likely to report that social media are important to their friendships and, at times, their romantic relationships .

Beyond that, we have documented how social media play a role in the way people participate in civic and political activities, launch and sustain protests , get and share health information , gather scientific information , engage in family matters , perform job-related activities and get news . Indeed, social media is now just as common a pathway to news for people as going directly to a news organization website or app.

Our research has not established a causal relationship between people’s use of social media and their well-being. But in a 2011 report, we noted modest associations between people’s social media use and higher levels of trust, larger numbers of close friends, greater amounts of social support and higher levels of civic participation.

People worry about privacy and the use of their personal information

While there is evidence that social media works in some important ways for people, Pew Research Center studies have shown that people are anxious about all the personal information that is collected and shared and the security of their data.

Overall, a 2014 survey found that 91% of Americans “agree” or “strongly agree” that people have lost control over how personal information is collected and used by all kinds of entities. Some 80% of social media users said they were concerned about advertisers and businesses accessing the data they share on social media platforms, and 64% said the government should do more to regulate advertisers.

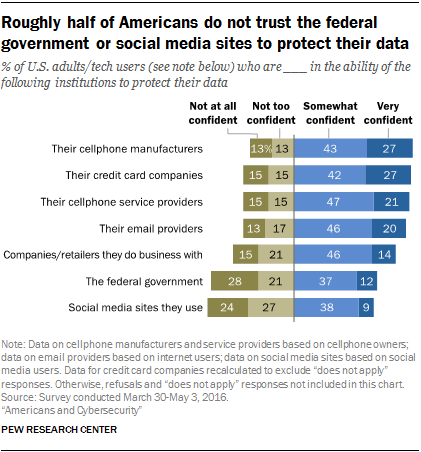

Another survey last year found that just 9% of social media users were “very confident” that social media companies would protect their data . About half of users were not at all or not too confident their data were in safe hands.

Moreover, people struggle to understand the nature and scope of the data collected about them. Just 9% believe they have “a lot of control” over the information that is collected about them, even as the vast majority (74%) say it is very important to them to be in control of who can get information about them.

Six-in-ten Americans (61%) have said they would like to do more to protect their privacy. Additionally, two-thirds have said current laws are not good enough in protecting people’s privacy, and 64% support more regulation of advertisers.

Some privacy advocates hope that the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation , which goes into effect on May 25, will give users – even Americans – greater protections about what data tech firms can collect, how the data can be used, and how consumers can be given more opportunities to see what is happening with their information.

People’s issues with the social media experience go beyond privacy

In addition to the concerns about privacy and social media platforms uncovered in our surveys, related research shows that just 5% of social media users trust the information that comes to them via the platforms “a lot.”

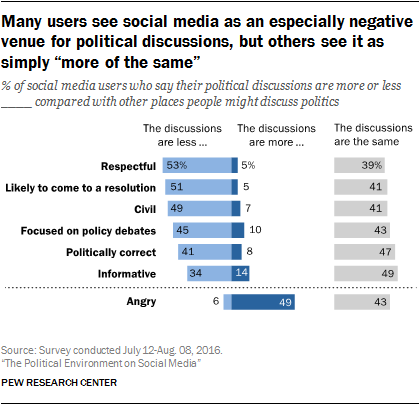

Moreover, social media users can be turned off by what happens on social media. For instance, social media sites are frequently cited as places where people are harassed . Near the end of the 2016 election campaign, 37% of social media users said they were worn out by the political content they encountered, and large shares said social media interactions with those opposed to their views were stressful and frustrating. Large shares also said that social media interactions related to politics were less respectful, less conclusive, less civil and less informative than offline interactions.

A considerable number of social media users said they simply ignored political arguments when they broke out in their feeds. Others went steps further by blocking or unfriending those who offended or bugged them.

Why do people leave or stay on social media platforms?

The paradox is that people use social media platforms even as they express great concern about the privacy implications of doing so – and the social woes they encounter. The Center’s most recent survey about social media found that 59% of users said it would not be difficult to give up these sites, yet the share saying these sites would be hard to give up grew 12 percentage points from early 2014.

Some of the answers about why people stay on social media could tie to our findings about how people adjust their behavior on the sites and online, depending on personal and political circumstances. For instance, in a 2012 report we found that 61% of Facebook users said they had taken a break from using the platform. Among the reasons people cited were that they were too busy to use the platform, they lost interest, they thought it was a waste of time and that it was filled with too much drama, gossip or conflict.

In other words, participation on the sites for many people is not an all-or-nothing proposition.

People pursue strategies to try to avoid problems on social media and the internet overall. Fully 86% of internet users said in 2012 they had taken steps to try to be anonymous online. “Hiding from advertisers” was relatively high on the list of those they wanted to avoid.

Many social media users fine-tune their behavior to try to make things less challenging or unsettling on the sites, including changing their privacy settings and restricting access to their profiles. Still, 48% of social media users reported in a 2012 survey they have difficulty managing their privacy controls.

After National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden disclosed details about government surveillance programs starting in 2013, 30% of adults said they took steps to hide or shield their information and 22% reported they had changed their online behavior in order to minimize detection.

One other argument that some experts make in Pew Research Center canvassings about the future is that people often find it hard to disconnect because so much of modern life takes place on social media. These experts believe that unplugging is hard because social media and other technology affordances make life convenient and because the platforms offer a very efficient, compelling way for users to stay connected to the people and organizations that matter to them.

Note: See topline results for overall social media user data here (PDF).

- Emerging Technology

- Online Privacy & Security

- Privacy Rights

- Social Media

- Technology Policy Issues

Lee Rainie is director of internet and technology research at Pew Research Center .

Many Americans think generative AI programs should credit the sources they rely on

Americans’ use of chatgpt is ticking up, but few trust its election information, q&a: how we used large language models to identify guests on popular podcasts, computer chips in human brains: how americans view the technology amid recent advances, striking findings from 2023, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

Privacy Issues in Social Media

This essay about privacy issues in social media discusses the complexities and risks associated with the vast amounts of personal data shared on platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. It highlights the lack of transparency in how companies use this data, often hidden behind dense privacy policies, and the risks of data being shared with third parties for purposes that range from benign to malicious. The essay also touches on the psychological impact of constant surveillance, particularly on younger users, and the broader societal implications, including political manipulation exemplified by the Cambridge Analytica scandal. It concludes with a call for robust regulatory measures, like the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, and emphasizes the need for a systemic approach to protect privacy, involving not just users but also companies and governments in a collective effort to manage and safeguard personal information on social media.

How it works

When discussing privacy issues in social media, the landscape is complex and fraught with ethical dilemmas and potential risks. As the use of social platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram has become nearly ubiquitous, the line between private life and public exposure has significantly blurred. This merging raises profound questions about personal data’s collection, use, and security by these influential digital platforms.

At the heart of the privacy conundrum on social media is the sheer volume of personal information users willingly share online.

From birthdays and anniversaries to work history and family photos, the amount of intimate data circulating on these platforms is staggering. While it’s true that sharing this information can help maintain connections and even foster new ones, it also sets the stage for more insidious uses of our data.

One major issue is transparency—or the lack thereof. Social media companies have mastered the art of hiding their data practices behind dense privacy policies that are seldom read and even less frequently understood. This lack of clarity is not accidental; it serves to obscure the extent to which data is not just collected but also analyzed and monetized. Most users are unaware of how deep the data-mining goes and how their information contributes to vast economic networks that transcend simple social interactions.

The complications continue when considering how social media data is shared with third parties. The intentions of these third parties can vary widely, ranging from market research firms analyzing trends to advertisers targeting users with unnerving precision. The potential for misuse becomes clear when you consider incidents like the Cambridge Analytica scandal, where millions of Facebook users’ data was used without their explicit consent to influence political campaigns. Such breaches illustrate not only the potential for misuse but also the global impact that mishandled social media data can have.

Beyond the implications for individual privacy and global politics, there’s also a personal cost to this constant surveillance. The psychological impact of knowing one’s actions, interactions, and even inactions are constantly monitored can lead to a phenomenon known as ‘social cooling’—a form of social behavior and expression alteration due to the awareness of being watched. This effect is particularly concerning for younger generations, who are not only more active on these platforms but are also in critical stages of developing their identities.

Recognizing these issues, there has been a push for more robust regulatory measures. The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is one of the more prominent efforts to safeguard personal data and restore some control to users. The GDPR not only mandates that companies protect the personal information they gather but also empowers users with rights to access, correct, and delete their data. While this regulation is a step in the right direction, the global nature of the internet complicates enforcement, and many users around the world remain unprotected by such policies.

In the U.S., the response has been more fragmented, with calls for American equivalents to the GDPR growing louder in the wake of repeated data privacy scandals. These calls reflect a growing awareness that privacy cannot solely be managed by individual users adjusting their settings—a systemic approach is needed. However, creating and enforcing such regulations in a way that balances the benefits of social media with privacy rights remains a significant challenge.

The conclusion seems clear: as valuable as social media can be in connecting us, its role in our lives must be carefully managed to protect our privacy. This management is not just the responsibility of users but also of companies and governments. Users must educate themselves about their data rights and practice digital hygiene, companies should commit to ethical data practices and transparency, and governments need to enact and enforce regulations that hold these companies accountable.

Ultimately, addressing privacy issues in social media requires a collective effort and an ongoing dialogue among all stakeholders involved. Only through sustained engagement can we hope to harness the benefits of social media while safeguarding against its potential harms. As we move forward, it’s imperative to keep these conversations alive and active, ensuring that our digital environments reflect the values we hold dear in our offline lives.

Cite this page

Privacy Issues in Social Media. (2024, May 01). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/privacy-issues-in-social-media/

"Privacy Issues in Social Media." PapersOwl.com , 1 May 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/privacy-issues-in-social-media/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Privacy Issues in Social Media . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/privacy-issues-in-social-media/ [Accessed: 12 May. 2024]

"Privacy Issues in Social Media." PapersOwl.com, May 01, 2024. Accessed May 12, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/privacy-issues-in-social-media/

"Privacy Issues in Social Media," PapersOwl.com , 01-May-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/privacy-issues-in-social-media/. [Accessed: 12-May-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Privacy Issues in Social Media . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/privacy-issues-in-social-media/ [Accessed: 12-May-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Social Media: The Privacy Issues

Sharing private information through social media is commonplace in today’s society and lifestyle. Individuals use numerous social networking sites such as Facebook and Instagram. These users share their private information, particularly upon registration to become a member of the sites. They also reveal their private information by making regular updates and posts that they put online. As a result, an individual can easily be traced and manipulated through the information offered on these websites making internet privacy a major concern. This sheds light on the importance of learning technological abilities to enable social media users deal with the issue of privacy on these websites. This argumentative essay will discuss the privacy issues that users may encounter on social media and argue that it is important to have a balance between privacy and online confidentiality to operate effectively in both the offline and online worlds.

One of the disadvantages of social media is its exposure of people’s private lives to the online world and worldwide audience. Users of social media sites, such as Facebook, have become more and more open as they willingly reveal too much of their personal information on these websites. Today, the issue of sharing too much personal information has become the societal standard, forgetting that this information can be utilized in a variety of ways, including negative methods such as stalking or identity theft (Kelly and Guskin). Users of social media sites must examine what information they are uploading or sharing online and with whom they are sharing it (Kelly and Guskin). Through this, a balance between privacy and internet disclosure of information must be achieved and maintained, as failure to do so may negatively affect online users.

A thorough awareness of privacy concerns and social media is essential to comprehend this issue. Recently, many people have used and been drawn to social media sites as they allow users to communicate and relate in different ways. These websites enable individuals to create a network that characterizes their social contacts, share online content easily, provide platforms for online communication, and share their daily activities and experiences with their mates and the virtual communities (Ayaburi and Daniel 171). However, social media has led to several potential hazards to users’ privacy. This is evident when data about a user is being uploaded and further distributed in many circumstances without authorization, request, or approval (Ayaburi and Daniel 171). As a result, social media tests and distorts private information.

Furthermore, social media users have grown accustomed to sharing personal information, and as a result, they are unaware of the hazards and risks that they subject themselves to and confront online due to privacy concerns. It is enjoyable and great to share their daily activities and lifestyles with family and friends online, but as Kelly and Guskin point out, digital material is constantly permanent and may be duplicated, reused, and spread. Users will supply information about their location, region, mobile number, and birthdate, among other things, when building a social media profile. Such data is freely accessible by hackers and the general public, and it is one of the ways through which identity theft occurs (Ayaburi and Daniel 172). Since the information is shared and saved on social media networking sites, one’s identity can be stolen or viewed by anyone.

Stalking is another issue that arises due to privacy concerns. Users can choose to make their profiles private, but their group memberships and friendships links are usually available to their shared public (Ayaburi and Daniel 172). This is one of the ways that data leakage occurs; individuals who are not friends may see those postings in which they are tagged, and they can access and read users’ personal information even if their profile is configured to be private. Additionally, such data links may allow malicious actors to be aware of and track one’s internet activity. Such dangers might also arise when a person befriends other individuals online without taking the time to learn about their identities (Kelly and Guskin). Individuals sharing their everyday activities online is now the standard and trend (Ayaburi and Daniel 176). Users often post and share images while at the mall, and this is one of the ways that stalkers may track users’ every step, as well as their activities and routines on a daily basis.

Despite the need for discretion when it relates to exposing personal data, there are a lot of advantages to participating in online discussions. In real life, the establishment of social ties allows for selective disclosure of personal data, a sense of being closer to another person, and knowledge of each other (Ayaburi and Daniel 179). Individuals can now form and build social relationships with one another by doing so through social networking sites. This allows them to get to know other users better and create online friendships (Ayaburi and Daniel 179). Therefore, social media has provided people with a channel and network with which they can socialize and build social ties with others regardless of time or location.

In addition to this, social media has had a tremendous impact on today’s world, and it has transformed the way people think about the amount of data that should and should not be displayed or shared publicly (Kelly and Guskin). When computers and the internet first became common in the early 2000s, it was inconceivable for people to share their location, images, or their names online without considering their privacy and security. Users have allowed and encouraged this technology to transform and increase their zones of tolerance because of the flexibility it offers them to trade information online, making it pleasant and easy to do so over time, thanks to the development of social media in the mid-2000s (Kelly, and Guskin). Ayaburi and Daniel go so far as to say that privacy is no longer considered the social norm (181). Despite the benefits of online disclosure, such as the union of individuals and the formation of social relationships, users must remember and realize that they must use the majority of social media while preserving and prioritizing their privacy.

The relationship between social media and privacy has been highlighted and considered critical and necessary in sharing information on social media. The consequences and hazards of ignoring privacy concerns have been weighed against the social advantages of the disclosure. As a result, logical answers for social networking users include understanding how these media sites operate and function and making the most use of the media sites’ privacy policies and capabilities to create a safer online world for sharing personal data and talking to others. The ability of social media to improve social interactions must be welcomed and appreciated, but a balance between websites disclosure of information and privacy must be maintained on a regular basis.

Works Cited

Ayaburi, Emmanuel W., and Daniel N. Treku. “Effect of Penitence on Social Media Trust and Privacy Concerns: The Case of Facebook.” International Journal of Information Management, vol. 50, 2020, pp. 171-181, Web.

Kelly, Heather, and Emily Guskin. “Americans Widely Distrust Facebook, TikTok and Instagram with Their Data, Poll Finds.” The Washington Post, WP Company, Web.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2023, March 2). Social Media: The Privacy Issues. https://studycorgi.com/social-media-the-privacy-issues/

"Social Media: The Privacy Issues." StudyCorgi , 2 Mar. 2023, studycorgi.com/social-media-the-privacy-issues/.

StudyCorgi . (2023) 'Social Media: The Privacy Issues'. 2 March.

1. StudyCorgi . "Social Media: The Privacy Issues." March 2, 2023. https://studycorgi.com/social-media-the-privacy-issues/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Social Media: The Privacy Issues." March 2, 2023. https://studycorgi.com/social-media-the-privacy-issues/.

StudyCorgi . 2023. "Social Media: The Privacy Issues." March 2, 2023. https://studycorgi.com/social-media-the-privacy-issues/.

This paper, “Social Media: The Privacy Issues”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: November 13, 2023 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

The Battle for Digital Privacy Is Reshaping the Internet

As Apple and Google enact privacy changes, businesses are grappling with the fallout, Madison Avenue is fighting back and Facebook has cried foul.

By Brian X. Chen

Listen to This Article

SAN FRANCISCO — Apple introduced a pop-up window for iPhones in April that asks people for their permission to be tracked by different apps.

Google recently outlined plans to disable a tracking technology in its Chrome web browser.

And Facebook said last month that hundreds of its engineers were working on a new method of showing ads without relying on people’s personal data.

The developments may seem like technical tinkering, but they were connected to something bigger: an intensifying battle over the future of the internet. The struggle has entangled tech titans, upended Madison Avenue and disrupted small businesses. And it heralds a profound shift in how people’s personal information may be used online, with sweeping implications for the ways that businesses make money digitally.

At the center of the tussle is what has been the internet’s lifeblood: advertising .

More than 20 years ago, the internet drove an upheaval in the advertising industry. It eviscerated newspapers and magazines that had relied on selling classified and print ads, and threatened to dethrone television advertising as the prime way for marketers to reach large audiences.

Instead, brands splashed their ads across websites, with their promotions often tailored to people’s specific interests. Those digital ads powered the growth of Facebook, Google and Twitter, which offered their search and social networking services to people without charge. But in exchange, people were tracked from site to site by technologies such as “ cookies, ” and their personal data was used to target them with relevant marketing.

Now that system, which ballooned into a $350 billion digital ad industry, is being dismantled. Driven by online privacy fears, Apple and Google have started revamping the rules around online data collection. Apple, citing the mantra of privacy, has rolled out tools that block marketers from tracking people. Google, which depends on digital ads, is trying to have it both ways by reinventing the system so it can continue aiming ads at people without exploiting access to their personal data.

If personal information is no longer the currency that people give for online content and services, something else must take its place. Media publishers, app makers and e-commerce shops are now exploring different paths to surviving a privacy-conscious internet, in some cases overturning their business models. Many are choosing to make people pay for what they get online by levying subscription fees and other charges instead of using their personal data.

Jeff Green, the chief executive of the Trade Desk, an ad-technology company in Ventura, Calif., that works with major ad agencies, said the behind-the-scenes fight was fundamental to the nature of the web.

“The internet is answering a question that it’s been wrestling with for decades, which is: How is the internet going to pay for itself?” he said.

The fallout may hurt brands that relied on targeted ads to get people to buy their goods. It may also initially hurt tech giants like Facebook — but not for long. Instead, businesses that can no longer track people but still need to advertise are likely to spend more with the largest tech platforms, which still have the most data on consumers.

David Cohen, chief executive of the Interactive Advertising Bureau, a trade group, said the changes would continue to “drive money and attention to Google, Facebook, Twitter.”

The shifts are complicated by Google’s and Apple’s opposing views on how much ad tracking should be dialed back. Apple wants its customers, who pay a premium for its iPhones, to have the right to block tracking entirely. But Google executives have suggested that Apple has turned privacy into a privilege for those who can afford its products.

For many people, that means the internet may start looking different depending on the products they use. On Apple gadgets, ads may be only somewhat relevant to a person’s interests, compared with highly targeted promotions inside Google’s web. Website creators may eventually choose sides, so some sites that work well in Google’s browser might not even load in Apple’s browser, said Brendan Eich, a founder of Brave, the private web browser.

“It will be a tale of two internets,” he said.

Businesses that do not keep up with the changes risk getting run over. Increasingly, media publishers and even apps that show the weather are charging subscription fees, in the same way that Netflix levies a monthly fee for video streaming. Some e-commerce sites are considering raising product prices to keep their revenues up.

Consider Seven Sisters Scones, a mail-order pastry shop in Johns Creek, Ga., which relies on Facebook ads to promote its items. Nate Martin, who leads the bakery’s digital marketing, said that after Apple blocked some ad tracking, its digital marketing campaigns on Facebook became less effective. Because Facebook could no longer get as much data on which customers like baked goods, it was harder for the store to find interested buyers online.

“Everything came to a screeching halt,” Mr. Martin said. In June, the bakery’s revenue dropped to $16,000 from $40,000 in May.

Sales have since remained flat, he said. To offset the declines, Seven Sisters Scones has discussed increasing prices on sampler boxes to $36 from $29.

Apple declined to comment, but its executives have said advertisers will adapt. Google said it was working on an approach that would protect people’s data but also let advertisers continue targeting users with ads.

Since the 1990s, much of the web has been rooted in digital advertising. In that decade, a piece of code planted in web browsers — the “cookie” — began tracking people’s browsing activities from site to site. Marketers used the information to aim ads at individuals, so someone interested in makeup or bicycles saw ads about those topics and products.

After the iPhone and Android app stores were introduced in 2008, advertisers also collected data about what people did inside apps by planting invisible trackers. That information was linked with cookie data and shared with data brokers for even more specific ad targeting.

The result was a vast advertising ecosystem that underpinned free websites and online services. Sites and apps like BuzzFeed and TikTok flourished using this model. Even e-commerce sites rely partly on advertising to expand their businesses.

But distrust of these practices began building. In 2018, Facebook became embroiled in the Cambridge Analytica scandal, where people’s Facebook data was improperly harvested without their consent. That same year, European regulators enacted the General Data Protection Regulation , laws to safeguard people’s information. In 2019, Google and Facebook agreed to pay record fines to the Federal Trade Commission to settle allegations of privacy violations.

In Silicon Valley, Apple reconsidered its advertising approach. In 2017, Craig Federighi, Apple’s head of software engineering, announced that the Safari web browser would block cookies from following people from site to site.

“It kind of feels like you’re being tracked, and that’s because you are,” Mr. Federighi said. “No longer.”

Last year, Apple announced the pop-up window in iPhone apps that asks people if they want to be followed for marketing purposes. If the user says no, the app must stop monitoring and sharing data with third parties.

That prompted an outcry from Facebook , which was one of the apps affected. In December, the social network took out full-page newspaper ads declaring that it was “standing up to Apple” on behalf of small businesses that would get hurt once their ads could no longer find specific audiences.

“The situation is going to be challenging for them to navigate,” Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s chief executive, said.

Facebook is now developing ways to target people with ads using insights gathered on their devices, without allowing personal data to be shared with third parties. If people who click on ads for deodorant also buy sneakers, Facebook can share that pattern with advertisers so they can show sneaker ads to that group. That would be less intrusive than sharing personal information like email addresses with advertisers.

“We support giving people more control over how their data is used, but Apple’s far-reaching changes occurred without input from the industry and those who are most impacted,” a Facebook spokesman said.

Since Apple released the pop-up window, more than 80 percent of iPhone users have opted out of tracking worldwide, according to ad tech firms. Last month, Peter Farago, an executive at Flurry, a mobile analytics firm owned by Verizon Media, published a post on LinkedIn calling the “time of death” for ad tracking on iPhones.

At Google, Sundar Pichai, the chief executive, and his lieutenants began discussing in 2019 how to provide more privacy without killing the company’s $135 billion online ad business. In studies, Google researchers found that the cookie eroded people’s trust. Google said its Chrome and ad teams concluded that the Chrome web browser should stop supporting cookies.

But Google also said it would not disable cookies until it had a different way for marketers to keep serving people targeted ads. In March, the company tried a method that uses its data troves to place people into groups based on their interests, so marketers can aim ads at those cohorts rather than at individuals. The approach is known as Federated Learning of Cohorts, or FLOC.

Plans remain in flux. Google will not block trackers in Chrome until 2023 .

Even so, advertisers said they were alarmed.

In an article this year, Sheri Bachstein, the head of IBM Watson Advertising, warned that the privacy shifts meant that relying solely on advertising for revenue was at risk. Businesses must adapt, she said, including by charging subscription fees and using artificial intelligence to help serve ads.

“The big tech companies have put a clock on us,” she said in an interview.

Kate Conger contributed reporting.

Brian X. Chen is the lead consumer technology writer for The Times. He reviews products and writes Tech Fix , a column about the social implications of the tech we use. Before joining The Times in 2011, he reported on Apple and the wireless industry for Wired. More about Brian X. Chen

Feb 15, 2023

6 Example Essays on Social Media | Advantages, Effects, and Outlines

Got an essay assignment about the effects of social media we got you covered check out our examples and outlines below.

Social media has become one of our society's most prominent ways of communication and information sharing in a very short time. It has changed how we communicate and has given us a platform to express our views and opinions and connect with others. It keeps us informed about the world around us. Social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn have brought individuals from all over the world together, breaking down geographical borders and fostering a genuinely global community.

However, social media comes with its difficulties. With the rise of misinformation, cyberbullying, and privacy problems, it's critical to utilize these platforms properly and be aware of the risks. Students in the academic world are frequently assigned essays about the impact of social media on numerous elements of our lives, such as relationships, politics, and culture. These essays necessitate a thorough comprehension of the subject matter, critical thinking, and the ability to synthesize and convey information clearly and succinctly.

But where do you begin? It can be challenging to know where to start with so much information available. Jenni.ai comes in handy here. Jenni.ai is an AI application built exclusively for students to help them write essays more quickly and easily. Jenni.ai provides students with inspiration and assistance on how to approach their essays with its enormous database of sample essays on a variety of themes, including social media. Jenni.ai is the solution you've been looking for if you're experiencing writer's block or need assistance getting started.

So, whether you're a student looking to better your essay writing skills or want to remain up to date on the latest social media advancements, Jenni.ai is here to help. Jenni.ai is the ideal tool for helping you write your finest essay ever, thanks to its simple design, an extensive database of example essays, and cutting-edge AI technology. So, why delay? Sign up for a free trial of Jenni.ai today and begin exploring the worlds of social networking and essay writing!

Want to learn how to write an argumentative essay? Check out these inspiring examples!

We will provide various examples of social media essays so you may get a feel for the genre.

6 Examples of Social Media Essays

Here are 6 examples of Social Media Essays:

The Impact of Social Media on Relationships and Communication

Introduction:.

The way we share information and build relationships has evolved as a direct result of the prevalence of social media in our daily lives. The influence of social media on interpersonal connections and conversation is a hot topic. Although social media has many positive effects, such as bringing people together regardless of physical proximity and making communication quicker and more accessible, it also has a dark side that can affect interpersonal connections and dialogue.

Positive Effects:

Connecting People Across Distances

One of social media's most significant benefits is its ability to connect individuals across long distances. People can use social media platforms to interact and stay in touch with friends and family far away. People can now maintain intimate relationships with those they care about, even when physically separated.

Improved Communication Speed and Efficiency

Additionally, the proliferation of social media sites has accelerated and simplified communication. Thanks to instant messaging, users can have short, timely conversations rather than lengthy ones via email. Furthermore, social media facilitates group communication, such as with classmates or employees, by providing a unified forum for such activities.

Negative Effects:

Decreased Face-to-Face Communication

The decline in in-person interaction is one of social media's most pernicious consequences on interpersonal connections and dialogue. People's reliance on digital communication over in-person contact has increased along with the popularity of social media. Face-to-face interaction has suffered as a result, which has adverse effects on interpersonal relationships and the development of social skills.

Decreased Emotional Intimacy

Another adverse effect of social media on relationships and communication is decreased emotional intimacy. Digital communication lacks the nonverbal cues and facial expressions critical in building emotional connections with others. This can make it more difficult for people to develop close and meaningful relationships, leading to increased loneliness and isolation.

Increased Conflict and Miscommunication

Finally, social media can also lead to increased conflict and miscommunication. The anonymity and distance provided by digital communication can lead to misunderstandings and hurtful comments that might not have been made face-to-face. Additionally, social media can provide a platform for cyberbullying , which can have severe consequences for the victim's mental health and well-being.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the impact of social media on relationships and communication is a complex issue with both positive and negative effects. While social media platforms offer many benefits, such as connecting people across distances and enabling faster and more accessible communication, they also have a dark side that can negatively affect relationships and communication. It is up to individuals to use social media responsibly and to prioritize in-person communication in their relationships and interactions with others.

The Role of Social Media in the Spread of Misinformation and Fake News

Social media has revolutionized the way information is shared and disseminated. However, the ease and speed at which data can be spread on social media also make it a powerful tool for spreading misinformation and fake news. Misinformation and fake news can seriously affect public opinion, influence political decisions, and even cause harm to individuals and communities.

The Pervasiveness of Misinformation and Fake News on Social Media

Misinformation and fake news are prevalent on social media platforms, where they can spread quickly and reach a large audience. This is partly due to the way social media algorithms work, which prioritizes content likely to generate engagement, such as sensational or controversial stories. As a result, false information can spread rapidly and be widely shared before it is fact-checked or debunked.

The Influence of Social Media on Public Opinion

Social media can significantly impact public opinion, as people are likelier to believe the information they see shared by their friends and followers. This can lead to a self-reinforcing cycle, where misinformation and fake news are spread and reinforced, even in the face of evidence to the contrary.

The Challenge of Correcting Misinformation and Fake News

Correcting misinformation and fake news on social media can be a challenging task. This is partly due to the speed at which false information can spread and the difficulty of reaching the same audience exposed to the wrong information in the first place. Additionally, some individuals may be resistant to accepting correction, primarily if the incorrect information supports their beliefs or biases.

In conclusion, the function of social media in disseminating misinformation and fake news is complex and urgent. While social media has revolutionized the sharing of information, it has also made it simpler for false information to propagate and be widely believed. Individuals must be accountable for the information they share and consume, and social media firms must take measures to prevent the spread of disinformation and fake news on their platforms.

The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health and Well-Being

Social media has become an integral part of modern life, with billions of people around the world using platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter to stay connected with others and access information. However, while social media has many benefits, it can also negatively affect mental health and well-being.

Comparison and Low Self-Esteem

One of the key ways that social media can affect mental health is by promoting feelings of comparison and low self-esteem. People often present a curated version of their lives on social media, highlighting their successes and hiding their struggles. This can lead others to compare themselves unfavorably, leading to feelings of inadequacy and low self-esteem.

Cyberbullying and Online Harassment

Another way that social media can negatively impact mental health is through cyberbullying and online harassment. Social media provides a platform for anonymous individuals to harass and abuse others, leading to feelings of anxiety, fear, and depression.

Social Isolation

Despite its name, social media can also contribute to feelings of isolation. At the same time, people may have many online friends but need more meaningful in-person connections and support. This can lead to feelings of loneliness and depression.

Addiction and Overuse

Finally, social media can be addictive, leading to overuse and negatively impacting mental health and well-being. People may spend hours each day scrolling through their feeds, neglecting other important areas of their lives, such as work, family, and self-care.

In sum, social media has positive and negative consequences on one's psychological and emotional well-being. Realizing this, and taking measures like reducing one's social media use, reaching out to loved ones for help, and prioritizing one's well-being, are crucial. In addition, it's vital that social media giants take ownership of their platforms and actively encourage excellent mental health and well-being.

The Use of Social Media in Political Activism and Social Movements

Social media has recently become increasingly crucial in political action and social movements. Platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram have given people new ways to express themselves, organize protests, and raise awareness about social and political issues.

Raising Awareness and Mobilizing Action

One of the most important uses of social media in political activity and social movements has been to raise awareness about important issues and mobilize action. Hashtags such as #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter, for example, have brought attention to sexual harassment and racial injustice, respectively. Similarly, social media has been used to organize protests and other political actions, allowing people to band together and express themselves on a bigger scale.

Connecting with like-minded individuals

A second method in that social media has been utilized in political activity and social movements is to unite like-minded individuals. Through social media, individuals can join online groups, share knowledge and resources, and work with others to accomplish shared objectives. This has been especially significant for geographically scattered individuals or those without access to traditional means of political organizing.

Challenges and Limitations

As a vehicle for political action and social movements, social media has faced many obstacles and restrictions despite its many advantages. For instance, the propagation of misinformation and fake news on social media can impede attempts to disseminate accurate and reliable information. In addition, social media corporations have been condemned for censorship and insufficient protection of user rights.

In conclusion, social media has emerged as a potent instrument for political activism and social movements, giving voice to previously unheard communities and galvanizing support for change. Social media presents many opportunities for communication and collaboration. Still, users and institutions must be conscious of the risks and limitations of these tools to promote their responsible and productive usage.

The Potential Privacy Concerns Raised by Social Media Use and Data Collection Practices

With billions of users each day on sites like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, social media has ingrained itself into every aspect of our lives. While these platforms offer a straightforward method to communicate with others and exchange information, they also raise significant concerns over data collecting and privacy. This article will examine the possible privacy issues posed by social media use and data-gathering techniques.

Data Collection and Sharing

The gathering and sharing of personal data are significant privacy issues brought up by social media use. Social networking sites gather user data, including details about their relationships, hobbies, and routines. This information is made available to third-party businesses for various uses, such as marketing and advertising. This can lead to serious concerns about who has access to and uses our personal information.

Lack of Control Over Personal Information

The absence of user control over personal information is a significant privacy issue brought up by social media usage. Social media makes it challenging to limit who has access to and how data is utilized once it has been posted. Sensitive information may end up being extensively disseminated and may be used maliciously as a result.

Personalized Marketing

Social media companies utilize the information they gather about users to target them with adverts relevant to their interests and usage patterns. Although this could be useful, it might also cause consumers to worry about their privacy since they might feel that their personal information is being used without their permission. Furthermore, there are issues with the integrity of the data being used to target users and the possibility of prejudice based on individual traits.

Government Surveillance

Using social media might spark worries about government surveillance. There are significant concerns regarding privacy and free expression when governments in some nations utilize social media platforms to follow and monitor residents.

In conclusion, social media use raises significant concerns regarding data collecting and privacy. While these platforms make it easy to interact with people and exchange information, they also gather a lot of personal information, which raises questions about who may access it and how it will be used. Users should be aware of these privacy issues and take precautions to safeguard their personal information, such as exercising caution when choosing what details to disclose on social media and keeping their information sharing with other firms to a minimum.

The Ethical and Privacy Concerns Surrounding Social Media Use And Data Collection

Our use of social media to communicate with loved ones, acquire information, and even conduct business has become a crucial part of our everyday lives. The extensive use of social media does, however, raise some ethical and privacy issues that must be resolved. The influence of social media use and data collecting on user rights, the accountability of social media businesses, and the need for improved regulation are all topics that will be covered in this article.

Effect on Individual Privacy:

Social networking sites gather tons of personal data from their users, including delicate information like search history, location data, and even health data. Each user's detailed profile may be created with this data and sold to advertising or used for other reasons. Concerns regarding the privacy of personal information might arise because social media businesses can use this data to target users with customized adverts.

Additionally, individuals might need to know how much their personal information is being gathered and exploited. Data breaches or the unauthorized sharing of personal information with other parties may result in instances where sensitive information is exposed. Users should be aware of the privacy rules of social media firms and take precautions to secure their data.

Responsibility of Social Media Companies:

Social media firms should ensure that they responsibly and ethically gather and use user information. This entails establishing strong security measures to safeguard sensitive information and ensuring users are informed of what information is being collected and how it is used.

Many social media businesses, nevertheless, have come under fire for not upholding these obligations. For instance, the Cambridge Analytica incident highlighted how Facebook users' personal information was exploited for political objectives without their knowledge. This demonstrates the necessity of social media corporations being held responsible for their deeds and ensuring that they are safeguarding the security and privacy of their users.

Better Regulation Is Needed

There is a need for tighter regulation in this field, given the effect, social media has on individual privacy as well as the obligations of social media firms. The creation of laws and regulations that ensure social media companies are gathering and using user information ethically and responsibly, as well as making sure users are aware of their rights and have the ability to control the information that is being collected about them, are all part of this.

Additionally, legislation should ensure that social media businesses are held responsible for their behavior, for example, by levying fines for data breaches or the unauthorized use of personal data. This will provide social media businesses with a significant incentive to prioritize their users' privacy and security and ensure they are upholding their obligations.

In conclusion, social media has fundamentally changed how we engage and communicate with one another, but this increased convenience also raises several ethical and privacy issues. Essential concerns that need to be addressed include the effect of social media on individual privacy, the accountability of social media businesses, and the requirement for greater regulation to safeguard user rights. We can make everyone's online experience safer and more secure by looking more closely at these issues.

In conclusion, social media is a complex and multifaceted topic that has recently captured the world's attention. With its ever-growing influence on our lives, it's no surprise that it has become a popular subject for students to explore in their writing. Whether you are writing an argumentative essay on the impact of social media on privacy, a persuasive essay on the role of social media in politics, or a descriptive essay on the changes social media has brought to the way we communicate, there are countless angles to approach this subject.

However, writing a comprehensive and well-researched essay on social media can be daunting. It requires a thorough understanding of the topic and the ability to articulate your ideas clearly and concisely. This is where Jenni.ai comes in. Our AI-powered tool is designed to help students like you save time and energy and focus on what truly matters - your education. With Jenni.ai , you'll have access to a wealth of examples and receive personalized writing suggestions and feedback.

Whether you're a student who's just starting your writing journey or looking to perfect your craft, Jenni.ai has everything you need to succeed. Our tool provides you with the necessary resources to write with confidence and clarity, no matter your experience level. You'll be able to experiment with different styles, explore new ideas , and refine your writing skills.

So why waste your time and energy struggling to write an essay on your own when you can have Jenni.ai by your side? Sign up for our free trial today and experience the difference for yourself! With Jenni.ai, you'll have the resources you need to write confidently, clearly, and creatively. Get started today and see just how easy and efficient writing can be!

Try Jenni for free today

Create your first piece of content with Jenni today and never look back

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Social Media Is a Threat to Privacy, Essay Example

Pages: 3

Words: 860

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

Introduction

Social networking has been a global phenomenon with the proliferation of various social networking platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. In many ways, social media has replaced conventional modes of communication such as the telephone and email. People can keep in touch with others by sharing experiences and photographs, and most cases exchange personal information. Social media users usually post private information as part of the process of knowing one another. Since social media is associated with having a large number of users unknown to the client, there is an increased risk of exposing personal details to cybercriminals.

Social media is a threat to privacy

Social media has increased privacy concerns with online platforms. Although they are effective in connecting with family and friend, social media can also endanger private information. Individuals create social media profiles that may expose their private information. According to research conducted by Carnegie Mellon University, information found in social media is sufficient to guess one’s social security number, which can lead to identity theft. With the advent of mobile banking applications, more people are login their sensitive data to smartphones, which can endanger their privacy.

Another group whose privacy is in danger is teenagers. Teenagers post a significant amount of information online, which makes it vitally for them to understand the people they share information with or use privacy settings. However, most teenagers are interested with capturing the attention of their peers and in the process posting information that may enhance their status. This information may not seem harmful, but it can be exploited by cyber criminals to get access to the parents.

Several articles have argued about the threat of privacy in online platforms such as social media. In “online privacy: current health 2 by given (2009),” the author argues that online predators can figure out information posted in online platforms, which can be used against the user. Additionally, employers can use the online platform to check out their employees. With the proliferation of electronic health registers, cyber criminals can access an individual’s health information. It presents a significant danger to the individuals concerned because such registers contain vital information such as social security number and insurance details.

In her article titled” should you panic about online privacy?” Palmer (2010) notes that online platforms are a threat to privacy and individual must take measures to protect their personal data. Due to the threat posed by online environments to privacy, Palmer suggests various strategies that user can use to safeguard their privacy. One way of doing this is by removing the birth year from a personal profile in social media networks because the full birth year is often used by banks to categorize their clients. Cyber criminals can use such information to access online banking systems that can compromise user’s safety. Another suggestion given by Palmer is to use antivirus and anti-spyware. These techniques will prevent criminals from exploiting them to access confidential information.

In the piece carried by the New Yorker tiled “the face of Facebook” by José Vargas may present information about Mark Zuckerberg that is public domain, it illustrates how Facebook profiles reveal private and confidential information to virtually anyone on the site. FACEBOOK is a directory of global citizens that affords people the chance to create public identities. Friends can access this information; friends of friends can also access some while some information is also available to anyone interested in them. Although the company has changed it privacy policies severally, it still exposes private information in several ways. From Zuckerberg’s profile, it is possible to know that he has three sisters, where he schooled in, he favorite comedian and musicians, and his interests. His friends can also access his cell-phone number and email address. Additionally, the addition of a feature known as Places, which allows users to mark their location means that someone interested in Zuckerberg’s location can know it anytime. The article by Vargas reveals how easy it is to access one’s private information in Facebook.

Plagiarism, which is using another person’s ideas or creations without giving credit to that person, is another concern in social media. Individuals take information from other sources or individuals and use them as their own, which a common practice in social media. The lack of attribution and fabrication of content are the real issues because users seldom give credit to the source of the content. Despite the fact that social media is for connecting with friends and family, it has been used as social aggregators, which makes it important to give links to the sources of the content.

Social media platforms raise concerns over privacy issues because others can exploit information that is innocently posted on these sites. Cyber criminals can exploit the information to harm the user. It is important to note that different people can access information posted online. Users must take significant steps to protect their information by using anti-spyware software and emitting sensitive information in their profiles.

Given M. (2008). online privacy. Current health 2 . Retrieved from academic search complete.

Palmer L. (2010, 08) should you panic about online privacy? Redbook , Vol. 215 Issue 2, p130

Vargas,J.A. ( 2010, sep20). The face of Facebook. The New Yorker. Retrieved from http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/09/20/the-face-of-facebook

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Vitamin C Experiment, Essay Example

The Professionalization of Ujwai Bharati, Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Why Submit?

- About Communication Theory

- About International Communication Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

The Social Media Privacy Model: Privacy and Communication in the Light of Social Media Affordances

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Sabine Trepte, The Social Media Privacy Model: Privacy and Communication in the Light of Social Media Affordances, Communication Theory , Volume 31, Issue 4, November 2021, Pages 549–570, https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtz035

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Privacy has been defined as the selective control of information sharing, where control is key. For social media, however, an individual user’s informational control has become more difficult. In this theoretical article, I review how the term control is part of theorizing on privacy, and I develop an understanding of online privacy with communication as the core mechanism by which privacy is regulated. The results of this article’s theoretical development are molded into a definition of privacy and the social media privacy model. The model is based on four propositions: Privacy in social media is interdependently perceived and valued. Thus, it cannot always be achieved through control. As an alternative, interpersonal communication is the primary mechanism by which to ensure social media privacy. Finally, trust and norms function as mechanisms that represent crystallized privacy communication. Further materials are available at https://osf.io/xhqjy/

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1468-2885

- Copyright © 2024 International Communication Association

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Social Media and Privacy

- Open Access

- First Online: 09 February 2022

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Xinru Page 7 ,

- Sara Berrios 7 ,

- Daricia Wilkinson 8 &

- Pamela J. Wisniewski 9

17k Accesses

4 Citations

4 Altmetric

With the popularity of social media, researchers and designers must consider a wide variety of privacy concerns while optimizing for meaningful social interactions and connection. While much of the privacy literature has focused on information disclosures, the interpersonal dynamics associated with being on social media make it important for us to look beyond informational privacy concerns to view privacy as a form of interpersonal boundary regulation. In other words, attaining the right level of privacy on social media is a process of negotiating how much, how little, or when we desire to interact with others, as well as the types of information we choose to share with them or allow them to share about us. We propose a framework for how researchers and practitioners can think about privacy as a form of interpersonal boundary regulation on social media by introducing five boundary types (i.e., relational, network, territorial, disclosure, and interactional) social media users manage. We conclude by providing tools for assessing privacy concerns in social media, as well as noting several challenges that must be overcome to help people to engage more fully and stay on social media.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Privacy and Empowerment in Connective Media

Privacy in Social Information Access

The Socio-economic Impacts of Social Media Privacy and Security Challenges

1 introduction.

The way people communicate with one another in the twenty-first century has evolved rapidly. In the 1990s, if someone wanted to share a “how-to” video tutorial within their social networks, the dissemination options would be limited (e.g., email, floppy disk, or possibly a writeable compact disc). Now, social media platforms, such as TikTok, provide professional grade video editing and sharing capabilities that give users the potential to both create and disseminate such content to thousands of viewers within a matter of minutes. As such, social media has steadily become an integral component for how people capture aspects of their physical lives and share them with others. Social media platforms have gradually altered the way many people live [ 1 ], learn [ 2 , 3 ], and maintain relationships with others [ 4 ].

Carr and Hayes define social media as “Internet-based channels that allow users to opportunistically interact and selectively self-present, either in real time or asynchronously, with both broad and narrow audiences who derive value from user-generated content and the perception of interaction with others” [ 5 ]. Social media platforms offer new avenues for expressing oneself, experiences, and emotions with broader online communities via posts, tweets, shares, likes, and reviews. People use these platforms to talk about major milestones that bring happiness (e.g., graduation, marriage, pregnancy announcements), but they also use social media as an outlet to express grief and challenges, and to cope with crises [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]. Many scholars have highlighted the host of positive outcomes from interpersonal interactions on social media including social capital, self-esteem, and personal well-being [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Likewise, researchers have also shed light on the increased concerns over unethical data collection and privacy abuses [ 13 , 14 ].

This chapter highlights the privacy issues that must be addressed in the context of social media and provides guidance on how to study and design for social media privacy. We first provide an overview of the history of social media and its usage. Next, we highlight common social media privacy concerns that have arisen over the years. We also point out how scholars have identified and sought to predict privacy behavior, but many efforts have failed to adequately account for individual differences. By reconceptualizing privacy in social media as a boundary regulation, we can explain these gaps from previous one-size-fits-all approaches and provide tools for measuring and studying privacy violations. Finally, we conclude with a word of caution about the consequences of ignoring privacy concerns on social media.

2 A Brief History of Social Media

Section highlights.

Social media use has quickly increased over the past decade and plays a key role in social, professional, and even civic realms. The rise of social media has led to “networked individualism.”

This enables people to access a wider variety of specialized relationships , making it more likely they can meet a variety of needs. It also allows people to project their voice to a wider audience.

However, people have more frequent turnover in their social networks , and it takes much more effort to maintain social relations and discern (mis)information and intention behind communication.

The initial popularity of social media harkened back to the historical rise of social network sites (SNSs). The canonical definition of SNSs is attributed to Boyd and Ellison [ 15 ] who differentiate SNSs from other forms of computer-mediated communication. According to Boyd and Ellison, SNS consists of (1) profiles representing users and (2) explicit connections between these profiles that can be traversed and interacted with. A social networking profile is a self-constructed digital representation of oneself and one’s social relationships. The content of these profiles varies by platform from profile pictures to personal information such as interests, demographics, and contact information. Visibility also varies by platform and often users have some control over who can see their profile (e.g., everyone or “friends”). Most SNSs also provide a way to leave messages on another’s profile, such as posting to someone’s timeline on Facebook or sending a mention or direct message to someone on Twitter.

Public interest and research initially focused on a small subset of SNSs (e.g., Friendster [ 16 ] and MySpace [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]), but the past decade has seen the proliferation of a much broader range of social networking technologies, as well as an evolution of SNSs into what Kane et al. term social media networks [ 20 ]. This extended definition emphasizes the reach of social media content beyond a single platform. It acknowledges how the boundedness of SNSs has become blurred as platform functionality that was once contained in a single platform, such as “likes,” are now integrated across other websites, third parties, and mobile apps.

Over the past decade, SNSs and social media networks have quickly become embedded in many facets of personal, professional, and social life. In that time, these platforms became more commonly known as “social media.” In the USA, only 5% of adults used social media in 2005. By 2011, half of the US adult population was using social media, and 72% were social users by 2019 [ 21 ]. MySpace and Facebook dominated SNS research about a decade ago, but now other social media platforms, such as YouTube, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, Kik, TikTok, and others, are popular choices among social media users. The intensity of use also has drastically increased. For example, half of Facebook users log on several times a day, and three-quarters of Facebook users are active on the platform at least daily [ 21 ]. Worldwide, Facebook alone has 1.59 billion users who use it on a daily basis and 2.41 billion using it at least monthly [ 22 ]. About half of the users of other popular platforms such as Snapchat, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube also report visiting those sites daily. Around the world, there are 4.2 billion users who spend a cumulative 10 billion hours a day on social networking sites [ 23 ]. However, different social networking sites are dominant in different cultures. For example, the most popular social media in China, WeChat (inc. Wēixìn 微信), has 1.213 billion monthly users [ 23 ].