Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

5 What is an Educational Philosophy?

Jennifer Beasley and Myra Haulmark

What makes a teacher? Teaching is like a salad. Think about it. If you were to attend a party for any given holiday, the number of and variations to each salad recipe that might be present for consumption could outnumber those present at the party. There are so many different ways to teach, varying circumstances to take into account, and philosophies to apply to each classroom. And what better way to have a positive impact on the world than to offer knowledge for consumption? The term ‘teacher’ can be applied to anyone who imparts knowledge of any topic, but it is generally more focused on those who are hired to do so (teach, n.d., n.p.). In imparting knowledge to our students, it is inevitable that we must take into account our own personal philosophies or pedagogies, and determine not only how we decide what our philosophies are, but also how those impact our consumers.

Objectives and Key Terms

In this chapter, readers will…

- Define, describe, and identify the four branches of educational philosophy

- Outline at least two educational philosophies that influence our schools

- Explain how educational philosophies influence the choice of curriculum and classroom instructional practices

- Develop a personal philosophy concerning teaching and learning

Key terms in the chapter are…

Constructivism

Perennialism, essentialism, progressivism.

- Romanticism

- Behaviorism

Lessons in Pedagogy

What, exactly, are education philosophies? According to Thelma Roberson (2000), most prospective teachers confuse their beliefs with the ideas of teaching (p. 6). Education philosophies, then, are not what you want to do in class to aid learning, but why you do them and how they work. For example, Roberson’s students state they “want to use cooperative learning techniques” in their classroom. The question posed is, why? “[I]s cooperative learning a true philosophy or is it something you do in the classroom because of your belief about the way children learn?” (Roberson, 2000, p. 6). Philosophies need to translate ideas into action – if you want to use certain techniques, then you need to understand how they are effective in the classroom to create that portion of your education philosophy. It helps to have an overview of the various schools out there.

- Perennialism – focuses on human concerns that have caused concern for centuries, revealed through ‘great works’ (Ornstein, 2003, p. 110) It focuses on great works of art, literature and enduring ideas.

- Essentialism – Emphasizes skills and subjects that are needed by all in a productive society. This is the belief in “Back to Basics”. Rote learning is emphasized and

- Progressivism – Instruction features problem-solving and group activities – The instructor acts as a facilitator as opposed to a leader (Ornstein, 2003, p. 110)

- Social Reconstructionism – Instruction that focuses on significant social and economic problems in an effort to solve them (Ornstein, 2003, pg.110)

- Existentialism – Classroom dialogue stimulates awareness – each person creates an awareness gleaned from discussion and encourages deep personal reflection on his or her convictions (Ornstein, 2003, p. 108).

- The knowledge that has been passed through the ages should be continued as the basis of the curriculum, like the classic works of Plato and Einstein.

- Reason, logic, and analytical thought are valued and encouraged

- Only information that stood the test of time is relevant. It is believed these prepare students for life and help to develop rational thinking.

- The classes most likely to be considered under this approach would be history, science, math, and religion classes (Educational Philosophies in the Classroom, pg.1).

- Essentialists believe that there is a universal pool of knowledge needed by all students.

- The fundamentals of teaching are the basis of the curriculum: math, science, history, foreign language, and English. Vocational classes are not seen as a necessary part of educational training.

- Classrooms are formal, teacher-centered, and students are passive learners.

- Evaluations are predominately through testing, and there are few, if any, projects or portfolios.

Watch the following video for a little more about this philosophy:

- This is a student-centered form of instruction where students follow the scientific method of questioning and searching for the answer.

- Evaluations include projects and portfolios.

- Current events are used to keep students interested in the required subject matter.

- Students are active learners as opposed to passive learners.

- The teacher is a facilitator rather than the center of the educational process.

- Student input is encouraged, and students are asked to find their interpretation of the answer, have a choice in projects and assignments. (Educational Philosophies in the classroom, pg.1).

- Real-world problem solving emphasized.

- Subjects are integrated.

- Interaction among students.

- Students have a voice in the classroom.

Social Reconstructivism

- This student-centered philosophy strives to instill a desire to make the world a better place.

- It places a focus on controversial world issues and uses current events as a springboard for the thinking process.

- These students are taught the importance of working together to bring about change.

- These teachers incorporate what is happening in the world with what they are learning in the classroom (Educational Philosophies in the Classroom, pg.1).

What do you think?

Additional Beliefs in Regards to Teaching/Learning

Active participation is the key to this teaching style. Students are free to explore their own ideas and share concepts with one another in nontraditional ways. “Hands-on activity […] is the most effective way of learning and is considered true learning” (Educational Philosophies in the Classroom, pg.1).

What is Constructivism?

The root word of Constructivism is “construct.” Basically, Constructivism is the theory that knowledge must be constructed by a person, not just transmitted to the person. People construct knowledge by taking new information and integrating it with their own pre-existing knowledge (Cooper, 2007; Woolfolk, 2007). It means they are actively involved in seeking out information, creating projects, and working with material being presented versus just sitting and listening to someone “talk at them”.

Jean Piaget’s Theory of Constructivism

Jean Piaget was one of the major constructivists in past history. His theory looks at how people construct knowledge cognitively. In Piaget’s theory, everybody has schemata. These are the categories of information we create to organize the information we take in. For example, “food” is one schema we may have. We have a variety of information on food. It can be organized into different food groups such as the following: bread/pasta, fruits, vegetables, meats, dairy, and sweets (Kail & Cavanaugh, 2007). We use these schemas to help us “make sense” of what we see, hear and experience, and integrate this information into our knowledge bank.

According to Piaget’s theory, one way people construct knowledge is through assimilation. People assimilate when they incorporate new knowledge and information into pre-existing schemes. Here is an example: A child sees a car and learns that it can be called a vehicle. Then the child sees a motorcycle and learns that it can be called a vehicle as well. Then the child sees a truck and calls it a vehicle. Basically, the child developed a schema for “vehicles” and incorporated trucks into that schema (Kail & Cavanaugh, 2007).

Another way people construct knowledge, according to Piaget’s theory, is through accommodation. People accommodate when they modify or change their pre-existing schemes. Here is an example.: A child sees a dog (a furry four-legged animal) and learns that it can be called a pet. Then the child sees a cat (a furry four-legged animal) and learns that it can be called a pet as well. Then the child sees a raccoon (also a furry four-legged animal) and calls it a pet. Afterward, the child learns from his or her parents that a raccoon is not a pet. At first, the child develops a schema for “pet” which includes all furry four-legged animals. Then the child learns that not all furry four-legged animals are pets. Because of this, the child needs to accommodate his or her schema for “pet.” According to Piaget, people learn through a balance of assimilation and accommodation (Kail & Cavanaugh, 2007).

Lev Vygotsky’s Theory of Constructivism

Lev Vygotsky was another major constructivist in past history. While Jean Piaget’s theory is a cognitive perspective, Vygotsky’s theory is a sociocultural perspective. His theory looks at how people construct knowledge by collaborating with others. In Vygotsky’s theory, people learn and construct knowledge within the Zone of Proximal Development. People have an independent level of performance where they can do things independently. Likewise, people have a frustration level where tasks are too difficult to be able to perform on their own. In between, there is an instructional level where they can do things above the independent level with the help and guidance of others. The range, or zone, between the independent and frustration levels is the Zone of Proximal Development (Cooper, 2007; Kail & Cavanaugh, 2007; Woolfolk, 2007).

In the Zone of Proximal Development, assistance needs to be given by another person. This assistance, help, or guidance is known as scaffolding. Because the zone has a range, assistance needs to be given, but not too much. If not enough assistance is given, a person may not be able to learn the task. On the other hand, if too much assistance is given, the person may not be able to fully construct the newly acquired information into knowledge. For example, a child needs help doing math homework. With no help, the child may not be able to do it. With too much help, the homework is done for the child, so the child may not fully understand the math homework anyway (Cooper, 2007; Kail & Cavanaugh, 2007; Woolfolk, 2007).

Constructivism in the Classroom

In the classroom, the teacher can u se Constructivism to help teach the students. The teacher can base the instruction on the cognitive strategies, experiences, and culture of the students. The teacher can make the instruction interesting by correlating it with real-life applications, especially applications within the students’ own communities. Students can work and collaborate together during particular activities. The teacher can provide feedback for the students so they know what they can do independently and know what they need help with. New concepts can be related to the students’ prior knowledge. The teacher can also explain how new concepts can be used in different contexts and subjects. All these ideas are based on Constructivism (Sherman & Kurshan, 2005).

Research shows that constructivist teaching can be effective. According to research conducted by Jong Suk Kim at Chungnum National University in Korea, constructivist teaching is more effective than traditional teaching when looking at the students’ academic achievement. The research also shows that students have some preference for constructivist teaching (Kim, 2005). Again, whe n the theory of Constructivism is actually applied in the classroom, it can be effective for teaching students.

It is not the sole responsibility of the teachers to educate the students. According to Constructivism, students have some responsibilities when learning. A student may be quick to blame the teacher for not understanding the material, but it could be the case that the student is not doing everything he or she could be doing. Because knowledge is constructed, not transmitted, students need to make an effort to assimilate, accommodate, and make sense of information. They also need to make an effort to collaborate with others, especially if they are having a hard time understanding the information.

Four Philosophies in Assessment

In addition, the ‘constructivist’ school of philosophy, rooted in the Pragmatic pedagogy and branched off from the ‘Social Reconstructivist’ school, has gained much popularity. Around the turn of the century (the early 1990s), many teachers felt the rote memorization and mindless routine that was common was ineffective and began to look for alternate ways to reach their students (Ornstein, 2003, p. 111). Through the constructivist approach, “students “construct” knowledge through an interaction between what they already think and know and with new ideas and experiences” (Roberson, 2000, p. 8). This is an active learning process that leads to a deeper understanding of the concepts presented in class and is based on the abilities and readiness of the children rather than set curriculum guidelines (Ornstein, 2003, p. 112). Constructivism “emphasizes socially interactive and process-oriented ‘hands-on’ learning in which students work collaboratively to expand and revise their knowledge base” (Ornstein, 2003, p. 112). Essentially, the knowledge that is shaped by experience is reconstructed or altered, to assist the student in understanding new concepts (Ornstein, 2003, p. 112). You, as the teacher, help the students build the scaffolding they need to maintain the information even after the test is taken and graded.

Creating Your Philosophy

Educators continue to build upon their philosophy over their careers. They often choose elements from various philosophies and integrate them into their own. When identifying a philosophy, here are things to consider:

- What is the purpose of education?

- What do you believe should be taught?

- How do you think the curriculum should be taught?

- What is your role as the teacher?

- What is the role of the student?

- What is the value of teacher-centered instruction and student-centered instruction; where and when do you incorporate each?

What philosophy are you leaning towards? Take the following quiz to find out!

Make a copy and take the quiz on your own:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1riF81PX9IDZLlQ4K0rBpkZMPlIA5cQ-twb-Soz6ygnA/copy

The following resources are provided when “digging deeper” into the chapter.

- What is your Educational Philosophy? https://www.edutopia.org/blog/what-your-educational-philosophy-ben-johnson

- Four Philosophies and Their Applications to Education https://docs.google.com/document/d/149dx9pNRqIYp-EAYVHgXkxUV_u2cnmbGmvMgS863P4o/edit

Modified from “Foundations of Education and Instructional Assessment” by Dionne Nichols licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Introduction to Education Copyright © 2021 by Jennifer Beasley and Myra Haulmark is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

Only 100 Left! Get FREE Timeline Posters Sent Right to Your School ✨

40 Philosophy of Education Examples, Plus How To Write Your Own

Learn how to define and share your teaching philosophy.

These days, it’s become common for educators to be asked what their personal teaching philosophy is. Whether it’s for a job interview, a college class, or to share with your principal, crafting a philosophy of education can seem like a daunting task. So set aside some time to consider your own teaching philosophy (we’ll walk you through it), and be sure to look at philosophy of education examples from others (we’ve got those too!).

What is a philosophy of education?

Before we dive into the examples, it’s important to understand the purpose of a philosophy of education. This statement will provide an explanation of your teaching values and beliefs. Your teaching philosophy is ultimately a combination of the methods you studied in college and any professional experiences you’ve learned from since. It incorporates your own experiences (negative or positive) in education.

Many teachers have two versions of their teaching philosophy: a long form (a page or so of text) and a short form. The longer form is useful for job application cover letters or to include as part of your teacher portfolio. The short form distills the longer philosophy into a couple of succinct sentences that you can use to answer teacher job interview questions or even share with parents.

What’s the best teaching philosophy?

Here’s one key thing to remember: There’s no one right answer to “What’s your teaching philosophy?” Every teacher’s will be a little bit different, depending on their own teaching style, experiences, and expectations. And many teachers find that their philosophies change over time, as they learn and grow in their careers.

When someone asks for your philosophy of education, what they really want to know is that you’ve given thought to how you prepare lessons and interact with students in and out of the classroom. They’re interested in finding out what you expect from your students and from yourself, and how you’ll apply those expectations. And they want to hear examples of how you put your teaching philosophy into action.

What’s included in strong teaching philosophy examples?

Depending on who you ask, a philosophy of education statement can include a variety of values, beliefs, and information. As you build your own teaching philosophy statement, consider these aspects, and write down your answers to the questions.

Purpose of Education (Core Beliefs)

What do you believe is the purpose of teaching and learning? Why does education matter to today’s children? How will time spent in your classroom help prepare them for the future?

Use your answers to draft the opening statement of your philosophy of education, like these:

- Education isn’t just about what students learn, but about learning how to learn.

- A good education prepares students to be productive and empathetic members of society.

- Teachers help students embrace new information and new ways of seeing the world around them.

- A strong education with a focus on fundamentals ensures students can take on any challenges that come their way.

- I believe education is key to empowering today’s youth, so they’ll feel confident in their future careers, relationships, and duties as members of their community.

- Well-educated students are open-minded, welcoming the opinions of others and knowing how to evaluate information critically and carefully.

Teaching Style and Practices

Do you believe in student-led learning, or do you like to use the Socratic method instead? Is your classroom a place for quiet concentration or sociable collaboration? Do you focus on play-based learning, hands-on practice, debate and discussion, problem-solving, or project-based learning? All teachers use a mix of teaching practices and styles, of course, but there are some you’re likely more comfortable with than others. Possible examples:

- I frequently use project-based learning in my classrooms because I believe it helps make learning more relevant to my students. When students work together to address real-world problems, they use their [subject] knowledge and skills and develop communication and critical thinking abilities too.

- Play-based learning is a big part of my teaching philosophy. Kids who learn through play have more authentic experiences, exploring and discovering the world naturally in ways that make the process more engaging and likely to make a lasting impact.

- In my classroom, technology is key. I believe in teaching students how to use today’s technology in responsible ways, embracing new possibilities and using technology as a tool, not a crutch.

- While I believe in trying new teaching methods, I also find that traditional learning activities can still be effective. My teaching is mainly a mix of lecture, Socratic seminar, and small-group discussions.

- I’m a big believer in formative assessment , taking every opportunity to measure my students’ understanding and progress. I use tools like exit tickets and Kahoot! quizzes, and watch my students closely to see if they’re engaged and on track.

- Group work and discussions play a major role in my instructional style. Students who learn to work cooperatively at a young age are better equipped to succeed in school, in their future careers, and in their communities.

Students and Learning Styles

Why is it important to recognize all learning styles? How do you accommodate different learning styles in your classroom? What are your beliefs on diversity, equity, and inclusion? How do you ensure every student in your classroom receives the same opportunities to learn? How do you expect students to behave, and how do you measure success? ADVERTISEMENT

Sample teaching philosophy statements about students might sound like this:

- Every student has their own unique talents, skills, challenges, and background. By getting to know my students as individuals, I can help them find the learning styles that work best for them, now and throughout their education.

- I find that motivated students learn best. They’re more engaged in the classroom and more diligent when working alone. I work to motivate students by making learning relevant, meaningful, and enjoyable.

- We must give every student equal opportunities to learn and grow. Not all students have the same support outside the classroom. So as a teacher, I try to help bridge gaps when I see them and give struggling students a chance to succeed academically.

- I believe every student has their own story and deserves a chance to create and share it. I encourage my students to approach learning as individuals, and I know I’m succeeding when they show a real interest in showing up and learning more every day.

- In my classroom, students take responsibility for their own success. I help them craft their own learning goals, then encourage them to evaluate their progress honestly and ask for help when they need it.

- To me, the best classrooms are those that are the most diverse. Students learn to recognize and respect each other’s differences, celebrating what each brings to the community. They also have the opportunity to find common ground, sometimes in ways that surprise them.

How do I write my philosophy of education?

Think back to any essay you’ve ever written and follow a similar format. Write in the present tense; your philosophy isn’t aspirational, it’s something you already live and follow. This is true even if you’re applying for your first teaching job. Your philosophy is informed by your student teaching, internships, and other teaching experiences.

Lead with your core beliefs about teaching and learning. These beliefs should be reflected throughout the rest of your teaching philosophy statement.

Then, explain your teaching style and practices, being sure to include concrete examples of how you put those practices into action. Transition into your beliefs about students and learning styles, with more examples. Explain why you believe in these teaching and learning styles, and how you’ve seen them work in your experiences.

A long-form philosophy of education statement usually takes a few paragraphs (not generally more than a page or two). From that long-form philosophy, highlight a few key statements and phrases and use them to sum up your teaching philosophy in a couple of well-crafted sentences for your short-form teaching philosophy.

Still feeling overwhelmed? Try answering these three key questions:

- Why do you teach?

- What are your favorite, tried-and-true methods for teaching and learning?

- How do you help students of all abilities and backgrounds learn?

If you can answer those three questions, you can write your teaching philosophy!

Short Philosophy of Education Examples

We asked real educators in the We Are Teachers HELPLINE group on Facebook to share their teaching philosophy examples in a few sentences . Here’s what they had to say:

I am always trying to turn my students into self-sufficient learners who use their resources to figure it out instead of resorting to just asking someone for the answers. —Amy J.

My philosophy is that all students can learn. Good educators meet all students’ differentiated learning needs to help all students meet their maximum learning potential. —Lisa B.

I believe that all students are unique and need a teacher that caters to their individual needs in a safe and stimulating environment. I want to create a classroom where students can flourish and explore to reach their full potential. My goal is also to create a warm, loving environment, so students feel safe to take risks and express themselves. —Valerie T.

In my classroom, I like to focus on the student-teacher relationships/one-on-one interactions. Flexibility is a must, and I’ve learned that you do the best you can with the students you have for however long you have them in your class. —Elizabeth Y

I want to prepare my students to be able to get along without me and take ownership of their learning. I have implemented a growth mindset. —Kirk H.

My teaching philosophy is centered around seeing the whole student and allowing the student to use their whole self to direct their own learning. As a secondary teacher, I also believe strongly in exposing all students to the same core content of my subject so that they have equal opportunities for careers and other experiences dependent upon that content in the future. —Jacky B.

All children learn best when learning is hands-on. This works for the high students and the low students too, even the ones in between. I teach by creating experiences, not giving information. —Jessica R.

As teachers, it’s our job to foster creativity. In order to do that, it’s important for me to embrace the mistakes of my students, create a learning environment that allows them to feel comfortable enough to take chances, and try new methods. —Chelsie L.

I believe that every child can learn and deserves the best, well-trained teacher possible who has high expectations for them. I differentiate all my lessons and include all learning modalities. —Amy S.

All students can learn and want to learn. It is my job to meet them where they are and move them forward. —Holli A.

I believe learning comes from making sense of chaos. My job is to design work that will allow students to process, explore, and discuss concepts to own the learning. I need to be part of the process to guide and challenge perceptions. —Shelly G.

I want my students to know that they are valued members of our classroom community, and I want to teach each of them what they need to continue to grow in my classroom. —Doreen G.

Teach to every child’s passion and encourage a joy for and love of education and school. —Iris B.

I believe in creating a classroom culture of learning through mistakes and overcoming obstacles through teamwork. —Jenn B.

It’s our job to introduce our kids to many, many different things and help them find what they excel in and what they don’t. Then nurture their excellence and help them figure out how to compensate for their problem areas. That way, they will become happy, successful adults. —Haley T.

Longer Philosophy of Education Examples

Looking for longer teaching philosophy examples? Check out these selections from experienced teachers of all ages and grades.

- Learning To Wear the Big Shoes: One Step at a Time

- Nellie Edge: My Kindergarten Teaching Philosophy

- Faculty Focus: My Philosophy of Teaching

- Robinson Elementary School: My Teaching Philosophy

- David Orace Kelly: Philosophy of Education

- Explorations in Higher Education: My Teaching Philosophy Statement

- University of Washington Medical School Faculty Teaching Philosophy Statements

Do you have any philosophy of education examples? Share them in the We Are Teachers HELPLINE Group on Facebook!

Want more articles and tips like this be sure to subscribe to our newsletters to find out when they’re posted..

You Might Also Like

15 Inspiring Teaching Portfolio Examples (Plus How To Create Your Own)

Show them what you've got. Continue Reading

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

3 Educational Philosophies

“Theories are more than academic words that folx with degrees throw around at coffee shops and poetry slams; they work to explain to us how the world works, who the world denies, and how the structures uphold oppression.”

Bettina L. Love, 2019

Learning Objectives

- Learn the four key Educational Philosophies

- Explore non-systemically dominant educational systems and their philosophical roots

- Compare how the privileging of educational thought and philosophy in the US is based in social, political, and economic power

- Develop an initial personal philosophy of education through self-reflection and self examination taking into account narratives and counterstories

Activity – Educational Philosophy Assessment

In order to start reflecting on your own philosophy of education, complete the following:

- Educational Philosophies Self Assessment – https://evaeducation.weebly.com/uploads/1/9/6/9/19692577/self_assessment.pdf

- Scoring Guide for the Self Assessment: https://evaeducation.weebly.com/uploads/1/9/6/9/19692577/self_assessment_scoring_guide.pdf

What does this survey reveal about your underlying philosophy?

Do you agree or disagree with this assessment? Explain.

What might this survey reveal with your reasons in becoming a teacher?

Foundations of Educational Philosophy

Pause and Ponder – Education

You may have heard comments implying that education in the United States is not political, separate from religion, and accessible to everyone. The reality is that from its early existence in the western hemisphere in the 1600s, it was indeed political, religious, and accessible only to a select few. These traits continue to influence the evolution of education in the United States today.

The education system in the United States is a social institution. A social institution is a pattern of behaviors and social arrangements that have evolved to meet the needs of society. Quite often, how those needs are defined in official conversations is dependent on who has the social, economic, and legal power to do the defining.

Given this, and since the current system in the US was derived from a system that was explicitly designed to reproduce wealth and privilege for societal elites, it should be no surprise that the foundational theorists upon which the US education rests are representative of a narrow range of perspectives on education. Many educational approaches, perspectives, and philosophies have been neglected in the development of the US system. For instance, the educational system in the US is not rooted at all in the philosophies of Aztec or Mayan civilizations. Nor does it include understandings about teaching, learning, or intellectual growth from Muslim, Hindu, or Yoruba societies. It is accurate to say the US system of education and the philosophies on which it rests are decidedly Eurocentric.

Critical Lens – Eurocentrism

Eurocentrism (also Eurocentricity) is a worldview that is centered on or privileges European-based civilization or a biased view that favors it over nonEuropean-based civilizations.

In order to understand the educational system in the US in a way that supports educators in meeting the needs of all students, we offer the following orientation to the educational philosophies on which this system was founded.

A philosophy grounds or guides practice in the study of existence and knowledge while developing an ontology (the study of being) on what it means for something or someone to be—or exist. Educational philosophy, then, provides a foundation which constructs and guides the ways knowledge is generated and passed on to others. Therefore, when thinking and reflecting about your own philosophy of education, you need to acknowledge your values, beliefs and attitudes towards the educational system, as this will guide your practice. Therefore, it is of critical importance that teachers begin to develop a clear understanding of philosophical traditions and how the philosophical underpinnings inform their educational philosophies. Philosophies need to translate ideas into action. If you want to use certain techniques, then you need to understand how they are effective in the classroom to create that portion of your education philosophy.

Over the course of history, philosophy has experienced several paradigm shifts that influence teaching and learning. Philosophical traditions from the 19th century helped anchor the early foundations of educational philosophy and the development of public education in Europe and the United States.

Activity – Think and Reflect

Think and reflect on the following guiding questions:

- What does being a teacher mean to you?

- What are the skills that, from your perspective, effective teachers have?

- What should be taught?

- How should it be taught?

- What is knowledge?

- Why is it important to establish a trusting relationships between students, teachers and the community?

Whether you are aware or not, you have begun writing philosophical statements about education and being a teacher.

3.1 Philosophical Perspectives of Education

As students ourselves, we may have a particular notion of what schooling is and should be as well as what teachers do and should do. In his book entitled Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study, Dan Lortie (1975) called this the “apprenticeship of observation” (p. 62). Many people who pursue teaching think they already know what it entails because they have generally spent at least 13 years observing teachers as they work. The role of a teacher can seem simplistic because as a student, you only see one piece of what teachers actually do day in and day out. This one-dimensional perspective can contribute to a person’s idea of what the role of teachers in schools is, as well as what the purpose of schooling should be. The idea of the purpose of schooling can also be seen as an individual’s philosophy of schooling.

Philosophy can be defined as the fundamental nature of knowledge, reality and existence. In the case of education, one’s philosophy is what one believes to be true about the essentials of education. When thinking about your philosophy of education, consider your beliefs about the roles of schools, teachers, learners, families, and communities. There are four philosophical perspectives currently used in educational settings: essentialism, perennialism, progressivism, and social reconstructionism/critical pedagogy. Unlike the more abstract philosophical perspectives of ontology and axiology, these four perspectives focus primarily on what should be taught and how it should be taught, i.e. the curriculum. These are explained below.

3.2 Four Key Educational Philosophies

Essentialism.

Essentialism adheres to a belief that a core set of essential skills must be taught to all students. Essentialists tend to privilege traditional academic disciplines that will develop prescribed skills and objectives in different content areas as well as develop a common culture. Typically, Essentialism argues for a back-to-basics approach on teaching intellectual and moral standards. Schools should prepare all students to be productive members of society. The Essentialist curriculum focuses on reading, writing, computing clearly and logically about objective facts concerning the real world. Schools should be sites of rigor where students learn to work hard and respect authority. Because of this stance, Essentialism tends to subscribe to tenets of Realism. Essentialist classrooms tend to be teacher-centered in instructional delivery with an emphasis on lecture and teacher demonstrations.

Perennialism:

Perennialism advocates for seeking, teaching, and learning universal truths that span across historical time periods. These truths, Perennialists argue, have everlasting importance in helping humans solve problems regardless of time and place. While Perennialism resembles essentialism at first glance, Perennialism focuses on the individual development of the student rather than emphasizing skills. Perennialism supports liberal arts curricula that helps produce well-rounded individuals with some knowledge across the arts and sciences. All students should take classes in English Language Arts, foreign languages, mathematics, natural sciences, fine arts, and philosophy. Like Essentialism, Perennialism may tend to favor teacher-centered instruction; however, Perennialists do utilize student-centered instructional activities like Socratic Seminar, which values and encourages students to think, rationalize, and develop their own ideas on topics.

Progressivism

Progressivism focuses its educational stance toward experiential learning with a focus on developing the whole child. Students learn by doing rather than being lectured to by teachers. Curriculum is usually integrated across contents instead of siloed into different disciplines. Progressivism’s stance is in stark contrast to both Essentialism and Perennialism in this manner. Progressivism follows a clear pragmatic ontology where the learner focuses on solving real-world problems through real experiences. Progressivist classrooms are student-centered where students will work in cooperative/collaborative groups to do project-based, expeditionary, problem-based, and/or service-learning activities. In progressivist classrooms, students have opportunities to follow their interests and have shared authority in planning and decision making with teachers.

3.3 A Response to Dominant Systems:

Social reconstructionism.

Social reconstructionism was founded as a response to the atrocities of World War II and the Holocaust to assuage human cruelty. Social reform in response to helping prepare students to make a better world through instilling liberatory values. Critical pedagogy emerged from the foundation of the early social reconstructionist movement.

Critical Lens – Liberatory Thinking

“Liberatory thinking is the re- imagining of one’s assumptions and beliefs about others and their capabilities by interrupting internal beliefs that undermine productive relationships and actions. Liberatory thinking goes beyond simply changing mindsets to creating concrete opportunities for others to experience liberation. The opportunities provides cover for and centers underrepresented and marginalized people. It pushes people to interrogate their own multiple identities in relation to others and to think about the consequences of our actions, especially for students of critical need. It explores how mindsets can impede or ignite progress in the classroom, school, and district.”

Chicago Public Schools

For more information in Liberatory Thinking, please refer to the Equity Framework from the Chicago Public Schools

Critical Pedagogy

Critical pedagogy is the application of critical theory to education. For critical pedagogues, teaching and learning is inherently a political act and they declare that knowledge and language are not neutral, nor can they be objective. Therefore, issues involving social, environmental, or economic justice cannot be separated from the curriculum. Critical pedagogy’s goal is to emancipate marginalized or oppressed groups by developing, according to Paulo Freire, conscientização, or critical consciousness in students.

Critical pedagogy de-centers the traditional classroom, which positions teachers at the center. The curriculum and classroom with a critical pedagogy stance is student-centered and focuses its content on social critique and political action.

3.4 Ways of Knowing

Pause and Ponder – Ways of Knowing

In addition to the historically neglected thinkers and the theories presented above, it is important for educators to consider that there are many ways of knowing and acquiring knowledge

How do you know something is true?

In the US school system, for instance, students begin the day when a bell or signal goes off at the same predetermined time every day. This scheduling system shapes students’ awareness of how days in their lives will most likely be structured. Consider an alternative: What would happen if the school day started every day when the sun passes a certain point across the horizon. What would students learn about the world? How would students’ way of knowing about time and responsibility be changed?

Critical Lens – Cultural Practices

Here are two news stories with examples of cultural practices that are not taught in mainstream schools because they have been steered away from in this imperialistic, colonizing culture. Nevertheless, they have been sustained by thinkers and teachers and continue to be sustained today.

Culturally informed childbirth practices: Navajo woman starts nonprofit to improve maternal health

Traditional care of the land: For tribes, ‘good fire’ a key to restoring nature and people

3.5 Educational Thinkers

The thinkers and perspectives in the preceding section of this text are considered foundational thinkers in mainstream formal education in the US, other thinkers from the same time period and throughout history are considered foundational contributors to education throughout the world. Some of this has to do with the notion of US colonialism, imperialism, exceptionalism (the belief that the United States is either distinctive, unique, or exemplary compared to other nations), and the legacy of the enslavement of Black Americans in the United States. Because of these legacies, very few people of color were accepted into the cannon of formal educational thinkers. As a result, the US system has been shaped by a very narrow sample of foundational theorists, and many educators who trained in the 20th and 21st centuries in the US had their perspectives formed under this narrow umbrella.

The following individuals and theories are presented so that you can broaden your perspective and better serve all students during your career in education.

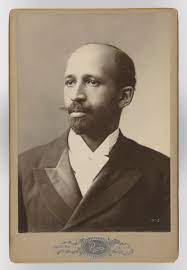

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois

Du Bois was an American sociologist, historian and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist. Du Bois completed his graduate work at the University of Berlin and Harvard University, where he was the first African American to earn a doctorate. He became a professor of history, sociology and economics at Atlanta University. Du Bois was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909.

In an effort to portray the genius and humanity of the Black race, Du Bois published The Souls of Black Folk (1903), a collection of 14 essays. The introduction of the book famously proclaimed that “the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line.” Each chapter begins with two epigraphs – one from a White poet, and one from a Black spiritualist – to demonstrate intellectual and cultural parity between Black and White cultures.

A major theme of The Souls of Black Folk is the double consciousness faced by African Americans: being both American and Black. This was a unique identity which, according to Du Bois, had been a handicap in the past, but could be a strength in the future: “Henceforth, the destiny of the race could be conceived as leading neither to assimilation nor separatism but to proud, enduring hyphenation.”

Double consciousness is the internal conflict experienced by subordinated or colonized groups in an oppressive society. Originally, double consciousness was specifically the psychological challenge African Americans experienced of “always looking at oneself through the eyes” of a racist white society and “measuring oneself by the means of a nation that looked back in contempt”. The term also referred to Du Bois’s experiences of reconciling his African heritage with an upbringing in a European-dominated society.

More recently, the concept of double consciousness has been expanded to other situations of social inequality, notably women living in patriarchal societies as well as LGBTQ2S+ people living in homophobic and transphobic societies.

The idea of double consciousness is important because it illuminates the experiences of Black people living in post-slavery America, and also because it sets a framework for understanding the position of oppressed people in an oppressive world. As a result, it became used to explain the dynamics of gender, colonialism, xenophobia and more alongside race. This theory laid a strong foundation for other critical theorists to expand upon.

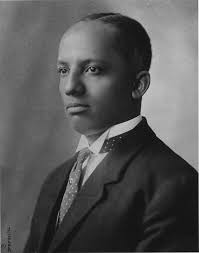

Carter Godwin Woodson

Woodson was an American educator, historian, author, and the founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. He achieved a graduate degree at the University of Chicago and in 1912 was the second African American, after W. E. B. Du Bois , to obtain a PhD from Harvard University . Woodson remains the only person whose parents were enslaved in the United States to obtain a PhD . He taught at two historically Black colleges: “ Howard University and West Virginia State University ”. Woodson believed that education and increasing social and professional contacts among Black and white people could reduce racism, and he promoted the organized study of African-American history partly for that purpose. He would later promote the first Negro History Week in Washington, D.C., in 1926, forerunner of Black History Month.

Woodson published The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861. Believing that history belonged to everybody, not just the historians, Woodson sought to engage Black civic leaders, high school teachers, clergy, women’s groups and fraternal associations in his project to improve the understanding of African-American history. He founded the Association for the Study of African American Life and History whose purpose he described as the “scientific study” of the “neglected aspects of Negro life and history” by training a new generation of Black people in historical research and methodology

hooks is a US based educational theorist and social activist. In Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom, she argues that a teacher’s use of control over students dulls the students’ enthusiasm and teaches obedience to authority, and keeps students from learning critical thinking. hook’s pedagogical practices exist as an interplay of anti-colonial, critical, and feminist pedagogies and are based on freedom. hooks also built a bridge between critical thinking and real-life situations, to enable educators to show students the everyday world instead of the stereotypical perspective of the world. hooks argues that teachers and students should engage in interrogations of cultural assumptions that are supported by oppression.

note: bell hooks intentionally does not capitalize her name, which follows her critical stance that language, even how we write one’s own name, is political and ideological.

Henry Giroux

Giroux is a foundational critical theorist in the US and Canada, best known for his pioneering work in critical pedagogy in K-12 and higher ed. His work advocates supporting students developing a consciousness of freedom and connecting knowledge to power, and the ability to take constructive action. His latest work examines the pitting of people against each other through the lens of class, race, and any other differences that don’t embrace white nationalism.

3.6 Latin American Thinkers

We will now analyze the impact of the pedagogical practice, as well as the educational thought, of different key educators in Latin America. These educators influenced a cultural change with ideas and concepts that modified the parameters of the educational system that was established in LatinAmerica.

Some of these educators have not been recognized in the educational system around the world. However, their work has been a catalyst in giving way to cultural and educational transformations in Latin America. The following educators stand out for their innovative tendencies who fought for an educational system to which all people had access.

When studying these Latin American educators, it should be noted that they generated a change that had a great impact on socio-cultural problems and that their success, or failure, depended on the government policies carried out in the corresponding countries.

Deeper Dive – Latin American Thinkers

You can watch the history of each Latin American thinkers in Spanish in the following video:

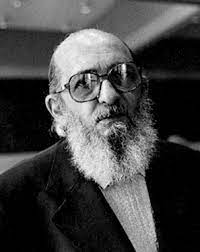

Paulo Reglus Neves Freire

Freire is a Brazilian philosopher and educator, was one of the most influential thinkers behind social reconstructionism. He criticized the banking model of education in his best known writing, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, which is generally considered one of the fundamental texts of the critical pedagogy movement. Banking models of education view students as empty vessels to be filled by the teacher’s expertise, like a teacher putting “coins” of information into the students’ “piggy banks.” Instead, Freire supported problem-posing models of education that recognized the prior knowledge everyone has and can share with others. Conservative critics of social reconstructionists suggest that they have abandoned intellectual pursuits in education, whereas social reconstructionists believe that the analyzing of moral decisions leads to being good citizens in a democracy.

The installment dedicated to Paulo Freire covers the different stages of the life of the Brazilian pedagogue and politician. The documentary shows his Christian roots and his first steps related to literacy and adult education in Brazil, especially the one carried out in Angicos. Then, it continues with Freire’s years in exile, which included a diverse tour of Chile, the US, Nicaragua, etc. and the publication, in 1970, of two of his most important works: Education as a practice for freedom and Pedagogy of the oppressed. At the same time, it is argued that these works strengthened a political idea that became the organizer of the movement of the oppressed in Latin America.

Pause and Ponder – Dominant Narrative

The work of Freire, Giroux, and hooks are included as necessary responses to the exclusionary and marginalizing nature of the dominant narrative of educational systems. Even today, although educators may study their work, the systems they’re employed with tend to perpetuate the inequalities and dynamics Freire, Giroux, hooks, and others address.

Gabriela Mistral

Mistral, pseudonym of Lucila Godoy Alcayaga, was a Chilean poet, diplomat and pedagogue. She received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1945 for her poetic work, she was the first Ibero-American woman and the second Latin American person to receive a Nobel Prize.

Her political-ideological profile is represented as a hybrid between her Catholic, but not conservative, beliefs and her liberal traits, although she is not strictly defined as liberal. Her words and poetry, which frequently gave life to various newspaper articles, generated multiple conflicts with the most conservative sectors of society. Mistral, however, continued on her way and affirmed her work in the rural and indigenous sectors. During her trip to Mexico, at the invitation of Vasconcelos, she fulfilled her full potential as a teacher, promoting a pedagogy based on the child, with Christian roots and that took into account the singularities of the rural and indigenous areas in which she worked. In 1945 she became the first woman to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature, something that made visible the impact of her teaching practice, intellectual and poetic practice.

Domingo Faustino Sarmiento

Sarmiento was an Argentine politician, writer, teacher, journalist, serviceman and statesman; governor of the province of San Juan between 1862 and 1864, president of the Argentine Nation between 1868 and 1874, national senator for his province between 1874 and 1879 and minister of the interior in 1879.

His controversial, anti-racist and unitary side is reaffirmed, and the fact that he belongs to a generation that understood writing as a political practice. He questioned what was the best educational system for all of the students in Latina America. He starts investigating the opposite approaches of education in Massachusetts and Prussia. He believed that the students had a better option to succeed and learn independently in a society under the Prussian system, which was centralized and under the management of the state. The educational system in Massachusetts, on the contrary, was decentralized and the society was the principal entity to promote education. Therefore, the habits of each state were instilled in the students. For example, a republican state will have a republican approach to education and he did not agree with this approach. Therefore, after his investigations he laid the programmatic foundations of a national educational system, in where it was centralized and Popular Education was provided to all of the children in Argentina.

Later on, his side as a statesman is taken up again with the contributions he made in the elaboration of the Law of Common Education of Buenos Aires (1875) and the sanction under his presidency of the National Law of Common Education (1884).

Jesualdo Sosa

Sosa, better known as Jesualdo, was a Uruguayan teacher, writer, pedagogue and journalist. His teaching led him to dedicate himself with greater purpose and knowledge on the activities, interests and needs of the child.

Starting from a critique of the traditional school and the capitalist system, Sosa combined there a proposal with Escolanovist overtones, which promoted the autonomy of children, their creativity, their expression, their work training, and was articulated with the activities of the community. That experience was collected in Vida de un maestro, a production that, despite the censorship attempts it suffered from dictatorial governments, was able to expand worldwide. After that publication, his life is described as a time of maturation, systematization and recognition, which gave him the chance to be called to collaborate in different parts of Latin America.

Simón Narciso de Jesús Carreño Rodríguez

de Jesús Carreño Rodríguez was a Venezuelan hero, educator, and politician. He was the tutor of Simón Bolívar and Andrés Bello. He contributed concepts and ideas including written works aimed at the process of freedom and American integration.

In the seventh installment, Simón Rodríguez is recognized as a great precursor of our American pedagogical thought, as a fighter for the emancipation of Latin America and for public education for all as a form of social progress. His philosophy favored the equality in education as he believed this was a right for all citizens. He highlights his conception of equality, which was not restrictive as he believed that equality started in educational practices. He sacrificed all his belongings and left everything for his ideals. In the miniseries,

José Vasconcelos Calderón

Vasconcelos Calderón was a Mexican lawyer, politician, writer, educator, public official and philosopher. He was part of the revolutionary movement led by Francisco Madero, which promoted the democratic transformation of a country that, at that time, was shaken by the dictatorships of Porfirio Díaz Mori. As a result of a political setup, Vasconcelos became Secretary of Education of the Federal Government (1921-1924). His management in this position is distinguished as short and intense, since there he carried out, with the support of Gabriela Mistral, his most recognized work, promoting high culture, rural literacy missions and muralism as ways of recovering Latin American roots. His work, The Cosmic Race, is considered a condensation of his position in favor of mestizaje, which is the biological and cultural encounter or its arrangement between different ethnic groups, in which they mix, giving birth to new species of families and new genotypes. This was a very controversial work as it was not aligned with the thinking of the people from this time.

José Carlos Mariátegui

Mariátegui, La Chira, was a Peruvian writer, journalist and political thinker, a prolific author despite his early death. He is also known in his country by the name of El Amauta. He was one of the main scholars of Socialism in Latin America.

“The revolution is not only the fight for bread, but also the conquest of beauty” is a representative phrase of José Carlos Mariátegui, which marks the beginning of the installment referring to the Peruvian writer, journalist and intellectual. At first, the documentary goes through what is considered his first school, recounting his initial steps in the writing of the newspaper La Razón, where he grew as a journalist and became involved in workers’ struggles and reformist ideals. Then it is analyzed how during his exile in Europe, Mariátegui was nurtured by Marxist ideas, the struggles of Italian workers and began to work on the notion of indigenism as a creative and revolutionary myth. During his return, it is stated that he strengthened his political proposal of autochthonous socialism, marked by a juxtaposition between Marxist theory, Latin Americanism and indigenism, with a strong emphasis also on gender equality and the depatriarchalizing of educational practices. These aspects are present in its most important editorial offering, Amauta. In 1928, he created the Peruvian Socialist Party and published Seven Interpretive Essays on Peruvian Reality, from which he criticized the liberal model of education (which placed the problem of indigenous people in education) and the lack of their recognition as subjects of law.

José Julián Martí Pérez

Martí Pérez was a writer and politician of Cuban origin. Democratic republican politician, thinker, journalist, philosopher and Cuban poet, creator of the Cuban Revolutionary Party and organizer of the War of 95 or Necessary War, named after the Cuban War of Independence. He suffered the vicissitudes of critical thought from a very young age, when he was imprisoned and exiled. Strongly involved in the struggles against Spanish colonization and US interference in the Caribbean, he claimed Bolivarian principles. His political and educational thought is described through four topics: the decolonization of Latin American knowledge, the formation of good people and the role of love in pedagogy, the special place given to creative work and the recovery of Latin American identity. In 1892, a time of exile, he founded the Cuban Revolutionary Party as a tool for the independence of the island and finally died on the battlefield years later.

Jorge J. E. Gracia

Gracia was born in Cuba in 1942 and was a Cuban refugee in the USA. He studied at both Universidad de La Habana and Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes San Alejandro in Havana before moving to the U.S., where he earned a degree in philosophy from Wheaton College in 1965. He went on to receive a master’s degree in philosophy from University of Chicago in 1966, a licentiate in medieval studies from Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies in 1970 and his doctorate in medieval philosophy from University of Toronto in 1971.

Gracia’s areas of research included metaphysics, ethnic and racial issues, philosophy of religion, and medieval and Latin American philosophy. These topics led him to author over 20 books and edit more than two dozen volumes of works by others. One of his most notable contributions was his 1984 edited anthology on Latin American philosophy, “Philosophical Analysis in Latin America,” which was the first work of its kind published in English by a philosopher.

Beyond his vast collection of writings, he was also a leader for many important organizations. He was the founding chair for the American Philosophical Association’s Committee for Hispanics in Philosophy and sat as president of the Society for Medieval and Renaissance Philosophy, Society for Iberian and Latin American Thought, American Catholic Philosophical Association and the Metaphysical Society of America.

Gracia worked for the State University of New York at Buffalo from 1971 until he retired in January 2020 as SUNY Distinguished Professor and Samuel P. Capen Chair in the departments of philosophy and comparative literature.

Héctor-Neri Castañeda

Castañeda was a Guatemalan American philosopher who emigrated to the U.S. in 1948 as a refugee. He attended the University of Minnesota to earn his bachelor’s, master’s and PhD degrees.

After graduating with his PhD, Castañeda studied at Oxford University for a year before returning to the U.S. to work at Duke University for a short period of time. He went on to work at Wayne State University, where he founded the philosophical journal Noûs , which is still in production to this day.

Eventually, he moved to Indiana University in 1969 and became the Mahlon Powell Professor of philosophy as well as that university’s first dean of Latino affairs.

Castañeda is most notable for developing the guise theory , which applies to the analysis of thought, language and the structure of the world through abstract objects. He is also credited with the discovery of the concept of the quasi-indexical or quasi-indicator. This is a linguistic expression in which a person referencing another can shift from context to context, much like in the way ‘you’ can refer to a specific person in one context and another person in a different context.

In addition to his research, he was awarded a fellowship from the Guggenheim Foundation and received grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the National Science Foundation. He was also given the Presidential Medal of Honor by the government of Guatemala in 1991, among many other accomplishments.

Activities – Personal Philosophy of Education

In order to start building your own personal philosophy of education, it’s important to be able to articulate how you will incorporate diverse perspectives and ways of knowing into your teaching.

Instructions:

- Select a mainstream-culture based single story about education and analyze it. Examine how an ideology or stereotype is perpetuated through it

- Explore some or all of the story’s origins functions impact on education

- Then examine the alternative stories: those told by the survivors of the single story

- Propose ways to change the story both in your teaching and in the educational system in general

Like learning, teaching is always developing; it is never realized once and for all. Our public schools have always served as sites of moral, economic, political, religious and social conflict and assimilation into a narrowly defined standard image of what it means to be an American. According to Britzman (as quoted by Kelle, 1996), “the context of teaching is political, it is an ideological context that privileges the interests, values, and practices necessary to maintain the status quo.” Teaching is by no means “innocent of ideology,” she declares. Rather, the context of education tends to preserve “the institutional values of compliance to authority, social conformity, efficiency, standardization, competition, and the objectification of knowledge” (p. 66-67).

It should be no surprise then that contemporary debates over public education continue to reflect our deepest ideological differences. As Tyack and Cuban (1995) have noted in their historical study of school reform, the nation’s perception toward schooling often “shift[s]… from panacea to scapegoat” (p. 14). We would go a long way in solving academic achievement and closing educational gaps by addressing the broader structural issues that institutionalize and perpetuate poverty and inequality.

AFT – American Federation of Teachers – A Union of Professionals. (n.d.). American Federation of Teachers. https://www.aft.org/

April 14, 1947: Mendez v. Westminster Court Ruling – Zinn Education Project. (2023, May 25). Zinn Education Project. https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/mendez-v-westminster/

ASU Local-Los Angeles welcomes its 3rd cohort of students. (2021, September 24). ASU News. https://news.asu.edu/20210924-latin-american-philosophers-you-should-know-about

BBC News. (2021, June 24). Canada: 751 unmarked graves found at residential school. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-57592243

Bennett, Jr., Lerone (2005). “Carter G. Woodson, Father of Black History”. United States Department of State. Archived from the original on April 1, 2011. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

“Carter G. Woodson: Winona, WV – New River Gorge National Park and Preserve (U.S. National Park Service)”. www.nps.gov. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

Daryl Michael Scott, “The History of Black History Month” Archived July 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, on ASALH website.

Del Maestro Cmf, W. (2023). Maestros de América Latina, una serie que todo educador y estudiante de educación tiene que ver. Web Del Maestro CMF. https://webdelmaestrocmf.com/portal/maestros-de-america-latina-una-serie-que-todo-educador-y-estudiante-de-educacion-tiene-que-ver/

Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt (1997). The correspondence of W. E. B. Du Bois, Volume 3. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 282. ISBN 1-55849-105-8. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

Du Bois, W. E. B. The Souls of Black Folk. New York, Avenel, NJ: Gramercy Books; 1994

Evans, N. E. C. (2021, July 11). A Federal Probe Into Indian Boarding School Gravesites Seeks To Bring Healing. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2021/07/11/1013772743/indian-boarding-school-gravesites-federal-investigation

Hine, Darlene Clark (1986). “Carter G. Woodson, White Philanthropy and Negro Historiography”. The History Teacher. JSTOR. 19 (3): 407. doi : 10.2307/493381 . ISSN 0018-2745 . JSTOR 493381 .

Hooks, Bell (1994). Teaching to transgress: education as the practice of freedom. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415908078 . OCLC 30668295 .

Jan. 5, 1931: Lemon Grove incident – Zinn Education Project. (2023, January 6). Zinn Education Project. https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/lemon-grove-incident/

Kahn, Jonathon S., Divine Discontent: The Religious Imagination of W. E. B. Du Bois, Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530789-4.

Lewis, David Levering (1993). W. E. B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race 1868–1919. New York City: Henry Holt and Co. p. 11. ISBN 9781466841512.

Liberatory thinking . (n.d.). https://www.cps.edu/sites/equity/equity-framework/equity-lens/liberatory-thinking/

Love, B. (2019). We Want To Do More Than Survive: Abolitionist Teaching and the Pursuit of Educational Freedom. Beacon.

National Education Association | NEA. (n.d.). https://www.nea.org/

Paulo Freire | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (n.d.). https://iep.utm.edu/freire/

PBS Online: Only A Teacher: Schoolhouse Pioneers. (n.d.). https://www.pbs.org/onlyateacher/john.html

Perez, D. (2022b, January 3). Social foundations of K-12 education. Pressbooks. https://kstatelibraries.pressbooks.pub/dellaperezproject/

Perez, D. (2022a, January 3). Chapter 4: Foundational Philosophies of Education. Pressbooks. https://kstatelibraries.pressbooks.pub/dellaperezproject/chapter/chapter-3-foundational-philosophies-of-education/

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (A. R. Luria, M. Lopez-Morillas & M. Cole [with J. V. Wertsch], Trans.) Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. (Original work [ca. 1930-1934)

Wamba, Philippe (1999). Kinship. New York, New York: Penguin Group. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-525-94387-7.

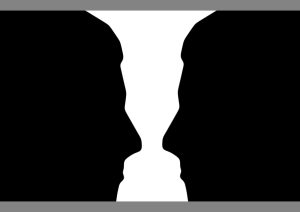

3.1 – “Two silhouette profile or a white vase.” by Wikimedia Commons is in the Public Domain, CC0

3.2 – “W.E.B. Du Bois” by James E. Purdy, Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

3.3 – “Carter Godwin Woodson” by Flickr is licensed under CC BY 4.0

3.4 – “bell hooks” by Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

3.5 – “Henry Giroux” by Flickr is licensed under CC BY 4.0

3.6 – “Paulo Freire” by Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

3.7 – “Gabriela Mistral sonriendo” by Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

3.8 – “Sarmiento” by Get Archive is in the Public Domain, CC0

3.9 – “Simón Rodriguez” by Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY 4.0

3.10 – “Jose Vasconsuelos” by Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY 4.0

3.11 – “Jose Carlos Mariategui” by Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY 4.0

3.12 – “Jose Marti” by Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY 4.0

3.1 – Essentialism in Education (Essentialist Philosophy of Education, Essentialist Theory of Education)s” by PHILO-notes, YouTube is licensed under CC BY 4.0

3.2 -“Perennialism: Overview & Practical Teaching Examples” by Shayla Czuchran, YouTube is licensed under CC BY 4.0

3.3 – “Progressivism: Overview & Practical Teaching Examples” by Teea Shook, YouTube is licensed under CC BY 4.0

3.4 – “Social Reconstruction” by Sarah Barlowe, YouTube is licensed under CC BY 4.0

3.5 – “Paulo Freire’s Critical Pedagogy” by Dr. Yu-Ling Lee, YouTube is licensed under CC BY 4.0

3.6 – “The Earth Talks: Indigenous Ways of Knowing – with Pat McCabe” by Dartington Trust, YouTube is licensed under CC BY 4.0

3.7 – “Presentación de la serie Maestros de América Latina” by UNIPE Universidad Pedagógica Nacional , YouTube is licensed under CC BY 4.0

3.8 – “The danger of a single story “ by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie , YouTube is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Foundations of Education Copyright © 2023 by Lisa AbuAssaly George; Dr. Kanoe Bunney; Ceci De Valdenebro; and Tanya Mead is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Philosophy of Education

All human societies, past and present, have had a vested interest in education; and some wits have claimed that teaching (at its best an educational activity) is the second oldest profession. While not all societies channel sufficient resources into support for educational activities and institutions, all at the very least acknowledge their centrality—and for good reasons. For one thing, it is obvious that children are born illiterate and innumerate, and ignorant of the norms and cultural achievements of the community or society into which they have been thrust; but with the help of professional teachers and the dedicated amateurs in their families and immediate environs (and with the aid, too, of educational resources made available through the media and nowadays the internet), within a few years they can read, write, calculate, and act (at least often) in culturally-appropriate ways. Some learn these skills with more facility than others, and so education also serves as a social-sorting mechanism and undoubtedly has enormous impact on the economic fate of the individual. Put more abstractly, at its best education equips individuals with the skills and substantive knowledge that allows them to define and to pursue their own goals, and also allows them to participate in the life of their community as full-fledged, autonomous citizens.

But this is to cast matters in very individualistic terms, and it is fruitful also to take a societal perspective, where the picture changes somewhat. It emerges that in pluralistic societies such as the Western democracies there are some groups that do not wholeheartedly support the development of autonomous individuals, for such folk can weaken a group from within by thinking for themselves and challenging communal norms and beliefs; from the point of view of groups whose survival is thus threatened, formal, state-provided education is not necessarily a good thing. But in other ways even these groups depend for their continuing survival on educational processes, as do the larger societies and nation-states of which they are part; for as John Dewey put it in the opening chapter of his classic work Democracy and Education (1916), in its broadest sense education is the means of the “social continuity of life” (Dewey, 1916, 3). Dewey pointed out that the “primary ineluctable facts of the birth and death of each one of the constituent members in a social group” make education a necessity, for despite this biological inevitability “the life of the group goes on” (Dewey, 3). The great social importance of education is underscored, too, by the fact that when a society is shaken by a crisis, this often is taken as a sign of educational breakdown; education, and educators, become scapegoats.

It is not surprising that such an important social domain has attracted the attention of philosophers for thousands of years, especially as there are complex issues aplenty that have great philosophical interest. Even a cursory reading of these opening paragraphs reveals that they touch on, in nascent form, some but by no means all of the issues that have spawned vigorous debate down the ages; restated more explicitly in terms familiar to philosophers of education, the issues the discussion above flitted over were: education as transmission of knowledge versus education as the fostering of inquiry and reasoning skills that are conducive to the development of autonomy (which, roughly, is the tension between education as conservative and education as progressive, and also is closely related to differing views about human “perfectibility”—issues that historically have been raised in the debate over the aims of education); the question of what this knowledge, and what these skills, ought to be—part of the domain of philosophy of the curriculum; the questions of how learning is possible, and what is it to have learned something—two sets of issues that relate to the question of the capacities and potentialities that are present at birth, and also to the process (and stages) of human development and to what degree this process is flexible and hence can be influenced or manipulated; the tension between liberal education and vocational education, and the overlapping issue of which should be given priority—education for personal development or education for citizenship (and the issue of whether or not this is a false dichotomy); the differences (if any) between education and enculturation; the distinction between educating versus teaching versus training versus indoctrination; the relation between education and maintenance of the class structure of society, and the issue of whether different classes or cultural groups can—justly—be given educational programs that differ in content or in aims; the issue of whether the rights of children, parents, and socio-cultural or ethnic groups, conflict—and if they do, the question of whose rights should be dominant; the question as to whether or not all children have a right to state-provided education, and if so, should this education respect the beliefs and customs of all groups and how on earth would this be accomplished; and a set of complex issues about the relation between education and social reform, centering upon whether education is essentially conservative, or whether it can be an (or, the ) agent of social change.

It is impressive that most of the philosophically-interesting issues touched upon above, plus additional ones not alluded to here, were addressed in one of the early masterpieces of the Western intellectual tradition—Plato's Republic . A.N. Whitehead somewhere remarked that the history of Western philosophy is nothing but a series of footnotes to Plato, and if the Meno and the Laws are added to the Republic , the same is true of the history of educational thought and of philosophy of education in particular. At various points throughout this essay the discussion shall return to Plato, and at the end there shall be a brief discussion of the two other great figures in the field—Rousseau and Dewey. But the account of the field needs to start with some features of it that are apt to cause puzzlement, or that make describing its topography difficult. These include, but are not limited to, the interactions between philosophy of education and its parent discipline.

1.1 The open nature of philosophy and philosophy of education

1.2 the different bodies of work traditionally included in the field, 1.3 paradigm wars the diversity of, and clashes between, philosophical approaches, 2.1 the early work: c.d. hardie, 2.2 the dominant years: language, and clarification of key concepts, 2.3 countervailing forces, 2.4 a new guise contemporary social, political and moral philosophy, 3.1 philosophical disputes concerning empirical education research, 3.2 the content of the curriculum, and the aims and functions of schooling, 3.3 rousseau, dewey, and the progressive movement, 4. concluding remarks, bibliography, other internet resources, related entries, 1. problems in delineating the field.