- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

The Sled Dog Relay That Inspired the Iditarod

By: Christopher Klein

Updated: May 16, 2023 | Original: March 10, 2014

The children of Nome were dying in January 1925. Infected with diphtheria, they wheezed and gasped for air, and every day brought a new case of the lethal respiratory disease. Nome’s lone physician, Dr. Curtis Welch, feared an epidemic that could put the entire village of 1,400 at risk. He ordered a quarantine but knew that only an antitoxin serum could ward off the fast-spreading disease.

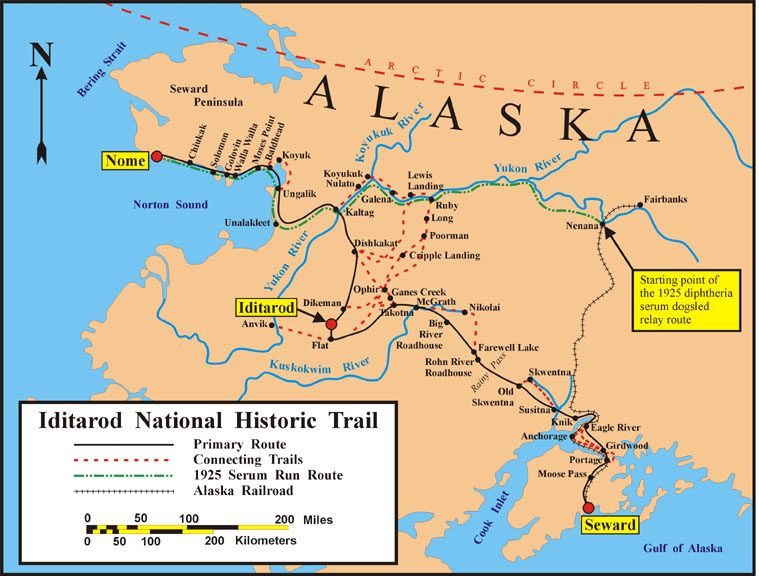

The nearest batch of the life-saving medicine, however, rested more than 1,000 miles away in Anchorage. Nome’s ice-choked harbor made sea transport impossible, and open-cockpit airplanes could not fly in Alaska’s subzero temperatures. With the nearest train station nearly 700 miles away in Nenana, canine power offered Nome its best hope for a speedy delivery.

Sled dogs regularly beat Alaska’s snowy trails to deliver mail, and the territory’s governor, Scott C. Bone, recruited the best drivers and dog teams to stage a round-the-clock relay to transport the serum from Nenana to Nome. On the night of January 27, 1925, a train whistle pierced Nenana’s stillness as it arrived with the precious cargo—a 20-pound package of serum wrapped in protective fur. Musher “Wild Bill” Shannon tied the parcel to his sled. As he gave the signal, the paws of Shannon’s nine malamutes pounded the snow-packed trail on the first steps of a 674-mile “Great Race of Mercy” through rugged wilderness, across frozen waterways and over treeless tundra.

Even by Alaskan standards, this winter night packed extra bite, with temperatures plummeting to 60 degrees below zero Fahrenheit. Although every second was precious as the number of confirmed cases in Nome mounted, Shannon knew he needed to control his speed. If his dogs ran too fast and breathed too deeply in such frigid conditions, they could frost their lungs and die of exposure. Although Shannon ran next to the sled to raise his own body temperature, he still developed hypothermia and frostbite on the 52-mile leg to Tolovana before handing off the serum to the second dog team.

With moonlight and even the northern lights illuminating the dark Alaskan winter days, the relay raced at an average speed of six miles per hour. While each leg averaged 30 miles, the country’s most famous musher, Norwegian-born Leonhard Seppala, departed Shaktoolik on January 31 on an epic 91-mile leg. Having already rushed 170 miles from Nome to intercept the relay, Seppala decided on a risky shortcut over the frozen Norton Sound in the teeth of a gale that dropped wind chills to 85 degrees below zero. Seppala’s lead dog, 12-year-old Siberian Husky Togo, had logged tens of thousands of miles, but none as important as these. Togo and his 19 fellow dogs struggled for traction on Norton Sound’s glassy skin, and the fierce winds threatened to break apart the ice and send the team adrift to sea. The team made it safely to the coastline only hours before the ice cracked. Gusts continued to batter the team as it hugged the coastline before meeting the next musher, Charlie Olson, who after 25 miles handed off the serum to Gunnar Kaasen for the scheduled second-to-last leg of the relay.

As Kaasen set off into a blizzard, the pelting snow grew so fierce that his squinting eyes could not see any of his team, let alone his trusted lead dog, Balto. On loan from Seppala’s kennel, Balto relied on scent, rather than sight, to lead the 13-dog team over the beaten trail as ice began to crust the long hairs of his brown coat. Suddenly, a massive gust upwards of 80 miles per hour flipped the sled and launched the antidote into a snow bank. Panic coursed through Kaasen’s frostbitten body as he tore off his mitts and rummaged through the snow with his numb hands before locating the serum.

Kaasen arrived in Port Safety in the early morning hours of February 2, but when the next team was not ready to leave, the driver decided to forge on to Nome himself. After covering 53 miles, Balto was the first sign of Nome’s salvation as the sled dogs yipped and yapped down Front Street at 5:30 A.M. to deliver the valuable package to Dr. Welch.

The relay had taken five-and-a-half days, cutting the previous speed record nearly in half. Four dogs died from exposure, giving their lives so that others could live. Three weeks after injecting the residents of Nome, Dr. Crosby lifted the quarantine.

Although more than 150 dogs and 20 drivers participated in the relay, it was the canine that led the final miles that became a media superstar. Within weeks, Balto was inked to a Hollywood contract to star in a 30-minute film, “Balto’s Race to Nome.” After a nine-month vaudeville tour, Balto was present in December 1925 as a bronze statue of his likeness was unveiled in New York’s Central Park.

Seppala and his Siberians also toured the country and even appeared in an advertising campaign for Lucky Strike cigarettes, but the famous driver resented the glory lavished on Balto at the expense of Togo, who had guided the relay’s longest and most arduous stretch. “It was almost more than I could bear when the ‘newspaper dog’ Balto received a statue for his ‘glorious achievements,’” Seppala remarked.

The serum run was Togo’s last long-distance feat. He died in 1929, and his preserved body is on view at the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race Headquarters in Wasilla, Alaska. After the limelight faded, Balto lived out his final days at the Cleveland Zoo, and his body is on display at the Cleveland Natural History Museum. Since 1973, the memory of the serum run has lived on in the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, which is held each March and is run on some of the same trails beaten by Balto, Togo and dozens of other sled dogs in a furious race against time nearly a century ago.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Breaking Trail at the Iditarod, Alaska’s 1,000-Mile Dog Sled Race

Each year, Alaska hosts a 1,000-mile-long dog sled race called the Iditarod. Its founder, Joe Redington, Sr., deserves credit for preserving the sport.

The fabled Spirit of the North has compelled countless souls to abandon their comforts of civilized life in pursuit of a dream romanticized by the poems of Robert Service and the novels of Jack London. Some, who grow weary with the work of it or simply unable to afford it, turn and retreat back Outside (to the lower 48). Others, like Joe Redington, Sr., find in the slow and quiet rhythms of the North a melody harmonious with their own. They find country vast enough to let their boldest ideas breathe and grow. No other place could have fostered the creation of the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, and it’s safe to say no other place could have sustained it for more than forty-four years.

Much has changed about the race, but on trail, dog teams and their drivers move along exactly as they have for centuries. Redington’s goal in establishing the race was to defend one of the great northern traditions against the tireless march of modernity. He moved to Alaska after the second World War, homesteading in Knik, north of Anchorage. His accomplishments with dog teams are various and superlative, including: summiting North America’s highest peak, the 20,310 foot Denali , with dogs; recovering plane wreckage from remote sites for the Army; and winning a staggering number of races along the way. The Redingtons kept nearly 200 dogs, some of them for racing, others for freight-hauling. The scope of responsibility such a number entails demands a deep love for and understanding of canines. That love for dogs lit a fire in Joe Redington, Sr.

In the 1960s, the remote villages of Alaska experienced a sudden and sweeping change. It used to be that behind every house was a dog yard with a team of Alaskan huskies trained up and ready for adventure. For centuries, dog teams provided Alaskans with every conceivable means of survival: subsistence, travel, trail breaking, freight hauling, postal runs, deliveries of medicine—the list goes on and on. In fact, the last postal run by a dog team took place in 1963 .

The advent of the snow machine suddenly provided interior Alaskans with a means of achieving all of those functions with considerably less daily effort. A dog team requires at least twice daily feedings, a clean dog yard, water in the summer, the acquisition of fish for food, constant veterinary care, love, and an enduring bond with a musher. A snow machine requires gas.

Redington saw a tradition that he deeply loved and respected disappearing from the very culture that wrought that reverence in the first place. He knew that, without action, the sport of dog mushing could become a distant cultural memory; without the continued experience of distance mushing, those stories so central and unique to Alaskan history could not endure .

Redington’s familiarity with the rich history of dog mushing in Alaska and with his contemporaries in the dog-mushing community put him in a unique position to do something to counterbalance the threat to traditional mushing that he was seeing everywhere. He and fellow mushing enthusiast Dorothy Page were part of the Aurora Dog Mushers Association, which put on an Alaska Centennial race in 1967, employing a portion of the Iditarod Trail.

Joe and his wife Vi campaigned for years to establish the Iditarod Trail on the National Register of Historic Places. As both a musher and a bush pilot, he familiarized himself with every bend of the trail. He recognized that along its sinewy course—winding serpentine through the wilderness of the Alaska Range and the Farewell flats, northward to the coastal trail to Nome—there existed a tremendous opportunity to shed light on the romantic spirit of the sled dog and to preserve an integral part of Alaska’s history.

The inaugural Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race required a Herculean amount of work, much of it performed on blind faith. Redington established contacts with local businesses, fundraised, and applied for loans to raise the prize money. He recognized that if they were to draw mushers from around the world, they needed to entice the crowd with a hefty purse.

The initial rules for the Iditarod were scrawled on a bar napkin, based on Nome’s All Alaska Sweepstakes race, a worldwide phenomenon in the early part of the century that made household names out of revered Alaskan dog men like Leonhard Seppala and Scotty Allan. Redington contacted the Nome Kennel Club, assuring assistance from both ends of the trail. The Army Corps of Engineers pitched in, conveniently conducting an arctic winter exercise right along the Iditarod Trail, commencing curiously just days ahead of the race’s official start. The governor of Alaska established dog mushing as the state sport in advance of the race. Somehow, piece by piece, Redington’s dream of a 1,000 mile sled dog race was becoming a reality.

The only problem was that no one had ever completed a thousand-mile race. Expectations and reactions varied wildly, from enthusiastic support to acerbic naysaying. None of the mushers knew quite what to anticipate. Nonetheless, thirty-four teams showed up for the race, unloading dog trucks and sorting through mountains of gear in Anchorage parking lots, ahead of the starting gun. Race sleds as we know them didn’t exist; there were either sprint sleds (made to be light and fast) or freight sleds (longer toboggan-style sleds made to haul hundreds of pounds), but nothing tailor-made to a race that had never been run. Today’s modifications—Kevlar wrapping, tail draggers, aluminum frames, custom sled bags, and runner plastics—were nowhere to be seen. Instead, babiche-woven birch sleds were jam-packed with enough gear to sustain a musher and his dogs for the foreseeable future, weighing more than four hundred pounds. Axes, Blazo cans, sleeping bags, cookers, scoops, snowshoes, extra parkas, could anticipate needing were stuffed into the heavy sleds.

When the mushers first started down the trail, the full sum of the prize money had not yet been secured. Redington did not race in the first Iditarod, but opted to spearhead the logistics for a smooth race. In the first year, temperatures plummeted as low as -130°F with wind chill. The mushers camped together at night, trading stories over bonfires and tin cups of coffee. Teams took turns breaking trail after fresh snow fell.

Mushers had come from all over the state of Alaska—from Teller, Nome, Red Dog, Nenana, Seward, and all points in between. It was a unifying experience for the sport that provided insight into the motivations shared by the mushing community . Twenty days, forty minutes, and forty-one seconds after the race began, Dick Wilmarth and the famous lead dog Hotfoot mushed down Front Street in Nome to much adulation, garnering a purse of $12,000 for winning the first Iditarod.

Today’s victors arrive in Nome considerably faster; until this year’s race, which broke the record, the fastest time was eight days, eleven hours, twenty minutes, and sixteen seconds, held by four-time champion Dallas Seavey (whose grandfather and father preceded him in running the race). The first woman to win—Libby Riddles—did so in 1984, prompting the immediate proliferation of t-shirts stating “Alaska: where men are men and women win the Iditarod.” The race has seen one five-time champion (Rick Swenson) and a handful of four-time champs (Jeff King, Dallas Seavey, Martin Buser, Doug Swingley, and Susan Butcher). The trail is now established, kept open, and groomed by an army of volunteers. Sponsorships and financial support pour in for the race: the present champion is awarded $75,000 and a new Dodge truck.

What started as a dream of bringing the spirit of the sled dog back to the villages, shining an international light on the deep and abiding bond between a musher and his or her dog team, has ballooned into a world-renowned event. Along with the Yukon Quest 1,000 Mile International Sled Dog Race, run each February, the Iditarod is regarded as the premier event in dog mushing. Since 1990, more than 70 entrants have competed in the race every year. Meanwhile, hundreds of volunteers assist with logistics, communications, veterinary care, officiating, public relations, dog yard maintenance, and countless other tasks to make the race run smoothly.

Yet even as the race finds more renown, better PR, larger sponsorships, and a broadening audience, one thing has not changed: Out there, in the middle of the Alaskan wilderness, men and women still challenge themselves and their dogs to one of the ultimate tests of the North, navigating a forbidding expanse of land stretching 1,000 miles during the dead of winter. In the end, most teams don’t run for a shot at winning; they run for the rich, ineffable beauty of being on trail with their dogs and fellow mushers.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

More Stories

- The Alpaca Racket

- NASA’s Search for Life on Mars

Beware the Volcanoes of Alaska (and Elsewhere)

Saffron: The Story of the World’s Most Expensive Spice

Recent posts.

- Watching an Eclipse from Prison

- Going “Black to the Future”

- A Garden of Verses

Support JSTOR Daily

The Iditarod

A History and Overview of "The Last Great Race"

- Physical Geography

- Political Geography

- Country Information

- Key Figures & Milestones

- Urban Geography

- M.A., Geography, California State University - East Bay

- B.A., English and Geography, California State University - Sacramento

Each year in March, men, women, and dogs from around the world converge on the state of Alaska to take part in what has become known as the "Last Great Race" on the planet. This race is, of course, the Iditarod and though it doesn't have a long official history as a sporting event, dog sledding does have a long history in Alaska . Today the race has become a popular event for many people throughout the world.

Iditarod History

The Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race officially started in 1973, but the trail itself and the use of dog teams as a mode of transportation has a long and storied past. In the 1920s for example, newly arrived settlers looking for gold used dog teams in the winter to travel along the historic Iditarod Trail and into the gold fields.

In 1925, the same Iditarod Trail was used to move medicine from Nenana to Nome after an outbreak of diphtheria threatened the lives of nearly everyone in the small, remote Alaskan town. The journey was nearly 700 miles (1,127 km) through incredibly harsh terrain but showed how reliable and strong dog teams were. Dogs were also used to deliver mail and carry other supplies to the many isolated areas of Alaska during this time and many years later.

Throughout the years, however, technological advances led to the replacement of sled dog teams by airplanes in some cases and finally, snowmobiles. In an effort to recognize the long history and tradition of dog sledding in Alaska, Dorothy G. Page, chairman of the Wasilla-Knik Centennial helped set up a short race on the Iditarod Trail in 1967 with musher Joe Redington, Sr. to celebrate Alaska's Centennial Year. The success of that race led to another one in 1969 and the development of the longer Iditarod that is famous today.

The original goal of the race was for it to end in Iditarod, an Alaskan ghost town, but after the United States Army reopened that area for its own use, it was decided that the race would go all the way to Nome, making the final race approximately 1,000 miles (1,610 km) long.

How the Race Works Today

Since 1983, the race has ceremonially started from downtown Anchorage on the first Saturday in March. Starting at 10 a.m. Alaska time, teams leave in two-minute intervals and ride for a short distance. The dogs are then taken home for the rest of the day to prepare for the actual race. After a night's rest, the teams then leave for their official start from Wasilla, about 40 miles (65 km) north of Anchorage the next day.

Today, the route of the race follows two trails. In odd years the southern one is used and in even years they run on the northern one. Both, however, have the same starting point and diverge approximately 444 miles (715 km) from there. They join each other again about 441 miles (710 km) from Nome, giving them the same ending point as well. The development of two trails was done in order to reduce the impact that the race and its fans have on the towns along its length.

The mushers (dog sled drivers) have 26 checkpoints on the northern route and 27 on the southern. These are areas where they can stop to rest both themselves and their dogs, eat, sometimes communicate with family, and get the health of their dogs checked, which is the main priority. The only mandatory rest time however usually consists of one 24-hour stop and two eight hour stops during the nine- to twelve-day race.

When the race is over, the different teams split a pot that is now approximately $875,000. Whoever finishes first is awarded the most and each successive team to come in after that receives a little less. Those finishing after 31st place, however, get about $1,049 each.

Originally, sled dogs were Alaskan Malamutes, but over the years, the dogs have been crossbred for speed and endurance in the harsh climate, the length of the races they participate in and the other work they are trained to do. These dogs are usually called Alaskan Huskies, not to be confused with Siberian Huskies, and are what most mushers prefer.

Each dog team is made up of twelve to sixteen dogs and the smartest and fastest dogs are picked to be the lead dogs, running in the front of the pack. Those who are capable of moving the team around curves are the swing dogs and they run behind the lead dogs. The largest and strongest dogs then run in the back, closest to the sled and are called the wheel dogs.

Before embarking on the Iditarod trail, mushers train their dogs in late summer and fall using wheeled carts and all-terrain vehicles when there is no snow. The training is then the most intense between November and March.

Once they are on the trail, mushers put the dogs on a strict diet and keep a veterinary diary to monitor their health. If needed, there are also veterinarians at the checkpoints and "dog-drop" sites where sick or injured dogs can be transported for medical care.

Most of the teams also go through a large amount of gear to protect the dogs' health and they usually spend anywhere from $10,000-80,000 per year on gear such as booties, food, and veterinary care during training and the race itself.

Despite these high costs along with the hazards of the race such as harsh weather and terrain, stress, and sometimes loneliness on the trail, mushers and their dogs still enjoy participating in the Iditarod and fans from around the world continue to tune in or actually visit portions of the trail in large numbers to partake in the action and drama that is all part of "The Last Great Race."

- Iditarod Printables for Students

- How Fast Can Greyhounds Run?

- The Sociology of Race and Ethnicity

- History of Women Running for President of the United States

- Physical Education for Homeschool Kids

- Than vs. Then: How to Choose the Right Word

- An Overview of the Last Global Glaciation

- History of the Pekingese Dog

- History of the 1924 Olympics in Paris

- Medical Geography

- Jesse Owens: 4 Time Olympic Gold Medalist

- Celebrating Cultural Heritage Months

- Laika, the First Animal in Outer Space

- Introduction to Sociology

- Jackie Robinson

- History of the Artificial Heart

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

current events

Lesson of the Day: ‘2 Days, 10 Dogs, 150 Miles in the Wilderness: This Is the Iditarod for Teens’

In this lesson, students will learn about the Junior Iditarod Sled Dog Race and then explore the importance of physical tests and challenges in their own lives.

By Jeremy Engle

Students in U.S. high schools can get free digital access to The New York Times until Sept. 1, 2021.

Lesson Overview

Featured Article: “ 2 Days, 10 Dogs, 150 Miles in the Wilderness: This Is the Iditarod for Teens ” by Marlena Sloss

The Junior Iditarod, the longest race in Alaska for competitors under 18, is a chance for young mushers to prove their skills — leading a team of 10 sled dogs on a two-day race of nearly 150 miles through the wilderness. The winner receives a new dog sled, a beaver-fur hat and musher mittens along with a $6,000 scholarship. But for these teenage competitors, the prize is much bigger: a life-changing journey.

In this lesson, you will learn about the Iditarod race and its history, skills and challenges. In a Going Further activity, you will explore and write about journeys in your own life.

When have you faced a difficult journey, competition or challenge? Have you ever heard of the annual Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race? Do you think you could survive a two-day trek in the wilderness with a team of dogs? Would you ever want to?

Before reading the article, watch the three-minute video below from Alaska Public Media on the 2015 Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race. Then respond to these prompts:

What is one important thing you learned about the Iditarod competition?

What questions do you have about the race and its competitors?

What kinds of skills and preparation do you think are needed to compete in the Iditarod? What do you imagine would be the hardest part for you if you were to participate in it?

The video chronicles the roughly 1,000-mile adult Iditarod. The junior version is 150 miles. What do you imagine might be the additional challenges a teenager would face in trying to complete the race?

Questions for Writing and Discussion

Read the featured article , then answer the following questions:

1. Look at the photographs and their captions throughout the article:

What do you notice? What can you learn about the Junior Iditarod race, the teenage competitors and their relationship with their teams of sled dogs through these images?

What do you wonder? What questions do you have about the sport or the junior competitors?

Which picture stands out to you most and why?

Taken together, what story do these images tell?

2. What challenges do Junior Iditarod competitors face on their 150-mile journey? Which strike you as most exciting, surprising, intimidating or dangerous?

3. What “unusual” set of skills do Iditarod competitors need to demonstrate over the two-day event? What skills, if any, do you think you possess that would make you a good musher? How do competitors like Anna Coke, 17, train and prepare for the race?

4. Among the prizes for the winner of the Junior Iditarod is a new dog sled, a beaver-fur hat and musher mittens. What benefits do all competitors gain from their experience, according to parents like Janet Martens?

5. The article concludes with a quotation from Julia Redington, a Junior Iditarod board member and one competitor’s mother: “They are all competitive, but it’s also about the journey and just what they learn.” Do you agree with Ms. Redington that the journey, whether in an athletic competition or an experience, is as important as the goal? What other lessons and inspiration do you draw from the article?

Going Further

Option 1: Share your experiences.

Choose one or more of the following writing prompts:

When have you faced a difficult journey or challenge, physical or mental? Write about the experience: What made it challenging? What obstacles did you need to overcome? Did you ever feel like giving up? How did you feel afterward? Would you say you were successful? What lessons about yourself, or the world, did you learn from your experiences?

Anna Coke said of competing in the junior race: “Nothing in the entire world can beat being out alone with your dogs, with your team. It brings you a lot of peace. And they push you to become a better person through that. They’re relying on you and you’re relying on them. It’s a really, really beautiful picture of teamwork and endurance and hard work.” How does her statement resonate with your experiences? Does anything both give you peace and push you to be a better person? What teaches you and tests your skills, your teamwork and your perseverance?

What does the story of these 10 teenagers navigating and enduring a grueling and often dangerous race say about what young people can do, with the right training and preparation? Does reading the article inspire you to push and challenge yourself more? Would you ever want to compete in a difficult endurance contest like the Iditarod, or, say, a triathlon or a marathon ? The article says that for some participants in the Junior Iditarod, the event would be the first time they spent a night away from their parents. Do you think young people need to have more opportunities to develop and test their independence and resourcefulness?

If you are inspired, set a new goal or challenge for yourself. It can be physical, intellectual or social, but reaching it should both push you and make a difference in your life. So think creatively and big! Keep in mind the example of Anna, who at 10 said to herself, “I’m going to pray every night that I would become a musher.” What is something you have always dreamed of or wanted to do? What kind of preparation will be required? What kinds of obstacles do you anticipate? How can you enlist others to help you on your journey? What lessons from the journey of teenagers like Anna, Morgan Martens and Ellen Redington can be applied to reaching your goal?

Option 2: Learn about how climate change is affecting the Iditarod race and other sports.

In the 2019 article “ The Mush in the Iditarod May Soon Be Melted Snow ,” John Branch wrote that climate change was forcing cancellations of, and changes in, sled dog races in Alaska and Canada, including the most famous of them all:

What used to be a given in Alaska — enough snow and ice to run the Iditarod and a slew of other sled dog races without much worry — is now fraught with perennial uncertainty. The cosmic question is how long races like the Iditarod in places like Alaska can keep finding long, continuous threads of snow and ice in a region warming more quickly than most places on the planet. Several races were altered, shortened or canceled this season. Every year, including this one, adjustments are made to counter problems attributed to warming. Twice in the past five years, the Iditarod moved the start to Fairbanks, 350 miles north. People now wonder aloud whether the Iditarod will have to climb the latitudinal ladder permanently to escape, or even if its long-term future is in peril. “In the grand scheme, it’s a very big deal,” said Jeff King, who this year is competing in his 29th Iditarod, beginning Sunday, and has won four times. “What we don’t know is how much, and how fast, climate change will result in those things.”

Are you surprised to learn that climate change is affecting sports events like the Iditarod? Global warming is not only melting the snow and ice necessary for dog sled runs, but it is also affecting sporting events across the globe, from tennis and soccer to speedskating and skiing .

Research one aspect of the effects of climate change on sports: What are the short- and long-term effects? How are sports leagues adapting to these environmental changes? What can be done to mitigate the damages?

To begin, you might research a sport that interests you, or read any of these articles:

Of 21 Winter Olympic Cities, Many May Soon Be Too Warm to Host the Games (The New York Times)

Climate Change Threatens Future of Sports (NPR)

Climate Change: Sport Heading for a Fall as Temperatures Rise (BBC)

Canceled Races, Fainting Players: How Climate Change Is Affecting Sport (World Economic Forum)

Sport, Climate Change and Acknowledging Vulnerability (The Sustainability Report)

After your research, consider how you might share what you learned: How can you best explain the information to others? You might create a poster , an infographic or a public service announcement, like this one , using images, video, text, statistics and music.

About Lesson of the Day

• Find all our Lessons of the Day in this column . • Teachers, watch our on-demand webinar to learn how to use this feature in your classroom.

Jeremy Engle joined The Learning Network as a staff editor in 2018 after spending more than 20 years as a classroom humanities and documentary-making teacher, professional developer and curriculum designer working with students and teachers across the country. More about Jeremy Engle

- Photo Gallery

- Stories for Students

- Browse Columns

- Presentations

- Print On Demand

- Contributors

The Last Great Race: Teaching the Iditarod

Iditarod ceremonial start in Anchorage, Alaska. Photo courtesy of Travis S., subject to a Creative Commons license

Known as the “Last Great Race,” the Iditarod is a race across the beautiful yet rough terrain of Alaska. Covering more than 1,150 miles, mushers and their dogs cross frozen rivers, dense forest, rocky mountains, desolate tundra, and windswept coast in anywhere from 10 to 17 days. Running the Iditarod means enduring subzero temperatures, snow storms, wildlife encounters, and other unexpected difficulties.

The Iditarod begins with a ceremonial start in downtown Anchorage, Alaska. Mushers and their teams race to Eagle River, Alaska. The next day, the race restarts in the rural town of Willow. Before 2002, the restart was held in the Matanuska Valley at Wasilla, but warmer winters, less snow, and tremendous development in the area have led race officials to make the change each year. In 2008, officials announced that the Willow restart would become a permanent change in the face of global warming and continuous development. Also changed is the first leg – traditionally spanning 18 miles from Anchorage to Eagle River. From 2008 onward, the first day of the race will cover only 11 miles.The Iditarod web site has an map that shows the route and also marks the positions of the mushers throughout the race.

The Iditarod alternates between two routes. This year, as in all even years, will follow the northern route through the villages of Cripple, Ruby, and Galena. Odd-numbered years follow the southern route through Shageluk, Anvik, and the ghost-town of Iditarod. Alternating routes decreases the impact of the large numbers of press and volunteers needed for the race and allows additional villages to participate.

Robert Sorlie. Photo courtesy of ra64, subject to a Creative Commons license.

History of the Iditarod

The Iditarod trail was historically used as a mail, supply, and gold route from coastal towns such as Seward and Knick to the interior mining camps of Flat, Ophir, and Ruby. The trail continued to the west coast communities of Unalakleet, Elim, Golovin, White Mountain, and Nome.

The Iditarod trail became famous in 1925, when a diphtheria epidemic threatened the community of Nome. A dog sled relay transported life-saving serum from Anchorage to Nome.

The Iditarod race has been run yearly since 1973. Always an important event to Alaskans, it has gained international popularity through competitors from Canada and Scandinavian countries, extensive press coverage, and the inclusion in classrooms around the world.

Why Teach about the Iditarod?

Even if you aren’t in Alaska, the Iditarod makes a great addition to your teaching practice! Teaching about the race is an opportunity to incorporate geography lessons, map skills, science concepts, and literacy skills into a real-world context. And there’s no denying the appeal of hundreds of hard-working, lovable dogs to children and adults!

Sled dog. Photo courtesy of Flauto, subject to a Creative Commons license.

Additionally, the common practice of having each student follow a musher through the race provides invaluable practice in reading expository texts (newspaper accounts) and using the real-time data available online.

Incorporating the Iditarod race can meet standards in a variety of content areas. We’ve highlighted some of the science, English language arts, geography, and social studies standards that you might fulfill while teaching about the race.

National Science Education Standards

Life Science Content Standard : Organisms and Environments (K-4) ; Populations and ecosystems (5-8)

Science in Personal and Social Perspectives Content Standard: Changes in environments (K-4); Populations, resources, and environments (5-8) (Read the entire National Science Education Standards online for free or register to download the free PDF. The content standards are found in Chapter 6 .)

National Council of Teachers of English/International Reading Association Standards

Standard 1: Read a wide range of print and nonprint text to acquire new information. Standard 3: Apply a wide range of strategies to comprehend, interpret, evaluate, and appreciate text. Standard 4: Communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes. Standard 5: Write and use different process elements. Standard 6: Create, critique, and discuss print and nonprint texts. Standard 7: Conduct, research and gather, evaluate and synthesize data. Standard 8: Use a variety of technological and informational resources. Standard 12: Use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes.

National Geography Standards

Standard 1: How to use maps and other geographic representations, tools, and technologies to acquire, process, and report information. Standard 4: The physical and human characteristics of places. Standard 12: The process, patterns, and functions of human settlement.

National Social Studies Standards

People, Places, and Environments Strand : Social studies programs should include experiences that provide for the study of people, places, and environments.

Photo courtesy of EDubya; subject to a Creative Commons license.

Teaching the Concepts

The official Iditarod web site offers many resources for educators, including lesson plans and activities. Education World also devotes an entire page to integrating the Iditarod across the curriculum.

Geography and Map Skills

Following the race lends itself well to teaching map skills such as the compass rose, cardinal and intermediate directions, and map scale. A lesson plan from the Iditarod site, Which Way to Nome? , focuses on these types of skills. Simply posting a large map of Alaska and the Iditarod trail in the classroom can provide a context for teaching and practicing geography and maps.

The changing conditions along the trail can provide the basis for inquiry-based activities about weather. The Iditarod Teacher Resources web page provides links to StormReady, curriculum materials for teaching about severe weather and safety. Another lesson plan, How’s the Weather? , combines math and science as students graph temperatures along the trail.

The Alaskan Environment (Integrated geography and science)

The Iditarod trail travels through a variety of environments: mountains, forests, rivers, tundra, and coastline. As the mushers encounter these new environments, students can learn about the plants and animals that live there, and the unique challenges posed by each.

Young Mushers

The Junior Iditarod is an annual 140-mile race that attracts 14- to 17-year-old mushers. It is held in Alaska a week before the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race. Students can read about this race and young mushers at Scholastic.com or from the Jr. Iditarod site .

Global Warming

In the past six years, warmer winters and a lack of snow have consistently challenged race officials. Snow has been trucked into Anchorage to create suitable conditions for the ceremonial start, and the restart has been moved from the town of Wasilla to Willow. These two changes are concrete examples for students of how Alaska’s climate is changing, and can serve as the basis for inquiry into why this change is occurring.

Technology Resources

The Iditarod web site also includes many technological features that are appropriate for use with students. Zuma’s Paw Prints is a student-friendly blog written from the perspective of four sled dogs: Zuma, Gypsy, Sanka, and Libby. Another feature, the Iditarod Insider , requires a subscription and features videos, trail fly-bys, and updated race content.

Literacy Connection

The Iditarod provides a wide variety of opportunities for literacy instruction and integration. We’ve highlighted a few ideas here, but don’t let these limit your creativity!

Many teachers have students adopt individual mushers and track their progress through news articles and online resources. This ongoing assignment integrates reading comprehension (reading the newspaper with adult assistance) and visual literacy skills (using tables, charts, and maps).

Students may also create a “musher scrapbook.” This scrapbook could include student-produced work such as a short biography of the musher and hand-drawn illustrations or media objects such as articles clipped from a newspaper or found online, and pictures.

Teachers of younger students may want to select one musher to follow as a class. Students can track progress on a large map displayed in the classroom. Students (or the class as a whole) could write and illustrate a story detailing the musher’s adventures along the path to Nome.

Some teachers and schools use the Iditarod as a reading challenge. Often dubbed the IditaRead, the challenge involves students taking the place of mushers. Students read a prescribed number of pages or minutes per day to advance to the next checkpoint along the Iditarod trail. An IditaRead can be designed as a contest or just a fun way to encourage students to read consistently. Many ideas for an IditaRead are available online.

Writing assignments can also be part of an Iditarod unit. Scholastic includes an online tutorial to help upper-elementary students write persuasive essays on how sled dogs are treated.

Suggested Reading

Booklists are available from both the Iditarod and Scholastic web sites. Rather than duplicate their work, we will simply direct you to their comprehensive and categorized lists! As always, your media specialist may be able to suggest additional titles for use in your classroom, or you may already have your own favorites.

Professional Development Opportunities

The Iditarod also presents several opportunities for professional development. Most prestigious, of course, is to be selected as the Teacher on the Trail . This teacher spends about 3 ½ weeks during race time in Alaska as a member of Iditarod’s educational team. He or she visits schools, presents programs, and flies from checkpoint to checkpoint during the race, reporting to classrooms all over the world via the Internet.

If you’re not the next Teacher on the Trail – don’t worry! Iditarod’s Education Department presents two yearly conferences – one the week before race time and one during the summer. Field trips, authors, Iditarod speakers and mushers provide opportunities to learn about raising and training sled dogs, running the Iditarod, and materials to incorporate these topics into your classroom. University credit is available.

This article was written by Jessica Fries-Gaither. For more information, see the Beyond Penguins and Polar Bears Contributors page. Email Kimberly Lightle , Principal Investigator, with any questions about the content of this site.

Copyright August 2011 – The Ohio State University. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0733024. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. This work is licensed under an Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported Creative Commons license .

- Terms of Use

- Funded by NSF

Travel | March 4, 2022

For 50 Years, Dogsled Teams Have Been Testing Their Mettle at the Iditarod

Three men who have lived and breathed the Alaskan race for much of its history recall how much has changed—and what has stayed the same

:focal(1000x667:1001x668)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/65/dd/65dd13d8-f808-417b-8cfc-93818d5f591c/201218-5f5504.jpg)

Jennifer Nalewicki

Travel Correspondent

In 1973, 34 sled dog teams lined up in Anchorage, Alaska, for the adventure of a lifetime: competing against one another to be the first team to reach Nome, approximately 1,000 miles to the northwest. It was the inaugural Iditarod, and at the time no one knew for sure how long it would take to complete the treacherous journey through sub-zero winds and dense snow. While the U.S. Army volunteered to help clear certain sections of the route, the mushers were largely responsible for breaking their own trails, while also hauling their supplies in their sleds.

The race course was so dangerous and desolate that it wasn’t uncommon to go days without seeing another soul; one-third of the competitors dropped out before reaching the finish line. Ultimately, it took the winner , Dick Wilmarth, a 29-year-old miner and trapper, about three weeks to cover the distance, snaring beaver for sustenance and using snowshoes in some sections to help clear the trail for his dogs. He revealed in a 2001 interview that he entered the race on a whim because he thought it would be “a pretty neat thing” to do.

In the five decades since, a lot has changed. Today, mushers rely on GPS to stay on course and are in constant communication with their support team, which helps coordinate supply drop-offs at designated checkpoints and regular veterinarian checkups for the dogs. The route is also well defined by markers and signs, and helicopters follow overhead to keep eyes on the ground and intervene in an emergency. (Teams take what’s called the “Northern Route” in even-numbered years and the “Southern Route” in odd years.) Subscribers to the Iditarod Insider even have access to a live feed of the event online.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/36/c4/36c4b27a-8e49-4239-8438-67c81ca5de1d/200205-5685.jpg)

“During the first race, people were wondering if anyone would even make it to Nome,” says Mark V. Nordman, the Iditarod’s long-time race director and marshal. “Now people finish it in under nine days. Like any sporting event, there’s always improvements like equipment and the quality of the trail that’s put in. I don’t want to say that the dog care has improved, it’s just that we enhanced our veterinary program so much—it truly is about taking care of the dogs.”

Nordman has a long history with the race, completing his first as a musher in 1983 in 18 days followed by four subsequent entries between 1991 and 1996. He’s served in his current capacity for decades, and has seen the Iditarod evolve from a little-known race in the wilds of Alaska where ham radio operators would give the blow-by-blow of the race over the AM airwaves to the longest and arguably most iconic annual sled dog race in the world, luring teams from Alaska and beyond to test their mettle against the often unforgiving elements.

“When it first started out, a lot of people thought it would be one-and-done,” he says. “But there’s a passion for it across the state. It’s our Stanley Cup. It’s our Super Bowl.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/83/66/836656c8-b9b5-40c0-b7e3-0a194edb0e71/gettyimages-1211280926.jpg)

Traveling by way of dog teams has long been a part of Alaska’s heritage . Since much of the state isn’t serviced by roads and highways and remains inaccessible, residents in remote areas came to rely on dog sleds to get them from point A to point B. However, with the introduction of the “iron dog,” or snowmobile, in the 1960s, the need for dog teams began to wane. The late Dorothy G. Page and Joe Redington, Sr. , known affectionately as “The Mother and Father of the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race,” created the event as a way to help preserve and protect sled dog culture and the working dogs that define it. The original race followed the old Iditarod Trail dogsled mail route, forged in the early 1900s, that stretched across the state; today’s course passes through multiple mountain ranges and crosses numerous frozen waterways and ice packs (sea ice).

This year’s race , beginning March 5, is particularly pertinent since it marks the event’s 50th year. The 50 teams entered as of writing will follow the race’s usual 1,049-mile route. (Because of the pandemic, the 2021 race was shortened to an out-and-back course of 852 miles and didn’t have its typical ceremonial start.) In order to participate this year, all competitors, as well as volunteers and other personnel, must be fully vaccinated .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/11/f5/11f59c15-bf55-430b-a5c9-fd7baf13b021/191225-5m9973.jpg)

Like Nordman, Jon Van Zyle , an acrylic painter who has lived in Alaska for 43 years, also has a long history with the race. Van Zyle competed in 1976, finishing the race in a little over 26 days without the help of a compass (or any of the other bells and whistles mushers use today). The next year, he approached the race committee, which he jokingly describes as “three people and a dog,” about creating a poster to help promote the event.

“At that time, very few people knew about it,” Van Zyle says. “I had an idea to raise money, since my artwork was starting to become popular in the United States.”

That 1977 poster , a mash-up of a landscape and a portrait of an Inuit man, was enough to earn him the title of the “Official Artist of the Iditarod.” Van Zyle has now completed dozens of posters and other artworks for the race, which have become collector’s items in their own right, often featuring sled dogs and mushers in action, always with Alaska in the backdrop. His work also earned him a place in the Iditarod Hall of Fame . To mark the Iditarod’s 50th anniversary, he created a limited edition poster blending a race scene with the likeness of Iditarod cofounder Joe Redington, Sr.

“Growing up, my mom had kennels, so I’ve been around sled dogs for most of my life and had been sledding long before the Iditarod,” he says. “I paint what I know, and what I know is Alaska.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c1/05/c10558e8-f473-4706-848b-7ebda78149f7/200104-5f0015.jpg)

Recently, Van Zyle partnered with another icon within the dog racing community: Jeff Schultz . As the “Official Photographer of the Iditarod,” Schultz has been documenting the race from start to finish since 1981.

“I was still in my 20s and could only afford to hire a pilot to take me to the race’s halfway point,” Schultz says. “I donated my photos to the committee and they came back and asked me to do it again next year, [this time providing me with adequate transportation]. It was a handshake deal.”

Over his decades-long career, Schultz’s photographs have become synonymous with Alaska. In 1990, he founded the state’s largest stock photo agency, Alaska Stock Images, and his work has been featured in everything from the pages of Outside magazine to Wells Fargo ad campaigns.

For most people, their only experience with the Iditarod is through Van Zyle’s paintings and Schultz’s photographs, and over the years the artists’ imagery, used to promote the event, has become as iconic as the sled dogs and the Alaska terrain that define the race. Many of their prints and posters have been featured in art galleries, and, as collector’s items, they sell at auction for hundreds of dollars.

“I’ve had people write letters to me saying that they learned about the Iditarod because of me,” Schultz says. “I’ve heard from people who were kids when they first saw my images, and now they race in the Iditarod.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/de/13/de13c403-b119-418c-a1a8-cf0f4c827818/200104-5f9985.jpg)

Last year, the creative pair published a book, co-written by their wives, Jona Van Zyle and Joan Schultz, who are also actively involved in the dogsled community. Double Vision Alaska contains more than 120 photographs and paintings, including a collaborative series in which Van Zyle applies acrylic paint to Schultz’s photos. The painter, for example, added mushers, dog teams and cabins to a snowy sunset scene photographed by Schultz. In another, he painted a red Cessna Skywagon over a photo of rugged snowy peaks.

In their combined 87 years with the Iditarod, Van Zyle and Schultz have had a front-row seat, witnessing the race’s evolution and growth firsthand.

“The race has changed 5,000 percent,” Van Zyle says. “When I ran it in the early years, it took us 25 to 30 days to finish. Back then mushers would cut spruce boughs for the dogs to rest on to get off the snow, but now there’s straw flown into every checkpoint. Of course, the clothing has changed, and then you have better communication systems with tracking devices on the sleds, and the trail is now an actual trail instead of snowshoeing in front of our dogs all day long. At one time, there was one pilot who flew supplies in, but that was only if he got there. The rest was catch-as-catch-can.”

And yet, one thing has remained the same: that sense of adventure felt not only by the mushers and their dogs, but by anyone experiencing the event, from spectators on the sidelines in villages across Alaska to readers of the artists’ new book hundreds of miles away.

“I’ve been on the Iditarod trail for over 40 years and it’s a total adventure that can last a lifetime,” Schultz says. “I love being between checkpoints, when it’s just the dog team and the landscape, and the only thing you hear is the panting of the dogs. That aspect of it is phenomenal. You get to travel through small, Native villages where everyone comes out to greet the mushers, and the dogs. On the trail, you get to experience this glory each day for ten days straight. It’s a letdown once you do get to Nome.”

Get the latest Travel & Culture stories in your inbox.

Jennifer Nalewicki | | READ MORE

Jennifer Nalewicki is a Brooklyn-based journalist. Her articles have been published in The New York Times , Scientific American , Popular Mechanics , United Hemispheres and more. You can find more of her work at her website .

History of Skiing & Snowsports

PROJECTS BY EMORY UNIVERSITY HISTORY STUDENTS

Dog Days of Winter: The Iditarod in the Modern Age

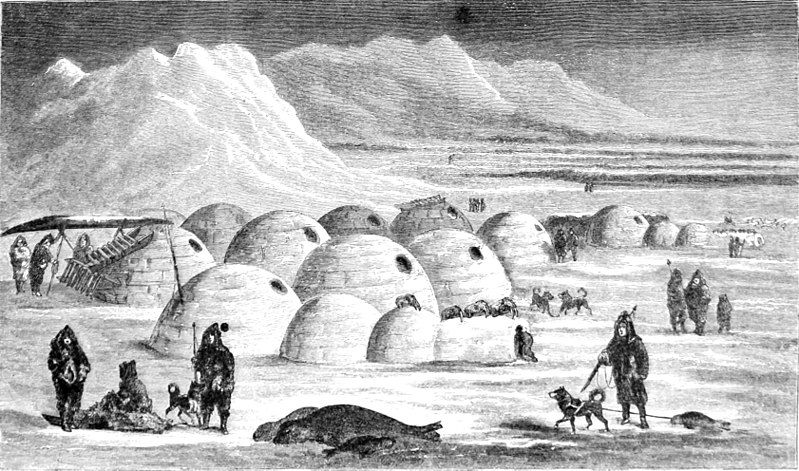

Dogs have played a part in Alaskan life for centuries, dating back at least 500 years if not more. One of the most notable ways in which indigenous Alaskans interacted with their dogs was through the dogsled, which for centuries served as the primary, if not only, method of traversing the cold arctic terrain. This reliance on sled dogs made them a critical part of Native Alaskan society even into the 19 th and early 20 th centuries, as sled dogs are depicted in early Inuit interactions with outside settlers in the 1800s. Most famously, they were utilized in the 1925 sled run to Nome, a dogsled relay to deliver medicine during a diphtheria outbreak.

However, as the 20 th century progressed, the traditional sled dog became less common as a form of transportation, giving way to mechanized vehicles and more modern technologies. While these new developments offered meaningful improvements in transportation, they would also phase out a cherished Alaskan tradition with a rich, storied history.

In the 1960s and 70s, a group of Native Alaskans, concerned that the dogsledding tradition and its role in Alaskan history would fade out of public memory, devised a way to revive the practice in the modern age. So was born the Iditarod, a dogsled race across the famous Iditarod Trail. The founders hoped that the race would allow them to keep in touch with the traditional Alaskan spirit and their roots. But how would dogsledding survive against the technological and capitalist forces that caused its initial decline? And how could it do so in a way that maintained the true traditional spirit of the practice and preserved the premodern culture?

Origins of Dogsledding in Alaska

Though there is not a clear consensus dating the true origins of dogsledding in North America, dogs played a critical part in Indigenous Alaskan society. According to a report from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, archeological evidence suggests that Indigenous peoples along the Alaskan coast kept dogs several thousand years ago, and the practice of using dogs to pull sleds arose in Alaska at least 500 years ago. By the time European explorers established contact with the Inuit people in the mid-19 th century, keeping dogs and the practice of dogsledding had become a visible part of native Alaskan identity. In the early 1860s, American explorer Charles Francis Hall chronicled an Arctic expedition in his narrative Life with the Esquimaux . In one passage, he writes that upon approaching “a complete Esquimaux village, all the inhabitants, men, women, children, and dogs, rushed out to meet [him].” This inclusion of dogs in the characterization of a “complete” village portrays the central role that the dogs played in the Native villages. Later in the book, he goes on to note some of the ways that dogs and dogsledding were used, writing that dogs were brought along on trips to hunt seals, and noting the use of sled dogs to transport food and supplies across the terrain.

Dog teams were frequently used by Indigenous Inuit peoples for hunting, and sledding became the premier form of land transportation. The reports of Russian explorer Lt. Lavrentii Zagoskin note that the Native people utilized a well-established network of dogsled trails to traverse the icy Arctic terrain. As American settlements came to Alaska in the late 19 th and early 20 th centuries, the use of the sled dog would only increase in prominence. Sled dogs were able to cross areas that were not accessible to automobiles at the time, so dogsled use remained the only way to transport people and equipment across Alaska. Sled dogs would become the basis of the mail service and various supply chains, crossing the expansive Alaskan trail network. The predominant dogsled trail was known as the Iditarod Trail. Spanning across Alaska, from Nome on the West Coast to Seward in the Alaskan Gulf, the Iditarod would be the primary dogsled thoroughfare through Alaska.

For centuries, dogsledding was unrivaled in its relatively low cost, reliability, and ability to cross terrain that was inaccessible by any other method. However, modern technology would soon challenge its dominance as a mode of transportation and diminish the prominence of this staple of Indigenous life.

“Decline of the Dogsled”

In the mid 20 th century, developments in technology would provide a more modern alternative to the sled dog, specifically in the form of the mechanized toboggan. This new technology was faster than the traditional dogsled, and offered considerable advantages in terms of maintenance and safety. These advantages were quickly realized among Alaskans, and the decline of the dogsled in favor of the mechanized toboggan would become immediately apparent through in the 1960s. In 1968, a study by Karl E. Francis sent out a questionnaire to residents of 27 villages in northern, western, and interior Alaskan villages asking for details on the use of dogsleds and mechanized toboggans between 1963 and 1968. (Francis does not specify the ethnic demographics of the respondents; however, he notes that the population of the responding villages covered most of the population of arctic Alaska at the time. To get some insight into the demographics of the respondents, we can look to a report from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game studying demographic trends. The oldest available report on the ethnic breakdown of rural Alaskans is from 2000, roughly 30 years after Francis’ study; this report notes that 54% of rural Alaska residents identify as Alaska Natives. While the reports are not exactly from the same time period, we can hypothesize that Alaskan villages of the late 1960s contained a significant Alaska Native population.)

While some questionnaire respondents signaled an affinity for the traditional mode of transportation, and the mechanized toboggan posed some shortcomings with regard to cost concerns and mechanical failures, the shift towards the more modern technology was clear. Across the five-year period from 1963 to 1968, the number of mechanized toboggans in use increased fivefold, from 187 to 974. Meanwhile, across that same period, the number of active dogsled teams decreased from 726 to 420, a roughly 42% decrease.

Given that a sizeable fraction of the respondents were likely Alaska Natives, this shift away from the traditional practice comes with greater implications regarding the decline of indigenous customs. In addition to causing the contributions of generations of Alaska Natives to fade from memory, the replacement of tradition with technology also poses serious and immediate practical concerns. Just as the mechanized toboggan challenged the status of the dogsled, a similar phenomenon occurred slightly later in the 20 th century with the invention of the GPS leading to a loss of traditional Inuit navigational practices. A paper by Dr. Claudio Aporta of Dalhousie University and Dr. Eric Higgs of the University of Victoria study how the adoption of GPS as the primary guider of navigation caused a decline in proper understanding of the geography and environment, as that knowledge is acquired by learning the traditional Inuit wayfinding methods. Aporta and Higgs assert that, while the GPS can provide assistance when navigating, it is unable to actually provide and pass on knowledge to the user. They write that “many younger people do not have the depth of knowledge to move about safely,” and many older Inuit blame the modern GPS technology for eroding that historic knowledge among the new generation. Francis also supports this belief, noting that despite the speed and economic advantages of the mechanized toboggan, “there is considerable evidence that the famed Eskimo skill for finding his way home in a storm is not nearly so effective without dogs,” once again indicating the tendency of technology to reduce traditional skills and knowledge.

Both authors also express concerns about the reliability of modern technology, noting that electronic parts are sometimes prone to failure, especially in the cold Alaskan winters. By contrast, traditional practices come with centuries of proof of reliability. In the event of mechanical failure, it is critical that knowledge of the traditional practices is not lost, as they may be the only hope for a stranded navigator.

Reviving the Practice

In the mid-to-late 1960s, a committee of Alaskans was tasked with scheduling events to commemorate the upcoming 1967 celebration of Alaska’s centennial year being a part of the United States. Among this group was Dorothy Page, who would come to be known later as the “Mother of the Iditarod.” Although Page was not an Alaska Native, having spent most of her early life elsewhere in the United States before moving to Alaska in 1960, she became very involved with Alaskan public service projects, and was dedicated to preserving Alaskan history and tradition. Page felt that the decline in the prominence of dogsledding had caused many Alaskans to lose touch with this historic practice, even to the extent of forgetting about its existence and prominent role in Alaskan history. She proposed “a spectacular dog race to wake Alaskans up to what mushers and their dogs had done for Alaska,” placing the practice back into the public eye. She reached out to dog musher Joe Redington, Sr., a veteran of World War II, who moved to Alaska in 1948 and took up competitive sled dog racing. Although neither Page nor Redington was an Alaska native, they both shared a passion for preserving the traditional indigenous custom of dogsledding, and the two of them would collaborate to organize the first Iditarod race. The first two races, in 1967 and 1969, were held along a short subsection of the trail, a nine mile stretch from Knik to Big Lake. However, in 1973, the race would expand to cover the full Iditarod trail, as racers traversed 1,000 miles of Alaskan wilderness and revived the classic mode of trans-Alaskan travel, in a race that is replicated each year to this day.

Iditarod in the 21 st Century

For the last 50 years, the Iditarod race has functioned as a way for Alaskans to connect with the storied tradition of dogsled racing, and has gained international attention, viewers from around the world. In addition, the population of dog mushers who participate in the competition has branched out globally as well, including not just indigenous Alaskans and other Alaska residents, but also competitors from elsewhere in the United States and occasionally even abroad.

To understand how the Iditarod has maintained its popularity, we can explore the motivations of the tourists who visit Alaska to witness it. While it may seem like these tourists are simply traveling to view a sporting event, many of them are in fact driven by forces of cultural tourism and “salvage tourism”, traveling to experience facets of native and indigenous culture.

When viewing the Iditarod through the lens of salvage tourism, find it to be a foundational principle of the race’s founding. In Staging Indigeneity , Katrina M. Phillips writes that “salvage tourism is explicitly tied up in trying to salvage American Indian cultures before Indians, in the minds of non-Natives, die off, change, or degenerate from their ideals of a pristine Indian past,” a sentiment that echoes strongly in the story of Page and Redington founding the Iditarod. Neither of the founders were Alaska natives, but they felt that Alaskans, even indigenous people, had forgotten the dogsledding tradition, and they sought to “salvage” the custom. The transformation of dogsledding from a standard means of transportation into the spectacle of a sporting competition reflects another principle of salvage tourism, which is that “It requires transformation and reinterpretation; [and] the commodification of a distinct historical narrative.”

Those who travel to Alaska to watch the Iditarod are also deeply involved in the practice of salvage tourism, stimulating the economies of smaller Alaskan villages which are dependent on the attention the race brings. While this may be a more subtle, implicit aspect of some tourists’ trips to Alaska, for others it is this preservation of indigenous culture that motivates their travels. A master’s thesis by Paulien Becker, from the University of Tromsø in Norway, interviewed tourists attending the Iditarod about their motives for visiting. One respondent, who had visited Alaska on multiple occasions, responded “ I love talking to the people and learning about what brought them here and why they stayed. Talking to native Alaskans about their traditions and culture is priceless.’’ This marketing of the Iditarod as a way for non-indigenous tourists to connect with indigenous culture is aligned with the principle of salvage tourism and has certainly contributed to the survival of Alaskan dogsledding, though it has certainly been modified from its original form.

However, preserving the practice of dogsledding faces strong challenges in the modern era. A recent article from Fortune magazine analyzed the decline of the Iditarod race in the last few years. This decline was on full display during the 2023 race, which hosted the fewest competitors ever, fewer than even the first full-length race in 1973. Many mushers believed that the rising costs of training caring for a sled dog team, combined with the relatively meager payout for the winner, made participating economically infeasible for many competitors. During the fall and winter seasons, teams will train and compete in smaller dogsled races in preparation for the start of the Iditarod in March. In the summer, many mushers will supplement their income by taking part in the tourism industry, offering sled dog rides to visitors who come to experience Alaskan life. Unfortunately, the recent combination of high inflation and a decline in tourism due to COVID-19 has caused many mushers to drop out, unable to keep up with the expenses of putting together an Iditarod team.

Another more long-term threat to the practice of dogsledding is climate change, as rising temperatures impact the amount and quality of sleddable area and cause thinner ice. Rick Thoman, a climate specialist from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, writes that even a small amount of melting can threaten the safety of dogsled teams, since “it just has to be at the point where the ice is not stable.” As threats to the long-term sustainability of the Iditarod and of the greater dogsledding practice loom large, there still remains hope that the tradition will survive. One optimist is Brent Sass, a Minnesotan dog musher and longtime Iditarod participant who won the race in 2022. Speaking with Fortune magazine, Sass expressed his belief that the sport will see a comeback as the economy recovers, and the costs of maintaining a dog team settle back down. Also, in a nod to tradition, the 2023 winner was Ryan Redington, grandson of Iditarod co-founder Joe Redington, Sr. and an Inupiat Alaska native. The second and third place finishers were also Alaska natives, a powerful signal that the sport has not strayed too far from its indigenous roots.

Acknowledgements

Massive thanks to Dr. Judith Miller for all her help and support on this project! Also a huge thank you to the University of Alaska Anchorage Consortium Library Archives for providing permission to use their photograph.

Bibliography

Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Subsistence. Alaska Population Trends and Patterns, 1960–2018 , by James A. Fall. Juneau, 2019.

Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Subsistence. The Use of Dog Teams and the Use of Subsistence-Caught Fish for Feeding Sled Dogs in the Yukon River Drainage , by David B. Andersen. Technical Paper No. 210. Juneau, 1992.

Ameen, Carly, Tatiana R. Feuerborn, Sarah K. Brown, Anna Linderholm, Ardern Hulme-Beaman, Ophélie Lebrasseur, Mikkel-Holger S. Sinding, et al. “Specialized Sledge Dogs Accompanied Inuit Dispersal across the North American Arctic.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 286, no. 1916 (2019): 20191929. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.1929

Aporta, Claudio, and Eric Higgs. “Satellite Culture: Global Positioning Systems, Inuit Wayfinding, and the Need for a New Account of Technology.” Current Anthropology 46, no. 5 (2005): 729–53. https://doi.org/10.1086/432651.

Arwezon, Bob. 1973 Iditarod Start in Anchorage. February, 1973. Photograph. Anchorage, February 1973. Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage.

Becker, Paulien. “The Different Types of Tourists and their Motives when Visiting Alaska during the Iditarod.” Master’s thesis, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, 2014.

“Dorothy G. (Guzzi) Page.” City of Wasilla, AK. Accessed April 27, 2023. https://www.cityofwasilla.gov/services/departments/museum/history/dorothy-page.

“Dorothy Page Honored.” Iditarod: The Last Great Race. Iditarod Trail Committee, May 3, 2018. Last modified May 3, 2018. Accessed May 1, 2023. https://iditarod.com/dorothy-page-honored/.

Foss, Katherine A.. “Racing ‘The Strangler’: The Nome Diphtheria Outbreak of 1925.” In Constructing the Outbreak: Epidemics in Media and Collective Memory , 149–72. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2020.

Francis, Karl E. “Decline of the Dogsled in Villages of Arctic Alaska: A Preliminary Discussion.” Yearbook of the Association of Pacific coast Geographers 31, no. 1 (1969): 69-78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24041087.

Hall, Charles Francis. Life with the Esquimaux: The Narrative of Captain Charles Francis Hall of the Whaling Barque George Henry from the 29th May, 1860, to the 13th September, 1862. Vol. 1 . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

“Iditarod Co-Founder’s Grandson Ryan Redington Wins Dog Race.” The Associated Press, March 14, 2023. Last modified March 14, 2023. Accessed May 2, 2023. https://www.nbc15.com/2023/03/14/iditarod-co-founders-grandson-ryan-redington-wins-dog-race/.

Jones, Preston. Empire’s Edge: American Society in Nome, Alaska, 1898-1934 . Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2007.

Kaufman, Michael T. “Joe Redington, Co-Founder Of Dog Sled Race, Dies at 82.” The New York Times , June 27, 1999.

Lantis, Margaret. “Changes in the Alaskan Eskimo Relation of Man to Dog and Their Effect on Two Human Diseases.” Arctic Anthropology 17, no. 1 (1980): 1–25. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40315965.

Phillips, Katrina. Staging Indigeneity: Salvage Tourism and the Performance of Native American History . UNC Press Books, 2021.

Simpson, Sherry. “‘DOGS IS DOGS’: Savagery and Civilization in the Gold Rush Era.” In The Big Wild Soul of Terrence Cole: An Eclectic Collection to Honor Alaska’s Public Historian , edited by Frank Soos and Mary Ehrlander, 59–76. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2019. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv21fqhzt.8.

Smith, Valene L. “Eskimo Tourism: Micro-Models and Marginal Men.” In Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism , edited by Valene L. Smith, 2nd ed., 55–82. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt3fhc8w.7.

“The Beginning.” Iditarod: The Last Great Race. Iditarod Trail Committee, February 4, 2012. Last modified February 4, 2012. Accessed April 26, 2023. https://iditarod.com/about__trashed/the-beginning/.

Thiessen, Mark. “The World’s Iconic Iditarod Dog Sled Race Has the Fewest Competitors Ever Because Its $50,000 Prize Isn’t Enough to Keep up with Inflation.” Fortune. Fortune, March 1, 2023. Last modified March 1, 2023. Accessed April 26, 2023. https://fortune.com/2023/03/01/inflation-hurts-contestants-iditarod-dog-sled-race-alaska/.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of followup comments via e-mail

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Iditarod and Animal Cruelty

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/dorislin2-77cc0f7bb4a34be3ba4644a99f6e6a89.jpeg)

- University of Southern California

Daniel A. Leifheit / Moment / Getty Images

- Animal Rights

- Endangered Species

The Iditarod Trail dog sled race is a sled dog race from Anchorage, Alaska to Nome, Alaska, a route that is over 1,100 miles long. Aside from basic animal rights arguments against using dogs for entertainment or to pull sleds, many people object to the Iditarod because of the animal cruelty and deaths involved.

“[J]agged mountain ranges, frozen river, dense forest, desolate tundra and miles of windswept coast . . . temperatures far below zero, winds that can cause a complete loss of visibility, the hazards of overflow, long hours of darkness and treacherous climbs and side hills.”

This is from the official Iditarod website.

The death of a dog in the 2013 Iditarod has prompted race organizers to improve protocols for dogs removed from the race.

History of the Iditarod

The Iditarod Trail is a National Historic Trail and was established as a route for dog sleds to access remote, snowbound areas during the 1909 Alaskan gold rush. In 1967, the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race began as a much shorter sled dog race, over a portion of the Iditarod Trail. In 1973, race organizers turned the Iditarod Race into the grueling 9-12 day race that it is today, ending in Nome, AK. As the official Iditarod website puts it, “There were many who believed it was crazy to send a bunch of mushers out into the vast uninhabited Alaskan wilderness.”

The Iditarod Today

The rules for the Iditarod require teams of one musher with 12 to 16 dogs, with at least six dogs crossing the finish line. The musher is the human driver of the sled. Anyone who has been convicted of animal cruelty or animal neglect in Alaska is disqualified from being a musher in the Iditarod. The race requires the teams to take three mandatory breaks.

Compared to previous years, the entry fee is up and the purse is down. Every musher who finishes in the top 30 receives a cash prize.

Inherent Cruelty in the Race

According to the Sled Dog Action Coalition , at least 136 dogs have died in the Iditarod or as a result of running in the Iditarod. The race organizers, the Iditarod Trail Committee (ITC), simultaneously romanticize the unforgiving terrain and weather encountered by the dogs and mushers, while arguing that the race is not cruel to the dogs. Even during their breaks, the dogs are required to remain outdoors except when being examined or treated by a veterinarian. In most U.S. states, keeping a dog outdoors for twelve days in freezing weather would warrant an animal cruelty conviction, but Alaskan animal cruelty statutes exempt standard dog mushing practices: "This section does not apply to generally accepted dog mushing or pulling contests or practices or rodeos or stock contests." Instead of being an act of animal cruelty, this exposure is a requirement of the Iditarod.

At the same time, Iditarod rules prohibit “cruel or inhumane treatment of the dogs.” A musher may be disqualified if a dog dies of abusive treatment, but the musher will not be disqualified if

“[T]he cause of death is due to a circumstance, nature of the trail, or force beyond the control of the musher. This recognizes the inherent risks of wilderness travel.”

If a person in another state forced their dog to run over 1,100 miles through ice and snow and the dog died, they would probably be convicted of animal cruelty. It is because of the inherent risks of running the dogs across a frozen tundra in sub-zero weather for twelve days that many believe the Iditarod should be stopped.

The official Iditarod rules state, “All dog deaths are regrettable, but there are some that may be considered unpreventable.” Although the ITC may consider some dog deaths unpreventable, a sure way to prevent the deaths is to stop the Iditarod.

Inadequate Veterinary Care

Although race checkpoints are staffed by veterinarians, mushers sometimes skip checkpoints and there is no requirement for the dogs to be examined. According to the Sled Dog Action Coalition, most of the Iditarod veterinarians belong to the International Sled Dog Veterinary Medical Association, an organization that promotes sled dog races. Instead of being impartial caregivers for the dogs, they have a vested interest, and in some cases, a financial interest, in promoting sled dog racing. Iditarod veterinarians have even allowed sick dogs to continue running and compared dog deaths to the deaths of willing human athletes. However, no human athlete has ever died in the Iditarod.

Intentional Abuse and Cruelty

Concerns about intentional abuse and cruelty beyond the rigors of the race are also valid. According to an ESPN article :