Latest Articles

Low Energy Availability (LEA) in Male Athletes: A Review of the Literature

George Minoso 2024-10-21T09:45:40-05:00 October 23rd, 2024 | Book Reveiws , Research , Sports Nutrition |

Authors: Brandon L. Lee 1

1 The Department of Exercise, Health, and Sport Sciences, Pennsylvania Western University

Corresponding Author:

Brandon L. Lee, MS, RD, CCRP 10263 4th Armored Division Dr. Fort Drum, NY 13603 [email protected] 315-772-0689

Brandon L. Lee, MS, RD, CCRP is a Holistic Health and Fitness (H2F) Dietitian for the U.S. Army Forces Command and a Doctor of Health Science (DHSc) student at Pennsylvania Western University. Brandon’s research interests include energy systems and metabolism, energy availability, andragogical methods for adult learning, and reflective practice to enhance learning in formal education..

Purpose: Low energy availability (LEA) is a physiological state when there is inadequate energy to meet the demands placed on the body, often through physical activity, exercise, or sports. LEA can impact any athlete engaged in a sport with low energy intake or excessive energy expenditure. LEA is a precursor to the onset of The Male Athlete Triad (MAT) and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). There is no defined low energy availability threshold specific to male athletes engaged in high-energy expenditure sports leading to MAT and RED-S. This literature review evaluates the literature on the relationship between LEA and signs or symptoms of MAT and RED-S to establish a low energy availability threshold specific to male athletes engaged in high-energy expenditure sports.

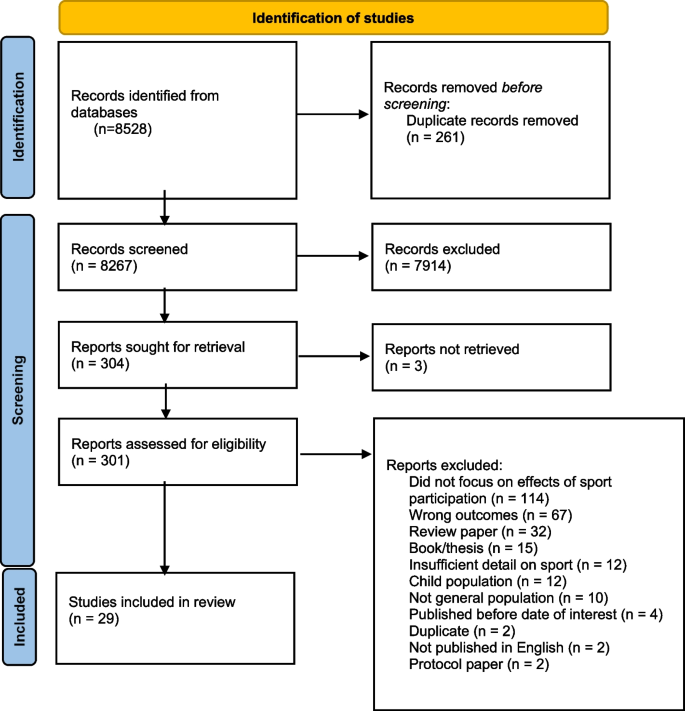

Methods: The Pennsylvania Western University library electronic database was used for the literature search. Search terms included “male athletes”, “low energy availability”, “male athlete triad”, “relative energy deficiency in sport”, and “energy deficiency”. Research studies included cross-sectional, experimental, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, case studies, and some narrative and literature reviews. Studies must have been peer-reviewed and published within five years of the literature search (12/2018- 12/2023).

Results: A review of the literature shows that it is difficult to determine a LEA threshold due to present research gaps and inconsistent findings related to health and performance consequences. Based on the results of experimental studies, practitioners can expect an LEA threshold of 20-25kcal per kilogram (kg) of fat-free mass (FFM) per day in male athletes engaged in high energy-expenditure sports.

Conclusions: Athletes engaged in sports that lead to inadequate energy intake or high energy expenditure are at risk for LEA, MAT, and RED-S. Experimental research on the LEA threshold in athletes engaged in physiologically demanding sports is the greatest research gap. Based on present findings, male athletes may have an LEA threshold of <30kcal/kg of FFM/day.

Applications in Sport: Healthy nutritional practices are essential to sports performance. Interdisciplinary sports performance teams must collaborate with nutrition professionals to develop effective LEA prevention, screening, and intervention protocols.

Keywords: energy intake, energy deficiency, energy expenditure of exercise, male athlete triad, relative energy deficiency in sport, sports nutrition

Energy availability (EA) is the energy dedicated to body system functions. In sports nutrition, energy availability is defined as the amount of energy remaining to support an athlete’s bodily functions after energy expenditure of exercise (EEE) is deducted from energy intake (EI) (2). Health and athletic performance issues arise when athletes have inadequate energy intake or excessive energy expenditure, depleting their EA. The designated term for this is low energy availability (LEA). LEA is defined as a physiological state when there is inadequate energy to meet the demands placed on the body, often through physical activity, exercise, or sports (23). Causes of LEA include obsessive causes (disordered eating or eating disorders), intentional causes (attempts to modify body mass or composition), and inadvertent causes (byproduct of high EEE) (1). LEA can impact any athlete engaged in a sport with low energy intake or excessive energy expenditure. LEA is most common in sports of high intensity, duration, volume, or frequency and in sports that emphasize low body weight/fat, aesthetics, or thinness, including distance cycling and running, triathlons, tactical (i.e., military), swimming, gymnastics, wrestling, bodybuilding, martial arts, boxing, soccer, tennis, rowing, horse racing, and volleyball. LEA is a precursor to the onset of both The Male Athlete Triad (MAT) and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S), two conditions that result in weakened physiological functions, with the former focused on reproductive and bone health decline (22). The problem is the prevalence of LEA among male athletes participating in high-energy expenditure sports, leading to potential health and performance issues. Additionally, there is no defined low energy availability threshold specific to male athletes engaged in high-energy expenditure sports leading to MAT and RED-S (3, 4, 5, 9, 11, 14, 17, 22, 26). This literature review aims to evaluate the literature on the relationship between LEA and signs or symptoms of MAT and RED-S to establish a defined low energy availability threshold specific to male athletes engaged in high-energy expenditure sports. This literature review will report on LEA’s impact on health, body composition, athletic performance; establish LEA thresholds, and address research gaps.

RELATIVE ENERGY DEFICIENCY IN SPORT (RED-S) LEA is a common precursor to many health and athletic performance issues. In 2014, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) developed a consensus statement titled “Beyond the Female Athlete Triad: Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S)” and established RED-S as a new condition that refers to diminished physiological processes due to relative energy deficiency. The most current IOC RED-S models show that RED-S can impact the following systems: immunological, menstrual/reproductive function and bone health (related to athlete triad), endocrine, metabolic, hematological, growth and development, psychological, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal. Moreover, another IOC RED-S model shows the potential performance effects of RED-S, including decreased endurance performance, increased injury risk, decreased training response, impaired judgment, decreased coordination, decreased concentration, irritability, depression, decreased glycogen stores, and decreased muscle strength (19). Much of the research on the impact of LEA and the cascade of events that lead to RED-S has primarily been conducted on female athletes, and the findings are extrapolated to their male counterparts; however, this is changing.

MALE ATHLETE TRIAD The Male Athlete Triad (MAT) was first introduced in the 64th Annual Meeting of the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) in 2017 (6). MAT has comprised three essential components: LEA (sometimes referred to as energy deficiency), impaired bone health, and suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis (22). Prevention and treatment methods of MAT hinge on the EA or energetic status of the athlete at risk. Nattiv et al. (2021) explain that energy deficiency or LEA is confirmed when one of the following metabolic adaptations is presented: reduced RMR compared to body size or fat-free mass (FFM), unintentional weight loss resulting in a new low set point, underweight body mass index (BMI), and reduced metabolic hormones such as triiodothyronine (T3), leptin, and several more. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism can manifest as oligospermia (deficiency of sperm in the semen) or decreased libido (reduced sexual drive). Lastly, poor bone health can manifest as osteopenia, osteoporosis, or bone stress injury (22). The energetic status of the athlete can vary greatly depending on frequency, intensity, duration, type of sport, volume, and progression. Nattiv et al. (2021) have surmised that male athletes engaged in leanness sports typically have low energy intake compared to recommended amounts from the Institute of Medicine Daily Recommended Intakes or Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Health Organization. Unfortunately, male leanness sports or weight-class athletes potentially consume up to 1000kcal/day less than required to support their exercise demands (22). Athletes consistently at risk for MAT include runners and cyclists, primarily if they compete in long-distance competitions.

Cardiovascular Health Cardiovascular health (CVH) is essential to every athlete engaged in any sport. A healthy cardiovascular system effectively moves blood from one location to another to transport oxygen-containing blood cells for muscular activity. Langan-Evans et al. (2021) studied the impact of incorporating daily fluctuations in LEA on cardiorespiratory capacity via treadmill test in one combat athlete preparing to make weight for competition. The athlete experienced microcycle EA fluctuations ranging from 7 to 31 kcal per kilogram (kg) of FFM/day (mean EA of 20kcal/kg of FFM/day) for seven days and did not experience any significant changes in resting heart rate, cardio output, or overall CVH (14). Theoretically, LEA would have significant structural, conduction, repolarization, and peripheral vascular effects on CVH (17). However, a scant amount of research establishes any correlation between CVH and LEA, and primary research studies conducted within the past five years have yet to establish causation between the two. On the other hand, Fagerberg (2018) has found that EA <25kcal/kg FFM over six months in bodybuilders preparing for a competition can impact CVH by reducing heart rate. According to Fagerberg (2018), low body fat percentages in bodybuilders worsen CVH risk (4). This heart rate reduction, paired with low body fat, is likely a physiological adaptation to conserve energy and sustain life. There needs to be more consistency in the literature regarding the impact of LEA on CVH.

Physiological Health LEA and RED-S are both physiological and psychological health risks. Sports that emphasize leanness (e.g., cycling) or have weight divisions (e.g., combat sports) often place additional mental stress on athletes to perform well and possess a specific physique. For example, Schofield et al. (2021) found that male cyclists are at risk for LEA and RED-S due to rigid weight management practices, desire for leanness, disordered eating and eating disorders, and body dissatisfaction (26). Elevating psychological health is commonly conducted via a questionnaire or interview. Langbein et al. (2021) explored the subjective experience of RED-S in endurance athletes through semi-structured, open-ended interviews. The first male participant commented on hitting “rock bottom” and the body’s sensitivity to energy intake changes. In addition, the other male athlete appeared to have a transactional relationship with food and exercise, void of any joy or performance goals. Both male athletes reported negative psychological consequences regarding RED-S; these consequences included increased rates of irritability because they were obsessed with food and exercise and feelings of helplessness and despair (15). Perelman et al. (2022) also examined the male athlete’s psychological state by evaluating and intervening on body dissatisfaction, drive for muscularity, body-ideal internalization, and muscle dysmorphia. Male athlete participants (n=79) were from various sports, including baseball, golf, soccer, swimming, track and field, volleyball, and wrestling. The results showed that group sessions focused on reframing ideal body perception, the consequences of RED-S, encouraging positive self-talk, and reviewing strategies to modify energy balance healthfully can significantly reduce body dissatisfaction, body-ideal internalization, and drive for muscularity (p < .05) (24). The results demonstrate the value of understanding, supporting, and guiding an athlete’s psychological state toward personal health and satisfaction.

Reproductive Health Functional hypogonadotropic hypogonadism is one of the three primary pillars of the MAT. LEA can induce disruptions to the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, resulting in functional hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Signs of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism include (1) reductions of testosterone (T) and luteinizing hormone (LH), (2) decreased T and responsiveness of gonadotropins to gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) stimulation after training, (3) alterations in spermatogenesis, and (4) self-reported data on decreased libido and sexual desire (22). Most current research studies examine free and total T as an indicator of HPG axis suppression. Lundy et al. (2022) categorize low total T (<16nmol/L) and low free T (<333 pmol/L) as primary indicators for LEA (16). A significant contribution to this area comes from the work by Jurov et al. (2021) who conducted a non-randomized experimental study with a crossover design to investigate the reproductive health impacts of progressively reducing EA by 50% for 14 days in well-trained and elite endurance male athletes. The results demonstrated a positive correlation between T levels and measured EA; as EA declined, so did T (9). The empirical evidence on the causal relationship between LEA and T has been growing over recent years, with studies such as one conducted by Dr. Iva Jurov and colleagues. In three progressive steps, their quasi-experimental study reduced EA (via increasing EEE and controlling EI) in well-trained and elite male endurance athletes. Participants had statistically significant T changes starting at the 50% EA reduction phase with a mean EA of 17.3 ± 5.0kcal/kg of FFM/day for 14 days (p < 0.037). Furthermore, T levels continued to significantly decline at 75% EA reduction phase with a mean EA of 8.83 ± 3.33 for ten days (p < 0.095) (10). Conversely, in another quasi-experimental study by Jurov et al. (2022b), endurance male athletes had their EA reduced by 25% by increasing EEE and controlling EI for 14 days. The mean EA was 22.4 ± 6.3kcal/kg of FFM/day. The results show no significant changes to T levels, potentially indicating that a greater EA reduction was required to induce change (11). Stenqvist et al. (2020) conducted four weeks of intensified endurance training designed to increase aerobic performance and determine the impact of T and T: cortisol ratio on well-trained male athletes. After the four weeks of intensified endurance training, the results showed that total T significantly increased by 8.1% (p=0.011) while free T (+4.1%, p=0.326), total T: cortisol ratio (+1.6%, p=0.789), and free T: cortisol ratio (-3.2%, p=0.556) did not have significant changes when compared to baseline (27). It is complex to determine the EA threshold defined by HPG axis suppression. Research on LEA and suppression of the HPG axis (i.e., T reduction) have demonstrated varied results based on athlete EA study design features (e.g., high EEE intensity or low EI duration); however, endurance athletes remain at the highest risk (18, 22, 26).

Bone Health The last pillar of the MAT is osteoporosis with or without bone stress injury (BSI). Impaired bone health is most common in athletes in sports that have low-impact loading patterns, such as cycling, swimming, or distance running. Bone mineral density (BMD) is the primary measurement method to evaluate overall bone health and risk for osteoporosis. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is the gold standard for assessing bone density, but quantitative computed tomography (QCT) is also emerging as an equally acceptable alternative. In outpatient or rehabilitation settings, frequency of DXA scans is recommended no sooner than every ten months to allow for detectable changes in bone mineral density (17). Risk factors for low BMD include LEA, low body weight (<85% of ideal body weight), hypogonadism, running mileage >30/week, and a history of stress fractures (22). In addition to BMD, other indicators of bone health include bone mineral content (BMC), markers of bone formation including β-carboxyl-terminal cross-linked telopeptide of type I collagen (β-CTX), bone alkaline phosphatase, and osteocalcin, and markers of bone resorption including amino-terminal propeptide of type-1 procollagen (P1NP), tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase, and carboxy-terminal collagen cross-links (4, 17). Studies will occasionally implement biomarkers such as Vitamin D and calcium to evaluate dietary intake and risk of BSI or osteoporosis. What is the prevalence of low BMD in athletes? Tam et al. (2018) evaluated the bone health and body composition of elite male Kenyan runners (n=15) compared to healthy individuals. The results showed that 40% of Kenyan runners have Z-scores indicating low bone mineral density in their lumbar spine for their respective age (z-score <−2.0). This study did not measure energy availability with bone mineral density (29). However, based on previous research, low bone mineral density may have LEA origins. Heikura et al. (2018) studied the BMD of middle- and long-distance runners and race walkers and found that athletes had an LEA (21kcal/kg of FFM/day) (7). Athletes with a moderate EA generally had better z-scores than the LEA athletes; however, the differences were not statistically significant. Similarly, Õnnik et al. (2022) found that high-level Kenyan male distance runners had an average EI of 1581kcal, and male controls had an average EI of 1454kcal per day. The male athletes did not show a statistically significant difference in BMD (p = 0.293) compared to the male control group, with only one runner (out of 20) at risk for osteoporosis (lumbar spine z-score <1.0) (23). Cyclists are at the highest risk for poor bone health due to chronic LEA, reduced osteogenic simulation, and low levels of impact or resistance (26). Keay et al. (2018) assessed the efficacy of a sport-specific EA questionnaire and clinical interview (SEAQ-I) in British professional cyclists at risk of developing RED-S. Based on the results of the SEAQ-I, 28% (n=14) were identified with LEA, and 44% of the cyclists had low lumbar spine BMD (z-score <-1.0) (p< 0.001). Also, cyclists with a history of lack of load-bearing sports or activities had the lowest BMD (p= 0.013) (13). This study demonstrates a clear association between LEA and reduced lumbar spine BMD in professional cyclists. In a randomized controlled trial, Keay et al. (2019) investigated the efficacy of an educational intervention with British competitive cyclists to improve energy availability and bone health. The researchers induced LEA by 25% (mean EA of 22.4 ± 6.3kcal/kg of FFM/day) for 14 days. Athletes who implemented nutritional strategies (provided by nutrition professionals) to improve EA and strength training strategies to improve skeletal loading saw lumbar spine BMD improvements. Mean vitamin D levels significantly improved from pre-season (90.6 ± 23.8 nmol/L) to post-season (103.6nmol/L; p=0.0001). Calcium, correct calcium, and alkaline phosphatase had no statistically significant changes between pre-season and post-season (12). Keay et al. have established the prevalence of LEA and poor bone health in cyclists and demonstrated nutrition education efficacy for BMD improvements. Noteworthy findings such as these help to raise awareness in the cycling community and can inform preventative or rehabilitative strategies.

BODY COMPOSITION Body composition is the distinction between fat mass and fat-free mass. Fat-free mass includes water, tissue, organs, bones, and muscle (e.g., skeletal muscle). Body composition control and maintenance are essential for an athlete’s health, performance, and mindset. Research measurements of body composition include weight, body mass index, body fat percentage, lean mass, and water content. According to Lundy et al. (2022), a body mass index <18.5 kg/m2 is a primary indicator of LEA; this suggests body composition changes in response to LEA (16). What is the impact of LEA on body composition? Stenqvist et al. (2020) implemented a four-week intensified endurance training designed to increase aerobic performance and elevate body composition’s impact on well-trained cyclists. The results did not show statistically significant changes in energy intake, body weight, fat mass, or fat-free mass. Body weight loss was potentially averted due to reduced resting metabolic rate as a protective mechanism (27). Whereas Stenqvist et al. (2020) focused on increasing EEE, Jurov et al. (2021) attempted to induce LEA via EI manipulation. Jurov et al. (2021) progressively reduced EA by 50% for 14 days in well-trained and elite endurance male athletes; the results showed no significant changes in body mass and fat-free mass (9). Regarding resistance training and LEA, Murphy and Koehler (2022) conducted a meta-analysis to quantify the discrepancy in lean mass accretion between interventions providing resistance training in an energy deficit and those without an energy deficit. The literature findings demonstrated lean mass gains impairment in athletes resistance training in an energy deficit compared to those training without an energy deficit (significantly, p = 0.02). The results also surmised that an energy deficit of as much as 500kcal/day could impede lean mass gains (21). Roth et al. (2023) evaluated the impact of a relatively high- versus moderate volume resistance training program on alterations in lean mass during caloric restriction in male weightlifters. The results showed that whole-body lean mass significantly declined in both groups (high and moderate volume groups) following six weeks of energy restriction. The high-volume group had an EA of 31.7 ± 2.8kcal/kg of FFM/day, and the moderate-volume group had an EA of 29.3 ± 4.2kcal/kg of FFM/day (25). Both studies demonstrate that muscle hypertrophy is unattainable in the presence of LEA. Furthermore, Murphy and Koehler (2020) found that three days of caloric restriction at an EA of 15kcal/kg of FFM/day in recreational weightlifters resulted in significant reductions in weight (p<0.01), fat mass (p<0.01), and lean mass (p<0.001). Also, the total mass loss was significant (p<0.01) when compared to a control group (EA of 40kcal/kg of FFM/day) (20). The results of studies focused on resistance training and caloric restriction hold applicability for athletes in sports that rely on lean mass gains while manipulating EI, such as bodybuilding (4).

CARDIORESPIRATORY ENDURANCE Cardiorespiratory endurance (CRE) is the ability of the lungs, heart, and blood vessels to deliver sufficient oxygen to cells to meet the physiological demands of exercise and physical activity (8). Evaluating maximal oxygen uptake or VO2max is a standard CRE measure. A VO2 max of 67.9 ± 7.4 mL/kg/min is categorized as a high fitness level (28). What is the impact of induced LEA on CRE performance outcomes? Jurov et al. (2021) investigated the endurance performance impact of progressively reducing energy availability by 50% for 14 days in well-trained and elite endurance male athletes. The researchers increased EEE to achieve a mean energy availability of 17.3 ± 5 kcal/kg of FFM/day. The results showed lowered EA reduced endurance performance, as indicated by respiratory compensation point (RC) and VO2max. Jurov et al. (2022b) reduced EA by 25% (by increasing EEE and controlling EI) in trained endurance male athletes and monitored for aerobic performance changes. The results showed that inducing LEA by 25% (mean EA of 22.4 ± 6.3kcal/kg of FFM/day) for 14 days reduced hemoglobin levels, indirectly impacting VO2max and aerobic performance (11). Beyond research conducted by Dr. Iva Jurov and colleagues, there is insufficient experimental research on LEA and CRE.

MUSCULAR STRENGTH AND ENDURANCE In recent years, few experimental studies have evaluated the impact of LEA on muscular strength, endurance, and athletic performance. Research on athletic performance and LEA has shown that endurance athletes with an EA of 17.3 ± 5 kcal/kg of FFM/day show no reductions in agility t-tests, power output, or countermovement jump results, indicating no association with EA (9). Also, Jurov et al. (2022b) found that a mean EA of 22.4 +/- 6.3kcal/kg of FFM/day in endurance male athletes for 14 days results in significant changes to explosive power (countermovement jump) but not agility t-tests (11). Furthermore, Jurov et al. (2022a) also reduced EA (via increasing exercise energy expenditure and controlling energy intake) in male endurance athletes to evaluate performance and muscular power impact. The results showed significant reductions in explosive power (measured via vertical jump height test) at a mean EA of 22.4, 17.3, and 8.82 kcal/kg of FFM/day. Based on these findings, athletes reach the LEA threshold after a long time in an energy-deficient state, such as ten to 14 days (10). However, Stenqvist et al. (2020) aimed to measure peak power in male cyclists after four weeks of intensified endurance training. The results showed that the cyclists significantly improved their peak power output (4.8%, p < 0.001) and functional threshold power (6.5%, p < 0.001) measured via stationary bike. Possibly, the EEE of the intervention was insufficient to induce LEA but instead induced the Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands (SAID) principle in the athletes (27). Regarding weightlifters, Murphy and Koehler (2022) studied whether energy deficiency impairs strength gains in response to resistance training. This research study was a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. The study findings showed that strength gains were comparable between resistance training groups in either an energy deficit or a balance state. These results demonstrated that low energy availability for prolonged periods (i.e., RED-S) did not impede strength output (21). There are a few studies that report bodybuilders with strength declines with estimations of EA <20 kcal/kg of FFM/day (4). The theory remains that inadequate energy intake will inevitably reduce muscular strength and output.

LOW ENERGY AVAILABILITY THRESHOLD To date, optimal EA levels and the threshold for LEA in male athletes are under investigation. However, many research studies are cross-sectional, only demonstrating a correlation between athletes and energy availability (e.g., LEA commonly found in endurance athletes). The scant number of current experimental studies often fail to induce LEA and thereby fail to establish clear LEA thresholds. To prevent LEA and subsequent conditions such as RED-S and MAT, athletes need to maintain their energy availability. Primarily, athletes need to ensure adequate EI and carefully manage their EEE. Current EA “zones” for female athletes are also applied to male athletes until experimental research can demonstrate a need for separate guidelines. EA >45kcal/kg of FFM/day supports body mass gain and maintains healthy physiological functions; 45kcal/kg of FFM/day is optimal for weight maintenance and healthy physiological functions; 30-45kcal/kg of FFM/day is considered suboptimal and at-risk for reduced physiological functions; and ≤30kcal/kg of FFM/day is considered low energy availability (1, 3, 4, 9, 10, 14, 17, 26). Research by Jurov and colleagues has demonstrated mixed results regarding performance outcomes, body composition, and bone health (9, 10, 11). Mean energy availability in those studies ranged between 17-22 kcal/kg of FFM/day (9, 11). Based on their research findings, Jurov and colleagues have proposed a range of 9-25kcal/kg of FFM/day (mean value of 17kcal/kg of FFM/day) for an LEA threshold (10). Regarding performance and body composition outcomes, Murphy and Koehler (2020) conducted a randomized, single-blind, repeated-measures crossover trial that showed three days of caloric restriction at an EA of 15kcal/kg of FFM/day induced considerable anabolic resistance to a heavy resistance training bout (20). In a case study by Langan-Evans et al. (2021), an EA of 20kcal/kg per FFM/day led to weight loss and fat loss without signs of MAT and RED-S. However, an EA of <10kcal/kg of FFM/day did result in signs and symptoms of MAT and RED-S, including disruptions to the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, resting metabolic rate (measured), and resting metabolic rate (ratio) (14). Additionally, some LEA thresholds may need to be sport-specific. For instance, Fagerberg et al. (2018) suggest an LEA threshold of 20-25kcal/kg of FFM/day for male bodybuilders with a lower body fat percentage (4). Research to establish EA zones and an LEA threshold for male athletes continues, and guidelines primarily still consider ≤30kcal/kg of FFM/day appropriate for male athletes. However, some researchers have also contested that male athletes can go lower before exhibiting signs and symptoms of MAT and RED-S.

RESEARCH GAPS There are sizable research gaps regarding LEA and RED-S. First, this literature was unable to address the impact of LEA on endocrine, metabolic, hematological, and gastrointestinal health due to insufficient research published in the past five years. Mountjoy et al. (2018) identified the following research gaps: (1) lack of practical tools to measure and detect LEA and RED-S, (2) lack of validated prevention interventions for RED-S, (3) RED-s in male athlete research, (4) health and performance consequences of RED-S research, and (5) lack of evidence-based guidelines for treatment and return-to-play for athletes with RED-S. Research gaps focused on male athletes with MAT are even more prominent (19).

Moreover, Fredericson et al. (2021) listed several research gaps that need scientific attention, including screening protocols to detect MAT in adolescent and young males, identification of MAT energetic and metabolic impact factors, prevalence of DEED in male athletes with MAT, evaluating the efficacy and effectiveness of clearance and return-to-play protocols, risk assessment for BSI and poor bone health, prevalence of MAT in military recruits, health interventions on the prevention and treatment of MAT, and lastly, cutoff values (or threshold) for LEA (5). Addressing these research gaps would enable sports and health practitioners to effectively prevent and treat LEA, RED-S, and MAT, ensuring athlete health and sports performance.

SUMMARY LEA is defined as a physiological state when there is inadequate energy to meet the demands placed on the body, often through physical activity, exercise, or sports (23). LEA can impact any athlete engaged in a sport with low energy intake or excessive energy expenditure. LEA is a precursor to the onset of both The Male Athlete Triad (MAT) and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S), two conditions that result in weakened physiological functions, with the former focused on reproductive and bone health decline (22).

Recent literature has shown mixed results on LEA’s impact on immunological health, metabolic markers, bone health, body composition, cardiorespiratory endurance, and muscular strength and endurance. There has been little evidence to connect LEA and endocrine, metabolic, hematological, and gastrointestinal health. However, a notable causal relationship exists between LEA and psychological health and reproductive health. Currently, there is still no defined low energy availability threshold specific to male athletes, however, EA zones from 15-25kcal/kg of FFM/day may be appropriate based on current literature (4, 20, 10, 18, 22, 26).

APPLICATION TO SPORT Healthy nutritional practices are essential to sports performance. Interdisciplinary sports performance teams must collaborate with nutrition professionals such as Registered Dietitians accredited by the Commission on Dietetic Registration to develop effective LEA prevention, screening, and intervention protocols. Preventative measures must prioritize energy availability, modify sporting culture to encourage energy intake, and mitigate barriers to calorie- and nutrient-dense foods in male athletes. Screening protocols must include EA evaluations based on dietary intake, exercise energy expenditure, and fat-free mass measured via DXA or bioelectrical impedance analysis. Male athletes with an EA ≤20-25kcal/kg of FFM/day must receive nutritional guidance to reduce health and performance impairments. Intervention protocols must be enacted when LEA is confirmed and should primarily focus on increasing energy intake, decreasing energy expenditure, and addressing other associated aspects such as psychological health. Athletes, coaches, and practitioners must raise LEA awareness, dispel energy consumption stigmas, and foster an environment where food and nutrition fuel peak performance.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was supported by the Pennsylvania Western University Department of Exercise, Health, and Sport Sciences. The author would like to thank Dr. Marc Federico and Dr. Brian Oddi for their guidance and feedback on the manuscript

- Burke, L., Deakin, V., Minehan, M. (2021). Clinical sports nutrition. (6th ed.). Sydney, Australia: McGraw Hill Education.

- Burke, L. M., Lundy, B., Fahrenholtz, I. L., & Melin, A. K. (2018). Pitfalls of conducting and interpreting estimates of energy availability in free-living athletes. International Journal of Sport Nutrition & Exercise Metabolism, 28(4), 350–363. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.2018-0142

- Egger, T., & Flueck, J. L. (2020). Energy availability in male and female elite wheelchair athletes over seven consecutive training days. Nutrients, 12(11). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113262

- Fagerberg, P. (2018). Negative consequences of LEA in natural male bodybuilding: A review. International Journal of Sport Nutrition & Exercise Metabolism, 28(4), 385–402. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.2016-0332

- Fredericson, M., Kussman, A., Misra, M., Barrack, M. T., De Souza, M. J., Kraus, E., Koltun, K. J., Williams, N. I., Joy, E., & Nattiv, A. (2021). The male athlete triad- A consensus statement from the female and male athlete triad coalition part II: Diagnosis, treatment, and return-to-play. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 31(4), 349–366. https://doi.org/10.1097/JSM.0000000000000948

- Hattori, S., Aikawa, Y., & Omi, N. (2022). Female athlete triad and male athlete triad syndrome induced by low energy availability: An animal model. Calcified Tissue International, 111(2), 116–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-022-00983-z

- Heikura, I. A., Uusitalo, A. L. T., Stellingwerff, T., Bergland, D., Mero, A. A., & Burke, L. M. (2018). Low energy availability is difficult to assess, but outcomes have a large impact on bone injury rates in elite distance athletes. International Journal of Sport Nutrition & Exercise Metabolism, 28(4), 403–411. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.2017-0313

- Hoeger, W. W., Hoeger, S. A., Hoeger, C. I., & Fawson, A. L. (2019). Lifetime physical fitness & wellness: A personalized program (15th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

- Jurov, I., Keay, N., & Rauter, S. (2021). Severe reduction of energy availability in controlled conditions causes poor endurance performance, impairs explosive power, and affects hormonal status in trained male endurance athletes. Applied Sciences (2076-3417), 11(18), 8618. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11188618

- Jurov, I., Keay, N., & Rauter, S. (2022a). Reducing energy availability in male endurance athletes: A randomized trial with a three-step energy reduction. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 19(1), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/15502783.2022.2065111

- Jurov, I., Keay, N., Spudić, D., & Rauter, S. (2022b). Inducing LEA in trained endurance male athletes results in poorer explosive power. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 122(2), 503–513. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.512365

- Keay, N., Francis, G., Entwistle, I., & Hind, K. (2019). Clinical evaluation of education relating to nutrition and skeletal loading in competitive male road cyclists at risk of RED-Ss (RED-S): 6-month randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 5, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000523

- Keay, N., Francis, G., & Hind, K. (2018). Low energy availability assessed by a sport-specific questionnaire and clinical interview indicative of bone health, endocrine profile and cycling performance in competitive male cyclists. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 4(1), e000424. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000424

- Langan-Evans, C., Germaine, M., Artukovic, M., Oxborough, D. L., Areta, J. L., Close, G. L., & Morton, J. P. (2021). The psychological and physiological consequences of LEA in a male combat sport athlete. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 53(4), 673–683. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000002519

- Langbein, R. K., Martin, D., Allen-Collinson, J., Crust, L., & Jackman, P. C. (2021). “I’d got self-destruction down to a fine art”: A qualitative exploration of relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S) in endurance athletes. Journal of Sports Sciences, 39(14), 1555–1564. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2021.1883312

- Lundy, B., Torstveit, M. K., Stenqvist, T. B., Burke, L. M., Garthe, I., Slater, G. J., Ritz, C., & Melin, A. K. (2022). Screening for low energy availability in male athletes: Attempted validation of LEAM-Q. Nutrients, 14(9), 1873. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14091873

- McGuire, A., Warrington, G., & Doyle, L. (2020). LEA in male athletes: A systematic review of incidence, associations, and effects. Translational Sports Medicine, 3(3), 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1002/tsm2.140

- Moris, J. M., Olendorff, S. A., Zajac, C. M., Fernandez-del-Valle, M., Webb, B. L., Zuercher, J. L., Smith, B. K., Tucker, K. R., & Guilford, B. L. (2022). Collegiate male athletes exhibit conditions of the male athlete triad. Applied Physiology, Nutrition & Metabolism, 47(3), 328–336. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2021-0512

- Mountjoy, M., Sundgot-Borgen, J., Burke, L., Ackerman, K. E., Blauwet, C., Constantini, N., Lebrun, C., Lundy, B., Melin, A., Meyer, N., Sherman, R., Tenforde, A. S., Torstveit, M. K., & Budgett, R. (2018). International olympic committee (IOC) consensus statement on relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): 2018 update. International Journal of Sport Nutrition & Exercise Metabolism, 28(4), 316–331. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.2018-0136

- Murphy, C., & Koehler, K. (2020). Caloric restriction induces anabolic resistance to resistance exercise. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 120(5), 1155–1164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-020-04354-0

- Murphy, C., & Koehler, K. (2022). Energy deficiency impairs resistance training gains in lean mass but not strength: A meta‐analysis and meta‐regression. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 32(1), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.14075

- Nattiv, A., De Souza, M. J., Koltun, K. J., Misra, M., Kussman, A., Williams, N. I., Barrack, M. T., Kraus, E., Joy, E., & Fredericson, M. (2021). The male athlete triad- A consensus statement from the female and male athlete triad coalition part 1: Definition and scientific basis. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 31(4), 335–348. https://doi.org/10.1097/JSM.0000000000000946

- Õnnik, L., Mooses, M., Suvi, S., Haile, D. W., Ojiambo, R., Lane, A. R., & Hackney, A. C. (2022). Prevalence of triad-red-s symptoms in high-level Kenyan male and female distance runners and corresponding control groups. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 122(1), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-021-04827-w

- Perelman, H., Schwartz, N., Yeoward, D. J., Quiñones, I. C., Murray, M. F., Dougherty, E. N., Townsel, R., Arthur, C. J., & Haedt, M. A. A. (2022). Reducing eating disorder risk among male athletes: A randomized controlled trial investigating the male athlete body project. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 55(2), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23665

- Roth, C., Schwiete, C., Happ, K., Rettenmaier, L., Schoenfeld, B. J., & Behringer, M. (2023). Resistance training volume does not influence lean mass preservation during energy restriction in trained males. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 33(1), 20–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.14237

- Schofield, K. L., Thorpe, H., & Sims, S. T. (2021). Where are all the men? LEA in male cyclists: A review. European Journal of Sport Science, 21(11), 1567–1578. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2020.1842510

- Stenqvist, T. B., Torstveit, M. K., Faber, J., & Melin, A. K. (2020). Impact of a 4-week intensified endurance training intervention on markers of RED-S (RED-S) and performance among well-trained male cyclists. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.512365

- Sui, X., LaMonte, M. J., & Blair, S. N. (2007). Cardiorespiratory fitness as a predictor of nonfatal cardiovascular events in asymptomatic women and men. American Journal of Epidemiology, 165(12), 1413–1423.

- Tam, N., Santos-Concejero, J., Tucker, R., Lamberts, R. P., & Micklesfield, L. K. (2018). Bone health in elite Kenyan runners. Journal of Sports Sciences, 36(4), 456–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2017.1313998

Order of passive and interactive sports consumption and its influences on consumer emotions and sports gambling

Qshequilla Parham Mitchell 2024-10-11T13:41:23-05:00 October 11th, 2024 | Research , Sports Studies |

Authors: Anthony Palomba 1 , Angela Zhang 2 , and David Hedlund 3

1 Department of Communication, Darden School of Business, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA 2 Department of Public Relations, Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication, The University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA 3 Department of Sport Management, Collings College of Professional Studies, St. John’s University, Queens, NY, USA

Anthony Palomba

100 Darden Blvd.

Charlottesville, VA, 22903

Anthony Palomba is an assistant professor of business administration at the Darden School of Business at the University of Virginia. He is fascinated by media, entertainment, and advertising firms. First, his research explores how and why audiences consume entertainment, and strives to understand how audience measurement can be enhanced to predict consumption patterns. Second, he studies how technological innovations influence competition among entertainment and media firms. Third, he is interested in incorporating machine learning and artificial intelligence tools to better understand consumer and firm behaviors.

Angela Zhang is an assistant professor in public relations. Her research interests span both corporate crisis communication and disaster risk communication in natural and manmade disasters. Her research primarily aims to understand how people process crisis and risk information and how we can communicate better during crises. For example, her work examines how linguistic cues in crisis messages affect people process crisis information, how and why risk information is propagated on social media, and how users communicate and cope on social media after crises. For corporate crisis communication, her research examines effectiveness of crisis prevention strategies such as CSR and DEI communication, as well as crisis response strategies.

Dr. Hedlund is an Associate Professor and the Chairperson of the Division of Sport Management, and he has more than twenty years of domestic and international experience in sport, esports, coaching, business and education. As an author, Dr. Hedlund is the lead editor of the first textbook ever published on esports titled Esports Business Management, and he has more than 30 additional journal, book chapter and related types of publications, in addition to approximately 50 research presentations. In recent years, Dr. Hedlund has acted as a journal, conference and book reviewer for sport, esports and business organizations from around the world, and he is an award-winning reviewer and editorial board member for the International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship.

This study explores how alternating between video game and television experiences influences consumer emotions and subsequent decision-making. Findings indicate that playing a video game after watching a video clip enhances positive emotions (H1 supported) and affects post-experiment betting scores based on pre-experiment gambling bets (H2 supported). Winning teams in video games and elevated positive emotions also positively influence post-experiment betting scores (H3 and H4 partially supported). The interaction effect shows that the sequence of media consumption (TV to video game) increases betting scores (H5 supported). The study contributes to understanding how appraisal tendency theory and mood management theory explain the impact of media consumption order on sports gambling decisions. Video games, as interactive stimuli, elevate consumer moods and influence betting behavior more than passive viewing. Practically, integrating video game and video clip data aids comprehensive audience measurement and targeted advertising strategies, advancing algorithmic forecasting in enhancing consumer engagement and decision-making.

Key Words: Mood management, Appraisal tendency theory, sports, gambling, video games

introduction.

The NFL is one of the most powerful media and entertainment brands in the marketplace, routinely curating legions of television and online video viewers for every annual season. In 2019, it averaged about 16.5 million viewers per game, roughly 33% above the 12.43 million viewing average for the top six non-sports programs (Porter, 2021). Additionally, over the last thirty years, the Madden NFL video game franchise has introduced generations to simulated immersive engagement. The legalization of sports gambling (Cason et al., 2020) has expanded how consumers can further engage with the NFL. NFL executives have discussed using mobile cell phones to aid sports fans in stadiums to make live bets throughout the course of a game (Martins, 2020). Audiences can watch the NFL and NFL game day content on the Xbox One, including up to date news and highlights from select NFL teams (Tuttle, 2016). Given these diverse modes of engagement, consumers often switch across a multitude of different activities. This frequent medium switching can significantly impact their moods and, subsequently, how they execute various tasks, including sports gambling. The phenomenon of media multitasking, where consumers engage with multiple forms of media simultaneously, complicates how they regulate their moods and make subsequent decisions (Deloitte, 2018). Younger consumers, in particular, are more inclined to switch between media than older consumers (Beuckels et al., 2021).

The increasingly diverse modes of engagement with the NFL, spanning from live game viewing and video game simulations to real-time betting, have led to a phenomenon of frequent media switching among consumers. This constant toggling between different platforms and activities can significantly impact their emotional states, subsequently influencing their decision-making processes, including those related to sports gambling. While previous research has examined task switching in general contexts (Yeykelis, Cummings, & Reeves, 2014) and the impact of media multitasking on advertising (Garaus, Wagner, & Back, 2017), the specific application of appraisal tendency theory to understand how these rapid emotional shifts induced by media switching affect sports gambling behaviors remains largely unexplored. Moreover, social media use while viewing television, a phenomenon that has grown in the last decade, has reconfigured the commodification of audiences, and has also created different markets to understand how consumers multi-task, and how to measure audience engagement (Kosterich & Napoli, 2016). Uniquely, social media may be used to track propensity to make season ticket purchases (Popp et al., 2023) among other sports consumption activities (Du et al., 2023). Recent studies have implicated the legalization of sports gambling as potentially increasing fandom and engagement among fans, and can further elevate communication across stakeholders involved in a sports event (Stadder & Naraine, 2020).

There is a gap in understanding, however, how consumer judgments and decisions are informed by emotions (Han, Lerner, & Keltner, 2007). Understanding this dynamic is critical for comprehending the evolution of fandom and identifying how sports teams can further engage fans. As consumers navigate between watching games, participating in video game simulations, and placing live bets, their engagement strategies and emotional states may significantly influence their decisions and loyalty. By examining these interactions, sports organizations can develop more effective methods to maintain and enhance fan engagement in an increasingly digital and interconnected world.

The implications of this study are broad and vast for academics along with sports and entertainment managers. The complex nature of media switching in sports consumption furthers our understanding of how affective disposition theory may be applied toward the multi-platform and multi-activity nature of modern sports engagement. It could lead to the development of a more nuanced understanding of how affective dispositions are formed and how they influence decision-making in this context. Microsoft (parent brand of Xbox console series) and the NFL have an agreement in which the NFL can provide fantasy football scores and updates on Xbox One consoles and allow fans to stream certain NFL games from their Xbox One consoles (Chansanchai, 2016). Additionally, Microsoft is able to trace not only what consumers play on Xbox One consoles, but also what TV or SVOD viewing apps fans engage to view content. Together, disparate information on video game play and video viewing can be combined to further identify trends in cross-platform sports consumption behavior and inferred consumer emotional states, which can help illuminate how consumer judgement surrounding sports gambling may be impacted.

NFL INDUSTRY

The National Football league has been a celebrated sports league in the United States and abroad over the last one hundred years. It draws the highest attendance per professional sports game in the United States, at about sixty-six thousand, and during its 2019 season, it hosted nearly sixteen million total viewers per game (Gough, 2021). The total revenue of all NFL teams was slightly over $15 billion in 2019, and average franchise value was just over $3 billion in 2020. Sports betting on Super bowls alone in Nevada accrued nearly $160 million in 2020 (Gough, 2021). While there are no clear figures regarding sports merchandise sales, NFL revenue by team in 2019 was led by the Dallas Cowboys ($980 million), New England Patriots ($630 million), NY Giants ($547 million) and Houston Texans ($530 million) through last place Las Vegas Raiders ($383 million) (Gough, 2020).

Aside from tickets, television revenue, and merchandise, the NFL has produced different avenues to engage fan bases. The league has recently embraced sports partnerships with Caesars Entertainment, Draft Kings and FanDuel. This allows these three external partners to engage in retail and online sports betting and engage with fans as well, using sports content from NFL media, as well as data, to market these experiences to fans (NFL, 2021). In fact, the NFL is expected to earn just over $2 billion annually from the sports gambling marketplace (Chiari, 2018). The NFL’s current TV media deals across CBS, ABC/ESPN, NBC, and Fox earn it just over $10 billion per season (Birnbaum, 2021). Arguably, one of the NFL’s highest profile merchandise revenue streams comes from its partnership with Electronic Arts (EA) to release an annual, updated version of Madden NFL , generating roughly $600 million annually for EA (Reyes, 2021). By embracing diverse engagement avenues, the NFL not only diversifies its revenue streams but also caters to the evolving preferences of modern sports consumers. This multi-faceted approach reflects the league’s recognition of the complex interplay between media consumption, mood, and fan behavior, ultimately enhancing the overall fan experience in an increasingly digital and interconnected world.

NFL FOOTBALL AS A VIDEO GAME EXPERIENCE: MADDEN NFL

There are few video games that possess the dominance and market monopolization as does the Madden NFL franchise. It exists as the only simulated NFL football video game available to consumers (Sarkar, 2020), and it is markedly popular among consumers. In fact, for the last twenty years, every Madden NFL video game installation has debuted as the top selling U.S. game in August each year (Wilson, 2022). The video game franchise itself has blossomed into its own celebrated video game season, as video game play expectedly rises during August in anticipation for the upcoming NFL season (Skiver, 2022). Madden NFL fans have been found to be more devoted and knowledgeable about the NFL. Additionally, they are less likely to miss viewing football games on Sundays, as 42% have stated they never miss a football game due to external activities. They are likely to attend at least one NFL game each annual season (IGN Staff, 2012).

Video gamers’ moods and subsequent judgment may be impacted by their own experiences. Video game play is an immersive experience, as the required technology helps to transport users into a digital world. The level of presence that is achieved can amplify mediated environment perceived quality, user effects, as well as overall experience (Tamborini & Bowman, 2010). Consumer familiarity with video game play may also influence how they experience presence (Lachlan & Krcmar, 2011). Consumers who view NFL games and play NFL video games may experience wins and loss outcomes in both passive and interactive manners. Sports video game play is motivated by possessing deep passion for the sport, gaming interest, entertainment value, competition, and identifying with the team or sport itself (Kim & Ross, 2006). Consumer emotions can be volatile during sports engagement, as winning and losing can impact overall game satisfaction (Yim & Byon, 2018). Emotions are tied to sports engagement in a primal manner, as consumers vicariously live through sports athletes and align themselves with sports teams, invoking a type of tribalism (Meir & Scott, 2007).

MOOD MANAGEMENT THEORY

Mood management theory concerns how consumers may manage their own moods through consumption of different mediums. Zillmann (1988) states that there are several traits that may impact whether a medium may repair or enhance a particular mood. First, there is the excitatory potential, or how exciting a message may be for consumers. Second, there is absorption potential, which examines how well a media message will be absorbed by an individual. Third, there is the semantic affinity, which relates to the connection from the current participant mood to a media message, which can moderate the impact of absorption potential. Finally, there is hedonic valence, in which pleasant messages can interrupt consumers’ bad moods (Zillmann, 1988). This study is focused on exploring how consumers’ gambling decisions are influenced by their experiences, both positive and negative, related to predicting scores between teams, and placing a bet on them. Specifically, it aims to investigate the impact of semantic affinity and the excitatory potential of stimuli involved in the process on consumer decision-making in gambling contexts.

Sports viewing or sports video game play can lead to evaluated states of physiological and psychological arousal, stirring hostile or expressive responses to game outcomes. Arousal has been found to be precipitated by aggressive or hostile states (Zillman, 1983), based on events during the game (Berkowitz, 1989). Hostility can be traced to the dissatisfaction with an outcome, or inability to attain a desired goal. Viewing violent sports competition can also heighten hostility and create greater inclinations toward aggressive behavior. Participants who had high identification with America and viewed an American boxer against a Russian boxer were found to have elevated blood pressure compared to those who had low identification with American (Branscombe & Wann, 1992). Additionally, spectators that have high team identification have higher levels of happiness compared to those with low team identification. The way a message is delivered can impact the effect of a message on consumers, as there are distinct characteristics related to each medium (Dijkstra, Buijtels & van Raaij, 2005).

Mood management is clearly influential as to how participants respond to video and video game play. Participants who may feel frustration may feel further frustration from viewing violent content (Zillmann & Johnson, 1973). One study by Bryant and Zillmann illustrated that participants who view violent sports did not experience mood repair (Donohew, Sypher, & Higgens,1988). Fulfillment of intrinsic needs can influence selection of video games with varying levels of participant demand (Reinecke et al., 2012). Television has been found to reduce boredom and stress among consumers (Bryant & Zillmann, 1984). In managing moods, this can also impact subsequent decision-making, sometimes surreptitiously and without awareness from participants.

APPRAISAL TENDENCY THEORY

Appraisal tendency theory considers how different types of emotions within similar valences (e.g., anger and fear) may impact judgement. There are two types of influences that may impact how consumers make judgments. Integral emotion is based on individual experiences that might preempt but be relevant to a subsequent decision. Differently, incidental emotion is due to conceivably irrelevant though impactful elements that can inform decision-making, which may include being influenced by traffic, watching television, or engaging in other non-relevant actions. These influences can carry over to the decision-making process (Schwarz & Clore, 1983; Bodenhausen, Kramer, & Susser, 1994). Moreover, consumers who are angry tend to perceive less risk from engaging in new situations (Han, Lerner, & Keltner, 2007).

Integral emotion is under examination in this study, as an outcome from a related medium stimulus can impact a subsequent decision that is likely informed by that stimulus. After finding that they have won in a video game, it may be that consumers are less inclined to bet against the team that they just lost against. This subjective pain(joy) based on the first stimulus may be stronger from playing a video game than from viewing a sports clip. Moreover, consumers may seek variety in consumption decisions when they are induced to a negative emotion (Chuang, Kung, & Sun, 2008). Therefore, subsequent decision-making may be informed by the order of passive and interactive media consumed by each individual.

MEDIUM MODALITY

Mediums that engage multiple senses are likely to lead to impactful communication with consumers (Jacoby, Hoyer & Zimmer, 1983). Television offers engagement through visual and auditory senses, while gaming stimulates both but creates an immersive experience, in which consumers are transported into a virtual world (Kuo, Hiler, & Lutz, 2017). Differently, consumers do not have control over passive mediums such as television, as the content is predetermined and is under the yolk of the sender, creating different delivery systems (Van Raaij, 1998). Video game play offers opportunities for players to speed up game play, based on gaming flexibility as well as how quickly a consumer can finish tasks. Video game play is positioned to evoke cognitive responses, through the speed of information dissemination, since the consumer possesses more control over the experience. Conflated with the demanded attention from video game play, consumers will likely have greater affective responses from video game play than from video viewing (Dijkstra, Buijtels, & van Raaij, 2005).

In consideration of this study, it follows that the simulated aspect of video game play can further influence decision-making. Consumers are inclined to experience improved decision-making and risk assessment through video game play (Reynaldo et al., 2020), as well as cognitive tasks (Chisholm & Kingstone, 2015). Video game play may also induce lowered physiological stress (Russoniello, O’Brien, & Parks, 2009), and emotional regulation (Villani et al., 2018). While there is scant research surrounding video game play simulations and making subsequent real-life decisions, it is ostensibly clear that video game play can heighten and sharpen decision-making skills as well as emotion regulation. Consumers who are attentive toward a simulated video game play experience may be influenced by its outcome in making a subsequent decision. This can include perceiving the winning team in the simulated game as likely to beat the same opposing team in a real-life match up.

H1: Consumers who play a video game (view a video clip) first will be more inclined to have lower (higher) positive emotions.

SPORTS GAMBLING

Recently, sports gambling has become legalized or recent legislation has been passed to make it legal in 50% of states in the United States (Rodenberg, 2021). While fans have placed bets on horse-racing and even major league sports, its legalization provides a lawful and safe forum for myriad fans to place bets on teams. However, since many gamblers may not invest time in understanding spreads and other esoteric metrics that gambling managers may use to measure likelihoods of outcomes, playing a Madden NFL game can serve consumers to anticipate potential outcomes in real life match ups. Madden NFL’s algorithms have been harvested in the past to predict Super Bowl outcomes. In fact, EA typically runs one hundred simulations to predict which team will win each year in the Super Bowl (Wiedey, 2020). Additionally, fans are also able to make wagers on major league baseball simulated video games (Cohen, 2020). Younger sports fans may be more inclined to play Madden NFL games as a way to simulate outcomes, and become more familiar with teams to anticipate actual game outcomes. Additionally, sports gamblers are betting on simulated sports, in which Madden NFL video games are simulated through the popular video game streaming site Twitch, and consumers are able to bet on the outcome (Campbell, 2021).

Previous studies have highlighted why consumers engage in sports gambling. One study found that consumers engage in sports gambling to seek out social interaction and relaxation through engagement with betting apps, though their effect on problematic gambling and non-problematic gambling varied across these dimensions (Whelan et al., 2021). Consumers may seek out consumer purchases as a way to blunt negative emotions, or may further satiate their positive mood by pursuing purchases that bring them joy. Video game play can engender excitatory potential, stimulating arousal levels and inspiring consumers in negative moods to make consumer purchases or execute notably different gambling bets. The heightened arousal levels experienced by consumers during video game play can create greater vacillation in subsequent decision-making, including sports gambling bets. Tangentially related to this, if a consumer is in a positive mood, this optimism may impact their inclination to bet more on a sports match up. Additionally, the order of engaging a passive medium versus an interactive medium is critical to analyze. Video game play can heighten immersion in content, and provide further confidence in a team. Consumers may be able to participate in high-scoring video game match ups. Additionally, consumers may be spurred to bet on characters with whom they have virtual relationships (Palomba, 2020). Finally, video game play can lead to experiencing dopamine release, leading to greater felt pleasure (Koepp et al., 1998). Together, these may lead consumers to have greater optimism for post-betting scores.

H2: Consumer pre-experiment bet scores will have an anchoring effect and still inform post-experiment bet scores.

H3: The team that wins in the video game will have a greater positive relationship with post experiment bet scores than the team with the highest score in the video clip.

H4: Consumers who experience strong positive (negative) emotions after viewing a video clip will positively (negatively) influence post-experiment bet scores.

H5: Consumption order and time will have an interaction effect that when consumption order is VG to TV, betting scores will decrease from pre-betting to post-betting (pre-betting will be higher than post-betting); when consumption order is TV to VG, betting scores will increase from pre-betting to post-betting (pre-betting will be lower than post-betting).

A 4×2 experiment was conducted here, in which participants were exposed to one of four different video clips, and one of two outcomes in a video game play match up. The New York Giants and Dallas Cowboys were the two teams that were selected for this experiment. Since this experiment took place in the mid-Atlantic region, it was believed that participants were less inclined to like either team. Moreover, these two teams have a storied and high-profile rivalry between them. For the video stimulus, participants were exposed to a randomized video clip highlighting a matchup between the NY Giants and Dallas Cowboys, in which one of four scenarios appeared: a) The NY Giants win by a wide margin (20 points), b) The NY Giants win by a slim margin (3 points), c) The Dallas Cowboys win by a slim margin (3 points), and d) The Dallas Cowboys win by a wide margin (20 points). Each video clip was about five minutes long. The video game stimulus involved playing a Madden NFL video game match up on an Xbox One video game console between the NY Giants and Dallas Cowboys. Participants were able to select which team they desired to play as and in which stadium to play in. The quarters in the Madden NFL game were kept at the default setting of six minutes each, ensuring participants experienced immersion but also maintained the experience to be similar to viewing the video clip.

Participants in the A condition (VG to TV) first played the video game followed by viewing the video clip, and participants in the B condition (TV to VG) first viewed the video clip followed by the video game play. as well as playing a Madden NFL session implicating both teams. After each condition, participants were asked to evaluate their current emotions. After the video clip, participants were asked to state the final score and which team won in the clip to ensure that they were paying attention to the clip itself. Moreover, after the video game condition, participants were asked to state which team they played as, the final score, as well as what sports stadium they played in.

To measure fandom, a scale from (Wann, 2002) was used here. It consisted of statements regarding self-assessment of fandom, including statements such as “I consider myself to be a football fan,” “My friends see me as a football fan,” and “I believe that following football is the most enjoyable form of entertainment.” It was measured on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) Likert scale.

To measure current emotions, a scale from Diener and Emmons (1984) was used here. The scale consisted of emotions statements including “joy,” “pleased,” “enjoyment,” “angry,” and other emotion statements. It was measured on a 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely much) Likert scale.

It was believed that the current emotions scale, though exhaustive, did not capture extreme aggression that may be felt by sports fans. An ancillary aggression scale (Sinclair 2005; Spielberger, 1999) was used here. The scale consisted of aggression statements including “I feel like yelling at somebody,” “I am mad,” and “I feel like banging on the table.” It was measured on a 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) Likert scale.

To measure for team identification, a scale by Naylor, Hedlund, and Dickson (2017) was used here. The scale consisted of statements including “I know a lot of information about my favorite National Football League team,” “I am very knowledgeable about my favorite National Football League team,” and “I am very familiar with my favorite National Football League team.” It was measured on a 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) Likert scale.

To measure for commitment to team, a scale by Hedlund, Biscaia, and Leal (2020) was used here. The scale consisted of statements including “I am a true fan of the team,” “I am very committed to the team,” and “I will attend my team’s games in the future.” It was measured on a 1 (not at all) to 5 (definitely) Likert scale.

To measure for brand loyalty toward Madden NFL, a scale by Yoo and Donthu (2001) was used here. The scale consisted of statements including “I consider myself to be loyal to Madden football,” “Madden football would be my first football video game choice,” and “The likely quality of Madden NFL is extremely high.” It was measured on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) Likert scale.

Descriptive analytics were run to break down video clip and video game play exposure to participants. After data-cleaning was executed, one hundred and thirteen participants (n=113) remained for analysis. 63.7% of participants were male. Additionally, across ethnicity, participants were Caucasian (58.4%), Asian-American (16.8%), African-American (8.8%), Hispanic (2.7%) and also identified as other races (13.3%). Among participants’ favorite NFL teams, they included the Washington Commodores (16.8%), New England Patriots (8.0%), and Philadelphia Eagles (8.0%). Less participants were fans of the New York Giants (4.4%) and Dallas Cowboys (1.8%). To gain a sense of faith participants had among each team, participants were asked to imagine making a bet between a pre bet on an imagined match up between the NY Giants and Dallas Cowboys. Participants on average placed the Dallas Cowboys (M=25.77, SD=9.102) past the NY Giants (M=20.67, SD=8.715) and bet roughly $14.37 on average.

Across all video clips, participants viewed the Giants winning by a lot (23.4%), Giants winning by a little (28.7%), Cowboys winning by a lot (25.5%), and Cowboys winning by a little (22.3%). Participants viewed the Giants winning 49.5% of the time and the Cowboys winning 50.5% of the time. In relation to video game difficulty level exposure, 51.3% of participants were exposed to pro-level difficulty (2/4 level of difficulty), and 48.7% were exposed to all-pro level difficulty (3/4 level of difficulty). This was done to ensure that Madden football players felt challenged and greater immersion during video game play (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975; Falstein, 2005; Nacke, 2012; Missura, 2015). 50.9% of participants played as the Dallas Cowboys, and 49.1% played as the NY Giants. In the video game itself, the Dallas Cowboys won 64% of the time, and the NY Giants won 36% of the time. Finally, participants won 74.8% of the time. Moreover, 58% of participants elected to play in NY Giants home stadium, MetLife Stadium, and 42% elected to play in AT&T Stadium, the Dallas Cowboys’ home stadium. Before analyses could be conducted, it was necessary to run factor analyses to reduce the amount of emotion statements necessary for analyses. For all factor analyses across pre-experimental mood, post video mood, and post video game mood, varimax rotations were run.

For post video emotions, the factor analysis had a KMO of .895 and the Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was statistically significant. The first factor loading had 12.717 eigenvalue and explained 48.913% of variance in the data. The first loading, violent, included I feel like kicking somebody (.919), I feel like hitting someone (.908), I feel like breaking things (.880), I feel like pounding somebody (.880), and I feel like yelling at somebody (.874) and had a Cronbach’s alpha score of .972. The second factor loading had an eigenvalue of 5.022 and explained 19.317% of variance in the data. This scale, entitled irritated, included frustrated (.865), annoyed (.835), angry (.820), depressed (.800), and sad (.768), and had a Cronbach’s alpha score of .928. The third factor loading had an eigenvalue of 2.311 and explained 8.890% of variance in the data. This scale, entitled positive, included pleased (.919), joy (.914), glad (.904), delighted (.900), and fun (.898) and had a Cronbach’s alpha score of .953.

For post video game emotions, a factor analysis was run. The KMO =.879 and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity was statistically significant. The first factor loading had an eigenvalue of 13.119, and it explained 50.458% of variance in the data set. The first factor loading, violent, included I feel like hitting someone (.866), I feel like breaking things (.858), I feel like banging on the table (.853), I feel like pounding somebody (.840) and I feel like kicking somebody (.840) with a Cronbach’s alpha score of .965. The second factor loading had an eigenvalue of 4.640 and explained 17.846% of variance in the data set. This scale, positive, included joy (.915), glad (.910), delighted (.897), pleased (.884), and fun (.860), and possessed a Cronbach’s alpha score of .952. The third factor loading had an eigenvalue of 1.783 and explained 6.858% of variance in the data set. This scale, irritated, included gloomy (.832), depressed (.798), sad (.747), anxious (.628), and angry (.531) and had a Cronbach’s alpha score of .905.

There was emotional variance across mediums (Table 1). Paired T-tests were run across an assortment of feelings here. For most of the emotions that were measured for in this experiment, participants generally felt better after playing the video game against viewing the clip itself across both conditions. For instance, in total, joy (M=4.38, SD=1.928), glad (M=4.45,

SD=1.785), and delighted (M=4.32, SD=1.904) all increased across all conditions after the video game play condition. Hypothesis 1 is supported here.

Emotion variance across mediums.

To test hypotheses 2-4, multiple linear regressions were running for predicting consumer post experiment score bets in table 2 and table 3. In table 2, Across both conditions, pre bet Giants score (β=.413, p<.001), pre bet Cowboys score (β=-.269, p<.012), and video Giants score (β=.225, p<.021) explained 34.6% of variance toward estimating Giants post experiment bet score. In the TV to VG condition, pre bet Giants score (β=.505, p<.003), pre bet Cowboys score (β=-.442, p<.008) explained 35.5% of variance toward estimating Giants post experiment bet score. In the VG to TV condition, pre bet Giants score (β=.430, p<.018) and Giants winning in VG (β=-.583, p<.024) explained 28.9% of variance toward estimating Giants post experiment bet score.

Consumer post bets – Giants.

In table 3, across both conditions, pre bet Cowboys score (β=.467, p<.001), Cowboys winning in video game (β= .342, p<.038), and video Cowboy score (β=.226, p<.024) explained 27.4% of variance toward estimating Giants post experiment bet score. In the TV to VG condition, pre bet Cowboys score (β=.394, p<.014), Cowboys winning in video game (β= .613, p<.029), Cowboys video score (β=.352, p<.020), Giants video game score (β=.470, p<.034), and feeling positive after viewing the video clip (β=.476, p<.020), explained 38.8% of variance toward estimating Giants post experiment bet score. In the VG to TV condition, Cowboys winning in the video game (β=.469, p<.035), Cowboys video score (β= .276, p<.047), Giants video game score (β=-.517, p<.021), Cowboys video game score (β=-.450, p<.022), and feeling violent after the video clip (β=-.583, p<.011) explained 46.2% of variance toward estimating Cowboys post experiment bet score. Together, these results supported hypothesis 2 and provided partial support for hypotheses 3 and 4.

Consumer post bets – Cowboys.

To answer the fifth hypothesis, a mixed between-within subjects analysis of variance was conducted to understand the effects of consumption order (TV to VG vs. VG to TV) and game results (NY giant wins a lot vs. Cowboy wins a lot) on participants’ sports betting scores on the two teams (NY Giants and Dallas Cowboys, respectively), across two time periods (pre- and post-experiment).

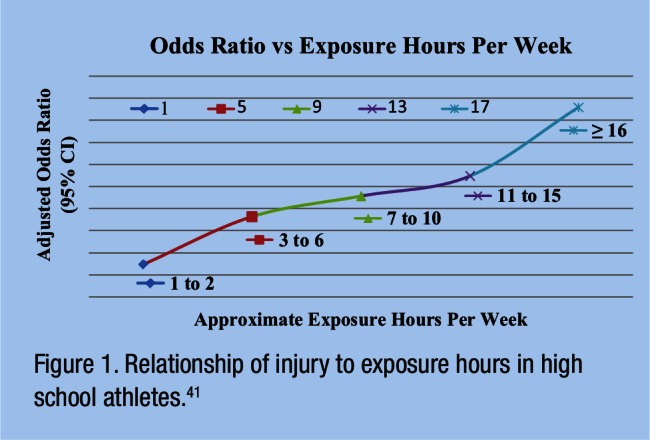

For betting scores on NY Giants, a significant interaction effect was found between time and order (Wilks’ Lambda = .89, F (1, 35) = 4.54, p =.04). Both pre and post-betting scores for those under the order condition TV to VG ( = 15.83, SD=5.79 and = 18.72, SD=8.10) scored lower than those under the VG TO TV conditions ( = 23.57, SD=9.67 and = 20.19, SD=8.54). Betting scores for NY Giant has increased for order TV to VG ( = 15.83, SD=5.79 to = 18.72, SD=8.10) but betting scores for order VG to TV has decreased ( = 23.57, SD=9.67 to = 20.19, SD=8.54). However, the main effects for time were not significant, nor were the interaction effects between time and game results, and between time, game results, and order (Figure 1). For betting scores on Dallas Cowboys, no significant main effects or interaction effects were found on any of the variables.

Pre-betting and post-betting scores.

This study worked to demonstrate how toggling between video game and television experiences could influence consumer emotions and inform subsequent decision-making. Consumers who played a video game after viewing a video clip were more inclined to feel positive (H1 supported). Pre-experiment gambling bets informed post experiment bet scores (H2 supported). There was some evidence that suggested winning teams in video games held a positive influence over post experiment bet scores (H3 partially supported) and that high levels of positive emotions also held a positive influence over post experiment bet scores (H4 partially supported). Finally, there was an interaction effect in which consumption order and time, in which betting scores will increase in the TV to VG condition (H5 supported). Together, the evidence illustrates how powerful the order of medium engagement is for consumers, and that these particular sequences can not only impact post-moods, but also decision-making among consumers.