Chinua Achebe

(1930-2013)

Who Was Chinua Achebe?

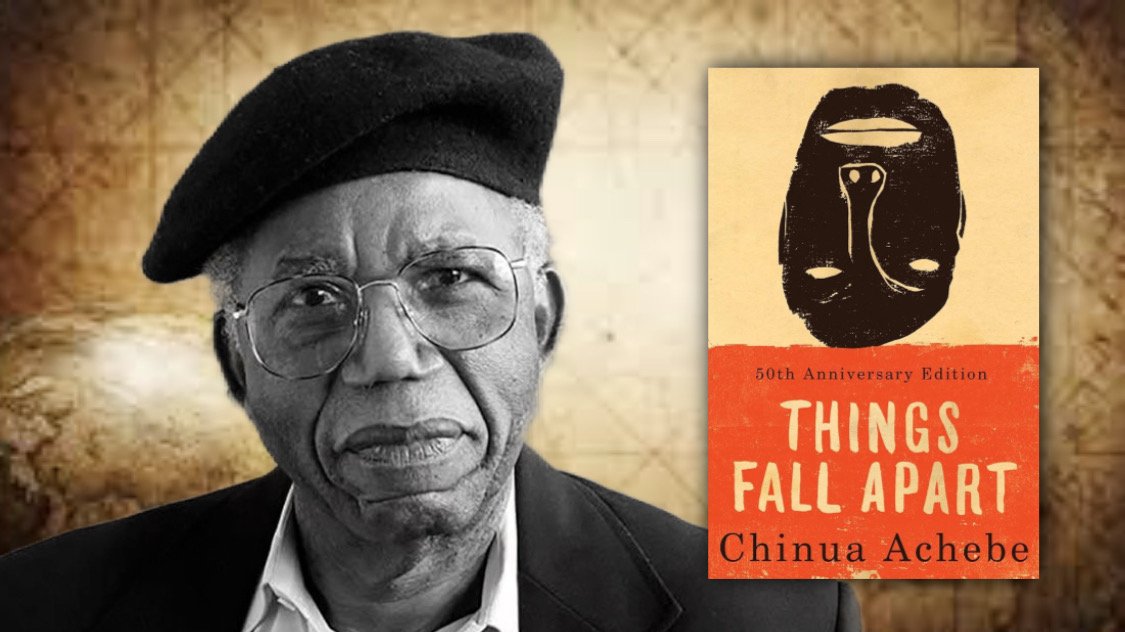

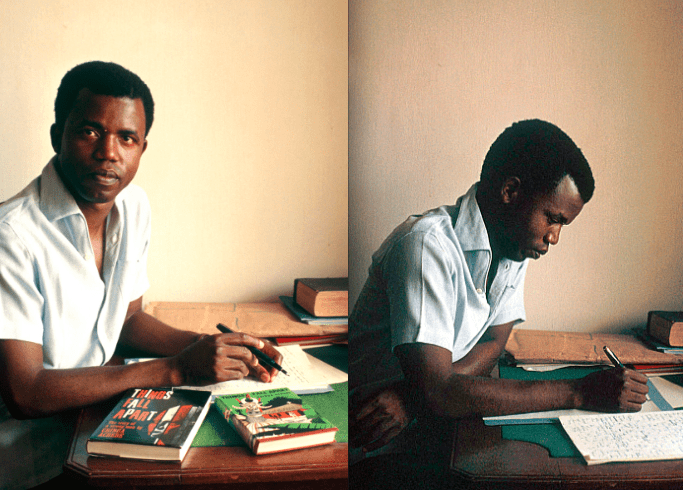

Chinua Achebe made a splash with the publication of his first novel, Things Fall Apart , in 1958. Renowned as one of the seminal works of African literature, it has since sold more than 20 million copies and been translated into more than 50 languages. Achebe followed with novels such as No Longer at Ease (1960), Arrow of God (1964) and Anthills of the Savannah (1987) , and served as a faculty member at renowned universities in the U.S. and Nigeria. He died on March 21, 2013, at age 82, in Boston, Massachusetts.

Early Years and Career

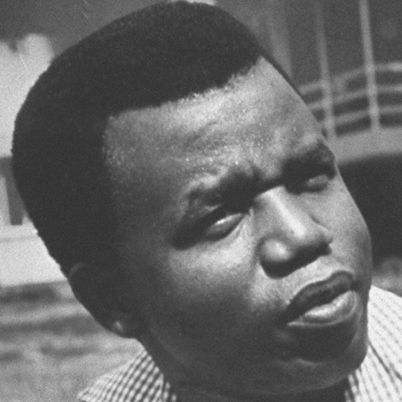

Famed writer and educator Chinua Achebe was born Albert Chinualumogu Achebe on November 16, 1930, in the Igbo town of Ogidi in eastern Nigeria. After becoming educated in English at University College (now the University of Ibadan) and a subsequent teaching stint, Achebe joined the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation in 1961 as director of external broadcasting. He would serve in that role until 1966.

'Things Fall Apart'

In 1958, Achebe published his first novel: Things Fall Apart . The groundbreaking novel centers on the clash between native African culture and the influence of white Christian missionaries and the colonial government in Nigeria. An unflinching look at the discord, the book was a startling success and became required reading in many schools across the world.

'No Longer at Ease' and Teaching Positions

The 1960s proved to be a productive period for Achebe. In 1961, he married Christie Chinwe Okoli, with whom he would go on to have four children, and it was during this decade he wrote the follow-up novels to Things Fall Apart : No Longer at Ease (1960) and Arrow of God (1964), as well as A Man of the People (1966). All address the issue of traditional ways of life coming into conflict with new, often colonial, points of view.

In 1967, Achebe and poet Christopher Okigbo co-founded the Citadel Press, intended to serve as an outlet for a new kind of African-oriented children's books. Okigbo was killed shortly afterward in the Nigerian civil war, and two years later, Achebe toured the United States with fellow writers Gabriel Okara and Cyprian Ekwensi to raise awareness of the conflict back home, giving lectures at various universities.

Through the 1970s, Achebe served in faculty positions at the University of Massachusetts, the University of Connecticut and the University of Nigeria. During this time, he also served as director of two Nigerian publishing houses, Heinemann Educational Books Ltd. and Nwankwo-Ifejika Ltd.

On the writing front, Achebe remained highly productive in the early part of the decade, publishing several collections of short stories and a children's book: How the Leopard Got His Claws (1972). Also released around this time were the poetry collection Beware, Soul Brother (1971) and Achebe's first book of essays, Morning Yet on Creation Day (1975).

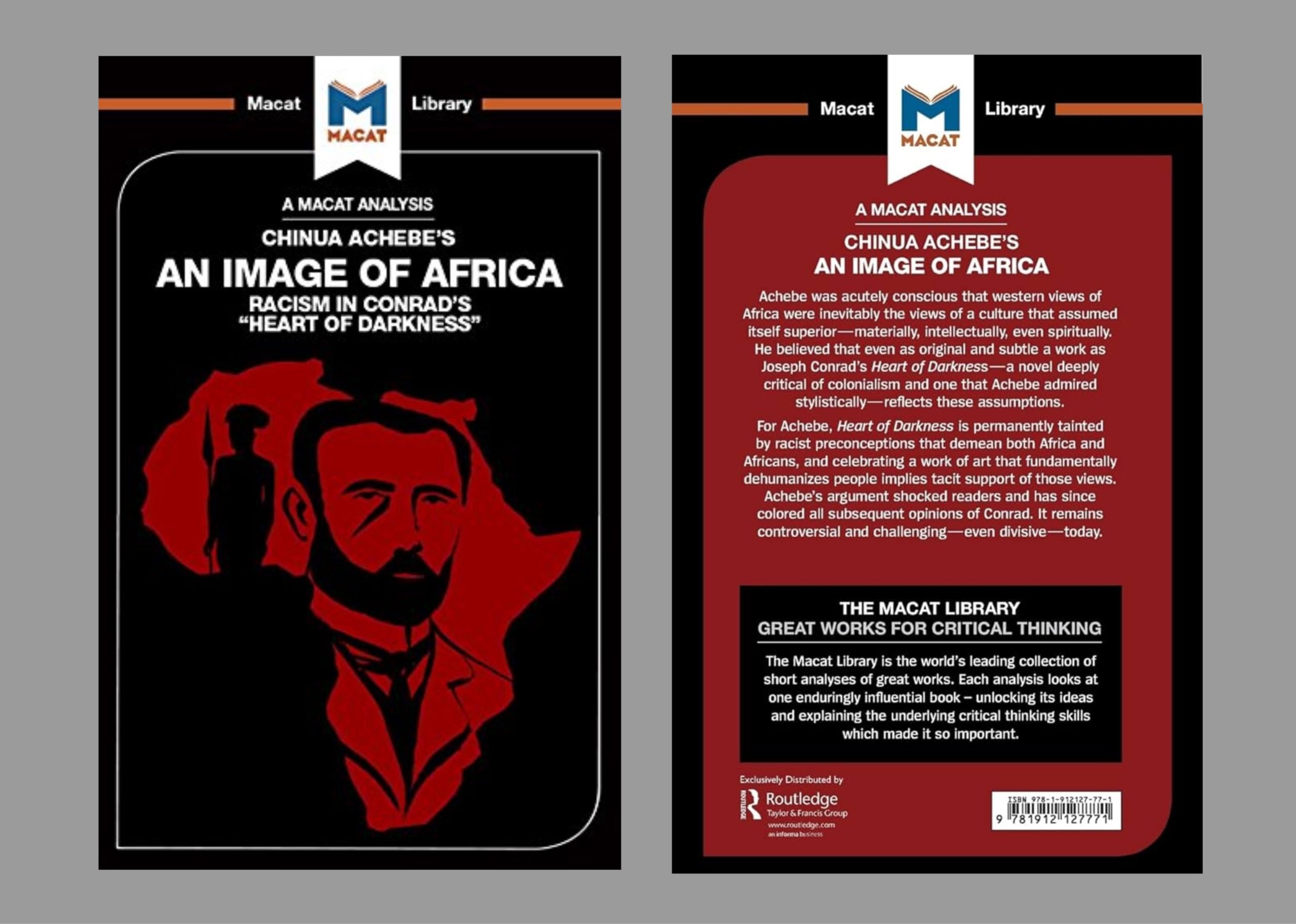

In 1975, Achebe delivered a lecture at UMass titled "An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's Heart of Darkness ," in which he asserted that Joseph Conrad's famous novel dehumanizes Africans. When published in essay form, it went on to become a seminal postcolonial African work.

Later Work and Accolades

The year 1987 brought the release of Achebe's Anthills of the Savannah. His first novel in more than 20 years, it was shortlisted for the Booker McConnell Prize. The following year, he published Hopes and Impediments .

The 1990s began with tragedy: Achebe was in a car accident in Nigeria that left him paralyzed from the waist down and would confine him to a wheelchair for the rest of his life. Soon after, he moved to the United States and taught at Bard College, just north of New York City, where he remained for 15 years. In 2009, Achebe left Bard to join the faculty of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, as the David and Marianna Fisher University professor and professor of Africana studies.

Achebe won several awards over the course of his writing career, including the Man Booker International Prize (2007) and the Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize (2010). Additionally, he received honorary degrees from more than 30 universities around the world.

Achebe died on March 21, 2013, at the age of 82, in Boston, Massachusetts.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Chinua Achebe

- Birth Year: 1930

- Birth date: November 16, 1930

- Birth City: Ogidi, Anambra

- Birth Country: Nigeria

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Chinua Achebe was a Nigerian novelist and author of 'Things Fall Apart,' a work that in part led to his being called the 'patriarch of the African novel.'

- Education and Academia

- Fiction and Poetry

- Astrological Sign: Scorpio

- University of Ibadan

- Nacionalities

- Death Year: 2013

- Death date: March 21, 2013

- Death State: Massachusetts

- Death City: Boston

- Death Country: United States

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Chinua Achebe Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/writer/chinua-achebe

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: January 19, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- Art is man's constant effort to create for himself a different order of reality from that which is given to him.

- When suffering knocks at your door and you say there is no seat for him, he tells you not to worry because he has brought his own stool.

- One of the truest tests of integrity is its blunt refusal to be compromised.

Famous Authors & Writers

9 Surprising Facts About Truman Capote

William Shakespeare

How Did Shakespeare Die?

Meet Stand-Up Comedy Pioneer Charles Farrar Browne

Francis Scott Key

Christine de Pisan

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

10 Famous Langston Hughes Poems

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

10 Black Authors Who Shaped Literary History

The True Story of Feud:Capote vs. The Swans

Biography of Chinua Achebe, Author of "Things Fall Apart"

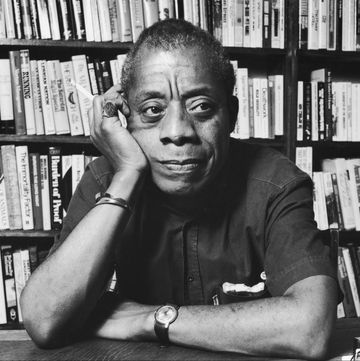

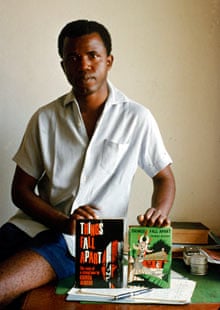

Eamonn McCabe / Getty Images

- Authors & Texts

- Top Picks Lists

- Study Guides

- Best Sellers

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

- M.A., Anthropology, University of Iowa

- B.Ed., Illinois State University

Chinua Achebe (born Albert Chinualumogu Achebe; November 16, 1930–March 21, 2013) was a Nigerian writer described by Nelson Mandela as one "in whose company the prison walls fell down." He is best known for his African trilogy of novels documenting the ill effects of British colonialism in Nigeria, the most famous of which is " Things Fall Apart ."

Fast Facts: Chinua Achebe

- Occupation : Author and professor

- Born : November 16, 1930 in Ogidi, Nigeria

- Died : March 21, 2013 in Boston, Massachusetts

- Education : University of Ibadan

- Selected Publications : Things Fall Apart , No Longer at Ease , Arrow of God

- Key Accomplishment : Man Booker International Prize (2007)

- Famous Quote : "There is no story that is not true."

Early Years

Chinua Achebe was born in Ogidi, an Igbo village in Anambra, southern Nigeria . He was the fifth of six children born to Isaiah and Janet Achebe, who were among the first converts to Protestantism in the region. Isaiah worked for a missionary teacher in various parts of Nigeria before returning to his village.

Achebe's name means "May God Fight on My Behalf" in Igbo. He later famously dropped his first name, explaining in an essay that at least he had one thing in common with Queen Victoria: they had both "lost [their] Albert."

Achebe grew up as a Christian, but many of his relatives still practiced their ancestral polytheistic faith. His earliest education took place at a local school where children were forbidden to speak Igbo and encouraged to disown their parents' religion.

At 14, Achebe was accepted into an elite boarding school, the Government College at Umuahia. One of his classmates was the poet Christopher Okigbo, who became Achebe's lifelong friend.

In 1948, Achebe won a scholarship to the University of Ibadan to study medicine, but after a year he changed his major to writing. At university, he studied English literature and language, history, and theology.

Becoming a Writer

At Ibadan, Achebe's professors were all Europeans, and he read British classics including Shakespeare, Milton, Defoe, Conrad, Coleridge, Keats, and Tennyson. But the book that inspired his writing career was British-Irish Joyce Cary's 1939 novel set in southern Nigeria, called "Mister Johnson."

The portrayal of Nigerians in "Mister Johnson" was so one-sided, so racist and painful, that it awoke in Achebe a realization of the power of colonialism over him personally. He admitted to having an early fondness for Joseph Conrad 's writing, but came to call Conrad a "bloody racist" and said that " The Heart of Darkness " was "an offensive and deplorable book."

This awakening inspired Achebe to begin writing his classic, "Things Fall Apart," with a title from the poem by William Butler Yeats , and a story set in the 19th century. The novel follows Okwonko, a traditional Igbo man, and his futile struggles with the power of colonialism and the blindness of its administrators.

Work and Family

Achebe graduated from the University of Ibadan in 1953 and soon became a scriptwriter for the Nigerian Broadcasting Service, eventually becoming the head programmer for the discussion series. In 1956, he visited London for the first time to take a training course with the BBC. On returning, he moved to Enugu and edited and produced stories for the NBS. In his spare time, he worked on "Things Fall Apart." The novel was published in 1958.

His second book, "No Longer at Ease," published in 1960, is set in the last decade before Nigeria achieved independence . Its protagonist is Okwonko's grandson, who learns to fit into British colonial society (including political corruption, which causes his downfall).

In 1961, Chinua Achebe met and married Christiana Chinwe Okoli, and they eventually had four children: daughters Chinelo and Nwando, and twin sons Ikechukwu and Chidi. The third book in the African trilogy, "Arrow of God," was published in 1964. It describes an Igbo priest Ezeulu, who sends his son to be educated by Christian missionaries, where the son is converted to colonialism, attacking Nigerian religion and culture.

Biafra and "A Man of the People"

Achebe published his fourth novel, "A Man of the People," in 1966. The novel tells the story of the widespread corruption of Nigerian politicians and ends in a military coup.

As an ethnic Igbo, Achebe was a staunch supporter of Biafra's unsuccessful attempt to secede from Nigeria in 1967. The events that occurred and led to the three-year-long civil war that followed that attempt closely paralleled what Achebe had described in "A Man of the People," so closely that he was accused of being a conspirator.

During the conflict, thirty thousand Igbo were massacred by government-backed troops. Achebe's house was bombed and his friend Christopher Okigbo was killed. Achebe and his family went into hiding in Biafra, then fled to Britain for the duration of the war.

Academic Career and Later Publications

Achebe and his family moved back to Nigeria after the civil war ended in 1970. Achebe became a research fellow at the University of Nigeria at Nsukke, where he founded "Okike," an important journal for African creative writing.

From 1972–1976, Achebe held a visiting professorship in African literature at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. After that, he returned again to teach at the University of Nigeria. He became chair of the Association of Nigerian Writers and edited "Uwa ndi Igbo," a journal of Igbo life and culture. He was relatively active in opposition politics, as well: he was elected deputy national president of the People's Redemption Party and published a political pamphlet called "The Trouble with Nigeria" in 1983.

Although he wrote many essays and kept involved with the writing community, Achebe did not write another book until 1988's "Anthills in the Savannah," about three former school friends who become a military dictator, an editor of the leading newspaper, and the minister of information.

In 1990, Achebe was involved in a car crash in Nigeria, which damaged his spine so badly he was paralyzed from the waist down. Bard College in New York offered him a job teaching and the facilities to make that possible, and he taught there from 1991–2009. In 2009, Achebe became a professor of African studies at Brown University.

Achebe continued to travel and lecture around the world. In 2012, he published the essay "There Was a Country: A Personal History of Biafra."

Death and Legacy

Achebe died in Boston, Massachusetts, on March 21, 2013, after a brief illness. He is credited with changing the face of world literature by presenting the effects of European colonization from the point of view of Africans. He specifically wrote in English, a choice that received some criticism, but his intent was to speak to the whole world about the real problems that the influence of Western missionaries and colonialists created in Africa.

Achebe won the Man Booker International Prize for his life's work in 2007 and received more than 30 honorary doctorates. He remained critical of the corruption of Nigerian politicians, condemning those that stole or squandered the nation's oil reserves. In addition to his own literary success, he was a passionate and active supporter of African writers.

- Arana, R. Victoria, and Chinua Achebe. " The Epic Imagination: A Conversation with Chinua Achebe at Annandale-on-Hudson, October 31, 1998 ." Callaloo, vol. 25, no. 2, Spring 2002, pp. 505–26.

- Ezenwa-Ohaeto. Chinua Achebe: A Biography . Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997.

- Garner, Dwight. " Bearing Witness, with Words. " The New York Times, March 23, 2013.

- Kandell, Jonathan. " Chinua Achebe, African Literary Titan, Dies at 82 ." The New York Times, March 23, 2013.

- McCrummen, Stephanie, and Adam Bernstein. " Chinua Achebe, Groundbreaking Nigerian Novelist, Dies at 82 ." The Washington Post, March 22, 2013.

- Snyder, Carey. " The Possibilities and Pitfalls of Ethnographic Readings: Narrative Complexity in 'Things Fall Appart' ." College Literature , vol. 35 no. 2, 2008, p. 154-174.

- 'Things Fall Apart' Overview

- 'Things Fall Apart' Discussion Questions and Study Guide

- 'Things Fall Apart' Themes, Symbols, and Literary Devices

- 'Things Fall Apart' Characters

- 'Things Fall Apart' Quotes

- 'Things Fall Apart' Summary

- Top 10 Books for High School Seniors

- West African Pidgin English (WAPE)

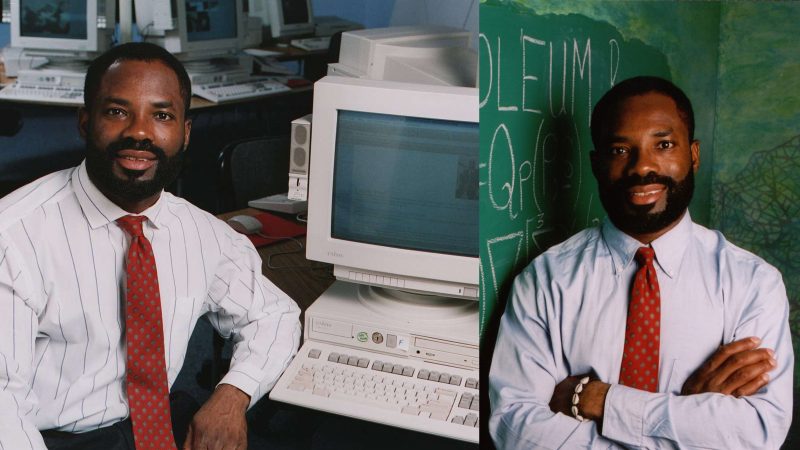

- Philip Emeagwali, Nigerian American Computer Pioneer

- What You Should Know About Nigeria

- Nigerian English

- Biography of Philip Roth, American Novelist, Short-Story Writer

- 10th (or 11th) Grade Reading List

- The Benin Empire

- James Meredith: First Black Student to Attend Ole Miss

- 5 Famous Classic Italian Writers

Chinua Achebe

- Non-Fiction

- Penguin Group (UK)

- The Wylie Agency (UK) Ltd

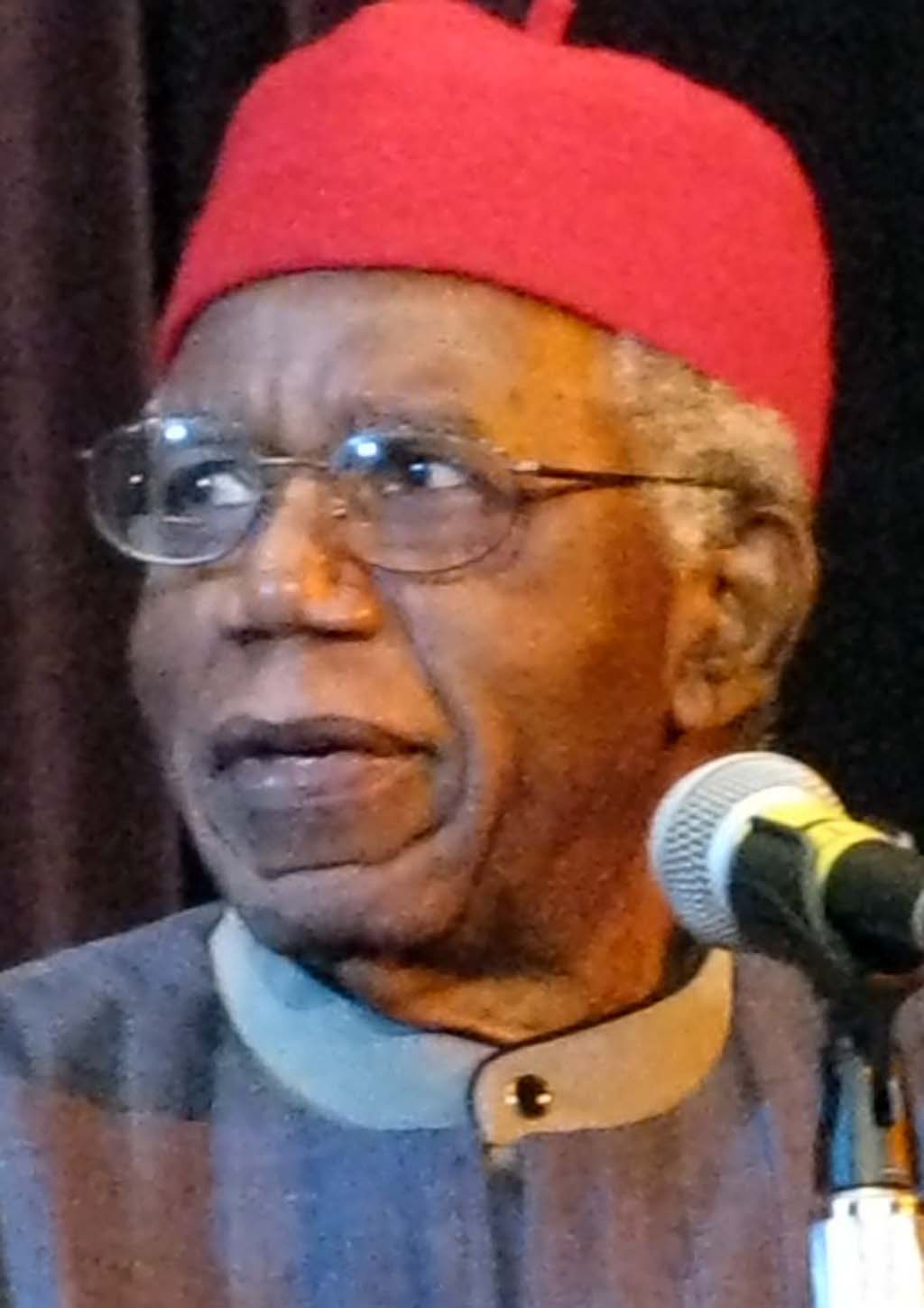

Chinua Achebe was born in Nigeria in 1930.

He was raised in the large village of Ogidi, one of the first centres of Anglican missionary work in Eastern Nigeria, and is a graduate of University College, Ibadan.

His early career in radio ended abruptly in 1966, when he left his post as Director of External Broadcasting in Nigeria during the national upheaval that led to the Biafran War. Achebe joined the Biafran Ministry of Information and represented Biafra on various diplomatic and fund-raising missions. He was appointed Senior Research Fellow at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, and began lecturing widely abroad. For more than 15 years he was the Carles P. Stevenson Jr Professor of Languages and Literature at Bard College; he then became the David and Marianna Fisher University Professor and Professor of Africana Studies at Brown University.

Chinua Achebe wrote more than 20 books - novels, short stories, essays and collections of poetry - including Things Fall Apart (1958), which has sold more than 10 million copies worldwide and been translated into more than 50 languages; Arrow of God (1964); Beware, Soul Brother and Other Poems (1971), winner of the Commonwealth Poetry Prize; Anthills of the Savannah (1987), which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize for Fiction; Hopes and Impediments: Selected Essays (1988); and Home and Exile (2000).

Chinua Achebe received numerous honours from around the world, including the Honorary Fellowship of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, as well as honorary doctorates from more than 30 colleges and universities. He was also the recipient of Nigeria's highest award for intellectual achievement, the Nigerian National Merit Award. In 2007, he won the Man Booker International Prize. He died on 22nd March 2013.

Bibliography

Sign up to the newsletter.

- Things Fall Apart

Chinua Achebe

- Literature Notes

- Chinua Achebe Biography

- Book Summary

- About Things Fall Apart

- Character List

- Summary and Analysis

- Part 1: Chapter 1

- Part 1: Chapter 2

- Part 1: Chapter 3

- Part 1: Chapter 4

- Part 1: Chapter 5

- Part 1: Chapter 6

- Part 1: Chapter 7

- Part 1: Chapter 8

- Part 1: Chapter 9

- Part 1: Chapter 10

- Part 1: Chapter 11

- Part 1: Chapter 12

- Part 1: Chapter 13

- Part 2: Chapter 14

- Part 2: Chapter 15

- Part 2: Chapter 16

- Part 2: Chapter 17

- Part 2: Chapter 18

- Part 2: Chapter 19

- Part 3: Chapter 20

- Part 3: Chapter 21

- Part 3: Chapter 22

- Part 3: Chapter 23

- Part 3: Chapter 24

- Part 3: Chapter 25

- Character Analysis

- Reverend James Smith

- Character Map

- Critical Essays

- Major Themes in Things Fall Apart

- Use of Language in Things Fall Apart

- Full Glossary for Things Fall Apart

- Essay Questions

- Cite this Literature Note

Early Years

Chinua Achebe (pronounced Chee- noo-ah Ah- chay -bay) is considered by many critics and teachers to be the most influential African writer of his generation. His writings, including the novel Things Fall Apart , have introduced readers throughout the world to creative uses of language and form, as well as to factual inside accounts of modern African life and history. Not only through his literary contributions but also through his championing of bold objectives for Nigeria and Africa, Achebe has helped reshape the perception of African history, culture, and place in world affairs.

The first novel of Achebe's, Things Fall Apart , is recognized as a literary classic and is taught and read everywhere in the English-speaking world. The novel has been translated into at least forty-five languages and has sold several million copies. A year after publication, the book won the Margaret Wong Memorial Prize, a major literary award.

Achebe was born in the Igbo (formerly spelled Ibo ) town of Ogidi in eastern Nigeria on November 16, 1930, the fifth child of Isaiah Okafor Achebe and Janet Iloegbunam Achebe. His father was an instructor in Christian catechism for the Church Missionary Society. Nigeria was a British colony during Achebe's early years, and educated English-speaking families like the Achebes occupied a privileged position in the Nigerian power structure. His parents even named him Albert, after Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria of Great Britain. (Achebe himself chose his Igbo name when he was in college.)

Achebe attended the Church Missionary Society's school where the primary language of instruction for the first two years was Igbo. At about eight, he began learning English. His relatively late introduction to English allowed Achebe to develop a sense of cultural pride and an appreciation of his native tongue — values that may not have been cultivated had he been raised and taught exclusively in English. Achebe's home fostered his understanding of both cultures: He read books in English in his father's library, and he spent hours listening to his mother and sister tell traditional Igbo stories.

At fourteen, Achebe was selected to attend the Government College in Umuahia, the equivalent of a university preparatory school and considered the best in West Africa. Achebe excelled at his studies, and after graduating at eighteen, he was accepted to study medicine at the new University College at Ibadan, a member college of London University at the time. The demand for educated Nigerians in the government was heightened because Nigeria was preparing for self-rule and independence. Only with a college degree was a Nigerian likely to enter the higher ranks of the civil service.

The growing nationalism in Nigeria was not lost on Achebe. At the university, he dropped his English name "Albert" in favor of the Igbo name "Chinua," short for Chinualumogo. Just as Igbo names in Things Fall Apart have literal meanings, Chinualumogo is translated as "My spirit come fight for me."

At University College, Achebe switched his studies to liberal arts, including history, religion, and English. His first published stories appeared in the student publication the University Herald . These stories have been reprinted in the collection Girls at War and Other Stories , which was published in 1972. Of his student writings, only a few are significantly relative to his more mature works; short stories such as "Marriage is a Private Affair" and "Dead Man's Path" explore the conflicts that arise when Western culture meets African society.

Career Highlights

After graduating with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1953, Achebe joined the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation as a producer of radio talks. In 1956, he went to London to attend the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) Staff School. While in London, he submitted the manuscript for Things Fall Apart to a publisher, with the encouragement and support of one of his BBC instructors, a writer and literary critic. The novel was published in 1958 by Heinemann, a publishing firm that began a long relationship with Achebe and his work. Fame came almost instantly. Achebe has said that he never experienced the life of a struggling writer.

Upon returning to Nigeria, Achebe rose rapidly within the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation. As founder and director of the Voice of Nigeria in 1961, Achebe and his colleagues aimed at developing more national identity and unity through radio programs that highlighted Nigerian affairs and culture.

Political Problems

Turmoil in Nigeria from 1966 to 1972 was matched by turmoil for Achebe. In 1966, young Igbo officers in the Nigerian army staged a coup d'ètat. Six months later, another coup by non-Igbo officers overthrew the Igbo-led government. The new government targeted Achebe for persecution, knowing that his views were unsympathetic to the new regime. Achebe fled to Nsukka in eastern Nigeria, which is predominantly Igbo-speaking, and he became a senior research fellow at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. In 1967, the eastern part of Nigeria declared independence as the nation of Biafra. This incident triggered thirty months of civil war that ended only when Biafra was defeated. Achebe then fled to Europe and America, where he wrote and talked about Biafran affairs.

Later Writing

Like many other African writers, Achebe believes that artistic and literary works must deal primarily with the problems of society. He has said that "art is, and always was, at the service of man" rather than an end in itself, accountable to no one. He believes that "any good story, any good novel, should have a message, should have a purpose."

Continuing his relationship with Heinemann, Achebe published four other novels: No Longer at Ease (the 1960 sequel to Things Fall Apart ), Arrow of God (1964), A Man of the People (1966), and Anthills of the Savannah (1987). He also wrote and published several children's books that express his basic views in forms and language understandable to young readers.

In his later books, Achebe confronts the problems faced by Nigeria and other newly independent African nations. He blames the nation's problems on the lack of leadership in Nigeria since its independence. In 1983, he published The Trouble with Nigeria , a critique of corrupt politicians in his country. Achebe has also published two collections of short stories and three collections of essays. He is the founding editor of Heinemann's African Writers series; the founder and publisher of Uwa Ndi Igbo : A Bilingual Journal of Igbo Life and Arts ; and the editor of the magazine Okike , Nigeria's leading journal of new writing.

Teaching and Literary Awards

In addition to his writing career, Achebe maintained an active teaching career. In 1972, he was appointed to a three-year visiting professorship at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and, in 1975, to a one-year visiting professorship at the University of Connecticut. In 1976, with matters sufficiently calm in Nigeria, he returned as professor of English at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, with which he had been affiliated since 1966. In 1990, he became the Charles P. Stevenson, Jr., professor of literature at Bard College, Annandale, New York.

Achebe received many awards from academic and cultural institutions around the world. In 1959, he won the Margaret Wong Memorial Prize for Things Fall Apart . The following year, after the publication of its sequel, No Longer At Ease , he was awarded the Nigerian National Trophy for Literature. His book of poetry, Christmas in Biafra , written during the Nigerian civil war, won the first Commonwealth Poetry Prize in 1972. More than twenty universities in Great Britain, Canada, Nigeria, and the United States have awarded Achebe honorary degrees.

Achebe died on March 21, 2013. He was 82.

Previous Character Map

Next Major Themes in Things Fall Apart

- World Biography

Chinua Achebe Biography

Born: November 15, 1930 Ogidi, Nigeria Nigerian novelist

Chinua Achebe is one of Nigeria's greatest novelists. His novels are written mainly for an African audience, but having been translated into more than forty languages, they have found worldwide readership.

Chinua Achebe was born on November 15, 1930, in Ogidi in Eastern Nigeria. His family belonged to the Igbo tribe, and he was the fifth of six children. Representatives of the British government that controlled Nigeria convinced his parents, Isaiah Okafor Achebe and Janet Ileogbunam, to abandon their traditional religion and follow Christianity. Achebe was brought up as a Christian, but he remained curious about the more traditional Nigerian faiths. He was educated at a government college in Umuahia, Nigeria, and graduated from the University College at Ibadan, Nigeria, in 1954.

Successful first effort

Achebe was unhappy with books about Africa written by British authors such as Joseph Conrad (1857–1924) and John Buchan (1875–1940), because he felt the descriptions of African people were inaccurate and insulting. While working for the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation he composed his first novel, Things Fall Apart (1959), the story of a traditional warrior hero who is unable to adapt to changing conditions in the early days of British rule. The book won immediate international recognition and also became the basis for a play by Biyi Bandele. Years later, in 1997, the Performance Studio Workshop of Nigeria put on a production of the play, which was then presented in the United States as part of the Kennedy Center's African Odyssey series in 1999. Achebe's next two novels, No Longer At Ease (1960) and Arrow of God (1964), were set in the past as well.

By the mid-1960s the newness of independence had died out in Nigeria, as the country faced the political problems common to many of the other states in modern Africa. The Igbo, who had played a leading role in Nigerian politics, now began to feel that the Muslim Hausa people of Northern Nigeria considered the Igbos second-class citizens. Achebe wrote A Man of the People (1966), a story about a crooked Nigerian politician. The book was published at the very moment a military takeover removed the old political leadership. This made some Northern military officers suspect that Achebe had played a role in the takeover, but there was never any evidence supporting the theory.

Political crusader

During the years when Biafra attempted to break itself off as a separate state from Nigeria (1967–70), however, Achebe served as an ambassador (representative) to Biafra. He traveled to different countries discussing the problems of his people, especially the starving and slaughtering of Igbo children. He wrote articles for newspapers and magazines about the Biafran struggle and founded the Citadel Press with Nigerian poet Christopher Okigbo. Writing a novel at this time was out of the question, he said during a 1969 interview: "I can't write a novel now; I wouldn't want to. And even if I wanted to, I couldn't. I can write poetry—something short, intense, more in keeping with my mood." Three volumes of poetry emerged during this time, as well as a collection of short stories and children's stories.

After the fall of the Republic of Biafra, Achebe continued to work at the University of Nigeria at Nsukka, and devoted time to the Heinemann Educational Books' Writers Series (which was designed to promote the careers of young African writers). In 1972 Achebe came to the United States to become an English professor at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst (he taught there again in 1987). In 1975 he joined the faculty at the University of Connecticut. He returned to the University of Nigeria in 1976. His novel Anthills of the Savanna (1987) tells the story of three boyhood friends in a West African nation and the deadly effects of the desire for power and wanting to be elected "president for life." After its release Achebe returned to the United States and teaching positions at Stanford University, Dartmouth College, and other universities.

Later years

For More Information

Carroll, David. Chinua Achebe. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1980.

Ezenwa-Ohaeto. Chinua Achebe: A Biography. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997.

Innes, C. L. Chinua Achebe. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

User Contributions:

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic:.

BlackPast is dedicated to providing a global audience with reliable and accurate information on the history of African America and of people of African ancestry around the world. We aim to promote greater understanding through this knowledge to generate constructive change in our society.

Chinua achebe (1930-2013).

Chinua Achebe of Nigeria was one of the most famous 20th Century African writers . He published his first novel Things Fall Apart in 1958 and has since published four more novels and a series of short stories, essays, and other literature. Much of Achebe’s work focuses on the themes of colonialism, post-colonialism, and the tumultuous political atmosphere in post colonial Nigeria.

Albert Chinualumogu Achebe was born on November 16, 1930 at St. Simon’s Church, Nneobi, Nigeria to a father who was a Christian teacher and missionary . Achebe was very heavily influenced by his native Igbo culture in Eastern Nigeria as well as his father’s desire for all his children to earn their education. Throughout his schooling Achebe was consistently at the top of his class and twice completed two grades within a year. In 1948 Achebe began his university career by attending University College in Ibadan which was affiliated with the University of London ( UK ). While at University College, Chinua Achebe switched his major from Medicine to English and History .

Chinua Achebe graduated in 1954 and left to teach at the Merchant of Light School in Eastern Nigeria. After four months he was offered and accepted a job at the Nigerian Broadcasting Service as the senior broadcasting officer of the Eastern Region. It was during this time that his first novel was published. Achebe also met his future wife, Christie Chinwe Okoli, a co-worker at the Nigerian Broadcasting Service. The two married September 10, 1961.

In October of 1960 Nigeria claimed its independence from Great Britain. Around the same time, Achebe published his second novel, No Longer at Ease . Achebe became the editor for the African Writers Series in 1962 and published his third novel, Arrow of God , in 1964. By that point regional and ethnic tensions began to push Nigeria toward civil war. The 1964 national census was disputed and election results were manipulated. Soon after the disputed census and election, the first two coups in Nigerian history occurred as Army officers deposed the civilian government and then each other. Achebe’s fourth novel, A Man of the People , explored these rapidly evolving developments in Nigerian society

Between 1967 and 1970 Nigeria was convulsed in a civil war as the Igbo people attempted to form their own republic, Biafra . Achebe was active in publicizing this struggle internationally. After the rebellion was crushed, Achebe left Nigeria and became a Professor of English in the United States, first at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and later at the University of Connecticut at Storrs. Eventually he returned to Nigeria and taught at the University of Nigeria , Nsukka.

In 1987 Achebe published his last novel , Anthills of the Savannah . Three years later he was paralyzed from the waist down in a car accident in Lagos, Nigeria. Chinua Achebe died in Boston on March 22, 2013. He was 82.

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this available to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone.

BlackPast.org is a 501(c)(3) non-profit and our EIN is 26-1625373. Your donation is fully tax-deductible.

Cite this entry in APA format:

Source of the author's information:.

C.L. Innes, Chinua Achebe (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990); Ezenwa-Ohaeto, Chinua Achebe: A Biography (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1997); http://www.bbc.co.uk/bbcfour/documentaries/profile/chinua-achebe.shtml ; http://www.kirjasto.sci.fi/achebe.htm .

Your support is crucial to our mission.

Donate today to help us advance Black history education and foster a more inclusive understanding of our shared cultural heritage.

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Chinua Achebe : a biography

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

510 Previews

5 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

EPUB and PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by [email protected] on August 30, 2018

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

You are here

Chinua achebe.

Chinua Achebe (1930 – 2013) was an Igbo writer and one of the most important voices in what is now referred to as postcolonial literature. He was born in Ogidi, several kilometres from the Niger River in the south of the territory which would become Nigeria in 1960, upon its independence from the British Empire. His parents were Protestant converts and he spent much of his childhood immersed in their Christian teachings, a background which plays out heavily in depictions of religion in his future writing. An Igbo speaker at home, Achebe started learning English at eight years old.

In 1948, Achebe enrolled at University College (affiliated with the University of London and now known as the University of Ibadan) with a scholarship to read medicine. However, he swiftly changed the subject of his studies to English, losing the scholarship as a result. During this time, Achebe decided to alter his birth name – Albert Chinụalụmọgụ Achebe – as a symbol of resistance against his namesake, the husband of Queen Victoria; or rather, against the empire over which Victoria was sovereign. While studying English literature and reading colonialist narratives, such as Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899) and Joyce Cary’s Mister Johnson (1939), Achebe became increasingly critical of how literature written in the English language had hitherto represented the African continent (including West Africa). He sought to challenge the ways in which literature was complicit in promoting the British Empire through negative stereotypes of colonised and enslaved peoples. Influenced by the small number of Nigerian authors publishing in English, including Amos Tutuola and Wole Soykina who taught at his university, Achebe turned to writing as a means to change how stories about West Africans were being told.

After working for the colonial Nigerian Broadcasting Service (NBC) for several years, Achebe completed his first novel, Things Fall Apart , in 1958, basing the title on a line by the Irish poet W. B. Yeats. Achebe’s manuscript was declined by multiple London publishing houses before eventually being accepted by Heinemann. The publishers reprinted it in 1962 as the very first volume in its African Writers Series (which continued until the 1980s). Set in the nineteenth century, the novel is a poignant tragedy based around a complex and deeply-afflicted protagonist, Okonkwo, who, among other personal issues, struggles with the advent of British imperialism in his Igbo village, Umuofia, which arrived through Christian missionary activity. The novel ends by showing readers a glimpse of an English language report about Umuofia by a British District Commissioner, powerfully symbolising the dangerous ways in which West African settings, peoples, and history have long been inadequately and negatively depicted by ethnographers sympathetic to the British Empire.

The novel has had a monumental impact and it continues to influence writers across the globe. It has been translated into over 50 languages and sold nearly 13 million copies. It inspired Achebe to pen two sequels, No Longer at Ease (1960) and Arrow of God (1964), forming his ‘African Trilogy’ which traces Okonkwo’s descendents across Nigeria’s ever-changing modern history. Achebe has been called the ‘Father of Modern African Literature’. According to Ben Okri, Achebe ‘was a man who answered the questions of his times, the times in which he found himself, in tough, brief, elegant novels and in doing that actually helped to create a language of literature in which many of us came to write in afterwards’.

This connection between literature, history, language, and authenticity is crucial to understanding Achebe’s prose. Indeed, his decision to compose in English was influential, but not without controversy – especially in terms of his important philological debates with the Kenyan writer, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, who had rejected English as his literary language. These very debates have been vital to postcolonial discussions on the role played by specific languages choices when writing postcolonial texts. Moreover, Achebe’s prose is rich with the cadences of Nigerian English and Nigerian Pidgin, and is filled with numerous Igbo words and proverbs, bringing to print a linguistic form which celebrates the speech of people living in Nigeria.

Achebe’s final two novels, A Man of the People (1966) and Anthills of the Savannah (1987), primarily explore corruption in the highest political levels of Nigerian society in the years after its independence. He wrote powerfully against the warfare and imposed famine against Biafra (between 1967 and 1970) during which time many of his peers were imprisoned, including Soyinka, and two million civilians died, many from starvation.

In one of his many published essays, Achebe states that ‘the writer is often faced with two choices – turn away from the reality of life’s intimidating complexity or conquer its mystery by battling with it. The writer who chooses the former soon runs out of energy and produces elegantly tired fiction’. Achebe absolutely never ‘turn[ed] away’ from unpacking and depicting the violent impact of imperialism on Nigeria. He explored the nation’s complicated relationship with religion, language, and literature with great nuance and with compelling attention to the consequence of these issues on the individual. It is for this reason that he is one of the most significant authors of the twentieth century.

If reusing this resource please attribute as follows: Chinua Achebe at http://writersinspire.org/content/chinua-achebe by Daniele Nunziata, licensed as Creative Commons BY-NC-SA (2.0 UK).

Chinua Achebe

Chinua Achebe was born on the 16th of November, in 1930 to Isaiah Okafo Achebe, a servant of the church missionary society, and Janet Anaenechi Iloegbunam. He spent his childhood in Igbo town. The storytelling was part of an ancient tradition in the Igbo society. His mother and sister used to narrate him various stories on Chinua’s request, which helped him develop his interest in literature. His father also had vast literary collection along with with the pictures of colleges hung at their home including, Shakespeare’s literature and ‘The Pilgrim’s Progress’. These influences played a crucial role in his early development toward writing.

Since Chinua belonged to a literate family, his family played a positive role in shaping his literary mind during the early years. First, he attended society’s school, where he began to learn English at the age of eight. At fourteen, he was among the few selected to attend the best government college in Africa . In 1948, he attended University College Ibadan, where he studied medicine, but could not develop an interest in that area. Soon he switched to literature and stunned others with his literary creativity. In 1950, he wrote a literary piece, Polar Undergraduate for University newspaper, Herald, followed by other letters and essays in another magazine, The Bug. After his graduation in 1953, he decided to become a writer and started working in this direction. Also, his teacher, Gilbert Phelps, a literary critic, and novelist, assisted him in his writings.

In 1958, Achebe traveled to Enugu to perform administrative duties. There, he met and developed a relationship with his fellow worker, Christiana Chinwe Okoli. The couple tied the knot on the 10 th of September in 1961 in the chapel of the University of Ibadan. Although they had a peaceful marital relationship, they were worried about the prejudiced view of the world towards African people.

Chinua Achebe, the founding father of African writing, met a fatal accident in Nigeria in 1990. This accident left him paralyzed for the rest of his life. Despite the life-changing incident, he did not give up on life and continued to render his services for literature. This towering figure breathed his last at the age of eighty-two on 21 st March 2013.

Some Important Facts of His Life

- He was awarded thirty honorary degrees from universities of Canada, Scotland, England, Nigeria, and the United States.

- He became the first living writer to have appeared in the Everyman’s Library Collection.

- He won many awards including, The Man Booker International Prize, the Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize, and the Nigerian National Order of Merit.

Writing Career

Chinua was inspired by the storytelling tradition while growing up, which was combined with traditional events and ceremonies. He started writing as a career at a very young age. His early literary pieces that appeared in his school magazines were the mouthpieces of his literary excellence. He highlighted the collective details of life in Nigeria in contrast with Christian institutions in most of those pieces. Other short stories , including Dead Man’s Path and The Order in Conflict , reflect upon the conflict between modernity and rural traditions. Later, his teacher Gilbert Phelps’s acknowledgment and guide helped him produce his universally acclaimed work, Things Fall Apart , in 1958. Through Things Fall apart , Chinua presented the clash between the white Christian missionaries and native African culture. Later, in his novels, No Longer at Ease, Arrow of God and Man of the People, he documented conflict between African tradition and colonial practices. His other notable works include How the Leopard Got His Claws , Morning Yet on Creation Day and Anthills of the Savannah.

Chinua Achebe stands among the most influential figures of world literature. With the help of his unique writing style , he skillfully wove ancient folktales of the Igbo tribe into his stories. He always highlighted cultural values in those tales. His universally acclaimed novel , Things Fall Apart , is one of the best books in the world. Chinua also used many literary devices in his work to make readers understand the themes and messages through characters and stories. To illustrate the values of Igbo’s oral story tradition, he used proverb in his pieces, such as; The Arrow of God and No Longer at Ease. His writings were marked with irony , metaphors , and humor , as he presented the impact of colonialism on the Nigerian people. Also, he avoided imitating the trends set for English novels. He would alter the sentence syntax , usage, and idiom , into a distinctly African style, which won applause from critics and his fellow writers. The recurring themes in most of his literary pieces are cultural, identity, justice , discrimination, fate, and free will.

Chinua Achebe’s Famous Works

- Novels: He was an outstanding writer some of his best novels are Things Fall Apart , No Longer at Ease, A Man of People, Arrow of God, and Anthills of the Savannah.

- Other Works: Besides novels, he tried his hands on poetry and shorter fiction . Some of them include “Marriage is a Private Affair”, “Dead man’s Path”, “Civil Peace”, “Another Africa” and “Don’t Let Him Die.”

Chinua Achebe’s Impact on Future Literature

Chinua Achebe, with his unique abilities, left a profound impact on global literature. His intellectual ideas, along with distinct literary qualities, won a special place among his readers, critics, and fellow writers. His impact resonates strongly inside as well as outside Africa. Because of his literary services, Chinua was called the father of modern African writing . His masterpieces provide inspiration and principles for the writers of succeeding generations. He also successfully documented his ideas about equality , power , and injustice in his writings. Even today, writers try to imitate his unique style, considering him as an example for writing prose and poetry.

Famous Quotes

- We shall all live. We pray for life, children, a good harvest, and happiness. You will have what is good for you and I will have what is good for me. Let the kite perch and let the egret perch too. If one says no to the other, let his wing break. ( Things Fall Apart )

- i am against people reaping where they have not sown. But we have a saying that if you want to eat a toad you should look for a fat and juicy one. ( No Longer at Ease)

- You must develop the habit of scepticism, not swallow every piece of superstition you are told by witch-doctors and professors. ( Anthills of Savannah)

Related posts:

- Things Fall Apart Characters

- Things Fall Apart Quotes

- Things Fall Apart Themes

- Things Fall Apart

Post navigation

Chinua Achebe: the literary giant who shaped African narrative

- The African History

- September 12, 2023

- Art , Inspirational , Personality Profile

Chinua Achebe, a name synonymous with African literature, stands as a towering figure whose words have resonated across the globe.

Born in Nigeria in 1930, Achebe’s life and works have left an indelible mark on the world of literature. From his groundbreaking novel “Things Fall Apart” to his essays and poetry, Achebe’s contribution to African literature is immeasurable.

This article delves into the life, works, and enduring legacy of Chinua Achebe.

Early Life and Education

Chinua Achebe was born in Ogidi, Nigeria, into the Igbo ethnic group. He was raised in a vibrant cultural milieu, surrounded by traditional Igbo storytelling and rituals. Achebe’s early exposure to his rich African heritage would profoundly influence his later writing.

He attended Government College Umuahia and later the University of Ibadan, where he studied English, history, and theology.

Achebe’s education exposed him to both Western and African literary traditions, providing him with a unique perspective that would become a hallmark of his writing.

Literary Breakthrough – “Things Fall Apart”

In 1958, Achebe published his first novel, “Things Fall Apart.” This seminal work is often considered the cornerstone of African literature. Set in pre-colonial Nigeria, the novel vividly portrays the clash between African traditions and the forces of colonialism and Christianity.

Through the life of the protagonist, Okonkwo, Achebe masterfully explores themes of cultural identity, change, and the consequences of colonial oppression.

“Things Fall Apart” was groundbreaking for several reasons. It presented an authentic African perspective, countering the prevailing stereotypes of Africa in Western literature.

Achebe’s use of language was revolutionary, as he wrote the novel in English but infused it with African idioms and proverbs, creating a distinct narrative voice.

Achebe’s Influence on African Literature

Chinua Achebe’s impact on African literature is immeasurable. He opened the door for generations of African writers to tell their own stories and challenge stereotypes.

His work inspired a literary movement known as African literature in English, and he mentored many aspiring writers.

In addition to novels, Achebe wrote essays and criticism, addressing issues of identity, language, and African literature’s role in a post-colonial world.

His essay “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness” is a seminal critique of Joseph Conrad’s novel and its portrayal of Africa.

Legacy and Later Works

Chinua Achebe’s literary output extended beyond “Things Fall Apart.” He authored several novels, including “No Longer at Ease,” “Arrow of God,” and “A Man of the People.” These works continued to explore the complexities of African identity and the challenges faced by African societies in a changing world.

In 2007, Achebe published “There Was a Country,” a memoir chronicling his experiences during the Nigerian Civil War. This book provides valuable insights into Achebe’s political views and his deep commitment to his homeland.

Chinua Achebe’s literary legacy endures as a beacon of African storytelling. His ability to blend tradition and modernity, and his unapologetic commitment to African culture, have made his works timeless.

Achebe’s words continue to resonate, inspiring writers and readers alike to explore the rich tapestry of African literature and history.

His contributions to literature and his unrelenting advocacy for African voices have firmly established him as a literary luminary whose influence extends far beyond the pages of his books.

Related posts

- Inspirational

Dreams Unbarred: A Call for Youth Empowerment in Africa

- April 15, 2024

Sadio Mane privately weds longtime girlfriend in simple wedding

- January 8, 2024

- Ancient Egypt

- Personality Profile

King Afonso I of Kongo, ruler of the Kongolese Kingdom (1509 -1543)

- December 28, 2023

Kilwa Kisiwani: One of the Great Ancient African Cities

- December 13, 2023

Chinua Achebe obituary

Chinua Achebe, who has died aged 82 , was Africa's best-known novelist and the founding father of African fiction. The publication of his first novel, Things Fall Apart , in 1958 not only contested European narratives about Africans but also challenged traditional assumptions about the form and function of the novel. His creation of a hybrid that combined oral and literary modes, and his refashioning of the English language to convey Igbo voices and concepts, established a model and an inspiration for other novelists throughout the African continent.

The five novels and the short stories he published between 1958 and 1987 provide a chronicle of Nigeria's troubled history since the beginning of British colonial rule. They also create a host of vivid characters who seek in varying ways to take control of their history. As founding editor of the influential Heinemann African writers series, he oversaw the publication of more than 100 texts that made good writing by Africans available worldwide in affordable editions.

Born in the traditional Igbo village of Ogidi, eastern Nigeria, some 40 years after missionaries first arrived in the region, Achebe was christened Albert Chinualumogu by his Christian convert parents. Later, in an autobiographical essay entitled Named for Victoria, Queen of England, he told how, like Queen Victoria, he "lost his Albert".

Growing up as a Christian allowed him to observe his world more clearly, he wrote. The slight distance from each culture became "not a separation but a bringing together like the necessary backward step which a judicious viewer might take in order to see a canvas steadily and fully".

At the local missionary school, however, the children were forbidden to speak Igbo, and were encouraged to disown all traditions that might be associated with a "pagan" way of life. Nevertheless, Achebe absorbed the folk tales told to him by his mother and older sister, stories he described as having "the immemorial quality of the sky, and the forests and the rivers".

When he was 14, Achebe was sent to the prestigious colonial Government college at Umuahia, where his schoolmates included the poet Christopher Okigbo, his close friend. In 1948, he won a scholarship to study medicine at what became the University of Ibadan. After his first year, however, he realised it was writing that most appealed to him, and he switched to a degree in English literature, religious studies and history.

Although the English curriculum closely followed Britain's, teachers also introduced works they considered relevant to their Nigerian students, such as Joyce Cary 's African novels and Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness. But such works were at odds with the changing mentality brought about by the anti-colonial movements in west Africa following the second world war.

Achebe was among several future literary stars, including Wole Soyinka, who, between 1948 and 1952, contributed stories and essays to student magazines with a nationalist orientation. Even in these early pieces, one can discern Achebe's characteristic qualities: a coolly amused view of the educated elite, a carefully balanced structure of contrasts, a pleasure in mimicking or parodying various modes of discourse, an interest in rural Nigeria and the uneasy interaction between western and Igbo cultures, and an insistence on what he saw as the crucial Igbo value of tolerance. It is in one of these stories that a favourite proverb of his makes its first appearance: "Let the hawk perch and let the eagle perch."

By the time he graduated in 1952, Achebe had decided to be a writer telling the story of Africans and the colonial encounter from an African point of view. One of his motivations was Cary's Nigeria-set novel Mister Johnson, which, though much praised by English critics, seemed to him "a most superficial picture of Nigeria and the Nigerian character". He thought: "If this was famous, then someone ought to try and look at this from the inside."

What had originally been planned as one long novel, beginning with the colonisation of eastern Nigeria and ending just before independence, turned into two shorter novels, Things Fall Apart (set in the late 19th century) and No Longer at Ease (set in the decade before Nigeria gained its independence). While the second novel takes up and retells the plot of Mister Johnson – the story of a young Nigerian clerk who takes a bribe and is tried and sentenced by the colonial administration – the first seeks, with consummate success, to evoke the culture and society Mister Johnson and his ancestors might have come from.

Things Fall Apart recreates an oral culture and a consciousness imbued with an agrarian way of life, and demonstrates, as Achebe put it, "that African peoples did not hear of civilisation for the first time from Europeans". At the same time, he sought to avoid depicting precolonial Africa as a pastoral idyll, rejecting the nostalgic evocations of Léopold Senghor and the francophone négritude school of writing.

The protagonist, Okonkwo, emerges as a heroic but rigid character, whose fear of appearing weak leads him to act harshly towards his wives and children and to participate in the sacrifice of a young hostage from another village. Its characterisation and enclosed rural world have been compared to The Mayor of Casterbridge by Thomas Hardy, a novelist Achebe admired. Things Fall Apart has sold millions of copies and has been translated into more than 50 languages.

No Longer at Ease, set in 1950s Nigeria and published in 1960, takes up the story of Okonkwo's grandson, an idealistic young Nigerian civil servant who returns home after studying in England, finds his salary inadequate for his expected lifestyle, and takes a bribe.

By this time, Achebe himself had been on the first of many trips abroad. As head of the talks department at the Nigerian Broadcasting Service (NBS), he was sent in 1956 on a short training course with the BBC in London. Back in Nigeria, he edited and produced discussion programmes and short stories for the NBS in Enugu, eastern Nigeria, and learned much about how good dialogue works. There, he met Christie Chinwe Okoli, a beautiful and brilliant student from Ibadan University. They married in 1961 and had four children.

While preparing a feature on the response of Nigerians to early colonial rule, Achebe investigated the story of an Igbo priest imprisoned for refusing to collaborate with the British. Fascinated by the tale and the priest's proud character, he made it the focus of his third novel, Arrow of God (1964). Some critics regard this as Achebe's greatest achievement, with its complex structure and characterisation, and its interrogation of the interstices between subjective desire and external forces in the making of history.

The concerns with responsible leadership that inform Arrow of God are taken up more explicitly in his satirical fourth novel, A Man of the People (1966). It exposes the corruption and irresponsibility of politicians and their constituents, ending with a military coup – as indeed happened in post-independence Nigeria in 1966, a coup that led to the attempted secession of Biafra and a civil war in which more than a million people died.

When the massacre of Igbos began in the north following the coup, Achebe was working for the Nigerian Broadcasting Commission in Lagos. Warned that he might be in danger (a cousin was one of the military leaders assassinated), Achebe took his family to eastern Nigeria. He became a strong advocate of Biafra's independence, travelling the world to seek support. In his view, Biafra was not only a territory that could ensure the survival of Igbo peoples, but also an ideal. Speaking in 1968, he declared: "Biafra stands for true independence in Africa, for an end to the 400 years of shame and humiliation which we have suffered in our association with Europe … I believe our cause is right and just. And this is what literature should be about today – right and just causes."

Although the war ended in defeat for the Biafran cause, Achebe was determined the Igbo presence and perspectives should continue within the Nigerian nation. His collection of poems Beware Soul Brother (1971) and the volume of short stories Girls at War and Other Stories (1972) drew on the experiences of the war. He became a senior research fellow at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, and in 1971 he and a group of Nigerian academics founded Okike, an important journal for African creative writing and critical debate. He also wrote several books for children.

In 1972, Achebe accepted a visiting professorship at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where he taught African literature and continued to edit Okike. It was there that I first met him and worked as an assistant editor for Okike. I also attended and occasionally co-taught his course on African writing, and admired his patience with students who sometimes made all too evident their ignorance and prejudice with regard to African culture.

That tolerance, and indeed friendship, extended to colleagues such as a professor who jokingly promised to provide native girls for all the members of his department when he became head. I looked across at Achebe and saw him raise an eyebrow. Despite his passionate condemnation of racism and imperial arrogance, it is Achebe's gentle irony, ready laughter and his delight in anecdotes about our children's antics that I most vividly remember.

He did not retreat from controversy. In essays, lectures and interviews, he declared the need for committed writing in the African context, and derided writers and critics whose attitudes to Africans he found condescending or racist. At the University of Massachusetts, he denounced Heart of Darkness in a lecture that caused many in the audience to walk out in protest, and still arouses debate.

Achebe returned to Nigeria in 1976 to be professor of literature at the University of Nigeria, where he continued to teach, became chairman of the Association of Nigerian Writers and edited Uwa ndi Igbo, the Journal of Igbo Life and Culture. He was also elected deputy national president of the People's Redemption party and published a political pamphlet, The Trouble With Nigeria, in 1983.

Achebe not only created a new kind of novel, but was also unwilling to repeat the same formula. Each novel set up a dialogue with its predecessor, technically and formally as well as with regard to character and social milieu. This process culminated in his fifth novel, Anthills of the Savannah (1987), which commented on the forms and themes of his own works and those of other African writers. The novel insists there is no one story of the nation, but a multiplicity of narratives, weaving continuities between past and present, Igbo and English cultural forms and traditions. The philosophy, structure and aesthetic of Anthills of the Savannah, and indeed of all of Achebe's fiction, is summarised in the final sentences of his essay The Truth of Fiction: "Imaginative literature … does not enslave; it liberates the mind of man. Its truth is not like the canons of orthodoxy or the irrationality of prejudice and superstition. It begins as an adventure in self-discovery and ends in wisdom and humane conscience."

In 1990, a car accident left Achebe paralysed. Bard College, New York, offered him and Christie the possibility of teaching there and provided the facilities he needed. Now using a wheelchair, he continued to travel and lecture in the US and occasionally abroad. His talks at Harvard in 1998 were published under the title Home and Exile.

His more recent lectures and autobiographical essays were published in The Education of a British-Protected Child (2009). He moved to Providence, Rhode Island, in 2009 after being appointed professor of Africana studies at Brown University. In 2012 he published There Was a Country: A Personal History of Biafra, which reiterated his belief in the ideals that had inspired the nationalism of his younger days. His account of the events that led to the civil war, its conduct and aftermath have stirred strong reactions from supporters as well as opponents of the Biafran cause.

Achebe received numerous awards and more than 30 honorary doctorates, but among the tributes he may have valued most was Nelson Mandela's. "There was a writer named Chinua Achebe ," Mandela wrote, "in whose company the prison walls fell down."

He is survived by Christie, their daughters, Chinelo and Nwando, and their sons, Ikechukwu and Chidi.

- Chinua Achebe

- Higher education

Chinua Achebe funeral celebrates revered Nigerian author

Novelist Chinua Achebe dies, aged 82

Calls for Chinua Achebe Nobel prize 'obscene', says Wole Soyinka

Nigeria in mourning for Chinua Achebe

Chinua Achebe peered deep into the Nigerian psyche

Chinua Achebe: leader of a generation

Chinua Achebe, Nigerian novelist and poet - in pictures

Chinua Achebe's anti-colonial novels are still relevant today

Chinua Achebe: A life in writing

The great Chinua Achebe was the man who gave Africa a voice

Most viewed.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Chinua Achebe, African Literary Titan, Dies at 82

By Jonathan Kandell

- March 22, 2013

Chinua Achebe, the Nigerian author and towering man of letters whose internationally acclaimed fiction helped to revive African literature and to rewrite the story of a continent that had long been told by Western voices, died on Thursday in Boston. He was 82.

His agent in London said he had died after a brief illness. Mr. Achebe had used a wheelchair since a car accident in Nigeria in 1990 left him paralyzed from the waist down.

Chinua Achebe (pronounced CHIN-you-ah Ah-CHAY-bay) caught the world’s attention with his first novel, “Things Fall Apart.” Published in 1958, when he was 28, the book would become a classic of world literature and required reading for students, selling more than 10 million copies in 45 languages.

The story, a brisk 215 pages, was inspired by the history of his own family, part of the Ibo nation of southeastern Nigeria, a people victimized by the racism of British colonial administrators and then by the brutality of military dictators from other Nigerian ethnic groups.

“Things Fall Apart” gave expression to Mr. Achebe’s first stirrings of anti-colonialism and a desire to use literature as a weapon against Western biases. As if to sharpen it with irony, he borrowed from the Western canon itself in using as its title a line from Yeats’s apocalyptic poem “The Second Coming.”

“In the end, I began to understand,” Mr. Achebe later wrote. “There is such a thing as absolute power over narrative. Those who secure this privilege for themselves can arrange stories about others pretty much where, and as, they like.”

Though Mr. Achebe spent his later decades teaching at American universities, most recently at Brown, his writings — novels, stories, poems, essays and memoirs — were almost invariably rooted in the countryside and cities of his native Nigeria. His most memorable fictional characters were buffeted and bewildered by the competing pulls of traditional African culture and invasive Western values.

“Things Fall Apart,” which is set in the late 19th century, tells the story of Okonkwo, who rises from poverty to become a wealthy farmer and Ibo village leader. British colonial rule throws his life into turmoil, and in the end, unable to adapt, he explodes in frustration, killing an African in the employ of the British and then committing suicide.

The acclaim for “Things Fall Apart” was not unanimous. Some British critics thought it idealized precolonial African culture at the expense of the former empire.

“An offended and highly critical English reviewer in a London Sunday paper titled her piece cleverly, I must admit, ‘Hurray to Mere Anarchy!’ ” Mr. Achebe wrote in “ Home and Exile ,” a 2000 collection of autobiographical essays. Some critics found his early novels to be stronger on ideology than on narrative interest. But his stature grew, until he was considered a literary and political beacon , influencing generations of African writers as well as many in the West.

“It would be impossible to say how ‘Things Fall Apart’ influenced African writing,” the Princeton scholarKwame Anthony Appiah once wrote. “It would be like asking how Shakespeare influenced English writers or Pushkin influenced Russians.”

Mr. Appiah, a professor of philosophy, found an “intense moral energy” in Mr. Achebe’s work, adding that it “captures the sense of threat and loss that must have faced many Africans as empire invaded and disrupted their lives.”

Nadine Gordimer, the South African novelist and Nobel laureate, hailed Mr. Achebe in a review in The New York Times in 1988, calling him “a novelist who makes you laugh and then catch your breath in horror — a writer who has no illusions but is not disillusioned.”

Mr. Achebe’s political thinking evolved from blaming colonial rule for Africa’s woes to frank criticism of African rulers and the African citizens who tolerated their corruption and violence. Indeed, it was Nigeria’s civil war in the 1960s and then its military dictatorship in the 1980s and ‘90s that forced Mr. Achebe abroad.

In his writing and teaching Mr. Achebe sought to reclaim the continent from Western literature, which he felt had reduced it to an alien, barbaric and frightening land devoid of its own art and culture. He took particular exception to"Heart of Darkness,"the novel byJoseph Conrad, whom he thought “a thoroughgoing racist.”

Conrad relegated “Africa to the role of props for the breakup of one petty European mind,” Mr. Achebe argued in his essay “ An Image of Africa .”

“I grew up among very eloquent elders,” he said in an interview with The Associated Press in 2008. “In the village, or even in the church, which my father made sure we attended, there were eloquent speakers.” That eloquence was not reflected in Western books about Africa, he said, but he understood the challenge in trying to rectify the portrayal.

“You know that it’s going to be a battle to turn it around, to say to people, ‘That’s not the way my people respond in this situation, by unintelligible grunts, and so on; they would speak,’ ” Mr. Achebe said. “And it is that speech that I knew I wanted to be written down.”

Albert Chinualumogu Achebe was born on Nov. 16, 1930, in Ogidi, an Ibo village. His father became a Christian and worked for a missionary teacher in various parts of Nigeria before returning to the village. As a student, Mr. Achebe immersed himself in Western literature. At the University College of Ibadan, whose professors were Europeans, he read Shakespeare, Milton, Defoe, Swift, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Keats and Tennyson. But the turning point in his education was the required reading of"Mister Johnson,"a 1939 novel set in Nigeria and written by an Anglo-Irishman, Joyce Cary.

The protagonist is a docile Nigerian whose British master ultimately shoots and kills him. Like reviewers in the Western press, Mr. Achebe’s white professors praised it as one of the best novels ever written about Africa. But Mr. Achebe and his classmates responded with “exasperation at this bumbling idiot of a character,” he wrote.

He soon joined a generation of West African writers who in the 1950s were coming to the realization that Western literature was holding the continent captive. A fellow Nigerian, Amos Tutuola, opened the floodgates with his 1952 novel, “The Palm-Wine Drinkard.”

After graduating from college in 1953, Mr. Achebe moved to London, where he worked for the British Broadcasting Corporation while writing stories. It was in London that he wrote “Things Fall Apart,” in longhand.

After returning to Nigeria to revise the manuscript, he mailed it — the only existing copy — to a London typing service, which promptly misplaced it, filling Mr. Achebe with despair. It was discovered only months later.

Publishers initially passed on the manuscript, doubting that African fiction would sell, until an adviser at the Heinemann publishing house seized on it as a work of brilliance.

In his second novel, “ No Longer at Ease ,” in 1960, he tells the story of Okonkwo’s grandson, Obi, who learns to fit into British colonial society. Raised as a Christian and educated in England, Obi abandons the countryside for a job as a civil servant in Lagos, which was the capital at the time. Cut off from traditional values, he succumbs to greed and in the end is prosecuted for graft.

In his third novel, “Arrow of God” (1964), Mr. Achebe reverts to the setting of an Ibo village in the early 20th century. The village priest, Ezeulu, sends his son, Oduche, to be educated by Christian missionaries in the hope that he will learn British ways and thus help protect his community. Instead Oduche becomes a convert to colonialism and attacks Ibo religion and culture.

The Nigerian civil war, also known as the Biafran war, shattered Mr. Achebe’s hopes for a more promising postcolonial future, and deeply affected his literary output. The scene was set for war when, in January 1966, Ibo army officers killed the prime minister and other officials and seized power. Seven months later, the insurgents were ousted in a counter-coup by military commanders from the Muslim northern region.

Before the year ended, Muslim troops had massacred some 30,000 Ibo people living in the north. In 1967 the Ibo then seceded from Nigeria, declaring the southeastern region the independent Republic of Biafra, and the civil war began in earnest, raging through 1970 until government troops invaded and crushed the secessionists.

Mr. Achebe’s fourth novel, “A Man of the People,” published in early 1966, had predicted this course of events with such accuracy that the military government in Lagos decided he must have been a conspirator in the first coup, an accusation he denied. Mr. Achebe fled, settling in Britain with his wife, Christiana; their two sons, Ikechukwu and Chidi; and two daughters, Chinelo and Nwando. (Information about his survivors was not immediately available.)

After the civil war, Mr. Achebe returned to Nigeria for two years before accepting faculty posts in the 1970s at the University of Massachusetts and the University of Connecticut. He returned home again in 1979 to teach English at the University of Nigeria.

The civil war was the theme of many of his writings during these years. Among the most prominent were a book of poetry, “ Beware Soul Brother ” (1971), which won the Commonwealth Poetry Prize, and a short-story collection,"Girls at War,” which appeared in 1972.

But for more than 20 years a case of writer’s block kept him from producing another novel. He attributed the dry spell to emotional trauma that had lingered after the civil war.

“The novel seemed like a frivolous thing to be doing,” he told The Washington Post in 1988.

That year Mr. Achebe finally published his fifth novel, “Anthills of the Savannah,” the story of three former school chums in a fictional country modeled after Nigeria. One of them becomes a military dictator; another is appointed minister of information; and the third is named editor of the leading newspaper. All meet violent ends.

The novel was widely admired. Discussing it in 1988 in The New York Review of Books, the Scottish journalist Neal Ascherson wrote: “Chinua Achebe says, with implacable honesty, that Africa itself is to blame, and that there is no safety in excuses that place the fault in the colonial past or in the commercial and political manipulations of the First World.”

Mr. Achebe barely had time to savor the acclaim before the car accident outside Lagos that injured him. He received medical treatment in London and moved to the United States, taking a teaching post at Bard College in the Hudson River valley, where he remained until 2009. He received the Man Booker International Prize for lifetime achievement in 2007. Last fall he published “There Was a Country: A Personal History of Biafra.”