- OpenBU

- Theses & Dissertations

- Dissertations and Theses (1964-2011)

Familial and psychological factors associated with separation anxiety in the preschool child

Date Issued

Export Citation

Embargoed until:, permanent link, description, collections.

- Dissertations and Theses (1964-2011) [1594]

Deposit Materials

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Separation anxiety disorder

Separation anxiety is a normal stage of development for infants and toddlers. Young children often experience a period of separation anxiety, but most children outgrow separation anxiety by about 3 years of age.

In some children, separation anxiety is a sign of a more serious condition known as separation anxiety disorder, starting as early as preschool age.

If your child's separation anxiety seems intense or prolonged — especially if it interferes with school or other daily activities or includes panic attacks or other problems — he or she may have separation anxiety disorder. Most frequently this relates to the child's anxiety about his or her parents, but it could relate to another close caregiver.

Less often, separation anxiety disorder can also occur in teenagers and adults, causing significant problems leaving home or going to work. But treatment can help.

Products & Services

- A Book: A Practical Guide to Help Kids of All Ages Thrive

Separation anxiety disorder is diagnosed when symptoms are excessive for the developmental age and cause significant distress in daily functioning. Symptoms may include:

- Recurrent and excessive distress about anticipating or being away from home or loved ones

- Constant, excessive worry about losing a parent or other loved one to an illness or a disaster

- Constant worry that something bad will happen, such as being lost or kidnapped, causing separation from parents or other loved ones

- Refusing to be away from home because of fear of separation

- Not wanting to be home alone and without a parent or other loved one in the house

- Reluctance or refusing to sleep away from home without a parent or other loved one nearby

- Repeated nightmares about separation

- Frequent complaints of headaches, stomachaches or other symptoms when separation from a parent or other loved one is anticipated

Separation anxiety disorder may be associated with panic disorder and panic attacks — repeated episodes of sudden feelings of intense anxiety and fear or terror that reach a peak within minutes.

When to see a doctor

Separation anxiety disorder usually won't go away without treatment and can lead to panic disorder and other anxiety disorders into adulthood.

If you have concerns about your child's separation anxiety, talk to your child's pediatrician or other health care provider.

Sometimes, separation anxiety disorder can be triggered by life stress that results in separation from a loved one. Genetics may also play a role in developing the disorder.

Risk factors

Separation anxiety disorder most often begins in childhood, but may continue into the teenage years and sometimes into adulthood.

Risk factors may include:

- Life stresses or loss that result in separation, such as the illness or death of a loved one, loss of a beloved pet, divorce of parents, or moving or going away to school

- Certain temperaments, which are more prone to anxiety disorders than others are

- Family history, including blood relatives who have problems with anxiety or an anxiety disorder, indicating that those traits could be inherited

- Environmental issues, such as experiencing some type of disaster that involves separation

Complications

Separation anxiety disorder causes major distress and problems functioning in social situations or at work or school.

Disorders that can accompany separation anxiety disorder include:

- Other anxiety disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder, panic attacks, phobias, social anxiety disorder or agoraphobia

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder

There's no sure way to prevent separation anxiety disorder in your child, but these recommendations may help.

- Seek professional advice as soon as possible if you're concerned that your child's anxiety is much worse than a normal developmental stage. Early diagnosis and treatment can help reduce symptoms and prevent the disorder from getting worse.

- Stick with the treatment plan to help prevent relapses or worsening of symptoms.

- Seek professional treatment if you have anxiety, depression or other mental health concerns, so that you can model healthy coping skills for your child.

- Separation anxiety disorder. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5. 5th ed. Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. http://dsm.psychiatryonline.org. Accessed Feb. 28, 2018.

- Separation anxiety disorder. Merck Manual Professional Version. http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pediatrics/mental-disorders-in-children-and-adolescents/separation-anxiety-disorder. Accessed Feb. 28, 2018.

- Separation anxiety disorder. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Children-Who-Won%27t-Go-To-School-%28Separation-Anxiety%29-007.aspx. Accessed Feb. 28, 2018.

- Milrod B, et al. Childhood separation anxiety and the pathogenesis and treatment of adult anxiety. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;171:34.

- 5Bennett S, et al, Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and course. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Feb. 28, 2018.

- Bennett S, et al. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: Assessment and diagnosis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Feb. 28, 2018.

- Alvarez E, et al. Psychotherapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Feb. 28, 2018.

- Glazier Leonte K, et al. Pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Feb. 28, 2018.

- Vaughan J, et al. Separation anxiety disorder in school-age children: What health care providers should know. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2017;31:433.

- Rochester J, et al. Adult separation anxiety disorder: Accepted but little understood. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 2015;30:1.

- Whiteside SP (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. April 13, 2018.

Associated Procedures

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

- Psychotherapy

News from Mayo Clinic

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Helping your child with back-to-school anxiety Aug. 22, 2022, 04:30 p.m. CDT

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Make twice the impact

Your gift can go twice as far to advance cancer research and care!

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

The relationship between attachment and depression among college students: the mediating role of perfectionism.

- 1 School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Anhui Agricultural University, Hefei, China

- 2 College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, Edinburgh College of Arts, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Objectives: Explore the relationship between adult attachment and depression among college students, and the mechanism of perfectionism.

Study design: Questionnaire survey.

Methods: A questionnaire survey was conducted nationwide, totally 313 valid questionnaires were received. The survey collected information such as adult attachment (Adult Attachment Scale, AAS), depression (The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, CESD), and perfectionism (The Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale, FMPS). Then used SPSS26.0 to analyze the collected data.

Results: There were significant differences in perfectionism and depression between secure attachment and insecure attachment in college students. Perfectionism plays a partial mediating role in the relationship between the close-depend composite dimension, anxiety dimension of attachment and depression.

Conclusion: The closeness-dependence dimension of attachment significantly and negatively predicted perfectionism and depression; the anxiety dimension of attachment significantly and positively predicted perfectionism and depression; and perfectionism partially mediated the effect of both the closeness-dependence dimension of attachment on depression and the anxiety dimension of attachment on depression. Attachment can directly affect college students’ depression, but also indirectly through perfectionism.

Introduction

With the popularization of psychological knowledge and attention to psychological issues from all sectors of society, more and more people see the importance of mental health. Especially to young people who are at a critical stage of their development. The transition from academic to social life at university means that university students face a variety of challenges from the outside world as well as from themselves, such as establishing new interpersonal relationships, solving problems in life alone, and learning more specialized knowledge, making them more prone to psychological problems than other people. This is especially true in the context of the epidemic, which has put university students under even more pressure, not least because of depression, a psychological disorder that has become a common sight in recent years. The study of the mechanisms that lead to depression among university students is of great relevance to address and prevent depression among university students.

Attachment characteristics will also be the subject of this thesis as a necessary factor influencing interpersonal interaction patterns, intimate relationship development and other life issues that important university students need to address. Attachment is the initial connection between children and the world, and through various stages of growth and development, the attachment characteristics of adults can differ from those of children. Individuals with a tendency toward perfectionism are chronically unhappy and therefore also depressed. This study will therefore examine the correlated and internal mechanisms of attachment characteristics, perfectionism, and depression in university students.

Literature review

Depression is an affective disorder, a psychological condition characterized by low mood, hopelessness, and helplessness ( Su et al., 2011 ). Some studies have shown that the incidence of depression among university students is much higher than that of people in other stages ( Ibrahim et al., 2013 ). College students from rural areas who come to the city for study have a higher risk of depression, which may be related to the inadaptability to the learning or living environment and excessive mental or economic pressure ( He et al., 2018 ). In recent years, some scholars have also compared the detection rate of depression among university students in Guangdong before and after the epidemic, and the data showed that the detection rate of major depression was higher in 2020 than in 2022, with little difference in the detection rate of moderate depression and a higher detection rate of mild depression in 2022 ( Li et al., 2022 ).

People who are depressed often feel sad, depressed, lack interest in activities or things they used to enjoy, fail to experience pleasure in life, have reduced self-confidence, blame themselves, often feel fatigued, and are mentally inactive ( Su et al., 2011 ). Maladjustment can lead to depressive symptoms, depressive episodes, and even life-threatening behaviors such as suicide and homicide ( Li, 2018 ). Depression can also seriously affect the normal life of studying and working of university students. At present, depression is an important global public health problem, and its prevention and control are of great significance ( Wang et al., 2020 ). Therefore, we should pay attention to the study of depression among university students and explore its mechanisms in depth to obtain more effective coping strategies.

Adult attachment refers to an adult’s recollection and reproduction of their early childhood attachment experiences and current evaluation of childhood attachment experiences ( Shi and Wei, 2007 ). Attachment theory suggests that attachment enables individuals to form strong and secure affectional ties with significant others and is one of the main sources of security and a sense of control ( Liu et al., 2022 ). In contrast to infants and children who have a single object of attachment, adults have a much wider range of attachments, including parents, relatives, friends, and lovers. Attachment is a relatively stable structure that manipulates external consciousness, guides relationships with parents, and influences strategies and behaviors in subsequent relationships ( Wang et al., 2005 ). Also, different attachment characteristics and types of attachment are reflected in the individual’s unique interpersonal and intimate relationship management. Establishing and maintaining secure and satisfying social relationships is a basic human need, but the deprivation of this need affects interpersonal relationships in adulthood and may create insecure adult attachment patterns ( Mikulincer and Shaver, 2019 ).

The current available research suggests that people with insecure attachment types are at higher risk of chronic major depression ( Li et al., 2019 ), where the types of insecure attachment are preoccupied attachment and fearful attachment. Conradi and Jonge (2009) have shown that insecure attachment has a very important impact on the generation, development, and maintenance of depressed mood. A study found that individuals with insecure attachment were 3.9 times more likely to suffer from depression than individuals with secure attachment ( Shi et al., 2013 ). Studies of university students have also found that depressive status scores are significantly and positively correlated with attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety scores ( Ma et al., 2023 ).

Perfectionism has been conceptualized as a personality variable that underlies a variety of psychological difficulties. Recently, however, theorists and researchers have begun to distinguish between two distinct types of perfectionism, one a maladaptive form that results in emotional distress, and a second form that is relatively benign, perhaps even adaptive ( Bieling et al., 2004 ). Some studies have found that the development of depression are associated with negative perfectionists’ tendency to focus excessively on mistakes, self-doubt, and expectation criticism ( Zhang et al., 2013 ). It has been suggested that insecure attachment and negative perfectionism are risk factors for the formation of an obsessive-compulsive personality ( Xu et al., 2021 ).

Rice and Mirzadeh (2000) examined the relationship between attachment, perfectionism and depression and showed that subjects with insecure attachment were more likely to be maladaptive perfectionists and to experience more significant depression than those with secure attachment. Research on perfectionism and attachment has also found a significant positive correlation between attachment anxiety dimensions and negative perfectionism in adults ( Ma et al., 2010 ). A study explored the mediating role of perfectionism between attachment and depression, and found that attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance both promote the formation of negative dimensions of perfectionism, which in turn leads to depression ( Xin-Chun et al., 2013 ). A study on the relationship between attachment styles and positive/negative perfectionism, anger, and emotional regulation among college students showed that unsafe attachment styles (avoidance and conflict) can predict negative perfectionism, safe attachment types (avoidance and conflict) can predict emotional regulation, and attachment patterns can determine many behaviors, emotions, and adult relationships, which are necessary for personality growth and mental health foundations ( Nader et al., 2017 ).

Purpose and hypothesis of the study

The purpose of this study is to explore the mechanism of the relationship between attachment characteristics, depression, and perfectionism among college students.

There are three hypotheses in this study: (1) Attachment characteristics significantly predict depression and perfectionism, (2) Perfectionism significantly predicts depression, and (3) Perfectionism mediates the relationship between attachment characteristics and depression in college students.

Materials and methods

Participants.

This study used the university student population in different regions as the subjects and used the online distribution method to collect a total of 313 valid questionnaires. There were 130 male students (41.5%) and 183 female students (58.5%); 104 only children (33.2%) and 209 non-only children (66.8%); 32 first year university students; 52 s year students, 54 third year students, 140 fourth year students and 35 postgraduate students.

Adult attachment

The revised Adult Attachment Scale (AAS) ( Wu et al., 2004 ) was used to measure attachment characters. The scale was revised and developed by Wili Wu et al. and divided into three subscales of closeness, dependence, and anxiety, each with 6 questions each, for a total of 18 questions. A 5-point scale was used, in which the closeness and dependence subscales were combined into a composite closeness-dependence dimension, which was juxtaposed with the anxiety dimension, with higher scores indicating a stronger characteristic dimension. Based on the mean scores of the two dimensions there are four further types of attachment: secure, preoccupied, rejective and fearful, the latter three being insecure attachments. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the closeness-dependence dimension and the anxiety dimension of the scale were 0.774 and 0.866, respectively.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) ( Wang et al., 1999 ) was used to measure depression, it contains 20 items on a 4-point scale, scored on a scale of 0, 1, 2 and 3, with the higher the score the more depressed they are. Unlike the SDS, the CES-D is not used to clinically judge depressed patients and is therefore more appropriate for the group of university students in this study, focusing on measuring depressed state of mind. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.902.

Perfectionism

The Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMPS) ( Zi and Zhou, 2006 ) was used to measure perfectionism, developed and revised by Zi Fei et al., is divided into 27 entries and five dimensions. The dimensions are organization, concern over mistakes, parental expectations, personal standards, and doubts about action. The organization dimension is positive perfectionism, and the remaining four dimensions represent negative perfectionism. The scale is rated on a 5-point scale, with higher scores indicating a higher tendency toward perfectionism. In this study the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the total scale was 0.916 and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for each subscale were 0.834, 0.901, 0.842, 0.824 and 0.730, respectively.

Data analysis

The raw data from the returned questionnaires were processed using SPSS 26.0 software and firstly, the Harman single factor test was used to test for common method bias. The results of the test showed that the variance explained by the first common factor was 22.206%, which was below the threshold of 40%, and therefore there was no serious common method bias in this study. The mediating role of perfectionism in the relationship between attachment characteristics and depression was also tested using Model 4 in the SPSS plug-in Process v3.5.

Analysis of the characteristics of attachment, depression and perfectionism among university students

The AAS scores were transformed by combining the closeness-dependence subscale and the dependence subscale into a composite closeness-dependence dimension and calculating the mean closeness-dependence score; the anxiety subscale was used as a separate anxiety dimension and the mean anxiety score was calculated. The mean scores of the two dimensions were compared and categorized. Those with mean scores of closeness-dependence greater than 3 and mean scores of anxiety less than 3 were classified as secure attachment, while the rest were classified as insecure attachment. Insecure attachment was further classified into three different types of attachment: those with a mean score of closeness-dependence greater than 3 and a mean score of anxiety greater than 3 were preoccupied attachment, those with a mean score of closeness-dependence less than 3 and a mean score of anxiety less than 3 were rejective attachment, and those with a mean score of closeness-dependence less than 3 and a mean score of anxiety greater than 3 were fearful attachment. In this study, only 154 (49.2%) were secure attachment, while 54 (17.3%) were preoccupied attachment, 40 (12.8%) were rejective attachment and 65 (20.8%) were fearful attachment.

Of all subjects, 141 (45.05%) experienced some degree of depression.

In the current study, college students’ attachment characteristics, depression and perfectionism did not differ significantly ( p > 0.05) in the demographic variables of gender, whether they were an only child, and grade level.

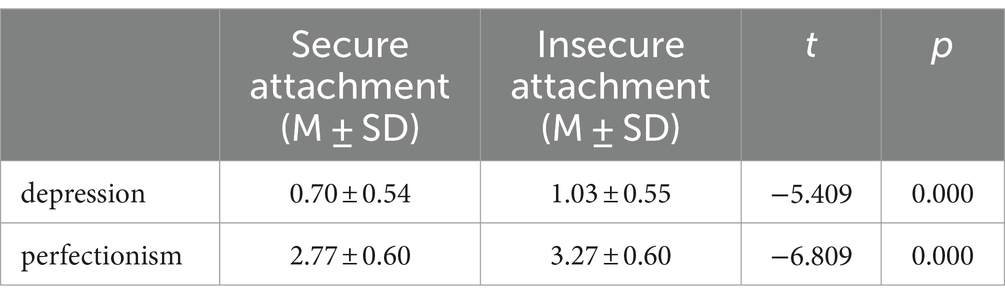

The AAS scale scores were transformed to classify the subjects into secure attachment and insecure attachment, 154 in total for the former and 159 in total for the latter, and independent samples t -tests were conducted. The results yielded significant differences ( p < 0.001) between secure attachment subjects and insecure attachment subjects on both depression and perfectionism. As shown in Table 1 , subjects with insecure attachment scored significantly higher on depression and perfectionism than those with secure attachment.

Table 1 . Analysis of differences in depression and perfectionism among college students with different attachment types ( N = 313).

Correlation analysis of attachment characteristics, depression, and perfectionism among university students

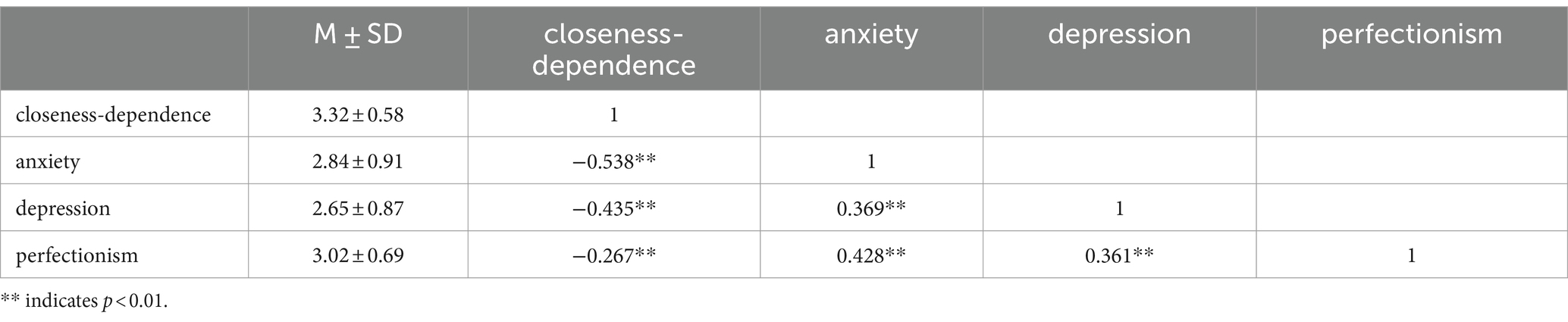

Pearson correlation analysis was conducted using SPSS 26.0 on the three variables of attachment characteristics, depression and perfectionism, and the results indicated that all three variables were correlated, which was consistent with the premise of the mediating effect test. The results of the specific correlation analysis are shown in Table 2 .

Table 2 . Correlation analysis of attachment characteristics, depression, and perfectionism among university students ( N = 313).

The closeness-dependence dimension of attachment was negatively associated with depression and perfectionism, while the anxiety dimension of attachment was positively associated with depression and perfectionism. This means that attachment closeness-dependence scores negatively predict depression and perfectionism, while attachment anxiety dimensions positively predict depression and perfectionism scores. Perfectionism also positively predicted depression.

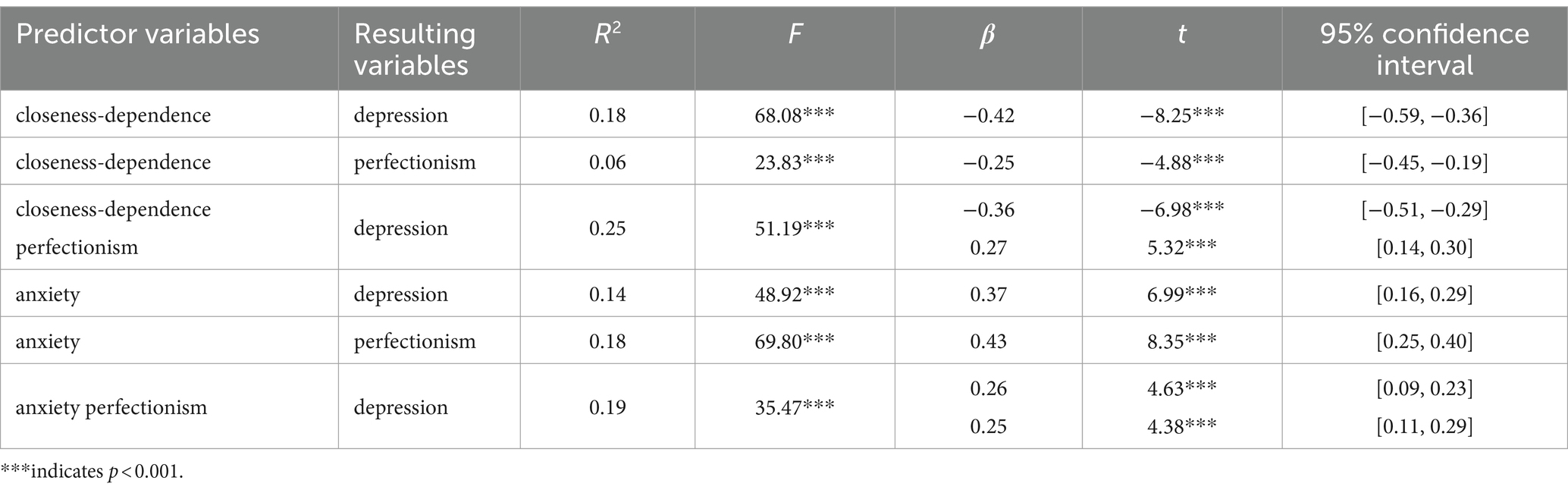

A test of the mediating role of perfectionism between attachment characteristics and depression among university students

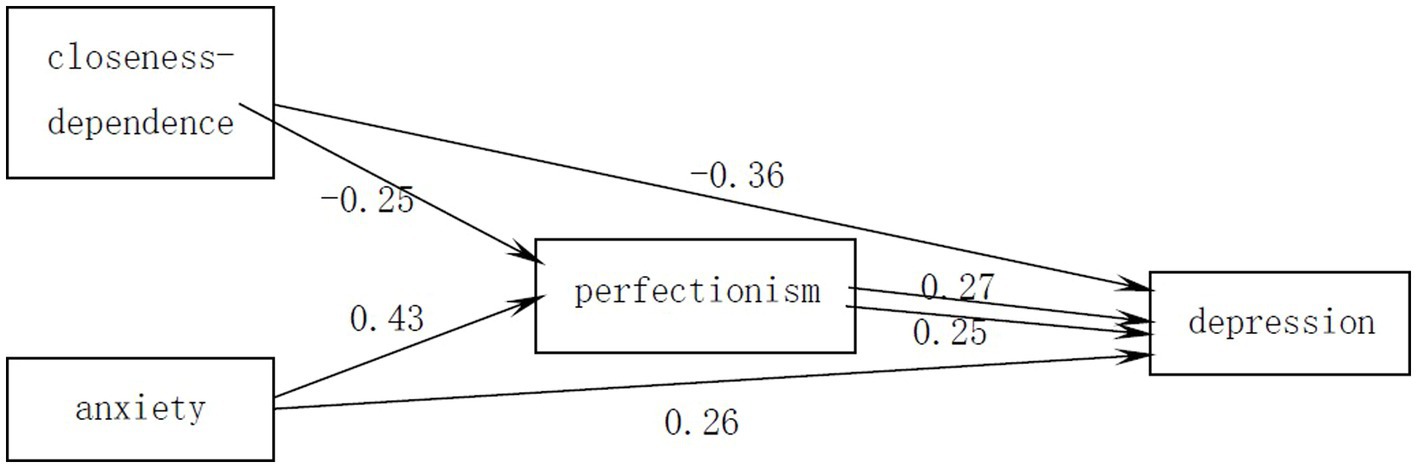

Model 4 in the SPSS plug-in Process prepared by Hayes ( Hayes, 2018 ) was used to test for the mediating effect of perfectionism and the results are shown in Table 3 . Before perfectionism was placed as a mediating variable, the closeness-dependence dimension of attachment was a significant negative predictor of depression ( β = −0.42, t = −8.25, p < 0.001), the anxiety dimension of attachment was a significant positive predictor of depression ( β = 0.37, t = 6.99, p < 0.001). The closeness- dependence dimension of attachment was a significant negative predictor of perfectionism ( β = −0.25, t = −4.88, p < 0.001) and the anxiety dimension of attachment was a significant positive predictor of perfectionism ( β = 0.43, t = 8.35, p < 0.001). When perfectionism was added as a mediating variable, the closeness-dependence dimension of attachment was still a significant negative predictor of depression ( β = −0.36, t = −6.98, p < 0.001) The perfectionism dimension of attachment was also a significant positive predictor of depression ( β = 0.27, t = 5.32, p < 0.001); after adding perfectionism as a mediating variable, the anxiety dimension of attachment was still a significant positive predictor of depression ( β = 0.26, t = 4.63, p < 0.001), and perfectionism was also a significant positive predictor of depression ( β = 0.25, t = 4.38, p < 0.001). The results of the analysis of the mediating effect can be represented in Figure 1 .

Table 3 . Mediating role of perfectionism between attachment and depression ( N = 313).

Figure 1 . Graph showing the results of the test for the mediating role of perfectionism.

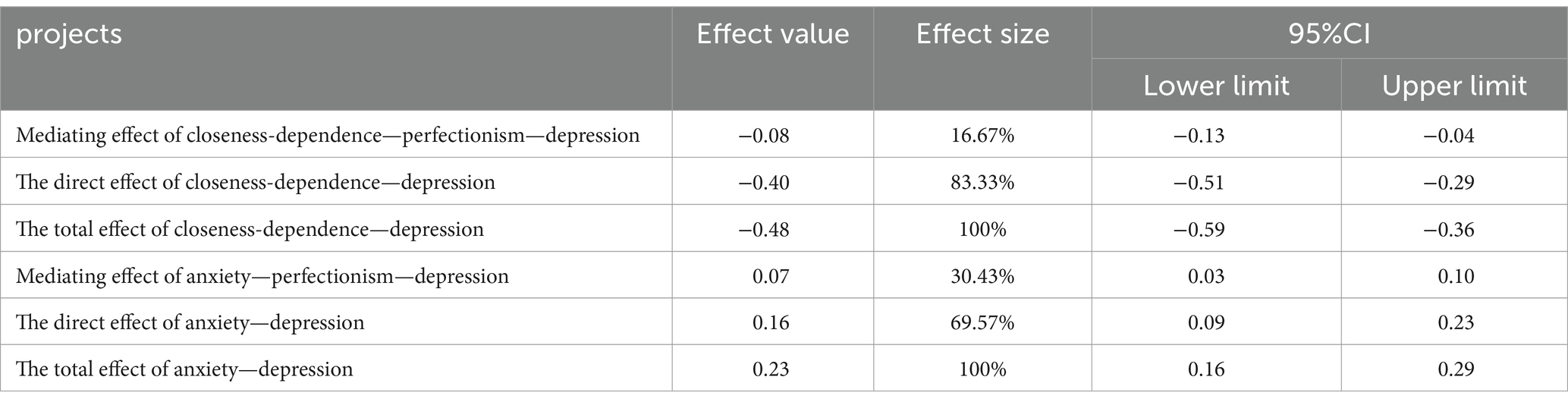

The mediating effects of the attachment closeness-dependence dimension and the anxiety dimension with their respective effect sizes are shown in Table 4 .

Table 4 . Attachment mediated effects and effect sizes.

The Bootstrap 95% confidence interval for the direct effect of the closeness-dependence dimension of attachment on depression was [−0.51, −0.29], excluding 0, indicating that its direct effect was significant; the Bootstrap 95% confidence interval for the mediating effect of perfectionism between the closeness-dependence dimension of attachment and depression was [−0.13, −0.04], excluding 0, indicating that the mediating effect of perfectionism was significant. The Bootstrap 95% confidence interval for the total effect of attachment closeness -dependence dimension on depression was [−0.59, −0.36], excluding 0, indicating a significant total effect and an effect value of −0.48. Thus, it can be suggested that perfectionism partially mediates the relationship between attachment closeness-dependence dimension and depression, with a mediating effect of 16.67%.

The Bootstrap 95% confidence interval for the direct effect of the anxiety dimension of attachment on depression was [0.09, 0.23], which did not contain 0, indicating a significant direct effect; the Bootstrap 95% confidence interval for the mediating effect of perfectionism between the anxiety dimension of attachment and depression was [0.03, 0.10], which did not contain 0, indicating a significant mediating effect of perfectionism between the anxiety dimension of attachment and depression. The Bootstrap 95% confidence interval for the total effect of attachment anxiety dimension on depression was [0.16, 0.29], excluding 0, indicating a significant total effect with an effect value of 0.23. It can therefore be shown that perfectionism partially mediates between attachment anxiety dimension and depression, with a mediating effect of 30.43%.

Status of attachment characteristics, perfectionism, and depression among university students

In this study, a total of 45.05% of the university students who participated in the questionnaire experienced some degree of depression, and there were no significant differences in the demographic variables of depression scores in gender, whether they were an only child, or grade level. This also suggests, to some extent, that depression is somewhat prevalent in the university population. In addition, subjects with insecure attachment types were more likely to experience depressive mood than those with secure attachment types. This is in line with the findings of some scholars on adolescent depression and parent–child attachment: secure parent–child attachment reduces the risk of adolescent depression ( Lai et al., 2022 ). The need for excessive attention and commitment is not always met, leading to severe feelings of loss, further doubts, and anxiety about the safety of the relationship ( Shaver et al., 2005 ). College students with insecure attachment types experience more abuse, neglect, separation, and loss in their early years of interaction with their primary caregivers, and such early adverse experiences are often associated with depression ( Whiffen et al., 1999 ). It also points to the important role that attachment plays in the development of adolescents and even university students.

The mechanism by which adult attachment affects depression lies in the internal negative self-model, i.e., the negative evaluation of the self is an important factor in forming depression ( Yang, 2005 ). Individuals with high scores on the anxiety dimension of attachment often fear that the attachment partner will leave them, and one of the reasons for this is a lack of self-confidence and doubt. Because of their negative perceptions of themselves, these groups do not see themselves as worthy of love and therefore feel insecure that they may be abandoned at any time, even if they have established an intimate relationship. Insecure attachment individuals are more likely to have problems in making emotional connections with external objects than secure attachment individuals, e.g., individuals with preoccupied attachment (high closeness-dependence, high anxiety) have a stronger desire to connect with others and a high level of insecurity about existing connections, so they often seek approval from others, are completely focused on others, are dependent on others, easily lose themselves and are in constant fear of relationship breakdown ( Zhang, 2021 ).

In this study, perfectionism was also scored significantly higher in insecure attachment individuals than in secure attachment individuals. Some scholars believe that doing things perfectly and not making mistakes is a means of survival for children who grow up in harsh, punishing, harsh or even abusive families to avoid unnecessary harm or enhance their control over uncertain environments ( Flett et al., 2012 ). Maladaptive perfectionism has overly idealistic expectations and ideas about real life, thinking that they can easily achieve success or achieve goals, often ignoring objective conditions, and often feeling lost and inadequate in the process ( Rice and Ashby, 2007 ). One of the characteristics of perfectionism is that they always set much higher goals for themselves and too difficult to achieve them, so perfectionistic individuals are chronically unfulfilled and dissatisfied with themselves. The insecure attachment individuals’ negative evaluation of self also contributes to the pursuit of high goals. At the same time, prolonged failure to achieve goals can lead to new negative evaluations of the self, which are likely to be accompanied by devaluation of the self, forming a pattern of internal evaluations that can lead to depression. Researcher found that perfectionists’ rigid core thinking produces low levels of unconditional self-acceptance, accompanied by low self-liking and a low sense of self-competence, which in turn leads to depression ( Scott, 2007 ). The Beck depression model suggests that negative notions of self and others increase an individual’s susceptibility to depression ( Kernis et al., 1991 ). It has been shown that maladaptive perfectionist individuals act with excessive consideration for the correctness of their behavior, hesitate to act and fear failure, and are more likely to adopt negative coping styles in stressful situations, leading to anxiety, depression, and other negative emotions ( Zhang et al., 2014 ).

The mediating role of perfectionism between attachment and depression

The results of the analysis of the mediating role of perfectionism found that the direct effects of the closeness-dependence dimension and the anxiety dimension on depression were significantly weakened after perfectionism was introduced between attachment characteristics and depression as the mediated variable, indicating that perfectionism partially mediates the relationship between both the closeness- dependence composite dimension of adult attachment and the anxiety dimension and depression, meaning that university students’ attachment can directly affect their depression levels, as well as indirectly affect depression levels by influencing perfectionist tendencies.

The closeness-dependence dimension of attachment reflects the degree to which individuals are comfortable in intimate relationships and assess whether they have someone to rely on when needed ( Zhang et al., 2014 ). Individuals with higher levels of comfort in intimate relationships are more likely to feel satisfied and therefore less likely to have negative evaluations of themselves. As shown in the study, scores on the closeness-dependence dimension of attachment were significantly and negatively correlated with scores on perfectionism and depression. It has been found that individuals with higher levels of attachment anxiety have lower levels of emotion expression ( Yao and Zhao, 2021 ), and that the prolonged lack of emotional expression can easily lead to depression. Insecure attachment individuals have negative attitudes toward interpersonal interactions and have less social support than other people, making it more difficult for them to get out of difficult situations when they have negative life events or encounter difficulties and setbacks.

The results of this study show that the closeness-dependence dimension of attachment is negatively related to perfectionism, while the anxiety dimension of attachment is positively related to perfectionism, meaning that individuals with low closeness-dependence and high anxiety in intimate relationships, i.e., Those who do not adapt well to intimate relationships or who have not experienced success in previous intimate relationships, are prone to perfectionism. Perfectionists are also overly concerned with their own behavior and performance. This group believes that they must be complimented and praised by others, and they show a desire for attention and a fear of being rejected by others ( Stoeber et al., 2017 ). This is why these people tend to experience disappointment in their daily lives and in their interpersonal interactions, resulting in a decline in self-confidence, a decrease in interest and depression.

Implications of the research

This study investigates the mechanisms by which attachment affects depression in university students and has implications for the prevention and intervention of depression in university students. Firstly, it can draw attention to the importance of building secure attachments and creating a good family environment from early childhood to avoid the risk of depression early. At the same time, for attachment characteristics that are difficult to change early in the formative years, it is possible to intervene in depression by changing the mediating variables in this study, guiding individuals to set reasonable goals, and taking more encouraging measures to improve their self-esteem.

Limitations of the research

This study also has certain limitations, firstly, from the research method, the method of questionnaire collection adopted in this study is online collection method, thus there are limitations in controlling the confounding variables. Moreover, the sample size of this study is still not sufficiently random in terms of grade and major, so there may be some errors. Finally, as perfectionism only partially mediates the results from this study and has a low effect size, there are many potential influences in related areas that need to be further explored.

There were significant differences in perfectionism and depression between secure attachment and insecure attachment in university students, with insecure attachment individuals scoring higher in perfectionism and depression than secure attachment individuals.

The closeness-dependence dimension of attachment significantly and negatively predicted perfectionism and depression; the anxiety dimension of attachment significantly and positively predicted perfectionism and depression; and perfectionism partially mediated the effect of both the closeness-dependence dimension of attachment on depression and the anxiety dimension of attachment on depression.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Anhui Agriculture University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

FF: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis. JW: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Methodology.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Bieling, P. J., Israeli, A. L., and Antony, M. M. (2004). Is perfectionism good, bad, or both? Examining models of the perfectionism construct. Pers. Individ. Differ. 36, 1373–1385. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00235-6

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Conradi, H. J., and Jonge, P. D. (2009). Recurrent depression and the role of adult attachment: a prospective and a retrospective study. J. Affect. Disord. 116, 93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.10.027

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Flett, G. L., Druckman, T., Hewitt, P. L., and Wekerle, C. (2012). Perfectionism, coping, social support, and depression in maltreated adolescents. J. Ration. Emot. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 30, 118–131. doi: 10.1007/s10942-011-0132-6

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach . New York: Guilford Press

Google Scholar

He, H., Zeng, Q. L., and Wang, H. S. Q. (2018). Analysis of the influence of left-behind experience on the depression status of rural college students with household registration. Chin. J. Health Educ. 34, 973–978.

Ibrahim, A., Kelly, S., Adams, C., and Glazebrook, C. (2013). A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. J. Psychiatr. Res. 47, 391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.015

Kernis, M., Grannemann, B., and Mathis, L. (1991). Stability of self-esteem as a moderator of the relation between level of self-esteem and depression. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 61, 80–84. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.80

Lai, Z. Z., Wu, C. Y., Wang, C. C., et al. (2022). The effect of paternity attachment on adolescent depression: a moderated mediation model. Chinese psychological association . Xin Xiang: Henan Normal University Press.

Li, A. L.. (2018). The relationship among undergraduate students’ hardy personality, thinking style, and depression . China West Normal University, Nanchong.

Li, Z., Huang, Z. W., Yang, F. C., et al. (2019). A review of mental health theory: from the perspective of adult attachment. J. Chin. Soc. Med. 36, 146–149.

Li, Y. P., Zhang, G. Y., and Chen, R. J. (2022). Investigation and countermeasures on the depression of college students after the outbreak of COVID-19. J. Psychol.Month. 17, 207–216. doi: 10.19738/j.cnki.psy.2022.23.066

Liu, Y., Liu, Z. H., Duan, H., Chen, G., Liu, W., et al. (2022). The influence of insecure attachment on academic procrastination: the mediating role of perfectionism and rumination. Psychology 10, 407–414. doi: 10.16842/j.cnki.issn2095-5588.2022.07.003

Ma, H. X., Gao, Z. H., Li, J. M., et al. (2010). Relationship between perfectionism and adult attachment of university students. J. Chin. Health Psychol. 18, 717–719. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2010.06.027

Ma, Q., Qin, L., and Cao, W. (2023). Relationship between depression, attachment and social support of college students. J. Chin. Health Psychol. 31, 294–298. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2023.02.023

Mikulincer, M., and Shaver, P. R. (2019). Attachment orientations and emotion regulation. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 25, 6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.006

Nader, H., Hadeis, H., and Usha, B. (2017). The relationship between attachment styles and positive/negative perfectionism, anger, and emotional adjustment among students. Knowl. Res. Appl. Psychol. 17, 11–20.

Rice, K. G., and Ashby, J. S. (2007). An efficient method for classifying perfectionists. J. Couns. Psychol. 54, 72–85. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.54.1.72

Rice, K. G., and Mirzadeh, S. A. (2000). Perfectionism, attachment, and adjustment. J. Couns. Psychol. 47, 238–250. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.47.2.238

Scott, J. (2007). The effect of perfectionism and unconditional self-acceptance on depression. J. Ration. Emot. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 25, 35–64. doi: 10.1007/s10942-006-0032-3

Shaver, P. R., Schachner, D. A., and Mikulincer, M. (2005). Attachment style, excessive reassurance seeking, relationship processes, and depression. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 31, 343–359. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271709

Shi, Y. H., and Wei, P. (2007). A study on the relationship between repression and adult attachment of college students. J. Chin. Health Psychol. 12, 1066–1067. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2007.12.034

Shi, Z. M., Yang, Q., Xue, Y., et al. (2013). A study of adult attachment types in patients with depression. J. Chin. Clin. Psychol. 21, 616–619.

Stoeber, J., Noland, A. B., Mawenu, T. W. N., Henderson, T. M., and Kent, D. N. P. (2017). Perfectionism, social disconnection, and interpersonal hostility: not all perfectionists don't play nicely with others. Personal. Individ. Differ. 119, 112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.07.008

Su, Z. X., Kang, Y., and Li, J. M. (2011). Study on adolescent depression and the relevant risk factors. J. Health Psychol. 19, 629–631. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2011.05.024

Wang, M. Y., Liu, J., Wu, X., et al. (2020). A meta-analysis of the prevalence of depression in Chinese college students in recent 10 years. J. Hainan Med. Univ. 26, 686–699.

Wang, Z. Y., Liu, Y. Z., and Yang, Y. (2005). An overview and discussion of the research on the internal working mode of attachment. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 5, 629–639.

Wang, X. D., Wang, X. L., and Ma, H.. (1999). Handbook of China mental health assessment scale . Beijing: China Mental Health Journal Press. 200–202.

Whiffen, V. E., Judd, M. E., and Aube, J. A. (1999). Intimate relationships moderate the association between childhood sexual abuse and depression. J. Interpers. Violence 14, 940–954. doi: 10.1177/088626099014009002

Wu, W. L., Zhang, W., and Liu, X. H. (2004). The reliability and validity of adult attachment scale (AAS-1996 revised edition): a report on its application in China. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 35, 536–538.

Xin-Chun, L., Xiao-Kun, Z., Jing-Jing, D., and Yong-Ling, L. I. (2013). A study on mediating effect of perfectionism between attachment and depression. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 21, 658–661. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2013.04.005

Xu, W., Liu, Q., Chu, J., et al. (2021). The effect of insecure attachment and negative perfectionism on the relationship between family environment and obsessive-compulsive personality. J. Chin. Clin. Psychol. 29, 328–332. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2021.02.022

Yang, J. (2005). Explorative Researeh on adult attachment and its influence upon depression . East China Normal University, Shanghai.

Yao, X. Y., and Zhao, Y. P. (2021). Relationship between adult attachment and mobile phone dependence among college student: the mediating role of emotional expression. J. Psychol. Techn. Appl. 9, 522–529. doi: 10.16842/j.cnki.issn2095-5588.2021.09.002

Zhang, Q. (2021). The influence of types of adult attachment on interpersonal communication. J. Sci. Educ. Lit. 550, 148–150. doi: 10.16871/j.cnki.kjwha.2021.12.046

Zhang, B., Qiu, Z. Y., Jiang, H. B., et al. (2014). Coping styles as a mediator between perfectionism and depression in Chinese college students. J. Nanjing Med. Univ. 14, 319–323. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2018.03.039

Zhang, B., Zhou, X. T., and Cai, T. S. (2013). A study on the relationship between perfectionism personality traits and susceptibility to depression. J. Med. Philos. 34, 50–52.

Zi, F., and Zhou, X. (2006). The Chinese frost multidimensional perfectionism scale: an examination of its reliability and validity. J. Chin. Clin. Med. 14, 560–563.

Keywords: collge students, attachment, depression, perfectionism, medating effects

Citation: Fang F and Wang J (2024) The relationship between attachment and depression among college students: the mediating role of perfectionism. Front. Psychol . 15:1352094. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1352094

Received: 16 December 2023; Accepted: 02 April 2024; Published: 15 April 2024.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2024 Fang and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jingwen Wang, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Children's Separation Anxiety Scale (CSAS): Psychometric Properties

Xavier méndez.

1 Department of Personality, Psychological Assessment and Treatment, University of Murcia, Murcia, Spain

José P. Espada

2 Department of Health Psychology, Miguel Hernández University, Elche, Spain

Mireia Orgilés

Luis m. llavona.

3 Department of Personality, Psychological Assessment and Treatment (Clinical Psychology), Complutense University, Madrid, Spain

José M. García-Fernández

4 Department of Developmental Psychology and Teaching, University of Alicante, Alicante, Spain

Conceived and designed the experiments: XM JPE MO LML JMG. Performed the experiments: XM JPE MO LML JMG. Analyzed the data: XM JPE MO LML JMG. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: XM JPE MO LML JMG. Wrote the paper: XM JPE MO LML JMG.

This study describes the psychometric properties of the Children's Separation Anxiety Scale (CSAS), which assesses separation anxiety symptoms in childhood. Participants in Study 1 were 1,908 schoolchildren aged between 8 and 11. Exploratory factor analysis identified four factors: worry about separation, distress from separation, opposition to separation, and calm at separation, which explained 46.91% of the variance. In Study 2, 6,016 children aged 8–11 participated. The factor model in Study 1 was validated by confirmatory factor analysis. The internal consistency (α = 0.82) and temporal stability ( r = 0.83) of the instrument were good. The convergent and discriminant validity were evaluated by means of correlations with other measures of separation anxiety, childhood anxiety, depression and anger. Sensitivity of the scale was 85% and its specificity, 95%. The results support the reliability and validity of the CSAS.

Introduction

Separation anxiety disorder (SAD) in children is characterized by excessive and inappropriate anxiety for the child's stage of development, and which he or she experiences on being separated from attachment figures – generally the parents – or spending time outside his or her home [1] . This disproportionate anxiety manifests itself in distress, worry and resistance to or rejection of the separation. Prevalence of SAD is 3.9% in childhood (6–12 years) and 2.6% in adolescence (13–18 years), according to two meta-analyses carried out with 13 and 26 epidemiological studies, respectively [2] . SAD and some types of specific phobia, such as those related to animals, are the anxiety disorders with earliest age of onset, the majority of cases emerging prior to age 12 [3] . The presence of SAD in childhood predicts this same disorder in adolescence (age 13–19) [4] . SAD is a strong risk factor (78.6%) for the development of psychopathology in young adulthood (age 19–30), so that the diagnosis, assessment and treatment of children with SAD are relevant for preventing the appearance of disorders such as panic and depression [5] .

Clinical diagnosis and assessment aspire to collect as much information as possible at the least possible cost in time and money, and in effort for the child, parents and professionals. Optimization of assessment efficiency involves the avoidance of extreme positions. On the one hand, excessively thorough assessment leads to fatigue and to the risk of loss of precision and early abandonment of the therapeutic relation. On the other, very brief assessment is of little use for planning treatment, and involves risks such as the omission of relevant data and premature therapeutic decisions. In the framework of multi-method assessment, self-report rating scales are widely used, together with structured interviews, as they are easy to apply, fill out and evaluate. They are especially useful from the age of 7 onwards, when the child has acquired sufficient reading ability and self-assessment skills. There are general self-reports for assessing the different childhood anxiety disorders, including SAD, such as the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) [6] or the Spence Children's Anxiety Scale (SCAS) [7] . The comprehensive application of these instruments, which include more than 40 items, is of great use for screening in epidemiological studies, but may be unnecessary and excessive in clinical cases of SAD, detected via interview; at the same time, application of just the SAD scales, with their less than 10 items, may be insufficient for assessing the full spectrum of symptoms and drawing up a treatment plan. Therefore, the construction and validation of self-reports for the specific assessment of SAD is relevant. There are three self-reports of this type: the Separation Anxiety Assessment Scale (SAAS) [8] , the Separation Anxiety Avoidance Inventory (SAAI) [9] , and the Separation Anxiety Scale for Children (SASC) [10] . The SAAS has the disadvantage that its psychometric properties have not yet been published, whilst the SAAI focuses exclusively on avoidant behaviors, neglecting subjective aspects, such as distress and worry, both characteristic of SAD. Furthermore, these two self-reports assess separation anxiety in both childhood and adolescence at the same time (6–17 and 4–15 years, respectively), despite the fact that the symptoms vary with age. This is a problematic aspect, as it is inappropriate, for example, to present a four-year-old with item 2 of the SAAI, “Because I am anxious, I avoid being at home alone in the evening”, or a 17-year-old with item 4 of the SAAS, “How often are you afraid to be left at home with a babysitter?”

The SASC was developed for children aged 8 to 11 on the basis of the three-dimensional theory of anxiety [11] , which, when applied to separation anxiety, postulates three inter-related components: a) cognitive , or worry that something bad will happen to the child and/or to his/her parents, b) psychophysiological , or distress resulting from the feelings of distress generated by excessive vegetative activation, and c) behavioral , or opposition to being separated from one's parents and/or away from home. The confirmatory factor analysis confirmed that the model of three correlated factors showed the best fit to the data, corroborating the factors Worry about separation and Distress from separation ; however, contrary to what was expected, the third factor was not opposition, but rather Calm at separation . The child's calm at separation from parents can be interpreted a) cognitively, as the absence of worry – for example, I don't think my parents will have an accident or get sick; b) psychophysiologically, as the absence of distress – for example, I don't have stomach-ache or feel like crying; c) behaviorally, as the absence of opposition – for example, I don't do things to check whether my parents are OK or to try and be with them; d) positively, as the presence of calmness – for example, I feel calm/OK when my parents go away on a trip. The factor Calm at separation is problematic not only from the theoretical point of view, but also methodologically, as the internal consistency coefficient (Cronbach's alpha) was low (0.63). Moreover, the SASC has other methodological limitations: explained variance was just 32.80%, concurrent validity was calculated solely with two self-reports – one of anxiety and another of fears at school –, and neither its sensitivity nor its specificity was reported.

At a theoretical level it is interesting to explore whether opposition is a dimension of separation anxiety and whether calm is a positive factor that cannot be reduced to the mere absence of worry, distress and/or opposition. It is also important to have access to a psychometrically satisfactory instrument that addresses the deficiencies of the SASC – specifically, one that improves the construct validity by increasing the percentage of explained variance, that increases the convergent and discriminant validity on including measures of SAD, child anxiety, depression and anger, and that analyzes the structural validity by means of the sensitivity and specificity. Given the lack of a specific self-report rating scale for childhood SAD with adequate psychometric properties, which assesses the varied symptomatology of this disorder rather than focusing on just a single aspect of it, such as avoidant behavior, the general objectives of this study, taking as a starting point the SASC, were to develop (Study 1) and validate (Study 2) a self-report instrument, the Children's Separation Anxiety Scale (CSAS). In Study 1 we carry out an exploratory factor analysis with a bank of 40 items: the 26 from the original study [10] plus 14 new items from a pilot study. In Study 2 we calculate the validity, reliability, sensitivity and specificity of the CSAS.

Study 1: Exploratory Factor Analysis

Ethics statement.

The authors state that their research, approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Murcia (Spain), has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. The education authorities were informed of the study goals, and authorization was requested. Once such authorization had been obtained, the researchers interviewed the head teachers and the school counselors, informing them verbally and in writing about the aim of the study, so as to obtain their permission and encourage their cooperation. Finally, parents were informed by letter and requested to provide written consent for their children to participate in the study. The written parental consent was provided for all minors participating.

Participants

Random cluster sampling was carried out in two provinces in central and southern Spain, respectively. Primary units were provincial districts, secondary units were schools, and tertiary units were classrooms. We recruited 2,005 children from primary school grades 3 to 6 at 19 schools. A total of 97 (4.84%) were excluded due to errors or omissions in their responses, because their parents failed to provide informed consent, or because they were immigrants whose level of Spanish was too low. The sample was made up of 1,908 schoolchildren with a mean age of 9.61 ( SD = 1.11). The chi-squared test for homogeneity of the distribution of frequencies indicated that there were no statistically significant differences between the eight groups of gender x age in Table 1 (χ 2 = 0.48, df = 3, p = 0.92). Participants covered a wide range of socio-economic status, which was determined according to the school's type (public, grant-assisted private or private) and location (city, small town/village or village/rural).

The researchers generated twenty new separation anxiety items that were evaluated with the same procedure as in the original study [10] . A pilot study was carried out with a random sample of 103 children aged 8 to 11 ( M = 9.37, SD = 1.06) of both genders (54.43% girls). Six items were eliminated, a) at the suggestion of twelve experts in the psychopathology of development with broad clinical experience, and who acted as judges, b) because participants found them difficult to understand, and c) due to low item-test correlation. Examples of the eliminated items are “Do you refuse to sleep at a friend's house?” and “Do you forget your mom or dad when you go to an after-school activity?” The remaining 14 new items were added to the 26 original SASC items to make up the bank of 40 items employed in this study.

Participants responded to the bank of 40 separation anxiety items in the classroom and within normal class time. The researchers' assistants read the instructions aloud, provided individual help where necessary, and made sure that the pupils answered their own questions independently. In order to avoid bias, neither the assessors nor the participants were aware of the study's aims until the instruments had been handed in and processed.

We administered the bank of 40 separation anxiety items, made up of the 26 original items of the SASC [10] plus the 14 new items of the pilot study, which evaluates childhood separation anxiety by means of a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never or almost never) to 5 (always or almost always).

Data Analysis

The underlying structure of the CSAS was identified by means of an iterative principal axis factor analysis with oblimin rotation because the factors were correlated. The data analysis was carried out with the SPSS statistics package, version 20.0.

The criteria for obtaining the factorial solution were: a) to retain factors with eigenvalues higher than 1 (Kaiser criterion), b) to assign to each factor the items that loaded higher than 0.40, and c) to include at least five items in each factor. Twenty items were removed: nine because the saturation was under 0.40 (items 1, 3, 4, 6, 8, 13, 20, 22, and 32) and eleven because the corresponding factor, which explained less than five per cent of the variance, included fewer than five items (items 7, 9, 10, 19, 30, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, and 40). Four factors, each with five items, were obtained, explaining 46.91% of the variance. Factor 1, Worry about separation (items 21, 25, 28, 31, and 39), explained 13.91% of the variance. This is the cognitive component of anxiety, and refers to worry that something bad might happen to the child and/or to his/her parents. Factor 2, Distress from separation (items 15, 16, 23, 26, and 29), explains 12.32% of the variance. This is the psychophysiological component, which includes uncomfortable feelings, such as nausea or stomach ache, and the negative feelings separation can generate, such as wanting to cry. Factor 3, Opposition to separation (items 2, 5, 12, 14, and 18), explained 10.66% of the variance. This is the behavioral component, which refers to reactions for avoiding separation from the parents. Factor 4, Calm at separation (items 11, 17, 24, 27, and 33), explained 10.02% of the variance, and is the positive component, which reflects confidence in the child on being separated from his or her parents and/or on being away from home. Table 1 shows the CSAS factor structure.

Study 2: Confirmatory Factor Analysis, Reliability and Validity

In a similar way to Study 1, a random cluster sampling was carried out in two provinces of southeastern Spain. A total of 6,302 schoolchildren were recruited, from primary school grades 3 to 6, and 72 schools. In all, 286 (4.54%) were excluded for reasons similar to those reported in the previous study. Thus, the sample was made up of 6,016 children with a mean age of 9.59 ( SD = 1.12). The chi-squared test for homogeneity of the distribution of frequencies highlighted the absence of statistically significant differences between the eight groups of gender x age in Table 2 (χ 2 = 5.33, df = 3, p = 0.15). Socio-economic status of the participants was similar to that of those in Study 1.

Test-retest reliability was calculated with 1,926 children randomly selected from the sample, who responded to the CSAS again four weeks later. Diagnostic validity was calculated with 398 children also randomly selected from the sample, and who were assessed individually by means of a semi-structured interview based on the DSM-IV criteria.

Seventeen children were diagnosed with SAD through the ADIS-IV-C interview, accounting for 4.27%. The numbers of cases in the subsample used for this analysis ( n = 398) were 8 children aged 8 (7.92%), 4 aged 9 (3.88%), 3 aged 10 (3.12%) and 2 aged 11 (2.04%). As regards the gender variable, 7 were boys (3.55%) and 10 were girls (4.98%).

The processes of informing the education authorities, the head teachers and the parents, as well as those of requesting authorization and informed consent and administering the self-reports in the classroom, were similar to those described in Study 1.

With a view to avoiding too much disruption of the pupils' normal curriculum, and also to minimizing errors caused by fatigue, administration time of the self-reports was restricted to one hour. Thus, each participant responded, in the classroom situation, to just three instruments: I) the CSAS; II) one of the following, more extensive, self-reports (more than 30 items): the SAAS [8] , the SCARED [6] , the SCAS [7] , or the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC) [12] ; and III) one of the following, briefer, self-reports (less than 30 items): the Childhood Anxiety Sensitivity Index (CASI) [13] , the School Fears Survey Scale (SFSS) [14] , the Children's Depression Inventory (CDI) [15] or the State–Trait Anger Expression Inventory for Children and Adolescents (STAXI-CA) [16] . Thus, all participants filled out the CSAS, while each one of the eight self-reports was filled out by approximately a quarter of them (see n for each self-report in Table 3 ). The self-reports and the order of administration were assigned at random to each classroom group (20–25 pupils).

With the aim of analyzing in detail the convergent and discriminant validity of the CSAS, we used a wide range of self-reports to assess variables related to separation anxiety.

CSAS. We administered the scale of 20 items resulting from Study 1, which assesses the frequency of separation anxiety symptoms on a 5-point scale: never or almost never (1), sometimes (2), often (3), very often (4), always or almost always (5).

SAAS [8] . We employed the Spanish translation made by the researchers, with the authors' permission, using the back-translation method [17] . It consists of 34 items whose response options are: never (1), sometimes (2), most of the time (3), and all the time (4). Total score on the scale is obtained by summing the four key symptom dimensions: fear of being alone, fear of abandonment, somatic complaints/fear of physical illness, and worry about calamitous events, plus the safety signals index and frequency of calamitous events (never, once, twice, three times or more). The subscales consist of 5 items, except for the safety signals index, which consists of 9 items. Internal consistency of the scale for the present study (Cronbach's alpha) was 0.88.

SCARED [6] . We applied the Spanish translation for children aged 8 to 12 [18] . The original instrument contains 41 items grouped in five subscales that assess different childhood anxiety disorders: somatic/panic (13 items), general anxiety (9 items), separation anxiety (8 items), social phobia (7 items), and school phobia (4 items). Symptom frequency is assessed by means of a three-point scale: 0 (almost never), 1 (sometimes), 2 (often). Internal consistency of the present sample was good (Cronbach's alpha = 0.90).

SCAS [7] . We employed the Spanish adaptation for use with children aged 8 to 12 [19] , which includes 38 items related to six childhood anxiety disorders: generalized anxiety disorder (6 items), panic attack/agoraphobia (9 items), social phobia (6 items), separation anxiety disorder (6 items), obsessive-compulsive disorder (6 items), and physical injury fears (5 items), plus 6 positive items that act as “fillers”, to offset the tendency to respond negatively. Frequency of each symptom is measured using a 4-point scale: never (0), sometimes (1), often (2), always (3). Internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) of the complete scale in the present study was 0.88.

STAIC [12] . We applied the Spanish adaptation for children and adolescents aged 9 to 15 [20] . This instrument is one of the most well studied and commonly used general anxiety self-report rating scales. It is composed of two 20-item subscales with three response alternatives (1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often), which evaluate current level of anxiety (state) and chronic symptoms of anxiety (trait). Internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) for the present sample was 0.87 for both state anxiety and trait anxiety.

CASI [13] . We applied the Spanish adaptation for children aged 9 to 11 [21] . Sensitivity to anxiety is the fear of the anxiety symptoms produced by the belief that the feelings of anxiety are dangerous or harmful. It is considered to predispose the individual to the development of anxiety disorders. The instrument consists of 18 items for assessing this risk factor with a 3-point Likert-type scale (1 = none, 2 = some, 3 = a lot), e.g. “It scares me when I feel like I am going to throw up”. The internal consistency coefficient for the sample in our study was 0.85.

SFSS [14] . This was designed for children aged 8 to 11. The 25 items on school fears are assessed via a three-point scale: 0 (not at all), 1 (a little), 2 (a lot). The scale includes fears related to SAD, such as “Separating from parents to go to school”, and others unrelated to the disorder, such as “Getting bad exam marks”. Persistent refusal to go to school because of fear of separation is one of the characteristics of SAD. Internal consistency of this instrument was good (α = 0.90).

CDI [15] . We used the Spanish adaptation for children and adolescents aged 7 to 15 [22] . Depressed mood is often associated with SAD. The CDI is the self-report most widely used for assessing depressive symptomatology in childhood. It consists of 27 items with three response options, and the child must choose from them the one that best describes him or her in the last two weeks. For the present sample the internal consistency was very high (Cronbach's alpha = 0.95).

STAXI-CA. Del Barrio and Aluja [16] adapted the STAXI-2 [23] for children and adolescents aged 8 to 17. This instrument consists of 32 items in four 8-item subscales: state anger, trait anger, expression of anger, and control of anger. The child marks the option that best describes him/her: 1 (a little), 2 (quite a lot), 3 (a lot). In our study we used only the subscales state anger (α = 0.93) and trait anger (α = 0.80). The relation with separation anxiety is expected to be lower than with state anxiety and with trait anxiety.

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children for DSM-IV (ADIS-IV-C) [24] , Spanish adaptation [25] . This is a semi-structured interview, based on the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-IV, and which is widely used with children and adolescents aged 7 to 17. It contains modules on all anxiety disorders, including SAD and school refusal, as well as dysthymia, major depressive disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, and oppositional-defiant disorder. Each diagnosis is completed with a severity assessment made by the clinician using a nine-point scale, from 0 (none) to 8 (very severely disturbing/disabling). Twenty-five psychologists with Masters qualifications in child psychopathology and clinical psychology received intensive training in the use of the ADIS-IV-C with the help of a specific manual [26] . In the present sample, the kappa coefficient obtained for SAD was 1 (perfect agreement).

The structure of the CSAS obtained in Study 1 was examined by means of confirmatory factor analysis. Internal consistency was calculated with Cronbach's alpha coefficient, and a classical item analysis was carried out to obtain the correlations of the items with the corresponding factor and with the CSAS total score. Concurrent validity and test-retest reliability were calculated with the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient. Sensitivity and specificity were studied by means of a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and area under the curve (AUC). A 2×4 between-subjects analysis of variance was carried out for examining the differences by gender and age in separation anxiety. The analyses were carried out using the statistics packages SPSS version 20.0, AMOS version 20.0 and MedCalc version 12.5.

Gender and Age Differences

In the total sample we found a significant decrease in separation anxiety with age ( F 3, 6012 = 49.01, p <0.001). Mean score on the CSAS was 59.02 ( SD = 11.07) at age 8, 56.72 ( SD = 12.34) at age 9, 54.63 ( SD = 11.77) at age 10 and 49.84 ( SD = 11.73) at age 11. Magnitude of the differences was large between the children 8 aged and 11 ( d = 0.80), moderate between those aged 9 and 11 ( d = 0.57), and small in the remaining cases ( d <0.50).

Girls' mean score ( M = 56.08, SD = 12.35) was significantly higher than that of boys ( M = 53.49, SD = 11.98), though the difference was small ( F 1, 6014 = 12.37, p <0.001, d = 0.21). There was no interaction between the gender and age variables ( F 3, 6012 = 0.47, p = 0.71).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Four alternative models were assessed: 1) the null or independent model (M 0 ); 2) the one-factor model (M 1 ), in which the 20 scale items were forced to load in a general separation anxiety factor; 3) the uncorrelated four-factor model (M 4 ); and 4) the four correlated factors model (M 4* ).

To examine the adequacy of the assessed models we used six fit indexes: the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), the Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), the Normed Fit Index (NFI), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), as well as the chi-square statistic (χ 2 ). Browne and Cudeck [27] recommend a value of less than 0.05 for RMSEA. Hu and Bentler [28] suggest 0.95 for the NFI, CFI and TLI, as well as using a combination of fit indexes in order to reduce both type I and II errors. For GFI and AGFI, values above 0.90 are considered acceptable ( Table 4 ).

The chi-square statistic was significant, demonstrating a poor fit for all the models. However, these values must be considered with care, since the goodness of fit statistic χ 2 depends on the sample size. This statistic is very powerful with large samples, and can detect significant differences in spite of the fact that the models fit the data well; therefore, we took into account other fit indexes. The best fit of the models studied was shown by the four correlated factors model, which gave acceptable values for RMSEA GFI, AGFI, NFI, CFI and TLI. Table 5 shows the correlation coefficients among factors and with the total score of the CSAS.

Internal Consistency and Item Analysis

The internal consistency coefficients (Cronbach's alpha) were 0.82 for the CSAS, 0.83 for Factor 1, Worry about separation , 0.76 for Factor 2, Distress from separation , 0.72 for Factor 3, Opposition to separation , and 0.75 for Factor 4, Calm at separation . The item-subscale correlations were acceptable, with a range of 0.57 to 0.79. All the items obtained an item-test correlation higher than 0.30, indicating their adequate behavior. Table 6 shows the item-subscale correlation (IS-R), the corrected item-subscale correlation (IS-R c ), the item-test correlation (IT-R), the corrected item-test correlation (IT-R c ), the mean (M), and the standard deviation (SD) of the 20 CSAS items.

Test-retest Reliability

Test-retest reliability coefficients were r = 0.83 for CSAS, r = 0.69 for Worry about separation , r = 0.67 for Distress from separation, r = 0.70 for Opposition to separation , and r = 0.66 for Calm at separation .

Convergent and Discriminant Validity

Table 3 shows the correlation coefficients of the factors and the total CSAS score with other self-reports. Correlation of the CSAS total score with other measures of separation anxiety, specifically with the SAAS total score and with the score on the corresponding subscales of the SCARED and the SCAS were high, ranging between 0.61 and 0.72.

Analysis of the correlation coefficients of the CSAS and SAAS also reveals a close relationship between the similar factors of the two instruments, Worry about separation (CSAS) and Worry about calamitous events (SAAS) ( r = 0.58), Distress from separation (CSAS) and Somatic complaints/Fear of physical illness (SAAS) ( r = 0.46), and Opposition to separation (CSAS) and Safety Signals Index (SAAS) ( r = 0.51). Correlations of the Calm at separation (CSAS) factor, with no equivalent in the SAAS, were low with all the factors of the latter scale ( r <0.25).

Correlation of CSAS total score was good with anxiety sensitivity, higher with trait anxiety than with state anxiety, weak with school fears and depression, very low with trait anger, and non-existent with state anger.

Sensitivity and Specificity

Sensitivity was operationalized as the percentage of children with a SAD diagnosis according to the ADIS-IV-C who were correctly classified using the CSAS total score. Specificity was operationalized as the percentage of children that did not receive a SAD diagnosis in the interview and were correctly identified by the CSAS. The inverse relation between sensitivity and specificity requires equilibrium between the two for selecting the optimum cut-off point. For determining the positive predictive value (PPV) we calculated for each cut-off point the percentage of children with SAD who actually met the diagnostic criteria for this disorder. For determining the negative predictive value (NPV) we calculated for each cut-off point the percentage of children without SAD who actually did not meet the diagnostic criteria for this disorder. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and area under curve (AUC) were analyzed to establish the optimal cut-off score. The results showed that the AUC for ROC for the cut-off of 68 was 0.96 (95% CI, 0.93–0.98), and was significant versus chance or a random ROC line ( p <0.0001). This suggests that there is a 96% probability of a child with SAD scoring higher on the CSAS than children without SAD.

In order to assess the global diagnostic effectiveness we calculated the Youden Index [29] , which is the maximum vertical distance or the difference between the ROC curve and the diagonal or chance line. The results revealed that a score of 68 in the CSAS is the optimal cut-off, because it achieved the best balance, with good sensitivity (85%, 95% CI, 70–94) and specificity (95%, 95% CI, 92–97), a PPV of 76 and an NPV of 98. The Youden Index was 0.80 ( Fig. 1 ).