- Open access

- Published: 11 July 2018

How to engage stakeholders in research: design principles to support improvement

- Annette Boaz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0557-1294 1 ,

- Stephen Hanney 2 ,

- Robert Borst 3 ,

- Alison O’Shea 1 &

- Maarten Kok 4

Health Research Policy and Systems volume 16 , Article number: 60 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

107k Accesses

194 Citations

87 Altmetric

Metrics details

Closing the gap between research production and research use is a key challenge for the health research system. Stakeholder engagement is being increasingly promoted across the board by health research funding organisations, and indeed by many researchers themselves, as an important pathway to achieving impact. This opinion piece draws on a study of stakeholder engagement in research and a systematic literature search conducted as part of the study.

This paper provides a short conceptualisation of stakeholder engagement, followed by ‘design principles’ that we put forward based on a combination of existing literature and new empirical insights from our recently completed longitudinal study of stakeholder engagement. The design principles for stakeholder engagement are organised into three groups, namely organisational, values and practices. The organisational principles are to clarify the objectives of stakeholder engagement; embed stakeholder engagement in a framework or model of research use; identify the necessary resources for stakeholder engagement; put in place plans for organisational learning and rewarding of effective stakeholder engagement; and to recognise that some stakeholders have the potential to play a key role. The principles relating to values are to foster shared commitment to the values and objectives of stakeholder engagement in the project team; share understanding that stakeholder engagement is often about more than individuals; encourage individual stakeholders and their organisations to value engagement; recognise potential tension between productivity and inclusion; and to generate a shared commitment to sustained and continuous stakeholder engagement. Finally, in terms of practices, the principles suggest that it is important to plan stakeholder engagement activity as part of the research programme of work; build flexibility within the research process to accommodate engagement and the outcomes of engagement; consider how input from stakeholders can be gathered systematically to meet objectives; consider how input from stakeholders can be collated, analysed and used; and to recognise that identification and involvement of stakeholders is an iterative and ongoing process.

It is anticipated that the principles will be useful in planning stakeholder engagement activity within research programmes and in monitoring and evaluating stakeholder engagement. A next step will be to address the remaining gap in the stakeholder engagement literature concerned with how we assess the impact of stakeholder engagement on research use.

Peer Review reports

Closing the gap between research production and research use is a key challenge for the health research system. Stakeholder engagement is being increasingly promoted across the board by health research funding organisations, and indeed by many researchers themselves, as an important pathway to achieving impact [ 1 ]. The literature is diverse, with a rapidly expanding but still relatively small number of papers specifically referring to ‘stakeholder engagement’, and a larger number of publications discussing issues that at least partly overlap with stakeholder engagement. Several of the papers explicitly analysing stakeholder engagement come from the field of environmental research (e.g. Jolibert and Wesselink [ 2 ], Phillipson et al. [ 3 ]). However, stakeholder engagement is also gaining traction in the health field. A recent supplement in this journal consolidated learning relating to tools and approaches to stakeholder engagement within the United Kingdom Department for International Development’s Future Health Systems research consortium [ 4 ]. In particular, in health, there is an important stream of analysis from North America. A review for the United States Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality drew on papers from a range of fields [ 5 ].

This opinion piece provides a short conceptualisation of stakeholder engagement, followed by ‘design principles’ that we put forward based on a combination of existing literature and new empirical insights from our recently completed longitudinal study of stakeholder engagement in research. We have drawn on a systematic literature search conducted to inform the wider study and in particular to conceptualise stakeholder engagement (Additional file 1 ).

Literature review

Conceptualising stakeholder engagement: what does the literature say.

Stakeholders have been defined as “ individuals, organizations or communities that have a direct interest in the process and outcomes of a project, research or policy endeavor ” ([ 6 ], p. 5). In seeking to conceptualise stakeholders, Concannon et al. [ 7 ] developed the 7Ps Framework to identify stakeholders in Patient-Centered Outcomes Research and Comparative Effectiveness Research in the United States of America. The 7Ps are patients and the public, providers, purchasers, payers, public policy-makers and policy advocates working in the non-governmental sector, product makers, and principal investigators. The seven categories signal an overlap with the large literature on patient and public involvement (PPI) in research. However, our focus here is on multi-stakeholder engagement, where diverse groups of stakeholders take part in the research process. Deverka et al. [ 6 ] define engagement as “ an iterative process of actively soliciting the knowledge, experience, judgment and values of individuals selected to represent a broad range of direct interest in a particular issue, for the dual purposes of: creating a shared understanding; making relevant, transparent and effective decisions ” ([ 6 ], p. 5).

Roles, activities and phases of stakeholder engagement: What does the literature say?

There are additional issues about the definition of stakeholder engagement when the nature of the engagement activities is considered. For example, there are issues about how far co-creation/participatory action research approaches can be considered to be stakeholder engagement or something so far beyond the usual stakeholder engagement that they are really in a different category [ 8 ]. Similarly, there is a large and currently distinct literature on PPI in research [ 9 ], including the development of reporting guidelines such as GRIPP2 [ 10 ]. There are a number of parallels in the issues discussed in these literatures as well as some interesting differences (particularly in terms of power inequalities). However, herein, we conceptualise PPI as a subset of stakeholder engagement in-line with most of the literature, including Concannon et al. [ 7 ].

Most of the stakeholder engagement literature highlights the broad range of activities in which stakeholders can engage depending on their own skills and attributes and the capacity and wishes of the researchers conducting specific studies. At the broadest level of a research system, or research funding body, Lomas [ 11 ] claimed there were many activities in which stakeholders could be engaged in a ‘linkage and exchange’ approach for health services research. These were setting priorities, funding programmes, assessing applications, conducting research and communicating findings. The importance of engaging a wide range of stakeholders in priority-setting has often been emphasised. The pioneering study by Kogan and Henkel [ 12 ] analysed both the importance of engaging policy-makers in setting research agendas to meet their needs, and the obstacles to making the process work well. These obstacles included issues around how far the assessment of needs-based research should focus on the relevance and practical impact of the research as well as its scientific merit. Many of the more recent studies explicitly examining stakeholder engagement also set out a range of activities in which stakeholders may be involved. These are often related to phases of the research processes. Concannon et al. [ 7 ] provide a list of roles related to stages and used the identified roles in a subsequent review [ 13 ].

Knowledge translation (KT) is one of many terms used to describe efforts to ensure research evidence is used to inform decision-making [ 14 ]. Although the importance of engaging stakeholders in KT is recognised, it has been acknowledged that stakeholder engagement is often overlooked in favour of more conventional dissemination strategies [ 15 ]. Integrated KT has been developed as an approach to collaborative research in which researchers work with stakeholders who identify a problem and have the influence and sometimes authority to implement the knowledge generated through research [ 16 , 17 ]. Grimshaw et al. [ 14 ] argue that different groups of stakeholders are likely to be engaged depending on the type of research that is being translated.

Assessing the impact of stakeholder engagement: What does the literature say?

A final consideration about the nature of the body of literature specifically on stakeholder engagement is that not only is it still quite limited in total, but there are also notable areas where authors claim it is particularly sparse. In particular, Hinchcliff et al. [ 18 ] examined the literature on multi-stakeholder health services research collaborations in an attempt to address the question of whether it was worth investing in them. They identified very few studies (Harvey et al’s. [ 19 ] 2011 evaluation of a Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care being one exception) and concluded that their generalisability was questionable. They therefore suggested that “ The lack of reliable evidence compels implementers to rely largely on trial and error, risking variable success ” ([ 18 ], p. 124).

The nature of engagement activity is less contentious than the arguments about its potential impact. Research impacts on non-academic audiences are defined by the United Kingdom Higher Education Funding Council as: “ benefits to one or more areas of the economy, society, culture, public policy and services, health, production, environment, international development or quality of life, whether locally, regionally, nationally or internationally ” [ 20 ]. Various studies have attempted to assess a range of impacts of research (especially health research) and/or attempted to identify facilitators and barriers of research use in policy-making. There are also a growing number of reviews of such studies [ 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ]. While these are not explicitly studies of stakeholder engagement, many of them have identified some form of collaboration between researchers and users as one of the factors most likely to lead to the research making an impact. However, this wider range of literature does not go into detail in terms of analysing the nature of the processes of stakeholder engagement that leads to impact.

Studies specifically focusing on the impact of stakeholder engagement are less common, although it is a growing area of interest [ 28 , 29 ]. Jolibert and Wesselink [ 2 ] found a few examples of impact, but suggested ways to increase impact through what they describe as sustained interactions. Concannon et al. concluded that approximately 20% of their study participants “ reported that stakeholder engagement improved the relevance of research, increased stakeholder trust... enhanced mutual learning by stakeholders, and researchers about each other, or improved research adoption ” ([ 13 ], p. 1697), whereas 6% reported improved transparency and 9% increased understanding of research processes. Also, while Forsythe et al. referred to a lack of evidence about impact, they also observed that “ Commonly reported contributions included changes to project methods, outcomes or goals; improvement of measurement tools; and interpretation of qualitative data ” ([ 30 ], p. 13). In the United States, the Center for Medical Technology Policy website makes a strong statement about the impact of stakeholder engagement: “ Including the perspectives of all key stakeholders has powerful benefits, enhancing both the short- and long-term relevance of clinical research efforts ” [ 31 ].

Assessing the impact of stakeholder engagement: a new study

Given the diversity of stakeholder engagement and the thin evidence base for its impact, our study set out to identify a set of indicators that might be used to identify stakeholder engagement with potential for impact. We identified a study called the European study on Quantifying Utility of Investment in Protection from Tobacco (EQUIPT) and then conducted our own study, Stakeholder Engagement in EQUIPT (SEE-Impact) as a prospective study of stakeholder engagement running alongside. EQUIPT, a major European Commission (EC) – funded project, aimed to achieve impact through extensive stakeholder engagement. Both studies are briefly described in Box 1.

The results of the EQUIPT study have now been published [ 32 , 33 ] and a full account of the main methods from SEE-Impact have been submitted for publication. Papers on the full findings are being finalised. Herein, our aim is to address the statement in our original funding proposal in 2013 that it should be possible to identify aspects of the stakeholder engagement (and perhaps other features of the processes) that might be viewed as intermediate indicators of the eventual impact achieved.

Our analysis of the complex and nuanced process of stakeholder engagement has resulted not in a list of indicators, but in a set of design principles. We hope that these design principles will help to inform the future development of stakeholder engagement as a mechanism for promoting research impact. These principles, rooted in both the existing literature and in the findings from our prospective study of stakeholder engagement, are intended to inform the planning and delivery of stakeholder engagement activities. It is anticipated that they will also provide a structure for building a narrative account of stakeholder engagement as part of an evaluation of an individual project or programme. They might also provide a starting point for the development of future indicators.

Design principles for stakeholder engagement in research

The project team (comprising members of the SEE-Impact research team and collaborators from EQUIPT) met for a 2 day analysis workshop. One aim of the workshop was to begin to build a consensus among the team on what seemed to be the key design principles emerging from the SEE-Impact data and the on-going literature review. SEE-Impact data included observational data, interviews and document analysis. The research team continued to develop the principles through an ongoing period of deliberation, informed by the impact study and the literature. As part of this process, the principles were categorised into three groups, namely organisational, values and practices.

In this section, we first present empirical evidence from the SEE-Impact study that informed our development of the design principles. We then briefly summarise published evidence for each group of design principles in order to situate them in the wider literature.

Design principles and empirical evidence from the stakeholder engagement in EQUIPT for impact (SEE-impact) study

The stakeholder engagement study (SEE-Impact) and the project being studied (EQUIPT) are described in Box 1. In terms of the organisational level principles, the EQUIPT project objectives for stakeholder engagement were clear, as set out in the proposal, protocol and project documents [ 34 ]. The key aims of stakeholder engagement activity were to access the knowledge and skills (described in the protocol as co-creation innovation in the working space) and to increase influence and impact (described in the protocol as dissemination innovation in the transfer space through stakeholder engagement).

In terms of values, the commitment to stakeholder engagement was more clearly demonstrated by some of the EQUIPT project team members than others. For some team members, previous successful experience of an interactive form of working with stakeholders had built a commitment to this particular way of working. It also provided experience of practical elements of working with stakeholders, but perhaps most importantly lived experience of the practical benefits of engagement. For other members of the team, too, working with stakeholders fitted closely with their ethos and values. For example, the Hungarian team talked about their pragmatic approach to research and the need to conduct useful and usable research, with stakeholder engagement being a key component. However, a small group within the wider project team did not seem committed to ensuring stakeholder engagement remained a core element of the project. They favoured a particular, individualised approach to stakeholders and, over time, partially reshaped the stakeholder engagement activities to something more akin to research participation (that is, taking part in a research study as a means of generating specific data as determined by researchers, rather than as co-producers of research). Finally, not all stakeholders identified by the project team were interested in engaging with the project. In particular, the lack of policy priority given to smoking cessation (the focus of the return on investment (ROI) tool) made engagement of policy stakeholders in the Netherlands very difficult to achieve.

In terms of practices, while the EQUIPT project protocol did set out how the stakeholder engagement would operate [ 34 ], there was not as much flexibility as the investigators would have liked in terms of the project plan and this had an impact on the nature of the stakeholder engagement activities. In particular, time intensive methods of engagement originally proposed in the protocol (particularly the large number of face-to-face meetings) began to look unrealistic to members of the team. The lack of flexibility came in part from the funder. The EC told the project team at an early point that there was no scope for negotiation around the project end date. Thus, initial delays in the project put a strain on the project timetable and deliverables. Members of the team proposed a shift from face-to-face meetings with stakeholders to Skype meetings in an effort to ‘catch up’. The technical team producing the new version of the ROI tool for roll out in Europe added to a sense of urgency in ‘speeding up’ the stakeholder engagement work with their need for data to feed into their work. Nevertheless, despite the practical difficulties, in EQUIPT, a significant amount of consideration had been given to stakeholder engagement, including planning how the input provided by stakeholders might be gathered, collated, analysed and used. Vokó et al. highlight that it is important to “ fully analyse several aspects of stakeholder engagement in research ” ([ 32 ], p. 15) and note that there is a tendency to ignore the value of early stakeholder engagement when it comes to development and transferability in the work of economic evaluation. EQUIPT’s careful consideration and the methods adopted facilitated a much more rigorous approach to stakeholder engagement than is often experienced.

Design principles and supporting literature

The design principles for stakeholder engagement are organised into three groups, namely organisational, values and practices, albeit with some inevitable overlaps. We look at each category in turn, alongside a consideration of some of the relevant literature.

Organisational

Clarify the objectives of stakeholder engagement

Embed stakeholder engagement in a framework or model of research use

Identify the necessary resources for stakeholder engagement

Put in place plans for organisational learning and rewarding of effective stakeholder engagement

Recognise that some stakeholders have the potential to play a key role

Some examples from the literature

It is desirable to have a conceptual framework that situates stakeholder engagement as part of a plan for promoting research use in practice. Deverka et al. [ 6 ] proposed an ‘analytic-deliberative’ conceptual model for stakeholder engagement which “ illustrates the inputs, methods and outputs relevant to CER [comparative effectiveness research]. The model differentiates methods at each stage of the project; depicts the relationship between components; and identifies outcome measures for evaluation of the process ” ([ 6 ], p. 1). Furthermore, having a clear evaluation plan is considered critical. Concannon et al. recommended conducting “ evaluative research on the impact of stakeholder engagement on the relevance, transparency and adoption of research ” ([ 13 ], p. 1698). Esmail et al. argue that evaluations of stakeholder engagement should be “ designed a priori as an embedded component of the research process ” ([ 35 ], p. 142). They suggest that, where possible, evaluations should use predefined, validated tools. Jolibert and Wesselink [ 2 ] point out that linking stakeholders’ contributions with specific research objectives is important in order to establish when and how to engage and with whom. They argue that, at the recruitment stage, stakeholders should be made aware of, for example, their role/s, what they could contribute, costs in terms of time and effort, and benefits. Concannon et al. also conclude that funding is needed “ to account for the costs of implementing meaningful engagement activities ” ([ 7 ], p. 989).

In a Canadian study looking at stakeholder involvement in KT as a means of leading to more evidence-informed healthcare, Holmes et al. [ 36 ] identify a range of complexities which, they argue, need to be taken into account by funding schemes in order to meet funders’ and stakeholders’ expected ROI. Stakeholder involvement in research and implementing its findings is complex and time consuming, and the authors recommend an advocacy role where funders support a range of activities to address barriers to effective KT. These include carrying out an assessment of stakeholders’ KT needs “ to identify gaps and opportunities and avoid duplication of efforts ” ([ 36 ], p. 6). Kramer et al. [ 37 ] looked at the involvement of intermediary organisations as research partners on three interventions across four sectors, namely manufacturing, transportation, service and electrical utilities sectors. The authors describe the difficulties, benefits and challenges from the perspectives of both researchers and research partners and stress the importance of allowing the design of the protocol to be collaborative and flexible. Researchers need to honour, trust and respect their partners’ knowledge and expertise, and take into account their needs and priorities. Failure to meet these criteria will significantly dampen stakeholders’ enthusiasm. They also point out the importance of having a model of collaborative research with clear guidelines of how to conduct partnership research projects in order to further facilitate the use of research by practitioners. There would be an invested interest in “ the research question, design and findings, and this would prove to be very valuable as a knowledge transfer strategy ” ([ 37 ], p. 330).

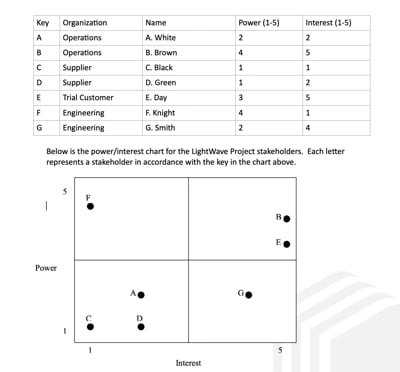

The main literature on stakeholder analysis of policy-making is also useful for highlighting that some stakeholders have more potential to play a key role in the policy deliberations than others. For example, as part of their review of stakeholder analysis of health policy-making, Brugha and Varvasovszky [ 38 ] described an example in which the Hungarian Ministries of Finance and Industry were non-mobilised, high-influence, low-interest stakeholders in debates about public health interventions, but might, in some circumstances, become mobilised high-interest actors.

Foster shared commitment to the values and objectives of stakeholder engagement in the project team

Share understanding that stakeholder engagement is often about more than individuals

Encourage individual stakeholders and their organisations to value engagement

Recognise potential tension between productivity and inclusion

Generate a shared commitment to sustained and continuous stakeholder engagement

Concannon et al. [ 7 ] stress that researchers and stakeholders should be committed to the processes from the outset. Hinchcliff et al. [ 18 ] argue that it is important to define expectations and roles and provide time. Hering et al.’s [ 39 ] global study of water science and technology used stakeholder involvement in the objectives and approaches of the research for the co-production of knowledge as part of transdisciplinary research. Key aspects of particular value to the research included early identification and involvement of stakeholders, continuous engagement with stakeholders, and availability to stakeholders of supporting materials and in multiple languages. Mallery et al. recommend continuing to build trust with stakeholders “ throughout the engagement process ” ([ 5 ], p. 27).

Plan stakeholder engagement activity as part of the research programme of work

Build flexibility within the research process to accommodate engagement and the outcomes of engagement

Consider how input from stakeholders can be gathered systematically to meet objectives

Consider how input from stakeholders can be collated, analysed and used

Recognise identification and involvement of stakeholders is an iterative and ongoing process

Forsythe et al. [ 30 ] highlight the importance of careful and strategic selection of stakeholders. As part of evidence and experience-based guidance to researchers and practice personnel about forming and carrying out effective research partnerships, Ovretveit et al. [ 40 ] developed a guide to categorise and describe types of partnerships or approaches to collaborative working. The guide sets out a framework for the roles and tasks, and the allocation of responsibilities for each partner involved. Roles and tasks are assigned to three main categories, namely questions, design and data, reporting and dissemination, and implementation and integration into organisation or policy. Concannon et al. [ 13 ] suggest the need to develop (and validate) stakeholder engagement tools to support engagement work. Forsythe et al. also stress the importance of “ establishing ‘parameters and expectations for roles’, giving stakeholders guidance, and allowing time for stakeholders to ‘get comfortable with their roles’ as important tasks ” ([ 30 ], p. 19).

The review of methods of stakeholder engagement conducted by Mallery et al. [ 5 ] identified a range of innovative methods and stressed the potential for engaging stakeholders at different points in the research process. The five methods highlighted for consideration were online collaborative forums, product development challenge contests, online communities, grassroots community organising and collaborative research. Jolibert and Wesselink [ 2 ] explored levels and types of stakeholder engagement in 38 EC-funded biodiversity research projects and the impacts of collaborative research on policy, society and science. They looked at how and when stakeholders were involved and the roles played, and argue that greater engagement throughout the whole of the research process, rather than, for example, at the dissemination stage, tends to lead to improved assessment of environmental change and effective policy proposals. Jolibert and Wesselink suggest, following Huberman’s [ 41 ] work in education, that it is desirable to have ‘sustained interactivity’ between researchers and users. Concannon et al. suggest that “ General principles can be drawn from community-based participatory research, which underscores that engagement is a relationship-building process ” ([ 7 ], p. 988). They found that, if bi-directional relationships are sustained over time, stakeholders can serve as ambassadors for high-integrity evidence even where the findings are contrary to generally accepted beliefs. Hinchcliff et al. point to the importance of “ building respect and trust through ongoing interaction ” ([ 18 ], p. 125). Forsythe et al. flag up the importance of continuous involvement and using in-person contact to build relationships [ 30 ]. They also stress the value in having a flexible approach that can adapt to the practical needs of stakeholders. A recent supplement of this journal edited by Paina et al. [ 4 ] also highlighted the importance of flexibility in making space for stakeholder engagement in research processes.

Based on the literature and the application of initial principles to our study, we have developed the elaborated design principles presented in Box 2.

Conclusions

There is a growing interest in stakeholder engagement as a potentially promising approach to promoting research impact. There is also a developing literature mapping out who potential stakeholders might be (the ‘who’), considering approaches to stakeholder engagement (the ‘how’) and identifying rationales for stakeholder engagement (the ‘why’). In this paper, evidence from the literature around these dimensions has been combined with the findings from our study of stakeholder engagement in an EC-funded project to develop a set of design principles to inform future stakeholder engagement in research. The design principles encompass organisational factors, values and practices. We hope that the principles will be useful in planning stakeholder engagement activity within research programmes and in monitoring and evaluating stakeholder engagement. Active engagement of stakeholders may well shift our understanding of what research use looks like [ 39 ]. A next step will be to address the remaining gap in the stakeholder engagement literature concerned with how we assess the impact of stakeholder engagement on research use.

Box 1: Studying stakeholder engagement in tobacco control policy

EQUIPT: the European-study on Quantifying Utility of Investment in Protection from Tobacco

The EQUIPT study set out to work with stakeholders to develop a tool to help government officials, policy-makers and healthcare providers across Europe examine the cost effectiveness and impact of anti-smoking initiatives. The tool was developed as part of a €2 million European Commission grant. An earlier version had already been piloted with local authorities around the United Kingdom, with users able to draw on specific circumstances, statistics and data to predict the impact of tobacco control in their particular regions. The successful stakeholder engagement in the United Kingdom work encouraged the research team to fully integrate stakeholder engagement into the European study. In this study, the following stakeholders were identified: National and European stakeholders consisting of policy-makers, academics, health authorities, insurance companies, advocacy groups, ministries of finance, national committees, clinicians and health technology assessment (HTA) professionals, and experts on smoking cessation and HTA. Ninety three stakeholders took part. They were engaged in a variety of ways, including through one-to-one interviews, Skype meetings and events. Much of the engagement activity focused on the development of the return of investment tool for application in different countries.

SEE-Impact: Stakeholder Engagement in EQUIPT for Impact

SEE-IMPACT was a 3-year prospective study awarded £157,000 from the United Kingdom’s Medical Research Council funding as part of their joint Methodology Programme with the National Institute for Health Research, earmarked to boost understanding of the impact of health-related studies on society and the economy. The study compared and contrasted the way the EQUIPT decision support tool was taken up in a further four European countries – Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands and Spain. The SEE-Impact study focused in particular on the ways in which stakeholders were engaged throughout the EQUIPT study. The study used a range of methods including interviews, surveys, observations and reviews of documents to develop a detailed understanding of how stakeholder engagement might work as a mechanism for promoting impact. An initial literature review on stakeholder engagement was used to distil a set of propositions for testing. Further details about the project can be found on the website of the MRC (now under United Kingdom Research and Innovation).

Box 2 Design principles for stakeholder engagement

1) Clarify the objectives of stakeholder engagement

The objectives might be one or more of accessing knowledge and skills; supporting interpretation of the results and drafting recommendations; supporting future influence and impact on policy and practice; increasing recruitment/enabling research; supporting transferability. The objectives need to be shared then among all parties.

2) Embed stakeholder engagement in a framework or model of research use

There are a number of models and frameworks designed to show how stakeholders might be engaged in a way that helps increase the chances of research being used in policy and practice, for example, the linkage and exchange model [ 9 ]

3) Identify the necessary resources for stakeholder engagement

Resources to consider are budget, time, skills and competences to manage engagement

4) Put in place plans for organisational learning and rewarding of effective stakeholder engagement, for example, through appropriate evaluation of stakeholder engagement

5) Recognise that some stakeholders have the potential to play a key role

Identify those stakeholders who are particularly interested in being engaged and those who are likely to be influential. Depending on the objective of stakeholder engagement, they may provide the most useful input, and are most likely to play a key role in using the results; their engagement should be especially encouraged

6) Foster shared commitment to the values and objectives of stakeholder engagement in the project team

Ideally, make sure the commitment is there from the outset [ 6 ]

7) Share understanding that stakeholder engagement is often about more than individuals

Consideration needs to be given to stakeholders’ roles where they act as representatives – their power and influence within organisations and networks they represent and how these change over time

8) Encourage individual stakeholders and their organisations to value engagement

Support and build capacity for stakeholders and their organisations to engage

9) Recognise potential tension between productivity and inclusion

Engagement may lead to greater relevance and impact, but may have implications for productivity in meeting project objectives (for example, in a timely fashion). Engaging stakeholders, taking into account their needs and inputs and adjusting elements of the research project based on their feedback takes time and can slow down the research process

10) Generate a shared commitment to sustained and continuous stakeholder engagement

Project teams and stakeholders see the value of links between research producers and research users to build ongoing collaborations in order to meet the objectives

11) Plan stakeholder engagement activity as part of the research programme of work

This should be built into the project protocol or plan (see Pokhrel et al. [ 34 ])

12) Build flexibility within the research process to accommodate engagement and the outcomes of engagement

It will also be important to build in mechanisms to allow researchers to have the independence to articulate what is out of scope

13) Consider how input from stakeholders can be gathered systematically to meet objectives

The importance of some face-to-face contact and interactions should be considered

14) Consider how input from stakeholders can be collated, analysed and used

This important aspect of stakeholder engagement needs to be considered earlier than often happens

15) Recognising identification and involvement of stakeholders is an iterative and ongoing process

Ongoing interaction will be fostered by taking the time and creating the structures to build trustful relationships ([ 6 , 12 ])

Abbreviations

European Commission

European-study on Quantifying Utility of Investment in Protection from Tobacco

Knowledge translation

Patient and public involvement

Return on investment

Stakeholder Engagement in EQUIPT for Impact

Kok M, Gyapong J, Wolffers I, Ofori-Adjei D, Ruitenberg J. Which health research gets used and why? An empirical analysis of 30 cases. Health Res Policy Syst. 2016;14:36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-016-0107-2 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Jolibert C, Wesselink A. Research impacts and impact on research in biodiversity conservation: The influence of stakeholder engagement. Environ Sci Policy. 2012;20:100–11.

Article Google Scholar

Phillipson J, Lowe P, Proctor A, Ruto E. Stakeholder engagement and knowledge exchange in environmental research. J Environ Manag. 2012;95:56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.10.005 .

Paina L, Ekirapa-Kiracho E, Ghaffar A, Bennett S. Engaging stakeholders in implementation research: tools, approaches, and lessons learned from application. Health Res Policy Syst. 2017;15(Suppl 2):104.

Google Scholar

Mallery C, Ganachari D, Fernandez J, Smeeding L, Robinson S, Moon M, Lavallee D, Siegel J. Innovative Methods in Stakeholder Engagement: An Environmental Scan. Prepared by the American Institutes for Research under contract No. HHSA 290 2010 0005 C. AHRQ Publication NO. 12-EHC097-EF. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012.

Deverka PA, Lavallee DC, Desai PJ, Esmail LC, Ramsey SD, Veenstra DL, et al. Stakeholder participation in comparative effectiveness research: defining a framework for effective engagement. J Comp Eff Res. 2012;1(2):181–94.

Concannon TW, Meissner P, Grunbaum JA, McElwee N, Guise JM, Santa J, Conway PH, Daudelin D, Morrato EH, Leslie LK. A new taxonomy for stakeholder engagement in patient centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:985–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2037-1 .

Greenhalgh T, Jackson C, Shaw S, Janaiman T. Achieving research impact through cocreation in community-based health services: literature review and case study. Milbank Q. 2016;94(2):392–429.

Boaz A, McKevitt C, Biri D. Rethinking the relationship between science and society: has there been a shift in attitudes to patient and public involvement and public engagement in science in the United Kingdom? Health Expect. 2016;19(3):592–601. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12295 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, Seers K, Mockford C, Goodlad S, et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. BMJ. 2017;358:j3453.

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Lomas J. Using ‘linkage and exchange’ to move research into policy at a Canadian foundation. Health Aff. 2000;19(3):236–40. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.19.3.236 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kogan M, Henkel M. Government and Research: The Rothschild Experiment in a Government Department. London: Heinemann Educational Books; 1983. (2nd edition. Dortrecht: Springer; 2006).

Concannon TW, Fuster M, Saunders T, Patel K, Wong JB, Leslie LK, Lau J. A systematic review of stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness and patient-centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:1692–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2878-x .

Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7:50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-50 .

Bowen S, Graham ID. Integrated knowledge translation. In: Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham ID, editors. Knowledge Translation in Health Care: Moving from Evidence to Practice. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118413555.ch02 .

Chapter Google Scholar

McCutcheon C, Graham ID, Kothari A. Defining integrated knowledge translation and moving forward: a response to recent commentaries. Int J Health Policy Manage. 2017;6(5):299–300.

Gagliardi AR, Berta W, Kothari A, Boyko J, Urquhart R. Integrated knowledge translation (IKT) in health care: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2016;11:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0399-1 .

Hinchcliff R, Greenfield D, Braithwaite J. Is it worth engaging in multi-stakeholder health services research collaborations? Reflections on key benefits, challenges and enabling mechanisms. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26:124–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzu009 .

Harvey G, Fitzgerald L, Fielden S, McBride A, Waterman H, Bamford D, Kislov R, Boaden R. The NIHR collaboration for leadership in applied health research and care (CLAHRC) for greater Manchester: combining empirical, theoretical and experiential evidence to design and evaluate a large-scale implementation strategy. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):96. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-96.

Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE). 2014 REF: Assessment Framework and Guidance on Submissions. Panel A Criteria. London: HEFCE; 2012.

Innvær S, Vist G, Trommald M, Oxman A. Health policy-makers’ perceptions of their use of evidence: a systematic review. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002;7:239–44. https://doi.org/10.1258/135581902320432778 .

Hanney SR, Gonzalez-Block MA, Buxton MJ, Kogan M. The utilisation of health research in policy-making: concepts, examples and methods of assessment. Health Res Policy Syst. 2003;1:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-1-2 .

Lavis J, Davies H, Oxman A, Denis JL, Golden-Biddle K, Ferlie E. Towards systematic reviews that inform health care management and policymaking. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10 Suppl 1:35–48. https://doi.org/10.1258/1355819054308549 .

Boaz A, Fitzpatrick S, Shaw B. Assessing the impact of research on policy: a literature review. Sci Public Policy. 2009;36:255–70. https://doi.org/10.3152/030234209X436545 .

Banzi R, Moja L, Pistotti V, Facchini A, Liberati A. Conceptual frameworks and empirical approaches used to assess the impact of health research: an overview of reviews. Health Res Policy Syst. 2011;9:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-9-26 .

Oliver K, Innvar S, Lorenc T, Woodman J, Thomas J. A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-2 .

Hanney S, Greenhalgh T, Blatch-Jones A, Glover M, Raftery J. The impact on healthcare, policy and practice from 36 multi-project research programmes: findings from two reviews. Health Res Policy Syst. 2017;15:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-017-0191-y .

Nyström ME, Karltun J, Keller C, Andersson Gäre B. Collaborative and partnership research for improvement of health and social services: researcher’s experiences from 20 projects. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-018-0322-0.

Pollock A, Campbell P, Struthers C, Synnot A, Nunn J, Hill S, Goodare H, Watts C, Morley R. Stakeholder involvement in systematic reviews: a protocol for a systematic review of methods, outcomes and effects. Res Involv Engage. 2017;3:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-017-0060-4 .

Forsythe LP, Ellis LE, Edmundson L, Sabharwal R, Rein A, Konopka K, Frank L. Patient and stakeholder engagement in the PCORI pilot projects: description and lessons learned. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:13–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3450-z .

Center for Medical Technology Policy. Stakeholder Engagement. http://www.cmtpnet.org/our-work/stakeholder-engagement/ . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

Vokó Z, Cheung KL, Józwiak-Hagymásy J, Wolfenstetter S, Jones T, Muñoz C, Evers S, Hiligsmann M, de Vries H, Pokhrel S. On behalf of the EQUIPT study. Similarities and differences between stakeholders’ opinions on using health technology assessment (HTA) information across five European countries: results from the EQUIPT survey group. Health Res Policy Syst. 2016;14:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-016-0110-7.

Evers SMAA, Hiligsmann M, Vokó Z, Pokhrel S, Jones T, et al. Understanding the stakeholders’ intention to use economic decision-support tools: a cross-sectional study with the tobacco return on investment tool. Health Policy. 2016;120(1):46–54.

Pokhrel S, Evers S, Leidl R, Trapero-Bertran M, Kalo Z, De Vries H, et al. EQUIPT: protocol of a comparative effectiveness research study evaluating cross-context transferability of economic evidence on tobacco control. BMJ Open. 2014;4(11) https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-%20006945 .

Esmail L, Moore E, Rein A. Evaluating patient and stakeholder engagement in research: moving from theory to practice. J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4(2):133–45. https://doi.org/10.2217/cer.14.79 .

Holmes B, Scarrow G, Schellenberger M. Translating evidence into practice: the role of health researcher funders. Implement Sci. 2012;7:39.

Kramer D, Wells R, Bigelow P, Carlan N, Cole D, Hepburn CG. Dancing the two-step: collaborating with intermediary organizations as research partners to help implement workplace health and safety interventions. Work. 2010;36(3):321–32. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2010-1033 .

Brugha R, Varvasovszky Z. Stakeholder analysis: a review. Health Policy Plan. 2000;15:239–46.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Hering J, Hoffmann S, Meierhofer R, Schmid M, Peter A. Assessing the societal benefits of applied research and expert Consulting in Water Science and Technology. Gaia. 2012;21(2):95–101. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.21.2.6 .

Ovretveit J, Hempel S, Magnabosco JL, Mittman BS, Rubenstein LV, Ganz DA. Guidance for research-practice partnerships (R-PPs) and collaborative research. J Health Organ Manage. 2014;28(1):115–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHOM-08-2013-0164 .

Huberman M. Research utilization: the state of the art. Knowl Policy. 1994;7(4):13–33.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of the EQUIPT team, in particular, the Principal Investigator Subhash Pokhrel.

The SEE-Impact study (Stakeholder Engagement in EQUIPT for Impact), received funding from the United Kingdom Medical Research Council to explore the engagement of stakeholders in the EQUIPT project.

The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Health, Social Care and Education, a partnership between Kingston University and St George’s, University of London, London, United Kingdom

Annette Boaz & Alison O’Shea

Health Economics Research Group, Brunel University London, Uxbridge, United Kingdom

Stephen Hanney

Erasmus School of Health Policy & Management, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

Robert Borst

VU University Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Maarten Kok

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AB and SH conceived of the study. All authors contributed to the design, data collection and analysis. An initial draft of the paper was produced by AB, with all authors contributing significantly to its development and revision. The final version has been approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Annette Boaz .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical approval for the study entitled ‘Stakeholder Engagement in EQUIPT for Impact (SEE-IMPACT)’ was gained from the Research Ethics Committee, the Faculty of Health, Social Care and Education, St George’s University of London and Kingston University, on 18th March 2014.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:.

SEE-Impact study literature search. (DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Boaz, A., Hanney, S., Borst, R. et al. How to engage stakeholders in research: design principles to support improvement. Health Res Policy Sys 16 , 60 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-018-0337-6

Download citation

Received : 28 February 2018

Accepted : 06 June 2018

Published : 11 July 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-018-0337-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Stakeholder Engagement

- Build Flexibility

- Value Engagement

- Health Systems Research

- Shared Commitment

Health Research Policy and Systems

ISSN: 1478-4505

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

To read this content please select one of the options below:

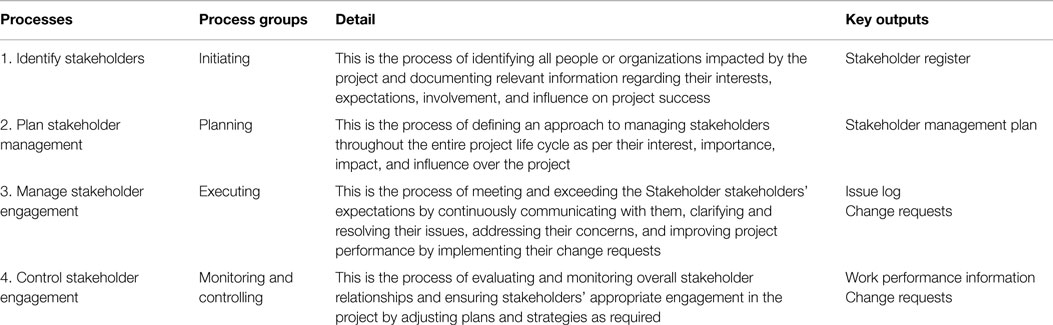

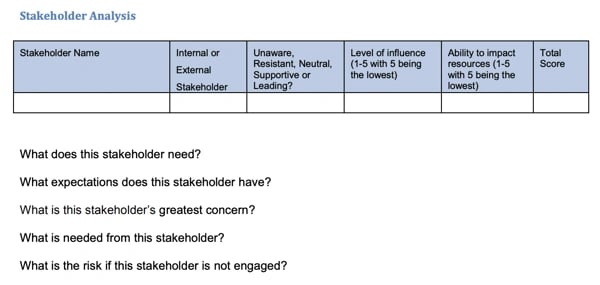

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, stakeholder management: a systematic literature review.

Corporate Governance

ISSN : 1472-0701

Article publication date: 20 September 2018

Issue publication date: 4 February 2019

The stakeholder theory is a prominent management approach that has primarily been adopted in the past few years. Despite the increase in the theory’s use, a limited number of studies have discussed ways to develop, execute and measure the results of using this strategic approach with stakeholders. This study aims to address this gap in the literature by conducting a systematic review of the stakeholder management process.

Design/methodology/approach

Five databases were selected to search articles published from 1985 to 2015. The keywords used were stakeholder management, stakeholder relationship and stakeholder engagement. Starting from 2,457 articles identified using a keyword search, 33 key journal articles were systematically reviewed using both bibliometric and qualitative methods for analysis.

The results highlight that stakeholder management is increasingly embedded in corporate activities, and that the coming of the internet, social networking and Big Data have put more pressure on companies to develop new tools and techniques to manage stakeholders online. In conclusion, synthesizing the findings and developed framework allows the understanding of different streams of research and identifies future steps for research.

Originality/value

While literature reviews are a widespread practice in business studies, only a few more recent reviews use the systematic review methodology that aggregates knowledge using clearly defined processes and criteria. This is the first review on stakeholder management in which the structure is existing knowledge on strategy development, execution and the measurement of performance.

- Stakeholder management

- Systematic review

- Stakeholder engagement

- Stakeholder relationship

Pedrini, M. and Ferri, L.M. (2019), "Stakeholder management: a systematic literature review", Corporate Governance , Vol. 19 No. 1, pp. 44-59. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-08-2017-0172

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2018, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Loading metrics

Open Access

Ten simple rules on how to develop a stakeholder engagement plan

Contributed equally to this work with: Susanne Hollmann, Babette Regierer, Jaele Bechis

* E-mail: [email protected] (SH); [email protected] (BR)

Affiliations SB Science Management UG (haftungsbeschränkt), Berlin, Germany, University of Potsdam, Faculty of Science, Potsdam, Germany

Affiliations University of Potsdam, Faculty of Science, Potsdam, Germany, Leibniz Institute of Vegetable and Ornamental Crops (IGZ) e.V., Großbeeren, Germany

Affiliation Université de Lorraine, Université de Strasbourg, CNRS, BETA, Nancy, France

¶ ‡ LT and DD’E also contributed equally to this work.

Affiliation Rete Europea dell’Innovazione—REDINN, Pomezia, Italy

Affiliation Institute for Biomedical Technologies, National Research Council, Bari, Italy

- Susanne Hollmann,

- Babette Regierer,

- Jaele Bechis,

- Lesley Tobin,

- Domenica D’Elia

Published: October 13, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1010520

- Reader Comments

To make research responsible and research outcomes meaningful, it is necessary to communicate our research and to involve as many relevant stakeholders as possible, especially in application-oriented—including information and communications technology (ICT)—research. Nowadays, stakeholder engagement is of fundamental importance to project success and achieving the expected impact and is often mandatory in a third-party funding context. Ultimately, research and development can only be successful if people react positively to the results and benefits generated by a project. For the wider acceptance of research outcomes, it is therefore essential that the public is made aware of and has an opportunity to discuss the results of research undertaken through two-way communication (interpersonal communication) with researchers. Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI), an approach that anticipates and assesses potential implications and societal expectations regarding research and innovation, aims to foster inclusive and sustainable research and innovation. Research and innovation processes need to become more responsive and adaptive to these grand challenges. This implies, among other things, the introduction of broader foresight and impact assessments for new technologies beyond their anticipated market benefits and risks. Therefore, this article provides a structured workflow that explains “ how to develop a stakeholder engagement plan ” step by step.

Citation: Hollmann S, Regierer B, Bechis J, Tobin L, D’Elia D (2022) Ten simple rules on how to develop a stakeholder engagement plan. PLoS Comput Biol 18(10): e1010520. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1010520

Copyright: © 2022 Hollmann et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: This publication is based on outputs of the COST Action CHARME supported by COST - European Cooperation in Science and Technology ( https://www.cost.eu ) funding agreement CA15110, results of the project OXIPRO funded by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme ( https://ec.europa.eu ) under Grant Agreement No. 101000607 and SB Science Management UG ( www.sb-sciencemanagement.com ). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Scientific knowledge is one of the pillars of the modern economy [ 1 ]. As underlined by the European Commission (EC) [ 2 ], science strongly contributes to innovation creation and valorisation [ 3 ]. Innovation, as the dissemination, reuse, and valorisation of knowledge, plays a major role in employment and economic growth. While the time lag between research and its financial economic exploitation may be long and characterised by high uncertainty, “the economic impact of science is indisputable” [ 4 ].

For these reasons, funding bodies playing a major role in research funding, such as the EC, have always been interested in the optimal spending on scientific research [ 5 ] and continue to orient policies for making research outcomes more meaningful, and research more responsible. This applies to basic scientific research as well as to applied science. Citing Needham, Freeman says that “There is really only science with long term promise of application and science with short term promise of application” [ 6 ].

Meaningful and responsible research requires the alignment of public-funded research with societal values and needs to influence the project’s trajectory and increase the societal impact. Research and technological advances only make sense if they are useful, usable, and embraced by consumers. This requires the public to be made aware of new scientific developments and to have the opportunity to communicate and interact with researchers. Therefore, early engagement with stakeholders is of paramount importance [ 7 – 9 ].

Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) emphasises the importance of two-way communication between researchers and stakeholders. It is a “transparent, interactive process by which societal actors and innovators become mutually responsive to each other with a view on the (ethical) acceptability, sustainability and societal desirability of the innovation process and its marketable products” [ 7 ]. “RRI should be understood as a strategy of stakeholders to become mutually responsive to each other and anticipate research and innovation outcomes underpinning the ‘grand challenges’ of our time for which they share responsibility” [ 10 ] and as such lead to desirable societal benefits [ 11 , 12 ].

In this context, engagement with multiple stakeholders ( Fig 1 ) is of utmost importance in modern research for catalysing scientific knowledge use [ 13 , 14 ] especially through information and communications technology (ICT).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Definition of a stakeholder [ 6 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1010520.g001

In addition, allowing stakeholders to interact with the project in its initial stage can result in tailored products, services and solutions [ 15 , 16 ]. This engagement allows the researchers to adjust project strategies from the beginning, avoiding futile, money-wasting, and time-consuming activities. Therefore, since 2014, the EC has called for engagement with stakeholders as a prerequisite to receiving funding.

To discuss the research results, two-way communication requires engaging stakeholders, which may not be an easy task. The added value, however, is that it allows both the communicator and the recipient to freely express their views, ideas, and feelings. This mutual exchange of information creates a democratic environment in the setting that is beneficial for both parties. For the project team, it is an opportunity to receive relatable feedback and, if needed, to react accordingly. For stakeholders, it represents a way to participate in the whole research project and, in this way, guide the research towards its specific objectives and real needs.

Due to the heterogeneity of stakeholders, the implementation of different approaches is necessary to reach every single actor and ensure appropriate coordination.

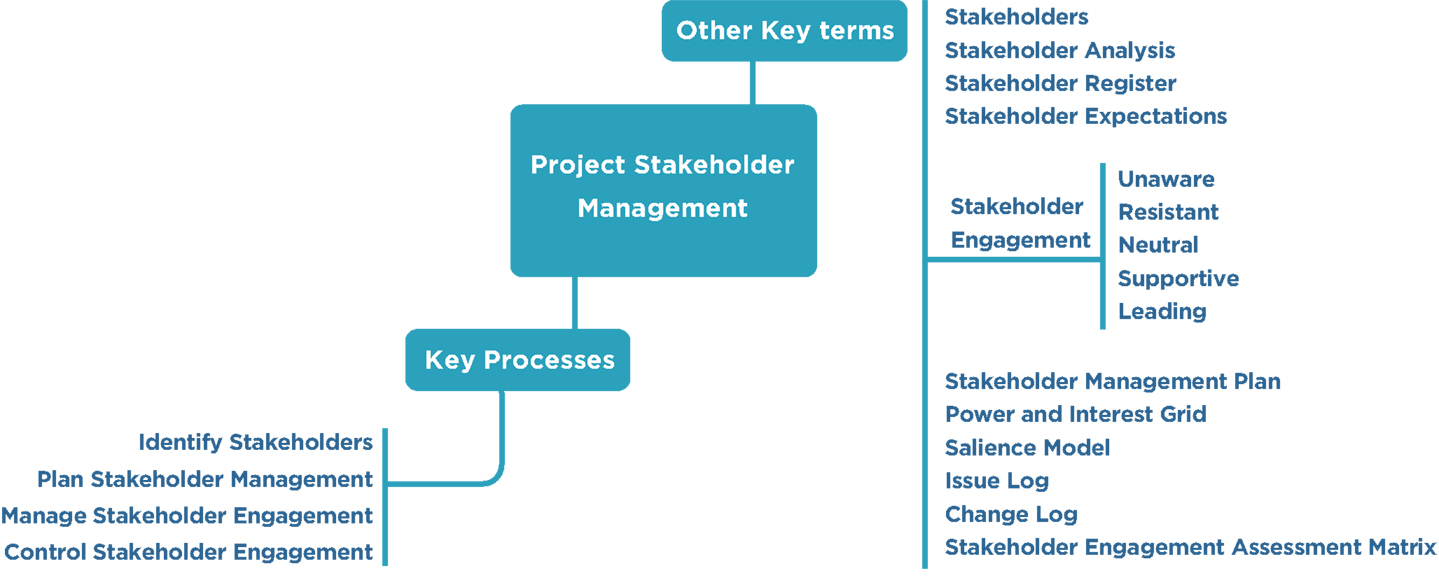

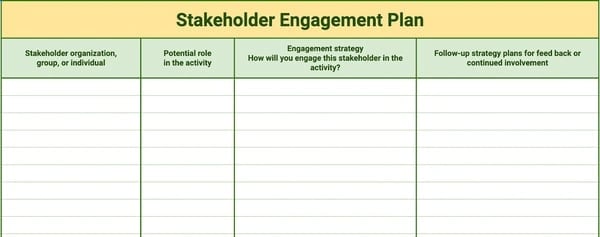

With this paper, we provide “10 simple rules on how to develop a stakeholder engagement plan” that help identify and manage stakeholder engagement and, fundamentally, adopt an RRI approach. It is important to note here that the stakeholder engagement plan is not a static document and should be revised and reviewed in tandem with the project implementation.

Rule 1: Identify and formulate the challenges of the project

Before identifying the stakeholders, a careful analysis of the internal and external opportunities and threats or risks to the project should be carried out. This analysis of the project framework conditions is necessary to achieve its expected outcomes and impact and to understand which stakeholder groups should be involved for the success of the project. In doing so, 2 main tools can help to analyse both internal and external challenges to be overcome in order to reach the desired outcomes. The Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT) Analysis tool [ 17 ] is designed for the identification of both internal and external factors that may influence project outcomes and impact. In particular, the tool focuses on strengths and weaknesses that characterise the project’s success and on opportunities and threats that emanate from the external environment. Because of the complexity of the external environment, the analysis needs to be further developed using the Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental, and Legal (PESTEL) [ 17 ] framework. This second tool focuses on the external elements, namely political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal factors that may influence the desired outcomes. The identification of these key external factors is crucial because they might have a relevant influence on your research, while you have only little or no means to control these. With a careful analysis of these factors, it is possible to take action to avoid potential pitfalls and, on the other hand, exploit new opportunities.

By conducting the analysis, elements are identified that provide a clearer view of such factors and conditions that may affect the project outcomes. Knowing them helps to identify and select the conditions that need to be met in order to achieve your objectives, including the stakeholders to be involved.

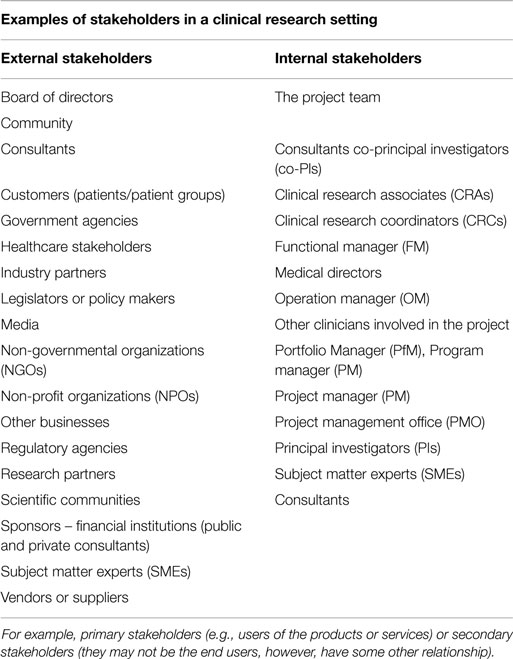

Rule 2: Identify stakeholders

Once the SWOT and PESTEL analysis results are specified, it is easier to identify actors, i.e., mapping stakeholders, that are likely to be impacted by project outcomes. In this second step, it is necessary to select the actors that need to be involved in facing the defined challenges. To avoid investing time and efforts in a nontargeted (or unfavourable) strategy, it is crucial to ensure that relevant stakeholders are already engaged from the beginning of the research activities.

It is advisable to commence with the specification of the stakeholder reference groups (the stakeholder areas). Stakeholder areas describe the fields that stakeholders represent, i.e., Research, Industry, Policy, and Society. We further divided these stakeholders’ areas into 3 more specific levels: macro-, meso-, and microlevel. The authors of this paper define these levels as follows: macrolevel means all individuals directly affiliated or working in a branch of a stakeholder area such as, e.g., the pharmaceutical industry without any further specification or discrimination. They can be technicians, project managers, engineers, or persons from the management area. Although they belong to the same area, they will not have the same background, needs, interests, or influence on the project. Mesolevel refers to groups representing specific sectors of the macrolevel: one sector covers, for example, all technicians and manufacturing people, the developers, the managers, etc., representing another sector. The microlevel is represented by the single individuals from the above mesolevel.

Keeping in mind the immediate needs of the project, the next stage entails scheming out potential stakeholder needs and the expected impact on the project outcomes as a result of their involvement (feedback).

This analysis enables the evaluation and comparison of the different effects of specific stakeholders on the project as well as how the project can meet diverse stakeholder needs or expectations. The data should be structured in a table designed to record 3 types of key data for each stakeholder; for example, stakeholder needs, project needs, and expected impact.

Rule 3: Implement a roadmap to ensure conformity with data privacy policy

Intellectual property (IP) concerns and data disclosure are examples of issues to be addressed when interacting with actors involved in the project in different ways. While IP refers to the outgoing data management, data disclosure concerns incoming data. Confidentiality of project data is a typical example of data that may raise IP concerns when they are to be shared with stakeholders. In contrast, the management of data generated by stakeholders clearly represents a data disclosure issue.

Therefore, an essential element here is the implementation of specific measures, ensuring conformity with the existing regulations at both national, supranational, and international levels. An example is the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [ 18 ], applicable to all entities collecting data related to persons in the European Union. GDPR is developed around 4 main axes: lawful basis and transparency, data security, accountability and governance, and privacy rights. For example, the data minimisation principle, included in the data security section, states that “You should collect and process only as much data as necessary for the purposes specified.” Because interaction measures differ between stakeholder groups, the information provided to or needed from each stakeholder group might be different. It may be that, for example, information about the age and ethnicity of stakeholders is important for one group but might not be essential for another. Therefore, in order to comply with the data minimisation principle, it is vital to form a clear idea about the specific data emanating from each stakeholder group that is required for the project.

Following the identification of all the IP and data management aspects to be addressed, the next step is to define a robust strategy for complying with the legal framework, e.g., data transfer agreements, consent agreements, etc. As a legal matter and one of the pillars of RRI, from this point, a Data Protection Officer, or the Technology Transfer Office, who also manage ethical issues, must be involved in this process.

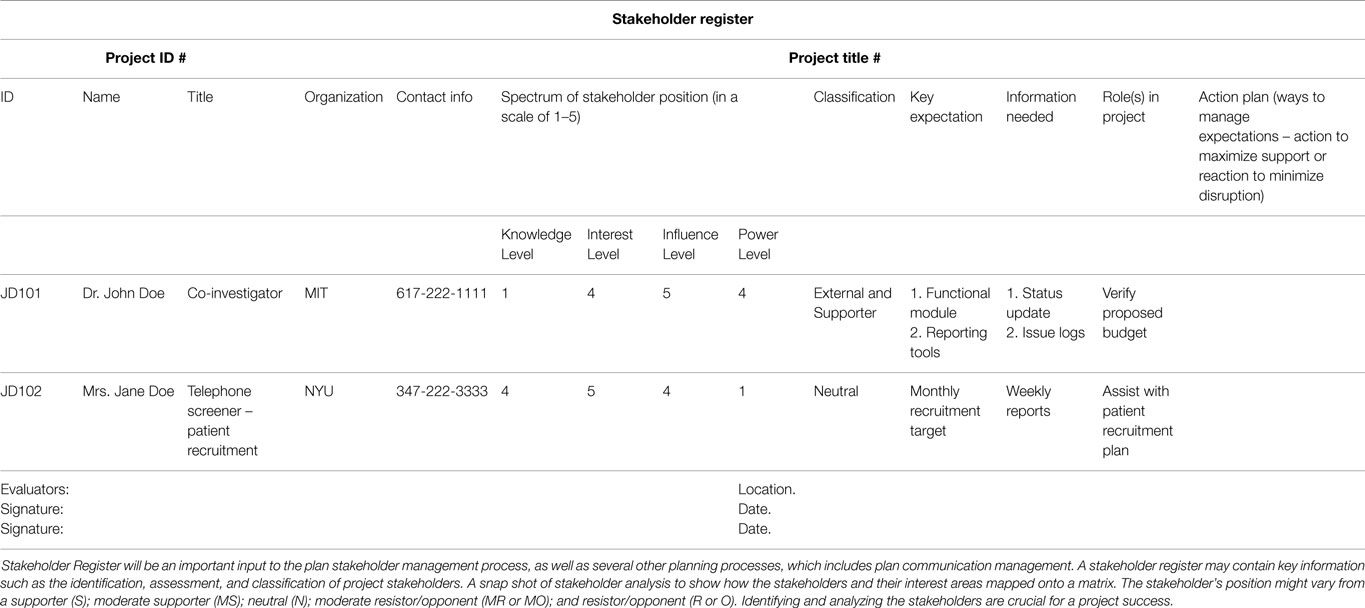

Rule 4: Collect stakeholder data (stakeholder register)

All stakeholder information should be collected in a stakeholder register ( Table 1 ). The personal information entered in the Register forms the basis for the stakeholder mapping, whereby all individuals are assigned to a specific area and level. It is important to note that some individuals can belong to different stakeholder groups.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1010520.t001

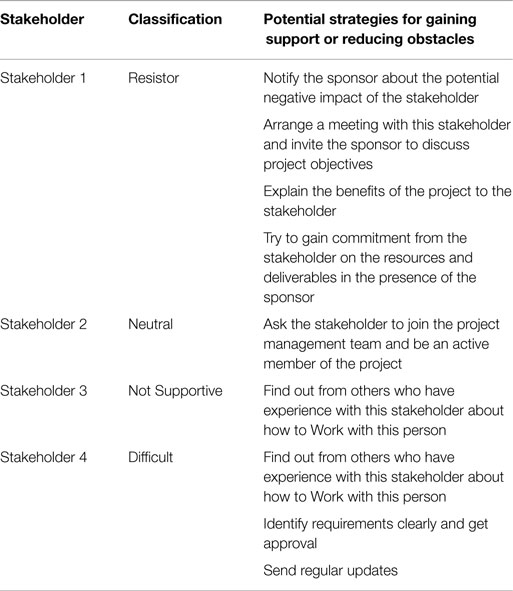

Rule 5: Categorise stakeholders into priority groups

Once the stakeholder register is compiled, stakeholders can be categorised into different priority groups.

Stakeholder classification is necessary for managing their engagement. Stakeholder engagement is a time-consuming activity, and stakeholders differ in terms of the role and the influence they may have on the project’s success. For example, high-priority group members can support or hinder the project, while low-priority groups have a marginal impact on the project outcomes. Therefore, it is essential to prioritise some groups over others.

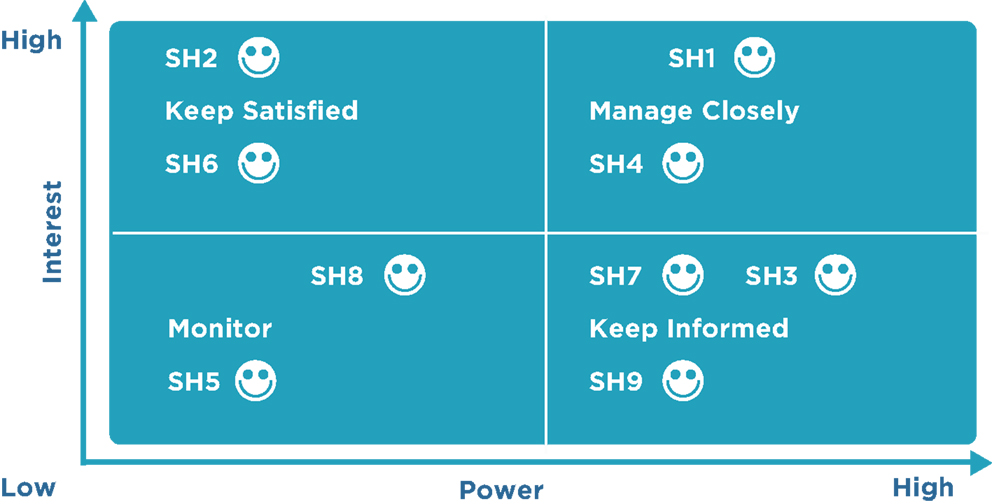

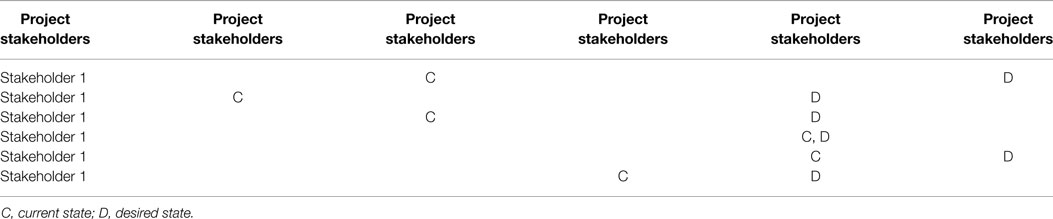

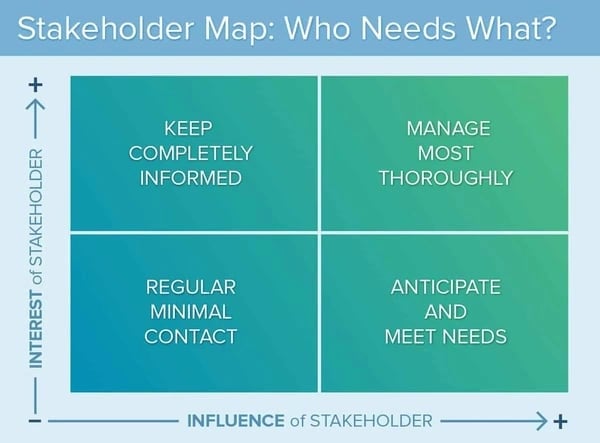

An effective tool for prioritising stakeholder groups is Mendelow’s matrix [ 19 ]. This system analyses stakeholders according to 2 main characteristics: their interest in the project and their influence on the project outcomes. As a result, 4 different priority groups will emerge: (1) Key stakeholder; (2) Influencer; (3) Interested stakeholder; and (4) Passive stakeholder. The key stakeholders are individuals with high interest and high influence. Influencers are those who have low interest but high influence. The 2 remaining groups are the interested (high interest/low influence) and passive stakeholders (low interest/low influence). Results of stakeholder categorisation are provided in Table 2 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1010520.t002

Once the stakeholders have been categorised into priority groups, the matrix enables the definition of the purpose and the degree of the interaction with each stakeholder group. Special attention must be paid to those individuals who belong to the first 2 groups.

When the purpose is clarified for each stakeholder, stakeholder engagement efforts and activities can be oriented, as shown in Table 3 , where the categorisation output is reported in the first column while the engagement efforts and activities are displayed in the third column.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1010520.t003

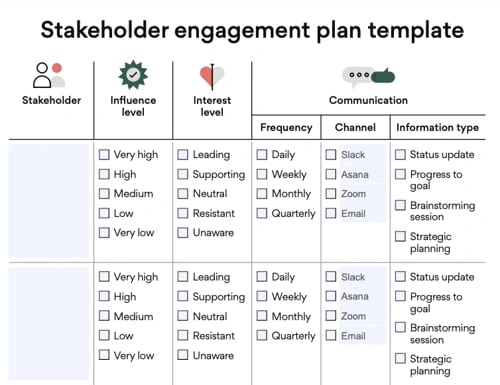

Rule 6: Devise a stakeholder engagement plan

After creating the stakeholder register, followed by the mapping and prioritisation of the stakeholder groups, the next stage is to devise your stakeholder engagement plan. This plan is designed as a strategic document and timeline that will facilitate the management of stakeholder engagement throughout the lifespan of the project.

As a strategic document, the plan outlines all the specific activities addressed to each stakeholder group that fit the purposes identified in Rule 5. Because the nature of stakeholder involvement is not the same for each priority group, different strategies and media tools must be adopted to reach and engage them. For example, for key stakeholders, solely issuing and targeting them with newsletters will be insufficient and other strategies should be added and implemented to keep them on track, such as round tables and workshops. Conversely, for passive stakeholders, social networks and newsletters are adequate. The greater the stakeholder’s interest and power, the greater the communication flow should be.

Identifying the instruments to be used for implementing the stakeholder engagement plan or strategy is a key point concerning the methodology to be developed. To this end, it is worthwhile listing all the possible dissemination tools considered most suitable for the project’s communication strategy, and then deciding which group(s) can be effectively reached with each tool. Moreover, communication should be two-way; therefore, stakeholders must also be able to communicate with the project representatives and members.

Once the communication strategy has been finalised, it is time to focus on planning activities. Given the different activities necessary for engaging stakeholders, this plan should also be designed along a timeline. Scheduling activities on a timeline will facilitate their timely implementation and allow for appropriate priority to be given to each stakeholder group to be contacted and engaged, in line with the project schedule and deliverable deadlines.

All the activities necessary for implementing the stakeholder engagement plan require time and human as well as other resources. Knowing how much time is required to complete a task or a series of tasks (e.g., preparing a survey or organising a meeting) is pivotal for the plan to be successful. Therefore, in compiling and fixing the schedule of planned activities, the human resources that must be dedicated and the time necessary for each activity should be carefully calibrated. For example, preparing a round table or a workshop requires far more time, resources, and effort than preparing a survey or creating a brochure. For the organisation of a meeting, there are several key considerations to be made. These include topic selection (depending on the high-priority group interests), identification and invitation of keynote speakers, preparation of publicity material (e.g., brochure or flyer), dissemination of the event on selected channels (newspapers, social media, etc.), selection of the event venue, hosting, and facilitation, and in some cases the organisation of social events that are fundamental to prompt interpersonal relationships and stimulate people to work together towards common objectives. Such activities require planning months in advance, with each planning stage executed on time. Finally, since stakeholders are often not members of the project, they may need to be motivated to foster active participation in the organised activities. They may not always be available to participate throughout the planned schedule. Moreover, stakeholders also have individual preferences; for example, some prefer meetings while others like to engage in a one-on-one conversation or through written media; also, security or IP issues might play a role when choosing the optimal interaction tool. Thus, the engagement plan should be adaptable and flexible with built-in alternative strategies if stakeholders prove to be unresponsive.

Rule 7: Identify, select, and test tools for the implementation of Rule 6 and its GDPR conformity

Once the communication strategy has been defined and the most suitable tools to be used identified, it is time to work on the content and format of the chosen communication media. This will require identifying the communication tool that best fits the project’s needs and is the most appealing to the target stakeholder group. During this phase, it is important to define the approach for communication, the content, and the tool(s) to be used. For example, choices may include face-to-face or online meetings, newsletters, surveys, structured interviews, and social network campaigns. Of these choices, structured interviews can prove beneficial in that the questions are planned and created in advance. Accordingly, all candidates are asked the same questions in the same order, making it easier to compare and evaluate their responses objectively and fairly, rendering such structured interviews more legally defensible.

Once the communication media have been compiled, it is worth conducting a meaning and error check for clarity and correctness. A review by peers and colleagues may improve the comprehensibility and accuracy of the media, its formulation, design, and hence the overall efficacy of the communication strategy.

The final step involves testing the GDPR conformity of the communication media, referring to the strategy defined when following Rule 3. The collected interview data and the tools and software utilised for managing the communication activity should be examined for compliance with GDPR guidelines.

Rule 8: Make contact—Engage stakeholders

At this point, the engagement plan can be rolled out to initiate the two-way communication with the stakeholder groups, and this communication should be followed through. For example, when an email is sent to a stakeholder, it is important to pursue this line of contact and ascertain whether a connection has indeed been established, i.e., whether the targeted stakeholder responded positively to the email, subscribed to the project newsletter, or, conversely, if they unsubscribed from your mailing list. Different factors may affect the success of the engagement: For example, unresponsiveness may be an indication that the group has been wrongly prioritised or the person to engage with has been misidentified, or an inadequate media channel has been selected and utilised. Ultimately, it may be that the email sent has landed in their junk folder or was filtered by a spamming programme or firewall. Should these issues arise, it may be necessary to revisit the previous rules ( Fig 2 ) and make the necessary adjustments until a satisfactory result is achieved. The number of responses or newsletter subscriptions will be strong indicators as to whether a trusting relationship has been built with the stakeholders.

If the stakeholder engagement is not successful, it may be necessary to revisit previous rules and, especially, to check contacts, replace unresponsive stakeholders, and change the content and/or the communication flow. The scheme demonstrates the workflow for revision.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1010520.g002

Note that it is not yet a central task to include all external stakeholders in the communication flow at the beginning of a project. However, the extensive exploitation of social networks is central to the initiation of the communication process. One starting point is to create posts on media channels where specific interest groups or communities can be targeted, for example, scientific networking tools such as ResearchGate, or professional networking platforms such as LinkedIn. Posting project-related videos on YouTube can also increase visibility, particularly if the video is well designed and the content is developed by experts in the field. In this type of promotion for the project, the appeal of the communication can be enhanced with the use of nonspecialist language and visually attractive material.

Rule 9: Evaluate stakeholder feedback

Considering stakeholder responses is not a passive task, but an assessment activity. Stakeholder feedback should be discussed with partners and, if appropriate, with other stakeholders before it is incorporated into the project strategy leading, e.g., to changes in the project plan. The purpose of stakeholder involvement is to make the research successful and responsible and to balance the needs and requirements of the project with those of the stakeholders.