Mental Health and Substance Use Co-Occurrence Among Indigenous Peoples: a Scoping Review

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 28 July 2023

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Breanne Hobden ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8489-6152 1 , 2 ,

- Megan Freund 1 , 2 ,

- Jennifer Rumbel 3 , 4 ,

- Todd Heard 1 , 4 , 5 ,

- Robert Davis 1 , 2 ,

- Jia Ying Ooi 1 , 2 ,

- Jamie Newman 6 ,

- Bronwyn Rose 7 ,

- Rob Sanson-Fisher 1 , 2 &

- Jamie Bryant 1 , 2

1643 Accesses

Explore all metrics

This scoping review examined the literature on co-occurring mental health conditions and substance use among Indigenous peoples globally across (i) time, (ii) types of conditions examined, (iii) countries, (iv) research designs, and (v) participants and settings. Medline, Embase, PsycInfo, and Web of Science were searched across all years up until October 2022 for relevant studies. Ninety-four studies were included, with publications demonstrating a slight and gradual increase over time. Depressive disorder and alcohol were the most examined co-occurring conditions. Most studies included Indigenous people from the United States (71%). Ninety-seven percent of the studies used quantitative descriptive designs, and most studies were conducted in Indigenous communities/reservations (35%). This review provides the first comprehensive exploration of research on co-occurring mental health and substance use conditions among Indigenous peoples. The information should be used to guide the development of strategies to improve treatment and prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Substance use disorders in Saudi Arabia: a scoping review

Substance Use Disorders Among Forcibly Displaced People: a Narrative Review

Community-based psychosocial substance use disorder interventions in low-and-middle-income countries: a narrative literature review

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Both between and within countries, Indigenous’ Peoples represent diverse groups with unique perspectives on health and wellbeing. Broadly, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia view health with the perspective that a holistic and whole-of-life approach is needed to achieve positive health and wellbeing outcomes (Australian Government, 2017 ). This sentiment is echoed by Indigenous groups in the United States (US), Canada, and Aotearoa (New Zealand), where physical health is linked with mental, social, and spiritual wellbeing (Gall et al., 2021 ; Hodge et al., 2009 ; Mark & Lyons, 2010 ). Colonisation continues to impact the health of Indigenous people through ongoing intergenerational trauma and discriminatory systemic policies (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, 2022 ; O’Neill et al., 2018 ; Te Kōmihana Whai Hua O Aotearoa (New Zealand Productivity Commission), 2022). This impact is apparent through the disproportionate prevalence of mental health (MH) conditions and severity of substance use among Indigenous people. In Australia in 2011, MH conditions and substance use disorders contributed to 23% of the total burden of disease for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, the largest burden out of any disease group (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, 2016 ). Similar overrepresentation of MH conditions and substance use has been reported for Maori people in Aotearoa (Ministry of Health New Zealand, 2018 ). Reducing the impact and severity of MH conditions and substance use is important for improving the health and wellbeing of Indigenous people.

While previous research has examined the published literature examining MH conditions or substance use among Indigenous peoples (Kisely et al., 2017 ; Nelson & Wilson, 2017 ), the scope of research examining the co-occurrence of these conditions is less clear. Co-occurring conditions often have an exacerbating and debilitating impact on the health of affected individuals (Leung et al., 2016 ). Co-occurrence is associated with greater severity of MH symptoms, higher quantity of substance use, increased disability or impairment, poorer social functioning, and increased risk of suicide (Burns & Teesson, 2002 ; Leung et al., 2016 ; Quello et al., 2005 ). Co-occurring conditions have also been reported to significantly impact family and carers (Biegel et al., 2007 ; September & Beytell, 2019 ). Considering co-occurring conditions, as opposed to individual conditions, provides a more person-focussed and integrated approach to wellbeing (Mercer et al., 2016 ). Integrated treatment of co-occurring conditions has also demonstrated improved treatment outcomes (Leung et al., 2016 ). Despite this, most research and treatment provision continues to adopt an approach where researchers and clinicians focus on singular conditions (McCartney, 2016 ; Teesson et al., 2014 ).

To the authors’ knowledge, no previous review has systematically examined the literature for co-occurring MH conditions and substance use among Indigenous’ people, nationally or internationally. Scoping reviews allow exploration of the volume and coverage of particular topics to identify gaps, concepts, and key characteristics, as well as informing the feasibility of more detailed systematic reviews (Munn et al., 2018 ). The number of research outputs in an area of research can be considered a proxy for resource and investment in a particular field (Ebadi & Schiffauerova, 2016 ), allowing funding bodies to identify areas where research activity is lacking. Furthermore, examining the scope of the literature, such as location, design, setting, and focus, will allow the identification of research gaps to inform future research and policy directions regarding co-occurring MH conditions and substance use among Indigenous peoples (Munn et al., 2018 ).

To systematically review studies examining co-occurring MH conditions and substance use among Indigenous peoples globally to determine the scope of publications in terms of (i) volume over time, (ii) MH conditions and substance conditions examined, (iii) countries where the research was undertaken, (iv) research designs implemented, and (v) included Indigenous groups and settings.

Methodology is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) scoping review guidelines (Page et al., 2021 ; Tricco et al., 2018 ).

Indigenous Leadership for This Review

This review concept arose through collaboration between Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers and those working in the health field on an Australian Rotary Health Fellowship to understand the co-occurrence of MH conditions and substance use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Co-authors JR, TH, RD, JN, and BR are Aboriginal members of the team and formed the Aboriginal Advisory Group for this project. In addition to lived experiences, the Aboriginal Advisory Group has expertise in mental health, substance use, and health services. The remaining authors are non-Indigenous. The aims of the review were discussed and revised through ongoing collaborative discussion with the whole research team. Study methodology and interpretation of results were discussed and reviewed by Indigenous and non-Indigenous team members throughout the project.

Search Strategy

A medical librarian was consulted to develop and implement the search strategy. Medline, Embase, PsycInfo, and Web of Science were searched across all years up until 11th October 2022. Key terms included “mental disorders”, “substance related disorders”, “comorbidity” and “Indigenous peoples”. A full list of the search terms used can be found in Appendix 1 . A manual review of the reference lists of included papers was performed to identify any additional articles not identified through the search strategy.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included in the review if they:

Focussed on Indigenous peoples. Studies were identified through the use of terms such as “Indigenous”, “First Nations”, “Aboriginal” or referring to the name of a specific Indigenous peoples (e.g. Maori). If the research included both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, comorbidity data needed to be presented separately for the Indigenous cohort or more than 50% of the sample needed to be Indigenous to be included. This criterion was intended to reduce the number of studies that incidentally included Indigenous peoples but did not specifically explore comorbidity among these groups.

Reported on comorbidity across at least one MH condition and one type of substance use. The type of comorbidity examined, and the determination of comorbidities was deliberately broad to enable a more inclusive scoping approach (see Box 1).

Described data-based research, including experimental, quantitative, and qualitative studies.

Box 1 Categorisation of conditions.

Studies were excluded if they:

Exclusively reported on suicide, suicide ideation, suicide attempts, and learning disorders as these are not considered MH conditions.

Exclusively focussed on gambling or gaming addictions as these are not substance-based. Studies which included gambling or gaming addiction and substance addiction were included, but only substance data were extracted.

Focussed on basic sciences (e.g. genetic studies).

Were commentaries, case studies, conference abstracts, theses, or reviews.

Were published in a language other than English.

Article Screening

Paper titles and abstracts were reviewed against the inclusion criteria by three authors (BH, JR, and JYO) and a research assistant. The first 108 papers were independently coded by two researchers (BH and JR or the research assistant) and checked for agreement. There was an 88% agreement rate between coders after initial coding. Discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached. Following this, JR and the research assistant screened the remaining studies. All excluded studies were cross-checked by JYO at a later date. BH and JYO reviewed the full texts for final inclusion.

Data Extraction

A data extraction template was created using REDCap electronic data capture tools (Harris et al., 2019 ). This was piloted by JB, MF, and JYO with BH making amendments before commencing full data extraction. The following data were extracted from the included studies: author, year, conditions examined and how conditions were assessed (e.g. diagnostic interview), country, Indigenous population group, research design, sample size, and setting. Studies were categorised into experimental, qualitative, or quantitative descriptive research designs. Experimental studies were then coded as randomised-controlled trials, non-randomised controlled trials, interrupted time series, or controlled before and after studies (Cochrane Effective Practice & Organisation of Care, 2017 ). Study setting was categorised based on anticipated settings for MH conditions and substance use research (e.g. general community, Indigenous communities, MH or substance use services, hospitals), with author derived coding for additional settings (e.g. legal settings, such as detention centres). Where multiple papers were derived from one study, data were extracted for each individual paper due to the different combinations of comorbidities examined across papers resulting from large datasets.

Data Analysis

Frequencies and proportions were used to synthesise the extracted data. A linear regression was performed to examine changes in the volume of publications over time, with a p -value of < 0.05 used to indicate significance.

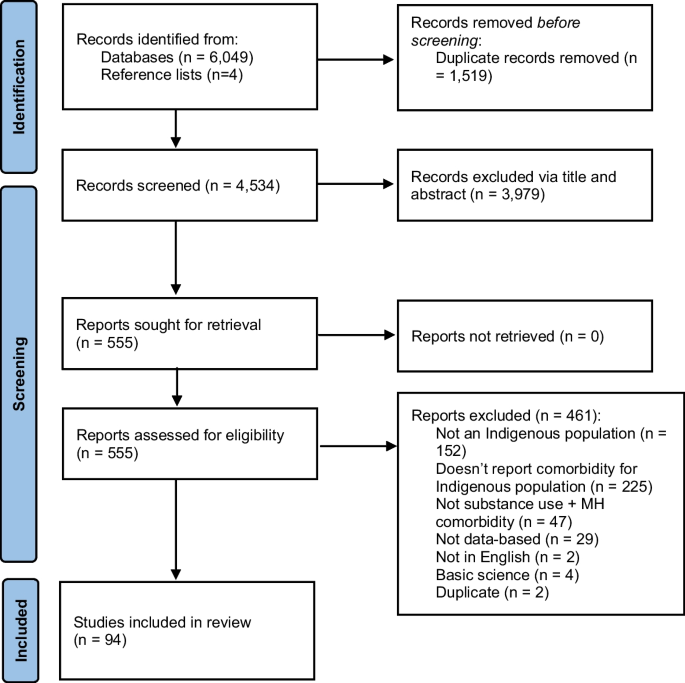

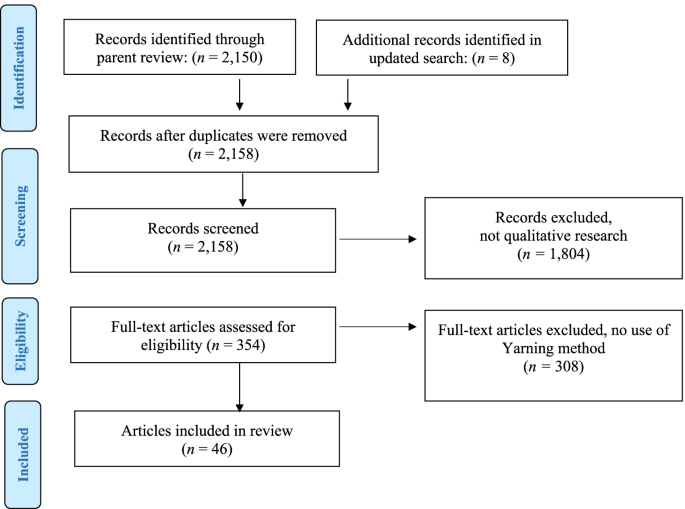

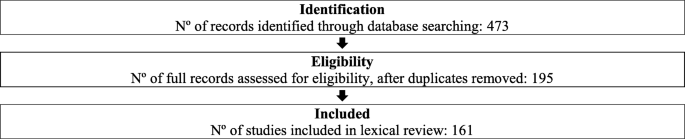

Figure 1 presents the results of the literature search using the PRISMA flow chart. A total of 6049 citations were identified through the search strategy and 4 through searching reference lists, with 4534 articles retained following the removal of duplicates. A total of 3979 articles were excluded at the title and abstract screening stage, and 555 underwent full text review. Ninety-four articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. For brevity, the frequencies of studies are presented in-text without specific references. The Supplementary file ( S1 ), however, provides the detailed data extraction for each included paper.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow chart

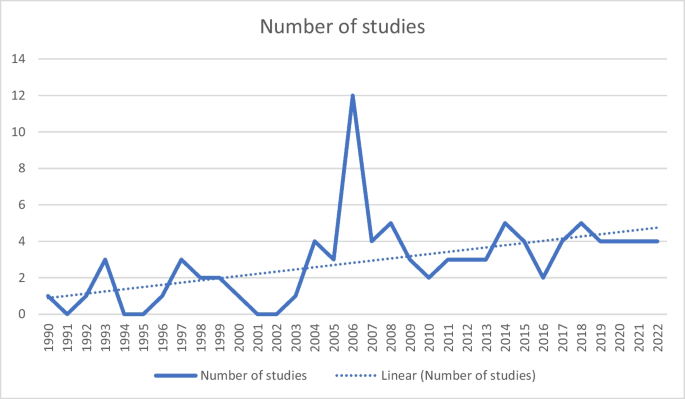

Volume of Publications Over Time

While publications demonstrated a statistically significant increase over time from 1990 to 2022 ( R 2 = 0.26, p -value = 0.003), the volume of publications was low across most years. An average of 2.8 papers were published per year since 1990. From 1990 to 2000, there were an average of 1.3 publications per year ( n = 14 total), which increased from 2001 to 2011 and 2012 to 2022, with an average of 3.4 ( n = 37 total) and 3.8 ( n = 42 total) per year, respectively (see Fig. 2 ).

The number of studies examining comorbid mental health conditions with alcohol and other drug use by year

Co-Occurring Conditions Examined

Studies included an average of 2.4 MH condition groupings, and 44 papers examined three or more MH condition groupings. Among these, depressive disorders ( n = 64, 68% of studies) and anxiety disorders ( n = 49, 52%) were the most commonly examined, and eating disorders were the least frequently examined ( n = 6, 6%). MH conditions were primarily measured using diagnostic interviews ( n = 55, 59%), of which 2 studies used validated screening measures in addition to diagnostic interviews. Of the remaining studies, 20 (23%) used validated screening measures, 5 (5%) used non-validated screening measures, and 11 (12%) used medical records. One (1%) study did not report how MH conditions were measured.

For substance use, studies included an average of 1.9 substances, and 25 papers examined three or more substances. Alcohol was the most frequently examined substance ( n = 58, 62% of studies), followed by general substance use or grouping of multiple substances ( n = 45, 48%). Sedatives ( n = 3, 3%), hallucinogens ( n = 3, 3%), and inhalants ( n = 2, 2%) were the least frequently examined substances. Substances were primarily measured using diagnostic interviews ( n = 44, 47%), of which one also used non-validated screening measures. Of the remaining studies, 20 (22%) used standardised screening measures, 13 (14%) used non-validated screening measures, one (1%) study used both validated and non-validated screening measures, 11 (12%) used medical records, and two (2%) used help-seeking to indicate substance use. Three studies did not report how MH conditions were measured.

There were a broad range of co-occurring conditions examined (see Table 1 ). It was also common for papers to group MH or substance use conditions or to consider these in general terms (e.g. reporting on “substance dependence” or “MH conditions”). Alcohol and depression were the most frequently examined co-occurring conditions ( n = 17).

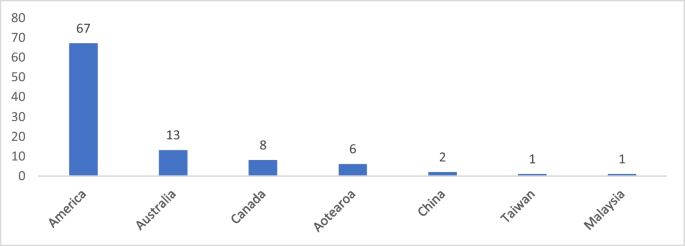

Countries Where the Research Was Undertaken

Most studies were conducted with Indigenous peoples from the US ( n = 67, 71%). Of these, 46 included Native American Indian Peoples, two studies included Indigenous peoples from Alaska, and 12 included both Native American Indian and Alaskan participants. Four studies included Indigenous peoples from the US and Canada, and three studies specifically included Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander Peoples. One study included Native American Indian, Alaskan, and Hawaiian people. Fewer studies were conducted in Australia with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people ( n = 13, 14%); Canada among Indigenous Metis and Inuit people ( n = 8, 9%); and Aotearoa of which five included Māori people and one included Pacific Islander people ( n = 6, 6%). While the Pacific Islander groups (i.e. Samoan, Tongan, Cook Islanders) in the latter study are not Indigenous to Aotearoa, they are Indigenous to the Pacific Islands, and therefore, this study was retained. Two studies included Han Chinese people, one study included Malayo-Polynesian Aboriginal people from Taiwan, and one study included Malay people from Malaysia (see Fig. 3 ).

The number of studies examining comorbid mental health and alcohol or other drug use by country. Note: Four studies included Indigenous people from the United States and Canada and have been counted for both countries

Research Designs Implemented

Almost all publications used quantitative descriptive designs ( n = 91, 97%). One study used a mixed method design, including a qualitative phase followed by a randomised controlled trial. One study used a randomised controlled trial design, and one study used a qualitative design. Among the descriptive studies, 79 (87%) used a cross-sectional design, nine (10%) used a longitudinal design, and two (2%) used a cross-sequential design.

Indigenous Sample and Settings

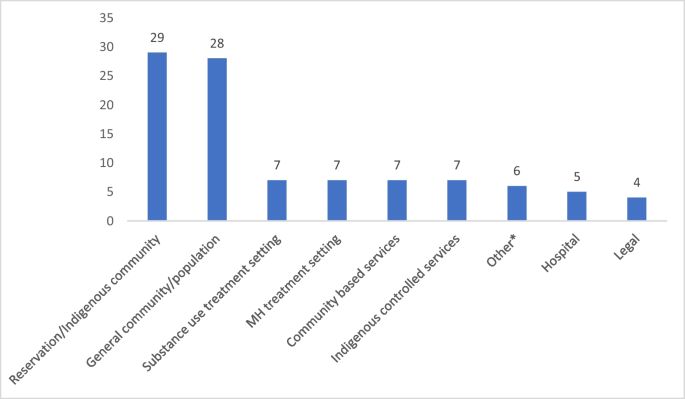

Sixty-nine (73%) of the included studies included only Indigenous participants, while the remaining 25 (27%) included both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. Only one study had a sample where more than 50% were Indigenous with the outcomes combining both Indigenous and non-Indigenous data (Woodall et al., 2007 ). The remaining studies that included non-Indigenous participants reported the findings separately for the Indigenous participants. The sample ranged from 15 to 16,640 Indigenous participants, with an average of 1387. Most studies were conducted within Indigenous communities/reservations ( n = 33, 35%) or a general/population-based sample ( n = 28, 30%), of which two studies were conducted within the general population and a reservation (see Fig. 4 ).

The number of studies examining mental health conditions with alcohol and other drug use by setting. Note: Some studies included multiple settings and have been counted multiple times. *“Other” settings included a homeless community, veteran affairs services, education facilities, and a remote area mental health service database

The number of studies examining co-occurring MH conditions and substance use in Indigenous peoples has increased over time; however, the average number of publications per year was low. This modest increase does not reflect the growth in research outputs in Indigenous health generally in recent decades (Bryant et al., 2022 ; Derrick et al., 2012 ; Kennedy et al., 2022 ), which has been coupled with growing investment and capacity in the MH field for Indigenous peoples in several countries. A recent review of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health in Australia found that 20.5% of all Indigenous health research conducted from 2008 to 2020 was focussed on MH or substance use disorders (Kennedy et al., 2022 ). There was a peak for paper outputs in 2006. These publications reported on studies that were conducted across a range of years, from 1994 to 2004. Furthermore, nine papers published in 2006 reported the outcomes for four individual studies. Although it is difficult to interpret the reasons for the 2006 peak in paper publications, it may reflect researchers’ capacity to publish in a timely manner rather than any policy or funding factors.

Included studies explored a range of comorbidities. It was common for studies to include generalised groupings of MH conditions or substance use. The co-occurrence of depression and alcohol use was the most examined comorbidity, which likely reflects the high prevalence of both of these conditions (GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators, 2018 ; Liu et al., 2020 ). There has been limited exploration of substance use with MH conditions such as eating disorders or bipolar disorders. Similarly, MH comorbidities with opioids and stimulants have been limited, although it is likely that these substances have been included in some studies which have explored general substance use. There is significant scope for research exploring several co-occurring MH conditions and substances among Indigenous people, for both prevalence and prevention or treatment strategies. The method of measuring conditions is an important consideration for future research to ensure accuracy in the data provided. While measurement of MH conditions and substance use varied across the studies, this was primarily conducted via diagnostic clinical interviews. This method provides clinical accuracy; however, it may not account for subthreshold symptoms, which have been found to be a significant contributor to burden and disability (Rai et al., 2010 ). The use of validated MH and substance use measures, which allow for exploration of different levels of severity, may therefore be more relevant for understanding comorbidity burden in Indigenous communities rather than via diagnostic interviews.

A substantial majority of the studies were conducted within the US. The output across countries can likely be attributed to variation in research capacity and support. The US was ranked number one for research outputs from 1996 to 2021, far surpassing Canada, Australia, and Aotearoa’s outputs combined (SCImago, 2022 ). In addition, leading US mental health groups have advocated for addressing co-occurring MH conditions and substance use, as well as a need for integrated health systems (Mental Health America, 2017 ; Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration, 2022 ). This review highlights the need for increased research capacity in co-occurring MH conditions and substance use within distinct and unique Indigenous communities in most countries.

Experimental research is important for providing robust evidence for the effectiveness of treatment approaches. However, only two experimental studies (2%) were identified in this review. This finding is similar to a recent review that found only 2.7% of research on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health in Australia used an experimental design (Kennedy et al., 2022 ). Qualitative research was also only utilised in two identified studies. Qualitative research is important for understanding the views and perceptions of Indigenous people (Auger, 2016 ). It allows insight into the factors that contribute to the co-occurrence of MH conditions and substance use and can better inform future research, policy, and practice. Further investment in Indigenous-led qualitative research is needed to allow for Indigenous people’s knowledge and experience to inform future prevention and treatment-focussed research in this field.

Future Directions

There is a need to increase research examining co-occurring MH conditions and substance use to break down the existing silos in research and treatment and promote integrated care for Indigenous peoples. While consideration of international research can provide some guidance on co-occurring MH conditions and substance use, the unique and diverse Indigenous communities within and between countries require localised data to inform healthcare delivery and policy. Despite several quantitative studies within the US, consideration of prevalence is still needed for all countries to inform needs within distinct communities, specific comorbidities, gender, and age groups. This scoping review intended to provide a surface-level understanding of MH conditions and substance use comorbidity among Indigenous people; however, more in-depth exploration of the research in this area should be considered, such as assessing the quality of quantitative studies and the cultural appropriateness of measures examining MH conditions and substance use. Qualitative research is an important avenue for future work, which will allow for a deeper understanding of strategies for prevention and care that are important for local Indigenous communities. This should be followed by robustly designed experiment studies testing the effectiveness of strategies to prevent and manage co-occurring conditions. Ensuring holistic strategies are developed, accounting for the wider social context in which Indigenous people exist, is also important. This includes consideration of systemic racism and the ongoing, pervasive impact of colonisation.

Limitations

For pragmatic reasons, the search for relevant studies was limited to the English language, which resulted in two studies published in other languages being omitted. This may have included studies that have been published in Indigenous languages. While the search strategy was designed to be broad and capture relevant studies, the diversity of Indigenous groups globally, with hundreds of unique tribes, nations, and clans, may have meant that some studies may have been missed. It was also not possible for the title and abstract screening to be conducted independently by two reviewers in parallel due to staffing constraints, and therefore, this was done sequentially. Nevertheless, all papers returned in the search did undergo independent coding by at least two reviewers. One study did not report outcomes separately for Indigenous and non-Indigenous participants, so some non-Indigenous data was included in the results. However, more than half the participants in this study were Indigenous.

Research commitment and expertise in exploring comorbidity prevention and treatment strategies for Indigenous people is needed. This scoping review highlights several gaps in the field of co-occurring MH conditions and substance use among Indigenous peoples. This includes limited research conducted with Indigenous groups outside of the US and a lack of qualitative or experimental research. Further work is needed to understand the extent and impact of comorbidity among Indigenous people. Future studies should be Indigenous-led with locally informed strategies as well as consultation with Indigenous communities.

Data Availability

Extracted data relevant to the study is available in the Supplementary File ( S1 ).

Almeida, O. P., Flicker, L., Fenner, S., Smith, K., Hyde, Z., Atkinson, D., Skeaf, L., Malay, R., & LoGiudice, D. (2014). The Kimberley assessment of depression of older Indigenous Australians: Prevalence of depressive disorders, risk factors and validation of the KICA-dep scale. PLoS ONE, 9 (4), e94983.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Amu, H., Osei, E., Kofie, P., Owusu, R., Bosoka, S. A., Konlan, K. D., Kim, E., Orish, V. N., Maalman, R.S.-E., & Manu, E. (2021). Prevalence and predictors of depression, anxiety, and stress among adults in Ghana: A community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE, 16 (10), e0258105.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Auger, M. (2016). Cultural continuity as a determinant of Indigenous peoples’ health: A metasynthesis of qualitative research in Canada and the United States. The International Indigenous Policy Journal , 7 (4). https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2016.7.4.3

Australian Government. (2017). National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing 2017–2023. https://www.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/mhsewb-framework_0.pdf . Accessed 18 July 2023

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2016). Australian burden of disease study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2011. Canberra: AIHW. Australian Government. https://doi.org/10.25816/xd60-4366

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2022). Determinants of health for Indigenous Australians. AIHW, Australian Government. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/social-determinants-and-indigenous-health . Accessed 18 July 2023

Baxter, J., Kingi, T. K., Tapsell, R., Durie, M., & McGee, M. A. (2006). Prevalence of mental disorders among Maori in Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand mental health survey. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40 (10), 914–923. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1614.2006.01911.x

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Beals, J., Manson, S. M., Whitesell, N. R., Spicer, P., Novins, D. K., & Mitchell, C. M. (2005). Prevalence of DSM-IV disorders and attendant help-seeking in 2 American Indian reservation populations. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62 (1), 99–108.

Beals, J., Novins, D. K., Spicer, P., Whitesell, N. R., Mitchell, C. M., Manson, S. M., Amer Indian Service, U. (2006). Help seeking for substance use problems in two American Indian reservation populations. Psychiatric Services, 57 (4), 512–520. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.57.4.512

Beals, J., Piasecki, J., Nelson, S., Jones, M., Keane, E., Dauphinais, P., Red Shirt, R., Sack, W. H., & Manson, S. M. (1997). Psychiatric disorder among American Indian adolescents: Prevalence in Northern Plains youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36 (9), 1252–1259. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199709000-00018

Article CAS Google Scholar

Biegel, D. E., Ishler, K. J., Katz, S., & Johnson, P. (2007). Predictors of burden of family caregivers of women with substance use disorders or co-occurring substance and mental disorders. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 7 (1–2), 25–49. https://doi.org/10.1300/J160v07n01_03

Article Google Scholar

Bryant, J., Freund, M., Ries, N., Garvey, G., McGhie, A., Zucca, A., Hoberg, H., Passey, M., & Sanson-Fisher, R. (2022). Volume, scope, and consideration of ethical issues in Indigenous cognitive impairment and dementia research: A systematic scoping review of studies published between 2000–2021. Dementia, 21 (8), 2647–2676. https://doi.org/10.1177/14713012221119594

Burns, L., & Teesson, M. (2002). Alcohol use disorders comorbid with anxiety, depression and drug use disorders: Findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well Being. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 68 (3), 299–307.

Cao, L., Burton, V. S., Jr., & Liu, L. (2018). Correlates of illicit drug use among Indigenous peoples in Canada: A test of social support theory. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62 (14), 4510–4527. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624x18758853

Charlson, F., Gynther, B., Obrecht, K., Waller, M., & Hunter, E. (2021). Multimorbidity and vulnerability among those living with psychosis in Indigenous populations in Cape York and the Torres Strait. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 55 (9), 892–902. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867420984832

Cheng, A. T., Gau, S.-F., Chen, T. H., Chang, J.-C., & Chang, Y.-T. (2004). A 4-year longitudinal study on risk factors for alcoholism. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61 (2), 184–191.

Chisolm, D. J., Mulatu, M. S., & Brown, J. R. (2009). Racial/ethnic disparities in the patterns of co-occurring mental health problems in adolescents in substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 37 (2), 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2008.11.005

Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care. (2017). What study designs should be included in an EPOC review? EPOC resources for review authors . https://epoc.cochrane.org/resources/epoc-resources-review-authors . Accessed 18 July 2023

Condon, J., Robinson, G., Trauer, T., & Nagel, T. (2009). Approach to treatment of mental illness and substance dependence in remote Indigenous communities: Results of a mixed methods study. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 17 (4), 174–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1584.2009.01060.x

Costello, E. J., Farmer, E. M., Angold, A., Burns, B. J., & Erkanli, A. (1997). Psychiatric disorders among American Indian and white youth in Appalachia: The Great Smoky Mountains Study. American Journal of Public Health, 87 (5), 827–832.

Coughlin, L. N., Lin, L. A., Jannausch, M., Ilgen, M. A., & Bonar, E. E. (2021). Methamphetamine use among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 227 , 108921.

Cunningham, J. K., Solomon, T. G. A., Ritchey, J., & Muramoto, M. L. (2022). Dual diagnosis and alcohol/nicotine use disorders: Native American and White hospital patients in 3 States. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 62 (2), e107–e116.

De Nadai, A. S., Little, T. B., McCabe, S. E., & Schepis, T. S. (2019). Diverse diagnostic profiles associated with prescription opioid use disorder in a nationwide sample: One crisis, multiple needs. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87 (10), 849.

Derrick, G. E., Hayen, A., Chapman, S., Haynes, A. S., Webster, B. M., & Anderson, I. (2012). A bibliometric analysis of research on Indigenous health in Australia, 1972–2008. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 36 (3), 269–273.

Deters, P. B., Novins, D. K., Fickenscher, A., & Beals, J. (2006). Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology: Patterns among American Indian adolescents in substance abuse treatment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76 (3), 335–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.76.3.335

Dharmawardene, V., & Menkes, D. B. (2015). Substance use disorders in New Zealand adults with severe mental illness: Descriptive study of an acute inpatient population. Australasian Psychiatry, 23 (3), 236–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856215586147

Dickerson, D. L., O’Malley, S. S., Canive, J., Thuras, P., & Westermeyer, J. (2009). Nicotine dependence and psychiatric and substance use comorbidities in a sample of American Indian male veterans. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 99 (1–3), 169–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.07.014

Dillard, D., Jacobsen, C., Ramsey, S., & Manson, S. (2007). Conduct disorder, war zone stress, and war-related posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in American Indian Vietnam veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20 (1), 53–62.

Dingwall, K. M., & Cairney, S. (2011). Detecting psychological symptoms related to substance use among Indigenous Australians. Drug and Alcohol Review, 30 (1), 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00194.x

Ducci, F., Enoch, M.-A., Funt, S., Virkkunen, M., Albaugh, B., & Goldman, D. (2007). Increased anxiety and other similarities in temperament of alcoholics with and without antisocial personality disorder across three diverse populations. Alcohol, 41 (1), 3–12.

Duclos, C. W., Beals, J., Novins, D. K., Martin, C., Jewett, C. S., & Manson, S. M. (1998). Prevalence of common psychiatric disorders among American Indian adolescent detainees. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 37 (8), 866–873.

Duncan, Z., Kippen, R., Sutton, K., Ward, B., Agius, P. A., Quinn, B., & Dietze, P. (2021). Correlates of anxiety and depression in a community cohort of people who smoke methamphetamine. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 56 (8), 964–973. https://doi.org/10.1177/00048674211048152

Duran, B., Sanders, M., Skipper, B., Waitzkin, H., Malcoe, L. H., Paine, S., & Yager, J. (2004). Prevalence and correlates of mental disorders among Native American women in primary care. American Journal of Public Health, 94 (1), 71–77.

Ebadi, A., & Schiffauerova, A. (2016). How to boost scientific production? A statistical analysis of research funding and other influencing factors. Scientometrics, 106 (3), 1093–1116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1825-x

Ehlers, C. L., Gilder, D. A., Slutske, W. S., Lind, P. A., & Wilhelmsen, K. C. (2008). Externalizing disorders in American Indians: Comorbidity and a genome wide linkage analysis. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B-Neuropsychiatric Genetics, 147B (6), 690–698. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.b.30666

Ehlers, C. L., Gizer, I. R., Gilder, D. A., & Yehuda, R. (2013). Lifetime history of traumatic events in an American Indian community sample: Heritability and relation to substance dependence, affective disorder, conduct disorder and PTSD. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47 (2), 155–161.

Emerson, M. A., Moore, R. S., & Caetano, R. (2017). Association between lifetime posttraumatic stress disorder and past year alcohol use disorder among American Indians/Alaska Natives and Non-Hispanic Whites. Alcoholism-Clinical and Experimental Research, 41 (3), 576–584. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13322

Federman, E. B., Costello, E. J., Angold, A., Farmer, E. M., & Erkanli, A. (1997). Development of substance use and psychiatric comorbidity in an epidemiologic study of white and American Indian young adolescents the Great Smoky Mountains Study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 44 (2–3), 69–78.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Fisckenscher, A., & Novins, D. (2003). Gender differences and conduct disorder among American Indian adolescents in substance abuse treatment. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 35 (1), 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2003.10399997

Foliaki, S. A., Kokaua, J., Schaaf, D., Tukuitonga, C., Team, N. Z. M. H. S. R. (2006). Twelve-month and lifetime prevalences of mental disorders and treatment contact among Pacific people in Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40 (10), 924–934.

Gall, A., Anderson, K., Howard, K., Diaz, A., King, A., Willing, E., Connolly, M., Lindsay, D., & Garvey, G. (2021). Wellbeing of Indigenous peoples in Canada, Aotearoa (New Zealand) and the United States: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18 (11), 5832. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115832

GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators. (2018). Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet, 392 (10152), 1015–1035.

Gilder, D. A., & Ehlers, C. L. (2012). Depression symptoms associated with cannabis dependence in an adolescent American Indian community sample. The American Journal on Addictions, 21 (6), 536–543.

Gilder, D. A., Lau, P., Corey, L., & Ehlers, C. L. (2008). Factors associated with remission from alcohol dependence in an American Indian community group. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165 (9), 1172–1178.

Gilder, D. A., Lau, P., Dixon, M., Corey, L., Phillips, E., & Ehlers, C. L. (2006). Co-morbidity of select anxiety, affective, and psychotic disorders with cannabis dependence in Southwest California Indians. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 25 (4), 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1300/J069v25n04_07

Gilder, D. A., Stouffer, G. M., Lau, P., & Ehlers, C. L. (2016). Clinical characteristics of alcohol combined with other substance use disorders in an American Indian community sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 161 , 222–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.006

Gilder, D. A., Wall, T. L., & Ehlers, C. L. (2004). Comorbidity of select anxiety and affective disorders with alcohol dependence in Southwest California Indians. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research, 28 (12), 1805–1813.

Greenfield, B. L., Sittner, K. J., Forbes, M. K., Walls, M. L., & Whitbeck, L. B. (2017). Conduct disorder and alcohol use disorder trajectories, predictors, and outcomes for indigenous youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 56 (2), 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.11.009

Gummattira, P., Cowan, K. A., Averill, K. A., Malkina, S., Reilly, E. L., Krajewski, K., Rocha, D., & Averill, P. M. (2010). A comparison between patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder with versus without comorbid substance abuse. Addictive Disorders & Their Treatment, 9 (2), 53–63.

Harris, P., Taylor, R., Minor, B., Elliott, V., Fernandez, M., O’Neal, L., McLeod, L., Delacqua, G., Delacqua, F., Kirby, J., Duda, S., & REDCap Consortium. (2019). The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 95 (103208). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

Hartshorn, K. J. S., Whitbeck, L. B., & Prentice, P. (2015). Substance use disorders, comorbidity, and arrest among Indigenous adolescents. Crime & Delinquency, 61 (10), 1311–1332. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128712466372

Hautala, D., Sittner, K., & Walls, M. (2019). Onset, comorbidity, and predictors of nicotine, alcohol, and marijuana use disorders among North American Indigenous adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47 (6), 1025–1038.

He, Q., Yang, L., Shi, S., Gao, J., Tao, M., Zhang, K., Gao, C., Yang, L., Li, K., Shi, J., Wang, G., Liu, L., Zhang, J., Du, B., Jiang, G., Shen, J., Zhang, Z., Liang, W., Sun, J., … Flint, J. (2014). Smoking and major depressive disorder in Chinese women. PloS one, 9 (9), e106287. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0106287

Heaton, L. L. (2018). Racial/ethnic differences of justice-involved youth in substance-related problems and services received. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 88 (3), 363–375. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000312

Heffernan, E., Andersen, K., Davidson, F., & Kinner, S. A. (2015). PTSD among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in custody in Australia: Prevalence and correlates. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28 (6), 523–530. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22051

Hesselbrock, M. N., Segal, B., & Malcolm, B. P. (2006). Multiple substance dependence and course of alcoholism among Alaska native men and women. Substance Use and Misuse, 41 (5), 729–741. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080500391803

Hesselbrock, V. M., Segal, B., & Hesselbrock, M. N. (2000). Alcohol dependence among Alaska Natives entering alcoholism treatment: A gender comparison. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 61 (1), 150–156.

Hodge, D. R., Limb, G. E., & Cross, T. L. (2009). Moving from colonization toward balance and harmony: A Native American perspective on wellness. Social Work, 54 (3), 211–219. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/54.3.211

Howard, M. O., Walker, R. D., Suchinsky, R. T., & Anderson, B. (1996). Substance-use and psychiatric disorders among American Indian veterans. Substance Use & Misuse, 31 (5), 581–598. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826089609045828

Huang, B., Grant, B. F., Dawson, D. A., Stinson, F. S., Chou, S. P., Saha, T. D., Goldstein, R. B., Smith, S. M., Ruan, W. J., & Pickering, R. P. (2006). Race-ethnicity and the prevalence and co-occurrence of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, alcohol and drug use disorders and Axis I and II disorders: United States, 2001 to 2002. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 47 (4), 252–257.

Hunter, E., Gynther, B., Anderson, C., Onnis, L.-A., Groves, A., & Nelson, J. (2011). Psychosis and its correlates in a remote indigenous population. Australasian Psychiatry : Bulletin of Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 19 (5), 434–438. https://doi.org/10.3109/10398562.2011.583068

Kaholokula, J. K., Grandinetti, A., Crabbe, K. M., Chang, H. K., & Kenui, C. K. (1999). Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking among Native Hawaiians. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health, 11 (2), 60–64.

Kennedy, M., Bennett, J., Maidment, S., Chamberlain, C., Booth, K., McGuffog, R., Hobden, B., Whop, L. J., & Bryant, J. (2022). Interrogating the intentions for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health: A narrative review of research outputs since the introduction of Closing the Gap. MJA, 217 (1), 50–57.

PubMed Google Scholar

Kisely, S., Alichniewicz, K. K., Black, E. B., Siskind, D., Spurling, G., & Toombs, M. (2017). The prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders in indigenous people of the Americas: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 84 , 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.09.032

Kunitz, S. J., Gabriel, K. R., Levy, J. E., Henderson, E., Lampert, K., McCloskey, J., Quintero, G., Russell, S., & Vince, A. (1999). Alcohol dependence and conduct disorder among Navajo Indians. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 60 (2), 159–167.

Lacey, C., Cunningham, R., Rijnberg, V., Manuel, J., Clark, M. T. R., Keelan, K., Pitama, S., Huria, T., Lawson, R., & Jordan, J. (2020). Eating disorders in New Zealand: Implications for Maori and health service delivery. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53 (12), 1974–1982. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23372

Lee, K. K., Clough, A. R., Jaragba, M. J., Conigrave, K. M., & Patton, G. C. (2008). Heavy cannabis use and depressive symptoms in three Aboriginal communities in Arnhem Land. Northern Territory. Medical Journal of Australia, 188 (10), 605–608.

Lee, K. S. K., Harrison, K., Mills, K., & Conigrave, K. M. (2014). Needs of Aboriginal Australian women with comorbid mental and alcohol and other drug use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Review, 33 (5), 473–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12127

Leung, J., Stockings, E., Wong, I., Galasyuk, N., Diminic, S., Leitch, E., Whiteford, H., Degenhardt, L., Ritter, A., & Harris, M. (2016). Co-morbid mental and substance use disorders – a meta-review of treatment effectiveness. NDARC Technical Report No. 336. https://ndarc.med.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/ndarc/resources/NDARCTechinicalReport_ComorbidMSDMetaReviewFinal_20170913_0.pdf

Libby, A. M., Orton, H. D., Barth, R. P., Webb, M. B., Burns, B. J., Wood, P., & Spicer, P. (2006). Alcohol, drug, and mental health specialty treatment services and race/ethnicity: A national study of children and families involved with child welfare. American Journal of Public Health, 96 (4), 628–631. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2004.059436

Libby, A. M., Orton, H. D., Novins, D. K., Beals, J., Manson, S. M., & Ai-Superpfp, T. (2005). Childhood physical and sexual abuse and subsequent depressive and anxiety disorders for two American Indian tribes. Psychological Medicine, 35 (3), 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291704003599

Libby, A. M., Orton, H. D., Novins, D. K., Spicer, P., Buchwald, D., Beals, J., Manson, S. M., & Ai-Superpfp, T. (2004). Childhood physical and sexual abuse and subsequent alcohol and drug use disorders in two American-Indian tribes. Journal of studies on alcohol, 65 (1), 74–83. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2004.65.74

Lillie, K. M., Shaw, J., Jansen, K. J., & Garrison, M. M. (2021). Buprenorphine/naloxone for opioid use disorder among Alaska Native and American Indian people. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 15 (4), 297–302. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000757

Liu, Q., He, H., Yang, J., Feng, X., Zhao, F., & Lyu, J. (2020). Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 126 , 134–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.08.002

Mark, G. T., & Lyons, A. C. (2010). Maori healers’ views on wellbeing: The importance of mind, body, spirit, family and land. Social Science & Medicine, 70 (11), 1756–1764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.001

McCartney, M. (2016). Breaking down the silo walls. BMJ open, 354 (i5199). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i5199

Mellsop, G., Tapsell, R., Holmes, P., & Andreasson, B. B. B. C. D. F. E. F. J. K. K. M. M. M. P. R. S. T. T. (2019). Mental health service users’ progression from illicit drug use to schizophrenia in New Zealand. General Psychiatry, 32 (5), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2019-100088

Mental Health America. (2017). Position statement 16: Addressing the health- related social needs of people with mental health and substance use conditions . https://www.mhanational.org/issues/position-statement-16-addressing-health-related-social-needs-people-mental-health-and#_edn2 . Accessed 17 July 2023

Mercer, S., O’Brien, R., Fitzpatrick, B., Higgins, M., Guthrie, B., Watt, G., & Wyke, S. (2016). The development and optimisation of a primary care-based whole system complex intervention (CARE Plus) for patients with multimorbidity living in areas of high socioeconomic deprivation. Chronic Illness, 12 (3), 165–181.

Ministry of Health New Zealand. (2018). Mental health - Maori Health Statistics . New Zealand Government. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/populations/maori-health/tatau-kahukura-maori-health-statistics/nga-mana-hauora-tutohu-health-status-indicators/mental-health . Accessed 18 July 2023

Moghaddam, J. F., Dickerson, D. L., Yoon, G., & Westermeyer, J. (2014). Nicotine dependence and psychiatric and substance use disorder comorbidities among American Indians/Alaska Natives: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 144 , 127–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.08.017

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18 (1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Nadew, G. T., & Tatsioni, T. (2012). Exposure to traumatic events, prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol abuse in Aboriginal communities. Rural and Remote Health, 12 (4), 1–12.

Google Scholar

Nasir, B. F., Ryan, E. G., Black, E. B., Kisely, S., Gill, N. S., Beccaria, G., Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan, S., Nicholson, G. C., & Toombs, M. (2022). The risk of common mental disorders in Indigenous Australians experiencing traumatic life events. BJPsych Open , 8 (1). https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.1063

Nasir, B. F., Toombs, M. R., Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan, S., Kisely, S., Gill, N. S., Black, E., Hayman, N., Ranmuthugala, G., Beccaria, G., Ostini, R., & Nicholson, G. C. (2018). Common mental disorders among Indigenous people living in regional, remote and metropolitan Australia: A cross-sectional study. BMJ open , 8 (6). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020196

Neligh, G., Baron, A. E., Braun, P., & Czarnecki, M. (1990). Panic disorder among American Indians: A descriptive study. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research , 4 (2), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.5820/aian.0402.1990.43

Nelson, S. E., & Wilson, K. (2017). The mental health of Indigenous peoples in Canada: A critical review of research. Social Science & Medicine, 176 , 93–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.021

Novins, D. K., Fickenscher, A., & Manson, S. M. (2006). American Indian adolescents in substance abuse treatment: Diagnostic status. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 30 (4), 275–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2005.12.005

O’Neill, L., Fraser, T., Kitchenham, A., & McDonald, V. (2018). Hidden burdens: A review of intergenerational, historical and complex trauma, implications for indigenous families. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 11 (2), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-016-0117-9

Onell, T. D. (1992). Feeling worthless - an ethnographic investigation of depression and problem drinking at the Flathead Reservation. Culture Medicine and Psychiatry, 16 (4), 447–469.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372 , n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Pearson, C. R., Kaysen, D., Belcourt, A., Stappenbeck, C. A., Zhou, C., Smartlowit-Briggs, M. L., & Whitefoot, M. P. (2015). Post-traumatic stress disorder and HIV risk behaviors among rural American Indian/Alaska Native women. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research (online), 22 (3), 1.

Pro, G., Baldwin, J. A., Utter, J., & Haberstroh, S. (2020). Dual mental health diagnoses predict the receipt of medication-assisted opioid treatment: Associations moderated by state Medicaid expansion status, race/ethnicity and gender, and year. Drug and alcohol dependence, 209 , 107952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.107952

Quello, S., Brady, K., & Sonne, S. (2005). Mood disorders and substance use disorder: A complex comorbidity. Sci Pract Perspect, 3 (1), 13–21.

Rai, D., Skapinakis, P., Wiles, N., Lewis, G., & Araya, R. (2010). Common mental disorders, subthreshold symptoms and disability: Longitudinal study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 197 (5), 411–412.

Rieckmann, T., McCarty, D., Kovas, A., Spicer, P., Bray, J., Gilbert, S., & Mercer, J. (2012). American Indians with substance use disorders: Treatment needs and comorbid conditions. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 38 (5), 498–504. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2012.694530

Robin, R. W., Long, J. C., Rasmussen, J. K., Albaugh, B., & Goldman, D. (1998). Relationship of binge drinking to alcohol dependence, other psychiatric disorders, and behavioral problems in an American Indian tribe. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research, 22 (2), 518–523.

Sawchuk, C. N., Roy-Byrne, P., Noonan, C., Bogart, A., Goldberg, J., Manson, S. M., & Buchwald, D. (2012). Smokeless Tobacco use and its relation to panic disorder, major depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder in American Indians. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 14 (9), 1048–1056. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr331

Sawchuk, C. N., Roy-Byrne, P., Noonan, C., Bogart, A., Goldberg, J., Manson, S. M., Buchwald, D., Ai-Superpfp, T., & Abelson, B. B. B. B. B. B. B. B. C. C. C. D. D. E. F. F. G. G. G. G. G. J. J. J. K. K. K. K. K. L. (2016). The association of panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and major depression with smoking in American Indians. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 18 (3), 259–266. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntv071

Sawchuk, C. N., Roy-Byrne, P., Noonan, C., Craner, J. R., Goldberg, J., Manson, S., & Buchwald, D. (2017). Panic attacks and panic disorder in the American Indian community. Journal of anxiety disorders, 48 , 6–12.

Schick, M. R., Nalven, T., Thomas, E. D., Weiss, N. H., & Spillane, N. S. (2022). Depression and alcohol use in American Indian adolescents: The influence of family factors. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research, 46 (1), 141–151.

Schütz, C., Choi, F., Jae Song, M., Wesarg, C., Li, K., & Krausz, M. (2019). Living with dual diagnosis and homelessness: Marginalized within a marginalized group. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 15 (2), 88–94.

SCImago. (2022). SCImago Journal & Country Rank . Scimago Lab. Retrieved 24 Mar from https://www.scimagojr.com/countryrank.php?order=itp&ord=desc

September, U., & Beytell, A.-M. (2019). Family members’ experiences: People with comorbid bipolar and substance use disorder. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17 (5), 1162–1179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-0037-z

Shen, Y.-T., Radford, K., Daylight, G., Cumming, R., Broe, T. G., & Draper, B. (2018). Depression, suicidal behaviour, and mental disorders in older Aboriginal Australians. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15 (3), 447.

Smith, S. M., Stinson, F. S., Dawson, D. A., Goldstein, R., Huang, B., & Grant, B. F. (2006). Race/ethnic differences in the prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychological Medicine, 36 (7), 987–998.

Somervell, P. D., Beals, J., Kinzie, J. D., Boehnlein, J., Leung, P., & Manson, S. M. (1992). Use of the CES-D in an American Indian village. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 16 (4), 503–517.

Subica, A. M., Aitaoto, N., Link, B. G., Yamada, A. M., Henwood, B. F., & Sullivan, G. (2019). Mental health status, need, and unmet need for mental health services among US Pacific Islanders. Psychiatric Services, 70 (7), 578–585. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800455

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2022). Co-occurring disorders: Diagnoses and integrated treatments . SAMHSA. Retrieved 24 Mar from https://www.samhsa.gov/co-occurring-disorders . Accessed 17 July 2023

Tan, M. C., Thuras, P., Thompson, J., Canive, J., & Westermeyer, J. (2008). Sustained remission from substance use disorder among American Indian veterans. Addictive Disorders and Their Treatment, 7 (2), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADT.0b013e31805ea0ad

Te Kōmihana Whai Hua O Aotearoa (New Zealand Productivity Commission). (2022). Colonisation, Racism and Wellbeing . Haemata Limited. https://www.productivity.govt.nz/assets/Documents/NZPC_Colonisation_Racism_Wellbeing_Final.pdf . Accessed 18 July 2023

Teesson, M., Baker, A., Deady, M., Mills, K., Kay-Lambkin, F., Haber, P., Baillie, A., Christensen, H., Birchwood, M., Spring, B., Brady, K. T., Manns, L., & Gournay, K. (2014). Mental health and substance use: Opportunities for innovative prevention and treatment . Mental Health Commission of NSW, Sydney. https://www.nswmentalhealthcommission.com.au/sites/default/files/old/assets/File/NSW%20MHC%20Discussion%20document%20on%20comorbidity%20cover%20page.pdf

Toombs, E., Lund, J., Radford, A., Drebit, M., Bobinski, T., & Mushquash, C. J. (2022). Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and health histories among clients in a first nations-led treatment for substance use. International journal of mental health and addiction , pp. 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00883-1

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169 (7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-0850

Verma, R. K., Guen Lin, R. S., Chakravarthy, S., Barua, A., & Kar, N. (2014). Socio-demographic correlates of unipolar major depression among the Malay elderly in Klang Valley, Malaysia an intensive study. International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 6 (4), 158–164.

Walls, M., Sittner, K. J., Whitbeck, L. B., Herman, K., Gonzalez, M., Elm, J. H. L., Hautala, D., Dertinger, M., & Hoyt, D. R. (2020). Prevalence of mental disorders from adolescence through early adulthood in American Indian and First Nations communities. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00304-1

Wasserman, G. A., McReynolds, L. S., Schwalbe, C. S., Keating, J. M., & Jones, S. A. (2010). Psychiatric disorder, comorbidity, and suicidal behavior in juvenile justice youth. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37 (12), 1361–1376.

Westermeyer, J. (1993). Psychiatric disorders among American Indian vs other patients with psychoactive substance use disorders. American Journal on Addictions, 2 (4), 309–314.

Westermeyer, J., & Canive, J. (2013). Posttraumatic stress disorder and its comorbidities among American Indian veterans. Community Mental Health Journal, 49 (6), 704–708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-012-9565-3

Westermeyer, J., Canive, J., Thuras, P., Thompson, J., Crosby, R. D., & Garrard, J. (2009). A comparison of substance use disorder severity and course in American Indian male and female veterans. The American Journal on Addictions, 18 (1), 87–92.

Westermeyer, J., Neider, J., & Westermeyer, M. (1992). Substance use and other psychiatric-disorders among 100 American-Indian patients. Culture Medicine and Psychiatry, 16 (4), 519–529.

Wheeler, A., Robinson, E., & Robinson, G. (2005). Admissions to acute psychiatric inpatient services in Auckland, New Zealand: A demographic and diagnostic review. The New Zealand Medical Journal (Online) , 118 (1226). https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/2292/4725/16311610.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Whitbeck, L., Hoyt, D., Johnson, K., & Chen, X. (2006a). Mental disorders among parents/caretakers of American Indian early adolescents in the Northern Midwest. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41 (8), 632–640.

Whitbeck, L. B., Johnson, K. D., Hoyt, D. R., & Walls, M. L. (2006c). Prevalence and comorbidity of mental disorders among American Indian children in the Northern Midwest. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39 (3), 427–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.01.004

Whitesell, N. R., Beals, J., Mitchell, C. M., Keane, E. M., Spicer, P., & Turner, R. J. (2007). The relationship of cumulative and proximal adversity to onset of substance dependence symptoms in two American Indian communities. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 91 (2–3), 279–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.008

Woodall, W. G., Delaney, H. D., Kunitz, S. J., Westerberg, V. S., & Zhao, H. (2007). A randomized trial of a DWI intervention program for first offenders: Intervention outcomes and interactions with antisocial personality disorder among a primarily American-Indian sample. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research, 31 (6), 974–987.

World Health Organization. (1993). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: diagnostic criteria for research. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37108

World Health Organization. (2019). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and related health problems, 11th Revision (ICD-11) . World Health Organization. https://icd.who.int/en

Wu, L.-T., Blazer, D. G., Gersing, K. R., Burchett, B., Swartz, M. S., & Mannelli, P. (2013). Comorbid substance use disorders with other Axis I and II mental disorders among treatment-seeking Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders, and mixed-race people. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47 (12), 1940–1948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.08.022

Wu, L.-T., Zhu, H., Mannelli, P., & Swartz, M. S. (2017). Prevalence and correlates of treatment utilization among adults with cannabis use disorder in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 177 , 153–162.

Zhu, Z., Huang, H., Chen, H., Hao, W., Ning, K., Zhang, R., Sun, W., Li, B., Jiang, H., Wang, W., Du, J., Zhao, M., Yi, Z., Li, J., Zhu, R., Lu, S., Xie, S., Wang, X., Fu, W., & Gao, C. (2020). Prevalence, demographic, and clinical correlates of comorbid depressive symptoms in Chinese psychiatric patients with alcohol dependence. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11 , 499. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00499

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Samuel Lawson (research assistant) for assisting with data coding and Angela Smith (librarian) for assisting with the development of the search strategy.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions BH is supported by an Australian Rotary Health Colin Dodds Postdoctoral Fellowship (#1801108). This project did not receive funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Health Behaviour Research Collaborative, School of Medicine and Public Health, College of Health, Medicine and Wellbeing, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW, 2308, Australia

Breanne Hobden, Megan Freund, Todd Heard, Robert Davis, Jia Ying Ooi, Rob Sanson-Fisher & Jamie Bryant

Equity in Health and Wellbeing Program, Hunter Medical Research Institute, New Lambton Heights, NSW, 2305, Australia

Breanne Hobden, Megan Freund, Robert Davis, Jia Ying Ooi, Rob Sanson-Fisher & Jamie Bryant

Wollotuka Institute, Purai Global Indigenous History Centre, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, Australia

Jennifer Rumbel

Systems Neuroscience Group, Hunter Medical Research Institute, New Lambton Heights, NSW, 2305, Australia

Jennifer Rumbel & Todd Heard

Wiyiliin Ta CAMHS, Hunter New England Local Health District, NSW Health, Newcastle, 2300, Australia

Orange Aboriginal Medical Service, Orange, NSW, 2800, Australia

Jamie Newman

Yimamulinbinkaan Aboriginal Mental Health Service & Social Emotional Wellbeing Workforce Hunter, New England Mental Health Service, Hunter New England Local Health District, NSW Health, Warabrook, 2304, Australia

Bronwyn Rose

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and methodology. Paper coding was performed by Breanne Hobden, Jennifer Rumbel, and Jia Ying Ooi. Data extraction was performed by Breanne Hobden, Megan Freund, Jia Ying Ooi, and Jamie Bryant. Data analysis and synthesis was conducted by Breanne Hobden. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Breanne Hobden. All authors reviewed and commented on iterative versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Breanne Hobden .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval.

This is a review of available literature; therefore, ethics approval was not required.

Consent to Participate

This is a review of available literature; therefore, consent to participate and consent to publish were not required.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (XLSX 51 KB)

Appendix 1 search strategy.

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process, In-Data-Review & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily <1946 to October 11, 2022>

Search Strategy:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 exp Mental Disorders/ (1275030)

2 ((mental or psychologic* or emotional) adj (illness* or condition* or disorder* or health)).ti,ab,kw,kf. (241020)

3 (eating disorder* or anorexi* or bulimi*).ti,ab,kw,kf. (51634)

4 (disorder* adj1 mood).ti,ab,kw,kf. (19263)

5 (depression or depressive or dysthymi*).ti,ab,kw,kf. (404197)

6 (neurotic or neuros?s or psychoneuros?s or psycho-neuros?s).ti,ab,kw,kf. (17018)

7 (bipolar or bi-polar).ti,ab,kw,kf. (65793)

8 affective disorder*.ti,ab,kw,kf. (17230)

9 anxiety.ti,ab,kw,kf. (207161)

10 (panic adj (disorder* or attack*)).ti,ab,kw,kf. (11506)

11 (phobia* or phobic disorder* or arachnophobia* or acrophobi* or claustrophobi*).ti,ab,kw,kf. (10310)

12 (stress adj1 (disorder* or acute)).ti,ab,kw,kf. (40074)

13 (post traumatic stress or posttraumatic stress or PTSD or psycho?trauma* or psychological trauma*).ti,ab,kw,kf. (41549)

14 (obsessive compulsive disorder or obsessive behavio?r* or compulsive behavio?r* or OCD).ti,ab,kw,kf. (16735)

15 (stress adj1 (disorder* or psychological or condition*)).ti,ab,kw,kf. (63542)

16 schizo*.ti,ab,kw,kf. (148918)

17 (paranoid or paranoia).ti,ab,kw,kf. (8448)

18 (psychotic or psychos?s).ti,ab,kw,kf. (73522)

19 (adjustment adj1 (emotional or disorder*)).ti,ab,kw,kf. (2782)

20 (personality adj1 disorder*).ti,ab,kw,kf. (20994)

21 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 (1820924)

22 exp Substance-related disorders/ (284659)

23 ((aerosol* or alcohol* or amphetamin* or barbituat* or benzodiazepin* or buprenorphin* or cannabi* or cocaine* or codeine or crack or crystal or depressant* or ecstasy or fentanyl or GHB or hallucinogen* or heroin* or hydromorphone or hypnotic* or inhalant* or ketamin* or LSD or marihuana* or marijuana* or MDMA or methadone or methamphetamin* or morphine* or narcotic* or nitrous oxide or opiate* or opioid* or opium or oxycodone or painkiller* or pain killer* or PCP or pethidin* or psychedelic* or psychoactive* or psychostimulant* or ritalin or sedative* or solvent* or steroid* or stimulant*) adj3 (abus* or use* or using* or misus* or mis-us* or depend* or addict* or illegal* or illicit* or habit* or intoxica* or in-toxica* or disorder* or condition* or illness*)).ti,ab,kw,kf. (279135)

24 ((drug* or chemical* or substance*) adj3 (abus* or use* or using* or misus* or mis-us* or depend* or addict* or illegal* or illicit* or habit* or intoxica* or in-toxica* or disorder*)).ti,ab,kw,kf. (367349)

25 ((prescription* or prescribed) adj3 (abus* or misus* or mis-us* or depend* or addict*)).ti,ab,kw,kf. (3507)

26 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 (717202)

27 exp Comorbidity/ (114881)

28 (comorbid* or co-morbid* or cooccurr* or co-occurr*).ti,ab,kw,kf. (221037)

29 (multimorbid* or multi-morbid*).ti,ab,kw,kf. (6638)

30 (coexist* or co-exist*).ti,ab,kw,kf. (98036)

31 "Diagnosis, Dual (Psychiatry)"/ (3622)

32 (dual adj2 diagnos*).ti,ab,kw,kf. (2331)

33 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 (386202)

34 exp Indians, North American/ or exp Indigenous Canadians/ or American Natives/ or Oceanic Ancestry Group/ (27937)

35 indigenous.ti,ab,kw,kf. (34356)

36 aborigin*.ti,ab,kw,kf. (10310)

37 (first nation or first nations or first people* or native population* or native people*).ti,ab,kw,kf. (4714)

38 torres strait islander*.ti,ab,kw,kf. (1793)

39 australoid race*.ti,ab,kw,kf. (3)

40 maori*.ti,ab,kw,kf. (3622)

41 (pacific islander* or south sea islander* or pacific island american*).ti,ab,kw,kf. (3882)

42 (native* adj1 (hawaiian* or polynesian*)).ti,ab,kw,kf. (1259)

43 ((north america* or american or alaska*) adj2 (native* or indian*)).ti,ab,kw,kf. (13195)

44 (amerind* or american indian*).ti,ab,kw,kf. (9120)

45 eskimo*.ti,ab,kw,kf. (1558)

46 (inuit* or meti or inupiat* or aleut* or yupik or athabaska*).ti,ab,kw,kf. (3200)

47 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46 (77476)

48 21 or 26 (2221807)

49 33 and 47 and 48 (555)

50 limit 49 to english language (547)

51 limit 50 to (comment or editorial or letter or news) (4)

52 50 not 51 (543)

Database: Embase <1947 to present>

1 exp mental disease/ (2441346)

2 ((mental or psychologic* or emotional) adj (illness* or condition* or disorder* or health)).ti,ab,kw. (302885)

3 (eating disorder* or anorexi* or bulimi*).ti,ab,kw. (75151)

4 (disorder* adj1 mood).ti,ab,kw. (30170)

5 (depression or depressive or dysthymi*).ti,ab,kw. (582832)

6 (neurotic or neuros?s or psychoneuros?s or psycho-neuros?s).ti,ab,kw. (24209)

7 (bipolar or bi-polar).ti,ab,kw. (99252)

8 affective disorder*.ti,ab,kw. (24768)

9 anxiety.ti,ab,kw. (307605)

10 (panic adj (disorder* or attack*)).ti,ab,kw. (15489)

11 (phobia* or phobic disorder* or arachnophobia* or acrophobi* or claustrophobi*).ti,ab,kw. (15304)

12 (stress adj1 (disorder* or acute)).ti,ab,kw. (50900)

13 (post traumatic stress or posttraumatic stress or PTSD or psycho?trauma* or psychological trauma*).ti,ab,kw. (54307)

14 (obsessive compulsive disorder or obsessive behavio?r* or compulsive behavio?r* or OCD).ti,ab,kw. (24522)

15 (stress adj1 (disorder* or psychological or condition*)).ti,ab,kw. (80289)

16 schizo*.ti,ab,kw. (207220)

17 (paranoid or paranoia).ti,ab,kw. (13769)

18 (psychotic or psychos?s).ti,ab,kw. (112382)

19 (adjustment adj1 (emotional or disorder*)).ti,ab,kw. (4166)

20 (personality adj1 disorder*).ti,ab,kw. (29138)

21 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 (2943948)

22 exp drug dependence/ or substance abuse/ (302956)

23 ((aerosol* or alcohol* or amphetamin* or barbituat* or benzodiazepin* or buprenorphin* or cannabi* or cocaine* or codeine or crack or crystal or depressant* or ecstasy or fentanyl or GHB or hallucinogen* or heroin* or hydromorphone or hypnotic* or inhalant* or ketamin* or LSD or marihuana* or marijuana* or MDMA or methadone or methamphetamin* or morphine* or narcotic* or nitrous oxide or opiate* or opioid* or opium or oxycodone or painkiller* or pain killer* or PCP or pethidin* or psychedelic* or psychoactive* or psychostimulant* or ritalin or sedative* or solvent* or steroid* or stimulant*) adj3 (abus* or use* or using* or misus* or mis-us* or depend* or addict* or illegal* or illicit* or habit* or intoxica* or in-toxica* or disorder* or condition* or illness*)).ti,ab,kw. (396550)

24 ((drug* or chemical* or substance*) adj3 (abus* or use* or using* or misus* or mis-us* or depend* or addict* or illegal* or illicit* or habit* or intoxica* or in-toxica* or disorder*)).ti,ab,kw. (517532)

25 ((prescription* or prescribed) adj3 (abus* or misus* or mis-us* or depend* or addict*)).ti,ab,kw. (5107)

26 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 (949786)

27 comorbidity/ (294387)

28 (comorbid* or co-morbid* or cooccurr* or co-occurr*).ti,ab,kw. (386102)

29 (multimorbid* or multi-morbid*).ti,ab,kw. (8998)

30 (coexist* or co-exist*).ti,ab,kw. (127917)

31 (dual adj2 diagnos*).ti,ab,kw. (3878)

32 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 (612625)

33 indigenous people/ or alaska native/ or american indian/ or canadian aboriginal/ or first nation/ or indigenous australian/ (29671)

34 indigenous.ti,ab,kw. (42404)

35 aborigin*.ti,ab,kw. (13451)

36 (first nation or first nations or first people* or native population* or native people*).ti,ab,kw. (6139)

37 torres strait islander*.ti,ab,kw. (2352)

38 australoid race*.ti,ab,kw. (9)

39 maori*.ti,ab,kw. (4686)

40 (pacific islander* or south sea islander* or pacific island american*).ti,ab,kw. (5565)

41 (native* adj1 (hawaiian* or polynesian*)).ti,ab,kw. (1569)

42 ((north america* or american or alaska*) adj2 (native* or indian*)).ti,ab,kw. (16645)

43 (amerind* or american indian*).ti,ab,kw. (11735)

44 eskimo*.ti,ab,kw. (1999)

45 (inuit* or meti or inupiat* or aleut* or yupik or athabaska*).ti,ab,kw. (3770)

46 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 (95627)

47 21 or 26 (3490245)

48 32 and 46 and 47 (858)

49 limit 48 to english language (849)

50 limit 49 to (books or chapter or conference abstract or conference paper or "conference review" or editorial or letter or note) (243)

51 49 not 50 (606)

Database: APA PsycInfo <1806 to October 11, 2022>

1 exp mental disorders/ (883496)

2 ((mental or psychologic* or emotional) adj (illness* or condition* or disorder* or health)).ti,ab,id. (296538)

3 (eating disorder* or anorexi* or bulimi*).ti,ab,id. (38535)

4 (disorder* adj1 mood).ti,ab,id. (17434)

5 (depression or depressive or dysthymi*).ti,ab,id. (301849)

6 (neurotic or neuros?s or psychoneuros?s or psycho-neuros?s).ti,ab,id. (27989)

7 (bipolar or bi-polar).ti,ab,id. (41378)

8 affective disorder*.ti,ab,id. (17980)

9 anxiety.ti,ab,id. (204692)

10 (panic adj (disorder* or attack*)).ti,ab,id. (12988)

11 (phobia* or phobic disorder* or arachnophobia* or acrophobi* or claustrophobi*).ti,ab,id. (13848)

12 (stress adj1 (disorder* or acute)).ti,ab,id. (42787)

13 (post traumatic stress or posttraumatic stress or PTSD or psycho?trauma* or psychological trauma*).ti,ab,id. (49364)

14 (obsessive compulsive disorder or obsessive behavio?r* or compulsive behavio?r* or OCD).ti,ab,id. (18248)

15 (stress adj1 (disorder* or psychological or condition*)).ti,ab,id. (46731)

16 schizo*.ti,ab,id. (131738)

17 (paranoid or paranoia).ti,ab,id. (13774)

18 (psychotic or psychos?s).ti,ab,id. (80976)

19 (adjustment adj1 (emotional or disorder*)).ti,ab,id. (4845)

20 (personality adj1 disorder*).ti,ab,id. (33681)

21 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 (1282281)

22 exp "substance use disorder"/ (133011)

23 ((aerosol* or alcohol* or amphetamin* or barbituat* or benzodiazepin* or buprenorphin* or cannabi* or cocaine* or codeine or crack or crystal or depressant* or ecstasy or fentanyl or GHB or hallucinogen* or heroin* or hydromorphone or hypnotic* or inhalant* or ketamin* or LSD or marihuana* or marijuana* or MDMA or methadone or methamphetamin* or morphine* or narcotic* or nitrous oxide or opiate* or opioid* or opium or oxycodone or painkiller* or pain killer* or PCP or pethidin* or psychedelic* or psychoactive* or psychostimulant* or ritalin or sedative* or solvent* or steroid* or stimulant*) adj3 (abus* or use* or using* or misus* or mis-us* or depend* or addict* or illegal* or illicit* or habit* or intoxica* or in-toxica* or disorder* or condition* or illness*)).ti,ab,id. (132642)

24 ((drug* or chemical* or substance*) adj3 (abus* or use* or using* or misus* or mis-us* or depend* or addict* or illegal* or illicit* or habit* or intoxica* or in-toxica* or disorder*)).ti,ab,id. (152314)

25 ((prescription* or prescribed) adj3 (abus* or misus* or mis-us* or depend* or addict*)).ti,ab,id. (2186)

26 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 (258622)

27 comorbidity/ or dual diagnosis/ (35623)

28 (comorbid* or co-morbid* or cooccurr* or co-occurr*).ti,ab,id. (73389)

29 (multimorbid* or multi-morbid*).ti,ab,id. (1223)

30 (coexist* or co-exist*).ti,ab,id. (11539)

31 (dual adj2 diagnos*).ti,ab,id. (3045)

32 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 (91931)

33 indigenous populations/ or alaska natives/ or american indians/ or inuit/ or exp pacific islanders/ (14098)

34 indigenous.ti,ab,id. (12358)

35 aborigin*.ti,ab,id. (4055)

36 (first nation or first nations or first people* or native population* or native people*).ti,ab,id. (1770)

37 torres strait islander*.ti,ab,id. (512)

38 australoid race*.ti,ab,id. (0)

39 maori*.ti,ab,id. (1427)

40 (pacific islander* or south sea islander* or pacific island american*).ti,ab,id. (1862)

41 (native* adj1 (hawaiian* or polynesian*)).ti,ab,id. (722)

42 ((north america* or american or alaska*) adj2 (native* or indian*)).ti,ab,id. (9578)

43 (amerind* or american indian*).ti,ab,id. (5416)

44 eskimo*.ti,ab,id. (364)

45 (inuit* or meti or inupiat* or aleut* or yupik or athabaska*).ti,ab,id. (633)

46 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 (30108)

47 21 or 26 (1356306)

48 32 and 46 and 47 (343)

49 limit 48 to english language (328)

50 limit 49 to (chapter or "column/opinion" or "comment/reply" or dissertation or editorial or letter) (50)

51 49 not 50 (278)

Web of Science

Indexes=SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC Timespan=All years

Rights and permissions