Lifestyle Changes and Perception of Elderly: A Study of the Old Age Homes in Pune City, India

Priyanka v janbandhu 1 , santosh b phad 1 , dhananjay w bansod 2.

1 Research Scholar at International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India

2 Professor, Department of Public Health and Mortality Studies, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India

* Corresponding author Priyanka VJ , Research Scholar at International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India

Received Date: 13 October, 2022

Accepted Date: 10 November, 2022

Published Date: 15 November, 2022

Citation: Janbandhu PV, Phad SB, Bansod DW (2022) Lifestyle changes and perception of elderly: A study of the old age homes in Pune city, India. Int J Geriatr Gerontol 6: 138. DOI: https://doi.org/10.29011/2577-0748.100038

The increase in old age homes and its residents mandates attention to the living condition of elderly at these institutions. The study is based on the information collected from 500 residents of 23 old age homes of Pune city in India. A multistage random sampling used for the selection of samples. A semi-structured interview schedule was adopted to gather the information from the respondents, the interview schedule was approved by the research ethical board of the institute. To strengthen the study qualitative insights are also gathered using case studies and key informant interviews. About half of the respondents were having issues while adjusting at old age home and similar percent has reported that their life has considerably changed after joining the old age home. Over half (52%) of these have experienced negative impact, such as homesickness, feeling of left alone (abandoned) by family members, feeling of staying at a hostel, follow certain schedule, elderly have to adjust in their daily life, and so on. Due to family attachment, many respondents feel lonely. For instance, 56 percent of the respondents perceive that they are being left out by their family members. While, two-thirds of respondents perceive that other elderly who are staying with their family members are having a better life than themselves. Hence, many respondents would like to go back to their families. Despite the fact that more than half (54%) of respondents know that they will spend their remaining days at the old age home. Whereas, 42 percent of the respondents said they are not certain about their future stay and 2 percent believe that soon they will return to their former homes among family members. Although many respondents experienced positive outcome after joining the old age home. Yet, the issues of uncomfortable living, loneliness, or similar unpleasant feeling is present among some of the respondents. These experiences are mostly due to the absence of family members in surrounding.

Keywords: Adjustment; Living condition; Old age home; Family; Elderly

Introduction

Population ageing is considered to be one of the biggest challenges of demographic transition in the twenty-first century [1-3]. Decreasing fertility rates and increasing longevity have resulted in a higher population of elderly people (aged 60 years and above) compared with the younger and adult population than ever before [4-6]. Although developed regions were the first to witness the phenomenon of population ageing, now the developing regions are witnessing a rapid growth of aged population [7, 8]. The share of persons aged 60 years and above in the world is expected to increase by 56 percent between 2015 and 2030. [9]. As per United Nations Population Division estimates increase the share of old age population from 5.7 percent in 2019 to 7.6 percent in 2030 in lower middle income countries [10]. As per 2011 census [11], India’s older population aged 60 years and above is 103 million and it is expected to increase 319 million by 2050 [12].

Increase in the proportion of older population due to shift in the age structure from younger population to older population create various challenges for policy makers and create burden on younger generation and increase demand for social and economic support care for elderly [13]. Before advancement of demographic transition in India, traditional family system was providing care for elderly especially in joint family system. In the past several years, as a result of advanced demographic transition along with socioeconomic development and urbanization, a large chunk of migration has occurred. As skilled professionals have moved to developed countries and from rural to urban areas for better opportunities, leading to reduction in family size and the erosion of traditional families. It led to growth of nuclear families, reduced socioeconomic support and care for elderly, and increased the demand for old-age homes in India [14].

With increased longevity, many of the elderly would require some form of long-term care, the cost of which needs to be borne by their families. This might result in family members withdrawing from school or employment to care for the elderly member. Hence, older people are viewed as a burden [15,16]. Traditionally, within the familial hierarchy elderly people have enjoyed a high status [17-21]. However recently, with the increase in age, several elderly people experience eroding status. In addition to other factors, it contributes to the behaviour of the elderly towards their families and their living arrangement [22,23].

According to BKPAI report [24] marriage of children is and other reasons such as include death of spouse, family conflicts, and migration of children are reasons for elderly to live alone. In addition, the demand for old age homes increased. Some evidences indicate that the increase in old age homes was seen largely in the southern regions of the country, particularly in Kerala and Tamil Nadu, then in the western state of Maharashtra [25-28], due early demographic transition, urbanization and migration led small family norm compared to other states. There has been changes in the social and family structure which affected the culture and norms of the society. The process of modernization and search for better standards of living and job opportunities forced children to move away leaving their parents behind. In This study we assess the lifestyle of elderly and their perception who live in old-age homes in Pune city of India.

Data Source and Methodology

A list of old age homes was obtained from Help Age India, Pune office [29]. This study was conducted in 23 old age homes of Pune city, India. From these old age homes, a total sample of 500 respondents was selected using the lottery method. The researcher used the purposive sampling technique and limited the sample size to 500 elderly respondents from 23 old age homes. The study includes old age homes which have completed at least 2 years of functioning, avoiding all those old age homes which were established or in function not more than 2 years. The study includes only those elderly who were aged 60 years and above, living in old age homes at least for one year. Elderly persons have experience of living in old age home for less than a year are not considered in this study. Those elderly who was unable to respond to the question or who had any psychological issues (diagnosed by a medical practitioner) are not considered for the study.

Participants

The study population was comprised of 500 elderly people, residents of old age homes. Those elderly who are physically mobile and capable of conducting interviews on their own behalf the respondents should have stayed in the old age home for one year so that they can give a better understanding of the facilities provided in the particular old age home where they are staying. A semi-structured interview schedule was developed for the data collection. This interview schedule received approval for data collection from the ethical board of the institute. Data was coded and analysed with STATA (v.14.0) software.

Sample characteristics of elderly population who are living in old-age homes

Table 1 presents the sample characteristics of elderly living in old age-homes in Pune city, Maharashtra. Among respondents, over three-fifths (63%) are women and 37 percent are men. Higher proportion (42%) of respondents are aged 70-79 years, followed by aged 80 years and above (31%) and aged 60-69 years (26%). Percentage of elderly living in the old age homes increases with the up to certain education level. For instance, 13 percent of respondents live in the old age homes have never attended school, whereas 24 percent of respondents have completed 8-10 years of schooling. Share of female respondents is higher with no schooling than the male respondents (16% against 9%). According to marital status, higher proportion (62%) of respondents are widowed/widower compared to 23 percent are never married, 8 percent are currently married and 7 percent are divorced/separated. Share of elderly men who are never married is higher than the never married elderly women (28% against 19%). While, share of elderly women who are widowed is higher than the widowed elderly men (67% against 54%). With regard to social groups, majority (79%) of the respondents does not belong to Scheduled Caste (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST) or Other Backward Caste (OBC). While, 12 percent of respondents are belonging to SC and 7 percent are OBC. According to the type of family, higher larger share (73%) of respondents were living in nuclear family and 26 percent came from joint family. Since, women tend to have lower social status compared to men, they are more likely to depend on the male person of the family either father, husband or son. Hence, women are inclined to have lesser significance in the family. In line with other several factors, women are more likely to join the old age home compared to men.

Table 1: Percentage distribution of women and men aged 60 years and above by selected background characteristics, Pune, Maharashtra, 2017.

Lifestyle of the elderly living in old-age homes

Elderly respondents were asked about whether they have experienced any changes in their personal lifestyle and either positive or negative changes after joining the old-age home. The changes in personal lifestyle of the elderly covers various dimensions such as adjusting with the environment of old-age home, feeling loneliness or left alone, home sickness, health issues as chronic and psychological health problems. While, some respondents have experienced positive changes such as improvement in health condition, received good care at old-age home, good social networking as mingling with other old age home residents, peaceful environment, engagement in various activities which is also a part of entertainment for them.

Table 2 shows the percentage distribution of elderly with significant changes in their personal life style. Over half (52%) of the respondents have experienced negative changes after joining the old age home, while about two-fifths (39%) have experienced positive changes and around one-tenth (9%) have neither experienced any positive nor negative changes in their lifestyle at old age home. Share of elderly women with negative changes in higher than the share of elderly men (56% against 35%). Similarly, among widowed elderly more 54 percent have experienced negative changes and 38 percent have positive changes. Whereas, respondents who are from rural areas are more likely to experience negative changes (57%) compared to respondents from urban areas (44%). Share of elderly with experienced negative changes decreases with increase in number of sons (71% elderly with no son to 33% elderly with 3 or more sons). While, percentage of respondents with experienced negative changes increases with increase in number of daughters (48% elderly with no daughter to 81% elderly with 3 or more daughters).

Mr. Singh (name changed) shared - “I could not afford the cost associated with the required health treatment. In order to receive health treatment and basic care, I have joined the old age home. As a result, my health improved after joining the old age home. At old age home, I have been receiving health care services, the availability of care-taker is an additional advantage. Eventually, my health started recovering at old age home.”

Table 2: Percent of elderly with significant changes in their personal life and positive change in their life after joining the old age home of Pune city.

Perception of elderly

The results presented in (Table 3) shows the percentage distribution of elderly’s perception who live in old-age homes about the others (elderly who lives at home with their family) are better-off compared to them and they feel lonely or left out at oldage home, which varies with different demographic and social characteristics. Perception among elderly staying at old age home that other elderly (who are not staying at old age home) are betteroff than themselves is higher among widowed/widower elderly (69%) compared to never married elderly (65%) (χ2 p-value <0.05). According to type of family, perception of elderly from joint family who live at old age homes that other elderly (who are not staying at old age home) are feel better-off than themselves is significantly higher (74%) than nuclear family elderly (64%) (χ2 p-value<0.05). Similarly, perception of elderly whose residence is abroad and lives at old age homes that other elderly (who are not staying at old age home) are feel better-off than themselves is significantly higher more (71%) than whose earlier residence is same district at local (64%) (χ2 p-value <0.05).

Mr. Ganpat (named changed) never married respondent said “Many elderlies have children and still they are staying in the old age home with me. After watching them suffering like this, I feel that it’s better I am not married and I don’t have a family (children). What is the use of having such children who cannot take care of their parents in their last stage of life? Because, in the end, we (never married and ever married elderlies) are sailing in the same boat.”

Higher percent of widower / widowed elderly who live at old age homes perceive (60%) that they feel lonely or left out than never-married elderly (55%) (χ2 p-value<0.1). According to type of family, the joint family elderly who live at old age homes perceive (60%) that they feel lonely or left out is significantly higher than nuclear family elderly (55%) (χ2 p-value<0.05). Other demographic and social characteristics of elderly perceiving those other elderly persons are better –off who are not living in the oldage homes and feeling loneliness who are living at old age homes are not shown significantly.

Radha (named changed) a widow respondent said “An old age home is unable to provide a warm and welcoming environment like home. My family is always on my mind. Being away from them, and the realization that I will never get a chance to return to them, makes me more uncomfortable at old age home. I feel being isolated by my family members, which makes me feel lonely.”

Table 3: Percentage distribution of the elderly perceiving that the other elderly person is better off and the feeling loneliness at old age homes, Pune city.

Future intention of elderly to length of stay in the old-age homes

(Table 4) presents percentage of elderly and their future intention to length of stay in the old-age homes in Pune city, Maharashtra with different demographic and social characteristics. Percentage of elderly and their future intention to length of stay in the old-age homes is significantly associated with educational level. Length of stay in the old-age homes till death is decreases with increasing educational level. More than half of elderly population with no-schooling (55%) have future intention to length of stay in the old-age homes till death compared to graduation and above educational level (46%). The 44% of elderly have no idea about their future intention to length of stay in the old-age homes with no-schooling compared to graduation and above educational level (47%) (χ2 p-value <0.1) The higher percentage of elderly population whose childhood residence is rural and their future intention to length of stay in the old-age homes till death (58%) compared to others (51%) and lower percentage of elderly population whose childhood residence is rural and they did not have idea about their length of stay in the old-age homes (35%) compared to others (45%) (χ2 p-value<0.1). Percentage of elderly people who had no children with them with length of stay in the old-age homes till death is significantly lower (72%) than others who were having children (44.2%) and percentage of elderly who had no idea about their length of stay in the old-age homes is significantly lower (50%) compared to other who were having children (24%) (χ2 p-value<0.001). Other demographic and social characteristics of elderly such as age, sex, martial-status, religion, social groups (SC, ST, and OBC), family type (nuclear and joint family), having sons and daughters have not shown significant association with their length of stay in the old-age homes in Pune city.

Table 4: Percentage of the elderly with future intentions to stay in the old age home, Pune city.

Discussion and Conclusion

The gender difference is quite prevalent in living in oldage homes as elderly women are more likely to live in the oldage homes than elderly men. Majority of widowed/widower elderly and elderly who came from nuclear family live in the oldhomes due to lack of care and support and death of their partners, especially women have prolonged widowhood due to longer life expectancy than men [38]. Previous evidence shows that increasing urbanization and globalization lead toward nuclear family and migration of children for their job leads to unable to care for their aged parents [30]. For elderly persons, without support of their children, caring themselves is very difficult [30,31].

Most of the elderly have experienced negative change in their life after entry in the old age home as they felt home sickness, health issues as chronic and psychological problems, feeling lonely or left alone, need to adjust with environment of old-age homes and responded that neutral as neither satisfied nor felt bad living at old age homes. Many of previous studies have shown similar evidence that elderly who live olde-age homes suffer from Socio-psychological health problem such chronic health issues as stress, loneliness, depression, anxiety and other health and social issues as loneliness and lack of familial relationship. Especially staff of old-age homes lack caring for elderly, empathy, insufficient understanding of aging issue and skill to take care of elderly in old-age home led to worsen the lifestyle of elderly [3236]. Among these elderly persons, widowed/widower and elderly from rural areas have not satisfied much about their life compared to their counterparts. Widowed/widower elderly are forced to join in the old-age homes due to lack care and socioeconomic support, death their partners, and for being from nuclear family. Majority of the women respondents have spent most of their time with family members and taking care of the household chores. While men have played part in both indoor and outdoor activities. As a result, compared to men, women while staying away from home or family members have shown more disappointment [37].

Important emerging finding of this study is that share of elderly who have experienced negative changes decreases with increase in number of their sons, whereas it increases with increase in their number of daughters. Only few of the elderly have experienced positive changes after joining the old age home such as improvement in their health, received good care at old-age homes, good social networks as mingling with other friends and peaceful environment. Old age brings several issues, and health problems and lack of care and support are the key issues for the elderly. At the old age home, elderly receive health services, care and support which are important needs of the elderly. Hence, several respondents stated that their health condition has improved or they received appropriate health services at the old age homes. While many respondents have unpleasant experiences with their family members and old age home avoids such unpleasant events.

Majority of elderly’s perception who live in old-age homes about the others (elderly who lives at home with their family) are better-off compared to them and they feel lonely or left out at old-age home. Of these, perception of widowed/widower elderly and elderly from joint family about other elderly is that they are better-off and they also feel lonely or left out at old age home is significantly higher than their counterparts as never married and nuclear family. A large part of the respondents covers never married elderly or those who never intended to join the old age home. So, this group considers other elderly who are living with their family members having better life than themselves. Majority of elderly’s intend to stay at old-age home till death and some have no idea that how long they will stay at old age home. Of these, the elderly who have no children have more likely to stay at old-age home till death compared to those who have children.

The study mainly suggests that situation of elderly living in old age homes need attention, as several elderly are experiencing homesickness, unable to cope up at old age home, and feel lonely or left out, irrespective of availability of all required facilities at old age home.

- Chen F, and Liu G.(2009). Population aging in China. In International handbook of population aging (pp. 157-172). Springer, Dordrecht.

- Davies A, and James A.(2016). Geographies of ageing : Social pro cesses and the spatial unevenness of population ageing. Routledge.

- Dyson T. (2001). A partial theory of world development: The neglected role of the demographic transition in the shaping of modern society. In ternational journal of population geography, 7 : 67-90.

- Bongaarts J. (2009). Human population growth and the demographic Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 364: 2985-2990.

- Bloom DE, Canning D, and Fink G.(2010). Implications of popula tion ageing for economic growth. Oxford review of economic poli cy, 26 :583-612.

- Wu L, Huang Z, and Pan Z.(2021). The spatiality and driving forces of population ageing in China. Plos one,16 e0243559.

- Herrmann M.(2012). Population aging and economic development: anxieties and policy responses. Journal of Population Ageing, 5: 23

- Giridhar G, Subaiya L, and Verma S. (2015). Older women in India: Economic, social and health concerns. Increased Awarenes, Access and Quality of Elderly Services. BKPAI (Building Knowledge Base on Ageing in India), Thematic Paper, 2.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019). World Population Ageing 2019: Highlights (ST/ ESA/SER.A/430)

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Popu lation Division. (2015). World Population Ageing 2015 (ST/ESA/ A/390).

- Office of the registrar general of India. Census of India-2011. Ministry of home affairs, Government of India.

- The Hindu.(2021). Number of India’s elderly to triple by 2050.

- Subaiya L, and Bansod DW.(2011). Demographics of population Aging in India: Trends and Differentials,BKPAI Working Paper No. 1. New Delhi: United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

- Bhattacharya P.(2005). Implications of an Aging Population in India: Challenges and Opportunities. Orlando, Fla. Presented at: The Living to 100 and Beyond Symposium Sponsored by the Society of Actuar

- Lancet, T.(2012). Ageing well: A global priority. Lancet 379:1274.

- Rajan IS, and Aliyar S. (2008). Population ageing in India. Institutional Provisions and Care for the Aged, 39-54.

- Chiu S, and Sam Y. (2001). An excess of culture: the myth of shared care in the Chinese community in Britain. Ageing and Society, 21:681

- Chen X, Liu M, and Li D. (2000). Parental warmth, control, and indul gence and their relations to adjustment in Chinese children: a longitu dinal study. Journal of family psychology, 14: 401-419.

- Dowd J J.(1975). Aging as exchange: A preface to theory. J Geron tol, 30: 584.

- World Health Organization. (2015). World report on ageing and health. World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization.(2001). Health and ageing: A discussion paper (No. WHO/NMH/HPS/01.1). World Health Organization.

- Malhotra R, and Kabeer N.(2002). Demographic transition, inter-gen erational contracts and old age security: an emerging challenge for social policy in developing countries.

- Perlman D, and Peplau LA. (1981). Toward a social psychology of Personal relationships, 3:31-56.

- (2012). Report on the Status of Elderly in Select States of In dia, 2011. UNFPA.

- Dyson T, and Moore M. (1983). On kinship structure, female autono my, and demographic behavior in India. Population and development review, 9:35-60.

- Anderson S, and Ray D.(2012). The age distribution of missing women in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 87-95.

- Ratcliffe J.(1978). Social justice and the demographic transition: les sons from India’s Kerala State. International Journal of Health Ser vices, 8:123-144.

- Sudha S, Suchindran C, Mutran EJ, Rajan SI, and Sarma PS. (2006). Marital status, family ties, and self-rated health among elders in South J Cross Cult Gerontol, 21:103-120.

- HelpAge India.

- Johnson S, Madan S, Vo J, and Pottkett, A. (2018). A qualitative analy sis of the emergence of long term care (old age home) sector for se niors care in India: Urgent call for quality and care standards. Ageing International, 43: 356-365.

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Hazan H, Lerman Y, and Shalom V.(2015). Corre lates and predictors of loneliness in older-adults: a review of quantita tive results informed by qualitative insights. International psychogeri atrics, 28 :557-576.

- Shivarudraiah M, Ammapattian T, Antony S, and Thangaraju, (2021). Views of the elderly living in old-age homes on psychoso cial care needs. Journal of Geriatric Mental Health, 8: 113-114.

- Adhikari P. (2017). Geriatric health care in India-Unmet needs and the way forward. Archives of Medicine and Health Sciences, 5:112-114.

- Indu PV, Remadevi S, Philip S, and Mathew T. (2018). A qualita tive study on the mental health needs of elderly in Kerala, South In Journal of Geriatric Mental Health, 5: 143-151.

- Raj D, Swain PK, and Pedgaonkar S.(2014). A study on quality-of-life satisfaction & physical health of elderly people in Varanasi: An urban area of Uttar Pradesh, India. International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health 3:616-620.

- Viveki RG, Halappanavar AB, Joshi AV, Pujar K, & Patil S.(2013). So ciodemographic and health profile of inmates of old age homes in and around Belgaum city, Karnataka. J Indian Med Assoc 111:682-685.

- Rajan SI, and Kumar S.(2003). Living arrangements among Indian el derly: New evidence from national family health survey. Economic and Political Weekly, 38:75-80.

- Janbandhu PV, and Bansod DW. (2022). A Study on social and psychological conditions of elderly living in old age homes of Pune city in Maharashtra. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA : Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. With this license, readers can share, distribute, download, even commercially, as long as the original source is properly cited. Read More .

International Journal of Geriatrics and Gerontology

- About Journal

- Aims and Scope

- Board Members

- Article in Press

- Recent Articles

- Articles Search

- Current Issue

We use cookies for a better experience. Read privacy policy . Manage your consent settings:

Manage Your Consent:

Rethinking architecture of Old age homes

An old age home is a place intended for the elderly where they can live when there is a problem to stay on their own or their children or sometimes destitute. Most of the time senior citizens cannot be alone as they will become dependent and require care and attention for their wellbeing. Old age is an inevitable part of human life and the required care and affection from family may not be given all the time.

In a lot of cases, aged people who require another person to provide care are often sent to old-age homes. An old age home is a multi-facility centre with housing facilities for senior citizens. It is designed to create a home for the elderly but more often than not due to lack of funds or irrelevant design old age homes become more like a healthcare facility with poor infrastructure.

Here are some points you need to consider while designing old age homes:

1. User-Friendly Design | Old Age Homes

For people who have lived independently or with families all their lives, living in an old age home could be challenging. Adapting to rules and new people will take time. To make this process smooth and convenient the atmosphere and ambiance of the place play a major role. The design of the old age home should concentrate on comfort and a user-friendly experience. There are several thumb rules and standards followed while designing a space for senior citizens.

Some common problems with some of the existing old-age home designs are narrow entrances and staircases, which make accessibility with wheelchairs difficult. When stairs are narrow and steep and bathrooms aren’t easily accessible or inconveniently located. Often these possible design oversights do not consider the needs of older people or for people with disabilities.

2. Landscape Design

A place with a landscape often tends to relax and calm one’s mind. A stroll through a garden or a park is one of the most common activities old people do. This also helps them to keep them active and fit. Slow exercises also help increase the well-being of their physical and mental health and doing them along with fellow residents would add fun to the activities.

Most of the time senior citizens feel like they are cooped up in their houses. So, introducing landscape design in the old age home architecture would be a key factor that will be a tremendous change in the environment for the elderly. Being close to nature is proven to have a healing effect on people. Adding natural landscape elements will boost their mood and provide rejuvenating energy.

3. Entertainment and Recreation Space

During old age, people feel like they have a lot of time in their hands. Passing time seems to be a very general issue amongst senior citizens. Boredom leads to lethargy and their presence of mind is seldom lost. Having hobbies is one way of spending time. Making time for lost hobbies like reading books, watching movies or knitting will add to their daily activities.

For entertainment and recreation, games are played where the senior citizens interact and have fun and relax. Having a common activity for every week is a strategy adopted in old age homes for recreation purposes. When this is considered in the design, the main requirement for this cause to be able to function would be a large gathering space accessible easily from their homes. Multifunctional closed or semi- open spaces must be designed to cater to the needs of the people.

A few common old age problems are weakness in limbs, vision, and memory loss. Whatever the issue, physical or mental old people tend to become vulnerable and susceptible to danger. Without supervision, they tend to get lost easily. Due to irresponsible design and infrastructure , they often tend to trip or slip which could be a minor issue for young people but could be more dangerous for old people who take longer to recover.

So, designing spaces with a clear viewing range so that it becomes easy to spot people from across the room or halls. Blind spots and negative spaces must be avoided to reduce confusion. Clear signage must be provided at common spots like gardens and gathering areas in case the senior citizens get lost. Levels and steps are not recommended as a design rule as old people often have weak limbs and it becomes hard to climb up.

5. Health | Old Age Homes

During old age, it becomes uncertain as to when and what kind of health issue may arise. Medical support becomes essential for the elderly. Sudden and severe health issues require immediate care and treatment. If not a hospital at least the old age home must be equipped with basic treatment facilities and equipment.

Easy access and sufficient beds must be provided for care. Equipment and medicine must be available to be transferred to the house of the patient in case of emergencies. Wide lobbies, interconnected blocks, and ease of movement through transition spaces become crucial for the design of healthcare facilities in old age homes.

6. Good lighting

Good lighting is another essential design feature that has to be introduced in old age homes. An ample amount of light must be provided and the places must be well lit to have free movement and good vision. Lights are often provided in nooks and corners like table tops, cabinets , above switches, etc.

The lighting provided must be warm colours and nothing jarring to the eyes. Lighting fixtures in lawns are also important during the evening. All the spaces must be well-lit with no shadow areas and glare must be avoided.

7. Personal space | Old Age Homes

Despite living along with several other senior citizens who are strangers and sharing space with them, they must be provided personal space. It is essential for them to feel that the old age home can be their home where they are free to do what they want.

For this, as a design solution , they can be provided with personal rooms where they can carry out various activities individually and not as a group. A design must aim to reach the people on a subjective level so that they can relate to each space differently and feel as if it’s their own.

Designing old age homes is a great challenge as the mind-set of the users is not fixed and often requires a fresh perspective. An old age home design must achieve to create a place to instill hope and energy and not just as a shelter for old people who are often abandoned by their families.

The natural dynamic of the public design must be tweaked to be adjusted to the requirements of the old age home design. Simplicity and dignity in spaces for the design must be followed in an attempt to create a place for the senior citizens to have a better and healthier lifestyle.

A Plus Topper. (2021). Old Age Home Essay | Essay on Old Age Home for Students and Children in English . [online] Available at: https://www.aplustopper.com/old-age-home-essay/#:~:text=An%20old%20age%20home%20is%20a%20shelter%20that%20is%20home

Dengarden. (n.d.). Elderly Care House Design for Our Old Age – Elderly Care Home . [online] Available at: https://dengarden.com/safety/Home-Design-Ideas-for-Our-Old-Age.

ArchDaily. (2018). How To Design for Senior Citizens . [online] Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/900713/how-to-design-for-senior-citizens.

JK, B. (2010). Guide to Designing Old Age Homes . [online] Architecture Student Chronicles. Available at: http://www.architecture-student.com/design-guide/guide-to-designing-old-age-homes/.

Spandana is an architecture student with a curious mind, who loves to learn new things. An explorer trying to capture the tangible and intangible essence of architecture through research and writing. She believes that there is a new addition to the subject everyday and there is more to it than what meets the eye.

Architects in Winston – Salem – Top 30 Architects in Winston – Salem

10 examples of secret underground cities in the world

Related posts.

Transitioning from Architecture Student to Practicing Architecture

What does art as a technique in architecture mean?

Industrial revolution and the Architectural community

Emotions in the peaceful border design

Sacred Landscape: The Concept of Human-Environment Interaction

What can we infer about a space from its design and architecture?

- Architectural Community

- Architectural Facts

- RTF Architectural Reviews

- Architectural styles

- City and Architecture

- Fun & Architecture

- History of Architecture

- Design Studio Portfolios

- Designing for typologies

- RTF Design Inspiration

- Architecture News

- Career Advice

- Case Studies

- Construction & Materials

- Covid and Architecture

- Interior Design

- Know Your Architects

- Landscape Architecture

- Materials & Construction

- Product Design

- RTF Fresh Perspectives

- Sustainable Architecture

- Top Architects

- Travel and Architecture

- Rethinking The Future Awards 2022

- RTF Awards 2021 | Results

- GADA 2021 | Results

- RTF Awards 2020 | Results

- ACD Awards 2020 | Results

- GADA 2019 | Results

- ACD Awards 2018 | Results

- GADA 2018 | Results

- RTF Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2016 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2015 | Results

- RTF Awards 2014 | Results

- RTF Architectural Visualization Competition 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2020 – Results

- Designer’s Days of Quarantine Contest – Results

- Urban Sketching Competition May 2020 – Results

- RTF Essay Writing Competition April 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2019 – Finalists

- The Ultimate Thesis Guide

- Introduction to Landscape Architecture

- Perfect Guide to Architecting Your Career

- How to Design Architecture Portfolio

- How to Design Streets

- Introduction to Urban Design

- Introduction to Product Design

- Complete Guide to Dissertation Writing

- Introduction to Skyscraper Design

- Educational

- Hospitality

- Institutional

- Office Buildings

- Public Building

- Residential

- Sports & Recreation

- Temporary Structure

- Commercial Interior Design

- Corporate Interior Design

- Healthcare Interior Design

- Hospitality Interior Design

- Residential Interior Design

- Sustainability

- Transportation

- Urban Design

- Host your Course with RTF

- Architectural Writing Training Programme | WFH

- Editorial Internship | In-office

- Graphic Design Internship

- Research Internship | WFH

- Research Internship | New Delhi

- RTF | About RTF

- Submit Your Story

Looking for Job/ Internship?

Rtf will connect you with right design studios.

- Hispanoamérica

- Work at ArchDaily

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

To Design for the Elderly, Don't Look to the Past

- Written by Matthew Usher

- Published on October 30, 2018

When the world undergoes major changes (be it social, economic, technological, or political), the world of architecture needs to adapt alongside. Changes in government policy, for example, can bring about new opportunities for design to thrive, such as the influx of high-quality social housing currently being designed throughout London. Technological advances are easier to notice, but societal changes have just as much impact upon the architecture industry and the buildings we design.

The same is true of changes in demographics, and we are in the midst of a monumental shift. In 2015, 8.5% of the population of the world was aged 65 or over (617 million people). This is predicted to grow to 12% of the population by 2030, and to a staggering 16.7% of the population by 2050 [1]. Historically, this percentage has steadily grown but dramatic advances in medicine are allowing people to live longer, creating aging populations across the globe. This problem is compounded in countries where the birth rate is also incredibly low, as is the case with Japan. We must reevaluate how the elderly are treated within society.

When thinking about the impact of these statistics, the natural assumption within the context of architecture is to think about medical care, hospital design, and accessible cities. However, this overlooks an emerging and serious problem: loneliness and social isolation. Within the UK, 51% of those aged over 75 live alone, and 11% of older people are in contact with friends and family less than once a month [2]. Similar results are present across Europe.

Chronic loneliness within the elderly population is incredibly prevalent and a significant number of studies have been conducted looking at the measurable health impact it has, such as creating a higher risk of disabilities, heart disease, strokes, and dementia. Architects can help tackle loneliness at the source and dramatically help increase the quality of life for a portion of the population who are often isolated. This article explores how good design can help further this cause, how architects have combated this previously, and what the industry leaders are doing now.

In recent years, architects and developers alike have begun to rethink how housing for the elderly should be treated. Multiple panels discussing and studying the needs of the modern older person have been held, including with RIBA and New London Architecture . The new approach features light, modern and very sensitively designed property - the exact opposite of the traditional image. In these schemes, part of the solution is making the housing desirable to residents regardless of perceived or traditional tastes. Living in modern retirement communities provides an opportunity for engagement and interaction while beginning to shed this stigma, and allowing residents to retain their independence.

The Housing our Ageing Population Panel for Innovation (serendipitously acronymed HAPPI) was originally held in 2009, and their reports have since become industry standard. The original 2009 report featured multiple high-quality case studies from throughout Europe, and subsequent issues featured not just the panel's findings but guides for implementation. Advice includes ranges from the architectural (generous space standards, daylight, and adaptability for ‘care readiness’) to the social (engaging positively with the public.) It is the latter part of this range that is most crucial and can be combined with architectural standards.

PRP have become leaders within this field and heavily draw upon this advice from the HAPPI reports. Their Pilgrim Gardens project won multiple awards between 2012-2014 and features several of the design features advised by HAPPI. Double-aspect flats encircle communal garden spaces of hard and soft landscaping, and a shared colonnade acts as a slow circulation space. In-built sliding glass doors to allow the use of the balconies year round.

While focusing more on those requiring care, Dietger Wissounig Architekten’s nursing home in Austria employs a similar effect internally and is incredibly light, liberally using timber and wood within to create a soft and caring environment. Double-stacked corridors are again avoided, allowing the circulation to be inhabited socially as inviting spaces.

The report also highlights the need for multipurpose space where the residents can meet and which could possibly act as a hub for the local community. At The Architect in Utrecht, residences for the elderly requiring care are stitched into the building with the rest of the housing alongside communal spaces and the nursery. Similar projects by Haptic in Norway and Witherford Watson Mann’s almshouse in London also stress the need for social connection. These projects share spaces between neighbors, school children, and the local community through gardens, allotments, shops, and public squares.

Cities have begun to acknowledge the changing needs of an aging population. The ‘Campaign To End Loneliness’ has established a framework of three methods in order to address the multifaceted issue: individual intervention, neighborhood action, and a whole system approach. To help combat the wider scale challenges, the city of Manchester has become the UK’s first ‘age-friendly city’ [4], a World Health Organisation initiative which several forward-thinking cities across the world have subscribed to. The key priorities of the initiative include known benefits such as improvements in transport, housing, and health services, but also highlights the need for civic participation.

Architects can take a leading role in the design of new policy. In Manchester, the ‘Age-Friendly Design Group’ assists with designing local parks to be more age-friendly, listening to the elderly to inform good practice, and publishing of design guidelines. Stephen Hodder, a previous RIBA president, said that such groups open up a “much-needed debate on how we can start shaping the landscape of our built environment for our older age”.

Outside of the city-scale, architectural solutions can also provide for a range of needs. Public ‘day-stay’ centers, such as the Casa del Abuelo in Mexico seem particularly popular (especially in Spain and Portugal.) The design of centers such as these is often strikingly modern and open, blurring the distinction between inside and out. This can partly be attributed to the temperate climates these projects are located in, but the prevalence hints at an emerging approach.

The Guangxi senior center in China , serves an atypically large population and features a range of activities and spaces to accommodate this. The undulating form, clad in wood grain aluminum louvers, includes everything from game courts and gardens to an indoor swimming pool and table tennis rooms. This haven of activity attempts to engage the elderly in physical activity alongside social spaces.

Particular success can be found when positioning these centers as hubs for the local neighborhoods rather than simply as single-purpose structures. This method is similar to The Architect in Utrecht, This can include proximity to other types of housing (such as The Architect) but can also be integrated with libraries or universities. A successful example of this is Sant Antoni - Joan Oliver Library , by Pritzker Prize-winning practice RCR Arquitectes .

The project is nestled within one of Barcelona’s city blocks, wrapping around a central courtyard. The library forms the public face of the building and primary programmatic element, appearing to be suspended between two apartment buildings. The community space then occupies one wall of the courtyard and overlooks the public space. This maintains the perceived ‘safe space’ but places it firmly around a local hub, unifying the project into a coherent block.

A final method is to promote interaction between the young and the elderly. These may seem to be an odd combination of programmes, but significant research is being undertaken into this and the centers which currently subscribe to these ideals and offer them in a safe and secure way.

At the beginning of this article, Japan was noted to be one of the countries most impacted by aging populations going forwards. Increasing life expectancy and societal changes (leading mothers to work outside the home) has meant the numbers both nurseries and senior centers/retirement homes are increasing. There is clearly an opportunity to restructure the way care is delivered for both young and old - something Japan has already been doing for over 40 years. Kotoen, a “yoro shisetsu” (facility for the children and the elderly) in Tokyo, is the oldest age-integrated facility in Japan, having opened in 1976. Here, interaction cuts both ways: seniors can volunteer in the nursery, children visit the communal areas of the care home, and both join together for special events.

When adjoined to care homes, the benefits of this arrangement make sense. Both share basic needs: the provision of meals, physical activity (in the case of the elderly, to keep them active and fit), and communal spaces for socializing. The benefits for the elderly are fairly obvious. The arrangement provides company and activity, bringing life into a space which can often become mundane. But there are notable social and developmental benefits to the children as well: it helps to promote a healthy and positive view of aging and helps counter any preconceptions about the less able.

Mount St. Vincent, a care home in Seattle, runs an ‘Intergenerational Learning Centre’ and endorses similar benefits, stating that it helps to provide a broader perspective of family life for the children who do not have grandparents active in their life.

Surprisingly, there is a dramatic and measurable impact of this upon the physical and mental health of the elderly. St. Monica’s Trust in Bristol housed a study into these benefits, measuring the impact upon the residents over a six week period. At the end of the study, 80% of the residents had improved their mobility and grip strength, and 70% has reduced their score on the scale of depression.

So how can architects begin to promote and further this idea? The impact upon loneliness of aligning these programmes together is dramatic, but the majority of the examples across the world are activity and event-driven. There is the opportunity to develop a new building type to house this program and best suit the needs of the young and old, rather than attempting to retrofit existing spaces. Neither senior citizens nor children want to live in a dull environment, so adapting the design creatively to suit the characteristics of their users is a wonderful opportunity rarely given.

- Sustainability

世界上最受欢迎的建筑网站现已推出你的母语版本!

想浏览archdaily中国吗, you've started following your first account, did you know.

You'll now receive updates based on what you follow! Personalize your stream and start following your favorite authors, offices and users.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Geriatr

Dignity and the provision of care and support in ‘old age homes’ in Tamil Nadu, India: a qualitative study

Vanessa burholt.

1 School of Nursing/School of Population Health, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, University of Auckland, Room 235B, Level 2, Building 505, 85 Park Road, Grafton, The University of Auckland Private Bag, 92019 Auckland, New Zealand

2 Centre for Innovative Ageing, Faculty of Medicine, Health and Life Science, Swansea University, Swansea, Wales UK

E. Zoe Shoemark

R. maruthakutti.

3 Department of Sociology, Manonmanian Sundaranar University, Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu India

Aabha Chaudhary

4 Anugraha, Swabhiman Parisar, Kasturba Nagar, Shahdara, Delhi India

Carol Maddock

Associated data.

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available as restrictions apply to the availability of these data (intention of data analysis included in participant information forms) and sensitivity (i.e. human data) but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Data are located in a controlled access repository at the University of Auckland.

In 2016, Tamil Nadu was the first state in India to develop a set of Minimum Standards for old age homes. The Minimum Standards stipulate that that residents’ dignity and privacy should be respected. However, the concept of dignity is undefined in the Minimum Standards. To date, there has been very little research within old age homes exploring the dignity of residents. This study draws on the concepts of (i) status dignity and (ii) central human functional capabilities, to explore whether old age homes uphold the dignity of residents.

The study was designed to obtain insights into human rights issues and experiences of residents, and the article addresses the research question, “to what extent do old age homes in Tamil Nadu support the central human functional capabilities of life, bodily health, bodily integrity and play, and secure dignity for older residents?”.

A cross-sectional qualitative exploratory study design was utilised. Between January and May 2018 face-to-face interviews were conducted using a semi-structured topic guide with 30 older residents and 11 staff from ten care homes located three southern districts in Tamil Nadu, India. Framework analysis of data was structured around four central human functional capabilities.

There was considerable variation in the extent to which the four central human functional capabilities life, bodily integrity, bodily health and play were met. There was evidence that Articles 3, 13, 25 and 24 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights were contravened in both registered and unregistered facilities. Juxtaposing violations of human rights with good practice demonstrated that old age homes have the potential to protect the dignity of residents.

The Government of India needs to strengthen old age home policies to protect residents. A new legislative framework is required to ensure that all old age homes are accountable to the State . Minimum Standards should include expectations for quality of care and dignity in care that meet the basic needs of residents and provide health care, personal support, and opportunities for leisure, and socializing. Standards should include staff-to-resident ratios and staff training requirements.

In recent decades India has witnessed significant improvements in public health, with increases in life expectancy and longevity alongside declines in infant mortality and fertility rates. As a result, the age structure of India’s population has changed with increases in the proportion and absolute number of older adults (60 + years) in the population. Overall, the proportion of older people has increased from 5.4% in 1950 to 9% in 2020. However there are variations in the age structure across Indian states: in 2020, around 14% of the population in Kerala were 60 + years compared to 7% in Assam [ 1 ]. Although there have been gains in increased life expectancy and healthy life expectancy in India, there have also been increases in the proportion of the older population spending more years living with a disability. This is related to the impact of infectious diseases, malnutrition, and the rapid growth in the prevalence of non-communicable diseases (e.g. diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension), with many older people requiring long-term care and support to manage their daily activities [ 2 , 3 ].

There are a variety of family forms in India, however, the notion of a normative traditional mutigenerational household and extended family prevails [ 4 ]. There is a social expectation that the traditional family will uphold filial piety (respect and obligations towards parents) and familism (prioritizing family needs above all others) [ 5 ] and meet the social, instrumental, economic and emotional needs of older people [ 2 ]. Indeed, this expectation is formally constituted in law. The Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act mandates children, grandchildren and other relatives with sufficient resources to provide support to older people who are unable to maintain themselves. In situations where support is not provided, older people can take relatives to a tribunal to obtain a maintenance order. Non-compliant relatives may be fined or imprisoned. However, this is not a common course of action because there is a lack of awareness of the Act [ 6 ]. Furthermore, older people are reluctant to pursue legal action which could bring shame on the family and criminalise family members or result in a court order requiring the older person to transgress social norms and live with relatives other than sons [ 4 ]. Additionally, not all older people have access to family care: some do not have an extended family and/or have care needs that exceed family care-giving capabilities [ 4 ]. To cater for an increasing number of older people who need extra-familial support in later life, a new ‘old age home’ sector has emerged in India. We use the official terminology ‘old age home’ throughout this article when we refer to the sector in India. We use the expression ‘inmates’ to describe residents of old age homes. We do not condone the use of this term, but use it to illustrate the widespread adoption of the English language word (and meaning) in Indian academic, policy, media and public discourse.

The old age home sector comprises not-for-profit and private homes. The private sector caters predominantly for ‘middle class’ older people, that can afford them [ 7 ] and the charitable (not-for-profit) sector provides for older people without financial assets. The Integrated Programme for Senior Citizens provides basic amenities for older people without access to support (e.g. food, shelter and medical care) and is administered through grants at the state level that are paid directly to providers of registered old age homes and day centres [ 8 ]. Only 310 homes were funded through this scheme in 2018–2019 across all states in India [ 9 ]. There are no accurate records of the number of old age homes in India, nor of the number of residents in facilities, as homes that do not receive funding are not obliged to obtain a license, register, or to be inspected [ 10 ].

In 2016, Tamil Nadu was the first state in India to develop a set of Minimum Standards for old age homes that are delivered by not-for profit organisations [ 11 ]. These focus on physical elements of the facilities (e.g. the size of room, presence of CCTV), access to basic services (e.g. productive activities for residents, housekeeping and assistance with daily activities) and medical services. Although there are no standards relating to the quality of care, the guidance specifically notes, that “each inmates [sic] right to dignity and privacy should be respected” [ 11 ]. This statement is aligned to Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) [ 12 ], that all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. However, the concept of dignity is complex and contestable, and is undefined in the Minimum Standards.

There are two main definitions of dignity which distinguish between inherent dignity and status dignity. The Kantian notion of inherent dignity is conceived as equal moral status and personhood which is grounded in humans’ sentience, rationality and capacity for autonomy [ 13 ]. Some authors suggest that this definition excludes people who lack cognitive capacity or autonomy (e.g. older people with severe dementia) from equal respect and dignity [ 14 , 15 ]. Furthermore, many argue that inherent dignity is built on metaphysics or theology concerning the moral standing of human beings in relation to their ‘gods’ versus the rights of other animals [ 16 ], while others have argued that it is concerned with the worth of the individual in relation to other people [ 17 ]. The controversy concerning the concept of inherent dignity tends to detract from the political function of the UDHR which are intended “to protect individuals against the consequences of certain actions and omissions of their governments” [ 18 ]. Consequently, in this article, the concept of status dignity is used to describe the relationship of residents in an old age homes to the State and the agents of the State (staff in old age homes) [ 19 ].

Valentini [ 19 ] defines status dignity as “a status a human being possesses, comprising stringent normative demands” (p. 865). From this theoretical perspective, the duties to ensure the dignity of citizens (and that human-rights are fulfilled) primarily falls on the State and its agents. However, in order to explore whether the state is fulfilling their primary duty requires a definition of ‘normative demands’ essential for dignity [ 20 ]. In this respect, Nussbaum [ 21 ] has posited that governing bodies should secure for all citizens a threshold of ten central human functional capabilities (CHFC). CHFC are “opportunities that people have when, and only when, policy choices put them in a position to function effectively in a wide range of areas that are fundamental to a fully human life” [ 22 ].

The capability approach refers to the opportunities and freedom to undertake the activities necessary for survival, to avoid or escape poverty or serious deprivation and achieve a life that is “not so impoverished that it is not worthy of the dignity of a human being” [ 23 ]. For example, bodily health (a CHFC) is partly underpinned by nourishment. Nourishment in turn requires resources to prepare meals (i.e. access to food products that are culturally or religiously acceptable and an energy source to cook upon) and the personal ability or external support to undertake the functions of cooking and eating. The capability approach resonates with other authors’ descriptions of the conditions necessary to support dignity in organizational and clinical settings [ 20 , 24 , 25 ]. All ten CHFC are relevant to supporting the dignity of residents in old age homes, however, this article focuses on four: life, bodily health, bodily integrity and play which correspond to Articles 3, 13, 25 and 24 of the UDHR (Table (Table1 1 ).

Correspondence between four central human functional capabilities [ 21 ] and articles of the United Declaration of Human Rights [ 12 ]

In India, there has been very little research within old age homes. The research that has been published has tended to focus on the private sector [ 7 ]. The available evidence suggests that a majority of homes require residents to be ambulatory, continent, and cognitively able at the time of admission [ 7 ]. Whether the CHFC are supported for residents that become unable to self-care because of physical or cognitive impairment is unknown. Presently, it is unclear as to the extent to which staff in old age homes, as agents of the State, uphold the dignity of residents. To explore human rights issues and experiences of old age home residents in India, this article addresses the following research question:

To what extent do old age homes in Tamil Nadu support the central human functional capabilities of life, bodily health, bodily integrity and play, and secure dignity for older residents?

Sample location

Tamil Nadu state is situated in the south India and covers 130,060km 2 . Tamil Nadu had a population of 72 million in 2011 of which 88% were Hindu. One-tenth ( n ≈ 7.2 million) of the population were age ≥ 60 years.

Sampling procedures

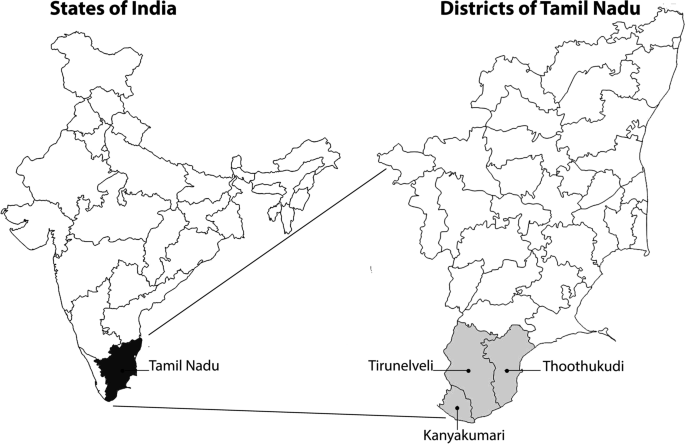

Old age homes were purposively selected from three southern districts in Tamil Nadu: Thoothukudi, Tirunelveli, and Kanyakumari (Fig. 1 ). Forty-three old age homes were located through a mapping exercise: 13 in Thoothukudi, 11 in Tirunelveli and 18 in Kanyakumari. The ratio of fee-paying to free old age homes in each district, and the size of the homes were used to inform our sampling strategy. Participants were randomly selected from lists of residents in 10 facilities, to obtain (as far as possible) a gender-balanced sample of 10 people in each district (Table (Table2 2 ).

Map of the states of India showing the location of Tamil Nadu, and map of Tamil Nadu showing location of selected states

Characteristics of old age homes in sample

a Purports to be for destitute older people: of those interviewed, all participants either paid themselves or had relatives that paid ‘donations’

b Also role as care attendant

c Also role as nurse

d Also role as cleaner

Data collection

Face to face guided interviews (17–70 min; M = 34 min) were conducted in Tamil with 30 residents (15 male, 15 female, age range 60–83 years) and 11 staff in old age homes, between January and May 2018 by three experienced female interviewers who were PhD scholars at Manonmanian Sundaranar University. To standardise approaches to interviewing, training was provided by the first and third author.

Interviewers explained the purpose of the study and established relationships with the residents and staff before the study commenced. All participants were interviewed in a private place where they could not be overheard or interrupted.

Semi-structured interview guides were used for residents and staff. Open-ended questions explored how residents came to be living in the old age home [described elsewhere, 4] and experiences of the old age facility. Examples of questions included: “Tell me about your typical day”, “What is the best thing about living here?” “What is the worst thing about living here?” “If you need help here, does anybody help you?” “What do you do with your time?” Staff were asked questions such as, “What services are provided to residents?” “How are residents’ needs assessed, if at all?” “What happens if a resident becomes sick?”.

The first three interviews were used to pilot the interview guide, and to check the quality of interviewing. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and translated by a professional translator into English and anonymised. Pseudonyms are used throughout the article.

Framework analysis was used to analyse the data [ 26 ]. Five distinct but inter-connected phases (familiarisation; identifying a thematic framework; indexing; charting; mapping and interpretation) provided a rigorous methodological structure. Familiarisation, conceptual and cultural understanding of the interviews were clarified during team meetings (first and third author with interviewers) in Tamil Nadu. The second author created a list of a priori codes from the interview questions (e.g. support for each activity of daily living, discriminatory practices, food and nutrition, religious practices, leisure and recreation, worst and best things in the home). She applied these codes to transcripts (in NVivo 1.5.1), and while reading through the transcripts simultaneously created a new series of a posteriori codes, in an inductive thematic analysis. The first author read through the transcripts and coding to check validity. She then systematically applied a second coding index based on the capability approach: some thematic nodes became wholly subsumed in the ‘family’ nodes (e.g. ADLs were subsumed under ‘bodily health’) whereas others were relevant to more than one CHFC (e.g. worst thing in home). The first author charted the data into a framework which provided a decontextualized descriptive account of the data in relation to each CHFC.

The first author undertook the preliminary interpretation of data in three steps. First, taking an outcome-oriented approach, examples where each CHFC had/had not been secured were juxtaposed, providing an insight into the breadth of experiences of old age home residents. Second, residents’ and staff interviews were grouped by home and particular attention was paid to exceptions, contradictions and disconfirming excerpts. Third, experiences were contrasted between types of facilities (registered versus unregistered). All other authors (in India and the UK) were used as a sounding board, to check the persuasiveness of the analysis and to provide different ways of interpreting the research phenomenon [ 27 ].

‘Life’ refers to being able to live a normal life-span and not dying prematurely or before one's life is reduced as not worth living. This CHFC is closely related to bodily health. Participants referred to the ceiling of care available to them, if a resident was ill, or unable to carry out activities of daily living. In some cases, this was also referred to as the ‘worst thing’ about the old age home.

The first quote highlights the practical and ethical difficulties of deciding what ‘a life not worth living’ comprises. In this example, the resident perceived that the facility would judge that a sick older person’s life had no quality and would not be worth saving. Maalia explained what would happen if she became ill in the old age home in which she lived:

They will put me in the back room [sick room]. You may get a bath or you may not. You will have to lie there and die… If I become sick, the Sister will pour coffee and porridge. They will do that only when you become too sick. When you are going to die, they will pour water and bid farewell. That’s all. (Female, 65 years, widowed, H11 unregistered)

In other facilities, residents believed that if their health deteriorated to a point at which they were unable to take care of themselves they would be cared for by their children. For example, Rishi who had four daughters and lived with his wife said:

If we become too old and unable to do things, they [daughters] will only take us back. Now we are able to do things. So we are here. If we fall sick, these people will inform them and they will come and take us with them. (Male, 83 years, married, H14 registered)

Similarly, Hitendra said:

What if I become sick in the last stage of my life? Luckily I joined here when I was healthy. The facilities here are good. So, I want to be here for some time... I told my son that I would go to his house in [city > 200 miles away] if my health deteriorated. (Male, 83, separated, H10 unregistered)

The expectations for support at the end of life maybe unrealistic, as the residents were living in the facilities because their families were unwilling or unable to provide support. If support did not materialise, then this would not be problematic for Rishi, as the old age home he lived in provided life-long support. Diya, another resident in H14 noted:

If we are not well, the doctor will immediately attend. All medicines will be provided immediately. These three people [the doctor, the manager and the assistant manager] take such good care. One should have done punniyam [meritorious deeds in previous lives or in the past] to come here. (Female, 77, widowed, H14 registered)

However, there was no health care, personal support, or palliative care in the facility where Hitendra resided, and the manager noted:

The residents should take care of themselves. If they cannot take care of themselves, we cannot help. We do not have any attendant here. (Manager, H10 unregistered)

The Tamil Nadu Minimum Standards note that “each Old Age Home should ensure that the inmates [sic] should continue to receive care till the end of his/her life or up to natural death” [ 11 ]. Despite, mandatory care obligations, the Standards were only enforceable in registered facilities. Consequently, with one exception where a nun provided some personal support (see section on bodily health below), there were no care attendants to support residents in the unregistered facilities (Table (Table2 2 ).

Bodily health

This theme incorporated examples of supporting residents’ bodily health through medical and personal care (i.e. support for activities of daily living), adequate nourishment and shelter. Some difference between facilities in the availability of staff to provide health and personal care were mentioned above concerning CHFC life.

Residents in unregistered facilities were more likely to have to retain the ability to self-care or to provide support to each other than those in registered facilities. Dev and other residents in the same facility noted:

Here we don’t have anybody to get help. That is the rule here. One should eat oneself, one should wash oneself, one should sleep oneself. They are strict about it. Suppose you cannot walk by yourself, they, your co-residents may help you. That’s what happened to me for some 10 days. My roommates helped me. They would bring food for me. (Male, 72 years, never married, H15 unregistered)

However, this was not common to all unregistered facilities. Although there were no ‘paid’ attendants, in one facility a nun helped residents with personal care tasks, as Deepak said:

This Sister [name] takes me all by herself from the bed to the wheelchair. Takes me to the toilet for evacuation and cleans, gives me a bath, towels and brings me back here, dresses me and makes me lie down. She helps me eat food. She does everything in a good manner. (Male, 68 years, widowed, H16 unregistered)

In the only unregistered facility with a care attendant (the manager) the ratio of care attendants to residents was 1:20, whereas in the registered facilities, it was around one person for every four or five residents. The difference in levels of staff between registered and unregistered facilities was particularly stark for the largest facilities: whereas the registered facility had 19 staff for 65 residents, the largest unregistered facility had only three staff (one manager and two cooks) for 110 residents. In this facility the manager explained that “ we give work to those who are able among the residents” . Many of the manual jobs described by the manager, such as sweeping and cleaning rubbish are associated with lowest castes in India and are considered degrading [ 28 ].

We assign the older among them such work as making brooms with coconut leaflets. If they are young, we assign cleaning and gardening work. But we rotate the tasks. For the mentally retarded elders [sic], I ask them to take the firewood... I will give the vegetables to them and ask them to handover to the cook… They do such things as sweeping and removing cobwebs. They clear the dustbins. We ask them to help their fellow residents who are bedridden. (Manager, H11 unregistered)

In registered facilities, residents were more likely to receive support with personal care and medical or health care, even if this involved making clinical appointments outside the facility. In one facility some difficulties with personal support were noted: Pratik and Padma highlighted issues associated with assisting men and women to dress appropriately and with dignity.

There is a lady nurse. She takes me to the bathroom and gives me a bath and helps me dress. But she is a woman, and she does not know how to tie the veshti. Other men around will come to help at such times. (Male, 60 years, separated, H18 registered) That nurse gave me this petticoat without any saree. She is a nurse. Doesn’t she know that this petticoat is only suitable for a saree? (Female, age unknown widowed, H18 registered)

To support the nourishment of residents, most facilities had a set weekly menu. Residents in most facilities were satisfied with both the quantity and quality of the food that they received and Hitendra’s comment was typical of many “ The food is good. Even at home we will not get such food”. There were only two facilities in which residents indicated some dissatisfaction with the availability of food and drinks. In the first facility, this was mainly in relation to ‘snacks’ that had to be purchased. This was problematic for residents such as Varsha and Udit who had insufficient income.

Here they make coffee occasionally. It is black coffee. We don’t get it daily. They give biscuits rarely. If we give money, we can ge t. (Female, 75 years, widowed, H11 unregistered) I would like to eat some snacks like biscuits and omappodi. But I cannot get these. (Male, 80 years, separated, H11 unregistered)

In the second facility (H18, registered), the quality and range of food provided did not suit Padma’s food preferences or intolerances, she said:

Sour dosai. I don’t like it. If I eat this I will get leg pain. I don’t eat curd. I was advised not to eat sour things. They give just four idlies and they too will be sour. I will eat wheat dosai, but they will not give me any. (Female, age unknown, widowed, H18 registered)

In terms of providing shelter the cleanliness of the unregistered facilities varied, and this is contrasted in the following quotes from Maalia and Hitendra. Whereas Maalia had to clean faeces from the bathroom before she bathed, Hitendra was very satisfied with the cleanliness of the old age home in which he lived.

It [the bathroom] is befouled with urine and faeces. I clean it up with water and then, if I can tolerate it, I take a bath or wash clothes. I keep the clothes on my thigh and apply soap. What else can I do? Where can I go? (Female, 75 years, widowed, H11 unregistered) The rooms and the beds are neat. They change the bed sheet every month. They sweep daily. Bathroom and toilet are clean. (Male, 83 years, separated, H10 unregistered)

Bodily health is underpinned by opportunities to have good health (i.e. access to health and personal care), to be adequately nourished, and have adequate shelter. The Tamil Nadu Minimum Standards for old age homes specify the services that should be provided to residents. These include three meals (breakfast, lunch and dinner), two refreshment breaks (tea, coffee and snacks), and weekly visits by a medical officer. Furthermore, in-house staff should include a nurse, counsellor, cook and helpers (care attendants). While these services were more likely in registered homes there was still variability in terms of the quality of the services provided, an issue that is not addressed in the Minimum Standards. Overall, unregistered old age homes were less likely to provide opportunities for bodily health for residents: only one unregistered old age home in the study attempted to cater for the personal care needs of residents.

Bodily integrity

Bodily integrity refers to moving freely from place to place, secure against assault. The themes ‘abuse’ and ‘leaving the premises’ (i.e. freedom to move within and beyond the old age facility to the community) were incorporated in this family node.

Residents in H14 (registered) and H10 (unregistered) were permitted to leave the premises if they gave written notice and were accompanied by an attendant. Special occasions such as weddings and birthdays often warranted longer trips away from the facilities, and Joti noted that residents could be accompanied by their relatives. Avinesh also mentioned that residents were permitted to go to local places if they were accompanied by a member of staff: