Causes and impacts relating to forced and voluntary migration Case study: Mexico and the USA

There are two types of migration, forced and voluntary. People migrate for many different reasons. Migration has positive and negative impacts on society.

Part of Geography Population

Case study: Mexico and the USA

According to the International Boundary and Water Commission for the United States and Mexico, the border between the USA and Mexico is 1,954 miles long. Illegal migration is a huge problem. U.S. Border Patrol guards the border and trys to prevent illegal immigrants from entering the country. Illegal migration costs the USA millions of dollars for border patrols and prisons.

There are more than 11 million unauthorised immigrants living in the USA.

Many Americans believe that Mexican immigrants are a drain on the economy. They believe that migrant workers keep wages low which affects Americans. However other people believe that Mexican migrants benefit the economy by working for low wages.

Mexican culture has also enriched the USA border states with food, language and music.

Impact on Mexico

The Mexican countryside has a shortage of economically active people. Many men emigrate leaving a majority of women who have trouble finding life partners. Young people tend to migrate, leaving the old and the very young.

Legal and illegal immigrants together send some $6 billion a year back to Mexico. Certain villages such as Santa Ines have lost two thirds of their inhabitants.

There is a large wage gap between the USA and Mexico. Wages remain significantly higher in the USA for a large portion of the population. This attracts many Mexicans to the USA.

Many people find living in rural Mexico a struggle because they have to survive with very little money. Farmland is often overworked and farms are small.

It is estimated that 10,000 people try to smuggle themselves over the border every week. One in three get caught and those that do are likely to continue trying to cross the border at least twice a year.

More guides on this topic

- Methods and problems of data collection

- Consequences of population structure

Related links

- BBC Weather

- BBC News: Science, Environment

- BBC Two: Landward

- SQA: Higher Geography

- Planet Diary

- Scotland's Environment

- Greenhouse Gas Online

- Geograph British Isles

Please enable JavaScript.

Coggle requires JavaScript to display documents.

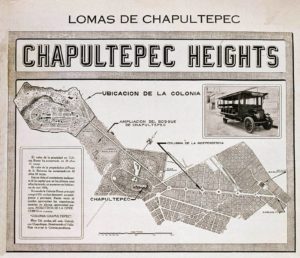

Geography - Mexico City Case Study (Effects of rapid urbanisation in…

- Mexico city has a population of over 21 million and is the largest metropolitan area in the western hemisphere.

- It is one of the most important financial centres in the Americas. In 2011, the city had a gross domestic product of US$ 411 billion. This makes it one of the richest urban areas in the world. GDP is the total value of goods and services produced in a year in a particular location.

- There is huge inequality across the city, in terms of income, lifestyle, housing, employment and access to services. Spatial inequality is very powerful with some areas of the city being completely different to others.

- Mexico city has a culture which is a mix of Spanish and indigenous traditions. This extends to food, music, religion and architecture. The city is the most important cultural centre in Mexico. The city is home to a national opera and theatre as well as TV and radio stations which operate across the country and neighbouring countries.

- The main cause of rising natural increase is a fall in the death rate.

- Mexico City to migrants from countryside was the growth in jobs opportunities in factories and offices as economic investment was channelled into the city.

- The movement of people to urban areas from rural areas due to better jobs, healthcare and education.

- (Puebla) - it is a poor region to the east of Mexico City. There are few jobs outside of farming. Framing can e unreliable as crops may fail leaving people with limited income/food.

- (Puebla) - Only 40% of people have clean water.

- (Puebla) - Literacy rate is only 65%

- (Puebla) - Two thirds of people lack proper housing.

- Jobs - New factories, means more people are needed to work.

- 82% of people have access to clean water .

- 45% of all the country's industry.

- The cultural life of the city and its domination services in the country are other attractive.

- Push Factor: Negative aspects of a particular place that forces people from it.

- Pull Factor: Positive aspects of a place that attracts people towards it,

- There is a large CBD which is home to banks, insurance and financial services. This is in addition to government offices and headquarters of large companies. These companies are both Mexican and international (TNCs).

- Next to the CBD is the inner city, here there is a mixture of housing. There are some ageing apartment blocks, alongside some high quality modern apartment buildings.

- Extending further out the city, the pattern becomes more complex. There is a mixture of industrial areas, luxury housing areas and areas of high density housing. Some of this is in the form of squatter settlements.

- This pattern has been created by population growth, housing segregation, income level, industrialisation and developments in transport.

- People who have recently arrived in Mexico City from the rural areas are usually poor and have to live in slums or shanty towns.

- The wealthier people are also those with political power

- They are able to get homes in the better parts of the city.

- The poorest people live in shanty towns and rubbish dumps.

- The average disposable household income per person in 2013 was US $13,085, which is lower then the Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average of US $25,908.

- The top 20% of people in Mexico City earn 13 times as much as the bottom 20%.

- This explains the gap between the poorer and richer and the areas in which they live in.

- Poorer people also have to work longer hours in Mexico City.

- 29% of employees work very long hours compared with an average of 13% in other developing and emerging countries.

- Mexico City has the best living standards in Mexico.

- 60% of people live in informal settlements

- 4 generations live in the same building, overcrowding

- Long commutes to work

- Houses built in natural areas of beauty due to high demand

- Uses more water than any other city in the world

- Lots of sewage and water pollution due to rising population

- Current infrastructure cannot deal with the waste

- Dry lake bed amplifies earthquakes

- Cable car reduces air pollution

- Difficult to police

- Air pollution due to lots of traffic

- Small scale so people feel involved and are likely to go on supporting them after the initial interest has faded.

- Do not take long to get going.

- Do not need a lot of money.

- Do not need a lot of people initially - can set up as an example to others.

- Do not have a lot of money, so may not be able to scale up.

- Cannot easily deal with big problems like air pollution.

- May not have political support

- There is political power to make sure it happens

- The city government can make sure there is enough money for the project.

- It is possible to deal with large-scale issues such as flooding and air pollution, which smaller community-led strategies.

- It creates work for people in the city.

- They may suffer from budget cuts or corruption and so never happen.

- They do not involve local people who may feel alienated.

- They can take a long time to put into action.

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, peri-urbanization and land use fragmentation in mexico city. informality, environmental deterioration, and ineffective urban policy.

- 1 Department of Social Geography, Institute of Geography, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico

- 2 Graduate Studies in Geography, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, National Autonomous University of Mexico, México City, Mexico

There is a great deal of concern over the scattered, fragmented expansion of cities, particularly in developing countries. This expansion accelerates the peri-urbanization processes expressed in a range of land uses, often with a concentration of the poor in peripheries with an acute shortage of services coupled with profound land-use changes, with far-reaching environmental impacts. The urban periphery is a transition zone, where the urban gradually merges into the rural landscape. It has become heterogeneous from a social, environmental, commercial, and service point of view, reproducing a model of metropolitan inequity with marked socioeconomic inequalities between the center and the periphery. The way these territories are managed is quite far from the road to sustainability. This article seeks to provide an updated analysis of the dynamics of urban expansion and land-use changes on the southern periphery of Mexico City (CDMX) in the Conservation Area (CA), to determine the extent to which a socially segregated, environmentally unsustainable model of urban fragmentation has been reinforced. It also discusses the regulatory, normative framework established in the CA, finding that it has been deficient and implemented in piecemeal fashion. It concludes that local government has failed to provide solutions to reconcile the protection of ecological conservation areas with the needs of the poor in a peri-urban area, thereby reproducing social inequalities in the city. In addition, CDMX land use policy has been ineffective in controlling the expansion of informal human settlements in peri-urban areas with high ecological value.

Introduction

The world's urban population has grown rapidly since the middle of the last century, and as a result 55% of the world population already lived in cities by 2018. This urbanization trend is expected to add 2.5 billion people to the world population by 2050, with 90% of this growth occurring in Asia and Africa. At the level of urban cores, medium-sized cities have shown a marked increase: one in five urban inhabitants lives in cities with one to five million inhabitants. The population of this type of cities nearly doubled from 1990 to 2018 and is expected to increase by a further 28% from 2018 to 2030, from 926 million to 1.2 billion ( United Nations, 2019 : p. 10, 15). One of the most far-reaching consequences of the urbanization of medium-sized and large cities in developing countries is the rapid expansion of their metropolitan peripheries, with a highly dispersed pattern, incorporating large swathes of territory into urban limits, which has exacerbated the problems of occupation and fragmentation of land use in both social and environmental terms.

The core problem is that cities in countries that are becoming urbanized most quickly must create an enormous supply of land to accommodate a growing population, particularly on the urban peripheries. Since the population of large cities in these countries will continue to increase, due to natural growth or the influx of immigrants, the dispersed urban expansion model is likely to continue for many years. As Angel (2014 : p. 24, 53) points out, with rapid urbanization, expansion is inevitable, and measures must be taken to prepare spaces for future expansion. This may prove more helpful than measures to contain urban expansion, which have not only failed, but also produced negative effects such as driving up land and housing prices. In fact, it is argued that the rate of expansion of urban sprawl is greater than the population increase in developing countries 1 , reflecting a clear trend toward the reduction of urban density due to the creation of more dispersed cities ( Angel, 2014 : p. 224). Several studies in the past two decades have discussed the characteristics of peripheral or peri-urban areas in developing countries, highlighting their most characteristic features. These features reflect the special nature of these areas, highlighting the most relevant land occupation processes that take place within their limits.

Peri-Urbanization, Socio-Environmental Change, and Sustainability

Land use transformations in urban peripheries are associated with what for several years has been known as the peri-urbanization process in the world's great metropolises. These changes take place in a strip with urban-rural characteristics on the edges of the urban area, the size of which varies by city and may range from 30 to 50 km. Over time, this peri-urban area, also called the rural-urban fringe, peri-urban interface ( Simon, 2008 : p. 171), or urban sprawl , loses its rural features, gradually incorporating new urban uses such as housing, infrastructure, access to services and urban productive activities, as well as experiencing environmental deterioration (see McGregor et al., 2006 ; Ewing, 2008 ; Da Gama Torres, 2011 ; Ravetz et al., 2013 ; Geneletti et al., 2017 ; Coq-Huelva and Asían Chavez, 2019 ). Recently there has been an extensive literature on informal settlements emphasizing both the spatial spread and demographic characteristics of urban fringe settlements particularly in Africa, China and South East Asia (see Abramson, 2016 , for China; Tan et al., 2021 , for Beijing; Ukoje, 2016 , for Nigeria; Brandful Cobbinah and Nsomah Aboagye, 2017 , for Ghana; Phadke, 2014 , for Mumbai; and Hudalah and Firman, 2012 , for Jakarta).

This is a transition strip, where the urban front advances and rurality disappears, in other words, a slope with intense exchanges between rural and urban areas, which is undergoing the modification of the socioeconomic structures of rural areas. There is obviously a process of urban decentralization within metropolises, which contributes to peri-urban areas experiencing swifter, extremely diffuse urbanization (see Inostroza et al., 2013 ; Liu et al., 2016 ). This, in turn, is the result of a territorially more decentralized economic model, where the productive urban logic spills over into a broader metropolitan or regional sphere, where, through agglomeration economies, firms develop links at these levels ( Storper, 1997 : p. 299–300), all of which encourages peri-urbanization.

The innermost area of the peri-urban interface is adjacent to the built area, while the outermost area extends over a broad area whose limits are difficult to define. This is one of its characteristics: its elasticity as a territorial unit. It might be useful to adopt the approach of an urban-rural continuum due to the difficulty of defining its limits ( McGregor et al., 2006 : p. 10–11; Simon, 2008 : p. 171) and the transformation dynamics between the two opposite poles. This enables one to analyze the gradual dynamics of change affecting the various locations of the peri-urban strip. The current most outstanding features of the peri-urban areas are described below.

First, one of the key features of peri-urbanization is land use fragmentation , non-contiguous urban expansion toward the open, rural spaces surrounding the city ( Angel, 2014 : p. 182). This discontinuous, fragmented development is inherent to the dispersed land occupation model. Metropolitan peripheries comprise patches of urban fabric interspersed with open spaces including green areas or unbuilt wasteland. If there are cities with increasingly low densities, fragmented, disconnected peripheral environments will continued to be created ( Angel, 2014 : p. 263). Fragmentation is a phenomenon inherent to the periphery of the city and reflects the dispersion of urban expansion. As empty spaces are filled in, more empty spaces emerge further away. In fact, these fragmented spaces are spaces in transition from a rural to an urban reality.

Second, nowadays the main characteristic of peri-urban areas is their growing social heterogeneity in terms of the presence of social groups. The type of residential area corresponds to the distinct types of peripheries. First, there is a rich residential periphery associated with the middle and upper classes, with decent quality infrastructure and efficient connectivity to central areas. Second, there is usually a poor periphery with irregular settlements and an acute shortage of services; and third, a traditional periphery with rural towns and agricultural activities, and in several cases the presence of indigenous peoples ( Aguilar and Ward, 2003 ; Aguilar, 2008 ). These social contrasts result in new forms of polarization and socio-residential segregation, where the poorest groups suffer severe deprivation due to their precarious social conditions, a common feature of cities in developing countries.

Third, a modern periphery has been formed, associated with new urban developments, linked to global big money. Peri-urban territories have become more competitive due to the presence of more highly qualified human capital, greater national and global connectivity, and productive diversification. In this way, for example, new urban sub-centers have been established within their territories, with shopping precincts, corporate developments, and gated communities; industrial zones and technology parks; large-scale infrastructure such as airports and conference centers; together with recreational facilities such as theme parks and natural areas. In other words, these spaces have become hubs for the flow of people, goods, and information; advanced service providers; and major consumer centers ( Coq-Huelva and Asían Chavez, 2019 : p. 3).

Fourth, there is a green periphery with ecological protection zones and high environmental value that provides the city with environmental services. It is important to mention the negative environmental impact caused by urban expansion through solid waste disposal, the exploitation of construction materials, the invasion of channels and bodies of water, the over-exploitation of underground water, and the destruction of native vegetation ( Douglas, 2006 ). This green periphery is often indistinguishable from land for agricultural use, which is gradually being encroached on by the city.

Fifth, in developing countries, it is extremely common to find an informal poor periphery resulting from the state's inability to provide inexpensive land and housing for social groups in the lowest income level. This situation has forced the public administration of each city to “accommodate” the massive demand on the part of the poor population while tolerating the formation of irregular settlements, especially on the urban peripheries, thereby allowing land occupations, which, in turn, encourage and increase the informal housing stock ( Smolka and Larangeira, 2008 : p. 101). Informal occupations are widely promoted by informal developers since they are an extremely lucrative business. The dynamic of peripheral expansion offers cheaper land and labor, larger spaces with environmental amenities, and increasingly better accessibility, which, in turn, drives settlement, in irregular conditions, with housing for poor groups and migrants with an acute shortage of services. A model of absolute tolerance is unacceptable because regularizing informal settlements, which are the visible effects, without addressing the causes of growth, yields extremely poor results, and perpetuates social inequality.

This diversity in the occupation of peripheral land is part of the challenges of its territorial planning because it is an extremely dynamic, diverse territory that is rapidly expanding. Good governance is required to deal with all the economic, social, territorial and, of course, environmental dimensions of its development, and land occupation patterns that must be addressed because of their implications for urban planning and the sustainability of cities. This occupation model implicitly or explicitly promotes a more dispersed city model rather than denser, more compact, and sustainable cities.

Socio-Environmental Processes and Sustainability

The negative environmental effects of peri-urbanization have become critical because of their implications for urban sustainability. The environmental factor makes the territorial planning of these spaces more complex due to their mixed land uses (urban and rural); the need to provide infrastructure and facilities for poor settlements (such as water networks, drainage, housing, and street paving), and actions to preserve the environment. These tasks are extremely complicated and depend on the institutional construction and financial capacity of each city. Environmental preservation has been established as a mandatory objective of urban policy, due to the enormous pressure on the environment exerted by urbanization, not only because of the intense population concentration, but also because of manufacturing waste activities, the low-quality infrastructure of housing for the poor, and the consumption levels of the middle and upper classes.

Sustainable urbanization has emerged as a new paradigm that not only encompasses ecological protection, but also other components such as economic growth, the satisfaction of social needs and the principle of social equity ( McGranahan and Satterthwaite, 2003 ). The social dimension is crucial because an unequal society cannot be regarded as sustainable in the long term ( Rogers, 2008 : p. 57–58). It is extremely difficult to prioritize environmental impacts in an urban context where the problems of unemployment, poverty and poor-quality housing and infrastructure, all of which are related to environmental deterioration, are not addressed ( Haughton and Hunter, 1994 : p. 26; Gilbert, 2003 : p. 79–85).

Unfortunately, little or no attention is paid to the socio-environmental processes behind manifestations such as urban occupation patterns, water provision, the deterioration of natural reserves, solid waste disposal and public transport. Society is not a homogeneous whole. Social inequalities and power relations between social groups must be recognized to be able to advance toward a more equitable, sustainable city ( Rogers, 2008 : p. 66–67).

Urbanization occurs because of a series of socio-territorial processes of change, in which environmental modifications, which are usually profoundly unjust, are analyzed. There are political processes that produce and reproduce urban conditions of a socio-environmental nature with significant environmental deterioration. In this case, it is important to ask, who produces what kind of socio-environmental conditions? And for whom? ( Heynen et al., 2006 : p. 2–4). How is sustainability built in terms of policies and institutional forms in these locations? Actors and institutions have the capacity to formulate and implement certain policies and stop pursuing others ( Gibbs and Krueger, 2007 : p. 102–103).

Urbanization is a central part of the production of new environments, in which society and nature are combined in historical-geographical production processes. And as Heynen et al. (2006 : p. 10) state, there is not usually an unsustainable city, but a series of urban and environmental processes that negatively affect certain social groups, while benefitting others. In this respect, one should always consider the issue of who wins and who loses and raise fundamental questions about the multiple power relations through which deeply unjust socio-environmental conditions are produced and maintained.

It is essential to prioritize the social value of sustainable urbanization based on commitments to change focusing on social inclusion and poverty reduction. This approach is a way to ensure the “right to the city”, which means that all the inhabitants of the city have the same rights and opportunities. Evidence from previous years shows that economic growth alone does not reduce poverty or increase social welfare, unless it is accompanied by social equity policies that enable the most disadvantaged groups to benefit from this growth. Accordingly, changes are needed that are centered on the population, and on sustainable urbanization that will prioritize the social dimension. A city will only be able to be sustainable insofar as it addresses the most pressing social needs, such as poverty, inequality, precarious housing, and irregular settlements ( UN-Habitat, 2020 : p. 62–65). This can be achieved through urban planning and an inclusive government that counterbalances the functioning of the market and seeks ways to address social inequality by promoting integration and social cohesion, with an active, informed civil society that empowers local communities so they can participate in the development of their city.

The Case Study in Mexico City. Materials and Methods

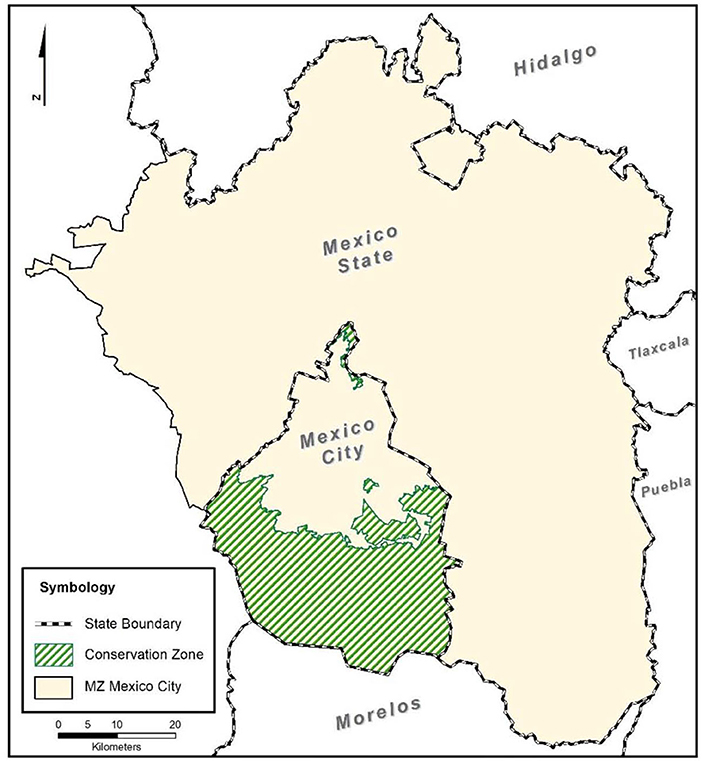

The study zone selected is a peri-urban area in the south and south-west of Mexico City (CDMX), with high ecological value where urban uses are prohibited, which at the same time is bound by a strict conservation policy due to its natural characteristics. It is called The Conservation Area or Zone (CZ) since it includes agricultural areas and natural vegetation. Encompassing an area of 87,297 ha, equivalent to 50% of the CDMX territory, it includes nine boroughs ( GDF, 2012 : p. 10). CDMX is one of the three states comprising the Mexico City Metropolitan Area (MCMA), currently made up of 76 political-administrative units divided into three states: Mexico City (CDMX) with 16 boroughs; the State of Mexico with 59 municipalities; and the State of Hidalgo with one municipality. Of these three, Mexico City was originally established in CDMX, from which it expanded into the other three states to form the current vast metropolitan conglomerate. In 2020, CDMX housed a population of 21.8 million inhabitants, 1.1 million of which are estimated to live in the CZ.

The CZ is a peri-urban area under considerable pressure from urban occupation, where informal settlements have been established in various municipalities in recent decades, even though this is prohibited by urban legislation. This territory has been analyzed from different perspectives, with several studies referring to extremely specific areas, such as boroughs or informal settlements, and highly focused urban or environmental policy problems (see Aguilar and Santos, 2011 ; Aguilar and Guerrero, 2013 ; Wigle, 2013 ; Aguilar and López, 2015 ; Perez-Campuzano et al., 2016 ; Calderón-Contreras and Quiroz-Rosas, 2017 ; Jimenez et al., 2020 ). However, there is a dearth of studies that approach this territory in an integral way, highlighting the main aspects of urban expansion and the transformation of land use, and the shortcomings in the implementation of urban containment and ecological preservation policies. Exceptions include the studies by Aguilar (2013) and Escandón Calderón (2020 ), and it is to this aspect that this paper seeks to contribute. One particularity is that most land ownership in the CA is ejido-based or communal, publicly owned land are not significant; this situation to a great extent has favored informal occupation.

In this study, the CZ is analyzed with three specific objectives: (i) examine demographic growth and the socio-economic characteristics of the population to determine the extent to which new urban occupations are associated with the presence of the poor; (ii) measure urban expansion throughout its territory in the past 20 years, identifying urban fragmentation and the presence of informal settlements, to determine the success of the measures to contain this process; (iii) evaluate changes in the main land uses, and identify the principal environmental impacts associated with urban expansion and other processes.

Methodology

Demographic growth and socioeconomic characteristics of the population.

This analysis used data from population censuses from 1990 to 2020, with growth rates and population totals being calculated for the different years. Socioeconomic variables were selected that best illustrate the conditions of poverty in which a substantial proportion of the population lives in the CZ, in comparison with the average conditions in CDMX, particularly as regards education, health, housing, services, and rates of ownership of household goods.

Urban Expansion in the CA

This expansion was quantified using multispectral satellite images (raster) for 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2020 based on information from high spatial resolution (SR) sensors: Landsat 4 TM (1990 with a SR of 30 m); SPOT 4 and 5 (2000 and 2010 with a SR of 10 m); and Rapid Eye (2020 with a SR of 5 m).

The method was supported by ArcMap 10.8. For each sensor, spectral bands were combined into false-color images to highlight urban or built areas. Pixels or sets of pixels with the same or similar spectral response were grouped together. These were associated with different geographical aspects captured by satellite images such as urban areas, bodies of water, vegetation, and open spaces. The satellite information analyzed in the first stage with the raster model using pixels was subsequently converted to a shape file to be verified, complemented, and improved using vector information from official sources (such as urban layout, infrastructure, and geostatistical areas), high resolution true and false color images and spatial analysis tools. In this case, the reference images used were Rapid Eye sensor images with a spatial resolution of 5 m and vector information from the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI).

Land Use Change

Land use change was monitored using the cross-tabulation matrix, which examines the changes in two stages and represents them in a transition matrix ( Pontius et al., 2004 ; Humacata, 2020 ). For this analysis, information sources on land use and vegetation coverage were used for three time series: 2000, 2010, and 2020. For 2000, the INEGI (National Institute of Statistics and Geography) Series II layer was used. Drawn up in 2001, its analysis is based on a scale of 1:250,000. For 2010, the maps produced by the Environmental and Territorial Organization Department (PAOT) in 2012 in the Geographical Atlas of The Conservation Zone of the Federal District, based on a scale of 1:20,000, were consulted. Finally, land use was explored through the Esri Land Cover 2020, which utilized Sentinel satellite imagery for global land cover processing. Coverage obtained from the three information inputs was reclassified into seven categories or classes of interest: Human Settlements, Forest, Chinampa, Body of Water, Wetland, Non-Forest Vegetation and Agricultural Zone.

The following procedure was adopted to enhance the information on land use and vegetation, particularly in the identification of human settlements. Satellite images were used for 2000 Landsat 4TM with a 30-m resolution. For 2010, SPOT 4 and 5 images with a 10-m resolution were used and for 2020, Rapid Eye images with a 5-m resolution were used. The method applied was an assisted classification of spectral enhancements in the histogram and band combinations.

Results: Mexico City's Urban Expansion and Land Use Change in the Conservation Area

The Conservation Area dates from the 1980 Federal District Urban Development Plan, which established zoning that delimited an urban and a non-urban area. The latter has a strict conservation policy, which is the forerunner of the current CZ ( Departamento del Distrito Federal, 1980 ). This zoning was subsequently updated in the 2006 Federal District Urban Development Law, in which the Conservation Area is maintained through land uses related to its ecological value such as ecological restoration, rural-agro-industrial production, ecological preservation, rural housing, and rural facilities ( Gobierno del Distrito Federal, 2006 ).

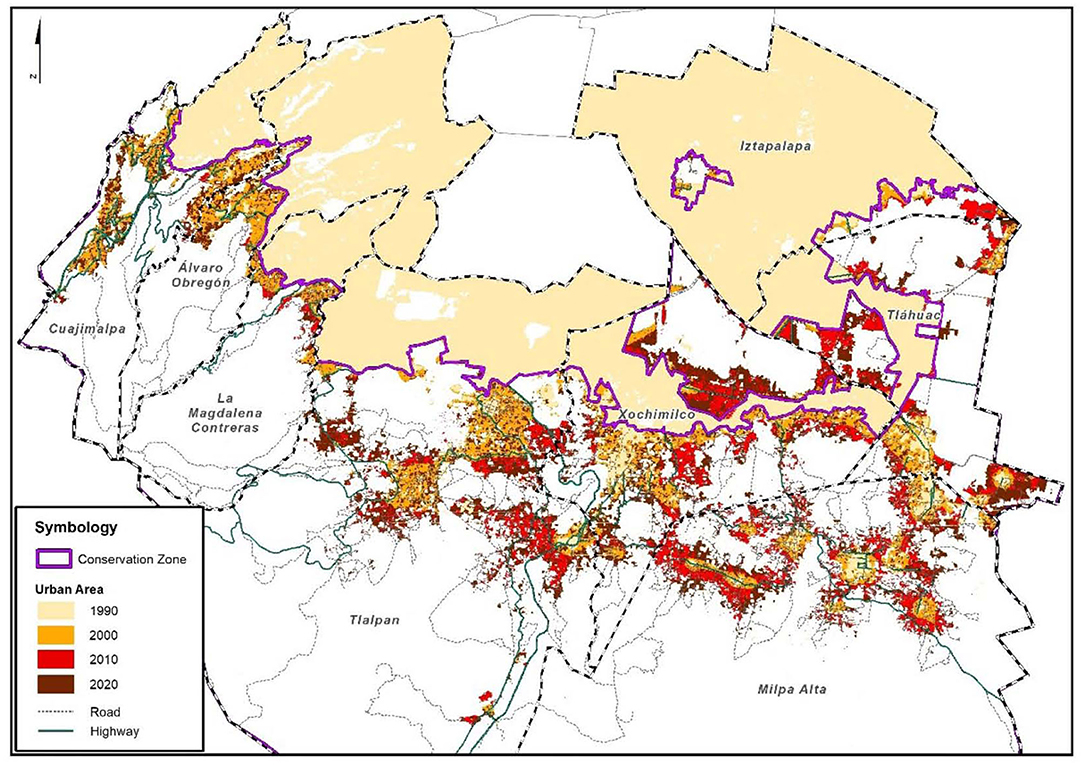

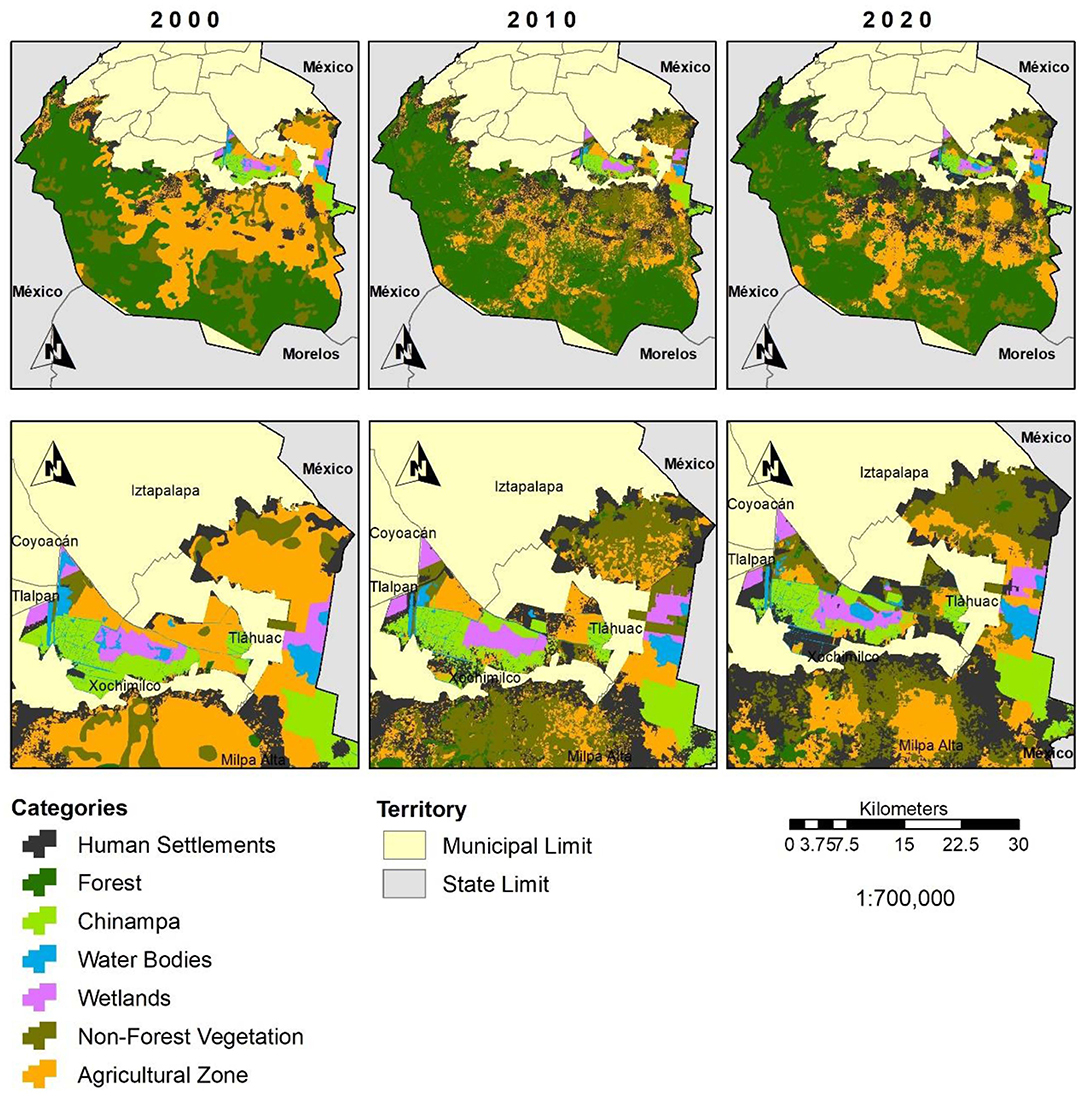

The CZ includes significant portions of the slopes of the Chichinautzin, Las Cruces, and Ajusco mountains. To the east it includes the Cerro de la Estrella, and the Sierra de Santa Catarina; as well as the lake plains of Xochimilco and Tláhuac 2 . This is an extremely important space for Mexico City because it is officially an area with high ecological value for several reasons. It comprises natural elements that provide crucial environmental services for the quality of life of its population; contributes to climate regulation through the presence of forest stands; recharges aquifers through infiltration; reduces atmospheric pollution through the retention of suspended particles; presents high biodiversity of flora and fauna; and offers recreational activities and scenic value ( GDF, 2012 : p. 10). However, although SC is a special category within urban legislation, with tight restrictions on urban occupation, its recent development has been marked by two processes: first, the emergence of a growing number of irregular settlements; and second, environmental deterioration due to a variety of factors (see Figure 1 ).

Figure 1 . Metropolitan zone of Mexico City. Location of the conservation zone. Elaborated from GDF, 2012 , CONAPO, 2015 , and INEGI, 2020 .

Regarding the first aspect, the area is home to 44 indigenous peoples or agrarian nuclei descended from indigenous societies that are historical communities with their own territory and cultural identity. These nuclei are associated with a communal and ejidal land tenure regime encompassing 71% of the CA. It is precisely in this type of social property that irregular settlements have been established. Over the years, it has been impossible to stop urban sprawl in the CZ even though urban land uses are explicitly prohibited. Since the 1980s, illegal means of land occupation have constituted significant forms of human settlement, and urban planning regulations have not been effectively implemented to control the land market, or restrict land availability in the CZ, or provide land for low-income groups in CDMX. Consequently, the local state has been forced to tolerate illegal occupations ( Aguilar, 1987 : p. 286–287, 2009: p. 45–47; Wigle, 2013 ; Rojas and Aguilar, 2020 ; Tellman et al., 2021 ). In recent decades there has been an increase in low-income settlements, and to a lesser extent of middle-class settlements ( Schteingart and Salazar, 2005 ; Aguilar, 2009 : p. 43–44).

Regarding the second process, urban expansion has contributed to environmental deterioration in several areas, which has led to the gradual disappearance of vast areas of the CZ. The destruction of natural vegetation has been reported, mainly as a result of clandestine tree felling and the destruction of grasslands, despite the fact that, to conserve these areas, the local government has offered economic incentives for environmental services (see Perez-Campuzano et al., 2016 ); the invasion and obstruction of waterways and aquifer recharge areas; the occupation of areas with high agricultural productivity such as chinampas; and wastewater discharge into the channels ( Bazant, 2001 : p. 137; Torres Lima and Rodríguez Sánchez, 2005 ; González Pozo, 2009 : p. 284–286; Rodríguez Gamiño and López Blanco, 2009 : p. 269; GDF, 2012 : p. 80; Rojas and Aguilar, 2020 ).

Population Growth and Socioeconomic Characteristics

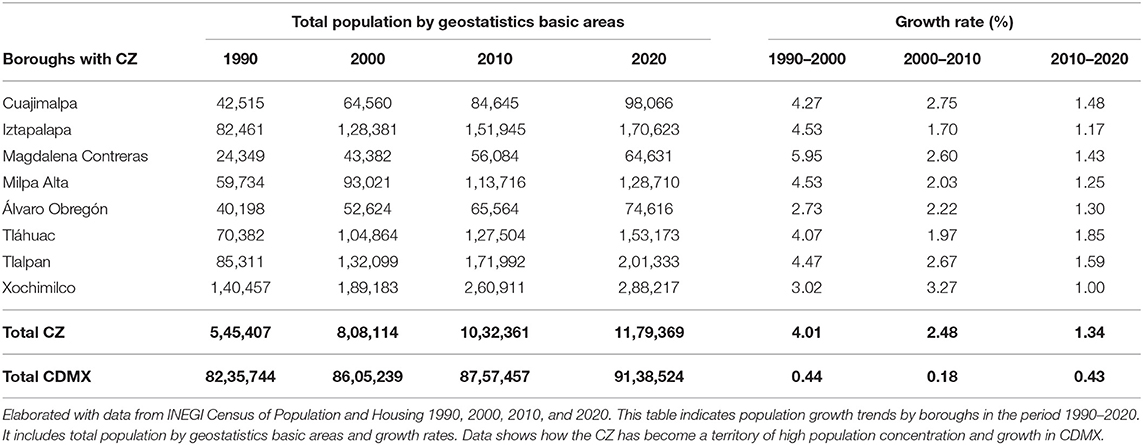

Population growth in the CZ increased sharply in the 1990–2020 period, from just over half a million inhabitants to 1.1 million inhabitants. In other words, the population doubled during the period, experiencing a much higher growth rate than the average for CDMX. In the 1990s, the population in the CZ registered the highest rate with 4% annual growth, while CDMX grew below 1%. During the past decade, although the growth rate in the CZ fell to 1.3%, this growth was more than twice that recorded in CDMX. The boroughs of Tlalpan and Tláhuac grew over 1.5% (see Table 1 ).

Table 1 . The conservation zone: demographic growth by boroughs, 1990–2000.

The CZ has become a territory of high population concentration and growth in CDMX and is therefore under strong urbanization pressure.

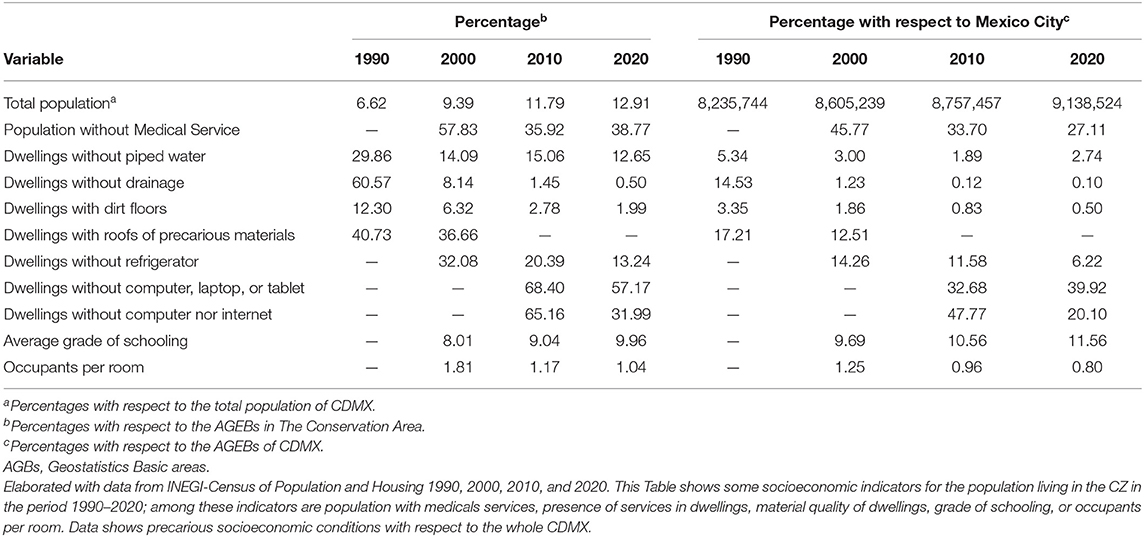

A characteristic feature of the CZ population is that it lives in precarious socioeconomic conditions. There are two main types of human settlements: on the one hand, original or traditional settlements that sprang up around agricultural activity, the latter although continues to exist, to a great extent it has been abandoned; and on the other, several informal settlements with self-built houses, poor-quality materials, and an acute shortage of services. Poverty levels are higher than the average for CDMX ( Aguilar and Guerrero, 2013 ).

These conditions are clearly reflected in the data in Table 2 . In terms of educational attainment, the population in this area has an average of 2 years less schooling than that of CDMX. In 2020, the proportion of the population without health insurance was 10% points above the CDMX average, reflecting greater job insecurity. Regarding housing conditions, there is a greater overcrowding and a high percentage of houses without indoor plumbing, while housing materials also reflect precarious conditions. The percentage of ceilings made from non-durable materials such as corrugated iron or cardboard, and dirt floors is higher in the CZ; and lastly, there is a shortage of household goods. The percentage of homes without a refrigerator, computer, or Internet is higher than the CDMX average.

Table 2 . The conservation zone: socioeconomic indicators, 1990–2020.

Urban Expansion and Fragmentation in the CZ, 1990–2020

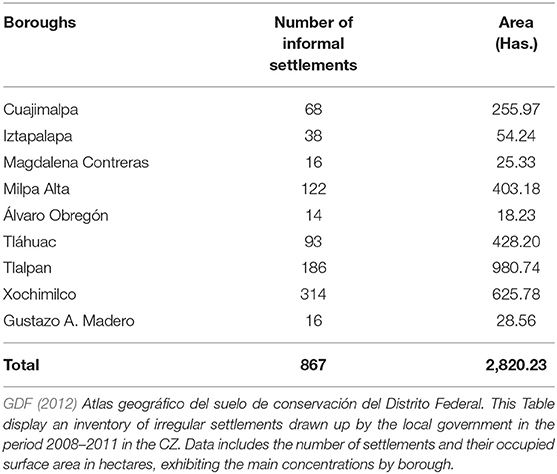

To calculate urban expansion in the CA, the traditional settlements that already existed in the middle of the last century, present in all the municipalities of the CA, were identified. Most of them are adjacent to the built area of CDMX. These towns represent “ urban cores ”, from which urban expansion has taken place, mostly in the form of informal settlements. This expansion has been defined as an “ urban fringe ” that represents the peripheral urban expansions around the towns. According to an inventory of irregular settlements drawn up by the local government in the period 2008–2011, there were 867 irregular settlements in the CZ, with an occupied surface area of 2,819 ha, most of which were concentrated in three municipalities: Xochimilco (314), Tlalpan, (186) and Milpa Alta (122) ( GDF, 2012 : p. 84) (see Table 3 ).

Table 3 . The conservation zone: number of informal settlements by borough 2008–2011.

Four indicators were used to calculate urban expansion: built area; rate of expansion; density; and degree of fragmentation of the expansion.

Urban Expansion Area

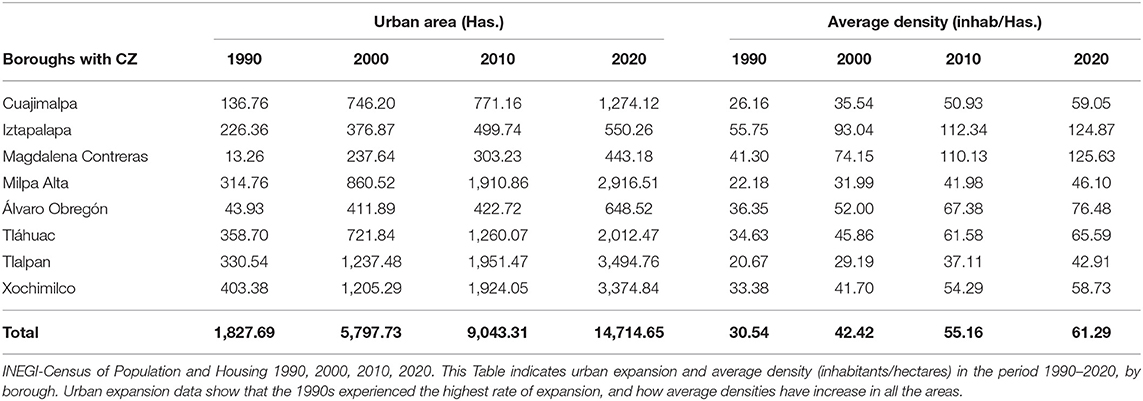

Figure 2 shows urban expansion in the period 1990–2020 for the entire CZ in the south of CDMX calculated using satellite images. The map shows two key aspects: first, extensive, continuous urban expansion over the past 30 years; and second, clear urban fragmentation in the most peripheral areas. Regarding urban expansion, during the period studied, the CZ experienced urban expansion of just over 14,000 ha; the periods of greatest growth being the 1990s (3,970 ha), and the last decade from 2010 to 2020 (5,671 ha). At the borough level, urban expansion appears to be related to the number of irregular settlements that already existed in those territories. The boroughs with the greatest urban expansion were Tlalpan, Xochimilco and Milpa Alta, where there were expansions over 1,000 hain the past decade (see Table 4 ).

Figure 2 . The conservation zone: urban expansion, 1990–2020. Own elaboration from satellite images from sensors Landsat 4 TM; SPOT 4 and 5; Rapid Eye; and information from GDF, 2012 and INEGI, 2020 .

Table 4 . The conservation area: urban expansion and average density (inhab/Ha), 1990–2020.

Urban Expansion Rate

The speed of growth in the CA shows that the 1990s experienced the highest rate of expansion. During that period, the growth rate was above 12%, subsequently decreasing in the early decades of this century to just over 4%. In the past decade, the growth rate for the boroughs with the greatest expansion was 6%, for example, in Tlalpan, Xochimilco, and Cuajimalpa. It should be noted that the rate of urban expansion has stabilized, yet remains high, and cannot be said to have stopped. In fact, the rate of urban expansion is well above the population growth rate mentioned above. In the past decade, it was three times higher. Whereas, the population grew at an average rate of 1.34% throughout the CZ, urban expansion did so at a rate of 4%.

Population Density

Population dynamics at local levels reflect concentration or deconcentration processes. The aim of this section is to provide evidence to determine whether the new urban expansions are denser than the previous ones, given the current peri-urbanization process. Densities were calculated by estimating the size of the population living in each of the smallest statistical units in the census (basic urban geostatistical areas) with built areas, dividing it by the areas of these units and taking the average for each borough. The data show that average densities have increased in all the areas with urban sprawl in the CZ over the past 30 years. The average population density throughout the CZ rose from 30.5 to 61.2 inhabitants per hectare, in other words, density doubled in 30 years, in practically all the boroughs. Nevertheless, there are two municipalities that had twice the average density of the CZ in 2020, namely Magdalena Contreras and Iztapalapa, with densities above 125 inhabitants/ha. In other words, these figures obviously show that land consumption has remained constant in recent decades, and that there has been a process of redensification both within traditional settlements and the irregular ones existing on their peripheries.

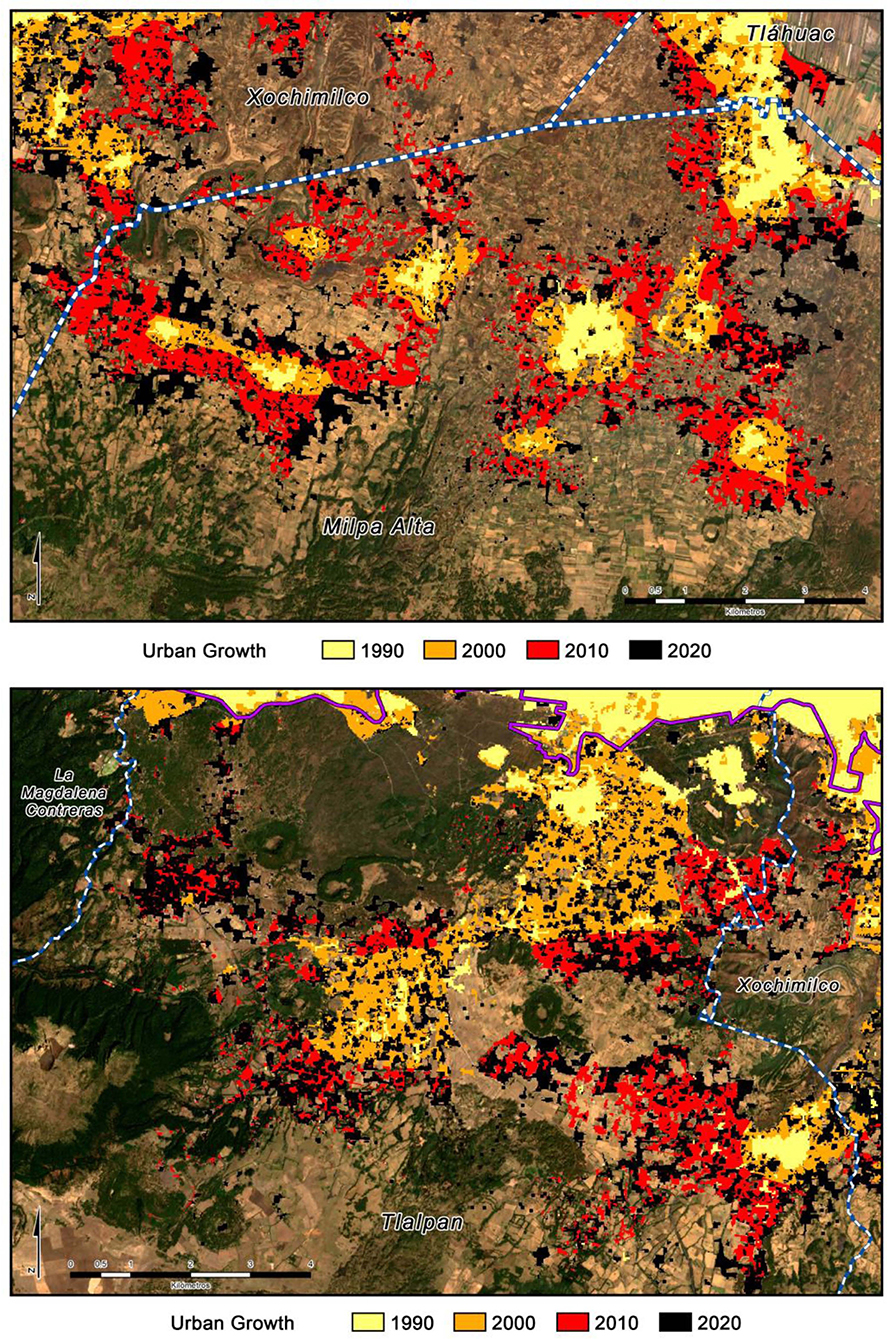

Fragmentation of Urban Expansion

With respect to urban fragmentation, Figure 3 shows a zoom of two boroughs (Tlalpan and Milpa Alta), where informal urban sprawl has been particularly widespread, which are representative examples of this phenomenon. The figures show two key aspects: first, until 1990, urban cores had expanded in a continuous, contiguous way, but during the 1990s, although this expansion remained contiguous, it was already extremely discontinuous in that it contained many gaps. Second, during the next two decades of this century, the urban fringes in the two boroughs followed an extremely dispersed, discontinuous pattern of occupation, with the presence of urban patches separated from the urban cores. This pattern is extremely noticeable, particularly in the municipalities of Tlalpan and Milpa Alta but is also visible in the lake area of the boroughs of Xochimilco and Tlahuac. This type of fragmented expansion has triggered the loss of forest and non-forest vegetation.

Figure 3 . The conservation zone: zoom of urban expansion in the Boroughs of Milpa Alta and Tlalpan, 1990–2020. Own elaboration from satellite images from sensors Landsat 4 TM; SPOT 4 and 5; and Rapid Eye.

Urban fragmentation has two main origins in the CZ: illegal subdivision, and creeping urbanization (also called “ant urbanization”). In illegal subdivision, an intermediary or unauthorized land divider purchases a large plot of land with several lots, obtained through loopholes in land ownership, or by arrangement with the original owners such as ejidatarios , holders of shares in common lands. These land dividers usually charge more for lots near towns where there are services and better transport links, and less for lots that are further away. The population with fewest resources settles in more scattered, distant lots, creating a highly dispersed pattern that will densify over time. Creeping urbanization involves the individual sale of lots in social or private property in already established settlements. Available lots are in peripheral areas, which leads to widely dispersed dwellings, which are irregular and may have some services. This process causes slow, discontinuous settlement ( Aguilar and Santos, 2011 ; Aguilar and López, 2015 ; Tellman et al., 2021 : p. 6–7).

Nonetheless, it has been found that on conservation land, residents who purchase a lot value the absence of slopes and the presence of drainage more than the presence of open spaces. Access to transport is also regarded as a significant advantage. This shows that buyers attempt to be as close to existing towns as possible rather than an extremely rural area near to high-value environmental zones because they realize they are buying in an informal land market (Martínez Jimenez et al., 2017 : p. 108).

This analysis shows that municipalities with the greatest urban expansion are critical areas in land use change and should be treated as areas for special attention within urban and environmental policy. It is paradoxical that the CA is an area with high ecological value, with an explicit prohibition of urban occupation, and that the areas occupied by irregular settlements should have grown to this size. Most land ownership in the CA is ejido-based or communal, meaning that property rights are guaranteed to rural communities (called agrarian nuclei), but not to individual farmers. Accordingly, the community owns all the land, and everyone has a piece of land they are entitled to work. The community's rights to the land were unalienable and until 1992 ejidos could not be sold, nor could the land be used for other purposes. The sale of ejido land was therefore legally considered non-existent ( Azuela, 1997 : p. 222–224; Tomas, 1997 : p. 26; Duhau, 1998 : p. 150–151; Ward, 1998 : p. 194–195). But in 1992, Article 27 of the Mexican Political Constitution was amended and the privatization of ejido land authorized, triggering an enormous expansion of urban peripheries that contradicted the principles of sustainable development ( Olivera, 2015 : p. 160–164).

As a result of these changes, thousands of hectares of communal and ejido land on the outskirts of Mexico City were illegally occupied by settlements inhabited by the poor, from the second half of the 1990s onwards. The most common method for the occupation of ejido or communal land has been the purchase of lots from the purported owner who has not complied with the legal norms governing these transactions. In this case, the owner breaks the law, and the result is clandestine divisions of land with which the owner of the land agrees, but there is also complicity on the part of political actors, who are aware of these transactions and choose to ignore them ( Aguilar and Santos, 2011 : p. 651). There are two crucial aspects that explain this tolerance of informal urbanization: first, it is an escape valve for the state which, due to its inability to solve the problem of housing for the poor population, uses this political patronage as a form of social stability ( Varley, 2006 : p. 209). And second, there is enormous impunity for those who violate the law and subdivide ejido and communal land without complying with the rules, confident that subsequent regularization processes will guarantee the formalization of illegal properties, thereby encouraging new processes of informality ( Azuela, 1997 : p. 229). This process reveals the complicity of social actors together with a social pact of tolerance and non-intervention by the local state in irregular urbanization.

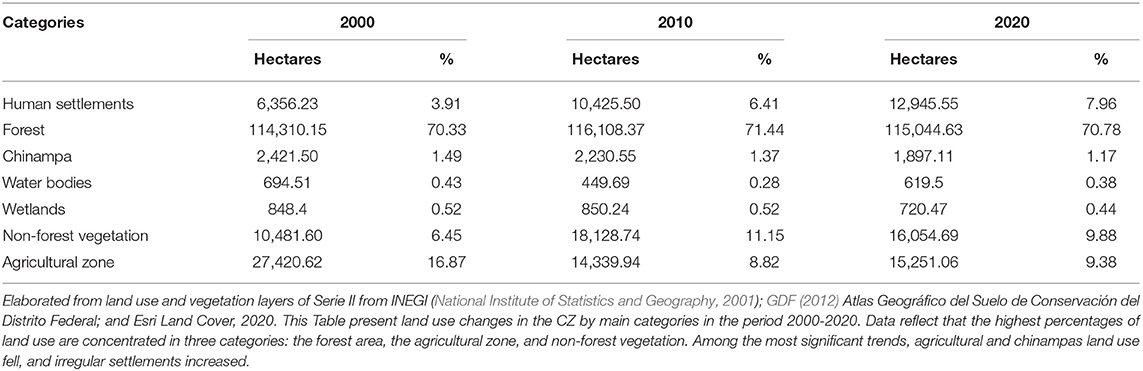

Land Use Changes. Environmental Impact Hot Spots

Over the past 20 years, land use coverage in the CDMX CZ has shown a similar composition in percentages, although there are changes that reflect significant trends. The highest percentages of land use are concentrated in three categories: the forest area, encompassing 70% of the CA; the agricultural zone with a percentage that varied from 16.8 to 9.3 during this period; and non-forest vegetation, which increased from 6.4 to 9.8 per cent during the same period (see Table 5 ).

Table 5 . The conservation zone: land use changes by main categories, 2000–2020.

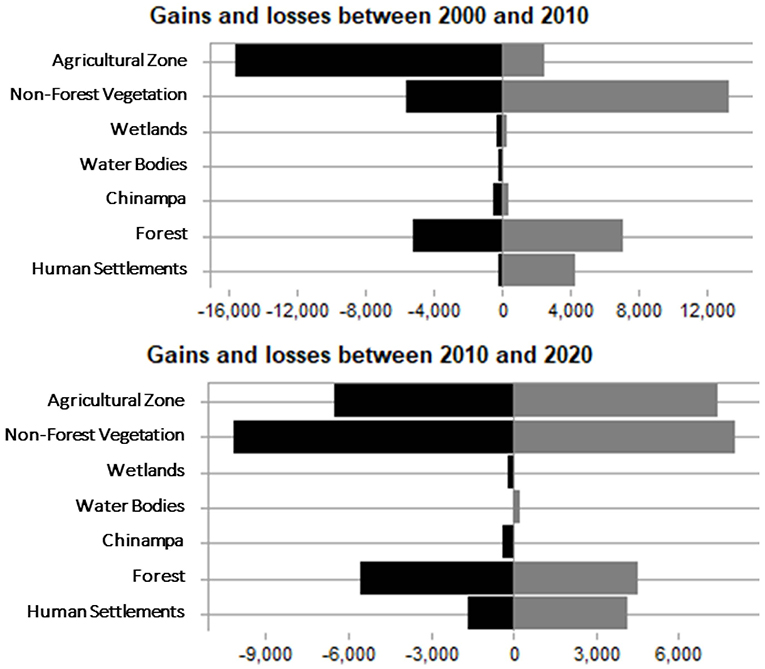

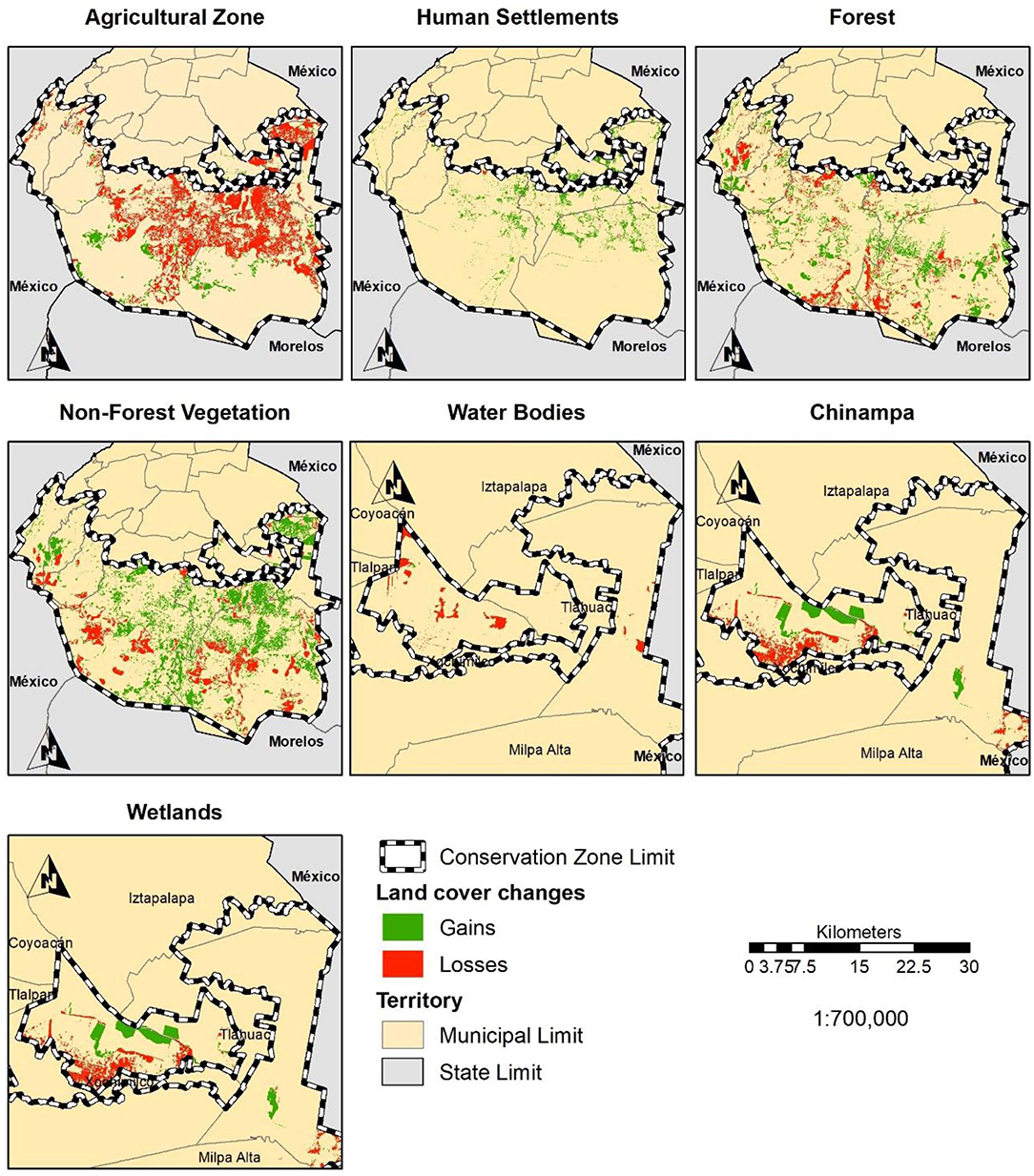

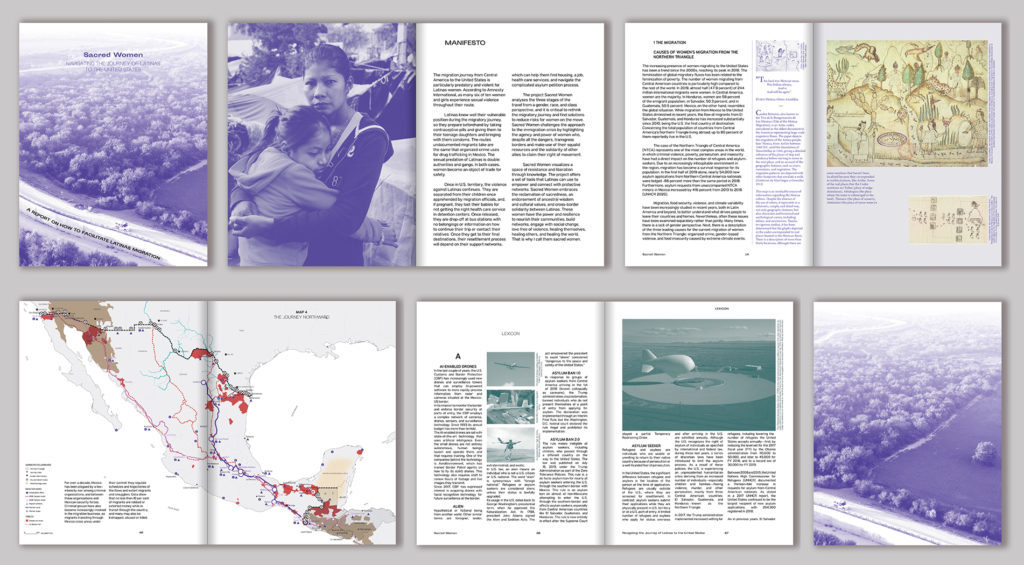

An analysis of land use changes in the period 2000–2020 shows that the three most significant gains and losses occurred with areas higher than several thousand hectares, which in turn experienced the most significant environmental deterioration. First, the size of the agricultural area with the second highest percentage in the CZ, 16.8%, fell from 27,420 to 15,251 ha, and its share to just 9.3%. Second, irregular human settlements increased from 6,356 to 12,945 ha, practically doubling their area; and third, the area of non-forest vegetation increased from 6.4 to 9.8%. Areas with fewer than a thousand hectares, yet with a significant environmental impact, include the chinampas, which lost just over 500 ha, and decreased their share from 1.5 to 1.1% (see Table 5 ).

These changes show a dynamic of powerful environmental impacts that can be observed in the sequence of maps of land use changes (see Figure 4 ). The urban occupation process has steadily continued to the detriment of agricultural areas close to traditional settlements on the slopes of the mountains, and areas with forest and non-forest vegetation, but also in chinampa areas in the flat part of the CZ, in the boroughs of Xochimilco and Tláhuac (see Figure 4 ). Agricultural areas that have existed for several decades have been reduced by urban encroachment, but also by the abandonment of farming activities, since the younger population prefers to work in urban occupations given the proximity of the city; their decrease is clearly visible in the sequence in Figure 4 . And the increase in non-forest vegetation can be explained by deforestation, which exists in the highest part, and the invasion of abandoned agricultural areas. These changes are clearly visible in the forest zone in the south of the CZ with patches of this type of vegetation and on the edge of the high, flat zones.

Figure 4 . The conservation zone: evolution of land use and vegetation change, 2000–2020. Elaborated from land use and vegetation layers of Serie II from INEG I ( National Institute of Statistics and Geography, 2001 ); GDF (2012) Atlas Geografico del Sue lo de Conservaci6n del Distrito Federal; and Esri Land Cover, 2020.

This land use dynamic is partly the result of the failure of environmental conservation programs, two of which serve as examples: the federal Environmental Services Payment Program (PSA) and the local Funds to Support the Conservation and Restoration of Ecosystems through Social Participation Program (PROFACE). Although environmental degradation has exceeded the budget allocated for both programs, the latter have been widely accepted by the rural population, because they constitute a means of obtaining additional resources (subsidies) required for their survival. However, these problems have not stopped the changes in land use or the loss of natural spaces, especially in adjoining areas, due to the high demand for land for residential use, and its consequent illegal sale. PROFACE promotes productive projects, such as ecotourism, corn farming, nopal, dairy production, and trout farming. These projects contribute less to ecosystem conservation than to the productive diversification of this sector of the population. The PSA has several complications reflected in the constant change of operating rules, complex administrative procedures due to the lack of a comprehensive evaluation of its effects, and low, temporary wages that ultimately fail to improve the environmental situation ( Perevochtchikova and Torruco Colorado, 2013 : p. 20–21).

Land use change involves a dynamic process of gains and losses. In other words, in each period, a specific land use can gain surface area, yet also lose coverage to other uses. This process can be observed in Figure 5 . For example, the agricultural area experienced major coverage losses from 2000 to 2010 in various locations, together with a slight increase in surface area in other locations. In the following period, however, although the loss of coverage continued, it experienced a significant increase in area, yet the final balance for the period is one of overall loss. The case of human settlements is clearer in terms of surface gains in the two periods, with very few losses. The case of the forest is striking because, although it experienced losses during each period due to other uses such as urban encroachment and non-forest vegetation, it also made similar gains, in terms of reforestation, which has enabled it to maintain the same area.

Figure 5 . The conservation zone: gains and losses by land use categories, 2000–2020. Elaborated from land use and vegetation layers of Serie II from INEGI ( National Institute of Statistics and Geography, 2001 ); GDF (2012) Atlas Geograf ico de/ Sue/a de Conservaci Ò n de/Distrito Federal; and Esri Land Cover , 2020.

Finally, Figures 6 , 7 contains a sequence of maps indicating the losses and gains in the main categories of land use changes throughout the CZ, in the period 2000–2020. These maps show the location of the most critical hot spots for environmental change in each of the boroughs. The most striking features are the losses of agricultural use in the central and eastern zone of the CZ, which are greater in the first period than the second; and the losses of chinampas in the boroughs of Xochimilco and Tláhuac, during both periods. The main increases in human settlement areas occurred in the boroughs of Tlalpan, Xochimilco and Milpa Alta; and in non-forest vegetation in the municipalities themselves, with both categories experiencing similar gains in the two periods.

Figure 6 . The conservation zone: sequence of maps of land use gains and losses by category, 2000–2010. Elaborated from land use and vegetation layers of Serie II from INEG I ( National Institute of Statistics and Geography, 2001 ); GDF (2012) Atlas Geografico del Sue lo de ConservaciÒn del Distrito Federal; and Esri Land Cover, 2020.

Figure 7 . The conservation zone: sequence of maps of land use gains and losses by category, 2010–2020. Elaborated from land use and vegetation layers of Serie II from INEG I ( National Institute of Statistics and Geography, 2001 ); GDF (2012) Atlas Geografico del Sue lo de ConservaciÒn del Distrito Federal; and Esri Land Cover, 2020.

The chinampa zone has a high risk of contamination of its aquifers, due to the influx of wastewater from irregular human settlements on the banks of the canals, which lack drainage services. The case of San Francisco Caltongo in the Borough of Xochimilco is emblematic, in that it is the neighborhood in the lake area with the highest amount of residential wastewater discharges into the canals. Most dwellings lack public drainage, and the population has chosen to dispose of the wastewater from their homes in septic tanks, and green areas such as chinampas , vacant lots or the canals ( Rojas and Aguilar, 2020 : p. 54–55). The lake area of Xochimilco contains 917 plots of land that deposit ~1,374 wastewater discharges into the canals. Of these discharges, 771 are considered greywater, and 603 sewage ( Flores et al., 2015 ).

Another risk of contamination to which aquifers are exposed is the use of agrochemicals in agricultural production, which increases the nitrogen and phosphorus load in water. This encourages excess growth of aquatic weeds, namely the water lily, which in turn affects the fauna as well as obstructing navigation and sometimes permanently covering the canals ( San Miguel Villegas, 2010 : p. 158). Another negative effect associated with water resources is differential subsidence, both in the canal area due to the drop in water levels and the change in the direction of flow, and in urban areas due to intensive groundwater extraction and limited infiltration for recharging the aquifer. The most overexploited aquifers are those in Xochimilco and Tláhuac ( San Miguel Villegas, 2010 : p. 159).

A key factor is that in the chinampa area, young people are no longer interested in traditional agricultural activities. Families that can give their children a higher education no longer envisage them returning to work on the plots of agricultural land, partly because this is considered a difficult, poorly paid job, and partly because there is a negative perception of agriculture, which is regarded as a socially inferior, backward occupation. Farmers do not wish to see their children working in agriculture, preferring them to “have higher aspirations in their lives” ( Rubio et al., 2020 : p. 213).

The CZ is a peri-urban territory that has been undergoing an urban and rural transition for three decades. Three main driving forces have modified its land use: first, significant pressure from informal urban expansion, which has continued to advance and is driven by the poor population. This advance has been facilitated by the illegal subdivision of communal and ejido property. Second, according to urban legislation, the CZ is a conservation area because of its high ecological value for the city, where urban uses are prohibited, yet it is unfortunately subject to processes of significant environmental deterioration. And third, urban policy has failed to reconcile these two driving forces in land use change (urban and environmental) or to find solutions at the level of CDMX or the metropolis. This lack of solutions prevents progress in the issue of social justice for poor residents, who continue to live in precarious conditions with insecure land tenure, or in concrete actions to achieve a model of urban sustainability in the CZ.

The advance of informal urban expansion shows that the social actors involved, ejido and communal owners, continue to act arbitrarily, subdividing the land, allowing more settlements, and increasing the densification of existing ones, causing the fragmentation of land use. This process increases the concentration of the poor living in precarious conditions and contributes to environmental deterioration, as exemplified by the informal settlements in the chinampas area. Local government obviously lacks the mechanisms to stop urban expansion, coupled with the fact that there is no land occupation model within urban policy to reconcile urban expansion with environmental conservation. After decades of tolerance of informal urbanization, this type of settlement has been legitimized. Nowadays, eviction is only seen in small settlements in highly specific locations, while housing solutions have yet to be provided for the entire low-income population.

In terms of the ecological value of the CA, the destruction of the original landscape is evident, which has led to environmental deterioration, expressed through several processes: the destruction of the original vegetation such as forest areas; the occupation and abandonment of agricultural areas, leading to the disappearance of the chinampas; urban patches without connectivity and a dearth of services that cause the soil and water aquifers to deteriorate; soil sealing in recent urban areas preventing infiltration, all of which negatively impacts environmental services for the city. Despite the high priority that exists in the legislation and political discourse for the conservation of the entire CZ, to date, priorities have focused on certain aspects such as preventing clandestine logging, reforestation and the preservation of biodiversity, and the creation of parks and recreational areas. However, there is no comprehensive conservation policy for the entire CA with extremely strict zoning, or a solid policy to support agricultural activities ( Torres Lima and Rodríguez Sánchez, 2005 ; Avila-Foucat, 2012 ; Escandón Calderón, 2020 : p. 19), and traditional or indigenous peoples ( Carmona Motolinia and Tetreault, 2021 ).

Urban and environmental policies have failed to address the enormous challenge of reconciling informal urban expansion with environmental conservation in the peri-urban area of the CA. Urban and environmental regulations initially ignored irregular occupation, and have subsequently been ineffective in incorporating a strategy into their plans and regulations to manage irregular settlements, in terms of the regularization of land tenure, relocations, and definition of territorial reserves ( Aguilar and Santos, 2011 : p. 661). The most likely explanation is that the introduction of strict measures regarding land use could jeopardize clientelistic relations with the communities.

The data would appear to confirm the existence of a social pact of tolerance and non-intervention between the local state and the social actors involved in irregular urbanization. This position formalizes the informal and tolerates the occupation of the CZ, making it impossible to advance toward a model of urban sustainability at the city and metropolitan level. Solutions for informal settlements have been postponed for over 30 years and environmental deterioration continues. This inaction reflects the failure to prioritize environmental over political dimensions of urban issues. Promises of regularization have continued for many years as part of clientelistic practices ( Rojas and Aguilar, 2020 : p. 59; Wigle, 2020 : p. 67). Faced with the lack of solutions to informal settlements, this population lives in a situation of constant uncertainty, because they are neither evicted from a territory they should not be occupying, nor do they regularize their land tenure. As Wigle (2013 : p. 586) points out, these settlements are part of a planning limbo; they live in a sort of “gray area” within the CZ. But this division between the formal and the informal, and the lack of solutions to informal ownership, reproduces the social class division between groups that legally own a plot of land or a house, and low-income groups that are still unable to obtain them. Urban policy thereby fails to address structural social inequity through access to land and housing.

Conclusions

Urban expansion in cities in developing countries is inexorable, and as their economies become more solid, their cities will grow increasingly quickly. The key is to find a means of channeling their dispersed, fragmented growth on the peripheries. In terms of urban morphology, peri-urbanization is dominating the urban expansion model and densities are steadily increasing in these peripheries, exerting strong environmental pressure. Managing their expansion in a more compact, continuous way, and sustainably, is a priority of urban and environmental policy. Against this background, it is essential to define the acceptable degrees of dispersion and fragmentation in each case.

The case of the CZ in CDMX is a clear example of a fragmented peri-urban expansion process in an area with high ecological value. The CZ provides essential environmental services for the quality of life of the population, and its preservation is of paramount importance. However, for decades, local government has proved ineffective in controlling urban expansion, and faces serious dilemmas to stop the changes in land use that damage the environment of this territory. It is crucial to have a strategy that incorporates several essential principles: a territorial principle that emphasizes the fact that it is essential to address the way the city expands; and a territorial strategy that explicitly indicates the amount of land required for future growth, and how it will be achieved or resolved, particularly in the CA; it is necessary a particular strategy and mechanisms to control and shape urban expansion in each settlement, and stop illegal sales; increase densification until certain limits, and have a system of monitoring and penalties for those that contravene the land-use rules.

A principle of governance is required that will achieve a new social pact, addressing the socio-environmental processes that are the driving forces of land use change, and ensuring a dialogue with social actors to reconcile the dilemma of environmental preservation with urban expansion; for example, make agreements with social land owners to take actions to promote proper, legal land subdivisions, and also to preserve the ecological value of the zone through environmental services, and re-activation of agricultural activities with important financing support; these action can prevent rural land from becoming poor informal settlements; it is necessary to accelerate property formalization processes for accessing property titles, urban services and social programs.

There must also be a principle of social equity that meets the basic needs of the low-income population living in the CZ to reduce socio-residential segregation and inequities within the metropolitan area of CDMX; socio-economic inequality, relates to structural conditions that increase demand for cheaper land, a way to counteract this situation is to creates jobs with productive activities in the municipalities of the zone, and look for strategies to offer cheaper land or housing to the poorer groups; and housing improvement program for rural and urban areas.

And lastly, there must be a principle of sustainability that incorporates the environment into all sectoral actions, at the lowest cost and with the highest possible efficiency to occupy vacant land in a more orderly manner; it would be recommendable to apply mitigation and adaptation strategies in the context of climate change and urban expansion with monetary compensation, this could create an opportunity for the people living there and empower them with an asset. All these actions can make the city more productive, accessible, inclusive, and sustainable, all of which are essential objectives of a fair, well-balanced public policy.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

AA proposed the main argument of the article, developed the conceptual argument, selected the main information inputs, defined the main structure of the paper, and developed the discussion and conclusions of the paper. MF organized and developed main information inputs of the urban expansion section, selected the satellite images, interpreted them for the period 1990–2020, and calculated the urban expansion for periods and by boroughs. LL organized and calculated the main land use changes in the period 2000–2020, did the calculations from the main categories defined, worked out the compatibility of information sources for the measurements, and calculations related main land use categories with each borough. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by National Autonomous University of Mexico.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^ It is estimated that when the population of cities in developing countries doubles, from 2 billion in 2000 to 4 billion in 2030, the area occupied by cities will have tripled ( Angel, 2014 : p. 224).

2. ^ It should be noted that to the north of CDMX it also includes a small portion of the Sierra de Guadalupe and the Cerro del Tepeyac, although this area is not included in this analysis.

Abramson, D. B. (2016). Periurbanization and the politics of development-as-city-building in China. Cities 53, 156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2015.11.002

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Aguilar, A. G. (1987). La Política Urbana y el Plan Director de la Ciudad de México: proceso operativo o fachada política. Estudios Demográficos y Urbanos . 2, 273–299. doi: 10.24201/edu.v2i2.629

Aguilar, A. G. (2008). Peri-urbanization, illegal settlements and environmental impact in Mexico City. Cities 25, 133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2008.02.003

Aguilar, A. G. (2009). Urbanización Periférica e Impacto Ambiental. El Suelo de Conservación en la Ciudad de México, in Periferia Urbana, Deterioro Ambiental y Reestructuración Metropolitana , eds. Aguilar, A. G., and Escamilla, I., (México: Instituto de Geografía-UNAM, Miguel Angel Porrúa), 21–52.

Google Scholar

Aguilar, A. G. (2013). “Sustentabilidad Urbana y Política Urbana-Ambiental. La Ciudad de México y el Suelo de Conservación,” in La Sustentabilidad en la Ciudad de México. El Suelo de Conservación en el Distrito Federal , eds. Aguilar, A. G., and Escamilla, I., (Mexico: Instituto de Geografía-UNAM, Miguel Angel Porrúa Editor), 23–66.

Aguilar, A. G., and Guerrero, F. L. (2013). Poverty in peripheral informal settlements in Mexico City: the case of Magdalena Contreras, Federal District. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 104, 359–378. doi: 10.1111/tesg.12012

Aguilar, A. G., and López, F. M. (2015). Water insecurity among the urban poor in the peri-urban zone of Xochimilco, Mexico City. J. Latin Am. Geogr. 8, 97–123. doi: 10.1353/lag.0.0056

Aguilar, A. G., and Santos, C. (2011). Informal settlements' needs and environmental conservation in Mexico City: an unsolved challenge for land-use policy, Land Use Policy 28, 649–662. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2010.11.002

Aguilar, A. G., and Ward, P. M. (2003). Globalization, regional development, and Mega-City expansion in Latin America: analyzing Mexico City's peri-urban hinterland. Cities 20, 3–21. doi: 10.1016/S0264-2751(02)00092-6

Angel, S. (2014). Planeta de Ciudades, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Bogotá: Universidad del Rosario, 421.

Avila-Foucat, S. (2012). Diversificación Productiva en el suelo de Conservación de la Ciudad de México. Caso San Nicolas Totolapan. Estudios Sociales UNAM . XX, 354–375. Available online at: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=41723301014

Azuela, A. (1997). “Evolución de las políticas de regularización,” in El acceso de los pobres al suelo urbano , edsAzuela, A., and Tomas, F., (Mexico City: Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales/PUEC/CEMCA, UNAM [National Autonomous University of Mexico]), 221–231.

Bazant, J. (2001). Periferias Urbanas. Ed. Trillas. Mexico: Expansión Urbana Incontrolada de Bajos Ingresos y su Impacto en el Medio Ambiente.

Brandful Cobbinah, P., and Nsomah Aboagye, H. (2017). A Ghanaian twist to urban sprawl. Land Use Policy. 61, 231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.10.047

Calderón-Contreras, R., and Quiroz-Rosas, L. E. (2017). Analysing scale, quality and diversity of green infrastructure and the provision of Urban Ecosystem Services: a case from Mexico City. Ecosyst. Serv. 23, 127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2016.12.004

Carmona Motolinia, J. R., and Tetreault, D. (2021). Pueblos originarios, formas de comunalidad y resistencia en Milpa Alta. Revista Mexicana Ciencias Políticas y Sociales, UNAM, Nueva Época, Año LXV . 241, 155–180. doi: 10.22201/fcpys.2448492xe.2020.241.70796

CONAPO (2015). Delimitación de Zonas Metropolitanas de México . Available online at: https://www.gob.mx/conapo/documentos/delimitacion-de-las-zonas-metropolitanas-de-mexico-2015

Coq-Huelva, D., and Asían Chavez, R. (2019). Urban sprawl and sustainable urban policies. A Review of the Cases of Lima, Mexico City and Santiago de Chile. Sustainability 11, 5835. doi: 10.3390/su11205835

Da Gama Torres, H. (2011). Environmental Implications of Peri-Urban Sprawl and the Urbanization of Secondary Cities in Latin Washington, DC, America, Inter-American Development Bank.

Departamento del Distrito Federal (1980). Plan de Desarrollo Urbano del Distrito Federal I, Nivel Normativo . Mexico: Diario Oficial de la Federación.

Douglas, I. (2006). Peri-urban ecosystems and societies: traditional zones and contrasting values, in The Periurban Interface , eds. Macgregor, S. D., and Thompson, D., (London: Earthscan), 18–29.

Duhau, E. (1998). Hábitat popular y política urbana . Mexico City: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Azcapotzalco, Miguel Ángel Porrúa.

Escandón Calderón, J. A. (2020). Visiones desiguales sobre la conservación en la periferia urbana: ganadores y perdedores del suelo de conservación en la Ciudad de México. Soci Ambiente 23, 1–29. doi: 10.31840/sya.vi23.2149

Ewing, R. H. (2008). “Characteristics, causes, and effects of sprawl: a literature review,” in Urban Ecology An International Perspective on the Interaction Between Humans and Nature , eds.John Marzluff, M. J. M., Shulenberger, E., Endlicher, W., Alberti, M., Bradley, G., Ryan, C., Simon, U., and ZumBrunnen, C., (Berlin: Springer), 519–535.: 10.1007/978-0-387-73412-5_34

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Flores, M., Pérez, G., and Iturbe, R. (2015). Censo de descargas de aguas negras y grises en los canales de Xochimilco. México: Proyecto para rehabilitar el área de canales en Xochimilco, San Gregorio Atlapulco y San Luis Tlaxialtemalco, Secretaria de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación e Instituto de Ingeniería, Gobierno de la CDMX, UNAM.

GDF (2012). Atlas geográfico del suelo de conservación del Distrito Federal . México: Secretaría del Medio Ambiente, Procuraduría Ambiental y del Ordenamiento Territorial del Distrito Federal, D.F. 96.

Geneletti, D., La Rosa, D., Spyra, M., and Cortinovis, C. (2017). A review of approaches and challenges for sustainable planning in urban peripheries, Landscape Urban Plan . 165. 231–243. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.01.013

Gibbs, D., and Krueger, R. (2007). Containing the contradictions of rapid development? new economy spaces and sustainable urban development, in The Sustainable Development Paradox. Urban Political Economy in the United States and Europe , eds. Krueger, R., and Gibbs, D., (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 95−122.

Gilbert, A. (2003). Is urban development in the third world sustainable? in The Human Sustainable City , eds. Fusco Girard, L., . (Ashgate: Challenges and Perspectives from the Habitat Agenda), 71–88.

Gobierno del Distrito Federal (2006). Ley de Desarrollo Urbano del Distrito Federal. México: Gaceta Oficial del Distrito Federal.

González Pozo, A. (2009). Las Chinampas de Xochimilco. Periferia Ancestral en Peligro, in Periferia Urbana, Deterioro Ambiental y Reestructuración Metropolitana , eds. Aguilar, A. G., and Escamilla, I., (México: Instituto de Geografía-UNAM, Miguel Angel Porrúa), 273–289.

Haughton, G., and Hunter, C. (1994). Sustainable Cities, Regional Policy and Development, Series 7. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Heynen, N., Kaika, M., and Swyngendow, E. (2006). “Urban political ecology. Politicizing the production of urban natures,” in The Nature of Cities - Urban Political Ecology and The Politics of Urban Metabolism , eds. Heynen, N., Kaika, M., and Swyngendow, E., (London: Taylor and Francis), 1–20.

Hudalah, D., and Firman, T. (2012). Beyond property: industrial estates and post-suburban transformation in Jakarta Metropolitan Region. Cities 29, 40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2011.07.003

Humacata, L. (2020). Sistemas de Información Geográfica: aplicaciones para el análisis de clasificación espacial y cambios de usos del suelo. 1st Edition. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires: Impresiones Buenos Aires Editorial, 184.

INEGI. (2020). Marco Geoestadístico. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía . Available online at: https://www.inegi.org.mx/temas/mg/#Descargas

Inostroza, L., Baur, R., and Csaplovics, E. (2013). Urban sprawl and fragmentation in Latin America: a dynamic quantification and characterization of spatial patterns. J. Environ. Manag. 115, 87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.11.007

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jimenez, M., Pérez Belmont, P., Schewenius, M., Lerner, A. M., and Mazari-Hiriart, M. (2020). Assessing the historical adaptive cycles of an urban social-ecological system and its potential future resilience: the case of Xochimilco, Mexico City. Reg. Environ. Change 20, 7. doi: 10.1007/s10113-020-01587-9

Liu, F., Zhang, Z., and Wang, X. (2016). Forms of urban expansion of chinese municipalities and provincial capitals, 1970s−2013. Remote Sens. 8, 930. doi: 10.3390/rs8110930

Macgregor, S. D., and Thompson, D. (2006). “Contemporary perspectives on peri-urban zone of cities in developing areas,” in The Periurban Interface , eds. Macgregor, D., Simon, D., and Thompson, D., (London, Earthscan), 3–17.

Martínez Jimenez, E. T., Perez Campuzano, E., and Aguilar Ibarra, A. (2017). Hedonic pricing model for the economic valuation of conservation land in Mexico City. Trans. Ecol. Environ. 223, 101–111. doi: 10.2495/SC170091

McGranahan, G., and Satterthwaite, D. (2003). Urban centers: an assessment of sustainability. Ann. Rev. Environ. Resour. 28, 243–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev.energy.28.050302.105541

McGregor, D., Simon, D., and Thompson, D. (2006). The Peri-Urban Interface: Approaches to Sustainable Natural and Human Resource Use . London: Earthscan.

National Institute of Statistics Geography. (2001). Uso de Suelo y Vegetación, Serie III. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía . Available online at: https://www.inegi.org.mx/temas/usosuelo/#Descargas

Olivera, G. (2015). La Incorporación de Suelo Social al Crecimiento Urbano de Cuernavaca y sus Efectos en el Desarrollo Urbano Formal e Informal del Suelo y la Vivienda, in La Urbanización Social y Privada el Ejido , ed. Olivera, G., (Cuernavaca: Ensayos sobre la Dualidad del Desarrollo Urbano en México, CRIM_UNAM), 149–196.

Perevochtchikova, M., and Torruco Colorado, V. M. (2013). Análisis comparativo de dos instrumentos de conservación ambiental aplicados en el Suelo de Conservación del Distrito Federal, Sociedad y Ambiente . 1, 3–25 doi: 10.31840/sya.v0i3.994

Perez-Campuzano, E., Avila-Foucat, V. S., and Perevochtchikova, M. (2016). Environmental policies in the peri-urban area of Mexico City: the perceived effects of three environmental programs. Cities 50, 129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2015.08.013

Phadke, A. (2014). Mumbai metropolitan region: impact of recent urban change on the peri-urban areas of Mumbai, Urban Studies 51, 2466–2483. doi: 10.1177/0042098013493483

Pontius, R., Shusas, E., and McEchern, M. (2004). Detecting important categorical land changes while accounting for persistence. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 101, 251–268. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2003.09.008

Ravetz, J., Christian Fertner, C., and Nielsen, T. S. (2013). “The dynamics of peri-urbanization,” in Peri-urban Futures: Scenarios and Models for Land Use Change in Europe , eds. Nilsson, K., Pauleit, S., Bell, S., Aalbers, C., and Nielsen, T. S., (Berlin: Springer), 13–44.