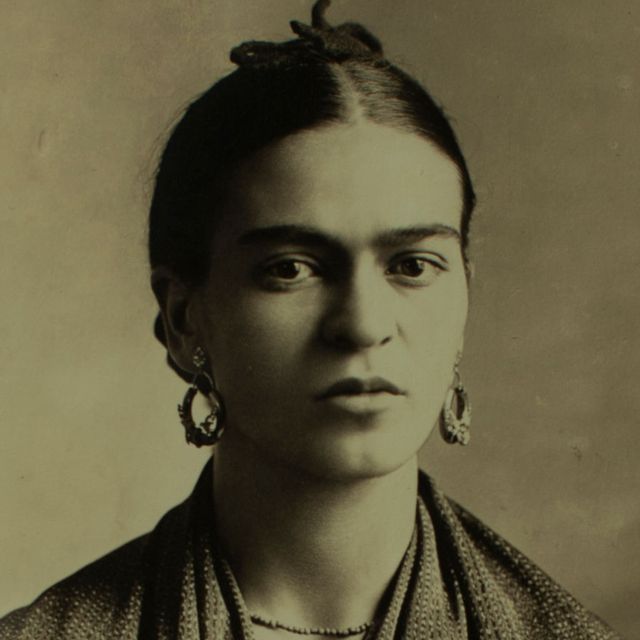

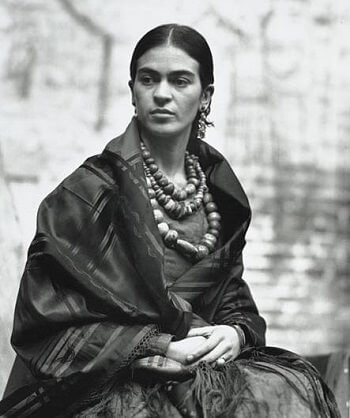

Frida Kahlo

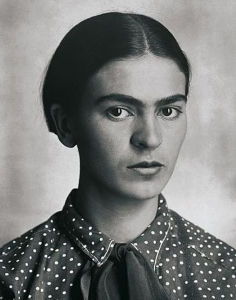

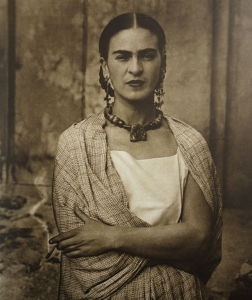

Painter Frida Kahlo was a Mexican artist who was married to Diego Rivera and is still admired as a feminist icon.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back.

(1907-1954)

Quick Facts:

Who was frida kahlo, family, education and early life, frida kahlo's accident, frida kahlo's marriage to diego rivera, artistic career, frida kahlo's most famous paintings, frida kahlo’s death, movie on frida kahlo, frida kahlo museum, book on frida kahlo.

FULL NAME: Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón BORN: JULY 6, 1907 BIRTHPLACE: Coyoacán, Mexico City, Mexico ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Cancer

Artist Frida Kahlo was considered one of Mexico's greatest artists who began painting mostly self-portraits after she was severely injured in a bus accident. Kahlo later became politically active and married fellow communist artist Diego Rivera in 1929. She exhibited her paintings in Paris and Mexico before her death in 1954.

Kahlo was born Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderón on July 6, 1907, in Coyoacán, Mexico City, Mexico.

Kahlo's father, Wilhelm (also called Guillermo), was a German photographer who had immigrated to Mexico where he met and married her mother Matilde. She had two older sisters, Matilde and Adriana, and her younger sister, Cristina, was born the year after Kahlo.

Around the age of six, Kahlo contracted polio, which caused her to be bedridden for nine months. While she recovered from the illness, she limped when she walked because the disease had damaged her right leg and foot. Her father encouraged her to play soccer, go swimming, and even wrestle — highly unusual moves for a girl at the time — to help aid in her recovery.

In 1922, Kahlo enrolled at the renowned National Preparatory School. She was one of the few female students to attend the school, and she became known for her jovial spirit and her love of colorful, traditional clothes and jewelry.

While at school, Kahlo hung out with a group of politically and intellectually like-minded students. Becoming more politically active, Kahlo joined the Young Communist League and the Mexican Communist Party.

On September 17, 1925, Kahlo and Alejandro Gómez Arias, a school friend with whom she was romantically involved, were traveling together on a bus when the vehicle collided with a streetcar . As a result of the collision, Kahlo was impaled by a steel handrail, which went into her hip and came out the other side. She suffered several serious injuries as a result, including fractures in her spine and pelvis.

After staying at the Red Cross Hospital in Mexico City for several weeks, Kahlo returned home to recuperate further. She began painting during her recovery and finished her first self-portrait the following year, which she gave to Gómez Arias.

In 1929, Kahlo and famed Mexican muralist Diego Rivera married. Kahlo and Rivera first met in 1922 when he went to work on a project at her high school. Kahlo often watched as Rivera created a mural called The Creation in the school’s lecture hall. According to some reports, she told a friend that she would someday have Rivera’s baby.

Kahlo reconnected with Rivera in 1928. He encouraged her artwork, and the two began a relationship. During their early years together, Kahlo often followed Rivera based on where the commissions that Rivera received were. In 1930, they lived in San Francisco, California. They then went to New York City for Rivera’s show at the Museum of Modern Art and later moved to Detroit for Rivera’s commission with the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Kahlo and Rivera’s time in New York City in 1933 was surrounded by controversy. Commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller , Rivera created a mural entitled Man at the Crossroads in the RCA Building at Rockefeller Center. Rockefeller halted the work on the project after Rivera included a portrait of communist leader Vladimir Lenin in the mural, which was later painted over. Months after this incident, the couple returned to Mexico and went to live in San Angel, Mexico.

Never a traditional union, Kahlo and Rivera kept separate, but adjoining homes and studios in San Angel. She was saddened by his many infidelities, including an affair with her sister Cristina. In response to this familial betrayal, Kahlo cut off most of her trademark long dark hair. Desperately wanting to have a child, she again experienced heartbreak when she miscarried in 1934.

Kahlo and Rivera went through periods of separation, but they joined together to help exiled Soviet communist Leon Trotsky and his wife Natalia in 1937. The Trotskys came to stay with them at the Blue House (Kahlo's childhood home) for a time in 1937 as Trotsky had received asylum in Mexico. Once a rival of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin , Trotsky feared that he would be assassinated by his old nemesis. Kahlo and Trotsky reportedly had a brief affair during this time.

Kahlo divorced Rivera in 1939. They did not stay divorced for long, remarrying in 1940. The couple continued to lead largely separate lives, both becoming involved with other people over the years .

While she never considered herself a surrealist, Kahlo befriended one of the primary figures in that artistic and literary movement, Andre Breton, in 1938. That same year, she had a major exhibition at a New York City gallery, selling about half of the 25 paintings shown there. Kahlo also received two commissions, including one from famed magazine editor Clare Boothe Luce, as a result of the show.

In 1939, Kahlo went to live in Paris for a time. There she exhibited some of her paintings and developed friendships with such artists as Marcel Duchamp and Pablo Picasso .

Kahlo received a commission from the Mexican government for five portraits of important Mexican women in 1941, but she was unable to finish the project. She lost her beloved father that year and continued to suffer from chronic health problems. Despite her personal challenges, her work continued to grow in popularity and was included in numerous group shows around this time.

In 1953, Kahlo received her first solo exhibition in Mexico. While bedridden at the time, Kahlo did not miss out on the exhibition’s opening. Arriving by ambulance, Kahlo spent the evening talking and celebrating with the event’s attendees from the comfort of a four-poster bed set up in the gallery just for her.

After Kahlo’s death, the feminist movement of the 1970s led to renewed interest in her life and work, as Kahlo was viewed by many as an icon of female creativity.

Many of Kahlo’s works were self-portraits. A few of her most notable paintings include:

'Frieda and Diego Rivera' (1931)

Kahlo showed this painting at the Sixth Annual Exhibition of the San Francisco Society of Women Artists, the city where she was living with Rivera at the time. In the work, painted two years after the couple married, Kahlo lightly holds Rivera’s hand as he grasps a palette and paintbrushes with the other — a stiffly formal pose hinting at the couple’s future tumultuous relationship. The work now lives at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

'Henry Ford Hospital' (1932)

In 1932, Kahlo incorporated graphic and surrealistic elements in her work. In this painting, a naked Kahlo appears on a hospital bed with several items — a fetus, a snail, a flower, a pelvis and others — floating around her and connected to her by red, veinlike strings. As with her earlier self-portraits, the work was deeply personal, telling the story of her second miscarriage.

'The Suicide of Dorothy Hale' (1939)

Kahlo was asked to paint a portrait of Luce and Kahlo's mutual friend, actress Dorothy Hale, who had committed suicide earlier that year by jumping from a high-rise building. The painting was intended as a gift for Hale's grieving mother. Rather than a traditional portrait, however, Kahlo painted the story of Hale's tragic leap. While the work has been heralded by critics, its patron was horrified at the finished painting.

'The Two Fridas' (1939)

One of Kahlo’s most famous works, the painting shows two versions of the artist sitting side by side, with both of their hearts exposed. One Frida is dressed nearly all in white and has a damaged heart and spots of blood on her clothing. The other wears bold colored clothing and has an intact heart. These figures are believed to represent “unloved” and “loved” versions of Kahlo.

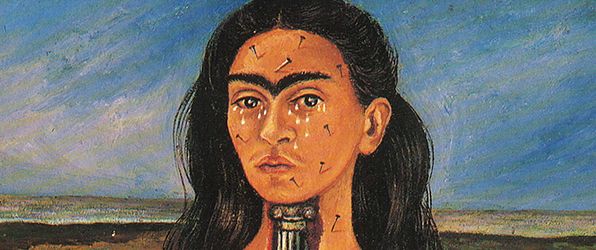

'The Broken Column' (1944)

Kahlo shared her physical challenges through her art again with this painting, which depicted a nearly nude Kahlo split down the middle, revealing her spine as a shattered decorative column. She also wears a surgical brace and her skin is studded with tacks or nails. Around this time, Kahlo had several surgeries and wore special corsets to try to fix her back. She would continue to seek a variety of treatments for her chronic physical pain with little success.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S FRIDA KAHLO FACT CARD

About a week after her 47th birthday, Kahlo died on July 13, 1954, at her beloved Blue House. There has been some speculation regarding the nature of her death. It was reported to be caused by a pulmonary embolism, but there have also been stories about a possible suicide.

Kahlo’s health issues became nearly all-consuming in 1950. After being diagnosed with gangrene in her right foot, Kahlo spent nine months in the hospital and had several operations during this time. She continued to paint and support political causes despite having limited mobility. In 1953, part of Kahlo’s right leg was amputated to stop the spread of gangrene.

Deeply depressed, Kahlo was hospitalized again in April 1954 because of poor health, or, as some reports indicated, a suicide attempt. She returned to the hospital two months later with bronchial pneumonia. No matter her physical condition, Kahlo did not let that stand in the way of her political activism. Her final public appearance was a demonstration against the U.S.-backed overthrow of President Jacobo Arbenz of Guatemala on July 2nd.

Kahlo’s life was the subject of a 2002 film entitled Frida , starring Salma Hayek as the artist and Alfred Molina as Rivera. Directed by Julie Taymor, the film was nominated for six Academy Awards and won for Best Makeup and Original Score.

The family home where Kahlo was born and grew up, later referred to as the Blue House or Casa Azul, was opened as a museum in 1958. Located in Coyoacán, Mexico City, the Museo Frida Kahlo houses artifacts from the artist along with important works including Viva la Vida (1954), Frida and Caesarean (1931) and Portrait of my father Wilhelm Kahlo (1952).

Hayden Herrera’s 1983 book on Kahlo, Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo , helped to stir up interest in the artist. The biographical work covers Kahlo’s childhood, accident, artistic career, marriage to Diego Rivera, association with the communist party and love affairs.

Watch the 2024 documentary, titled Frida , about the artist's life on Amazon Prime Video.

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

- I never paint dreams or nightmares. I paint my own reality.

- My painting carries with it the message of pain.

- I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.

- I think that, little by little, I'll be able to solve my problems and survive.

- The only thing I know is that I paint because I need to, and I paint whatever passes through my head without any other consideration.

- I was born a bitch. I was born a painter.

- I love you more than my own skin.

- I am not sick, I am broken, but I am happy as long as I can paint.

- Feet, what do I need you for when I have wings to fly?

- I tried to drown my sorrows, but the bastards learned how to swim, and now I am overwhelmed with this decent and good feeling.

- There have been two great accidents in my life. One was the trolley and the other was Diego. Diego was by far the worst.

- I hope the end is joyful, and I hope never to return.

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Famous Painters

Jean-Michel Basquiat

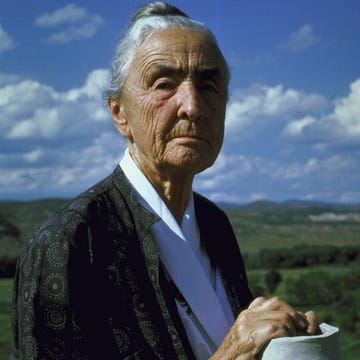

Georgia O'Keeffe

11 Notable Artists from the Harlem Renaissance

Fernando Botero

Gustav Klimt

The Surreal Romance of Salvador and Gala Dalí

Salvador Dalí

Margaret Keane

Frida Kahlo biography

Considered one of Mexico's greatest artists, Frida Kahlo was born on July 6, 1907 in Coyocoan, Mexico City, Mexico. She grew up in the family's home where was later referred to as the Blue House or Casa Azul. Her father is a German descendant and photographer. He immigrated to Mexico where he met and married her mother Matilde. Her mother is half Amerindian and half Spanish. Frida Kahlo has two older sisters and one younger sister.

Frida Kahlo has poor health in her childhood. She contracted polio at the age of 6 and had to be bedridden for nine months. This disease caused her right leg and foot to grow much thinner than her left one. She limped after she recovered from polio. She has been wearing long skirts to cover that for the rest of her life. Her father encouraged her to do lots of sports to help her recover. She played soccer, went swimming, and even did wrestle, which is very unusual at that time for a girl. She has kept a very close relationship with her father for her whole life.

Frida Kahlo attended the renowned National Preparatory School in Mexico City in the year of 1922. There are only thirty-five female students enrolled in that school and she soon became famous for her outspokenness and bravery. At this school she first met the famous Mexican muralist Diego Rivera for the first time. Rivera at that time was working on a mural called The Creation on the school campus. Frida often watched it and she told a friend she will marry him someday.

In the same year, Kahlo joined a gang of students who shared similar political and intellectual views. She fell in love with the leader Alejandro Gomez Arias. On a September afternoon when she traveled with Gomez Arias on a bus the tragic accident happened. The bus collided with a streetcar and Frida Kahlo was seriously injured. A steel handrail impaled her through the hip. Her spine and pelvis are fractured and this accident left her in a great deal of pain, both physically and physiologically.

She was injured so badly and had to stay in the Red Cross Hospital in Mexico City for several weeks. After that, she returned home for further recovery. She had to wear full-body cast for three months. To kill the time and alleviate the pain, she started painting and finished her first self-portrait the following year. Frida Kahlo once said,

I paint myself because I am often alone and I am the subject I know best".

Her parents encouraged her to paint and made a special easel made for her so she could paint in bed. They also gave her brushes and boxes of paints.

Frida Kahlo reconnected with Rivera in 1928. She asked him to evaluate her work and he encouraged her. The two soon started the romantic relationship. Despite her mother's objection, Frida and Diego Rivera got married in the next year. During their earlier years as a married couple, Frida had to move a lot based on Diego's work. In 1930, they lived in San Francisco, California. Then they moved to New York City for Rivera's artwork show at Museum of Modern Art . They later moved to Detroit while Diego Rivera worked for Detroit Institute of Arts .

In 1932, Kahlo added more realistic and surrealistic components in her painting style. In the painting titled Henry Ford Hospital(1932) , Frida Kahlo lied on a hospital bed naked and was surrounded with a few things floating around, which includes a fetus, a flower, a pelvis, a snail, all connected by veins. This painting was an expression of her feelings about her second miscarriage. It is as personal as her other self-portraits.

In 1933, Kahlo was living in New York City with her husband Diego Rivera. Rivera was commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller to create a mural named as Man at the Crossroads at Rockefeller Center. Rivera tried to include Vladimir Lenin in the painting, who is a communist leader. Rockefeller stopped his work and that part was painted over. The couple had to move back to Mexico after this incident. They returned and live in San Angel, Mexico.

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera's marriage is not a usual one. They had been keeping separate homes and studios for all those years. Diego had so many affairs and one of that was with Kahlo's sister Cristina. Frida Kahlo was so sad and she cut off her long hair to show her desperation to the betrayal. She has longed for children but she cannot bear one due to the bus accident. She was heartbroken when she experienced a second miscarriage in 1934. Kahlo and Rivera have been separated a few times but they always went back together. In 1937 they helped Leon Trotsky and his wife Natalia. Leon Trotsky is an exiled communist and rival of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. Kahlo and Rivera welcomed the couple together and let them stay at her Blue House. Kahlo also had a brief affair with Leon Trotsky when the couple stayed at her house.

In 1938, Frida Kahlo became a friend of André Breton, who is one of the primary figures of the Surrealism movement. Frida said she never considered herself as a Surrealist "until André Breton came to Mexico and told me I was one." She also wrote, "Really I do not know whether my paintings are surrealist or not, but I do know that they are the frankest expression of myself". "Since my subjects have always been my sensations, my states of mind and the profound reactions that life has been producing in me, I have frequently objectified all this in figures of myself, which were the most sincere and real thing that I could do in order to express what I felt inside and outside of myself."

In the same year, she had an exhibition at New York City gallery. She sold some of her paintings and got two commissions. One of that is from Clare Boothe Luce to paint her friend Dorothy Hale who committed suicide. She painted The Suicide of Dorothy Hale (1939), which tells the story of Dorothy's tragic leap. The patron Luce was horrified and almost destroyed this painting.

The next year, 1939, Kahlo was invited by André Breton and went to Paris. Her works are exhibited there and she is befriended with artists such as Marc Chagall , Piet Mondrian , and Pablo Picasso . She and Rivera got divorced that year and she painted one of her most famous paintings, The Two Fridas (1939).

But soon Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera remarried in 1940. The second marriage is about the same as the first one. They still keep separate lives and houses. Both of them had infidelities with other people during the marriage. Kahlo received a commission from the Mexican government for five portraits of important Mexican women in 1941, but she was unable to finish the project. She lost her beloved father that year and continued to suffer from chronic health problems. Despite her personal challenges, her work continued to grow in popularity and was included in numerous group shows around this time.

In the year of 1944, Frida Kahlo painted one of her most famous portraits, The Broken Column . In this painting, she depicted herself naked and split down the middle. Her spine is shattered like a column. She wears a surgical brace and there are nails all through her body, which is the indication of the consistent pain she went through. In this painting, Frida expressed her physical challenges through her art. During that time, she had a few surgeries and had to wear special corsets to protect her back spine. She seeks lots of medical treatment for her chronic pain but nothing really worked.

Her health condition has been worsening in 1950. That year she was diagnosed with gangrene in her right foot. She became bedridden for the next nine month and had to stay in hospital and had several surgeries. But with great persistence, Frida Kahlo continued to work and paint. In the year of 1953, she had a solo exhibition in Mexican. Although she had limited mobility at that time, she showed up on the exhibition's opening ceremony. She arrived by ambulance, and welcomed the attendees, celebrated the ceremony in a bed the gallery set up for her. A few months later, she had to accept another surgery. Part of her right leg got amputated to stop the gangrene.

With the poor physical condition, she is also deeply depressed. She even had an inclination for suicide. Frida Kahlo has been out and in hospital during that year. But despite her health issues, she has been active with the political movement. She showed up at the demonstration against US-backed overthrow of President Jacobo Arbenz of Guatemala on July 2. This is her last public appearance. About one week after her 47th birthday, Frida Kahlo passed away at her beloved Bule House. She was publicly reported to die of a pulmonary embolism, but there is speculation which was saying she died of a possible suicide.

Frida Kahlo's fame has been growing after her death. Her Blue House was opened as a museum in the year of 1958. In the 1970s the interest in her work and life is renewed due to the feminist movement since she was viewed as an icon of female creativity. In 1983, Hayden Herrera published his book on her, A Biography of Frida Kahlo , which drew more attention from the public to this great artist. In the year of 2002, a movie named Frida was released, staring alma Hayek as Frida Kahlo and Alfred Molina as Diego Rivera. This movie was nominated for six Academy Awards and won for Best Makeup and Original Score.

The Two Fridas

Self-portrait with thorn necklace & hummingbird, viva la vida, watermelons, the wounded deer, self portrait with monkeys, without hope, me and my parrots, what the water gave me, frida and diego rivera, the wounded table, diego and i, my dress hangs there, my grandparents, my parents, and me, self portrait as a tehuana, fulang chang and i.

Frida Kahlo

Mexican Painter

Summary of Frida Kahlo

Small pins pierce Kahlo's skin to reveal that she still 'hurts' following illness and accident, whilst a signature tear signifies her ongoing battle with the related psychological overflow. Frida Kahlo typically uses the visual symbolism of physical pain in a long-standing attempt to better understand emotional suffering. Prior to Kahlo's efforts, the language of loss, death, and selfhood, had been relatively well investigated by some male artists (including Albrecht Dürer , Francisco Goya , and Edvard Munch ), but had not yet been significantly dissected by a woman. Indeed not only did Kahlo enter into an existing language, but she also expanded it and made it her own. By literally exposing interior organs, and depicting her own body in a bleeding and broken state, Kahlo opened up our insides to help explain human behaviors on the outside. She gathered together motifs that would repeat throughout her career, including ribbons, hair, and personal animals, and in turn created a new and articulate means to discuss the most complex aspects of female identity. As not only a 'great artist' but also a figure worthy of our devotion, Kahlo's iconic face provides everlasting trauma support and she has influence that cannot be underestimated.

Accomplishments

- Kahlo made it legitimate for women to outwardly display their pains and frustrations and to thus make steps towards understanding them. It became crucial for women artists to have a female role model and this is the gift of Frida Kahlo.

- As an important question for many Surrealists , Kahlo too considers: What is Woman? Following repeated miscarriages, she asks: to what extent does motherhood or its absence impact on female identity? She irreversibly alters the meaning of maternal subjectivity. It becomes clear through umbilical symbolism (often shown by ribbons) that Kahlo is connected to all that surrounds her, and that she is a 'mother' without children.

- Finding herself often alone, she worked obsessively with self-portraiture. Her reflection fueled an unflinching interest in identity. She was particularly interested in her mixed German-Mexican ancestry, as well as in her divided roles as artist, lover, and wife.

- Kahlo uses religious symbolism throughout her oeuvre . She appears as the Madonna holding her 'animal babies', and becomes the Virgin Mary as she cradles her husband and famous national painter Diego Rivera . She identifies with Saint Sebastian, and even fittingly appears as the martyred Christ. She positions herself as a prophet when she takes to the head of the table in her Last Supper -style painting, and her depiction of the accident which left her impaled on a metal bar (and covered in gold dust when lying injured) recalls the crucifixion and suggests her own holiness.

- Women prior to Kahlo who had attempted to communicate the wildest and deepest of emotions were often labeled hysterical or condemned insane - while men were aligned with the 'melancholy' character type. By remaining artistically active under the weight of sadness, Kahlo revealed that women too can be melancholy rather than depressed, and that these terms should not be thought of as gendered.

The Life of Frida Kahlo

"I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone... because I am the subject I know best." From battles with her mind and her body, Kahlo lived through her art.

Important Art by Frida Kahlo

Frieda and Diego Rivera

It is as if in this painting Kahlo tries on the role of wife to see how it fits. She does not focus on her identity as a painter, but instead adopts a passive and supportive role, holding the hand of her talented and acclaimed husband. It was indeed the case that during the majority of her painting career, Kahlo was viewed only in Rivera's shadow and it was not until later in life that she gained international recognition. This early double-portrait was painted primarily to mark the celebration of Kahlo's marriage to Rivera. Whilst Rivera holds a palette and paint brushes, symbolic of his artistic mastery, Kahlo limits her role to his wife by presenting herself slight in frame and without her artistic accoutrements. Kahlo furthermore dresses in costume typical of the Mexican woman, or "La Mexicana," wearing a traditional red shawl known as the rebozo and jade Aztec beads. The positioning of the figures echoes that of traditional marital portraiture where the wife is placed on her husband's left to indicate her lesser moral status as a woman. In a drawing made the following year called Frida and the Miscarriage , the artist does hold her own palette, as though the experience of losing a fetus and not being able to create a baby shifts her determination wholly to the creation of art.

Oil on canvas - San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Henry Ford Hospital

Many of Kahlo's paintings from the early 1930s, especially in size, format, architectural setting and spatial arrangement, relate to religious ex-voto paintings of which she and Rivera possessed a large collection ranging in date over several centuries. Ex-votos are made as a gesture of gratitude for salvation, a granted prayer or disaster averted and left in churches or at shrines. Ex-votos are generally painted on small-scale metal panels and depict the incident along with the Virgin or saint to whom they are offered. Henry Ford Hospital , is a good example where the artist uses the ex-voto format but subverts it by placing herself centre stage, rather than recording the miraculous deeds of saints. Kahlo instead paints her own story, as though she becomes saintly and the work is made not as thanks to the lord but in defiance, questioning why he brings her pain. In this painting, Kahlo lies on a bed, bleeding after a miscarriage. From the exposed naked body six vein-like ribbons flow outwards, attached to symbols. One of these six objects is a fetus, suggesting that the ribbons could be a metaphor for umbilical cords. The other five objects that surround Frida are things that she remembers, or things that she had seen in the hospital. For example, the snail makes reference to the time it took for the miscarriage to be over, whilst the flower was an actual physical object given to her by Diego. The artist demonstrates her need to be attached to all that surrounds her: to the mundane and metaphorical as much as the physical and actual. Perhaps it is through this reaching out of connectivity that the artist tries to be 'maternal', even though she is not able to have her own child.

Oil on canvas - Dolores Olmedo Collection, Mexico City, Mexico

This is a haunting painting in which both the birth giver and the birthed child seem dead. The head of the woman giving birth is shrouded in white cloth while the baby emerging from the womb appears lifeless. At the time that Kahlo painted this work, her mother had just died so it seems reasonable to assume that the shrouded funerary figure is her mother while the baby is Kahlo herself (the title supports this reading). However, Kahlo had also just lost her own child and has said that she is the covered mother figure. The Virgin of Sorrows , who hangs above the bed suggests that this is an image that overflows with maternal pain and suffering. Also though, and revealingly, Kahlo wrote in her diary, next to several small drawings of herself, 'the one who gave birth to herself ... who wrote the most wonderful poem of her life.' Similar to the drawing, Frida and the Miscarriage , My Birth represents Kahlo mourning for the loss of a child, but also finding the strength to make powerful art because of such trauma. The painting is made in a retablo (or votive) style (a small traditional Mexican painting derived from Catholic Church art) in which thanks would typically be given to the Madonna beneath the image. Kahlo instead leaves this section blank, as though she finds herself unable to give thanks either for her own birth, or for the fact that she is now unable to give birth. The painting seems to bring the message that it is important to acknowledge that birth and death live very closely together. Many believe that My Birth was heavily inspired by an Aztec sculpture that Kahlo had at home representing Tiazolteotl, the Goddess of fertility and midwives.

Oil and tempera on zinc - Private Collection

My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (Family Tree)

This dream-like family tree was painted on zinc rather than canvas, a choice that further highlights the artist's fascination with and collection of 18 th -century and 19 th -century Mexican retablos. Kahlo completed this work to accentuate both her European Jewish heritage and her Mexican background. Her paternal side, German Jewish, occupies the right side of the composition symbolized by the sea (acknowledging her father's voyage to get to Mexico), while her maternal side of Mexican descent is represented on the left by a map faintly outlining the topography of Mexico. While Kahlo's paintings are assertively autobiographical, she often used them to communicate transgressive or political messages: this painting was completed shortly after Adolf Hitler passed the Nuremberg laws banning interracial marriage. Here, Kahlo simultaneously affirms her mixed heritage to confront Nazi ideology, using a format - the genealogical chart - employed by the Nazi party to determine racial purity. Beyond politics, the red ribbon used to link the family members echoes the umbilical cord that connects baby Kahlo to her mother - a motif that recurs throughout Kahlo's oeuvre .

Oil and tempera on zinc - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Fulang-Chang and I

This painting debuted at Kahlo's exhibition in Julien Levy's New York gallery in 1938, and was one of the works that most fascinated André Breton, the founder of Surrealism. The canvas in the New York show is a self-portrait of the artist and her spider monkey, Fulang-Chang, a symbol employed as a surrogate for the children that she and Rivera could not have. The arrangement of figures in the portrait signals the artist's interest in Renaissance paintings of the Madonna and child. After the New York exhibition, a second frame containing a mirror was added. The later inclusion of the mirror is a gesture inviting the viewer into the work: it was through looking at herself intensely in a mirror in her months spent at home after her bus accident that Kahlo first began painting portraits and delving deeper into her psyche. The inclusion of the mirror, considered from this perspective, is a remarkably intimate vision into both the artist's aesthetic process and into her personal introspection. In many of Kahlo's self-portraits, she is accompanied by monkeys, dogs, and parrots, all of which she kept as pets. Since the Middle Ages, small spider monkeys, like those kept by Kahlo, have been said to symbolize the devil, heresy, and paganism, finally coming to represent the fall of man, vice, and the embodiment of lust. These monkeys were depicted in the past as a cautionary symbol against the dangers of excessive love and the base instincts of man. Kahlo again depicts herself with her monkey in both 1939 and 1940. In a later version in 1945, Kahlo paints her monkey and also her dog, Xolotl. This little dog that often accompanies the artist, is named after a mythological Aztec god, known to represent lightning and death, and also to be the twin of Quetzalcoatl, both of who had visited the underworld. All of these pictures, including Fulang-Chang and I include 'umbilical' ribbons that wrap between Kahlo's and the animal's necks. Kahlo is the Madonna and her pets become the holy (yet darkly symbolic) infant for which she longs.

In two parts, oil on composition board (1937) with painted mirror frame (added after 1939) - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

What the Water Gave Me

In this painting most of Kahlo's body is obscured from view. We are unusually confronted with the foot and plug end of the bath, and with focus placed on the artist's feet. Furthermore, Kahlo adopts a birds-eye view and looks down on the water from above. Within the water, Kahlo paints an alternative self-portrait, one in which the more traditional facial portrait has been replaced by an array of symbols and recurring motifs. The artist includes portraits of her parents, a traditional Tehuana dress, a perforated shell, a dead humming bird, two female lovers, a skeleton, a crumbling skyscraper, a ship set sail, and a woman drowning. This painting was featured in Breton's 1938 book on Surrealism and Painting and Hayden Herrera, in her biography of Kahlo, mentions that the artist herself considered this work to have a special importance. Recalling the tapestry style painting of Northern Renaissance masters, Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder, the figures and objects floating in the water of Kahlo's painting create an at once fantastic and real landscape of memory. Kahlo discussed What the Water Gave Me with the Manhattan gallery owner Julien Levy, and suggested that it was a sad piece that mourned the loss of her childhood. Perhaps the strangled figure at the centre is representative of the inner emotional torments experienced by Kahlo herself. It is clear from the conversation that the artist had with Levy, that Kahlo was aware of the philosophical implications of her work. In an interview with Herrera, Levy recalls, in 'a long philosophical discourse, Kahlo talked about the perspective of herself that is shown in this painting'. He further relays that 'her idea was about the image of yourself that you have because you do not see your head. The head is something that is looking, but is not seen. It is what one carries around to look at life with.' The artist's head in What the Water Gave Me is thus appropriately replaced by the interior thoughts that occupy her mind. As well as an inclusion of death by strangulation in the centre of the water, there is also a labia-like flower and a cluster of pubic hair painted between Kahlo's legs. The work is quite sexual while also showing preoccupation with destruction and death. The motif of the bathtub in art is one that has been popular since Jacques-Louis David's The Death of Marat (1793), and was later taken up many different personalities such as Francesca Woodman and Tracey Emin.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

The Two Fridas

This double self-portrait is one of Kahlo's most recognized compositions, and is symbolic of the artist's emotional pain experienced during her divorce from Rivera. On the left, the artist is shown in modern European attire, wearing the costume from her marriage to Rivera. Throughout their marriage, given Rivera's strong nationalism, Kahlo became increasingly interested in indigenism and began to explore traditional Mexican costume, which she wears in the portrait on the right. It is the Mexican Kahlo that holds a locket with an image of Rivera. The stormy sky in the background, and the artist's bleeding heart - a fundamental symbol of Catholicism and also symbolic of Aztec ritual sacrifice - accentuate Kahlo's personal tribulation and physical pain. Symbolic elements frequently possess multiple layers of meaning in Kahlo's pictures; the recurrent theme of blood represents both metaphysical and physical suffering, gesturing also to the artist's ambivalent attitude toward accepted notions of womanhood and fertility. Although both women have their hearts exposed, the woman in the white European outfit also seems to have had her heart dissected and the artery that runs from this heart is cut and bleeding. The artery that runs from the heart of her Tehuana-costumed self remains intact because it is connected to the miniature photograph of Diego as a child. Whereas Kahlo's heart in the Mexican dress remains sustained, the European Kahlo, disconnected from her beloved Diego, bleeds profusely onto her dress. As well as being one of the artist's most famous works, this is also her largest canvas.

Oil on canvas - Museum of Modern Art, Mexico City, Mexico

Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair

This self-portrait shows Kahlo as an androgynous figure. Scholars have seen this gesture as a confrontational response to Rivera's demand for a divorce, revealing the artist's injured sense of female pride and her self-punishment for the failures of her marriage. Her masculine attire also reminds the viewer of early family photographs in which Kahlo chose to wear a suit. The cropped hair also presents a nuanced expression of the artist's identity. She holds one cut braid in her left hand while many strands of hair lie scattered on the floor. The act of cutting a braid symbolizes a rejection of girlhood and innocence, but equally can be seen as the severance of a connective cord (maybe umbilical) that binds two people or two ways of life. Either way, braids were a central element in Kahlo's identity as the traditional La Mexicana , and in the act of cutting off her braids, she rejects some aspect of her former identity. The hair strewn about the floor echoes an earlier self-portrait painted as the Mexican folkloric figure La Llorona , here ridding herself of these female attributes. Kahlo clutches a pair of scissors, as the discarded strands of hair become animated around her feet; the tresses appear to have a life of their own as they curl across the floor and around the legs of her chair. Above her sorrowful scene, Kahlo inscribed the lyrics and music of a song that declares cruelly, "Look, if I loved you it was for your hair, now that you are hairless, I don't love you anymore," confirming Kahlo's own denunciation and rejection of her female roles. In likely homage to Kahlo's painting, Finnish photographer Elina Brotherus photographed Wedding Portraits in 1997. On the occasion of her marriage, Brotherus cuts her hair, the remains of which her new husband holds in his hands. The act of cutting one's hair symbolic of a moment of change happens in the work of other female artists too, including that of Francesca Woodman and Rebecca Horn.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Self-portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird

The frontal position and outward stare of Kahlo in this self-portrait directly confronts and engages the viewer. The artist wears Christ's unraveled crown of thorns as a necklace that digs into her neck, signifying her self-representation as a Christian martyr and the enduring pain experienced following her failed marriage. A dead hummingbird, a symbol in Mexican folkloric tradition of luck charms for falling in love, hangs in the center of her necklace. A black cat - symbolic of bad luck and death - crouches behind her left shoulder, and a spider monkey gifted from Rivera, symbolic of evil, is included to her right. Kahlo frequently employed flora and fauna in the background of her bust-length portraits to create a tight, claustrophobic space, using the symbolic element of nature to simultaneously compare and contrast the link between female fertility with the barren and deathly imagery of the foreground. Typically a symbol of good fortune, the meaning of a 'dead' hummingbird is to be reversed. Kahlo, who craves flight, is perturbed and disturbed by the fact that the butterflies in her hair are too delicate to travel far and that the dead bird around her neck, has become an anchor, preyed upon by the nearby cat. In failing to directly translate complex inner feelings it as though the painting illustrates the artist's frustrations.

Oil on canvas on masonite - Nikolas Muray Collection, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

The Broken Column

The Broken Column is a particularly pertinent example of the combination of Kahlo's emotional and physical pain. The artist's biographer, Hayden Herrera, writes of this painting, 'A gap resembling an earthquake fissure splits her in two. The opened body suggests surgery and Frida's feeling that without the steel corset she would literally fall apart'. A broken ionic column replaces the artist's crumbling spine and sharp metal nails pierce her body. The hard coldness of this inserted column recalls the steel rod that pierced the artist's abdomen and uterus during her streetcar accident. More generally, the architectural feature now in ruins, has associations of the simultaneous power and fragility of the female body. Beyond its physical dimensions, the cloth wrapped around Kahlo's pelvis, recalls Christ's loincloth. Indeed, Kahlo again displays her wounds like a Christian martyr; through identification with Saint Sebastian, she uses physical pain, nakedness, and sexuality to bring home the message of spiritual suffering. Tears dot the artist's face as they do many depictions of the Madonna in Mexico; her eyes stare out beyond the painting as though renouncing the flesh and summoning the spirit. It is as a result of depictions like this one that Kahlo is now considered a Magic Realist. Her eyes are never-changing, realistic, while the rest of the painting is highly fantastical. The painting is not overly concerned with the workings of the subconscious or with irrational juxtapositions that feature more typically in Surrealist works. The Magic Realism movement was extremely popular in Latin America (especially with writers such as Gabriel García Márquez), and Kahlo has been retrospectively included in it by art historians. The notion of being wounded in the way that we see illustrated in The Broken Column , is referred to in Spanish as chingada . This word embodies numerous interrelated meanings and concepts, which include to be wounded, broken, torn open or deceived. The word derives from the verb for penetration and implies domination of the female by the male. It refers to the status of victimhood. The painting also likely inspired a performance and sculptural piece made by Rebecca Horn in 1970 called Unicorn . In the piece Horn walks naked through an arable field with her body strapped in a fabric corset that appears almost identical to that worn by Kahlo in The Broken Column . In the piece by the German performance artist, however, the erect, sky-reaching pillar is fixed to her head rather than inserted into her chest. The performance has an air of mythology and religiosity similar to that of Kahlo's painting, but the column is whole and strong again, perhaps paying homage to Kahlo's fortitude and artistic triumph.

Oil on masonite - Dolores Olmedo Collection, Mexico City, Mexico

The Wounded Deer

The 1946 painting, The Wounded Deer , further extends both the notion of chingada and the Saint Sebastian motif already explored in The Broken Column . As a hybrid between a deer and a woman, the innocent Kahlo is wounded and bleeding, preyed upon and hunted down in a clearing in the forest. Staring directly at the viewer, the artist confirms that she is alive, and yet the arrows will slowly kill her. The artist wears a pearl earring, as though highlighting the tension that she feels between her social existence and the desire to exist more freely alongside nature. Kahlo does not portray herself as a delicate and gentle fawn; she is instead a full-bodied stag with large antlers and drooping testicles. Not only does this suggest, like her suited appearance in early family photographs, that Kahlo is interested in combining the sexes to create an androgyne, but also shows that she attempted to align herself with the other great artists of the past, most of whom had been men. The branch beneath the stag's feet is reminiscent of the palm branches that onlookers laid under the feet of Jesus as he arrived in Jerusalem. Kahlo continued to identify with the religious figure of Saint Sebastian from this point until her death. In 1953, she completed a drawing of herself in which eleven arrows pierce her skin. Similarly, the artist Louise Bourgeois, also interested in the visualization of pain, used Saint Sebastian as a recurring symbol in her art. She first depicted the motif in 1947 as an abstracted series of forms, barely distinguishable as a human figure; drawn using watercolor and pencil on pink paper, but then later made obvious pink fabric sculptures of the saint, stuck with arrows, she like Kahlo feeling under attack and afraid.

Oil on masonite - Private Collection

Weeping Coconuts (Cocos gimientes)

This still life is exemplary of Kahlo's late work. More frequently associated with her psychological portraiture, Kahlo in fact painted still lifes throughout her career. She depicted fresh fruit and vegetable produce and objects native to Mexico, painting many small-scale still lifes, especially as she grew progressively ill. The anthropomorphism of the fruit in this composition is symbolic of Kahlo's projection of pain into all things as her health deteriorated at the end of her life. In contrast with the tradition of the cornucopia signifying plentiful and fruitful life, here the coconuts are literally weeping, alluding to the dualism of life and death. A small Mexican flag bearing the affectionate and personal inscription "Painted with all the love. Frida Kahlo" is stuck into a prickly pear, signaling Kahlo's use of the fruit as an emblem of personal expression, and communicating her deep respect for all of nature's gifts. During this period, the artist was heavily reliant on drugs and alcohol to alleviate her pain, so albeit beautiful, her still lifes became progressively less detailed between 1951 and 1953.

Oil on board - Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Biography of Frida Kahlo

Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo Calderon was born at La Casa Azul (The Blue House) in Coyoacan, a town on the outskirts of Mexico City in 1907. Her father, Wilhelm Kahlo, was German, and had moved to Mexico at a young age where he remained for the rest of his life, eventually taking over the photography business of Kahlo's mother's family. Kahlo's mother, Matilde Calderon y Gonzalez, was of mixed Spanish and indigenous ancestry, and raised Frida and her three sisters in a strict and religious household (Frida also had two half sisters from her father's first marriage who were raised in a convent). La Casa Azul was not only Kahlo's childhood home, but also the place that she returned to live and work from 1939 until her death. It later opened as the Frida Kahlo Museum.

Aside from her mother's rigidity, religious fanaticism, and tendency toward outbursts, several other events in Kahlo's childhood affected her deeply. At age six, Kahlo contracted polio; a long recovery isolated her from other children and permanently damaged one of her legs, causing her to walk with a limp after recovery. Wilhelm, with whom Kahlo was very close, and particularly so after the experience of being an invalid, enrolled his daughter at the German College in Mexico City and introduced Kahlo to the writings of European philosophers such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, and Arthur Schopenhauer. All of Kahlo's sisters instead attended a convent school so it seems that there was a thirst for expansive learning noted in Frida that resulted in her father making different decisions especially for her. Kahlo was grateful for this and despite a strained relationship with her mother, always credited her father with great tenderness and insight. Still, she was interested in both strands of her roots, and her mixed European and Mexican heritage provided life-long fascination in her approach towards both life and art.

Kahlo had a horrible experience at the German School where she was sexually abused and thus forced to leave. Luckily at the time, the Mexican Revolution and the Minister of Education had changed the education policy, and from 1922 girls were admitted to the National Preparatory School. Kahlo was one of the first 35 girls admitted and she began to study medicine, botany, and the social sciences. She excelled academically, became very interested in Mexican culture, and also became active politically.

Early Training

When Kahlo was 15, Diego Rivera (already a renowned artist) was painting the Creation mural (1922) in the amphitheater of her Preparatory School. Upon seeing him work, Kahlo experienced a moment of infatuation and fascination that she would go on to fully explore later in life. Meanwhile she enjoyed helping her father in his photography studio and received drawing instruction from her father's friend, Fernando Fernandez - for whom she was an apprentice engraver. At this time Kahlo also befriended a dissident group of students known as the "Cachuchas", who confirmed the young artist's rebellious spirit and further encouraged her interest in literature and politics. In 1923 Kahlo fell in love with a fellow member of the group, Alejandro Gomez Arias, and the two remained romantically involved until 1928. Sadly, in 1925 together with Alejandro (who survived unharmed) on their way home from school, Kahlo was involved in a near-fatal bus accident.

Kahlo suffered multiple fractures throughout her body, including a crushed pelvis, and a metal rod impaled her womb. She spent one month in the hospital immobile, and bound in a plaster corset, and following this period, many more months bedridden at home. During her long recovery she began to experiment in small-scale autobiographical portraiture, henceforth abandoning her medical pursuits due to practical circumstances and turning her focus to art.

During the months of convalescence at home Kahlo's parents made her a special easel, gave her a set of paints, and placed a mirror above her head so that she could see her own reflection and make self-portraits. Kahlo spent hours confronting existential questions raised by her trauma including a feeling of dissociation from her identity, a growing interiority, and a general closeness to death. She drew upon the acute pictorial realism known from her father's photographic portraits (which she greatly admired) and approached her own early portraits (mostly of herself, her sisters, and her school friends) with the same psychological intensity. At the time, Kahlo seriously considered becoming a medical illustrator during this period as she saw this as a way to marry her interests in science and art.

By 1927, Kahlo was well enough to leave her bedroom and thus re-kindled her relationship with the Cachuchas group, which was by this point all the more political. She joined the Mexican Communist Party (PCM) and began to familiarize herself with the artistic and political circles in Mexico City. She became close friends with the photojournalist Tina Modotti and Cuban revolutionary Julio Antonio Mella. It was in June 1928, at one of Modotti's many parties, that Kahlo was personally introduced to Diego Rivera who was already one of Mexico's most famous artists and a highly influential member of the PCM. Soon after, Kahlo boldly asked him to decide, upon looking at one of her portraits, if her work was worthy of pursuing a career as an artist. He was utterly impressed by the honesty and originality of her painting and assured her of her talents. Despite the fact that Rivera had already been married twice, and was known to have an insatiable fondness for women, the two quickly began a romantic relationship and were married in 1929. According to Kahlo's mother, who outwardly expressed her dissatisfaction with the match, the couple were 'the elephant and the dove'. Her father however, unconditionally supported his daughter and was happy to know that Rivera had the financial means to help with Kahlo's medical bills. The new couple moved to Cuernavaca in the rural state of Morelos where Kahlo devoted herself entirely to painting.

Mature Period

By the early 1930s, Kahlo's painting had evolved to include a more assertive sense of Mexican identity, a facet of her artwork that had stemmed from her exposure to the modernist indigenist movement in Mexico and from her interest in preserving the revival of Mexicanidad during the rise of fascism in Europe. Kahlo's interest in distancing herself from her German roots is evidenced in her name change from Frieda to Frida, and furthermore in her decision to wear traditional Tehuana costume (the dress from earlier matriarchal times). At the time, two failed pregnancies augmented Kahlo's simultaneously harsh and beautiful representation of the specifically female experience through symbolism and autobiography.

During the first few years of the 1930s Kahlo and Rivera lived in San Francisco, Detroit, and New York whilst Rivera was creating various murals. Kahlo also completed some seminal works including Frieda and Diego Rivera (1931) and Self-Portrait on the Borderline between Mexico and The United States (1932) with the latter expressing her observations of rivalry taking place between nature and industry in the two lands. It was during this time that Kahlo met and became friends with Imogen Cunningham , Ansel Adams , and Edward Weston . She also met Dr. Leo Eloesser while in San Francisco, the surgeon who would become her closest medical advisor until her death.

Soon after the unveiling of a large and controversial mural that Rivera had made for the Rockefeller Centre in New York (1933), the couple returned to Mexico as Kahlo was feeling particularly homesick. They moved into a new house in the wealthy neighborhood of San Angel. The house was made up of two separate parts joined by a bridge. This set up was appropriate as their relationship was undergoing immense strain. Kahlo had numerous health issues while Rivera, although he had been previously unfaithful, at this time had an affair with Kahlo's younger sister Cristina which understandably hurt Kahlo more than her husband's other infidelities. Kahlo too started to have her own extramarital affairs at this point. Not long after returning to Mexico from the States, she met the Hungarian photographer Nickolas Muray, who was on holiday in Mexico. The two began an on-and-off romantic affair that lasted 10 years, and it is Muray who is credited as the man who captured Kahlo most colorfully on camera.

While briefly separated from Diego following the affair with her sister and living in her own flat away from San Angel, Kahlo also had a short affair with the Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi . The two highly politically and socially conscious artists remained friends until Kahlo's death.

In 1936, Kahlo joined the Fourth International (a Communist organization) and often used La Casa Azul as a meeting point for international intellectuals, artists, and activists. She also offered the house where the exiled Russian Communist leader Leon Trotsky and his wife, Natalia Sedova, could take up residence once they were granted asylum in Mexico. In 1937, as well as helping Trotsky, Kahlo and the political icon embarked on a short love affair. Trotsky and his wife remained in La Casa Azul until mid-1939.

During a visit to Mexico City in 1938, the founder of Surrealism , André Breton , was enchanted with Kahlo's painting, and wrote to his friend and art dealer, Julien Levy , who quickly invited Kahlo to hold her first solo show at his gallery in New York. This time round, Kahlo traveled to the States without Rivera and upon arrival caused a huge media sensation. People were attracted to her colorful and exotic (but actually traditional) Mexican costumes and her exhibition was a success. Georgia O'Keeffe was one of the notable guests to attend Kahlo's opening. Kahlo enjoyed some months socializing in New York and then sailed to Paris in early 1939 to exhibit with the Surrealists there. That exhibition was not as successful and she became quickly tired of the over-intellectualism of the Surrealist group. Kahlo returned to New York hoping to continue her love affair with Muray, but he broke off the relationship as he had recently met somebody else. Thus Kahlo traveled back to Mexico City and upon her return Rivera requested a divorce.

Later Years and Death

Following her divorce, Kahlo moved back to La Casa Azul. She moved away from her smaller paintings and began to work on much larger canvases. In 1940 Kahlo and Rivera remarried and their relationship became less turbulent as Kahlo's health deteriorated. Between the years of 1940-1956, the suffering artist often had to wear supportive back corsets to help her spinal problems, she also had an infectious skin condition, along with syphilis. When her father died in 1941, this exacerbated both her depression and her health. She again was often housebound and found simple pleasure in surrounding herself by animals and in tending to the garden at La Casa Azul.

Meanwhile, throughout the 1940s, Kahlo's work grew in notoriety and acclaim from international collectors, and was included in several group shows both in the United States and in Mexico. In 1943, her work was included in Women Artists at Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century Gallery in New York. In this same year, Kahlo accepted a teaching position at a painting school in Mexico City (the school known as La Esmeralda ), and acquired some highly devoted students with whom she undertook some mural commissions. She struggled to continue making a living from her art, never accommodating to clients' wishes if she did not like them, but luckily received a national prize for her painting Moses (1945) and then The Two Fridas painting was bought by the Museo de Arte Moderno in 1947. Meanwhile, the artist grew progressively ill. She had a complicated operation to try and straighten her spine, but it failed and from 1950 onwards, she was often confined to a wheelchair.

She continued to paint relatively prolifically in her final years while also maintaining her political activism, and protesting nuclear testing by Western powers. Kahlo exhibited one last time in Mexico in 1953 at Lola Alvarez Bravo's gallery, her first and only solo show in Mexico. She was brought to the event in an ambulance, with her four-poster bed following on the back of a truck. The bed was then placed in the center of the gallery so that she could lie there for the duration of the opening. Kahlo died in 1954 at La Casa Azul. While the official cause of death was given as pulmonary embolism, questions have been raised about suicide - either deliberate of accidental. She was 47 years old.

The Legacy of Frida Kahlo

As an individualist who was disengaged from any official artistic movement, Kahlo's artwork has been associated with Primitivism , Indigenism , Magic Realism , and Surrealism . Posthumously, Kahlo's artwork has grown profoundly influential for feminist studies and postcolonial debates, while Kahlo has become an international cultural icon. The artist's celebrity status for mass audiences has at times resulted in the compartmentalization of the artist's work as representative of interwar Latin American artwork at large, distanced from the complexities of Kahlo's deeply personal subject matter. Recent exhibitions, such as Unbound: Contemporary Art After Frida Kahlo (2014) at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago have attempted to reframe Kahlo's cultural significance by underscoring her lasting impact on the politics of the body and Kahlo's challenge to mainstream aesthetics of representation. Dreamers Awake (2017) held at The White Cube Gallery in London further illustrated the huge influence that Frida Kahlo and a handful of other early female Surrealists have had on the development and progression of female art.

The legacy of Kahlo cannot be underestimated or exaggerated. Not only is it likely that every female artist making art since the 1950s will quote her as an influence, but it is not only artists and those who are interested in art that she inspires. Her art also supports people who suffer as result of accident, as result of miscarriage, and as result of failed marriage. Through imagery, Kahlo articulated experiences so complex, making them more manageable and giving viewers hope that they can endure, recover, and start again.

Influences and Connections

Useful Resources on Frida Kahlo

- Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo Our Pick By Hayden Herrera

- Frida Kahlo: Her Photos By Pablo Ortiz Monasterio

- Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up Our Pick By Claire Wilcox and Circe Henestrosa

- Frida Kahlo at Home Our Pick By Suzanne Barbezat

- Frida Kahlo: The Last Interview: and Other Conversations (The Last Interview Series) By Hayden Herrera

- Frida Kahlo I Paint My Reality By Christina Burrus

- Frida & Diego: Art, Love, Life By Cateherine Reef

- The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait Our Pick By Carlos Fuentes

- Frida by Frida By Frida Kahlo and Raquel Tibol

- Frida Kahlo: The Paintings Our Pick By Hayden Herrera

- Frida Kahlo By Emma Dexter, Tanya Barson

- Frida Kahlo Retrospective By Peter von Becker, Ingried Brugger, Salamon Grimberg, Cristina Kahlo, Arnaldo Kraus, Helga Prignitz-Poda, Francisco Reyes Palma, Florian Steininger, Jeanette Zqingenberger

- Frida Kahlo Masterpieces of Art By Julian Beecroft

- Kahlo (Basic Art Series 2.0) Our Pick By Andrea Kettenmann

- Frida Kahlo's Gadren Our Pick By Adriana Zavala

- The Museum of Modern Art: Discussion of Portrait with Cropped Hair by Frida Kahlo

- Frida Kahlo: The woman behind the legend - TED_Ed

- Frida Kahlo's 'The Two Fridas” - Great Art Explained Our Pick

- Frida Kahlo: Life of an Artist - Art History School Our Pick

- A Tour of Frida Kahlo’s Blue House – La Casa Azul

- La Casa Azul - Museo Frida Kahlo in Mexico City Our Pick The artist's house museum

- Works from La Casa Azul - Museo Frida Kahlo in Mexico City Our Pick By The Google Cultural Institute

- Frida Kahlo at the Tate Modern Website of the 2005 Exhibition

- Why Contemporary Art Is Unimaginable Without Frida Kahlo By Priscilla Frank / The Huffington Post / April 29, 2014

- Diary of a Mad Artist By Amy Fine Collins / Vanity Fair / July 2011

- The People's Artist, Herself a Work of Art Our Pick By Holland Cotter / The New York Times / February 29, 2008

- Let Fridamania Commence By Adrian Searle / The Guardian / June 6, 2005

- The Trouble with Frida Kahlo By Stephanie Mencimer / Washington Monthly / June 2002

- Frida Kahlo: A Contemporary Feminist Reading Our Pick By Liza Bakewell / Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies / 1993

- Frida Kahlo: Portrait of Chronic Pain By Carol A. Courtney, Michael A. O'Hearn, and Carla C. Franck / Physical Therapy / January 2017

- Medical Imagery in the Art of Frida Kahlo Our Pick By David Lomas, Rosemary Howell / British Medical Journal / December 1989

- Fashioning National Identity: Frida Kahlo in “Gringolandia" Our Pick By Rebecca Block and Lynda Hoffman-Jeep / Women’s Art Journal / 1999

- Art Critics on Frida Kahlo: A Comparison of Feminist and Non-Feminist Voices By Elizabeth Garber / Art Education / March 1992

- NPR: Mexican Artist Used Politics to Rock the Boat Artist Judy Chicago discusses the book she co-authored: "Frida Kahlo: Face to Face"

- Frida Our Pick A 2002 Biographical Film on Frida Kahlo, Starring Salma Hayek

- The Frida Kahlo Corporation A Company with Products Inspired by Frida Kahlo

- How Frida Kahlo Became a Global Brand By Tess Thackara / Artsy.com / Dec 19, 2017 /

Similar Art

Portrait of Lupe Marin (1938)

Egg in the church or The Snake (Date Unknown)

Self-Portrait (c. 1937-38)

Einhorn (Unicorn) (1970-72)

Related artists.

Related Movements & Topics

Content compiled and written by Katlyn Beaver

Edited and revised, with Summary and Accomplishments added by Rebecca Baillie

Frida Kahlo: Vida y obra

Explore Frida´s life in the timeline

Wilhelm (Guillermo) Kahlo, Frida’s father, is born.

Guillermo Kahlo, Self-Portrait , ca. 1907 Guillermo Kahlo, (1871–1941)

Archivo Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo. Banco de México, fiduciario en el Fideicomiso Museos Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo.

Matilde Calderón, Frida’s mother, is born.

Matilde Calderón y González , ca. 1897 Guillermo Kahlo, (1871–1941)

Diego Rivera and his twin brother are born.

Diego Rivera and his twin brother, Carlos María , 1887

The Del Carmen neighborhood, the barrio where Frida will live, is inaugurated.

Coyoacán, Mexico City, ca. 1915

Wilhelm Kahlo arrives in Mexico and changes his name to Guillermo.

Guillermo Kahlo , ca. 1892 Nicolás Winther

Guillermo Kahlo marries for the first time, but after a few years is left a widower.

Guillermo Kahlo with his daughter, María Luisa Kahlo Cardeña , December 3, 1934

Guillermo Kahlo marries Matilde Calderón.

Wedding portrait of Matilde Calderón and Guillermo Kahlo , February 21, 1898

Matilde, the first daughter, is born to the Kahlo Calderón family.

Matilde Kahlo Calderón , 1917

Adriana, Frida’s sister, is born.

Adriana Kahlo Calderón , April 18, 1920

Guillermo builds a home for his family in Coyoacán that will later be known as the Casa Azul or Blue House.

Original facade of the Casa Azul , July 16, 1930

Guillermo Kahlo is named the official photographer of monuments.

Metropolitan Cathedral, Mexico City , 1922 Guillermo Kahlo, (1871–1941)

Frida Kahlo is born.

Frida Kahlo at the age of four, 1911

Cristina, Frida’s younger sister, is born.

Cristina Kahlo , February 7, 1926 Guillermo Kahlo, (1871–1941)

The Mexican Revolution breaks out.

Mexican Revolutionary Song , 1928 Tina Modotti, (1896–1942)

Frida contracts polio.

Frida Kahlo at the age of five , 1912

Frida enrolls in high school at the National Preparatory School.

Frida Kahlo’s report card at the National Preparatory School , 1922

Frida joins “The Cachuchas.”

Panel with signatures, 1948 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

© D.R. Banco de México, fiduciario en el Fideicomiso Museos Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo.

Frida leaves school for a while.

Frida Kahlo Calderón, portrait, February 7, 1926 Guillermo Kahlo, (1871–1941)

D.R. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, México https://www.mediateca.inah.gob.mx/islandora_74/islandora/object/fotografía%3A449199

Frida is in a serious accident that will forever mark her life.

Folk toys, April 1929 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida paints her first self-portrait.

Intervened photo of Self-Portrait (with velvet attire), 1926 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida paints to help with her medical bills.

Portrait of Miguel N. Lira, 1927 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida begins a close relationship with Diego Rivera.

Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, and other intellectuals march on International Workers’ Day , May 1, 1929

D.R. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, México https://www.mediateca.inah.gob.mx/islandora_74/islandora/object/fotografía%3A392913

Frida and Diego are married.

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera on their wedding day , August 21, 1929

Frida paints The Bus, a work referring to her accident.

The Bus , 1929 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida has her first pregnancy.

Frida Kahlo at the Casa Azul (Blue House) , August 1930

Diego pays the debt that hangs over the Kahlo household.

Diego Rivera’s Studio in the Casa Azul, December 25, 1930 Guillermo Kahlo, (1871–1941)

Frida and Diego live for a while in San Francisco, California.

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera , ca. 1931 Peter A. Juley, (1962–1937)

Frida poses for the earliest portraits that will immortalize her Mexican attire.

Frida Kahlo in San Francisco, California , 1931 Imogen Cunningham, (1883–1976)

Frida travels to Mexico City, where she meets photographer Nickolas Muray.

Nickolas Muray and Frida Kahlo at the Casa Azul, Coyoacán, Mexico City , 1939 Nickolas Muray, (1892–1965)

Frida paints her canvas Frieda and Diego Rivera.

Frieda and Diego Rivera , 1931 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida and Diego return to Mexico, where they meet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein.

Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, and friends, ca . 1929

© D.R. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, México https://mediateca.inah.gob.mx/islandora_74/islandora/object/fotografia%3A392913

Frida and Diego briefly live in New York.

Lucienne Bloch in New York, U.S.A.

Diego and Frida move to Detroit, Michigan.

Frida Kahlo at the Detroit Art Institute, Michigan, 1932

Frida paints her Self-Portrait (on the Border between Mexico and the United States).

Self-Portrait (on the Border between Mexico and the United States), 1932 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida paints Frida and the Cesarean (unfinished).

Frida and the Cesarean, 1932 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

In July, Frida paints Henry Ford Hospital (The Flying Bed).

Henry Ford Hospital (The Flying Bed) , 1932 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida travels to Mexico to see her ailing mother.

Frida Kahlo Back from Detroit, 1932 Lucienne Bloch, (1909–1999)

Frida’s mother dies.

Matilde Calderón , 1932 Guillermo Kahlo, (1871–1941)

Frida and Diego move to New York, where Rivera paints the controversial Rockefeller Center mural.

Diego and Frida with the assistants on the Rockefeller Center mural, May 18, 1933 El Universal Gráfico

Frida paints the unfinished canvas, New York.

New York (unfinished), ca. 1933 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida paints My Dress Hangs Here (There Hangs My Dress/Allá cuelga mi vestido).

My Dress Hangs Here (There Hangs My Dress/Allá cuelga mi vestido) , 1933 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida and Diego move into their house in San Angel.

Frida Kahlo in the house in San Angel , 1938 Nickolas Muray, (1892–1965)

Frida is hospitalized three times.

Frida Kahlo , October 16, 1932 Guillermo Kahlo, (1871–1941)

Frida meets sculptor Isamu Noguchi.

Sculptor Isamu Noguchi , 1935 Edward Weston, (1886–1958)

Frida paints Self-Portrait (with Curly Hair/pelo rizado).

Self-Portrait (with Curly Hair/rizado) , ca. 1935 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

© D.R. Banco de México, fiduciario en el Fideicomiso Museos Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo

Frida paints A Few Small Jabs/Unos cuantos piquetitos.

A Few Small Jabs/Unos cuantos piquetitos , 1935 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

With the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Frida and Diego seek aid for the Republicans.

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera in the home of Luther Burbank, California, 1931

Frida has another operation on her right foot.

Frida Kahlo at the Casa Azul

Frida exhibits at the Gallery of the Department of Social Action of the Autonomous University of Mexico.

My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (Genealogical Tree) , 1936 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida paints Portrait of Alberto Misrachi.

Portrait of Alberto Misrachi, 1937 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida and Diego receive Russian leader Leon Trotsky in their home.

Frida Kahlo and Leon Trotsky, accompanied by Antonio Villalobos, Colonel José Escudero, and Jean Van Heijenoort, 1937

Frida appears in the October issue of Vogue magazine.

Frida Kahlo Senora Diego Rivera standing next to an agave plant, during a photo shoot for Vogue magazine, “Ladies of Mexico,” 1937 Toni Frissell, (1907–1988)

Frissell, T., photographer. (1937) [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2013651907/ .

Frida paints Fulang-Chang and Me.

Fulang-Chang and Me, 1937 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

French writer André Breton comes to Mexico and is struck by Frida’s art.

André Breton , July 29, 1938 Man Ray (1890–1976) Jacqueline Lamba , 1939

Frida and Diego travel with the Breton-Lamba and Trotsky-Sedova couples to cities in Mexico.

Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, Natalia Sedova, Leon Trotsky, Jacqueline Lamba, and André Breton , 1938

Frida has her first solo exhibition in New York.

Invitation to the Frida Kahlo exhibition in the Julien Levy gallery in New York, 1938

Frida paints The Four Inhabitants of Mexico City (The Zocalo Is His/Theirs zócalo es suyo).

The Four Inhabitants of Mexico City (The Zocalo is His/Theirs) , 1937 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida paints Ixcuhintli [sic] Dog with Me.

Ixcuhintli [sic] Dog with Me, 1938 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida paints The Suicide of Dorothy Hale.

The Suicide of Dorothy Hale , 1938 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida is photographed by her friends Julien Levy and Nickolas Muray.

Frida Kahlo with Magenta Rebozo, 1939 Nickolas Muray, (1892–1965)

Frida goes to Paris to exhibit some of her paintings.

Frida Kahlo’s passport , 1938

Marcel Duchamp helps Frida exhibit in Paris.

Invitation to the Mexique exhibition in Paris, France, 1939

Banco de México, fiduciario en el Fideicomiso Museos Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo.

After the Mexique exhibition, the Musée du Louvre buys one of Frida’s works.

The Frame , 1938 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida is invited to exhibit in London, but she rejects the offer because war is imminent.

Letter from Peggy Guggenheim to Frida Kahlo, 1939 Peggy Guggengheim, (1898–1979)

Frida paints What the Water Has Given to Me.

What the Water Has Given Me , 1939 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida and Diego get divorced.

Pair of clocks intervened by Frida Kahlo Inscriptions, left clock: “1939, September. The hours were broken.” (alluding to her divorce); right clock: “In San Francisco, California, December 8, 40 to eleven,” (date when she and Diego remarry). Museo Frida Kahlo, Mexico City.

Kahlo paints one of her most famous works: The Two Fridas.

The Two Fridas, 1939 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida participates in several international exhibitions.

The Wounded TableLa , 1940 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Leon Trotsky is assassinated.

Leon Trotsky

Frida paints Self-Portrait with Monkey and Ribbon on Her Neck.

Self-Portrait with Monkey and Ribbon on Her Neck , 1940 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida paints Self-Portrait (dedicated to Dr. Leo Eloesser).

Self-Portrait (dedicated to Dr. Leo Eloesser), 1940 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida paints Self-Portrait with Necklace of Thorns and Hummingbird./Autorretrato con collar de espinas y colibrí.

Self-Portrait with Necklace of Thorns and Hummingbird, 1940 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida paints Self-Portrait with Short Hair.

Self-Portrait with Short Hair, 1940 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida did a detailed drawing of what her house looked like.

My Blue House Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Archive Banco de México, fiduciario en el Fideicomiso Museos Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo.

Frida and Diego get remarried.

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera in the Casa Azul, ca. 1950 Florence Arquin, (1900–1974)

Frida and muralist Emmy Lou Packard become friends.

Frida and Emmy Lou Packard at the Casa Azul, 1941

Archivo Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. Banco de México, fiduciario en el Fideicomiso Museos Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo.

Frida paints Self-Portrait (Me and My Parakeets/Yo y mis pericos).

Self-Portrait (Me and My Parakeets/Yo y mis pericos) , 1941 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Guillermo Kahlo dies.

Guillermo Kahlo, self-portrait, 1925 Guillermo Kahlo, (1871–1941)

Frida exhibits in the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston.

Frida Kahlo in her studio, ca. 1949 Antonio Kahlo, (1932–1964)

Construction begins on the Anahuacalli.

Diego Rivera at the construction of the Anahuacalli, ca. 1949 Jacqueline Roberts

Frida paints Still Life.

Still Life, 1942 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida again exhibits her work in the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Frida Kahlo seated at/on the Casa Azul pyramid with her Self-Portrait as Tehuana or Diego on My Mind , 1943 Florence Arquin, (1900–1974)

Frida paints Self-Portrait as Tehuana or Diego on My Mind.

Self-Portrait as Tehuana or Diego on My Mind , 1943 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida paints Self-Portrait (with Monkeys).

Self-Portrait (with Monkeys), 1943 Frida Kahlo, (1907–1954)

Frida gives classes to the group of Los Fridos.

Frida Kahlo

Frida exhibits her work in Philadelphia and New York.

31 Women Artists Show their Work (intervened newspaper clipping) , 1943 Edward Alden Jewell, (1888–1947)