How to write a research plan: Step-by-step guide

Last updated

30 January 2024

Reviewed by

Today’s businesses and institutions rely on data and analytics to inform their product and service decisions. These metrics influence how organizations stay competitive and inspire innovation. However, gathering data and insights requires carefully constructed research, and every research project needs a roadmap. This is where a research plan comes into play.

There’s general research planning; then there’s an official, well-executed research plan. Whatever data-driven research project you’re gearing up for, the research plan will be your framework for execution. The plan should also be detailed and thorough, with a diligent set of criteria to formulate your research efforts. Not including these key elements in your plan can be just as harmful as having no plan at all.

Read this step-by-step guide for writing a detailed research plan that can apply to any project, whether it’s scientific, educational, or business-related.

- What is a research plan?

A research plan is a documented overview of a project in its entirety, from end to end. It details the research efforts, participants, and methods needed, along with any anticipated results. It also outlines the project’s goals and mission, creating layers of steps to achieve those goals within a specified timeline.

Without a research plan, you and your team are flying blind, potentially wasting time and resources to pursue research without structured guidance.

The principal investigator, or PI, is responsible for facilitating the research oversight. They will create the research plan and inform team members and stakeholders of every detail relating to the project. The PI will also use the research plan to inform decision-making throughout the project.

- Why do you need a research plan?

Create a research plan before starting any official research to maximize every effort in pursuing and collecting the research data. Crucially, the plan will model the activities needed at each phase of the research project.

Like any roadmap, a research plan serves as a valuable tool providing direction for those involved in the project—both internally and externally. It will keep you and your immediate team organized and task-focused while also providing necessary definitions and timelines so you can execute your project initiatives with full understanding and transparency.

External stakeholders appreciate a working research plan because it’s a great communication tool, documenting progress and changing dynamics as they arise. Any participants of your planned research sessions will be informed about the purpose of your study, while the exercises will be based on the key messaging outlined in the official plan.

Here are some of the benefits of creating a research plan document for every project:

Project organization and structure

Well-informed participants

All stakeholders and teams align in support of the project

Clearly defined project definitions and purposes

Distractions are eliminated, prioritizing task focus

Timely management of individual task schedules and roles

Costly reworks are avoided

- What should a research plan include?

The different aspects of your research plan will depend on the nature of the project. However, most official research plan documents will include the core elements below. Each aims to define the problem statement, devising an official plan for seeking a solution.

Specific project goals and individual objectives

Ideal strategies or methods for reaching those goals

Required resources

Descriptions of the target audience, sample sizes, demographics, and scopes

Key performance indicators (KPIs)

Project background

Research and testing support

Preliminary studies and progress reporting mechanisms

Cost estimates and change order processes

Depending on the research project’s size and scope, your research plan could be brief—perhaps only a few pages of documented plans. Alternatively, it could be a fully comprehensive report. Either way, it’s an essential first step in dictating your project’s facilitation in the most efficient and effective way.

- How to write a research plan for your project

When you start writing your research plan, aim to be detailed about each step, requirement, and idea. The more time you spend curating your research plan, the more precise your research execution efforts will be.

Account for every potential scenario, and be sure to address each and every aspect of the research.

Consider following this flow to develop a great research plan for your project:

Define your project’s purpose

Start by defining your project’s purpose. Identify what your project aims to accomplish and what you are researching. Remember to use clear language.

Thinking about the project’s purpose will help you set realistic goals and inform how you divide tasks and assign responsibilities. These individual tasks will be your stepping stones to reach your overarching goal.

Additionally, you’ll want to identify the specific problem, the usability metrics needed, and the intended solutions.

Know the following three things about your project’s purpose before you outline anything else:

What you’re doing

Why you’re doing it

What you expect from it

Identify individual objectives

With your overarching project objectives in place, you can identify any individual goals or steps needed to reach those objectives. Break them down into phases or steps. You can work backward from the project goal and identify every process required to facilitate it.

Be mindful to identify each unique task so that you can assign responsibilities to various team members. At this point in your research plan development, you’ll also want to assign priority to those smaller, more manageable steps and phases that require more immediate or dedicated attention.

Select research methods

Research methods might include any of the following:

User interviews: this is a qualitative research method where researchers engage with participants in one-on-one or group conversations. The aim is to gather insights into their experiences, preferences, and opinions to uncover patterns, trends, and data.

Field studies: this approach allows for a contextual understanding of behaviors, interactions, and processes in real-world settings. It involves the researcher immersing themselves in the field, conducting observations, interviews, or experiments to gather in-depth insights.

Card sorting: participants categorize information by sorting content cards into groups based on their perceived similarities. You might use this process to gain insights into participants’ mental models and preferences when navigating or organizing information on websites, apps, or other systems.

Focus groups: use organized discussions among select groups of participants to provide relevant views and experiences about a particular topic.

Diary studies: ask participants to record their experiences, thoughts, and activities in a diary over a specified period. This method provides a deeper understanding of user experiences, uncovers patterns, and identifies areas for improvement.

Five-second testing: participants are shown a design, such as a web page or interface, for just five seconds. They then answer questions about their initial impressions and recall, allowing you to evaluate the design’s effectiveness.

Surveys: get feedback from participant groups with structured surveys. You can use online forms, telephone interviews, or paper questionnaires to reveal trends, patterns, and correlations.

Tree testing: tree testing involves researching web assets through the lens of findability and navigability. Participants are given a textual representation of the site’s hierarchy (the “tree”) and asked to locate specific information or complete tasks by selecting paths.

Usability testing: ask participants to interact with a product, website, or application to evaluate its ease of use. This method enables you to uncover areas for improvement in digital key feature functionality by observing participants using the product.

Live website testing: research and collect analytics that outlines the design, usability, and performance efficiencies of a website in real time.

There are no limits to the number of research methods you could use within your project. Just make sure your research methods help you determine the following:

What do you plan to do with the research findings?

What decisions will this research inform? How can your stakeholders leverage the research data and results?

Recruit participants and allocate tasks

Next, identify the participants needed to complete the research and the resources required to complete the tasks. Different people will be proficient at different tasks, and having a task allocation plan will allow everything to run smoothly.

Prepare a thorough project summary

Every well-designed research plan will feature a project summary. This official summary will guide your research alongside its communications or messaging. You’ll use the summary while recruiting participants and during stakeholder meetings. It can also be useful when conducting field studies.

Ensure this summary includes all the elements of your research project. Separate the steps into an easily explainable piece of text that includes the following:

An introduction: the message you’ll deliver to participants about the interview, pre-planned questioning, and testing tasks.

Interview questions: prepare questions you intend to ask participants as part of your research study, guiding the sessions from start to finish.

An exit message: draft messaging your teams will use to conclude testing or survey sessions. These should include the next steps and express gratitude for the participant’s time.

Create a realistic timeline

While your project might already have a deadline or a results timeline in place, you’ll need to consider the time needed to execute it effectively.

Realistically outline the time needed to properly execute each supporting phase of research and implementation. And, as you evaluate the necessary schedules, be sure to include additional time for achieving each milestone in case any changes or unexpected delays arise.

For this part of your research plan, you might find it helpful to create visuals to ensure your research team and stakeholders fully understand the information.

Determine how to present your results

A research plan must also describe how you intend to present your results. Depending on the nature of your project and its goals, you might dedicate one team member (the PI) or assume responsibility for communicating the findings yourself.

In this part of the research plan, you’ll articulate how you’ll share the results. Detail any materials you’ll use, such as:

Presentations and slides

A project report booklet

A project findings pamphlet

Documents with key takeaways and statistics

Graphic visuals to support your findings

- Format your research plan

As you create your research plan, you can enjoy a little creative freedom. A plan can assume many forms, so format it how you see fit. Determine the best layout based on your specific project, intended communications, and the preferences of your teams and stakeholders.

Find format inspiration among the following layouts:

Written outlines

Narrative storytelling

Visual mapping

Graphic timelines

Remember, the research plan format you choose will be subject to change and adaptation as your research and findings unfold. However, your final format should ideally outline questions, problems, opportunities, and expectations.

- Research plan example

Imagine you’ve been tasked with finding out how to get more customers to order takeout from an online food delivery platform. The goal is to improve satisfaction and retain existing customers. You set out to discover why more people aren’t ordering and what it is they do want to order or experience.

You identify the need for a research project that helps you understand what drives customer loyalty. But before you jump in and start calling past customers, you need to develop a research plan—the roadmap that provides focus, clarity, and realistic details to the project.

Here’s an example outline of a research plan you might put together:

Project title

Project members involved in the research plan

Purpose of the project (provide a summary of the research plan’s intent)

Objective 1 (provide a short description for each objective)

Objective 2

Objective 3

Proposed timeline

Audience (detail the group you want to research, such as customers or non-customers)

Budget (how much you think it might cost to do the research)

Risk factors/contingencies (any potential risk factors that may impact the project’s success)

Remember, your research plan doesn’t have to reinvent the wheel—it just needs to fit your project’s unique needs and aims.

Customizing a research plan template

Some companies offer research plan templates to help get you started. However, it may make more sense to develop your own customized plan template. Be sure to include the core elements of a great research plan with your template layout, including the following:

Introductions to participants and stakeholders

Background problems and needs statement

Significance, ethics, and purpose

Research methods, questions, and designs

Preliminary beliefs and expectations

Implications and intended outcomes

Realistic timelines for each phase

Conclusion and presentations

How many pages should a research plan be?

Generally, a research plan can vary in length between 500 to 1,500 words. This is roughly three pages of content. More substantial projects will be 2,000 to 3,500 words, taking up four to seven pages of planning documents.

What is the difference between a research plan and a research proposal?

A research plan is a roadmap to success for research teams. A research proposal, on the other hand, is a dissertation aimed at convincing or earning the support of others. Both are relevant in creating a guide to follow to complete a project goal.

What are the seven steps to developing a research plan?

While each research project is different, it’s best to follow these seven general steps to create your research plan:

Defining the problem

Identifying goals

Choosing research methods

Recruiting participants

Preparing the brief or summary

Establishing task timelines

Defining how you will present the findings

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 12 May 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 18 May 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

FLEET LIBRARY | Research Guides

Rhode island school of design, create a research plan: research plan.

- Research Plan

- Literature Review

- Ulrich's Global Serials Directory

- Related Guides

A research plan is a framework that shows how you intend to approach your topic. The plan can take many forms: a written outline, a narrative, a visual/concept map or timeline. It's a document that will change and develop as you conduct your research. Components of a research plan

1. Research conceptualization - introduces your research question

2. Research methodology - describes your approach to the research question

3. Literature review, critical evaluation and synthesis - systematic approach to locating,

reviewing and evaluating the work (text, exhibitions, critiques, etc) relating to your topic

4. Communication - geared toward an intended audience, shows evidence of your inquiry

Research conceptualization refers to the ability to identify specific research questions, problems or opportunities that are worthy of inquiry. Research conceptualization also includes the skills and discipline that go beyond the initial moment of conception, and which enable the researcher to formulate and develop an idea into something researchable ( Newbury 373).

Research methodology refers to the knowledge and skills required to select and apply appropriate methods to carry through the research project ( Newbury 374) .

Method describes a single mode of proceeding; methodology describes the overall process.

Method - a way of doing anything especially according to a defined and regular plan; a mode of procedure in any activity

Methodology - the study of the direction and implications of empirical research, or the sustainability of techniques employed in it; a method or body of methods used in a particular field of study or activity *Browse a list of research methodology books or this guide on Art & Design Research

Literature Review, critical evaluation & synthesis

A literature review is a systematic approach to locating, reviewing, and evaluating the published work and work in progress of scholars, researchers, and practitioners on a given topic.

Critical evaluation and synthesis is the ability to handle (or process) existing sources. It includes knowledge of the sources of literature and contextual research field within which the person is working ( Newbury 373).

Literature reviews are done for many reasons and situations. Here's a short list:

Sources to consult while conducting a literature review:

Online catalogs of local, regional, national, and special libraries

meta-catalogs such as worldcat , Art Discovery Group , europeana , world digital library or RIBA

subject-specific online article databases (such as the Avery Index, JSTOR, Project Muse)

digital institutional repositories such as Digital Commons @RISD ; see Registry of Open Access Repositories

Open Access Resources recommended by RISD Research LIbrarians

works cited in scholarly books and articles

print bibliographies

the internet-locate major nonprofit, research institutes, museum, university, and government websites

search google scholar to locate grey literature & referenced citations

trade and scholarly publishers

fellow scholars and peers

Communication

Communication refers to the ability to

- structure a coherent line of inquiry

- communicate your findings to your intended audience

- make skilled use of visual material to express ideas for presentations, writing, and the creation of exhibitions ( Newbury 374)

Research plan framework: Newbury, Darren. "Research Training in the Creative Arts and Design." The Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts . Ed. Michael Biggs and Henrik Karlsson. New York: Routledge, 2010. 368-87. Print.

About the author

Except where otherwise noted, this guide is subject to a Creative Commons Attribution license

source document

Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts

- Next: Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Sep 20, 2023 5:05 PM

- URL: https://risd.libguides.com/researchplan

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you’re on board with our cookie policy

- A Research Guide

- Research Paper Guide

How to Write a Research Plan

- Research plan definition

- Purpose of a research plan

- Research plan structure

- Step-by-step writing guide

Tips for creating a research plan

- Research plan examples

Research plan: definition and significance

What is the purpose of a research plan.

- Bridging gaps in the existing knowledge related to their subject.

- Reinforcing established research about their subject.

- Introducing insights that contribute to subject understanding.

Research plan structure & template

Introduction.

- What is the existing knowledge about the subject?

- What gaps remain unanswered?

- How will your research enrich understanding, practice, and policy?

Literature review

Expected results.

- Express how your research can challenge established theories in your field.

- Highlight how your work lays the groundwork for future research endeavors.

- Emphasize how your work can potentially address real-world problems.

5 Steps to crafting an effective research plan

Step 1: define the project purpose, step 2: select the research method, step 3: manage the task and timeline, step 4: write a summary, step 5: plan the result presentation.

- Brainstorm Collaboratively: Initiate a collective brainstorming session with peers or experts. Outline the essential questions that warrant exploration and answers within your research.

- Prioritize and Feasibility: Evaluate the list of questions and prioritize those that are achievable and important. Focus on questions that can realistically be addressed.

- Define Key Terminology: Define technical terms pertinent to your research, fostering a shared understanding. Ensure that terms like “church” or “unreached people group” are well-defined to prevent ambiguity.

- Organize your approach: Once well-acquainted with your institution’s regulations, organize each aspect of your research by these guidelines. Allocate appropriate word counts for different sections and components of your research paper.

Research plan example

- Writing a Research Paper

- Research Paper Title

- Research Paper Sources

- Research Paper Problem Statement

- Research Paper Thesis Statement

- Hypothesis for a Research Paper

- Research Question

- Research Paper Outline

- Research Paper Summary

- Research Paper Prospectus

- Research Paper Proposal

- Research Paper Format

- Research Paper Styles

- AMA Style Research Paper

- MLA Style Research Paper

- Chicago Style Research Paper

- APA Style Research Paper

- Research Paper Structure

- Research Paper Cover Page

- Research Paper Abstract

- Research Paper Introduction

- Research Paper Body Paragraph

- Research Paper Literature Review

- Research Paper Background

- Research Paper Methods Section

- Research Paper Results Section

- Research Paper Discussion Section

- Research Paper Conclusion

- Research Paper Appendix

- Research Paper Bibliography

- APA Reference Page

- Annotated Bibliography

- Bibliography vs Works Cited vs References Page

- Research Paper Types

- What is Qualitative Research

Receive paper in 3 Hours!

- Choose the number of pages.

- Select your deadline.

- Complete your order.

Number of Pages

550 words (double spaced)

Deadline: 10 days left

By clicking "Log In", you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We'll occasionally send you account related and promo emails.

Sign Up for your FREE account

Developing a Research Plan

- First Online: 20 September 2022

Cite this chapter

- Habeeb Adewale Ajimotokan 2

Part of the book series: SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology ((BRIEFSAPPLSCIENCES))

966 Accesses

The objectives of this chapter are to

Describe the terms research proposal and research protocol;

Specify and discuss the elements of research proposal;

Specify the goals of research protocol;

Outline preferable sequence for the different section headings of a research protocol and discuss their contents; and

Discuss the basic engineering research tools and techniques.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

5StarEssays. (2020). Writing a research proposal—Outline, format and examples. In Complete guide to writing a research paper . Retrieved from https://www.5staressays.com/blog/writing-research-proposal

Walliman, N. (2011). Research methods: The basics . Routledge—Taylor and Francis Group.

Google Scholar

Olujide, J. O. (2004). Writing a research proposal. In H. A. Saliu & J. O. Oyebanji (Eds.), A guide on research proposal and report writing (Ch. 7, pp. 67–79). Faculty of Business and Social Sciences, Unilorin.

Thiel, D. V. (2014). Research methods for engineers . University Printing House, University of Cambridge.

Book Google Scholar

Mouton, J. (2001). How to succeed in your master’s and doctoral studies. Van Schaik.

Lues, L., & Lategan, L. O. K. (2006). RE: Search ABC (1st ed.). Sun Press.

Bak, N. (2004). Completing your thesis: A practical guide . Van Schaik.

Sadiku, M. N. O. (2000). Numerical techniques in electromagnetics . CRC Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria

Habeeb Adewale Ajimotokan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Ajimotokan, H.A. (2023). Developing a Research Plan. In: Research Techniques. SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13109-7_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13109-7_4

Published : 20 September 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-13108-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-13109-7

eBook Packages : Engineering Engineering (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

What (Exactly) Is A Research Proposal?

A simple explainer with examples + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020 (Updated April 2023)

Whether you’re nearing the end of your degree and your dissertation is on the horizon, or you’re planning to apply for a PhD program, chances are you’ll need to craft a convincing research proposal . If you’re on this page, you’re probably unsure exactly what the research proposal is all about. Well, you’ve come to the right place.

Overview: Research Proposal Basics

- What a research proposal is

- What a research proposal needs to cover

- How to structure your research proposal

- Example /sample proposals

- Proposal writing FAQs

- Key takeaways & additional resources

What is a research proposal?

Simply put, a research proposal is a structured, formal document that explains what you plan to research (your research topic), why it’s worth researching (your justification), and how you plan to investigate it (your methodology).

The purpose of the research proposal (its job, so to speak) is to convince your research supervisor, committee or university that your research is suitable (for the requirements of the degree program) and manageable (given the time and resource constraints you will face).

The most important word here is “ convince ” – in other words, your research proposal needs to sell your research idea (to whoever is going to approve it). If it doesn’t convince them (of its suitability and manageability), you’ll need to revise and resubmit . This will cost you valuable time, which will either delay the start of your research or eat into its time allowance (which is bad news).

What goes into a research proposal?

A good dissertation or thesis proposal needs to cover the “ what “, “ why ” and” how ” of the proposed study. Let’s look at each of these attributes in a little more detail:

Your proposal needs to clearly articulate your research topic . This needs to be specific and unambiguous . Your research topic should make it clear exactly what you plan to research and in what context. Here’s an example of a well-articulated research topic:

An investigation into the factors which impact female Generation Y consumer’s likelihood to promote a specific makeup brand to their peers: a British context

As you can see, this topic is extremely clear. From this one line we can see exactly:

- What’s being investigated – factors that make people promote or advocate for a brand of a specific makeup brand

- Who it involves – female Gen-Y consumers

- In what context – the United Kingdom

So, make sure that your research proposal provides a detailed explanation of your research topic . If possible, also briefly outline your research aims and objectives , and perhaps even your research questions (although in some cases you’ll only develop these at a later stage). Needless to say, don’t start writing your proposal until you have a clear topic in mind , or you’ll end up waffling and your research proposal will suffer as a result of this.

Need a helping hand?

As we touched on earlier, it’s not good enough to simply propose a research topic – you need to justify why your topic is original . In other words, what makes it unique ? What gap in the current literature does it fill? If it’s simply a rehash of the existing research, it’s probably not going to get approval – it needs to be fresh.

But, originality alone is not enough. Once you’ve ticked that box, you also need to justify why your proposed topic is important . In other words, what value will it add to the world if you achieve your research aims?

As an example, let’s look at the sample research topic we mentioned earlier (factors impacting brand advocacy). In this case, if the research could uncover relevant factors, these findings would be very useful to marketers in the cosmetics industry, and would, therefore, have commercial value . That is a clear justification for the research.

So, when you’re crafting your research proposal, remember that it’s not enough for a topic to simply be unique. It needs to be useful and value-creating – and you need to convey that value in your proposal. If you’re struggling to find a research topic that makes the cut, watch our video covering how to find a research topic .

It’s all good and well to have a great topic that’s original and valuable, but you’re not going to convince anyone to approve it without discussing the practicalities – in other words:

- How will you actually undertake your research (i.e., your methodology)?

- Is your research methodology appropriate given your research aims?

- Is your approach manageable given your constraints (time, money, etc.)?

While it’s generally not expected that you’ll have a fully fleshed-out methodology at the proposal stage, you’ll likely still need to provide a high-level overview of your research methodology . Here are some important questions you’ll need to address in your research proposal:

- Will you take a qualitative , quantitative or mixed -method approach?

- What sampling strategy will you adopt?

- How will you collect your data (e.g., interviews, surveys, etc)?

- How will you analyse your data (e.g., descriptive and inferential statistics , content analysis, discourse analysis, etc, .)?

- What potential limitations will your methodology carry?

So, be sure to give some thought to the practicalities of your research and have at least a basic methodological plan before you start writing up your proposal. If this all sounds rather intimidating, the video below provides a good introduction to research methodology and the key choices you’ll need to make.

How To Structure A Research Proposal

Now that we’ve covered the key points that need to be addressed in a proposal, you may be wondering, “ But how is a research proposal structured? “.

While the exact structure and format required for a research proposal differs from university to university, there are four “essential ingredients” that commonly make up the structure of a research proposal:

- A rich introduction and background to the proposed research

- An initial literature review covering the existing research

- An overview of the proposed research methodology

- A discussion regarding the practicalities (project plans, timelines, etc.)

In the video below, we unpack each of these four sections, step by step.

Research Proposal Examples/Samples

In the video below, we provide a detailed walkthrough of two successful research proposals (Master’s and PhD-level), as well as our popular free proposal template.

Proposal Writing FAQs

How long should a research proposal be.

This varies tremendously, depending on the university, the field of study (e.g., social sciences vs natural sciences), and the level of the degree (e.g. undergraduate, Masters or PhD) – so it’s always best to check with your university what their specific requirements are before you start planning your proposal.

As a rough guide, a formal research proposal at Masters-level often ranges between 2000-3000 words, while a PhD-level proposal can be far more detailed, ranging from 5000-8000 words. In some cases, a rough outline of the topic is all that’s needed, while in other cases, universities expect a very detailed proposal that essentially forms the first three chapters of the dissertation or thesis.

The takeaway – be sure to check with your institution before you start writing.

How do I choose a topic for my research proposal?

Finding a good research topic is a process that involves multiple steps. We cover the topic ideation process in this video post.

How do I write a literature review for my proposal?

While you typically won’t need a comprehensive literature review at the proposal stage, you still need to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the key literature and are able to synthesise it. We explain the literature review process here.

How do I create a timeline and budget for my proposal?

We explain how to craft a project plan/timeline and budget in Research Proposal Bootcamp .

Which referencing format should I use in my research proposal?

The expectations and requirements regarding formatting and referencing vary from institution to institution. Therefore, you’ll need to check this information with your university.

What common proposal writing mistakes do I need to look out for?

We’ve create a video post about some of the most common mistakes students make when writing a proposal – you can access that here . If you’re short on time, here’s a quick summary:

- The research topic is too broad (or just poorly articulated).

- The research aims, objectives and questions don’t align.

- The research topic is not well justified.

- The study has a weak theoretical foundation.

- The research design is not well articulated well enough.

- Poor writing and sloppy presentation.

- Poor project planning and risk management.

- Not following the university’s specific criteria.

Key Takeaways & Additional Resources

As you write up your research proposal, remember the all-important core purpose: to convince . Your research proposal needs to sell your study in terms of suitability and viability. So, focus on crafting a convincing narrative to ensure a strong proposal.

At the same time, pay close attention to your university’s requirements. While we’ve covered the essentials here, every institution has its own set of expectations and it’s essential that you follow these to maximise your chances of approval.

By the way, we’ve got plenty more resources to help you fast-track your research proposal. Here are some of our most popular resources to get you started:

- Proposal Writing 101 : A Introductory Webinar

- Research Proposal Bootcamp : The Ultimate Online Course

- Template : A basic template to help you craft your proposal

If you’re looking for 1-on-1 support with your research proposal, be sure to check out our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the proposal development process (and the entire research journey), step by step.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

51 Comments

I truly enjoyed this video, as it was eye-opening to what I have to do in the preparation of preparing a Research proposal.

I would be interested in getting some coaching.

I real appreciate on your elaboration on how to develop research proposal,the video explains each steps clearly.

Thank you for the video. It really assisted me and my niece. I am a PhD candidate and she is an undergraduate student. It is at times, very difficult to guide a family member but with this video, my job is done.

In view of the above, I welcome more coaching.

Wonderful guidelines, thanks

This is very helpful. Would love to continue even as I prepare for starting my masters next year.

Thanks for the work done, the text was helpful to me

Bundle of thanks to you for the research proposal guide it was really good and useful if it is possible please send me the sample of research proposal

You’re most welcome. We don’t have any research proposals that we can share (the students own the intellectual property), but you might find our research proposal template useful: https://gradcoach.com/research-proposal-template/

Cheruiyot Moses Kipyegon

Thanks alot. It was an eye opener that came timely enough before my imminent proposal defense. Thanks, again

thank you very much your lesson is very interested may God be with you

I am an undergraduate student (First Degree) preparing to write my project,this video and explanation had shed more light to me thanks for your efforts keep it up.

Very useful. I am grateful.

this is a very a good guidance on research proposal, for sure i have learnt something

Wonderful guidelines for writing a research proposal, I am a student of m.phil( education), this guideline is suitable for me. Thanks

You’re welcome 🙂

Thank you, this was so helpful.

A really great and insightful video. It opened my eyes as to how to write a research paper. I would like to receive more guidance for writing my research paper from your esteemed faculty.

Thank you, great insights

Thank you, great insights, thank you so much, feeling edified

Wow thank you, great insights, thanks a lot

Thank you. This is a great insight. I am a student preparing for a PhD program. I am requested to write my Research Proposal as part of what I am required to submit before my unconditional admission. I am grateful having listened to this video which will go a long way in helping me to actually choose a topic of interest and not just any topic as well as to narrow down the topic and be specific about it. I indeed need more of this especially as am trying to choose a topic suitable for a DBA am about embarking on. Thank you once more. The video is indeed helpful.

Have learnt a lot just at the right time. Thank you so much.

thank you very much ,because have learn a lot things concerning research proposal and be blessed u for your time that you providing to help us

Hi. For my MSc medical education research, please evaluate this topic for me: Training Needs Assessment of Faculty in Medical Training Institutions in Kericho and Bomet Counties

I have really learnt a lot based on research proposal and it’s formulation

Thank you. I learn much from the proposal since it is applied

Your effort is much appreciated – you have good articulation.

You have good articulation.

I do applaud your simplified method of explaining the subject matter, which indeed has broaden my understanding of the subject matter. Definitely this would enable me writing a sellable research proposal.

This really helping

Great! I liked your tutoring on how to find a research topic and how to write a research proposal. Precise and concise. Thank you very much. Will certainly share this with my students. Research made simple indeed.

Thank you very much. I an now assist my students effectively.

Thank you very much. I can now assist my students effectively.

I need any research proposal

Thank you for these videos. I will need chapter by chapter assistance in writing my MSc dissertation

Very helpfull

the videos are very good and straight forward

thanks so much for this wonderful presentations, i really enjoyed it to the fullest wish to learn more from you

Thank you very much. I learned a lot from your lecture.

I really enjoy the in-depth knowledge on research proposal you have given. me. You have indeed broaden my understanding and skills. Thank you

interesting session this has equipped me with knowledge as i head for exams in an hour’s time, am sure i get A++

This article was most informative and easy to understand. I now have a good idea of how to write my research proposal.

Thank you very much.

Wow, this literature is very resourceful and interesting to read. I enjoyed it and I intend reading it every now then.

Thank you for the clarity

Thank you. Very helpful.

Thank you very much for this essential piece. I need 1o1 coaching, unfortunately, your service is not available in my country. Anyways, a very important eye-opener. I really enjoyed it. A thumb up to Gradcoach

What is JAM? Please explain.

Thank you so much for these videos. They are extremely helpful! God bless!

very very wonderful…

thank you for the video but i need a written example

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Illustration by James Round

How to plan a research project

Whether for a paper or a thesis, define your question, review the work of others – and leave yourself open to discovery.

by Brooke Harrington + BIO

is professor of sociology at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. Her research has won international awards both for scholarly quality and impact on public life. She has published dozens of articles and three books, most recently the bestseller Capital without Borders (2016), now translated into five languages.

Edited by Sam Haselby

Need to know

‘When curiosity turns to serious matters, it’s called research.’ – From Aphorisms (1880-1905) by Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach

Planning research projects is a time-honoured intellectual exercise: one that requires both creativity and sharp analytical skills. The purpose of this Guide is to make the process systematic and easy to understand. While there is a great deal of freedom and discovery involved – from the topics you choose, to the data and methods you apply – there are also some norms and constraints that obtain, no matter what your academic level or field of study. For those in high school through to doctoral students, and from art history to archaeology, research planning involves broadly similar steps, including: formulating a question, developing an argument or predictions based on previous research, then selecting the information needed to answer your question.

Some of this might sound self-evident but, as you’ll find, research requires a different way of approaching and using information than most of us are accustomed to in everyday life. That is why I include orienting yourself to knowledge-creation as an initial step in the process. This is a crucial and underappreciated phase in education, akin to making the transition from salaried employment to entrepreneurship: suddenly, you’re on your own, and that requires a new way of thinking about your work.

What follows is a distillation of what I’ve learned about this process over 27 years as a professional social scientist. It reflects the skills that my own professors imparted in the sociology doctoral programme at Harvard, as well as what I learned later on as a research supervisor for Ivy League PhD and MA students, and then as the author of award-winning scholarly books and articles. It can be adapted to the demands of both short projects (such as course term papers) and long ones, such as a thesis.

At its simplest, research planning involves the four distinct steps outlined below: orienting yourself to knowledge-creation; defining your research question; reviewing previous research on your question; and then choosing relevant data to formulate your own answers. Because the focus of this Guide is on planning a research project, as opposed to conducting a research project, this section won’t delve into the details of data-collection or analysis; those steps happen after you plan the project. In addition, the topic is vast: year-long doctoral courses are devoted to data and analysis. Instead, the fourth part of this section will outline some basic strategies you could use in planning a data-selection and analysis process appropriate to your research question.

Step 1: Orient yourself

Planning and conducting research requires you to make a transition, from thinking like a consumer of information to thinking like a producer of information. That sounds simple, but it’s actually a complex task. As a practical matter, this means putting aside the mindset of a student, which treats knowledge as something created by other people. As students, we are often passive receivers of knowledge: asked to do a specified set of readings, then graded on how well we reproduce what we’ve read.

Researchers, however, must take on an active role as knowledge producers . Doing research requires more of you than reading and absorbing what other people have written: you have to engage in a dialogue with it. That includes arguing with previous knowledge and perhaps trying to show that ideas we have accepted as given are actually wrong or incomplete. For example, rather than simply taking in the claims of an author you read, you’ll need to draw out the implications of those claims: if what the author is saying is true, what else does that suggest must be true? What predictions could you make based on the author’s claims?

In other words, rather than treating a reading as a source of truth – even if it comes from a revered source, such as Plato or Marie Curie – this orientation step asks you to treat the claims you read as provisional and subject to interrogation. That is one of the great pieces of wisdom that science and philosophy can teach us: that the biggest advances in human understanding have been made not by being correct about trivial things, but by being wrong in an interesting way . For example, Albert Einstein was wrong about quantum mechanics, but his arguments about it with his fellow physicist Niels Bohr have led to some of the biggest breakthroughs in science, even a century later.

Step 2: Define your research question

Students often give this step cursory attention, but experienced researchers know that formulating a good question is sometimes the most difficult part of the research planning process. That is because the precise language of the question frames the rest of the project. It’s therefore important to pose the question carefully, in a way that’s both possible to answer and likely to yield interesting results. Of course, you must choose a question that interests you, but that’s only the beginning of what’s likely to be an iterative process: most researchers come back to this step repeatedly, modifying their questions in light of previous research, resource limitations and other considerations.

Researchers face limits in terms of time and money. They, like everyone else, have to pose research questions that they can plausibly answer given the constraints they face. For example, it would be inadvisable to frame a project around the question ‘What are the roots of the Arab-Israeli conflict?’ if you have only a week to develop an answer and no background on that topic. That’s not to limit your imagination: you can come up with any question you’d like. But it typically does require some creativity to frame a question that you can answer well – that is, by investigating thoroughly and providing new insights – within the limits you face.

In addition to being interesting to you, and feasible within your resource constraints, the third and most important characteristic of a ‘good’ research topic is whether it allows you to create new knowledge. It might turn out that your question has already been asked and answered to your satisfaction: if so, you’ll find out in the next step of this process. On the other hand, you might come up with a research question that hasn’t been addressed previously. Before you get too excited about breaking uncharted ground, consider this: a lot of potentially researchable questions haven’t been studied for good reason ; they might have answers that are trivial or of very limited interest. This could include questions such as ‘Why does the area of a circle equal π r²?’ or ‘Did winter conditions affect Napoleon’s plans to invade Russia?’ Of course, you might be able to make the argument that a seemingly trivial question is actually vitally important, but you must be prepared to back that up with convincing evidence. The exercise in the ‘Learn More’ section below will help you think through some of these issues.

Finally, scholarly research questions must in some way lead to new and distinctive insights. For example, lots of people have studied gender roles in sports teams; what can you ask that hasn’t been asked before? Reinventing the wheel is the number-one no-no in this endeavour. That’s why the next step is so important: reviewing previous research on your topic. Depending on what you find in that step, you might need to revise your research question; iterating between your question and the existing literature is a normal process. But don’t worry: it doesn’t go on forever. In fact, the iterations taper off – and your research question stabilises – as you develop a firm grasp of the current state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 3: Review previous research

In academic research, from articles to books, it’s common to find a section called a ‘literature review’. The purpose of that section is to describe the state of the art in knowledge on the research question that a project has posed. It demonstrates that researchers have thoroughly and systematically reviewed the relevant findings of previous studies on their topic, and that they have something novel to contribute.

Your own research project should include something like this, even if it’s a high-school term paper. In the research planning process, you’ll want to list at least half a dozen bullet points stating the major findings on your topic by other people. In relation to those findings, you should be able to specify where your project could provide new and necessary insights. There are two basic rhetorical positions one can take in framing the novelty-plus-importance argument required of academic research:

- Position 1 requires you to build on or extend a set of existing ideas; that means saying something like: ‘Person A has argued that X is true about gender; this implies Y, which has not yet been tested. My project will test Y, and if I find evidence to support it, that will change the way we understand gender.’

- Position 2 is to argue that there is a gap in existing knowledge, either because previous research has reached conflicting conclusions or has failed to consider something important. For example, one could say that research on middle schoolers and gender has been limited by being conducted primarily in coeducational environments, and that findings might differ dramatically if research were conducted in more schools where the student body was all-male or all-female.

Your overall goal in this step of the process is to show that your research will be part of a larger conversation: that is, how your project flows from what’s already known, and how it advances, extends or challenges that existing body of knowledge. That will be the contribution of your project, and it constitutes the motivation for your research.

Two things are worth mentioning about your search for sources of relevant previous research. First, you needn’t look only at studies on your precise topic. For example, if you want to study gender-identity formation in schools, you shouldn’t restrict yourself to studies of schools; the empirical setting (schools) is secondary to the larger social process that interests you (how people form gender identity). That process occurs in many different settings, so cast a wide net. Second, be sure to use legitimate sources – meaning publications that have been through some sort of vetting process, whether that involves peer review (as with academic journal articles you might find via Google Scholar) or editorial review (as you’d find in well-known mass media publications, such as The Economist or The Washington Post ). What you’ll want to avoid is using unvetted sources such as personal blogs or Wikipedia. Why? Because anybody can write anything in those forums, and there is no way to know – unless you’re already an expert – if the claims you find there are accurate. Often, they’re not.

Step 4: Choose your data and methods

Whatever your research question is, eventually you’ll need to consider which data source and analytical strategy are most likely to provide the answers you’re seeking. One starting point is to consider whether your question would be best addressed by qualitative data (such as interviews, observations or historical records), quantitative data (such as surveys or census records) or some combination of both. Your ideas about data sources will, in turn, suggest options for analytical methods.

You might need to collect your own data, or you might find everything you need readily available in an existing dataset someone else has created. A great place to start is with a research librarian: university libraries always have them and, at public universities, those librarians can work with the public, including people who aren’t affiliated with the university. If you don’t happen to have a public university and its library close at hand, an ordinary public library can still be a good place to start: the librarians are often well versed in accessing data sources that might be relevant to your study, such as the census, or historical archives, or the Survey of Consumer Finances.

Because your task at this point is to plan research, rather than conduct it, the purpose of this step is not to commit you irrevocably to a course of action. Instead, your goal here is to think through a feasible approach to answering your research question. You’ll need to find out, for example, whether the data you want exist; if not, do you have a realistic chance of gathering the data yourself, or would it be better to modify your research question? In terms of analysis, would your strategy require you to apply statistical methods? If so, do you have those skills? If not, do you have time to learn them, or money to hire a research assistant to run the analysis for you?

Please be aware that qualitative methods in particular are not the casual undertaking they might appear to be. Many people make the mistake of thinking that only quantitative data and methods are scientific and systematic, while qualitative methods are just a fancy way of saying: ‘I talked to some people, read some old newspapers, and drew my own conclusions.’ Nothing could be further from the truth. In the final section of this guide, you’ll find some links to resources that will provide more insight on standards and procedures governing qualitative research, but suffice it to say: there are rules about what constitutes legitimate evidence and valid analytical procedure for qualitative data, just as there are for quantitative data.

Circle back and consider revising your initial plans

As you work through these four steps in planning your project, it’s perfectly normal to circle back and revise. Research planning is rarely a linear process. It’s also common for new and unexpected avenues to suggest themselves. As the sociologist Thorstein Veblen wrote in 1908 : ‘The outcome of any serious research can only be to make two questions grow where only one grew before.’ That’s as true of research planning as it is of a completed project. Try to enjoy the horizons that open up for you in this process, rather than becoming overwhelmed; the four steps, along with the two exercises that follow, will help you focus your plan and make it manageable.

Key points – How to plan a research project

- Planning a research project is essential no matter your academic level or field of study. There is no one ‘best’ way to design research, but there are certain guidelines that can be helpfully applied across disciplines.

- Orient yourself to knowledge-creation. Make the shift from being a consumer of information to being a producer of information.

- Define your research question. Your question frames the rest of your project, sets the scope, and determines the kinds of answers you can find.

- Review previous research on your question. Survey the existing body of relevant knowledge to ensure that your research will be part of a larger conversation.

- Choose your data and methods. For instance, will you be collecting qualitative data, via interviews, or numerical data, via surveys?

- Circle back and consider revising your initial plans. Expect your research question in particular to undergo multiple rounds of refinement as you learn more about your topic.

Good research questions tend to beget more questions. This can be frustrating for those who want to get down to business right away. Try to make room for the unexpected: this is usually how knowledge advances. Many of the most significant discoveries in human history have been made by people who were looking for something else entirely. There are ways to structure your research planning process without over-constraining yourself; the two exercises below are a start, and you can find further methods in the Links and Books section.

The following exercise provides a structured process for advancing your research project planning. After completing it, you’ll be able to do the following:

- describe clearly and concisely the question you’ve chosen to study

- summarise the state of the art in knowledge about the question, and where your project could contribute new insight

- identify the best strategy for gathering and analysing relevant data

In other words, the following provides a systematic means to establish the building blocks of your research project.

Exercise 1: Definition of research question and sources

This exercise prompts you to select and clarify your general interest area, develop a research question, and investigate sources of information. The annotated bibliography will also help you refine your research question so that you can begin the second assignment, a description of the phenomenon you wish to study.

Jot down a few bullet points in response to these two questions, with the understanding that you’ll probably go back and modify your answers as you begin reading other studies relevant to your topic:

- What will be the general topic of your paper?

- What will be the specific topic of your paper?

b) Research question(s)

Use the following guidelines to frame a research question – or questions – that will drive your analysis. As with Part 1 above, you’ll probably find it necessary to change or refine your research question(s) as you complete future assignments.

- Your question should be phrased so that it can’t be answered with a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

- Your question should have more than one plausible answer.

- Your question should draw relationships between two or more concepts; framing the question in terms of How? or What? often works better than asking Why ?

c) Annotated bibliography

Most or all of your background information should come from two sources: scholarly books and journals, or reputable mass media sources. You might be able to access journal articles electronically through your library, using search engines such as JSTOR and Google Scholar. This can save you a great deal of time compared with going to the library in person to search periodicals. General news sources, such as those accessible through LexisNexis, are acceptable, but should be cited sparingly, since they don’t carry the same level of credibility as scholarly sources. As discussed above, unvetted sources such as blogs and Wikipedia should be avoided, because the quality of the information they provide is unreliable and often misleading.

To create an annotated bibliography, provide the following information for at least 10 sources relevant to your specific topic, using the format suggested below.

Name of author(s):

Publication date:

Title of book, chapter, or article:

If a chapter or article, title of journal or book where they appear:

Brief description of this work, including main findings and methods ( c 75 words):

Summary of how this work contributes to your project ( c 75 words):

Brief description of the implications of this work ( c 25 words):

Identify any gap or controversy in knowledge this work points up, and how your project could address those problems ( c 50 words):

Exercise 2: Towards an analysis

Develop a short statement ( c 250 words) about the kind of data that would be useful to address your research question, and how you’d analyse it. Some questions to consider in writing this statement include:

- What are the central concepts or variables in your project? Offer a brief definition of each.

- Do any data sources exist on those concepts or variables, or would you need to collect data?

- Of the analytical strategies you could apply to that data, which would be the most appropriate to answer your question? Which would be the most feasible for you? Consider at least two methods, noting their advantages or disadvantages for your project.

Links & books

One of the best texts ever written about planning and executing research comes from a source that might be unexpected: a 60-year-old work on urban planning by a self-trained scholar. The classic book The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961) by Jane Jacobs (available complete and free of charge via this link ) is worth reading in its entirety just for the pleasure of it. But the final 20 pages – a concluding chapter titled ‘The Kind of Problem a City Is’ – are really about the process of thinking through and investigating a problem. Highly recommended as a window into the craft of research.

Jacobs’s text references an essay on advancing human knowledge by the mathematician Warren Weaver. At the time, Weaver was director of the Rockefeller Foundation, in charge of funding basic research in the natural and medical sciences. Although the essay is titled ‘A Quarter Century in the Natural Sciences’ (1960) and appears at first blush to be merely a summation of one man’s career, it turns out to be something much bigger and more interesting: a meditation on the history of human beings seeking answers to big questions about the world. Weaver goes back to the 17th century to trace the origins of systematic research thinking, with enthusiasm and vivid anecdotes that make the process come alive. The essay is worth reading in its entirety, and is available free of charge via this link .

For those seeking a more in-depth, professional-level discussion of the logic of research design, the political scientist Harvey Starr provides insight in a compact format in the article ‘Cumulation from Proper Specification: Theory, Logic, Research Design, and “Nice” Laws’ (2005). Starr reviews the ‘research triad’, consisting of the interlinked considerations of formulating a question, selecting relevant theories and applying appropriate methods. The full text of the article, published in the scholarly journal Conflict Management and Peace Science , is available, free of charge, via this link .

Finally, the book Getting What You Came For (1992) by Robert Peters is not only an outstanding guide for anyone contemplating graduate school – from the application process onward – but it also includes several excellent chapters on planning and executing research, applicable across a wide variety of subject areas. It was an invaluable resource for me 25 years ago, and it remains in print with good reason; I recommend it to all my students, particularly Chapter 16 (‘The Thesis Topic: Finding It’), Chapter 17 (‘The Thesis Proposal’) and Chapter 18 (‘The Thesis: Writing It’).

Meaning and the good life

How to appreciate what you have

To better face an imperfect world, try a deeper reflection on the things, people and legacies that make your life possible

by Avram Alpert

How to use ‘possibility thinking’

Have you hit an impasse in your personal or professional life? Answer these questions to open your mind to what’s possible

by Constance de Saint Laurent & Vlad Glăveanu

The nature of reality

How to think about time

This philosopher’s introduction to the nature of time could radically alter how you see your past and imagine your future

by Graeme A Forbes

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

What is Research: Definition, Methods, Types & Examples

The search for knowledge is closely linked to the object of study; that is, to the reconstruction of the facts that will provide an explanation to an observed event and that at first sight can be considered as a problem. It is very human to seek answers and satisfy our curiosity. Let’s talk about research.

Content Index

What is Research?

What are the characteristics of research.

- Comparative analysis chart

Qualitative methods

Quantitative methods, 8 tips for conducting accurate research.

Research is the careful consideration of study regarding a particular concern or research problem using scientific methods. According to the American sociologist Earl Robert Babbie, “research is a systematic inquiry to describe, explain, predict, and control the observed phenomenon. It involves inductive and deductive methods.”

Inductive methods analyze an observed event, while deductive methods verify the observed event. Inductive approaches are associated with qualitative research , and deductive methods are more commonly associated with quantitative analysis .

Research is conducted with a purpose to:

- Identify potential and new customers

- Understand existing customers

- Set pragmatic goals

- Develop productive market strategies

- Address business challenges

- Put together a business expansion plan

- Identify new business opportunities

- Good research follows a systematic approach to capture accurate data. Researchers need to practice ethics and a code of conduct while making observations or drawing conclusions.

- The analysis is based on logical reasoning and involves both inductive and deductive methods.

- Real-time data and knowledge is derived from actual observations in natural settings.

- There is an in-depth analysis of all data collected so that there are no anomalies associated with it.

- It creates a path for generating new questions. Existing data helps create more research opportunities.

- It is analytical and uses all the available data so that there is no ambiguity in inference.

- Accuracy is one of the most critical aspects of research. The information must be accurate and correct. For example, laboratories provide a controlled environment to collect data. Accuracy is measured in the instruments used, the calibrations of instruments or tools, and the experiment’s final result.

What is the purpose of research?

There are three main purposes:

- Exploratory: As the name suggests, researchers conduct exploratory studies to explore a group of questions. The answers and analytics may not offer a conclusion to the perceived problem. It is undertaken to handle new problem areas that haven’t been explored before. This exploratory data analysis process lays the foundation for more conclusive data collection and analysis.

LEARN ABOUT: Descriptive Analysis

- Descriptive: It focuses on expanding knowledge on current issues through a process of data collection. Descriptive research describe the behavior of a sample population. Only one variable is required to conduct the study. The three primary purposes of descriptive studies are describing, explaining, and validating the findings. For example, a study conducted to know if top-level management leaders in the 21st century possess the moral right to receive a considerable sum of money from the company profit.

LEARN ABOUT: Best Data Collection Tools

- Explanatory: Causal research or explanatory research is conducted to understand the impact of specific changes in existing standard procedures. Running experiments is the most popular form. For example, a study that is conducted to understand the effect of rebranding on customer loyalty.

Here is a comparative analysis chart for a better understanding:

It begins by asking the right questions and choosing an appropriate method to investigate the problem. After collecting answers to your questions, you can analyze the findings or observations to draw reasonable conclusions.

When it comes to customers and market studies, the more thorough your questions, the better the analysis. You get essential insights into brand perception and product needs by thoroughly collecting customer data through surveys and questionnaires . You can use this data to make smart decisions about your marketing strategies to position your business effectively.

To make sense of your study and get insights faster, it helps to use a research repository as a single source of truth in your organization and manage your research data in one centralized data repository .

Types of research methods and Examples

Research methods are broadly classified as Qualitative and Quantitative .

Both methods have distinctive properties and data collection methods .

Qualitative research is a method that collects data using conversational methods, usually open-ended questions . The responses collected are essentially non-numerical. This method helps a researcher understand what participants think and why they think in a particular way.

Types of qualitative methods include:

- One-to-one Interview

- Focus Groups

- Ethnographic studies

- Text Analysis

Quantitative methods deal with numbers and measurable forms . It uses a systematic way of investigating events or data. It answers questions to justify relationships with measurable variables to either explain, predict, or control a phenomenon.

Types of quantitative methods include:

- Survey research

- Descriptive research

- Correlational research

LEARN MORE: Descriptive Research vs Correlational Research

Remember, it is only valuable and useful when it is valid, accurate, and reliable. Incorrect results can lead to customer churn and a decrease in sales.

It is essential to ensure that your data is:

- Valid – founded, logical, rigorous, and impartial.

- Accurate – free of errors and including required details.

- Reliable – other people who investigate in the same way can produce similar results.

- Timely – current and collected within an appropriate time frame.

- Complete – includes all the data you need to support your business decisions.

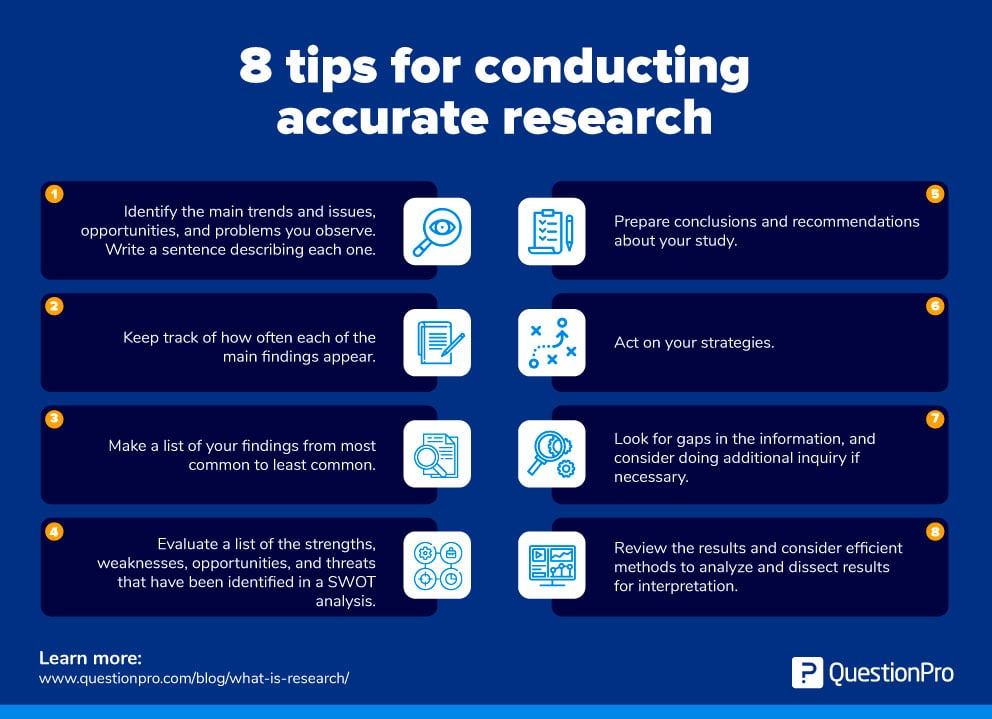

Gather insights

- Identify the main trends and issues, opportunities, and problems you observe. Write a sentence describing each one.

- Keep track of the frequency with which each of the main findings appears.

- Make a list of your findings from the most common to the least common.

- Evaluate a list of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats identified in a SWOT analysis .

- Prepare conclusions and recommendations about your study.

- Act on your strategies

- Look for gaps in the information, and consider doing additional inquiry if necessary

- Plan to review the results and consider efficient methods to analyze and interpret results.

Review your goals before making any conclusions about your study. Remember how the process you have completed and the data you have gathered help answer your questions. Ask yourself if what your analysis revealed facilitates the identification of your conclusions and recommendations.

LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR SOFTWARE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Taking Action in CX – Tuesday CX Thoughts

Apr 30, 2024

QuestionPro CX Product Updates – Quarter 1, 2024

Apr 29, 2024

NPS Survey Platform: Types, Tips, 11 Best Platforms & Tools

Apr 26, 2024

User Journey vs User Flow: Differences and Similarities

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Get started

- Project management

- CRM and Sales

- Work management

- Product development life cycle

- Comparisons

- Construction management

- monday.com updates

The value of a good research plan

A research plan is a guiding framework that can make or break the efficiency and success of your research project. Oftentimes teams avoid them because they’ve earned a reputation as a dry or actionless document — however, this doesn’t have to be the case.

In this article, we’ll go over the most important aspects of a good research plan and show you how they can be visual and actionable with monday.com Work OS.

Don’t miss more quality content!

Why is the research plan pivotal to a research project.

A research plan is pivotal to a research project because it identifies and helps define your focus, method, and goals while also outlining the research project from start to finish.

This type of plan is often necessary to:

- Apply for grants or internal company funding.

- Discover possible research partners or business partners.

- Take your research from an idea into reality.

It will also control the entire journey of the research project through every stage by defining crucial research questions and the hypothesis (theory) that you’ll strive to prove or disprove.

What goes into a research plan?

The contents of a thorough research plan should include a hypothesis, methodology, and more. There is some variation between academic and commercial research, but these are common elements:

- Hypothesis: the problem you are trying to solve and the basis for a theoretical solution. For example, if I reduce my intake of calories, I’ll lose weight.

- Research questions: research questions help guide your investigation into particular issues. If you were looking into the potential impact of outsourcing production, you might ask something like: how would outsourcing impact our production costs?

- Research method: the method you’ll use to get the data for your research. For example, a case study, survey, interviews, a clinical trial, or user tests.

- Definitions: a glossary for the research plan, explaining the terminology that you use throughout the document.

- Conceptual frameworks: a conceptual framework helps illustrate what you think you’ll discover with your research. In a sense, it’s a visual representation of a more complex hypothesis.

For commercial plans, there will also likely be a budget and timeline estimate, as well as concrete hypothetical benefits for the company (such as how much money the project should save you).

OK, so you’ve got a handle on the building blocks of a research plan, but how should you actually write it?