JavaScript seems to be disabled in your browser. For the best experience on our site, be sure to turn on Javascript in your browser.

Explore the Levels of Change Management

Culture and Change Management: The Water We Swim In

Updated: March 2, 2024

Published: March 29, 2023

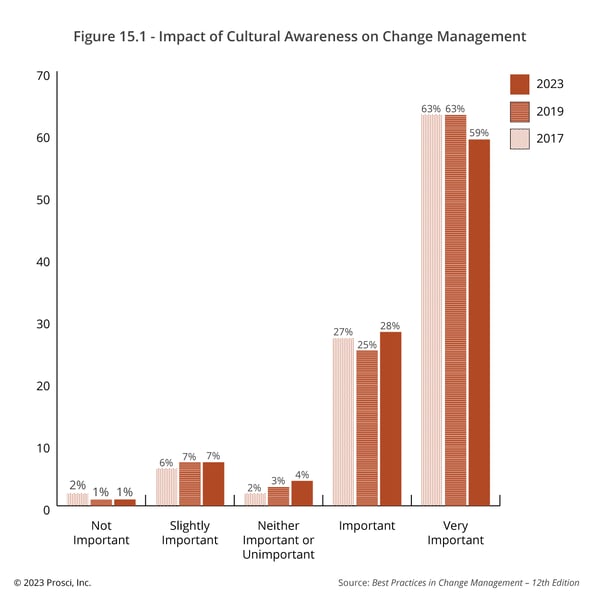

Culture has a huge impact on our change management projects. Our Best Practices in Change Management research reveals that 88% of participants find cultural awareness to be important or very important to a change management initiative. Being culturally aware enables change practitioners to customize their change management approach, apply culturally specific adaptations while avoiding culturally specific obstacles, and create effective communication plans with the culture of the audience in mind.

Impact of Cultural Awareness on Change

Explore the latest change management data and insights, and our new interactive dashboards, in the Best Practices in Change Management - 12th Edition Executive Summary.

Culture and Change Management

"Culture is to humans as water is to fish." This popular saying likely emerged from a story from writer David Foster Wallace, describing how the most important and obvious things can be difficult to see and articulate. A fish lives its entire life swimming through water, without knowing what water is. We humans live our lives moving through a culture, which impacts us myriad ways without always making itself known.

Change management is most effective when practitioners acknowledge and understand the cultural context of impacted employee groups and apply that understanding to their approaches. Prosci's Best Practices in Change Management research offers an in-depth look at this topic, offering helpful benchmarks for challenges and adaptations based on cultural considerations.

Our first challenge in working with our own culture and others is to recognize its impact. For example, different cultures view and interact with work relationships differently. Activities and trainings may need to be adapted to culture-specific standards, and communications might need to be customized for different cultural settings.

Anthropologists, intercultural communication professionals, and cultural scholars have been using "cultural dimensions" to study various cultures for years. In doing so, they created a language and framework to help us describe culture. Our research builds on the works of Hofstede, Trompenaars, Hampden-Turner and others, and works such as the 1980 Culture and Consequences, 2004 Globe Study, and 1997 Riding the Waves of Culture.

Cultural Dimensions and Change

Cultural dimensions are characteristic spectra that exist in a culture. For example, assertiveness is a dimension that describes the degree to which a person is able and expected to advocate for their personal well-being and goals in their relationships with others.

At one end of the spectrum, organizations with low assertiveness communicate in indirect, subtle ways, often practicing passive, face-saving communication with an expectation that subordinates will loyally follow executives’ leads.

At the other end of the spectrum, communication tends to be assertive to the point of being aggressive or confrontational. Communication is direct, delivered in a blunt, unambiguous manner, and subordinates are expected to take initiative during interactions with executives.

These are extremes, but identifying your location on the spectrum of assertiveness helps to highlight potential challenges and adaptations. In a low-assertiveness culture, for example, feedback may be very unreliable as individuals are likely to shy away from difficult, honest messages out of fear of upsetting recipients. This ambiguous communication then forces others to make educated guesses rather than base their adjustments and customizations on accurate feedback. Knowing these challenges in this specific cultural setting, you can take steps to encourage honest, direct feedback that provides important information.

In high-assertiveness cultures, we might see extreme resistance expressed vocally. Individuals who dislike the change initiative might bluntly refuse to adopt the changes and actively encourage others to do the same. Too much feedback may also slow project execution. If you can predict this strong response, you can identify potential sources of resistant behaviors and plan for resistance prevention. Clearly, understanding your position on the cultural assertiveness spectrum is helpful.

Of course, these examples don't represent how every individual in a culture behaves. But they do demonstrate a culture’s expectations and beliefs.

Think of these cultural dimensions as lenses that reveal the inner workings of a culture—information we can then use to enhance and improve the effectiveness of our change management efforts .

Culture and Change Management Work

Prosci's Best Practices in Change Management research identifies the cultural dimensions that have the largest impact on change management:

- Assertiveness

- Individualism versus collectivism

- Emotional expressiveness

- Power distance

- Performance orientation

- Uncertainty avoidance

We asked participants to place their organization's culture on each cultural spectra (from extremely low to extremely high). Then we asked them what specific challenges they faced in their change management work due to that placement on each cultural dimension. And finally, we asked what adaptations they would make to address the challenges. You can find this data in our Best Practices research , where we list data and scores by region and industry.

To explain how understanding your specific culture can help your change management work, let's explore power distance, or the extent to which people with lower levels of authority accept the unequal distribution of authority in an organization.

In low power-distance cultures, there is little formal structure or hierarchical separation. Employees have access to higher-level members, expect that all voices will be heard, and expect that company-wide decisions will be made democratically. In this cultural setting, participants identified the challenges they faced and the adaptations they made:

- Extensive access meant communication messages often skipped levels within the organization, causing messages to be repeated multiple times

- Individuals from all levels of the organization felt free to challenge and question the change project

- The increased time required to gain commitment and support led to a decrease in productivity

Adaptations

- Increased the number of meetings, engagement activities and functions designed to ensure alignment with the project

- Created structured communication channels to customize messages and allow for employee feedback

- Placed stakeholders in key positions, established communication guidelines, and clearly defined roles to enhance the overall change management plan

3 Ways to Put Cultural Insights Into Practice

Although gaining insight is a great first step, the real value comes from applying your understanding of culture to achieve positive results in change initiatives. Here’s how to use the research to enhance your work.

1. Understand the landscape you're working in

Consider where the impacted individuals fall on each of the six spectra. If you are managing a change that will impact individuals in different cultures, take time to understand and appreciate each of the cultures that will be impacted, how they differ from one another, and how you can alter your approach for each audience .

2. Evaluate your cultural lens

Understand where your home culture sits on the cultural spectra and how your personal paradigm may differ from the culture in which you are managing change. This will help you to better understand how you can interact with and work with other cultures. We don't want to leave our individual cultures behind, but as global change professionals , we must understand how that lens impacts our work.

3. Adapt your approach

If we do not adapt our approach and take culture into account, we can find ourselves trying to hammer a square peg into a round hole. Find the most culturally relevant ways to communicate about the change, and then implement the activities that will have the greatest impact with your audience.

Culture and the People Side of Change

Remember, culture is to humans as water is to fish. It is critically important to keep this in mind when our work centers on helping people change. When we begin to understand culture in a meaningful, tangible way, we have a choice. Do we want to remain blind to the cultural forces at work in the organizations we’re trying to impact? Or do we want to harness those forces to improve our change work, our results, and the experiences of those around us?

Founded in 1994, Prosci is a global leader in change management. We enable organizations around the world to achieve change outcomes and grow change capability through change management solutions based on holistic, research-based, easy-to-use tools, methodologies and services.

See all posts from Prosci

You Might Also Like

Enterprise - 5 MINS

Cultural Awareness in Global Change Management: Regional Differences

Building a Global Change Ambassador Network at Matthews International

Subscribe here.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The Most Successful Approaches to Leading Organizational Change

- Deborah Rowland,

- Michael Thorley,

- Nicole Brauckmann

A closer look at four distinct ways to drive transformation.

When tasked with implementing large-scale organizational change, leaders often give too much attention to the what of change — such as a new organization strategy, operating model or acquisition integration — not the how — the particular way they will approach such changes. Such inattention to the how comes with the major risk that old routines will be used to get to new places. Any unquestioned, “default” approach to change may lead to a lot of busy action, but not genuine system transformation. Through their practice and research, the authors have identified the optimal ways to conceive, design, and implement successful organizational change.

Management of long-term, complex, large-scale change has a reputation of not delivering the anticipated benefits. A primary reason for this is that leaders generally fail to consider how to approach change in a way that matches their intent.

- Deborah Rowland is the co-author of Sustaining Change: Leadership That Works , Still Moving: How to Lead Mindful Change , and the Still Moving Field Guide: Change Vitality at Your Fingertips . She has personally led change at Shell, Gucci Group, BBC Worldwide, and PepsiCo and pioneered original research in the field, accepted as a paper at the 2016 Academy of Management and the 2019 European Academy of Management. Thinkers50 Radar named as one of the generation of management thinkers changing the world of business in 2017, and she’s on the 2021 HR Most Influential Thinker list. She is Cambridge University 1st Class Archaeology & Anthropology Graduate.

- Michael Thorley is a qualified accountant, psychotherapist, executive psychological coach, and coach supervisor integrating all modalities to create a unique approach. Combining his extensive experience of running P&L accounts and developing approaches that combine “hard”-edged and “softer”-edged management approaches, he works as a non-executive director and advisor to many different organizations across the world that wish to generate a new perspective on change.

- Nicole Brauckmann focuses on helping organizations and individuals create the conditions for successful emergent change to unfold. As an executive and consultant, she has worked to deliver large-scale complex change across different industries, including energy, engineering, financial services, media, and not-for profit. She holds a PhD at Faculty of Philosophy, Westfaelische Wilhelms University Muenster and spent several years on academic research and teaching at University of San Diego Business School.

Partner Center

The four building blocks of change

Large-scale organizational change has always been difficult, and there’s no shortage of research showing that a majority of transformations continue to fail. Today’s dynamic environment adds an extra level of urgency and complexity. Companies must increasingly react to sudden shifts in the marketplace, to other external shocks, and to the imperatives of new business models. The stakes are higher than ever.

So what’s to be done? In both research and practice, we find that transformations stand the best chance of success when they focus on four key actions to change mind-sets and behavior: fostering understanding and conviction, reinforcing changes through formal mechanisms, developing talent and skills, and role modeling. Collectively labeled the “influence model,” these ideas were introduced more than a dozen years ago in a McKinsey Quarterly article, “ The psychology of change management .” They were based on academic research and practical experience—what we saw worked and what didn’t.

Digital technologies and the changing nature of the workforce have created new opportunities and challenges for the influence model (for more on the relationship between those trends and the model, see this article’s companion, “ Winning hearts and minds in the 21st century ”). But it still works overall, a decade and a half later (exhibit). In a recent McKinsey Global Survey, we examined successful transformations and found that they were nearly eight times more likely to use all four actions as opposed to just one. 1 1. See “ The science of organizational transformations ,” September 2015. Building both on classic and new academic research, the present article supplies a primer on the model and its four building blocks: what they are, how they work, and why they matter.

Fostering understanding and conviction

We know from research that human beings strive for congruence between their beliefs and their actions and experience dissonance when these are misaligned. Believing in the “why” behind a change can therefore inspire people to change their behavior. In practice, however, we find that many transformation leaders falsely assume that the “why” is clear to the broader organization and consequently fail to spend enough time communicating the rationale behind change efforts.

This common pitfall is predictable. Research shows that people frequently overestimate the extent to which others share their own attitudes, beliefs, and opinions—a tendency known as the false-consensus effect. Studies also highlight another contributing phenomenon, the “curse of knowledge”: people find it difficult to imagine that others don’t know something that they themselves do know. To illustrate this tendency, a Stanford study asked participants to tap out the rhythms of well-known songs and predict the likelihood that others would guess what they were. The tappers predicted that the listeners would identify half of the songs correctly; in reality, they did so less than 5 percent of the time. 2 2. Chip Heath and Dan Heath, “The curse of knowledge,” Harvard Business Review , December 2006, Volume 8, Number 6, hbr.org.

Therefore, in times of transformation, we recommend that leaders develop a change story that helps all stakeholders understand where the company is headed, why it is changing, and why this change is important. Building in a feedback loop to sense how the story is being received is also useful. These change stories not only help get out the message but also, recent research finds, serve as an effective influencing tool. Stories are particularly effective in selling brands. 3 3. Harrison Monarth, “The irresistible power of storytelling as a strategic business tool,” Harvard Business Review , March 11, 2014, hbr.org.

Even 15 years ago, at the time of the original article, digital advances were starting to make employees feel involved in transformations, allowing them to participate in shaping the direction of their companies. In 2006, for example, IBM used its intranet to conduct two 72-hour “jam sessions” to engage employees, clients, and other stakeholders in an online debate about business opportunities. No fewer than 150,000 visitors attended from 104 countries and 67 different companies, and there were 46,000 posts. 4 4. Icons of Progress , “A global innovation jam,” ibm.com. As we explain in “Winning hearts and minds in the 21st century,” social and mobile technologies have since created a wide range of new opportunities to build the commitment of employees to change.

Reinforcing with formal mechanisms

Psychologists have long known that behavior often stems from direct association and reinforcement. Back in the 1920s, Ivan Pavlov’s classical conditioning research showed how the repeated association between two stimuli—the sound of a bell and the delivery of food—eventually led dogs to salivate upon hearing the bell alone. Researchers later extended this work on conditioning to humans, demonstrating how children could learn to fear a rat when it was associated with a loud noise. 5 5. John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner, “Conditioned emotional reactions,” Journal of Experimental Psychology , 1920, Volume 3, Number 1, pp. 1–14. Of course, this conditioning isn’t limited to negative associations or to animals. The perfume industry recognizes how the mere scent of someone you love can induce feelings of love and longing.

Reinforcement can also be conscious, shaped by the expected rewards and punishments associated with specific forms of behavior. B. F. Skinner’s work on operant conditioning showed how pairing positive reinforcements such as food with desired behavior could be used, for example, to teach pigeons to play Ping-Pong. This concept, which isn’t hard to grasp, is deeply embedded in organizations. Many people who have had commissions-based sales jobs will understand the point—being paid more for working harder can sometimes be a strong incentive.

Despite the importance of reinforcement, organizations often fail to use it correctly. In a seminal paper “On the folly of rewarding A, while hoping for B,” management scholar Steven Kerr described numerous examples of organizational-reward systems that are misaligned with the desired behavior, which is therefore neglected. 6 6. Steven Kerr, “On the folly of rewarding A, while hoping for B,” Academy of Management Journal , 1975, Volume 18, Number 4, pp. 769–83. Some of the paper’s examples—such as the way university professors are rewarded for their research publications, while society expects them to be good teachers—are still relevant today. We ourselves have witnessed this phenomenon in a global refining organization facing market pressure. By squeezing maintenance expenditures and rewarding employees who cut them, the company in effect treated that part of the budget as a “super KPI.” Yet at the same time, its stated objective was reliable maintenance.

Even when organizations use money as a reinforcement correctly, they often delude themselves into thinking that it alone will suffice. Research examining the relationship between money and experienced happiness—moods and general well-being—suggests a law of diminishing returns. The relationship may disappear altogether after around $75,000, a much lower ceiling than most executives assume. 7 7. Belinda Luscombe, “Do we need $75,000 a year to be happy?” Time , September 6, 2010, time.com.

Would you like to learn more about our People & Organizational Performance Practice ?

Money isn’t the only motivator, of course. Victor Vroom’s classic research on expectancy theory explained how the tendency to behave in certain ways depends on the expectation that the effort will result in the desired kind of performance, that this performance will be rewarded, and that the reward will be desirable. 8 8. Victor Vroom, Work and motivation , New York: John Wiley, 1964. When a Middle Eastern telecommunications company recently examined performance drivers, it found that collaboration and purpose were more important than compensation (see “Ahead of the curve: The future of performance management,” forthcoming on McKinsey.com). The company therefore moved from awarding minor individual bonuses for performance to celebrating how specific teams made a real difference in the lives of their customers. This move increased motivation while also saving the organization millions.

How these reinforcements are delivered also matters. It has long been clear that predictability makes them less effective; intermittent reinforcement provides a more powerful hook, as slot-machine operators have learned to their advantage. Further, people react negatively if they feel that reinforcements aren’t distributed fairly. Research on equity theory describes how employees compare their job inputs and outcomes with reference-comparison targets, such as coworkers who have been promoted ahead of them or their own experiences at past jobs. 9 9. J. S. Adams, “Inequity in social exchanges,” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology , 1965, Volume 2, pp. 267–300. We therefore recommend that organizations neutralize compensation as a source of anxiety and instead focus on what really drives performance—such as collaboration and purpose, in the case of the Middle Eastern telecom company previously mentioned.

Developing talent and skills

Thankfully, you can teach an old dog new tricks. Human brains are not fixed; neuroscience research shows that they remain plastic well into adulthood. Illustrating this concept, scientific investigation has found that the brains of London taxi drivers, who spend years memorizing thousands of streets and local attractions, showed unique gray-matter volume differences in the hippocampus compared with the brains of other people. Research linked these differences to the taxi drivers’ extraordinary special knowledge. 10 10. Eleanor Maguire, Katherine Woollett, and Hugo Spires, “London taxi drivers and bus drivers: A structural MRI and neuropsychological analysis,” Hippocampus , 2006, Volume 16, pp. 1091–1101.

Despite an amazing ability to learn new things, human beings all too often lack insight into what they need to know but don’t. Biases, for example, can lead people to overlook their limitations and be overconfident of their abilities. Highlighting this point, studies have found that over 90 percent of US drivers rate themselves above average, nearly 70 percent of professors consider themselves in the top 25 percent for teaching ability, and 84 percent of Frenchmen believe they are above-average lovers. 11 11. The art of thinking clearly, “The overconfidence effect: Why you systematically overestimate your knowledge and abilities,” blog entry by Rolf Dobelli, June 11, 2013, psychologytoday.com. This self-serving bias can lead to blind spots, making people too confident about some of their abilities and unaware of what they need to learn. In the workplace, the “mum effect”—a proclivity to keep quiet about unpleasant, unfavorable messages—often compounds these self-serving tendencies. 12 12. Eliezer Yariv, “‘Mum effect’: Principals’ reluctance to submit negative feedback,” Journal of Managerial Psychology , 2006, Volume 21, Number 6, pp. 533–46.

Even when people overcome such biases and actually want to improve, they can handicap themselves by doubting their ability to change. Classic psychological research by Martin Seligman and his colleagues explained how animals and people can fall into a state of learned helplessness—passive acceptance and resignation that develops as a result of repeated exposure to negative events perceived as unavoidable. The researchers found that dogs exposed to unavoidable shocks gave up trying to escape and, when later given an opportunity to do so, stayed put and accepted the shocks as inevitable. 13 13. Martin Seligman and Steven Maier, “Failure to escape traumatic shock,” Journal of Experimental Psychology , 1967, Volume 74, Number 1, pp. 1–9. Like animals, people who believe that developing new skills won’t change a situation are more likely to be passive. You see this all around the economy—from employees who stop offering new ideas after earlier ones have been challenged to unemployed job seekers who give up looking for work after multiple rejections.

Instilling a sense of control and competence can promote an active effort to improve. As expectancy theory holds, people are more motivated to achieve their goals when they believe that greater individual effort will increase performance. 14 14. Victor Vroom, Work and motivation , New York: John Wiley, 1964. Fortunately, new technologies now give organizations more creative opportunities than ever to showcase examples of how that can actually happen.

Role modeling

Research tells us that role modeling occurs both unconsciously and consciously. Unconsciously, people often find themselves mimicking the emotions, behavior, speech patterns, expressions, and moods of others without even realizing that they are doing so. They also consciously align their own thinking and behavior with those of other people—to learn, to determine what’s right, and sometimes just to fit in.

While role modeling is commonly associated with high-power leaders such as Abraham Lincoln and Bill Gates, it isn’t limited to people in formal positions of authority. Smart organizations seeking to win their employees’ support for major transformation efforts recognize that key opinion leaders may exert more influence than CEOs. Nor is role modeling limited to individuals. Everyone has the power to model roles, and groups of people may exert the most powerful influence of all. Robert Cialdini, a well-respected professor of psychology and marketing, examined the power of “social proof”—a mental shortcut people use to judge what is correct by determining what others think is correct. No wonder TV shows have been using canned laughter for decades; believing that other people find a show funny makes us more likely to find it funny too.

Today’s increasingly connected digital world provides more opportunities than ever to share information about how others think and behave. Ever found yourself swayed by the number of positive reviews on Yelp? Or perceiving a Twitter user with a million followers as more reputable than one with only a dozen? You’re not imagining this. Users can now “buy followers” to help those users or their brands seem popular or even start trending.

The endurance of the influence model shouldn’t be surprising: powerful forces of human nature underlie it. More surprising, perhaps, is how often leaders still embark on large-scale change efforts without seriously focusing on building conviction or reinforcing it through formal mechanisms, the development of skills, and role modeling. While these priorities sound like common sense, it’s easy to miss one or more of them amid the maelstrom of activity that often accompanies significant changes in organizational direction. Leaders should address these building blocks systematically because, as research and experience demonstrate, all four together make a bigger impact.

Tessa Basford is a consultant in McKinsey’s Washington, DC, office; Bill Schaninger is a director in the Philadelphia office.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Winning hearts and minds in the 21st century

Changing change management

Digital hives: Creating a surge around change

About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets & Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Social Impact

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Services

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

How to Get Beyond Talk of “Culture Change” and Make It Happen

Experts outline their roadmap for intentionally changing the culture of businesses, social networks, and beyond.

February 20, 2024

Calls for cultural transformation have become ubiquitous in the past few years, encompassing everything from advancing racial justice and questioning gender roles to rethinking the American workplace. Hazel Rose Markus recalls the summer of 2020 as a watershed for those conversations. “Everybody was saying, ‘Oh, the culture has to change,’” says Markus, a professor of psychology at Stanford. “It was just rolling off everybody’s lips in every domain.” Yet no one seemed to know what exactly that might entail or how to get started.

As they followed these discussions, Markus and her colleagues Jennifer Eberhardt and MarYam Hamedani wondered what they could contribute at this moment as experts with years of experience studying how communities and organizations can turn the desire for change into something real. “Culture is all around us, but at the same time, it feels out of reach for a lot of people,” says Eberhardt, a professor of organizational behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business and of psychology in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

Markus and Eberhardt are the faculty co-directors of Stanford SPARQ , a “do tank” that brings researchers and practitioners together to apply the lessons of behavioral science to combating bias and disparities; Hamedani is its executive director and senior research scientist. Recently, along with associate director of criminal justice partnerships Rebecca Hetey , they published an evidence-based roadmap to intentional cultural change in American Psychologist . They hope, Hamedani says, to illustrate “a path forward and to make the claim that culture change is possible.”

Stanford Business spoke with Eberhardt, Hamedani, and Markus to discuss the complexities of changing a culture and how leaders and readers who are committed to doing things differently can get started.

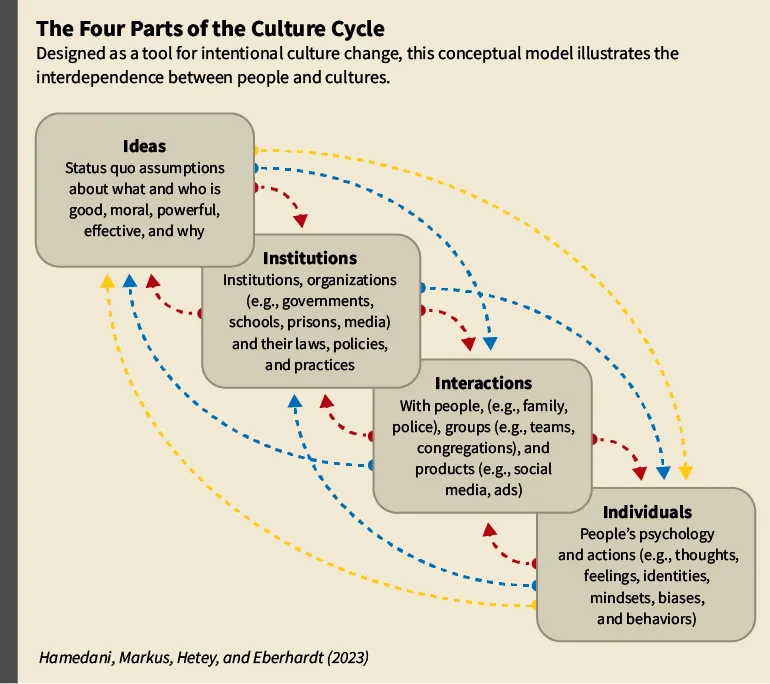

You start the paper with the “four I’s,” categories you believe can help people map their cultures and see where there might be tensions or mismatches. Using organizational cultures as an example, can you take us through those?

Hazel Rose Markus: There are the ideas , the big ideologies that are foundational for any organization: This is how we do things, what’s good, and what we value. Then the institutional parts, which are the everyday policies and practices that people use to do their work. Often, those have been in place for a long time and people tend to follow them as if they were the natural order of things. Another I is the interactions, which have to do with what’s going on in the office every day, in your relationships with your colleagues, with the people you supervise, with those you answer to. And finally, the fourth part is your own individual attitudes, feelings, and actions.

Is there a way to sum up your roadmap for changing culture?

MarYam Hamedani: The first key idea is because we built it, we can change it. There are many forces out there that are out of our control, but the societies we build and pass on — the organizations, the institutions, the way we live our lives — those are things that are human-made. And so we should feel empowered by that inheritance because that’s the thing that gives us the ability to make change.

The second part is that culture change usually involves a series of power struggles and clashes and divides. You have different groups that feel like they’re winning and losing. There’s a lot at stake for people. It’s important to try to have strategies to deal with that.

Finally, culture change can be unpredictable and have unintended consequences. Yet the dynamics can also follow patterns — for example, backlash happens. Timing matters. So you have to be nimble; you have to realize that cultural change never ends. It’s a sustainable process that you have to stay on top of, and that’s OK.

Markus: Yes, changemakers can’t be discouraged when they see backlash. Also, we want to help people remember that yes, they are individuals, but they are also making culture through their actions. How our everyday actions can contribute to a larger culture and to its change is something I think we are less likely to think about in our individualistic system.

Hamedani: Right. We are individuals and in charge of our own behavior, but then we are powerful as a group.

Markus: With each other, what are we modeling? What are we putting our efforts behind? What’s the impact on the workplace?

Your paper was written with the problem of social inequality in mind. What message does it have for business leaders?

Jennifer Eberhardt: As business leaders, you have both a lot of power and, I think, a lot of obligation to understand the workings of culture. You have the power to pull the levers of change. You dictate what the social environment is like for everyone else. So you have a heavy hand in creating and sustaining the culture that is there — but you can also have a heavy hand in changing that culture for the better.

Markus: When culture change is on the agenda, you often hear leaders — like those in the tech industry — and the first thing they often say is, “OK, I’m going on a listening tour.” But you rarely hear about what they’re going to listen for or what they heard from those who report to them or how they’re going to put that into action.

Listening is valuable because it conveys empathy, but it is useful to listen specifically for what people understand as the important values of our organization, the undergirding ideas. What are we about? What are we trying to be as an organization? And, very importantly, do our policies and practices reflect these ideas and values and our mission? We can say we’re about one thing or another, but how is it materialized? How does it show up in our everyday work? Is there a general alignment across the four I’s of the culture?

You worked with Nextdoor on a project to change its culture. How did that go?

Eberhardt: They reached out to me and other researchers trying to figure out how to curb racial profiling on their platform. In the tech industry, people are focused on building products that are easy to use, products that are intuitive, so that users don’t really have to think too hard. But those are also conditions under which racial bias might thrive. So we encouraged them to slow users down, to increase friction rather than trying to take friction away.

Quote As business leaders, you have both a lot of power and, I think, a lot of obligation to understand the workings of culture. You have the power to pull the levers of change. Attribution Jennifer Eberhardt

They accomplished this by creating a checklist for users to review before posting on a Nextdoor forum. The first thing they ask people to consider is that a person’s race is not an indication of their criminal activity. And also when they describe a person, you don’t just describe their race, you describe their behavior. What are they doing that seems suspicious? Nextdoor found that just simply slowing people down in this way, based on these social psychological principles, they were able to reduce profiling by over 75%.

They were trying to solve for something at the interaction level. What they could change was what the experience was like for users at the institutional level. Just by making these simple tweaks to the platform itself and how they presented information, they changed these negative interactions that were taking place that then could also shape people’s ideas about race.

You also talk in the paper about the example of investment firms struggling to become more diverse.

Markus: Typically this has been the territory of white men with economics degrees from Harvard, Yale, Stanford, Princeton. It was a closed and locked world. In studies we did in the investing domain, we found that race can influence professional investors’ financial judgments. Many people in the industry would like to create a culture that is more open and inclusive, but there is a powerful default assumption at work that acts as a barrier. In a lot of these firms, the default is still, “I know in my gut what a successful idea is and who is likely to build a company that can grow. I can see it and feel it, and either you match or you don’t match.”

It seems like a point of tension where the institutional level says it wants change, but at the interaction level, this is still a relationship-driven industry. So what do you do about that?

Hamedani: It depends where in the culture map you want to start. Let’s say you diversify the students coming in and getting MBAs. Then you have to look at how are they’re being mentored and supported through their schooling experience, through the internships and job opportunities that they have. Are you simply assuming that they should assimilate to the default? Are you training a new, exciting, and diverse group of people to act like those that have been there all along? Or are you incorporating their ideas and diverse ways of being that might look or sound different and affording them the same respect and status? Are you teaching them how to do a pitch a certain way because there’s only one right way to do a pitch? Or might they have other styles of communication or ways of selling an idea?

At the GSB, Jennifer has a class, Racial Bias and Structural Inequality , where she brings in all these amazing CEOs who are women and people of color. Most of the students, they’ve never seen it before. And that’s what happens to people in these investment firms: They haven’t seen it before. Even that intervention of seeing, week after week, these leaders coming in and the students get to ask them questions and have a conversation with them — that’s an interaction .

Eberhardt: I had Sarah Friar , MBA ’00, the CEO of Nextdoor, come in. I had the president of Black Entertainment Television, Scott Mills , come in; I had the police chief of San Francisco, William Scott , come in — they are both African American.

And the hope is that these students who will go on to work in the business world will have a broader definition of what is a “culture fit”?

Hamedani: Exactly right. And more specifically, a “leader fit.” And for women and students of color, that they can also see themselves as leaders. But it takes things happening at all levels in the culture map to make that happen. You’re seeding this change and then the levels are reinforcing each other to help it grow.

What would you recommend as a starting place for readers who are thinking that they want to spark intentional cultural change wherever they are?

Markus: It would begin with mapping the culture: What matters to us, what do we value? And then, to the extent that there’s some consensus about our culture, reflecting on whether our ways of doing things reflect this. In so many organizations we’re working with now, there’s really a gap between what leaders feel their values are, what they care about, and what the employees are experiencing. What we see is that it’s important to give the employees chances to get together to talk about this and have some company time, some paid time, to discuss these issues —

Hamedani: — to vision the future. Because there’s that virtue signaling, “OK, we care about that, but really we’re so busy and we have all these things to do. We have to hit our targets for the quarter or for the year.” Of course, those things are important, but are people — employees and leaders alike — participating in visioning that future and laying out the goals and objectives together? Can you make some small or even larger changes such that people feel empowered that they’re part of building that culture together?

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom .

Explore More

Conflict among hospital staff could compromise care, hardwired for hierarchy: our relationship with power, taking a stand with your brand: genderless fashion in africa, editor’s picks.

We Built This Culture (so We Can Change It): Seven Principles for Intentional Culture Change MarYam G. Hamedani Hazel Rose Markus Rebecca C. Hetey Jennifer Eberhardt

May 30, 2023 Will a Police Stop End in Arrest? Listen to Its First 27 Seconds. Researchers have identified a linguistic signature that can predict whether encounters with cops will escalate. Black drivers hear this pattern as well.

August 01, 2023 Follow the Leader: How a CEO’s Personality Is Reflected in Their Company’s Culture There’s no ideal personality type for executives — but businesses need the right one for success.

- Priorities for the GSB's Future

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Business Transformation

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships and Prizes

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Get Involved

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- Career Advancement

- Career Change

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- Information for Recommenders

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- After You’re Admitted

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- Videos, Code & Data

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Marketing Camp

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Reading Materials

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

- Founding Donors

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Program Contacts

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

Reshaping Organizational Culture: a Comprehensive Approach to Change Management

This essay about the transformative dynamics of organizational culture underscores its pivotal role in shaping the destiny of contemporary enterprises. With a focus on resilience and adaptability, the text navigates through the intricate ballet of cultural change, emphasizing the indispensable commitment of leadership. Effective communication, inclusivity, and collaboration emerge as vital threads, weaving a tapestry that invites employee participation in the metamorphosis. The essay highlights the importance of training, policy alignment, and tangible metrics, presenting them as integral components for cultivating a positive organizational culture. In essence, the text positions cultural transformation as an ongoing process, demanding adaptability and responsiveness for organizations to thrive on the frontier of innovation and unparalleled success.

How it works

In the intricate dance of the contemporary corporate world, the spotlight is increasingly turning towards the central role that organizational culture plays in shaping an enterprise’s destiny. A resilient and adaptive culture is akin to the lifeblood that fuels innovation, sparks employee engagement, and propels overall organizational efficacy. Yet, the endeavor to reshape organizational culture is a formidable challenge, demanding a nuanced and strategic approach to change management.

At its core, the transformation process hinges on the realization that organizational culture is a living entity, constantly morphing under the influences of leadership, employee dynamics, and external forces.

Acknowledging the need for change is merely the opening act; what follows is an intricate ballet requiring deliberate and all-encompassing moves.

Central to this transformative symphony is the unwavering commitment of leadership. Leaders must not merely endorse change; they must embody the very cultural traits they seek to instill. Their actions and decisions serve as the rudder steering the organization towards the desired cultural shores, creating an environment where employees are not just bystanders but active participants in the metamorphosis.

A vital thread in this transformative tapestry is effective communication. Openness and transparency become the conduits through which the reasons for cultural recalibration, anticipated outcomes, and individual roles in the transformation are articulated. Regular updates, town hall meetings, and mechanisms for feedback weave a sense of inclusion and shared purpose, dismantling resistance to the impending cultural shift.

Equally crucial is the democratization of the change process. Cultural transformation is not a hierarchical decree; it thrives when inclusivity and collaboration take center stage. Seeking input from employees becomes a mosaic of insights that not only reflects the current cultural landscape but also becomes the raw material for co-creating the envisioned culture. This collaborative approach fosters a sense of ownership, weaving a collective commitment to the organizational evolution.

The cadence of this transformation is further enriched through investment in training and development initiatives. This goes beyond the conventional skill enhancement paradigm; it embraces a culture of perpetual learning, adaptability, and resilience. Nurturing employee growth and well-being becomes the fertilizer for cultivating a positive organizational culture, reinforcing the notion that individual contributions are integral to the organization’s collective triumph.

In the labyrinth of organizational dynamics, policies and practices emerge as signposts that guide or hinder cultural transformation. An overhaul, if necessary, of existing structures, processes, and performance metrics ensures that the organizational heartbeat resonates with the desired values and behaviors.

Integral to this orchestration is the harmonizing of cultural change with tangible metrics. Key performance indicators (KPIs) become the scorecard against which progress is measured, stumbling blocks are identified, and victories are celebrated. Regular assessments, surveys, and feedback loops provide the sheet music that directs the ongoing refinement of the symphony of change.

In essence, cultural transformation is a perpetual journey rather than a final destination. It necessitates not only adaptability but also a receptiveness to learning from both triumphs and setbacks. Organizations must embody agility and responsiveness, adjusting their strategies as the voyage through unforeseen challenges unfolds.

In conclusion, the endeavor to reshape organizational culture requires a comprehensive, adaptive, and artful approach to change management. Leadership commitment, transparent communication, inclusive collaboration, dynamic training, policy alignment, and continual measurement converge to create a unique composition for cultural transformation. By embracing this intricate strategy, organizations position themselves not only to weather the storms but also to dance on the cutting edge of innovation, with a culture that not only endures but propels them towards unparalleled success.

Cite this page

Reshaping Organizational Culture: A Comprehensive Approach to Change Management. (2024, Mar 12). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/reshaping-organizational-culture-a-comprehensive-approach-to-change-management/

"Reshaping Organizational Culture: A Comprehensive Approach to Change Management." PapersOwl.com , 12 Mar 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/reshaping-organizational-culture-a-comprehensive-approach-to-change-management/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Reshaping Organizational Culture: A Comprehensive Approach to Change Management . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/reshaping-organizational-culture-a-comprehensive-approach-to-change-management/ [Accessed: 14 Apr. 2024]

"Reshaping Organizational Culture: A Comprehensive Approach to Change Management." PapersOwl.com, Mar 12, 2024. Accessed April 14, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/reshaping-organizational-culture-a-comprehensive-approach-to-change-management/

"Reshaping Organizational Culture: A Comprehensive Approach to Change Management," PapersOwl.com , 12-Mar-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/reshaping-organizational-culture-a-comprehensive-approach-to-change-management/. [Accessed: 14-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Reshaping Organizational Culture: A Comprehensive Approach to Change Management . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/reshaping-organizational-culture-a-comprehensive-approach-to-change-management/ [Accessed: 14-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- *New* Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

5 Critical Steps in the Change Management Process

- 19 Mar 2020

Businesses must constantly evolve and adapt to meet a variety of challenges—from changes in technology, to the rise of new competitors, to a shift in laws, regulations, or underlying economic trends. Failure to do so could lead to stagnation or, worse, failure.

Approximately 50 percent of all organizational change initiatives are unsuccessful, highlighting why knowing how to plan for, coordinate, and carry out change is a valuable skill for managers and business leaders alike.

Have you been tasked with managing a significant change initiative for your organization? Would you like to demonstrate that you’re capable of spearheading such an initiative the next time one arises? Here’s an overview of what change management is, the key steps in the process, and actions you can take to develop your managerial skills and become more effective in your role.

Access your free e-book today.

What is Change Management?

Organizational change refers broadly to the actions a business takes to change or adjust a significant component of its organization. This may include company culture, internal processes, underlying technology or infrastructure, corporate hierarchy, or another critical aspect.

Organizational change can be either adaptive or transformational:

- Adaptive changes are small, gradual, iterative changes that an organization undertakes to evolve its products, processes, workflows, and strategies over time. Hiring a new team member to address increased demand or implementing a new work-from-home policy to attract more qualified job applicants are both examples of adaptive changes.

- Transformational changes are larger in scale and scope and often signify a dramatic and, occasionally sudden, departure from the status quo. Launching a new product or business division, or deciding to expand internationally, are examples of transformational change.

Change management is the process of guiding organizational change to fruition, from the earliest stages of conception and preparation, through implementation and, finally, to resolution.

As a leader, it’s essential to understand the change management process to ensure your entire organization can navigate transitions smoothly. Doing so can determine the potential impact of any organizational changes and prepare your teams accordingly. When your team is prepared, you can ensure everyone is on the same page, create a safe environment, and engage the entire team toward a common goal.

Change processes have a set of starting conditions (point A) and a functional endpoint (point B). The process in between is dynamic and unfolds in stages. Here’s a summary of the key steps in the change management process.

Check out our video on the change management process below, and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more explainer content!

5 Steps in the Change Management Process

1. prepare the organization for change.

For an organization to successfully pursue and implement change, it must be prepared both logistically and culturally. Before delving into logistics, cultural preparation must first take place to achieve the best business outcome.

In the preparation phase, the manager is focused on helping employees recognize and understand the need for change. They raise awareness of the various challenges or problems facing the organization that are acting as forces of change and generating dissatisfaction with the status quo. Gaining this initial buy-in from employees who will help implement the change can remove friction and resistance later on.

2. Craft a Vision and Plan for Change

Once the organization is ready to embrace change, managers must develop a thorough, realistic, and strategic plan for bringing it about.

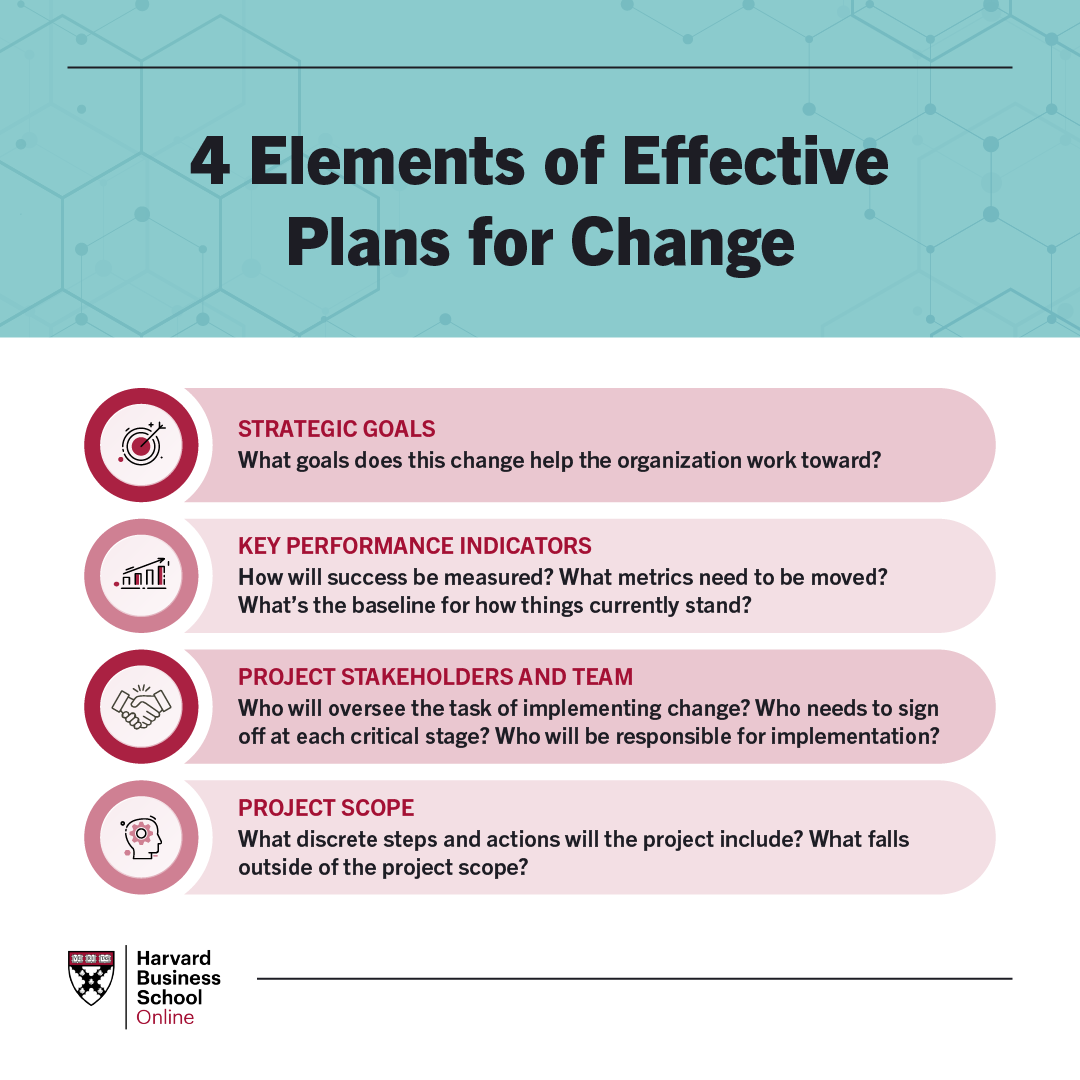

The plan should detail:

- Strategic goals: What goals does this change help the organization work toward?

- Key performance indicators: How will success be measured? What metrics need to be moved? What’s the baseline for how things currently stand?

- Project stakeholders and team: Who will oversee the task of implementing change? Who needs to sign off at each critical stage? Who will be responsible for implementation?

- Project scope: What discrete steps and actions will the project include? What falls outside of the project scope?

While it’s important to have a structured approach, the plan should also account for any unknowns or roadblocks that could arise during the implementation process and would require agility and flexibility to overcome.

3. Implement the Changes

After the plan has been created, all that remains is to follow the steps outlined within it to implement the required change. Whether that involves changes to the company’s structure, strategy, systems, processes, employee behaviors, or other aspects will depend on the specifics of the initiative.

During the implementation process, change managers must be focused on empowering their employees to take the necessary steps to achieve the goals of the initiative and celebrate any short-term wins. They should also do their best to anticipate roadblocks and prevent, remove, or mitigate them once identified. Repeated communication of the organization’s vision is critical throughout the implementation process to remind team members why change is being pursued.

4. Embed Changes Within Company Culture and Practices

Once the change initiative has been completed, change managers must prevent a reversion to the prior state or status quo. This is particularly important for organizational change related to business processes such as workflows, culture, and strategy formulation. Without an adequate plan, employees may backslide into the “old way” of doing things, particularly during the transitory period.

By embedding changes within the company’s culture and practices, it becomes more difficult for backsliding to occur. New organizational structures, controls, and reward systems should all be considered as tools to help change stick.

5. Review Progress and Analyze Results

Just because a change initiative is complete doesn’t mean it was successful. Conducting analysis and review, or a “project post mortem,” can help business leaders understand whether a change initiative was a success, failure, or mixed result. It can also offer valuable insights and lessons that can be leveraged in future change efforts.

Ask yourself questions like: Were project goals met? If yes, can this success be replicated elsewhere? If not, what went wrong?

The Key to Successful Change for Managers

While no two change initiatives are the same, they typically follow a similar process. To effectively manage change, managers and business leaders must thoroughly understand the steps involved.

Some other tips for managing organizational change include asking yourself questions like:

- Do you understand the forces making change necessary? Without this understanding, it can be difficult to effectively address the underlying causes that have necessitated change, hampering your ability to succeed.

- Do you have a plan? Without a detailed plan and defined strategy, it can be difficult to usher a change initiative through to completion.

- How will you communicate? Successful change management requires effective communication with both your team members and key stakeholders. Designing a communication strategy that acknowledges this reality is critical.

- Have you identified potential roadblocks? While it’s impossible to predict everything that might potentially go wrong with a project, taking the time to anticipate potential barriers and devise mitigation strategies before you get started is generally a good idea.

How to Lead Change Management Successfully

If you’ve been asked to lead a change initiative within your organization, or you’d like to position yourself to oversee such projects in the future, it’s critical to begin laying the groundwork for success by developing the skills that can equip you to do the job.

Completing an online management course can be an effective way of developing those skills and lead to several other benefits . When evaluating your options for training, seek a program that aligns with your personal and professional goals; for example, one that emphasizes organizational change.

Do you want to become a more effective leader and manager? Explore Leadership Principles , Management Essentials , and Organizational Leadership —three of our online leadership and management courses —to learn how you can take charge of your professional development and accelerate your career. Not sure which course is the right fit? Download our free flowchart .

This post was updated on August 8, 2023. It was originally published on March 19, 2020.

About the Author

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Change Management: From Theory to Practice

Jeffrey phillips.

1 University Libraries, Florida State University, 116 Honors Way, Tallahassee, FL 32306 USA

James D. Klein

2 Department of Educational Psychology & Learning Systems, College of Education, Florida State University, Stone Building-3205F, Tallahassee, FL 32306-4453 USA

This article presents a set of change management strategies found across several models and frameworks and identifies how frequently change management practitioners implement these strategies in practice. We searched the literature to identify 15 common strategies found in 16 different change management models and frameworks. We also created a questionnaire based on the literature and distributed it to change management practitioners. Findings suggest that strategies related to communication, stakeholder involvement, encouragement, organizational culture, vision, and mission should be used when implementing organizational change.

Organizations must change to survive. There are many approaches to influence change; these differences require change managers to consider various strategies that increase acceptance and reduce barriers. A change manager is responsible for planning, developing, leading, evaluating, assessing, supporting, and sustaining a change implementation. Change management consists of models and strategies to help employees accept new organizational developments.

Change management practitioners and academic researchers view organizational change differently (Hughes, 2007 ; Pollack & Pollack, 2015 ). Saka ( 2003 ) states, “there is a gap between what the rational-linear change management approach prescribes and what change agents do” (p. 483). This disconnect may make it difficult to determine the suitability and appropriateness of using different techniques to promote change (Pollack & Pollack, 2015 ). Hughes ( 2007 ) thinks that practitioners and academics may have trouble communicating because they use different terms. Whereas academics use the terms, models, theories, and concepts, practitioners use tools and techniques. A tool is a stand-alone application, and a technique is an integrated approach (Dale & McQuater, 1998 ). Hughes ( 2007 ) expresses that classifying change management tools and techniques can help academics identify what practitioners do in the field and evaluate the effectiveness of practitioners’ implementations.