Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

CASE STUDY: PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Making brand portfolios work

In theory, at least, most marketers recognize that they should run their brands as a portfolio. Managing brands in a coordinated way helps a company to avoid confusing its consumers, investing in overlapping product-development and marketing efforts, and multiplying its brands at its own rather than its competitors' expense. Moreover, killing off weaker or ill-fitting parts of the product range—an important tenet of brand-portfolio management, though not one that should be applied at all times—frees marketers to focus resources on the stronger remaining brands and to position them distinctively. It thus reduces the complexity of the marketing effort and counteracts the decreasing efficiency and effectiveness of traditional media and distribution channels.

Theory, however, is one thing, practice another. Marketers today face heavy pressure to produce growth in an era of fragmenting customer needs. Understandably, they often react by expanding rather than pruning their brand offerings. After all, killing tired brands and curbing the launch of new ones isn't easy when the remaining portfolio must capture nearly half of a discontinued brand's volume merely to break even. Marketers also worry about the repercussions of using a portfolio approach and making the wrong call. Companies today are more likely to punish brand managers for missing an emerging opportunity than for failing when they try to exploit it.

For these and other reasons, brands (including sub-brands and line extensions) are proliferating at a breakneck pace in industries such as beverages, consumer durables, food, household goods, and pharmaceuticals. 1 1. Roughly three-quarters of the Fortune 1000 consumer goods companies manage more than 100 brands each. From 1997 to 2001, the number of brands increased by 79 percent in the pharmaceutical industry, by 60 percent in white goods and travel and leisure, by 46 percent in the automotive industry, and by at least 15 percent in food, household goods, and beverages. Among other ills, this explosion makes it harder to define customer segments and positioning objectives consistently. Consider, for example, the predicament of automakers that have stuffed their brand portfolios with dozens of all-too-similar sport utility vehicles. Discerning indeed is the consumer who can pick out meaningful differences among them. Costs reflect the profusion of brands as well, since companies with too many of them suffer from increased marketing and operational complexity and from the associated diseconomies of scale.

If marketers are to thrive, they must resist the compulsion to launch new and protect old brands and instead shepherd fewer, stronger ones in a more synchronized way. Anheuser-Busch, for example, uses a coordinated approach: it recognizes that customers shift to different beers (from lower- to higher-end or fuller to lighter brews, for example), and its portfolio strategy aims to keep those customers within its family of brands when they do so. Procter & Gamble has carried out a successful global rationalization over the past few years. And several other consumer goods companies have achieved rates of revenue growth two to five times higher than their historic norms and saved 20 percent of their overall marketing expenditures by managing their brand portfolios more effectively.

How do such companies do so? In part by establishing clear roles, relationships, and boundaries for their brands and then, within these guidelines, giving individual brand managers plenty of scope, subject to oversight from one person who is responsible for the portfolio as a whole. Top-down goals, such as P&G's recent desire to prune brands that aren't top-two performers in their categories, also play an important role—provided that the goals are informed by a deep understanding of consumer needs. In addition, since new portfolio strategies frequently prompt reactions from competitors and have unanticipated consequences, companies will have to change the organization to facilitate quick, coordinated responses for the portfolio as a whole and for individual brands. Robust metrics that highlight unexpected shifts are critical to both.

More brands, lower revenues

The portfolio problem

It's easy to see why marketers resist the portfolio approach to brands. After all, entrepreneurial brand managers, not portfolio managers, built most of the world's great ones, such as Tide (P&G) and Cheerios (General Mills), in the United States, and Persil (Henkel), in Europe. Even if most of these brands are part of portfolios today, a portfolio approach wasn't necessary when the pioneers were developing smaller numbers of brands.

But managing them has become more difficult, since companies in maturing sectors have not only used new brands and products to pursue continued growth but also resisted pruning existing ones, in hopes of maintaining market share, cash flows, and long-lived consumer franchises. Mergers, which became much more common during the 1980s and 1990s, 2 2. Global merger activity increased by 11 percent a year from 1992 to 2000. compounded the problem. All too often, an acquisition motivated by the allure of a specific brand, such as PepsiCo's purchase of Quaker Oats to obtain Gatorade, also brought a legacy—from breakfast cereals like Cap'n Crunch to dinner favorites like Rice-A-Roni—that complicated the portfolio manager's task.

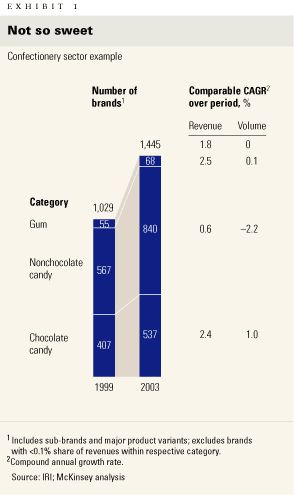

Although the search for growth provided the main impetus for launching new brands and sheltering old ones, most industries failed to achieve the desired result. In confectionery, for example, the number of brands increased by more than 40 percent in recent years, but overall revenue and volume haven't kept pace (Exhibit 1): most individual candy brands have a smaller market share than they did a few years ago. In addition, an ever-growing number of brands imposes complexity costs affecting the entire life cycle, from product development and sourcing (more R&D resources) to manufacturing and distribution (more labor schedules to coordinate) to sales and channel management (more training and more brands than the sales force can really focus on) to marketing and promotions (more documentation and more coordination of marketing vendors and agencies).

The demanding nature of the solution makes matters even more difficult: restoring order calls for centralization and restraint, both of which run against the grain of even the most sophisticated marketing organizations. 3 3. For a summary of the promise and pitfalls of brand consolidation, see Lars Finskud, Egil Hogna, Trond Riiber Knudsen, and Richard Törnblom, ' Brand consolidation makes a lot of economic sense ,' The McKinsey Quarterly , 1997 Number 4, pp. 189–93. Brand moves that look economically attractive or strategically tidy may founder because of the complex interrelationships between products and segments or a backlash from consumers. Volkswagen's impressive success at repositioning Seat and koda Auto, for instance, raised the bar for some of Volkswagen's core products, such as the Golf. Even Proctor & Gamble had to backtrack on its effort to replace Fairy dishwasher detergent with Dawn in Germany after its market share in dish soaps dropped to 5 percent, from 12 percent, in less than two years.

Crafting a portfolio strategy

To deal with the mess, companies need a flexible portfolio approach sensitive to consumers and current brands alike. While bold, top-down declarations of intent do have a place, marketers will be better served by first clarifying the needs that brands could satisfy and then assessing both the economic attractiveness of meeting them and their fit with the positioning of existing brands. Only then should marketers move to increase the portfolio's value by making strategic decisions on the restructuring, acquisition, divestiture, or launch of brands.

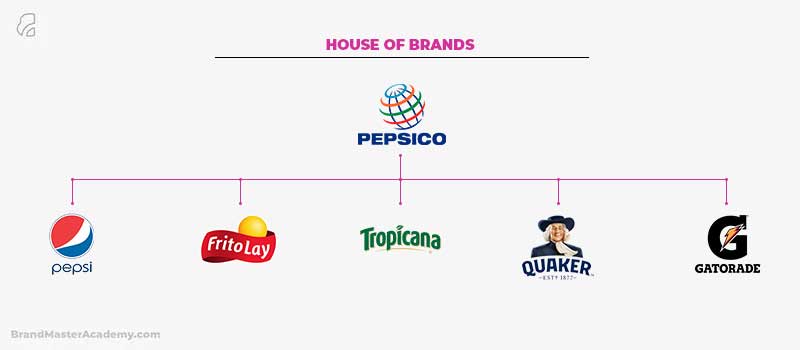

Start with the consumer

The starting point for marketers is to define categories as consumers do. Over the past decade or so, PepsiCo, for example, has recognized that customers choose among all nonalcoholic beverages, not just carbonated ones, to satisfy their need for refreshment. It has therefore made acquisitions (Gatorade, SoBe, Tropicana), developed new products (Amp, Aquafina), and completed several joint ventures (the one with Starbucks led to the bottled Frappuccino). Strong operating results have followed. 4 4. Pepsi's share of the US noncarbonated segment increased from 37.6 percent in 2000 to 45.6 percent in 2003. At the same time, Coca-Cola's share increased to 28.4 percent, from 25.3 percent. These figures exclude Tropicana's 100 percent fruit juice products. Had they been included, Pepsi's lead over Coke would be even higher. Pepsi has the number-one brand in water, juices, iced tea, and sports drinks.

Successes such as PepsiCo's—as well as Kellogg's winning move from breakfasts to nutritional minimeals and Procter & Gamble's repositioning of Olay from moisturizing products to all skin- and beauty-care offerings—result from a judicious, deliberate broadening of a company's frame of reference. The revised view of consumer needs is neither too narrow and category constrained nor too broad and conceptual. Moving gradually often helps companies to strike such a balance; PepsiCo, for instance, initially expanded its frame of reference from cola drinks to all carbonated beverages and only later moved into nonalcoholic, nondairy ones. The fit between the redefined frame of reference and existing organizational capabilities also provides a reality check. When an expanded frame of reference implies brand-extension opportunities that a company can't easily seize by itself, it must weigh the benefits of acquisitions or partnerships to broaden its portfolio against their complexity costs.

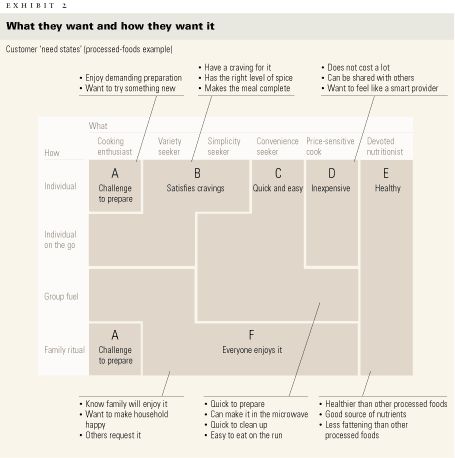

Within a given frame of reference, marketers need a disciplined way of evaluating their brands' opportunities. One is to scrutinize "need states"—the intersection between what customers want and how they want it (Exhibit 2). Many marketers think about need states from time to time, but most define their brands by product (for instance, an economy brand) or consumer segment (young adults, say) instead of consumer needs ("people consume this brand when they want something cheap, don't care about nutrition, and can't spend time cooking at home"). Although thinking through need states is demanding, it often suggests new ways for existing brands to satisfy the needs of customers, thereby helping marketers avoid the common trap of launching a new brand every time they want to enter a market.

Analyzing the customer's 'need states'

When a global brewer scrutinized the need states of its customers, for example, it discovered that there was no single "import" segment; a wide range of people bought imports across several need states. Such findings show that the "one brand per customer segment" approach can be mistaken. If the occasions when consumers use a product largely shape their needs, it is often appropriate to offer the target consumer a number of brands.

Balance economic opportunity with brand reality

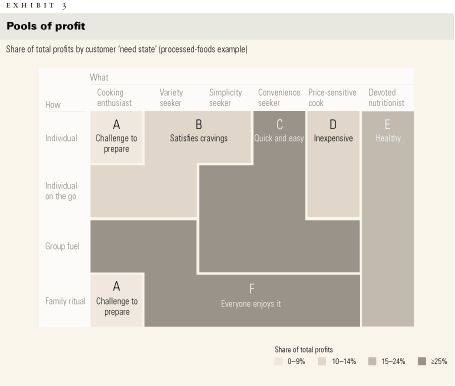

Need states are more than descriptive tools: they also represent market opportunities. To evaluate them, marketers must begin by estimating their size. Since need states rarely coincide with conventional market definitions, it is often necessary to piece together known segment-share and channel-mix figures creatively. Category, consumer, product, and packaging trends can point to the likely future size of need states, and potential shifts in the intensity of competition can shed light on future profitability. The resulting profit pool map (Exhibit 3) reveals attractive opportunities for brands to target.

Mapping future profits through 'need state' analysis

But make no mistake: a profit map is no portfolio strategy. For starters, to target some seemingly attractive need states, it may be necessary to reposition brands so much that they no longer appeal to their original consumers. Such considerations help explain Toyota Motor's 1989 decision to launch Lexus as a separate brand and not as a new Toyota model. By contrast, Mazda Motor's much-praised Millenia luxury car struggled with its brand identity from introduction in 1994 until it was phased out in 2003.

To avoid positioning mistakes, marketers must understand each brand's unique contribution to the portfolio. Mapping its current brands against the universe of relevant need states is a helpful starting point. The most valuable insights often emerge when marketers use statistical tools and market research to assess the relationship between the things customers value in a given need state and the attributes that differentiate the brand for them. 5 5. Such an analysis is also frequently the starting point for efforts to set individual brand strategies. In fact, the mapping of brands against need states represents the intersection of portfolio and single-brand strategies. For more on individual brand strategies and statistical tools, see Nora A. Aufreiter, David Elzinga, and Jonathan W. Gordon, ' Better branding ,' The McKinsey Quarterly , 2003 Number 4, pp. 28–39. Combining this consumer knowledge with conventional metrics (such as each brand's market share within a variety of need states as well as the proportion of each brand's volume that a need state represents) helps clarify the attainable opportunities for each brand and the amount of differentiation or overlap within the portfolio.

Many companies mapping out their portfolios find that they have at least one relatively weak brand. Some choose to retain and improve underperformers rather than jettisoning them or targeting them toward new customers, but that approach carries risks. Frequently, companies that hold on to underperformers can't really support all of their brands and thus have to make small cuts in the resources allotted to each, thereby undermining the performance of their portfolios. One benefit of developing a profit map is that it helps catalyze more dramatic action by painting a clear picture of the economic opportunities companies forgo if they don't take the portfolio approach.

Make the tough choices

Marketers generally have two options for achieving their portfolio goals. First, they can restructure their brands by repositioning those that have lost relevance to the target segments, by consolidating two or more mature brands competing for the same consumers or by divesting a brand that absorbs more resources than it contributes and holds little promise of a turnaround. Restructuring doesn't involve pursuing customers whom a company doesn't currently serve; rather it means changing the brands that serve its present customers. The other option is to change the portfolio to drive new growth by launching a new brand, by acquiring or licensing one from another company, or by redefining an existing brand to target a new category of customers.

Restructuring is scary because it involves modifying brands and consumer attitudes. But though careful management is certainly needed to restructure brands without losing customers, the risk of adding new brands or categories is often greater—and so are the investments. Value-creating brand acquisitions are few and far between. Roughly three-quarters of all new brands fail. And stretching brands into any new category is risky because it's easy to go too far and lose their identity. Brand managers are accustomed to making headlines through launches or acquisitions, but those tactics are usually the last to consider for a portfolio strategy.

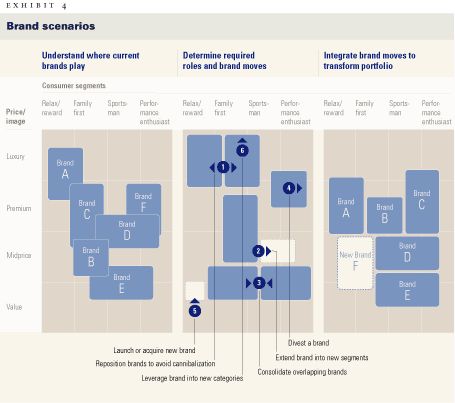

Of course, companies can rework their brand portfolios in a number of ways, which are often interconnected—if one brand is repositioned, that may have ripple effects for others—so it isn't practical to evaluate each brand move in isolation. Marketers must therefore develop and compare a manageable number of plausible scenarios that bundle compatible moves. Each scenario should involve only a few of them (Exhibit 4); more than four or five can overwhelm a marketing organization and confuse consumers. To define those moves, a company must make decisions about issues such as the right number of brands—and which to have—and the advisability of offering umbrella brands with sub-brands beneath them rather than a medley of individual ones.

Adjusting a brand portfolio through carefully defined moves

Several rules of thumb help marketers to avoid playing a trial-and-error game. First, they can build their strategies around leading brands. If well-known ones are financially successful, their role in the portfolio shouldn't change much, but when they underperform it's critical to adjust their positioning before recrafting the roles of other brands. Second, marketers must ensure that their sophisticated and ambitious portfolio ideas are feasible in view of internal resource constraints and likely competitive reactions. Finally, they should know when a brand is the consumer's second choice. Research techniques such as conjoint analysis can help them learn whether two or more adjacent brands are taking share and margins from each other or from competitors.

For an international industrial-equipment manufacturer, building the portfolio around a leading global brand has been a straightforward affair in many markets but problematic where the company's other brands are powerful leaders. In those countries, the company makes styling adjustments and includes features valued locally even though they increase the complexity of its offerings. It also found that in some markets, it sold similar products for different prices. The resulting cannibalization—people usually bought the cheaper offering—was costly. By clarifying brand roles, making local adjustments when necessary, and doubling the number of shared parts in products, the manufacturer has raised its portfolio sales by 3 percent in a stagnant market and cut its development costs by up to 5 percent.

Managing the portfolio

Getting strategy right is only part of the battle; companies must also make organizational changes if they are to adapt their brand portfolios quickly to shifting trends, competitive responses, mergers, and new-product launches while also managing the natural life cycle of their brands. Since taking action with one often means doing so with another, companies must appoint a dynamic portfolio manager who can ensure that the whole portfolio moves nimbly.

How can a company centralize this kind of authority without handcuffing the managers of its individual brands? That depends largely on how it constitutes the portfolio manager's role. The crucial thing is that the person who holds it must have the ability to determine, on an ongoing basis, how well individual brands are fulfilling their part in the portfolio strategy and whether the strategy itself still makes sense. The portfolio manager must, of course, have certain traits and skills. But much will also be required of the organization, including unity of purpose across functions and businesses and robust metrics for tracking performance.

Structural options

To articulate and monitor a brand-portfolio strategy, the portfolio manager must have the authority, the marketing skills, the facts, and the analyses to sway the brand managers. Sometimes the chief marketing officer, the vice president for marketing, or a person who rose through the ranks of the marketing organization and then became general manager of a business unit can serve as portfolio manager while still carrying out his or her primary duties. The support team might consist primarily of "swing" analysts who have some responsibility for individual brands but can be called up by the portfolio manager for major events, such as a new-product launch or the acquisition of several brands. At the extreme, brand teams might have a fluid membership.

In other cases—particularly in industries characterized by rapidly changing tastes (fashion), many sub-brands (autos), or rapid consolidation—a full-time portfolio-management structure may be warranted. One global automobile manufacturer relies on a central organization to coordinate its brand strategy. Pricing is one key area of focus because although each of the portfolio's car lines has a specific role that its list price reflects, differences in base features and functions make apples-to-apples comparisons difficult. The central team gets around this problem by creating "virtual" cars with identical features across brands, setting the value of each brand according to its role in the portfolio, and then building in or stripping out standard features to arrive at real pricing.

Essential tasks

Whatever structure a company selects, it is vital for the portfolio manager to channel the entrepreneurial energies of the brand managers in the right direction and, when necessary, to make them trim their sails or change course.

Building agreement . The portfolio manager must get individual brand groups to endorse the portfolio strategy formally. Incentives that reward them for the whole portfolio's performance help to ensure that they don't revise their brands' strategies when no one is watching.

Meanwhile, the portfolio manager should reconcile the portfolio strategy with functional agendas elsewhere in the company. It might, for example, be necessary to set up focused R&D initiatives to fill gaps in the brand portfolio, to work with the finance organization to include key brand metrics in annual and long-range plans, and to have the sales organization develop a calendar and resource-allocation guidelines. The calendar would be linked to key dates in the strategy's rollout, and the guidelines would include directions for presenting brands to intermediaries such as grocery stores or car dealers.

Tracking progress . Measuring whether each brand is fulfilling its role in the portfolio is crucial. Standard metrics show whether consumers know about, have tried, or ever considered purchasing a brand; their attitudes toward it (for instance, is it "worth paying more for?"); rates for converting prospects into customers and for retaining customers in target segments; and levels of customer satisfaction. Other metrics should be tailored to the strategic goals for each brand. If the managers of several brands in the same portfolio track identical metrics, the company often has a problem: either the metrics are at too high a level to shed light on the relative performance of different brands, or the brands are positioned so closely together that the strategy needs a rethink.

An appliance maker introducing a new, lower-priced line to its portfolio, for example, found it helpful to track product-mix changes by sales channels. It discovered that in some of them, its existing premium products were positioned close to the new line, a problem that leads to cannibalization and falling margins. This timely channel data prompted the company to stop the bleeding quickly. Well-conceived metrics also clarify major competitive moves. In the value end of the appliance industry, for instance, LG Electronics and Samsung have made advances that are prompting several other manufacturers to rethink the role of value offerings in their own portfolios.

Although the annual planning process is a natural time for such dialogues, brand managers should raise red flags whenever these issues appear, particularly if the portfolio manager's likely response to them includes adding a brand. When market researchers recognize a new consumer trend, the portfolio manager must get involved to avoid a familiar outcome: a number of similar products for similar customers and need states.

Marketers are uneasy about rigorous brand-portfolio management, but overcoming this mind-set can pay big dividends. For companies that succeed, setting the portfolio strategy isn't a onetime event; it's a living, breathing part of day-to-day business.

Steve Carlotti and Mary Ellen Coe are principals in McKinsey's Chicago office, and Jesko Perrey is a principal in the Düsseldorf office.

The authors wish to thank Jonathan Gordon, Tamara Jurgenson, and Jürgen Schröder for their contributions to this article.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Better branding

- Member Login

- ACCELANCE® for Alignment and Accountability

- Avantage® Segmentation

- Circle of Traction®

- SmartStart Services

- Media and News – VisionEdge Marketing

- Find An Event To Attend

- Advisory Services

- Awesome Customers

- What’s Your Edge? | Accelerate Growth, Create Customer Value, Improve Performance

- Contribute Your Content to the #SmartBusiness Blog

- Customer Case Studies

- Gain Market Traction With Fast-Track Your Business

- Join Our Community

- Event Planners

- Fuel Growth and Fast-Track Your Business

- Data, Analytics, and Insights

- Customer-Centricity, Strategy, and Planning

- Sales Enablement/Marketing and Sales Alignment

- CMO/Marketing Management and Growth Strategies

- Ready, Set, Grow! 8 C-Suite Conversations

- Marketing Accountability, Performance Management and MPM Benchmark Study Overviews

- Test Your Knowledge and Expertise

- White Papers and Guides

- Accelance® Products and Services

- Proven Growth Advice

- Customer-Centric Growth Plan Assessment

- Performance Management Dashboards and Metrics Assessment

- Performance and Operational Excellence Assessment

- Create a Measurable Customer-Centric Growth Plan

- Employ the Power of Positioning and Messaging

- Four Customer-Centric Tools to Better Align Sales & Marketing and Accelerate Customer Acquisition

- Market and Customer Segmentation

- Marketing Effectiveness and Accountability

- LAURA SPEAKS GROWTH

- Interactive Workshops

- One Growth Idea

Two Approaches to Pruning the Brand Portfolio

Fast-track your business..

About the Book

Interbrand conducts an annual brand value research study of the world’s top 100 brands. They assess brand values on a variety of factors such as strategic brand management, budget allocation, ROI, portfolio management, brand extensions, M&A, balance sheet recognition, licensing, transfer pricing and investor relations. The combined total value of the Top 100 now reflects two trillion dollars!

Are Your Brands Costing More than They’re Worth?

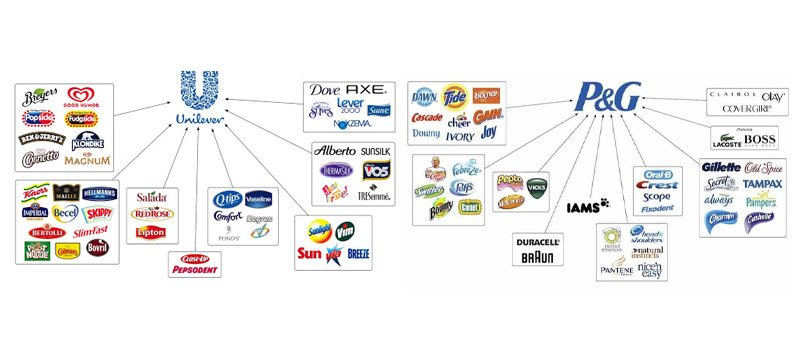

According to some research, most businesses earn almost all of their profits from a small number of brands. In a HBR article, Nirmalya Kumar, a professor a the London School of Business, wrote that many corporations generate 80% to 90% of their profits from fewer than 20% of the brands/products they sell, and lose money or barely break even on many of the other brands in their portfolio. He provided a couple of examples, including one for Unilever which in 1999 had 1600 brand in its portfolio, but more than 90% of its profits came from 400 brands with the remaining 1200 brands losing money.

Why aren’t these brands profitable? There are certain costs associated with each brand. These costs include the cost to:

- differentiate each brand/product within the market

- manufacture, produce, and service low volume brands

- have the brand in the channel

- manage the complexity of the portfolio (price lists, packaging, inventory, etc.).

To offset these costs, some companies attempt to “club” together several brands or switch from selling local brands to global or regional brands, were unable to maintain market share less than 50% of the time. Similarly, when firms merge two brands, the market share of the new brand stayed below the combined market share of the deleted brands.

Are Your Brand Line Extensions Adding Value to Your Portfolio?

You add even more complexity to the brand portfolio conversation when you mix in brand line extensions. More than half of all new products introduced each year are brand line extensions. When a company introduces a new product by using an established product’s brand name (Coca-Cola, Coca-Cola Light, and Coca-Cola Zero, for example), modifies the package, or adds or changes features in order to appeal to a new segment, they are creating a brand line extension . Companies extend a brand in order to reduce the risks associated with new product development.

For this approach to be successful, Brad VanAuken advises that “Any brand extension into a new product category must reinforce one of those primary associations without creating new negative, conflicting or confusing associations for the brand.”

When executed well, the brand extension will actually reinforce what your brand stands for.” When this association is strong, Nigel Hollis suggests that “the fit between the brand and the category does not need to be based on a direct application of the brand’s functional credentials”.

As you can see when properly implemented, brand extension serves as a strategy intended to increase and leverage brand equity . How? By creating a brand or line extension it may enable you to enter new product categories, new markets or market segments.

Selecting Your Metrics for Brand Extensions

What are some metrics for brand line extensions? Here are three marketing metrics to determine whether a brand line extension is adding value to your portfolio:

- Incremental increase in overall number of profitable customers . Has the extension enable you to acquire profitable customers you wouldn’t have otherwise attracted?

- Greater marketing efficiency , that is sales revenue/marketing costs (remember to include all marketing costs associated with the extension, including people)

- Lower promotional costs of product line extensions – Customers have instant recognition of the product / brand name.

The ultimate business measure of success for any line extension is whether the company experienced increased profits at the introduction and growth stages in the product line extensions life cycle.

Brand Portfolio Management: Should You Prune?

How do you know whether you have too many brands or band extensions? If you answer yes to 6 or more of these 10 questions it may be time to make brand/product rationalization a priority:

- Are more than 50% of our brands/products laggards or losers in their categories?

- Are we unable to match our competitors in marketing and advertising for many of our brands/products?

- Are we losing money on our small products/brands?

- Do we have different brands in different countries for essentially the same product?

- Do the target segments, product lines, pricing strategies, or distribution channels overlap to a great extent for any brands in our portfolio?

- Do our customers think our brands compete with each other?

- Are channel partners/resellers only selling/stocking a subset of our portfolio?

- Does an increase in advertising expenditure for one of brands/products decrease the sales of any of other brands/products?

- Do we spend an inordinate amount of time discussing resource allocations decisions across our brands/products?

- Do our brand/product managers see one another at their biggest rivals?

To answer some of these questions may require you to conduct customer or market research . When you answer yes to 6 or more of these questions it may be time to institute a systematic brand deletion process.

Two Pruning Approaches

There are two approaches for deleting brands: the portfolio approach and the segment approach. You may want to use elements of both in your process.

In the portfolio approach, only those brands that conform to certain parameters are kept. To take this approach you will need to set down strict selection criteria. General Electric’s approach that only those brands that are number one or two or both in their segments as measured by market share is an example of strict criteria. Consider creating at least three criteria: one based on current market share, one based on potential for growth, and one based on profitability. Then evaluate each brand against the selected criteria and retain only those that meet them.

In the segment approach, companies identify brands they need to satisfy key needs and wants within specific segments. This approach requires that you have a clear definition of your market segments and the key needs for each. The process is then to identify those brands that best meet each segments needs and to delete those that do not.

Once you identify the brands you want to delete, evaluate each brand and decide whether you are going to sell it, milk it, kill it, or merge it.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Comments are closed.

Recent Posts

- Better Together: Digital Transformation and Advantageous Excellence

- How BODs Can Architect Better Strategic Customer-Centric Designs | What’s Your Edge

- B2B Customer Experience: Balancing the Human Factor with Technology

- How to Fit the AI Tile into the Innovation Mosaic | What’s Your Edge?

- Measure, Test, Measure: A Proven Framework for Better Data-Driven Decisions

“I love your articles and advice – I feel like everything you write is thought-provoking and actionable.” – Marcie, Marketing Director, Technology industry.

Join our community to gain insights into creating growth strategies and execution; and employing growth enablers, including accountability, alignment, analytics, and operational excellence.

Follow VEM on Twitter

Most Popular Pages

- About VisionEdge Marketing

- WHY VISIONEDGE MARKETING

- #SmartBusiness Blog

- Recorded Guest Appearances

- Subscribe to Newsletter

- Register for Membership

Start a Conversation

- Let’s Work Together! | Request a Quote

© 1999 – VisionEdge Marketing • All rights reserved • POB 342546, Austin, TX 78734• 512-681-8800 • Site Map • Privacy Policy

Privacy Overview

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Programs & Tools

What is a Brand Portfolio? (Models, Types And 6 Top Examples)

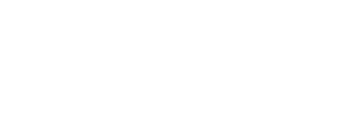

Sometimes, a collection of brands falls under the overarching umbrella of a larger firm or company.

A large parent company uses various brand names to introduce products and services to fulfill the requirements of different market segments.

This relationship between brands is called a brand portfolio, with the parent brand holding a portfolio of sub-brands.

Picture a family tree with the primary brand at the head of the family. In that case, all the branches and offshoots are different brands, often targeting different audiences and market segments.

These brands can be sub-brands or individual brands in their own right.

Each brand is its own entity and can be operated differently from its parent company but is ultimately part of the parent brand’s portfolio strategy.

Depending on the relationship, there are different levels of alignment.

For example, Emporio Armani, Giorgio Armani, and Armani Exchange are all brand extensions within the broader Armani brand portfolio.

In contrast, Always, Head & Shoulders, and Pampers are individual brands in their own right within Procter & Gamble’s brand portfolio.

Let’s unpack the idea of brand portfolios, explore their advantages, and examine some well-known examples.

What Is A Brand Portfolio (Models, Types and 6 Top Examples)

One-click subscribe for video updates

What is a Brand Portfolio?

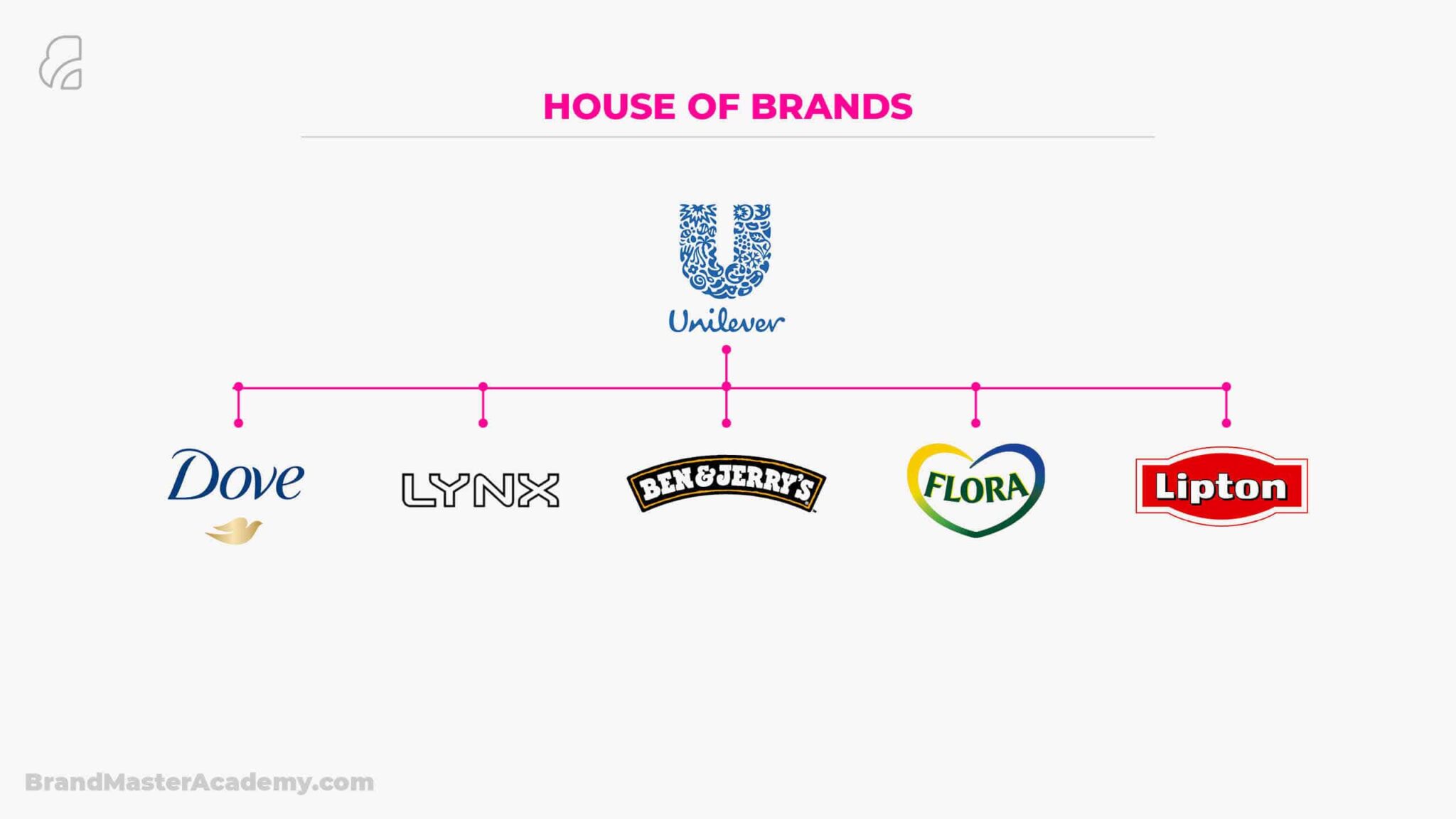

A brand portfolio is a group of brands that are part of a broader “brand umbrella” or “house of brands” created by a business, corporation, or conglomerate.

The Coca-cola company is one of the best-known brand portfolios. Of course, the Coca-cola company’s most famous brand is its flagship beverage, Coke.

However, besides Coke, the Coca-cola company has over 200 brands within its worldwide brand portfolio, including brands offering softdrinks, alcoholic beverages, juices and teas, and dairy products.

Household brand names like Sprite, Fanta, and Costa Coffee are all within the Coca-cola brand family .

Companies typically build, extend, and maintain brand portfolios to establish themselves in different market segments and appeal to a broader range of potential customers.

Brand portfolios exist in virtually every industry.

That’s because there’s always a case for a brand portfolio strategy to allow a company to grow and increase its market share.

To show this, let’s engage in a hypothetical case study.

When To Use A Brand Porfolio

Although some of the best examples of a brand porfolio are giant brands, this approach and strategy is not limited to brands with hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue.

Small brands with multiple products may decide to brand each product to create a clear and transparent offering to its customers, which can provide the structure for growth.

Established brands that want to enter a new market or increase it’s market share may decide to create a new sub-brand, thus creating an umbrella branding structure and the first in its brand portfolio.

More often than not, the decision to use a brand portfolio comes down to diversification, expansion, and increasing market share.

PRO Brand Strategy BluePrint

Build brands like a pro brand strategist.

- The exact step-by-step process 7-Figure agencies use to bag big clients through brand strategy

- How to build brands that command premium fees and stop competing for cheap clients

- How to avoid the expensive amateur mistakes that 95% of brand builders make to fast-track profit growth

Brand Portfolio Case Study

Let’s imagine a company that sells high-end luxury clothing.

This flagship brand has gained a reputation as a status symbol, meaning it can sell products at a high price point to an exclusive clientele.

However, the company’s market research shows that a significant portion of its target market has shifting priorities.

Customer preferences are erring toward more cost-effective clothing options.

This scenario presents a dilemma for the flagship brand.

The flagship brand’s identity is built upon offering luxury items, and the audience expects to pay premium prices for a high-quality, luxurious product.

Offering new products at more affordable prices risks causing damage to the company’s brand by turning off the most loyal customers.

In this scenario, the flagship brand may choose to create an entirely new brand or acquire a brand to satisfy the demand of the growing market segment.

The new brand would concentrate on offering more affordable clothing with a branding strategy to match. This strategy helps the flagship brand avoid engaging in conflicting mixed messaging that could be harmful if it was to bring more affordable products to market.

The new brand would be part of the flagship brand’s brand portfolio.

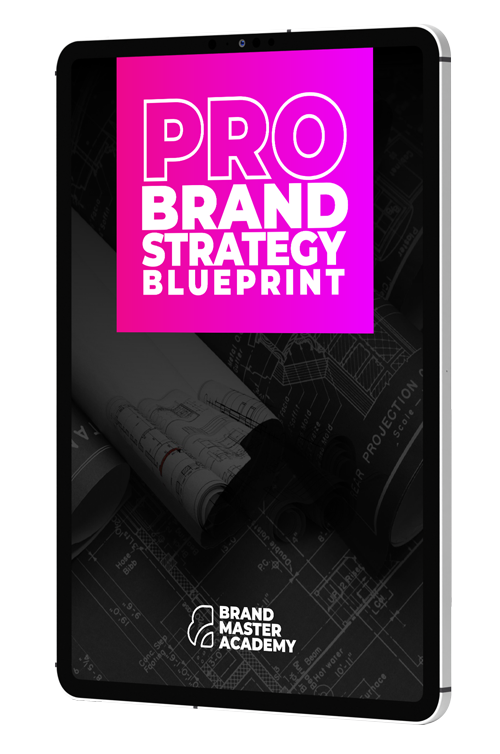

In 1989, Toyota decided to enter the luxury car market, but they knew they would face a challenge with a reputation as an affordable car brand.

Rather than confusing the market, they created the luxury car brand Lexus as a sub-brand within the Toyota brand portfolio.

Within a brand portfolio, brands tend to fall into one of several predetermined roles.

Each brand category has a part to play in the overarching brand portfolio strategy.

Often, businesses will build and sustain brands with different roles to complement one another to maintain a competitive advantage and increase market share within a category.

Explore Brand Strategy Programs & Tools

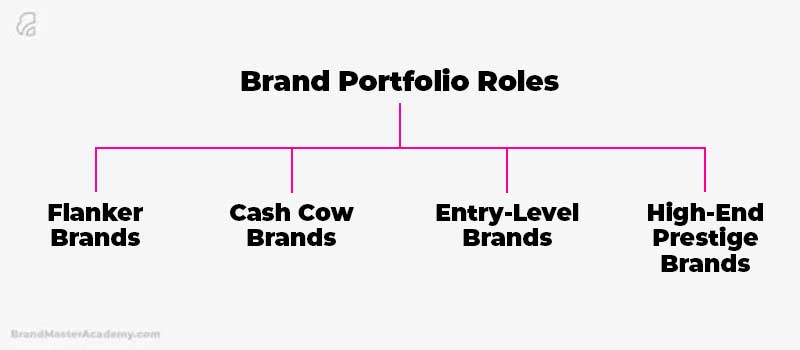

What are brand portfolio roles.

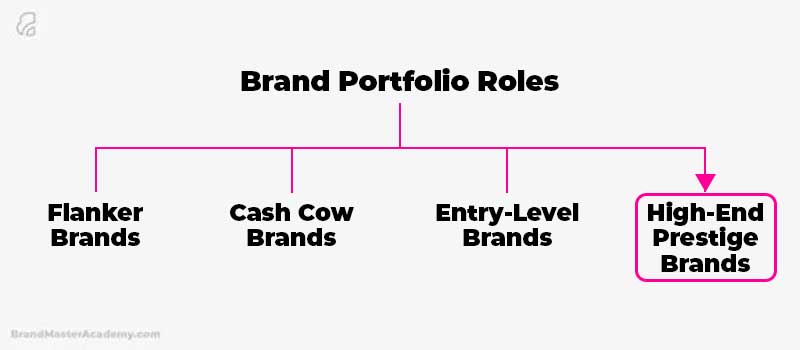

Let’s focus on four main brand portfolio roles: flanker brands, cash cow brands, low-end, entry-level brands, and high-end prestige brands.

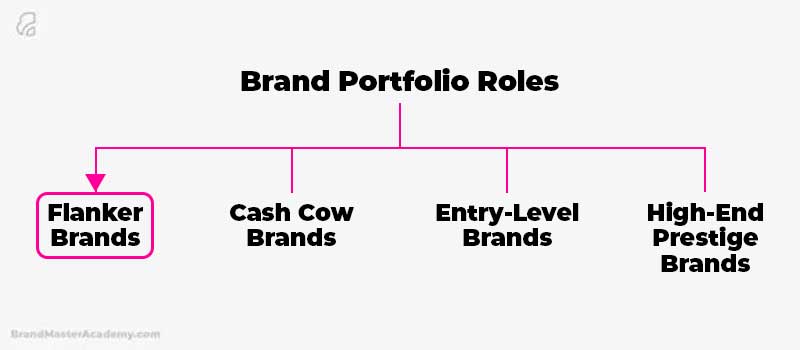

Flanker Brands

A flanker brand is a company’s launching of a brand in a product category where it already has an established brand.

The new brand intends to meet the needs of potential customers that the original brand might not be able to satisfy within that product category.

The aim is to present distinctive brands to appeal to various consumers within different market segments without stepping on the toes of other brands within the portfolio.

For example, Diet Coke, is a flanker brand of Coke, allowing them to extend their reach into the more diet consciencious market.

Although the flagship and flanker brands are officially competitors (i.e. a customer may choose either Coke or Diet Coke), they actually work as a team to complement each other rather than eat into a shared audience.

By targeting different types of consumers within a product category, a parent company aims to strengthen a company’s market position and drive away rivals.

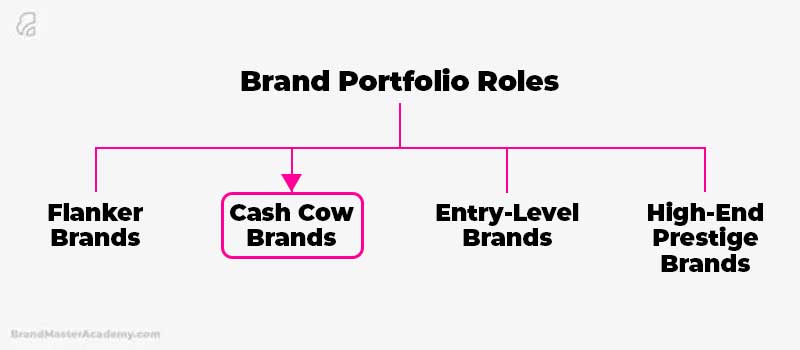

Cash Cow Brands

When a brand reaches a level of maturity and respect, is an established brand within the market, and brings in a sustainable profit, we call the brand a cash cow brand, more often than not the parent brand.

The branded product has matured in its life cycle and is still selling well enough to maintain cash flow.

As opposed to introducing any kind of new product to take their place, it’s better to do nothing and allow these brands to continue to generate revenue. Therefore, they’re rarely taken off the market.

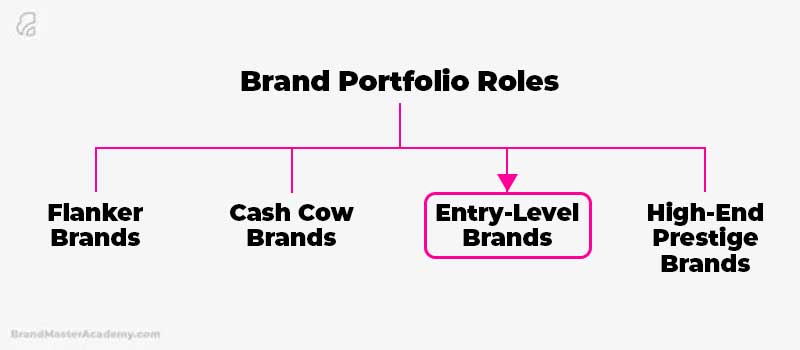

Entry-Level Brands

The low-end, entry-level brands are brands within the brand portfolio that offer low-priced products. These are the brands offering the cheapest products under the parent company’s brand umbrella.

Low prices can hook customers and attract them to the brand family.

The hope is that, once exposed to the lower price points of the entry-level brand, a customer may be tempted to try the other options provided by the parent brand.

An example is when a consumer chooses to stay at the lowest-priced option with Marriott’s brand offerings .

If they appreciate the service and brand experience , the consumer may be more inclined to try one of Marriott’s more luxury brands in the future.

As a customer matures and their income increases over time, they’re more likely to increase their budget for hotel stays.

High-End Prestige Brands

At the other end of the spectrum, high-end prestige brands intend to convey a sense of luxury and superior quality.

As mentioned in the above example, it would be very difficult for a brand such as Toyota, which has a reputation of affordability, to earn a slice of the luxury car market under the same brand.

Creating an independent luxury brand, disassociates from this reputation and allow the brand to establish it’s own reputation for presitige.

Want Actionable Brand Strategy Tips & Techniques?

100% PRIVACY. SPAM FREE

Advantages of Brand Portfolios

Effective brand management relies on understanding the audience. You must make a connection with the audience through brand messaging and experience and carefully manage that relationship.

However, customer preferences shift and, sometimes, a single brand can find that it faces a diminishing market share despite having a loyal customer base.

In this case, the brand strategists may believe that their existing brand can’t expand into new market segments without compromising their relationship with their customer base.

This is where the brand portfolio strategy can help to increase a company’s market share by acquiring existing brands or introducing new brands to a market.

With effective brand portfolio management, the brand portfolio becomes an entity to brand, as all brands under the umbrella follow the same core values and principles of the parent company.

Customers know to expect a high standard when buying Unilver products , for example, or to expect professionalism and innovation when dealing with Microsoft brands.

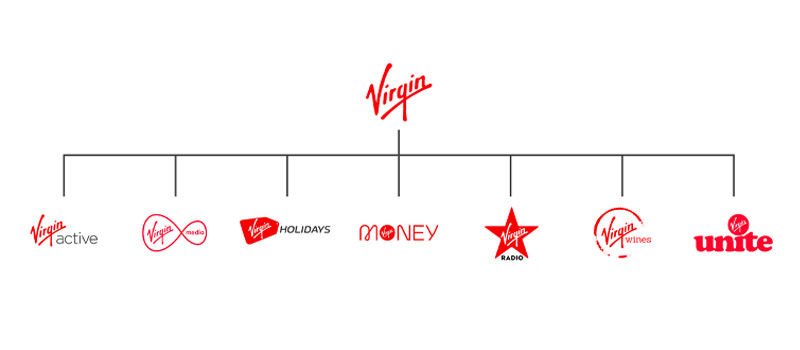

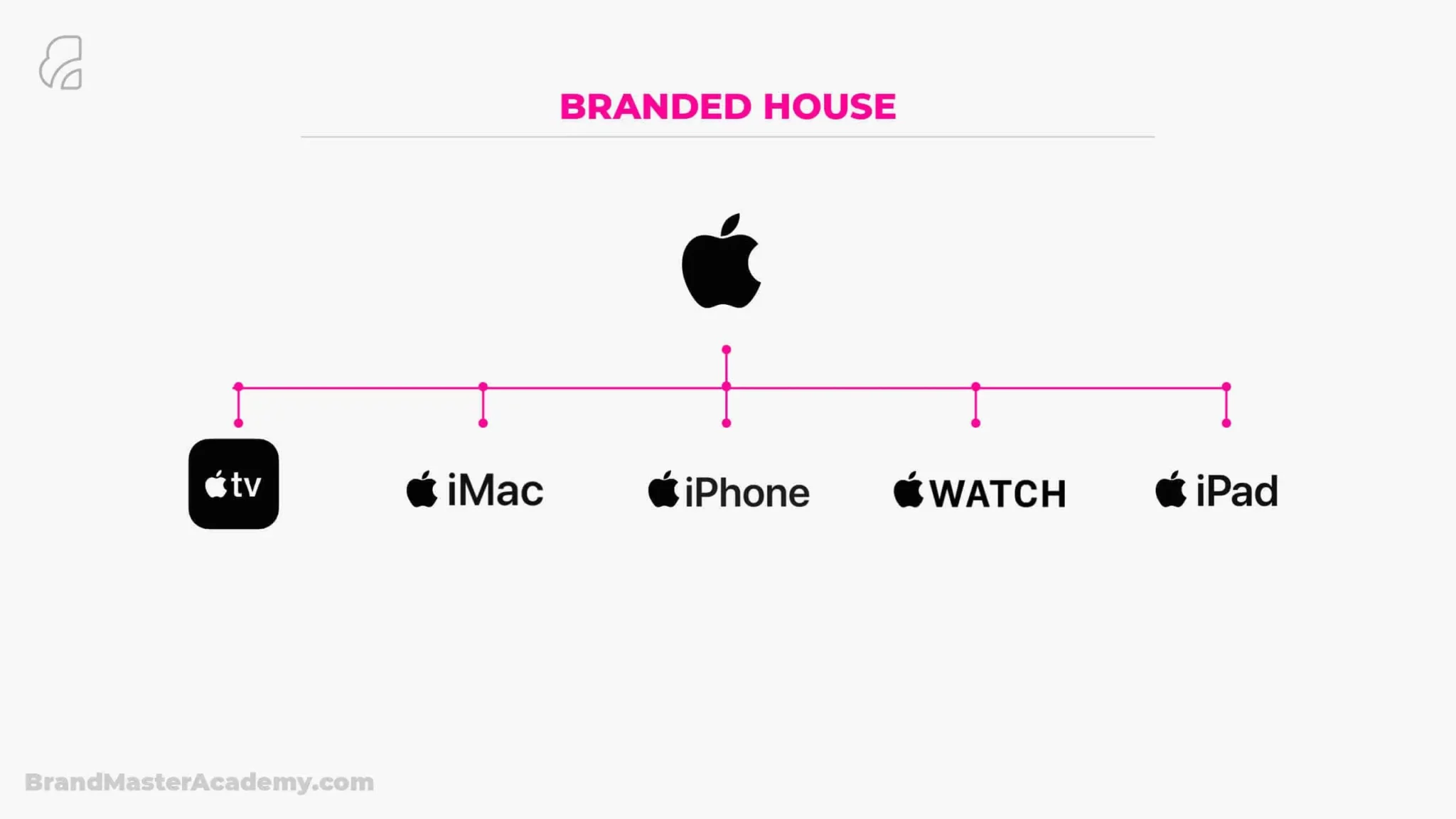

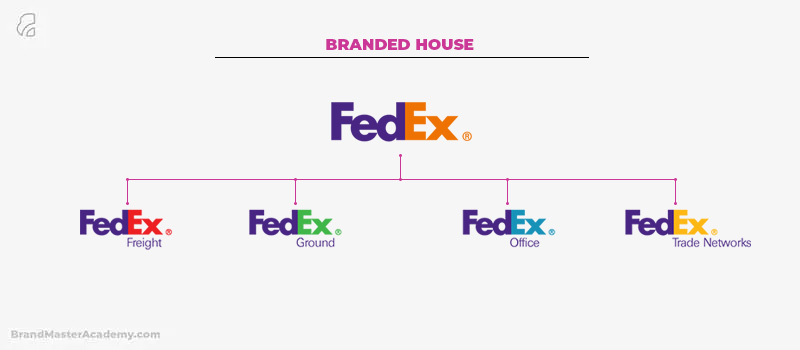

Some brands create clear alignments within portfolios from one brand to the next in “Branded House” structures, such as Virgin or FedEx, where brands are clearly within the same brand family.

On the other hand, “House of Brand” structures, such as Unilever and Proctor and Gamble, create more independence for brands within their portfilios with many customers unaware of the associations.

The brand architecture is a structural representation of the affiliations and partnerships between brands, and where associations are clear, brand equity and reputation and leveraged.

When Nestle or Kellogg’s introduces a new food product, the new product has perceived credibility with the Nestle or Kellogg’s logo on the box.

Virgin, is the parent brand at the head of a “brand family”.

The Virgin brand family leverages the “Branded House” structure, where each subbrand is an endorsed brand (i.e. endorsed by Virgin), with the Virgin logo part of the sub-brand identity.

As each new sub-brand is launched, it enters the market with the competitive advantage of the existing reputation of the parent brand, allowing Virgin to launch sub-brands such as Virgin Media, Virgin Mobile, and Virgin Atlantic to name just a few.

Generally speaking, If a customer trusts the products of one brand of the company and has a positive experience with the product, then there’s a higher chance that they will also trust the products of other brands of the company.

Brand Portfolio Examples

You can find brand portfolios across all industries, and you’ll find a variety of approaches.

Unilever (House Of Brands)

Unilever is the parent company of a vast brand family of over 400 companies worldwide offering products across the home goods, food, and healthcare industries.

They join the brands through a shared vision to ”do good” and make “Sustainable living commonplace.”

Nestle (Hybrid)

Nestle is the world’s largest food and beverage company, offering an eclectic mix of food products with something on almost every aisle of the supermarket.

Unlike other structures, Nestle’s brand architecture is a hybrid of both a Branded House and a House of Brands with endorsed brands with clear alignment and independent brands without.

Pepsico (House Of Brands)

Pepsico is another brand behemoth, often thought of as the main competitor to the Coca-cola company due to the rivalry between the flagship brands.

After bringing Frito-Lay into its folds, its brand portfolio includes some of the giants of the beverage and potato chip industry.

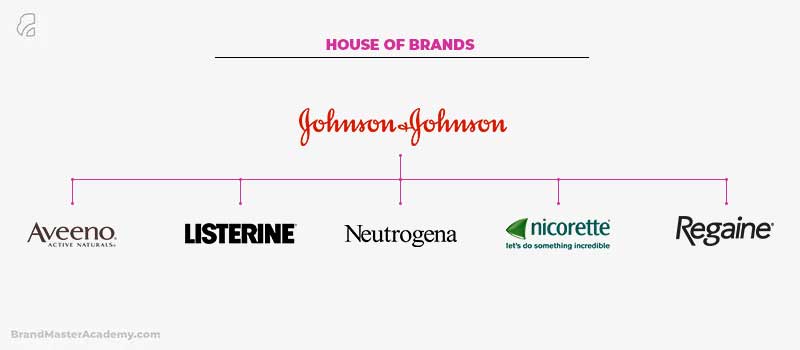

Johnson and Johnson (House Of Brands)

Johnson and Johnson’s brand portfolio spans several industries that fall under the broader healthcare sector.

Interestingly, all of J&J’s baby products, like soap, hair oil, and lotion, fall under a ‘Branded house’ architecture as they feature the Johnson & Johnson branding.

However, they did not decide to extend this branding to other products such as mouthwash, skincare, and pain relief. For example, J&J’s mouthwash products are branded under the Listerine label.

In fact, hundreds of brands operate semi-autonomously and semi-independently within J&J’s brand portfolio.

They are not closely tied or identified as J&J to the target audience but fall under their umbrella structure. This approach gives each brand an element of flexibility in its branding without having to stick to a rigid structure.

For example, J&J branded Nicorette doesn’t align thematically with baby lotion, so it makes sense to create a different brand,

Apple (Branded House)

Apple has created various sub-brands for its products, including the iPhone and Apple TV+.

Each product is known well enough to stand apart as product brands.

However, they all incorporate Apple branding and leverage the brand visual identity and ethos of the master brand.

In this way, Apple can insert new products into different markets with the weight of the overarching Apple brand and its credibility.

FedEx (Branded House)

The FedEx brand portfolio features separate brands for each of its services.

Their brand lineup includes not FedEx Express, FedEx Freight, FedEx Ground and FedEx Kinkos.

The idea is that whatever your shipping need, package or freight, surface or air, U.S. or international, routine or emergency, next day or next week, FedEx has a designated branded service to match it.

Over To You

Correctly organizing the brand portfolio is essential since how a brand portfolio is managed directly affects the organization’s growth and future performance. The ideal portfolio should always align with how the company sees itself developing in the market.

When acquiring or creating new brands to add to a brand portfolio, it must fit into the broader brand strategy to help it achieve its goals.

Brands that do not suit the portfolio should either be changed to better conform with the parent brand’s strategy or be removed from the portfolio altogether.

On-Demand Digital Program

Brand Master Secrets

Make the transition from hired-gun to highly valued brand strategist in less than 30 days. The systems, frameworks and tools inside this comprehensive program are all you need to level up.

Related Posts

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

Get The FREE Framework Template PDF Now!

Create Strategic Brands Like A PRO

Brought to you by:

Prune the Brand Portfolio? (HBR Case Study), Chinese Version

By: Chekitan S. Dev

A global hotel company that has just completed a large merger is debating whether to retain all the brands that came with the acquisition. The company CFO argues that it would be possible for each of…

- Length: 11 page(s)

- Publication Date: Mar 1, 2018

- Discipline: Organizational Behavior

- Product #: R1802X-PDF-CHI

What's included:

- Educator Copy

$4.95 per student

degree granting course

$8.95 per student

non-degree granting course

Get access to this material, plus much more with a free Educator Account:

- Access to world-famous HBS cases

- Up to 60% off materials for your students

- Resources for teaching online

- Tips and reviews from other Educators

Already registered? Sign in

- Student Registration

- Non-Academic Registration

- Included Materials

A global hotel company that has just completed a large merger is debating whether to retain all the brands that came with the acquisition. The company CFO argues that it would be possible for each of them to have its own "swim lane," and that the result would be $200 million in annual cost savings; greater negotiating power with online travel agencies; and the ability to boost both revenue, by cross-selling brands, and occupancy rates, by leveraging a larger reservations system. Others argue that streamlining the brands will enable more resources to go to the most successful ones. With commentary from Noah Brodsky, chief brand officer at Wyndham Vacation Ownership, and the private equity consultant Annick Desmecht.

For teaching purposes, this is the case-only version of the HBR case study. The commentary-only version is reprint R1802Z. The complete case study and commentary is reprint R1802N.

Mar 1, 2018

Discipline:

Organizational Behavior

Industries:

Accommodations

Harvard Business Review Digital Article

R1802X-PDF-CHI

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

- How It Works

- All Projects

- Write my essay

- Buy essay online

- Custom coursework

- Creative writing

- Custom admission essay

- College essay writers

- IB extended essays

- Buy speech online

- Pay for essays

- College papers

- Do my homework

- Write my paper

- Custom dissertation

- Buy research paper

- Buy dissertation

- Write my dissertation

- Essay for cheap

- Essays for sale

- Non-plagiarized essays

- Buy coursework

- Term paper help

- Buy assignment

- Custom thesis

- Custom research paper

- College paper

- Coursework writing

- Edit my essay

- Nurse essays

- Business essays

- Custom term paper

- Buy college essays

- Buy book report

- Cheap custom essay

- Argumentative essay

- Assignment writing

- Custom book report

- Custom case study

- Doctorate essay

- Finance essay

- Scholarship essays

- Essay topics

- Research paper topics

- Top queries link

Best Management Essay Examples

Case study: prune the brand portfolio.

698 words | 3 page(s)

Introduction The success of any company relies heavily on the decisions that managers make on a daily basis. The process of globalization is making it possible for brands to expand into different countries across the globe (Sztorc, 2017). The case study of Otto Hotels and resorts highlight the advantages and challenges that the process can have on a business enterprise. The success of the organization will depend on the decision that the manager makes to prune or retain the existing 21 brands of the organization. Investigating this case study will help in getting a solution that will have a positive impact on the long-term success of Otto Hotels and Resort.

1. What do you think should be done in the case and why? I think the best solution to the problem is to retain the existing 21 brands and map a business strategy that will create a uniform management approach and service delivery. There are various factors that the opposing sides have to take into consideration before making a decision. These factors include profitability, market share expansion, growth, shareholder satisfaction, and economic benefits. The 21 brands present an opportunity for the organization to have its presence in more regions without injecting more funds for expansion (Dev, 2018). They can benefit from getting a higher number of customers which will increase their profit margins.

Use your promo and get a custom paper on "Case Study: Prune the Brand Portfolio?".

Shareholders will also stay loyal to the brands if they can retain the names of flags that they identify with in the franchise. This loyalty and support will have a positive impact on the business process of the organization (Sztorc, 2017). Investors will also not pull funding from the organization after understanding the fact that 21 flags will generate more revenue for them. The 21 brands will ensure that Otto Hotels and resort use pricing models and strategies that will have a positive impact on profits and performance.

Lastly, the 21 brands will have a positive long-term impact on the share value and revenue stream for the organization. The managers should focus on finding ways to ensure that all brands are operating successfully and have a long-term mindset that will increase value for Otto Hotels and Resorts. This approach will ensure that all flags work to achieve uniform results that will have a positive impact on the growth and stability of the organization.

Question 2: Modelling after the Acquisition of Sheraton by Marriott The acquisition of Sheraton by Marriott for 13 billion dollars presents a unique example that Otto Hotels and Resorts can use to model their business structure. The merger makes Marriott the largest hotel company in the world with more than 30 brands (Picker, 2015). Marriott is not looking to make changes to the business operations of Sheraton but take advantage of unique business strategies that the Sheraton uses to get and retain customers.

Otto Hotels and Resorts can learn from this process because Marriott has more flags and they are using a business model that ensures all brands survive the merger to create success in the organization. They can provide unique services that meet the needs of different customers in the society (Picker, 2015). Marriott is not looking to prune any brands but is focusing on improving the performance of individual brands in the community. This approach is helping to ensure that the company remains profitable and competitive in a challenging business environment.

Conclusion The situation above highlights the need to have a strategy that will promote the success of Otto Hotels and resort without affecting the future stability of the organization. There is no need to prune the brands because companies like Marriott are operating a franchise with more than 30 brands successfully. Managers at Otto Hotels should look for a feasible solution that will merge the vision and mission of individual flags to attain long-term growth and profitability in the society. This approach will lead to long-term growth and success for Otto Hotels and resort.

- Dev, C.S. (2018). Case Study: Prune the Brand Portfolio? Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2

- Picker, L. (2015, November 17). Marriott to Buy Starwood Hotels, Creating World’s Largest Hotel Company. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/

- Sztorc, M. (2017). Franchising as a Model of Business and Hotel Development in the Process of Market Globalization. Scientific Journals of the Economic University in Cracow, 825, 60-7

Have a team of vetted experts take you to the top, with professionally written papers in every area of study.

- Harvard Business Review Case Studies

Organizational Development

Prune the Brand Portfolio? (Commentary for HBR Case Study)

Prune the Brand Portfolio? (Commentary for HBR Case Study) ^ R1802Z

Want to buy more than 1 copy? Contact: [email protected]

Product Description

Publication Date: March 01, 2018

A global hotel company that has just completed a large merger is debating whether to retain all the brands that came with the acquisition. The company CFO argues that it would be possible for each of them to have its own "swim lane," and that the result would be $200 million in annual cost savings; greater negotiating power with online travel agencies; and the ability to boost both revenue, by cross-selling brands, and occupancy rates, by leveraging a larger reservations system. Others argue that streamlining the brands will enable more resources to go to the most successful ones. With commentary from Noah Brodsky, chief brand officer at Wyndham Vacation Ownership, and the private equity consultant Annick Desmecht. For teaching purposes, this is the commentary-only version of the HBR case study. The case-only version is reprint R1802X. The complete case study and commentary is reprint R1802N.

This Product Also Appears In

Buy together, related products.

Prune the Brand Portfolio? (HBR Case Study and Commentary)

Prune the Brand Portfolio? (HBR Case Study)

When Your Brand Is Racist (Commentary for HBR Case Study)

Copyright permissions.

If you'd like to share this PDF, you can purchase copyright permissions by increasing the quantity.

Order for your team and save!

Don't have an account? Sign up now

Already have an account login, get 10% off on your next order.

Subscribe now to get your discount coupon *Only correct email will be accepted

(Approximately ~ 0.0 Page)

Total Price

Thank you for your email subscription. Check your email to get Coupon Code.

PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY Case Analysis and Case Solution

Posted by Peter Williams on Aug-09-2018

Introduction of PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY Case Solution

The PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY case study is a Harvard Business Review case study, which presents a simulated practical experience to the reader allowing them to learn about real life problems in the business world. The PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY case consisted of a central issue to the organization, which had to be identified, analysed and creative solutions had to be drawn to tackle the issue. This paper presents the solved PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY case analysis and case solution. The method through which the analysis is done is mentioned, followed by the relevant tools used in finding the solution.

The case solution first identifies the central issue to the PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY case study, and the relevant stakeholders affected by this issue. This is known as the problem identification stage. After this, the relevant tools and models are used, which help in the case study analysis and case study solution. The tools used in identifying the solution consist of the SWOT Analysis, Porter Five Forces Analysis, PESTEL Analysis, VRIO analysis, Value Chain Analysis, BCG Matrix analysis, Ansoff Matrix analysis, and the Marketing Mix analysis. The solution consists of recommended strategies to overcome this central issue. It is a good idea to also propose alternative case study solutions, because if the main solution is not found feasible, then the alternative solutions could be implemented. Lastly, a good case study solution also includes an implementation plan for the recommendation strategies. This shows how through a step-by-step procedure as to how the central issue can be resolved.

Problem Identification of PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY Case Solution

Harvard Business Review cases involve a central problem that is being faced by the organization and these problems affect a number of stakeholders. In the problem identification stage, the problem faced by PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY is identified through reading of the case. This could be mentioned at the start of the reading, the middle or the end. At times in a case analysis, the problem may be clearly evident in the reading of the HBR case. At other times, finding the issue is the job of the person analysing the case. It is also important to understand what stakeholders are affected by the problem and how. The goals of the stakeholders and are the organization are also identified to ensure that the case study analysis are consistent with these.

Analysis of the PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY HBR Case Study

The objective of the case should be focused on. This is doing the PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY Case Solution. This analysis can be proceeded in a step-by-step procedure to ensure that effective solutions are found.

- In the first step, a growth path of the company can be formulated that lays down its vision, mission and strategic aims. These can usually be developed using the company history is provided in the case. Company history is helpful in a Business Case study as it helps one understand what the scope of the solutions will be for the case study.

- The next step is of understanding the company; its people, their priorities and the overall culture. This can be done by using company history. It can also be done by looking at anecdotal instances of managers or employees that are usually included in an HBR case study description to give the reader a real feel of the situation.

- Lastly, a timeline of the issues and events in the case needs to be made. Arranging events in a timeline allows one to predict the next few events that are likely to take place. It also helps one in developing the case study solutions. The timeline also helps in understanding the continuous challenges that are being faced by the organisation.

SWOT analysis of PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY

An important tool that helps in addressing the central issue of the case and coming up with PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY HBR case solution is the SWOT analysis.

- The SWOT analysis is a strategic management tool that lists down in the form of a matrix, an organisation's internal strengths and weaknesses, and external opportunities and threats. It helps in the strategic analysis of PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY.

- Once this listing has been done, a clearer picture can be developed in regards to how strategies will be formed to address the main problem. For example, strengths will be used as an advantage in solving the issue.

Therefore, the SWOT analysis is a helpful tool in coming up with the PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY Case Study answers. One does not need to remain restricted to using the traditional SWOT analysis, but the advanced TOWS matrix or weighted average SWOT analysis can also be used.

Porter Five Forces Analysis for PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY

Another helpful tool in finding the case solutions is of Porter's Five Forces analysis. This is also a strategic tool that is used to analyse the competitive environment of the industry in which PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY operates in. Analysis of the industry is important as businesses do not work in isolation in real life, but are affected by the business environment of the industry that they operate in. Harvard Business case studies represent real-life situations, and therefore, an analysis of the industry's competitive environment needs to be carried out to come up with more holistic case study solutions. In Porter's Five Forces analysis, the industry is analysed along 5 dimensions.

- These are the threats that the industry faces due to new entrants.

- It includes the threat of substitute products.

- It includes the bargaining power of buyers in the industry.

- It includes the bargaining power of suppliers in an industry.

- Lastly, the overall rivalry or competition within the industry is analysed.

This tool helps one understand the relative powers of the major players in the industry and its overall competitive dynamics. Actionable and practical solutions can then be developed by keeping these factors into perspective.

PESTEL Analysis of PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY

Another helpful tool that should be used in finding the case study solutions is the PESTEL analysis. This also looks at the external business environment of the organisation helps in finding case study Analysis to real-life business issues as in HBR cases.

- The PESTEL analysis particularly looks at the macro environmental factors that affect the industry. These are the political, environmental, social, technological, environmental and legal (regulatory) factors affecting the industry.

- Factors within each of these 6 should be listed down, and analysis should be made as to how these affect the organisation under question.

- These factors are also responsible for the future growth and challenges within the industry. Hence, they should be taken into consideration when coming up with the PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY case solution.

VRIO Analysis of PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY

This is an analysis carried out to know about the internal strengths and capabilities of PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY. Under the VRIO analysis, the following steps are carried out:

- The internal resources of PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY are listed down.

- Each of these resources are assessed in terms of the value it brings to the organization.

- Each resource is assessed in terms of how rare it is. A rare resource is one that is not commonly used by competitors.

- Each resource is assessed whether it could be imitated by competition easily or not.

- Lastly, each resource is assessed in terms of whether the organization can use it to an advantage or not.

The analysis done on the 4 dimensions; Value, Rareness, Imitability, and Organization. If a resource is high on all of these 4, then it brings long-term competitive advantage. If a resource is high on Value, Rareness, and Imitability, then it brings an unused competitive advantage. If a resource is high on Value and Rareness, then it only brings temporary competitive advantage. If a resource is only valuable, then it’s a competitive parity. If it’s none, then it can be regarded as a competitive disadvantage.

Value Chain Analysis of PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY

The Value chain analysis of PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY helps in identifying the activities of an organization, and how these add value in terms of cost reduction and differentiation. This tool is used in the case study analysis as follows:

- The firm’s primary and support activities are listed down.

- Identifying the importance of these activities in the cost of the product and the differentiation they produce.

- Lastly, differentiation or cost reduction strategies are to be used for each of these activities to increase the overall value provided by these activities.

Recognizing value creating activities and enhancing the value that they create allow PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY to increase its competitive advantage.

BCG Matrix of PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY

The BCG Matrix is an important tool in deciding whether an organization should invest or divest in its strategic business units. The matrix involves placing the strategic business units of a business in one of four categories; question marks, stars, dogs and cash cows. The placement in these categories depends on the relative market share of the organization and the market growth of these strategic business units. The steps to be followed in this analysis is as follows:

- Identify the relative market share of each strategic business unit.

- Identify the market growth of each strategic business unit.

- Place these strategic business units in one of four categories. Question Marks are those strategic business units with high market share and low market growth rate. Stars are those strategic business units with high market share and high market growth rate. Cash Cows are those strategic business units with high market share and low market growth rate. Dogs are those strategic business units with low market share and low growth rate.

- Relevant strategies should be implemented for each strategic business unit depending on its position in the matrix.

The strategies identified from the PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY BCG matrix and included in the case pdf. These are either to further develop the product, penetrate the market, develop the market, diversification, investing or divesting.

Ansoff Matrix of PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY

Ansoff Matrix is an important strategic tool to come up with future strategies for PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY in the case solution. It helps decide whether an organization should pursue future expansion in new markets and products or should it focus on existing markets and products.

- The organization can penetrate into existing markets with its existing products. This is known as market penetration strategy.

- The organization can develop new products for the existing market. This is known as product development strategy.

- The organization can enter new markets with its existing products. This is known as market development strategy.

- The organization can enter into new markets with new products. This is known as a diversification strategy.

The choice of strategy depends on the analysis of the previous tools used and the level of risk the organization is willing to take.

Marketing Mix of PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY

PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY needs to bring out certain responses from the market that it targets. To do so, it will need to use the marketing mix, which serves as a tool in helping bring out responses from the market. The 4 elements of the marketing mix are Product, Price, Place and Promotions. The following steps are required to carry out a marketing mix analysis and include this in the case study analysis.

- Analyse the company’s products and devise strategies to improve the product offering of the company.

- Analyse the company’s price points and devise strategies that could be based on competition, value or cost.

- Analyse the company’s promotion mix. This includes the advertisement, public relations, personal selling, sales promotion, and direct marketing. Strategies will be devised which makes use of a few or all of these elements.

- Analyse the company’s distribution and reach. Strategies can be devised to improve the availability of the company’s products.

PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY Blue Ocean Strategy

The strategies devised and included in the PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY case memo should have a blue ocean strategy. A blue ocean strategy is a strategy that involves firms seeking uncontested market spaces, which makes the competition of the company irrelevant. It involves coming up with new and unique products or ideas through innovation. This gives the organization a competitive advantage over other firms, unlike a red ocean strategy.

Competitors analysis of PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY

The PESTEL analysis discussed previously looked at the macro environmental factors affecting business, but not the microenvironmental factors. One of the microenvironmental factors are competitors, which are addressed by a competitor analysis. The Competitors analysis of PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY looks at the direct and indirect competitors within the industry that it operates in.

- This involves a detailed analysis of their actions and how these would affect the future strategies of PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY.

- It involves looking at the current market share of the company and its competitors.

- It should compare the marketing mix elements of competitors, their supply chain, human resources, financial strength etc.

- It also should look at the potential opportunities and threats that these competitors pose on the company.

Organisation of the Analysis into PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY Case Study Solution

Once various tools have been used to analyse the case, the findings of this analysis need to be incorporated into practical and actionable solutions. These solutions will also be the PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY case answers. These are usually in the form of strategies that the organisation can adopt. The following step-by-step procedure can be used to organise the Harvard Business case solution and recommendations:

- The first step of the solution is to come up with a corporate level strategy for the organisation. This part consists of solutions that address issues faced by the organisation on a strategic level. This could include suggestions, changes or recommendations to the company's vision, mission and its strategic objectives. It can include recommendations on how the organisation can work towards achieving these strategic objectives. Furthermore, it needs to be explained how the stated recommendations will help in solving the main issue mentioned in the case and where the company will stand in the future as a result of these.

- The second step of the solution is to come up with a business level strategy. The HBR case studies may present issues faced by a part of the organisation. For example, the issues may be stated for marketing and the role of a marketing manager needs to be assumed. So, recommendations and suggestions need to address the strategy of the marketing department in this case. Therefore, the strategic objectives of this business unit (Marketing) will be laid down in the solutions and recommendations will be made as to how to achieve these objectives. Similar would be the case for any other business unit or department such as human resources, finance, IT etc. The important thing to note here is that the business level strategy needs to be aligned with the overall corporate strategy of the organisation. For example, if one suggests the organisation to focus on differentiation for competitive advantage as a corporate level strategy, then it can't be recommended for the PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY Case Study Solution that the business unit should focus on costs.

- The third step is not compulsory but depends from case to case. In some HBR case studies, one may be required to analyse an issue at a department. This issue may be analysed for a manager or employee as well. In these cases, recommendations need to be made for these people. The solution may state that objectives that these people need to achieve and how these objectives would be achieved.

The case study analysis and solution, and PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY case answers should be written down in the PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY case memo, clearly identifying which part shows what. The PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY case should be in a professional format, presenting points clearly that are well understood by the reader.

Alternate solution to the PRUNE THE BRAND PORTFOLIO HBR CASE STUDY AND COMMENTARY HBR case study