- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

BusinessCycles →

No results found in working knowledge.

- Were any results found in one of the other content buckets on the left?

- Try removing some search filters.

- Use different search filters.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

6 Case Study Two—Modelling Business Cycles

- Published: July 2013

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter examines the evolution of econometric research in business cycle analysis mainly during the 1960-90 period. It shows how the research was dominated by an assimilation of the tradition of NBER business cycle analysis by the CC approach, catalysed by time-series statistical methods. It also shows how the research has branched into various directions, such as the DSGE based model simulations for theory verification, device of various cyclical measures, among which forecasting has remained the least successful. Methodological consequences of the assimilation are critically evaluated in light of the meagre achievement of the research in predicting the current global recession.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

A Survey on Business Cycles: History, Theory and Empirical Findings

- Conference paper

- First Online: 14 April 2023

- Cite this conference paper

- Giuseppe Orlando ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2630-5403 5 , 6 &

- Mario Sportelli ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1999-7632 6

Part of the book series: Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics ((SPBE))

Included in the following conference series:

- X Euro-Asian Symposium on Economic Theory "Viability of Economic Theories: through Order and Chaos"

177 Accesses

1 Citations

This work summarizes recent advances in modelling and econometrics for alternative directions in macroeconomics and cycle theories. Starting from the definition of a cycle and continuing with a historical overview, some basic nonlinear models of the business cycle are introduced. Furthermore, some dynamic stochastic models of general equilibrium (DSGE) and autoregressive models are considered. Advances are then provided in recent applications to economics such as recurrence quantification analysis and numerical tools borrowed from other scientific fields such as physics and engineering. The aim is to embolden interdisciplinary research in the direction of the study of business cycles and related control techniques to broaden the tools available to policymakers.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Adachi, M. (1993). Embeddings and immersions . American Mathematical Society.

Google Scholar

Anisiu, M.-C. (2014). Lotka, Volterra and their model. Didáctica Mathematica, 32 , 9–17.

Araujo, R. A., & Moreira, H. N. (2021). Testing a Goodwin’s model with capacity utilization to the US economy. In G. Orlando, A. Pisarchik, & R. Stoop (Eds.), Nonlinearities in economics (pp. 295–313). Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Bastos, J., & Caiado, J. (2011). Recurrence quantification analysis of global stock. Physica A-Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications , 390 .

Brock, W. A., & Dechert, W. D. (1991). Non-linear dynamical systems: Instability and chaos in economics. In W. Hildenbrand & H. Sonnenschein (Eds.), Handbook of mathematical economics (vol. 4, pp. 2209–2235).

Buizza, R. (2018). Ensemble forecasting and the need for calibration. Statistical postprocessing of ensemble forecasts (pp. 15–48). Elsevier.

Chen, P., & Semmler, W. (2021). Financial stress, regime switching and macrodynamics. In G. Orlando, A. N. Pisarchik, & R. Stoop (Eds.), Nonlinearities in economics: An interdisciplinary approach to economic dynamics, growth and cycles (pp. 315–335). Springer International Publishing.

Chiarella, C., Flaschel, P., Groh, G., & Semmler, W. (2013). Disequilibrium, growth and labor market dynamics: Macro perspectives . Springer Science & Business Media.

Chiarella, C., & Flaschel, P. (1996). Real and monetary cycles in models of Keynes-Wicksell type. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 30 (3), 327–351.

Article Google Scholar

Claessens, S., Kose, M. A., & Terrones, M. E. (2021). Financial cycles: What? How? When? NBER International Seminar on Macroeconomics .

Crowley, P. M. (2008). Analyzing convergence and synchronicity of business and growth cycles in the euro area using cross recurrence plots. The European Physical Journal Special Topics, 164 (1), 67–84.

Day, R. H. (1994). Complex economic dynamics: An introduction to macroeconomic dynamics (vol. 2). MIT Press.

Eckmann, J.-P., Kamphorst, S. O., & Ruelle, D. (1987). Recurrence plots of dynamical systems. EPL (Europhysics Letters) , 4 (9), 973.

Fabretti, A., & Ausloos, M. (2005). Recurrence plot and recurrence quantification analysis techniques for detecting a critical regime. examples from financial market indices. International Journal of Modern Physics C , 16 (05), 671–706.

Fanti, L. (2003). Labour contract length, stabilisation and the growth cycle. Rivista internazionale di scienze sociali , pp. 1000–1024.

Giacomini, R. (2013). The relationship between DSGE and VAR models. VAR models in macroeconomics–new developments and applications: Essays in honor of Christopher A. Sims .

Ginoux, J.-M., & Letellier, C. (2012). Van der Pol and the history of relaxation oscillations: Toward the emergence of a concept. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science , 22 (2), 023120.

Gonze, D., & Ruoff, P. (2021). The Goodwin oscillator and its legacy. Acta Biotheoretica, 69 (4), 857–874.

Goodwin, R. M. (1982). A growth cycle. essays in economic dynamics (pp. 165–170). Palgrave Macmillan.

Goodwin, R. M. (1951). The nonlinear accelerator and the persistence of business cycles. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society , 1–17.

Gorban, A. N., Smirnova, E. V., & Tyukina, T. A. (2010). Correlations, risk and crisis: From physiology to finance. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 389 (16), 3193–3217.

Haddad, E. A., Cotarelli, N., Simonato, T. C., Vale, V. A., & Visentin, J. C. (2020). The grand tour: Keynes and Goodwin go to Greece. Economic Structures, 9 (1), 1–21.

Harding, D., & Pagan, A. (2002). Dissecting the cycle: A methodological investigation. Journal of Monetary Economics, 49 (2), 365–381.

Hicks, J. R. (1946). Value and capital: An inquiry into some fundamental principles of economic theory . Clarendon Press.

Jevons, W. S. (1879). The theory of political economy . Macmillan and Company.

Jouan, G., Cuzol, A., Monbet, V., & Monnier, G. (2022). Gaussian mixture models for clustering and calibration of ensemble weather forecasts. Discrete and Continuous Dynamical Systems - S . https://doi.org/10.3934/dcdss.2022037

Kalecki, M. (1971). Selected essays on the dynamics of the capitalist economy 1933–1970 . Cambridge University Press.

Keynes, J. M. (1936). 1973, the general theory of employment, interest, and money (vol. 7). Macmillan for the Royal Economic Society.

Kousik, G., Basabi, B., & Chowdhury, A. R. (2010). Using recurrence plot analysis to distinguish between endogenous and exogenous stock market crashes. Physica a: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 389 (9), 1874–1882.

Kuznets, S. (1930). Static and dynamic economics. The American Economic Review, 20 (3), 426–441.

Lampart, M., Lampartová, A., & Orlando, G. (2022). On extensive dynamics of a Cournot heterogeneous model with optimal response. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science , 32 (2), 023124.

Le Corbeiller, P. (1933). Les systèmes autoentretenus et les oscillations de relaxation. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society , 1 , 328–332.

Letellier, C., & Rossler, O. E. (2006). Rossler attractor. Scholarpedia, 1 (10), 1721.

Li, T., & Yorke, J. A. (1975). Period three implies chaos. American Mathematical Monthly , 82 , 985–992.

Liénard, A. (1928). Etude des oscillations entretenues. Revue Générale De L’électricité, 26 , 901–912.

Lorenz, E. N. (1963). Deterministic nonperiodic flow. Journal of Atmospheric Sciences, 20 , 130–141.

Lorenz, H.-W. (1992). Complex dynamics in low-dimensional continuous-time business cycle models: The Šil nikov case. System Dynamics Review, 8 (3), 233–250.

Lorenz, H. W. (1993). Nonlinear dynamical economics and chaotic motion . Springer Verlag.

Lowe, A. (2017). On economic knowledge: Toward a science of political economics . Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Mackey, M. C., & Glass, L. (1977). Oscillation and chaos in physiological control systems. Science, 197 (4300), 287–289.

Marx, K., & McLellan, D. (2008). Capital: An abridged edition . Oxford University Press.

May, R. M. (1976). Simple mathematical models with very complicated dynamics. Nature, 261 (5560), 459–467.

May, R. M. (2004). Simple mathematical models with very complicated dynamics . In: B. R. Hunt, T. Y. Li, J. A. Kennedy & H. E. Nusse (Eds.), The theory of chaotic attractors . Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-21830-4_7

Metzler, L. A. (1941). The nature and stability of inventory cycles on JSTOR. Review of Economics and Statistics, 23 (3), 113–129.

Mill, J. S. (1848). Principles of political economy with some of their applications to social philosoph y. John W. Parker.

Mittnik, S., & Semmler, W. (2012). Regime dependence of the fiscal multiplier. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 83 (3), 502–522.

OECD. (2016). Quarterly GDP (indicator). https://doi.org/10.1787/b86d1fc8-en

Orlando, G. (2016). A discrete mathematical model for chaotic dynamics in economics: Kaldor’s model on business cycle. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation, 125 , 83–98.

Orlando, G. (2022). Simulating heterogeneous corporate dynamics via the Rulkov map. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 61 , 32–42.

Orlando, G., & Bufalo, M. (2022). Modelling bursts and chaos regularization in credit risk with a deterministic nonlinear model. Finance Research Letters, 47 , 102599.

Orlando, G., & Della Rossa, F. (2019). An empirical test on Harrod’s open economy dynamics. Mathematics, 7 (6), 524.

Orlando, G., & Sportelli, M. (2021). Growth and cycles as a struggle: Lotka-Volterra, Goodwin and Phillips. In G. Orlando, A. Pisarchik, & R. Stoop (Eds.), Nonlinearities in economics (pp. 191–208). Springer.

Orlando, G., & Taglialatela, G. (2021a). An example of nonlinear dynamical system: The logistic map. In G. Orlando, A. Pisarchik, & R. Stoop (Eds.), Nonlinearities in economics (pp. 39–50). Springer.

Orlando, G., & Taglialatela, G. (2021b). Dynamical systems. In G. Orlando, A. N. Pisarchik, & R. Stoop (Eds.), Nonlinearities in economics: An interdisciplinary approach to economic dynamics, growth and cycles (pp. 13–37). Springer International Publishing.

Orlando, G., & Zimatore, G. (2017). RQA correlations on real business cycles time series. Proceedings of the Conference on Perspectives in Nonlinear Dynamics, 2016 (1), 35–41.

Orlando, G., & Zimatore, G. (2018). Recurrence quantification analysis of business cycles. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 110 , 82–94.

Orlando, G., & Zimatore, G. (2020b). Recurrence quantification analysis on a Kaldorian business cycle model. Nonlinear Dynamics, 100 (1), 785–801.

Orlando, G., & Zimatore, G. (2021). Recurrence quantification analysis of business cycles. In G. Orlando, A. Pisarchik, & R. Stoop (Eds.), Nonlinearities in economics (pp. 269–282). Springer.

Orlando, G., Pisarchik, A. N., & Stoop, R. (Eds.). (2021a). Nonlinearities in economics: An interdisciplinary approach to economic dynamics, growth and cycles . Springer International Publishing.

Orlando, G., Stoop, R., & Taglialatela, G. (2021b). Bifurcations. In G. Orlando, A. Pisarchik, & R. Stoop (Eds.), Nonlinearities in economics (pp. 51–72). Springer.

Orlando, G., Stoop, R., & Taglialatela, G. (2021c). Chaos. In G. Orlando, A. Pisarchik, & R. Stoop (Eds.), Nonlinearities in economics (pp. 87–103). Springer.

Orlando, G., Stoop, R., & Taglialatela, G. (2021d). Embedding dimension and mutual information. In G. Orlando, A. Pisarchik, & R. Stoop (Eds.), Nonlinearities in economics (pp. 105–108). Springer.

Orlando, G., Zimatore, G., & Giuliani, A. (2021e). Recurrence quantification analysis: Theory and applications. In G. Orlando, A. Pisarchik, & R. Stoop (Eds.), Nonlinearities in economics (pp. 141–150). Springer.

Orlando, G., Bufalo, M., & Stoop, R. (2022). Financial markets’ deterministic aspects modeled by a low-dimensional equation. Science and Reports, 12 (1693), 1–13.

Orlando, G., & Zimatore, G. (2020a). Business cycle modeling between financial crises and black swans: Ornstein–Uhlenbeck stochastic process vs Kaldor deterministic chaotic model. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science , 30 (8), 083129.

Orlando, G. (2018). Chaotic business cycles within a Kaldor-Kalecki framework . In: Pham, V. T., Vaidyanathan, S., Volos, C., Kapitaniak, T. (eds.). Nonlinear dynamical systems with self-excited and hidden attractors. Studies in systems, decision and control, vol. 133. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71243-7_6

Piscitelli, L., & Sportelli, M. C. (2004). A simple growth-cycle model displaying “Sil’nikov Chaos.” Economic complexity (Vol. 14, pp. 3–30). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Prescott, E. C. (1986). Theory ahead of business-cycle measurement. In Carnegie-Rochester conference series on public policy (vol. 25, pp. 11–44). Elsevier.

Rivot, S., & Trautwein, H.-M. (2020). Macroeconomic statics and dynamics in a historical perspective. European Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 27 (4), 471–475.

Della Rossa, F., Guerrero, J., Orlando, G., & Taglialatela, G. (2021). Applied spectral analysis. In G. Orlando, A. Pisarchik, & R. Stoop (Eds.), Nonlinearities in economics (pp. 123–139). Springer.

Rosser, J. B., Jr. (2013). A conceptual history of economic dynamics . Madison University.

Rössler, O. E. (1976). An equation for continuous chaos. Physics Letters A, 57 (5), 397–398.

Semmler, W. (1986). On nonlinear theories of economic cycles and the persistence of business cycles. Mathematical Social Sciences, 12 (1), 47–76.

Sharkovskij, A. (1964). Co-existence of cycles of a continuous map of the line into itself. Ukranian Math. Z., 16 , 61–71.

Sherman, H. J. (2014). The business cycle: Growth and crisis under capitalism . Princeton University Press.

Slutzky, E. (1937). The summation of random causes as the source of cyclic processes. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society , 5 (2), 105–146.

Sportelli, M. C. (2000). Dynamic complexity in a Keynesian growth-cycle model involving Harrod’s instability. Zeitschr. f. Nationalökonomie., 71 (2), 167–198.

Sportelli, M., & De Cesare, L. (2019). Fiscal policy delays and the classical growth cycle. Applied Mathematics and Computation, 354 , 9–31.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2018). Where modern macroeconomics went wrong. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 34 (1–2), 70–106.

Stoop, R. (2021). Signal processing . In G. Orlando, A. N. Pisarchik & R. Stoop (Eds.), Nonlinearities in economics. Dynamic modeling and econometrics in economics and finance (vol. 29). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70982-2_8

Taillardat, M., Mestre, O., Zamo, M., & Naveau, P. (2016). Calibrated ensemble forecasts using quantile regression forests and ensemble model output statistics. Monthly Weather Review, 144 (6), 2375–2393.

Veblen, T. (1904). The theory of business enterprise . Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Verhulst, P. (1847). Deuxième mémoire sur la loi d’accroissement de la population. Mémoires De L’académie Royale Des Sciences, Des Lettres Et Des Beaux-Arts De Belgique, 20 , 1–32.

Wang, K., Steyn-Ross, M. L., Steyn-Ross, D. A., Wilson, M. T., Sleigh, J. W., & Shiraishi, Y. (2014). Simulations of pattern dynamics for reaction-diffusion systems via simulink. BMC Systems Biology, 8 (1), 1–21.

Wicksell, K. (1898). Geldzins und Güterpreise. Eine Untersuchung über die den Tauschwert des Geldes bestimmenden Ursachen. Gustav Fischer, Jena, as quoted in Laidler, D. (1991), The golden age of the quantity theory . Princeton University Press.

Yoshida, H., & Asada, T. (2007). Dynamic analysis of policy lag in a Keynes-Goodwin model: Stability, instability, cycles and chaos. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 62 (3), 441–469.

Yoshida, H. (2021). From local bifurcations to global dynamics: Hopf systems from the applied perspective. In G. Orlando, A. N. Pisarchik, & R. Stoop (Eds.), Nonlinearities in economics. Dynamic modeling and econometrics in economics and finance (vol. 29). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70982-2_5

Zimatore, G., Fetoni, A. R., Paludetti, G., Cavagnaro, M., Podda, M. V., & Troiani, D. (2011). Post-processing analysis of transient-evoked otoacoustic emissions to detect 4 khz-notch hearing impairment–a pilot study. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research , 17 (6), MT41.

Zimatore, G., Garilli, G., Poscolieri, M., Rafanelli, C., Terenzio Gizzi, F., & Lazzari, M. (2017). The remarkable coherence between two Italian far away recording stations points to a role of acoustic emissions from crustal rocks for earthquake analysis. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science , 27 (4), 043101.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics and Finance, HSE University, 16 Soyuza Pechatnikov Street, St Petersburg, 190121, Russia

Giuseppe Orlando

Department of Mathematics, University of Bari, Via E. Orabona 4, 70125, Bari, Italy

Giuseppe Orlando & Mario Sportelli

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Giuseppe Orlando .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty of Business, Law and Social Sciences, Birmingham City University, Birmingham, UK

Vikas Kumar

Department of Regional Industrial Policy and Economic Security, Institute of Economics, Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Ekaterinburg, Russia

Evgeny Kuzmin

College of International Management, Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University, Beppu, Oita, Japan

Wei-Bin Zhang

Institute of Economics, Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Ekaterinburg, Russia

Yuliya Lavrikova

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Orlando, G., Sportelli, M. (2023). A Survey on Business Cycles: History, Theory and Empirical Findings. In: Kumar, V., Kuzmin, E., Zhang, WB., Lavrikova, Y. (eds) Consequences of Social Transformation for Economic Theory. EASET 2022. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-27785-6_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-27785-6_2

Published : 14 April 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-27784-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-27785-6

eBook Packages : Economics and Finance Economics and Finance (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

AP®︎/College Macroeconomics

Course: ap®︎/college macroeconomics > unit 2, the business cycle.

- Business cycles and the production possibilities curve

- Lesson summary: Business cycles

- Business cycles

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Video transcript

- What is Accounting?

- What Is a General Ledger?

- What are Accounts Receivable?

- Balance Sheet vs Income Statement

- What are Real Accounts?

- What is Working Capital?

- Net Sales vs Gross Sales

- Overview of Financial Controls

- Financial Accounting

- Managerial Accounting

- Cost Accounting

- Cloud Accounting

- Project Accounting

- Best Accounting Software

- Free Accounting Software

- Nonprofit Accounting Software

- Cloud-Based Accounting Software

- Billing and Invoicing Software

- Payroll Software for Small Businesses

- QuickBooks Alternatives

- QuickBooks vs FreshBooks

- QuickBooks Time Pricing

- FreshBooks Pricing

- NetSuite Pricing

- Calculate Customer Acquisition Costs

- Calculate Accumulated Depreciation

- Accounts Receivable Turnover Ratio

- Calculate Cost of Goods Manufactured

- Calculate Cost of Goods Sold

- Calculate Job Order Costing

- Debt Service Coverage Ratio

- Calculate Unit Economics

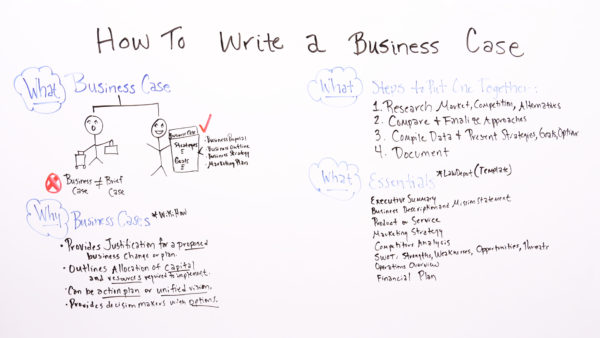

Business Cycle: Definition and 6 Stages

The economy of every country undergoes periodic fluctuations. Although they are repetitive, it is impossible to avoid them .

Many factors cause these fluctuations, such as GDP, employment, consumer spending, real income, production, and aggregate output.

Smart business owners and policymakers study these economic cycles and patterns to help them make informed financial decisions. Preparing for these periodic fluctuations ensures your business thrives even in unstable economic conditions.

This article explains the workings and stages of the business cycle.

Let’s get started.

Definition and Example of the Business Cycle

The business cycle, otherwise known as the economic cycle or trade cycle, is a term that depicts the increase or decrease in economic activities involving production, trade, and consumption over time.

In other words, a business cycle involves expansions occurring simultaneously in multiple economic activities followed by recessions (general contractions).

Business cycles help measure the downward and upward movement of the amount of productivity of businesses, employees, and consumers alongside the growth cycle of the economy over time.

As the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fluctuates around its natural long-term growth rate, economic cycles help explain the expansion and contraction phenomena that characterize an economy over time.

Example of the Business Cycle

Every business cycle must have passed at least a single boom and a single contraction sequentially.

In recent decades, major economies and businesses have increased their production level. It has led to the need for more employees and has translated to less spending money. As a result, companies make more profits that help them focus on growth.

In the reverse case, when the economy is slow, there is a decline in the number of employees needed, which translates to a decrease in consumer spending. As a result, companies have less focus on growth.

To fully understand the business cycle, you need to understand two key terms: economic expansion and contraction.

Economic expansion in economic analysis is the rate at which production and consumption change positively, while economic contraction is inversely the rate at which production and consumption change negatively.

The United States as a Case Study

In the United States, for example, the end and start of a business cycle are defined and measured by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), a non-profit business cycle dating committee.

The NBER uses quarterly GDP growth rates to determine the current business or economic cycle. It waits till it gets enough economic data to prevent a situation where it would have to make revisions to the business cycle chronology.

Businesses are affected by the expansion and contraction of the economy as they also go through their own distinct set of ups and downs in their trade cycle.

This situation puts the management of the business in a position to devise strategic financial decisions to deal with these challenges head-on. Understanding the time of the business cycle helps businesses make correct investment decisions.

6 Stages of the Business Cycle

The business cycle illustrates how a nation's aggregate economy moves over time, showing ups and downs.

Business cycles are characterized by economic expansions followed by sustained periods of economic recessions. In a business cycle diagram, the straight line is the steady growth line, and every business cycle moves about the line.

All business cycles pass through six distinct identical phases.

1. Expansion Stage

The first stage in every business cycle is the expansion phase. Expansion begins when there is a visible increase in positive economic indicators such as employment, demand, and supply of goods and services, wages, profits, personal income, national income, and output.

Economic expansion is a period of relative growth in a nation's economy. During this phase, productivity increases, as visible as an upward movement in the yield curve.

The economic recovery phase is another name for the expansion stage. It occurs after an economy has been through a contraction for an extended period.

This phase is characterized by debtors paying off their debts on time, high velocity of money supply, and high investments. It continues as long as the economic conditions remain favorable.

GDP growth is the economic measurement index that indicates economic output increase during the expansion phase. When economic output rises, businesses and organizations hire more workers and open up more strategic business units .

The goal of the federal reserve bank during the expansion phase is to keep inflation around 2% for a healthy economy.

During this stage, the stock market also experiences rising prices as investors grow in confidence, businesses receive more funding, and consumer confidence is at an all-time high.

The expansion phase is close to its end or overheating state when the economy begins to grow too fast, which is visible in the employment rate emerging below the natural rate and inflation increasing with stock prices rising to the point of being overvalued.

A country experiences a healthy expansion when the GDP growth rate is in the 2 – 3% range, inflation maintains its 2% target, and the unemployment rate is between 3.5 – 4.5%, with the stock market supporting a bullish run.

2. Peak Stage

The saturation point or peak an economy reaches is the second stage of the business cycle. It is visible by the economic indicator's inability to grow further as it has attained its maximum growth limit.

During the peak phase, prices are at their highest, marking the reversal point in the trend of economic growth as consumers tend to make changes to their budget structure.

At the peak phase, all expansionary indicators begin to level as the economy prepares to transition into the contraction or recession phase.

The peak is visible graphically as the highest portion of the yield curve before the economy begins to experience a downward spiral characterized by a continuous decline in GDP growth below the 2% healthy mark.

Once the nation's economic numbers start growing out of their healthy ranges, the economy is most vulnerable as any factors can throw it off balance at this stage.

Companies expanding recklessly, overconfident investors, buying up of assets, and a significant price increase not supported by their underlying value are several factors that can throw the country's economy off balance in the peak stage.

With no room left for growth and nowhere to go but down, the economy falls into the recession or contraction phase after it has reached the peak and end of the expansion phase. It indicates that prices and production have reached their respective limits.

3. Recession or Contraction Stage

The recession stage comes after the peak phase and is evident by a rapid and steady decline in the demand for goods and services.

Producers in the economy do not readily notice this rapid and steady decline as they go about their regular daily production numbers. Thus creating a situation of excess supply in the market which tends to bring down prices abruptly.

Apart from prices, other positive economic indicators also witness a significant fall, such as income, wages, and output.

A recession graphically spans the time from the peak to the trough, as it is the period when economic activity is at its lowest.

During the recession, unemployment numbers rise, the stock market enters a bearish trend, and the GDP growth is below the 2% healthy value, forcing businesses to cut back on their economic activities.

For an economy to be in recession, the GDP has to have shown a significant decline for two consecutive quarters. It does not return to its original shape and size immediately after the recession phase is over.

4. Depression Stage

After the contraction phase, the nation's economy experiences a significant rise in unemployment across all facets of the economy.

Besides the increase in unemployment, there is also a decline in the growth index for the country's economy, as is evident in its fall below the steady growth line. At this stage of the nation's economy, the country is in its depression stage.

5. Trough Stage

The trough stage is the fifth phase of the business cycle. It is characterized by a decrease in the rate of adverse change in the nation's declining GDP until it eventually turns positive.

In economic terms, a trough represents the negative saturation point for an economy as there is an extensive depletion of national income and expenditure during this stage of the business cycle.

This phase begins when the nation's economy transitions from its contraction phase into its expansion and is represented graphically as the lowest point of the yield curve.

The rebound experienced during the trough phase is not always straight or quick as it continues steadily until the economy reaches full economic recovery.

6. Recovery Stage

After the through phase, a nation's economy enters the recovery stage. This stage is characterized by a significant turnaround in the country's economy, evident by its recovery from its negative growth rate.

Due to prices at their lowest point, demand starts to witness an increase. Consequently, supply and industrial production increase as the population's attitude toward investment and employment is now positive.

During the recovery phase, employment also begins to rise as the accumulated cash balances with the bankers make lending show positives.

Depreciated capital is readily replaced, providing unique opportunities for investment in the production process, which continues until the nation's economy returns to steady growth.

Economic Indicators for Measuring the Business Cycle

Economic indicators used to measure the productivity of a business cycle are very extensive as they are based on financial data of the nation's economy.

Here are the three common categories of economic business cycle indicators.

1. Leading Business Cycle Indicators

A leading business cycle indicator measures aggregate economic activity and predict a business cycle's beginning phase.

The leading business cycle indicators are the average weekly work hours in manufacturing, stock prices, factory orders of goods, index of customer expectations, average weekly claims for unemployment insurance, interest rate spread, and housing permits.

Usually, changing these indicator metrics could significantly point towards a potential shift in the business cycle. Leading economic cycle indicators get the most attention due to their tendency to predict a shift in advance of a business cycle.

These indicators work best alongside coincident and lagging indicators in the same framework. They provide a more thorough understanding of the true nature of economic activity.

2. Lagging Business Cycle Indicators

Lagging economic cycle indicators are designed as confirmatory indicators, confirming the trends predicted by leading indicators. Generally, lagging indicators usually experience a significant shift witnessed after an economy has entered a period of fluctuation.

The average length of employment, labor cost per unit of manufacturing output, consumer price index, commercial lending activity, and average prime rate are all lagging indicators components.

3. Coincident Business Cycle Indicators

Coincidental economic cycle indicators measure the aggregate economic activity that is subject to changes as the business cycle progresses.

As one of the three components of economic business cycle indicators, coincident cycle indicators are economic research tools that help measure the real income of consumers in the market, among other factors.

The unemployment rate, personal finance levels, and industrial production are index components for coincident business cycle indicators.

How is the Business Cycle Influenced?

The fact that periodic business cycles move in phases does not mean they cannot be influenced. Countries can manage the various stages of a business cycle through monetary and fiscal policies.

1. Government Legislations

Generally, the government monitors the business cycle and devises a series of legislations to influence their country's business cycle, primarily around changes in tax and spending.

The government's fiscal policy is designed to increase taxes and reduce spending during an economic expansion, lower taxes and increase spending during an economic contraction. This policy is called the expansionary fiscal policy.

2. Monetary Policy

The Fed and the country's central bank use monetary policy tools that help implement needed changes to the country's interest rates.

This policy helps curtain lending and borrowing by businesses, banks, and consumers and influences the business cycle through rates that target inflation and unemployment.

When the country has slipped from its expansionary phase into a contraction phase, the central bank lowers its target interest rates to encourage borrowing in a request to end the contraction phase.

This policy by the central bank is termed an expansionary monetary policy. It is configured to be the turning point that pushes the business cycle back into the expansionary phase.

In unique situations, when a country's economy is growing faster than the country can afford, the central bank of such a country steps in. It offers preventive measures to contain the fast-growing economy.

The nation's central bank raises its target interest rates to discourage borrowing and spending, curbing the growth of the nation's economy.

This policy by the central bank is termed a contractionary monetary policy as its main aim is to contract economic activity spread and economic output to contain the economic expansion.

Business Cycle FAQ

No defined time frame exists for how long a business cycle should last. It varies from being short for months to being long, lasting several years. According to the U.S Government National Bureau of Economic Research, the time frame average for business cycles in America to play out is around five and a half years since World War II. Periods of expansion are generally more prolonged than those of contractions. As observed since WWII by the Congressional Research Service, the economic expansion period lasted 65 months on average, while the financial contraction period lasted about 11 months in the U.S.

Ranging from technological innovations to wars, a wide variety of factors can shape the business cycle. According to the Congressional Research Service, the critical influence remains on aggregate demand and aggregate supply within an economy. Contraction occurs when demand decreases and when demand increases, expansion occurs.

The economic expansion that occurred between 2009-2020 in the U.S went down in history as the longest expansion and the latest for a record 128 months. The U.S reached the peak of this longest expansion in February 2020. It was characterized by many variables in an economy fluctuating over time, leading to a shift in economic and non-economic factors.

Was This Article Helpful?

Martin luenendonk.

Martin loves entrepreneurship and has helped dozens of entrepreneurs by validating the business idea, finding scalable customer acquisition channels, and building a data-driven organization. During his time working in investment banking, tech startups, and industry-leading companies he gained extensive knowledge in using different software tools to optimize business processes.

This insights and his love for researching SaaS products enables him to provide in-depth, fact-based software reviews to enable software buyers make better decisions.

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Business Cycle Synchronization and Vertical Trade Integration: A Case Study of the Eurozone and East Asia

Business cycle synchronization is one of the crucial conditions for a currency union to be successful. Frankel and Rose (1998) argued that increased trade after euro adoption would increase business cycle synchronization ex-ante. However, the fallout of the Eurozone forcefully demonstrated that their optimistic prediction did not turn out to be true. One thing Frankel and Rose (1998) did not examine is how different types of trade (inter vs. intra, vertical vs. horizontal, etc.) intensify/dampens business cycle synchronization. In this light, this paper empirically examines how different types of trade affect business cycle synchronization in what way. This study takes two major economic blocs that have been going under rapid economic integrations: The original Eurozone members and East Asia – integration of former mainly developing by European government initiative and the latter naturally forming by the global supply chain and associated product segmentation. Comparing these two very different economic blocs with very different factor endowment structures would give us a more convincing answer to how different types of trade can influence business cycle synchronization differently. Our key finding is that, on the contrary to Frankel and Rose (1998) , the impact of increased trade intensity on business cycle co-movement is ambiguous. The impact of trade on business cycle synchronization depends on types of trade. Intra-industry trade, especially vertical intra-industry trade which is rapidly growing in East Asia, has a strong positive effect on business cycle synchronization while inter-industry trade does not.

Article Notes

The earlier version of this paper has been published by De Nederlandsche Bank (the Dutch Central Bank). This paper does not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of De Nederlandsche Bank. The author acknowledges the valuable comments from Henry Sunghyun Kim, Ad Stockman, Peter Lafourcade and Gabriele Galati. The author also thank Rob Vet, Martin Admiraal, and Rene Bierdrager for excellent data support.

Sample countries and their GDP per capita.

Note: Data is as of 2016.

GDP per capita is constant on 2010 USS.

Data from database: World Development Indicators (Data of Taiwan is from FRED database)

Change in Intra-industry (X-axis) and vertical intra-industry (Y-axis) of the Eurozone and East Asia in 10-year intervals.

Source: Author’s calculation based on OECD-ITCS database. For calculation, please refer to the main text.

Correlation of business cycle extracted by different methods.

Source: Author’s calculation

Anderson, M. (2003). “Empirical Intra-Industry Trade: What We Know and What We Need to Know,” mimeo , Institute for Canadian Urban Research Studies Simon Fraser University. Search in Google Scholar

Ando, M. 2006. “Fragmentation and Vertical Intra-Industry Trade in East Asia.” The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, Elsevier 17 (3): 257–281. Search in Google Scholar

Artis, M., and W. Zhang. 1999. “Further Evidence on the International Business Cycle and the ERM: Is There a European Business Cycle?.” Oxford Economic Papers 51: 120–132. Search in Google Scholar

Artis, M., and W. Zhang. 2007. “International Business Cycles and the ERM.” International Journal of Finance and Economics 2 (1): 1–16. Search in Google Scholar

Backus, D., P. Kehoe, and F. Kydland. 1992. “International Real Business Cycles.” Journal of Political Economy 100 (4): 745–775. Search in Google Scholar

Baldwin, R., F. Skudelny, and T. Daria. (2005). “Trade Effects of the Euro: Evidence from Sectoral Data,” ECB Working Paper Series 0446, European Central Bank. Search in Google Scholar

Baxter, M., and M. Crucini. 1995. “Business Cycles and the Asset Structure of Foreign Trade.” International Economic Review 36 (4): 821–854. Search in Google Scholar

Baxter, M., and R. King. 1999. “Measuring Business Cycles: Approximate Band-Pass Filters for Economic Time Series.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 81 (4): 575–593. Search in Google Scholar

Baxter, M., and M. Kouparitsas. 2005. “Determinants of Business Cycle Co-Movement: A Robust Analysis.” Journal of Monetary Economics 52 (1): 113–157. Search in Google Scholar

Bayoumi, T., and B. Eichengreen. (1992). “Shocking Aspects of European Monetary Unification,” NBER Working Paper No. 3949. Search in Google Scholar

Bayoumi, T., and B. Eichengreen. 1996. "Ever Closer to Heaven? An Optimum-Currency-Area Index for European Countries," Center for International and Development Economics Research (CIDER) Working Papers C96-078 , University of California at Berkeley. Search in Google Scholar

Bun, M., and F. Klaassen. 2007. “The Euro Effect on Trade Is Not as Large as Commonly Thought.” Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 69: 473–496. Search in Google Scholar

Calderon, C., A. Chong, and S. Ernesto. 2007. “Trade Intensity and Business Cycle Synchronization: Are Developing Countries Any Different?.” Journal of International Economics 71 (1): 2–21. Search in Google Scholar

Cortinhas, C. 2007. “Intra-Industry Trade and Business Cycles in ASEAN.” Applied Economics 39 (7): 893–902. Search in Google Scholar

Dai, Y. (2014). “Business Cycle Synchronization in Asia: The Role of Financial and Trade Linkages,” Working Papers on Regional Economic Integration 139, Asian Development Bank. Search in Google Scholar

De Haan, J., R. Inklaar, and R. Jong-a-Pin. 2008. “Will Business Cycles in the Euro Area Converge? a Critical Survey of Economic Research.” Journal of Economic Surveys 22 (2): 234–273. Search in Google Scholar

European Central Bank. (2017). Financial Integration in Europe , May 2017. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/ecb.financialintegrationineurope201705.en.pdf (Retrieved on 26 August 2017) Search in Google Scholar

Fidrmuc, J., and I. Korhonen. 2010. “The Impact of the Global Financial Crisis on Business Cycles in Asian Emerging Economies.” Journal of Asian Economics 21 (3): 293–303. Search in Google Scholar

Frankel, J. 2008. “The Euro at Ten: Why Do Effects on Trade between Members Appear Smaller than Historical Estimates among Smaller Countries.” Voxeu 24 Dec 2008. Search in Google Scholar

Frankel, J. (2017). “Systematic Managed Floating,” NBER Working Paper , 23663. Search in Google Scholar

Frankel, J., and A. Rose. 1998. “The Endogeneity of the Optimum Currency Area Criteria.” Economic Journal 108 (449): 1009–1025. Search in Google Scholar

Gabrisch, H., and M. Segnana. (2002). “Why Is Trade between the European Union and the Transition Economies Vertical?” Department of Economics Working Papers 0207, University of Trento, Italia. Search in Google Scholar

Gabrisch, H., & S. Maria. 2003. Vertical and horizontal patterns of intra-industry trade between EU and candidate countries, ch12. Germany: IWH (Halle Institute of Economic Study). Search in Google Scholar

Giannone, D., M. Lenza, and L. Reichlin. (2009). “Business Cycles in the Euro Area,” CEPR Discussion Paper , 7124. Search in Google Scholar

Greenaway, D., Robert C. Hine, and M. Chris. 1995. “Vertical and Horizontal Intra-Industry Trade: A Cross Industry Analysis for the United Kingdom.” Economic Journal 105 (433): 1505–18. Search in Google Scholar

Grubel, H., and P. Lloyd. 1971. “The Empirical Measurement of Intra-Industry Trade.” Economic Record 47 (4): 494–517. Search in Google Scholar

Harvey, A., and A. Jager. 1993. “Detrending, Stylized Facts and Business Cycle.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 8 (3): 231–247. Search in Google Scholar

Hirata, H., A. Kose, and C. Otrok. (2013), “Regionalization Vs. Globalization,” IMF Working Paper No. 1319. Search in Google Scholar

Hirata, H., and K. Otsu. 2016. “Accounting for the Economic Relationship between Japan and the Asian Tigers.” Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 41 (C): 57–68. Search in Google Scholar

Imbs, J. 2004. “Trade, Specialization and Synchronization.” Review of Economics and Statistics 86 (3): 723–734. Search in Google Scholar

Imbs, J. 2006. “The Real Effects of Financial Integration.” Journal of International Economics 68 (2): 296–324. Search in Google Scholar

Imbs, J. 2011. “What Happened to the East Asian Business Cycle?.” Chapter 11 In The Dynamics of Asian Financial Integration , edited by M. Devereux, P. Lane, C.Y. Park and S.J. Wei, 284–310. London: Taylor and Francis Group. Search in Google Scholar

Inklaar, R., and J. De Haan. 2001. “Is There Really a European Business Cycle? a Comment.” Oxford Economic Papers 53: 215–220. Search in Google Scholar

Inklaar, R., R. Jong-A-Pin, and J. De Haan. 2008. “Trade and Business Cycle Synchronization in OECD Countries - a Re-Examination.” European Economic Review 52 (4): 646–666. Search in Google Scholar

Inklaar, R., and M. Timmer. 2007. “International Comparisons of Industry Output, Inputs and Productivity Levels: Methodology and New Results.” Economic Systems Research, Taylor & Francis Journals 19 (3): 343–363. Search in Google Scholar

Jansen, J., and A. Stokman. 2014. “International Business Cycle Co-Movement: The Role of FDI.” Applied Economics 46 (4): 383–393. Search in Google Scholar

Jung, J. 2008. “Regional Financial Cooperation in Asia: Challenges and Path to Development.” In Regional Financial Integration in Asia: Present and Future , Vol. 42, 120–135. Bazel: Bank for International Settlements. Search in Google Scholar

Kalemli-Ozcan, S., E. Papaioannou, and J. Peydró. (2009). “Financial Regulation, Financial Globalization and the Synchronization of Economic Activity,” NBER Working Paper 14887. Search in Google Scholar

Kawecka-Wyrzykowska, E. (2009). “Evolving Pattern of Intra-Industry Trade Specialization of the New Member States (NMS) of the EU: The Case of Automotive Industry” No. 364. Directorate General Economic and Financial Affairs (DG ECFIN), European Commission. Search in Google Scholar

Kenen, P. 1969. “Theory of Optimum Currency Areas: An Eclectic View.” In Monetary Problems of the International Economy , edited by R. Mundell and A. Swoboda. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. Search in Google Scholar

Kim, S., and S.H. Kim. 2013. “International Capital Flows, Boom-Bust Cycles, and Business Cycle Synchronization in the Asia Pacific Region.” Contemporary Economic Policy 31: 191–211. Search in Google Scholar

Kimura, F. 2006. “International Production and Distribution Networks in East Asia: Eighteen Facts, Mechanics, and Policy Implications.” Asian Economic Policy Review 1 (2): 326–344. Search in Google Scholar