- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Federalist Papers

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 22, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

The Federalist Papers are a collection of essays written in the 1780s in support of the proposed U.S. Constitution and the strong federal government it advocated. In October 1787, the first in a series of 85 essays arguing for ratification of the Constitution appeared in the Independent Journal , under the pseudonym “Publius.” Addressed to “The People of the State of New York,” the essays were actually written by the statesmen Alexander Hamilton , James Madison and John Jay . They would be published serially from 1787-88 in several New York newspapers. The first 77 essays, including Madison’s famous Federalist 10 and Federalist 51 , appeared in book form in 1788. Titled The Federalist , it has been hailed as one of the most important political documents in U.S. history.

Articles of Confederation

As the first written constitution of the newly independent United States, the Articles of Confederation nominally granted Congress the power to conduct foreign policy, maintain armed forces and coin money.

But in practice, this centralized government body had little authority over the individual states, including no power to levy taxes or regulate commerce, which hampered the new nation’s ability to pay its outstanding debts from the Revolutionary War .

In May 1787, 55 delegates gathered in Philadelphia to address the deficiencies of the Articles of Confederation and the problems that had arisen from this weakened central government.

A New Constitution

The document that emerged from the Constitutional Convention went far beyond amending the Articles, however. Instead, it established an entirely new system, including a robust central government divided into legislative , executive and judicial branches.

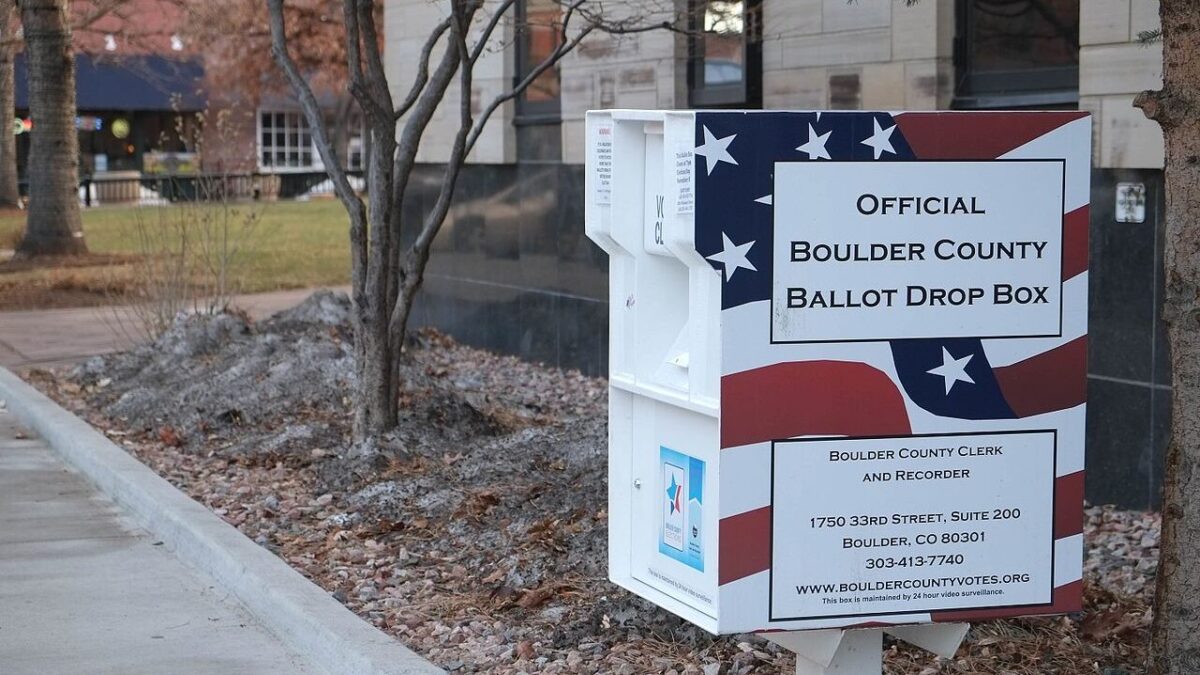

As soon as 39 delegates signed the proposed Constitution in September 1787, the document went to the states for ratification, igniting a furious debate between “Federalists,” who favored ratification of the Constitution as written, and “Antifederalists,” who opposed the Constitution and resisted giving stronger powers to the national government.

The Rise of Publius

In New York, opposition to the Constitution was particularly strong, and ratification was seen as particularly important. Immediately after the document was adopted, Antifederalists began publishing articles in the press criticizing it.

They argued that the document gave Congress excessive powers and that it could lead to the American people losing the hard-won liberties they had fought for and won in the Revolution.

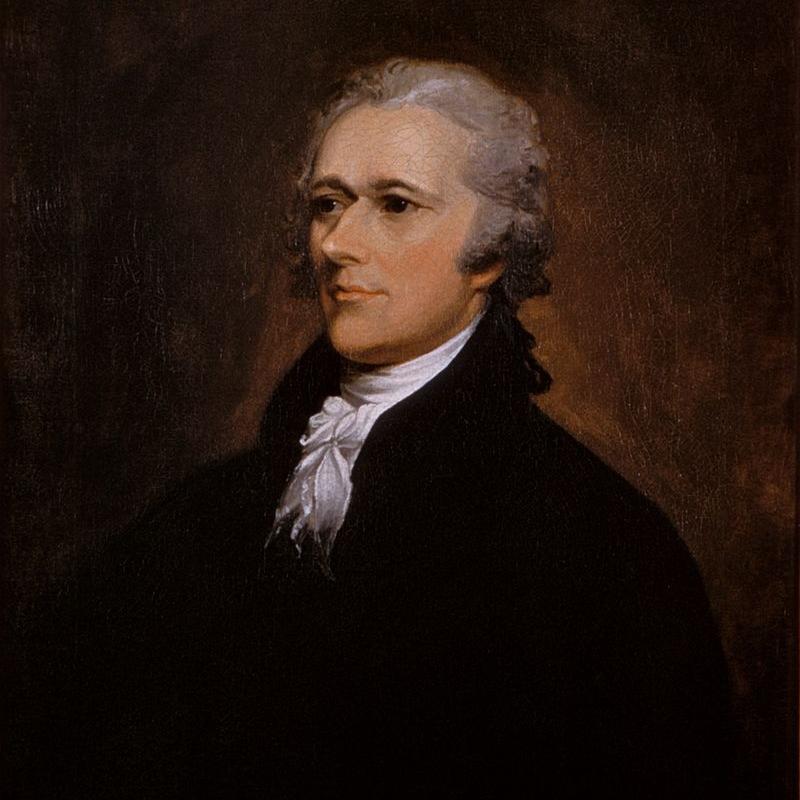

In response to such critiques, the New York lawyer and statesman Alexander Hamilton, who had served as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, decided to write a comprehensive series of essays defending the Constitution, and promoting its ratification.

Who Wrote the Federalist Papers?

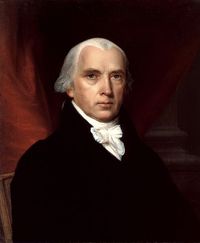

As a collaborator, Hamilton recruited his fellow New Yorker John Jay, who had helped negotiate the treaty ending the war with Britain and served as secretary of foreign affairs under the Articles of Confederation. The two later enlisted the help of James Madison, another delegate to the Constitutional Convention who was in New York at the time serving in the Confederation Congress.

To avoid opening himself and Madison to charges of betraying the Convention’s confidentiality, Hamilton chose the pen name “Publius,” after a general who had helped found the Roman Republic. He wrote the first essay, which appeared in the Independent Journal, on October 27, 1787.

In it, Hamilton argued that the debate facing the nation was not only over ratification of the proposed Constitution, but over the question of “whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.”

After writing the next four essays on the failures of the Articles of Confederation in the realm of foreign affairs, Jay had to drop out of the project due to an attack of rheumatism; he would write only one more essay in the series. Madison wrote a total of 29 essays, while Hamilton wrote a staggering 51.

Federalist Papers Summary

In the Federalist Papers, Hamilton, Jay and Madison argued that the decentralization of power that existed under the Articles of Confederation prevented the new nation from becoming strong enough to compete on the world stage or to quell internal insurrections such as Shays’s Rebellion .

In addition to laying out the many ways in which they believed the Articles of Confederation didn’t work, Hamilton, Jay and Madison used the Federalist essays to explain key provisions of the proposed Constitution, as well as the nature of the republican form of government.

'Federalist 10'

In Federalist 10 , which became the most influential of all the essays, Madison argued against the French political philosopher Montesquieu ’s assertion that true democracy—including Montesquieu’s concept of the separation of powers—was feasible only for small states.

A larger republic, Madison suggested, could more easily balance the competing interests of the different factions or groups (or political parties ) within it. “Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests,” he wrote. “[Y]ou make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens[.]”

After emphasizing the central government’s weakness in law enforcement under the Articles of Confederation in Federalist 21-22 , Hamilton dove into a comprehensive defense of the proposed Constitution in the next 14 essays, devoting seven of them to the importance of the government’s power of taxation.

Madison followed with 20 essays devoted to the structure of the new government, including the need for checks and balances between the different powers.

'Federalist 51'

“If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” Madison wrote memorably in Federalist 51 . “If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.”

After Jay contributed one more essay on the powers of the Senate , Hamilton concluded the Federalist essays with 21 installments exploring the powers held by the three branches of government—legislative, executive and judiciary.

Impact of the Federalist Papers

Despite their outsized influence in the years to come, and their importance today as touchstones for understanding the Constitution and the founding principles of the U.S. government, the essays published as The Federalist in 1788 saw limited circulation outside of New York at the time they were written. They also fell short of convincing many New York voters, who sent far more Antifederalists than Federalists to the state ratification convention.

Still, in July 1788, a slim majority of New York delegates voted in favor of the Constitution, on the condition that amendments would be added securing certain additional rights. Though Hamilton had opposed this (writing in Federalist 84 that such a bill was unnecessary and could even be harmful) Madison himself would draft the Bill of Rights in 1789, while serving as a representative in the nation’s first Congress.

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Ron Chernow, Hamilton (Penguin, 2004). Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 (Simon & Schuster, 2010). “If Men Were Angels: Teaching the Constitution with the Federalist Papers.” Constitutional Rights Foundation . Dan T. Coenen, “Fifteen Curious Facts About the Federalist Papers.” University of Georgia School of Law , April 1, 2007.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Contact: ✉️ [email protected] ☎️ (803) 302-3545

Who wrote the federalist papers, what was the aim of the federalist papers.

Opinion columns in newspapers or online aren’t always the best way of convincing people to share a viewpoint. There is always the risk that political biases will end up causing greater tensions or divisions. Still, a well-written piece can raise enough questions and shift the balance in a debate.

This was the aim of the Federalist Papers, a series of essays published between October 1787 and May 1788, to persuade New Yorkers to change their minds about rejecting the proposed United States Constitution.

Not all were convinced, but the essays did help, and arguably, this wouldn’t have happened with less knowledgeable and skilled writers behind the venture. So, who wrote the Federalist Papers, and why were they anonymous at the time of their publication?

Authors of the Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers were not the work of a single author but rather a group of men acting together to put forth convincing arguments in favor of the constitution via a series of well-thought-out essays. Alexander Hamilton , James Madison, and John Jay created a impressive number of installments for the people of New York to help them to see the value in the Federalist way of thinking.

Hamilton and Madison were prominent figures at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia , where the new constitution was drafted. In collaboration with Jay, they produced a collection of work that is still revered as a key historical document in the evolution of the United States.

Who Was Publius?

Initially, Hamilton, Madison, and Jay preferred to remain anonymous and used a pseudonym for their publications. It made sense for the three writers of these famous essays to retain their anonymity in order to let the writing speak for itself. Readers might not have given as much attention if they knew who the authors were.

At the same time, this sort of shared identity meant that it wouldn’t have been immediately clear who wrote which piece. There were differences in style and message to a point, but it remained a group effort with a common goal. What’s more, there was a high level of secrecy around creating and ratifying the constitution, where many documents were destroyed.

The pen name adopted, Publius, was a nod to a key figure involved in founding the Roman Empire – Publius Valerius Publicola. It appears that Hamilton saw something of himself and his peers in Publius. The name stuck and was attached to the essays in their serialized form and the bound version created in 1788.

Authors Role in the Creation of the Constitution

The need for the Federalist Papers came about from the creation of the constitution during the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Delegates from across the 13 states – with the exception of Rhode Island – descended on the city for months of debates. The current Articles of Confederation were not fit for purpose and needed practical adaptions to better serve the nation. The result was an entirely new United States Constitution. This was passed to Congress for approval before the requisite ratification process .

The three members of Publius were ardent Federalists that supported the need for a more centralized form of government. But, there were plenty of Anti-Federalists that weren’t keen to sign. The Federalist Papers gave the authors the chance to defend the ideas within the proposed constitution and explain why the original Articles of Confederation had to change.

The writers began their series of essays in October of 1787 , not long after the constitution was sent out for ratification. Their target was New York, a vitally important state because of its population and wealth, and one the United States couldn’t afford to lose.

The papers became a series in two leading newspapers for all to read in the hope of swaying the state and speeding up the ratification process. This turned into a long-running series of essays with 85. As the essays continued to be published, many states signed, and the document achieved the majority needed for ratification, but the remaining states held out.

Alexander Hamilton and the Federalist Papers

The man most famous for his role in the creation of the Federalist Papers was Alexander Hamilton, who was the head of the project in more ways than one. It was his idea to create the series to advocate for the new constitution. He was also responsible for bringing in the other two participants, creating the Publius pseudonym, and penning the majority of the essays in the series.

Interestingly, he is said to have had little influence at the Constitutional Convention compared to Madison. He also held strong opinions on centralized government and a preference for British models that didn’t go down well with other delegates. Yet, he eventually found his way onto the Committee of Style and Arrangement with William Samuel Johnson, Gouverneur Morris, James Madison , and Rufus King.

Hamilton was a Delegate to the Congress of the Confederation from New York before becoming Secretary of the Treasury under President George Washington in 1789. He worked on the creation of the central bank and the nation’s war debts – issues detailed in the constitution.

Was Hamilton the Most Influential Contributor?

It is widely accepted that Alexander Hamilton wrote 51 of the 85 essays. The pieces were often split into themes, where the authors could continue to develop ideas and write more persuasive arguments about key areas of the constitution. Hamilton was also responsible for the opening piece and the all-important Federalist 84 that discussed the Bill of Rights.

It should be noted that when the papers were first compiled as a bound edition under the Publius name, it was Alexander Hamilton that saw to the edits and corrections. This suggests a keen desire to create the most persuasive and accurate portrayal of their argument right to the end.

Federalist 84 and the Bill Of Rights

Despite the best efforts of Publius to prove their point, there was still discontent among Anti-Federalists in the states yet to ratify. They weren’t convinced about signing away the rights and freedoms of their people by giving a centralized federal government more power. Their proposal was simple. They wanted a Bill of Rights .

This was an idea tabled during the Constitutional Convention but disregarded by the final framers. They deemed it unnecessary when there were strong clauses about citizens’ freedoms and unwritten rights. Alexander Hamilton was strongly opposed to the Bill of Rights and detailed his arguments in Federalist 84.

Despite all this, the Federalists eventually had to concede and give assurances that Congress would work on a Bill from its first session. This convinced New York and other resistant states to ratify the document. An interesting note here is that Publius member Madison was influential in creating that Bill of Rights in his new role in Congress in 1789.

Get Smarter on US News, History, and the Constitution

Join the thousands of fellow patriots who rely on our 5-minute newsletter to stay informed on the key events and trends that shaped our nation's past and continue to shape its present.

Check your inbox or spam folder to confirm your subscription.

The Role of James Madison

Alexander Hamilton wanted to bring in the best possible writers for the job, and he chose James Madison and John Jay. James Madison is a name we know well as a later President of the United States. Following the creation of the Federalist Papers, he would also become a member of the United States House of Representatives from Virginia, Secretary of State under Thomas Jefferson , and finally President in 1809.

Despite his links to Virginia rather than New York, like the others, Madison was an ideal fit for the role. He was a passionate Federalist keen to express his opinions and the man with the longest involvement in the constitutional process. He arrived in Philadelphia eleven days before most other delegates with speeches prepared and was eager to set the convention’s agenda as it progressed.

The Lesser-Known John Jay

John Jay is perhaps the least well-known of all of the writers of the Federalist Papers despite his political acumen. His compatriots had a stronger say in the creation and final draft of the constitution, but Jay had an abundance of political experience.

He was not as heavily involved in the scheme as his peers due to health issues, having developed rheumatism, which impeded his writing ability. He started strong, writing the second, third, fourth, and fifth on the subject of “Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence.” He then returned to write Federalist 64 on the role of the Senate in the creation of foreign treaties.

Before the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, Jay had been influential in the First and Second Continental Congress . He was president of the latter for a year before becoming the United States Minister to Spain, Secretary of Foreign Affairs, Acting Secretary of State, Governor of New York, and then the first Chief Justice. Again, a strong New York connection is significant with regards to his role in Publius.

Was Gouverneur Morris an Author of the Federalist Papers?

There is a fourth figure that runs the risk of being forgotten in relation to the Federalist Papers. While Gouverneur Morris was not one of the contributing authors to the serialized essays, he was considered by Hamilton for the role. This comes as no surprise considering his influence at the Constitutional Convention. He would have been a good fit for the Publius collective because of his political knowledge and links to New York. Later, he would act as the United States Minister to France and Senator for New York.

Morris is one of the most important founders related to the creation of the constitution and was responsible for writing the preamble. His signature can be found on the constitution and the Articles of Confederation that preceded it. He introduced the idea of the people becoming citizens of the United States rather than their respective home states. He was also highly influential at the Constitutional Convention, making more speeches than any other delegate.

When Were the Identities of the Authors Revealed?

For quite some time, nobody knew who was behind the Publius name, and the writers kept that secret long after the ratification of the constitution. The bound collection of papers retained the pseudonym to protect their identities and further the cause in its first edition. The names weren’t officially revealed until decades later, with a new edition in 1818. Madison amended this version, and the decision was made to attribute the work to its true authors.

In doing so, they cleared up the mystery and made the publication more interesting. Historians could now see which author focused on which subject, the language used, and the ratio of pieces written. Hamilton would not live to see this or any praise for his work as he died in 1804.

The attributions on the documents also show the importance of the pseudonym in the first place. There is some dispute over exactly who wrote what. While Hamilton is now credited with 51 of the 85, there are asterisks by the name where it is believed he had assistance from Madison.

Madison would challenge the idea that he was only responsible for 29 because of these contributions. Had the trio kept their names in place instead of working as the Publius collective, there may have been more in-fighting and issues getting to that grand total of 85.

The Legacy of the Federalist Papers Writers Today

The work of these three men, with their questionable attributions, is still available to view online. You can see how these men argued for their case and detailed the need for a shift from the Articles of Confederation to the new constitution. However influential the essays were at the time, there is no doubt that they hold an important place in American history today.

Alicia Reynolds

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Free Pocket Constitution

Why were the federalist papers written, all about the declaration of independence, trump’s letter to pelosi pdf (original), please enter your email address to be updated of new content:.

© 2023 US Constitution All rights reserved

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 3

- The Articles of Confederation

- What was the Articles of Confederation?

- Shays's Rebellion

- The Constitutional Convention

- The US Constitution

The Federalist Papers

- The Bill of Rights

- Social consequences of revolutionary ideals

- The presidency of George Washington

- Why was George Washington the first president?

- The presidency of John Adams

- Regional attitudes about slavery, 1754-1800

- Continuity and change in American society, 1754-1800

- Creating a nation

- The Federalist Papers was a collection of essays written by John Jay, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton in 1788.

- The essays urged the ratification of the United States Constitution, which had been debated and drafted at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787.

- The Federalist Papers is considered one of the most significant American contributions to the field of political philosophy and theory and is still widely considered to be the most authoritative source for determining the original intent of the framers of the US Constitution.

The Articles of Confederation and Constitutional Convention

- In Federalist No. 10 , Madison reflects on how to prevent rule by majority faction and advocates the expansion of the United States into a large, commercial republic.

- In Federalist No. 39 and Federalist 51 , Madison seeks to “lay a due foundation for that separate and distinct exercise of the different powers of government, which to a certain extent is admitted on all hands to be essential to the preservation of liberty,” emphasizing the need for checks and balances through the separation of powers into three branches of the federal government and the division of powers between the federal government and the states. 4

- In Federalist No. 84 , Hamilton advances the case against the Bill of Rights, expressing the fear that explicitly enumerated rights could too easily be construed as comprising the only rights to which American citizens were entitled.

What do you think?

- For more on Shays’s Rebellion, see Leonard L. Richards, Shays’s Rebellion: The American Revolution’s Final Battle (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002).

- Bernard Bailyn, ed. The Debate on the Constitution: Federalist and Anti-Federalist Speeches, Articles, and Letters During the Struggle over Ratification; Part One, September 1787 – February 1788 (New York: Penguin Books, 1993).

- See Federalist No. 1 .

- See Federalist No. 51 .

- For more, see Michael Meyerson, Liberty’s Blueprint: How Madison and Hamilton Wrote the Federalist Papers, Defined the Constitution, and Made Democracy Safe for the World (New York: Basic Books, 2008).

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Open 365 days a year, Mount Vernon is located just 15 miles south of Washington DC.

From the mansion to lush gardens and grounds, intriguing museum galleries, immersive programs, and the distillery and gristmill. Spend the day with us!

Discover what made Washington "first in war, first in peace and first in the hearts of his countrymen".

The Mount Vernon Ladies Association has been maintaining the Mount Vernon Estate since they acquired it from the Washington family in 1858.

Need primary and secondary sources, videos, or interactives? Explore our Education Pages!

The Washington Library is open to all researchers and scholars, by appointment only.

Federalist Papers

George Washington was sent draft versions of the first seven essays on November 18, 1787 by James Madison, who revealed to Washington that he was one of the anonymous writers. Washington agreed to secretly transmit the drafts to his in-law David Stuart in Richmond, Virginia so the essays could be more widely published and distributed. Washington explained in a letter to David Humphreys that the ratification of the Constitution would depend heavily "on literary abilities, & the recommendation of it by good pens," and his efforts to proliferate the Federalist Papers reflected this feeling. 1

Washington was skeptical of Constitutional opponents, known as Anti-Federalists, believing that they were either misguided or seeking personal gain. He believed strongly in the goals of the Constitution and saw The Federalist Papers and similar publications as crucial to the process of bolstering support for its ratification. Washington described such publications as "have thrown new lights upon the science of Government, they have given the rights of man a full and fair discussion, and have explained them in so clear and forcible a manner as cannot fail to make a lasting impression upon those who read the best publications of the subject, and particularly the pieces under the signature of Publius." 2

Although Washington made few direct contributions to the text of the new Constitution and never officially joined the Federalist Party, he profoundly supported the philosophy behind the Constitution and was an ardent supporter of its ratification.

The philosophical influence of the Enlightenment factored significantly in the essays, as the writers sought to establish a balance between centralized political power and individual liberty. Although the writers sought to build support for the Constitution, Madison, Hamilton, and Jay did not see their work as a treatise, per se, but rather as an on-going attempt to make sense of a new form of government.

The Federalist Paper s represented only one facet in an on-going debate about what the newly forming government in America should look like and how it would govern. Although it is uncertain precisely how much The Federalist Papers affected the ratification of the Constitution, they were considered by many at the time—and continue to be considered—one of the greatest works of American political philosophy.

Adam Meehan The University of Arizona

Notes: 1. "George Washington to David Humphreys, 10 October 1787," in George Washington, Writings , ed. John Rhodehamel (New York: Library of America, 1997), 657.

2. "George Washington to John Armstrong, 25 April 1788," in George Washington, Writings , ed. John Rhodehamel (New York: Library of America, 1997), 672.

Bibliography: Chernow, Ron. Washington: A Life . New York: Penguin, 2010.

Epstein, David F. The Political Theory of The Federalist . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

Furtwangler, Albert. The Authority of Publius: A Reading of the Federalist Papers . Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1984.

George Washington, Writings , ed. John Rhodehamel. New York: Library of America, 1997.

Quick Links

9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

The Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers are a series of 85 essays arguing in support of the United States Constitution . Alexander Hamilton , James Madison , and John Jay were the authors behind the pieces, and the three men wrote collectively under the name of Publius .

Seventy-seven of the essays were published as a series in The Independent Journal , The New York Packet , and The Daily Advertiser between October of 1787 and August 1788. They weren't originally known as the "Federalist Papers," but just "The Federalist." The final 8 were added in after.

At the time of publication, the authorship of the articles was a closely guarded secret. It wasn't until Hamilton's death in 1804 that a list crediting him as one of the authors became public. It claimed fully two-thirds of the essays for Hamilton. Many of these would be disputed by Madison later on, who had actually written a few of the articles attributed to Hamilton.

Once the Federal Convention sent the Constitution to the Confederation Congress in 1787, the document became the target of criticism from its opponents. Hamilton, a firm believer in the Constitution, wrote in Federalist No. 1 that the series would "endeavor to give a satisfactory answer to all the objections which shall have made their appearance, that may seem to have any claim to your attention."

Alexander Hamilton was the force behind the project, and was responsible for recruiting James Madison and John Jay to write with him as Publius. Two others were considered, Gouverneur Morris and William Duer . Morris rejected the offer, and Hamilton didn't like Duer's work. Even still, Duer managed to publish three articles in defense of the Constitution under the name Philo-Publius , or "Friend of Publius."

Hamilton chose "Publius" as the pseudonym under which the series would be written, in honor of the great Roman Publius Valerius Publicola . The original Publius is credited with being instrumental in the founding of the Roman Republic. Hamilton thought he would be again with the founding of the American Republic. He turned out to be right.

John Jay was the author of five of the Federalist Papers. He would later serve as Chief Justice of the United States. Jay became ill after only contributed 4 essays, and was only able to write one more before the end of the project, which explains the large gap in time between them.

Jay's Contributions were Federalist: No. 2 , No. 3 , No. 4 , No. 5 , and No. 64 .

James Madison , Hamilton's major collaborator, later President of the United States and "Father of the Constitution." He wrote 29 of the Federalist Papers, although Madison himself, and many others since then, asserted that he had written more. A known error in Hamilton's list is that he incorrectly ascribed No. 54 to John Jay, when in fact Jay wrote No. 64 , has provided some evidence for Madison's suggestion. Nearly all of the statistical studies show that the disputed papers were written by Madison, but as the writers themselves released no complete list, no one will ever know for sure.

Opposition to the Bill of Rights

The Federalist Papers, specifically Federalist No. 84 , are notable for their opposition to what later became the United States Bill of Rights . Hamilton didn't support the addition of a Bill of Rights because he believed that the Constitution wasn't written to limit the people. It listed the powers of the government and left all that remained to the states and the people. Of course, this sentiment wasn't universal, and the United States not only got a Constitution, but a Bill of Rights too.

No. 1: General Introduction Written by: Alexander Hamilton October 27, 1787

No.2: Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence Written by: John Jay October 31, 1787

No. 3: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence Written by: John Jay November 3, 1787

No. 4: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence Written by: John Jay November 7, 1787

No. 5: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence Written by: John Jay November 10, 1787

No. 6:Concerning Dangers from Dissensions Between the States Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 14, 1787

No. 7 The Same Subject Continued: Concerning Dangers from Dissensions Between the States Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 15, 1787

No. 8: The Consequences of Hostilities Between the States Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 20, 1787

No. 9 The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 21, 1787

No. 10 The Same Subject Continued: The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection Written by: James Madison November 22, 1787

No. 11 The Utility of the Union in Respect to Commercial Relations and a Navy Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 24, 1787

No 12: The Utility of the Union In Respect to Revenue Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 27, 1787

No. 13: Advantage of the Union in Respect to Economy in Government Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 28, 1787

No. 14: Objections to the Proposed Constitution From Extent of Territory Answered Written by: James Madison November 30, 1787

No 15: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 1, 1787

No. 16: The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 4, 1787

No. 17: The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 5, 1787

No. 18: The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: James Madison December 7, 1787

No. 19: The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: James Madison December 8, 1787

No. 20: The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: James Madison December 11, 1787

No. 21: Other Defects of the Present Confederation Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 12, 1787

No. 22: The Same Subject Continued: Other Defects of the Present Confederation Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 14, 1787

No. 23: The Necessity of a Government as Energetic as the One Proposed to the Preservation of the Union Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 18, 1787

No. 24: The Powers Necessary to the Common Defense Further Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 19, 1787

No. 25: The Same Subject Continued: The Powers Necessary to the Common Defense Further Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 21, 1787

No. 26: The Idea of Restraining the Legislative Authority in Regard to the Common Defense Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 22, 1787

No. 27: The Same Subject Continued: The Idea of Restraining the Legislative Authority in Regard to the Common Defense Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 25, 1787

No. 28: The Same Subject Continued: The Idea of Restraining the Legislative Authority in Regard to the Common Defense Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 26, 1787

No. 29: Concerning the Militia Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 9, 1788

No. 30: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 28, 1787

No. 31: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 1, 1788

No. 32: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 2, 1788

No. 33: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 2, 1788

No. 34: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 5, 1788

No. 35: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 5, 1788

No. 36: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 8, 1788

No. 37: Concerning the Difficulties of the Convention in Devising a Proper Form of Government Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 11, 1788

No. 38: The Same Subject Continued, and the Incoherence of the Objections to the New Plan Exposed Written by: James Madison January 12, 1788

No. 39: The Conformity of the Plan to Republican Principles Written by: James Madison January 18, 1788

No. 40: The Powers of the Convention to Form a Mixed Government Examined and Sustained Written by: James Madison January 18, 1788

No. 41: General View of the Powers Conferred by the Constitution Written by: James Madison January 19, 1788

No. 42: The Powers Conferred by the Constitution Further Considered Written by: James Madison January 22, 1788

No. 43: The Same Subject Continued: The Powers Conferred by the Constitution Further Considered Written by: James Madison January 23, 1788

No. 44: Restrictions on the Authority of the Several States Written by: James Madison January 25, 1788

No. 45: The Alleged Danger From the Powers of the Union to the State Governments Considered Written by: James Madison January 26, 1788

No. 46: The Influence of the State and Federal Governments Compared Written by: James Madison January 29, 1788

No. 47: The Particular Structure of the New Government and the Distribution of Power Among Its Different Parts Written by: James Madison January 30, 1788

No. 48: These Departments Should Not Be So Far Separated as to Have No Constitutional Control Over Each Other Written by: James Madison February 1, 1788

No. 49: Method of Guarding Against the Encroachments of Any One Department of Government Written by: James Madison February 2, 1788

No. 50: Periodic Appeals to the People Considered Written by: James Madison February 5, 1788

No. 51: The Structure of the Government Must Furnish the Proper Checks and Balances Between the Different Departments Written by: James Madison February 6, 1788

No. 52: The House of Representatives Written by: James Madison February 8, 1788

No. 53: The Same Subject Continued: The House of Representatives Written by: James Madison February 9, 1788

No. 54: The Apportionment of Members Among the States Written by: James Madison February 12, 1788

No. 55: The Total Number of the House of Representatives Written by: James Madison February 13, 1788

No. 56: The Same Subject Continued: The Total Number of the House of Representatives Written by: James Madison February 16, 1788

No. 57: The Alleged Tendency of the New Plan to Elevate the Few at the Expense of the Many Written by: James Madison February 19, 1788

No. 58: Objection That The Number of Members Will Not Be Augmented as the Progress of Population Demands Considered Written by: James Madison February 20, 1788

No. 59: Concerning the Power of Congress to Regulate the Election of Members Written by: Alexander Hamilton February 22, 1788

No. 60: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the Power of Congress to Regulate the Election of Members Written by: Alexander Hamilton February 23, 1788

No. 61: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the Power of Congress to Regulate the Election of Members Written by: Alexander Hamilton February 26, 1788

No. 62: The Senate Written by: James Madison February 27, 1788

No. 63: The Senate Continued Written by: James Madison March 1, 1788

No. 64: The Powers of the Senate Written by: John Jay March 5, 1788

No. 65: The Powers of the Senate Continued Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 7, 1788

No. 66: Objections to the Power of the Senate To Set as a Court for Impeachments Further Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 8, 1788

No. 67: The Executive Department Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 11, 1788

No. 68: The Mode of Electing the President Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 12, 1788

No. 69: The Real Character of the Executive Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 14, 1788

No. 70: The Executive Department Further Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 15, 1788

No. 71: The Duration in Office of the Executive Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 18, 1788

No. 72: The Same Subject Continued, and Re-Eligibility of the Executive Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 19, 1788

No. 73: The Provision For The Support of the Executive, and the Veto Power Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 21, 1788

No. 74: The Command of the Military and Naval Forces, and the Pardoning Power of the Executive Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 25, 1788

No. 75: The Treaty Making Power of the Executive Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 26, 1788

No. 76: The Appointing Power of the Executive Written by: Alexander Hamilton April 1, 1788

No. 77: The Appointing Power Continued and Other Powers of the Executive Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton April 2, 1788

No. 78: The Judiciary Department Written by: Alexander Hamilton June 14, 1788

No. 79: The Judiciary Continued Written by: Alexander Hamilton June 18, 1788

No. 80: The Powers of the Judiciary Written by: Alexander Hamilton June 21, 1788

No. 81: The Judiciary Continued, and the Distribution of the Judicial Authority Written by: Alexander Hamilton June 25, 1788

No. 82: The Judiciary Continued Written by: Alexander Hamilton July 2, 1788

No. 83: The Judiciary Continued in Relation to Trial by Jury Written by: Alexander Hamilton July 5, 1788

No. 84: Certain General and Miscellaneous Objections to the Constitution Considered and Answered Written by: Alexander Hamilton July 16, 1788

No. 85: Concluding Remarks Written by: Alexander Hamilton August 13, 1788

Images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Oak Hill Publishing Company. All rights reserved. Oak Hill Publishing Company. Box 6473, Naperville, IL 60567 For questions or comments about this site please email us at [email protected]

Introduction to the Federalist by Gordon Lloyd

Introduction to The Federalist by Gordon Lloyd

Origin of The Federalist

McLean bundled the first 36 essays togetherthey appeared in the newspapers between 27 October 1787 and 8 January 1788and published them as Volume 1 on March 22, 1788. Essays 37 through 77 of The Federalist appeared between 11 January and 2 April 1788. On 28 May, McLean took Federalist 37-77 as well as the yet to be published Federalist 78-85 and issued them all as Volume 2 of The Federalist . Between 14 June and 16 August, these eight remaining essays Federalist 78-85appeared in the Independent Journal and New York Packet .

The Status of The Federalist

One of the persistent questions concerning the status of The Federalist is this: is it a propaganda tract written to secure ratification of the Constitution and thus of no enduring relevance or is it the authoritative expositor of the meaning of the Constitution having a privileged position in constitutional interpretation? It is tempting to adopt the former position because 1) the essays originated in the rough and tumble of the ratification struggle. It is also tempting to 2) see The Federalist as incoherent; didnt [tah-onclick href=”#” onClick=”window.open(‘https://teachingamericanhistory.org/static/ratification/people/hamilton.html’,’Max’,’toolbar=no,width=500,height=400,left=10,top=10,screenX=10,screenY=10,status=no,scrollbars=yes,resize=yes’);return false”]Hamilton.[/tah-onclick] and [tah-onclick href=”#” onClick=”window.open(‘https://teachingamericanhistory.org/static/ratification/people/madison.html’,’Max’,’toolbar=no,width=500,height=400,left=10,top=10,screenX=10,screenY=10,status=no,scrollbars=yes,resize=yes’);return false”]Madison.[/tah-onclick] disagree with each other within five years of co-authoring the essays? Surely the seeds of their disagreement are sown in the very essays! 3) The essays sometimes appeared at a rate of about three per week and, according to [tah-onclick href=”#” onClick=”window.open(‘https://teachingamericanhistory.org/static/ratification/people/madison.html’,’Max’,’toolbar=no,width=500,height=400,left=10,top=10,screenX=10,screenY=10,status=no,scrollbars=yes,resize=yes’);return false”]Madison.[/tah-onclick], there were occasions when the last part of an essay was being written as the first part was being typed.

1) One should not confuse self-serving propaganda with advocating a political position in a persuasive manner. After all, rhetorical skills are a vital part of the democratic electoral process and something a free people have to handle. These are op-ed pieces of the highest quality addressing the most pressing issues of the day. 2) Moreover, because [tah-onclick href=”#” onClick=”window.open(‘https://teachingamericanhistory.org/static/ratification/people/hamilton.html’,’Max’,’toolbar=no,width=500,height=400,left=10,top=10,screenX=10,screenY=10,status=no,scrollbars=yes,resize=yes’);return false”]Hamilton.[/tah-onclick] and [tah-onclick href=”#” onClick=”window.open(‘https://teachingamericanhistory.org/static/ratification/people/madison.html’,’Max’,’toolbar=no,width=500,height=400,left=10,top=10,screenX=10,screenY=10,status=no,scrollbars=yes,resize=yes’);return false”]Madison.[/tah-onclick] parted ways doesnt mean that they werent in fundamental agreement in 1787-1788 about the need for a more energetic form of government. And just because they were written with a certain haste, doesnt mean that they were unreflective and not well written. Federalist 10 , the most famous of all the essays, is actually the final draft of an essay that originated in [tah-onclick href=”#” onClick=”window.open(‘https://teachingamericanhistory.org/static/ratification/people/madison.html’,’Max’,’toolbar=no,width=500,height=400,left=10,top=10,screenX=10,screenY=10,status=no,scrollbars=yes,resize=yes’);return false”]Madison.[/tah-onclick]s Vices in 1787, matured at the Constitutional Convention in June 1787, and was refined in a letter to Jefferson in October 1787. All of [tah-onclick href=”#” onClick=”window.open(‘https://teachingamericanhistory.org/static/ratification/people/jay.html’,’Max’,’toolbar=no,width=500,height=400,left=10,top=10,screenX=10,screenY=10,status=no,scrollbars=yes,resize=yes’);return false”]Jay.[/tah-onclick]’s essays focus on foreign policy, the heart of the Madisonian essays are Federalist 37-51 on the great difficulty of founding, and [tah-onclick href=”#” onClick=”window.open(‘https://teachingamericanhistory.org/static/ratification/people/hamilton.html’,’Max’,’toolbar=no,width=500,height=400,left=10,top=10,screenX=10,screenY=10,status=no,scrollbars=yes,resize=yes’);return false”]Hamilton.[/tah-onclick] tends to focus on the institutional features of federalism and the separation of powers.

I suggest, furthermore, that the moment these essays were available in book form, they acquired a status that went beyond the more narrowly conceived objective of trying to influence the ratification of the Constitution . The Federalist now acquired a “timeless” and higher purpose, a sort of icon status equal to the very Constitution that it was defending and interpreting. And we can see this switch in tone in Federalist 37 when [tah-onclick href=”#” onClick=”window.open(‘https://teachingamericanhistory.org/static/ratification/people/madison.html’,’Max’,’toolbar=no,width=500,height=400,left=10,top=10,screenX=10,screenY=10,status=no,scrollbars=yes,resize=yes’);return false”]Madison.[/tah-onclick] invites his readers to contemplate the great difficulty of founding. Federalist 38 , echoing Federalist 1 , points to the uniqueness of the America Founding: never before had a nation been founded by the reflection and choice of multiple founders who sat down and deliberated over creating the best form of government consistent with the genius of the American people. Thomas Jefferson referred to the Constitution as the work of “demigods,” and The Federalist “the best commentary on the principles of government, which ever was written.” There is a coherent teaching on the constitutional aspects of a new republicanism and a new federalism in The Federalist that makes the essays attractive to readers of every generation.

Authorship of The Federalist

A second question about The Federalist is how many essays did each person write? [tah-onclick href=”#” onClick=”window.open(‘https://teachingamericanhistory.org/static/ratification/people/madison.html’,’Max’,’toolbar=no,width=500,height=400,left=10,top=10,screenX=10,screenY=10,status=no,scrollbars=yes,resize=yes’);return false”]James Madison.[/tah-onclick]at the time a resident of New York since he was a Virginia delegate to the Confederation Congress that met in New York[tah-onclick href=”#” onClick=”window.open(‘https://teachingamericanhistory.org/static/ratification/people/jay.html’,’Max’,’toolbar=no,width=500,height=400,left=10,top=10,screenX=10,screenY=10,status=no,scrollbars=yes,resize=yes’);return false”]John Jay.[/tah-onclick], and [tah-onclick href=”#” onClick=”window.open(‘https://teachingamericanhistory.org/static/ratification/people/hamilton.html’,’Max’,’toolbar=no,width=500,height=400,left=10,top=10,screenX=10,screenY=10,status=no,scrollbars=yes,resize=yes’);return false”]Alexander Hamilton.[/tah-onclick]both of New Yorkwrote these essays under the pseudonym, “Publius.” So one answer to the question is that it doesnt matter since everyone signed off under the same pseudonym, “Publius.” But given the icon status of The Federalist , there has been an enduring curiosity about the authorship of the essays. Although it is virtually agreed that [tah-onclick href=”#” onClick=”window.open(‘https://teachingamericanhistory.org/static/ratification/people/jay.html’,’Max’,’toolbar=no,width=500,height=400,left=10,top=10,screenX=10,screenY=10,status=no,scrollbars=yes,resize=yes’);return false”]Jay.[/tah-onclick] wrote only five essays, there have been several disputes over the decades concerning the distribution of the essays between [tah-onclick href=”#” onClick=”window.open(‘https://teachingamericanhistory.org/static/ratification/people/hamilton.html’,’Max’,’toolbar=no,width=500,height=400,left=10,top=10,screenX=10,screenY=10,status=no,scrollbars=yes,resize=yes’);return false”]Hamilton.[/tah-onclick] and [tah-onclick href=”#” onClick=”window.open(‘https://teachingamericanhistory.org/static/ratification/people/madison.html’,’Max’,’toolbar=no,width=500,height=400,left=10,top=10,screenX=10,screenY=10,status=no,scrollbars=yes,resize=yes’);return false”]Madison.[/tah-onclick]. Suffice it to note, that [tah-onclick href=”#” onClick=”window.open(‘https://teachingamericanhistory.org/static/ratification/people/madison.html’,’Max’,’toolbar=no,width=500,height=400,left=10,top=10,screenX=10,screenY=10,status=no,scrollbars=yes,resize=yes’);return false”]Madison.[/tah-onclick]s last contribution was Federalist 63 , leaving [tah-onclick href=”#” onClick=”window.open(‘https://teachingamericanhistory.org/static/ratification/people/hamilton.html’,’Max’,’toolbar=no,width=500,height=400,left=10,top=10,screenX=10,screenY=10,status=no,scrollbars=yes,resize=yes’);return false”]Hamilton.[/tah-onclick] as the exclusive author of the nineteen Executive and Judiciary essays. [tah-onclick href=”#” onClick=”window.open(‘https://teachingamericanhistory.org/static/ratification/people/madison.html’,’Max’,’toolbar=no,width=500,height=400,left=10,top=10,screenX=10,screenY=10,status=no,scrollbars=yes,resize=yes’);return false”]Madison.[/tah-onclick] left New York in order to comply with the residence law in Virginia concerning eligibility for the Virginia ratifying convention . There is also widespread agreement that [tah-onclick href=”#” onClick=”window.open(‘https://teachingamericanhistory.org/static/ratification/people/madison.html’,’Max’,’toolbar=no,width=500,height=400,left=10,top=10,screenX=10,screenY=10,status=no,scrollbars=yes,resize=yes’);return false”]Madison.[/tah-onclick] wrote the first thirteen essays on the great difficulty of founding. There is still dispute over the authorship of Federalist 50-58, but these have persuasively been resolved in favor of [tah-onclick href=”#” onClick=”window.open(‘https://teachingamericanhistory.org/static/ratification/people/madison.html’,’Max’,’toolbar=no,width=500,height=400,left=10,top=10,screenX=10,screenY=10,status=no,scrollbars=yes,resize=yes’);return false”]Madison.[/tah-onclick].

Outline of The Federalist

A third question concerns how to “outline” the essays into its component parts. We get some natural help from the authors themselves. Federalist 1 outlines the six topics to be discussed in the essays without providing an exact table of contents. The authors didnt know in October 1787 how many essays would be devoted to each topic. Nevertheless, if one sticks with the “formal division of the subject” outlined in the first essay, it is possible to work out the actual division of essays into the six topic areas or “points” after the fact so to speak.

Martin Diamond was one of the earliest scholars to break The Federalist into its component parts. He identified Union as the subject matter of the first thirty-six Federalist essays and Republicanism as the subject matter of last forty-nine essays. There is certain neatness to this breakdown, and accuracy to the Union essays. The fist three topics outlined in Federalist 1 are 1) the utility of the union, 2) the insufficiency of the present confederation under the Articles of Confederation , and 3) the need for a government at least as energetic as the one proposed. The opening paragraph of Federalist 15 summarizes the previous fourteen essays and says: “in pursuance of the plan which I have laid down for the pursuance of the subject, the point next in order to be examined is the ‘insufficiency of the present confederation.'” So we can say with confidence that Federalist 1-14 is devoted to the utility of the union. Similarly, Federalist 23 opens with the following observation: ” the necessity of a Constitution, at least equally energetic as the one proposed is the point at the examination of the examination at which we are arrived.” Thus Federalist 15-22 covered the second point dealing with union or federalism. Finally, Federalist 37 makes it clear that coverage of the third point has come to an end and new beginning has arrived. And since McLean bundled the first thirty-six essays into Volume 1, we have confidence in declaring a conclusion to the coverage of the first three points all having to do with union and federalism.

The difficulty with the Diamond project is that it becomes messy with respect to topics 4, 5, and 6 listed in Federalist 1 : 4) the Constitution conforms to the true principles of republicanism , 5) the analogy of the Constitution to state governments, and 6) the added benefits from adopting the Constitution . Lets work our way backward. In Federalist 85 , we learn that “according to the formal division of the subject of these papers announced in my first number, there would appear still to remain for discussion two points,” namely, the fifth and sixth points. That leaves, “republicanism,” the fourth point, as the topic for Federalist 37-84, or virtually the entire Part II of The Federalist .

I propose that we substitute the word Constitutionalism for Republicanism as the subject matter for essays 37-51, reserving the appellation Republicanism for essays 52-84. This substitution is similar to the “Merits of the Constitution ” designation offered by Charles Kesler in his new introduction to the Rossiter edition; the advantage of this Constitutional approach is that it helps explain why issues other than Republicanism strictly speaking are covered in Federalist 37-46. Kesler carries the Constitutional designation through to the end; I suggest we return to Republicanism with Federalist 52 .

The Argument of The Federalist

Part I Federalist 1: The Challenge and the Outline

Part II Federalist 2Federalist 14: “The Utility of the Union”

Part III Federalist 15-22: The “Insufficiency” of the Articles of Confederation

Part IV Federalist 23-36: The minimum “energetic” government requirement

Part V Federalist 37-51: “The Great Difficulty of Founding”

A. Federalist 37-40: The Difficulty with Demarcations and Definitions B. Federalist 41-46: The Difficulty of Federalism C. Federalist 47-51: The Difficulty of Republicanism

Part VI Federalist 52-84: “The True Principles of Republican Government”

A. Federalist 52-61: The House of Representatives B. Federalist 62-66: The Senate C. Federalist 67-77: The Presidency D. Federalist 78-82: The Judiciary E . Federalist 83-84: Five Miscellaneous Republican Issues

Part VII Federalist 85: Analogy to State Governments and Added Security to Republicanism

The (Vital) Federalist

A final question involves choosing which essays are essential since there are so many other vital texts to read and digest. J.D. Pole managed to cut the must reading list down to 37 essays, Michael Kammen was more discriminating; he produced a list of 21 essential readings. Clinton Rossiters “cream of the 85” list also contained 21 entries and they were exactly the same as Kammens essays. Ralph Ketcham tried his hand at a “long list,” and a “short list.” The former contained 30 essays and the latter he paired down to 14 essays.

We have included a summary of each of The Federalist essays; however “the six vital essays” Federalist 10 , 51 , 63 , 71 , 78 , and 84 receive a paragraph-by-paragraph treatment.)

Receive resources and noteworthy updates.

The Federalist

The Federalist is a collection of short essays written by Alexander Hamilton , James Madison , and John Jay .

Hamilton became Secretary of the Treasury and remained in that position for much of Washington’s Presidency. Madison went on to be a member of the House of Representatives, Secretary of State under Thomas Jefferson, and the fourth President of the United States. John Jay served for a time as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and then as Governor of the state of New York.

The Federalist was written in order to convince New Yorkers and Americans generally that they should ratify, or give formal consent to, the Constitution, making it officially valid. Many feared that the proposed Constitution created too strong of a central government. Defenders of the Constitution began writing in support of the Constitution, arguing that the Constitution created a stronger central government than existed under the Article of Confederation -- and for good reason -- but also that the new Constitution’s government was still carefully limited by federalism and the separation of powers. In other words, these writers claimed, the Constitution actually created the kind of government sought by its critics. The Federalist has become the most famous of these pro-Constitution writings.

The essays were originally published in the New York press between October 27, 1787 and August 13, 1788, but from the beginning, Hamilton planned to have them printed in book form, which he did in March and May of 1788. As a result, some of the essays appeared in book form even before they appeared in the press. To this day, they remain a touchstone for understanding the Constitution.

Who: Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay

Why: To convince New Yorkers and Americans generally that they should ratify, or give formal consent to the Constitution, making it officially valid.

When: March and May of 1788.

Publishing Information: The Federalist : A Collection of Essays, written in Favour of the New Constitution, as Agreed Upon by the Federal Convention, September 17, 1787. First Edition. In Two Volumes. New York: J. and A. M’Lean, 1788. With Michael Zinman bookplate.

Alexander Hamilton

James Madison

Learning Activities

As The Federalist explains, the Constitution tries to combine both energy and safety. It includes institutions like the President meant to provide that energy but also checks and balances to prevent the government from acting oppressively. Do you think they succeeded? Why or why not?

Explore the Constitution

- The Constitution

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, constitution 101 resources, 3.5 info brief: the federalist papers.

This activity is part of Module 3: Road to the Convention from the Constitution 101 Curriculum.

The Federalist Papers were a series of 85 essays printed in newspapers to persuade critics of the Constitution and those on the fence to support ratification.

Alexander Hamilton wrote 51 of these essays, James Madison 29, and John Jay five.

All three authors wrote under the same famous pen name—“Publius.”

Broadly speaking, Madison focused on the big theoretical and structural questions of government and politics.

Hamilton focused on specific issues like the structure of (and framers’ vision for) the presidency and national courts.

The Federalist Papers—and their brilliant authors—were capable of both high-minded theory and persuasive political arguments.

Today, scholars and ordinary Americans alike recognize The Federalist Papers as some of the finest works of political theory. But it’s also important to understand them in context—as political documents written during the fight over the ratification of the U.S. Constitution.

More from the National Constitution Center

Constitution 101

Explore our new 15-unit core curriculum with educational videos, primary texts, and more.

Search and browse videos, podcasts, and blog posts on constitutional topics.

Founders’ Library

Discover primary texts and historical documents that span American history and have shaped the American constitutional tradition.

Modal title

Modal body text goes here.

Founders Online --> [ Back to normal view ]

The federalist no. 56, [16 february 1788], the federalist no. 56 1 by james madison or alexander hamilton.

[New York, February 16, 1788]

To the People of the State of New-York.

THE second charge against the House of Representatives is, that it will be too small to possess a due knowledge of the interests of its constituents.

As this objection evidently proceeds from a comparison of the proposed number of representatives, with the great extent of the United States, the number of their inhabitants, and the diversity of their interests, without taking into view at the same time the circumstances which will distinguish the Congress from other legislative bodies, the best answer that can be given to it, will be a brief explanation of these peculiarities.

It is a sound and important principle that the representative ought to be acquainted with the interests and circumstances of his constituents. But this principle can extend no farther than to those circumstances and interests, to which the authority and care of the representative relate. An ignorance of a variety of minute and particular objects, which do not lie within the compass of legislation, is consistent with every attribute necessary to a due performance of the legislative trust. In determining the extent of information required in the exercise of a particular authority, recourse then must be had to the objects within the purview of that authority.

What are to be the objects of federal legislation? Those which are of most importance, and which seem most to require local knowledge, are commerce, taxation, and the militia.

A proper regulation of commerce requires much information, as has been elsewhere remarked; 2 but as far as this information relates to the laws and local situation of each individual state, a very few representatives would be very 3 sufficient vehicles of it to the federal councils.

Taxation will consist, in great measure, of duties which will be involved in the regulation of commerce. So far the preceding remark is applicable to this object. As far as it may consist of internal collections, a more diffusive knowledge of the circumstances of the state may be necessary. But will not this also be possessed in sufficient degree by a very few intelligent men diffusively elected within the state. Divide the largest state into ten or twelve districts, and it will be found that there will be no peculiar local interest in either, which will not be within the knowledge of the representative of the district. Besides this source of information, the laws of the state framed by representatives from every part of it, will be almost of themselves a sufficient guide. In every state there have been made, and must continue to be made, regulations on this subject, which will in many cases leave little more to be done by the federal legislature, than to review the different laws, and reduce them into one general act. A skilful individual in his closet, with all the local codes before him, might compile a law on some subjects of taxation for the whole union, without any aid from oral information; and it may be expected, that whenever internal taxes may be necessary, and particularly in cases requiring uniformity throughout the states, the more simple objects will be preferred. To be fully sensible of the facility which will be given to this branch of federal legislation, by the assistance of the state codes, we need only suppose for a moment, that this or any other state were divided into a number of parts, each having and exercising within itself a power of local legislation. Is it not evident that a degree of local information and preparatory labour would be found in the several volumes of their proceedings, which would very much shorten the labours of the general legislature, and render a much smaller number of members sufficient for it? The federal councils will derive great advantage from another circumstance. The representatives of each state will not only bring with them a considerable knowledge of its laws, and a local knowledge of their respective districts; but will probably in all cases have been members, and may even at the very time be members of the state legislature, where all the local information and interests of the state are assembled, and from whence they may easily be conveyed by a very few hands into the legislature of the United States.

The observations made on the subject of taxation apply with greater force to the case of the militia. For however different the rules of discipline may be in different states; They are the same throughout each particular state; and depend on circumstances which can differ but little in different parts of the same state. 4

The attentive reader will discern that the reasoning here used to prove the sufficiency of a moderate number of representatives, does not in any respect contradict what was urged on another occasion with regard to the extensive information which the representatives ought to possess, and the time that might be necessary for acquiring it. 5 This information, so far as it may relate to local objects, is rendered necessary and difficult, not by a difference of laws and local circumstances within a single state; but of those among different states. Taking each state by itself, its laws are the same, and its interests but little diversified. A few men therefore will possess all the knowledge requisite for a proper representation of them. Were the interests and affairs of each individual state, perfectly simple and uniform, a knowledge of them in one part would involve a knowledge of them in every other, and the whole state might be competently represented, by a single member taken from any part of it. On a comparison of the different states together, we find a great dissimilarity in their laws, and in many other circumstances connected with the objects of federal legislation, with all of which the federal representatives ought to have some acquaintance. Whilst a few representatives therefore from each state may bring with them a due knowledge of their own state, every representative will have much information to acquire concerning all the other states. The changes of time, as was formerly remarked, 6 on the comparative situation of the different states, will have an assimilating effect. 7 The effect of time on the internal affairs of the states taken singly, will be just the contrary. At present some of the states are little more than a society of husbandmen. Few of them have made much progress in those branches of industry, which give a variety and complexity to the affairs of a nation. These however will in all of them be the fruits of a more advanced population; and will require on the part of each state a fuller representation. The foresight of the Convention has accordingly taken care that the progress of population may be accompanied with a proper increase of the representative branch of the government.

The experience of Great Britain which presents to mankind so many political lessons, both of the monitory and exemplary kind, and which has been frequently consulted in the course of these enquiries, corroborates the result of the reflections which we have just made. The number of inhabitants in the two kingdoms of England and Scotland, cannot be stated at less than eight millions. The representatives of these eight millions in the House of Commons, amount to five hundred fifty eight. Of this number one ninth are elected by three hundred and sixty four persons, and one half by five thousand seven hundred and twenty three persons. * It cannot be supposed that the half thus elected, and who do not even reside among the people at large, can add any thing either to the security of the people against the government; or to the knowledge of their circumstances and interests, in the legislative councils. On the contrary it is notorious that they are more frequently the representatives and instruments of the executive magistrate, than the guardians and advocates of the popular rights. They might therefore with great propriety be considered as something more than a mere deduction from the real representatives of the nation. We will however consider them, in this light alone, and will not extend the deduction, to a considerable number of others, who do not reside among their constituents, are very faintly connected with them, and have very little particular knowledge of their affairs. With all these concessions two hundred and seventy nine persons only will be the depository of the safety, interest and happiness of eight millions; that is to say: There will be one representative only to maintain the rights and explain the situation of twenty eight thousand six hundred and seventy constituents, in an assembly exposed to the whole force of executive influence, and extending its authority to every object of legislation within a nation whose affairs are in the highest degree diversified and complicated. Yet it is very certain not only that a valuable portion of freedom has been preserved under all these circumstances, but that the defects in the British code are chargeable in a very small proportion, on the ignorance of the legislature concerning the circumstances of the people. Allowing to this case the weight which is due to it: And comparing it with that of the House of Representatives as above explained, it seems to give the fullest assurance that a representative for every thirty thousand inhabitants will render the latter both a safe and competent guardian of the interests which will be confided to it.

The [New York] Independent Journal: or, the General Advertiser , February 16, 1788. This essay appeared in New-York Packet on February 19. In the McLean description begins The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution, As Agreed upon by the Federal Convention, September 17, 1787. In Two Volumes (New York: Printed and Sold by J. and A. McLean, 1788). description ends edition this essay is numbered 56, in the newspapers it is numbered 55.

1 . For background to this document, see “The Federalist. Introductory Note,” October 27, 1787–May 28, 1788 .

Essay 56 is one of those disputed essays the authorship of which cannot be assigned on the basis of internal evidence to either Madison or H. Edward G. Bourne (“The Authorship of the Federalist,” The American Historical Review , II [April, 1897], 453) gives the following example to demonstrate Madison’s authorship:

Bourne argues that because the Constitution assigned Virginia ten representatives and New York six, Madison would be more likely than H to use the figure ten as an example. He further states that some months later in the New York Ratifying Convention H in illustrating the adequacy of the representation provided by the Constitution spoke of a state as being divided into six districts. The argument is not convincing because the author of essay 56 spoke of “ten or twelve districts” which might mean, using the same kind of logic employed by Bourne, that H, unlike Madison, did not remember the exact number of districts into which Virginia was divided; also, in the same paragraph in essay 56 it is stated, “suppose … that this or any other state were divided into a number of parts …,” a statement which suggests that the author arbitrarily had selected his figures. Bourne also adduces as evidence of Madison’s authorship the fact that in the closing paragraph of this essay the word “monitory … almost a favorite word with Madison,” is used. For an example of H’s use of the same word, see note 36 to “The Federalist. Introductory Note,” October 27, 1787–May 28, 1788 .

J. C. Hamilton ( The Federalist , I, cxxviii), also using internal evidence, gives the following example to prove that essay 56 was written by H:

One might give as further evidence of H’s authorship the fact that in revising the essays for publication by McLean he deleted paragraph seven and substituted another paragraph for it. Although in the McLean description begins The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution, As Agreed upon by the Federal Convention, September 17, 1787. In Two Volumes (New York: Printed and Sold by J. and A. McLean, 1788). description ends edition H occasionally altered or changed a word in Madison’s essays, in no other instance did he make a major change. Had he not believed that he was the author of the essay, one might argue, it is unlikely he would have made the substitution.

As suggested by the research of Bourne and J. C. Hamilton, however, the evidence is contradictory. One could, for example, indicate passages that are remarkably similar to statements made by H in essay 36; one could, on the other hand, point out statements which are almost the same as statements made by Madison in essay 53. An example of these similarities follows:

Examples might be multiplied, but they would all lead to the same question: Did Madison borrow from essay 36, or did H borrow from essay 53? The question, it seems, is not susceptible of an answer. Both Bourne and Douglass Adair (“The Authorship of the Disputed Federalist Papers,” Part II, The William and Mary Quarterly , I [July, 1944], 260) give as evidence for Madison’s authorship a reference to James Burgh’s Political Disquisitions . They argue that because the Virginian took notes from Burgh in his “Additional Memorandum for the Convention of Virginia” ( Madison, Letters description begins James Madison, Letters and Other Writings of James Madison (Philadelphia, 1867). description ends , I, 393, note), and because no reference to Burgh can be found in the writings of H, Madison must have written essay 56. The argument is based on the erroneous assumption that because H did not again refer to Burgh in other writings he could not have read him. In the first place, there is no positive evidence that H had not read Burgh and, in the second place, H referred in The Federalist to many authors who are not mentioned in his other writings. For example, in essay 70 , definitely written by H, there is a reference to “the celebrated Junius,” the famous English letter writer of the eighteenth century. So far as can be determined, H made no other reference to Junius.

Since one can demonstrate the authorship of either man by carefully looking for parallels in his other writings, it is obvious that internal evidence cannot decide the problem of authorship. For the reasons why Madison’s claim to the authorship of this essay outweighs (but does not necessarily obviate) that of H, see “The Federalist. Introductory Note,” October 27, 1787–May 28, 1788 .

2 . See essay 53 .

3 . “very” omitted in Hopkins description begins The Federalist On The New Constitution. By Publius. Written in 1788. To Which is Added, Pacificus, on The Proclamation of Neutrality. Written in 1793. Likewise, The Federal Constitution, With All the Amendments. Revised and Corrected. In Two Volumes (New York: Printed and Sold by George F. Hopkins, at Washington’s Head, 1802). description ends .

4 . The following was substituted in McLean description begins The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution, As Agreed upon by the Federal Convention, September 17, 1787. In Two Volumes (New York: Printed and Sold by J. and A. McLean, 1788). description ends and Hopkins for this paragraph: