- HISTORY & CULTURE

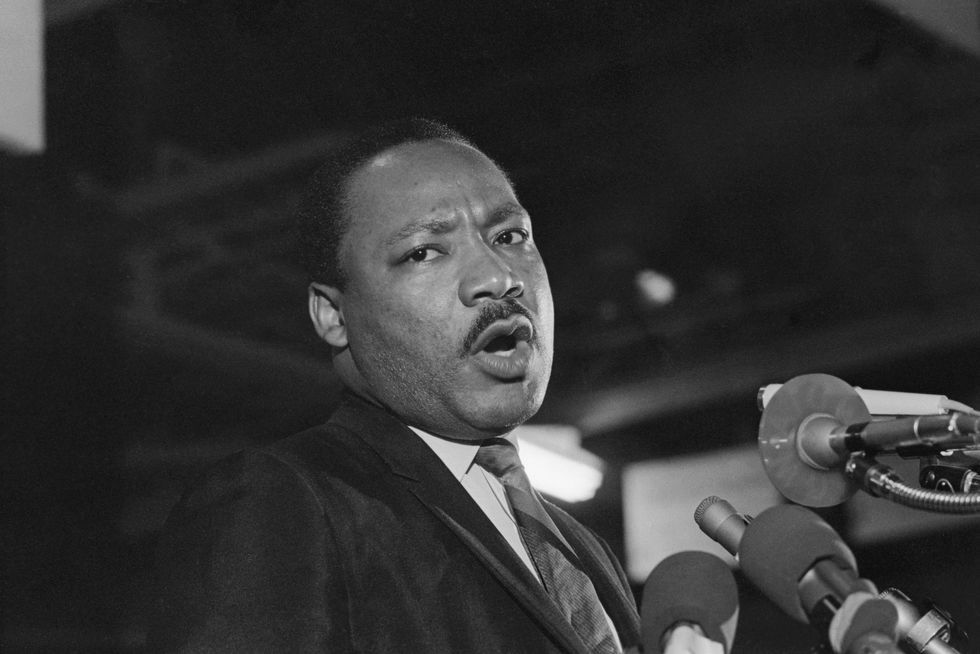

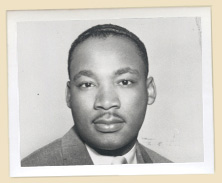

Who was Martin Luther King, Jr.?

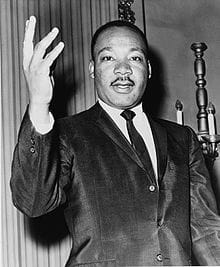

A civil rights legend, Dr. King fought for justice through peaceful protest—and delivered some of the 20th century's most iconic speeches.

The Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., is a civil rights legend. In the mid-1950s, King led the movement to end segregation and counter prejudice in the United States through the means of peaceful protest. His speeches—some of the most iconic of the 20th century—had a profound effect on the national consciousness. Through his leadership, the civil rights movement opened doors to education and employment that had long been closed to Black America.

In 1983, President Ronald Reagan signed a bill creating a federal holiday to honor King for his commitment to equal rights and justice for all. Observed for the first time on January 20, 1986, it’s called Martin Luther King Jr. Day. In January 2000, Martin Luther King Jr. Day was officially observed in all 50 U.S. states . Here’s what you need to know about King’s extraordinary life.

Though King's name is known worldwide, many may not realize that he was born Michael King, Jr. in Atlanta, Georgia on January 15, 1929. His father , Michael King, was a pastor at the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. During a trip to Germany, King, Sr. was so impressed by the history of Protestant Reformation leader Martin Luther that he changed not only his own name, but also five-year-old Michael’s.

( Read about Martin Luther King, Jr. with your kids .)

His brilliance was noted early, as he was accepted into Morehouse College , a historically Black school in Atlanta, at age 15. By the summer before his last year of college, King knew he was destined to continue the family profession of pastoral work and decided to enter the ministry. He received his Bachelor’s degree from Morehouse at age 19, and then enrolled in Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, graduating with a Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1951. He earned a doctorate in systematic theology from Boston University in 1955.

King married Coretta Scott on June 18, 1953, on the lawn of her parents' house in her hometown of Heiberger, Alabama. They became the parents of four children : Yolanda King (1955–2007), Martin Luther King III (b. 1957), Dexter Scott King (b. 1961), and Bernice King (b. 1963).

Becoming a civil rights leader

In 1954, when he was 25 years old, Dr. King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. In March 1955, Claudette Colvin—a 15-year-old Black schoolgirl in Montgomery—refused to give up her bus seat to a white man, which was a violation of Jim Crow laws, local laws in the southern United States that enforced racial segregation.

FREE BONUS ISSUE

( Jim Crow laws created 'slavery by another name. ')

King was on the committee from the Birmingham African-American community that looked into the case. The local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) briefly considered using Colvin's case to challenge the segregation laws, but decided that because she was so young—and had become pregnant—her case would attract too much negative attention.

Nine months later on December 1, 1955, a similar incident occurred when a seamstress named Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a city bus. The two incidents led to the Montgomery bus boycott , which was urged and planned by the President of the Alabama Chapter of the NAACP, E.D. Nixon, and led by King. The boycott lasted for 385 days.

King’s prominent and outspoken role in the boycott led to numerous threats against his life, and his house was firebombed. He was arrested during the campaign, which concluded with a United States District Court ruling in Browder v. Gayle ( in which Colvin was a plaintiff ) that ended racial segregation on all Montgomery public buses. King's role in the bus boycott transformed him into a national figure and the best-known spokesman of the civil rights movement.

Fighting for change through nonviolent protest

From the early days of the Montgomery boycott, King had often referred to India’s Mahatma Gandhi as “the guiding light of our technique of nonviolent social change.”

You May Also Like

How Martin Luther King, Jr.’s multifaceted view on human rights still inspires today

The birth of the Holy Roman Empire—and the unlikely king who ruled it

How Martin Luther Started a Religious Revolution

In 1957, King, Ralph Abernathy, Fred Shuttlesworth, Joseph Lowery, and other civil rights activists founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to harness the organizing power of Black churches to conduct nonviolent protests to ultimately achieve civil rights reform. The group was part of what was called “The Big Five” of civil rights organizations, which included the NAACP, the National Urban League, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and the Congress on Racial Equality.

Through his connections with the Big Five civil rights groups, overwhelming support from Black America and with the support of prominent individual well-wishers, King’s skill and effectiveness grew exponentially. He organized and led marches for Blacks' right to vote, desegregation, labor rights, and other basic civil rights.

( How the U.S. Voting Rights Act was won—and why it's under fire today .)

On August 28, 1963, The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom became the pinnacle of King’s national and international influence. Before a crowd of 250,000 people, he delivered the legendary “I Have A Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. That speech, along with many others that King delivered, has had a lasting influence on world rhetoric .

In 1964, King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his civil rights and social justice activism. Most of the rights King organized protests around were successfully enacted into law with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the 1965 Voting Rights Act .

Economic justice and the Vietnam War

King’s opposition to the Vietnam War became a prominent part of his public persona. On April 4, 1967—exactly one year before his death—he gave a speech called “Beyond Vietnam” in New York City, in which he proposed a stop to the bombing of Vietnam. King also suggested that the United States declare a truce with the aim of achieving peace talks, and that the U.S. set a date for withdrawal.

( King's advocacy for human rights around the world still inspires today .)

Ultimately, King was driven to focus on social and economic justice in the United States. He had traveled to Memphis, Tennessee in early April 1968 to help organize a sanitation workers’ strike, and on the night of April 3, he delivered the legendary “I've Been to the Mountaintop" speech , in which he compared the strike to the long struggle for human freedom and the battle for economic justice, using the New Testament's Parable of the Good Samaritan to stress the need for people to get involved.

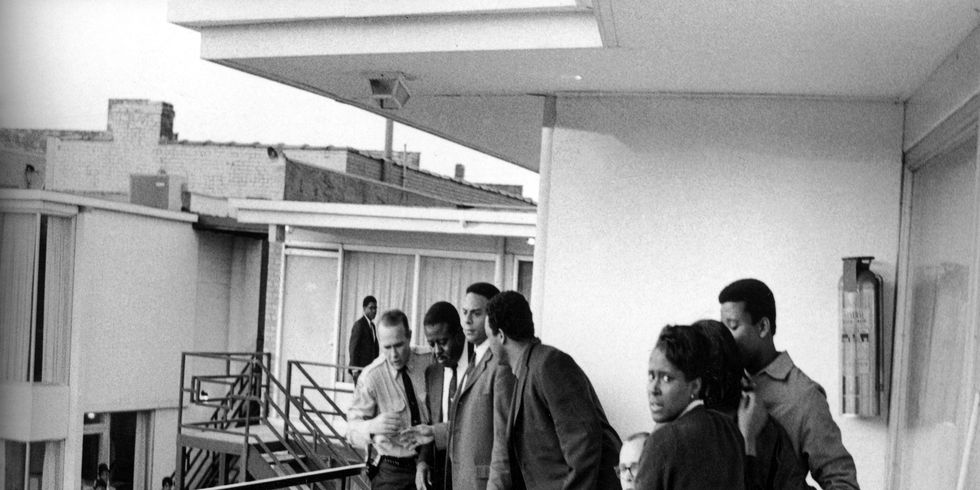

Assassination

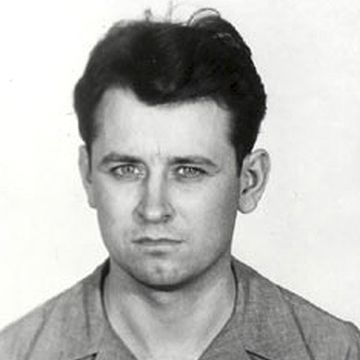

But King would not live to realize that vision. The next day, April 4, 1968, King was gunned down on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis by James Earl Ray , a small-time criminal who had escaped the year before from a maximum-security prison. Ray was charged and convicted of the murder and sentenced to 99 years in prison on March 10, 1969. But Ray changed his mind after three days in jail, claiming he was not guilty and had been framed. He spent the rest of his life fighting unsuccessfully for a trial, despite the ultimate support of some members of the King family and the Reverend Jesse Jackson.

The turmoil that flowed from King’s assassination led many Black Americans to wonder if that dream he had spoken of so eloquently had died with him. But, today, young people around the world still learn about King's life and legacy—and his vision of equality and justice for all continue to resonate.

Related Topics

- CIVIL RIGHTS

Herod I: The controversial king who transformed the Holy Land

What was the Stonewall uprising?

Harriet Tubman, the spy: uncovering her secret Civil War missions

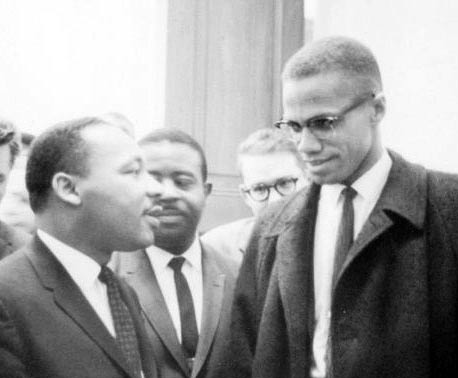

MLK and Malcolm X only met once. Here’s the story behind an iconic image.

Meet the 5 iconic women being honored on new quarters in 2024

- Environment

- Perpetual Planet

- History & Culture

History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

The New Definitive Biography of Martin Luther King Jr.

“King: A Life,” by Jonathan Eig, is the first comprehensive account of the civil rights icon in decades.

Credit... PS Spencer

Supported by

- Share full article

By Dwight Garner

- Published May 8, 2023 Updated May 28, 2023

KING: A Life , by Jonathan Eig

Listen to This Article

Growing up, he was called Little Mike, after his father, the Baptist minister Michael King. Later he sometimes went by M.L. Only in college did he drop his first name and began to introduce himself as Martin Luther King Jr. This was after his father visited Germany and, inspired by accounts of the reform-minded 16th-century friar Martin Luther, adopted his name.

King Jr. was born in 1929. Were he alive he would be 94, the same age as Noam Chomsky. The prosperous King family lived on Auburn Avenue in Atlanta. One writer, quoted by Jonathan Eig in his supple, penetrating, heartstring-pulling and compulsively readable new biography, “King: A Life,” called it “the richest Negro street in the world.”

Eig’s is the first comprehensive biography of King in three decades. It draws on a landslide of recently released White House telephone transcripts, F.B.I. documents, letters, oral histories and other material, and it supplants David J. Garrow’s 1986 biography “Bearing the Cross” as the definitive life of King, as Garrow himself deposed recently in The Spectator . It also updates the material in Taylor Branch’s magisterial trilogy about America during the King years.

King and his two siblings had the trappings of middle-class life in Atlanta: bicycles, a dog, allowances. But they were sickly aware of the racism that made white people shun them, that kept them out of most of the city’s parks and swimming pools, among other degradations.

Their father expected a lot from his children. He had a temper. He was a stern disciplinarian who spanked with a belt. Their mother was a calmer, sweeter, more stable presence. King would inherit qualities from both.

One of the stranger moments in King’s childhood, and thus in American history, occurred on Dec. 15, 1939. That was the night Clark Gable, Carole Lombard and other Hollywood stars converged on Atlanta for the premiere of “Gone With the Wind,” the highly anticipated film version of Margaret Mitchell’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1936 novel.

“Gone With the Wind” was already controversial in the Black community for its placid and romantic depiction of slavery. To the dismay of some of his peers, King’s father allowed his church’s choir to perform at the premiere. It was only a movie, he thought, and not an entirely inaccurate one. Choir members wore slave costumes, their heads wrapped with cloth. “Martin Luther King Jr., dressed as a young slave, sat in the choir’s first row, singing along,” Eig writes.

King was a sensitive child. When things upset him, he twice tried to commit suicide, if halfheartedly, by leaping out of a second-story window of his house. (Both times, he wasn’t seriously hurt.) He was bright and skipped several grades in school. He thought he might be a doctor or a lawyer; the high emotion in church embarrassed him.

When he arrived in 1944 at nearby Morehouse College, one of the most distinguished all-Black, all-male colleges in America, he was 15 and short for his age. He picked up the nickname Runt. He majored in sociology. He read Henry David Thoreau’s essay “Civil Disobedience” and it was a vital early influence. He began to think about life as a minister, and he practiced his sermons in front of a mirror.

He was small, but he was a natty dresser and possessed a trim mustache and a dazzling smile. Women were already throwing themselves at him, and they would never stop doing so.

He attended Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania, where he fell in love with and nearly married a white woman, but that would have ended any hope of becoming a minister in the South. Eig, who has also written artful biographies of Muhammad Ali and Lou Gehrig, describes how several young women attended King’s graduation from Crozer and how — as if in a scene from a Feydeau farce — each expected to be introduced to his parents as his fiancée.

King then pursued a doctorate at Boston University. (He nearly went to the University of Edinburgh in Scotland instead, a notion that is mind-bending to contemplate.) He was said to be the most eligible young Black man in the city.

In Boston he fell in love with Coretta Scott, he said, over the course of a single telephone call. She had attended Antioch College in Ohio and was studying voice at the New England Conservatory; she hoped to become a concert singer. Their love story is beautifully related. They were married in Alabama, at the Scott family’s home near Marion. They spent the first night of their marriage in the guest bedroom of a funeral parlor, because no local hotel would accommodate them.

The Kings moved to Montgomery, Ala., in 1954, when he took over as pastor at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. A year later, a seamstress named Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to white passengers on a Montgomery bus. Thus began the Montgomery bus boycott, an action that established the city as a crucible of the civil rights movement. The young pastor was about to rise to a great occasion, and to step into history.

“As I watched them,” he wrote about the men and women who participated in the long and difficult boycott, “I knew that there is nothing more majestic than the determined courage of individuals willing to suffer and sacrifice for their freedom and dignity.”

By this point in “King: A Life,” Eig has established his voice. It’s a clean, clear, journalistic voice, one that employs facts the way Saul Bellow said they should be employed, each a wire that sends a current. He does not dispense two-dollar words; he keeps digressions tidy and to a minimum; he jettisons weight, on occasion, for speed. He appears to be so in control of his material that it is difficult to second-guess him.

By the time we’ve reached Montgomery, King’s reputation has been flyspecked. Eig flies low over his penchant for plagiarism, in academic papers and elsewhere. (King was a synthesizer of ideas, not an original scholar.) His womanizing only got worse over the years. This is a very human, and quite humane, portrait.

Many readers will be familiar with what follows: the long fight in Montgomery, in which the world came to realize that this wasn’t merely about bus seats, and it wasn’t merely Montgomery’s problem. Later, the whole world was watching as Bull Connor, Birmingham’s commissioner of public safety, sicced police dogs on peaceful protesters. In prison, King would compose what is now known as “Letter From Birmingham Jail” on napkins, toilet paper and in the margins of newspapers. Later came the 1963 March on Washington and King’s partly improvised “I Have a Dream” speech.

During these years, King was imprisoned on 29 separate occasions. He never got used to it. He had shotguns fired into his family’s house. Bombs were found on his porch. Crosses were burned on his lawn. He was punched in the face more than once. In 1958, in Harlem, he was stabbed in the chest with a seven-inch letter opener. He was told that had he even sneezed before doctors could remove it, he might have died.

Eig is adept at weaving in other characters, and other voices. He makes it plain that King was not acting in a vacuum, and he traces the work of organizations like the N.A.A.C.P., CORE and SNCC, and of men like Thurgood Marshall, John Lewis, Julian Bond and Ralph Abernathy. He shows how King was too progressive for some, and vastly too conservative for others, Malcolm X central among them.

As this book moves into its final third, you sense the author echolocating between two other major biographies, Robert Caro’s multivolume life of Lyndon Johnson and Beverly Gage’s powerful recent biography of J. Edgar Hoover, the longtime F.B.I. director.

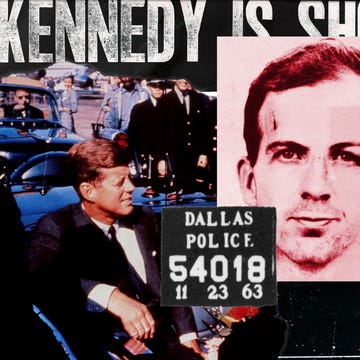

King’s relationships with John F. Kennedy and Robert Kennedy were complicated; his relationship with Johnson was even more so. King and Johnson were driven apart when King began to speak out against the Vietnam War, which Johnson considered a betrayal.

The details about Hoover’s relentless pursuit of King, via wiretaps and other methods, are repulsive. American law enforcement was more interested in tarring King with whatever they could dig up than in protecting him. Hoover tried to paint him as a communist; he wasn’t one.

King was under constant surveillance. Hoover’s F.B.I. agents bugged his hotel rooms and reported that he was having sex with many women, in many cities; they tried to drive him to suicide by threatening to release the tapes. King, in one bureau report, is said to have “participated in a sex orgy.” There is also an allegation, about which Eig is dubious, that King looked on during a rape. Complete F.B.I. recordings and transcripts are scheduled to be released in 2027.

Eig catches King in private moments. He had health issues; the stresses of his life aged him prematurely. He rarely got enough sleep, but he didn’t seem to need it. Writing about his demeanor in general, the writer Louis Lomax called King the “foremost interpreter of the Negro’s tiredness.”

King loved good Southern food and ate like a country boy. When the meal was especially delicious, he liked to eat with his hands. He argued, laughing, that utensils only got in the way.

Once, when his daughter skinned her knee by a swimming pool, he took a piece of fried chicken and jokingly pretended to apply it to the wound. “Let’s put some fried chicken on that,” he said. “Yes, a little piece of chicken, that’s always the best thing for a cut.”

Eig has read everything, from W.E.B. Du Bois through Norman Mailer and Murray Kempton and Caro and Gage. He argues that we have sometimes mistaken King’s nonviolence for passivity. He doesn’t put King on the couch, but he considers the lifelong guilt King felt about his privileged upbringing, and how he was driven by competitiveness with his father, who had moral failures of his own.

He lingers on the cadences of King’s speeches, explaining how he learned to work his audience, to stretch and rouse them at the same time. He had the best material on his side, and he knew it. Eig puts it this way: “Here was a man building a reform movement on the most American of pillars: the Bible, the Declaration of Independence, the American dream.”

Eig’s book is worthy of its subject.

Audio produced by Kate Winslett .

KING: A Life | By Jonathan Eig | Illustrated | 669 pp. | Farrar, Straus & Giroux | $35

Dwight Garner has been a book critic for The Times since 2008. His new book, “The Upstairs Delicatessen: On Eating, Reading, Reading About Eating, and Eating While Reading,” is out this fall. More about Dwight Garner

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

Salman Rushdie’s new memoir, “Knife,” addresses the attack that maimed him in 2022, and pays tribute to his wife who saw him through .

Recent books by Allen Bratton, Daniel Lefferts and Garrard Conley depict gay Christian characters not usually seen in queer literature.

What can fiction tell us about the apocalypse? The writer Ayana Mathis finds unexpected hope in novels of crisis by Ling Ma, Jenny Offill and Jesmyn Ward .

At 28, the poet Tayi Tibble has been hailed as the funny, fresh and immensely skilled voice of a generation in Māori writing .

Amid a surge in book bans, the most challenged books in the United States in 2023 continued to focus on the experiences of L.G.B.T.Q. people or explore themes of race.

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

Advertisement

About Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Dr. king jr..

Drawing inspiration from both his Christian faith and the peaceful teachings of Mahatma Gandhi, Dr. King led a nonviolent movement in the late 1950s and ‘ 60s to achieve legal equality for African-Americans in the United States. While others were advocating for freedom by “any means necessary,” including violence, Martin Luther King, Jr. used the power of words and acts of nonviolent resistance, such as protests, grassroots organizing, and civil disobedience to achieve seemingly-impossible goals. He went on to lead similar campaigns against poverty and international conflict, always maintaining fidelity to his principles that men and women everywhere, regardless of color or creed, are equal members of the human family.

Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, Nobel Peace Prize lecture and “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” are among the most revered orations and writings in the English language. His accomplishments are now taught to American children of all races, and his teachings are studied by scholars and students worldwide. He is the only non-president to have a national holiday dedicated in his honor and is the only non-president memorialized on the Great Mall in the nation’s capital. He is memorialized in hundreds of statues, parks, streets, squares, churches and other public facilities around the world as a leader whose teachings are increasingly-relevant to the progress of humankind.

Some of Dr. King’s Most Important Achievements

In 1957 , Dr. King was elected president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), an organization designed to provide new leadership for the now burgeoning civil rights movement. He would serve as head of the SCLC until his assassination in 1968, a period during which he would emerge as the most important social leader of the modern American civil rights movement.

In 1963 , he led a coalition of numerous civil rights groups in a nonviolent campaign aimed at Birmingham, Alabama, which at the time was described as the “most segregated city in America.” The subsequent brutality of the city’s police, illustrated most vividly by television images of young blacks being assaulted by dogs and water hoses, led to a national outrage resulting in a push for unprecedented civil rights legislation. It was during this campaign that Dr. King drafted the “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” the manifesto of Dr. King’s philosophy and tactics, which is today required-reading in universities worldwide.

Later in 1963 , Dr. King was one of the driving forces behind the March for Jobs and Freedom, more commonly known as the “March on Washington,” which drew over a quarter-million people to the national mall. It was at this march that Dr. King delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, which cemented his status as a social change leader and helped inspire the nation to act on civil rights. Dr. King was later named Time magazine’s “Man of the Year.”

Also in 1964 , partly due to the March on Washington, Congress passed the landmark Civil Rights Act, essentially eliminating legalized racial segregation in the United States. The legislation made it illegal to discriminate against blacks or other minorities in hiring, public accommodations, education or transportation, areas which at the time were still very segregated in many places.

The next year, 1965 , Congress went on to pass the Voting Rights Act, which was an equally-important set of laws that eliminated the remaining barriers to voting for African-Americans, who in some locales had been almost completely disenfranchised. This legislation resulted directly from the Selma to Montgomery, AL March for Voting Rights lead by Dr. King.

Between 1965 and 1968, Dr. King shifted his focus toward economic justice – which he highlighted by leading several campaigns in Chicago, Illinois – and international peace – which he championed by speaking out strongly against the Vietnam War. His work in these years culminated in the “Poor Peoples Campaign,” which was a broad effort to assemble a multiracial coalition of impoverished Americans who would advocate for economic change.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s less than thirteen years of nonviolent leadership ended abruptly and tragically on April 4th, 1968 , when he was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. Dr. King’s body was returned to his hometown of Atlanta, Georgia, where his funeral ceremony was attended by high-level leaders of all races and political stripes.

- For more information regarding the Transcription of the King Family Press Conference on the MLK Assassination Trial Verdict December 9, 1999, Atlanta, GA. Click Here

- For more information regarding the Civil Case: King family versus Jowers. Click here .

- Later in 1968, Dr. King’s wife, Mrs. Coretta Scott King, officially founded the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change, which she dedicated to being a “living memorial” aimed at continuing Dr. King’s work on important social ills around the world.

We envision the Beloved Community where injustice ceases and love prevails.

Contact Info

449 Auburn Avenue, NE Atlanta, Georgia 30312

404.526.8900

Quick Links

- History Timeline

- King Holiday

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

Latest News

- Spotlight on Women’s History Month with The King Center

- The King Center Joins the King Family in Mourning the Loss of Naomi Barber King, wife of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr’s Late Brother

Stay Connected

The life of Martin Luther King Jr.

Photo galleries.

- = Key moments in MLK's life and beyond

- = Key moments in the Civil Rights Movement and beyond

- Jan. 15: Michael Luther King Jr., later renamed Martin, is born to schoolteacher Alberta King and Baptist minister Michael Luther King in Atlanta, Ga.

- King graduates from Morehouse College in Atlanta with a B.A.

- Graduates with a B.D. from Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pa.

- June 18: King marries Coretta Scott in Marion, Ala. They will have four children: Yolanda Denise (b.1955), Martin Luther King III (b.1957), Dexter (b.1961), Bernice Albertine (b.1963).

- Brown vs. Board of Education: U.S. Supreme Court bans segregation in public schools.

- September: King moves to Montgomery, Ala., to preach at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church.

- After coursework at New England colleges, King finishes his Ph.D. in systematic theology.

- Bus boycott launches in Montgomery, Ala., after an African-American woman, Rosa Parks, is arrested December 1 for refusing to give up her seat to a white person.

- Jan. 26: King is arrested for driving 30 mph in a 25 mph zone.

- Jan. 30: King's house is bombed.

- Dec. 21: After more than a year of bus boycotts and a legal fight, the Montgomery buses desegregate.

- January: Black ministers form what becomes known as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. King is named first president one month later.

- In this typical year of demonstrations, King travels 780,000 miles and makes 208 speeches.

- Garfield High School becomes the first Seattle high school with a more than 50 percent nonwhite student body.

- At previously all-white Central High in Little Rock, Ark., 1,000 paratroopers are called by President Eisenhower to restore order and escort nine black students.

- King's first book, "Stride Toward Freedom," is published, recounting his recollections of the Montgomery bus boycott. While King is promoting his book in a Harlem book store, an African American woman stabs him.

- King visits India. He had a lifelong admiration for Mohandas K. Gandhi, and credited Gandhi's passive resistance techniques for his civil-rights successes.

- King leaves for Atlanta to pastor his father's church, Ebenezer Baptist Church.

- The sit-in protest movement begins in February at a Woolworth's lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C. and spreads across the nation.

- Freedom rides begin from Washington, D.C: Groups of black and white people ride buses through the South to challenge segregation.

- King makes his only visit to Seattle. He visits numerous places, including two morning assemblies at Garfield High School.

- King meets with President John F. Kennedy to urge support for civil rights.

- Blacks become the majority at Garfield High, 51 percent of the student population - a first for Seattle. The school district average is 5.3 percent.

- Two killed, many injured in riots as James Meredith is enrolled as the first black at the University of Mississippi.

- King leads protests in Birmingham for desegregated department store facilities, and fair hiring.

- April: Arrested after demonstrating in defiance of a court order, King writes "Letter From Birmingham Jail." This eloquent letter, later widely circulated, becomes a classic of the civil-rights movement.

- Police arrest King and other ministers demonstrating in Birmingham, Ala., then turn fire hoses and police dogs on the marchers.

- June 12: Medgar Evers, NAACP leader, is murdered as he enters his home in Jackson, Miss.

- About 1,300 people march from the Central Area to downtown Seattle, demanding greater job opportunities for blacks in department stores. The Bon Marche promises 30 new jobs for blacks.

- About 400 people rally at Seattle City Hall to protest delays in passing an open-housing law. In response, the city forms a 12-member Human Rights Commission but only two blacks are included, prompting a sit-in at City Hall and Seattle's first civil-rights arrests.

- Aug. 28: 250,000 civil-rights supporters attended the March on Washington. At the Lincoln Memorial, King delivers the famous "I have a dream" speech.

- 250,000 people attend the March on Washington, D.C. urging support for pending civil-rights legislation. The event is highlighted by King's "I have a dream" speech.

- The Seattle School District implements a voluntary racial transfer program, mainly aimed at busing black students to mostly white schools.

- Sep. 15: Four girls are killed in a bombing at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala.

- Seattle City Council agrees to put together an open-housing ordinance but insists on putting it on the ballot. Voters defeat it by a 2-to-1 ratio. It will be four more years before an open-housing ordinance becomes law.

- Three civil-rights workers are murdered in Mississippi.

- July 2: President Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

- King's book "Why We Can't Wait" is published.

- King visits with West Berlin Mayor Willy Brant and Pope Paul VI.

- Dec. 10: King wins the Nobel Peace Prize.

- Out of 955 people employed by the Seattle Fire Department, just two are African American, and only one is Asian, account for less than 0.2 and 0.1 percent of the force, respectively. By the end of 1993, the department is 12.2 percent African American and 5.6 percent Asian.

- Jan. 18: King successfully registers to vote at the Hotel Albert in Selma, Ala. and is assaulted by James George Robinson of Birmingham.

- February: King continues to protest discrimination in voter registration and is arrested and jailed. He meets with President Lyndon B. Johnson Feb. 9 and other American leaders about voting rights for African Americans.

- Feb. 21: Malcolm X is murdered. Three men are convicted of his murder.

- Mar. 16-21: King and 3,200 people march from Selma to Montgomery

- Aug. 6: President Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The act, which King sought, authorizes federal examiners to register qualified voters and suspends devices such as literacy tests that aimed to prevent African Americans from voting.

- Aug. 11-16: Watts riots leave 34 dead in Los Angeles.

- Apr. 4: King is assassinated in Memphis, Tenn., by James Earl Ray, unleashing violence in more than 100 cities.

- In response to King's death, Seattle residents hurl firebombs, broke windows, and pelt motorists with rocks. Ten thousand people also march to Seattle Center for a rally in his memory.

- Aaron Dixon becomes first leader of Black Panther Party branch in Seattle.

- There is a rally at Garfield High in support of Dixon, Larry Gossett, and Carl Miller, sentenced to six months in the King County Jail for unlawful assembly in an earlier demonstration. Before the speakers finish, firebombs and rocks begin flying toward cars coming down 23rd Avenue. Sporadic riots break out in Seattle's Central Area during the summer.

- Edwin Pratt, executive director of the Seattle Urban League and a moderate and respected African American leader, is shot to death while standing in the doorway of his home. The murder is never solved.

- Seattle School Board adopts a plan designed to eliminate racial imbalance in schools by fall 1979.

- Seattle becomes the largest city in the United States to desegregate its schools without a court order; nearly one-quarter of the school district's students are bused as part of the "Seattle Plan." Two months later, voters pass an anti-busing initiative. It is later ruled unconstitutional.

- In a blow to efforts to diversify university enrollment, the U.S. Supreme Court outlaws racial quotas in a suit brought by Allan Bakke, a white man who had been turned down by the medical school at University of California, Davis.

- Jan. 20: The first national celebration of King's birthday as a holiday.

- Feb. 24: King County Council passes a motion to rename King County in honor of Martin Luther King Jr.

- Douglas Wilder of Virginia becomes the nation's first African American to be elected state governor.

- The first racially based riots in years erupt in Los Angeles and other cities after a jury acquits L.A. police officers in the videotaped beating of Rodney King, an African American.

- King County's name change is made official by Gov. Christine Gregoire's signing of Senate Bill 5332.

- Jan. 30: King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, dies at age 78. Four presidents – Jimmy Carter, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush – attended her funeral.

- Nov. 4: Barack Obama becomes the first African American to be elected president of the United States.

- Oct. 16: The national memorial to Martin Luther King Jr. is dedicated and opened to the public in Washington, D.C.

- Following the death of Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Fl., the Black Lives Matter movement emerges as a new force for civil rights.

Biography Online

Martin Luther King Biography

Early Life of Martin Luther King

Martin Luther King, Jr. was born in Atlanta on 15 January 1929. Both his father and grandfather were pastors in an African-American Baptist church. M. Luther King attended Morehouse College in Atlanta, (segregated schooling) and then went to study at Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania and Boston University. During his time at University Martin Luther King became aware of the vast inequality and injustice faced by black Americans; in particular, he was influenced by Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violent protest. The philosophy of Gandhi tied in with the teachings of his Baptist faith. At the age of 24, King married Coretta Scott , a beautiful and talented young woman. After getting married, King became a pastor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama.

Montgomery Bus Boycott

It began in innocuous circumstances on 5 December 1955. Rosa Parks, a civil rights activist, refused to give up her seat – she was sitting in a white-only area. This broke the strict segregation of coloured and white people on the Montgomery buses. The bus company refused to back down and so Martin Luther King helped to organise a strike where coloured people refused to use any of the city buses. The boycott lasted for several months, the issue was then brought to the Supreme Court who declared the segregation was unconstitutional.

Civil Rights Movement.

After the success of the Montgomery bus boycott, King and other ministers founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). This proved to be a nucleus for the growing civil rights movement. Later there would be arguments about the best approach to take. In particular, the 1960s saw the rise of the Black power movement, epitomised by Malcolm X and other black nationalist groups. However, King always remained committed to the ideals of non-violent struggle.

Martin Luther King and Malcolm X briefly meet in 1964 before going to listen to a Senate debate about civil rights in Washington. (image Wikicommons )

Speeches of Martin Luther King Jr

Martin Luther King was an inspirational and influential speaker; he had the capacity to move and uplift his audiences. In particular, he could offer a vision of hope. He captured the injustice of the time but also felt that this injustice was like a passing cloud. King frequently made references to God, the Bible and his Christian Faith.

“And this is what Jesus means when he said: “How is it that you can see the mote in your brother’s eye and not see the beam in your own eye?” Or to put it in Moffatt’s translation: “How is it that you see the splinter in your brother’s eye and fail to see the plank in your own eye?” And this is one of the tragedies of human nature. So we begin to love our enemies and love those persons that hate us whether in collective life or individual life by looking at ourselves.” – Martin Luther King

His speeches were largely free of revenge, instead focusing on the need to move forward. He was named as Man of the Year by Time magazine in 1963, it followed his famous and iconic “ I Have a Dream Speech ” – delivered in Washington during a civil rights march.

“I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal.” I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at a table of brotherhood”

– Martin Luther King

The following year, Martin Luther King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work towards social justice. King announced he would turn over the prize money $54,123 to the civil rights movement. With the prestige of the Nobel Prize, King was increasingly consulted by politicians such as Lyndon Johnson .

However, King’s opposition to the Vietnam War did not endear him to the Johnson administration; King also began receiving increased scrutiny from the authorities, such as the FBI.

On April 4th, 1968, King was assassinated. It was one day after he had delivered his final speech “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop”

In his honour, America has instigated a national Martin Luther King Day. He remains symbolic of America’s fight for justice and racial equality.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Martin Luther King Biography” , Oxford, UK. www.biographyonline.net , 11th Feb 2008. Last updated 2 March 2018.

The Autobiography of Martin Luther King

The Autobiography of Martin Luther King at Amazon.com

Strength to Love – The Speeches of Martin Luther King at Amazon

Related pages

- Martin Luther King Quotes

- Martin Luther King Speeches

- Martin Luther Biography

Famous Americans – Great Americans from the Founding Fathers to modern civil rights activists. Including presidents, authors, musicians, entrepreneurs and businessmen.

18 Comments

just because people are colored they should not be treated differently they are also gods creation who he love more than anything

- February 27, 2019 5:11 PM

- By brieanna

Both of martin luther king jr father and grandfather were pastors in an african american baptist church.

- January 15, 2019 6:55 PM

colored does not have a u

- September 28, 2018 6:38 PM

It does in British-English

- October 07, 2018 7:53 AM

it is very use for projects

- August 28, 2018 1:55 PM

Thank you for all of your help this helped me build and essay.

- May 01, 2018 3:55 PM

this also really helped me with a very important project

- April 12, 2018 4:40 PM

This helped me with a project of mine.

- April 06, 2018 12:20 AM

- By Emiliano Carrera

The Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

The first trip had brought a crowd of 15,000 to hear the weary but still commanding civil rights leader speak at Bishop Charles Mason Temple on March 18. He had returned to lead a march 10 days later, only to see the demonstration dissolve into rioting and chaos that left a high school student dead.

Dismayed by the outcome and discouraged by staffers who wanted him to focus on the upcoming "Poor People's Campaign" in the nation's capital, King nevertheless was determined to lead a second, successful march in Memphis to prove that his method of nonviolent demonstration still had teeth.

King was 'exhausted' during his last days

As recounted in the book Redemption: Martin Luther King Jr.'s Last 31 Hours , MLK's Memphis plans faced hurdles from the get-go, starting with the bomb threat that delayed his flight out of Atlanta, Georgia.

After arriving, King and his cohorts were slapped with an injunction that prevented them from leading a demonstration in the city. He huddled with his legal team at the Lorraine Motel to discuss strategy, and followed with another meeting with a local Black power group called the Invaders, aiming to head off a potential repeat of the riot-instigating actions that had torpedoed his last effort.

Fighting a cold, and exhausted after weeks of traveling, King sent his chief lieutenant, Ralph Abernathy , to speak on his behalf at Bishop Charles Mason Temple that evening. Although the stormy weather had depressed the turnout, Abernathy sensed the crowd's disappointment with King's absence and convinced the celebrated orator by phone to make an appearance.

He delivered his famed 'I've Been to the Mountaintop' speech one day before his death

In what became known as his "I've Been to the Mountaintop" speech , King took the audience on a time-traveling journey through the highlights of human civilization and revealed that here, amid the struggle for human rights in the second half of the 20th century, was exactly where he wanted to be. He then recalled how he had been stabbed 10 years earlier when a mere sneeze could have ruptured his aorta and prevented him from being part of civil rights history.

"I don't know what will happen now; we've got some difficult days ahead," he said, nearing the prescient climax. "But it really doesn't matter with me now, because I've been to the mountaintop. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life — longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And so I'm happy tonight; I'm not worried about anything; I'm not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord."

Utterly spent, King was helped back to his seat, tears welling in his eyes. However, the emotional speech was cathartic for a man who had endured so much stress. In the biography Bearing the Cross , Abernathy recalled how his friend seemed "happy and relaxed" at dinner after the rally, and King found the energy to stay up well into the night, joking around with the others.

King was shot in the face on a motel balcony

After waking up late on April 4, King discussed organizational matters with his staffers, before hearing the good news: His lawyers had persuaded the judge to lift the injunction, allowing for a tightly controlled march on April 8.

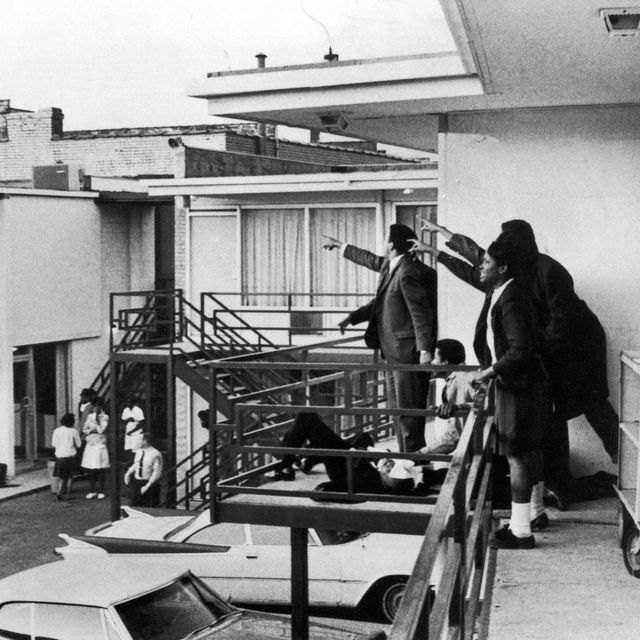

At around 6 p.m., as he prepared for dinner with a local minister, King stepped out to the balcony of room 306 at the Lorraine to chat with colleagues waiting in the courtyard below. A gunshot suddenly pierced the air, and the others recovered from their momentary confusion to find King prone on the balcony, bleeding profusely from the right side of his face.

Although he was rushed off to St. Joseph's Hospital relatively quickly, the bullet had punctured several vital arteries, fractured his spine, and 39-year-old King was declared dead at 7:05 p.m.

READ MORE: 17 Inspiring Quotes by Martin Luther King Jr.

Riots and tributes followed his death

King's assassination led to the outbreak of violence across American cities, with reports of more than 40 casualties, another 3,500 injuries and 27,000 arrests accumulating over the next several days. But there were also noble tributes to the slain civil rights leader: President Lyndon B. Johnson decreed April 7 a day of national mourning, while opening day of the Major League Baseball season and the Academy Awards telecast were both suspended.

The April 8 march went through as planned, with the widowed Coretta Scott King leading an estimated 42,000 demonstrators through the Memphis streets. The following day, another 50,000 supporters accompanied King's mule-drawn casket through downtown Atlanta, to South-View Cemetery.

On April 16, the cause that had consumed the final days of King's life realized its goal, as the city of Memphis agreed to improved wages and the recognition of the sanitation workers' union.

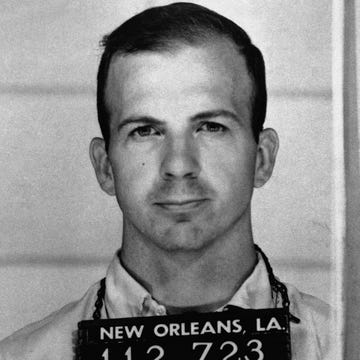

James Earl Ray pleaded guilty, though conspiracy theories remain

Meanwhile, a massive manhunt led the FBI from Bessie Brewer's Rooming House, across from the Lorraine Motel, to California, Alabama, Canada, Portugal and finally to London's Heathrow Airport, where James Earl Ray was apprehended on June 8. He pleaded guilty the following March, earning a 99-year prison sentence, but almost immediately recanted the plea, insisting he was part of a larger conspiracy.

In a twist, many members of King's family and inner circle eventually went public their belief that Ray was not the killer . In 1999, the family won a wrongful death suit against Memphis cafe owner Loyd Jowers, who claimed to have hired the true assassin. This spurred the launch of a new investigation from the U.S. Department of Justice, which ultimately determined that there was no reason to reopen the case .

More than 50 years after King's final breath, the full story behind his killing remains unknown. Nevertheless, the tragedy cemented his place as an icon of the transformative era, forever frozen on the mountaintop as a man who lived out his life in the service of others.

Assassinations

The Manhunt for John Wilkes Booth

Indira Gandhi

Alexei Navalny

Martin Luther King Jr.

James Earl Ray

Malala Yousafzai

Who Killed JFK? You Won’t Believe Us Anyway

Lee Harvey Oswald

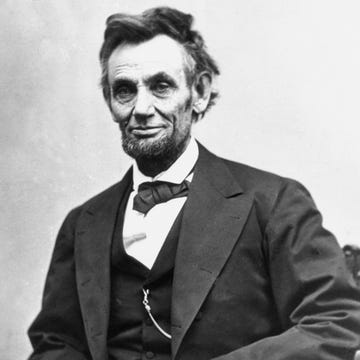

John F. Kennedy

Abraham Lincoln

Biography of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Civil Rights Leader

- People & Events

- Fads & Fashions

- Early 20th Century

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- Women's History

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (January 15, 1929–April 4, 1968) was the charismatic leader of the U.S. civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s. He directed the year-long Montgomery bus boycott , which attracted scrutiny by a wary, divided nation, but his leadership and the resulting Supreme Court ruling against bus segregation brought him fame. He formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to coordinate nonviolent protests and delivered over 2,500 speeches addressing racial injustice, but his life was cut short by an assassin in 1968.

Fast Facts: The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

- Known For : Leader of the U.S. civil rights movement

- Also Known As : Michael Lewis King Jr.

- Born : Jan. 15, 1929 in Atlanta, Georgia

- Parents : Michael King Sr., Alberta Williams

- Died : April 4, 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee

- Education : Crozer Theological Seminary, Boston University

- Published Works : Stride Toward Freedom, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?

- Awards and Honors : Nobel Peace Prize

- Spouse : Coretta Scott

- Children : Yolanda, Martin, Dexter, Bernice

- Notable Quote : "I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character."

Martin Luther King Jr. was born January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia, to Michael King Sr., pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church, and Alberta Williams, a Spelman College graduate and former schoolteacher. King lived with his parents, a sister, and a brother in the Victorian home of his maternal grandparents.

Martin—named Michael Lewis until he was 5—thrived in a middle-class family, going to school, playing football and baseball, delivering newspapers, and doing odd jobs. Their father was involved in the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and had led a successful campaign for equal wages for White and Black Atlanta teachers. When Martin's grandfather died in 1931, Martin's father became pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church, serving for 44 years.

After attending the World Baptist Alliance in Berlin in 1934, King Sr. changed his and his son's name from Michael King to Martin Luther King, after the Protestant reformist. King Sr. was inspired by Martin Luther's courage of confronting institutionalized evil.

Wikimedia Commons

King entered Morehouse College at 15. King's wavering attitude toward his future career in the clergy led him to engage in activities typically not condoned by the church. He played pool, drank beer, and received his lowest academic marks in his first two years at Morehouse.

King studied sociology and considered law school while reading voraciously. He was fascinated by Henry David Thoreau 's essay " On Civil Disobedience" and its idea of noncooperation with an unjust system. King decided that social activism was his calling and religion the best means to that end. He was ordained as a minister in February 1948, the year he graduated with a sociology degree at age 19.

In September 1948, King entered the predominately White Crozer Theological Seminary in Upland, Pennsylvania. He read works by great theologians but despaired that no philosophy was complete within itself. Then, hearing a lecture about Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi , he became captivated by his concept of nonviolent resistance. King concluded that the Christian doctrine of love, operating through nonviolence, could be a powerful weapon for his people.

In 1951, King graduated at the top of his class with a Bachelor of Divinity degree. In September of that year, he enrolled in doctoral studies at Boston University's School of Theology.

While in Boston, King met Coretta Scott , a singer studying voice at the New England Conservatory of Music. While King knew early on that she had all the qualities he desired in a wife, initially, Coretta was hesitant about dating a minister. The couple married on June 18, 1953. King's father performed the ceremony at Coretta's family home in Marion, Alabama. They returned to Boston to complete their degrees.

King was invited to preach in Montgomery, Alabama, at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, which had a history of civil rights activism. The pastor was retiring. King captivated the congregation and became the pastor in April 1954. Coretta, meanwhile, was committed to her husband's work but was conflicted about her role. King wanted her to stay home with their four children: Yolanda, Martin, Dexter, and Bernice. Explaining her feelings on the issue, Coretta told Jeanne Theoharis in a 2018 article in The Guardian , a British newspaper:

“I once told Martin that although I loved being his wife and a mother, if that was all I did I would have gone crazy. I felt a calling on my life from an early age. I knew I had something to contribute to the world.”

And to a degree, King seemed to agree with his wife, saying he fully considered her a partner in the struggle for civil rights as well as on all other issues with which he was involved. Indeed, in his autobiography, he stated:

"I didn't want a wife I couldn't communicate with. I had to have a wife who would be as dedicated as I was. I wish I could say that I led her down this path, but I must say we went down it together because she was as actively involved and concerned when we met as she is now."

Yet, Coretta felt strongly that her role, and the role of women in general in the civil rights movement, had long been "marginalized" and overlooked, according to The Guardian . As early as 1966, Corretta wrote in an article published in the British women's magazine New Lady:

“Not enough attention has been focused on the roles played by women in the struggle….Women have been the backbone of the whole civil rights movement.…Women have been the ones who have made it possible for the movement to be a mass movement.”

Historians and observers have noted that King did not support gender equality in the civil rights movement. In an article in The Chicago Reporter , a monthly publication that covers race and poverty issues, Jeff Kelly Lowenstein wrote that women "played a limited role in the SCLC." Lowenstein further explained:

"Here the experience of legendary organizer Ella Baker is instructive. Baker struggled to have her voice heard...by leaders of the male-dominated organization. This disagreement prompted Baker, who played a key role in the formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee , to counsel young members like John Lewis to retain their independence from the older group. Historian Barbara Ransby wrote in her 2003 biography of Baker that the SCLC ministers were 'not ready to welcome her into the organization on an equal footing' because to do so 'would be too far afield from the gender relations they were used to in the church.'"

Montgomery Bus Boycott

When King arrived in Montgomery to join the Dexter Avenue church, Rosa Parks , secretary of the local NAACP chapter, had been arrested for refusing to relinquish her bus seat to a White man. Parks' December 1, 1955, arrest presented the perfect opportunity to make a case for desegregating the transit system.

E.D. Nixon, former head of the local NAACP chapter, and the Rev. Ralph Abernathy, a close friend of King, contacted King and other clergymen to plan a citywide bus boycott. The group drafted demands and stipulated that no Black person would ride the buses on December 5.

That day, nearly 20,000 Black citizens refused bus rides. Because Black people comprised 90% of the passengers, most buses were empty. When the boycott ended 381 days later, Montgomery's transit system was nearly bankrupt. Additionally, on November 23, in the case of Gayle v. Browder , the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that "Racially segregated transportation systems enforced by the government violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment," according to Oyez, an online archive of U.S. Supreme Court cases operated by the Illinois Institute of Technology's Chicago-Kent College of Law. The court also cited the landmark case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka , where it had ruled in 1954 that "segregation of public education based solely on race (violates) the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment," according to Oyez. On December 20, 1956, the Montgomery Improvement Association voted to end the boycott.

Buoyed by success, the movement's leaders met in January 1957 in Atlanta and formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to coordinate nonviolent protests through Black churches. King was elected president and held the post until his death.

Principles of Nonviolence

In early 1958, King's first book, "Stride Toward Freedom," which detailed the Montgomery bus boycott, was published. While signing books in Harlem, New York, King was stabbed by a Black woman with a mental health condition. As he recovered, he visited India's Gandhi Peace Foundation in February 1959 to refine his protest strategies. In the book, greatly influenced by Gandhi's movement and teachings, he laid six principles, explaining that nonviolence:

Is not a method for cowards; it does resist : King noted that "Gandhi often said that if cowardice is the only alternative to violence, it is better to fight." Nonviolence is the method of a strong person; it is not "stagnant passivity."

Does not seek to defeat or humiliate the opponent, but to win his friendship and understanding : Even in conducting a boycott, for example, the purpose is "to awaken a sense of moral shame in the opponent" and the goal is one of "redemption and reconciliation," King said.

Is directed against forces of evil rather than against persons who happen to be doing the evil: "It is evil that the nonviolent resister seeks to defeat, not the persons victimized by evil," King wrote. The fight is not one of Black people versus White people, but to achieve "but a victory for justice and the forces of light," King wrote.

Is a willingness to accept suffering without retaliation, to accept blows from the opponent without striking back: Again citing Gandhi, King wrote: "The nonviolent resister is willing to accept violence if necessary, but never to inflict it. He does not seek to dodge jail. If going to jail is necessary, he enters it 'as a bridegroom enters the bride’s chamber.'"

Avoids not only external physical violence but also internal violence of spirit: Saying that you win through love not hate, King wrote: "The nonviolent resister not only refuses to shoot his opponent, but he also refuses to hate him."

Is based on the conviction that the universe is on the side of justice: The nonviolent person "can accept suffering without retaliation" because the resister knows that "love" and "justice" will win in the end.

Buyenlarge / Contributor / Getty Images

In April 1963, King and the SCLC joined Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights in a nonviolent campaign to end segregation and force Birmingham, Alabama, businesses to hire Black people. Fire hoses and vicious dogs were unleashed on the protesters by “Bull” Connor's police officers. King was thrown into jail. King spent eight days in the Birmingham jail as a result of this arrest but used the time to write "Letter From a Birmingham Jail," affirming his peaceful philosophy.

The brutal images galvanized the nation. Money poured in to support the protesters; White allies joined demonstrations. By summer, thousands of public facilities nationwide were integrated, and companies began to hire Black people. The resulting political climate pushed the passage of civil rights legislation. On June 11, 1963, President John F. Kennedy drafted the Civil Rights Act of 1964 , which was signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson after Kennedy's assassination. The law prohibited racial discrimination in public, ensured the "constitutional right to vote," and outlawed discrimination in places of employment.

March on Washington

CNP / Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Then came the March on Washington, D.C ., on August 28, 1963. Nearly 250,000 Americans listened to speeches by civil rights activists, but most had come for King. The Kennedy administration, fearing violence, edited a speech by John Lewis of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and invited White organizations to participate, causing some Black people to denigrate the event. Malcolm X labeled it the “farce in Washington."

Crowds far exceeded expectations. Speaker after speaker addressed them. The heat grew oppressive, but then King stood up. His speech started slowly, but King stopped reading from notes, either by inspiration or gospel singer Mahalia Jackson shouting, “Tell 'em about the dream, Martin!”

He had had a dream, he declared, “that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.” It was the most memorable speech of his life.

Nobel Prize

King, now known worldwide, was designated Time magazine's “Man of the Year” in 1963. He won the Nobel Peace Prize the following year and donated the $54,123 in winnings to advancing civil rights.

Not everyone was thrilled by King's success. Since the bus boycott, King had been under scrutiny by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. Hoping to prove King was under communist influence, Hoover filed a request with Attorney General Robert Kennedy to put him under surveillance, including break-ins at homes and offices and wiretaps. However, despite "various kinds of FBI surveillance," the FBI found "no evidence of Communist influence," according to The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University.

In the summer of 1964, King's nonviolent concept was challenged by deadly riots in the North. King believed their origins were segregation and poverty and shifted his focus to poverty, but he couldn't garner support. He organized a campaign against poverty in 1966 and moved his family into one of Chicago's Black neighborhoods, but he found that strategies successful in the South didn't work in Chicago. His efforts were met with "institutional resistance, skepticism from other activists and open violence," according to Matt Pearce in an article in the Los Angeles Times , published in January 2016, the 50th anniversary of King's efforts in the city. Even as he arrived in Chicago, King was met by "a line of police and a mob of angry white people," according to Pearce's article. King even commented on the scene:

“I have never seen, even in Mississippi and Alabama, mobs as hateful as I’ve seen here in Chicago. Yes, it’s definitely a closed society. We’re going to make it an open society.”

Despite the resistance, King and the SCLC worked to fight "slumlords, realtors and Mayor Richard J. Daley’s Democratic machine," according to the Times . But it was an uphill effort. "The civil rights movement had started to splinter. There were more militant activists who disagreed with King’s nonviolent tactics, even booing King at one meeting," Pearce wrote. Black people in the North (and elsewhere) turned from King's peaceful course to the concepts of Malcolm X.

King refused to yield, addressing what he considered the harmful philosophy of Black Power in his last book, "Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?" King sought to clarify the link between poverty and discrimination and to address America's increased involvement in Vietnam, which he considered unjustifiable and discriminatory toward those whose incomes were below the poverty level as well as Black people.

King's last major effort, the Poor People's Campaign, was organized with other civil rights groups to bring impoverished people to live in tent camps on the National Mall starting April 29, 1968.

Earlier that spring, King had gone to Memphis, Tennessee, to join a march supporting a strike by Black sanitation workers. After the march began, riots broke out; 60 people were injured and one person was killed, ending the march.

On April 3, King gave what became his last speech. He wanted a long life, he said, and had been warned of danger in Memphis but said death didn't matter because he'd "been to the mountaintop" and seen "the promised land."

On April 4, 1968, King stepped onto the balcony of Memphis' Lorraine Motel. A rifle bullet tore into his face . He died at St. Joseph's Hospital less than an hour later. King's death brought widespread grief to a violence-weary nation. Riots exploded across the country.

Win McNamee / Getty Images

King's body was brought home to Atlanta to lie at Ebenezer Baptist Church, where he had co-pastored with his father for many years. At King's April 9, 1968, funeral, great words honored the slain leader, but the most apropos eulogy was delivered by King himself, via a recording of his last sermon at Ebenezer:

"If any of you are around when I meet my day, I don't want a long funeral...I'd like someone to mention that day that Martin Luther King Jr. tried to give his life serving others...And I want you to say that I tried to love and serve humanity."

King had achieved much in the short span of 11 years. With accumulated travel topping 6 million miles, King could have gone to the moon and back 13 times. Instead, he traveled the world, making over 2,500 speeches, writing five books, and leading eight major nonviolent efforts for social change. King was arrested and jailed 29 times during his civil rights work, mainly in cities throughout the South, according to the website Face2Face Africa.

King's legacy today lives through the Black Lives Matter movement, which is physically nonviolent but lacks Dr. King's principle on "the internal violence of the spirit" that says one should love, not hate, their oppressor. Dara T. Mathis wrote in an April 3, 2018, article in The Atlantic, that King's legacy of "militant nonviolence lives on in the pockets of mass protests" of the Black Lives Matter movement throughout the country. But Mathis added:

"Conspicuously absent from the language modern activists use, however, is an appeal to America’s innate goodness, a call to fulfill the promise set forth by its Founding Fathers."

And Mathis further noted:

"Although Black Lives Matter practices nonviolence as a matter of strategy, love for the oppressor does not find its way into their ethos."

In 1983, President Ronald Reagan created a national holiday to celebrate the man who did so much for the United States. Reagan summed up King's legacy with these words that he gave during a speech dedicating the holiday to the fallen civil rights leader:

"So, each year on Martin Luther King Day, let us not only recall Dr. King, but rededicate ourselves to the Commandments he believed in and sought to live every day: Thou shall love thy God with all thy heart, and thou shall love thy neighbor as thyself. And I just have to believe that all of us—if all of us, young and old, Republicans and Democrats, do all we can to live up to those Commandments, then we will see the day when Dr. King's dream comes true, and in his words, 'All of God's children will be able to sing with new meaning,...land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrim's pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring.'"

Coretta Scott King, who had fought hard to see the holiday established and was at the White House ceremony that day, perhaps summed up King's legacy most eloquently, sounding wistful and hopeful that her husband's legacy would continue to be embraced:

"He loved unconditionally. He was in constant pursuit of truth, and when he discovered it, he embraced it. His nonviolent campaigns brought about redemption, reconciliation, and justice. He taught us that only peaceful means can bring about peaceful ends, that our goal was to create the love community.

"America is a more democratic nation, a more just nation, a more peaceful nation because Martin Luther King, Jr., became her preeminent nonviolent commander."

Additional References

- Abernathy, Ralph David. "And the Walls Came Tumbling Down: An Autobiography." Paperback, Unabridged edition, Chicago Review Press, April 1, 2010.

- Branch, Taylor. "Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63." America in the King Years, Reprint edition, Simon & Schuster, November 15, 1989.

- Brown v. Board of Education Topeka . oyez.org.

- “ Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) .” The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute , 21 May 2018.

- Gayle v. Browder . oyez.org.

- Garrow, David. "Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference." Paperback, Reprint edition, William Morrow Paperbacks, January 6, 2004.

- Hansen, Drew. " Mahalia Jackson and King's Improvisation . ” The New York Times, Aug. 27, 2013.

- Lowenstein, Jeff Kelly. “ Martin Luther King Jr., Women, and the Possibility of Growth .” Chicago Reporter , 21 Jan. 2019.

- McGrew, Jannell. “ The Montgomery Bus Boycott: They Changed the World .

- “Principles of Nonviolent Resistance By Martin Luther King Jr.” Resource Center for Nonviolence , 8 Aug. 2018.

- “ Remarks on Signing the Bill Making the Birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr., a National Holiday .” Ronald Reagan , reaganlibrary.gov/archive.

- Theoharis, Jeanne. “' I Am Not a Symbol, I Am an Activist': the Untold Story of Coretta Scott King .” The Guardian , Guardian News and Media, 3 Feb. 2018.

- X, Malcolm. "The Autobiography of Malcolm X: As Told to Alex Haley." Alex Haley, Attallah Shabazz, Paperback, Reissue edition, Ballantine Books, November 1992.

Michael Eli Dokos. “ Ever Knew Martin Luther King Jr. Was Arrested 29 Times for His Civil Rights Work? ” Face2Face Africa , 23 Feb. 2020.

- Civil Rights Movement Timeline From 1951 to 1959

- A Profile of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)

- Similarities Between Martin Luther King Jr. And Malcolm X

- Ancestry of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

- 5 Men Who Inspired Martin Luther King, Jr. to Be a Leader

- Ralph Abernathy: Advisor and Confidante to Martin Luther King Jr.

- Organizations of the Civil Rights Movement

- The Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

- Congress of Racial Equality: History and Impact on Civil Rights

- 8 Printout Activities for Martin Luther King Day

- Birmingham Campaign: History, Issues, and Legacy

- Martin Luther King Jr. Quotations

- The 'Big Six' Organizers of the Civil Rights Movement

- Biography of Andrew Young, Civil Rights Activist

- Biography of Diane Nash, Civil Rights Leader and Activist

- Coretta Scott King Quotations

- African American Heroes

Hero for All: Martin Luther King, Jr.

Civil Rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., never backed down in his stand against racism. Learn more about the life of this courageous hero who inspired millions of people to right a historical wrong.

A hero is born

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was born in Atlanta, Georgia , in 1929. At the time in that part of the country, segregation—or the separation of races in places like schools, buses, and restaurants—was the law. He experienced racial predjudice from the time he was very young, which inspired him to dedicate his life to achieving equality and justice for Americans of all colors. King believed that peaceful refusal to obey unjust law was the best way to bring about social change.

Marching Forward

King and his wife, Coretta Scott King, lead demonstrators on the fourth day of a historic five-day march in 1965. Starting in Selma, Alabama , where local African Americans had been campaigning for the right to vote, King led thousands of nonviolent demonstrators 54 miles to the state capitol of Montgomery.

Brave sacrifices

King was arrested several times during his lifetime. In 1960, he joined Black college students in a sit-in at a segregated lunch counter. Presidential candidate John F. Kennedy interceded to have King released from jail, an action that is credited with helping Kennedy win the presidency.

speaking out

King inspires a large crowd with one of his many speeches. Raised in a family of preachers, he's considered one of the greatest speakers in U.S. history.

INSPIRING OTHERS

King waves to supporters from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. during the March on Washington . There, he delivered the "I Have a Dream" speech, which boosted public support for civil rights.

making history

President Lyndon B. Johnson shakes King's hand at the signing of the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act, which outlawed racial segregation in publicly owned facilities.

FAMILY LIFE

King his wife, Coretta Scott King, sit with three of their four children in their Atlanta, Georgia, home in 1963. His wife shared the same commitment to ending the racist system they had both grown up under.

A win for peace

King receives the Nobel Prize for Peace from Gunnar Jahn, president of the Nobel Prize Committee, in Oslo, Norway , on December 10, 1964.

Remembering a hero

A crowd of mourners follows the casket of King through the streets of Atlanta, Georgia, after his assassination in April 4, 1968. King was shot by James Earl Ray on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel. Americans honor the civil rights activist on the third Monday of January each year, Martin Luther King Day.

Learn more at National Geographic.

PHOTOGRAPHS BY: COURTESY THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS; BEN MARTIN, TIME LIFE PICTURES / GETTY IMAGES; HORACE CORT; JULIAN WASSER, TIME LIFE PICTURES / GETTY IMAGES; AFP, GETTY IMAGES; HULTON ARCHIVE / GETTY IMAGES; COURTESY ASSOCIATED PRESS; COURTESY KEYSTONE / GETTY IMAGES; COURTESY HULTON ARCHIVE / GETTY IMAGES

Explore more

African american pioneers of science, black history month, 1963 march on washington.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your California Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell My Info

- National Geographic

- National Geographic Education

- Shop Nat Geo

- Customer Service

- Manage Your Subscription

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Martin Luther King Jr. Assassination

By: History.com Editors

Updated: December 15, 2023 | Original: January 28, 2010

Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968, an event that sent shock waves reverberating around the world. A Baptist minister and founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), King had led the civil rights movement since the mid-1950s, using a combination of impassioned speeches and nonviolent protests to fight segregation and achieve significant civil rights advances for African Americans. His assassination led to an outpouring of anger among Black Americans, as well as a period of national mourning that helped speed the way for an equal housing bill that would be the last significant legislative achievement of the civil rights era.

King Assassination: Background

In the last years of his life, Dr. King faced mounting criticism from young African American activists who favored a more confrontational approach to seeking change. These young radicals stuck closer to the ideals of the Black nationalist leader Malcolm X ( himself assassinated in 1965 ), who had condemned King’s advocacy of nonviolence as “criminal” in the face of the continuing repression suffered by African Americans.

As a result of this opposition, King sought to widen his appeal beyond his own race, speaking out publicly against the Vietnam War and working to form a coalition of poor Americans—Black and white alike—to address such issues as poverty and unemployment.

Did you know? Among the witnesses at King's assassination was Jesse Jackson, one of his closest aides. Ordained as a minister soon after King's death, Jackson went on to form Operation PUSH (People United to Save Humanity) and to run twice for U.S. president, in 1984 and 1988.

In the spring of 1968, while preparing for a planned march to Washington to lobby Congress on behalf of the poor, King and other SCLC members were called to Memphis, Tennessee , to support a sanitation workers’ strike. On the night of April 3, King gave a speech at the Mason Temple Church in Memphis.

In his speech, King seemed to foreshadow his own untimely passing, or at least to strike a particularly reflective note, ending with these now-historic words: “I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land. And I’m happy tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”

In fact, King had already survived an assassination attempt in the shoe section of a Harlem department store on September 20, 1958. The incident only affirmed his belief in non-violence.

Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

At 6:05 p.m. the following day, King was standing on the second-floor balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, where he and his associates were staying, when a sniper’s bullet struck him in the neck. He was rushed to a hospital, where he was pronounced dead about an hour later, at the age of 39.

Shock and distress over the news of King’s death sparked rioting in more than 100 cities around the country, including burning and looting. Amid a wave of national mourning, President Lyndon B. Johnson urged Americans to “reject the blind violence” that had killed King, whom he called the “apostle of nonviolence.”