Keep up to date with the Big Issue

The leading voice on life, politics, culture and social activism direct to your inbox.

The Vagrancy Act: What is it and why is it being scrapped?

The almost 200-year-old law that makes it a criminal offence to sleep rough in England and Wales has finally been repealed – for now.

Rough sleeping is on the rise. Image: Blodeuwedd/Flickr

The 200-year-old Vagrancy Act that criminalises rough sleeping is no more

The controversial law, which has already been repealed in Scotland, makes rough sleeping and begging a criminal offence in England and Wales.

Since early 2021, the Westminster government has pledged to scrap the act . Ministers made good on their promise in April 2022 when the Vagrancy Act was repealed as part of the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill.

Rough sleeping minister Eddie Hughes MP said: “The Vagrancy Act is outdated and needs replacing, and so I’m delighted to announce today the government will repeal it in full.”

Priti Patel’s bill became the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act when it came into force on June 28, repealing the act for good.

Or so it seemed. The government has held a consultation on what should replace the act – despite the widespread belief that nothing is required to fill the void left by the law’s repeal. Ministers could yet bring replacement powers into law through the Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill.

But what is the Vagrancy Act and why is now the right time to scrap it? Let The Big Issue explain.

What is the Vagrancy Act 1824?

The Vagrancy Act makes it a criminal offence to beg or be homeless on the street in England and Wales.

The law was passed in the summer of 1824 – 197 years ago – and was originally intended to deal with a situation far from the reality of street homelessness in present-day UK.

The Vagrancy Act was initially intended to deal with injured ex-serviceman who had become homeless after the Napoleonic Wars. Their crime after serving their country? “Endeavouring by the exposure of wounds or deformities to obtain or gather alms.. or procure charitable contributions of any nature or kind, under any false or fraudulent pretence” according to the act. This essentially means ex-soldiers were begging and the act was brought in to stop it.

The Vagrancy Act also aimed to punish “every person wandering abroad and lodging in any barn or outhouse, or in any deserted or unoccupied building, or in the open air, or under a tent, or in any cart or waggon”. Namely transient people, typically from Scotland or Ireland, who were considered undesirable. The act also represented a threat to Gypsy, Traveller and Roma communities.

Why were there calls for the Vagrancy Act to be scrapped?

The Vagrancy Act does not deal with homelessness in a compassionate fashion, say its opponents.

It is largely recognised that locking up homeless people does little to solve the root causes of why they are on the street in the first place. Punishments under the act can include a £1,000 fine and the possibility of a criminal record – neither of which do anything to help the person out of homelessness.

Conservative MP for the Cities of London and Westminster Nickie Aiken said the act is “simply no longer fit for purpose” ahead of a Westminster Hall debate on the act in April 2021.

“It fails to address the acute 21st-century problems that public sector agencies and charities work tirelessly to deal with among the street population,” she said.

It’s a view shared across the political spectrum and in the homelessness sector.

“The idea that just finding yourself sleeping rough should be a criminal offence doesn’t make any sense to me at all,” said former housing secretary Robert Jenrick, who first said the act should be repealed in the House of Commons back in February 2021.

Crisis chief executive Matt Downie told The Big Issue: “Providing rapid access to housing and the support needed to retain that housing, that’s the answer, not pushing people further away from support because they might be arrested. It is completely obscene that the Vagrancy Act still exists today.”

The act was finally scrapped on June 28 when the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act came into force.

What has the government said about the Vagrancy Act?

The Westminster government repeatedly said that the Vagrancy Act should be scrapped before announcing that it would be removed from the statute book as part of the new policing bill.

Robert Jenrick was the first cabinet minister to reveal the government’s plans in the House of Commons.

The former housing secretary said in February 2021 : “It is my opinion that the Vagrancy Act should be repealed. It is an antiquated piece of legislation whose time has been and gone.

“We should consider carefully whether better, more modern legislation could be introduced to preserve some aspects of it, but the Act itself, I think, should be consigned to history.”

Following Jenrick’s announcement, rough sleeping minister Eddie Hughes said the government was committed to taking prompt action to scrap the act.

But it took almost 15 months for the act to be scrapped.

Despite the government’s commitment, ministers initially knocked back an amendment hoping to scrap the act as part of the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill in the House of Lords on November 25 2021.

There has been more progress in 2022.

Peers voted to scrap the Vagrancy Act in the early hours of January 18 with a majority of 43 votes supporting Lord Best’s amendment to the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill.

The amendment was scheduled to face an MP vote in the Commons in late February but the government tabled its own amendment to the bill on February 22 to axe the act for good.

The news was celebrated by campaigners. Jenrick, who had been lobbying Priti Patel and Michael Gove to table the amendment, said: “This long overdue reform will reframe the issue of homelessness away from it being a question of criminality, and towards our modern understanding of homelessness as a complex health, housing and social challenge.”

Crisis chief executive Matt Downie added: “For almost two hundred years, the criminalisation of homelessness has shamed our society. But now, at long last, the Vagrancy Act’s days are numbered and not a moment too soon.

“This offensive law does nothing to tackle rough sleeping, only entrenching it further in our society by driving people further from support. We know there are better, more effective ways to help people overcome their homelessness.”

What should replace the Vagrancy Act?

That is the question that the Westminster government is currently trying to answer.

Ministers held a four-week consultation on what should replace the act, with anyone able to add their thoughts on the issue up until May 5.

Rough sleeping minister Eddie Hughes said: “We must balance our role in providing essential support for vulnerable people with ensuring that we do not weaken the ability of police to protect communities.”

Homelessness charity St Mungo’s welcomed the consultation and called on ministers to listen to people who have lived experience of homelessness when designing replacement measures.

St Mungo’s then-executive director of strategy and development Rebecca Sycamore said: “St Mungo’s will be responding to the consultation. We believe that the act should be replaced with persistent and trauma informed outreach, which was a key recommendation in the Kerslake Commission on Homelessness and Rough Sleeping .”

However, fellow charity Crisis has questioned initial proposals that would replace the act with new penalties for begging.

Matt Downie, Crisis chief executive, said: “We cannot replace one punitive legislation with another targeting people on the streets. Our core concern is that the proposals are far too wide, could be open to abuse, and lead to people on the streets being punished instead of given the vital help they need. Through our frontline work, we know that an approach based on punishment will drive people away from trying to get support.

“Instead of focussing on measures that may further penalise people on the streets, the government must instead look at how it can encourage a multi-agency approach. This includes ensuring the police can more effectively work with people in this situation, are given training to enable them to do this, and also looking at what wider support from local authorities and other organisations is needed.”

New legislation introduced by the government has called into question whether the act will actually be scrapped for good.

The Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill features a clause the government to “disregard the repeal of the Act”. It would also allow ministers to create “criminal offences or civil penalties” relating to begging or people deemed to be “rogues and vagabonds”.

Conservative MP Nickie Aiken has tabled an amendment to the bill calling for the clause to be scrapped.

She told The Big Issue: “I was surprised and disappointed to see the clause included in the Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill because I thought we’d won the argument quite convincingly.

“I hope it is a genuine mistake and I hope they will withdraw it before the Bill Committee meet. I am confident that if it was taken to a vote I’m not sure the government would win.”

Who opposes the Vagrancy Act?

The campaign standing against the Vagrancy Act has been a long one and homelessness charities, politicians and human rights campaigners have all opposed it in recent years.

Then-Crisis chief executive Jon Sparkes said Jenrick was “absolutely right” to call for the bill to be repealed when the Conservative cabinet minister proposed it in February.

“This archaic piece of law does nothing to tackle the root causes of rough sleeping and instead drives people further away from support,” Sparkes said.

There have been dissenting voices in Westminster too, where the Liberal Democrats’ Layla Moran has been leading the charge.

The Oxfordshire MP has been campaigning against the act since 2018 and introduced a private member’s bill to the House of Commons for a second time in January to repeal the act.

However, despite backing from MPs across the Commons — including Green MP Caroline Lucas and former Culture and Sport Secretary Tracey Crouch — private member’s bills have not been heard in the House during the Covid-19 lockdown.

Moran has branded the act “archaic” and “Dickensian” during her campaigning to scrap it.

There have been grassroots efforts to scrap the act too, including from human rights lawyers at Liberty who joined forces with charities Centrepoint, Cymorth Cymru, Homeless Link, Shelter Cymru, St Mungo’s and The Wallich to battle it.

How widely is the Vagrancy Act used?

There are no official annual national statistics on the Vagrancy Act but figures put together through Freedom of Information requests in recent years have shown use of the almost 200-year-old act is declining.

Just 28 per cent of 305 local authorities told homelessness charity Crisis in 2017 they had used arrests under the Vagrancy Act 1824 to tackle begging and rough sleeping while just seven per cent said they planned to use the act for future enforcement.

Meanwhile, Crisis also reported there were 1,320 people prosecuted under the Vagrancy Act in 2018 – a figure that had halved since 2014.

Current vacancies...

Perhaps the most high profile debate over the use of the Vagrancy Act in recent years came in 2018 when then Windsor and Maidenhead Borough Council leader Simon Dudley called on the act to be used to clear rough sleepers from Windsor ahead of a royal wedding .

Dudley cited “an epidemic of rough sleeping and vagrancy in Windsor” when he wrote to Thames Valley Police ahead of Prince Harry’s wedding to Meghan Markle at Windsor Castle.

- Rough Sleeping

Support the Big Issue

Recommended for you

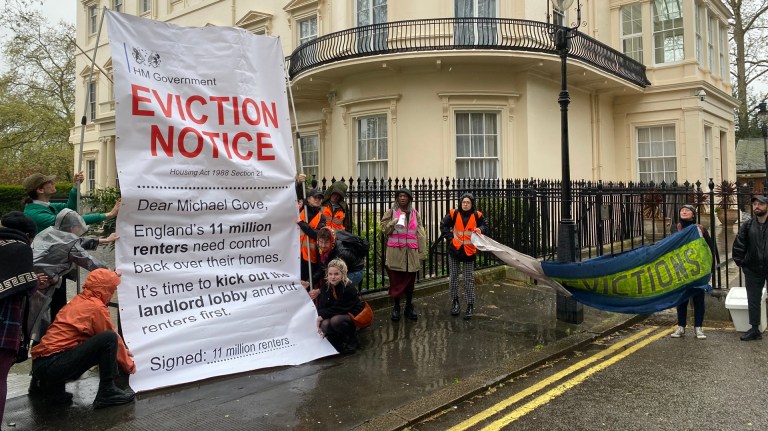

Tory renting reforms pass Commons with no date for no-fault eviction ban: 'It needs major surgery'

Nearly 100 MPs earned more than £10,000 as landlords in the last 12 months

Michael Gove U-turns on promise to ban no-fault evictions before general election

No-fault evictions will be scrapped 'in name only' under Tory renting reforms, campaigners warn

Most popular.

Renters pay their landlords' buy-to-let mortgages, so they should get a share of the profits

Exclusive: Disabled people are 'set up to fail' by the DWP in target-driven disability benefits system, whistleblowers reveal

Cost of living payment 2024: Where to get help now the scheme is over

Strike dates 2023: From train drivers to NHS doctors, here are the dates to know

Get our free pet archive magazine special.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Calls for 195-year-old Vagrancy Act to be scrapped in England and Wales

Law criminalises homeless people for rough sleeping and begging in England and Wales

A leading homelessness charity, police and politicians are calling on the government to scrap a 195-year-old law that criminalises homeless people for rough sleeping and begging in England and Wales.

A report by Crisis , backed by MPs and police representatives, outlines the case for repealing the 1824 Vagrancy Act, which critics warn makes poverty a crime and pushes rough sleepers away from help.

The act hit the headlines when the head of Windsor council suggested police use the law to clear “an epidemic of rough sleeping and vagrancy in Windsor” ahead of last year’s royal wedding.

Jon Sparkes, the chief executive of Crisis, said the law, originally introduced to make it easier for police to clear the streets of destitute soldiers returning from the Napoleonic wars, was a disgrace and that while “there are real solutions to resolving people’s homelessness – arrest and prosecution are not among them”.

He added: “The government has pledged to review the Vagrancy Act as part of its rough sleeping strategy, but it must go further. The act may have been fit for purpose 200 years ago, but it now represents everything that’s wrong with how homeless and vulnerable people are treated. It must be scrapped.”

The report comes after the Guardian revealed councils are using a range of legal powers to clear hundreds of homeless encampments, a figure that has trebled in the last five years .

The government launched a review of homelessness and rough sleeping legislationlast year amid fears current laws are outdated, punitive and discourage people on the street from engaging with help. It is expected to outline its plans in due course.

Although prosecutions under the act have fallen in recent years after a spike between 2013 and 2015, hundreds of people are still prosecuted, according to the Ministry of Justice. There were 1,320 prosecutions in 2018, up 6% on the previous year. The law is most commonly used informally, with the threat of arrest used to move on rough sleepers and those begging, according to the report.

Rough sleeping and homelessness in the UK

Is rough sleeping getting worse?

The government claims rough sleeping in England fell for the first time in eight years in 2018, from 4,751 in 2017 to 4,677. But the body that oversees the quality of official statistics in the UK has said the number should not be trusted after 10% of councils changed their counting methods. Rough sleeping in London has hit a record high , with an 18% rise in 2018-19.

The numbers of people sleeping rough across Scotland have also risen, with 2,682 people reported as having slept rough on at least one occasion.

Shelter, whose figures include rough sleepers and people in temporary accommodation, estimate that overall around 320,000 people are homeless in Britain .

What’s being done about rough sleeping?

The government’s Homelessness Reduction Act 2017, which places new duties on state institutions to intervene earlier to prevent homelessness has been in force for more than a year, but two thirds of councils have warned they cannot afford to comply with it. In 2018, James Brokenshire, the housing secretary, announced a one-off £30m funding pot for immediate support for councils to tackle rough sleeping.

How does the law treat rough sleepers?

Rough sleeping and begging are illegal in ENgland and Wales under the Vagrancy Act 1824, which makes ‘wandering abroad and lodging in any barn or outhouse, or in any deserted or unoccupied building, or in the open air, or under a tent, or in any cart or wagon, and not giving a good account of himself or herself’ liable to a £1,000 fine. Leading homelessness charities, police and politicians have called on the government to scrap the law .

Since 2014, councils have increasingly used public space protection orders to issue £100 fines. The number of homeless camps forcibly removed by councils across the UK has more than trebled in five years , figures show, prompting campaigners to warn that the rough sleeping crisis is out of control and has become an entrenched part of life in the country.

Is austerity a factor in homelessness?

A Labour party analysis has claimed that local government funding cuts are disproportionately hitting areas that have the highest numbers of deaths among homeless people . Nine of the 10 councils with the highest numbers of homeless deaths in England and Wales between 2013 and 2017 have had cuts of more than three times the national average of £254 for every household.

What are the health impacts of rough sleeping?

A study of more than 900 homeless patients at a specialist healthcare centre in the West Midlands found that they were 60 times more likely to visit A&E in a year than the general population in England.

Homeless people were more likely to have a range of medical conditions than the general population. While only 0.9% of the general population are on the register for severe mental health problems, the proportion was more than seven times higher for homeless people, at 6.5%.

Just over 13% of homeless men have a substance dependence, compared with 4.3% of men in the general population. For women the figures were 16.5% and 1.9% respectively. In addition, more than a fifth of homeless people have an alcohol dependence, compared with 1.4% of the general population. Hepatitis C was also more prevalent among homeless people.

Sarah Marsh , Rajeev Syal and Patrick Greenfield

It says rough sleeping in England has increased significantly between 2014 and 2018, rising by 70%, and suggests the act is not the most effective tool for dealing with rough sleeping.

Offences people can be charged with under the Vagrancy Act include begging, which is subject to a maximum fine of £1,000, and it is a criminal offence to sleep “in any deserted or unoccupied building, or in the open air, or under a tent, or in any cart or waggon, not having any visible means of subsistence”.

Crisis says the law in England and Wales should be repealed to mirror Scotland, which scrapped it in 1982 and implemented additional legislation to deal with antisocial and criminal behaviour.

Bernard Hogan-Howe, the former Metropolitan police commissioner who is backing Boris Johnson to be prime minister, is among a number of current and former officers who say the law is not fit for purpose.

“The Vagrancy Act implies that it is the responsibility of the police alone to respond to these issues [rough sleeping and begging], but that is a view firmly rooted in 1824. Nowadays, we know that multi-agency support and the employment of frontline outreach services can make a huge difference in helping people overcome the barriers that would otherwise keep them homeless,” Lord Hogan-Howe said.

David Jamieson, the West Midlands police and crime commissioner, said: “The Vagrancy Act is just so inappropriate. It’s not an offence to be down on your luck and lying in the doorway.”

Despite falling use of the act, many councils opt to use civil powers under the 2014 Antisocial Behaviour Act, such as a public space protection order (PSPOs) to ban begging, rough sleeping and related activities.

A Guardian analysis earlier this year found at least 60 councils were using PSPOs , allowing them to issue £100 fines which, if left unpaid, could result in a summary conviction and a £1,000 penalty. This was despite Home Office guidance not to target the homeless.

Labour has said it would repeal the Vagrancy Act.

The housing and homeless minister, Heather Wheeler, said: “No one in this day and age should be criminalised for having nowhere to live. I’m committed to ending rough sleeping for good and our rough sleeping initiative is providing an estimated 2,600 additional beds and 750 more support staff this year.

“We’re also carrying out a wider review of rough sleeping and homelessness legislation, including the Vagrancy Act, and will set out further steps in due course.”

- Homelessness

- Social exclusion

- Communities

New rules on removing foreign rough sleepers from UK face legal challenge

Rough sleeper gives birth to twins outside wealthiest Cambridge college

Homeless households in England rise by 23% in a year

No home for 280,000 on Christmas Day in England, figures show

Life after homelessness: 'A kind stranger gave me a bed, a key, new clothes and a job'

Homelessness is a national disgrace. Let’s make Britain humane again

Opposition parties jostle for pole position on affordable housing

Homelessness is not inevitable and can be solved – these cities show us how

Life after homelessness: 'I was always creative and ambitious'

Most viewed.

Recommended pages

- Undergraduate open days

- Postgraduate open days

- Accommodation

- Information for teachers

- Maps and directions

- Sport and fitness

Viewing 'the Vagrant': the 1824 Vagrancy Act in action

by Professor Nicholas Crowson, Department of History

views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Birmingham

“Despite all the improvements in homelessness policies, there persists narratives that our Victorian predecessors would recognise, and which stigmatise those most in need.”

In 1896 a “tramp” was given fourteen days’ hard labour after refusing a gardening work-duty at Market Harborough workhouse in Leicestershire. Thirty-three years later, in 1929, Scarborough magistrates were confronted with an elderly man, thought to be in his late 60s, charged with wandering with no visible means of subsistence, but whom fancied himself as a ‘student of law’. Over eighty court appearances had given this gentleman a very personal insight into the application of the vagrancy laws.

These individuals were one and the same: James Butcher.

Using Butcher’s 1896 vagrancy conviction certificate and applying genealogical methods, combined with a range of institution records and newspapers , it is possible to infill what occurred between these two court appearances and his earlier life.

Butcher is one of a number of “vagrants” whose stories are being dramatized by The Cardboard Citizens Theatre Company . In conjunction with Crisis these will be used to explore the historic application of the 1824 Vagrancy Act as part of the Scrap the Act campaign .

The 1824 Vagrancy Act, which remains in force today, was a Georgian response to ‘idle and disorderly persons’ behaving in anti-social ways. It criminalised an extremely wide range of actions, from fortune-telling to begging, rough sleeping to prostitution.

Prosecutions for begging and rough sleeping (sections 3 and 4 of the Act) escalated during the nineteenth century peaking at 38,773 per annum in 1913. Butcher was one of those statistics yet the authorities would have cared little for the reasons he was in this predicament. So how can we move beyond the statistics?

Now it is possible to pursue individuals assumed to be missing from history. It is a challenge complicated by the sharing of common surnames, places of birth and ages. Problems are multiplied by the nature of recording keeping - misspellings, the provision of false information, variations in years of birth, for example. The authorities were alert to the use of aliases. But the ‘information state’ data does not reveal why someone adopted an alias.

The answers rest in the genealogy. Northampton born, Horace Ford (1866-1922) assumed the name of his step-brother, Charles Seaby, motivated by malice. Bristolian, and disgraced Great Western Railways engine driver, John Trowbridge (1858-1921) adopted John Summers – the name of childhood friend whom he met at the Clifton Wood Industrial School.

Others wanted anonymity. Horace Bonsor took John Smith – a name he had to live with whilst serving an eight-year sentence for hayrick-burning. Spanish-born Jose Jimenez (b. 1889) anglicised his name to avoid, unsuccessfully, the attentions of the authorities between 1911 and 1931.

Historians have speculated about the extent of 'tramp mobility', and the routes adopted. The individuals, in my research, moved around in varying degrees and with apparent randomness. Horace Ford confined himself to Northamptonshire, Buckinghamshire and Leicestershire. John Trowbridge circulated all over England and Wales. The cluster of vagrancy convictions along a Devon-Worcestershire axis become distinctive when it is known these were all Great Western Railway stations he had been based at.

Many of the stories reveal past traumas. This could be experiencing domestic violence in childhood as with Horace Ford. Or, as in Horace Bonsor’s case witnessing his father’s suicide, and then being orphaned to the workhouse. For others it was family disputes. Alfred Draper (1861-1924) was taken to court, by his father, for stealing shoe-making tools. The case was dismissed on the proviso Alfred went out into the world and made his own way: this he did by begging around Leicestershire, Staffordshire and Northamptonshire.

For others, their health (whether physical or mental) explains their tramping. Robert Fields (1846-1896) endured paralysis on his right side in 1868. In the view of the Army’s medical discharge officer, for Fields was an infantryman, it was unlikely he would ever earn a living again. He then circulated around eastern England with forays to London. John Trowbridge struggled with alcohol – it was why he was dismissed as an engine driver in 1894. Horace Bonsor had three episodes in asylums suffering “mania” and suicidal thoughts. Today it would be recognised that he had learning difficulties.

Women were homeless too, but like today, how they experienced it could be quite different to men. Some felt the inequities of the Vagrancy Act, although in considerably less numbers than men. Mary Ellen Norton and her mother were repeatedly prosecuted as they moved along the Fosse Way seeking fieldwork. Both Keturah Berrington (1866-1938) and Alberta/Kate Wood (1857-?1947; picture below) found themselves prosecuted for begging with false pretences. Neither was an outsider wayfarer but part of the Leicestershire population negotiating the fine line between poverty and vagrancy.

The reconstruction process is rarely linear: gaps, and tantalising clues, remain unsolved. Take James Butcher whose mental health is questioned by the courts, and who claims to have been sectioned. But, as yet, no asylum admission record can be located.

Born near Blackburn in 1862, out of wedlock, from 1884 he served with the army, including overseas. After dismissal, he circulated the country. As a result of his vagrancy convictions (included several year-long sentences) he cumulatively spent more time in prison than outside. The vagrancy act criminalising, and institutionalising, him on account of his social condition.

To his contemporaries Butcher was a ‘scourge’ and ‘professional waster’. Today, he may experience different treatment, depending upon who located him on the streets. If in touch with an outreach team they would recognise him as having both a poverty and a housing need, and his ‘complex trauma’ would be acknowledged. But Butcher could still face criminalisation.

The 1824 Vagrancy Act remains in force, 2,365 prosecutions in 2016-17, with the authorities having additional anti-social behaviour legal powers. Despite all the improvements in homelessness policies, there persists, especially in the political and media spheres, rhetorical narratives that our Victorian predecessors would recognise and which stigmatise those most in need.

Join the Cardboard Citizens Theatre Company and Crisis on Tuesday 8 December at 6pm for a free online event exploring the Vagrancy Act .

The article originally was published by Crisis .

This blog is based upon an ongoing research project into the hidden histories of homelessness in modern Britain. An article ‘Tramps’ Tales: Discovering the Life-Stories of Late Victorian and Edwardian Vagrants’ is to be published by English Historical Review .

- VisualV1 - Search Created with Sketch. Search

- Other ways to support us

Explore our website

How can we help you?

I'm looking for advice.

Did you know Liberty offers free human rights legal advice?

I want to know what my rights are

Find out more about your rights and how the Human Rights Act protects them

Become a member

Join Liberty for as little as £2.50 a month

- Take action

- Human Rights Act Articles

- History of Human Rights

- Human Rights Case Studies

- Policy work

Vagrancy Act

Thousands of people are still fined and prosecuted for sleeping rough and begging every year thanks to the two-centuries-old Vagrancy Act. Trapping people in cycles of debt and criminality is the opposite of compassion. The Vagrancy Act must be scrapped.

On this page:

What’s happening.

Police forces across England and Wales are still fining and arresting people for begging and rough sleeping under the Vagrancy Act.

This law came into force in 1824 – less than 10 years after the Napoleonic Wars and a decade before the British Empire abolished slavery. It even predates the formation of the police who enforce it. It is the very definition of out-of-date.

WHY SHOULD WE BE CONCERNED?

Twenty thousand people have been prosecuted over the last decade.

The Act can carry fines of £1,000 with the possibility of criminal records – the opposite of a modern and compassionate approach to homelessness.

The former Government promised to review the Vagrancy Act, but this is not good enough. Until it is scrapped, homeless people will continue to suffer and be made more vulnerable instead of receiving the support they need.

WHAT IS LIBERTY DOING ABOUT IT?

We’ve joined leading homelessness charities Crisis, Centre Point, Cymorth Cymru, Homeless Link, Shelter Cymru, St Mungo’s and The Wallich to call on the Government to finally scrap this outdated law.

I'm looking for advice on this

What are my rights on this, did you find this content useful.

Help us make our content even better by letting us know whether you found this page useful or not

Sign up for email updates

Enter your email to receive updates about Liberty’s campaigns and how you can support our work

Your details are safe with us. We won’t ever pass your information on to other organisations for them to market to you.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Featured Content

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- About The British Journal of Criminology

- About the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, the early origins of powers of pre-emptive arrest, the vagrancy act and associated legislation, 1824–1914, pre-emptive policing in the 1920s and 1930s, pre-emptive policing after the second world war, r eferences, the vagrancy act (1824) and the persistence of pre-emptive policing in england since 1750.

*Paul Lawrence, Department of History, Arts Faculty, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, UK; [email protected]

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Paul Lawrence, The Vagrancy Act (1824) and the Persistence of Pre-emptive Policing in England since 1750, The British Journal of Criminology , Volume 57, Issue 3, 1 May 2017, Pages 513–531, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azw008

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This article argues that research into preventive and pre-emptive crime control in the United Kingdom has marginalized the historical persistence of the power to arrest and convict on justified suspicion of intent. It traces the genesis of this power in statute law (particularly the Vagrancy Act of 1824) and demonstrates its consistent use in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It shows how this pre-emptive power was fiercely defended by police authorities, particularly during the rise of the ‘civil liberties’ agenda during the 1930s, only losing ground when use of these powers became entangled with debates about race relations in the 1970s. Overall, the article argues that ‘pre-emptive’ arrest and conviction on suspicion of intent have been a significant component of UK police powers since the later eighteenth century, and seeks to demonstrate the value of historical criminology in problematizing contemporary debates.

It has been argued recently that, since the late twentieth century, the United Kingdom has witnessed a fundamental shift in the temporal focus of the institutions of criminal justice, away from investigating crimes and punishing criminals and towards preventing and pre-empting criminal acts. Following ground-breaking early work ( Steiker 1998 ), researchers have sought to trace a growing state emphasis on the prevention of crime, as opposed to simply its detection and punishment after the fact. This ‘preventive turn’ ( Edwards and Hughes 2009 ) has been traced across ‘a wide range of legal doctrines and penal measures, substantive and procedural, legislative and executive’ ( Dubber 2013 : 47), leading to the claim that we witnessing the ‘rise of the preventive state’ ( Ashworth and Zedner 2014 : 10).

Recent additions to this literature have focussed specifically on the notion of ‘pre-crime’ ( Zedner 2007 ). A pre-crime approach to criminal justice seeks ‘to punish, disrupt, incapacitate or restrict those deemed to embody future crime threats’ ( McCulloch and Wilson 2015 : 1). In this, it has been seen as distinct from a risk-oriented, preventative approach both because it typically anticipates crimes and then proceeds as if they had already happened and because ‘suspicious identity and outlawed associations’ are the basis for state intervention rather than specific criminal acts ( McCulloch and Wilson 2015 : 9). The rise of pre-emptive, ‘pre-crime’ strategies of crime control is rarely seen as a positive development and thus can be read as a contributor to what Waddington (2005 : 353) has called ‘civil libertarian pessimism’—the belief that ‘the inevitable future for civil liberties can only be erosion’.

Although a growing interest in the advantages of historical criminology has been in evidence during same the period as these debates about prevention and pre-emption (see, for example, Bosworth 2001 ; Knepper and Scicluna 2010 ; Lawrence 2012 ), debates about preventive policing and a pre-crime approach have been almost completely focussed on the contemporary period. There is little sense in the literature that, with respect of policing at least, a ‘pre-emptive’ approach or mind-set may not be as novel as has been assumed. Although Zedner (2007 : 264) has argued that it is important not to overstate the ‘epochal nature’ of current trends, much of the criminological literature addressing the rise of the preventive state and the growth of pre-crime approaches has a tendency to view these changes as indicative of a fundamental shift in the practise of criminal justice.

Partly this is because, even among historians concerned with the police, prevention (and certainly pre-emption) has not been seen as integral to the historical practice of policing. A considerable body work on the ‘idea’ of Police in the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and researchers has indicated that a broad conception of the term ‘police’ existed at that point, encompassing a wide range of proposed regulatory activities intended to ensure the healthy functioning of the body politic and prevent crime and other social ills ( Neocleous 2000 ; Dodsworth 2007 ). However, this broad conception is seen to have narrowed as the ‘New Police’ of the nineteenth century developed. The Metropolitan Police of 1829 (and other forces introduced later) certainly had the prevention of crime as a primary duty but this preventive function has customarily been seen as expressed via a narrow focus on deterrence rather than other forms of prophylactic or pre-emptive action ( Emsley 1996 : 25; Lawrence 2011 : xv).

The introduction of uniformed officers patrolling regular beats certainly marked a shift in practice away from the entrepreneurial, reactive policing of the later eighteenth century, as typified by the Bow Street Runners ( Beattie 2012 ). Although this new approach was also often coupled with exhortations from constables to home owners and the business community to secure their goods and property more effectively, overall there has been a tendency to see the enthusiasm for broad powers of preventive policing evident at the start of the nineteenth century as dissipating over time. Even researchers attuned to a historical perspective have focussed on the preventive powers held by the police in supervising known, ‘habitual’ criminals ( Godfrey et al. 2010 ) or concluded that ‘by the mid-nineteenth century, the very idea of ‘preventive policing’ had largely passed out of favour’ ( Ashworth and Zedner 2014 : 41). Preventive policing in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries has thus generally been seen as the ‘path not taken’ ( Garland 2001 , 31–2).

This article, which can serve also as a worked example of the potential advantages of historical criminology, seeks to rebalance current criminological debates about a preventive or pre-emptive turn by showing that, in fact, a demonstrably ‘pre-emptive’ approach has been part of British police practice since the early nineteenth century. Part I will analyse the deep historical roots of legislation which allowed the police to arrest a citizen and obtain a summary conviction on suspicion alone , powers eventually enshrined in Section 4 of the Vagrancy Act (1824). Part II will show how this power of pre-emptive arrest and conviction was extensively used and developed between 1824 and the First World War. Part III will consider the interwar period in detail, analysing how the police lobbied effectively to retain their powers of pre-emptive arrest despite growing pressure from civil liberties organizations and the press. Part IV will consider the continued attempts on the part of the police to hold on to these powers after the Second World War, until eventually the pressure of public opinion grew too great in the late 1970s. In conclusion and throughout, it will be argued that the persistent use of the power to convict on the suspicion of intent to commit a felony requires a reconsideration of the development of pre-emptive policing in the United Kingdom. The efforts made by the police to hold onto this power, and its imaginative deployment in a wide range of contexts, show that this component of the ‘preventive state’ is neither a novel nor an inconsequential development.

There is some evidence that a desire on the part of the state to arrest and detain ‘suspicious’ persons significantly pre-dates the modern period ( Stewart-Brown 1936 ; Duggan 2015 ). However, crime control was ‘not a focus for very much innovative effort on the part of central authorities’ prior to the eighteenth century ( Innes 2009 : 67) and it is primarily from c.1750 onwards that powers of pre-emptive arrest and (more importantly) conviction became codified in law. The crime wave of 1749–53 was crucial to this process, as key reformers such as the London magistrate Henry Fielding became concerned at how ‘audacious, insolent and ungovernable’ the ‘common people’ had become ( Whitehall Evening Post , cited in Rogers 1991 : 87). In his widely read Enquiry ( Fielding 1751 ), Fielding represented the crime wave as a structural crisis of order and argued that measures to increase both popular respect for law and order and to enhance executive authority were required.

Thus, from the 1750s, it is possible to trace a succession of legislation which increased the powers of both magistrates and constables to arrest and convict with a minimum of due process. The Disorderly Houses Act (1751/2 ), for example, gave magistrates the power to detain and question (for six days) anyone ‘suspicious’ apprehended during a general privy search (an annual or biannual routine search of common lodging houses and other premises). The London Streets Act (1771) empowered watchmen to apprehend ‘disorderly persons loitering, wandering or misbehaving themselves’, as well as any ‘whom the said Watchmen shall have reason to suspect of any evil designs’. These were primarily powers of detention rather than arrest, but reflected the growing sense that magistrates needed greater powers to regulate ‘suspicious’ persons.

It was in 1792, however, with the passing of the Middlesex Justices Act (1792) , that the case for extensive preventive powers was more fully elucidated. The main aim of the Act was the creation of seven police officers in London, each staffed by three stipendiary magistrates and six constables ( Beattie 2012 ). However, it also specified broad powers for these magistrates and this concerned many. Charles Fox (and others) argued that Clause D of the Act, which allowed the new magistrates ‘to bring persons before them to inquire into their characters and intentions, and to commit them to prison on such an inquiry’ introduced ‘a power pregnant with abuse’ ( Cobbett 1817 : 1464–5). The clause further specified that ‘ill-disposed and suspected Persons, and reputed Thieves, frequenting the Avenues to places of Publick resort […] with intent to commit felony’ could be convicted on the oath of ‘one credible witness’. Several MPs argued that the clause introduced a new principle into law, by creating a new category of person (the ill-defined ‘reputed thief’). William Windham argued that this appeared to reverse ‘the usual order of things’, by proposing ‘to punish men, not for acts that they committed, but for those which they intended to commit’. He further argued that such a clause was ‘calculated to protect the rich’ and that ‘the poor alone were to suffer by it’ ( Cobbett 1817 : 1466).

The Bill’s introducer (Mr Burton) clarified that ‘the clause ought to be considered a preventative against the commission of crimes, rather than a punishment for criminals’ ( Cobbett 1817 : 1469) and, in the end, the House of Commons took the view that the clause would form part of a temporary, experimental Act, and the Bill was passed. Although the House of Lords also expressed concerns over the clause, most Lords in the end agreed with the sentiment expressed by the Lord Chancellor that it was right that ‘those who inspire in peaceable folk a reasonable suspicion of danger should be called upon to explain their character and remove the grounds for suspicion’ ( Debrett 1792 : 535–6). The 1792 Act thus set a clear precedent around preventive arrest and conviction, and similar clauses were included in subsequent renewals of the Act, as well as in other pieces of policing-related legislation.

The Depredations on the Thames Act (1800) , for example, specified that, ‘suspected persons frequenting the river, or quays, and warehouses, or streets or avenues leading to them, with intent to commit Felony’ could be conveyed by any police constable before a single magistrate and, on the oath of a single witness (usually the police constable) that they were there ‘with such Intent as aforesaid’, could be deemed a rogue and vagabond and subjected to punishment under the 1744 Vagrancy Act. Other legislation, too, such as the Night Poaching Act (1800) and the Preservation of the Peace Act (1812) incorporated similar phraseology, allowing the conviction of ‘divers ill-disposed and suspected persons’ on the grounds of justified suspicion of intent.

It has become common now to see the period 1780–1820 as a ‘tipping point’ in the development of criminal justice in London. The period has been seen by some to be one in which a recognizably ‘modern’ system of justice began to develop (including a salaried magistracy, publicly-accessible police officers and career police officers) but it can also be painted as one in which ‘the law’ moved from being a shared expression of rights and responsibilities to a system for the maintenance of order in a manner reassuring to particular propertied groups within society ( Beattie 2012 ; Hitchcock 2012 ). Certainly, by the early nineteenth century, the power to arrest on suspicion was firmly embedded within both the discourse and practice of policing in London. The stage was thus set for the migration of these pre-emptive powers to national legislation during the 1820s via the transference of key clauses into the Vagrancy Act of 1824.

The early 1820s were a period of particular concern over vagrancy ( Roberts 1991 ; Rogers 1991 ), with Vagrancy Acts passed in 1821, 1822 and 1824. The 1821 Act was primarily concerned with regulating the costs of vagrancy, but the 1822 Act sought a more wholesale reconsideration of all legislation, introducing temporary provisions that were made permanent (and in some instances extended) by the 1824 Act. Obviously, one primary concern of the 1824 Act was with the regulation of begging and rough sleeping. Sections 3 and 4 (still in force) specified that anyone begging or sleeping rough without visible means of subsistence and ‘not giving a good account of himself or herself’ could be arrested and charged. The provisions of the Act also extended punishments to individuals implicated in a broad range of socially ill-favoured behaviours including selling goods without a license, telling fortunes, leaving one’s family chargeable to the parish, street betting, escaping from custody, soliciting by prostitutes and indecent exposure. 1 It is Section 4 of the Act, however, that is the most germane to the issue of pre-emptive policing as it developed the power to arrest and to secure a conviction on the basis of suspected intent (to commit any felonious act, not just one related to vagrancy), using the testimony of just one witness—usually the arresting officer.

Drawing on the prior, metropolitan legislation discussed above, Section 4 of the Act specified that anyone found with housebreaking tools ‘with intent feloniously to break into any Dwelling house, Warehouse etc’, or anyone armed ‘with Intent to commit any felonious Act’ could be charged under the Act. The same clause also specified that every ‘suspected Person or reputed Thief’ found near docks, quays or warehouses, or in any ‘Place of public Resort’ with ‘Intent to commit Felony’ could be deemed a rogue and vagabond. This ‘intent to commit’ clause thus rendered offenders liable to up to 3 months hard labour on first summary conviction by a magistrate. To be abroad in a public place, acting suspiciously and unable to give a good account of oneself was henceforth reason enough for arrest and conviction.

There was surprisingly little debate in 1824 about the provisions of Section 4 of the Act. Some complained, after the act had been passed, that ‘whereas, heretofor, no man could be apprehended but for the commission of an offence’, now ‘being suspected by a magistrate […] draws down all the penalties of a substantive offence absolutely committed’ ( Adolphus 1824 : 33). Parliament, however, did not discuss Section 4 at length during the passing of the Act, and coverage in the press was limited. The reason for this seems clear. Pre-emptive police powers were not a novel or noteworthy development by this point. Rather than part of an effort to control vagrancy per se , the ‘arrest on suspicion of intent’ clauses of the Vagrancy Act should instead be seen as part of an ongoing debate on the notion of ‘police’, both in an expansive sense (how to regulate social behaviour) and in our more modern usage (how, practically, to enforce the law). What is particularly significant about the 1824 Act, however, is the way in which it came to underpin the massive expansion of policing, which began with the founding of the Metropolitan Police in 1829.

The new legislation quickly made its way into handbooks used by Justices of the Peace ( Nolan 1825 ; Robinson 1825 ), and magistrates lost no time in putting the law into effect. On 24 August 1824, for example, there were 10 committals under this legislation during a single session at Bow Street magistrates’ court. Two ‘lads’ charged with ‘lurking about the avenues of the English Opera-House, with intent to commit felony’ were sentenced to two months’ hard labour, two other young men (whom the arresting officers ‘swore they knew to be reputed thieves’) were sent to the treadmill for three weeks, and a further six lads ‘all of them very young’ were committed for various periods on the same charge. In all of these cases, no criminal act had been committed other than that of giving rise to suspicion of intent ( Times 1824 : 3).

Outside London, too, the Act was soon put to use. In Exeter, for example, a youth found in the grounds of a foundry was apprehended as he attempted to run away. The presiding magistrate observed that he had been ‘lurking suspiciously about’ and that although ‘nothing was found on him, nor was anything that night missing from the foundry […] of his bad intentions there could be no doubt’. As the Vagrant Act gave him the power to punish ‘wickedly inclined and disorderly persons’, the magistrate sentenced him to hard labour at the treadmill for two months ( Trewman’s Exeter Flying Post 1825 ).

No official statistics were kept of the work of the summary courts at this point, but such broad powers over ‘suspicious persons’ proved useful enough during the 1820s to make their way in modified form into the Metropolitan Police Acts (1829 and 1839 ) and other local police acts (such as the Cheshire Constables Act 1829 ). These police acts, which underpinned the expansion of new forms of policing during the early part of the century, all drew directly on the same legislative concepts (and indeed prose) as the prior laws already discussed. Clause B of the Metropolitan Police Act (for example) specified that a constable could apprehend ‘all loose idle and disorderly persons […] whom he shall have just cause to suspect of any evil designs, and all persons whom he shall find between sunset and the hour of eight in the forenoon, lying in any highway, yard or other place, or loitering therein, and not giving a satisfactory account of themselves’.

Such police acts primarily conveyed powers of arrest . Suspects still needed then to be examined and charged with an appropriate offence. As such, they established a different form of police power to the Vagrancy Act 1824, which allowed actual conviction on the basis of suspicion of intent alone. Nonetheless, they do indicate a desire to equip the New Police with broad powers of arrest, detention and conviction over a range of individuals felt to be ‘suspicious’. Taken together, the Vagrancy and Police Acts can thus be seen as indicative of the development of pro-active, preventive policing, backed up by swift summary justice. While London led the way, as the boroughs and counties developed their own police forces in the middle decades of the nineteenth century, there were frequent memoranda from regional magistrates and Chief Constables requesting that the powers of arrest and detention contained within the Metropolitan Police Act be extended across the country ( Browne 1862 ).

Returning to the powers conveyed by the Vagrant Act 1824, however, when the recording of judicial statistics for the summary courts began in 1857, it is clear that this act was being well used by the police and the courts. Figure 1 shows the combined total for the two offences covered within Section 4 of the act—‘going equipped’ and ‘frequenting with intent to commit a felony’. Between 1857 and 1911, the combined figure was rarely below 4,000 cases.

![vagrancy case study uk Section 4 Vagrancy Act (1824) cases proceeded against, 1857–1911. Source: Compiled from annual judicial criminal statistics, published within British Parliamentary Papers. Total represents combined figures for the offences of ‘found on inclosed [sic] premises possessing lockpicks etc]’ and ‘frequenting’.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/bjc/57/3/10.1093_bjc_azw008/1/m_azw00801.jpeg?Expires=1716364041&Signature=YQ00vOQHaqc12yi3zdfsbgbaTlzeX-B5um-vGcDpAZgBq3dTDyysTxgYGei~DksNdIxxFfXgNatb8twlgcucLeKOLnb2BVk9bIz7WJec3AVnlKFpX7dNUThLbdighRjDGfbMSYgB6rstfbNpbVyGb~2JJd4oMgmiWYU6~mvBx4bKKTaleK9TUBgFxSTp~cNaXOQ6JCpQ5fVDspRAOq1J6YxyBOU9PYsgGfasHFdXx6ppeso-niBF6n6L06-EJoduiT-V9uhK~NGWgXCJpNZFzqWX-4sZpA0Sn-SB-0XtgxGs46Wh2qHV9DPoFtQxjvZb9qxICjzzbvFE3zetFU5XTg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Section 4 Vagrancy Act (1824) cases proceeded against, 1857–1911. Source: Compiled from annual judicial criminal statistics, published within British Parliamentary Papers. Total represents combined figures for the offences of ‘found on inclosed [sic] premises possessing lockpicks etc]’ and ‘frequenting’.

Although fluctuating considerably, the clause was in constant use until the First World War (around an average of 4715 per annum for the period). As might be expected given its population at the time, London accounted for the largest single set of proceedings. In 1870, for example, the peak year for convictions under Section 4 of the Vagrancy Act, London accounted for 40% of all cases. Moreover, looking more widely, the offence was largely an urban one, with the new industrial boroughs of the north of England accounting for a further 24% of all proceedings. 2 Obviously, while these figures do not necessarily reflect actual levels of offending, they do nonetheless indicate that the use of the pre-emptive powers granted by the Vagrancy Act had become an established tool in the police arsenal.

Looking at the fluctuations in proceedings, the considerable drop in usage post 1871 does not imply a diminution in the use of such powers by the police but rather reflects the impact of the Habitual Criminals Act (1869) and the Prevention of Crimes Act (1871) . Both acts contributed significantly to the power of the state in regard to surveillance and preventive policing in relation to known criminals. The Habitual Criminals Act (1869) pertained primarily to convicts released on license (so-called ‘ticket of leave men’) and Section 8 specified that they could be arrested and subjected to imprisonment for up to a year (with or without hard labour) if they were ‘found by any police officer, in any place, whether public or private, under such circumstances as to satisfy the magistrate […] that he was about to commit […] any crime […] or was waiting for an opportunity to commit […] any crime’.

Importantly, section 9 of the Act also clarified the usage of the Vagrancy Act (1824) by applying the same standards of proof to that act. Driving home the message that the legislation was intended to apply to a class of person rather than a type of act, the wording specified that ‘in proving […] intent it shall not be necessary to show that the person suspected was guilty of any particular act or acts tending to show his purpose or intent, and he may be convicted if from the circumstances of the case, and from his known character […] it appears […] that his intent was to commit a felony’. The Prevention of Crimes Act reaffirmed these key provisions, as well as tightening the reporting restrictions for convicts on license ( Godfrey et al. 2010 ).

Later in the century, the implications of police use of the Vagrancy Act began to be worked through in case law. In 1884, for example, Thomas Wale (26) was charged with ‘frequenting Buckingham Palace Road with intent a felony’, having been observed hanging around and making ‘three distinct attempts to pick pockets’ ( Times 1884 ). However, the presiding magistrate interpreted the legislative term ‘frequenting’ to mean ‘attending a given place repeatedly’ and, as the arresting officer admitted that he had not seen the prisoner in Buckingham Palace Road before the day of his arrest, the prisoner was (‘to his utter surprise’) discharged.

This precedent was obviously something of an inconvenience for the Metropolitan Police and so, at their request, Bow Street Magistrates raised the issue with Godfrey Lushington (Permanent Under-Secretary at the Home Office). He took legal advice within the government and was assured that ‘the word ‘frequenting’ used in the Section 4 of the Vagrant Act could be construed as ‘loitering’ when several suspicious acts are done by the loiterer in the same street on the same day’ ( Ingram 1885 ). Given this advice, and following an article in the Justice of the Peace favourable to this position, the police concluded ‘it would be well to try whether juries will convict on counts framed in accordance with the suggestion of the Justice of the Peace ’ ( Ingram 1885 ). So it proved, and a pattern was set of magistrates resisting some police interpretations of Section 4 of the Vagrancy Act, and the police taking legal advice and then looking for a suitable case to take to appeal to reset the precedent. This pattern of use, challenge and counter-challenge became highly-charged politically after the First World War.

The interwar period was one of broad concern over police powers. Debate was often focussed primarily on corruption ( Emsley 2007 ; Wood 2013 ) but the Royal Commission on Police Powers (1929) did comment on Section 4 of the Vagrancy Act, noting that the police had a tendency ‘to strain the evidence’ when they genuinely believed a prisoner to be guilty. In relation to this tendency, the Commission asserted that it was most apparent in relation to ‘charges of a vague character, such as loitering with intent to commit a felony’, where the ‘corroboration of one constable by another’ tended to ‘increase the chance of a miscarriage of justice’ ( Royal Commission on Police Powers 1929 : 103).

Partly as a reaction to such concerns over police powers, the interwar period also witnessed the inception of civil liberties organizations such as the National Council for Civil Liberties (NCCL). While primarily focussed on monitoring the policing of fascist and anti-fascist demonstrations ( Clark 2012 ), the NCCL also expressed concern about the increasing use of Section 4 of the Vagrancy Act. It noted in 1936, for example, ‘a disquieting increase in charges for frequenting or loitering in a public place with intent to commit a felony’ and quoted a Marylebone magistrate who had found against the police and had commented that they had shown ‘a tendency to bolster up their case on lines that “now we have got them, we must do something about it”’ ( National Council of Civil Liberties 1936 : 16).

As Figure 2 demonstrates, such concerns were not unjustified. The interwar period did indeed witness a significant rise in the number of cases bought under Section 4 of the Vagrancy Act, with the totals for the mid-1930s on a par with those of the 1860s. Arrests in London now accounted for the majority, totalling over 75% of all cases proceeded against ( Home Office 1936 : 106–7). The fall from 1935 onwards was again partly accounted for by the passing of legislation. The Public Order Act (1936) gave the police powers broad powers to arrest without warrant when they suspected an individual was either carrying a weapon in public or planning to engineer a breach of the peace. But it is likely that the drop in the use of Section 4 of the Vagrancy Act in the later 1930s was also the result of increasing scrutiny by the media, growing public concern and a series of important court cases. In the face of these pressures, the police (and the Metropolitan Police in particular) had to lobby energetically in order to retain their Section 4 powers throughout the interwar period.

![vagrancy case study uk Section 4 Vagrancy Act (1824) cases proceeded against, 1922–1938. Source: Compiled from annual judicial criminal statistics, published within British Parliamentary Papers. Total represents combined figures for the offences of ‘found on inclosed [sic] premises possessing lockpicks etc]’ and ‘frequenting’.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/bjc/57/3/10.1093_bjc_azw008/1/m_azw00802.jpeg?Expires=1716364041&Signature=oFbItn~MCB-kABS1BxAftOZtZrA1x9JL2sOa6AfiIca5oBwIqSdSUR9Zrm7QU3uQ8iVJ86o59xW23t1Bc1tfBIH2agPYv6tqujJJpw8Fptah23vj1s4UK9sc1MS3Agjh38q25YuVjC5wyBoUR1R2XM-Dwys-XAdKjRNptfqkJafJbwovpqQUHQIXmrMcIzI0CjRL-TTxwu63EL~kwWFzav12LMzDY57avjZOzHoscxgZylQmj~QxuXHfQyY52QD1Qyn7ORCowmbk9gAoEoN4SfWh9yUn4zIR5JRgP2D-H23j4mniaP3VnwmQl2efVxI8RPEUutAeuyqnITgcYvbt1g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Section 4 Vagrancy Act (1824) cases proceeded against, 1922–1938. Source: Compiled from annual judicial criminal statistics, published within British Parliamentary Papers. Total represents combined figures for the offences of ‘found on inclosed [sic] premises possessing lockpicks etc]’ and ‘frequenting’.

During the First World War, the case of Hartley v. Ellnor (1917) had established the precedent that Section 4 of the Vagrancy Act could be used to arrest individuals as ‘suspected persons’ on the basis of acts committed on the same day as their arrest . Robert Ellnor had been observed by P. C. Hartley repeatedly jostling passengers at the Birmingham tram terminus. Suspecting him of pickpocketing, he arrested Ellnor and the case hinged on whether the jostling observed earlier in the day could have served to make him a ‘suspected person’ under the Vagrancy Act (and thus justifying the final arrest later in the afternoon), or whether prior evidence of bad character was required. The magistrate concluded that it was not and, henceforth, there was no need for the arresting officer to have any foreknowledge of the individual concerned—the observation of a series of suspicious acts on the same day in the same area was enough to justify arrest and conviction.

During the 1920s and early 1930s, Section 4 cases had generally followed this precedent. In the mid-1930s, however, coincident with the rise of both unemployment and fascist/anti-fascist political violence, preventive policing and pre-emptive arrest came under particular scrutiny. There was periodic press interest in unusual cases of arrest on suspicion of intent (such as that of Flying Officer Fitzpatrick, arrested in 1933 for refusing to identify himself to plain clothes officers who he believed were confidence tricksters, or Ronald Roberts, arrested in 1934 while posting a letter late at night). This media coverage often led to calls for the Home Secretary to provide statistics for arrests under Section 4 (HC Deb 2 March 1933, c542; HC Deb 31 May 1934 c337; HC Deb 2 April 1935, c193; HC Debate 5 March 1936, c.1595). The Home Secretary in turn often corresponded with the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, and hence by the mid-1930s, there was a growing awareness on the part of the police of the sensitivity of this issue

In 1936, in response to another request by the Home Secretary for arrest statistics, the Deputy Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police drew up a ‘Secret Memorandum’ circulated within government and to other high-ranking police officials ( Drummond 1936 ). He noted that ‘the energetic deployment of the power of arrest conferred on police by […] the Vagrancy Act 1824 […] [was] a most valuable means of checking crime’. Drummond conceded, however, that while ‘constables must be encouraged to use these powers fearlessly’, there was ‘always the danger that if by mismanagement or ill-luck two or three bad cases were to occur at the same time, a strong demand might develop for the withdrawal or curtailment of the existing powers—which would be little less than disastrous’. The final response drafted by the Commissioner (Philip Game) for the Home Secretary to deliver in the House of Commons was a strong endorsement of the powers, noting that they were ‘of the greatest value’ in preventing crime and that ‘without this statutory power the police would frequently not be in a position to take any effective action’ ( Game 1936 ). Game did conclude privately to the Home Secretary, however, that ‘in view of the recent press agitation’ and given ‘how the House can work itself into a frenzy about an isolated case’ it might be wise to tighten arrest guidelines.

Although directives were issued to clarify procedures, this modest initiative was overtaken by a further court case— Ledwith v. Roberts (1936) . In this case, the defendant had been observed by constables in Liverpool spending 25 minutes in a telephone kiosk, apparently preparing to break it open and steal the coins within. The judge held that this was not sufficient grounds for considering the defendant a ‘suspected person’ and found against the police. The Liverpool police, somewhat aggrieved by this, appealed but this was also rejected on the same grounds, with costs awarded against the police. The presiding judge concluded that ‘it appears […] difficult to think that the legislature intended to leave it to a constable to arrest without a warrant any citizen […] if he suspected that he was loitering for the purpose of committing a crime’ ( Ledwith v. Roberts 1936 ).

The Police Review (1936) outlined the ramifications of this in blunt terms, exclaiming ‘once more the Olympians have dropped a crowbar into the machinery of Police Law […] the total result, in one sentence, is that it has become exceedingly dangerous for a Constable to arrest any person whom he suspects is intending to commit a felony’. The issue remained live throughout 1936. The Chief Constable of Birmingham wrote to the Home Office in November noting that ‘the police throughout the country are rather at sea on the matter and some direction from the Home Office would be most useful’ ( Moriarty 1936 ). A Detective Officers’ Conference, which took place in Bristol in December, discussed the matter and concluded that the upshot of Ledwith v. Roberts was that ‘police powers would in future be severely restricted with regard to suspected persons’ ( Carter 1937 ).

In response to such concerns, the matter was discussed in January 1937 by the ‘Committee on Detective Work, Sub-Committee E’. The meeting was attended by four Home Office Officials, two Inspectors of Constabulary, the Deputy Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police and five Chief Constables. The group noted that although ‘the provisions of Section 4 of the Vagrancy Act were habitually used by the police when they had no other remedy open to them’, they had ‘admittedly been in the habit of occasionally taking a risk’ and would have to ‘act with more caution’ for the time being ( Dowson 1937 ). A plan was then agreed, however, to try and reverse the precedent created by Ledwith v. Roberts by bringing a case similar to Hartley v. Ellnor before a higher court, so as to ‘give a clear decision on the question whether this case was still good law’. Clearly, the desirability pre-emptive policing was such that government officials and the police were prepared to invest time and money in remedying an adverse judicial decision. A suitable case was not long in the finding.

In February 1937, John Smith was seen by two police officers loitering and trying the handles of parked cars in various London streets ( Rawlings v. Smith 1938 ). Smith had initially been spotted by a member of the public, who reported the matter to a uniformed patrol, who in turn took advice from a plain clothes officer in a patrol car. The two officers followed Smith for 90 minutes before arresting him for loitering with intent to steal. Smith initially refused to be fingerprinted or give his name but, on appearing at Bow Street Magistrates’ Court, he was subsequently identified as John Thomas Smith, with a string of aliases and no less than 45 previous convictions, mainly for petty theft. Smith denied the charge and was not previously known to either of the arresting officers.

Considering the case, Sir Rollo Graham Campbell, Chief Magistrate at Bow Street Police Court, held that while the accused was indeed loitering in a public place with intent to commit a felony, the charge of being a suspected person was dubious. He decided that Smith’s previous convictions were too far in the past (he had not been convicted for 4 years) to make him a suspected person. Although he had been arrested for repeatedly trying car door handles, Graham Campbell followed Ledwith v. Roberts in concluding that the act which aroused suspicion and the act which prompted arrest could not be one and the same, and subsequently acquitted Smith.

As per the decision of the Committee on Detective Work, the Metropolitan Police decided to appeal the case. The Commissioner felt that because the decision would be ‘one of very considerable importance to Police administration’ and because ‘the liberty of the subject is involved and […] an unrepresented Respondent might cause adverse comment from the Bench’, it was necessary to arrange appropriate legal representation ( Kendall 1937b ). The Home Office concurred, noting that the case seemed to be ‘as good a one as we are likely to get for an application to the High Court on one of the points which was left uncertain in Ledwith’s case’ ( Robinson 1937 ). In the end, no expense was spared, with the Metropolitan Police arguing ‘it is vital that we should have first class Counsel to argue the point […] we must get Home Office authority to employ a silk’ ( Kendall 1937a ).

The appeal was heard in the High Court in December 1937 before the Lord Chief Justice, who found that Graham Campbell had misinterpreted precedent. As Smith had tried a number of car door handles, these antecedent acts were quite enough to classify him as a suspected person and, as such, he could be arrested under the Vagrancy Act the final time he touched a handle. In other words, Hartley v. Ellnor was reinstated—if a police officer observed an individual behaving suspiciously and believed he was about to commit a crime, this was again sufficient grounds for both arrest and prosecution.

Thus, the police were very keen during the interwar period to preserve the power to arrest and convict simply on suspicion—without any actual crime having taken place. These powers were useful to them and they were prepared to go to considerable trouble to keep them. Although the Metropolitan Police may have been somewhat more restrained in their use of Section 4 in the final few years before the Second World War, the issue of heavy-handed use of powers of arrest on suspicion still often featured in the press and in House of Commons debates. Section 4 continued to be used widely and not always appropriately, a pattern that was to continue in the period following the Second World War.

After 1945, and in the face of cyclical press scrutiny as in the interwar period, the Metropolitan Police continued strongly to defend their use of the power to arrest on suspicion, and this position was generally supported by the Home Office. It was only when the issue became intertwined with race relations in the 1970s that the police position became increasingly untenable. As Figure 3 shows, following a dip in prosecutions attendant to the mass mobilization and disruption of the Second World War, cases remained relatively low until the mid-1950s when they began to rise again. They reached a post-war peak in 1963, with levels again approaching those of 1935 and the 1860s. Significantly, by this point age figures were being recorded and it is noteworthy that although in 1963 the vast majority of proceedings were against adults over 21 years of age, by 1973 this had changed significantly with c.50 per cent of all proceedings against youths under 21 years of age. As in the interwar period, London arrests accounted for the vast majority of all cases.

![vagrancy case study uk Section 4 Vagrancy Act (1824) cases proceeded against, 1947–1979. Source: Compiled from annual judicial criminal statistics, published within British Parliamentary Papers. Total represents combined figures for the offences of ‘found on inclosed [sic] premises possessing lockpicks etc]’ and ‘frequenting’.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/bjc/57/3/10.1093_bjc_azw008/1/m_azw00803.jpeg?Expires=1716364041&Signature=4Smr4DuwTgQ2tKkSpctoenHfgLSdcP4TNM6uBdFOts-odbGoX42DHL7cHuzepWQC84ohW2mELqU-GIzKXWC6N4OBA1rquCQsFoOvNbBHa95jNghiAcLMJJfKR44WE8OcQhJ2j-GNegYqnXvyNEl5WCQNWep2nAz3wpH0dirpT4HqlIAQ5hdMx5P68swzKFLUc0R8FbMd4lTopZZsWMpgePo9k00qj2SPSkrtthuNMIb3YOvJ3eGz64JTKSzg-YhvthMEK1CDQpOBP~l2yShheSTlGRwv9K7KpcHqXB-OsqKmT5oN-9aKu-FUZhU9NtSubRpG86pyZvoNItekT7yf5w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Section 4 Vagrancy Act (1824) cases proceeded against, 1947–1979. Source: Compiled from annual judicial criminal statistics, published within British Parliamentary Papers. Total represents combined figures for the offences of ‘found on inclosed [sic] premises possessing lockpicks etc]’ and ‘frequenting’.

During the 1940s and 1950s, a range of cases established further precedent favourable to the police use of Section 4. Cohen v. Black (1942) , for example, proved that the joint observations of several police officers could be pooled to establish ‘antecedent facts giving rise to suspicion so as to bring the person into the category of a suspected person’. R. v. Clarke (1950) established that evidence of previous convictions were admissible in court to show that the person charged was a ‘suspected person’, even if these previous convictions were unknown to the arresting officer at the time of the arrest . The police themselves also evinced continued zeal in attempting to stretch the terms of the legislation for their own purposes. In 1945, for example, a 15-year-old youth (Alan Robinson) was arrested and charged under Section 4 when found on the roof of a cinema, the contention being that he was about to break in and commit a burglary. Because of the antiquated wording of Section 4 of the Vagrancy Act, the police were forced to admit that they had had to ‘stretch our imagination and the Act a bit’ by describing the cinema as a ‘warehouse’, on the flimsy pretext that ‘films, chocolates, cigarettes and ices’ were stored there overnight ( Rundle 1945 ). Similar cases had occurred before, one of which had resulted in the London School of Economics being described as a warehouse, as books were stored there overnight.

After the Robinson case, the Deputy Assistant Commissioner CID wrote to the Home Office noting that the Vagrancy Act was ‘invaluable’ because it was ‘much used in the prevention of crime by apprehending the offender before he has had time or opportunity to commit an offence’. Concluding that without its continued use, ‘crime figures would be much higher than they are at present’, Howe pressed for a change in the wording of Section 4 so as to make police prosecutions easier ( Howe 1945 ). In reviewing the case, the Director of Public Prosecutions (Theobald Mathews) rejected the request on the grounds that it would ‘open the door to agitation for the repeal of other useful but unpopular parts of this Section by spiritualists and others’ ( Mathews 1945 ). He concluded, however, by restating what had become the standard Home Office position—‘one cannot tinker with the Vagrancy Acts. Their vocabulary and some of their penalties are obsolete, but on the other hand they are useful for dealing with common offences not covered elsewhere’.

Section 4 was in constant use during the 1950s and 1960s, with a Law Society report compiled in 1968 noting that it remained ‘the most statistically significant of all the 1824 Act offences’ and that its practical use was ‘important in combating […] potential motor car thieves […] and pickpockets in places of public resort’ ( Law Society 1968 ). The same report described Section 4 offences as ‘exceptional’ because ‘the previous convictions and bad character of the accused person frequently form part of the prosecution’s case’. Although ‘not unnaturally’, this did ‘provoke resentment and from time to time noises of disapproval from sections of liberal opinion’, the report nonetheless still recommended the retention of the clause.

In 1971, the Home Office set up a Working Party (consisting of representatives of the Home Office, the Director of Public Prosecutions, the Department of Health and Social Security, and the police) to review the vagrancy laws once again. During the course of this review, the Home Office acknowledged that the Vagrancy Act was an unusual piece of legislation in a twentieth-century context, deeming it ‘peculiar insofar as it attempts to control behaviour which is in itself neither a substantive offence nor an attempted offence’ ( Working Party on Street Offences 1973 : 2). That said, it concluded that it was useful to be able to obtain convictions in cases where ‘the conduct of the accused, while going beyond anything likely to be susceptible of an innocent explanation [did] not amount to a substantial step towards the commission of an offence’. As such, the Working Party once again recommended the retention of Section 4 in any proposed legislative redrafting ( Brennan 1973 ).