- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School's In

- In the Media

You are here

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

Is homework a necessary evil?

After decades of debate, researchers are still sorting out the truth about homework’s pros and cons. One point they can agree on: Quality assignments matter.

By Kirsten Weir

March 2016, Vol 47, No. 3

Print version: page 36

- Schools and Classrooms

Homework battles have raged for decades. For as long as kids have been whining about doing their homework, parents and education reformers have complained that homework's benefits are dubious. Meanwhile many teachers argue that take-home lessons are key to helping students learn. Now, as schools are shifting to the new (and hotly debated) Common Core curriculum standards, educators, administrators and researchers are turning a fresh eye toward the question of homework's value.

But when it comes to deciphering the research literature on the subject, homework is anything but an open book.

The 10-minute rule

In many ways, homework seems like common sense. Spend more time practicing multiplication or studying Spanish vocabulary and you should get better at math or Spanish. But it may not be that simple.

Homework can indeed produce academic benefits, such as increased understanding and retention of the material, says Duke University social psychologist Harris Cooper, PhD, one of the nation's leading homework researchers. But not all students benefit. In a review of studies published from 1987 to 2003, Cooper and his colleagues found that homework was linked to better test scores in high school and, to a lesser degree, in middle school. Yet they found only faint evidence that homework provided academic benefit in elementary school ( Review of Educational Research , 2006).

Then again, test scores aren't everything. Homework proponents also cite the nonacademic advantages it might confer, such as the development of personal responsibility, good study habits and time-management skills. But as to hard evidence of those benefits, "the jury is still out," says Mollie Galloway, PhD, associate professor of educational leadership at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon. "I think there's a focus on assigning homework because [teachers] think it has these positive outcomes for study skills and habits. But we don't know for sure that's the case."

Even when homework is helpful, there can be too much of a good thing. "There is a limit to how much kids can benefit from home study," Cooper says. He agrees with an oft-cited rule of thumb that students should do no more than 10 minutes a night per grade level — from about 10 minutes in first grade up to a maximum of about two hours in high school. Both the National Education Association and National Parent Teacher Association support that limit.

Beyond that point, kids don't absorb much useful information, Cooper says. In fact, too much homework can do more harm than good. Researchers have cited drawbacks, including boredom and burnout toward academic material, less time for family and extracurricular activities, lack of sleep and increased stress.

In a recent study of Spanish students, Rubén Fernández-Alonso, PhD, and colleagues found that students who were regularly assigned math and science homework scored higher on standardized tests. But when kids reported having more than 90 to 100 minutes of homework per day, scores declined ( Journal of Educational Psychology , 2015).

"At all grade levels, doing other things after school can have positive effects," Cooper says. "To the extent that homework denies access to other leisure and community activities, it's not serving the child's best interest."

Children of all ages need down time in order to thrive, says Denise Pope, PhD, a professor of education at Stanford University and a co-founder of Challenge Success, a program that partners with secondary schools to implement policies that improve students' academic engagement and well-being.

"Little kids and big kids need unstructured time for play each day," she says. Certainly, time for physical activity is important for kids' health and well-being. But even time spent on social media can help give busy kids' brains a break, she says.

All over the map

But are teachers sticking to the 10-minute rule? Studies attempting to quantify time spent on homework are all over the map, in part because of wide variations in methodology, Pope says.

A 2014 report by the Brookings Institution examined the question of homework, comparing data from a variety of sources. That report cited findings from a 2012 survey of first-year college students in which 38.4 percent reported spending six hours or more per week on homework during their last year of high school. That was down from 49.5 percent in 1986 ( The Brown Center Report on American Education , 2014).

The Brookings report also explored survey data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, which asked 9-, 13- and 17-year-old students how much homework they'd done the previous night. They found that between 1984 and 2012, there was a slight increase in homework for 9-year-olds, but homework amounts for 13- and 17-year-olds stayed roughly the same, or even decreased slightly.

Yet other evidence suggests that some kids might be taking home much more work than they can handle. Robert Pressman, PhD, and colleagues recently investigated the 10-minute rule among more than 1,100 students, and found that elementary-school kids were receiving up to three times as much homework as recommended. As homework load increased, so did family stress, the researchers found ( American Journal of Family Therapy , 2015).

Many high school students also seem to be exceeding the recommended amounts of homework. Pope and Galloway recently surveyed more than 4,300 students from 10 high-achieving high schools. Students reported bringing home an average of just over three hours of homework nightly ( Journal of Experiential Education , 2013).

On the positive side, students who spent more time on homework in that study did report being more behaviorally engaged in school — for instance, giving more effort and paying more attention in class, Galloway says. But they were not more invested in the homework itself. They also reported greater academic stress and less time to balance family, friends and extracurricular activities. They experienced more physical health problems as well, such as headaches, stomach troubles and sleep deprivation. "Three hours per night is too much," Galloway says.

In the high-achieving schools Pope and Galloway studied, more than 90 percent of the students go on to college. There's often intense pressure to succeed academically, from both parents and peers. On top of that, kids in these communities are often overloaded with extracurricular activities, including sports and clubs. "They're very busy," Pope says. "Some kids have up to 40 hours a week — a full-time job's worth — of extracurricular activities." And homework is yet one more commitment on top of all the others.

"Homework has perennially acted as a source of stress for students, so that piece of it is not new," Galloway says. "But especially in upper-middle-class communities, where the focus is on getting ahead, I think the pressure on students has been ratcheted up."

Yet homework can be a problem at the other end of the socioeconomic spectrum as well. Kids from wealthier homes are more likely to have resources such as computers, Internet connections, dedicated areas to do schoolwork and parents who tend to be more educated and more available to help them with tricky assignments. Kids from disadvantaged homes are more likely to work at afterschool jobs, or to be home without supervision in the evenings while their parents work multiple jobs, says Lea Theodore, PhD, a professor of school psychology at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. They are less likely to have computers or a quiet place to do homework in peace.

"Homework can highlight those inequities," she says.

Quantity vs. quality

One point researchers agree on is that for all students, homework quality matters. But too many kids are feeling a lack of engagement with their take-home assignments, many experts say. In Pope and Galloway's research, only 20 percent to 30 percent of students said they felt their homework was useful or meaningful.

"Students are assigned a lot of busywork. They're naming it as a primary stressor, but they don't feel it's supporting their learning," Galloway says.

"Homework that's busywork is not good for anyone," Cooper agrees. Still, he says, different subjects call for different kinds of assignments. "Things like vocabulary and spelling are learned through practice. Other kinds of courses require more integration of material and drawing on different skills."

But critics say those skills can be developed with many fewer hours of homework each week. Why assign 50 math problems, Pope asks, when 10 would be just as constructive? One Advanced Placement biology teacher she worked with through Challenge Success experimented with cutting his homework assignments by a third, and then by half. "Test scores didn't go down," she says. "You can have a rigorous course and not have a crazy homework load."

Still, changing the culture of homework won't be easy. Teachers-to-be get little instruction in homework during their training, Pope says. And despite some vocal parents arguing that kids bring home too much homework, many others get nervous if they think their child doesn't have enough. "Teachers feel pressured to give homework because parents expect it to come home," says Galloway. "When it doesn't, there's this idea that the school might not be doing its job."

Galloway argues teachers and school administrators need to set clear goals when it comes to homework — and parents and students should be in on the discussion, too. "It should be a broader conversation within the community, asking what's the purpose of homework? Why are we giving it? Who is it serving? Who is it not serving?"

Until schools and communities agree to take a hard look at those questions, those backpacks full of take-home assignments will probably keep stirring up more feelings than facts.

Further reading

- Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., & Patall, E. A. (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987-2003. Review of Educational Research, 76 (1), 1–62. doi: 10.3102/00346543076001001

- Galloway, M., Connor, J., & Pope, D. (2013). Nonacademic effects of homework in privileged, high-performing high schools. The Journal of Experimental Education, 81 (4), 490–510. doi: 10.1080/00220973.2012.745469

- Pope, D., Brown, M., & Miles, S. (2015). Overloaded and underprepared: Strategies for stronger schools and healthy, successful kids . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Letters to the Editor

- Send us a letter

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Student Opinion

Should We Get Rid of Homework?

Some educators are pushing to get rid of homework. Would that be a good thing?

By Jeremy Engle and Michael Gonchar

Do you like doing homework? Do you think it has benefited you educationally?

Has homework ever helped you practice a difficult skill — in math, for example — until you mastered it? Has it helped you learn new concepts in history or science? Has it helped to teach you life skills, such as independence and responsibility? Or, have you had a more negative experience with homework? Does it stress you out, numb your brain from busywork or actually make you fall behind in your classes?

Should we get rid of homework?

In “ The Movement to End Homework Is Wrong, ” published in July, the Times Opinion writer Jay Caspian Kang argues that homework may be imperfect, but it still serves an important purpose in school. The essay begins:

Do students really need to do their homework? As a parent and a former teacher, I have been pondering this question for quite a long time. The teacher side of me can acknowledge that there were assignments I gave out to my students that probably had little to no academic value. But I also imagine that some of my students never would have done their basic reading if they hadn’t been trained to complete expected assignments, which would have made the task of teaching an English class nearly impossible. As a parent, I would rather my daughter not get stuck doing the sort of pointless homework I would occasionally assign, but I also think there’s a lot of value in saying, “Hey, a lot of work you’re going to end up doing in your life is pointless, so why not just get used to it?” I certainly am not the only person wondering about the value of homework. Recently, the sociologist Jessica McCrory Calarco and the mathematics education scholars Ilana Horn and Grace Chen published a paper, “ You Need to Be More Responsible: The Myth of Meritocracy and Teachers’ Accounts of Homework Inequalities .” They argued that while there’s some evidence that homework might help students learn, it also exacerbates inequalities and reinforces what they call the “meritocratic” narrative that says kids who do well in school do so because of “individual competence, effort and responsibility.” The authors believe this meritocratic narrative is a myth and that homework — math homework in particular — further entrenches the myth in the minds of teachers and their students. Calarco, Horn and Chen write, “Research has highlighted inequalities in students’ homework production and linked those inequalities to differences in students’ home lives and in the support students’ families can provide.”

Mr. Kang argues:

But there’s a defense of homework that doesn’t really have much to do with class mobility, equality or any sense of reinforcing the notion of meritocracy. It’s one that became quite clear to me when I was a teacher: Kids need to learn how to practice things. Homework, in many cases, is the only ritualized thing they have to do every day. Even if we could perfectly equalize opportunity in school and empower all students not to be encumbered by the weight of their socioeconomic status or ethnicity, I’m not sure what good it would do if the kids didn’t know how to do something relentlessly, over and over again, until they perfected it. Most teachers know that type of progress is very difficult to achieve inside the classroom, regardless of a student’s background, which is why, I imagine, Calarco, Horn and Chen found that most teachers weren’t thinking in a structural inequalities frame. Holistic ideas of education, in which learning is emphasized and students can explore concepts and ideas, are largely for the types of kids who don’t need to worry about class mobility. A defense of rote practice through homework might seem revanchist at this moment, but if we truly believe that schools should teach children lessons that fall outside the meritocracy, I can’t think of one that matters more than the simple satisfaction of mastering something that you were once bad at. That takes homework and the acknowledgment that sometimes a student can get a question wrong and, with proper instruction, eventually get it right.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

- Our Mission

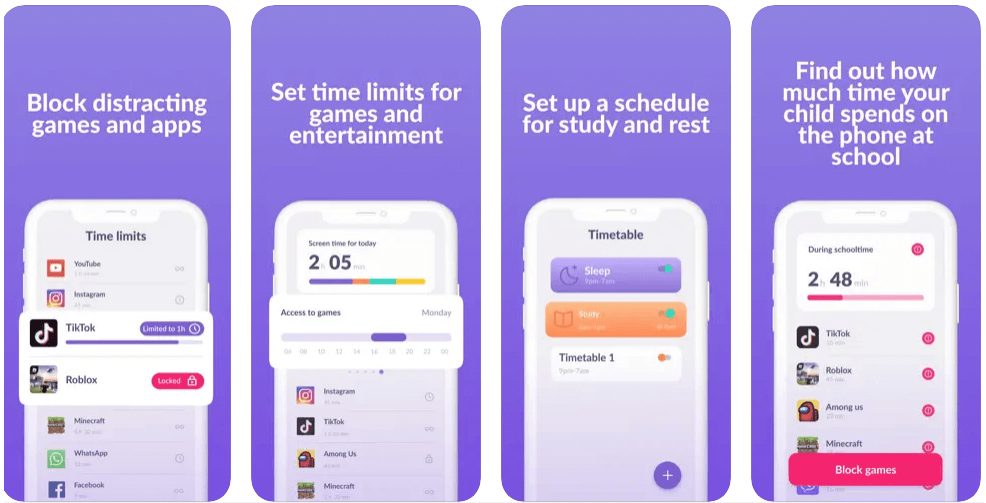

5 Ways to Make Homework More Meaningful

Use these insights from educators—and research—to create homework practices that work for everyone.

Homework tends to be a polarizing topic. While many teachers advocate for its complete elimination, others argue that it provides students with the extra practice they need to solidify their learning and teach them work habits—like managing time and meeting deadlines—that have lifelong benefits.

We recently reached out to teachers in our audience to identify practices that can help educators plot a middle path.

Elementary school teacher John Thomas told Edutopia on Facebook that he finds the best homework looks more like no-strings-attached encouragement for students to read or even play academically-adjacent games with their families. “I encourage reading every night,” Thomas says, but he doesn’t use logs or other means of getting students to track their completion. “Just encouragement and book bags with self selected books students take home for enjoyment.”

Thomas said he also suggests to parents and students that they can play around with “math and science tools” such as “calculators, tape measures, protractors, rulers, money, tangrams, and building blocks.” Math-based games like Yahtzee or dominos, can also serve as enriching—and fun—practice of skills they’re learning.

At the middle and high school level, homework generally increases, and that can be demotivating for teachers, who feel obliged to review or even grade half-hearted submissions. It can also be demotivating for students, too. “Most [students] don’t complete it anyway,” said high school teacher Krystn Stretzinger Charlie on Facebook . “It ends up hurting them more than it helps.”

So how do teachers decide when to—and when not to—assign homework and how do they ensure that the homework they assign feels meaningful, productive, and even motivating to students?

1. Less is More

A 2017 study analyzed the homework assignments of more than 20,000 middle and high school students and found that teachers are often a bad judge of how long homework will take.

According to researchers, students spend as much as 85 minutes or as little as 30 minutes on homework teachers imagined would take students one hour to complete. The researchers concluded that by assigning too much homework , teachers actually increased inequalities between students for “minimal gains in achievement.” Too much homework can overwhelm students who “have more gaps in their knowledge,” the researchers said, and creates situations where homework becomes so time-consuming and frustrating that it demotivates students and turns them off to classwork.

To counteract this, middle school math teacher Crystal Frommert says she focuses on quality over quantity. She cites the National Council for Teachers of Mathematics , which recommends only assigning “what’s necessary to augment instruction,” and adds that if teachers can “get sufficient information by assigning only five problems, then don’t assign fifty.”

Instead of sending students home with worksheets and long problem sets from textbooks that often repeat the same concepts, Frommert recommends assigning part of a page, or even a few specific problems—and explaining to students why these handpicked problems will be helpful practice. When students know there’s thought behind the problems they’re asked to solve at home, “they pay more attention to the condensed assignment because it was tailored for them,” Frommert says.

On Instagram , high school teacher Jacob Palmer said that every now and then he condenses homework down to just one problem that is particularly engaging and challenging: “The depth and exploration that can come from one single problem can be richer than 20 routine problems.”

2. Add Choice to the Equation

Former educator and coach Mike Anderson says teachers can differentiate homework assignments without placing unrealistic demands on their workload by offering students some discretion in the work they complete, and explicitly teaching them “how to choose appropriately challenging work for themselves.”

Instead of assigning the same 20 problems or response questions on a given textbook page to all students, for example, Anderson suggests asking students to refer to the list of questions and choose and complete a designated number of them (three to five, for example) that give students “a little bit of a challenge but that [they] can still solve independently.”

To teach students how to choose well, Anderson actually has students practice choosing homework questions in class before the end of the day, brainstorming in groups and sharing their thoughts about what a good homework question should accomplish. The other part, of course, involves offering students good choices: “Make sure that options for homework focus on the skills being practiced and are open-ended enough for all students to be successful,” he says.

Once students have developed a better understanding of the purpose of challenging themselves to practice and grow as learners, Anderson also periodically asks students to come up with their own ideas for problems or other activities they can use to reinforce learning at home. A simple question, such as “What are some ideas for how you might practice this skill at home?” can be enough to get students sharing ideas, he said.

Jill Kibler, a former high school science teacher, told Edutopia on Facebook that she implemented homework choice in her classroom by allowing students to decide how much of the work they’ve recently turned in they’d like to redo as homework: “Students had one grading cycle (about seven school days) to redo the work they wanted to improve,” she said.

3. Break the Mold

According to high school English teacher Kate Dusto, the work that students produce at home doesn’t have to come in the traditional formats of written responses to a problem. On Instagram , Dusto told Edutopia that homework can often be made more interesting—and engaging—by allowing students to show evidence of their learning in creative ways.

“Offer choices for how they show their learning,” Dusto said. “Record audio or video? Type or use speech to text? Draw or handwrite and then upload a picture?,” the possibilities are endless.

Former educator and author Jay McTighe notes that visual representations such as graphic organizers and concept maps are particularly useful for students attempting to organize new information and solidify their understanding of abstract concepts. For example, students might be asked to “draw a visual web of factors affecting plant growth” in biology class or map out the plot, characters, themes, and settings of a novel or play they’re reading to visualize relationships between different elements of the story and deepen their comprehension of it.

Simple written responses to summarize new learning can also be made more interesting by varying the format, McTighe said. For example, ask students to compose a Tweet in 280 characters or less and answer a question like “What is the big idea that you have learned about _____?” or even record a short audio podcast or video podcast explaining “key concepts from one or more lessons.”

4. Make Homework Voluntary

When Elementary school teacher Jacqueline Worthley Fiorentino stopped assigning mandatory homework to her second grade students and suggested voluntary activities instead, she found that something surprising happened: “They started doing more work at home.”

Some of the simple, voluntary activities she presented students with included encouraging at-home reading (without mandating how much time they should spend reading); sending home weekly spelling words and math facts that will be covered in class, but that should also be mastered by the end of the week: “it will be up to each child to figure out the best way to learn to spell the words correctly or to master the math facts,” she said; and creating voluntary lesson extensions such as pointing students to outside resources—texts, videos or films, webpages, or even online or in-person exhibits—to “expand their knowledge on a topic covered in class.”

Anderson said that for older students, teachers can sometimes make whatever homework they assign a voluntary choice. “Do all students need to practice a skill? If not, you might keep homework invitational,” he said, adding that teachers can tell students: “If you think a little more practice tonight would help you solidify your learning, here are some examples you might try.”

On Facebook , Natisha Wilson, a K-12 gifted students coordinator for an Ohio school district, said that when students are working on a challenging question in class, she’ll give them the option to “take it home and figure it out” if they’re unable to complete it before the end of the period. Often students take her up on this, she said because many of them “can’t stand not knowing the answer.”

5. Grade for Completion—or Don’t Grade at All

Former teacher Rick Wormeli argues that work on homework assignments isn’t “evidence of final level of proficiency”; rather, it’s practice that provides teachers with “feedback and informs where we go next in instruction.”

Grading homework for completion—or not grading at all, Wormeli says—can help students focus on the real task at hand of consolidating understanding and self-monitoring their learning. “When early attempts at mastery are not used against them, and accountability comes in the form of actually learning content, adolescents flourish.”

High school science teacher John Scali agreed , confirming that grading for “completion and timeliness” rather than for “correctness” makes students “more likely to do the work, especially if it ties directly into what we are doing in class the next day” without worrying about being “100% correct.” On Instagram , middle school math teacher Traci Hawks noted that any assignments that are completed and show work—even if the answer is wrong—gets a 100 from her.

But Frommert said that even grading for completion can be time consuming for teachers, and fraught for students if they don’t have home environments that are supportive of homework, or if they have jobs or other after school activities.

Instead of traditional grading, she suggests alternatives to holding students accountable for homework, such as student presentations, or even group discussions and debates as a way to check for understanding. For example, students can debate which method is best to solve a problem, or discuss their prospective solutions in small groups. “Communicating their mathematical thinking deepens their understanding,” Frommert says.

Is Homework Good for Kids? Here’s What the Research Says

A s kids return to school, debate is heating up once again over how they should spend their time after they leave the classroom for the day.

The no-homework policy of a second-grade teacher in Texas went viral last week , earning praise from parents across the country who lament the heavy workload often assigned to young students. Brandy Young told parents she would not formally assign any homework this year, asking students instead to eat dinner with their families, play outside and go to bed early.

But the question of how much work children should be doing outside of school remains controversial, and plenty of parents take issue with no-homework policies, worried their kids are losing a potential academic advantage. Here’s what you need to know:

For decades, the homework standard has been a “10-minute rule,” which recommends a daily maximum of 10 minutes of homework per grade level. Second graders, for example, should do about 20 minutes of homework each night. High school seniors should complete about two hours of homework each night. The National PTA and the National Education Association both support that guideline.

But some schools have begun to give their youngest students a break. A Massachusetts elementary school has announced a no-homework pilot program for the coming school year, lengthening the school day by two hours to provide more in-class instruction. “We really want kids to go home at 4 o’clock, tired. We want their brain to be tired,” Kelly Elementary School Principal Jackie Glasheen said in an interview with a local TV station . “We want them to enjoy their families. We want them to go to soccer practice or football practice, and we want them to go to bed. And that’s it.”

A New York City public elementary school implemented a similar policy last year, eliminating traditional homework assignments in favor of family time. The change was quickly met with outrage from some parents, though it earned support from other education leaders.

New solutions and approaches to homework differ by community, and these local debates are complicated by the fact that even education experts disagree about what’s best for kids.

The research

The most comprehensive research on homework to date comes from a 2006 meta-analysis by Duke University psychology professor Harris Cooper, who found evidence of a positive correlation between homework and student achievement, meaning students who did homework performed better in school. The correlation was stronger for older students—in seventh through 12th grade—than for those in younger grades, for whom there was a weak relationship between homework and performance.

Cooper’s analysis focused on how homework impacts academic achievement—test scores, for example. His report noted that homework is also thought to improve study habits, attitudes toward school, self-discipline, inquisitiveness and independent problem solving skills. On the other hand, some studies he examined showed that homework can cause physical and emotional fatigue, fuel negative attitudes about learning and limit leisure time for children. At the end of his analysis, Cooper recommended further study of such potential effects of homework.

Despite the weak correlation between homework and performance for young children, Cooper argues that a small amount of homework is useful for all students. Second-graders should not be doing two hours of homework each night, he said, but they also shouldn’t be doing no homework.

Not all education experts agree entirely with Cooper’s assessment.

Cathy Vatterott, an education professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, supports the “10-minute rule” as a maximum, but she thinks there is not sufficient proof that homework is helpful for students in elementary school.

“Correlation is not causation,” she said. “Does homework cause achievement, or do high achievers do more homework?”

Vatterott, the author of Rethinking Homework: Best Practices That Support Diverse Needs , thinks there should be more emphasis on improving the quality of homework tasks, and she supports efforts to eliminate homework for younger kids.

“I have no concerns about students not starting homework until fourth grade or fifth grade,” she said, noting that while the debate over homework will undoubtedly continue, she has noticed a trend toward limiting, if not eliminating, homework in elementary school.

The issue has been debated for decades. A TIME cover in 1999 read: “Too much homework! How it’s hurting our kids, and what parents should do about it.” The accompanying story noted that the launch of Sputnik in 1957 led to a push for better math and science education in the U.S. The ensuing pressure to be competitive on a global scale, plus the increasingly demanding college admissions process, fueled the practice of assigning homework.

“The complaints are cyclical, and we’re in the part of the cycle now where the concern is for too much,” Cooper said. “You can go back to the 1970s, when you’ll find there were concerns that there was too little, when we were concerned about our global competitiveness.”

Cooper acknowledged that some students really are bringing home too much homework, and their parents are right to be concerned.

“A good way to think about homework is the way you think about medications or dietary supplements,” he said. “If you take too little, they’ll have no effect. If you take too much, they can kill you. If you take the right amount, you’ll get better.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Joe Biden Leads

- There's Something Different About Will Smith

- What Animal Studies Are Revealing About Their Minds—and Ours

- How Private Donors Shape Birth-Control Choices

- What a Hospice Nurse Wants You to Know About Death

- 15 LGBTQ+ Books to Read for Pride

- TIME100 Most Influential Companies 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Katie Reilly at [email protected]

Do our kids have too much homework?

by: Marian Wilde | Updated: January 31, 2024

Print article

Many students and their parents are frazzled by the amount of homework being piled on in the schools. Yet many researchers say that American students have just the right amount of homework.

“Kids today are overwhelmed!” a parent recently wrote in an email to GreatSchools.org “My first-grade son was required to research a significant person from history and write a paper of at least two pages about the person, with a bibliography. How can he be expected to do that by himself? He just started to learn to read and write a couple of months ago. Schools are pushing too hard and expecting too much from kids.”

Diane Garfield, a fifth grade teacher in San Francisco, concurs. “I believe that we’re stressing children out,” she says.

But hold on, it’s not just the kids who are stressed out . “Teachers nowadays assign these almost college-level projects with requirements that make my mouth fall open with disbelief,” says another frustrated parent. “It’s not just the kids who suffer!”

“How many people take home an average of two hours or more of work that must be completed for the next day?” asks Tonya Noonan Herring, a New Mexico mother of three, an attorney and a former high school English teacher. “Most of us, even attorneys, do not do this. Bottom line: students have too much homework and most of it is not productive or necessary.”

Research about homework

How do educational researchers weigh in on the issue? According to Brian Gill, a senior social scientist at the Rand Corporation, there is no evidence that kids are doing more homework than they did before.

“If you look at high school kids in the late ’90s, they’re not doing substantially more homework than kids did in the ’80s, ’70s, ’60s or the ’40s,” he says. “In fact, the trends through most of this time period are pretty flat. And most high school students in this country don’t do a lot of homework. The median appears to be about four hours a week.”

Education researchers like Gill base their conclusions, in part, on data gathered by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) tests.

“It doesn’t suggest that most kids are doing a tremendous amount,” says Gill. “That’s not to say there aren’t any kids with too much homework. There surely are some. There’s enormous variation across communities. But it’s not a crisis in that it’s a very small proportion of kids who are spending an enormous amount of time on homework.”

Etta Kralovec, author of The End of Homework: How Homework Disrupts Families, Overburdens Children, and Limits Learning , disagrees, saying NAEP data is not a reliable source of information. “Students take the NAEP test and one of the questions they have to fill out is, ‘How much homework did you do last night’ Anybody who knows schools knows that teachers by and large do not give homework the night before a national assessment. It just doesn’t happen. Teachers are very clear with kids that they need to get a good night’s sleep and they need to eat well to prepare for a test.

“So asking a kid how much homework they did the night before a national test and claiming that that data tells us anything about the general run of the mill experience of kids and homework over the school year is, I think, really dishonest.”

Further muddying the waters is an AP/AOL poll that suggests that most Americans feel that their children are getting the right amount of homework. It found that 57% of parents felt that their child was assigned about the right amount of homework, 23% thought there was too little and 19% thought there was too much.

One indisputable fact

One homework fact that educators do agree upon is that the young child today is doing more homework than ever before.

“Parents are correct in saying that they didn’t get homework in the early grades and that their kids do,” says Harris Cooper, professor of psychology and director of the education program at Duke University.

Gill quantifies the change this way: “There has been some increase in homework for the kids in kindergarten, first grade, and second grade. But it’s been an increase from zero to 20 minutes a day. So that is something that’s fairly new in the last quarter century.”

The history of homework

In his research, Gill found that homework has always been controversial. “Around the turn of the 20th century, the Ladies’ Home Journal carried on a crusade against homework. They thought that kids were better off spending their time outside playing and looking at clouds. The most spectacular success this movement had was in the state of California, where in 1901 the legislature passed a law abolishing homework in grades K-8. That lasted about 15 years and then was quietly repealed. Then there was a lot of activism against homework again in the 1930s.”

The proponents of homework have remained consistent in their reasons for why homework is a beneficial practice, says Gill. “One, it extends the work in the classroom with additional time on task. Second, it develops habits of independent study. Third, it’s a form of communication between the school and the parents. It gives parents an idea of what their kids are doing in school.”

The anti-homework crowd has also been consistent in their reasons for wanting to abolish or reduce homework.

“The first one is children’s health,” says Gill. “A hundred years ago, you had medical doctors testifying that heavy loads of books were causing children’s spines to be bent.”

The more things change, the more they stay the same, it seems. There were also concerns about excessive amounts of stress .

“Although they didn’t use the term ‘stress,'” says Gill. “They worried about ‘nervous breakdowns.'”

“In the 1930s, there were lots of graduate students in education schools around the country who were doing experiments that claimed to show that homework had no academic value — that kids who got homework didn’t learn any more than kids who didn’t,” Gill continues. Also, a lot of the opposition to homework, in the first half of the 20th century, was motivated by a notion that it was a leftover from a 19th-century model of schooling, which was based on recitation, memorization and drill. Progressive educators were trying to replace that with something more creative, something more interesting to kids.”

The more-is-better movement

Garfield, the San Francisco fifth-grade teacher, says that when she started teaching 30 years ago, she didn’t give any homework. “Then parents started asking for it,” she says. “I got In junior high and high school there’s so much homework, they need to get prepared.” So I bought that one. I said, ‘OK, they need to be prepared.’ But they don’t need two hours.”

Cooper sees the trend toward more homework as symptomatic of high-achieving parents who want the best for their children. “Part of it, I think, is pressure from the parents with regard to their desire to have their kids be competitive for the best universities in the country. The communities in which homework is being piled on are generally affluent communities.”

The less-is-better campaign

Alfie Kohn, a widely-admired progressive writer on education and parenting, published a sharp rebuttal to the more-homework-is-better argument in his 2006 book The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing . Kohn criticized the pro-homework studies that Cooper referenced as “inconclusive… they only show an association, not a causal relationship” and he titled his first chapter “Missing Out on Their Childhoods.”

Vera Goodman’s 2020 book, Simply Too Much Homework: What Can We Do? , repeats Kohn’s scrutiny and urges parents to appeal to school and government leaders to revise homework policies. Goodman believes today’s homework load stresses out teachers, parents, and students, deprives children of unstructured time for play, hobbies, and individual pursuits, and inhibits the joy of learning.

Homework guidelines

What’s a parent to do, you ask? Fortunately, there are some sanity-saving homework guidelines.

Cooper points to “The 10-Minute Rule” formulated by the National PTA and the National Education Association, which suggests that kids should be doing about 10 minutes of homework per night per grade level. In other words, 10 minutes for first-graders, 20 for second-graders and so on.

Too much homework vs. the optimal amount

Cooper has found that the correlation between homework and achievement is generally supportive of these guidelines. “We found that for kids in elementary school there was hardly any relationship between how much homework young children did and how well they were doing in school, but in middle school the relationship is positive and increases until the kids were doing between an hour to two hours a night, which is right where the 10-minute rule says it’s going to be optimal.

“After that it didn’t go up anymore. Kids that reported doing more than two hours of homework a night in middle school weren’t doing any better in school than kids who were doing between an hour to two hours.”

Garfield has a very clear homework policy that she distributes to her parents at the beginning of each school year. “I give one subject a night. It’s what we were studying in class or preparation for the next day. It should be done within half an hour at most. I believe that children have many outside activities now and they also need to live fully as children. To have them work for six hours a day at school and then go home and work for hours at night does not seem right. It doesn’t allow them to have a childhood.”

International comparisons

How do American kids fare when compared to students in other countries? Professors Gerald LeTendre and David Baker of Pennsylvania State University conclude in their 2005 book, National Differences, Global Similarities: World Culture and the Future of Schooling, that American middle schoolers do more homework than their peers in Japan, Korea, or Taiwan, but less than their peers in Singapore and Hong Kong.

One of the surprising findings of their research was that more homework does not correlate with higher test scores. LeTendre notes: “That really flummoxes people because they say, ‘Doesn’t doing more homework mean getting better scores?’ The answer quite simply is no.”

Homework is a complicated thing

To be effective, homework must be used in a certain way, he says. “Let me give you an example. Most homework in the fourth grade in the U.S. is worksheets. Fill them out, turn them in, maybe the teacher will check them, maybe not. That is a very ineffective use of homework. An effective use of homework would be the teacher sitting down and thinking ‘Elizabeth has trouble with number placement, so I’m going to give her seven problems on number placement.’ Then the next day the teacher sits down with Elizabeth and she says, ‘Was this hard for you? Where did you have difficulty?’ Then she gives Elizabeth either more or less material. As you can imagine, that kind of homework rarely happens.”

Shotgun homework

“What typically happens is people give what we call ‘shotgun homework’: blanket drills, questions and problems from the book. On a national level that’s associated with less well-functioning school systems,” he says. “In a sense, you could sort of think of it as a sign of weaker teachers or less well-prepared teachers. Over time, we see that in elementary and middle schools more and more homework is being given, and that countries around the world are doing this in an attempt to increase their test scores, and that is basically a failing strategy.”

Quality not quantity?

“ The Case for (Quality) Homework: Why It Improves Learning, and How Parents Can Help ,” a 2019 paper written by Boston University psychologist Janine Bempechat, asks for homework that specifically helps children “confront ever-more-complex tasks” that enable them to gain resilience and embrace challenges.

Similar research from University of Ovideo in Spain titled “ Homework: Facts and Fiction 2021 ” says evidence shows that how homework is applied is more important than how much is required, and it asserts that a moderate amount of homework yields the most academic achievement. The most important aspect of quality homework assignment? The effort required and the emotions prompted by the task.

Robyn Jackson, author of How to Plan Rigorous Instruction and other media about rigor says the key to quality homework is not the time spent, but the rigor — or mental challenge — involved. ( Read more about how to evaluate your child’s homework for rigor here .)

Nightly reading as a homework replacement

Across the country, many elementary schools have replaced homework with a nightly reading requirement. There are many benefits to children reading every night , either out loud with a parent or independently: it increases their vocabulary, imagination, concentration, memory, empathy, academic ability, knowledge of different cultures and perspectives. Plus, it reduces stress, helps kids sleep, and bonds children to their cuddling parents or guardians. Twenty to 30 minutes of reading each day is generally recommended.

But, is this always possible, or even ideal?

No, it’s not.

Alfie Kohn criticizes this added assignment in his blog post, “ How To Create Nonreaders .” He cites an example from a parent (Julie King) who reports, “Our children are now expected to read 20 minutes a night, and record such on their homework sheet. What parents are discovering (surprise) is that those kids who used to sit down and read for pleasure — the kids who would get lost in a book and have to be told to put it down to eat/play/whatever — are now setting the timer… and stopping when the timer dings. … Reading has become a chore, like brushing your teeth.”

The take-away from Kohn? Don’t undermine reading for pleasure by turning it into another task burdening your child’s tired brain.

Additional resources

Books Simply Too Much Homework: What Can We do? by Vera Goodman, Trafford Publishing, 2020

The Case Against Homework: How Homework is Hurting Children and What Parents Can Do About It by Sara Bennett and Nancy Kalish, Crown Publishers, 2007

The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing by Alfie Kohn, Hatchett Books, 2006 The End of Homework: How Homework Disrupts Families, Overburdens Children, and Limits Learning by Etta Kralovec and John Buell, Beacon Press, 2001.

The Battle Over Homework: Common Ground for Administrators, Teachers, and Parents by Harris M. Cooper, Corwin Press, 2001.

Seven Steps to Homework Success: A Family Guide to Solving Common Homework Problems by Sydney Zentall and Sam Goldstein, Specialty Press, 1998.

Homes Nearby

Homes for rent and sale near schools

Why your neighborhood school closes for good – and what to do when it does

What should I write my college essay about?

What the #%@!& should I write about in my college essay?

How longer recess fuels child development

How longer recess fuels stronger child development

Yes! Sign me up for updates relevant to my child's grade.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up!

Server Issue: Please try again later. Sorry for the inconvenience

Homework – Top 3 Pros and Cons

Pro/Con Arguments | Discussion Questions | Take Action | Sources | More Debates

From dioramas to book reports, from algebraic word problems to research projects, whether students should be given homework, as well as the type and amount of homework, has been debated for over a century. [ 1 ]

While we are unsure who invented homework, we do know that the word “homework” dates back to ancient Rome. Pliny the Younger asked his followers to practice their speeches at home. Memorization exercises as homework continued through the Middle Ages and Enlightenment by monks and other scholars. [ 45 ]

In the 19th century, German students of the Volksschulen or “People’s Schools” were given assignments to complete outside of the school day. This concept of homework quickly spread across Europe and was brought to the United States by Horace Mann , who encountered the idea in Prussia. [ 45 ]

In the early 1900s, progressive education theorists, championed by the magazine Ladies’ Home Journal , decried homework’s negative impact on children’s physical and mental health, leading California to ban homework for students under 15 from 1901 until 1917. In the 1930s, homework was portrayed as child labor, which was newly illegal, but the prevailing argument was that kids needed time to do household chores. [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 45 ] [ 46 ]

Public opinion swayed again in favor of homework in the 1950s due to concerns about keeping up with the Soviet Union’s technological advances during the Cold War . And, in 1986, the US government included homework as an educational quality boosting tool. [ 3 ] [ 45 ]

A 2014 study found kindergarteners to fifth graders averaged 2.9 hours of homework per week, sixth to eighth graders 3.2 hours per teacher, and ninth to twelfth graders 3.5 hours per teacher. A 2014-2019 study found that teens spent about an hour a day on homework. [ 4 ] [ 44 ]

Beginning in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic complicated the very idea of homework as students were schooling remotely and many were doing all school work from home. Washington Post journalist Valerie Strauss asked, “Does homework work when kids are learning all day at home?” While students were mostly back in school buildings in fall 2021, the question remains of how effective homework is as an educational tool. [ 47 ]

Is Homework Beneficial?

Pro 1 Homework improves student achievement. Studies have shown that homework improved student achievement in terms of improved grades, test results, and the likelihood to attend college. Research published in the High School Journal indicated that students who spent between 31 and 90 minutes each day on homework “scored about 40 points higher on the SAT-Mathematics subtest than their peers, who reported spending no time on homework each day, on average.” [ 6 ] Students in classes that were assigned homework outperformed 69% of students who didn’t have homework on both standardized tests and grades. A majority of studies on homework’s impact – 64% in one meta-study and 72% in another – showed that take-home assignments were effective at improving academic achievement. [ 7 ] [ 8 ] Research by the Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) concluded that increased homework led to better GPAs and higher probability of college attendance for high school boys. In fact, boys who attended college did more than three hours of additional homework per week in high school. [ 10 ] Read More

Pro 2 Homework helps to reinforce classroom learning, while developing good study habits and life skills. Students typically retain only 50% of the information teachers provide in class, and they need to apply that information in order to truly learn it. Abby Freireich and Brian Platzer, co-founders of Teachers Who Tutor NYC, explained, “at-home assignments help students learn the material taught in class. Students require independent practice to internalize new concepts… [And] these assignments can provide valuable data for teachers about how well students understand the curriculum.” [ 11 ] [ 49 ] Elementary school students who were taught “strategies to organize and complete homework,” such as prioritizing homework activities, collecting study materials, note-taking, and following directions, showed increased grades and more positive comments on report cards. [ 17 ] Research by the City University of New York noted that “students who engage in self-regulatory processes while completing homework,” such as goal-setting, time management, and remaining focused, “are generally more motivated and are higher achievers than those who do not use these processes.” [ 18 ] Homework also helps students develop key skills that they’ll use throughout their lives: accountability, autonomy, discipline, time management, self-direction, critical thinking, and independent problem-solving. Freireich and Platzer noted that “homework helps students acquire the skills needed to plan, organize, and complete their work.” [ 12 ] [ 13 ] [ 14 ] [ 15 ] [ 49 ] Read More

Pro 3 Homework allows parents to be involved with children’s learning. Thanks to take-home assignments, parents are able to track what their children are learning at school as well as their academic strengths and weaknesses. [ 12 ] Data from a nationwide sample of elementary school students show that parental involvement in homework can improve class performance, especially among economically disadvantaged African-American and Hispanic students. [ 20 ] Research from Johns Hopkins University found that an interactive homework process known as TIPS (Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork) improves student achievement: “Students in the TIPS group earned significantly higher report card grades after 18 weeks (1 TIPS assignment per week) than did non-TIPS students.” [ 21 ] Homework can also help clue parents in to the existence of any learning disabilities their children may have, allowing them to get help and adjust learning strategies as needed. Duke University Professor Harris Cooper noted, “Two parents once told me they refused to believe their child had a learning disability until homework revealed it to them.” [ 12 ] Read More

Con 1 Too much homework can be harmful. A poll of California high school students found that 59% thought they had too much homework. 82% of respondents said that they were “often or always stressed by schoolwork.” High-achieving high school students said too much homework leads to sleep deprivation and other health problems such as headaches, exhaustion, weight loss, and stomach problems. [ 24 ] [ 28 ] [ 29 ] Alfie Kohn, an education and parenting expert, said, “Kids should have a chance to just be kids… it’s absurd to insist that children must be engaged in constructive activities right up until their heads hit the pillow.” [ 27 ] Emmy Kang, a mental health counselor, explained, “More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies.” [ 48 ] Excessive homework can also lead to cheating: 90% of middle school students and 67% of high school students admit to copying someone else’s homework, and 43% of college students engaged in “unauthorized collaboration” on out-of-class assignments. Even parents take shortcuts on homework: 43% of those surveyed admitted to having completed a child’s assignment for them. [ 30 ] [ 31 ] [ 32 ] Read More

Con 2 Homework exacerbates the digital divide or homework gap. Kiara Taylor, financial expert, defined the digital divide as “the gap between demographics and regions that have access to modern information and communications technology and those that don’t. Though the term now encompasses the technical and financial ability to utilize available technology—along with access (or a lack of access) to the Internet—the gap it refers to is constantly shifting with the development of technology.” For students, this is often called the homework gap. [ 50 ] [ 51 ] 30% (about 15 to 16 million) public school students either did not have an adequate internet connection or an appropriate device, or both, for distance learning. Completing homework for these students is more complicated (having to find a safe place with an internet connection, or borrowing a laptop, for example) or impossible. [ 51 ] A Hispanic Heritage Foundation study found that 96.5% of students across the country needed to use the internet for homework, and nearly half reported they were sometimes unable to complete their homework due to lack of access to the internet or a computer, which often resulted in lower grades. [ 37 ] [ 38 ] One study concluded that homework increases social inequality because it “potentially serves as a mechanism to further advantage those students who already experience some privilege in the school system while further disadvantaging those who may already be in a marginalized position.” [ 39 ] Read More

Con 3 Homework does not help younger students, and may not help high school students. We’ve known for a while that homework does not help elementary students. A 2006 study found that “homework had no association with achievement gains” when measured by standardized tests results or grades. [ 7 ] Fourth grade students who did no homework got roughly the same score on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) math exam as those who did 30 minutes of homework a night. Students who did 45 minutes or more of homework a night actually did worse. [ 41 ] Temple University professor Kathryn Hirsh-Pasek said that homework is not the most effective tool for young learners to apply new information: “They’re learning way more important skills when they’re not doing their homework.” [ 42 ] In fact, homework may not be helpful at the high school level either. Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth, stated, “I interviewed high school teachers who completely stopped giving homework and there was no downside, it was all upside.” He explains, “just because the same kids who get more homework do a little better on tests, doesn’t mean the homework made that happen.” [ 52 ] Read More

Discussion Questions

1. Is homework beneficial? Consider the study data, your personal experience, and other types of information. Explain your answer(s).

2. If homework were banned, what other educational strategies would help students learn classroom material? Explain your answer(s).

3. How has homework been helpful to you personally? How has homework been unhelpful to you personally? Make carefully considered lists for both sides.

Take Action

1. Examine an argument in favor of quality homework assignments from Janine Bempechat.

2. Explore Oxford Learning’s infographic on the effects of homework on students.

3. Consider Joseph Lathan’s argument that homework promotes inequality .

4. Consider how you felt about the issue before reading this article. After reading the pros and cons on this topic, has your thinking changed? If so, how? List two to three ways. If your thoughts have not changed, list two to three ways your better understanding of the “other side of the issue” now helps you better argue your position.

5. Push for the position and policies you support by writing US national senators and representatives .

| 1. | Tom Loveless, “Homework in America: Part II of the 2014 Brown Center Report of American Education,” brookings.edu, Mar. 18, 2014 | |

| 2. | Edward Bok, “A National Crime at the Feet of American Parents,” , Jan. 1900 | |

| 3. | Tim Walker, “The Great Homework Debate: What’s Getting Lost in the Hype,” neatoday.org, Sep. 23, 2015 | |

| 4. | University of Phoenix College of Education, “Homework Anxiety: Survey Reveals How Much Homework K-12 Students Are Assigned and Why Teachers Deem It Beneficial,” phoenix.edu, Feb. 24, 2014 | |

| 5. | Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), “PISA in Focus No. 46: Does Homework Perpetuate Inequities in Education?,” oecd.org, Dec. 2014 | |

| 6. | Adam V. Maltese, Robert H. Tai, and Xitao Fan, “When is Homework Worth the Time?: Evaluating the Association between Homework and Achievement in High School Science and Math,” , 2012 | |

| 7. | Harris Cooper, Jorgianne Civey Robinson, and Erika A. Patall, “Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement? A Synthesis of Researcher, 1987-2003,” , 2006 | |

| 8. | Gökhan Bas, Cihad Sentürk, and Fatih Mehmet Cigerci, “Homework and Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analytic Review of Research,” , 2017 | |

| 9. | Huiyong Fan, Jianzhong Xu, Zhihui Cai, Jinbo He, and Xitao Fan, “Homework and Students’ Achievement in Math and Science: A 30-Year Meta-Analysis, 1986-2015,” , 2017 | |

| 10. | Charlene Marie Kalenkoski and Sabrina Wulff Pabilonia, “Does High School Homework Increase Academic Achievement?,” iza.og, Apr. 2014 | |

| 11. | Ron Kurtus, “Purpose of Homework,” school-for-champions.com, July 8, 2012 | |

| 12. | Harris Cooper, “Yes, Teachers Should Give Homework – The Benefits Are Many,” newsobserver.com, Sep. 2, 2016 | |

| 13. | Tammi A. Minke, “Types of Homework and Their Effect on Student Achievement,” repository.stcloudstate.edu, 2017 | |

| 14. | LakkshyaEducation.com, “How Does Homework Help Students: Suggestions From Experts,” LakkshyaEducation.com (accessed Aug. 29, 2018) | |

| 15. | University of Montreal, “Do Kids Benefit from Homework?,” teaching.monster.com (accessed Aug. 30, 2018) | |

| 16. | Glenda Faye Pryor-Johnson, “Why Homework Is Actually Good for Kids,” memphisparent.com, Feb. 1, 2012 | |

| 17. | Joan M. Shepard, “Developing Responsibility for Completing and Handing in Daily Homework Assignments for Students in Grades Three, Four, and Five,” eric.ed.gov, 1999 | |

| 18. | Darshanand Ramdass and Barry J. Zimmerman, “Developing Self-Regulation Skills: The Important Role of Homework,” , 2011 | |

| 19. | US Department of Education, “Let’s Do Homework!,” ed.gov (accessed Aug. 29, 2018) | |

| 20. | Loretta Waldman, “Sociologist Upends Notions about Parental Help with Homework,” phys.org, Apr. 12, 2014 | |

| 21. | Frances L. Van Voorhis, “Reflecting on the Homework Ritual: Assignments and Designs,” , June 2010 | |

| 22. | Roel J. F. J. Aries and Sofie J. Cabus, “Parental Homework Involvement Improves Test Scores? A Review of the Literature,” , June 2015 | |

| 23. | Jamie Ballard, “40% of People Say Elementary School Students Have Too Much Homework,” yougov.com, July 31, 2018 | |

| 24. | Stanford University, “Stanford Survey of Adolescent School Experiences Report: Mira Costa High School, Winter 2017,” stanford.edu, 2017 | |

| 25. | Cathy Vatterott, “Rethinking Homework: Best Practices That Support Diverse Needs,” ascd.org, 2009 | |

| 26. | End the Race, “Homework: You Can Make a Difference,” racetonowhere.com (accessed Aug. 24, 2018) | |

| 27. | Elissa Strauss, “Opinion: Your Kid Is Right, Homework Is Pointless. Here’s What You Should Do Instead.,” cnn.com, Jan. 28, 2020 | |

| 28. | Jeanne Fratello, “Survey: Homework Is Biggest Source of Stress for Mira Costa Students,” digmb.com, Dec. 15, 2017 | |

| 29. | Clifton B. Parker, “Stanford Research Shows Pitfalls of Homework,” stanford.edu, Mar. 10, 2014 | |

| 30. | AdCouncil, “Cheating Is a Personal Foul: Academic Cheating Background,” glass-castle.com (accessed Aug. 16, 2018) | |

| 31. | Jeffrey R. Young, “High-Tech Cheating Abounds, and Professors Bear Some Blame,” chronicle.com, Mar. 28, 2010 | |

| 32. | Robin McClure, “Do You Do Your Child’s Homework?,” verywellfamily.com, Mar. 14, 2018 | |

| 33. | Robert M. Pressman, David B. Sugarman, Melissa L. Nemon, Jennifer, Desjarlais, Judith A. Owens, and Allison Schettini-Evans, “Homework and Family Stress: With Consideration of Parents’ Self Confidence, Educational Level, and Cultural Background,” , 2015 | |

| 34. | Heather Koball and Yang Jiang, “Basic Facts about Low-Income Children,” nccp.org, Jan. 2018 | |

| 35. | Meagan McGovern, “Homework Is for Rich Kids,” huffingtonpost.com, Sep. 2, 2016 | |

| 36. | H. Richard Milner IV, “Not All Students Have Access to Homework Help,” nytimes.com, Nov. 13, 2014 | |

| 37. | Claire McLaughlin, “The Homework Gap: The ‘Cruelest Part of the Digital Divide’,” neatoday.org, Apr. 20, 2016 | |

| 38. | Doug Levin, “This Evening’s Homework Requires the Use of the Internet,” edtechstrategies.com, May 1, 2015 | |

| 39. | Amy Lutz and Lakshmi Jayaram, “Getting the Homework Done: Social Class and Parents’ Relationship to Homework,” , June 2015 | |

| 40. | Sandra L. Hofferth and John F. Sandberg, “How American Children Spend Their Time,” psc.isr.umich.edu, Apr. 17, 2000 | |

| 41. | Alfie Kohn, “Does Homework Improve Learning?,” alfiekohn.org, 2006 | |

| 42. | Patrick A. Coleman, “Elementary School Homework Probably Isn’t Good for Kids,” fatherly.com, Feb. 8, 2018 | |

| 43. | Valerie Strauss, “Why This Superintendent Is Banning Homework – and Asking Kids to Read Instead,” washingtonpost.com, July 17, 2017 | |

| 44. | Pew Research Center, “The Way U.S. Teens Spend Their Time Is Changing, but Differences between Boys and Girls Persist,” pewresearch.org, Feb. 20, 2019 | |

| 45. | ThroughEducation, “The History of Homework: Why Was It Invented and Who Was behind It?,” , Feb. 14, 2020 | |

| 46. | History, “Why Homework Was Banned,” (accessed Feb. 24, 2022) | |

| 47. | Valerie Strauss, “Does Homework Work When Kids Are Learning All Day at Home?,” , Sep. 2, 2020 | |

| 48. | Sara M Moniuszko, “Is It Time to Get Rid of Homework? Mental Health Experts Weigh In,” , Aug. 17, 2021 | |

| 49. | Abby Freireich and Brian Platzer, “The Worsening Homework Problem,” , Apr. 13, 2021 | |

| 50. | Kiara Taylor, “Digital Divide,” , Feb. 12, 2022 | |

| 51. | Marguerite Reardon, “The Digital Divide Has Left Millions of School Kids Behind,” , May 5, 2021 | |

| 52. | Rachel Paula Abrahamson, “Why More and More Teachers Are Joining the Anti-Homework Movement,” , Sep. 10, 2021 |

More School Debate Topics

Should K-12 Students Dissect Animals in Science Classrooms? – Proponents say dissecting real animals is a better learning experience. Opponents say the practice is bad for the environment.

Should Students Have to Wear School Uniforms? – Proponents say uniforms may increase student safety. Opponents say uniforms restrict expression.

Should Corporal Punishment Be Used in K-12 Schools? – Proponents say corporal punishment is an appropriate discipline. Opponents say it inflicts long-lasting physical and mental harm on students.

ProCon/Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. 325 N. LaSalle Street, Suite 200 Chicago, Illinois 60654 USA

Natalie Leppard Managing Editor [email protected]

© 2023 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved

- Social Media

- Death Penalty

- School Uniforms

- Video Games

- Animal Testing

- Gun Control

- Banned Books

- Teachers’ Corner

Cite This Page

ProCon.org is the institutional or organization author for all ProCon.org pages. Proper citation depends on your preferred or required style manual. Below are the proper citations for this page according to four style manuals (in alphabetical order): the Modern Language Association Style Manual (MLA), the Chicago Manual of Style (Chicago), the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA), and Kate Turabian's A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, and Dissertations (Turabian). Here are the proper bibliographic citations for this page according to four style manuals (in alphabetical order):

[Editor's Note: The APA citation style requires double spacing within entries.]

[Editor’s Note: The MLA citation style requires double spacing within entries.]

How Much Homework Is Too Much?

Are schools assigning too much homework.

Posted October 19, 2011

Timothy, a fifth grader, spends up to thirteen hours a day hunched over a desk at school or at home, studying and doing homework. Should his parents feel proud? Now imagine, for comparison's sake, Timothy spending thirteen hours a day hunched over a sewing machine instead of a desk.

Parents have the right to complain when schools assign too much homework but they often don't know how to do so effectively.

Drowning in Homework ( an excerpt from Chapter 8 of The Squeaky Wheel )

I first met Timothy, a quiet, overweight eleven-year-old boy, when his mother brought him to therapy to discuss his slipping grades. A few minutes with Timothy were enough to confirm that his mood, self-esteem , and general happiness were slipping right along with them. Timothy attended one of the top private schools in Manhattan, an environment in which declining grades were no idle matter.

I asked about Timothy's typical day. He awoke every morning at six thirty so he could get to school by eight and arrived home around four thirty each afternoon. He then had a quick snack, followed by either a piano lesson or his math tutor, depending on the day. He had dinner at seven p.m., after which he sat down to do homework for two to three hours a night. Quickly doing the math in my head, I calculated that Timothy spent an average of thirteen hours a day hunched over a writing desk. His situation is not atypical. Spending that many hours studying is the only way Timothy can keep up and stay afloat academically.

But what if, for comparison's sake, we imagined Timothy spending thirteen hours a day hunched over a sewing machine instead of a desk. We would immediately be aghast at the inhumanity because children are horribly mistreated in such "sweatshops." Timothy is far from being mistreated, but the mountain of homework he faces daily results in a similar consequence- he too is being robbed of his childhood.

Timothy's academics leave him virtually no time to do anything he truly enjoys, such as playing video games, movies, or board games with his friends. During the week he never plays outside and never has indoor play dates or opportunities to socialize with friends. On weekends, Timothy's days are often devoted to studying for tests, working on special school projects, or arguing with his mother about studying for tests and working on special school projects.

By the fourth and fifth grade and certainly in middle school, many of our children have hours of homework, test preparation, project writing, or research to do every night, all in addition to the eight hours or more they have to spend in school. Yet study after study has shown that homework has little to do with achievement in elementary school and is only marginally related to achievement in middle school .

Play, however, is a crucial component of healthy child development . It affects children's creativity , their social skills, and even their brain development. The absence of play, physical exercise, and free-form social interaction takes a serious toll on many children. It can also have significant health implications as is evidenced by our current epidemic of childhood obesity, sleep deprivation, low self- esteem, and depression .

A far stronger predictor than homework of academic achievement for kids aged three to twelve is having regular family meals. Family meals allow parents to check in, to demonstrate caring and involvement, to provide supervision, and to offer support. The more family meals can be worked into the schedule, the better, especially for preteens. The frequency of family meals has also been shown to help with disordered eating behaviors in adolescents.

Experts in the field recommend children have no more than ten minutes of homework per day per grade level. As a fifth- grader, Timothy should have no more than fifty minutes a day of homework (instead of three times that amount). Having an extra two hours an evening to play, relax, or see a friend would constitute a huge bump in any child's quality of life.

So what can we do if our child is getting too much homework?

1. Complain to the teachers and the school. Most parents are unaware that excessive homework contributes so little to their child's academic achievement.

2. Educate your child's teacher and principal about the homework research-they are often equally unaware of the facts and teachers of younger children (K-4) often make changes as a result.

3. Create allies within the system by speaking with other parents and banding together to address the issue with the school.

You might also like: Is Excessive Homework in Private Schools a Customer Service Issue?

View my short and quite personal TED talk about Psychological Health here:

Check out my new book, Emotional First Aid: Practical Strategies for Treating Failure, Rejection, Guilt and Other Evreyday Psychological Injuries (Hudson Street Press).

Click here to join my mailing list

Copyright 2011 Guy Winch

Follow me on Twitter @GuyWinch

Guy Winch, Ph.D. , is a licensed psychologist and author of Emotional First Aid: Healing Rejection, Guilt, Failure, and Other Everyday Hurts.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC