- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

How to Make a “Good” Presentation “Great”

- Guy Kawasaki

Remember: Less is more.

A strong presentation is so much more than information pasted onto a series of slides with fancy backgrounds. Whether you’re pitching an idea, reporting market research, or sharing something else, a great presentation can give you a competitive advantage, and be a powerful tool when aiming to persuade, educate, or inspire others. Here are some unique elements that make a presentation stand out.

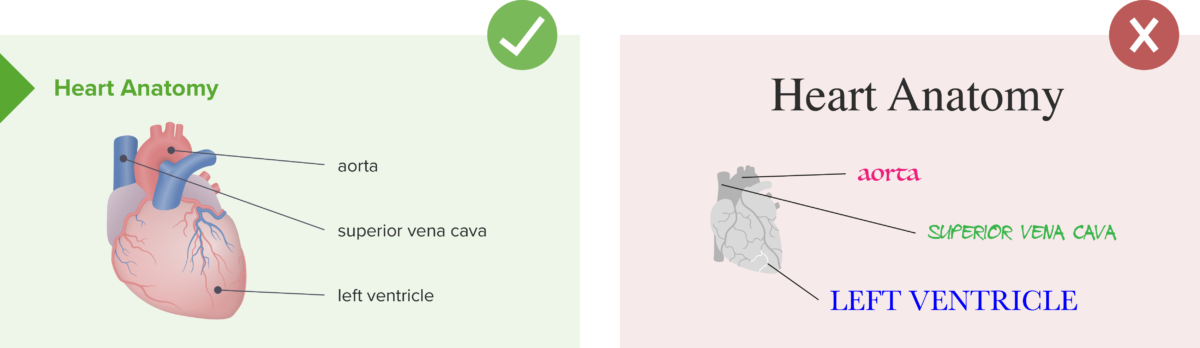

- Fonts: Sans Serif fonts such as Helvetica or Arial are preferred for their clean lines, which make them easy to digest at various sizes and distances. Limit the number of font styles to two: one for headings and another for body text, to avoid visual confusion or distractions.

- Colors: Colors can evoke emotions and highlight critical points, but their overuse can lead to a cluttered and confusing presentation. A limited palette of two to three main colors, complemented by a simple background, can help you draw attention to key elements without overwhelming the audience.

- Pictures: Pictures can communicate complex ideas quickly and memorably but choosing the right images is key. Images or pictures should be big (perhaps 20-25% of the page), bold, and have a clear purpose that complements the slide’s text.

- Layout: Don’t overcrowd your slides with too much information. When in doubt, adhere to the principle of simplicity, and aim for a clean and uncluttered layout with plenty of white space around text and images. Think phrases and bullets, not sentences.

As an intern or early career professional, chances are that you’ll be tasked with making or giving a presentation in the near future. Whether you’re pitching an idea, reporting market research, or sharing something else, a great presentation can give you a competitive advantage, and be a powerful tool when aiming to persuade, educate, or inspire others.

- Guy Kawasaki is the chief evangelist at Canva and was the former chief evangelist at Apple. Guy is the author of 16 books including Think Remarkable : 9 Paths to Transform Your Life and Make a Difference.

Partner Center

Mar 31 Digest #161: Guide to Effective Presentations

By Cindy Nebel

This week I was having a conversation with Brian Selman , Assistant Director of Coaching and Player Development for the Pittsburgh Pirates, about how learning science could make the conversations with his fellow coaches and players more effective. He asked if we had any resources on our website about making presentations more effective and the answer was, well… kind of. So today I’m scouring the internet and providing you (and Brian) with a few resources that utilize the learning science principles we advocate to talk about effective presentations of material.

1) GUEST POST: Make the Presentation Count by Anna Navin Young, @AnnaNavinYoung

First up, the one post that we have on our website that most directly talks about effective presentations. This post focuses on designing effective powerpoint slides using what we know about multimedia learning.

Image from Pixabay

2) Improving Presentations with Learning Science by the Center for Innovation in Legal Education

This is a really nice summary of the science behind effective presentations. It also focuses on the design of powerpoint slides, but includes a breakdown of some of the theory behind the principles and concrete applications.

3) Scientific Presenting: Using Evidence-Based Classroom Practices to Deliver Effective Conference Presentations by Lisa Corwin ( @lcorwin202 ), Amy Prunuske ( @aprunuske ), and Shannon Seidel (from @PLUNEWS )

This article is focused on presenting at scientific conferences, but I think these principles are broadly applied to presenting anything to anyone. They include principles like promoting engagement and equity, assessment, knowing your audience, and backward design. But the best part about this is that they include SO MANY examples of ways you can engage adults in activities during presentations.

4) A Scientist’s Guide to Making Successful Presentations to High School Students by Gloria Seelman of the NIH Office of Science Education

This resource really is for science teachers, but again, the lessons included could and should be considered by anyone hoping to present an effective presentation. Consider your audience and goals, engage the learners, but also while presenting, consider wait time and equity issues. Included here are also some excellent off the shelf classroom tools for science educators.

5) The Science of Effective Presentations by Prezi, @prezi

While I am not specifically endorsing Prezi as a medium here, this document walks through some of the research specifically around the effectiveness of storytelling to create a compelling and memorable presentation. There are some visually appealing examples provided as well as ideas for how to deliver the story.

In addition to the above, we have a two blogs about creating effective instructional videos ( here and here ) that talk about some of the same principles as the above resources and could be useful!

From time to time, we pick a theme and provide a curated list of links. If you have a theme suggestion, please don’t hesitate to contact us! Occasionally we publish a guest digest, and If you'd like to propose a guest digest click here . Our 5 most recent digests can be found here:

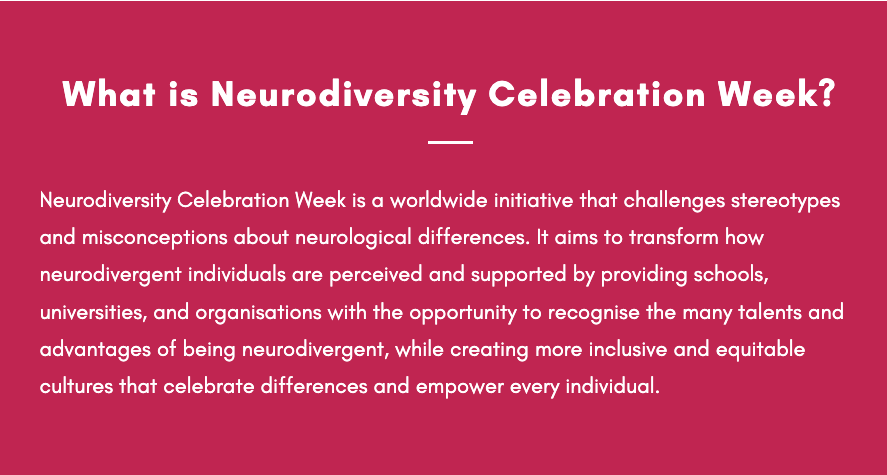

Digest #156: Learning (More) About Neurodiversity

Digest #157: Exam Preparation Tips

Digest #158: Mental Health and Wellbeing in Education

Digest #159: The Digital Divide

Digest #160: Neurodiversity Celebration Week

Apr 7 GUEST POST: Matching instruction to preferred learning styles does not raise achievement

Mar 24 Digest #160: Neurodiversity Celebration Week

Loading metrics

Open Access

Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Biomedical Engineering and the Center for Public Health Genomics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, United States of America

- Kristen M. Naegle

Published: December 2, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554

- Reader Comments

Citation: Naegle KM (2021) Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides. PLoS Comput Biol 17(12): e1009554. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554

Copyright: © 2021 Kristen M. Naegle. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The author received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The author has declared no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The “presentation slide” is the building block of all academic presentations, whether they are journal clubs, thesis committee meetings, short conference talks, or hour-long seminars. A slide is a single page projected on a screen, usually built on the premise of a title, body, and figures or tables and includes both what is shown and what is spoken about that slide. Multiple slides are strung together to tell the larger story of the presentation. While there have been excellent 10 simple rules on giving entire presentations [ 1 , 2 ], there was an absence in the fine details of how to design a slide for optimal effect—such as the design elements that allow slides to convey meaningful information, to keep the audience engaged and informed, and to deliver the information intended and in the time frame allowed. As all research presentations seek to teach, effective slide design borrows from the same principles as effective teaching, including the consideration of cognitive processing your audience is relying on to organize, process, and retain information. This is written for anyone who needs to prepare slides from any length scale and for most purposes of conveying research to broad audiences. The rules are broken into 3 primary areas. Rules 1 to 5 are about optimizing the scope of each slide. Rules 6 to 8 are about principles around designing elements of the slide. Rules 9 to 10 are about preparing for your presentation, with the slides as the central focus of that preparation.

Rule 1: Include only one idea per slide

Each slide should have one central objective to deliver—the main idea or question [ 3 – 5 ]. Often, this means breaking complex ideas down into manageable pieces (see Fig 1 , where “background” information has been split into 2 key concepts). In another example, if you are presenting a complex computational approach in a large flow diagram, introduce it in smaller units, building it up until you finish with the entire diagram. The progressive buildup of complex information means that audiences are prepared to understand the whole picture, once you have dedicated time to each of the parts. You can accomplish the buildup of components in several ways—for example, using presentation software to cover/uncover information. Personally, I choose to create separate slides for each piece of information content I introduce—where the final slide has the entire diagram, and I use cropping or a cover on duplicated slides that come before to hide what I’m not yet ready to include. I use this method in order to ensure that each slide in my deck truly presents one specific idea (the new content) and the amount of the new information on that slide can be described in 1 minute (Rule 2), but it comes with the trade-off—a change to the format of one of the slides in the series often means changes to all slides.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Top left: A background slide that describes the background material on a project from my lab. The slide was created using a PowerPoint Design Template, which had to be modified to increase default text sizes for this figure (i.e., the default text sizes are even worse than shown here). Bottom row: The 2 new slides that break up the content into 2 explicit ideas about the background, using a central graphic. In the first slide, the graphic is an explicit example of the SH2 domain of PI3-kinase interacting with a phosphorylation site (Y754) on the PDGFR to describe the important details of what an SH2 domain and phosphotyrosine ligand are and how they interact. I use that same graphic in the second slide to generalize all binding events and include redundant text to drive home the central message (a lot of possible interactions might occur in the human proteome, more than we can currently measure). Top right highlights which rules were used to move from the original slide to the new slide. Specific changes as highlighted by Rule 7 include increasing contrast by changing the background color, increasing font size, changing to sans serif fonts, and removing all capital text and underlining (using bold to draw attention). PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554.g001

Rule 2: Spend only 1 minute per slide

When you present your slide in the talk, it should take 1 minute or less to discuss. This rule is really helpful for planning purposes—a 20-minute presentation should have somewhere around 20 slides. Also, frequently giving your audience new information to feast on helps keep them engaged. During practice, if you find yourself spending more than a minute on a slide, there’s too much for that one slide—it’s time to break up the content into multiple slides or even remove information that is not wholly central to the story you are trying to tell. Reduce, reduce, reduce, until you get to a single message, clearly described, which takes less than 1 minute to present.

Rule 3: Make use of your heading

When each slide conveys only one message, use the heading of that slide to write exactly the message you are trying to deliver. Instead of titling the slide “Results,” try “CTNND1 is central to metastasis” or “False-positive rates are highly sample specific.” Use this landmark signpost to ensure that all the content on that slide is related exactly to the heading and only the heading. Think of the slide heading as the introductory or concluding sentence of a paragraph and the slide content the rest of the paragraph that supports the main point of the paragraph. An audience member should be able to follow along with you in the “paragraph” and come to the same conclusion sentence as your header at the end of the slide.

Rule 4: Include only essential points

While you are speaking, audience members’ eyes and minds will be wandering over your slide. If you have a comment, detail, or figure on a slide, have a plan to explicitly identify and talk about it. If you don’t think it’s important enough to spend time on, then don’t have it on your slide. This is especially important when faculty are present. I often tell students that thesis committee members are like cats: If you put a shiny bauble in front of them, they’ll go after it. Be sure to only put the shiny baubles on slides that you want them to focus on. Putting together a thesis meeting for only faculty is really an exercise in herding cats (if you have cats, you know this is no easy feat). Clear and concise slide design will go a long way in helping you corral those easily distracted faculty members.

Rule 5: Give credit, where credit is due

An exception to Rule 4 is to include proper citations or references to work on your slide. When adding citations, names of other researchers, or other types of credit, use a consistent style and method for adding this information to your slides. Your audience will then be able to easily partition this information from the other content. A common mistake people make is to think “I’ll add that reference later,” but I highly recommend you put the proper reference on the slide at the time you make it, before you forget where it came from. Finally, in certain kinds of presentations, credits can make it clear who did the work. For the faculty members heading labs, it is an effective way to connect your audience with the personnel in the lab who did the work, which is a great career booster for that person. For graduate students, it is an effective way to delineate your contribution to the work, especially in meetings where the goal is to establish your credentials for meeting the rigors of a PhD checkpoint.

Rule 6: Use graphics effectively

As a rule, you should almost never have slides that only contain text. Build your slides around good visualizations. It is a visual presentation after all, and as they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. However, on the flip side, don’t muddy the point of the slide by putting too many complex graphics on a single slide. A multipanel figure that you might include in a manuscript should often be broken into 1 panel per slide (see Rule 1 ). One way to ensure that you use the graphics effectively is to make a point to introduce the figure and its elements to the audience verbally, especially for data figures. For example, you might say the following: “This graph here shows the measured false-positive rate for an experiment and each point is a replicate of the experiment, the graph demonstrates …” If you have put too much on one slide to present in 1 minute (see Rule 2 ), then the complexity or number of the visualizations is too much for just one slide.

Rule 7: Design to avoid cognitive overload

The type of slide elements, the number of them, and how you present them all impact the ability for the audience to intake, organize, and remember the content. For example, a frequent mistake in slide design is to include full sentences, but reading and verbal processing use the same cognitive channels—therefore, an audience member can either read the slide, listen to you, or do some part of both (each poorly), as a result of cognitive overload [ 4 ]. The visual channel is separate, allowing images/videos to be processed with auditory information without cognitive overload [ 6 ] (Rule 6). As presentations are an exercise in listening, and not reading, do what you can to optimize the ability of the audience to listen. Use words sparingly as “guide posts” to you and the audience about major points of the slide. In fact, you can add short text fragments, redundant with the verbal component of the presentation, which has been shown to improve retention [ 7 ] (see Fig 1 for an example of redundant text that avoids cognitive overload). Be careful in the selection of a slide template to minimize accidentally adding elements that the audience must process, but are unimportant. David JP Phillips argues (and effectively demonstrates in his TEDx talk [ 5 ]) that the human brain can easily interpret 6 elements and more than that requires a 500% increase in human cognition load—so keep the total number of elements on the slide to 6 or less. Finally, in addition to the use of short text, white space, and the effective use of graphics/images, you can improve ease of cognitive processing further by considering color choices and font type and size. Here are a few suggestions for improving the experience for your audience, highlighting the importance of these elements for some specific groups:

- Use high contrast colors and simple backgrounds with low to no color—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment.

- Use sans serif fonts and large font sizes (including figure legends), avoid italics, underlining (use bold font instead for emphasis), and all capital letters—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment [ 8 ].

- Use color combinations and palettes that can be understood by those with different forms of color blindness [ 9 ]. There are excellent tools available to identify colors to use and ways to simulate your presentation or figures as they might be seen by a person with color blindness (easily found by a web search).

- In this increasing world of virtual presentation tools, consider practicing your talk with a closed captioning system capture your words. Use this to identify how to improve your speaking pace, volume, and annunciation to improve understanding by all members of your audience, but especially those with a hearing impairment.

Rule 8: Design the slide so that a distracted person gets the main takeaway

It is very difficult to stay focused on a presentation, especially if it is long or if it is part of a longer series of talks at a conference. Audience members may get distracted by an important email, or they may start dreaming of lunch. So, it’s important to look at your slide and ask “If they heard nothing I said, will they understand the key concept of this slide?” The other rules are set up to help with this, including clarity of the single point of the slide (Rule 1), titling it with a major conclusion (Rule 3), and the use of figures (Rule 6) and short text redundant to your verbal description (Rule 7). However, with each slide, step back and ask whether its main conclusion is conveyed, even if someone didn’t hear your accompanying dialog. Importantly, ask if the information on the slide is at the right level of abstraction. For example, do you have too many details about the experiment, which hides the conclusion of the experiment (i.e., breaking Rule 1)? If you are worried about not having enough details, keep a slide at the end of your slide deck (after your conclusions and acknowledgments) with the more detailed information that you can refer to during a question and answer period.

Rule 9: Iteratively improve slide design through practice

Well-designed slides that follow the first 8 rules are intended to help you deliver the message you intend and in the amount of time you intend to deliver it in. The best way to ensure that you nailed slide design for your presentation is to practice, typically a lot. The most important aspects of practicing a new presentation, with an eye toward slide design, are the following 2 key points: (1) practice to ensure that you hit, each time through, the most important points (for example, the text guide posts you left yourself and the title of the slide); and (2) practice to ensure that as you conclude the end of one slide, it leads directly to the next slide. Slide transitions, what you say as you end one slide and begin the next, are important to keeping the flow of the “story.” Practice is when I discover that the order of my presentation is poor or that I left myself too few guideposts to remember what was coming next. Additionally, during practice, the most frequent things I have to improve relate to Rule 2 (the slide takes too long to present, usually because I broke Rule 1, and I’m delivering too much information for one slide), Rule 4 (I have a nonessential detail on the slide), and Rule 5 (I forgot to give a key reference). The very best type of practice is in front of an audience (for example, your lab or peers), where, with fresh perspectives, they can help you identify places for improving slide content, design, and connections across the entirety of your talk.

Rule 10: Design to mitigate the impact of technical disasters

The real presentation almost never goes as we planned in our heads or during our practice. Maybe the speaker before you went over time and now you need to adjust. Maybe the computer the organizer is having you use won’t show your video. Maybe your internet is poor on the day you are giving a virtual presentation at a conference. Technical problems are routinely part of the practice of sharing your work through presentations. Hence, you can design your slides to limit the impact certain kinds of technical disasters create and also prepare alternate approaches. Here are just a few examples of the preparation you can do that will take you a long way toward avoiding a complete fiasco:

- Save your presentation as a PDF—if the version of Keynote or PowerPoint on a host computer cause issues, you still have a functional copy that has a higher guarantee of compatibility.

- In using videos, create a backup slide with screen shots of key results. For example, if I have a video of cell migration, I’ll be sure to have a copy of the start and end of the video, in case the video doesn’t play. Even if the video worked, you can pause on this backup slide and take the time to highlight the key results in words if someone could not see or understand the video.

- Avoid animations, such as figures or text that flash/fly-in/etc. Surveys suggest that no one likes movement in presentations [ 3 , 4 ]. There is likely a cognitive underpinning to the almost universal distaste of pointless animations that relates to the idea proposed by Kosslyn and colleagues that animations are salient perceptual units that captures direct attention [ 4 ]. Although perceptual salience can be used to draw attention to and improve retention of specific points, if you use this approach for unnecessary/unimportant things (like animation of your bullet point text, fly-ins of figures, etc.), then you will distract your audience from the important content. Finally, animations cause additional processing burdens for people with visual impairments [ 10 ] and create opportunities for technical disasters if the software on the host system is not compatible with your planned animation.

Conclusions

These rules are just a start in creating more engaging presentations that increase audience retention of your material. However, there are wonderful resources on continuing on the journey of becoming an amazing public speaker, which includes understanding the psychology and neuroscience behind human perception and learning. For example, as highlighted in Rule 7, David JP Phillips has a wonderful TEDx talk on the subject [ 5 ], and “PowerPoint presentation flaws and failures: A psychological analysis,” by Kosslyn and colleagues is deeply detailed about a number of aspects of human cognition and presentation style [ 4 ]. There are many books on the topic, including the popular “Presentation Zen” by Garr Reynolds [ 11 ]. Finally, although briefly touched on here, the visualization of data is an entire topic of its own that is worth perfecting for both written and oral presentations of work, with fantastic resources like Edward Tufte’s “The Visual Display of Quantitative Information” [ 12 ] or the article “Visualization of Biomedical Data” by O’Donoghue and colleagues [ 13 ].

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the countless presenters, colleagues, students, and mentors from which I have learned a great deal from on effective presentations. Also, a thank you to the wonderful resources published by organizations on how to increase inclusivity. A special thanks to Dr. Jason Papin and Dr. Michael Guertin on early feedback of this editorial.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 3. Teaching VUC for Making Better PowerPoint Presentations. n.d. Available from: https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/making-better-powerpoint-presentations/#baddeley .

- 8. Creating a dyslexia friendly workplace. Dyslexia friendly style guide. nd. Available from: https://www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/advice/employers/creating-a-dyslexia-friendly-workplace/dyslexia-friendly-style-guide .

- 9. Cravit R. How to Use Color Blind Friendly Palettes to Make Your Charts Accessible. 2019. Available from: https://venngage.com/blog/color-blind-friendly-palette/ .

- 10. Making your conference presentation more accessible to blind and partially sighted people. n.d. Available from: https://vocaleyes.co.uk/services/resources/guidelines-for-making-your-conference-presentation-more-accessible-to-blind-and-partially-sighted-people/ .

- 11. Reynolds G. Presentation Zen: Simple Ideas on Presentation Design and Delivery. 2nd ed. New Riders Pub; 2011.

- 12. Tufte ER. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. 2nd ed. Graphics Press; 2001.

Like what you're reading?

The Science of Effective Presentations [E-book]

Get your team on prezi – watch this on demand video.

Chelsi Nakano June 07, 2016

Imagine for a moment that you have been tasked with delivering an important presentation at work—maybe it is a sales pitch to a key customer, a budget proposal for senior management, or a keynote conference talk in front of your peers. No matter what the topic, the goal of these kinds of presentations is the same: communicate a message that engages the audience, sticks in their minds, and persuades them to take action.

At Prezi, we are focused on building tools that help people give more effective presentations—and through that work, we’ve done a lot of research on what makes information engaging, memorable, and persuasive. We’ve gone digging through studies conducted by psychologists and neuroscientists to try to understand how audience’s brains work. We’ve distilled all this research into a comprehensive e-book, which we’re giving away for free. Download the book to learn:

- Why people’s brains are hardwired to respond to certain kinds of content

- How presenters can take advantage of psychology and biology to be more effective

- What science has to say about improving your presentations

Download the e-book.

You might also like

Prezi awards 2018: show us your best stuff, the storyteller’s edge: communication secrets to sell, lead, and grow, on-demand webinar: the big narrative — how to communicate a disruptive message, give your team the tools they need to engage, like what you’re reading join the mailing list..

- Prezi for Teams

- Top Presentations

The Science of Effective Presentations

Commercial psychologist Phillip Adcock and training expert Ian Callow offer some practical advice on how you can improve your own presentations.

Most of us agree that we have all sat through too many mind-numbingly boring presentations, so we decided to find out why. We wanted to find out whether PowerPoint really helps people convey their key messages or whether perhaps the opposite may be true in that it is actually reducing the effectiveness of what they are trying to say.

Use both spoken and visual communication – “Dual encoding”

Firstly, you need to understand how we as humans receive and process incoming information. Typically, we mentally encode visual and spoken information at the same time, but using different parts of the brain: this is known as dual encoding, and from a presenting and communications perspective, is a much more powerful way of ensuring that your key messages become firmly embedded into the brains of your audiences. In practical terms, what this means is that if you show a picture on screen and describe the image verbally, the audience takes on board and retains more of your communication.

Be careful – bullet points are not visuals

But beware! Bullet points on screen are definitely not effective devices for describing an image as they too have to be processed visually (like the image) and so any dual encoding is nullified.

Minimise the number of times you speak any word that appears on the screen

Another simple technique for improving your communication ability using PowerPoint is to challenge yourself to minimise the number of times you ever speak any word that appears on the screen at the same time. For a kick-off, the screen that you are showing to the audience should never, ever be something you read your script from. The screen content adds depth, value and context to the stuff coming out of your mouth, and, as the well-known saying goes, a picture paints a thousand words. By adopting this approach, you will rapidly improve the audience uptake and subsequent recall of what you are communicating to them.

Be prepared to accept feedback, both good and bad

A good presenter is always prepared to listen to the advice of others and, in particular, we strongly urge you to take the courageous step of developing a feedback loop. This could involve asking a friend or colleague to attend your presentation and to critique your content and performance objectively during a later review session.

Video-record your presentation

Alternatively, consider video-recording your performance and then self-reviewing your presentation. Scientists have identified that as much as 95% of what we do, we do with little or no conscious awareness. In other words, until you watch yourself present or have someone else do it for you, there is very little chance of you really knowing what you do well and what else you do not so well.

What is the one message you want the audience to remember?

Our next recommendation will sound like common sense, but we never cease to be amazed by the number of presenters who can’t answer the following question: “what is the one key message that you want the audience to leave your presentation with?”

What are the 7 supporting messages?

Incidentally, we also recommend identifying a maximum of 7 supporting messages that you want to embed in the brains of your audience. We also suggest you identify this information before you go to work designing your presentation. This way, you have a defined output and you can then structure your entire communication around it.

In our experience, many presenters seem intent on having a deck full of information that they are determined to shower the audience with in the vain hope that some of what they say will ‘stick’: spray and pray, as we call it.

Have you given the presentation enough time and attention?

Here is a simple but thought-provoking notion: Whatever you as a presenter are communicating, stop for a moment and consider the value of the information you are imparting. Then ask yourself, how much it would be worth investing in terms of optimising the way you deliver your messages. More often than not, the presentation and how you deliver it deserves more time, attention and investment that many currently give it.

Phillip Adcock and Ian Callow are co-authors of The Presenter’s Handbook: How to Give a Captivating Performance – Every Time! www.presentershandbook.com

Recommended Pages

I’m a firm believer in short and to the point. Let the audience create a good portion of the experience by engaging them whenever possible. It also makes it easier on the presenter.

What is the word science in the headline referring to? Are these advices somehow researched? Thanks

- All Templates

- Persuasive Speech Topics

- Informative

- Architecture

- Celebration

- Educational

- Engineering

- Food and Drink

- Subtle Waves Template

- Business world map

- Filmstrip with Countdown

- Blue Bubbles

- Corporate 2

- Vector flowers template

- Editable PowerPoint newspapers

- Hands Template

- Red blood cells slide

- Circles Template on white

- Maps of America

- Light Streaks Business Template

- Zen stones template

- Heartbeat Template

- Web icons template

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 19 October 2011

Effective presentations: tips for success

- Janet P Hafler 1

Nature Immunology volume 12 , pages 1021–1023 ( 2011 ) Cite this article

1418 Accesses

2 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Communication

Presentations are given in a variety of environments, and effective strategies can be used to improve a speaker's presenting skills.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Wilkerson, L. & Irby, D.M. Acad. Med. 73 , 387–396 (1998).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bing-You, R.G. & Hafler, J.P. J. Grad. Med. Education 1 , 100–103 (2009).

Article Google Scholar

Svinicki, M.D. & Wilkerson, L. in Extraordinary Learning in the Workplace. Faculty Development for Workplace Instructors (ed. Hafler, J.P.) 131–164 (Springer, The Netherlands, 2011).

Book Google Scholar

Mezirow, J.D. in Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning 1–247 (Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 1991).

Google Scholar

Dewey, J. in Experience and Nature 1–74 (Open Court, London, 1929).

Kolb, D.A. in Experience as the Source of Learning and Development 1–256 (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1984).

Entwistle, N., Skinner, D., Entwistle, D. & Orr, S. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 19 , 1–16 (2000).

Steinert, Y. & Snell, L. Med. Teach. 21 , 37–42 (1999).

Bligh, D. in What's the Use of Lectures? 1–56 (Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 2001).

McKeachie, W. in Teaching Tips: Strategies, Research, and Theory for College and University Teachers 11th edn. 22–34 (Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 2001).

Nilson, L. in Teaching at Its Best 3rd edn. 113–126 (Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 2010).

Irby, D.M., Ramsey, P.G., Gillmore, G.M. & Schaad, D. Acad. Med. 66 , 54–55 (1991).

Tufte, E. in The Cognitive Style of PowerPoint 1–22 (Graphics, Cheshire, Connecticut, 2003).

Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action 168–203 (Basic Books, New York, 1983).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Janet P. Hafler is in the Department of Pediatrics, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.,

Janet P Hafler

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Janet P Hafler .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Hafler, J. Effective presentations: tips for success. Nat Immunol 12 , 1021–1023 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.2119

Download citation

Published : 19 October 2011

Issue Date : November 2011

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.2119

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Module 13: Public Speaking on the Job

Effective presentations, learning objectives.

Identify key features of an effective presentation.

When you’re giving a presentation at work, you’re essentially giving an informative speech. Many of the strategies and principles discussed in Module 9: Informative Speech apply to the situation of presenting at work as well. We’ll review a few key areas below. It is also important to keep in mind, however, that the way you approach a presentation for work will differ significantly depending on the context. In the professional context, your presentation has a specific function; before you begin putting it together, you need to find out as many details as possible about the function your presentation will be performing. Are you speaking to coworkers? Potential clients? Community leaders? Other experts in the field? Keep in mind that your presentation fits into a larger picture that includes workplace culture, community visibility, and/or brand identity.

The key elements of a good presentation are content , organization , and delivery . There are both substance and style aspects of content. Substance elements include the originality and significance of your idea, the quality of your research and analysis, clarity, and the potential impact of your recommendations. Style aspects of content include confidence and credibility, both of which have a significant impact on how you—and your message—are received.

Good organization starts with a strong opening and continues in a logical and well-supported manner throughout the presentation, leading to a close that serves as a resolution of the problem or a summary of the situation you’ve presented. The audience experiences good organization as a sense of flow—an inevitable forward movement to a satisfying close. This forward momentum also requires speakers to have a certain level of technical and information-management competency. To the latter point, good presentation requires a presenter to put thought into information design, from the structure and content of slides to the transitions between individual points, slides and topics.

Delivery entails a range of factors from body language and word choice to vocal variety. In this category, your audience is responding to your personality and professionalism. For perspective, one of the three evaluation categories on the official Toastmasters speaker evaluation form is “As I Saw You” with the parenthetical items “approach, position, personal appearance, facial expression, gestures and detracting mannerisms.” A good presenter has a passion for the subject and an ability to convey and perhaps elicit that emotion in the audience. Audience engagement—through eye contact, facial expression, and perhaps the use of gestures or movement—also contributes to an effective presentation. However, to the point in the Toastmasters evaluation, gestures, movement and other mannerisms can be distracting. What works is natural (not staged) movement that reinforces communication of your idea.

With those key features and presentation-evaluation criteria in mind, let’s add a disclaimer. The reality is that your features won’t matter if you don’t deliver one essential message: relevance.

Whether you think in Toastmasters’ terminology—”What’s in it for me? (WIIFM)” from the audience perspective—or put yourself in the audience’s position and ask “So what?” it’s a question that you need to answer early.

To Watch: Richard Mulholland, “A Formula for Delivering Effective PResentations”

In this speech, presentation coach Richard Mulholland offers a memorable formula for effective presentations: give the audience a reason to care; give them a reason to believe; tell them what they need to know; tell them what they need to do. [1]

You can view the transcript for “Richard Mulholland provides a Formula for Delivering Effective Presentations” here (opens in new window) .

What to watch for:

Mulholland makes his point clearly by “rewriting” a TED talk he once saw (beginning at 0:53). As Mulholland points out, the topic was fascinating, but the speaker failed to give his audience a reason to care about it from the outset. In Mulholland’s version of the speech, structured according to his four-part formula, the speech no longer buries the lead; it starts with a question that will grab the attention of the audience and “give them a reason to care.”

Purpose, Audience, and Message

It may be helpful to think of your presentation as having three key moving parts or interlocking gears: purpose, audience, and message. Let’s walk through the presentation-development process at this planning level.

Generally, the first step in developing a presentation is identifying your purpose. Purpose is a multi-layered term, but in this context, it simply means objective or intended outcome. And why is this? To riff on the classic Yogi Berra quote, if you don’t know where you’re going, you might as well be somewhere else. That is, don’t waste your audience’s (or your own) time.

Your purpose will determine both your content and approach and suggest supplemental tools, audience materials, and room layout. Perhaps your purpose is already defined for you: perhaps your manager has asked you to research three possible sites for a new store. In this case, it’s likely there’s an established evaluation criteria and format for presenting that information. Voila! Your content and approach is defined. If you don’t have a defined purpose, consider whether your objective is to inform, to educate, or to inspire a course of action. State that objective in a general sense, including what action you want your audience to take based on your presentation. Once you have that information sketched in, consider your audience.

The second step in the presentation development process is audience research. Who are the members of your audience? Why are they attending this conference, meeting, or presentation? This step is similar to the demographic and psychographic research marketers conduct prior to crafting a product or service pitch—and is just as critical. Key factors to consider include your audience’s age range, educational level, industry/role, subject matter knowledge, etc. These factors matter for two reasons: you need to know what they know and what they need to know.

Understanding your audience will allow you to articulate what may be the most critical aspect of your presentation: “WIIFM,” or what’s in it for them. Profiling your audience also allows you adapt your message so it’s effective for this particular audience. That is, to present your idea (proposal, subject matter, recommendations) at a depth and in a manner (language, terminology, tools) that’s appropriate. Don’t expect your audience to meet you where you are; meet them where they are and then take them where you want to go together.

Returning to the site analysis example mentioned earlier, knowing your audience also means clearly understanding what management expects from you. Are you serving in an analyst role—conducting research and presenting “just the facts”—to support a management decision? Or are you expected to make a specific recommendation? Be careful of power dynamics and don’t overstep your role. Either way, be prepared to take a stand and defend your position. You never know when a routine stand-and-deliver could become a career-defining opportunity.

The third step is honing your message. In “TED’s Secret to Great Public Speaking,” TED Conference curator Chris Anderson notes that there’s “no single formula” for a compelling talk, but there is one common denominator: great speakers build an idea inside the minds of their audience. Ideas matter because they’re capable of changing our perceptions, our actions, and our world. As Anderson puts it, “Ideas are the most powerful force shaping human culture.” [2]

So if ideas are that powerful, more is better, right? Perhaps a handful or a baker’s dozen? Wrong. As any seasoned sales person knows, you don’t walk into a meeting with a prospective client and launch into an overview of every item in your company’s product or service line. That’s what’s known as “throwing spaghetti on the wall to see what sticks.” And that’s an approach that will have you wearing your spaghetti—and perhaps the dust from one of your client’s shoes on your backside as well. What audience members expect is that you’ve done your homework, that you know them and their pain, and that you have something to offer: a fresh perspective, an innovative approach, or a key insight that will change things for the better. As Chris Anderson says, “Pick one idea, and make it the through-line running through your entire talk.” [3] One message, brought vividly and relevantly to life.

So now that you have a macro view of the presentation-development process, let’s review what can—and often does—go wrong so we can avoid the common mistakes.

Practice Question

- Mulholland, Richard, and Mann, Howard. Boredom Slayer: A Speaker’s Guide to Presenting Like a Pro . Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2018. ↵

- Anderson, Chris. “TED’s Secret to Great Public Speaking.” TED, March 2016. ↵

- Parts of a good presentation. Authored by : Nina Burokas. Provided by : Lumen Learning. Located at : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-businesscommunicationmgrs/chapter/parts-of-a-good-presentation/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Whiteboard presentation. Provided by : WOCinTech. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/FbSEv5 . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Richard Mulholland provides a Formula for Delivering Effective Presentations. Authored by : GIBS Business School. Located at : https://youtu.be/LQTpIYjUm7E . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PLoS Comput Biol

- v.17(12); 2021 Dec

Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides

Kristen m. naegle.

Biomedical Engineering and the Center for Public Health Genomics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, United States of America

Introduction

The “presentation slide” is the building block of all academic presentations, whether they are journal clubs, thesis committee meetings, short conference talks, or hour-long seminars. A slide is a single page projected on a screen, usually built on the premise of a title, body, and figures or tables and includes both what is shown and what is spoken about that slide. Multiple slides are strung together to tell the larger story of the presentation. While there have been excellent 10 simple rules on giving entire presentations [ 1 , 2 ], there was an absence in the fine details of how to design a slide for optimal effect—such as the design elements that allow slides to convey meaningful information, to keep the audience engaged and informed, and to deliver the information intended and in the time frame allowed. As all research presentations seek to teach, effective slide design borrows from the same principles as effective teaching, including the consideration of cognitive processing your audience is relying on to organize, process, and retain information. This is written for anyone who needs to prepare slides from any length scale and for most purposes of conveying research to broad audiences. The rules are broken into 3 primary areas. Rules 1 to 5 are about optimizing the scope of each slide. Rules 6 to 8 are about principles around designing elements of the slide. Rules 9 to 10 are about preparing for your presentation, with the slides as the central focus of that preparation.

Rule 1: Include only one idea per slide

Each slide should have one central objective to deliver—the main idea or question [ 3 – 5 ]. Often, this means breaking complex ideas down into manageable pieces (see Fig 1 , where “background” information has been split into 2 key concepts). In another example, if you are presenting a complex computational approach in a large flow diagram, introduce it in smaller units, building it up until you finish with the entire diagram. The progressive buildup of complex information means that audiences are prepared to understand the whole picture, once you have dedicated time to each of the parts. You can accomplish the buildup of components in several ways—for example, using presentation software to cover/uncover information. Personally, I choose to create separate slides for each piece of information content I introduce—where the final slide has the entire diagram, and I use cropping or a cover on duplicated slides that come before to hide what I’m not yet ready to include. I use this method in order to ensure that each slide in my deck truly presents one specific idea (the new content) and the amount of the new information on that slide can be described in 1 minute (Rule 2), but it comes with the trade-off—a change to the format of one of the slides in the series often means changes to all slides.

Top left: A background slide that describes the background material on a project from my lab. The slide was created using a PowerPoint Design Template, which had to be modified to increase default text sizes for this figure (i.e., the default text sizes are even worse than shown here). Bottom row: The 2 new slides that break up the content into 2 explicit ideas about the background, using a central graphic. In the first slide, the graphic is an explicit example of the SH2 domain of PI3-kinase interacting with a phosphorylation site (Y754) on the PDGFR to describe the important details of what an SH2 domain and phosphotyrosine ligand are and how they interact. I use that same graphic in the second slide to generalize all binding events and include redundant text to drive home the central message (a lot of possible interactions might occur in the human proteome, more than we can currently measure). Top right highlights which rules were used to move from the original slide to the new slide. Specific changes as highlighted by Rule 7 include increasing contrast by changing the background color, increasing font size, changing to sans serif fonts, and removing all capital text and underlining (using bold to draw attention). PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor.

Rule 2: Spend only 1 minute per slide

When you present your slide in the talk, it should take 1 minute or less to discuss. This rule is really helpful for planning purposes—a 20-minute presentation should have somewhere around 20 slides. Also, frequently giving your audience new information to feast on helps keep them engaged. During practice, if you find yourself spending more than a minute on a slide, there’s too much for that one slide—it’s time to break up the content into multiple slides or even remove information that is not wholly central to the story you are trying to tell. Reduce, reduce, reduce, until you get to a single message, clearly described, which takes less than 1 minute to present.

Rule 3: Make use of your heading

When each slide conveys only one message, use the heading of that slide to write exactly the message you are trying to deliver. Instead of titling the slide “Results,” try “CTNND1 is central to metastasis” or “False-positive rates are highly sample specific.” Use this landmark signpost to ensure that all the content on that slide is related exactly to the heading and only the heading. Think of the slide heading as the introductory or concluding sentence of a paragraph and the slide content the rest of the paragraph that supports the main point of the paragraph. An audience member should be able to follow along with you in the “paragraph” and come to the same conclusion sentence as your header at the end of the slide.

Rule 4: Include only essential points

While you are speaking, audience members’ eyes and minds will be wandering over your slide. If you have a comment, detail, or figure on a slide, have a plan to explicitly identify and talk about it. If you don’t think it’s important enough to spend time on, then don’t have it on your slide. This is especially important when faculty are present. I often tell students that thesis committee members are like cats: If you put a shiny bauble in front of them, they’ll go after it. Be sure to only put the shiny baubles on slides that you want them to focus on. Putting together a thesis meeting for only faculty is really an exercise in herding cats (if you have cats, you know this is no easy feat). Clear and concise slide design will go a long way in helping you corral those easily distracted faculty members.

Rule 5: Give credit, where credit is due

An exception to Rule 4 is to include proper citations or references to work on your slide. When adding citations, names of other researchers, or other types of credit, use a consistent style and method for adding this information to your slides. Your audience will then be able to easily partition this information from the other content. A common mistake people make is to think “I’ll add that reference later,” but I highly recommend you put the proper reference on the slide at the time you make it, before you forget where it came from. Finally, in certain kinds of presentations, credits can make it clear who did the work. For the faculty members heading labs, it is an effective way to connect your audience with the personnel in the lab who did the work, which is a great career booster for that person. For graduate students, it is an effective way to delineate your contribution to the work, especially in meetings where the goal is to establish your credentials for meeting the rigors of a PhD checkpoint.

Rule 6: Use graphics effectively

As a rule, you should almost never have slides that only contain text. Build your slides around good visualizations. It is a visual presentation after all, and as they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. However, on the flip side, don’t muddy the point of the slide by putting too many complex graphics on a single slide. A multipanel figure that you might include in a manuscript should often be broken into 1 panel per slide (see Rule 1 ). One way to ensure that you use the graphics effectively is to make a point to introduce the figure and its elements to the audience verbally, especially for data figures. For example, you might say the following: “This graph here shows the measured false-positive rate for an experiment and each point is a replicate of the experiment, the graph demonstrates …” If you have put too much on one slide to present in 1 minute (see Rule 2 ), then the complexity or number of the visualizations is too much for just one slide.

Rule 7: Design to avoid cognitive overload

The type of slide elements, the number of them, and how you present them all impact the ability for the audience to intake, organize, and remember the content. For example, a frequent mistake in slide design is to include full sentences, but reading and verbal processing use the same cognitive channels—therefore, an audience member can either read the slide, listen to you, or do some part of both (each poorly), as a result of cognitive overload [ 4 ]. The visual channel is separate, allowing images/videos to be processed with auditory information without cognitive overload [ 6 ] (Rule 6). As presentations are an exercise in listening, and not reading, do what you can to optimize the ability of the audience to listen. Use words sparingly as “guide posts” to you and the audience about major points of the slide. In fact, you can add short text fragments, redundant with the verbal component of the presentation, which has been shown to improve retention [ 7 ] (see Fig 1 for an example of redundant text that avoids cognitive overload). Be careful in the selection of a slide template to minimize accidentally adding elements that the audience must process, but are unimportant. David JP Phillips argues (and effectively demonstrates in his TEDx talk [ 5 ]) that the human brain can easily interpret 6 elements and more than that requires a 500% increase in human cognition load—so keep the total number of elements on the slide to 6 or less. Finally, in addition to the use of short text, white space, and the effective use of graphics/images, you can improve ease of cognitive processing further by considering color choices and font type and size. Here are a few suggestions for improving the experience for your audience, highlighting the importance of these elements for some specific groups:

- Use high contrast colors and simple backgrounds with low to no color—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment.

- Use sans serif fonts and large font sizes (including figure legends), avoid italics, underlining (use bold font instead for emphasis), and all capital letters—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment [ 8 ].

- Use color combinations and palettes that can be understood by those with different forms of color blindness [ 9 ]. There are excellent tools available to identify colors to use and ways to simulate your presentation or figures as they might be seen by a person with color blindness (easily found by a web search).

- In this increasing world of virtual presentation tools, consider practicing your talk with a closed captioning system capture your words. Use this to identify how to improve your speaking pace, volume, and annunciation to improve understanding by all members of your audience, but especially those with a hearing impairment.

Rule 8: Design the slide so that a distracted person gets the main takeaway

It is very difficult to stay focused on a presentation, especially if it is long or if it is part of a longer series of talks at a conference. Audience members may get distracted by an important email, or they may start dreaming of lunch. So, it’s important to look at your slide and ask “If they heard nothing I said, will they understand the key concept of this slide?” The other rules are set up to help with this, including clarity of the single point of the slide (Rule 1), titling it with a major conclusion (Rule 3), and the use of figures (Rule 6) and short text redundant to your verbal description (Rule 7). However, with each slide, step back and ask whether its main conclusion is conveyed, even if someone didn’t hear your accompanying dialog. Importantly, ask if the information on the slide is at the right level of abstraction. For example, do you have too many details about the experiment, which hides the conclusion of the experiment (i.e., breaking Rule 1)? If you are worried about not having enough details, keep a slide at the end of your slide deck (after your conclusions and acknowledgments) with the more detailed information that you can refer to during a question and answer period.

Rule 9: Iteratively improve slide design through practice

Well-designed slides that follow the first 8 rules are intended to help you deliver the message you intend and in the amount of time you intend to deliver it in. The best way to ensure that you nailed slide design for your presentation is to practice, typically a lot. The most important aspects of practicing a new presentation, with an eye toward slide design, are the following 2 key points: (1) practice to ensure that you hit, each time through, the most important points (for example, the text guide posts you left yourself and the title of the slide); and (2) practice to ensure that as you conclude the end of one slide, it leads directly to the next slide. Slide transitions, what you say as you end one slide and begin the next, are important to keeping the flow of the “story.” Practice is when I discover that the order of my presentation is poor or that I left myself too few guideposts to remember what was coming next. Additionally, during practice, the most frequent things I have to improve relate to Rule 2 (the slide takes too long to present, usually because I broke Rule 1, and I’m delivering too much information for one slide), Rule 4 (I have a nonessential detail on the slide), and Rule 5 (I forgot to give a key reference). The very best type of practice is in front of an audience (for example, your lab or peers), where, with fresh perspectives, they can help you identify places for improving slide content, design, and connections across the entirety of your talk.

Rule 10: Design to mitigate the impact of technical disasters

The real presentation almost never goes as we planned in our heads or during our practice. Maybe the speaker before you went over time and now you need to adjust. Maybe the computer the organizer is having you use won’t show your video. Maybe your internet is poor on the day you are giving a virtual presentation at a conference. Technical problems are routinely part of the practice of sharing your work through presentations. Hence, you can design your slides to limit the impact certain kinds of technical disasters create and also prepare alternate approaches. Here are just a few examples of the preparation you can do that will take you a long way toward avoiding a complete fiasco:

- Save your presentation as a PDF—if the version of Keynote or PowerPoint on a host computer cause issues, you still have a functional copy that has a higher guarantee of compatibility.

- In using videos, create a backup slide with screen shots of key results. For example, if I have a video of cell migration, I’ll be sure to have a copy of the start and end of the video, in case the video doesn’t play. Even if the video worked, you can pause on this backup slide and take the time to highlight the key results in words if someone could not see or understand the video.

- Avoid animations, such as figures or text that flash/fly-in/etc. Surveys suggest that no one likes movement in presentations [ 3 , 4 ]. There is likely a cognitive underpinning to the almost universal distaste of pointless animations that relates to the idea proposed by Kosslyn and colleagues that animations are salient perceptual units that captures direct attention [ 4 ]. Although perceptual salience can be used to draw attention to and improve retention of specific points, if you use this approach for unnecessary/unimportant things (like animation of your bullet point text, fly-ins of figures, etc.), then you will distract your audience from the important content. Finally, animations cause additional processing burdens for people with visual impairments [ 10 ] and create opportunities for technical disasters if the software on the host system is not compatible with your planned animation.

Conclusions

These rules are just a start in creating more engaging presentations that increase audience retention of your material. However, there are wonderful resources on continuing on the journey of becoming an amazing public speaker, which includes understanding the psychology and neuroscience behind human perception and learning. For example, as highlighted in Rule 7, David JP Phillips has a wonderful TEDx talk on the subject [ 5 ], and “PowerPoint presentation flaws and failures: A psychological analysis,” by Kosslyn and colleagues is deeply detailed about a number of aspects of human cognition and presentation style [ 4 ]. There are many books on the topic, including the popular “Presentation Zen” by Garr Reynolds [ 11 ]. Finally, although briefly touched on here, the visualization of data is an entire topic of its own that is worth perfecting for both written and oral presentations of work, with fantastic resources like Edward Tufte’s “The Visual Display of Quantitative Information” [ 12 ] or the article “Visualization of Biomedical Data” by O’Donoghue and colleagues [ 13 ].

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the countless presenters, colleagues, students, and mentors from which I have learned a great deal from on effective presentations. Also, a thank you to the wonderful resources published by organizations on how to increase inclusivity. A special thanks to Dr. Jason Papin and Dr. Michael Guertin on early feedback of this editorial.

Funding Statement

The author received no specific funding for this work.

Effective Presentations: Optimize the Learning Experience With Evidence-Based Multimedia Principles [Incl. Seminar]

TABLE OF CONTENTS

What is an effective presentation.

Professional education requires presentations, from a small discussion or a short video to speaking to a lecture hall with an audience of hundreds. In fact, presentations are at the core of the educational process. With the effort to view all our educational efforts through an evidence-based lens, the construction of an effective presentation needs to undergo the same scrutiny. Whether a presenter intends to share plans, teach educational information, give updates on project progress, or convey the results of research, the extent to which the audience understands and remembers the presentation relies not only on the quality of the content but also the manner in which that content is presented. While the medium of the presentation may range from written content to graphics, videos, live presentations, or any combination of these and more, each of these mediums can be enhanced and made more effective by the use of evidence-based practices for presenting. Regardless of the medium, effective presentations have the same key features: they are appealing, engaging, informative, and concise. Effective presentations gain attention and captivate the audience, but most importantly, they convey information and ideas memorably.

With the integration of technology and online learning, educators have more opportunities than ever to present rich content that enhances and supports student learning. However, these opportunities can be intimidating to educators striving to engage students, as it can be daunting to create visually appealing and informative materials. Additionally, many educators feel pressured by the continued myth of learning styles: the widespread misconception that learning materials should match students’ visual, auditory, or kinesthetic “styles” to optimize learning (1). Despite being featured in many articles and discussions, there is no compelling evidence that matching educational content to learner’s style preferences increases educational outcomes. However, using multiple modes of delivery such as visuals, audio, and active learning has been shown to benefit all learners. In other words, no matter their stated preference, all learners benefit from a variety of media. Using evidence-based principles for multimedia content such as the principles found in Richard Mayer’s multimedia learning as well as the principles of graphic design and universal design supports learning and increases educational outcomes.

Why effective presentations work

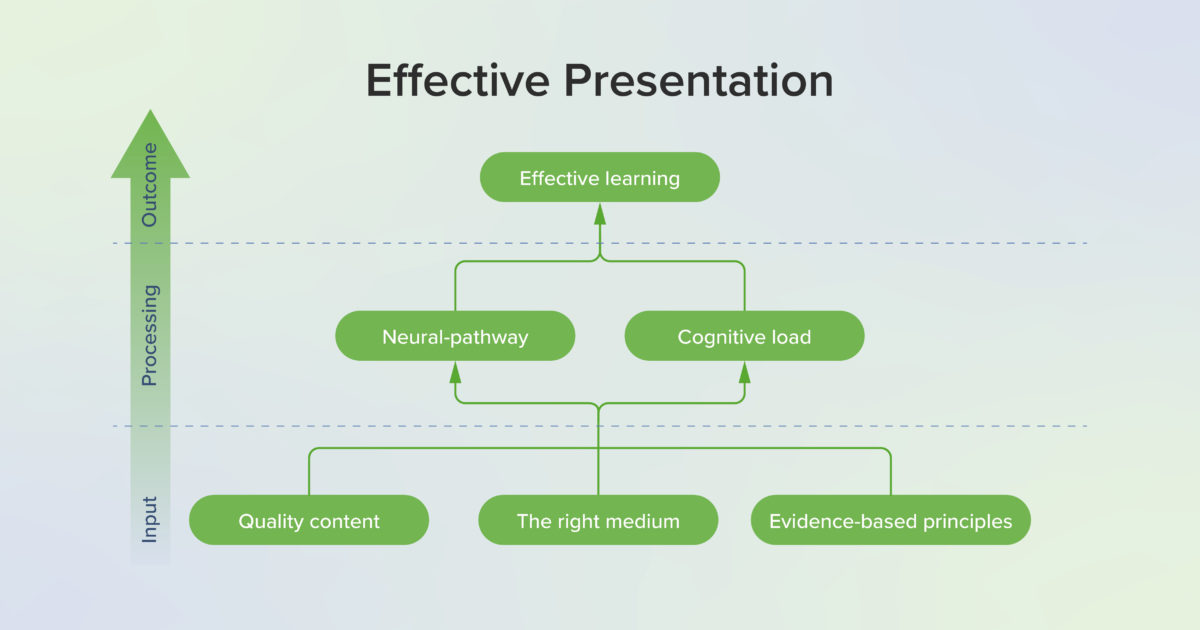

What makes a presentation effective? Is an appealing and engaging presentation also an effective one? Research from cognitive science provides a foundation for understanding how verbal and pictorial information are processed by the learner’s mind during a presentation.

Mayer’s cognitive theory of multimedia learning

Based in cognitive science research, Mayer’s evidence-based approach to multimedia and cognition has greatly influenced both instructional design and the learning sciences. Mayer’s cognitive theory of multimedia learning comprises three learning principles: the dual channel principle, the limited capacity principle, and the active processing principle. Mayer’s cognitive theory of multimedia learning lays the theoretical foundation that underlies the practical applications to boost cognitive processes (2).

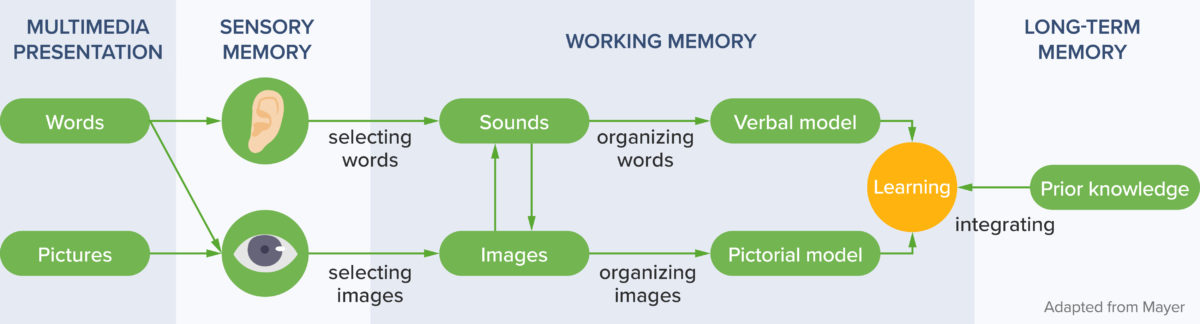

The dual channel principle proposes that learners process verbal and pictorial information via two separate channels (see figure below). Within each channel, learners can process limited amounts of information simultaneously due to limits in working memory, a phenomenon known as the limited capacity principle . In addition to these principles describing learning via the verbal and pictorial channels, the active processing principle proposes deeper learning occurs when learners are actively engaged in cognitive processing, such as attending to relevant information, creating mental schema to organize the material cognitively, and then relating to prior knowledge (3). These three principles work in tandem to describe the learning process that occurs when an audience of learners experiences a multimedia presentation.

Cognitive Load Theory, Adapted from Mayer (3) . Depicting how verbal and visual information is processed in dual channels through sensory, working, and long-term memory to create meaningful learning.

As learners listen to a lecture or watch a video, words and images are detected in the sensory memory and held for a very brief period of time. As the learners attend to relevant information, they are selecting words and images , which allows the selected information to move into the working memory where it may be held for a short period of time. However, working memory is limited to about 30 seconds and can only hold a few bits of information at a time. Organizing the words and images creates a coherent cognitive representation (schema) of these bits of information in the working memory. After the words and images are selected and then organized into schema, integrating these bits of information with prior knowledge from long term memory creates meaningful learning.

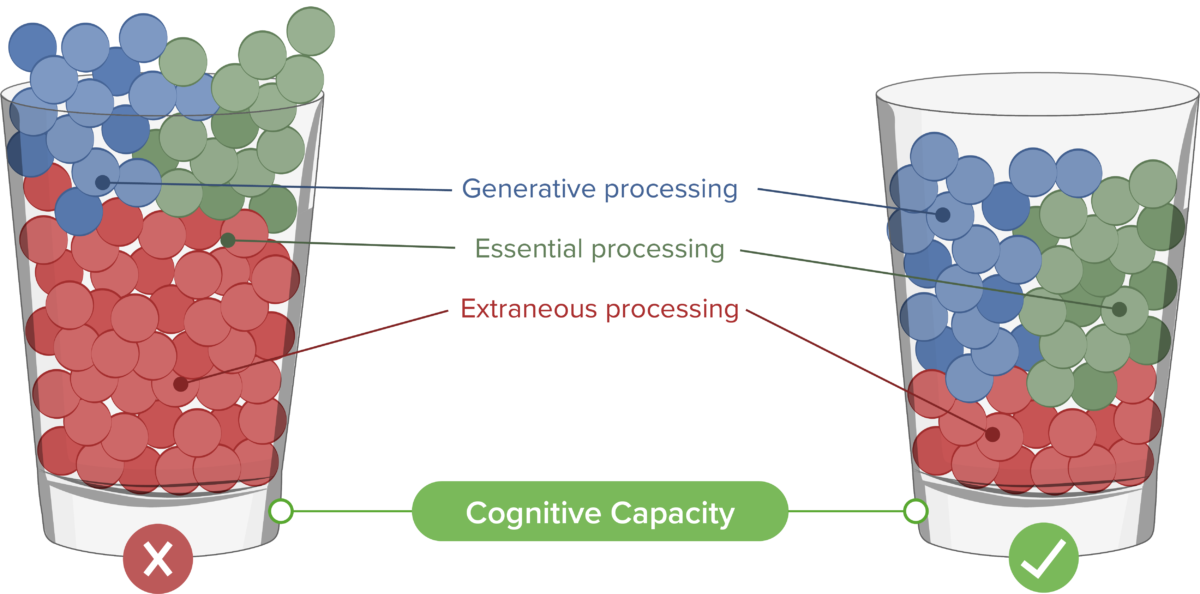

Cognitive Capacity . Three types of processing combine to determine cognitive capacity. To improve essential processing and generative processing, extraneous processing should be limited as much as possible .

No matter how important the content may be, the capacity of learners to retain ideas from a single presentation is limited. The amount of information a learner can process as they select, organize, and integrate the ideas in a presentation relates to the cognitive load, which includes Essential, Extraneous, and Generative cognitive processing. Essential cognitive processing is required for the learner to create a cognitive representation of necessary and relevant information. This is the desired part of processing but should be managed to not overload the cognitive process. Extraneous processing refers to cognitive processing that does not contribute to learning and is often caused by poor design. Extraneous processing should be eliminated whenever possible to free up cognitive resources. Generative cognitive processing gives meaning to the material and creates deep learning. Learners must be motivated to engage and understand the information for this type of processing to occur.

Foundations in neuroscience

What we know about cognition and learning has been supported and informed by research in neuroscience (4). Neuroscience advances have also allowed us to gain deeper understanding into cognitive science principles, including those on multimedia learning. Researchers have been increasingly tracking learner eye movements to study learners’ attention and interest as a method of validating the impact of multimedia principles, and the results have supported the benefits of proper multimedia design on learner performance (5). Another avenue of research with great potential includes functional MRI (fMRI) readings or electroencephalography (EEG) (6). It has long been established that verbal and pictorial data is processed in different parts of the brain. More recently however, by examining changes in blood flow in different regions of the brain, researchers in Sweden were able to demonstrate that increased extraneous load could impact the effectiveness of learning, in line with the dual channel principle (7).

Evidence for effective presentations

Mayer’s multimedia principles.

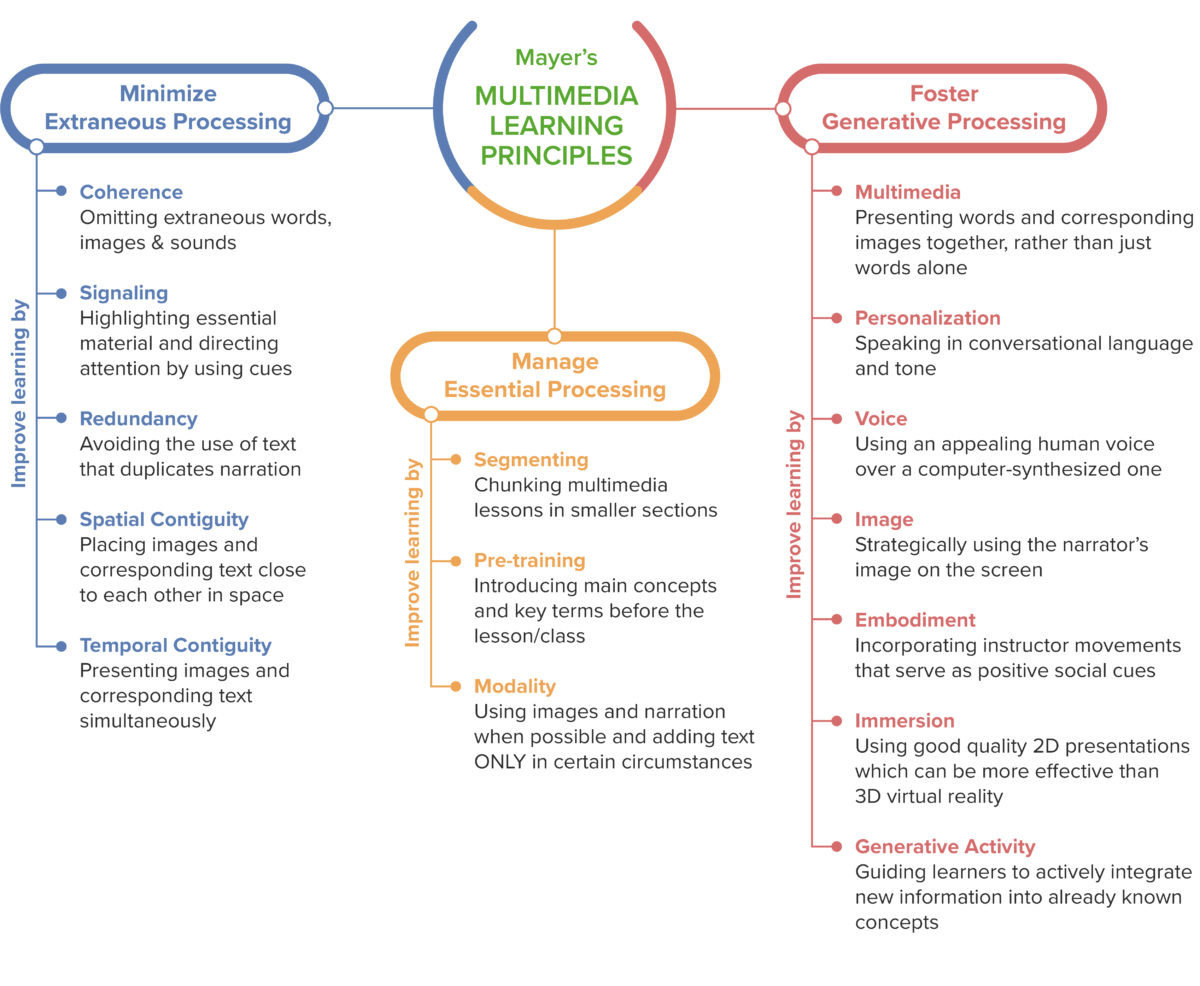

Mayer’s Multimedia Principles.

Mayer’s multimedia principles are a set of evidence-based guidelines for producing multimedia based on facilitating essential processing, reducing extraneous processing, and promoting generative processing (8). Mayer’s list of principles often includes fifteen principles, some of which have changed over time, and in a study conducted with medical students, the following nine principles were found to be particularly effective (3). The first three of these principles are used to reduce extraneous processing.

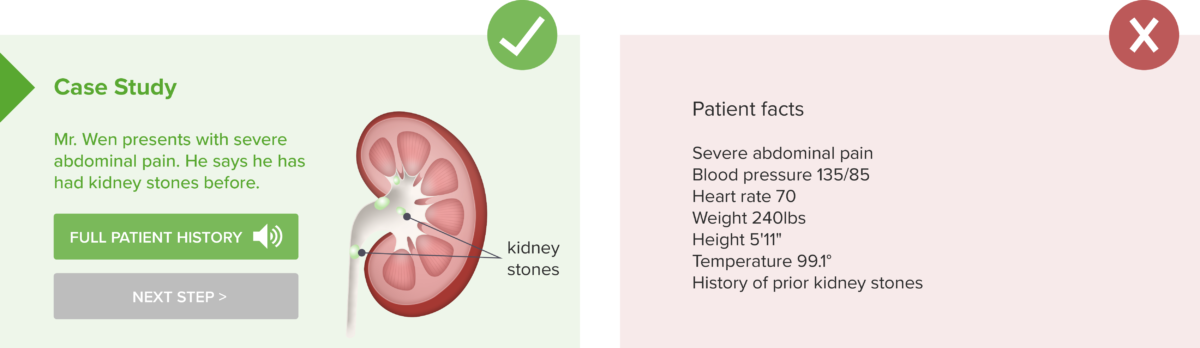

Principles for reducing extraneous processing:

- Coherence principle: eliminate extraneous material

- Signaling principle: highlight essential material

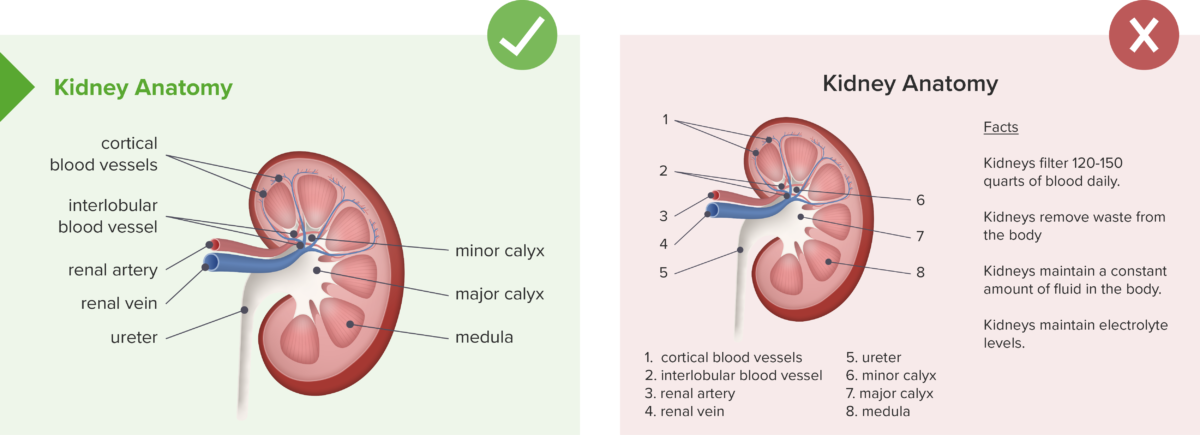

- Spatial contiguity principle: place printed words near corresponding graphics

To illustrate these principles, we will use a lesson about the kidneys. The instructor wants to make diagrams of the anatomy to use during discussion. The coherence principle says to only include the information necessary to the lesson. Graphics such as clip art, information that does not relate to anatomy, or unnecessary music reduces cognitive capacity. The signaling principle says to highlight essential material; this might include putting important content in bold or larger font. Or, if the kidney is shown in situ , the rest of the anatomy may be shown in grayscale or a much lighter color to de-emphasize it. The spatial contiguity principle says to place printed words, such as the labels, near the graphics.

Reduce extraneous processing . Do : keep labels next to diagrams, use only essential material, highlight essential material such as titles. Don’t: separate labels from diagrams, include extra facts, or have excessive text on a slide, especially with no indication of what is most important.

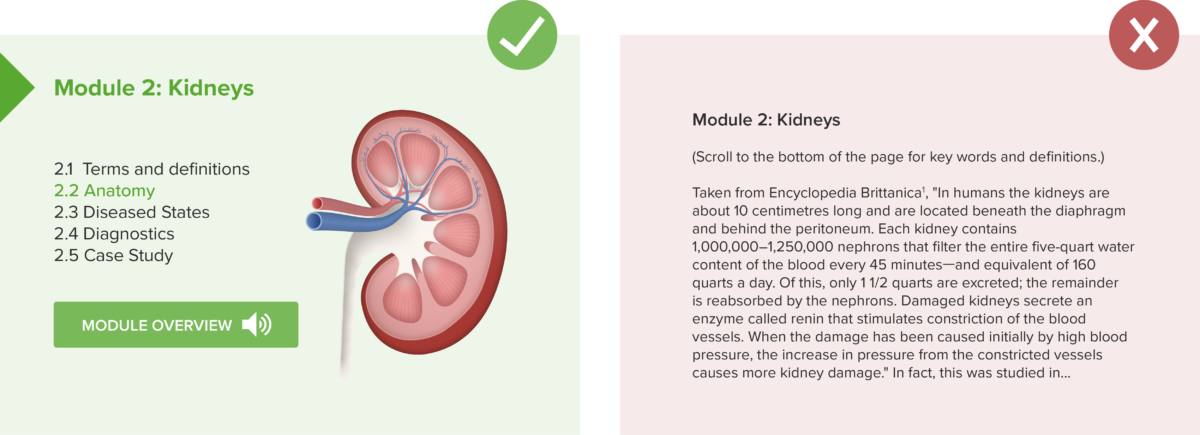

Principles for managing essential processing:

- Pre-training principle: provide pre-training in names and characteristics of key concepts

- Segmenting principle: break lessons into learner-controlled segments

- Modality principle: present words in spoken form

The next three principles are used to manage essential processing. If the kidney lesson moves into diseased states or diagnostics, the pre-training principle says that learners should be given information on any unfamiliar terminology before the lesson begins. To satisfy the segmenting principle , the learner should be able to control each piece of the lesson. For example, a “next” button may allow them to progress from pre-training to anatomy to diseased states and then diagnostics. The modality principle says that words should be spoken when possible. Voice-over can be used and text can be limited to essential material such as key definitions or lists.

Manage essential processing. Do: Present terms and key concepts first, break lessons into user-controlled segments, and present words in spoken form. Don’t: Give long blocks of text for students to read without priming students for key concepts.

Principles for fostering generative processing:

- Multimedia principle: present words and pictures rather than words alone

- Personalization principle: present words in conversational or polite style

- Voice principle: use a human voice rather than a machine voice

Mayer’s work also includes principles to increase generative processing. The multimedia principle is a direct result of the dual channel principle and limited capacity principle. Words and pictures together stimulate both channels and allow the memory to process more information than words alone. To adhere to the personalization principle to promote deeper learning, a case study is better presented as a story than a page of diagnostics and patient demographics. Finally, the voice principle says that a human voice is more desirable, so it is better to use the instructor’s voice when doing voice-overs rather than auto-generated readers.

Foster generative processing. Do: Present words and pictures, present words in conversational style, and use a human voice. Don’t: Present text only, present words as a list of facts or overly technical language, or use a computer-generated voice.

Additional multimedia principles:

- Temporal contiguity principle: present words and pictures simultaneously rather than successively

- Redundancy principle: for a fast paced lesson, people learn better from graphics and narration rather than graphics, narration, and text

- Image principle: people do not learn better if a static image of the instructor is added to the presentation