- My learning

Critical Thinking Rubrics

2021 research-based critical thinking rubrics.

We're pleased to share these research-based Critical Thinking rubrics created in collaboration with the National Center for Improvement of Educational Assessment (Center for Assessment) , based on a comprehensive review of the literature about Critical Thinking.

- 2021 Critical Thinking Rubric: Grades K-2

- 2021 Critical Thinking Rubric: Grades 3-5

- 2021 Critical Thinking Rubric: Grades 6-12

These research-based rubrics are designed to provide useful, formative information that teachers can use to guide instruction and provide feedback to students on their overall performance. Students can also use the rubrics to reflect on their own learning.

Looking for older versions of PBLWorks/BIE Critical Thinking Rubrics? You can also find them in the resources section on this page!

To view or download this resource, log in here.

Enter your MyPBLWorks email or username.

Enter the password that accompanies your username.

Advertisement

Radical rubrics: implementing the critical and creative thinking general capability through an ecological approach

- Open access

- Published: 20 April 2022

- Volume 50 , pages 729–745, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Dan Harris ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1138-8229 1 ,

- Kathryn Coleman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9885-9299 1 &

- Peter J. Cook ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2942-1568 1

6060 Accesses

3 Citations

11 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

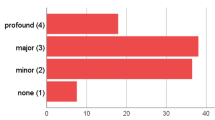

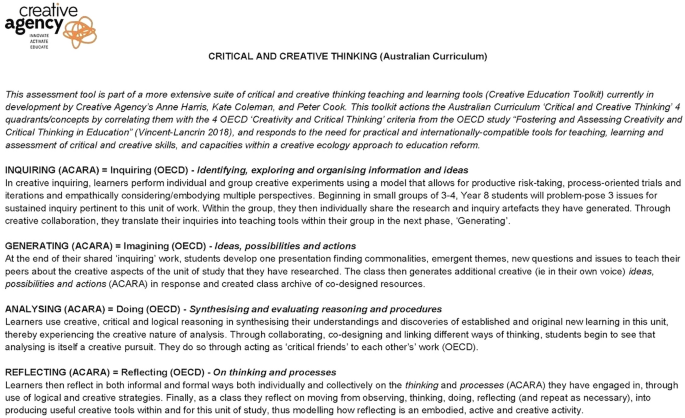

This article details how and why we have developed a flexible and responsive process-based rubric exemplar for teaching, learning, and assessing critical and creative thinking. We hope to contribute to global discussions of and efforts toward instrumentalising the challenge of assessing, but not standardising, creativity in compulsory education. Here, we respond to the key ideas of the four interrelated elements in the critical and creative thinking general capability in the Australian Curriculum learning continuum: inquiring; generating ideas, possibilities, actions; reflecting on thinking processes; and analysing, synthesising and evaluating reasoning and procedures. The rubrics, radical because they privilege process over outcome, have been designed to be used alongside the current NAPLAN tests in Years 5, 7 and 9 to build an Australian-based national creativity measure. We do so to argue the need for local and global measures of creativity in education as the first round of testing and results of the PISA Assessment of Creative Thinking approach and to contribute to the recognition of creative thinking (and doing) as a core twenty-first century literacy alongside literacy and numeracy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Mediated Learning Leading Development—The Social Development Theory of Lev Vygotsky

How should we change teaching and assessment in response to increasingly powerful generative Artificial Intelligence? Outcomes of the ChatGPT teacher survey

The Imperative of an Arts-Led Curriculum

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This paper promotes the inclusion of critical and creative thinking in Initial Teacher Education (ITE)—and in turn, school-based education—through the development and use of process-based creative inquiry (PBCI) rubrics. We propose that creative inquiry rubrics are radical in their attention to teaching, learning and assessing processes over outcomes. We advocate for a process orientation as an antidote to the continuing standardisation of creativity measures, most recently seen in the incoming PISA creative thinking test (OECD, 2019 ). Within such a creative ecological approach (Harris, 2016a ), the use of PBCI rubrics is underpinned by curriculum as praxis (Grundy, 1987 ), where the practice of becoming a teacher is intertwined with the pre-service teachers' experience of being creative and critical thinking learners. We are also drawing on Freirean praxis pedagogy beliefs ( 1972 ), where reflection and immersion in the field connect theoretical underpinnings explored in initial teacher education courses with their practical implementation during professional experiences. The radical rubric approach aims to provide pre-service teachers with meaningful, authentic experiences in transforming creative and critical education so that they are equipped to design and develop meaningful, authentic critical and creative learning experiences in their future schools and classrooms. ITE programs are encouraged to integrate critical and creative inquiry activities into their cornerstone and capstone units with these radical rubrics to prepare graduates to contribute to the education sector's broader creative ecology. This approach is timely as we transition from pandemic pedagogies to endemic practices.

Positioning critical and creative thinking in initial teacher education

Australian ITE programs are complex programs focussed on learning about teaching practices through the study of curriculum and pedagogy. These programs are developed through well-defined accredited learning designs, underpinned by curriculum, policy, educational theories and pedagogical practices in conjunction with school-based work-integrated learning (WIL) placements to prepare pre-service teachers for success. To achieve this, ITE programs are responsive to multiple reforms: professional regulatory bodies such as the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL) and the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA), including recent shifts in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, and compliance standards that are enforced through state and commonwealth government authorities. Higher education providers must meet standards from authorities in their home state to enable graduates to register as teachers. University courses are mapped against program standards set by AITSL to ensure that pre-service teachers are classroom ready for the challenging and diverse educational contexts they will encounter.

Reforms and systemic stresses affect early-career graduate teachers' creativity and teaching practices. They are deterred by embedded school practices rather than developing and designing cross-cutting innovative, curious and collaborative future-focussed learning and teaching. Reform pressures are increased by systemic stressors that focus on performance, high-stakes assessment, national testing results and the need to meet national and international benchmarks. Over the last few years, Australian reforms have been directed by the following vision documents: Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group Report Action Now – Classroom Ready Teachers ( 2014 ); compulsory testing for teachers entering the profession, implemented as the Literacy and Numeracy Test for Initial Teacher Education (ACER, 2016 ); National Review of Teacher Registration (AITSL, 2018 ); and current Parliamentary reviews such as the Status of the Teaching Profession (Parliament of Australia, 2019 ). While ITE programs vary institutionally, they are all limited by insufficient time to effectively deliver a coherent curriculum that is “taught, assessed and practiced” (AITSL, 2019 ) alongside strategies for integrating new workplace and socio-cultural skills like creativity. The use of more flexible and process-focussed assessment tools in ITE (provided ITE programs offer adequate learner and teacher experience integrated into their units) can positively influence school change, simultaneously promoting creative environments in classrooms and across whole schools, once ITE graduates find employment.

Developments in the Australian context

In Australia, the impetus to foster creativity and innovation, and develop critical thinking skills and creative capacities was at the forefront of The Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians (MCEETYA, 2008 ). More than a decade on, this can still be seen as a significant turning point in the national agenda toward valuing creativity in Australian education, as indicated in the Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration ( 2019 ). The need for critical and creative thinking is well established by ACARA ( 2016 ) as a general capability to be integrated across the curriculum continuum. AITSL ( 2019 ) identifies that critical and creative thinking is a teaching strategy for effective teaching and learning to foster confident, creative and innovative young Australians. These shifts signal the growing complexity of teacher responsibilities for developing teaching and assessment skills in critical and creative thinking to design learning for unknown futures.

National Australian reviews of creative and cultural education, and employment strategies (Flew & Cunningham, 2010 ; Harris, 2014 ; Harris, 2016a , 2016b a&b; Harris & Ammerman, 2016 ) have synthesised the interrelationship between education practice and the need to develop creative dispositions such as inquisitiveness, persistence, imagination and collaboration in student learning. It has been further argued within ITE programs and professional teacher/school practices that ecological perspectives via whole-school strategies and audits improve professional teacher practice (Richardson & Mishra, 2018 ). The Australian Government's Standing Committee on Employment, Education and Training's Inquiry into innovation and creativity: Workforce for the new economy (Parliament of Australia, 2016 ) was created to ensure that “Australia's tertiary system—including universities and public and private providers of vocational education and training—can meet the needs of a future labour force focussed on innovation and creativity” (n.p). These developments in the Australian national context were mirrored globally (Beghetto, et al., 2014 ; Chiam, et al., 2014 ; DOET, 2014 ; Lassig, 2019 ) pre-pandemic and indicate a groundswell of attention to creativity education and work readiness that drives the need for further development in this area as we reimagine school and education for the future.

ITE programs synthesise both the Australian Curriculum and each state or territory's local curriculum adaptations (GWA, 2018 ; QLD Government, 2018 ; NESA, 2018 ; VCAA, 2016 ). Apart from providing the general blueprint, the Australian Curriculum provides seven general capabilities encompassing knowledge, skills, behaviours and dispositions. Critical and Creative Thinking is one of the capabilities through which students “learn to generate and evaluate knowledge, clarify concepts and ideas, seek possibilities, consider alternatives and solve problems” (ACARA, 2016 ). Schools expect graduate teachers to deliver these capabilities through an integrated curriculum and inter-, multi- and transdisciplinary approaches, which we argue should be explicitly taught and commenced in ITE programs if they are to be successful. The co-authors have significant experience in teaching disciplinarily and have integrated these practices from an interdisciplinary epistemological approach, which we offer as part of the radicalising of the curriculum.

The ITE provider's challenge is to locate appropriate space within their complex teacher education programs to include all capabilities while scaffolding ways to design integrated learning and develop inter-, multi- and transdisciplinary knowledge and skills (Moss, et al., 2019 ). Including the capabilities as part of professional experience units provides practical examples of how to implement the capabilities and the associated pedagogical knowledge for learners in their future classrooms. We assert that engaging deeply in the capabilities within the discipline and curriculum units as both learners and teachers enables greater interaction of those capabilities through two-way pedagogies (Learning Policy Institute & Turnaround for Children, 2021 ) as pre-service teachers themselves learn through creative inquiry methods “to find out what students are thinking, puzzling over, feeling, and struggling with” (Darling-Hammond, 2016 , p. 86). A PBCI rubric that troubles perceived notions of creativity and presents an innovative approach to developing critical and creative thinking, appraisal and assessment qualities in ITE students would assist in achieving this transformation. All the general capabilities, including Critical and Creative Thinking, are noted on each state's syllabus websites, only some of which have been updated to align with the Australian Curriculum (all of which continue to be fluid documents). The states that have adopted these capabilities under the banner of learning across the curriculum, provide limited direction for inclusion outside of the content descriptions in some subjects and short elaborations on the ACARA site.

The inclusion of Critical and Creative Thinking in the Australian Curriculum has created an opportunity to further future-focussed learning that allows for transferable skills in a curriculum for both graduate teachers and their students. “In the Australian Curriculum, general capabilities are addressed through the learning areas and are identified where they offer opportunities to add depth and richness to student learning” (ACARA, 2016 ). Teaching a curriculum of the future requires skills and capabilities (Reeves, 2021 ), necessary in the “fourth industrial revolution” (Farrell & Corbel, 2017 ) and within post-pandemic pedagogies (McCarty, 2020 ) such as play, problem-solving, creative thinking, collaboration and digital skills. These transferable cross-cutting skills include a range of multimodal literacies (Walsh, 2010 ) and capabilities often referred to as “soft skills” (Lucas et al., 2013 ). But how do early-career teachers develop and maintain the ability to design disciplinary future-focussed creative learning and teaching? Where do early-career teachers develop their curriculum integration skills and capacities as practitioners? Arguably, these are acquired through practising over time and found in integrative disciplinary knowledge domains to support graduate teachers as learners as they traverse disciplinary and inter-, multi- and transdisciplinary skills and knowledge. The authors believe that this must begin in their initial teacher education.

Initial teacher education (ITE) and creative ecologies

A creative ecology approach (Harris, 2016a ) in ITE provides a space for learning about 'curriculum as praxis' (Grundy, 1987 ) and for Critical and Creative Thinking to be nurtured collectively and collaboratively rather than individually through a praxis pedagogy (Arnold & Mundy, 2020 ). Transferable, integrated and inter-, multi- and transdisciplinary skills are developed through inquiry-based learning (Magnussen et al., 2000 ) that allow for communication, creativity, problem solving, negotiation, teamwork, reflection, empathy and knowledge that cuts across disciplinary silos (Barnes & Shirley, 2007 ).

As a team of creative educators, we have worked with Harris' creative ecology ( 2016b ) to develop creative inquiry-based learning in a similar holistic, collaborative and creative methodology, focussed on building creative skills across educational sites and communities. This practice-related research is underpinned by Harris' body of work (for example, Harris, 2016b ) in fostering creativity in schools and communities. As such, we are led by a belief that pre-service and early-career teachers are central to generating and opening opportunities for creative ecologies within the teaching profession as they negotiate new epistemic cultures (Knorr Cetina, 2007 ). Our research is driven by a desire to create radical changes in education through a curriculum as praxis, starting within a critical praxis inquiry model of learning in ITE (Arnold, et al., 2012 ). As Grundy ( 1987 ) asserts, “the curriculum is not simply a set of plans to be implemented, but rather is constituted through an active process in which planning, acting and evaluating are all reciprocally related and integrated into the process” (p. 115). Pre-service teachers' ways of knowing about critical and creative thinking are bound by their experiences and skills in instructional strategies and assessment design within these disciplinary knowledge spaces rather than through practice as learners.

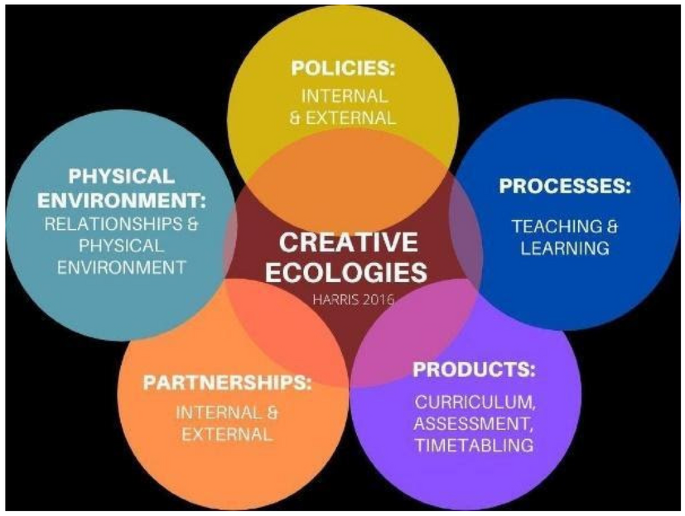

To intervene, we propose that Critical and Creative Thinking as a general capability is explicitly implemented within ITE programs through the praxis inquiry model of learning that enables pre-service teachers to make explicit links between practice and theory as both learners and teachers. We know it can be challenging for schools and teachers to implement this general capability, as critical thinking continues to predominate over creative thinking, often because of preconceived disciplinary differences. The essence of creative thinking is considered foundationally, often becoming an afterthought. Similarly, in ITE programs, rather than focussing on the design of the teacher education program and curriculum planning for explicit creative thinking possibilities, creativity and its possibilities remain dependent upon individual teacher educators' comfort or ability levels. Through praxis inquiry-based learning, we propose that our collaboratively developed PBCI rubric exemplar can serve as an agentic 'two-way' pedagogical tool for pre-service teachers as learners, and in-service teachers and students in schools to construct and organise knowledge about Critical and Creative Thinking. The PBCI rubrics become essential parts of the Creative Education Toolkit that connects to Harris' Creative Ecology model (Harris, 2016b ), including the Creativity Index, Whole-School Creativity Audit, Top 10 Creative skills and capacities and the Creative Ecology model (Fig. 1 ).

Creative ecology model (Harris, 2016b )

The Mitchell Institute's ( 2016 ) position paper on teacher education reform mentions creativity once and offers no practical way forward, either in schools or in university ITE programs:

Teachers...are integral to developing the capabilities of young people. Not only do teachers need to be able to develop students to have inquiring minds that can think critically and creatively, but these learning dispositions are critical for teachers to possess. (p. 3)

The Practice Principles for Excellence in Teaching and Learning ( 2017 ) in Victorian schools posits that “Teachers design learning programs to explicitly build deep levels of thinking and application. This is evident when the teacher: models and develops students' critical, creative and higher order thinking skills” (p. 22). Our collaborative work is based on this premise.

It began pre-pandemic with designing and developing a PBCI rubric to support and enable ITE students to contribute positively to the creative ecologies in their creative educational ecosystems, including placement schools and future employment sites. By focussing on the inter-relationships between teaching, learning, practices and assessing for Critical and Creative Thinking, we can avoid definitional skirmishes that frequently occur in disciplinary debates and highlight creative thinking skills. Therefore, we make it clear that ITE programs need to demonstrate how they teach, practice and assess Critical and Creative Thinking through an inquiry-based learning model that can be integrated into and across all disciplinary cultures and practices in education (including in the goal of transdisciplinary work). Australian ITE programs should better reflect the changing global educational landscapes that recognise critical and creative thinking as central to learning, teaching and assessment to ensure success-ready graduates in the pandemic and endemic.

Our collaborative ecological approach offers ITE pre-service teachers experience in considering both the theoretical underpinnings of the Critical and Creative Thinking general capability and practical, implementable strategies for approaching teaching, learning and assessment on their professional experience placements to combat the conflation of critical with creative as problematic. Central to the Creative Education Toolkit are the radical rubrics, designed to align with the NAPLAN testing years, scaffolding the skills to participate in and contribute to, developing a robust creative ecology within their future schools.

Harris' creative ecologies

Harris' formulation of a creative ecology model includes five domains that address elements in all areas of learning communities. Following Amabile and et al.'s ( 1996 ) development of valid ecological measures of creativity in workplace contexts, the Harris creative ecology heuristic follows a desire for “assessment of this complex interaction between a person's creativity and the environment” (Harris, 2016b , p. 85), in contrast to traditional approaches to fostering creativity which remains fixed solely on the individual. By drawing on Amabile's Work Environment Inventory, which assesses workplace environmental factors that are most likely to influence the expression and development of creative ideas, the Harris creative ecology model lends itself to a more environmental, collective approach to fostering creativity within the school (or any) community. This includes students, teachers, school leaders, administrators, practices, built and natural environments in and beyond the classroom, and appears in social, cultural, material and virtual spaces where teachers and students interact for the purposes of learning.

Approaching creativity in education as an ecology (de Bruin & Harris, 2017 ; Harris, 2018 ) engages learners and teachers in practices stimulated by relationships and interactions within their micro, macro and meta-worlds (see Fig. 1 ). Creative thought results from the cognitive, physical, emotional and virtual interaction between people, problems, situations and experiences triggered through affordances that allow such connectivity (McWilliam, 2010 ). A creative ecology demands a systems approach in which all elements of the ecology work in relation to one another, none in isolation. Harris' creative ecologies and the associated literature offer a beneficial framework for designing adaptable Creative Educational Toolkits.

Traditional assessments of creativity in education were primarily rooted in individual tasks of giftedness, talent and psychometric measures (Eysenck, 1996 ; Mayer, 1999 ; Runco & Mraz, 1992 ; Torrance, 1974 ). However, the creative ecologies approach recognises how an education site's people, practices and places are intertwined and connected, working in, out of and through each other—creating the conditions for creativity to thrive, rather than focussing on individual attributes. These ecological connections and conditions enable and allow each entity within the ecosystem to develop through interactions and flows, permeating barriers and discarding false binaries of 'inside' and 'outside', 'individual' and 'collective' activities. One benefit of approaching thinking ecologically is that it provides a framework to support learners and learning, alongside beginning teachers, through attention to the whole-school site, system and community.

A creative ecology model in ITE prepares teachers as future ready by learning about creative practice through practice (Darling-Hammond, et al., 2005 ). Underpinned by Harris' ( 2016b ) Creativity and Education , the creative ecologies approach fosters creativity through an interconnected, iterative approach across professional and disciplinary communities within the school and throughout the sector. Implementing this approach at the beginning of ITE programs, where creative and critical teaching and learning becomes a component of pre-service teachers' core work, centres creativity training regardless of subject or developmental stage (early childhood, primary or secondary). This cyclic program design creates an evaluative feedback loop where pre-service teachers move into the schooling sector with evidence of teaching, practising and assessing the Critical and Creative Thinking general capability as learners themselves.

Because the ecology model requires collaboration to provide the right conditions for integrated creative change, authentic inquiry-based learning designs could be implemented during placements, with mentoring from experienced teachers and university lecturers. The “creative ecological approach to whole-school change” (Harris, 2016b , p. 8) models the ACARA speculative and integrative Critical and Creative Thinking learning continuum that begins with imagination and wonderment. The capacity to learn, create and innovate combined with the capacity to initiate and sustain change are attributes that transfer across contexts. By creating the conditions for teachers to continue to develop critical and creative thinking skills as learners through practice, they adapt to a continually changing and dynamic profession. We believe that developing pre-service teachers' creative and critical thinking skills and capacities through an ecological approach demands effective collaboration, enhancing the school community's unity and providing peer-sustained embedded professional development as part of everyday practice.

Radical Rubrics as important components of a diversified toolkit

We commenced this project as a group of practitioners and researchers: educators experienced in the field of Initial Teacher Education. In forging this collaborative laboratory ('collaboratory') for addressing creative assessment, it was necessary—as a starting point—that we held similar beliefs about the influence of ITE and shared values about the transformative power of creativity. A deep understanding of creativity in education was also common amongst the co-authors, all having employed creative approaches in education at various levels and across multiple learning areas. Approaching this work as both artists and educators was integral to understanding criticality and creativity, inter-, multi- and transdisciplinary and diverse approaches to creativity within the curriculum and beyond.

The remainder of this article explains how we as a collaboratory developed these radical rubrics against the Australian Curriculum General Capability against the USA Common Core Standards (CCSS) and the OECD Learning Framework 2030 (OECD, 2018 ), which share considerable overlap in identifying a need for fostering creative capacities.

While the Australian standards set grade-specific goals, they do not define how the standards should be taught or which materials should be used to support students, and the supports that effectively enhance creative and critical thinking through CCSS aligned Creativity & Innovation Rubrics (Kingston, 2018 ) have also been considered. The OECD Learning Framework 2030 (OECD, 2018 ) articulates learner qualities beyond epistemic and procedural knowledge, and cognitive and social skills. That schema reinforces the need to develop attitudes and values that (in preparing for 2030 and beyond) should enable learners to:

…think creatively, develop new products and services, new jobs, new processes and methods, new ways of thinking and living, new enterprises, new sectors, new business models and new social models. Increasingly, innovation springs not from individuals thinking and working alone, but through cooperation and collaboration with others to draw on existing knowledge to create new knowledge. The constructs that underpin the competency include adaptability, creativity, curiosity and open-mindedness. (OECD, 2018 , p. 5)

Our inquiry-based learning model integrates elements of the CSSS, the OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030 ( 2018 ) and the Australian Curriculum. We have developed and designed radical rubrics for teaching, practising and assessing processes, and to instrumentalise the key ideas of the four interrelated elements in the Critical and Creative Thinking learning continuum:

The radical rubric design was developed to be used in alternate years from the current NAPLAN tests in Years 5, 7 and 9. We link this system of creativity measurement to Australian NAPLAN tests to build an Australian national creativity measure alongside the literacy and numeracy measures in the current NAPLAN testing regime. In December 2022, the PISA 2021 Assessment of Creative Thinking results will be published. They will elevate the recognition of creative thinking (and doing) as a core literacy alongside literacy and numeracy, underlining further focus on creativity assessment at a global scale (Bouchie, 2019 ).

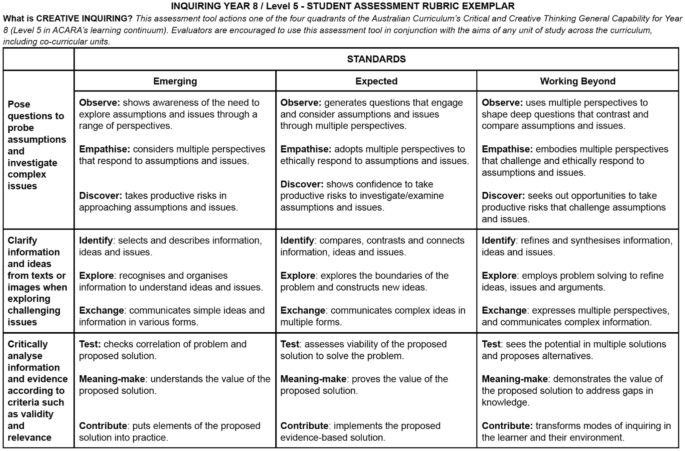

While we recognise that tensions exist across Australian states between implementing a national curricular capability into localised state agendas responsible for implementation, we have designed this overarching assessment strategy through PBCI rubrics (Fig. 2 ) useful for schools across the nation. The radical rubric and Creative Education Toolkit approach reflects our belief that the most effective way to design and develop Critical and Creative Thinking as an essential component of all learning in Australia is by aligning with yearly national assessment years via NAPLAN, and within ITE programs, where pre-service teachers develop knowledge and experiences of curriculum, pedagogy and policy—in addition to the PISA tests, which only occur every three years for member nations.

Description of assessment rubric quadrants https://doi.org/10.26188/14736660

This radical rubric may be used as a capstone or foundational tool in ITE programs to foster assessment of creativity through practice; however, it can also be used individually or collectively within a school- or university-based ecological model. As Moss, et al. ( 2019 ) agree, the “general capabilities need to be targeted explicitly within the assessment criteria or learning goals when integrated approaches are used” (p. 35). By offering this more flexible approach to creativity assessment, this rubric allows students, pre-service teachers and early-career teachers to engage in meaningful creative inquiry-based learning that has both individual and collaborative benefits for the whole-school creative ecology.

The radical rubrics within the Creative Education Toolkit act as an iterative tool through which learners design, develop and review their inquiry. The rubric as an agentic tool allows the merging of learning experiences with ongoing engagement and collaboration. It offers learners (teacher educators and pre-service teachers and in-service teachers with students) to construct and organise knowledge themselves, engage in detailed research, inquiry, writing and analysis, and communicate effectively to audiences. Leadbeater (2008) argues that the successful reinvention of educational systems worldwide depends on transforming pedagogy and redesigning learning tasks. Promoting learner autonomy and creativity through inquiry learning within ITE programs is part of the solution. The Mitchell Institute ( 2016 ) note this approach:

…highlights the increasing duality of the modern teacher – that of both teacher and learner. It also suggests that 21st century teachers will be unable to navigate the modern educational workplace without the skills and dispositions that enable them to focus on their own learning and improvement. (p. 3)

Proposition: a model for teaching, practising and assessing Critical and Creative Thinking

The next section introduces a radical rubric that promotes teaching, practising and assessing creativity and critical thinking in ways that move beyond binaries such as 'standardised' and 'creative' instead of an imaginative, empathetic and inquiry-focussed interdisciplinary assessment tool. Our 'sleight-of-hand' in offering what may at first seem like a capitulation to standardised assessment is the kind of tool that can serve both or, as Maxine Greene argued, offer an imaginative approach that can work within simple standardisation “to combat standardardization” ( 1995 , p. 380). We focus on PBCI rubrics within the Creative Education Toolkit as common ways to explore learning design for authentic inquiry-based tasks. They can be designed to create a backward mapping of the task and offer learners a way into the processes and reflective practices involved in ideation, problem posing, visioning and wondering about things rather than focussing on a preconceived product of learning or the content. They support “teachers who recognize the important role of imagination and creative play in the learning process, [and] want to include these higher-level thought processes as part of authentic assessment” (Young, 2009 , p. 74). Our rubric design offers teachers new ways to reinforce creative practices and processes learned in ITE programs that can be supplemented by ongoing professional development in schools where creativity and critical thinking become observable, teachable and assessable.

Rubrics such as this exemplar can be deployed in Years 6, 8 and 10 (the interstitial years between NAPLAN testing in Years 5, 7 and 9) as part of a networked ecological approach to fostering creativity in educational settings (Harris, 2018 ). Using flexible and adaptable process rubrics allows teachers and learners to negotiate creative practices across various needs and sites. The ecological approach to creativity education (reflected in the radical rubric) invites teachers, students and school leaders to foster creativity in a whole environment but interconnected manner across the entire ecosystem within which learning takes place. Teachers traditionally interpret curriculum documents and apply pedagogies to facilitate learning via the transmission of knowledge and engagement in specific activities to that subject and particularly to that individual teacher. This rubric's interconnected and cross-curricular application allows teachers and students to find connectivities between and across domains and dismantle the siloed information transfer systems that occur within prevailing strict procedural frameworks of content, resources, timelines and assessment/reporting. As a learning and teaching tool, a PBCI rubric such as ours allows for the mental and psychological linking across a whole school that enables students, teachers and leaders to think and act on ideas and situations (Cowan, 2006 ). As an assessment tool, the radical rubric design stimulates imagination, ideation, wondering and possibility thinking, and synthesis and integrative thinking that enables all ecology members to contribute to each school's unique creative needs and resources.

The rubric is described in Fig. 2 ( https://doi.org/10.26188/14736660 ) and provides the framework for implementation. The rubric relies on the inclusion of four quadrants consistent with those specified in the General Capabilities in the Australian Curriculum and cross-referenced with the criteria in the OECD study, “Fostering and assessing creativity and critical thinking in education” (Vincent-Lancrin, et al., 2019 ). The quadrants are inquiring, generating, analysing and reflecting. The descriptors offer clarification of how the quadrant would be demonstrated in practice. The description deliberately remains free of learning area content to encourage transferability across disciplines.

Figure 3 ( https://doi.org/10.26188/14736576 ) provides an example of the achievement standards for the first quadrant of inquiring. We have developed the achievement standards as suggested indicators of student levels of learning. There are three criteria presented against the standards of emerging, expected and working beyond. Each descriptor provides examples of the levels of learning achieved and outlined with an active verb to allow an evaluator to decide the level of achievement and generate appropriate feedback loops. In the context of this creative inquiry rubric, the evaluation can be conducted by a teacher or student (peer) and completed at various stages within a task.

Assessment rubric standards and descriptors https://doi.org/10.26188/14736576

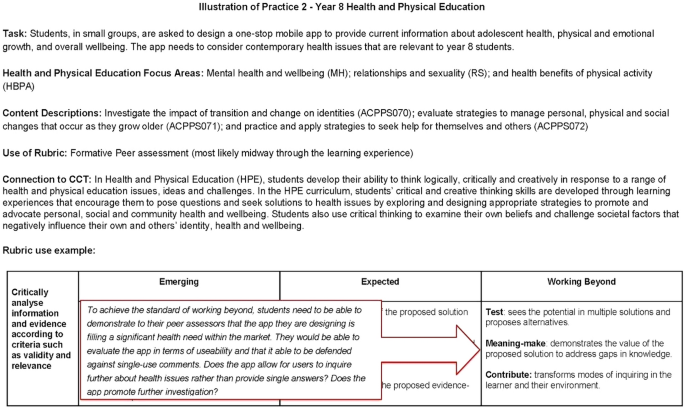

The rubric provides illustrations of practice that enable teaching staff to consider potential implementation ideas. Figure 4 ( https://doi.org/10.26188/14730429 ) provides an example of a Year 8 Geography task. The example provides a brief description of the assessable task and how it would align topic areas and content description. The content description in focus is derived from the Australian Curriculum. The connection to the Critical and Creative Thinking general capability is also included to highlight the existing policy documents and how these may be taught, assessed and practiced. Further description of what the achievement standard might look like is included to guide the correlation between the PBCI rubric, the task and the demonstrable critical and creative skills being assessed. Naturally, additional criteria could be incorporated based on the assessable task's localised school and class needs.

Illustration of practice 1 (year 8 geography) https://doi.org/10.26188/14730429

The second illustration of practice is included in Fig. 5 ( https://doi.org/10.26188/14736843 ). It emphasises how the PBCI rubric might be used for peer learning and review. In this example, an accessible task from the learning area of Health and Physical Education is outlined within a specified focus on content found in the Australian Curriculum. Again, the relevant information about the connections to the general capability of Critical and Creative Thinking is outlined. In this example, the suggestion is that the rubric be used midway through the learning experience, with other students as the peer reviewers. The annotation on the rubric offers further exploration of what may be required to achieve a particular level of learning (in this example, 'working beyond').

Illustration of practice 2 (year 8 health and physical education) https://doi.org/10.26188/14736843

Conclusions and implications for ITE

This paper has explored how and why our collaboratory developed a flexible and responsive PBCI rubric exemplar for teaching, learning and assessing creativity to work within Harris' Creative Education Toolkit. We began this work by asking, 'how do early career teachers develop and maintain the ability to design interdisciplinary future-focussed creative learning and teaching? Where do early career teachers develop curriculum integration skills and capacities as practitioners?' This is an important time to share our praxis approach as educators worldwide face new post-pandemic challenges requiring teachers to design creative, critical, often-digital, inquiry-based learning encounters for young people. Being radical, creative and critical through a critical praxis model that challenges teaching, learning and assessment education, rather than standardising creativity in education, is needed now more than ever. Our radical rubric design provides a model for cultivating and assessing critical and creative thinking across the ecology. This kind of active feedback-feedforward loop through an inquiry model, also understood as curriculum “as praxis” (Grundy, 1987 , p. 15) contributes to better practices across ITE through two-way pedagogies. Ultimately, the approach encourages ground-up creative changes in education policy.

The approach outlined in this paper suggests moving creative change in schools and ITE programs away from teacher-driven activities to co-activating problem posing as a collaborative creative practice that initiates and sustains learning through creative inquiry. The radical rubric design effectively and efficiently initiates and cultivates Critical and Creative Thinking as a general capability in ITE (and by extension into schools and classrooms). The model explored in this article is just one of the Toolkit rubrics that we propose as a set of radical interventions, which together establish more processual and accessible creative practices in learners and across whole-school creative ecologies. As such, ITE holds the potential to activate substantial and sustainable critical and creative thinking development in pre-service and early-career teachers and apply generational mindset change in all learners, by effectively developing and evolving creative communities of practice.

Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 39 (5), 1154–1184.

Article Google Scholar

Arnold, J., Edwards, T., Hooley, N., & Williams, J. (2012). Conceptualising teacher education and research as “critical praxis.” Critical Studies in Education, 53 (3), 281–295.

Arnold, J. & Mundy, B. (2020). Praxis pedagogy in teacher education. Smart Learning Environments . https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-020-0116-z

Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER). (2016). Literacy and numeracy test for initial teacher education . https://teacheredtest.acer.edu.au/

Australian Curriculum (ACARA). (2016). Australian national curriculum . https://www.acara.edu.au/curriculum

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). (2018). National review of teacher registration . https://www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/national-review-of-teacher-registration

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). (2019). Accreditation standards and procedures. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/deliver-ite-programs/standards-and-procedures

Barnes, J., & Shirley, I. (2007). Strangely familiar: Cross-curricular and creative thinking in teacher education. Improving Schools, 10 (2), 162–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480207078580

Beghetto, R. A., Kaufman, J. C., & Baer, J. (2014). Teaching for creativity in the common core classroom . Teachers College Press.

Bouchie, Sarah. (2019). Teaching creative thinking in schools--PISA 2021 will offer some clues . https://www.legofoundation.com/en/learn-how/blog/teaching-creative-thinking-in-schools-pisa-2021-will-offer-some-clues/

Chiam, C. L., H. Hong, F. H. K. Ning, and W. Y. Tay. (2014). Creative and critical thinking in Singapore schools. NIE Working Paper Series No. 2. http://www.nie.edu.sg/docs/default-source/nie-working-papers/niewp2_final-for-web_v2.pdf?sfvrsn=2

Cowan, J. (2006). How should I assess creativity? In N. Jackson, M. Oliver, M. Shaw, & J. Wisdom (Eds.), Developing creativity in higher education: An imaginative curriculum (pp. 156–172). Routledge.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). Research on teaching and teacher education and its influences on policy and practice. Educational Researcher, 45 (2), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X16639597

Darling-Hammond, L., Hammerness, K., Grossman, P., Rust, F., & Shulman, L. (2005). The design of teacher education programs. In L. Darling-Hammond, K. Hammerness, P. Grossman, F. Rust, & L. Shulman, (Eds.), Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do (pp. 390–441). Wiley

de Bruin, L. R., & Harris, A. (2017). Fostering creative ecologies in Australasian secondary schools. Australian Journal of Teacher Education (online), 42 (9), 23.

Department of Education, Taiwan. (DOET). (2014). Education in Taiwan . Taiwan Ministry of Education. https://www.taiwan.gov.tw/content_9.php

Education Council. (2019). Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education declaration. https://www.dese.gov.au/alice-springs-mparntwe-education-declaration/resources/alice-springs-mparntwe-education-declaration

Eysenck, H. J. (1996). The measurement of creativity. In M. A. Boden (Ed.), Dimensions of creativity (pp. 208–209). MIT Press.

Farrell, L., & Corbel, C. (2017). Literacy events in the gig economy [online]. Fine Print, 40 (3), 3–7.

Google Scholar

Flew, T., & Cunningham, S. (2010). Creative industries after the first decade of debate. Information Society, 26 , 1–11.

Freire, P. (1972). Cultural action for freedom . Penguin.

Government of Western Australia (GWA). (2018). Schools curriculum and Standards Authority. https://k10outline.scsa.wa.edu.au/home/teaching/general-capabilities-over/critical-and-creative-thinking/introduction/scope-of-critical-and-creative-thinking

Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the imagination: Essays on education, the arts, and social change . Jossey-Bass.

Grundy, S. (1987). Curriculum: Product or praxis? Falmer Press

Harris, A. (2014). The creative turn: Toward a new aesthetic imaginary. Sense Publishers.

Harris, A. (2016a). Creative ecologies: Fostering creativity in secondary schools . http://creativeresearchhub.com

Harris, A. (2016b). Creativity and education . Palgrave Macmillan.

Harris, A. (2018). Creative agency / creative ecologies. In K. Snepvangers, P. Thomson, & A. Harris (Eds.), Creativity policy, partnerships and practice in education (pp. 65–88). Palgrave Macmillan.

Harris, A., & Ammerman, M. (2016). The changing face of creativity in Australian education. Teaching Education, 27 (1), 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2015.1077379

Kingston, S. (2018). Project Based Learning & Student Achievement: What Does the Research Tell Us? PBL Evidence Matters, 1 (1), 1–11.

Knorr Cetina, K. (2007). Culture in global knowledge societies: Knowledge cultures and epistemic cultures. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 32 (4), 361–375.

Lassig, C. (2019). Creativity talent development: Fostering creativity in schools. Handbook of giftedness and talent development in the Asia-Pacific (pp. 1–25). New York: Springer.

Learning Policy Institute & Turnaround for Children. (2021). Design principles for schools: Putting the science of learning and development into action. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/sold-design-principles-report

Lucas, B., Claxton, G., & Spencer, E. (2013). Progression in student creativity in school: First steps towards new forms of formative assessment. (OECD Education Working Papers, No. 86). OECD Publishing.

Magnussen, L., Ishida, D., & Itano, J. (2000). The impact of the use of inquiry-based learning as a teaching methodology on the development of critical thinking. Journal of Nursing Education, 39 (8), 360–364. https://doi.org/10.3928/0148-4834-20001101-07

Mayer, R. E. (1999). Fifty years of creativity research. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 449–460). Cambridge University Press.

McCarty, S. (2020, May). Post-pandemic pedagogy. Journal of Online Education. New York University.

McWilliam, E. (2010). Learning culture, teaching economy. Pedagogies: An International Journal , 5 (4), 286–297.

Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs (MCEETYA). (2008). The Melbourne declaration on educational goals for young Australians http://www.curriculum.edu.au/verve/_resources/National_Declaration_on_the_Educational_Goals_for_Young_Australians.pdf

Mitchell Institute. (2016). Response to working together to shape teacher education in Victoria . Discussion paper (September 2016). http://vuir.vu.edu.au/33661/1/Response-to-Working-Together-to-Shape-Teacher-Education-in-Victoria.pdf

Moss, J., Godinho, S. C., & Chao, E. (2019). Enacting the Australian Curriculum: Primary and secondary teachers' approaches to integrating the curriculum. Australian Journal of Teacher Education . https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v44n3.2

NESA. (2018). Education standards New South Wales. http://educationstandards.nsw.edu.au/wps/portal/nesa/k-10/understanding-the-curriculum/curriculum-syllabuses-NSW

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2018). The future of education and skills: Education 2030. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030/E2030%20Position%20Paper%20(05.04.2018).pdf

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2019). PISA 2021 Creative thinking framework. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/PISA-2021-creative-thinking-framework.pdf

Parliament of Australia. (2016). The Australian Government's Standing Committee on Employment, Education and Training's Inquiry into innovation and creativity: Workforce for the new economy . https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House/Employment_Education_and_Training/Innovationandcreativity

Parliament of Australia. (2019). Status of the teaching profession. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House/Employment_Education_and_Training/TeachingProfession

Queensland Government. (2018). Every student succeeding, State Schools Strategy 2018–2022. https://education.qld.gov.au/curriculums/Documents/p12-carf-framework.pdf

Reeves, B. (2021). Assessing ethical capability: A framework for supporting teacher judgement of student proficiency. The Australian Educational Researcher , 1–26.

Richardson, C., & Mishra, P. (2018). Learning environments that support student creativity: Developing the SCALE. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 27 , 45–54.

Runco, M. A., & Mraz, W. (1992). Scoring divergent thinking tests using total ideational output and a creativity index. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 52 , 213–221.

Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group Report. (2014). Action now—Classroom ready teachers. action_now_classroom_ready_teachers_accessible-(1)da178891b1e86477b58fff00006709da.pdf (aitsl.edu.au)

Torrance, E. P. (1974). Torrance tests of creative thinking . Personnel Press.

VCAA. (2016). Victorian curriculum. http://victoriancurriculum.vcaa.vic.edu.au

Victoria. Department of Education and Training, author, issuing body. (2017). Practice principles for excellence in teaching and learning: Draft version 1 http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-607567621

Vincent-Lancrin, S., Gonzalez-Sancho, C., Bouckaert, M., de Luca, F., Fernandez-Barrerra, M.-F., Jacotin, G., Urgel, J., & Vidal, Q. (2019). Fostering students’ creativity and critical thinking: What it means in school . OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/62212c37-en

Walsh, M. (2010). Multimodal literacy: What does it mean for classroom practice? Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 33 (3), 211–239.

Young, L. (2009). Imagine creating rubrics that develop creativity. The English Journal, 99 (2), 74–79.

Download references

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia

Dan Harris, Kathryn Coleman & Peter J. Cook

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kathryn Coleman .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Harris, D., Coleman, K. & Cook, P.J. Radical rubrics: implementing the critical and creative thinking general capability through an ecological approach. Aust. Educ. Res. 50 , 729–745 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00521-8

Download citation

Received : 26 February 2021

Accepted : 22 March 2022

Published : 20 April 2022

Issue Date : July 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00521-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Critical and creative thinking

- Creative ecology, praxis

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

This page uses technologies your browser does not support.

Many of our new website's features will not function and basic layout will appear broken.

Visit browsehappy.com to learn how to upgrade your browser.

- university of new orleans

- general education

- evaluation rubrics

- critical thinking rubric

Critical Thinking Rubric

This rubric is designed to evaluate the extent to which undergraduate students evaluate claims, arguments, evidence, and hypotheses.

Results will be used for program improvement purposes only.

Download the Critical Thinking Rubric (PDF version)

Skip to Content

English alum flunks grades in new book

- Share via Twitter

- Share via Facebook

- Share via LinkedIn

- Share via E-mail

Jesse Stommel compiles two decades of eyebrow-raising in Undoing the Grade: Why We Grade, and How to Stop

It was the summer of 2023, sometime in June or July, and Jesse Stommel (PhD, English ‘10) had big weekend plans.

He said to his husband, “I’m going to write a book this weekend”—a book about grades, in particular, and all the trouble they’ve caused.

It was a tall order for such a short period of time, no doubt, but it wasn’t as though Stommel were starting from scratch. He’d been taking a critical eye to grades for two decades and had published numerous essays on the topic, several of which had been read by tens of thousands of people on his website .

Jesse Stommel (PhD, English ‘10) Undoing the Grade: Why We Grade, and How to Stop partially in response to his realization that grades are performative.

“I was already starting to piece these things out in public and have conversations,” says Stommel, who teaches writing at the University of Denver. “That’s how my writing process always works. All of my books are adapted from previously published stuff. This is because I don't think in a vacuum. I need to think alongside other people.”

All Friday, Saturday and Sunday, Stommel toiled away, editing previously published materials, organizing those materials into chapters, writing three brand-new chapters and then bookending everything with a foreword by Martha Burtis and an afterword by Sean Michael Morris (MA, English ‘05).

“And come Sunday night,” he says, “I had a draft of the book.”

That book, titled Undoing the Grade: Why We Grade, and How to Stop , was published on Aug. 14.

I can give you A’s

Growing up, Stommel loved school. Grades, however—grades he didn’t love.

“I did really well throughout elementary school. I was super engaged,” he says. “Then I hit middle school, where I was being graded in the traditional way for the first time, and I got almost straight D’s and F’s in sixth grade.”

His grades improved the following year, but not by much. Being graded had sapped him of his motivation, he says. “All of a sudden I didn’t want to do any of the work.”

But things changed in eighth grade, thanks to his dad and brother.

“They bet me I couldn’t get straight A’s,” he says. “And so, the first semester of eighth grade, I got straight A’s.”

His teachers couldn’t believe it. They were flummoxed, and perhaps a little suspicious. How could he turn things around so quickly? What on earth was going on?

“They sat me down and asked me what had happened, and I told them about the bet,” says Stommel.

Yet that meeting opened his eyes more than it did his teachers’, he says, because it led him to the realization that grades were performative, character traits of a role he was being asked to play. “If what you want is A’s,” he recalls thinking, “I can give you A’s.”

This discovery, and the good grades that arose therefrom, freed Stommel up, he admits, relieving him of the pressure and judgment that often came with D’s and F’s. But it also made him aware of the stakes involved in the pursuit of high marks, stakes he continues to think about to this day.

“Whenever I see a perfect grade point average, what that represents to me is a willingness to compromise yourself, because that's what we're constantly expected to do in traditional grading systems.”

“Whenever I see a perfect grade point average, what that represents to me is a willingness to compromise yourself, because that's what we're constantly expected to do in traditional grading systems,” says Jesse Stommel.

From grader to ungrading

Stommel began his teaching career as a grader, evaluating the work a professor had assigned to students.

“The experience of doing nothing but grading gave me an interesting perspective on what grading is and how it works,” he says. “It had nothing to do with the relationship between me and students. It was just this abstraction of their work and the quality of their work, as though that can be separated from who they are and who I am.”

Stommel wanted to do something different when he became an instructor of record. But what?

His first source of inspiration was CU Boulder English Professor Marty Bickman , who taught Stommel a total of four times, twice when Stommel was an undergraduate and twice when he was a graduate student.

“I really admired Marty’s approach. He didn’t put grades on individual work. Instead, he had students grading themselves and writing self-reflections.”

Stommel also found inspiration in CU Boulder English Professor R L Widmann , with whom he co-taught courses on Shakespeare. Widmann encouraged Stommel to think of assessment not as a judgment laid down from on high but as a conversation between student and teacher.

“She would develop deep relationships with students and then be able to tell them exactly what they needed to hear at exactly the moment they needed to hear it. And they trusted her.”

Stommel combined Bickman’s and Widmann’s approaches in his own classes, along with what he learned about teaching and learning from books like John Holt’s How Children Fail and Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed . And thus ungrading, which Stommel defines as “raising an eyebrow at grades as a systemic practice,” was born.

But that’s not to say Stommel believes his ungrading practice is the only viable option. Not even close. In his essay “How to Ungrade,” a revised and expanded version of which appears in Undoing the Grade , he provides a smorgasbord of options for the ungrading-curious, including grading contracts, portfolios, peer assessment and student-made rubrics.

The goal of ungrading, he says, is not to replace one uniform approach to assessment with another. It’s for educators to develop an approach that best fits them and their students.

“The work of teaching, the work of reimagining assessment, is necessarily idiosyncratic.”

Myths and paradoxes

But in a world without grades, wouldn’t academic standards fall? Wouldn’t students lose motivation? Wouldn’t they be rewarded for learning less?

The experience of doing nothing but grading gave me an interesting perspective on what grading is and how it works. It had nothing to do with the relationship between me and students. It was just this abstraction of their work and the quality of their work, as though that can be separated from who they are and who I am.”

Questions like these, Stommel says, reflect the cultural anxiety surrounding grades. And while it’s important to remember that this anxiety is itself real—“It’s based in real feelings that we have as human beings,” says Stommel—it’s equally important to remember that the problems from which it stems may not be.

Take grade inflation, or the awarding of higher grades for the same quality of work over long periods of time, as an example. Like Alfie Kohn , author of Punished by Rewards , Stommel calls grade inflation a myth, but he also believes concern over it points to a real phenomenon: the desire for education to be taken seriously.

“We're seeing all kinds of pushes on the education sector,” he says. “People are saying that education isn't doing what it's supposed to be doing, or it’s actually doing harm.”

That many teachers’ jobs lack stability, especially in higher education, doesn’t help, Stommel adds.

“When you see the utter precarity of educators—where most educators are not making a living wage; where 70% of educators in higher education are adjunct or on one-year contracts, sometimes even on one-semester contracts. When you see all of that happening, there is a desire to have some relief. And I think that’s when we talk about something like grade inflation.”

Nevertheless, Stommel argues, the claim that lower grades means better teaching is a misleading one. High standards and high grades are not mutually exclusive.

Stommel cites a former student to prove it. “Jesse’s class was one of the hardest I’ve taken in my life,” this student wrote of one of Stommel’s classes. “It was an easy ‘A.’”

Did you enjoy this article? Subcribe to our newsletter. Passionate about English? Show your support.

Related Articles

Making movies that people love watching

The Loch Ness monster: myth or reality?

Employer-labor relations in the balance

- Division of Arts and Humanities

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Code §4.28(2021)). Further, the Association of American Colleges & Universities' Critical Thinking VALUE Rubric defines critical thinking as "a habit of the mind characterized by the comprehensive exploration of issues, ideas, artifacts, and events before accepting or formulating an opinion or conclusion.".

The rubric provides criteria and performance descriptors for evaluating and discussing critical thinking in undergraduate courses. It covers issue exploration, evidence selection, influence of context and assumptions, position and conclusion, and related outcomes.

VALUE Rubrics - Critical Thinking. The VALUE rubrics were developed by teams of faculty experts representing colleges and universities across the United States through a process that examined many existing campus rubrics and related documents for each learning outcome and incorporated additional feedback from faculty.

Critical thinking is a habit of mind characterized by the comprehensive exploration of issues, ideas, artifacts, and events before accepting or formulating an opinion or conclusion. Framing Language This rubric is designed to be transdisciplinary, reflecting the recognition that success in all disciplines requires habits of inquiry and analysis ...

Microsoft PowerPoint - Designing Rubrics to Assess Critical Thinking.pptx. 3:00. Traditional assessment measures such as multiple choice questions are a form of selected response measures designed for knowledge recall and sometimes for decision‐making from a selection of options. In such measures, students are asked to think critically in the ...

Critical thinking rubric. Critical thinking can be broadly defined in different contexts, but we found that the categories included in the rubric (Fig. 2) represented commonly accepted aspects of critical thinking (Danczak et al., 2017) and suited the needs of the faculty collaborators who tested the rubric in their classrooms.

2021 Critical Thinking Rubric: Grades 3-5. 2021 Critical Thinking Rubric: Grades 6-12. These research-based rubrics are designed to provide useful, formative information that teachers can use to guide instruction and provide feedback to students on their overall performance. Students can also use the rubrics to reflect on their own learning.

The Creative Thinking VALUE Rubric is intended to help faculty assess creative thinking in a broad range of transdisciplinary or interdisciplinary work samples or collections of work. The rubric is made up ofa ... CRITICAL THINKING PART 2: INQUIRY & ANALYSIS VALUE RUBRIC

When used consistently, this Intellectual Standards Rubric for Critical Thinking (ISRCT) provides regular and specific insight to students about strengths and weaknesses, related to critical thinking, that are reflected in their work. The ISRCT can also be used to assess multiple components of the same assignment, which allows instructors to ...

DEVELOPMENT OF CRITICAL THINKING RUBRIC. Definition: Critical thinking is a habit of mind characterized by the comprehensive exploration of issues, ideas, artifacts, and events before accepting or formulating an opinion or conclusion. The capacity to combine or synthesize existing ideas, images, or expertise in original ways; thinking ...

Adapted for George Mason University from the AAC&U Critical Thinking VALUE Rubric by the Critical Thinking Faculty Learning Community June, 2010; Revised June 20 14 Developing the Critical Thinker This criterion is best thought of as a precondition for the development of specific critical thinking competencies as articulated in the remainder of ...

The rubric articulates fundamental criteria for each learning outcome, with performance descriptors demonstrating progressively more ... If insight into the process components of critical thinking (e.g., how information sources were evaluated regardless of whether they were included in the product) is important, assignments focused on student ...

Simplified Rubric for Assessing CRITICAL & ANALYTICAL THINKING Details Behind Simplified Rubric Novice Developing Proficient Critical and Analytical Thinking: Students will comprehensively explore issues, ideas, artifacts, and events before accepting or formulating opinions or conclusions. Student demonstrates some awareness of assumptions when

Critical thinking is a habit of mind characterized by the comprehensive exploration of issues, ideas, artifacts, and events before accepting or formulating an opinion or conclusion. Framing Language This rubric is designed to be transdisciplinary, reflecting the recognition that success in all disciplines requires habits o f inquiry and ...

This article details how and why we have developed a flexible and responsive process-based rubric exemplar for teaching, learning, and assessing critical and creative thinking. We hope to contribute to global discussions of and efforts toward instrumentalising the challenge of assessing, but not standardising, creativity in compulsory education. Here, we respond to the key ideas of the four ...

Critical thinking is a habit of mind characterized by the comprehensive exploration of issues, ideas, artifacts, and events before accepting or formulating an opinion or conclusion. Framing Language This rubric is designed to be transdisciplinary, reflecting the recognition that success in all disciplines requires habits o f inquiry and ...

Developing Critical Thinking Skills: The Key to Professional Competencies. A tool kit. Sarasota, FL: American Accounting Association. Skills in the Scoring Manual for the Reflective Judgment Interview Rubrics Based on a Model of Open-Ended Problem Solving Skills: Steps for Better Thinking Rubric Steps for Better Thinking Competency Rubric

Critical thinking is a habit of mind characterized by the comprehensive exploration of issues, ideas, artifacts, and events before accepting or formulating an opinion or conclusion. Framing Language . This rubric is designed to be transdisciplinary, reflecting the recognition that success in all disciplines requires habits o f inquiry and ...

Using the Holistic Critical Thinking Scoring Rubric. 1. Understand What this Rubric is Intended to Address. Critical thinking is the process of making purposeful, reflective and fair‐minded judgments about what to believe or what to do. Individuals and groups use critical thinking in problem solving and decision making.

Critical Thinking Rubric. This rubric is designed to evaluate the extent to which undergraduate students evaluate claims, arguments, evidence, and hypotheses. Results will be used for program improvement purposes only. Download the Critical Thinking Rubric (PDF version) Course: Instructor: Student: Date: Component.

Critical thinking is a habit of mind characterized by the comprehensive exploration of issues, ideas, artifacts, and events before accepting or formulating an opinion or conclusion. Framing Language This rubric is designed to be transdisciplinary, reflecting the recognition that success in all disciplines requires habits o f inquiry and ...

Four-Point Rubric. 4 = High level excellence in evidence of critical thinking ability and performance at the college level. 3 = Demonstrable, competent, expected evidence of critical thinking ability and performance at the college level. 2 = Minimally acceptable, inconsistent evidence of critical thinking ability and performance at the college ...

The average pairwise adjacent agree-ment scores were 89% for critical thinking and 92% for information processing for this assignment. However, the exact agreement scores were much lower: 34% for critical thinking and 36% for information processing. In this case, neither rater was an expert in the content area.

Join the Teaching, Learning and Technology Center on Thursday, June 6, for an immersive and dynamic day focused on new approaches to assessment. The remote, full-day workshop series will delve into various topics, including the art of designing engaging video and digital story assignments; harnessing the power of ePortfolios to showcase student learning; exploring how to incorporate AI ...

He'd been taking a critical eye to grades for two decades and had published numerous essays on the topic, ... "If what you want is A's," he recalls thinking, "I can give you A's." ... peer assessment and student-made rubrics. The goal of ungrading, he says, is not to replace one uniform approach to assessment with another. It's ...