- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Surveys

Personality Survey: Top 25 Questions, Types, Steps & Tips

5 steps to design a good personality surveyPersonality surveys have become a powerful tool for understanding human behavior, personality tests, traits, research, and preferences.

Whether used in academic research, organizational settings, personal careers or personal development, A personality test provides a structured approach to measure the complexities of a personality test.

A personality survey is a systematic assessment that measures various aspects of an individual’s personality test, including traits, career, future, attitudes, and behaviors.

LEARN ABOUT: Survey Mistakes And How to Avoid

These surveys help individuals gain self-awareness, identify strengths and weaknesses, and explore areas for personal growth and future.

Personality surveys facilitate effective team-building, personality tests, reliability, talent selection, and career development initiatives in organizational contexts.

LEARN ABOUT: Testimonial Questions

What is a Personality Survey?

A personality survey is defined as a survey that consists of multiple question types that aim to collect insights into the personality of respondents or tests. This survey is mostly introspective that measures life reports in the form of rating scales by using a questionnaire . The data collection from a personality survey provides insights into a human-being and the decision making process as well as the rationale behind that process.

These personality test survey questions are used in the survey software to help distinguish ability from personality. It primarily helps to understand how you relate with others feelings, approach your problems, deal with feelings and understand your personal life.

Surveys have uses in multiple fields but the primary use is in a professional environment where a prospective employee is administered this online survey to gauge temperament, decision making process, business acumen etc. It helps in understanding how motivated to work hard and driven an employee is and the factors that drive the individual.

The other times a personality test survey is used to self-introspect, to match compatibility, assess theories, determine in work, evaluate change in a person after a certain process, diagnosing psychological problems, student evaluation and also sometimes in forensic settings. A student interest survey helps customize teaching methods and curriculum to make learning more engaging and relevant to students’ lives.

Learn more: Personality Survey Questions + Sample Questionnaire Template.

Personality Survey Types

Several types of personality surveys are commonly used to assess and understand individuals’ personalities. Here are some recognized personality type surveys:

Myers Briggs Type Indicator:

Myers Briggs personality test is a widely used personality test or assessment that categorizes individuals into 16 different personality types based on preferences in four key areas: extraversion/introversion, sensing/intuition, thinking/feeling, and judging/perceiving. Myers Briggs test provides valuable insights into how individuals perceive the industries, make decisions, and interact with others. It’s important to note that while the Myers Briggs Type Indicator can offer valuable insights, the Myers Briggs test is just one tool among many for understanding human personality and has its limitations.

Big Five Personality Traits:

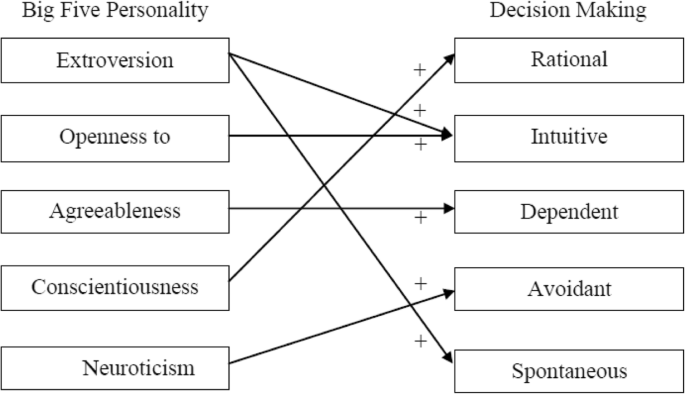

The Big Five system assesses personality test across five dimensions, including openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. These traits provide a broad framework for understanding personality variation.

DISC Assessment:

The DISC assessment categorizes individuals into four primary behavioral styles: dominance, interest, influence, steadiness, and conscientiousness. It helps identify how individuals interact, communicate, and respond in various situations.

The Enneagram test is a typing system that helps to describe nine interconnected personality types of research, each associated with distinct motivations, fears, and coping mechanisms. It provides a deeper understanding of an individual’s core desires and fears.

Hogan Personality Inventory:

The HPI assesses personality traits related to social effectiveness, work approach, and interpersonal interactions. It provides insights into an individual’s typical behavior patterns and potential strengths and challenges in the workplace.

StrengthsFinder:

The StrengthsFinder assessment test identifies an individual’s top strengths from 34 talent themes. It focuses on identifying and leveraging an individual’s natural talents to enhance personal and professional development.

These are a few personality types, each offering unique and interesting data insights and characteristics into an individual’s projective tests. Selecting the most appropriate type of survey depends on the specific objectives and context in which the assessment will be used.

LEARN ABOUT: Structured Question

Top 25 Questions to Ask in Your Personality Survey

The key to getting accurate responses and a good survey response rate is the survey design . The survey platform consists of an online survey with multiple question types. The personality test survey can be broken down into 2 major sections, the demographic survey and the core personality type question survey.

Personality Survey Questions for Demographic Assessment

The demographic survey questions one of the most important aspects of the personality survey in a questionnaire since they help profile the respondents and in turn help understand how different sets of people have different types of personalities.

Some of the most important demographic questions are:

- Please select your gender for the survey

- What is your highest education completed?

- What is your marital status?

- What is your ethnicity?

- Please select your employment type

Survey Questions for Personality Test

These survey questions are a deep-dive into the personality tests of an individual. The questions in this section are set-up to understand how a certain individual behaves, the decisions describe the making process and temperament of most people.

- Do you like meeting new people?

- Do you like helping people out?

- What do you do if you have been unjustly blamed for something you didn’t do?

- How long does it take you to calm down when you’ve been angry?

- Are you easily disappointed?

- Do you help people only if you think you’d get something in return?

- Do you set up long term goals?

- Are you easily fazed?

- How often do you prefer to go out into a social environment or a public place?

- Are you considerate of other people’s feelings?

- Are you always busy?

- Do you like solving complex problems?

- Do you make people feel welcome?

- Is your go-to reaction in a problem to cheat your way out of it?

- Do you feel overwhelmed often?

- How often do you travel?

- Do you prefer familiarity over unfamiliarity?

- Are you generally passionate about social causes?

- Do you like being pushy?

- Do you tend to always see the good in people, no matter what the circumstance is?

Survey questions for a personality test serve as the foundation for gathering insights into an individual’s unique traits and behaviors. By carefully designing these questions, administrators can unlock valuable information about personality tests or dimensions.

LEARN ABOUT: Social Communication Questionnaire

5 Steps to Design a Good Personality Survey

A personality survey is effective only when set-up right. It is important to have the survey collect the insights that you need to gauge the respondent in the manner that’s most effective to you. Hence, the survey design is extremely important for the projective test.

The 5 steps to designing a good personality survey with abstract ideas, are:

- Define the survey objective: It is imperative to define the survey objective before creating the survey or deploying it to potential respondents. The “why” and “how” is important to be put in the proper place before beginning the study. This ensures that actionable insights can be derived from the data collection .

- Ask the right questions: To get a good survey response rate and to collect deep level personality insights, it is important that the right questions are asked in the survey. This helps the researcher collect personality test data information about a person or a set of people. This is mainly important when a new employee is being on boarded or is being considered for a promotion or role hike .

- Build the survey flow: Most respondents drop out of a survey as the questions if the survey questions are not relevant to them. This makes it very important to effectively use survey skip logic and branching so the preceding answer defines the next question displayed to a survey taker .

- Take the survey for a spin: Before the survey is deployed or administered to potential respondents, it needs to be thoroughly tested. This is to ensure that the survey renders properly and the logic of the survey is correctly developed.

- Analyze and report the survey responses : The data collection is only half of the survey objective. Analyzing and reporting those responses is the other important part of the data collection. Analysis helps draw trend lines and parallels between personalities and how different people react under certain circumstances.

However, it’s essential to recognize that personality is complex and multifaceted, and no survey can capture the entirety of an individual’s personality. Therefore, while personality surveys can be helpful tools, they should be used with other methods and approaches to understand human behavior and traits comprehensively.

Tips for a Good Personality Survey

Creating a good personality survey requires careful planning and consideration. By following these essential tips, you can design a survey that provides valuable insights into individuals’ traits and behaviors.

Let’s explore the key tips for conducting a successful personality survey. Listed below are some tips for a good personality survey:

Ask unbiased questions:

When you design a survey, make sure that the survey questions are unbiased. Driving respondents towards responding in a certain manner skews the survey results.

Personality Tests:

Consider incorporating established personality tests into your survey. Personality tests provide a standardized and structured approach to assessing individual traits, behaviors, and preferences. Additionally, the results from projective techniques tests can offer valuable data for analyzing trends, patterns, and correlations among different personality types within your survey population.

Be respectful with your questions:

In a personality survey, it is very important to be respectful with questions. If respondents feel personally attacked with survey questions, it increases the survey dropout rate .

Keep consistent answer options:

If the answer options of a survey in the survey software aren’t uniform, it may confuse the respondents and the survey results could subsequently get skewed. Hence, it is important to have consistent answer questions options in the survey.

Keep questions optional:

Due to the nature of the personality survey, complex or personal questions could form the basis of the survey. It is therefore important to allow the respondents the flexibility to skip questions or they would feel uncomfortable continuing and subsequently drop out of the survey.

A well-designed personality survey can unlock valuable insights into human behavior, personality type, vivid imagination, preferences, and traits. By following the tips, you can create a survey that delivers reliable results and facilitates a deeper understanding of personality.

LEARN ABOUT: Candidate Experience Survey

Personality surveys are an invaluable tool for gaining insights into human behavior and understanding the complexities of personality. With the help of advanced survey software platforms like QuestionPro, survey administrators can design and implement effective personality surveys that deliver meaningful and reliable results.

QuestionPro offers a range of features and tools that enable survey administrators to create engaging and personalized surveys, such as interactive question types, custom branding, and conditional logic.

By leveraging the power of QuestionPro’s survey software, organizations can design personality surveys that facilitate effective team-building, talent selection, and career development initiatives. Similarly, individuals can use personality surveys to gain self-awareness, identify strengths and weaknesses, and explore areas for personal growth.

LEARN MORE SIGN UP FREE

MORE LIKE THIS

Customer Communication Tool: Types, Methods, Uses, & Tools

Apr 23, 2024

Top 12 Sentiment Analysis Tools for Understanding Emotions

QuestionPro BI: From Research Data to Actionable Dashboards

Apr 22, 2024

21 Best Customer Experience Management Software in 2024

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Big Five Personality Traits

The Big Five model of personality, also known as the Five Factor Model (FFM), is a framework that outlines five core dimensions of personality. Based on decades of personality research and validity tests across the world, the Five Factor Model is the most commonly accepted theory of personality today. The five dimensions represent broad categories designed to capture much of the individual variation in personality and were determined by analyzing and grouping common adjectives used to describe peopleÕs personality and behavior. The Five Factor Model is also commonly referred to using the acronyms OCEAN and CANOE.

View All Term Definitions

Breakdown by Domain

Key features, context & culture.

- Originally developed through a lexical analysis of English terms, research has also been conducted in Chinese, Czech, Dutch, German, Greek, Hebrew, Hungarian, Italian, Polish, Russian, Spanish, Tagalog, Turkish, and more

- Research suggests the Big Five traits capture much of the variability in personality across cultures; however, languages other than English often produce additional important traits and there is some evidence to suggest that ÒopennessÓ in particular may be understood differently across cultures (e.g., intellect vs. rebelliousness)

Developmental Perspective

- Research on the validity of the Big Five traits has been conducted with all ages, but primarily with adults

- Research has shown that while relatively stable, traits develop and change with age

- No learning progression provided

Associated Outcomes

- Evidence suggests personality traits are correlated with life outcomes such as educational attainment, health, and labor market outcomes

Available Resources

Support materials.

- No materials provided

Programs & Strategies

- No programs or strategies provided

Measurement Tools

Personality traits are often measured through questionnaire scales such as:

- NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R)

- Big Five Inventory (BFI)

- Trait-Descriptive Adjectives (TDA)

Key Publications

- John, O.P., Naumann, L.P., & Soto, C.J. (2008), Paradigm Shift to the Integrative Big Five Trait Taxonomy in Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, 114-156.

- McCrae, R. R. and John, O. P. (1992), An Introduction to the Five?Factor Model and Its Applications. Journal of Personality, 60: 175-215.

Multiple researchers

Developer Type

To create a model of personality that encompasses as much variation in personality as possible using a manageable number of dimensions

Common Uses

The Five Factor Model serves as a unifying taxonomy in the field of personality research; it is widely used in many countries throughout the world

Key Parameters

Level of detail, compare domains, compare frameworks, compare terms, explore other frameworks.

- Visual Tools

- Our Methods

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Psychology Questions About Personality

Personality Psychology Research Topics

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

List of Personality Topics

- Before You Begin

- Starting Your Research

Personality is a popular subject in psychology, so it's no surprise that this broad area is rife with fascinating research topics. There are many psychology questions about personality that can be a great topic for a paper, or just help you get to know others a little better.

Are you looking for a great topic for a paper , presentation, or experiment for your personality psychology class? Here are just a few ideas that might help kick-start your imagination.

At a Glance

If you are writing a paper, doing an experiment, or just curious about why people do the things they do, exploring some different psychology questions about personality can be a great place to start. Topics you might choose to explore include different personality traits, personality tests, and how different aspects of personality influence behavior.

Possible Topics for Personality Psychology Research

The type of psychology questions about personality that you might want to explore depend on what you are interested in and what you want to know. Some topics you might opt to explore include:

Personality Traits

- How do personality traits relate to creativity? Are people with certain traits more or less creative? For your project, you might try administering scales measuring temperament and creativity to a group of participants.

- Are certain personality traits linked to prosocial behaviors ? Consider how traits such as kindness, generosity, and empathy might be associated with altruism and heroism .

- How does Type A behavior influence success in school? Are people who exhibit Type A characteristics more likely to succeed?

- Is there a connection between a person's personality type and the kind of art they like? For example, are extroverts more drawn to brighter colors or art that depicts people vs. abstract, non-representational art?

- Do people tend to choose pets based on their personality types? How do the personalities of dog owners compare to those of cat owners?

Personality Tests

- How do personality assessments compare? Consider comparing common assessments such as the Myers-Briggs Temperament Indicator , the Keirsey Temperament Sorter, and the 16PF Questionnaire.

- How reliable are personality test results? If you give someone the same test weeks later, will their results be the same?

Family and Relationships

- Do people tend to marry individuals with similar personalities? Do people who marry partners with personalities similar to their own have more satisfying relationships?

- What impact does birth order have on personality? Are first-born children more responsible, and are last-borns less responsible?

Personality and Behaviors

- Is there a connection between personality types and musical tastes ? Do people who share certain personality traits prefer the same types of music?

- Are people who participate in athletics more likely to have certain personality characteristics? Compare the personality types of athletes versus non-athletes.

- Are individuals with high self-esteem more competitive than those with low self-esteem? Do those with high self-esteem perform better than those who have lower self-esteem?

- Is there a correlation between personality type and the tendency to cheat on exams? Are people low in conscientiousness more likely to cheat? Are extroverts or introverts more liable to cheat?

- How do personality factors influence a person's use of social media? For example, are people high in certain traits more likely to use Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter? Are individuals who use social media frequently more or less extroverted?

You can also come up with questions about your own about different topics in personality psychology. Some that you might explore include:

- Big 5 personality traits

- The id, ego, and superego

- Psychosocial development

- Hierarchy of needs

- Myers-Briggs Type Indicator

- Personality disorders

What to Do Before You Begin Your Research

Once you find a suitable research topic, you might be tempted just to dive right in and get started. However, there are a few important steps you need to take first.

Most importantly, be sure to run your topic idea past your instructor. This is particularly important if you are planning to conduct an actual experiment with human participants.

In most cases, you will need to gain your instructor's permission and possibly submit your plan to your school's human subjects committee to gain approval.

How to Get Started With Your Research

Whether you are doing an experiment, writing a paper , or developing a presentation, background research should always be your next step.

Consider what research already exists on the topic. Look into what other researchers have discovered. By spending some time reviewing the existing literature, you will be better able to develop your topic further.

What This Means For You

Asking psychology questions about personality can help you figure out what you want to research or write about. It can also be a way to think about your own personality or the characteristics of other people. If you're stumped for an idea, consider talking to your instructor or think about some questions you've had about people in your own life.

Atherton OE, Chung JM, Harris K, et al. Why has personality psychology played an outsized role in the credibility revolution ? Personal Sci . 2021;2:e6001. doi:10.5964/ps.6001

American Psychological Association. Frequently asked questions about institutional review boards .

Leite DFB, Padilha MAS, Cecatti JG. Approaching literature review for academic purposes: The Literature Review Checklist . Clinics (Sao Paulo) . 2019;74:e1403. doi:10.6061/clinics/2019/e1403

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 25 July 2022

A prediction-focused approach to personality modeling

- Gal Lavi 1 ,

- Jonathan Rosenblatt 2 &

- Michael Gilead 3

Scientific Reports volume 12 , Article number: 12650 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

3043 Accesses

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

- Social neuroscience

In the current study, we set out to examine the viability of a novel approach to modeling human personality. Research in psychology suggests that people’s personalities can be effectively described using five broad dimensions (the Five-Factor Model; FFM); however, the FFM potentially leaves room for improved predictive accuracy. We propose a novel approach to modeling human personality that is based on the maximization of the model’s predictive accuracy. Unlike the FFM, which performs unsupervised dimensionality reduction, we utilized a supervised machine learning technique for dimensionality reduction of questionnaire data, using numerous psychologically meaningful outcomes as data labels (e.g., intelligence, well-being, sociability). The results showed that our five-dimensional personality summary, which we term the “Predictive Five” (PF), provides predictive performance that is better than the FFM on two independent validation datasets, and on a new set of outcome variables selected by an independent group of psychologists. The approach described herein has the promise of eventually providing an interpretable, low-dimensional personality representation, which is also highly predictive of behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Worldwide divergence of values

Self-supervised learning for human activity recognition using 700,000 person-days of wearable data

The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence

Introduction.

Humans significantly differ from each other. Some people’s idea of fun is partying all night long, and others enjoy binging on a TV series while eating snacks; some are extremely intelligent, and others less so; some are hot-headed, and others remain cool, no matter what. Because of this variety, predicting humans’ thoughts, feelings, and behaviors is a cumbersome task; nonetheless, we attempt to solve this task on a daily basis. For example, when we decide who to marry, we try to predict whether we can depend on the other person till death do us part; when we choose a career, we must do our best to predict whether we will be successful and fulfilled in a given profession.

In order to predict a person’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, people often have no other option but to generate something akin to a scientific theory 1 —a parsimonious model that attempts to capture the unique characteristics of individuals, and that could be used to predict their behavior in novel circumstances. Indeed, research shows that people employ such theories when predicting their own 2 and others’ behaviors. Unfortunately, theories based strictly on intuition are often highly inaccurate 3 , even if produced by professional psychological theoreticians 4 . In light of this, ever since the early days of psychology research, scholars have been attempting to devise personality models using the scientific method, giving rise to the longstanding field of personality science.

Personality, when used as a scientific term, refers to the mental features of individuals that characterize them across different situations, and thus can be used to predict their behavior. In the early years of personality research, scientists generated numerous competing theories and measures, but struggled to arrive at a scientific consensus regarding the core structure of human personality. In recent decades, a consensus theory of the core dimensions of human personality has emerged—the Five Factor Model (FFM).

The FMM emerged from the so-called “lexical paradigm”, which assumed that if people regularly exhibit a form of behavior that is meaningful to human life, then language will produce a term to describe it 5 . Given this assumption, personality psychologists performed research wherein they asked individuals to rate themselves on lists of common English language trait words (e.g., friendly, upbeat), and then developed and used early dimensionality-reduction methods to find a parsimonious model that can account for much of the variability in each person’s trait ratings 5 .

Much research shows that these five factors, often termed the “Big Five” are relatively stable over time and have convergent and discriminant validity across methods and observers 6 . Moreover, research into the FFM has replicated the dimensional structure in different samples, languages, and cultures 7 , 8 (but see 9 for a recent criticism). In light of this, the FFM is taken by some to reflect a comprehensive ontology of the psychological makeup of human beings 10 according to Mccrae and Costa 11 the five factors are “both necessary and reasonably sufficient for describing at a global level the major features of personality’’.

Surely, human beings are complex entities, and their personality is not fully captured by five dimensions; however, the importance of having a parsimonious model of humans’ psychological diversity cannot be overstated. As noted by John and Srivasta 12 , a parsimonious taxonomy permits researchers to study “ specified domains of personality characteristics, rather than examining separately the thousands of particular attributes that make human beings individual and unique.” Moreover, as they note, such a taxonomy greatly facilitate s “ the accumulation and communication of empirical findings by offering a standard vocabulary, or nomenclature”.

An additional consequence of having a parsimonious model of the core dimensions of human personality, is that such an abstraction enables the acquisition of novel knowledge via statistical learning (see 13 for a discussion of the importance of abstract representations in learning); namely, whereas the estimation of covariances between high-dimensional vectors is often highly unreliable (i.e., the so-called “curse of dimensionality” 14 ), learning the statistical correlates of a low-dimensional structure is a more tractable problem. For example, research has shown that participants’ self-reported ratings on the FFM dimensions can be reliably estimated based on their digital footprint 15 .

This ability to infer individuals’ personality traits using machine learning also raises serious concerns, as it may be used for effective psychological manipulation of the public. In 2013, a private company named Cambridge Analytica harvested the data of Facebook users, and used statistical methods to infer the personality characteristics of hundreds of millions of Americans 16 . This psychological profile of the American population was supposedly used by the Trump campaign in an attempt to tailor political advertisements based on an individuals’ specific personality profile. While the success of these methods remains unclear, given the vast amount of data accumulated by companies such as Alphabet and Meta, the potential dangers of machine-learning based psychological profiling is taken by many to be a serious threat to democracy 17 .

Even if dubious entities indeed manage to acquire the Big Five personality profile of entire populations, it is far from obvious that such information could be used to generate actionable predictions. Indeed, the FFM was criticized by some researchers for its somewhat limited contribution to predicting outcomes on meaningful dimensions 18 , 19 , 20 . In light of such claims, some have argued that the public concern over the Cambridge Analytica scandal was overblown 21 (but see 22 for evidence for potential reasons for concern).

Roberts et al. 23 present counter-argument for critical stances against the predictive accuracy of the FFM and note that: “As research on the relative magnitude of effects has documented, personality psychologists should not apologize for correlations between 0.10 and 0.30, given that the effect sizes found in personality psychology are no different than those found in other fields of inquiry.” While this claim is clearly true, there is also no doubt that such correlations (that translate to explained variance in the range of 1%-9%) potentially leave room for improvements in terms of predictive accuracy.

If one’s goal is to find a parsimonious representation of personality that has better predictive accuracy than the FFM, it could be instructive to remember that the statistical method by which the FFM was produced—namely, Factor Analysis—is not geared towards prediction. Factor analysis is an unsupervised dimensionality-reduction method (i.e., a method that maps original data to a new lower dimensional space without utilizing information regarding outcomes) aimed at maximizing explanatory coherence and semantic interpretability, rather than maximizing predictive ability. It does so by finding a parsimonious, low-dimension representation (e.g., the five Big Five factors: extraversion, neuroticism and so on) that maximizes the variance explained in the higher-dimension domain (e.g., hundreds of responses to questionnaire items; for example, “I am lazy”; “I enjoy meeting new people”). Advances in statistics and machine learning have opened up new techniques for supervised dimensionality-reduction. Namely, methods that reduce the dimensionality of a source domain (i.e., predictor variables, \({X}_{1},...{,X}_{n}\) ; in the case of personality, hundreds of questionnaire items) by focusing on the objective of maximizing the capacity of the lower-dimensional representation to predict outcomes of a target domain (outcome variables, \({Y}_{1},...{,Y}_{m}\) , for example, depression, risky behavior, workplace performance).

Such techniques where dimensionality-reduction is achieved via maximization of predictive accuracy across a host of target-domain outcomes hold the potential of providing psychologists with parsimonious models of a psychological feature space that serve as relatively “generalizable predictors” of important aspects of human behavior. Moreover, it may demonstrate that privacy leaks, a-lá Cambridge-Analytica, are indeed a serious threat to democracy, despite being dismissed by some as science fiction.

In light of this, we investigated whether a supervised dimensionality-reduction approach that takes into account a host of meaningful can potentially improve the predictive performance of personality models. Such an approach could pave the way to a new family of personality models and could advance the study of personality. Alternatively, it may very well be the case that the FFM indeed “carves nature at its joints” and provides the most accurate ontology of the psychological proclivities of humans. In such a case, the FFM may remain the best predictive model of personality, and our approach will not provide improvements in predictions.

In order to examine this question, we conducted three studies. In Study 1, we built a supervised learning model using big data of personality questionnaire items and diverse, important life outcomes. We reduced the dimensionality of 100 questionnaire items into a set of five dimensions, with the objective of simultaneously minimizing prediction errors across ten meaningful life outcomes. We hypothesized that the resulting five-dimensional representation will outperform the FFM representation–when fitting a new model and attempting to predict the ten important outcomes on a held-out dataset. Next, in Studies 2 and 3, we explored the performance of the resulting model on new outcome variables.

Participants

The analyses relied on the myPersonality dataset that was collected between 2007 and 2012 via the myPersonality Facebook application. The myPersonality database is no longer shared by its creators for additional use. We received approval to download that data from the administrators of myPersonality on January 7th, 2018, and downloaded the data shortly thereafter. After the myPersonality database was taken down in 2018, we sent an email to the administrators (on June 8th, 2018), and received confirmation that we can use the data we have already downloaded. The application enabled its users to take various validated psychological and psychometric tests, such as different versions of the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP) questionnaire. Many participants also provided informed consent for researchers to access their Facebook usage details (e.g., liked pages). Participation was voluntary and likely motivated by people’s desire for self-knowledge 24 . The Participants in the myPersonality database are relatively representative of the overall population 25 . All participants provided informed consent for the data they provided to be used in subsequent psychological studies. We used data from 397,851 participants (210,279 females, 142,497 males, and 44,805 did not identify) who answered all of the questions on the 100-item IPIP representation of Goldberg’s 26 markers for the FFM which are freely available for all types of use. Participants’ mean age was 25.7 years ( SD = 8.84). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ben-Gurion University, and was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Dependent variables

We sought to use supervised learning in order to find a low-dimensional representation of personality that can be used to predict psychological consequences across a diverse set of domains. We thus focused on ten meaningful outcome variables that were available in the myPersonality database, that cover many dimensions of human life which psychologists care about:

(1) Intelligence Quotient (IQ), measured with a brief 20 items version of the Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices test 27 .

(2) Well-being, measured with the Satisfaction with Life scale 28 .

Personal values, measured using two scores representing the two axes from the Schwartz's Values Survey:

(3) Self-transcendence vs. Self-enhancement values and

(4) Openness to Change vs. Conservation values 29 .

(5) Empathy, measured with the Empathy Quotient Scale 30 .

(6) Depression, measured with The Center for Epidemiologic Study Depression (CES-D) scale 31 .

(7) Risky behavior, measured with a single-item question concerning illegal drug use.

(8) Self-reports of legal, yet unhealthy behavior (measured as averaging two single-item questions concerning alcohol consumption and smoking).

(9) Single item self-report of political ideology.

(10) The number of friends of participants’ had on the social network Facebook.

Independent variables

Our independent variables were the participants’ answers to the 100 questions included in the IPIP-100 questionnaire 32 . In this questionnaire, the participants are asked to rate their agreement with various statements related to different behaviors in their life and their general characteristics and competencies, on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The original use of this questionnaire is to reliably gauge participants' scores on each of the FFM dimensions. It includes five subscales, each containing 20 items; the factor score for each FFM dimension can be calculated as a simple average of these 20 questions (after reverse coding some items). In the current research we treat each item from this list of 100 questions as a separate independent variable, and seek to reduce the dimensionality of this vector using supervised learning.

Model construction

The problem we set out to solve is to find a good predictive model that is: (a) based on the 100 questions of the existing IPIP-100 questionnaire, and (b) uses five variables only, so we can fairly compare it with the FFM. Reduced Rank Regression (RRR) is a tool that allows just that: it can be used to compress the original 100 IPIP items, to a set of five new variables. These new variables are constructed so that they are good predictors, on average, of a large set of outcomes. Unlike Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or Factor Analysis, RRR reduces data dimensionality by optimizing predictive accuracy.

We randomly divided our data into an independent train and test sets. Each subject in the train and test set had 100 scores of the IPIP questionnaire ( \({X}_{1},{X}_{2},...{,X}_{100}\) ), as well as their score in each of the ten dependent variables ( \({Y}_{1},{Y}_{2},...{,Y}_{10}\) ).

X ( n × 100) and Y ( n × 100) have been centered and scaled. We fitted a linear predictor, with coefficient vector:

And in matrix notation:

Our linear predictors were fully characterized by the matrix C. We wanted these predictors to satisfy the following criteria: (a) minimize the squared prediction loss (b) consist of 5 predictors, i.e., rank ( C ) = r = 5. Criterion (a) ensures the goodness of fit of the model, and criterion (b) ensures a fair comparison with the FFM. The RRR problem amounts to finding a set of predictors, \(\hat{C}\) , so that:

where || \(\cdot \) || denotes the Frobenius matrix norm. The matrix \(C\) can be expressed as a product of two rank-constrained matrices:

where \(B\) is of has p rows and r columns, denoted, p × r , and \({A}\) is of dimension q × r . The model (2) may thus be rewritten as:

The n × r matrix \(X\hat{B}\) , which we noted \(\tilde{X}\) , may be interpreted as our new low-dimension personality representation. Crucially for our purposes, the same set of r predictors is used for all dependent variables. By choosing dependent variables from different domains, we dare argue that this set of predictors can serve as a set of “generalizable predictors”, which we call henceforth the Predictive Five (PF). For the details of the estimation of \(\hat{B}\) see the attached code. For a good description of the RRR algorithm see 33 .

Model assessment

To assess the predictive performance of the PF, and compare it to the predictive properties of the classical FFM, we used a fourfold cross validation scheme. The validation worked as follows: we learned \(\hat{B}\) from a train set (397,851 participants) using RRR; we then divided the independent test set (800 participants) into 4 subsets; we learned \(\hat{A}\) from a three-quarters part of the test set (600 participants), and computed the R 2 on the holdout test set (200 participants); we iterated this process over the 4-test subsets. The rationale of this scheme is that: (a) predictive performance is assessed using R 2 on a completely novel dataset ; (b) when learning the predictive model, we wanted to treat the personality attributes as known. We thus learned \(\hat{B}\) and \(\hat{A}\) from different sets. The size of the holdout set was selected so that R 2 estimates will have low variance. The details of the process can be found in the accompanying code ( https://github.com/GalBenY/Predictive-Five ).

To examine the performance of the RRR algorithm against another candidate reference model we also performed Principal Component Regression (PCR), where we reduced the IPIP questionnaire to its 5 leading principal components, which were then used to predict the outcome variables. We used the resulting model as a point of comparison in follow-up assessment of predictive accuracy. Like the RRR case, we learned the principal components from the train-set (397,851 participants). Next we divided the independent test set (800 participants) into 4 subsets and used a fourfold cross validation: ¾ to learn 5 coefficients, and ¼ to compute.

In order to calculate the significance of the difference in the predictive accuracy of the models we took the following approach: predictions are essentially paired, since they originate from the same participant. For each participant, we thus computed the (holdout) difference between the (absolute) error of the PF and FFM models: \(|{{\widehat{y}}_{i}}^{PF}|-|{{\widehat{y}}_{i}}^{FFM}|\) . Given a sample of such differences, comparing the models collapses to a univariate t-test allowing us to reject the null hypothesis that the mean of the differences is 0.

PF loadings

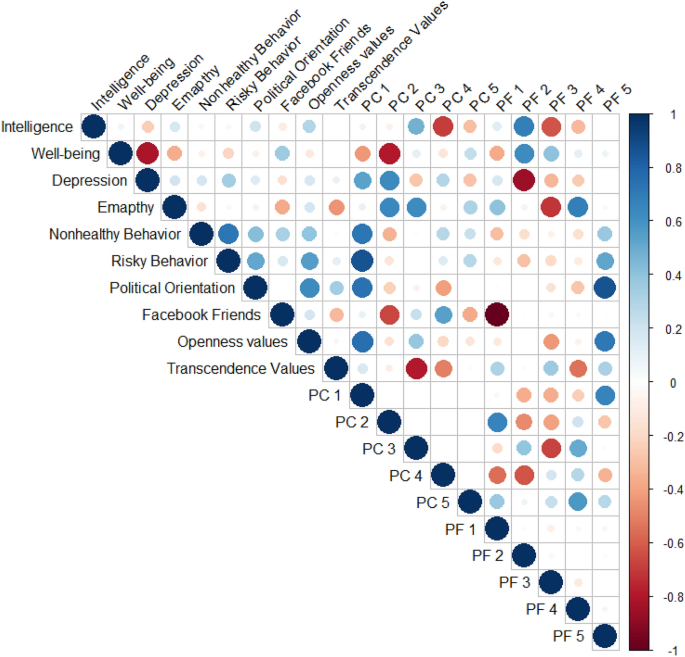

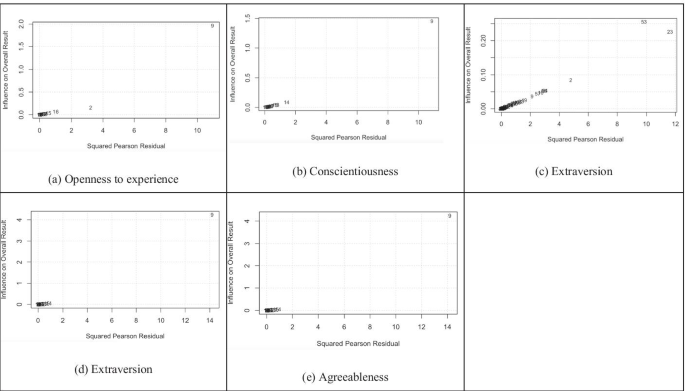

Each of the resulting PF dimensions were a weighted linear combination of IPIP-100 item responses. Despite the fact that the resulting model was based on a questionnaire meant to reliably gauge the FFM, the resulting outcome did not fully recapitulate the FFM structure. The detailed loadings for each of the resulting five dimensions appears in the supplementary materials (Fig. 1 , Supplementary Materials), can be examined in an online application we have created ( https://predictivefive.shinyapps.io/PredictiveFive ), and can be easily gleaned by examining the correlation of PF scores to the FFM scores (Fig. 2 ). None of the PF dimensions strongly correlated with demographic variables (Table 1 , Supplementary Materials). In Fig. 1 , we display the correlations between the ten outcome variables, five principle components of these outcome variables (capturing 86% of the total variance), and the five PF dimensions. For example, it can be observed the PF 3 is inversely related to performance on the intelligence test and to empathy.

Correlations between the 10 outcome variables, 5 principle components of outcome variables, and the 5 PF dimensions.

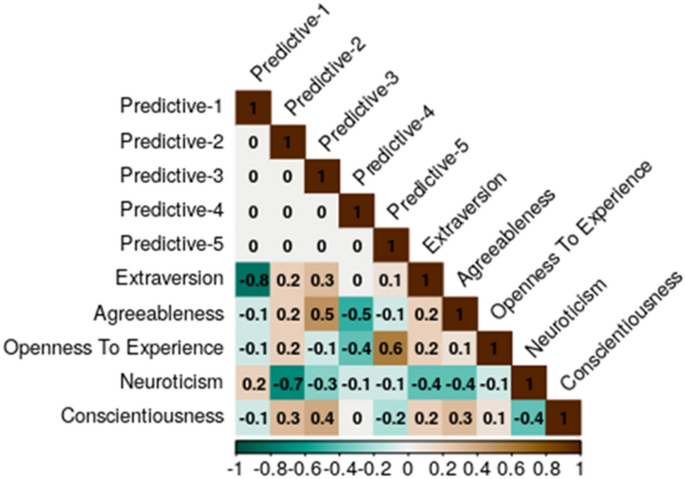

Correlations between the PF and FFM scale scores.

Predictive performance

The out-of-sample R 2 of the three models is reported in Table 1 . From this figure, we learn that the PF-based regression model is a better predictor of the outcome variables. This holds true on average (over behavioral outcomes), but also for nine of the ten outcomes individually. On 5 of the 10 comparisons, the PF-based model significantly outperformed the FFM, and in a single case the FFM-based model significantly outperformed the PF. The average improvement across all 10 measures was 40.8%.

Reproducibility analysis

If it were the case that our model discovery process produces very different loadings when run on different samples of participants, then the ontological status of the PF representation should be called into question.

In order to assess the reproducibility of the PF we split the training dataset from Study 1 into two datasets; sample A with 198,850 participants and sample B with 198,851 participants. We then learned the rotation matrix, B, on each data part, and applied it. Equipped with two independent copies of the PF, \({X}_{l }{\widehat{B}}_{l}, l=\{A,B\}\) replicability is measured by the correlation between data-parts, over participants. Table 2 reports this correlation, averaged over the 5 PFs (column “Correlation between replications”). As can be seen, the correlation between the replications is satisfactory-to-high and ranges from 0.7 to 0.98. This suggests that PF representation replicates well across samples.

Reliability analysis

If the same individuals, tested on different occasions, receive markedly different scores on the PF dimensions, then the ontological status of the PF representation should be called into question. To this end, we exploit the fact that 96,682 users answered the IPIP questionnaire twice. The test–retest correlation between these two answers is reported in Table 2 (column “Test–retest correlation”). It varied from 0.69 for the Dimension 3, to 0.79 for both Dimensions 1 and 5, suggesting that the variance captured by these dimensions is indeed (relatively) stable.

Divergence from the FFM

The superior predictive performance of the PF representation provides evidence that it differs from the FFM. Additionally, as can be gleaned from Fig. 2 (and from the detailed factor loadings’ Supplemental Material), Dimensions 3 and 4 reflect a relatively even combination of several FFM dimensions.

However, these observations do not provide us with an estimate of the degree of agreement between the two multidimensional spaces. Prevalent statistical methods of assessment of discriminant validity 34 are also not suitable to answer our question regarding the convergence\divergence between the PF and FFM spaces. These various methods only provide researchers with estimates of the agreement between unidimensional constructs .

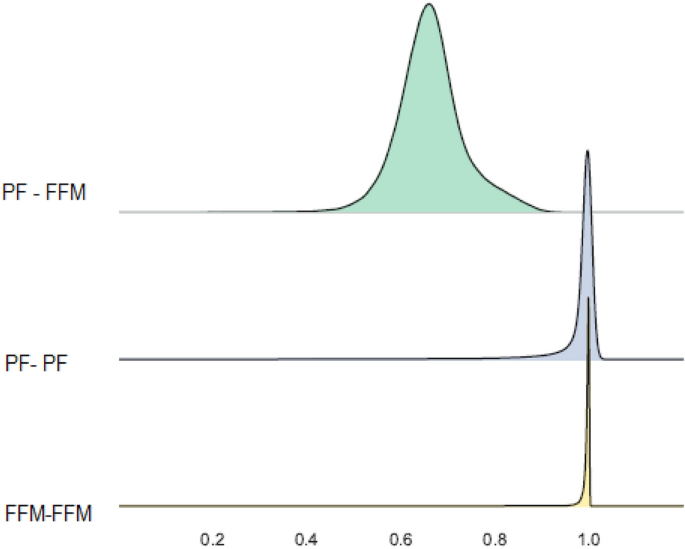

Nonetheless, the underlying logic behind these methods (i.e., a formalization of a multitrait-multimethod matrix 35 ) is still applicable to our case. We calculated an estimate of agreement between the FFM and the PF spaces using cosine similarity , which gauges the angle between two points in a multidimensional space (the smaller the angle, the closer are the points). Our rationale is that if the FFM scores differ from the PF, they should span different spaces. The cosine similarity within measures (in our case, first and second measurements, denoted T1 and T2) should thus be larger than the similarity between measures (FFM to PF).

We used the data from the 96,682 participants for which we had test–retest data. Instead of computing standard test–retest correlations, we calculated a multidimensional test-rest score as the cosine similarity of participants’ scores on the first and second measurement, for both the FFM and PF. These estimates are expected to be highly similar and provide an upper bound on the similarity measure, partially analogous to the diameter of the multitrait-multimethod matrix. In a second stage, for each T1 and T2 vector, we measured the extent to which participants’ FFM scores are similar to their PF score, thereby calculating a magnitude that is analogous to measures of divergent validity . Because cosine similarity is sensitive to the sign and order of dimensions, we extracted the maximal possible similarity between the two spaces, providing the most conservative estimate of divergent validity.

As can be seen in Fig. 3 , the T1-T2 similarity of the FFM is nearly maximal ( M = 0.994, SD = 0.011); the T1-T2 similarity of PF is also very high ( M = 0.969, SD = 0.100). The similarity between the FFM and the PF on both T1 and T2 is much lower ( M = 0.730, SD = 0.111). The minimal difference between the convergence measures and divergence measures is on the magnitude of Hedge's g of 2.217, clearly representing a substantial divergence between the FFM and PF spaces. In other words, while the PF representation bears some resemblance, it is clearly a different representation.

Distribution, over participants, of the multidimensional similarity between the FFM and PF representations.

The results of Study 1 provide evidence that a supervised dimensionality reduction method can yield a low-dimensional representation that is simultaneously predictive of a set of psychological outcome variables. We demonstrate that by using a standard personality questionnaire and supervised learning methods, it is possible to improve the overall prediction of a set of 10 important psychological outcomes, even when restricting ourselves to 5 dimensions of personality. RRR allowed us to compress the 100 questions of the personality questionnaire to a new quintet of attributes that optimize prediction across a large set of psychological outcomes. The resulting set of five dimensions differs from the FFM, and has better predictive power on the held-out sample than the classical FFM and an additional comparison benchmark of five dimensions generated using Principal Component Analysis.

A theory of personality should strive to predict humans’ thoughts, feelings, and behaviors across different life contexts. Indeed, the representation we discovered in Study 1 was superior to the FFM in terms of its ability to predict a diverse set of psychological outcomes on a set of novel observations. The fact that the same low-dimensional representation was applicable across a set of important outcomes of human psychology suggests that it is a relatively generalizable model, in the sense that it simultaneously applies to several important domains. However, despite the diversity of the outcome measures examined in Study 1, it remains possible that the PF representation is only effective for the prediction of the set of outcome measures on which it was trained. Such a finding would not negate the usefulness of this model, given the wide variety of outcomes captured by the PF. However, it is interesting to see whether the resulting representation can improve prediction on additional sets of outcomes. In light of this, in Study 2 we sought to examine the performance of the PF on a set of novel outcome measures that were present in the myPersonality database, but that were held-out from the model generation process. Specifically, in this study we sought to see whether the PF representation outperforms the FFM in its ability to predict participants’ experiences during their childhood .

Unlike the outcome measures used in Study 1, this dependent variable does not pertain to participants’ lives in the present, rather, it is a measure of their past experiences. As such, “retrodiction” of remote history may be especially challenging. Nonetheless, it is widely held that individuals’ psychological properties are shaped, at least to some extent, by the degree to which they were raised in a loving household 36 , 37 . Indeed, there is evidence to the fact that many specific psychological attributes are shaped by experiences with primary caregivers (e.g., shared environmental effects on topics such as food preference 38 , substance abuse 39 , and agression 40 ). In light of this, we reasoned that it is reasonable to expect that one's personality profile should contain information that is predictive of individuals' retrospective reports of their upbringing.

We used data from 3869 participants who answered all of the questions on the 100-item IPIP representation of 26 markers for the Big Five factor structure, and answered the short form “My Memories of Upbringing” (EMBU) questionnaire 41 .

The short form of the EMBU includes a total of six subscales: three subscales that contain questions to measure the extent to which the participants' father was a warm , rejecting , and overprotecting parent, and three subscales that measure the extent to which the participants' mother was warm , rejecting , and overprotecting .

As can be seen in Table 1 , for all six variables, prediction accuracy was relatively low; however, importantly, in all six cases the PF-based model outperformed the FFM-based model, and was significantly better for four out of the six outcome variables. The average improvement across the six outcome measures was 49.2%.

The results of Study 2 further support the idea that the PF representation that was built using the 10 meaningful outcome measures present in the myPersonality database is at least somewhat generalizable. However, Study 2 again relied on myPersonality participants, upon which the PF was built. In light of this, in Study 3 we sought to further test the generality of the PF by examining whether it outperforms the FFM-based model on a set of new participants. Furthermore, we wanted to see whether our model can outperform the FFM-based model on a set of new outcome measures selected by an independent group of professional psychologists, blind to our model-generation procedure.

We collected new data using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk ( www.MTurk.com ). M-Turk is an online marketplace that enables data collection from a diverse workforce who are paid upon successful completion of each task. Our target sample size was 500 participants, which is double the size of what is considered a standard, adequate sample size in individual differences research 42 . In practice, 582 participants participated in the study, 35 of them were omitted for failing attention checks, leaving 547 participants in the final dataset (243 females and 304 men). This number exceed a sample size of 470 participants which provides 95% confidence that a small effect (⍴ = 0.1) will be estimated with narrow (w = 0.1) Corridor of Stability 42 .

In order to make sure that the PF generalize across different domains of psychological interest, it was important to generate the list of outcome variables in a way that is not biased by our knowledge of the original ten outcome variables on which the PF was designed (i.e., intelligence, well-being, and so on). Therefore, on January 3rd, 2019, we gathered a list of 12 new outcome measures by posting a call on the Facebook group PsychMAP ( https://www.facebook.com/groups/psychmap ) asking researchers: “to name psychological outcome measures that you find interesting, important, and that can be measured on M-Turk using a single questionnaire item on a Likert scale.” Once we arrived at the target number of questions we closed the discussion and stopped collecting additional variables. The 12 items were suggested by eight different psychologists, six of which had a PhD in psychology and five were principal investigators. By using this variable elicitation method, we had no control over the outcome measures, and could be certain that we have gathered a randomly-chosen sample of outcomes that are of interest to psychologists.

This arbitrariness of the outcome generation process (selecting the first 12 outcomes nominated by psychologists, without any consideration of consensus views regarding variable importance)—and the likely low psychometric reliability of single-item measures–can be seen as a limitation of this study. However, our reasoning was that such a situation best approximates the "messiness" of the unexpected, noisy, real-world scenarios wherein prediction may be of interest–and as such, provides a good test of predictive performance of the FFM and PF.

In the M-turk study, participants rated their agreement with 12 statements (1- Strongly Disagree to 7- Strongly Agree). The elicited items were:

(1) “I care deeply about being a good person at heart”.

(2) “I value following my heart/intuition over carefully reasoning about problems in my life”.

(3) “Other people's pain is very real to me”.

(4) “It is important to me to have power over other people”.

(5) “I have always been an honest person”.

(6) “When someone reveals that s/he is lonely I want to keep my distance from him/her”.

(7) “Before an important decision, I ask myself what my parents would think”.

(8) “I have math anxiety”.

(9) “I am typically very anxious”.

(10) “I enjoy playing with fire”.

(11) “I am a hardcore sports fan”.

(12) “Politically speaking, I consider myself to be very conservative”.

The independent variables were participants’ answers to the 100 questions of the IPIP questionnaire.

Similarly to Study 1, we use a fourfold cross validation scheme in order to assess the predictive performance of the PF on new data set and outcome variables. Next, we compared it to the predictive performance of the FFM. The validation worked as follows: we had \(\hat{B}\) from Study 1, we learned \(\hat{A}\) from a part of the new sample (400 ~ participants) and computed the R 2 on the holdout test set (130 ~ participants). In the spirit of the fourfold cross-validation, we iterated this process over the 4-test sets and calculated the average test R 2 for each model.

Similarly to Studies 1–2, the results showed that the predictive performance of the PF was again better than that of the Big Five, although the improvements were more modest (average 30% improvement across the 12 measures). In 5 out of 12 cases, the PF-based model was significantly better than the FFM-based model, and the opposite was true in 2 cases.

The out-of-sample R 2 of the two models (PF\Big Five) in Study 3 show a consistent trend with the results presented earlier in Study 1 and Study 2, that is, a somewhat higher percentage of explained variance in the models with the PF as predictors. This improvement observed in Study 3 was more modest than that observed earlier, but is nonetheless non-trivial—given that the set of outcome variables was different from the one the PF representation was trained on, and given that the PF representation was trained on items from questionnaires designed to measure the FFM. As such, the results of Studies 1–3 clearly demonstrate the generalizability of the PF.

A potential criticism of these findings is that the success of the PF model was more prominent on variables that were more similar to the 10 dependent measures upon which the PF was trained. However, it is important to keep in mind that the 12 outcome measures in this study were selected at random by an external group of psychologists. As such, this primarily means that the 10 psychological outcomes used to train the PF indeed provide good coverage of psychological processes that are of interest to psychologists, and thereby, overall, generalize well to novel prediction challenges.

General discussion

In this contribution, we set out to examine the viability of a novel approach to modeling human personality. Unlike the prevailing Five-Factor Model (FFM) of personality, which was developed by relying on unsupervised dimensionality reduction techniques (i.e., Factor Analysis), we utilized supervised machine learning techniques for dimensionality reduction, using numerous psychologically meaningful outcomes as data labels (e.g., intelligence, well-being, sociability). Whereas the FFM is optimized towards discovering an ontology that explains most of the variance on self-report measures of psychological traits, our new approach devised a low-dimensional representation of human trait statements that is optimized towards prediction of life outcomes. Indeed, the results showed that our model, which we term the Predictive Five (PF), provides predictive performance that is better than the one achieved by the FFM in independent validation datasets (Study 1–2), and on a new set of outcome variables, selected independently of the first study (Study 3). The main contribution of the current work is explicating and demonstrating a methodological approach of generating a personality representation. However, the results of this work is a specific representation that is of interest and of potential use in and of itself. We now turn to discuss both our general approach and the resulting representation.

Interpreting the PF

The dimensional structure that emerged when using our supervised-dimensionality reduction approach differed from the FFM. Two dimensions (Dimension 1 and 2) largely reproduced the original FFM factors of Extraversion and Neuroticism. Interestingly, these two dimensions are the ones that were highlighted in early psychological research as the “Big Two” factors of personality (Wiggins, 1966). Dimension 5 was also highly related to an existing FFM dimension, namely, Openness to Experience .

The third and fourth dimensions in the model did not correspond to a single FFM trait, but were composed of a mixture of various items. An inspection of the loadings suggests that Dimension 4 is related to some sort of a combative attitude, perhaps captured best by the construct of Dominance 43 , 44 , 45 . The items that loaded highly on this dimension related to hostility (“Do not sympathize with others”; “Insult people”), a right-wing political orientation (“Do not vote for liberal political candidates”), and an approach-oriented 46 stance (“Get chores done right away”; “Find it easy to get down to work”).

Like PF Dimension 4, Dimension 3 also seemed to capture approach-oriented characteristics (with high loadings for the items “Get chores done right away” and “Find it easy to get down to work”), however, this dimension differed from Dimension 4 in that it represented a harmony-seeking phenotype 47 . The items highly loaded on this dimension were those associated with low levels of narcissism (“keep in the background”, “do not believe I am better than others”) but with a stable self-worth (“am pleased with myself”). Additional items that were highly loaded on this dimension were those that reflect cooperativity (“concerned with others” and “sympathize with others”).

These two dimensions may seem like dialectical opposites. Indeed, the item “sympathize with others” strongly loaded on both factors, but with a different sign. However, the additional items that strongly loaded on these two dimensions appear to have provided a context that altered the meaning of this item. This is evident in the fact that Dimensions 3 and 4 are not correlated with each other. A possible speculative interpretation is that the two phenotypes captured by Dimensions 3 and 4 can be thought of as two strategies that may have been adaptive throughout human evolution. The first, captured by Dimension 4 seems to represent aggressive traits that may have been especially useful in the context of inter -group competition and conflict; the second, captured by Dimension 3, seems to represent traits that may be associated with intra -group cooperation and peace.

In general, the interpretability of the PF representation is lower than that of the FFM, with some surprising items loaded together on the same dimension. For example, the two agreeableness items that “do not believe I am better than others” and “respect others” that are strongly correlated with each other were highly loaded onto Dimension 1 (that is related to introversion), but with opposite signs. To a certain extent, this is a limitation of the predictive approach in psychology. However, such confusing associations may lead us towards identifying novel insights. For example, it is possible that some individuals adopt an irreverent stance towards both self and others, and such a stance could be predictive of various psychological outcomes, and correlated with introversion.

Towards a more predictive science of personality

As noted, the reasons that people seek models of personality are twofold: first, we want models that allow us to understand, discuss and study the differences between people; second, we need these models in order to be able to predict and affect people’s choices, feelings and behaviors 48 . Current approaches to personality modeling succeeded on the former, providing highly comprehensible dimensions of individual differences (e.g., we can easily understand and communicate the contents of the dimension of “Neuroticism” by using this sparse semantic label). However, the ability of the FFM to accurately predict outcomes in people’s lives is at least somewhat limited 19 , 20 , 20 , 49 .

The significance of the current work is that it describes a new approach to modeling human personality, that makes the prediction of behavior an explicit and fundamental goal. Our research shows that supervised dimensionality reduction methods can generate relatively generalizable, low-dimensional models of personality with somewhat improved predictive accuracy. Such an approach could complement the unsupervised dimensionality reduction models that have prevailed for decades in personality research. Moreover, this research can complement attempts to improve the predictive validity of psychology by using non-parsimonious (i.e., facets and item-level) questionnaire-based predictive models 50 .

Aside from providing a general approach for the generation of personality models, the current research also provides a potentially useful instrument for psychologists across different domains of psychological investigation. Our findings suggest that psychologists who are interested in predicting meaningful consequences (e.g., workplace or romantic compatibility) or in optimizing interventions on the basis of individuals’ characteristics (e.g., finding out which individuals will best respond to a given therapeutic technique)—may benefit from incorporating the PF dimensions in their predictive models. To facilitate such future research, we provide the R code that calculates the five dimensions based on answers on the freely available IPIP-100 questionnaire ( https://github.com/GalBenY/Predictive-Five ). The use of an existing, open-access, widely-used questionnaire means that researchers can now easily apply the PF coding scheme alongside with the FFM coding scheme to their data, and compare the utility of the two models in their own specific research domains.

One avenue of potential use of the PF representation is in clinical research. The PF showed improved prediction of depression and well-being; moreover, the PF substantially outperformed the FFM in the prediction of two known resilience factors (intelligence and empathy). Specifically, PF Dimension 3 (which, as noted above, seems to represent some harmony-seeking phenotype) significantly contributed to the prediction of all of four outcomes. As such, future work could further investigate the incremental validity of this dimension (and the PF representation more generally) as a global resilience indicator.

Across a set of 28 comparisons, the predictions derived from the PF-based model were significantly better in 15 cases, and significantly worse in 3 cases. The average improvement in R 2 across the 28 outcomes was 37.7%. However, it is important to note that the PF representation described herein is just a first proof of concept of this general approach, and it is likely that future attempts that are untethered to the constraints undertaken in the current study can provide models of greater predictive accuracy. Specifically, in the current research we relied on the IPIP-100, a questionnaire designed by researchers specifically in order to reliability measure the factors of the FFM, and limited ourselves to a five-dimension solution, to allow comparison with the FFMs. The PF representation outperformed the FFM representation despite these constraints. These results provide a very conservative test for the utility of our approach.

Future directions

Future attempts to generate generalizable predictive models will likely produce even stronger predictive performance if they relax the constraint of finding exactly five dimensions and perform dimensionality-reduction based on the raw data used to generate the FFM itself—namely, the long list of trait adjectives that exist in human language, and that were reduced into the five dimensions of the FFM.

For the sake of simplicity comparability to the FFM, the current work employed a linear method for supervised dimensionality reduction. Recent work in machine learning has demonstrated the power of Deep Neural Networks as tools for dimensionality reduction (e.g., language embedding models). In light of this, it is likely that future work that utilizes non-linear methods for supervised dimensionality reduction could generate ever more predictive representations (i.e., “personality embeddings”).

A limitation of the current work is that the PF was trained on a relatively limited set of 10 important life outcomes (e.g., IQ, well-being, etc.). While these outcome measures seem to cover many of the important consequences humans care about (as evident by the predictive performance on Study 3), it is likely that training a PF model on a larger set of outcome variables will improve the coverage and generalizability of future (supervised) personality models. A potential downside of extending the set of outcome measures used for training, is that at some point (e.g., 20, 100 outcomes) it is possible that the “blanket will become too short”: namely, that it will be difficult to find a low-dimensional representation that arrives at satisfactory prediction performance simultaneously across all outcomes. Thus, future research aiming at generating more predictive personality models may need to find a “sweet spot” that allows the model to fit to a sufficiently comprehensive array of target outcomes.

What may be the most important consequence of the current approach is that whereas previous attempts of modeling human personality necessarily limited by their reliance on the subjective products of the human mind (i.e., were predicated on human-made psychological theories, or subjective ratings of trait words), our approach holds the unique potential of generating personality representations that are based on objective inputs.

A final question concerning predictive models of personality is whether we even want to generate such models, given the potential of their misuse. While the current results still show the majority of variance in psychological outcomes remain unexplained–in the era of social networks and commercial genetic testing, the predictive approach to personality modeling could theoretically lead to models that render human behavior highly predictable. Such models give rise to both ethical concerns (e.g., unethical use by governments and private companies, as in the Cambridge-Analytica scandal) and moral qualms (e.g., if behavior becomes highly predictable, what will it mean for notions of free will and personal responsibility?). While these are all valid concerns, we believe that like all other scientific advancements, personality models are tools that can provide a meaningful contribution to human life (e.g., predicting suicide in order to avoid it; predicting which occupation will make a person happiest). As such, the important, inescapable quest towards generating even more effective models that will allow us to predict and intervene in human behavior is only just the beginning.

Data availability

The data for Study 1, 3 and 4 rely on the myPersonality database ( www.mypersonality.org ) which is an unprecedented big-data repository for psychological research, used in more than a hundred publications. We achieved permission from the owners of the data to use it for the current research—but we do not have their permission to share it for wider use. The data for Study 2 is available upon request. We also share the complete code and the full model with factor loadings ( https://github.com/GalBenY/Predictive-Five ).

Newcomb, T. & Heider, F. The psychology of interpersonal relations. Am. Sociol. Rev. 23 , 742 (1958).

Article Google Scholar

Dweck, C. S. Self-Theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality, and Development (Psychology press, London, 2013).

Book Google Scholar

Swann, W. B. Jr. Quest for accuracy in person perception: A matter of pragmatics. Psychol. Rev. 91 , 457–477 (1984).

Ægisdóttir, S. et al. The meta-analysis of clinical judgment project: Fifty-six years of accumulated research on clinical versus statistical prediction. Couns. Psychol. 34 , 341–382 (2006).

Allport, G. W. & Odbert, H. S. Trait-names: A psycho-lexical study. Psychol. Monogr. 47 , i (1936).

Costa, P. T. Jr. & McCrae, R. R. Personality: Another ‘hidden factor’ is stress research. Psychol. Inq. 1 , 22–24 (1990).

Allik, I. & Allik, I. U. The Five-Factor Model of Personality Across Cultures (Springer, Berlin, 2002).

Google Scholar

Benet-Martínez, V. & John, O. P. Los Cinco Grandes across cultures and ethnic groups: Multitrait-multimethod analyses of the Big Five in Spanish and English. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 75 , 729–750 (1998).

Laajaj, R. et al. Challenges to capture the big five personality traits in non-WEIRD populations. Sci. Adv. 5 , eaaw5226 (2019).

Article ADS Google Scholar

John, O. P. The ‘Big Five’ factor taxonomy: Dimensions of personality in the natural language and in questionnaires. Handbook of personality: Theory and research (1990).

McCrae, R. R. & Costa, P. T. Clinical assessment can benefit from recent advances in personality psychology. Am. Psychol. 41 , 1001–1003 (1986).

John, O. P. & Srivastava, S. The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. Handbook of personality: Theory and (1999).

Gilead, M., Trope, Y. & Liberman, N. Above and beyond the concrete: The diverse representational substrates of the predictive brain. Behav. Brain Sci. 43 , e121 (2019).

Chen, L. Curse of dimensionality. Encycl. Database Syst. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-8265-9_133 (2018).

Kosinski, M., Stillwell, D. & Graepel, T. Private traits and attributes are predictable from digital records of human behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110 , 5802–5805 (2013).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Confessore, N. Cambridge Analytica and Facebook: The Scandal and the Fallout So Far. The New York Times (2018).

Harari, Y. N. Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow (Random House, London, 2016).

Hough, L. M. The ‘Big Five’ personality variables-construct confusion: Description versus prediction. Hum. Perform. 5 , 139–155 (1992).

Sibley, C. G., Osborne, D. & Duckitt, J. Personality and political orientation: Meta-analysis and test of a threat-constraint model. J. Res. Pers. 46 , 664–677 (2012).

Morgeson, F. P. et al. Are we getting fooled again? Coming to terms with limitations in the use of personality tests for personnel selection. Pers. Psychol. 60 , 1029–1049 (2007).

Gibney, E. The scant science behind Cambridge Analytica’s controversial marketing techniques. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-03880-4 (2018).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Matz, S. C., Kosinski, M., Nave, G. & Stillwell, D. J. Psychological targeting as an effective approach to digital mass persuasion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114 , 12714–12719 (2017).

Article CAS Google Scholar