Correlates of teachers’ classroom management self-efficacy: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Meta-Analysis

- Open access

- Published: 12 April 2024

- Volume 36 , article number 43 , ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Siyu Duan 1 , 2 ,

- Kerry Bissaker ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8008-3744 2 &

- Zhan Xu 1

123 Accesses

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This meta-analysis examined literature from the last two decades to identify factors that correlate with teachers’ classroom management self-efficacy (CMSE) and to estimate the effect size of these relationships. Online and reference list searches from international and Chinese databases yielded 1085 unique results. However, with a focus on empirical research the final sample consisted of 87 studies and 22 correlates. The findings cluster the correlates of CMSE into three categories: teacher-level factors (working experience, constructivist beliefs, teacher stress, job satisfaction, teacher commitment, teacher personality, and teacher burnout), classroom-level factors (classroom climate, classroom management, students’ misbehaviour, students’ achievement, classroom interaction, and student-teacher relationship), and school-level factors (principal leadership and school culture). The results of this meta-analysis show small to large correlations between these 15 factors with CMSE. How these factors are associated with teachers’ CMSE and recommendations for future CMSE research are discussed.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Classroom management is frequently defined as “the actions teachers take to create an environment that supports and facilitates both academic and social-emotional learning (p.4)” (Evertson & Weinstein, 2006 ). There is a consensus that classroom management no longer simply refers to responses towards student misbehaviour, rather it is serves as “an umbrella term for an array of teaching strategies that enhance effective time use in class (p.2)” (Lazarides et al., 2020 ). Effective classroom management is highly related to students' academic, behavioural, and social-emotional outcomes (Korpershoek et al., 2016 ), as well as teachers' wellbeing (Sutton et al., 2009 ). To effectively manage classrooms, teacher must possess professional knowledge, skills, and efficacy beliefs in their classroom management capability (Main & Hammond, 2008 ). Classroom management self-efficacy (CMSE) is a teacher’s belief about his or her capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to create a positive learning environment that supports successful student learning outcomes (Lazarides et al., 2018 ).

Self-efficacy is a self-perception of one's capacity to accomplish a certain task (Bandura, 1977 ), which has been well represented in educational research. Teacher self-efficacy (TSE) refers to a teacher’s belief of his or her capabilities to perform a specific teaching task successfully in a particular teaching context (Tschannen-Moran et al., 1998 ), with a growing acknowledgment of its influence on important outcomes for teachers and students (Klassen & Tze, 2014 ). According to Bandura ( 1997 ), individual’s self-efficacy is reflected and evaluated through interpreting information from four sources, namely mastery experiences , vicarious experiences , social persuasions , and emotional arousal . Tschannen-Moran et al. ( 1998 ) proposed an integrated model of teacher self-efficacy applying these four sources of efficacy information. They suggested that the development of teacher self-efficacy is cyclical with teachers’ interpretations of efficacy-relevant information affecting teacher self-efficacy. This in turn has an impact on the setting of teaching objectives, teaching effort and persistence in managing challenging situations. The performance of completing a teaching task, either successfully or not, becomes a source of new efficacy information, which may have either positive or negative effects on TSE.

Of the four sources of influence on TSE, mastery experiences, which involve teachers achieving their desired goals, are often viewed as the strongest predictor of TSE (Usher & Pajares, 2008 ) TSE in the school context has been linked to students’ successful academic achievements and positive classroom climate (Klassen & Tze, 2014 ). Vicarious experiences including the observation of highly effective teachers or noting students’ preferred teachers provide another source of influence on teachers’ TSE. Individual’s TSE may be influenced either positively or negatively as they engage in reflecting on their own personal teaching competence or relationships with their students in comparison to those of colleagues. Social persuasions, often in the form of feedback from experts or students, is a particularly powerful influence for preservice and novice teachers (individuals with little prior experience) as they can either develop more confidence or doubt their capacities to be a successful teacher (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2007 ). Finally, emotional arousal is elicited by stress, anxiety and tension and can affect individual’s perceived self-efficacy when coping with tough demanding situations, for example, novice teachers receiving either positive or negative feedback from leaders or reactions from students and/or parents (Marschall, 2023 ; Morris et al., 2017 ). Together these four sources, being both intrinsic and extrinsic, generate either positive or negative self-efficacy in a specific teaching context.

The specificity of context is important to individual’s TSE. Although teachers might feel efficacious in one area of instruction or with one group of students, they may also report low confidence in different areas or student group (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001 ). Acknowledging the context-specific nature of TSE, some researchers began exploring TSE in specific areas, such as science teaching (Riggs & Enochs, 1990 ), language and literacy teaching (Cantrell & Callaway, 2008 ), mathematics teaching (Bardach et al., 2022 ), special/inclusive education (Coladarci & Breton, 1997 ; Woodcock et al., 2022 ), teaching with technology (Alt, 2018 ), and classroom management (Dicke et al., 2014 ; Emmer & Hickman, 1991 ; Hettinger et al., 2021 ; Lazarides et al., 2018 ; Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001 ). Tschannen-Moran et al. ( 1998 ) noted that determining an optimal specificity level of TSE is challenging. TSE measures are most useful and generalizable when measures refer to specific teaching activities and tasks, but their predictive power is limited to specific skills and contexts. Classroom management, a critical teaching skill domain rather than a particular context (e.g., teaching science), has therefore attracted the attention of TSE researchers (O'Neill & Stephenson, 2011 ). Aloe et al. ( 2014 ) examined the relationship between CMSE and teacher burnout, acknowledging that CMSE is a domain specifical construct.

CMSE has already been identified as a distinct dimension of TSE, both for pre-service teachers (Emmer & Hickman, 1991 ) and in-service teachers (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001 ). To measure self-efficacy for classroom management, some researchers (e.g., Brouwers & Tomic, 2000 ; Hettinger et al., 2023 ) used sub-scales of TSE scales, such as Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy Scale (TSES) (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001 ), and Teacher Efficacy Scale (TES) (Emmer & Hickman, 1991 ). Specific scales investigating CMSE, however, have also been developed. For example, the Behaviour Management Self-Efficacy Scale was designed to measure preservice teachers’ self-efficacy of classroom management (Main & Hammond, 2008 ). The items used to measure CMSE were mainly for maintaining order and control in classrooms and facilitating student socialisation and cooperation. Whereas the other aspects of classroom management, establishing and enforcing rules, gaining and maintaining engagement, and resources allocation, were less represented in CMSE measurements (O'Neill & Stephenson, 2011 ).

Research findings identified that teachers with high levels of CMSE show more interests in using student-centred strategies to approach problems (Emmer & Hickman, 1991 ), hold more humanistic classroom management beliefs (Woolfolk & Hoy, 1990 ), feel more empowered to help students in social-emotional (Reilly, 2002 ) and academic areas (Lazarides et al., 2018 ) as well as in the area of classroom behaviour (Dicke et al., 2014 ). However, high general TSE do not ensure high levels of CMSE. Understanding the factors of influence on teachers’ CMSE is important for eductaion practitioners, policy development, preservice teacher programs and researchers. Therefore, this article examines the factors that serve to shape CMSE and to provide an overview of the current research about CMSE and how CMSE could be improved.

To date, there have been multiple reviews of global TSE conducted in reviewing several distinct areas: the measurements of TSE (Tschannen-Moran et al., 1998 ); summarizing key issues surrounding the TSE research (Klassen et al., 2011 ); examining the effectiveness of interventions on TSE (McArthur & Munn, 2015 ); synthesizing the research exploring the relationship between TSE and teaching effectiveness (Klassen & Tze, 2014 ; Tschannen-Moran et al., 1998 ), and teacher burnout (Brown, 2012 ). However, limited attention has been paid specifically to reviewing research about CMSE with O'Neill and Stephenson ( 2011 ) conducting a comprehensive review of CMSE items and scales and Aloe et al. ( 2014 ) examining the evidence of CMSE in relation to teacher burnout. By reviewing factors that correlate with CMSE, our paper also makes contributions to TSE theory and clarifies the special features of TSE in specific area of classroom management.

Conceptualizing the review

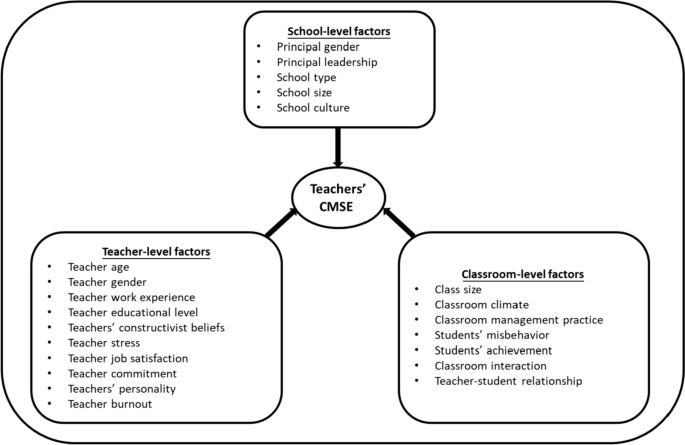

To frame our conceptual understanding of CMSE, we draw on the three categories of factors related to TSE as defined by Fackler et al. ( 2021 ) and explore in more depth some of these factors as they align to recent research. As presented in Fig. 1 , the proposed conceptual framework guided our synthesis of the literature, which indicated that factors associated with CMSE can be divided into three main strands: (1) personal characteristics of teacher (teacher-level factors); (2) characteristics of classroom composition (classroom-level factors); (3) teachers’ working conditions (school-level factors).

Conceptual Framework for Synthesizing Empirical Research on CMSE

First, the conceptual framework includes teacher personal characteristic, facilitating our understanding of how teacher background (e.g., gender, age, working experience, educational level) influences teachers’ beliefs towards the area of classroom management. Previous studies suggest that there is no age effect on teachers’ CMSE (Ford, 2019 ; Hicks, 2012 ; Lazarides et al., 2020 ; Lee & van Vlack, 2018 ). Unlike age, mixed results were found for the relationship between other demographic variables and CMSE. Some found a positive relationship for female teachers (Calkins et al., 2021 ; Zee et al., 2016 ), for male teachers (Hettinger et al., 2021 ; Tran, 2015 ), but also no gender effect (Lazarides et al., 2020 ). Some found teacher education level had a positive relationship with CMSE (Hu et al., 2021 ; Valente et al., 2020 ) but some found a negative relationship (Fackler et al., 2021 ). A higher level of CMSE was identified for more experienced teachers (Brouwers & Tomic, 2000 ; Klassen & Chiu, 2010 ), whereas no changes in CMSE were found from early until mid-career teachers (Lazarides et al., 2020 ).

In addition to demographic variables, many studies have examined the relationship between teachers’ CMSE and psychometric constructs. Self-efficacy has been viewed as a protective factor for teacher against psychological strain (Lazarides et al., 2020 ; Schwerdtfeger et al., 2008 ). Teachers who perceive they have sound ability to manage the classroom are less prone to increased stress levels. The findings of extant research are as expected indicating that CMSE is negatively related to psychological strain (teacher stress, teacher burnout) (Brouwers & Tomic, 2000 ; Eddy et al., 2019 ; Vidic et al., 2021 ; Williams, 2012 ) and positively related to teachers’ wellbeing (job satisfaction, teacher commitment) (Dicke et al., 2018 ; Klassen & Chiu, 2010 ; Liu et al., 2018 ; Miller, 2020 ; von der Embse et al., 2016 ).

Personality traits are general behavioural tendencies that may influence how efficacy information is evaluated and/or have an effect on people’s behaviour, and in turn, influence the evaluation of self-efficacy (Baranczuk, 2021 ). The Big Five, known as the most widely accepted taxonomy of personality traits, consists of neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness (McCrae & Costa, 2003 ). Several studies have also examined the relationship between CMSE and teacher’s personality assessed by the Big Five Inventory suggesting that openness and extraversion have positive relationships with CMSE (Bullock et al., 2015 ; Rahimi & Saberi, 2014 ). Teachers’ constructivist beliefs, which refers to “the ways they (teachers) believe students learn best and how they as teachers might facilitate this learning” (OECD, 2014 , p.165), have also shown a positive relationship with CMSE (Berger et al., 2018 ; Fackler et al., 2021 ).

Turning to the second category, researchers have examined several characteristics of classroom composition, ranging from class setting to teachers’ behaviour towards student, and students’ outcomes. It was suggested that a bigger class size was associated with a high level of teacher global self-efficacy (Raudenbush et al., 1992 ). However, for teacher self-efficacy in classroom management in particular, a negative association with large class size was found (Kunemund et al., 2020 ). Self-efficacy beliefs has been suggested to affect individuals’ behaviours at different level, from initial choice of behaviour type to the amount of effort and the extent of persistence in the implementation process (Bandura, 1977 ). CMSE theoretically acts as a mediator factor between teachers’ knowledge and practice towards the area of classroom management. Positive aspects of classroom management (Chen et al., 2020 ; Lazarides et al., 2020 ) were positively related to CMSE. On the other hand, the success that teachers achieve in the classroom (mastery experiences) such as good classroom climate (Guangbao & Timothy, 2021 ), students’ achievement (Hassan, 2019 ), high quality classroom interaction (Ryan et al., 2015 ), and positive student-teacher relationship (Zee et al., 2017 ) were suggested to inform teachers’ CMSE.

According to social cognitive theory, human behaviour is a product of the interaction between personal processes and the external environment (Bandura, 1986 ). School-level factors representing, to some extent, the environment and conditions in which teachers work, have increasingly gained the attention of researchers of CMSE. Similar to teachers, the relationship between general teacher self-efficacy and principal demographics (e.g., gender, age, working experience) has been examined. For TSE in classroom management in particular, mixed results were found for principal gender, with a positive association for male principals (Fackler et al., 2021 ), but also no effect based on principal gender (Ford, 2019 ). In regard to time-related characteristics like principal age and working experience, a negative association was found (Fackler et al., 2021 ). Another factor that has been reported by many studies (Bellibas & Liu, 2017 ; Buentello, 2019 ; Fackler et al., 2021 ; Ford, 2019 ; Holzberger & Prestele, 2021 ) to have a significant impact on teachers' perceptions of CMSE is principal leadership. For school organizational characteristics, some studies (McLeod, 2012 ; Öztürk et al., 2021 ) have examined the relationship between school culture and CMSE, some (Fackler et al., 2021 ; George et al., 2018 ) have examined CMSE between teachers in private school and public school, while some (Fackler et al., 2021 ; Looney, 2004 ) have examined CMSE for teachers located in different school size (number of student enrolments).

Overall, the conceptual framework depicted in Fig. 1 captures correlates of CMSE that are both theoretically and empirically tested. In light of the ongoing inconsistency of findings in these studies, we then provided a meta-analysis of CMSE, outlining the extent to which it is correlated with teacher-level factors, classroom-level factors and school-level factors. We also used this framework to guide the discussion and to clarify the areas that need further exploration.

Literature Search

This meta-analysis selected empirical research results published in international and Chinese databases between 2000 and 2021. We searched commonly used social science databases (e.g., ERIC, Web of Science, Academic Search Complete, PsycArticles and PsycINFO). Chinese literature was searched mainly from CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure), Wanfang, and Weipu Database. Given the limited number of studies that solely focussed on CMSE, we used the descriptors: " self-efficacy " and/or " efficacy " as keywords, and “ teacher ” and " classroom management " and/or " behaviour management " as abstract search terms. The searches were restricted to return peer-reviewed articles and dissertations (conference papers, books and book chapters were excluded as the review process can be non-standard). In addition to searching databases, we also included an examination of reference lists of the existing reviews of CMSE (Aloe et al., 2014 ; O'Neill & Stephenson, 2011 ).

Eligibility Criteria

The primary studies eligible for inclusion in this meta-analysis met the following criteria: (1) the study measured teacher self-efficacy for classroom management; (2) the study examined the relationship between at least one factors and teachers’ CMSE instead of just reporting descriptive data of CMSE; and (3) the study reported statistical data (e.g., Pearson r , sample size) to quantify the relationship between a factor of interest and teachers’ CMSE. Moreover, given evidence that classroom management content differs between general and special education (Stough, 2006 ) this meta-analysis exclusively examines studies in which (4) the sample comprised of in-service teacher in mainstream school settings. Finally, to facilitate the meta-analysis, (5) correlates included in two or more studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Selection and Inclusion of Studies

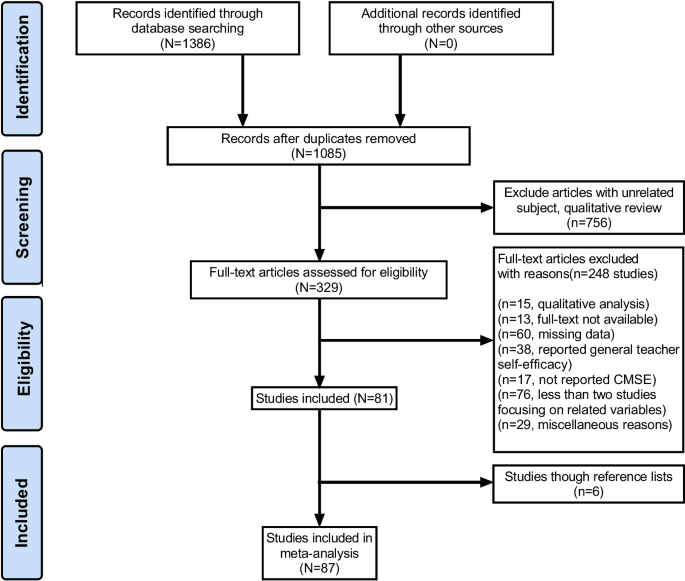

In the first phase of the literature search a total of 1,386 Chinese and English articles were identified using the above search strategy, and 301 duplicates were excluded, resulting in a total of 1085 articles. We went through a three-phase process to screen primary studies included in this meta-analysis as illustrated by Fig. 2 . First, 1,085 studies were examined by reviewing the titles and the abstracts, 756 studies were qualitative research, or not focused on CMSE so were not appropriate to include in the study.

PRISMA flow diagram. Adapted from Moher et al., ( 2009 )

In phase two, 329 articles were left for full-text reading to ensure that studies reported clear, explicit, and complete data on the findings of the research. The result of this examination found that 81 of the research studies in the pool were appropriate, and 248 were found not to be suitable (n=15, qualitative analysis; n=13, full-text not available; n=60, missing data; n=38, reported global TSE; n=17, not reported CMSE; n=76, less than two studies focusing on related variables; N=29, miscellaneous reasons).

In phase three, we backwards searched eligible articles in the reference lists of previous reviews (Aloe et al., 2014 ; O'Neill & Stephenson, 2011 ) and included six additional studies. Of these six studies, the abstracts of five (Bumen, 2010 ; Huk, 2011 ; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2007 ; Williams, 2012 ; Yoon, 2002 ) did not mention the term “classroom management” or “behaviour management” and one (Ozdemir, 2007 ) was not included in commonly used databases, resulting in the omission of these literature from our retrieval. Hence, the present meta-analysis included a sample of 87 primary studies (see supplementary information for details of studies selected).

Study Coding

Studies that met all inclusion criteria were reviewed and all factors associated with teachers’ CMSE in these studies were coded. Studies were coded according to year of publication, publication type, country of origin, school level, CMSE measurement, sample size and reported effect size. Since the primary goal was to synthesize estimates of the relationship between teachers’ CMSE and various factors, the primary effect size we coded was Pearson r. In order to include as many studies as possible, several formulas were used to compute effect sizes (Pearson r):

(1) If only Spearman r was reported in studies, we converted it to Pearson r using the following equation \({r}_s=\frac{6}{\pi }\ {\mathit{\sin}}^{-1}\frac{r}{2}\) (Xiao et al., 2021 ).

(2) If only a β coefficient was reported in studies (β∈(−0.5, 0.5)), then the following equation was used r = β ∗ 0.98 + 0.05( β ≥ 0); r = β ∗ 0.98 − 0.05( β < 0) (Peterson & Brown, 2005 ).

(3) If only a t-test value was reported in studies, then the following equation was used \(r=\sqrt{\frac{t^2}{t^2+ df}}\) (Card, 2012 ).

(4) If studies conducted an ANOVA between two groups (i.e., F (1, df ) ), then the following equation was used \(r=\sqrt{\frac{F_{\left(1, df\right)}}{F_{\left(1, df\right)}+ df}}\) (Card, 2012 ).

(5) If x 2 with 1 degree of freedom was reported in studies, then the following equation was used \(r=\sqrt{\frac{x_{(1)}^2}{N}}\) (Card, 2012 ).

Coding for study characteristics and effect sizes was done by the first author. A randomly selected sample of 50% of the included studies ( K =44) were coded a second time by the first author to establish intracoder reliability (Wilson, 2019 ). Estimates of intracoder reliability were recorded for each variable. The agreement rate was higher than 95% for all variables of interests.

In addition, given that more than one correlation value were reported in some studies, two approaches were used in the determination of which one was to be included in this meta-analysis: (1) if the correlations were independent (e.g., Wettstein et al., 2021 ), all the correlations were included in the analysis and were considered to be independent studies, and (2) if the correlations were dependent (e.g., Lazarides et al., 2020 ), then the highest correlation value was recorded.

Meta-Analytical Procedure

This meta-analysis was conducted with the aid of Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 3.0 Footnote 1 . Pearson's correlation coefficient r was determined to be the effect size in this study. Specifically, r values were firstly converted to Fisher’s Z scale,

then the transformed values were used to calculate the aggregated correlation coefficients, and finally we converted summary Fisher’s Z back to correlation coefficients r to obtain the final overall effect sizes (Borenstein et al., 2009 ).

If the original study only reported r coefficients for each dimension of the variable (e.g., Eddy et al., 2019 ), these coefficients were convert to Fisher’s Z to compute mean scores, and then converted back to r values (Yali et al., 2019 ). A random effect model was used for this meta-analysis because substantial variation exists across studies in terms of various factors that may correlate with teachers’ CMSE.

The following indicators were taken into account in this analysis: k (the number of studies included in the meta-analysis), r (the average effect size expressed in Cohen’s index (Cohen, 1988 ), with values around 0.1 considered a small effect, around 0.25 a medium effect, and 0.4 or higher a large effect), lower limit and upper limit effect sizes (the values of the 95% confident interval), Z values (statistical test for the null hypothesis regarding the average effect size), and the indicators of heterogeneity, namely Q and I 2 .

The Q test is used to test whether the total heterogeneity of the weighted mean effect sizes was statistically significant. The I 2 index provides estimates of the degree of inconsistency in the observed relationship across studies, and values of 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75 indicate low, medium, and high levels of heterogeneity (Borenstein et al., 2009 ). For heterogeneity, we performed moderator analysis. Given evidence that classroom management content differs at different school level (Evertson & Weinstein, 2006 ) moderators tested here included school level. In addition to sample characteristic, the characteristics of the study itself are often also responsible for heterogeneity. Hence, we also included year of publication, publication type, and country of origin as moderators. In the first step in this process subgroup analysis was used for categorical moderators (publication type, country of origin, and school level), which estimated synthetic effects for each category. Specially, we used a Q-test based on analysis of variance to compare subgroups. At the second step, for a non-categorical moderator (year of publication), meta-regression analysis was used to test if the variable was a significant covariate within the meta-regression model.

Characteristics of Included Studies

Based on the eligibility criteria above, 87 primary studies were included in the meta-analysis (see Table 1 ). It is worth noting that most (87.36%) of these eligible 87 studies were published between 2010-2021 and over half (68.97%) of the 87 studies included in this meta-analysis were published in peer-reviewed journals. As can be seen from Table 1 , research on teachers’ CMSE included here was most frequently undertaken in the USA (n=32). Almost half of the included studies (n=49) were conducted with a sample size between 100 and 500 observations. Additionally, three studies used extensive data with more than 100,000 observations (Bellibas & Liu, 2017 ; Fackler et al., 2021 ; Yuan & Jinjie, 2019 ). As for the school level, most studies were conducted with middle school (19), elementary school (14), high school (14), and pre-kindergarten (4) teachers. There were also 4 studies focused on higher education and one was designed for vocational education (Berger et al., 2018 ). The vast majority of studies (n=61) have used the classroom management sub-scale of the Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy Scale (TSES) (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001 ) or its adapted version to access teachers’ CMSE, either its long form (e.g., Sims et al., 2021 ) or short form (e.g., Guangbao & Timothy, 2021 ).

Overall meta-analytic effect sizes

The analysis included 87 samples, 189 correlations, and a total listwise sample size over 480,000. Overall, 22 factors that correlated with CMSE have been generated from these 87 studies (see details of which factors were included in which studies in the supplementary information ). The results of this meta-analysis show small to large correlations between 15 factors and CMSE (see Tables 2 , 3 , 4 ).

Teacher-level Factors

Table 2 presents the overall effects of the association between various teacher-level factors and teachers’ CMSE. Through the eligibility criteria, the present study identified four teacher demographic variables (See Panel A of Table 2 ). Our results showed no evidence that in-service teachers’ sense of self-efficacy in the area of classroom management varied with age, or gender, or educational level. We did find that teachers’ CMSE was positively correlated with teachers’ working experience, which indicated that more experienced teachers hold higher level of CMSE.

In addition to teacher demographic variables, the present study also identified six psychometric constructs of teachers (See Panel B of Table 2 ). Our results showed that all these six factors were significantly correlated with CMSE. Overall, the strongest correlation with CMSE was personal accomplish PA ( r =0.415, CI [0.318, 0.504]). Openness showed the largest correlation among the Big Five personality traits ( r =0.220, CI [0.135, 0.303]), followed by extraversion ( r =0.212, CI [0.121, 0.298]) and conscientiousness ( r =0.121, CI [0.033, 0.207]), whereas agreeableness and neuroticism had no relationship with teacher’ CMSE. Moderate correlations were observed for job satisfaction ( r =0.302, CI [0.255, 0.347]), teacher commitment ( r =0.371, CI [0.198, 0.522]), emotional exhaustion EE ( r =−0.289, CI [−0.349, −0.227]), and depersonalisation DP ( r =−0.281, CI [−0.340 to −0.221]). Teachers’ constructivist beliefs ( r =0.159, CI [0.010, 0.302]) and teacher stress ( r =-0.134, CI [-0.169, -0.098]) were similarly correlated to a small degree.

Classroom-level Factors

Table 3 presents the overall effects of the association between various classroom-level factors and teachers’ CMSE. Our results showed that six classroom-level factors were significantly related to CMSE. There was no significant effect size associated with size of class. Among these six factors showing relationships with significant effect sizes, classroom climate ( r =0.552, CI [0.210, 0.774]) and classroom management practice ( r =0.436, CI [0.108, 0.679]) showed large and positive correlations with CMSE. Moderate correlations were observed for students’ misbehaviours ( r =-0.297, CI [-0.395, -0.192]) and student achievement ( r =0.382, CI [0.307, 0.453]). In terms of classroom interaction, there were four studies included in this meta-analysis. Our results show that all dimensions of classroom interactions were significantly related with teachers’ CMSE with a medium-level effect. For student-teacher relationship, we found that conflict ( r =-0.381, CI [-0.636, -0.050]) negatively related to teachers’ CMSE. Conversely, closeness had no relationship with teacher’ CMSE.

School-level factors

Table 4 presents the overall effects of the association between various school-level characteristics and teachers’ CMSE. This category presents new information about associations among the identified factors and CMSE and contains five distinct factors: principal gender, principal leadership, school type, school size, and school culture. Of these factors we found that only principal leadership and school culture were positively related to teachers’ CMSE, both with a low-level effect.

Moderator analysis

We assessed the heterogeneity of the results using the Q statistic and the I 2 index (see Tables 2 , 3 , 4 ). The Q tests yielded statistically significant results for a total of 11 factors: teacher gender, teacher working experience, job satisfaction, teacher commitment, teacher burnout, classroom climate, classroom management practice, students’ misbehaviour, student-teacher relationship, principal leadership, and school type, which may be influenced by moderators. Of these 11 factors, only seven factors were included in moderator analysis, as fewer than five studies were available for the remaining factors.

Teacher gender

Meta regression suggested that publication year (β=0.006, P=0.613) did not moderate the relationship between teacher gender and their CMSE. Subgroup analyses suggested effects were no different across publication types (Q bet =1.189, P=0.276), or school levels (Q bet =5.628, P=0.344). However, subgroup analysis showed that effects varied across countries (Q bet =53.543, P <0.001).

Teacher working experience

Meta regression suggested that publication year (β=-0.000, P=0.986) did not moderate the relationship between teacher working experience and CMSE. Subgroup analysis suggested publication type did not significantly relate to the correlation outcomes (Q bet =0.063, P=0.802). However, subgroup analyses show that effects varied across countries (Q bet =11850.865, P <0.001), and school levels (Q bet =351.484, P <0.001).

Job satisfaction

Meta regression and subgroup analysis suggested that publication year (β=-0.013, P=0.065) and publication type (Q bet =0.006, P=0.939) did not moderate the relationship between teacher job satisfaction and CMSE. However, other subgroup analyses show that countries (Q bet =11.359, P=0.045) and school level (Q bet =14.649, P=0.002) significantly moderate the relationship between job satisfaction and CMSE.

Teacher burnout

Meta regression suggested that publication year (EE: β=0.005, P=0.308; DP: β=0.008, P=0.091; PA: β=-0.006, P=0.543) did not moderate the relationship between teacher burnout and CMSE. Subgroup analyses suggested that there were no differences in effect across publication types (EE: Q bet =4.690, P=0.030; DP: Q bet =3.530, P=0.060; PA: Q bet =0.805, P=0.370) or school levels (EE: Q bet =2.495, P=0.476; DP: Q bet =2.759, P=0.430; PA: Q bet =4.661, P=0.198). Country, however, emerged as a significant moderator of the relationships between teacher burnout and CMSE (EE: Q bet =27.700, P <0.001; DP: Q bet =25.687, P<0.001; PA: Q bet =44.212, P <0.001).

Classroom management

Meta regression subgroup analysis suggested that publication year (β=0.024, P=0.928) and publication type (Q bet =0.000, P=1.000) did not moderate the relationship between teachers' classroom management practice and their CMSE. However, other subgroup analyses showed that effects varied across countries (Q bet =1204.532, P <0.001), and school levels (Q bet =99.343, P <0.001).

Students’ misbehaviour

Meta regression and subgroup analysis suggested that publication year (β=0.009, P=0.541), publication type (Q bet =0.000, P=1.000) and school levels (Q bet =1.376, P=0.241) did not moderate the relationship between students’ misbehaviour and teachers’ CMSE. However, other subgroup analyses show that effects varied across countries (Q bet =9.245, P=0.026).

Principal leadership

Meta regression and subgroup analyses suggested that there were no differences in effect across publication year (β=-0.009, P=0.459), publication types (Q bet =0.192, P=0.662), or countries (Q bet =0.221, P=0.895). School level, however, emerged as a significant moderator of the relationship between principal leadership and teachers’ CMSE (Q bet =12.792, P=0.002).

Publication bias

In general, articles with positive or statistically significant results are more likely to be published, which can lead to publication bias (Rothstein, 2008 ). Therefore, the present study conducted Egger’s regression test (Egger et al., 1997 ) to assess publication bias (see Table 5 ). Given that less than three studies included teacher personality, constructivist beliefs, class size, students’ achievement, principal gender, school size, school type and school culture, we did not run publication bias procedures on these effect sizes. The results for the analysis of the factors included indicated that there was no publication bias in meta-analyses for most of the factors, with only studies related to teacher educational level showing such bias.

However, for teacher educational level, the trim and fill procedure (Duval & Tweedie, 2000 ) signalled no bias (0 trimmed studies). In addition, the Classic fail-safe N (Rosenthal, 1979 ) test was performed to check the robustness of this finding by computing the number of studies that would be required to nullify the effect. A larger value for this coefficient indicates that we can be confident on the effects, despite the presence of publication bias. Whereas, if the number of missing studies is relatively small then there is indeed cause of concern. The value of fail-safe N of this analysis is 9975, which means that we would need to include 9975 studies to nullify the observed effect. Put another way, publication bias did not pose a threat to the meta-analytic result for teacher educational level.

Discussion and implications

The primary objective of the systematic review was to identify and review the existing evidence regarding factors that correlate with CMSE. A total of 87 studies were included in the review and 22 correlates were identified from these included studies. The findings of the systematic review clustered the factors related to CMSE into three themes (teacher-level factors, classroom-level factors, and school-level factors). Given the number of studies that met inclusion criteria for each analysis ranged from 29 to 2, interpretation of effect sizes derived from the meta-analyses still requires caution.

Turning to the first major strand, we found teacher personal factors are thoroughly examined in CMSE research and 10 teacher-level factors related to CMSE were identified. As for teacher demographic characteristics, our results indicated that teacher gender, teacher age, and teacher educational level were not significantly related to CMSE, the only exception being teacher working experience, for which a positive association was found indicating that more experienced teacher are more likely to hold higher level of confidence about their classroom management ability. Previous research (Brouwers & Tomic, 2000 ; Calkins et al., 2021 ; Fackler et al., 2021 ; Hettinger et al., 2021 ; Hu et al., 2021 ; Klassen & Chiu, 2010 ; Lazarides et al., 2020 ; Tran, 2015 ; Valente et al., 2020 ; Zee et al., 2016 ) reported mixed resulted were found for the relationship between many teacher demographic variables and CMSE. While our synthesis results provide a definitive conclusion in response to the current mixed results, one should be wary as these are conclusions drawn from cross-sectional data, especially for time-related characteristics like teacher age and working experience.

Among these six psychological correlates of CMSE (teacher constructivist beliefs, teacher stress, job satisfaction, teacher commitment, teacher personality and teacher burnout), teacher burnout stood out with a large effect based on a substantial number of studies and large sample size. Job burnout is a psychological syndrome that develops when individuals are under prolonged stressful work conditions, including three dimensions of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and diminished personal accomplishment (Maslach, 2003 ). Fernet et al. ( 2012 ) reported that many teachers have experienced job burnout. Our results suggest that there is a negative relationship between CMSE and the three dimensions of burnout (i.e., emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and diminished personal accomplishment), of which the largest effect is between CMSE and diminished personal accomplishment. This is in line with previous meta-analysis conducted by Aloe et al. ( 2014 ). When CMSE increases, the teacher’s feelings of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization decrease, and feelings of personal accomplishment increase.

Our synthesis results also indicated that teacher commitment and job satisfaction had moderate and positive associations with CMSE, whereas teacher stress had a low and negative association with CSME. These findings were as expected since self-efficacy in classroom management serves as a personal resource and plays an important role in teachers’ stress development or management. Teacher commitment and job satisfaction achieved medium effect (r= 0.302), which indicated classroom management plays a significant role in teachers’ wellbeing. Classroom management has been cited as a significant factor contributing to teacher stress and one of the primary causes of teacher turnover (Aloe et al., 2014 ; Davis, 2018 ). A small effect for teacher stress might be explained by the fact that teacher stress encompasses multiple dimensions (e.g., workload stress and classroom stress) and subsequently, attention should be paid to the relationship between sub-dimensions of teacher stress and CMSE (Klassen & Chiu, 2010 ). Although emotional arousal has been viewed as one of the sources of TSE, it was also suggested that self-efficacy could have a dampening effect on psychological stress arousal (Bandura, 1997 ). The relationship between CMSE and teacher burnout/teacher stress seems clear, however, the directions of these relationship are still unknown. Longitudinal research is highly recommended to clarify the directions.

Lazarides et al. ( 2020 ) suggested that TSE functions as a part of teachers’ personal resources. Attention has been paid to the relationship between teacher personality traits and CMSE, which has been examined among pre-service teachers (Senler & Sungur-Vural, 2013 ; Yingjie & Yan, 2016 ) and in-service teachers (Bullock et al., 2015 ; Rahimi & Saberi, 2014 ). Across these two studies, openness showed the largest correlation among the Big Five personality traits, followed by extraversion and conscientiousness, whereas agreeableness and neuroticism had no relationship with teachers’ CMSE. This finding was partially in line with previous studies (Bullock et al., 2015 ; Rahimi & Saberi, 2014 ), where openness and extraversion were significantly correlated with CMSE, while mixed results were found for conscientiousness, agreeableness and neuroticism. People high in openness are receptive to new things, have a wide range of interests, are imaginative and creative (Xiaoqing, 2013 ), suggesting that teachers rating higher on this trait may have more opportunities to practice new classroom management approaches and be more likely to be persistent in stressful situations. Compared with introverted peers, extroverted teachers are more sociable and self-confident. They may have been more likely to be engaged in various activities (Reeve, 2009 ), more likely to discuss with other teachers about how to manage classroom (Bullock et al., 2015 ), and approach more opportunities to gain experience and improve their ability to promote classroom management self-efficacy. Conscientiousness refers to dependability and the ability to resist impulsive behavior. Teachers with strong conscientiousness often weaken their negative emotions and enhance their positive emotions in their work (Xiaoxian et al., 2014 ). It may appear reasonable to correlate neuroticism with teachers’ CMSE as teachers higher on this trait are more likely to experience anxiety and stress when facing disruptive classroom environment. However, we did not find a relationship between these two. Teachers who are more agreeable are more likely to be empathetic and more pleased to help others. However, we did not find correlation between agreeableness and CSME. This seems to be another indication of the complexity of classroom management, where teachers merely showing care and empathy towards students may not contribute to a well-managed classroom. Considering the limited studies included in this meta-analysis and mixed results found in previous research, we should be cautious about this definitive conclusion. Further research focusing on the relationship between teacher personality traits and CMSE is recommended.

Teachers’ constructivist beliefs about teaching have been viewed as an intrinsic teacher characteristic. Across two studies, our meta-analytic results indicated a small but positive association between teachers’ constructivist beliefs and CMSE. This finding was expected as teachers who hold higher level constructivist beliefs were demonstrated to hold higher level of global TSE (Fackler et al., 2021 ; Fackler & Malmberg, 2016 ). Teachers who hold a high level of constructivist beliefs prefer to use student-centred teaching methods, focus on facilitating students’ learning, and tend to believe they are capable of managing their classroom.

Our meta-analysis showed that almost all classroom characteristics were highly influential in teachers’ CMSE, except class size and closeness in teacher-student relationships. Our synthesised result indicated that CMSE did not relate to class size, however, previous studies (Fackler et al., 2021 ; Kunemund et al., 2020 ) found a significant but negative relationship. This can be explained by the limited number of included studies (only two) potentially leading to unstable findings.

In relation to teachers’ behaviours towards students, one of the most mentioned factors was teachers’ classroom management practice. Our results suggested that CMSE functioned as a personal resource and positively related to positive aspect of classroom management, which is in line with the theoretical assumption of Bandura’s ( 1997 ) self-efficacy theory, self-efficacy acts as a mediating factor between individual behaviour and knowledge. On the other hand, teachers’ appraisals of past performance (e.g., classroom management practice) have been viewed as one of the sources of self-efficacy, however, Morris et al. ( 2017 ) found that teachers reflect on a variety of sources when they reflect on past performance. Instead Morris et al. ( 2017 ) suggested to conceptualize mastery experiences as teachers’ desired goals, such as classroom climate, student achievement, high quality classroom interaction, positive teacher-student relationship.

Classroom climate refers to the instructional and social-emotional environments students live in, which showed a positive relationship with CMSE and had a large effect size. A good classroom climate means teachers have less focus on individual student behaviours, focusing instead on building a positive learning climate. Many studies also paid attention to classroom interaction, as classroom processes are identified as teacher-student interaction pattern that have a significant impact on students’ outcomes (Mashburn et al., 2008 ). The classroom interactions framework (Hamre et al., 2013 ) focuses on teachers’ classroom interactional behaviours in three domains: emotional support, classroom organization, and instructional support. Ryan et al. ( 2015 ) found that American elementary and middle school teachers with higher CMSE tend to exhibit better emotional, behavioural, and instructional support. These findings were also noted in a study on Chinese preschool teachers (Hu et al., 2021 ). Our synthesis results confirmed the moderate and positive relationship between classroom interaction and CMSE among 4 studies, which indicated that teachers who feel confident in their classroom management skills are more likely to provide higher quality emotional support, classroom organization, and instructional support to their students.

One of the most important goals of classroom management is to establish positive student-teacher relationships (Evertson & Weinstein, 2006 ). Our results showed that conflict within teacher-student relationships was negatively related to CMSE and had a medium effect size, while closeness did not show any relationship. Teachers experiencing higher degrees of conflict in their relationships with students are more likely to have stronger emotional vulnerability and result in an increased likelihood of perceived professional and personal failure (Spilt et al., 2011 ), thereby they are at higher risk of developing unhealthy self-efficacy beliefs in classroom management. However, positive aspects of student-teacher relationships (closeness) did not show a positive relationship with CMSE as expected. This seems to indicate that teachers perceived conflict with students would lead to teachers feeling less confident in classroom management, yet being close to students does not make teachers feel empowered in classroom management either. We still need to be cautious about this finding as only three studies were included in this meta-analysis and one previous study (Zee et al., 2017 ) found a significant and positive relationship between closeness and CMSE.

In terms of students’ outcomes, many studies found a positive relationship between teacher general self-efficacy and students’ achievement (Fackler & Malmberg, 2016 ; Malmberg et al., 2014 ), but the focus of the research was rarely on the area of classroom management. Across two studies, we found a moderate and positive relationship between student achievement and CMSE, which further highlights the importance of self-efficacy in classroom management. Response towards student misbehaviour is the key part of managing classrooms and our results showed that student misbehaviour had a moderate and negative association with CMSE, which indicated that teacher with higher level of CMSE are more likely to experience less problem behaviours in the classroom.

Compared to the teacher- and classroom-level characteristics, few school-level factors have been identified and few studies were included in each meta-analysis (range from 2 to 5). We found principal gender does not correlate with CMSE based on two studies, however, one (Fackler et al., 2021 ) found a negative association. Our synthesis results also indicated that principal leadership has a significant impact on teachers' perceptions of CMSE. This suggests that principals play an important role in teachers’ sense of confidence in classroom management however, further research on how principals are of influence is recommended.

School culture is deeply rooted in people's attitudes, values and skills (Sezgin, 2010 ). We found two studies focused on school culture (McLeod, 2012 ; Öztürk et al., 2021 ) and the synthesised result found a small but positive association with CSME. Given individual's sense of efficacy is influenced by their interaction with their environment (Bandura, 1997 ), this supports the connection between environmental conditions (like organizational culture) and CMSE. Our results indicated that teachers’ efficacy beliefs towards classroom management did not differ based on school type (i.e., private vs public) or school size, however, Fackler et al. ( 2021 ) found private and larger schools were positively associated with teachers’ CMSE. This may again be due to the limited number of included studies. Further investigation into the examination of the relationship between school-level factors and their CMSE seems worthwhile.

In addition to the overall effect, we conducted moderator analysis and the results showed that participants’ countries and school levels played a role in moderating the relationship between CMSE and many correlates (e.g., teacher working experience, classroom management, job satisfaction). This may suggest that future research could focus on the differences of CMSE at different teaching levels. Research conducted in different countries proved to be a moderating variable, which supports the call for additional cross-cultural/cross-national studies of TSE (Fackler et al., 2020 ; Vieluf et al., 2013 ).

Teacher self-efficacy towards classroom management is an important facet of teacher self-efficacy, and the mechanisms driving efficacy beliefs toward classroom management remain unclear as a result of inconsistent findings across studies. This meta-analytic review synthesizes the literature over the last two decades to identify factors that correlate with CMSE and to estimate the effect size of these relationships. The findings identified 22 correlates of CMSE and clustered these correlates into three categories: teacher-level factors, classroom-level factors, and school-level factors. Teacher personal factors are thoroughly examined in current CMSE research, while there seems to be a lack of attention on teacher-student interaction and teachers’ working conditions. We identified 10 teacher-level factors including teacher demographic characteristics and psychometric variables. All teacher demographic characteristics except teaching experience were not related to teachers’ CMSE, whereby a positive association was found between level of CMSE and years of teaching experience. Six psychological correlates of CMSE (teacher constructivist beliefs, teacher stress, job satisfaction, teacher commitment, teacher personality and teacher burnout) were identified and most of them showed medium to large correlations with CMSE. Seven classroom-level factors were identified (classroom climate, classroom management, students’ misbehaviour, students’ achievement, classroom interaction, and student-teacher relationship) and almost all factors were significantly related to CMSE, except class size and closeness in teacher-student relationships. Limited studies focused on the relationship between teachers’ working environment and CMSE. Five school-level factors were identified, and only principal leadership and school culture showed a small and positive relationship with CMSE. In addition, sub-group moderation analysis revealed most of these effect sizes differed as a function of participants’ countries and school levels. Future work should focus on exploring more classroom- and school-level factors and conducting cross-cultural comparison research in order to contribute to a comprehensive body of literature. Experimental and longitudinal studies should also be the focus of future CMSE research due to the large amount of correlation work currently contributing to the field. Likewise, reviews of TSE in other specific areas, such as student engagement, instructional strategies and/or inclusive education, are needed to help shed light on those areas where self-perceptions of TSE are more diversified or where it is a global trait.

Limitations

There were some limitations to this study. First, we were selective about the studies included in our meta-analysis. To include relevant correlates of CMSE as comprehensively as possible, correlates included in two or more studies were meta-analysed. The limited number of studies included in some analyses (e.g., school culture, school type, school size) may have an impact on the validity of the synthesis results. A potential second limitation is that we did not place any restriction on the measurement instrument for CMSE and any other psychometric factors. Although previous meta-analyses reported that effect sizes did not vary in studies with different scales (Madigan & Kim, 2021 ), it is still theoretically a potentially important variable. A third potential limitation was that we only provided the correlates of CMSE and we cannot assess the predictors and outcomes. We recommend conducting longitudinal and quasi-experimental research in the future to explore in more depth the directions of these relationships.

Data availability

Data is available on request.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J., & Rothstein, H. (2014). Comprehensive meta-analysis (Version 3.0) [Computer software]. Biostat. https://www.meta-analysis.com/

Aloe, A. M., Amo, L. C., & Shanahan, M. E. (2014). Classroom Management Self-Efficacy and Burnout: A Multivariate Meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 26 (1), 101–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-013-9244-0

Article Google Scholar

Alt, D. (2018). Science teachers' conceptions of teaching and learning, ICT efficacy, ICT professional development and ICT practices enacted in their classrooms. Teaching and Teacher Education, 73 , 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.03.020

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84 (2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action : a social cognitive theory . Prentice-Hall.

Google Scholar

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy : the exercise of control . W.H. Freeman.

Baranczuk, U. (2021). The Five-Factor Model of Personality and Generalized Self Efficacy: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Individual Differences, 42 (4), 183–193. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000345

Bardach, L., Klassen, R. M., & Perry, N. E. (2022). Teachers’ Psychological Characteristics: Do They Matter for Teacher Effectiveness, Teachers’ Well-being, Retention, and Interpersonal Relations? An Integrative Review. Educational psychology review, 34 (1), 259–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09614-9

Bellibas, M. S., & Liu, Y. (2017). Multilevel analysis of the relationship between principals’ perceived practices of instructional leadership and teachers’ self-efficacy perceptions. Journal of Educational Administration, 55 (1), 49–69. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-12-2015-0116

Berger, J.-L., Girardet, C., Vaudroz, C., & Crahay, M. (2018). Teaching Experience, Teachers’ Beliefs, and Self-Reported Classroom Management Practices: A Coherent Network. SAGE Open, 8 (1), 215824401775411. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017754119

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470743386

Book Google Scholar

Brouwers, A., & Tomic, W. (2000). A longitudinal study of teacher burnout and perceived self-efficacy in classroom management. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16 (2), 239–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(99)00057-8

Brown, C. G. (2012). A systematic review of the relationship between self-efficacy and burnout in teachers. Educational and Child Psychology, 29 (4), 47–63 https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84883093990&partnerID=40&md5=194582c37a6022dd84eb8d48d7d9d894

Buentello, O. (2019). A Leader's Impact: The Relationship between School Administrators' Full-Range Leadership Styles and Teachers' Sense of Self-Efficacy . ProQuest Dissertations Publishing https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/leaders-impact-relationship-between-school/docview/2323557058/se-2

Bullock, A., Coplan, R. J., & Bosacki, S. (2015). Exploring links between early childhood educators' psychological characteristics and classroom management self-efficacy beliefs. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 47 (2), 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038547

Bumen, N. T. (2010). The Relationship between Demographics, Self Efficacy, and Burnout among Teachers. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research (EJER), 40 , 16–35.

Calkins, L., Yoder, P. J., & Wiens, P. (2021). Renewed Purposes for Social Studies Teacher Preparation: An Analysis of Teacher Self-Efficacy and Initial Teacher Education. Journal of Social Studies Education Research, 12 (2), 54–77 https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/renewed-purposes-social-studies-teacher/docview/2580843422/se-2

Cantrell, S. C., & Callaway, P. (2008). High and low implementers of content literacy instruction: Portraits of teacher efficacy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24 (7), 1739–1750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.02.020

Card, N. A. (2012). Applied meta-analysis for social science research . Guilford Press.

Chen, R. J.-C., Lin, H.-C., Hsueh, Y.-L., & Hsieh, C.-C. (2020). Which is more influential on teaching practice, classroom management efficacy or instruction efficacy? Evidence from TALIS 2018. Asia Pacific Education Review, 21 (4), 589–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-020-09656-8

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences ED (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

Coladarci, T., & Breton, W. A. (1997). Teacher Efficacy, Supervision, and the Special Education Resource-Room Teacher. The Journal of educational research (Washington, D.C.), 90 (4), 230–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1997.10544577

Davis, J. R. (2018). Classroom Management in Teacher Education Programs ((1st ed) ed.). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63850-8

Dicke, T., Parker, P. D., Marsh, H. W., Kunter, M., Schmeck, A., & Leutner, D. (2014). Self-Efficacy in Classroom Management, Classroom Disturbances, and Emotional Exhaustion: A Moderated Mediation Analysis of Teacher Candidates. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106 (2), 569–583. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035504

Dicke, T., Stebner, F., Linninger, C., Kunter, M., & Leutner, D. (2018). A Longitudinal Study of Teachers' Occupational Well-Being: Applying the Job Demands-Resources Model. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23 (2), 262–277. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000070

Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000). Trim and Fill: A Simple Funnel-Plot–Based Method of Testing and Adjusting for Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis. Biometrics, 56 (2), 455–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x

Eddy, C. L., Herman, K. C., & Reinke, W. M. (2019). Single-item teacher stress and coping measures: Concurrent and predictive validity and sensitivity to change. Journal of School Psychology, 76 , 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2019.05.001

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315 (7109), 629–634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

Emmer, E. T., & Hickman, J. (1991). Teacher Efficacy in Classroom Management and Discipline. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 51 (3), 755–765. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164491513027

Evertson, C. M., & Weinstein, C. S. (2006). Handbook of classroom management : research, practice, and contemporary issues . Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Fackler, S., & Malmberg, L.-E. (2016). Teachers' self-efficacy in 14 OECD countries: Teacher, student group, school and leadership effects. Teaching and Teacher Education, 56 , 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.03.002

Fackler, S., Malmberg, L.-E., & Sammons, P. (2021). An international perspective on teacher self-efficacy: Personal, structural and environmental factors. Teaching and Teacher Education, 99 , 103255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103255

Fackler, S., Sammons, P., & Malmberg, L. E. (2020). A comparative analysis of predictors of teacher self-efficacy in student engagement, instruction and classroom management in Nordic, Anglo-Saxon and East and South-East Asian countries. Review of Education, 9 (1), 203–239. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3242

Fernet, C., Guay, F., Senécal, C., & Austin, S. (2012). Predicting intraindividual changes in teacher burnout: The role of perceived school environment and motivational factors. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28 (4), 514–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.11.013

Ford, L. D. (2019). Comparison of Classroom Management Self-Efficacy of Teachers Based upon Their Certification Type, Principal’S Gender, and Leadership Style: A Quasi-Experimental Vignette Study . ProQuest Dissertations Publishing https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/comparison-classroom-management-self-efficacy/docview/2387272797/se-2

George, S. V., Richardson, P. W., & Watt, H. M. G. (2018). Early career teachers' self-efficacy : A longitudinal study from Australia. The Australian Journal of Education, 62 (2), 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944118779601

Guangbao, F., & Timothy, T. (2021). Investigating the Associations of Constructivist Beliefs and Classroom Climate on Teachers' Self-Efficacy Among Australian Secondary Mathematics Teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 12 , 626271–626271. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.626271

Hamre, B. K., Pianta, R. C., Downer, J. T., DeCoster, J., Mashburn, A. J., Jones, S. M., Brown, J. L., Cappella, E., Atkins, M., Rivers, S. E., Brackett, M. A., & Hamagami, A. (2013). Teaching through Interactions: Testing a Developmental Framework of Teacher Effectiveness in over 4,000 Classrooms. The Elementary School Journal, 113 (4), 461–487. https://doi.org/10.1086/669616

Hassan, M. U. (2019). Teachers' Self-Efficacy: Effective Indicator towards Students' Success in Medium of Education Perspective. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 77 (5), 667–679. https://doi.org/10.33225/pec/19.77.667

Hettinger, K., Lazarides, R., Rubach, C., & Schiefele, U. (2021). Teacher classroom management self-efficacy: Longitudinal relations to perceived teaching behaviors and student enjoyment. Teaching and Teacher Education, 103 , 103349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103349

Hettinger, K., Lazarides, R., & Schiefele, U. (2023). Longitudinal relations between teacher self-efficacy and student motivation through matching characteristics of perceived teaching practice. European Journal of Psychology of Education , 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00744-y

Hicks, S. D. (2012). Self-efficacy and classroom management: A correlation study regarding the factors that influence classroom management . ProQuest Dissertations Publishing https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/self-efficacy-classroom-management-correlation/docview/1030435909/se-2

Holzberger, D., & Prestele, E. (2021). Teacher self-efficacy and self-reported cognitive activation and classroom management: A multilevel perspective on the role of school characteristics. Learning and Instruction, 76 , 101513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2021.101513

Hu, B. Y., Li, Y., Wang, C., Wu, H., & Vitiello, G. (2021). Preschool teachers’ self-efficacy, classroom process quality, and children’s social skills: A multilevel mediation analysis. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 55 , 242–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.12.001

Huk, O. (2011). Predicting teacher burnout as a function of school demands and resources and teacher characteristics . ProQuest Dissertations Publishing https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/predicting-teacher-burnout-as-function-school/docview/912193420/se-2

Klassen, R. M., & Chiu, M. M. (2010). Effects on Teachers' Self-Efficacy and Job Satisfaction: Teacher Gender, Years of Experience, and Job Stress. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102 (3), 741–756. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019237

Klassen, R. M., & Tze, V. M. C. (2014). Teachers’ self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 12 , 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2014.06.001

Klassen, R. M., Tze, V. M. C., Betts, S. M., & Gordon, K. A. (2011). Teacher Efficacy Research 1998—2009: Signs of Progress or Unfulfilled Promise? Educational Psychology Review, 23 (1), 21–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9141-8

Korpershoek, H., Harms, T., de Boer, H., van Kuijk, M., & Doolaard, S. (2016). A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Classroom Management Strategies and Classroom Management Programs on Students' Academic, Behavioral, Emotional, and Motivational Outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 86 (3), 643–680. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315626799

Kunemund, R. L., Nemer McCullough, S., Williams, C. D., Miller, C. C., Sutherland, K. S., Conroy, M. A., & Granger, K. (2020). The mediating role of teacher self-efficacy in the relation between teacher–child race mismatch and conflict. Psychology in the Schools, 57 (11), 1757–1770. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22419

Lazarides, R., Buchholz, J., & Rubach, C. (2018). Teacher enthusiasm and self-efficacy, student-perceived mastery goal orientation, and student motivation in mathematics classrooms. Teaching and Teacher Education, 69 , 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.08.017

Lazarides, R., Watt, H. M. G., & Richardson, P. W. (2020). Teachers’ classroom management self-efficacy, perceived classroom management and teaching contexts from beginning until mid-career. Learning and Instruction, 69 , 101346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101346

Lee, M., & van Vlack, S. (2018). Teachers’ emotional labour, discrete emotions, and classroom management self-efficacy. Educational Psychology, 38 (5), 669–686. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2017.1399199

Liu, S., Xu, X., & Stronge, J. (2018). The influences of teachers’ perceptions of using student achievement data in evaluation and their self-efficacy on job satisfaction: evidence from China. Asia Pacific Education Review, 19 (4), 493–509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-018-9552-7

Looney, L. (2004). Understanding teachers' efficacy beliefs: The role of professional community . ProQuest Dissertations Publishing https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/understanding-teachers-efficacy-beliefs-role/docview/305178139/se-2

Madigan, D. J., & Kim, L. E. (2021). Towards an understanding of teacher attrition: A meta-analysis of burnout, job satisfaction, and teachers’ intentions to quit. Teaching and Teacher Education, 105 , 103425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103425

Main, S., & Hammond, L. (2008). Best practice or most practiced? Pre-service teachers’ beliefs about effective behaviour management strategies and reported self-efficacy. Australian . Journal of Teacher Education, 33 (4), 28–39. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2008v33n4.3

Malmberg, L.-E., Hagger, H., & Webster, S. (2014). Teachers' situation-specific mastery experiences: teacher, student group and lesson effects. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 29 (3), 429–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-013-0206-1

Marschall, G. (2023). Teacher self-efficacy sources during secondary mathematics initial teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 132 , 104203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104203

Mashburn, A. J., Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B. K., Downer, J. T., Barbarin, O. A., Bryant, D., Burchinal, M., Early, D. M., & Howes, C. (2008). Measures of Classroom Quality in Prekindergarten and Childrens Development of Academic, Language, and Social Skills. Child Development, 79 (3), 732–749. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01154.x

Maslach, C. (2003). Job Burnout: New Directions in Research and Intervention. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12 (5), 189–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.01258

McArthur, L., & Munn, Z. (2015). The effectiveness of interventions on the self-efficacy of clinical teachers: a systematic review protocol. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 13 (5), 118–130 http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=ovftq&NEWS=N&AN=01938924-201513050-00011

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (2003). Personality in adulthood a five-factor theory perspective (Second ed.). Guilford Press.

McLeod, R. P. (2012). An Examination of the Relationship between Teachers' Sense of Efficacy and School Culture . ProQuest Dissertations Publishing https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/examination-relationship-between-teachers-sense/docview/1153963088/se-2

Miller, T. M. S. (2020). Teacher Self-Efficacy and Years of Experience: Their Relation to Teacher Commitment and Intention to Leave . ProQuest Dissertations Publishing https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/teacher-self-efficacy-years-experience-their/docview/2488681115/se-2

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Reprint—Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Physical Therapy, 89 (9), 873–880. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/89.9.873

Morris, D. B., Usher, E. L., & Chen, J. A. (2017). Reconceptualizing the Sources of Teaching Self-Efficacy: a Critical Review of Emerging Literature. Educational Psychology Review, 29 (4), 795–833. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-016-9378-y

OECD (2014), TALIS 2013 Results: An international perspective on teaching and learning, TALIS, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264196261-en

O'Neill, S. C., & Stephenson, J. (2011). The measurement of classroom management self-efficacy: a review of measurement instrument development and influences. Educational Psychology, 31 (3), 261–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2010.545344

Ozdemir, Y. (2007). The Role of Classroom Management Efficacy in Predicting Teacher Burnout. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, Open Science Index 11. International Journal of Educational and Pedagogical Sciences, 1 (11), 751–757.

Öztürk, M., Bulut, M. B., & Yildiz, M. (2021). Predictors of Teacher Burnout in Middle Education: School Culture and Self-Efficacy. Studia Psychologica, 63 (1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.31577/SP.2021.01.811

Peterson, R. A., & Brown, S. P. (2005). On the Use of Beta Coefficients in Meta-Analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90 (1), 175–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.175

Rahimi, A., & Saberi, M. (2014). The Interface between Iranian EFL Instructors' Personality and Their Self-Efficacy. Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 5 (3), 134–142. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.5n.3p.134

Raudenbush, S. W., Rowan, B., & Cheong, Y. F. (1992). Contextual Effects on the Self-perceived Efficacy of High School Teachers. Sociology of Education, 65 (2), 150–167. https://doi.org/10.2307/2112680

Reeve, J. (2009). Why Teachers Adopt a Controlling Motivating Style Toward Students and How They Can Become More Autonomy Supportive. Educational Psychologist, 44 (3), 159–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520903028990

Reilly, J. C. (2002). Differentiating the concept of teacher efficacy for academic achievement, classroom management and discipline, and enhancement of social relations . ProQuest Dissertations Publishing https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/differentiating-concept-teacher-efficacy-academic/docview/275767484/se-2

Riggs, I. M., & Enochs, L. G. (1990). Toward the development of an elementary teacher's science teaching efficacy belief instrument. Science Education (Salem, Mass.), 74 (6), 625–637. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.3730740605

Rosenthal, R. (1979). The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin, 86 (3), 638–641. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.86.3.638

Rothstein, H. R. (2008). Publication bias as a threat to the validity of meta-analytic results. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 4 (1), 61–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-007-9046-9

Ryan, A. M., Kuusinen, C. M., & Bedoya-Skoog, A. (2015). Managing peer relations: A dimension of teacher self-efficacy that varies between elementary and middle school teachers and is associated with observed classroom quality. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41 , 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.01.002

Schwerdtfeger, A., Konermann, L., & Schönhofen, K. (2008). Self-efficacy as a health-protective resource in teachers?: A biopsychological approach. Health Psychology, 27 (3), 358–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.358

Senler, B., & Sungur-Vural, S. (2013). Pre-Service Science Teachers’ Teaching Self-Efficacy in Relation to Personality Traits and Academic Self-Regulation. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 16 , E12–E12. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2013.22

Sezgin, F. (2010). School Organizational Culture as a Predictor of Teacher Organizational Commitment. Egitim ve Bilim, 35 (156), 142 https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/school-organizational-culture-as-predictor/docview/1009841902/se-2

Sims, W. A., King, K. R., Reinke, W. M., Herman, K., & Riley-Tillman, T. C. (2021). Development and Preliminary Validity Evidence for the Direct Behavior Rating-Classroom Management (DBR-CM). Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 31 (2), 215–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/10474412.2020.1732990

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2007). Dimensions of Teacher Self-Efficacy and Relations With Strain Factors, Perceived Collective Teacher Efficacy, and Teacher Burnout. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99 (3), 611–625. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.611

Spilt, J. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., & Thijs, J. T. (2011). Teacher Wellbeing: The Importance of Teacher—Student Relationships. Educational Psychology Review, 23 (4), 457–477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9170-y

Stough, L. M. (2006). The Place of Classroom Management and Standards in Teacher Education. In C. M. E. C. S. Weinstein (Ed.), Handbook of classroom management : research, practice, and contemporary issues . Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Sutton, R. E., Mudrey-Camino, R., & Knight, C. C. (2009). Teachers' Emotion Regulation and Classroom Management. Theory Into Practice, 48 (2), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405840902776418

Tran, V. D. (2015). Effects of Gender on Teachers’ Perceptions of School Environment, Teaching Efficacy, Stress and Job Satisfaction. International Journal of Higher Education, 4 (4), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v4n4p147

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17 (7), 783–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2007). The differential antecedents of self-efficacy beliefs of novice and experienced teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23 (6), 944–956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.05.003

Tschannen-Moran, M., Hoy, A. W., & Hoy, W. K. (1998). Teacher Efficacy: Its Meaning and Measure. Review of Educational Research, 68 (2), 202–248. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543068002202

Usher, E. L., & Pajares, F. (2008). Sources of Self-Efficacy in School: Critical Review of the Literature and Future Directions. Review of Educational Research, 78 (4), 751–796. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308321456

Valente, S., Lourenço, A. A., Alves, P., & Dominguez-Lara, S. (2020). The role of the teacher's emotional intelligence for efficacy and classroom management. Revista CES Psicología, 13 (2), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.21615/CESP.13.2.2

Vidic, T., Duranovic, M., & Klasnic, I. (2021). Student Misbehaviour, Teacher Self-Efficacy, Burnout And Job Satisfaction: Evidence From Croatia. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 79 (4), 657–673. https://doi.org/10.33225/pec/21.79.657

Vieluf, S., Kunter, M., & van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2013). Teacher self-efficacy in cross-national perspective. Teaching and Teacher Education, 35 , 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.05.006

von der Embse, N. P., Sandilos, L. E., Pendergast, L., & Mankin, A. (2016). Teacher stress, teaching-efficacy, and job satisfaction in response to test-based educational accountability policies. Learning And Individual Differences, 50 , 308–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.08.001

Wettstein, A., Ramseier, E., & Scherzinger, M. (2021). Class- and subject teachers’ self-efficacy and emotional stability and students’ perceptions of the teacher–student relationship, classroom management, and classroom disruptions. BMC Psychology, 9 (1), 1–103. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00606-6

Williams, A. Y. (2012). Applications of Dweck's model of implicit theories to teachers' self-efficacy and emotional experiences . ProQuest Dissertations Publishing https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/applications-dwecks-model-implicit-theories/docview/1178991009/se-2

Wilson, D. B. (2019). Systematic Coding For Research Synthesis. In H. Cooper, L. V. Hedges, & J. C. Valentine (Eds.), The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis (pp. 153–172). Russell Sage Foundation. https://doi.org/10.7758/9781610448864.12

Chapter Google Scholar

Woodcock, S., Sharma, U., Subban, P., & Hitches, E. (2022). Teacher self-efficacy and inclusive education practices: Rethinking teachers’ engagement with inclusive practices. Teaching and Teacher Education, 117 , 103802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103802

Woolfolk, A. E., & Hoy, W. K. (1990). Prospective Teachers' Sense of Efficacy and Beliefs About Control. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82 (1), 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.82.1.81