An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Can J Public Health

- v.110(3); 2019 Jun

Language: English | French

Why public health matters today and tomorrow: the role of applied public health research

Lindsay mclaren.

1 University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada

Paula Braitstein

2 University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

David Buckeridge

3 McGill University, Montreal, Canada

Damien Contandriopoulos

4 University of Victoria, Victoria, Canada

Maria I. Creatore

5 CIHR Institute of Population & Public Health and University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

Guy Faulkner

6 University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada

David Hammond

7 University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Canada

Steven J. Hoffman

8 CIHR Institute of Population & Public Health and York University, Toronto, Canada

Yan Kestens

9 Université de Montréal, Montreal, Canada

Scott Leatherdale

Jonathan mcgavock.

10 University of Manitoba and the Children’s Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada

Wendy V. Norman

11 University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada

Candace Nykiforuk

12 University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada

Valéry Ridde

13 IRD (French Institute For Research on Sustainable Development), CEPED (IRD-Université Paris Descartes), ERL INSERM SAGESUD, Université Paris Sorbonne Cités, Paris, France

14 University of Montreal Public Health Research Institute (IRSPUM), Montreal, Canada

Janet Smylie

Public health is critical to a healthy, fair, and sustainable society. Realizing this vision requires imagining a public health community that can maintain its foundational core while adapting and responding to contemporary imperatives such as entrenched inequities and ecological degradation. In this commentary, we reflect on what tomorrow’s public health might look like, from the point of view of our collective experiences as researchers in Canada who are part of an Applied Public Health Chairs program designed to support “innovative population health research that improves health equity for citizens in Canada and around the world.” We view applied public health research as sitting at the intersection of core principles for population and public health: namely sustainability, equity, and effectiveness. We further identify three attributes of a robust applied public health research community that we argue are necessary to permit contribution to those principles: researcher autonomy, sustained intersectoral research capacity, and a critical perspective on the research-practice-policy interface. Our intention is to catalyze further discussion and debate about why and how public health matters today and tomorrow, and the role of applied public health research therein.

Résumé

La santé publique est essentielle à une société saine, juste et durable. Pour donner forme à cette vision, il faut imaginer une communauté de la santé publique capable de préserver ses valeurs fondamentales tout en s’adaptant et en réagissant aux impératifs du moment, comme les inégalités persistantes et la dégradation de l’environnement. Dans notre commentaire, nous esquissons un portrait possible de la santé publique de demain en partant de notre expérience collective de chercheurs d’un programme canadien de chaires en santé publique appliquée qui visent à appuyer « la recherche innovatrice sur la santé de la population en vue d’améliorer l’équité en santé au Canada et ailleurs ». Nous considérons la recherche appliquée en santé publique comme se trouvant à la croisée des principes fondamentaux de la santé publique et des populations, à savoir : la durabilité, l’équité et l’efficacité. Nous définissons aussi les trois attributs d’une solide communauté de recherche appliquée en santé publique nécessaires selon nous au respect de ces principes : l’autonomie des chercheurs, une capacité de recherche intersectorielle soutenue et une perspective critique de l’interface entre la recherche, la pratique et les politiques. Nous voulons susciter des discussions et des débats approfondis sur l’importance de la santé publique pour aujourd’hui et pour demain et sur le rôle de la recherche appliquée en santé publique.

Introduction

Public health is critical to a healthy, fair, and sustainable society. Public health’s role in this vision stems from its foundational values of social justice and collectivity (Rutty and Sullivan 2010 ) and—we argue—from its position at the interface of research, practice, and policy.

Realizing this vision requires imagining a public health community that can maintain that foundational core, embrace opportunities of our changing world, and predict and adapt to emerging challenges in a timely manner. Unprecedented ecosystem disruption creates far-reaching health implications for which the public health community is unprepared (CPHA 2015 ; Whitmee et al. 2015 ). Human displacement is at its highest levels on record; those forced from home include “stateless people,” who are denied access to basic rights such as education, health care, employment, and freedom of movement ( http://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html ). Significant growth in urban populations creates an urgent need to improve urban environments, including policies to reduce air pollution and prevent sprawl (CPHA 2015 ; Frumkin et al. 2004 ), to reduce the substantial burden of morbidity and mortality attributable to behaviours such as physical inactivity, which negatively impact quality and quantity of life (Manuel et al. 2016 ). Significant and entrenched forms of economic, social, political, and historical marginalization and exclusion (TRC 2015 ), coupled with inequitable and unsustainable patterns of resource consumption and technological development (CPHA 2015 ; Whitmee et al. 2015 ), cause and perpetuate health inequities. These inequities underlie the now longstanding recognition that the unequal distributions of health-damaging experiences are the main determinants of health (CSDH 2008 ; Ridde 2004 ).

These imperatives demand a broadly characterized public health community. A now classic definition of public health is the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting health through the organized efforts of society (Last 2001 ). Public health, conceptualized in this manner, engages multiple sectors, embraces inclusion and empowerment (Ridde 2007 ), and demands navigating diverse political and economic agendas. Across Canada, a large and growing proportion of provincial spending is devoted to health care, while the proportion devoted to social spending (i.e., the social determinants of health) is small, flat-lining, and in some places declining (Dutton et al. 2018 ). Recent discourse has highlighted a weakening of formal public health infrastructure (Guyon et al. 2017 ) and points of fracture within the field (Lucyk and McLaren 2017 ). Efforts to strengthen public health, in its broadest sense, and to work towards unity of purpose (Talbot 2018 ) are needed now more than ever. What might such efforts look like?

We reflect on this question from our perspectives as researchers who are part of an Applied Public Health Chairs (APHC) program designed to support “innovative population health research that improves health equity for citizens in Canada and around the world.” 1 The applied dimension 2 is facilitated through the program’s focus on “interdisciplinary collaborations and mentorship of researchers and decision makers in health and other sectors” ( http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48898.html ). The APHC program (Box 1) is part of a broader set of efforts to address gaps in public health capacity, including research. Cross-cutting themes for the 2014 cohort (Box 2) include the following: healthy public policy, supportive environments (e.g., cities), diverse methodological approaches, global health, and health equity; many of which 3 align with a Public Health Services and Systems Research perspective in that they “identif[y] the implementation strategies that work, building evidence to support decision-making across the public health sphere” ( http://www.publichealthsystems.org/ ). Applied public health research is broad and could span CIHR Pillars 4 (social, cultural, environmental, and population health research) and 3 (health services research); the 2014 APHC cohort is predominantly aligned with Pillar 4.

The APHC program represents a significant Canadian investment in public health, and thus provides an important vantage point from which to reflect on why public health matters today, and tomorrow.

Box 1 The Applied Public Health Chairs program

Box 2 2014 cohort of Applied Public Health Chairs

More details available at: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48898.html

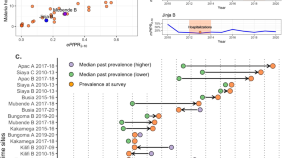

Our proposal

We propose that applied public health research is a critical component of a robust population and public health community. As illustrated in Fig. 1 , we view applied public health research as sitting at the nexus of three core principles: (1) sustainability, (2) equity, and (3) effectiveness, which align with a vision of public health as critical to a healthy, fair, and sustainable society. By sustainability , we mean an approach or way of thinking, about public health in particular (e.g., Schell et al. 2013 ) and population well-being more broadly ( https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs ) that emphasizes “meet[ing] the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Brundtland et al. 1987 ). Sustainability has social, economic, environmental, and political dimensions. We define equity as a worldview concerned with the embedded or systemic—and often invisible—drivers of unfair distributions of health-damaging experiences. In Canada and elsewhere, inequity is entrenched in legacies of colonial, structural racism designed to sustain inequitable patterns of power and wealth. Equity transcends diverse axes and perspectives, and an equity lens is action-oriented (Ridde 2007 ). Finally, effectiveness refers to impact or benefits for population well-being, as demonstrated by rigorous research. Explicit core values (e.g., equity), while important, are insufficient without translation to demonstrable outcomes (Potvin and Jones 2011 ). These core principles—sustainability, equity, and effectiveness—overlap and are mutually reinforcing; for example, the inequitable concentration of power, wealth, and exploitation of resources precludes sustainability.

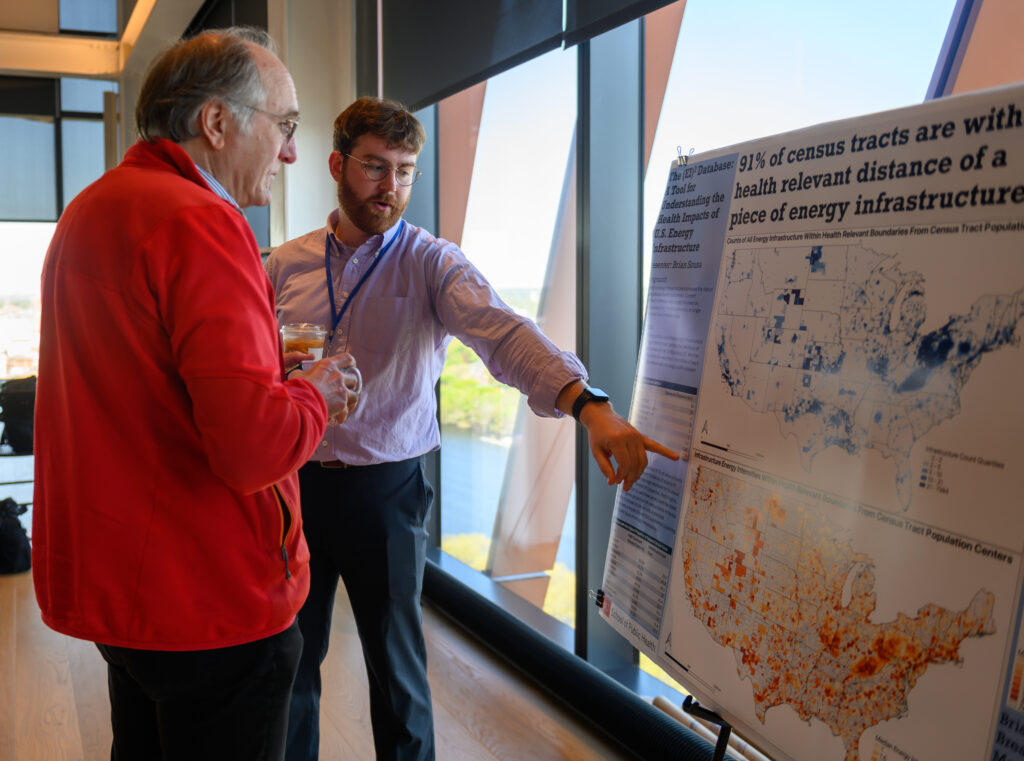

Visual depiction of the role and attributes of applied public health research, vis-à-vis core population and public health principles of equity, sustainability, and effectiveness

Although these principles are applicable to the public health community broadly (i.e., including but not limited to researchers), applied public health researchers are uniquely situated to embrace sustainability, equity, and effectiveness when asking questions and generating policy- and practice-relevant knowledge, as illustrated below. Drawing on our collective experiences, we describe three necessary attributes of applied public health research that support our model in Fig. 1 : researcher autonomy, sustained intersectoral research capacity; and a critical perspective on the research-practice-policy interface. We assert that applied public health research is best positioned to contribute meaningfully to the principles of sustainability, effectiveness, and equity if the attributes described below are in place.

Researcher autonomy

Researcher autonomy is a precondition for innovation and independent thinking, and for building and sustaining the conditions for collective efforts. Our working definition of researcher autonomy is the capacity to devote time and energy to activities that, at the researcher’s discretion, facilitate research that embraces principles of sustainability, effectiveness, and equity. Autonomy, beyond the scope of general academic independence, provides the freedom to build and nurture partnerships, and to navigate among universities, health care systems, governments, communities, and across sectors. Effective and respectful partnerships are critical to rigorous intersectoral work and can provide an important platform to discuss systemic forms of inequity (e.g., Olivier et al. 2016 ; Morton Ninomiya et al. 2017 ). Recognizing a potential tension around the role of the researcher in an applied public health context, we deliberately selected the word “autonomy,” which we view as conducive to meaningful collaboration (although that may be experienced differently by different researchers), rather than “independence” which can be seen as contrary to such collaboration. Yet despite their importance, the time and resources to form and sustain those relationships are often not accommodated within funding and academic structures.

Autonomy, when coupled with resources and recognition, permits applied public health researchers to balance foundations of public health with current policy relevance. Although many of us have research programs with particular thematic foci (e.g., physical activity, dental health, HIV), autonomy provides space and credibility to connect those focal issues to enduring and evolving problems in public health (e.g., determinants of population well-being and equity), and to inform the contemporary policy context. Examples include research on health implications of neighbourhood gentrification in urban settings (Steinmetz-Wood et al. 2017 ); using community water fluoridation as a window into public and political understanding and acceptance of public health interventions that are universal in nature (McLaren and Petit 2018 ); and using innovative sampling methods to identify how census methods can perpetuate exclusion (Rotondi et al. 2017 ). That latter work, which estimated that the national census undercounts urban Indigenous populations in Toronto by a factor of approximately 2–4, provides impetus to work towards an inclusive system that respects individual and collective data sovereignty, and that is accountable to the communities from whom data are collected.

These implications of autonomy are consistent with calls for greater reflexivity in public health research (Tremblay and Parent 2014 ).

Insight : To strengthen applied public health research in Canada, researcher autonomy – whereby researchers have the credibility and protected time to set their own agendas in partnerships with the communities they serve – must be privileged.

Sustained intersectoral research capacity

Applied public health research requires funding for resources and infrastructure that are essential to sustain an intersectoral research program, but for which operating funds are otherwise not readily available. Examples include ongoing cohort studies (e.g., Leatherdale et al. 2014 ), research software platforms (e.g., Shaban-Nejad et al. 2017 ), meaningful public sector engagement in developing public health priorities, and knowledge translation activities.

Partnerships, also considered under researcher autonomy above, are one form of intersectoral research capacity. In applied public health research, having strong partnerships in place permits timely response to research opportunities that arise quickly in real-world settings. Examples in our cohort include instances where researchers were able to mobilize for rapid response funding competitions in areas of environment and health, communicable disease in the global South, and Indigenous training networks, because collaborative teams and potential for knowledge co-creation and transfer were already in place.

Insight : A robust applied public health research community requires sustained funding to support foundations of a credible and internationally-competitive research program (e.g., cohort studies, research software platforms, meaningful public sector engagement) that are difficult to resource via usual operating grant channels.

A critical perspective on the research-practice-policy interface

One barrier to evidence-based policy in applied public health is an assumption that evidence is the most important factor in making policy decisions, versus a more holistic view of the policymaking process where evidence is one of many factors, as discussed in recent work (Fafard and Hoffman 2018 ; O’Neill et al. 2019 ; Ridde and Yaméogo 2018 ).

Applied public health research is ideally positioned to embrace a critical perspective on the research-practice-policy interface. Several recent trends are promising in that regard. These include the following: substantive efforts to bridge public health and social science scholarship ( http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/50604.html ), growing success by Pillar 4 researchers (including applied public health) in CIHR’s open funding competitions ( http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/50488.html ), and the CIHR Health System Impact Fellowship initiative ( http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/50612.html ), which could facilitate the placement of doctoral and post-doctoral academic researchers within the public health system and related (e.g., public, NGO) organizations.

Insight : Applied public health researchers are ideally positioned to embrace and model a sophisticated and interdisciplinary perspective on the research-practice-policy interface. To do so, opportunities for researchers (including trainees) to gain skills and experience to navigate the policy context are needed.

Against the backdrop of discourse about a weakening of public health infrastructure and fracture within the field (Guyon et al. 2017 ; Lucyk and McLaren 2017 ), we believe that there is value in working towards a unity of purpose (Talbot 2018 ). This commentary was prompted by a shared belief that through our experience with the Applied Public Health Chair Program, we have seen a glimpse of what is needed to achieve a population and public health community that is positioned to tackle societal imperatives, which includes an important role for applied public health research, spanning CIHR Pillars 3 and 4. Anchored in principles of sustainability, equity, and effectiveness, we assert a strong need for applied research infrastructure that privileges and supports: researcher autonomy, sustained funding to support foundations of a credible and internationally competitive research program, and opportunities for researchers (including trainees) to gain skills and experience to navigate the policy context. We welcome and invite further discussion and debate.

1 Under CIHR-IPPH’s mandate, population health research refers to “research into the complex biological, social, cultural, and environmental interactions that determine the health of individuals, communities, and global populations.”

2 Applied may be defined as follows: “put to practical use,” as opposed to being theoretical ( https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/applied ).

3 For example: https://uwaterloo.ca/compass-system/ (Leatherdale); http://cart-grac.ubc.ca/ (Norman); http://www.healthsystemsglobal.org/ (Ridde).

The original version of this article was revised due to a retrospective Open Access order.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

The article ���Why public health matters today and tomorrow: the role of applied public health research,��� written by Lindsay McLaren et al., was originally published Online First without Open Access.

- Brundtland G, Khalid M, Agnelli S, Al-Athel S, Chidzero B, Fadika L, Hauff V, Lang I, Shijun M, Morino de Botero M, Singh M, Okita S, and et al. (1987). Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future (‘Brundtland report’). United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development.

- Canadian Public Health Association Discussion Paper . Global change and public health: Addressing the ecological determinants of health. Ottawa: Canadian Public Health Association; 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) (2008) . Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization. [ PubMed ]

- Dutton DJ, Forest P-G, Kneebone RD, Zwicker JD. Effect of provincial spending on social services and health care on health outcomes in Canada: an observational longitudinal study. CMAJ. 2018; 190 (3):E66–E71. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170132. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fafard, P., & Hoffman, S. J. (2018). Rethinking knowledge translation for public health policy. Evidence & Policy . 10.1332/174426418X15212871808802.

- Frumkin H, Frank L, Jackson R. Urban sprawl and public health: designing, planning and building for healthy communities. Washington: Island Press; 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Guyon, A., Hancock, T., Kirk, M., MacDonald, J., Neudorf, C., Sutcliffe, P., Talbot, J., Watson-Creed, G. (2017). The weakening of public health: a threat to population health and health care system sustainability. Can J Public Health, 108 (1), 1–6. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Last JM, editor. A dictionary of epidemiology (4th ed) Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- Leatherdale ST, Brown KS, Carson V, Childs RA, Dubin JA, Elliott SJ, Faulkner G, Hammond D, Manske S, Sabiston CM, Laxer RE, Bredin C, Thompson-Haile A. The COMPASS study: a longitudinal hierarchical research platform for evaluating natural experiments related to changes in school-level programs, policies and build environment resources. BMC Public Health. 2014; 14 :331. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-331. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lucyk K, McLaren L. Is the future of “population/public health” in Canada united or divided? Reflections from within the field. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy and Practice. 2017; 37 (7):223–227. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.37.7.03. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Manuel DG, Perez R, Sanmartin C, Taljaard M, Hennessy D, Wilson K, Tanuseputro P, Manson H, Benett C, Tuna M, Fisher S, Rosella LC. Measuring burden of unhealthy behaviours using a multivariable predictive approach: life expectancy lost in Canada attributable to smoking, alcohol, physical inactivity, and diet. PLoS Med. 2016; 13 (8):e1002082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002082. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McLaren L, Petit R. Universal and targeted policy to achieve health equity: a critical analysis of the example of community water fluoridation cessation in Calgary, Canada in 2011. Crit Public Health. 2018; 28 (2):153–164. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2017.1361015. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morton Ninomiya ME, Atkinson D, Brascoupé S, Firestone M, Robinson N, Reading J, Ziegler CP, Maddox R, Smylie JK. Effective knowledge translation approaches and practices in indigenous health research: a systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews. 2017; 6 (1):34. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0430-x. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- O’Neill B, Kapoor T, McLaren L. Politics, science and termination: a case study of water fluoridation in Calgary in 2011. Rev Policy Res. 2019; 36 (1):99–120. [ Google Scholar ]

- Olivier C, Hunt MR, Ridde V. NGO-researcher partnerships in global health research: benefits, challenges, and approaches that promote success. Dev Pract. 2016; 26 (4):444–455. doi: 10.1080/09614524.2016.1164122. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Potvin L, Jones CM. Twenty-five years after the Ottawa charter: the critical role of health promotion for public health. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2011; 102 (4):244–248. doi: 10.1007/BF03404041. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ridde V. Une analyse comparative entre le Canada, le Québec et la France: l’importance des rapports sociaux et politiques eu égard aux determinants et aux inégalités de la santé L’antilibéralisme. 2004; 45 (2):343–364. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ridde V. Réduire les inégalités sociales de santé: santé publique, santé communautaire ou promotion de la santé? Promot Educ. 2007; XIV (2):111–114. doi: 10.1177/10253823070140020601. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ridde V, Yaméogo P (2018). How Burkina Faso used evidence in deciding to launch its policy of free healthcare for children under five and women in 2016. Palgrave Communications ;119(4).

- Rotondi MA, O’Campo P, O’Brien K, Firestone M, Wolfe SH, Bourgeois C, Smylie JK. Our Health Counts Toronto: using respondent-driven sampling to unmask census undercounts of an urban indigenous population in Toronto, Canada. BMJ Open. 2017; 7 :e018936. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018936. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rutty C, Sullivan SC. This is public health: A Canadian history. Ottawa: Canadian Public Health Association; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schell SF, Luke DA, Schooley MW, Elliott MB, Herbers SH, Mueller NB, Bunger AC. Public health program capacity for sustainability: A new framework. Implement Sci. 2013; 8 :15. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-15. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shaban-Nejad A, Lavigne M, Okhmatovskaia A, Buckeridge DL. PopHR: a knowledge-based platform to support integration, analysis, and visualization of population health data. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2017; 1387 (1):44–53. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13271. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Steinmetz-Wood M, Wasfi R, Parker G, Bornstein L, Caron J, Kestens Y. Is gentrification all bad? Positive association between gentrification and individual’s perceived neighbourhood collective efficacy in Montreal, Canada. International Journal of Health Geographics. 2017; 16 (1):24. doi: 10.1186/s12942-017-0096-6. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Talbot J. (2018). Keynote presentation at Campus Alberta 2018 annual conference, In defense of public health: identifying opportunities to strengthen our field. Calgary, May 9.

- Tremblay MC, Parent AA. Reflexivity in PHIR: let’s have a reflexive talk! Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2014; 105 (3):e221–e223. doi: 10.17269/cjph.105.4438. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Truth and Reconciliation Canada (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada . Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

- Whitmee S, Haines A, Beyrer C, Boltz F, Capon AG, Berreira de Souza Dias B, Frumkin H, Gong P, Head P, Horton R, Mace GM, Marten R, Myers SS, Nishtar S, Osofsky SA, Pattanayak SK, Pongsiri MJ, Romanelli C, Soucat A, Vega J, Yach D. Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: report of The Rockefeller Foundation-Lancet ommission on planetary health. Lancet. 2015; 386 (10007):1973–2028. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60901-1. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Public health articles from across Nature Portfolio

Public health is the medical discipline concerned with the prevention and control of disease through population surveillance and the promotion of healthy behaviours. Strategies used to promote public health include patient education, the administration of vaccines, and other components of preventive medicine.

Related Subjects

- Epidemiology

- Population screening

Latest Research and Reviews

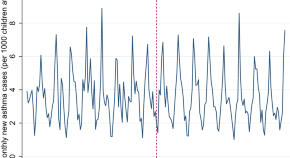

Tobacco control policies and respiratory conditions among children presenting in primary care

- Timor Faber

- Luc E. Coffeng

- Jasper V. Been

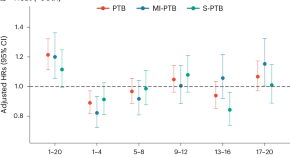

Heat exposure induced risks of preterm birth mediated by maternal hypertension

Findings from a multicenter study of 197,080 singleton live births in China show maternal hypertension as a mediator of the risks imposed by heat exposure between conception and 20 weeks of gestation on preterm birth and its various clinical subtypes.

- Cunrui Huang

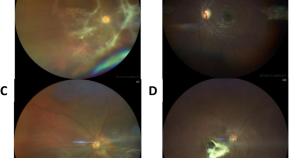

Clinical characteristics and aetiology of uveitis in a viral haemorrhagic fever zone

- Shiama Balendra

- Lloyd Harrison-Williams

- Alasdair Kennedy

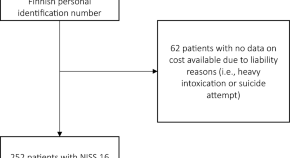

Cumulative costs of severe traffic injuries in Finland: a 2-year retrospective observational study of 252 patients

- Antti Riuttanen

- Erkka Karjalainen

- Ville M. Mattila

Severe outcomes of malaria in children under time-varying exposure

Severe pediatric malaria remains a concern in many countries. Here, the authors use an individual-based modeling approach to evaluate the relationship between malaria prevalence and incidence of malaria pediatric hospitalizations, and show how unsteady transmission patterns affect hospitalization rates.

- Pablo M. De Salazar

- Alice Kamau

- Melissa A. Penny

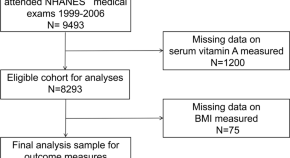

Association between serum vitamin A and body mass index in adolescents from NHANES 1999 to 2006

- Nishant Patel

News and Comment

Neglecting sex and gender in research is a public-health risk

The data are clear: taking sex and gender into account in research and using that knowledge to change health care could benefit billions of people.

- Cheryl Carcel

- Robyn Norton

Interpersonal therapy can be an effective tool against the devastating effects of loneliness

- Myrna M. Weissman

- Jennifer J. Mootz

Is the Internet bad for you? Huge study reveals surprise effect on well-being

A survey of more than 2.4 million people finds that being online can have a positive effect on welfare.

- Carissa Wong

Talking about climate change and health

The climate crisis is also an urgent and ongoing health crisis with diverse human impacts leading to physical, mental and cultural losses. Translating knowledge into action involves broad collaboration, which relies heavily on careful communication of a personal and politicized issue.

Considering health can drive climate action

Last December saw the inaugural Health Day at a Climate Conference of the Parties (COP) and the announcement of the COP28 UAE Declaration on Climate and Health, marking a substantial step in global recognition of the intersecting crises of climate change and health . Nature Climate Change speaks to Maria Neira, director of the Department of Environment, Climate Change and Health at the World Health Organization, about successes and next steps.

- Tegan Armarego-Marriott

How ignorance and gender inequality thwart treatment of a widespread illness

Tens of millions of people have female genital schistosomiasis, a neglected tropical disease that few physicians have even heard of. Efforts are under way to move it out of obscurity and empower women and girls to access sexual and reproductive health care.

- Claire Ainsworth

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

BMC Public Health

Latest collections open to submissions, new: improving the health of incarcerated people.

Guest edited by Jaimie P. Meyer and Heino Johann Stöver

NEW: Exploring barriers to oral health care

Guest Edited by Heather Leggett

NEW: Workplace safety and health

Guest edited by Els Clays, Subas Neupane and Karin Proper

Menstrual health education

Guest edited by HuiJun Chih and Sonia Regina Grover

Editors' picks

- Most accessed

Temporal change in prevalence of BMI categories in India: patterns across States and Union territories of India, 1999–2021

Authors: Meekang Sung, Akhil Kumar, Raman Mishra, Bharati Kulkarni, Rockli Kim and S. V. Subramanian

Unlocking the potential: exploring the impact of dolutegravir treatment on body mass index improvement in underweight adults with HIV in Malawi

Authors: Thulani Maphosa, Shalom Dunga, Lucky Makonokaya, Godfrey Woelk, Alice Maida, Alice Wang, Allan Ahimbisibwe, Rachel K. Chamanga, Suzgo B. Zimba, Dumbani Kayira and Rhoderick Machekano

Sociodemographic determinants of vaccination and willingness to pay for COVID-19 vaccines in Hungary, results of a cross-sectional online questionnaire

Authors: Zsuzsanna Beretzky and Valentin Brodszky

The effects of trade liberalization on inequality in nutrition intake: empirical evidence from Indian districts

Authors: Yali Zhang and Saiya Li

How do labour market conditions explain the development of mental health over the life-course? a conceptual integration of the ecological model with life-course epidemiology in an integrative review of results from the Northern Swedish Cohort

Authors: Anne Hammarström, Hugo Westerlund, Urban Janlert, Pekka Virtanen, Shirin Ziaei and Per-Olof Östergren

Most recent articles RSS

View all articles

Porn video shows, local brew, and transactional sex: HIV risk among youth in Kisumu, Kenya

Authors: Carolyne Njue, Helene ACM Voeten and Pieter Remes

Local government responses for COVID-19 management in the Philippines

Authors: Dylan Antonio S. Talabis, Ariel L. Babierra, Christian Alvin H. Buhat, Destiny S. Lutero, Kemuel M. Quindala III and Jomar F. Rabajante

School grade and sex differences in domain-specific sedentary behaviors among Japanese elementary school children: a cross-sectional study

Authors: Kaori Ishii, Ai Shibata, Minoru Adachi, Yoshiyuki Mano and Koichiro Oka

Oral and anal sex practices among high school youth in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Authors: Amsale Cherie and Yemane Berhane

Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models

Authors: Kristine Sørensen, Stephan Van den Broucke, James Fullam, Gerardine Doyle, Jürgen Pelikan, Zofia Slonska and Helmut Brand

Most accessed articles RSS

Aims and scope

Editorial board updates.

Join the Editorial Board

We are recruiting new, international Editorial Board Members.

Meet Biplab Kumar Datta

Meet our Editorial Board Members working on the Sustainable Development Goals.

BMC Public Health supports:

The UN Sustainable Development Goals

assisting policy-makers, governments and humanitarian organizations in making research-backed decisions to advance the international well-being agenda.

Equity in academic publishing

for authors based in low- and middle-income countries who might face challenges in publishing their work. Follow us for guidance on submitting your research to us.

BMC Public Health blogs

Highlights of the BMC series – April 2024

15 May 2024

Highlights of the BMC Series – March 2024

10 April 2024

Highlights of the BMC Series – December 2023

30 January 2024

Latest Tweets

Your browser needs to have JavaScript enabled to view this timeline

Important information

Editorial board

For authors

For editorial board members

For reviewers

- Manuscript editing services

Annual Journal Metrics

2022 Citation Impact 4.5 - 2-year Impact Factor 4.7 - 5-year Impact Factor 1.661 - SNIP (Source Normalized Impact per Paper) 1.307 - SJR (SCImago Journal Rank)

2023 Speed 32 days submission to first editorial decision for all manuscripts (Median) 173 days submission to accept (Median)

2023 Usage 24,332,405 downloads 24,308 Altmetric mentions

- More about our metrics

Peer-review Terminology

The following summary describes the peer review process for this journal:

Identity transparency: Single anonymized

Reviewer interacts with: Editor

Review information published: Review reports. Reviewer Identities reviewer opt in. Author/reviewer communication

More information is available here

- Follow us on Twitter

ISSN: 1471-2458

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

Public Health and Epidemiology

Empowering a community publishing articles in all areas of Public Health and Epidemiology, including disease surveillance, infectious disease outbreaks, vaccination, genetic epidemiology, epidemiological transition, sugar taxation, smoking cessation, exercise interventions, behaviour change and much more.

At PLOS, we put researchers and research first.

Our expert editorial boards collaborate with reviewers to provide accurate assessment that readers can trust. Authors have a choice of journals, publishing outputs, and tools to open their science to new audiences and get credit. We collaborate to make science, and the process of publishing science, fair, equitable, and accessible for the whole community.

Your New Open Science Journals

Public health implications of a changing climate.

Feature your research in this collection. We are looking for research that uses climate change to address effects on public health with a particular focus on the spread of infectious diseases. Explore this collection and find out how to submit your research.

Infectious Disease Epidemiology

Feature your research in this collection. We are looking for research that highlights the many interconnected facets of infectious disease epidemiology, including emerging zoonoses, viral genomics, infection dynamics, and more. Explore this collection and find out how to submit your research.

Looking for exciting work in your field?

Discover top cited Public Health & Epidemiology papers from recent years.

PLOS MEDICINE Accelerometer measured physical activity and the incidence of cardiovascular disease: Evidence from the UK Biobank cohort study Read the peer review...

PLOS MEDICINE Cardiovascular health metrics from mid- to late-life and risk of dementia: A population-based cohort study in Finland Read the peer review...

PLOS ONE Comparing the fit of N95, KN95, surgical, and cloth face masks and assessing the accuracy of fit checking Read the preprint...

PLOS ONE is launching a new influenza collection that will focus on every level of influenza prevention. Our panel of expert Guest Editors invite you to submit your research articles by April 9, 2021 to be considered for this collection.

Discover the latest opinion and perspective articles on climate change and infectious diseases in this PLOS Biology Collection. Here we explore one of the most pressing problems facing the world today: understanding how climate change will affect the distribution and dynamics of pathogens and their plant and animal hosts.

Reproducibility is important for the future of science.

PLOS is Open so that everyone can read, share, and reuse the research we publish. Underlying our commitment to Open Science is our data availability policy which ensures every piece of your research is accessible and replicable. We also go beyond that, empowering authors to preregister their research, and publish protocols , negative and null results, and more.

Author Interview: Luca Morgantini on Burnout among Healthcare Professionals in COVID-19

In 2020, PLOS articles were referenced an estimated 107,840 times by media outlets around the world. Read Public Health & Epidemiology articles that made the news.

- The impact of news exposure on collective attention in the United States during the 2016 Zika epidemic

- Residential green space and child intelligence and behavior across urban, suburban, and rural areas in Belgium: A longitudinal birth cohort study of twins

- Occurrence and transmission potential of asymptomatic and presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections: A living systematic review and meta-analysis

Ready to share your study with a wider audience? Help more people read, see, and cite your published research with our Author Media Toolkit

How can we increase adoption of open research practices?

Researchers are satisfied with their ability to share their own research data but may struggle with accessing other researchers’ data. Therefore, to increase data sharing in a findable and accessible way, PLOS will focus on better integrating existing data repositories and promoting their benefits rather than creating new solutions.

Imagining a transformed scientific publication landscape

Open Science is not a finish line, but rather a means to an end. An underlying goal behind the movement towards Open Science is to conduct and publish more reliable and thoroughly reported research.

Infectious disease modeling in a time of COVID-19

As the world grappled with the effects of COVID-19 this year, the importance of accurate infectious disease modeling has become apparent. We invited a few authors to give their perspectives on their research during this global pandemic.

- What do you think is the best way to ensure reproducibility for future generations of researchers?

What is public health?

Health care is vital to all of us some of the time, but public health is vital to all of us all of the time. —C. Everett Koop, former U.S. surgeon general

Health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. —World Health Organization

Public health is the science of protecting and improving the health of populations—from neighborhoods to cities to countries to world regions—through education, promotion of healthy lifestyles, research toward prevention of disease and injury, and detecting, preventing, and responding to infectious diseases. Public health experts analyze the effect on health of genetics, personal choice, and the environment to develop interventions and policies that protect the health of families and communities, such as vaccination programs and education on the dangers of tobacco and alcohol. As the American Public Health Association notes, “Public health saves money, improves our quality of life, helps children thrive, and reduces human suffering.”

Public health professionals try to prevent problems from happening or recurring through implementing educational programs, recommending policies, administering services, and conducting research—in contrast to clinical professionals like doctors and nurses, who focus primarily on treating individuals after they become sick or injured. Public health also works to limit health disparities. A large part of public health is promoting health care equity, quality, and accessibility. —CDC Foundation

Academic disciplines involved in public health

The field of public health is highly varied and encompasses many academic disciplines, including the following:

Behavioral science/Health education

Biostatistics

Environmental health

Epidemiology

Health policy

Health services administration/management

Humanitarian and human rights studies

Immunology, molecular biology, genetics, and other basic sciences

International health/global health

Maternal and child health

Public health laboratory practice (e.g., testing of biological and environmental samples)

Public health practice

Public health occupations

Some examples of the many occupations involved in public health include:

Scientists and researchers

Epidemiologists

Public health leaders and policymakers

Public health physicians

Public health nurses

Occupational health and safety professionals

Nutritionists

Social workers

Community planners

Health educators

First responders

Restaurant inspectors

Sanitarians (investigate health and safety within an environment, enforce health and safety regulations, and identify risk factors)

Activities of public health professionals

Some examples of the work undertaken by public health professionals include:

Studying environmental toxins and their health impacts

Monitoring the quality of the air we breathe and the water we drink

Developing plans and strategies to respond to emergencies and disasters

Exploring the causes of injuries and how best to prevent them

Testing biological and environmental samples

Researching risk factors for chronic disease and designing, implementing, and evaluating programs for reducing those risk factors

Implementing childhood and adult vaccination programs

Improving care for pregnant women, mothers, and newborns

Promoting healthy eating and physical activity

Ensuring access to a high-quality fruit and vegetable supply

Investigating infectious-disease outbreaks

Analyzing data for health trends

Undertaking screening programs for certain cancers

Analyzing and implementing public health policy

Principal tools of public health research

Population and numeric disciplines—especially epidemiology, biostatistics, and informatics

Biological sciences disciplines—focusing on infectious and chronic diseases as well as nutritional and environmental links to ill health. Largely laboratory based, and emphasizing the biological, chemical, and genetic basis of health and disease.

Social and policy disciplines—including health policy and management, global health systems, health economics, and the social and behavioral determinants of health and disease

Distinctions between public health and medicine

Because of their shared concern with human health, people often are confused by the difference between public health and medicine. In fact, people’s health is shaped much more by their lifestyle, social networks, environment, and genes than by medical care. Below are some specific distinctions between public health and medicine.

Public health

Primary focus on populations

Emphasis on disease prevention and health promotion for entire communities

Predominant emphasis on promoting healthy behaviors and environments

Specializations organized, for example, by analytical method (epidemiology, toxicology); setting and population (occupational health, global health); substantive health problem (environmental health, nutrition)

Biological sciences central, with a prime focus on major threats to the health of populations, such as epidemics and noncommunicable diseases; research moves between laboratory and field

Social and public policy disciplines an integral part of public health education

Primary focus on individuals

Emphasis on disease diagnosis, treatment, and care of the individual patient

Predominant emphasis on medical care

Specializations organized, for example, by organ system (cardiology, neurology); patient group (obstetrics, pediatrics); etiology and pathophysiology (infectious disease, oncology); technical skill (radiology, surgery)

Biological sciences central, stimulated by needs of patients ; research moves between laboratory and bedside

Social sciences generally an elective part of medical education

Leading causes of death in the United States

Medical view (focuses on the diseases that actually cause deaths).

Heart disease

Chronic lower respiratory diseases

Stroke (cerebrovascular diseases)

Source: Deaths and Mortality, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Much of this health burden could be prevented or postponed through improved nutrition, increased physical activity, improved vaccination rates, avoidance of tobacco use, adoption of measures to increase motor-vehicle safety, early detection and treatment of risk factors, and health-care quality improvement. — CDC National Health Report: Leading Causes of Morbidity and Mortality and Associated Behavioral Risk and Protective Factors—United States, 2005–2013

Public health view (focuses on the factors that lead to deadly diseases)

Tobacco use

Physical inactivity

Infectious disease

Social determinants of health

“Social determinants of health”—a term often used in the public health field—refers to the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO). These social determinants may describe social inequities that are reflected in the poor health of certain populations, often with devastating consequences. WHO, as noted in its report Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health, believes that reducing health inequities is an ethical imperative. “Social injustice,” the report notes, “is killing people on a grand scale.”

Examples of social determinants include:

Availability of resources to meet daily needs (e.g., safe housing and local food markets)

Access to educational, economic, and job opportunities

Access to health care services

Quality of education and job training

Availability of community-based resources in support of community living and opportunities for recreational and leisure-time activities

Transportation options

Public safety

Social support

Social norms and attitudes (e.g., discrimination, racism, and distrust of government)

Exposure to crime, violence, and social disorder (e.g., presence of trash and lack of cooperation in a community)

Socioeconomic conditions (e.g., concentrated poverty and the stressful conditions that accompany it)

Residential segregation

Language/Literacy

Access to mass media and emerging technologies (e.g., cell phones, the Internet, and social media)

Source: Healthy People 2020

People’s health is determined in part by access to social and economic opportunities; the resources and supports available in their homes, neighborhoods, and communities; the quality of their schooling; the safety of their workplaces; the cleanliness of their water, food, and air; and the nature of their social interactions and relationships. Social determinants of health involve economic stability, education, social and community context, health, health care, neighborhood, and the built environment. Each of these five determinant areas reflects a number of key issues that make up the underlying factors in the arena of social determinants of health.

Economic stability

Food insecurity

Housing instability

Early childhood education and development

Enrollment in higher education

High school graduation

Language and literacy

Social and community context

Civic participation

Discrimination

Incarceration

Social cohesion

Health and health care

Access to health care

Access to primary care

Health literacy

Neighborhood and built environment

Access to foods that support healthy eating patterns

Crime and violence

Environmental conditions

“The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition.” —Constitution of the World Health Organization, inscribed in several languages on the FXB Building of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

Major global public health challenges

Ending disparities in health between rich and poor and across racial and gender lines

Reducing infant mortality, maternal death rates, and reproductive health problems

Developing solutions and treatments for infectious diseases (e.g., AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria)

Tackling malnutrition

Preventing the spread of multi-drug-resistant (MDR) diseases, such as MDR tuberculosis

Confronting emerging threats to health from chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and obesity that are related to lifestyle (e.g., diet, exercise, and tobacco use)

Addressing mental illnesses and social factors in health

Understanding climate change and other environmental health threats

Studying the impacts of war, violence, and terrorism on health

Advancing practices, protocols, and strategies to achieve diverse goals, such as reducing surgical errors, changing social norms around drunk driving

Developing health and communications systems to improve health-related policy and decision-making and increase the speed and effectiveness of responses to emergencies such as disease pandemics, natural disasters, or terrorist attacks

Ten great public health achievements in the United States, 1900–1999

1. vaccination.

Programs of population-wide vaccinations resulted in the eradication of smallpox; elimination of polio in the Americas; and control of measles, rubella, tetanus, diphtheria, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and other infectious diseases in the United States and other parts of the world.

2. Motor-vehicle safety

Improvements in motor-vehicle safety have contributed to large reductions in motor-vehicle-related deaths. These improvements include engineering efforts to make both vehicles and highways safer and successful efforts to change personal behavior (e.g., increased use of safety belts, child safety seats, motorcycle helmets, and decreased drinking and driving).

3. Safer workplaces

Work-related health problems, such as coal workers’ pneumoconiosis (black lung), and silicosis—common at the beginning of the century— have been significantly reduced. Severe injuries and deaths related to mining, manufacturing, construction, and transportation also have decreased; since 1980, safer workplaces have resulted in a reduction of approximately 40% in the rate of fatal occupational injuries.

4. Control of infectious diseases

Control of infectious diseases has resulted from clean water and better sanitation. Infections such as typhoid and cholera, major causes of illness and death early in the 20th century, have been reduced dramatically by improved sanitation. In addition, the discovery of antimicrobial therapy has been critical to successful public health efforts to control infections such as tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).

5. Decline in deaths from coronary heart disease and stroke

Decline in deaths from coronary heart disease and stroke have resulted from risk-factor modification, such as smoking cessation and blood pressure control coupled with improved access to early detection and better treatment. Since 1972, death rates for coronary heart disease have decreased 51 percent.

6. Safer and healthier foods

Since 1900, safer and healthier foods have resulted from decreases in microbial contamination and increases in nutritional content. Identifying essential micronutrients and establishing food-fortification programs have almost eliminated major nutritional deficiency diseases such as rickets, goiter, and pellagra in the United States. [Healthy Eating Plate sidebar]

7. Healthier mothers and babies

Healthier mothers and babies are a result of better hygiene and nutrition, availability of antibiotics, greater access to health care, and technological advances in maternal and neonatal medicine. Since 1900, infant mortality has decreased 90 percent, and maternal mortality has decreased 99 percent.

8. Family planning

Access to family planning and contraceptive services has altered social and economic roles of women. Family planning has provided health benefits such as smaller family size and longer intervals between the birth of children; increased opportunities for preconceptional counseling and screening; fewer infant, child, and maternal deaths; and the use of barrier contraceptives to prevent pregnancy and transmission of human immunodeficiency virus and other STDs.

9. Fluoridation of drinking water

Fluoridation of drinking water began in 1945 and in 1999 reaches an estimated 144 million persons in the United States. Fluoridation safely and inexpensively benefits both children and adults by effectively preventing tooth decay, regardless of socioeconomic status or access to care. Fluoridation has played an important role in the reductions in tooth decay (40 percent to 70 percent in children) and of tooth loss in adults (40 percent to 60 percent).

10. Recognition of tobacco use as a health hazard

Recognition of tobacco use as a health hazard in 1964 has resulted in changes in the promotion of cessation of use, and reduction of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Since the initial Surgeon General’s report on the health risks of smoking, the prevalence of smoking among adults has decreased, and millions of smoking-related deaths have been prevented.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

Ten great public health achievements in the United States, 2001–2010

During the 20th century, life expectancy at birth among U.S. residents increased by 62%, from 47.3 years in 1900 to 76.8 in 2000, and unprecedented improvements in population health status were observed at every stage of life. In 1999, the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report published a series of reports highlighting 10 public health achievements that contributed to those improvements. This report assesses advances in public health during the first 10 years of the 21st century. Public health scientists at the CDC were asked to nominate noteworthy public health achievements that occurred in the United States during 2001–2010. From those nominations, 10 achievements, not ranked in any order, have been summarized in this report. — Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

1. Vaccine-preventable diseases

The decade saw substantial declines in cases, hospitalizations, deaths, and health-care costs associated with vaccine-preventable diseases. New vaccines (i.e., rotavirus, quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate, herpes zoster, pneumococcal conjugate, and human papillomavirus vaccines, as well as tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine for adults and adolescents) were introduced, bringing to 17 the number of diseases targeted by U.S. immunization policy. A recent economic analysis indicated that vaccination of each U.S. birth cohort with the current childhood immunization schedule prevents approximately 42,000 deaths and 20 million cases of disease, with net savings of nearly $14 billion in direct costs and $69 billion in total societal costs.

The impact of two vaccines has been particularly striking. Following the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, an estimated 211,000 serious pneumococcal infections and 13,000 deaths were prevented during 2000–2008. Routine rotavirus vaccination, implemented in 2006, now prevents an estimated 40,000–60,000 rotavirus hospitalizations each year. Advances also were made in the use of older vaccines, with reported cases of hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and varicella at record lows by the end of the decade. Age-specific mortality (i.e., deaths per million population) from varicella for persons age <20 years, declined by 97% from 0.65 in the prevaccine period (1990–1994) to 0.02 during 2005–2007. Average age-adjusted mortality (deaths per million population) from hepatitis A also declined significantly, from 0.38 in the prevaccine period (1990–1995) to 0.26 during 2000–2004.

2. Prevention and control of infectious diseases

Improvements in state and local public health infrastructure along with innovative and targeted prevention efforts yielded significant progress in controlling infectious diseases. Examples include a 30% reduction from 2001 to 2010 in reported U.S. tuberculosis cases and a 58% decline from 2001 to 2009 in central line–associated blood stream infections. Major advances in laboratory techniques and technology and investments in disease surveillance have improved the capacity to identify contaminated foods rapidly and accurately and prevent further spread. Multiple efforts to extend HIV testing, including recommendations for expanded screening of persons aged 13–64 years, increased the number of persons diagnosed with HIV/AIDS and reduced the proportion with late diagnoses, enabling earlier access to life-saving treatment and care and giving infectious persons the information necessary to protect their partners. In 2002, information from CDC predictive models and reports of suspected West Nile virus transmission through blood transfusion spurred a national investigation, leading to the rapid development and implementation of new blood donor screening. To date, such screening has interdicted 3,000 potentially infected U.S. donations, removing them from the blood supply. Finally, in 2004, after more than 60 years of effort, canine rabies was eliminated in the United States, providing a model for controlling emerging zoonoses.

3. Tobacco control

Since publication of the first Surgeon General’s Report on tobacco in 1964, implementation of evidence-based policies and interventions by federal, state, and local public health authorities has reduced tobacco use significantly. By 2009, 20.6% of adults and 19.5% of youths were current smokers, compared with 23.5% of adults and 34.8% of youths 10 years earlier. However, progress in reducing smoking rates among youths and adults appears to have stalled in recent years. After a substantial decline from 1997 (36.4%) to 2003 (21.9%), smoking rates among high school students remained relatively unchanged from 2003 (21.9%) to 2009 (19.5%). Similarly, adult smoking prevalence declined steadily from 1965 (42.4%) through the 1980s, but the rate of decline began to slow in the 1990s, and the prevalence remained relatively unchanged from 2004 (20.9%) to 2009 (20.6%). Despite the progress that has been made, smoking still results in an economic burden, including medical costs and lost productivity, of approximately $193 billion per year.

Although no state had a comprehensive smoke-free law (i.e., prohibit smoking in worksites, restaurants, and bars) in 2000, that number increased to 25 states and the District of Columbia (DC) by 2010, with 16 states enacting comprehensive smoke-free laws following the release of the 2006 Surgeon General’s Report. After 99 individual state cigarette excise tax increases, at an average increase of 55.5 cents per pack, the average state excise tax increased from 41.96 cents per pack in 2000 to $1.44 per pack in 2010. In 2009, the largest federal cigarette excise tax increase went into effect, bringing the combined federal and average state excise tax for cigarettes to $2.21 per pack, an increase from $0.76 in 2000. In 2009, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) gained the authority to regulate tobacco products. By 2010, FDA had banned flavored cigarettes, established restrictions on youth access, and proposed larger, more effective graphic warning labels that are expected to lead to a significant increase in quit attempts.

4. Maternal and infant health

The past decade has seen significant reductions in the number of infants born with neural tube defects (NTDs) and expansion of screening of newborns for metabolic and other heritable disorders. Mandatory folic acid fortification of cereal grain products labeled as enriched in the United States beginning in 1998 contributed to a 36% reduction in NTDs from 1996 to 2006 and prevented an estimated 10,000 NTD-affected pregnancies in the past decade, resulting in a savings of $4.7 billion in direct costs.

Improvements in technology and endorsement of a uniform newborn-screening panel of diseases have led to earlier life-saving treatment and intervention for at least 3,400 additional newborns each year with selected genetic and endocrine disorders. In 2003, all but four states were screening for only six of these disorders. By April 2011, all states reported screening for at least 26 disorders on an expanded and standardized uniform panel. Newborn screening for hearing loss increased from 46.5% in 1999 to 96.9% in 2008. The percentage of infants not passing their hearing screening who were then diagnosed by an audiologist before age 3 months as either normal or having permanent hearing loss increased from 51.8% in 1999 to 68.1 in 2008.

5. Motor-vehicle safety

Motor vehicle crashes are among the top 10 causes of death for U.S. residents of all ages and the leading cause of death for persons aged 5–34 years. In terms of years of potential life lost before age 65, motor vehicle crashes ranked third in 2007, behind only cancer and heart disease, and account for an estimated $99 billion in medical and lost work costs annually. Crash-related deaths and injuries largely are preventable. From 2000 to 2009, while the number of vehicle miles traveled on the nation’s roads increased by 8.5%, the death rate related to motor vehicle travel declined from 14.9 per 100,000 population to 11.0, and the injury rate declined from 1,130 to 722; among children, the number of pedestrian deaths declined by 49%, from 475 to 244, and the number of bicyclist deaths declined by 58%, from 178 to 74.

These successes largely resulted from safer vehicles, safer roadways, and safer road use. Behavior was improved by protective policies, including effective seat belt and child safety seat legislation; 49 states and the DC have enacted seat belt laws for adults, and all 50 states and DC have enacted legislation that protects children riding in vehicles. Graduated drivers licensing policies for teen drivers have helped reduce the number of teen crash deaths.

6. Cardiovascular-disease prevention

Heart disease and stroke have been the first and third leading causes of death in the United States since 1921 and 1938, respectively. Preliminary data from 2009 indicate that stroke is now the fourth leading cause of death in the United States. During the past decade, the age-adjusted coronary heart disease and stroke death rates declined from 195 to 126 per 100,000 population and from 61.6 to 42.2 per 100,000 population, respectively, continuing a trend that started in the 1900s for stroke and in the 1960s for coronary heart disease. Factors contributing to these reductions include declines in the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors such as uncontrolled hypertension, elevated cholesterol, and smoking, and improvements in treatments, medications, and quality of care.

7. Occupational safety

Significant progress was made in improving working conditions and reducing the risk for workplace-associated injuries. For example, patient lifting has been a substantial cause of low back injuries among the 1.8 million U.S. health-care workers in nursing care and residential facilities. In the late 1990s, an evaluation of a best practices patient-handling program that included the use of mechanical patient-lifting equipment demonstrated reductions of 66% in the rates of workers’ compensation injury claims and lost workdays and documented that the investment in lifting equipment can be recovered in less than 3 years. Following widespread dissemination and adoption of these best practices by the nursing home industry, Bureau of Labor Statistics data showed a 35% decline in low back injuries in residential and nursing care employees between 2003 and 2009.

The annual cost of farm-associated injuries among youth has been estimated at $1 billion annually. A comprehensive childhood agricultural injury prevention initiative was established to address this problem. Among its interventions was the development by the National Children’s Center for Rural Agricultural Health and Safety of guidelines for parents to match chores with their child’s development and physical capabilities. Follow-up data have demonstrated a 56% decline in youth farm injury rates from 1998 to 2009 (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, unpublished data, 2011).

In the mid-1990s, crab fishing in the Bering Sea was associated with a rate of 770 deaths per 100,000 full-time fishers. Most fatalities occurred when vessels overturned because of heavy loads. In 1999, the U.S. Coast Guard implemented Dockside Stability and Safety Checks to correct stability hazards. Since then, one vessel has been lost and the fatality rate among crab fishermen has declined to 260 deaths per 100,000 full-time fishers.

8. Cancer prevention

Evidence-based screening recommendations have been established to reduce mortality from colorectal cancer and female breast and cervical cancer. Several interventions inspired by these recommendations have improved cancer screening rates. Through the collaborative efforts of federal, state, and local health agencies, professional clinician societies, not-for-profit organizations, and patient advocates, standards were developed that have significantly improved cancer screening test quality and use. The National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program has reduced disparities by providing breast and cervical cancer screening services for uninsured women. The program’s success has resulted from similar collaborative relationships. From 1998 to 2007, colorectal cancer death rates decreased from 25.6 per 100,000 population to 20.0 (2.8% per year) for men and from 18.0 per 100,000 to 14.2 (2.7% per year) for women. During this same period, smaller declines were noted for breast and cervical cancer death rates (2.2% per year and 2.4%, respectively).

9. Childhood lead-poisoning prevention

In 2000, childhood lead poisoning remained a major environmental public health problem in the United States, affecting children from all geographic areas and social and economic levels. Black children and those living in poverty and in old, poorly maintained housing were disproportionately affected. In 1990, five states had comprehensive lead poisoning prevention laws; by 2010, 23 states had such laws. Enforcement of these statutes as well as federal laws that reduce hazards in the housing with the greatest risks has significantly reduced the prevalence of lead poisoning. Findings of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys from 1976–1980 to 2003–2008 reveal a steep decline, from 88.2% to 0.9%, in the percentage of children aged 1–5 years with blood lead levels ≥10 µg/dL. The risks for elevated blood lead levels based on socioeconomic status and race also were reduced significantly. The economic benefit of lowering lead levels among children by preventing lead exposure is estimated at $213 billion per year.

10. Public health preparedness and response

After the international and domestic terrorist actions of 2001 highlighted gaps in the nation’s public health preparedness, tremendous improvements have been made. In the first half of the decade, efforts were focused primarily on expanding the capacity of the public health system to respond (e.g., purchasing supplies and equipment). In the second half of the decade, the focus shifted to improving the laboratory, epidemiology, surveillance, and response capabilities of the public health system. For example, from 2006 to 2010, the percentage of Laboratory Response Network labs that passed proficiency testing for bioterrorism threat agents increased from 87% to 95%. The percentage of state public health laboratories correctly subtyping Escherichia coli O157:H7 and submitting the results into a national reporting system increased from 46% to 69%, and the percentage of state public health agencies prepared to use Strategic National Stockpile material increased from 70% to 98%. During the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, these improvements in the ability to develop and implement a coordinated public health response in an emergency facilitated the rapid detection and characterization of the outbreak, deployment of laboratory tests, distribution of personal protective equipment from the Strategic National Stockpile, development of a candidate vaccine virus, and widespread administration of the resulting vaccine. These public health interventions prevented an estimated 5–10 million cases, 30,000 hospitalizations, and 1,500 deaths (CDC, unpublished data, 2011).

Existing systems also have been adapted to respond to public health threats. During the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, the Vaccines for Children program was adapted to enable provider ordering and distribution of the pandemic vaccine. Similarly, President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief clinics were used to rapidly deliver treatment following the 2010 cholera outbreak in Haiti.

News from the School

From public servant to public health student

Exploring the intersection of health, mindfulness, and climate change

Conference aims to help experts foster health equity

Building solidarity to face global injustice

- Public Health Research

- Open Access

- First Online: 13 April 2016

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Drue H. Barrett PhD 8 ,

- Leonard W. Ortmann PhD 8 ,

- Natalie Brown MPH 9 ,

- Barbara R. DeCausey MPH, MBA 10 ,

- Carla Saenz PhD 11 &

- Angus Dawson PhD 12

Part of the book series: Public Health Ethics Analysis ((PHES,volume 3))

188k Accesses

5 Citations

3 Altmetric

Having a scientific basis for the practice of public health is critical. Research leads to insight and innovations that solve health problems and is therefore central to public health worldwide. For example, in the United States research is one of the ten essential public health services (Public Health Functions Steering Committee 1994). The s of the Ethical Practice of Public , developed by the Public Health Leadership Society (2002), emphasizes the value of having a scientific basis for action. Principle five specifically calls on public health to seek the information needed to carry out effective policies and programs that protect and promote health.

The opinions, findings, and conclusions of the authors do not necessarily reflect the official position, views, or policies of the editors, the editors’ host institutions, or the authors’ host institutions.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Research Methods

Evidence-Based Decision-Making 8: Health Policy, a Primer for Researchers

How do we define the policy impact of public health research a systematic review.

- Ethical Challenge

- Public Health Agency

- Public Health Practice

- Informal Payment

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

Having a scientific basis for the practice of public health is critical. Research leads to insight and innovations that solve health problems and is therefore central to public health worldwide. For example, in the United States research is one of the ten essential public health services (Public Health Functions Steering Committee 1994). The Principle s of the Ethical Practice of Public Health , developed by the Public Health Leadership Society (2002), emphasizes the value of having a scientific basis for action. Principle five specifically calls on public health to seek the information needed to carry out effective policies and programs that protect and promote health.

This chapter pres ents ethical issues that can arise when conducting public health research. Although the literature about research ethics is complex and rich, it has at least two important limitations when applied to public health research. The first is that much of research ethics has focused on clinical or biomedical research in which the primary interaction is between individuals (i.e., patient-physician or research participant-researcher). Since bioethics tends to focus on the individual, the field of research ethics often neglects broader issues pertaining to communities and population s, including ethical issues raised by some public health research methods (e.g., the use of cluster randomized trials to measure population, not just individual, effects). However, if our discussion of public health research ethics begins by examining public health activities, it becomes apparent that the process of gaining consent involves more than individuals. We must consider that communities bear risks and reap benefits; that not only individuals but also populations may be vulnerable; and that the social, political , and economic context in which research takes place poses ethical challenges. Public health research, with its focus on intervention at community and population levels, has brought these broader ethical considerations to researchers’ attention, demonstrating how ethics guidance based on biomedical research may limit, if not distort, the ethical perspective required to protect human subjects.