- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?

Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

Verywell / Colleen Tighe

- Pros and Cons

What Types of Case Studies Are Out There?

Where do you find data for a case study, how do i write a psychology case study.

A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work.

The point of a case study is to learn as much as possible about an individual or group so that the information can be generalized to many others. Unfortunately, case studies tend to be highly subjective, and it is sometimes difficult to generalize results to a larger population.

While case studies focus on a single individual or group, they follow a format similar to other types of psychology writing. If you are writing a case study, we got you—here are some rules of APA format to reference.

At a Glance

A case study, or an in-depth study of a person, group, or event, can be a useful research tool when used wisely. In many cases, case studies are best used in situations where it would be difficult or impossible for you to conduct an experiment. They are helpful for looking at unique situations and allow researchers to gather a lot of˜ information about a specific individual or group of people. However, it's important to be cautious of any bias we draw from them as they are highly subjective.

What Are the Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies?

A case study can have its strengths and weaknesses. Researchers must consider these pros and cons before deciding if this type of study is appropriate for their needs.

One of the greatest advantages of a case study is that it allows researchers to investigate things that are often difficult or impossible to replicate in a lab. Some other benefits of a case study:

- Allows researchers to capture information on the 'how,' 'what,' and 'why,' of something that's implemented

- Gives researchers the chance to collect information on why one strategy might be chosen over another

- Permits researchers to develop hypotheses that can be explored in experimental research

On the other hand, a case study can have some drawbacks:

- It cannot necessarily be generalized to the larger population

- Cannot demonstrate cause and effect

- It may not be scientifically rigorous

- It can lead to bias

Researchers may choose to perform a case study if they want to explore a unique or recently discovered phenomenon. Through their insights, researchers develop additional ideas and study questions that might be explored in future studies.

It's important to remember that the insights from case studies cannot be used to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables. However, case studies may be used to develop hypotheses that can then be addressed in experimental research.

Case Study Examples

There have been a number of notable case studies in the history of psychology. Much of Freud's work and theories were developed through individual case studies. Some great examples of case studies in psychology include:

- Anna O : Anna O. was a pseudonym of a woman named Bertha Pappenheim, a patient of a physician named Josef Breuer. While she was never a patient of Freud's, Freud and Breuer discussed her case extensively. The woman was experiencing symptoms of a condition that was then known as hysteria and found that talking about her problems helped relieve her symptoms. Her case played an important part in the development of talk therapy as an approach to mental health treatment.

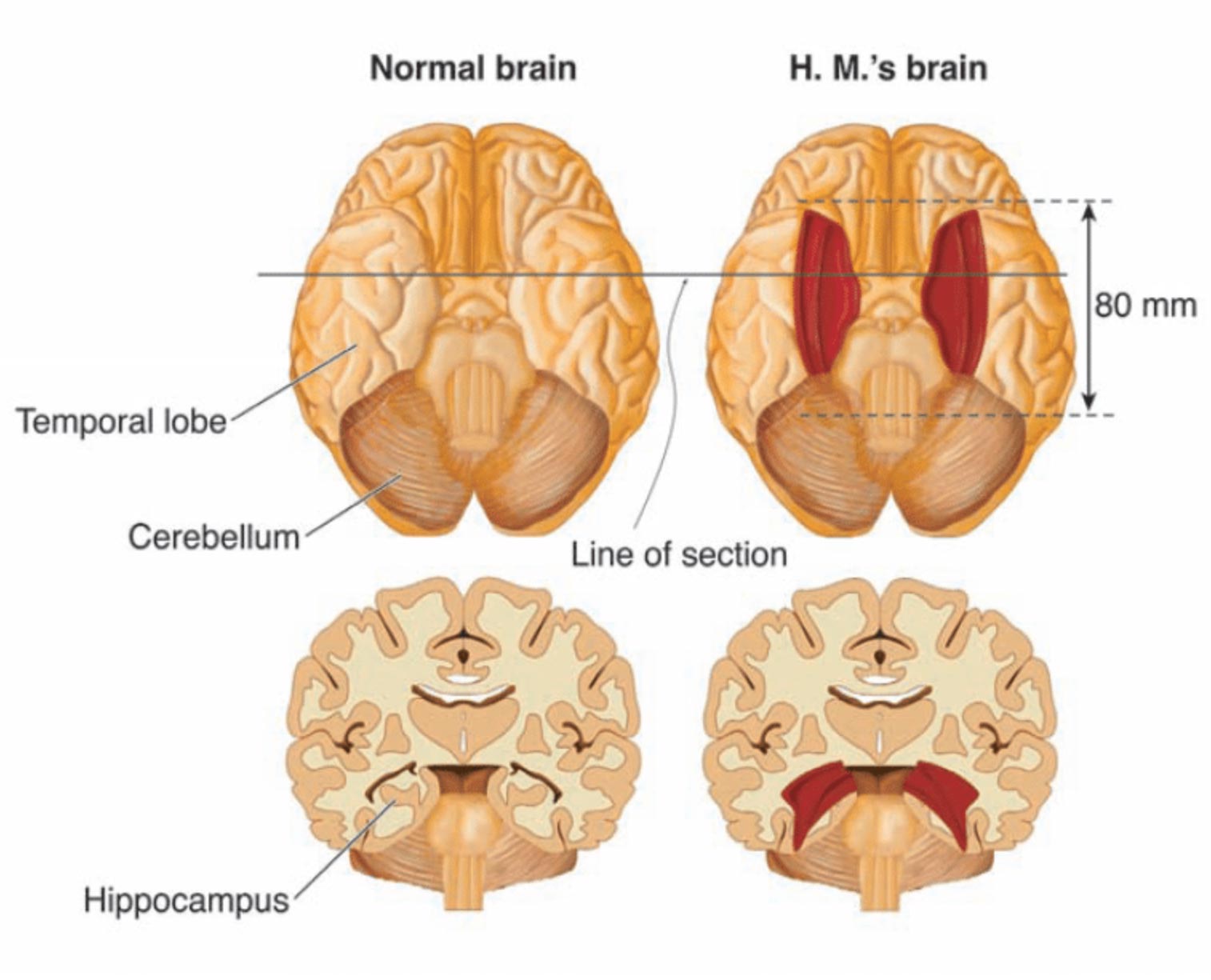

- Phineas Gage : Phineas Gage was a railroad employee who experienced a terrible accident in which an explosion sent a metal rod through his skull, damaging important portions of his brain. Gage recovered from his accident but was left with serious changes in both personality and behavior.

- Genie : Genie was a young girl subjected to horrific abuse and isolation. The case study of Genie allowed researchers to study whether language learning was possible, even after missing critical periods for language development. Her case also served as an example of how scientific research may interfere with treatment and lead to further abuse of vulnerable individuals.

Such cases demonstrate how case research can be used to study things that researchers could not replicate in experimental settings. In Genie's case, her horrific abuse denied her the opportunity to learn a language at critical points in her development.

This is clearly not something researchers could ethically replicate, but conducting a case study on Genie allowed researchers to study phenomena that are otherwise impossible to reproduce.

There are a few different types of case studies that psychologists and other researchers might use:

- Collective case studies : These involve studying a group of individuals. Researchers might study a group of people in a certain setting or look at an entire community. For example, psychologists might explore how access to resources in a community has affected the collective mental well-being of those who live there.

- Descriptive case studies : These involve starting with a descriptive theory. The subjects are then observed, and the information gathered is compared to the pre-existing theory.

- Explanatory case studies : These are often used to do causal investigations. In other words, researchers are interested in looking at factors that may have caused certain things to occur.

- Exploratory case studies : These are sometimes used as a prelude to further, more in-depth research. This allows researchers to gather more information before developing their research questions and hypotheses .

- Instrumental case studies : These occur when the individual or group allows researchers to understand more than what is initially obvious to observers.

- Intrinsic case studies : This type of case study is when the researcher has a personal interest in the case. Jean Piaget's observations of his own children are good examples of how an intrinsic case study can contribute to the development of a psychological theory.

The three main case study types often used are intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Intrinsic case studies are useful for learning about unique cases. Instrumental case studies help look at an individual to learn more about a broader issue. A collective case study can be useful for looking at several cases simultaneously.

The type of case study that psychology researchers use depends on the unique characteristics of the situation and the case itself.

There are a number of different sources and methods that researchers can use to gather information about an individual or group. Six major sources that have been identified by researchers are:

- Archival records : Census records, survey records, and name lists are examples of archival records.

- Direct observation : This strategy involves observing the subject, often in a natural setting . While an individual observer is sometimes used, it is more common to utilize a group of observers.

- Documents : Letters, newspaper articles, administrative records, etc., are the types of documents often used as sources.

- Interviews : Interviews are one of the most important methods for gathering information in case studies. An interview can involve structured survey questions or more open-ended questions.

- Participant observation : When the researcher serves as a participant in events and observes the actions and outcomes, it is called participant observation.

- Physical artifacts : Tools, objects, instruments, and other artifacts are often observed during a direct observation of the subject.

If you have been directed to write a case study for a psychology course, be sure to check with your instructor for any specific guidelines you need to follow. If you are writing your case study for a professional publication, check with the publisher for their specific guidelines for submitting a case study.

Here is a general outline of what should be included in a case study.

Section 1: A Case History

This section will have the following structure and content:

Background information : The first section of your paper will present your client's background. Include factors such as age, gender, work, health status, family mental health history, family and social relationships, drug and alcohol history, life difficulties, goals, and coping skills and weaknesses.

Description of the presenting problem : In the next section of your case study, you will describe the problem or symptoms that the client presented with.

Describe any physical, emotional, or sensory symptoms reported by the client. Thoughts, feelings, and perceptions related to the symptoms should also be noted. Any screening or diagnostic assessments that are used should also be described in detail and all scores reported.

Your diagnosis : Provide your diagnosis and give the appropriate Diagnostic and Statistical Manual code. Explain how you reached your diagnosis, how the client's symptoms fit the diagnostic criteria for the disorder(s), or any possible difficulties in reaching a diagnosis.

Section 2: Treatment Plan

This portion of the paper will address the chosen treatment for the condition. This might also include the theoretical basis for the chosen treatment or any other evidence that might exist to support why this approach was chosen.

- Cognitive behavioral approach : Explain how a cognitive behavioral therapist would approach treatment. Offer background information on cognitive behavioral therapy and describe the treatment sessions, client response, and outcome of this type of treatment. Make note of any difficulties or successes encountered by your client during treatment.

- Humanistic approach : Describe a humanistic approach that could be used to treat your client, such as client-centered therapy . Provide information on the type of treatment you chose, the client's reaction to the treatment, and the end result of this approach. Explain why the treatment was successful or unsuccessful.

- Psychoanalytic approach : Describe how a psychoanalytic therapist would view the client's problem. Provide some background on the psychoanalytic approach and cite relevant references. Explain how psychoanalytic therapy would be used to treat the client, how the client would respond to therapy, and the effectiveness of this treatment approach.

- Pharmacological approach : If treatment primarily involves the use of medications, explain which medications were used and why. Provide background on the effectiveness of these medications and how monotherapy may compare with an approach that combines medications with therapy or other treatments.

This section of a case study should also include information about the treatment goals, process, and outcomes.

When you are writing a case study, you should also include a section where you discuss the case study itself, including the strengths and limitiations of the study. You should note how the findings of your case study might support previous research.

In your discussion section, you should also describe some of the implications of your case study. What ideas or findings might require further exploration? How might researchers go about exploring some of these questions in additional studies?

Need More Tips?

Here are a few additional pointers to keep in mind when formatting your case study:

- Never refer to the subject of your case study as "the client." Instead, use their name or a pseudonym.

- Read examples of case studies to gain an idea about the style and format.

- Remember to use APA format when citing references .

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011;11:100.

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011 Jun 27;11:100. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Gagnon, Yves-Chantal. The Case Study as Research Method: A Practical Handbook . Canada, Chicago Review Press Incorporated DBA Independent Pub Group, 2010.

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . United States, SAGE Publications, 2017.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Reviews / Why join our community?

- For companies

- Frequently asked questions

How to write the conclusion of your case study

You worked on an amazing UX project. You documented every detail and deliverable and when the time came, you began to write a UX case study about it. In the case study, you highlighted how you worked through a Design Thinking process to get to the end result; so, can you stop there and now move on to the next thing? Well, no! There’s just one more bit left to finish up and make the perfect case study. So, get ready; we will now explore how you can write the perfect conclusion to wrap it all up and leave a lasting great impression.

Every start has an end – we’re not just repeating the famous quote here, because for case studies, a proper end is your last and final chance to leave a lasting great (at the very least, good) impression with whoever is reading your work (typically, recruiters!). Many junior UX designers often forget about the conclusion part of the case study, but this is a costly mistake to make. A well-written case study must end with an appropriate final section, in which you should summarize the key takeaways that you want others to remember about you and your work. Let’s see why.

Last impressions are just as important as first ones

We’ll go to some length here to convince you about the importance of last impressions, especially as we can understand the reason behind not wanting to pay very much attention to the end of your case study, after all the hard work you put into writing the process section. You are tired, and anyone who’s read your work should already have a good idea about your skills, anyway. Surely—you could be forgiven for thinking, at least—all that awesome material you put in the start and middle sections must have built up the momentum to take your work into orbit and make the recruiter’s last impression of you a lasting—and very good—one, and all you need to do now is take your leave. However, psychologist Saul McLeod (2008) explains how early work by experimental psychology pioneers Atkinson & Shriffin (1968) demonstrated that when humans are presented with information, they tend to remember the first and last elements and are more likely to forget the middle ones.

This is known as the “ serial position effect ” (more technically, the tendency to remember the first elements is known as the “ primacy effect ”, while the tendency to remember the last elements is known as the “ recency effect ”). Further work in human experiences discovered that the last few things we see or hear at the end of an experience can generate the most powerful memories that come back to us when we come across a situation or when we think about it. For example, let’s say you stayed in a hotel room that left a bit to be desired. Maybe the room was a little cramped, or the towels were not so soft. But if the receptionist, as you leave, shakes your hand warmly, smiles and thanks you sincerely for your custom, and goes out of his way to help you with your luggage, or to get you a taxi, you will remember that person’s kind demeanor more than you will remember the fact that the room facilities could be improved.

A good ending to your case study can help people forget some of the not-so-good points about your case study middle. For example, if you missed out a few crucial details but can demonstrate some truly interesting takeaways, they can always just ask you about these in an interview. Inversely, a bad ending leaves the recruiter with some doubt that will linger. Did this person learn nothing interesting from all this work? Did their work have no impact at all? Did they even write the case study themselves? A bad last impression can certainly undo much of the hard work you’ve put into writing the complicated middle part of your case study.

What to put in your case study conclusions

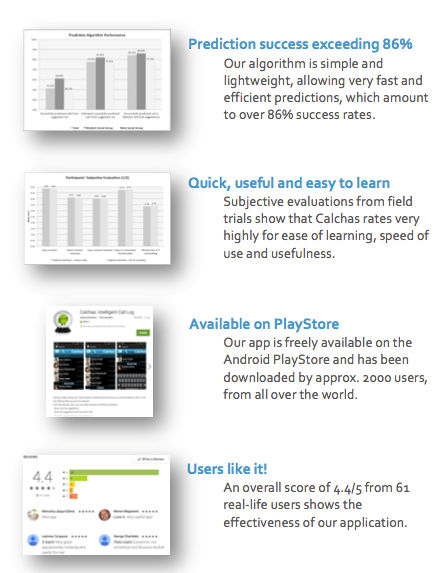

A case study ending is your opportunity to bring some closure to the story that you are writing. So, you can use it to mention the status of the project (e.g., is it ongoing or has it ended?) and then to demonstrate the impact that your work has had. By presenting some quantifiable results (e.g., data from end evaluations, analytics, key performance indicators ), you can demonstrate this impact. You can also discuss what you learned from this project, making you wiser than the next applicant – for example, something about a special category of users that the company might be interested in developing products for, or something that is cutting-edge and that advances the frontiers of science or practice.

As you can see, there are a few good ways in which you can end your case study. Next, we will outline four options that can be part of your ending: lessons learned, the impact of the project, reflections, and acknowledgements.

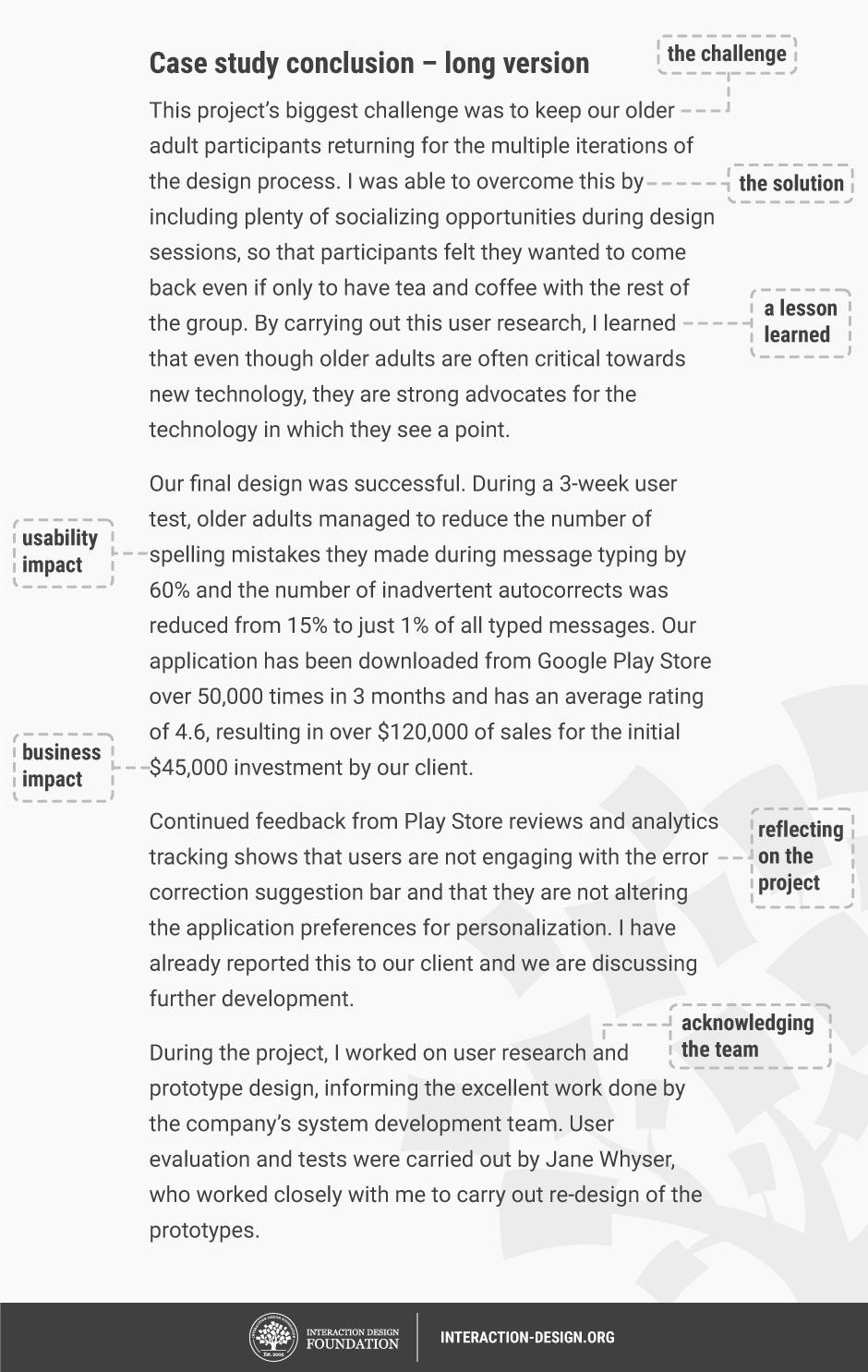

Lessons learned

A recruiter wants to see how you improve yourself by learning from the projects you work on. You can discuss interesting insights that you learned from user research or the evaluation of your designs – for example, surprising behaviors that you found out about the technology use in a group of users who are not typically considered to be big proponents of technology (e.g., older adults), or, perhaps, the reasons a particular design pattern didn’t work as well as expected under the context of your project.

Another thing you can discuss is your opinion on what the most difficult challenge of the project was, and comment on how you managed to overcome it. You can also discuss here things that you found out about yourself as a professional – for example, that you enjoyed taking on a UX role that you didn’t have previous experience with, or that you were able to overcome some personal limitations or build on your existing skills in a new way.

Impact of the project

Showing impact is always good. How did you measure the impact of your work? By using analytics, evaluation results, and even testimonials from your customers or users, or even your development or marketing team, you can demonstrate that your methodical approach to work brought about some positive change. Use before-after comparison data to demonstrate the extent of your impact. Verbatim positive quotes from your users or other project stakeholders are worth their weight (or rather, sentence length) in gold. Don’t go overboard, but mix and match the best evidence for the quality of your work to keep the end section brief and to the point.

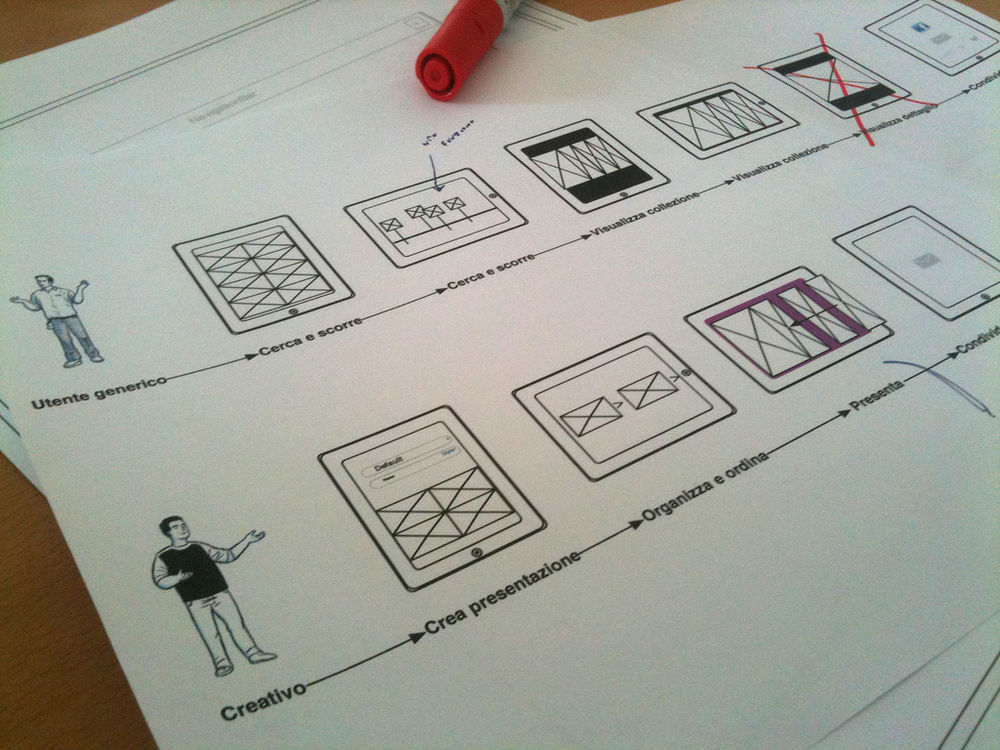

Copyright holder: Andreas Komninos, Interaction Design Foundation. Copyright terms and license: CC BY-SA 3.0

User reviews from app stores are a great source of obtaining testimonials to include in your case studies. Overall app ratings and download volumes are also great bits of information to show impact.

An excerpt from a case study ending section. Here, text and accompanying charts are used to demonstrate the impact of the work done by the UX professional.

Reflections on your experiences

You can include some information that shows you have a clear understanding of how further work can build on the success of what you’ve already done. This demonstrates forward thinking and exploratory desire. Something else you can reflect on is your choices during the project. In every project, there might be things you could do differently or improve upon. But be aware that the natural question that follows such statements is this: “Well, so why haven’t you done it?”

Don’t shoot yourself in the foot by listing all the things you wish you could have done, but focus on what you’ve actually done and lay out future directions. For example, if you’ve done the user research in an ongoing project, don’t say, “ After all this user research, it would have been great to progress to a prototype, but it’s not yet done ”; instead, say, “ This user research is now enabling developers to quickly progress to the prototyping stage. ”

Acknowledgments

The end of the case study section is where you should put in your acknowledgments to any other members of your team, if this wasn’t a personal project. Your goal by doing so is to highlight your team spirit and humility in recognizing that great projects are most typically the result of collaboration . Be careful here, because it’s easy to make the waters muddy by not being explicit about what YOU did. So, for example, don’t write something like “ I couldn’t have done it without John X. and Jane Y. ”, but instead say this: “ My user research and prototype design fed into the development work carried out by John X. User testing was carried out by Jane Y., whose findings informed further re-design that I did on the prototypes. ”

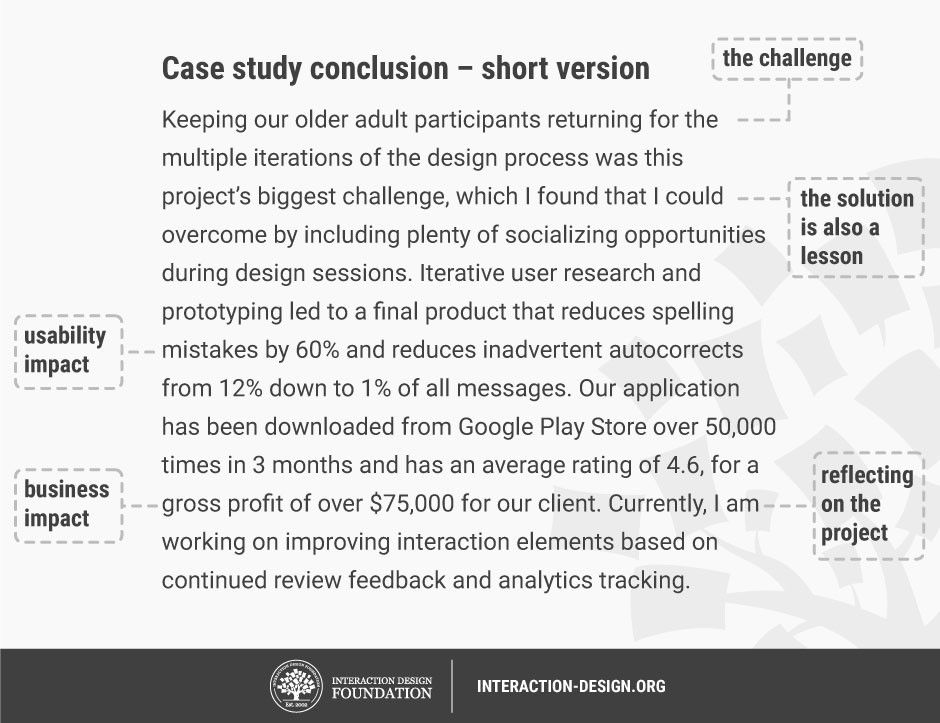

What is a good length for a UX case study ending?

UX case studies must be kept short, and, when considering the length of your beginning, process and conclusion sections, it’s the beginning and the conclusion sections that should be the shortest of all. In some case studies, you can keep the ending to two or three short phrases. Other, longer case studies about more complex projects may require a slightly longer section.

Remember, though, that the end section is your chance for a last, short but impactful impression. If the hotel receptionist from our early example started to say goodbye and then went on and on to ask you about your experience, sharing with you the comments of other clients, or started talking to you about where you are going next, and why, and maybe if he had been there himself, started to tell you all about where to go and what to see, well… you get the point. Keep it short, sincere and focused. And certainly, don’t try to make the project sound more important than it was. Recruiters are not stupid – they’ve been there and done that, so they know.

Putting it all together

In the example below, we will show how you can address the points above using text. We are going to focus on the three main questions here, so you can see an example of this in action, for a longer case study.

An example ending section for a longer case study, addressing all aspects: Lessons, impact, reflection and acknowledgments.

Here is how we might structure the text for a shorter version of the same case study, focusing on the bare essentials:

An example ending section for a shorter case study, addressing the most critical aspects: Lessons, impact and reflection. Acknowledgments are being sacrificed for the sake of brevity here, but perhaps that’s OK – you might mention it in the middle part of the case study.

The Take Away

The end part of your case study needs as much care and attention as the rest of it does. You shouldn’t neglect it just because it’s the last thing in the case study. It’s not hard work if you know the basics, and here, we’ve given you the pointers you need to ensure that you don’t miss out anything important. The end part of the case study should leave your recruiters with a good (hopefully, very good) last impression of you and your work, so give it the thorough consideration it needs, to ensure it doesn’t undo all the hard work you’ve put into the case study.

References & Where to Learn More

Copyright holder: Andrew Hurley, Flickr. Copyright terms and license: CC BY-SA 2.0

Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1968). Chapter: Human memory : A proposed system and its control processes. In Spence, K. W., & Spence, J. T. The psychology of learning and motivation (Volume 2). New York: Academic Press. pp. 89–195.

McLeod, S. (2008). Serial Position Effect

How to Create a UX Portfolio

Get Weekly Design Insights

Topics in this article, what you should read next, how to change your career from graphic design to ux design.

- 1.4k shares

How to Change Your Career from Marketing to UX Design

- 1.1k shares

- 3 years ago

How to Change Your Career from Web Design to UX Design

The Ultimate Guide to Understanding UX Roles and Which One You Should Go For

7 Tips to Improve Your UX Design Practice

How to create the perfect structure for a UX case study

7 Powerful Steps for Creating the Perfect Freelance CV

Tips for Writing a CV for a UX Job Application

15 Popular Reasons to Become a Freelancer or Entrepreneur

- 4 years ago

The Design Career Map – Learn How to Get Ahead in Your Work

Open Access—Link to us!

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge . Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change , cite this article , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge !

Privacy Settings

Our digital services use necessary tracking technologies, including third-party cookies, for security, functionality, and to uphold user rights. Optional cookies offer enhanced features, and analytics.

Experience the full potential of our site that remembers your preferences and supports secure sign-in.

Governs the storage of data necessary for maintaining website security, user authentication, and fraud prevention mechanisms.

Enhanced Functionality

Saves your settings and preferences, like your location, for a more personalized experience.

Referral Program

We use cookies to enable our referral program, giving you and your friends discounts.

Error Reporting

We share user ID with Bugsnag and NewRelic to help us track errors and fix issues.

Optimize your experience by allowing us to monitor site usage. You’ll enjoy a smoother, more personalized journey without compromising your privacy.

Analytics Storage

Collects anonymous data on how you navigate and interact, helping us make informed improvements.

Differentiates real visitors from automated bots, ensuring accurate usage data and improving your website experience.

Lets us tailor your digital ads to match your interests, making them more relevant and useful to you.

Advertising Storage

Stores information for better-targeted advertising, enhancing your online ad experience.

Personalization Storage

Permits storing data to personalize content and ads across Google services based on user behavior, enhancing overall user experience.

Advertising Personalization

Allows for content and ad personalization across Google services based on user behavior. This consent enhances user experiences.

Enables personalizing ads based on user data and interactions, allowing for more relevant advertising experiences across Google services.

Receive more relevant advertisements by sharing your interests and behavior with our trusted advertising partners.

Enables better ad targeting and measurement on Meta platforms, making ads you see more relevant.

Allows for improved ad effectiveness and measurement through Meta’s Conversions API, ensuring privacy-compliant data sharing.

LinkedIn Insights

Tracks conversions, retargeting, and web analytics for LinkedIn ad campaigns, enhancing ad relevance and performance.

LinkedIn CAPI

Enhances LinkedIn advertising through server-side event tracking, offering more accurate measurement and personalization.

Google Ads Tag

Tracks ad performance and user engagement, helping deliver ads that are most useful to you.

Share Knowledge, Get Respect!

or copy link

Cite according to academic standards

Simply copy and paste the text below into your bibliographic reference list, onto your blog, or anywhere else. You can also just hyperlink to this article.

New to UX Design? We’re giving you a free ebook!

Download our free ebook The Basics of User Experience Design to learn about core concepts of UX design.

In 9 chapters, we’ll cover: conducting user interviews, design thinking, interaction design, mobile UX design, usability, UX research, and many more!

New to UX Design? We’re Giving You a Free ebook!

How to Write a Psychology Case Study: Expert Tips

Have you ever heard of Phineas Gage, a man whose life story became a legendary case study in the annals of psychology? In the mid-19th century, Gage, a railroad construction foreman, survived a near-fatal accident when an iron rod pierced through his skull, severely damaging his brain. What makes this tale truly remarkable is that, despite his physical recovery, Gage's personality underwent a dramatic transformation. He went from being a mild-mannered and responsible individual to becoming impulsive and unpredictable. This remarkable case marked the dawn of psychology's fascination with understanding the intricate workings of the human mind. Case studies, like the one of Phineas Gage, have been a cornerstone of our understanding of human behavior ever since.

Short Description

In this article, we'll unravel the secrets of case study psychology as the powerful tool of this field. We will explore its essence and why these investigations are so crucial in understanding human behavior. Discover the various types of case studies, gain insights from real-world examples, and uncover the essential steps and expert tips on how to craft your very own compelling study. Get ready to embark on a comprehensive exploration of this invaluable research method.

Ready to Uncover the Secrets of the Mind?

Our team of skilled psychologists and wordsmiths is here to craft a masterpiece from your ideas.

What Is a Case Study in Psychology

A case study psychology definition can be compared to a magnifying glass turned toward a single individual, group, or phenomenon. According to our paper writer , it's a focused investigation that delves deep into the unique complexities of a particular subject. Rather than sifting through mountains of data, a case study allows us to zoom in and scrutinize the details, uncovering the 'whys' and 'hows' that often remain hidden in broader research.

A psychology case study is not about generalizations or sweeping theories; it's about the intricacies of real-life situations. It's the detective work of the field, aiming to unveil the 'story behind the data' and offering profound insights into human behavior, emotions, and experiences. So, while psychology as a whole may study the forest, a case study takes you on a journey through the trees, revealing the unique patterns, quirks, and secrets that make each one distinct.

The Significance of Psychology Case Studies

Writing a psychology case study plays a pivotal role in the world of research and understanding the human mind. Here's why they are so crucial, according to our ' do my essay ' experts:

.webp)

- In-Depth Exploration: Case studies provide an opportunity to explore complex human behaviors and experiences in great detail. By diving deep into a specific case, researchers can uncover nuances that might be overlooked in broader studies.

- Unique Perspectives: Every individual and situation is unique, and case studies allow us to capture this diversity. They offer a chance to highlight the idiosyncrasies that make people who they are and situations what they are.

- Theory Testing: Case studies are a way to test and refine psychological theories in real-world scenarios. They provide practical insights that can validate or challenge existing hypotheses.

- Practical Applications: The knowledge gained from case studies can be applied to various fields, from clinical psychology to education and business. It helps professionals make informed decisions and develop effective interventions.

- Holistic Understanding: Case studies often involve a comprehensive examination of an individual's life or a particular phenomenon. This holistic approach contributes to a more profound comprehension of human behavior and the factors that influence it.

Varieties of a Psychology Case Study

When considering how to write a psychology case study, you should remember that it is a diverse field, and so are the case studies conducted within it. Let's explore the different types from our ' write my research paper ' experts:

- Descriptive Case Studies: These focus on providing a detailed description of a particular case or phenomenon. They serve as a foundation for further research and can be valuable in generating hypotheses.

- Exploratory Case Studies: Exploratory studies aim to investigate novel or scarcely explored areas within psychology. They often pave the way for more in-depth research by generating new questions and ideas.

- Explanatory Case Studies: These delve into the 'why' and 'how' of a particular case, seeking to explain the underlying factors or mechanisms that drive a particular behavior or event.

- Instrumental Case Studies: In these cases, the individual or situation under examination is instrumental in testing or illustrating a particular theory or concept in psychology.

- Intrinsic Case Studies: Contrary to instrumental case studies, intrinsic ones explore a case for its own unique significance, aiming to understand the specific details and intricacies of that case without primarily serving as a tool to test broader theories.

- Collective Case Studies: These studies involve the examination of multiple cases to identify common patterns or differences. They are helpful when researchers seek to generalize findings across a group.

- Longitudinal Case Studies: Longitudinal studies track a case over an extended period, allowing researchers to observe changes and developments over time.

- Cross-Sectional Case Studies: In contrast, cross-sectional case studies involve the examination of a case at a single point in time, offering a snapshot of that particular moment.

The Advantages of Psychology Case Studies

Learning how to write a case study offers numerous benefits, making it a valuable research method in the field. Here are some of the advantages:

- Rich Insights: Case studies provide in-depth insights into individual behavior and experiences, allowing researchers to uncover unique patterns, motivations, and complexities.

- Holistic Understanding: By examining a case in its entirety, researchers can gain a comprehensive understanding of the factors that influence human behavior, including psychological, environmental, and contextual aspects.

- Theory Development: Case studies contribute to theory development by providing real-world examples that can validate or refine existing psychological theories.

- Personalized Approach: Researchers can tailor their methods to fit the specific case, making it a flexible approach that can adapt to the unique characteristics of the subject.

- Application in Practice: The knowledge gained from case studies can be applied in various practical settings, such as clinical psychology, education, and organizational management, to develop more effective interventions and solutions.

- Real-World Relevance: Psychology case studies often address real-life issues, making the findings relevant and applicable to everyday situations.

- Qualitative Data: They generate qualitative data, which can be rich in detail and context, offering a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

- Hypothesis Generation: Case studies can spark new research questions and hypotheses, guiding further investigations in psychology.

- Ethical Considerations: In some cases, case studies can be conducted in situations where experimental research may not be ethical, providing valuable insights that would otherwise be inaccessible.

- Educational Value: Case studies are commonly used as teaching tools, helping students apply theoretical knowledge to practical scenarios and encouraging critical thinking.

How to Write a Psychology Case Study

Crafting a psychology case study requires a meticulous approach that combines the art of storytelling with the precision of scientific analysis. In this section, we'll provide you with a step-by-step guide on how to create an engaging and informative psychology case study, from selecting the right subject to presenting your findings effectively.

Step 1: Gathering Information for Subject Profiling

To create a comprehensive psychology case study, the first crucial step is gathering all the necessary information to build a detailed profile of your subject. This profile forms the backbone of your study, offering a deeper understanding of the individual or situation you're examining.

According to our case study writing service , you should begin by collecting a range of data, including personal history, demographics, behavioral observations, and any relevant documentation. Interviews, surveys, and direct observations are common methods to gather this information. Ensure that the data you collect is relevant to the specific aspects of the subject's life or behavior that you intend to investigate.

By meticulously gathering and organizing this data, you'll lay the foundation for a robust case study that not only informs your readers but also provides the context needed to make meaningful observations and draw insightful conclusions.

Step 2: Selecting a Case Study Method

Once you have gathered all the essential information about your subject, the next step in crafting a psychology case study is to choose the most appropriate case study method. The method you select will determine how you approach the analysis and presentation of your findings. Here are some common case study methods to consider:

- Single-Subject Case Study: This method focuses on a single individual or a particular event, offering a detailed examination of that subject's experiences and behaviors.

- Comparative Case Study: In this approach, you analyze two or more cases to draw comparisons or contrasts, revealing patterns or differences among them.

- Longitudinal Case Study: A longitudinal study involves tracking a subject or group over an extended period, observing changes and developments over time.

- Cross-Sectional Case Study: This method involves analyzing subjects at a specific point in time, offering a snapshot of their current state.

- Exploratory Case Study: Exploratory studies are ideal for investigating new or underexplored areas within psychology.

- Explanatory Case Study: If your goal is to uncover the underlying factors and mechanisms behind a specific behavior or phenomenon, the explanatory case study is a suitable choice.

Step 3: Gathering Background Information on the Subject

In the process of learning how to write a psychology case study, it's essential to delve into the subject's background to build a complete and meaningful narrative. The background information serves as a crucial context for understanding the individual or situation under investigation.

To gather this information effectively:

- Personal History: Explore the subject's life history, including their upbringing, family background, education, and career path. These details provide insights into their development and experiences.

- Demographics: Collect demographic data, such as age, gender, and cultural background, as part of your data collection process. These factors can be influential in understanding behavior and experiences.

- Relevant Events: Identify any significant life events, experiences, or transitions that might have had an impact on the subject's psychology and behavior.

- Psychological Factors: Assess the subject's psychological profile, including personality traits, cognitive abilities, and emotional well-being, if applicable.

- Social and Environmental Factors: Consider the subject's social and environmental context, including relationships, living conditions, and cultural influences.

Step 4: Detailing the Subject's Challenges

While writing a psychology case study, it is crucial to provide a thorough description of the subject's symptoms or the challenges they are facing. This step allows you to dive deeper into the specific issues that are the focus of your study, providing clarity and context for your readers.

To effectively describe the subject's symptoms or challenges, consider the following from our psychology essay writing service :

- Symptomatology: Enumerate the symptoms, behaviors, or conditions that the subject is experiencing. This could include emotional states, cognitive patterns, or any psychological distress.

- Onset and Duration: Specify when the symptoms or challenges began and how long they have persisted. This timeline can offer insights into the progression of the issue.

- Impact: Discuss the impact of these symptoms on the subject's daily life, relationships, and overall well-being. Consider their functional impairment and how it relates to the observed issues.

- Relevant Diagnoses: If applicable, mention any psychological or psychiatric diagnoses that have been made in relation to the subject's symptoms. This information can shed light on the clinical context of the case.

Step 5: Analyzing Data and Establishing a Diagnosis

Once you have gathered all the necessary information and described the subject's symptoms or challenges, the next critical step is to analyze the data and, if applicable, establish a diagnosis.

To effectively analyze the data and potentially make a diagnosis:

- Data Synthesis: Organize and synthesize the collected data, bringing together all the relevant information in a coherent and structured manner.

- Pattern Recognition: Identify patterns, themes, and connections within the data. Look for recurring behaviors, triggers, or factors that might contribute to the observed symptoms or challenges.

- Comparison with Diagnostic Criteria: If the study involves diagnosing a psychological condition, compare the subject's symptoms and experiences with established diagnostic criteria, such as those found in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).

- Professional Consultation: It is advisable to consult with qualified professionals, such as clinical psychologists or psychiatrists, to ensure that the diagnosis, if applicable, is accurate and well-informed.

- Thorough Assessment: Ensure a comprehensive evaluation of the data, considering all possible factors and nuances before reaching any conclusions.

Step 6: Choosing an Intervention Strategy

Choosing an appropriate intervention approach is a pivotal phase in case study psychology, especially if your subject's case involves therapeutic considerations. Here's how to navigate this step effectively:

- Review Findings: Revisit the data and analysis you've conducted to gain a comprehensive understanding of the subject's symptoms, challenges, and needs.

- Consultation: If you're not a qualified mental health professional, it's advisable to consult with experts in the field, such as clinical psychologists or psychiatrists. They can offer valuable insights and recommendations for treatment.

- Tailored Approach: Select a treatment approach that is tailored to the subject's specific needs and diagnosis, if applicable. This could involve psychotherapy, medication, lifestyle changes, or a combination of interventions.

- Goal Setting: Clearly define the goals and objectives of the chosen treatment approach. What do you hope to achieve, and how will progress be measured?

- Informed Consent: If the subject is involved in the decision-making process, ensure they provide informed consent and are fully aware of the chosen treatment's details, potential benefits, and risks.

- Implementation and Monitoring: Once the treatment plan is established, put it into action and closely monitor the subject's progress. Make necessary adjustments based on their responses and evolving needs.

- Ethical Considerations: Be mindful of ethical standards and maintain the subject's confidentiality and well-being throughout the treatment process.

Step 7: Explaining Treatment Objectives and Procedures

In the final phases of your psychology case study, it's essential to provide a clear and detailed description of the treatment goals and processes that have been implemented. This step ensures that your readers understand the therapeutic journey and its intended outcomes.

Here's how to effectively describe treatment goals and processes:

- Specific Goals: Outline the specific goals of the chosen treatment approach. What are you aiming to achieve in terms of the subject's well-being, symptom reduction, or overall improvement?

- Interventions: Describe the therapeutic interventions that have been employed, including psychotherapeutic techniques, medications, or other strategies. Explain how these interventions are intended to address the subject's challenges.

- Timelines: Specify the expected timeline for achieving treatment goals. This may include short-term and long-term objectives, as well as milestones for assessing progress.

- Monitoring and Evaluation: Discuss the methods used to monitor and evaluate the subject's response to treatment. How are you measuring progress or setbacks, and how frequently are assessments conducted?

- Adjustments: Explain how the treatment plan is adaptable as you would in a persuasive essay . If modifications to the goals or interventions are required, clarify the decision-making process for making such adjustments.

- Collaboration: If relevant, highlight any collaboration with other professionals involved in the subject's care, emphasizing a multidisciplinary approach for comprehensive treatment.

- Patient Involvement: If the subject is actively engaged in their treatment, detail their role, responsibilities, and any tools or resources provided to support their participation.

Step 8: Crafting the Discussion and Concluding Remarks

In the final phase of your psychology case study, the discussion section is where you interpret the findings, reflect on the significance of your study, and offer insights into the broader implications of the case. Here's how to effectively write this section:

- Interpretation: Begin by interpreting the data and analysis you've presented in your case study. What do the findings reveal about the subject's psychology, behavior, or experiences?

- Relevance to Research Questions: Discuss how your findings align with or deviate from the initial research questions or hypotheses you set out to investigate.

- Comparison with Literature: Compare your findings with existing literature and research in the field of psychology. Highlight any consistencies or disparities and explain their significance.

- Clinical Considerations: If your case study has clinical or practical relevance, address the implications for therapeutic approaches, interventions, or clinical practices.

- Generalizability: Evaluate the extent to which the insights from your case study can be generalized to a broader population or other similar cases.

- Strengths and Limitations: Be candid about the strengths and limitations of your case study. Acknowledge any constraints or biases and explain how they might have influenced the results.

- Future Research Directions: Suggest areas for future research or additional case studies that could build on your findings and deepen our understanding of the subject matter.

- Conclusion: Summarize the key takeaways from your case study and provide a concise conclusion that encapsulates the main findings and their significance.

5 Helpful Tips for Crafting a Psychology Case Study

Much like learning how to write a synthesis essay , writing a compelling case study involves careful planning and attention to detail. Here are some essential guidelines to help you in the process:

- Consider Cultural Sensitivity: Recognize the importance of cultural diversity and sensitivity in your case study. Take into account the cultural background of your subject and its potential impact on their behavior and experiences.

- Use Clear Citations: Properly cite all sources, including previous research, theories, and relevant literature. Accurate citations lend credibility to your case study and acknowledge the work of others.

- Engage in Peer Discussion: Engage in discussions with peers or colleagues in the field throughout the case study process. Collaborative brainstorming and sharing insights can lead to a more well-rounded study.

- Be Mindful of Ethics: Continuously monitor and reassess the ethical considerations of your case study, especially when it involves sensitive topics or individuals. Prioritize the well-being and rights of your participants.

- Practice Patience and Persistence: Case studies can be time-consuming and may encounter setbacks. Exercise patience and persistence to ensure the quality and comprehensiveness of your research.

Case Study Psychology Example

In this psychology case study example, we delve into a compelling story that serves as a window into the fascinating realm of psychological research, offering valuable insights and practical applications.

Final Outlook

As we conclude this comprehensive writing guide on how to write a psychology case study, remember that every case holds a unique story waiting to be unraveled. The art of crafting a compelling case study lies in your hands, offering a window into the intricate world of the human mind. We encourage you to embark on your own investigative journeys, armed with the knowledge and skills acquired here, to contribute to the ever-evolving landscape of psychology.

Ready to Unravel the Mysteries of the Human Mind?

Our team of psychologists and researchers is adept at transforming complex concepts into engaging stories, ensuring that when you request us to ' write my case study for me ,' your unique vision is effectively brought to life.

Related Articles

.webp)

Understanding Case Study Method in Research: A Comprehensive Guide

Table of Contents

Have you ever wondered how researchers uncover the nuanced layers of individual experiences or the intricate workings of a particular event? One of the keys to unlocking these mysteries lies in the qualitative research focusing on a single subject in its real-life context.">case study method , a research strategy that might seem straightforward at first glance but is rich with complexity and insightful potential. Let’s dive into the world of case studies and discover why they are such a valuable tool in the arsenal of research methods.

What is a Case Study Method?

At its core, the case study method is a form of qualitative research that involves an in-depth, detailed examination of a single subject, such as an individual, group, organization, event, or phenomenon. It’s a method favored when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident, and where multiple sources of data are used to illuminate the case from various perspectives. This method’s strength lies in its ability to provide a comprehensive understanding of the case in its real-life context.

Historical Context and Evolution of Case Studies

Case studies have been around for centuries, with their roots in medical and psychological research. Over time, their application has spread to disciplines like sociology, anthropology, business, and education. The evolution of this method has been marked by a growing appreciation for qualitative data and the rich, contextual insights it can provide, which quantitative methods may overlook.

Characteristics of Case Study Research

What sets the case study method apart are its distinct characteristics:

- Intensive Examination: It provides a deep understanding of the case in question, considering the complexity and uniqueness of each case.

- Contextual Analysis: The researcher studies the case within its real-life context, recognizing that the context can significantly influence the phenomenon.

- Multiple Data Sources: Case studies often utilize various data sources like interviews, observations, documents, and reports, which provide multiple perspectives on the subject.

- Participant’s Perspective: This method often focuses on the perspectives of the participants within the case, giving voice to those directly involved.

Types of Case Studies

There are different types of case studies, each suited for specific research objectives:

- Exploratory: These are conducted before large-scale research projects to help identify questions, select measurement constructs, and develop hypotheses.

- Descriptive: These involve a detailed, in-depth description of the case, without attempting to determine cause and effect.

- Explanatory: These are used to investigate cause-and-effect relationships and understand underlying principles of certain phenomena.

- Intrinsic: This type is focused on the case itself because the case presents an unusual or unique issue.

- Instrumental: Here, the case is secondary to understanding a broader issue or phenomenon.

- Collective: These involve studying a group of cases collectively or comparably to understand a phenomenon, population, or general condition.

The Process of Conducting a Case Study

Conducting a case study involves several well-defined steps:

- Defining Your Case: What or who will you study? Define the case and ensure it aligns with your research objectives.

- Selecting Participants: If studying people, careful selection is crucial to ensure they fit the case criteria and can provide the necessary insights.

- Data Collection: Gather information through various methods like interviews, observations, and reviewing documents.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the collected data to identify patterns, themes, and insights related to your research question.

- Reporting Findings: Present your findings in a way that communicates the complexity and richness of the case study, often through narrative.

Case Studies in Practice: Real-world Examples

Case studies are not just academic exercises; they have practical applications in every field. For instance, in business, they can explore consumer behavior or organizational strategies. In psychology, they can provide detailed insight into individual behaviors or conditions. Education often uses case studies to explore teaching methods or learning difficulties.

Advantages of Case Study Research

While the case study method has its critics, it offers several undeniable advantages:

- Rich, Detailed Data: It captures data too complex for quantitative methods.

- Contextual Insights: It provides a better understanding of the phenomena in its natural setting.

- Contribution to Theory: It can generate and refine theory, offering a foundation for further research.

Limitations and Criticism

However, it’s important to acknowledge the limitations and criticisms:

- Generalizability : Findings from case studies may not be widely generalizable due to the focus on a single case.

- Subjectivity: The researcher’s perspective may influence the study, which requires careful reflection and transparency.

- Time-Consuming: They require a significant amount of time to conduct and analyze properly.

Concluding Thoughts on the Case Study Method

The case study method is a powerful tool that allows researchers to delve into the intricacies of a subject in its real-world environment. While not without its challenges, when executed correctly, the insights garnered can be incredibly valuable, offering depth and context that other methods may miss. Robert K\. Yin ’s advocacy for this method underscores its potential to illuminate and explain contemporary phenomena, making it an indispensable part of the researcher’s toolkit.

Reflecting on the case study method, how do you think its application could change with the advancements in technology and data analytics? Could such a traditional method be enhanced or even replaced in the future?

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 0 / 5. Vote count: 0

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Submit Comment

Research Methods in Psychology

1 Introduction to Psychological Research – Objectives and Goals, Problems, Hypothesis and Variables

- Nature of Psychological Research

- The Context of Discovery

- Context of Justification

- Characteristics of Psychological Research

- Goals and Objectives of Psychological Research

2 Introduction to Psychological Experiments and Tests

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Extraneous Variables

- Experimental and Control Groups

- Introduction of Test

- Types of Psychological Test

- Uses of Psychological Tests

3 Steps in Research

- Research Process

- Identification of the Problem

- Review of Literature

- Formulating a Hypothesis

- Identifying Manipulating and Controlling Variables

- Formulating a Research Design

- Constructing Devices for Observation and Measurement

- Sample Selection and Data Collection

- Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Hypothesis Testing

- Drawing Conclusion

4 Types of Research and Methods of Research

- Historical Research

- Descriptive Research

- Correlational Research

- Qualitative Research

- Ex-Post Facto Research

- True Experimental Research

- Quasi-Experimental Research

5 Definition and Description Research Design, Quality of Research Design

- Research Design

- Purpose of Research Design

- Design Selection

- Criteria of Research Design

- Qualities of Research Design

6 Experimental Design (Control Group Design and Two Factor Design)

- Experimental Design

- Control Group Design

- Two Factor Design

7 Survey Design

- Survey Research Designs

- Steps in Survey Design

- Structuring and Designing the Questionnaire

- Interviewing Methodology

- Data Analysis

- Final Report

8 Single Subject Design

- Single Subject Design: Definition and Meaning

- Phases Within Single Subject Design

- Requirements of Single Subject Design

- Characteristics of Single Subject Design

- Types of Single Subject Design

- Advantages of Single Subject Design

- Disadvantages of Single Subject Design

9 Observation Method

- Definition and Meaning of Observation

- Characteristics of Observation

- Types of Observation

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Observation

- Guides for Observation Method

10 Interview and Interviewing

- Definition of Interview

- Types of Interview

- Aspects of Qualitative Research Interviews

- Interview Questions

- Convergent Interviewing as Action Research

- Research Team

11 Questionnaire Method

- Definition and Description of Questionnaires

- Types of Questionnaires

- Purpose of Questionnaire Studies

- Designing Research Questionnaires

- The Methods to Make a Questionnaire Efficient

- The Types of Questionnaire to be Included in the Questionnaire

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Questionnaire

- When to Use a Questionnaire?

12 Case Study

- Definition and Description of Case Study Method

- Historical Account of Case Study Method

- Designing Case Study

- Requirements for Case Studies

- Guideline to Follow in Case Study Method

- Other Important Measures in Case Study Method

- Case Reports

13 Report Writing

- Purpose of a Report

- Writing Style of the Report

- Report Writing – the Do’s and the Don’ts

- Format for Report in Psychology Area

- Major Sections in a Report

14 Review of Literature

- Purposes of Review of Literature

- Sources of Review of Literature

- Types of Literature

- Writing Process of the Review of Literature

- Preparation of Index Card for Reviewing and Abstracting

15 Methodology

- Definition and Purpose of Methodology

- Participants (Sample)

- Apparatus and Materials

16 Result, Analysis and Discussion of the Data

- Definition and Description of Results

- Statistical Presentation

- Tables and Figures

17 Summary and Conclusion

- Summary Definition and Description

- Guidelines for Writing a Summary

- Writing the Summary and Choosing Words

- A Process for Paraphrasing and Summarising

- Summary of a Report

- Writing Conclusions

18 References in Research Report

- Reference List (the Format)

- References (Process of Writing)

- Reference List and Print Sources

- Electronic Sources

- Book on CD Tape and Movie

- Reference Specifications

- General Guidelines to Write References

Share on Mastodon

A case study is a research method that extensively explores a particular subject, situation, or individual through in-depth analysis, often to gain insights into real-world phenomena or complex issues. It involves the comprehensive examination of multiple data sources, such as interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, to provide a rich and holistic understanding of the subject under investigation.

Case studies are conducted to:

- Investigate a specific problem, event, or phenomenon

- Explore unique or atypical situations

- Examine the complexities and intricacies of a subject in its natural context

- Develop theories, propositions, or hypotheses for further research

- Gain practical insights for decision-making or problem-solving

A typical case study consists of the following components:

- Introduction: Provides a brief background and context for the study, including the purpose and research questions.

- Case Description: Describes the subject of the case study, including its relevant characteristics, settings, and participants.

- Data Collection: Details the methods used to gather data, such as interviews, observations, surveys, or document analysis.

- Data Analysis: Explains the techniques employed to analyze the collected data and derive meaningful insights.

- Findings: Presents the key discoveries and outcomes of the case study in a logical and organized manner.

- Discussion: Interprets the findings, relates them to existing theories or frameworks, discusses their implications, and addresses any limitations.

- Conclusion: Summarizes the main findings, highlights the significance of the research, and suggests potential avenues for future investigations.

Case studies offer several benefits, including:

- Providing a deep understanding of complex and context-dependent phenomena

- Generating detailed and rich qualitative data

- Allowing researchers to explore multiple perspectives and factors influencing the subject

- Offering practical insights for professionals and practitioners

- Allowing for the examination of rare or unique occurrences that cannot be replicated in experimental settings

What Is a Case Study in Psychology?

Categories Research Methods

A case study is a research method used in psychology to investigate a particular individual, group, or situation in depth . It involves a detailed analysis of the subject, gathering information from various sources such as interviews, observations, and documents.

In a case study, researchers aim to understand the complexities and nuances of the subject under investigation. They explore the individual’s thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and experiences to gain insights into specific psychological phenomena.

This type of research can provide great detail regarding a particular case, allowing researchers to examine rare or unique situations that may not be easily replicated in a laboratory setting. They offer a holistic view of the subject, considering various factors influencing their behavior or mental processes.

By examining individual cases, researchers can generate hypotheses, develop theories, and contribute to the existing body of knowledge in psychology. Case studies are often utilized in clinical psychology, where they can provide valuable insights into the diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes of specific psychological disorders.

Case studies offer a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of complex psychological phenomena, providing researchers with valuable information to inform theory, practice, and future research.

Table of Contents

Examples of Case Studies in Psychology

Case studies in psychology provide real-life examples that illustrate psychological concepts and theories. They offer a detailed analysis of specific individuals, groups, or situations, allowing researchers to understand psychological phenomena better. Here are a few examples of case studies in psychology:

Phineas Gage

This famous case study explores the effects of a traumatic brain injury on personality and behavior. A railroad construction worker, Phineas Gage survived a severe brain injury that dramatically changed his personality.

This case study helped researchers understand the role of the frontal lobe in personality and social behavior.

Little Albert

Conducted by behaviorist John B. Watson, the Little Albert case study aimed to demonstrate classical conditioning. In this study, a young boy named Albert was conditioned to fear a white rat by pairing it with a loud noise.

This case study provided insights into the process of fear conditioning and the impact of early experiences on behavior.

Genie’s case study focused on a girl who experienced extreme social isolation and deprivation during her childhood. This study shed light on the critical period for language development and the effects of severe neglect on cognitive and social functioning.

These case studies highlight the value of in-depth analysis and provide researchers with valuable insights into various psychological phenomena. By examining specific cases, psychologists can uncover unique aspects of human behavior and contribute to the field’s knowledge and understanding.

Types of Case Studies in Psychology

Psychology case studies come in various forms, each serving a specific purpose in research and analysis. Understanding the different types of case studies can help researchers choose the most appropriate approach.

Descriptive Case Studies

These studies aim to describe a particular individual, group, or situation. Researchers use descriptive case studies to explore and document specific characteristics, behaviors, or experiences.

For example, a descriptive case study may examine the life and experiences of a person with a rare psychological disorder.

Exploratory Case Studies

Exploratory case studies are conducted when there is limited existing knowledge or understanding of a particular phenomenon. Researchers use these studies to gather preliminary information and generate hypotheses for further investigation.

Exploratory case studies often involve in-depth interviews, observations, and analysis of existing data.

Explanatory Case Studies

These studies aim to explain the causal relationship between variables or events. Researchers use these studies to understand why certain outcomes occur and to identify the underlying mechanisms or processes.

Explanatory case studies often involve comparing multiple cases to identify common patterns or factors.

Instrumental Case Studies

Instrumental case studies focus on using a particular case to gain insights into a broader issue or theory. Researchers select cases that are representative or critical in understanding the phenomenon of interest.

Instrumental case studies help researchers develop or refine theories and contribute to the general knowledge in the field.

By utilizing different types of case studies, psychologists can explore various aspects of human behavior and gain a deeper understanding of psychological phenomena. Each type of case study offers unique advantages and contributes to the overall body of knowledge in psychology.

How to Collect Data for a Case Study

There are a variety of ways that researchers gather the data they need for a case study. Some sources include:

- Directly observing the subject

- Collecting information from archival records

- Conducting interviews

- Examining artifacts related to the subject

- Examining documents that provide information about the subject

The way that this information is collected depends on the nature of the study itself

Prospective Research

In a prospective study, researchers observe the individual or group in question. These observations typically occur over a period of time and may be used to track the progress or progression of a phenomenon or treatment.

Retrospective Research

A retrospective case study involves looking back on a phenomenon. Researchers typically look at the outcome and then gather data to help them understand how the individual or group reached that point.

Benefits of a Case Study

Case studies offer several benefits in the field of psychology. They provide researchers with a unique opportunity to delve deep into specific individuals, groups, or situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of complex phenomena.

Case studies offer valuable insights that can inform theory development and practical applications by examining real-life examples.

Complex Data

One of the key benefits of case studies is their ability to provide complex and detailed data. Researchers can gather in-depth information through various methods such as interviews, observations, and analysis of existing records.

This depth of data allows for a thorough exploration of the factors influencing behavior and the underlying mechanisms at play.

Unique Data

Additionally, case studies allow researchers to study rare or unique cases that may not be easily replicated in experimental settings. This enables the examination of phenomena that are difficult to study through other psychology research methods .

By focusing on specific cases, researchers can uncover patterns, identify causal relationships, and generate hypotheses for further investigation.

General Knowledge

Case studies can also contribute to the general knowledge of psychology by providing real-world examples that can be used to support or challenge existing theories. They offer a bridge between theory and practice, allowing researchers to apply theoretical concepts to real-life situations and vice versa.

Case studies offer a range of benefits in psychology, including providing rich and detailed data, studying unique cases, and contributing to theory development. These benefits make case studies valuable in understanding human behavior and psychological phenomena.

Limitations of a Case Study

While case studies offer numerous benefits in the field of psychology, they also have certain limitations that researchers need to consider. Understanding these limitations is crucial for interpreting the findings and generalizing the results.

Lack of Generalizability

One limitation of case studies is the issue of generalizability. Since case studies focus on specific individuals, groups, and situations, applying the findings to a larger population can be challenging. The unique characteristics and circumstances of the case may not be representative of the broader population, making it difficult to draw universal conclusions.

Researcher bias is another possible limitation. The researcher’s subjective interpretation and personal beliefs can influence the data collection, analysis, and interpretation process. This bias can affect the objectivity and reliability of the findings, raising questions about the study’s validity.

Case studies are often time-consuming and resource-intensive. They require extensive data collection, analysis, and interpretation, which can be lengthy. This can limit the number of cases that can be studied and may result in a smaller sample size, reducing the study’s statistical power.

Case studies are retrospective in nature, relying on past events and experiences. This reliance on memory and self-reporting can introduce recall bias and inaccuracies in the data. Participants may forget or misinterpret certain details, leading to incomplete or unreliable information.

Despite these limitations, case studies remain a valuable research tool in psychology. By acknowledging and addressing these limitations, researchers can enhance the validity and reliability of their findings, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of human behavior and psychological phenomena.

While case studies have limitations, they remain valuable when researchers acknowledge and address these concerns, leading to more reliable and valid findings in psychology.

Alpi, K. M., & Evans, J. J. (2019). Distinguishing case study as a research method from case reports as a publication type. Journal of the Medical Library Association , 107(1). https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2019.615

Crowe, S., Cresswell, K., Robertson, A., Huby, G., Avery, A., & Sheikh, A. (2011). The case study approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology , 11(1), 100. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Paparini, S., Green, J., Papoutsi, C., Murdoch, J., Petticrew, M., Greenhalgh, T., Hanckel, B., & Shaw, S. (2020). Case study research for better evaluations of complex interventions: Rationale and challenges. BMC Medicine , 18(1), 301. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01777-6

Willemsen, J. (2023). What is preventing psychotherapy case studies from having a greater impact on evidence-based practice, and how to address the challenges? Frontiers in Psychiatry , 13, 1101090. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1101090

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . United States, SAGE Publications, 2017.

How to Write a Good Case Study in Psychology (A Step-by-Step Guide)

- March 4, 2022

- Teaching Kids

A case study psychology is a type of research that uses real-life examples to help understand psychological concepts. This type of research can be used in a variety of settings, such as business, health care, education, and social services.

Case studies are typically composed of three parts: the problem or issue, the intervention or treatment, and the outcome. The problem or issue is what caused the person to seek help, and the intervention or treatment is what was done to try to solve it. The outcome is how things changed after the intervention or treatment was implemented.

Step by step instructions on how to write an effective case study in Psychology

1. Gain Knowledge About The Topic

To write a case study in psychology, you will need to do some research on the topic you are writing about. Make sure that you read journal articles, books, a case study example, and any other reliable sources in order to get a comprehensive understanding of the topic. You will also need to find a suitable example or examples of how psychological concepts have been applied in real-life situations. For example, a psychology student might interview a friend about how she balances her time between work and studies.

2. Research the Individual or Event

In this case, you can choose either a person or an event for your case study research. If you are writing about a specific event, look for past issues that relate to it and any ongoing ones that may have a connection to it.

You may choose to write about a specific problem or situation that affected the individual in some way, such as how it relates to their psychology. For example, you may want to study a man who has been in relationships with several women within the same time period and what effects this has on them.

If you are writing about a person, obtain biographical information and look for any psychological assessments that have been done on the individual.

3. Analyze The Information

Once you have gathered all the necessary information, it is time to go through it and identify important facts that will influence your paper.

This is where you use your skills of inductive and deductive reasoning, to analyze the information that you have gathered. You will usually look for patterns within this information and draw conclusions about how it has affected or contributed to their psychology.

Summarize each point in order to make note-taking easier later on when writing your case study.

4. Draft A Plan