The effects of perceived organizational support on employees’ sense of job insecurity in times of external threats: an empirical investigation under lockdown conditions in China

- Original Article

- Published: 24 March 2023

- Volume 22 , pages 1567–1591, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Luyang Zhou 1 , 2 ,

- Shengxiao Li 2 ,

- Lianxi Zhou 3 ,

- Hong Tao ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5274-0196 1 , 2 &

- Dave Bouckenooghe 4

2998 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This study examines how perceived organizational support (POS) can be leveraged to provide employees with guided responses to disruptive events. Specifically, this study addresses a previously overlooked yet practically relevant aspect of POS—its communicative role in managing employees’ feelings of job insecurity. Drawing on the social identity perspective and research on individuals’ psychological states of uncertainty, we argue that POS can have both direct and indirect influences on the sense of job insecurity in times of external threats. With this in mind, we used COVID-19 and resulting lockdowns in China as specific context examples of a disruptive event to administer a two-wave lagged survey measuring POS, perceived control, lockdown loneliness, and job insecurity. Theoretical arguments are put forward regarding organizational support for fostering individuals’ social identity and emotional well-being under deeply disruptive work situations. Overall, this study offers insights into how managers may develop risk management and organizationally adaptive practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Strategies for Coping with LGBT Discrimination at Work: a Systematic Literature Review

Liviu-Catalin Mara, Matías Ginieis & Ignasi Brunet-Icart

A meta-analysis of psychological empowerment: Antecedents, organizational outcomes, and moderating variables

Marta Llorente-Alonso, Cristina García-Ael & Gabriela Topa

The Impact of “Quiet Quitting” on Overall Organizational Behavior and Culture

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Disruptive events have been on the rise in recent years, spinning from labor disputes and demonstrations to the shortage of global supply chains and, most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Gustafsson et al., 2021 ; Lin et al., 2021 ; Oehmen et al., 2020 ). Unfortunately, organizations have little influence or control over the occurrence of these adverse events (Hartmann & Lussier, 2020 ). As the impact of the current COVID-19 disruption demonstrates, the toolbox for organizational adaptive responses needs to be updated and further developed (Butt, 2021 ; Haak-Saheem, 2020 ; Henry et al., 2021 ; Liu et al., 2020 ). The prolonged COVID-19 pandemic has spread long-lasting anxiety among communities and has fostered a general sense of insecurity at the sociopolitical, economic, and cultural levels, dramatically disrupting everyday life and business activities (Debata et al., 2020 ; Horn et al., 2021 ; Probst et al., 2020 ). Under these circumstances, an unprecedented magnitude of uncertainty has been experienced collectively regarding the threats and challenges of the COVID-19 outbreak. From a conceptual point of view, experienced uncertainty can derail how individuals respond to external threats and shape how they adapt themselves to their organizations’ responses to disruptive events (e.g., Liu et al., 2022 ; Slaughter et al., 2021 ; Tuan, 2022 ).

To our knowledge, few studies thus far have investigated the impact of organizational adaptive practices on employees’ responses to external threats under high levels of uncertainty (Oehmen et al., 2020 ). In response, the current research examines the communication function of perceived organizational support (POS) in relation to employees’ emotional responses, as well as perceived job insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic. In doing so, social identity theory (Ashforth & Mael, 1989 ; Dutton et al., 2010 ) was used along with prior research on emotions under the state of uncertainty (Slaughter et al., 2021 ). The social identity perspective, as it relates to employee identity and identification in the organization, is often used as a theoretical lens to explain different forms of work-related identities and organizational outcomes (Dutton et al., 2010 ). POS has been shown to manifest itself in communicative functions for supportive work conditions and reinforcement of the socioemotional needs of employees (Brown & Roloff, 2015 ; Neves & Eisenberger, 2012 ). Additionally, POS has often been linked to organizational response strategies and management communication effectiveness, especially in cases when employees are exposed to disruptive events (Gustafsson et al., 2021 ; Kurtessis et al., 2017 ). Drawing from this line of research, the underlying role of POS in how employees respond to external threats from workplace disruptions was examined.

External threats can trigger high levels of fear of uncertainty, which has negative repercussions for individuals’ well-being and ontological insecurity—that is, a person’s sense of “being” in the world (Campbell et al., 2020 ). We believe that POS can manifest itself in the working life of employees in disruptive situations of uncertainty by fostering the employee’s emotional attachment and identification with the organization (Slaughter et al., 2021 ). For instance, a state of uncertainty that is experienced as threatening to the self instills a stronger reliance on emotions (or affective inputs) that are closely linked to the self (Faraji-Rad & Pham, 2017 ). That is, when a threatening situation emerges, there is automatically greater adaptive attention to the self (Campbell et al., 2020 ). Furthermore, a sense of uncertainty also stimulates information-seeking behaviors (Fung et al., 2018 ; Huang & Yang, 2020 ; Kahlor, 2010 ). In this context, organizations can arguably be positioned as a more authentic source for information seeking in the face of a disruptive external threat and, thus, fulfill a key role in shaping affectively driven inputs to ward off the fear of uncertainty. Interestingly, cross-cultural research has suggested that in the case of exposure to external threats, perceived organizational support is more receptive in Eastern cultures, for employees are culturally more likely to see the self as interdependent. Additionally, they are more attuned to organizational support as an identity-related cue (Rockstuhl et al., 2020 ).

The effects of disruptive events and psychological states of uncertainty could be contingent upon the perception of being in control (e.g., Brown & Siegel, 1988 ; Klein & Helweg-Larsen, 2002 ; Thompson et al., 1993 ). The COVID-19 pandemic has provoked extreme uncertainty and substantial fear among people, particularly during lockdowns and other social restrictions (Brodeur et al., 2020 ). As such, it is important to consider the contingent role of internal locus of control on how POS translates into employees’ responses to disruptive situations. Individuals with high perceived control are more likely to maintain an active mindset, triggering more pronounced adaptiveness to organizational efforts for alleviating disruptive situations. In general, it is anticipated that organizations can leverage the role of POS in shaping individuals’ affective inputs (that is, lockdown loneliness under the COVID-19 pandemic), which leads to their subsequent judgments of job insecurity, a particularly important facet of ontological insecurity in deeply unsettling work situations. Henceforth, such causal relationships may be contingent on the perceived locus of control over the threatening nature of the phenomenon (Morgeson et al., 2015 ).

The context for this study entails survey data collected from two waves during the lockdown periods of the COVID-19 pandemic in China. The goal of the study is to unravel the POS effects on employee responses to such disruptive events in the Chinese context. In doing so, we deepen our understanding of POS literature and more specifically enhance our insights into management’s adaptive practices aimed at fostering employees’ social identification in Eastern cultures (Rockstuhl et al., 2020 ). In short, the disruptions and uncertainties that have arisen due to the COVID-19 pandemic offer an excellent field context to illustrate how insights from research on organizational support help to improve our understanding of employees’ job insecurity.

Theoretical background

Perceived organizational support (POS) refers to an employee’s general perception about the organization’s readiness to respond to their socioemotional needs and value their contributions to the organization (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002 ). The concept of POS was developed to explain the development of employee commitment to an organization (Eisenberger et al., 1986 ). To date, a large body of research shows that POS has a considerable impact on a wide range of organizational outcomes, including employees’ increased job satisfaction, productivity, and psychological well-being (Kurtessis et al., 2017 ). A core perspective adopted to explain POS effects is social identity theory (e.g., Ashforth & Mael, 1989 ; Tajfel, 1978 ). According to social identity theory, the key role of POS is in building the self-identification of the employee with the organization (or organizational identification) that matters in developing organizational commitment (Lam et al., 2016 ). Rockstuhl et al. ( 2020 ), drawing on a cross-cultural meta-analysis of POS effects, found that the social identity perspective offers a solid explanation for POS effects in the context of Eastern cultures. In a broad sense, organizational identification refers to an individual’s psychological attachment to an organization (Ashforth & Mael, 1989 ) and mirrors the underlying link or bond that exists between the employee and the organization (Dutton et al., 1994 ). One central assumption seems that when people receive favorable identity-relevant cues from membership in an organization, they are more likely to internalize organizational values that can help them to act in ways that benefit the organization (He & Brown, 2013 ).

The centrality of being well informed about organizational issues and the emphasis on one’s role as an important member in contributing to the organization’s success shape employees’ development of emotional intimacy and feelings of self-worth with the organization. Such emotional attachment translates into increased organizational identification (Sguera et al., 2020 ; Smidts et al., 2001 ). Hence, management communications will signal an organization’s approval, care for, and respect to its employees and offer important cues for employees’ identity formation and sensemaking of POS effects (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002 ; Yue et al., 2021 ). In this regard, employees who perceive their organization as supportive are likely to incorporate organizational membership into their social identity. Perceived support helps to encapsulate attention to relational ties that bind people together (Dutton et al., 1994 ). Additionally, in cultures that promote vertical collectivism, these relationship-based identities are more likely to be salient in explaining POS effects (Rockstuhl et al., 2020 ). Drawing from these studies, this paper intends to finetune the understanding of how POS shapes employees’ sense of job insecurity under disruptive situations.

Research hypotheses

The direct effect of perceived organizational support on job insecurity.

When people’s normal and anticipated lives are disrupted, they experience insecurity, uncertainty, and anxiety (Freedy et al., 1994 ). Disruptions can shake people’s confidence in “the continuity of their self-identity and the constancy of their social and material environment of action” (Giddens, 1991 , p. 92), resulting in ontological insecurity. Giddens ( 1991 , p. 37) describes ontological security as a “person’s fundamental sense of safety in the world and includes a basic trust of other people,” and obtaining this trust is “necessary in order for a person to maintain a sense of psychological well-being and avoid existential anxiety.” The extent to which people experience ontological insecurity is associated with feelings of job insecurity, particularly when the workplace is disrupted in unforeseen ways (Lin et al., 2021 ). Job insecurity in this sense reflects a perceived threat to the continuity and stability of employment as it is currently experienced (Shoss, 2017 ). While the fear of losing one’s job can be imaginative and visualized under external threats (Greenhalgh & Rosenblatt, 1984 ), the perception of job insecurity is not just about financial losses, but also encompasses the emotional and affective aspects of the threat to self-identity in the workplace, particularly in the Asian context (Rockstuhl et al., 2020 ). For this reason, organizations may find themselves in the position to help employees better cope with the negative emotional arousal of job insecurity by reestablishing organizational identification and trust in a world that is perceived as stable and predictable (Gustafsson et al., 2021 ).

POS qualifies as a socioemotional need for affiliation, self-control, and psychological support, which are all valued aspects that contribute to psychological resilience and subjective well-being (Baran et al., 2012 ). In this regard, POS manifests itself as a key communicative function for supportive work conditions and reinforcement of the socioemotional needs of employees (Brown & Roloff, 2015 ; Neves & Eisenberger, 2012 ). This communicative function becomes more critical in times of major organizational changes (Gigliotti et al., 2019 ) or crisis situations (Callison & Zillmann, 2002 ). Extending the communicative function of POS, an organization may foster employees’ sense of security, as manifested by providing emotional comfort, facilitating problem resolution, and reinforcing social attachment (Bowlby, 1988 ; Feeney & Collins, 2015 ). By redirecting individuals’ attention to organizational identification, POS enables employees to make sense of their social environment and their position within it and guides their behavior and evaluations (Ashforth & Mael, 1989 ; Dutton et al., 1994 ). In view of the heightened threats and uncertainty of the COVID-19 outbreak, it is argued here that POS serves as an important social resource for creating a sense of social identity that helps alleviate people’s psychological depletion of cognitive and emotional resources during prolonged lockdowns (e.g., Faraji-Rad & Pham, 2017 ). By fulfilling a restored sense of collective good and organizational identity, POS is likely to reduce employees’ perception of job insecurity in times of external threats. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Perceived organizational support (POS) leads to a decreased level of employees’ sense of job insecurity in times of external threats.

Emotional well-being as a mediating path

Emotional well-being refers to one’s ability to produce positive emotions, moods, thoughts, and feelings and adapt in the face of adversity and disruptive situations (Slaughter et al., 2021 ). It entails emotional states and self-appraisal over external threats and uncertainty. Job insecurity is related to multiple health outcomes, including but not limited to psychological strain and subjective well-being (Campbell et al., 2020 ; Cheng et al., 2012 ; Shoss, 2017 ). When job security is at risk, people tend to experience heightened levels of uncertainty draining their emotional well-being (Campbell et al., 2020 ). Despite these insights, relatively unchartered territory remains the study of how uncertainty-triggered emotions relate to felt job insecurity in times of external threats. In this context, Faraji-Rad and Pham ( 2017 ) noted that uncertainty triggers people’s greater attention to the self-relying on their momentary feelings, moods, and emotions to reaffirm the self-status. This research suggests that feelings of fear and uncertainty increase people’s reliance on affective inputs in making meaningful connections to the self. Interestingly, such reliance on feelings may also improve people’s ability to predict future outcomes (Pham et al., 2012 ). Hence, emotional well-being should be especially valuable in gauging one’s sense of job insecurity under external threats and uncertainty.

Relevant to the external threat of the COVID-19 outbreak, people have experienced global lockdowns and closures of nonessential business as part of efforts by governments to stymie the spread of the virus. These widespread lockdowns have caused a great deal of depression, loss of freedom of movement, social isolation, anxiety, and loneliness, compounded by uncertainty about work in the shape of fears about future job prospects and heightened feelings of job insecurity (Debata et al., 2020 ; Probst et al., 2020 ). In particular, the so-called lockdown loneliness or the situational emotions of anxiety, fear, and social isolation that accompany lockdown experiences (Cable, 2020 ; Luchetti et al., 2020 ) have been at the top of the mental health crisis during periods of pandemic disruption (Brodeur et al., 2020 ; Hamermesh, 2020 ). Henceforth, lockdown loneliness is considered a specific state of emotional well-being and how the indirect relationship between POS and employees’ sense of job insecurity can be explained through this emotional state is examined.

Organizations have an important role to play in offering a supportive role to employees when social isolation and its negative impact on psychological well-being risks spiraling over to the workplace (Bentley et al., 2016 ). Organizations provide access to resources, which help employees cope with external threats and challenges. In the case of the loss of such resources or the threat of losing resources, an enormous strain is placed on coping abilities to deal with challenging and stressful situations (Palmwood & McBride, 2019 ). As a considerable amount of resources is consumed when individuals cope with traumatic events, the impact of resources on psychological well-being in times of a crisis is particularly relevant. With their fundamental socioemotional needs fulfilled, individuals with ample resources are more likely to be able to adapt and cope with the psychological distress caused by disruptive traumatic events, whereas individuals with limited or depleted resources are even more psychologically vulnerable to the adverse consequences of trauma caused by such events. In this context, as threatening as COVID-19 is, it is the availability of resources that determines people’s emotional coping with the uncertainties caused by the pandemic. In a situation such as COVID-19, social support in the form of POS is very relevant to helping employees cope with emotional discomfort by restoring their sense of the self in relation to organizational identification. Based on the above observations, we argue for the salient and impactful role of affective inputs in judgment and behaviors under states of uncertainty (Faraji-Rad & Pham, 2017 ), translating the impact of POS on job insecurity through the mediating role of lockdown loneliness. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Lockdown loneliness mediates the relationship between perceived organizational support (POS) and employees’ sense of job insecurity.

The contingent influence of perceived control

Perceived control is defined as the belief in one’s ability to exert control over situations or events (e.g., Lee et al., 1990 ; Skinner, 1996 ; Spector, 1986 ) and has a rich research tradition. Multiple theories have attempted to identify the underlying processes that explain the emergence of perceived control, as well as the power of the locus of perceived control on human functioning, such as mental health and behavioral actions (e.g., Ajzen, 2002 ; Brown & Siegel, 1988 ; Rotter, 1966 ; Skinner, 1996 ).

Common to these theories is the notion that there is a fundamental psychological need and desire for control over one’s situation and that there are processes (or means) to enact that control (Liu et al., 2012 ). Advanced arguments point to the importance of understanding perceived control as a more generalized and powerful way of thinking about individual-environment dynamics, particularly relevant to coping with adverse situations or negative life events (Hobfoll, 2002 ; Klein & Helweg-Larsen, 2002 ).

Perceived control has instrumental value to assist people in coping with the strain from a traumatic event, such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Hobfoll, 1989 , 2011 ). The coping function of perceived control is pivotal in mitigating the effect of stressful events on health outcomes (e.g., Poon, 2003 ; Schmitz et al., 2000 ). For instance, Schmitz et al. ( 2000 ) found that the relationship between stressors and burnout was stronger among nurses who attributed protection from an aversive event to a less stable external origin (lack of perceived control) in comparison to those who attributed the cause of protection to the self or an internal origin. Similarly, Poon ( 2003 ) noted that perceived control moderates the effect of organizational politics on job stress and the intention to quit. The adverse effects of organizational politics on job stress and turnover intentions only occurred when employees reported low levels of perceived control.

Recognizing the central role of perceived control in mental health, studies have suggested that attributions of negative life events to uncontrollable causes are likely to shape feelings of anxiety, stress, and psychological well-being (Brown & Siegel, 1988 ; Kehner et al., 1993 ). In the case of a traumatic large-scale event, the attribution of protection against its detrimental impact is often a function of the event’s characteristics rather than stable internal characteristics. As it stands, an event becomes severe and threatening to the self when it is perceived as novel, disruptive, and critical (Morgeson et al., 2015 ). Additionally, the same event can be interpreted and responded to very differently by different individuals (Lin et al., 2021 ). Low levels of perceived control may be indicative of resource depletion, causing a negative loss spiral and thus making it more difficult for people to adapt and embrace supportive social conditions (e.g., organizational support). In contrast, individuals who perceive the external threat as temporary and more controllable (i.e., high levels of perceived control) may maintain an active mindset, leading them to be more adaptive to organizational efforts toward alleviating disruptive lockdown loneliness (or improving emotional well-being). Based on the above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Perceived control over an external threat moderates the relationship between perceived organizational support (POS) and lockdown loneliness, such that the relationship is more pronounced when perceived control is high versus low.

Research context

Our research framework was tested in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Two-wave lagged survey data were collected during the periods of pandemic lockdowns across different regions in China. COVID-19 has caused enormous disruptions to the taken-for-granted norms, beliefs, and routines that comprise our experiences of the world in general and the workplace in particular (Brammer et al., 2020 ; De Massis & Rondi, 2020 ; Liu et al., 2020 ; Spicer, 2020 ). Given its magnitude and scale of disruptiveness, COVID-19 represents an opportunity for scholars to develop a more nuanced understanding of managerial actions and implications with regard to threats caused by catastrophic events.

Survey description and procedure

The survey design started soon after the COVID-19 outbreak in China. To mitigate sampling bias, a proportionally stratified probability sampling approach was used. Using the respective numbers of infected COVID-19 cases across different regions of China as of July 29, 2020 (the time when the first-wave survey was conducted), our target population was divided into three strata. The first stratum was Hubei Province (with the epicenter Wuhan city included), where the COVID-19 pandemic was the most severe, reporting 68,135 confirmed COVID-19 cases in the province and representing 77.7% of the 87,680 total cases of infection in China. The Province’s permanent resident population of 2019 was approximately 4.2% of the Chinese population. The second stratum consisted of provinces of moderate severity, including Guangdong, Henan, Zhejiang, Hunan, Anhui, and Heilongjiang. By July 29, 2020, there were a total of 7177 confirmed COVID-19 cases in these provinces, 8.2% of the total cases in China, with each province having approximately 1000 cases or more. The permanent resident population of this stratum in 2019 was approximately 31.5% of the total Chinese population. The third stratum represented all other provinces of the lowest severity. By July 29, 2020, there were a total of 12,368 confirmed COVID-19 cases in this stratum, accounting for 14.1% of the total cases in China. The permanent resident population of this stratum in 2019 was approximately 64.3% of the total Chinese population.

Taking the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases and the population proportions in the above three strata into account, we targeted approximately 20% or 400 observations collected in the first stratum and approximately 40% or 800 observations in the second and third strata. Since the severity of the pandemic varied enormously across these three strata, our sampling method would reasonably ensure that respondents in the survey were better represented across major regions in China. While each stratum was involved in different levels of lockdown restrictions, national protocols were strictly implemented regardless of the location.

Two specialized data service companies (GrowthEase and WJX) in China were commissioned in administering the surveys. A total of 2157 online questionnaires were completed, with a valid sample of 1805 observations. Breaking down the data, 358 (19.8%) respondents were taken from the first stratum, 745 (41.3%) from the second stratum, and 702 (38.9%) from the third stratum, providing a good representation of the target population. Additionally, the data collection procedure had protocols in place to guarantee that all respondents were employed at the time of the lockdown, had experienced the pandemic lockdowns and were employed during the period of disruption.

This study relied on psychometrically robust scales to measure the core constructs. Unless otherwise noted, the response anchors for all measurement items had five-point Likert formats ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Table 1 offers a more detailed description of the scales used.

- Perceived organizational support

A 4-item scale was adapted to measure POS by referring to the research on thriving through adversity and communicative functions of POS (Brown & Roloff, 2015 ; Feeney & Collins, 2015 ). This scale yielded excellent internal consistency (Cronbach α = .858).

Lockdown loneliness

A 5-item scale for lockdown loneliness was adapted based on the scale for measuring loneliness by Hughes et al. ( 2004 ) and Schrempft et al. ( 2019 ). Related to our conceptualization, these measures mostly reflect emotional well-being during the lockdowns. The reliability for this scale was very good (Cronbach α = .880).

- Job insecurity

This variable was adapted from Anderson and Pontusson ( 2007 ) and Carr and Chung ( 2014 ) using a 4-item scale to measure employees’ sense of job insecurity under the COVID-19 lockdown. The multi-item scale demonstrated excellent reliability (Cronbach α = .884).

- Perceived control

Perceived control over the COVID-19 pandemic was measured with a 5-item scale adapted from previous studies (e.g., Frazier et al., 2011 ; Mirowsky & Ross, 1991 ; Newsom et al., 1996 ). The scale reflects people’s beliefs about the controllability of the novel coronavirus, as well as their ability to control threats and uncertainties. This scale yielded excellent reliability (Cronbach’s α = .851).

Control variables

The different regions in our sample implemented different levels of lockdown restrictions. These differences might affect the hypothesized relationships of interest and therefore should be controlled for. The variables included are lockdown status (full restrictions vs. semi restrictions), work status (working from home vs. not working temporarily), family companions, gender, age, levels of education, and income.

Control for common method variance

To minimize potential concerns about common method variance (CMV), attention was paid to the research design and data collection phases, as suggested in the literature. Following the suggestion of Podsakoff et al. ( 2003 ), statistical testing for the presence of CMV was conducted. Harman’s single-factor test, using exploratory factor analysis (EFA), showed that a single factor accounted for 30.21% of the covariance among the measures, below the threshold of 50% (Harman, 1976 ). As an extension of Harman’s single-factor test (e.g., Fuller et al., 2016 ), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to test whether all the variables specified in the study loaded onto one common factor. The fit of the one-factor CFA model (CFI = .444, TLI = .332, χ 2 (65) = 7135.373) was compared with that of our four-factor measurement model (CFI = .984, TLI = .979, χ 2 (59) = 260.408). The four-factor CFA model generated a significantly better fit (ΔCFI = .540, ΔTLI = .647, Δ χ 2 (6) = 6874.965, p < .001), reducing concerns about the potential for CMV (Lattin et al., 2003 ).

In addition, we also applied a CFA marker procedure by Williams et al. ( 2010 ). The method factor is a conceptually unrelated marker variable, namely, a 12-item mindfulness scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .795), developed by Feldman et al. ( 2007 ). According to Williams et al. ( 2010 ), the marker factor loadings are forced to be equal in the Method-C model and are freely estimated in the Method-U model, while in the Method-R model the substantive factor correlations are restricted to values obtained with the Baseline Model. As shown in Table 2 , the latent marker variable effects were significant (Δ χ 2 = 22.049, Δ df = 1, p < .001, Baseline vs. Method-C), and CMV was significantly different for all the indicators (Δ χ 2 = 218.783, Δ df = 12, p < .001, Method-C vs. Method-U). Comparing the Method-U and Method-R models showed that the marker variable did not significantly bias factor correlation estimates (Δ χ 2 = 11.703, Δ df = 6, p > .05, Method-U vs. Method-R), thus providing further evidence for alleviating concerns about CMV.

Analyses and results

Assessment of the measurement model.

Prior to testing the hypothesized framework, the measurement model was assessed in terms of construct reliability and convergent and discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981 ; Hair et al., 2010 ). Construct reliability reflects internal consistency in scale items measured by composite reliability. As shown in Table 1 , all composite reliability scores were acceptable. Convergent validity refers to the extent to which measures of a specific construct “converge” or share a high proportion of variance in common (Hair et al., 2010 ). Consistent with the recommendations in the literature (e.g., Hair et al., 2010 ), factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE) were examined for convergent validity. The results showed that the factor loadings are strongly related to their respective constructs, with standardized loadings all above the .70 threshold (Hair et al., 2010 ). The AVE for each construct varied from .647 to .716 and thus exceeded the .50 threshold (Fornell & Larcker, 1981 ). Overall, these tests offered strong support for the convergent validity of the scales used in this study.

To establish discriminant validity, or the extent to which a construct is truly distinct from other constructs (Hair et al., 2010 ), the amount of variance captured by the construct (AVE) and the shared variance were compared with other constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981 ). In support of discriminant validity, all AVE estimates were greater than the corresponding interconstruct squared correlation estimates. In addition, the measurement model was adequate, CFI = .984, TLI = .979, RMSEA = .043, 90% C.I. of RMSEA = [.038, .049], SRMR = .024, \({{\chi^{2} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\chi^{2} } {df}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {df}}\) = 4.414, p < .001. Finally, the descriptive statistics and correlations between the constructs are displayed in Table 3 .

Structural model evaluation

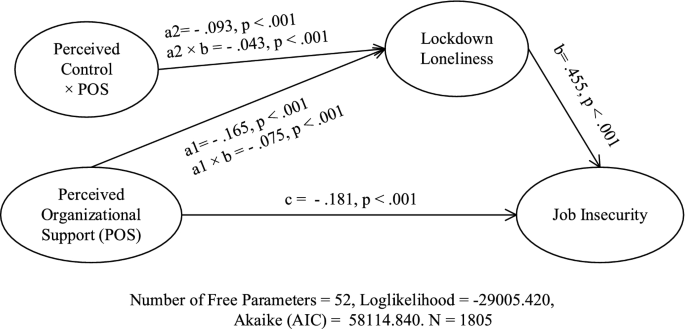

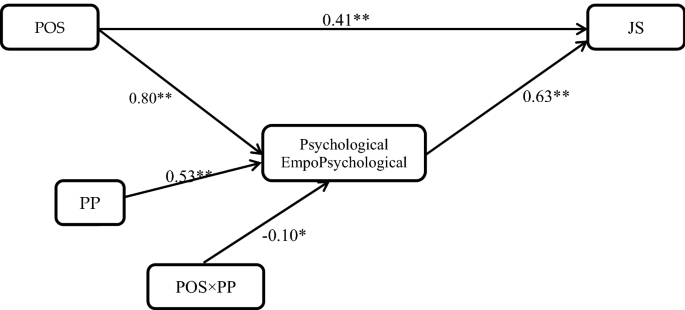

To test the hypotheses, structural equation modeling (SEM) and latent moderated structural equations were conducted (LMS, Klein & Moosbrugger, 2000 ) using Mplus 8.3. We first estimated the mediation-effect-only model, that is, excluding the interaction effect (i.e., POS × Perceived Control), which yielded a satisfactory model fit, CFI = .960, TLI = .953, RMSEA = .045, 90% C.I. of RMSEA = [.042, .049], and SRMR = .054, \({{\chi^{2} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\chi^{2} } {df}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {df}}\) = 4.665, p < .001. Next, we estimated the complete model with the interaction effect included. Adding the interaction significantly improved the model fit (− 2ΔLL = 13.396, Δ df = 1, p < .001) (Gerhard et al., 2015 ). Footnote 1 As shown in Fig. 1 , POS had a significant, negative effect on job insecurity ( c = − .181, p < .001), suggesting that perceived organizational support helps alleviate employees’ sense of job insecurity and thus confirms Hypothesis 1. Moreover, in support of Hypothesis 2, the mediation effect of POS on job insecurity via lockdown loneliness ( a 1 × b = − .075, p < .001) was obtained. POS improves lockdown loneliness ( a 1 = − .165, p < .001), which in turn shapes one’s sense of job insecurity ( b = .455, p < .001).

Structural estimates of research model. Notes a 1 × b is the mediating effect of POS on job insecurity through lockdown loneliness. a 2 × b indicates that the moderation effect is mediated via lockdown loneliness

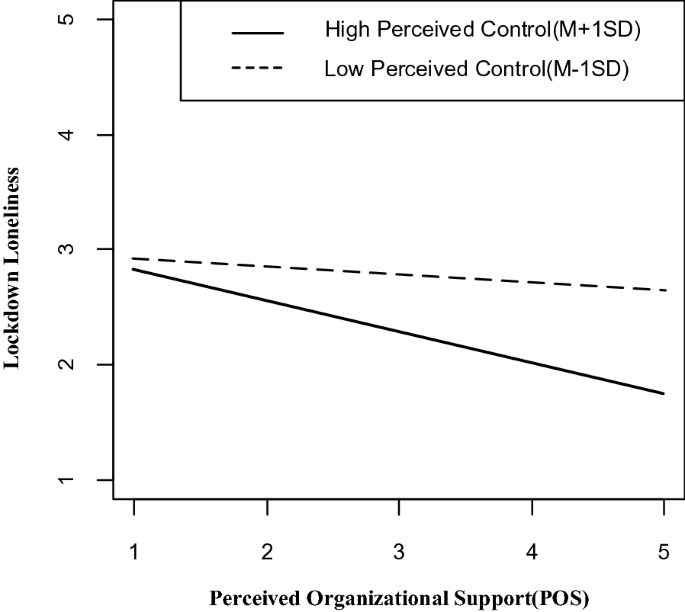

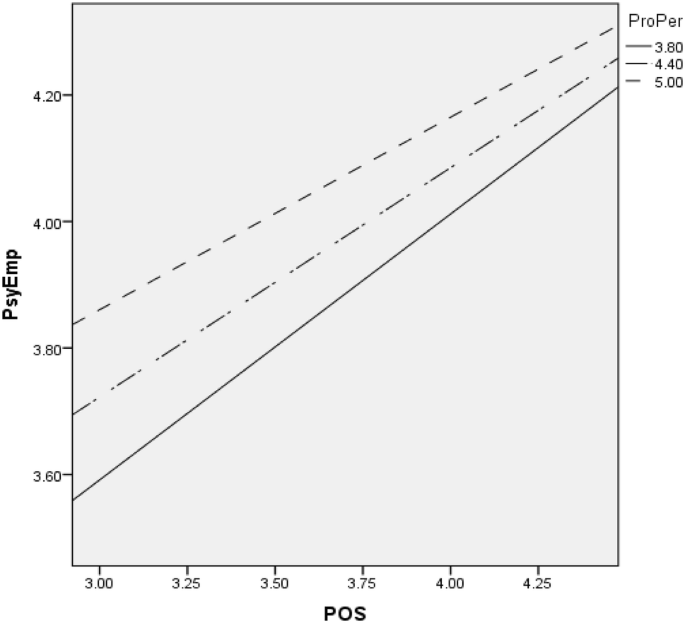

Furthermore, the results also indicated that the interaction between POS and perceived control had a significant, negative effect on lockdown loneliness ( a 2 = − .093, p < .001). In support of Hypothesis 3, the results suggest that the impact of POS on lockdown loneliness was more pronounced as perceived control increased. More interestingly, we also observed a moderated mediation via lockdown loneliness for the perception of job insecurity ( a 2 × b = − .043, p < .001). To further assess the pattern of the moderating effect, we used subgroup analysis. The sample was divided into two groups based on a median split (e.g., DeCoster et al., 2011 ). The low (high) perceived control subgroup comprised respondents below (above) the median. The Wald test of parameter constraints within Mplus indicates that the effects of POS on lockdown loneliness between the low and high perceived control groups were significantly different (− .095 vs. − .314, low vs. high perceived control; \(\chi^{2}\) = 14.859, df = 1, p < .001). For a further understanding of the pattern, Fig. 2 graphically illustrates the moderation effect of POS and perceived control on lockdown loneliness. At low levels of perceived control (1 SD below the standardized mean), the regression line was tilting to the higher right; at high levels of perceived control (1 SD above the standardized mean), the regression line tilted to the lower right.

Graphical illustration of the moderating effects of perceived control

Follow-up robustness test

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, China has continued to implement stringent restrictions and regional lockdowns in highly affected areas. During the second wave of the lockdown period in Xi’an city from December 2021 to January 2022, the second round of data was collected using a similar sampling approach and survey questionnaire as described earlier. GrowthEase, one of the two data service companies used previously, were commissioned to administer the online survey. A total of 1680 questionnaires were completed, with a valid sample of 1460 respondents. All the respondents confirmed that they were living in Xi’an city, experiencing the lockdown, and were employed during the pandemic. Next, these data were used to test the robustness of the original findings.

First, the convergent and discriminant validity of the measurement scales were assessed with the Xi’an dataset. The results of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) showed that the measurement model was adequate, CFI = .987, TLI = .983, RMSEA = .043, 90% C.I. of RMSEA = [.037, .049], SRMR = .026. All items loaded high onto their respective constructs and were statistically significant ( p < .001). The composite reliability of the constructs ranged from .848 to .921, the average variance extracted (AVE) ranged from .653 to .760, and Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .842 to .919.

Next, the LMS method was used to estimate the structural equation model. In line with the previous results, POS had a significant negative effect on lockdown loneliness ( a 1 = − .186, p < .001), lockdown loneliness resulted in a significant positive effect on the perception of job insecurity ( b = .466, p < .001), and the mediation effect of POS on the perception of job insecurity via lockdown loneliness was also significant ( a 1 × b = − .087, p < .001). These findings suggest that both the direct and indirect effects of POS on job insecurity (via lockdown loneliness) remain statistically significant and as impactful as before. However, the interaction between POS and perceived control on lockdown loneliness was not significant ( a 2 = .022, p = .604). Furthermore, no significant mediated moderation effect was detected ( a 2 × b = .010, p = .605). These findings may suggest that the event impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is no longer perceived as novel and critical, as observed in the first wave of data collection.

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused major global challenges for organizations and has impacted their need to learn to adapt rapidly (Carnevale & Hatak, 2020 ; Cooke et al., 2021 ; Horn et al., 2021 ; Li et al., 2020 ). As the event impact made abundantly clear, there is a set of external threats that occur irregularly and unpredictably; these include natural disasters, foreign invasions, civil war, and rapid economic, institutional, and technological changes. External threats are much harder for businesses to anticipate and control for, yet they are often extremely disruptive to people’s lives and can have catastrophic consequences for industries and companies. With this in mind, organization studies should go beyond the contemporary circumstance mindset and help organizations to be better prepared for other disruptive events that may occur in the future. In view of the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and its allied consequences for employees in terms of perceived ontological insecurity and employment uncertainty, the role of perceived organizational support (POS) was examined in managing employees’ sense of job insecurity.

Mainly drawing on social identity theory and supportive findings from research on emotions under psychological states of uncertainty, it is argued that POS as a favorable social identity cue helps to mitigate the fear of threats to the self and, as such, leads to an improved sense of job insecurity. Alternatively, POS may help to foster individuals’ reliance on emotions and other affective inputs in assessing job insecurity under disruptive uncertainty. As such, lockdown loneliness, as a specific manifestation of emotional well-being, is a pivotal mediating mechanism in explaining the impact of POS on job insecurity. As people likely respond to the same external threat to varying degrees and have different beliefs in their ability to exert control over the situation (Lin et al., 2021 ; Morgeson, 2005 ), the variable of perceived control was incorporated into the framework and its moderating influence on the effect of POS on lockdown loneliness was identified. Based on two-wave lagged survey data collected during lockdowns across multiple cities in China, the proposed research framework was largely confirmed, offering support for a range of important theoretical contributions and practical implications.

Theoretical contributions

The current study has several important theoretical contributions. First, the research provides an emerging perspective on organizational adaptive practices to external threats. Specifically, by focusing on event-induced ontological insecurity and employees’ concerns with workplace disruption, the framework offers useful insights into the role of POS in managing organizational responses to employees’ socioemotional needs and reactions in times of threats and challenges. Although POS has been widely studied in the literature, we believe that it is important to further deepen its theoretical relevance in the context of disruptive events. The approach brings the social identity perspective and uncertainty-based emotions to the forefront, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of the psychological underpinnings of POS effects. Additionally, the adopted perspective appears more salient for Eastern cultures, where social identity theory has been found to be a more pivotal theoretical framework to account for POS effects (Rockstuhl et al., 2020 ). In general, this study has paved the way for future work to uncover the interplay surrounding organizational adaptive practices and employees’ reactions to disruptive situations.

Second, the majority of previous research has shown a direct relationship between employees’ job insecurity and their psychological well-being under contemporary circumstances (Shoss, 2017 ). Scholars have shown that job insecurity has detrimental consequences for employees’ mental health and affective commitment to the organization. However, what has been largely overlooked is emotional inputs in shaping employees’ sense of job insecurity. As the disruptiveness of the COVID-19 pandemic continues globally, the focus on addressing people’s emotional well-being has emerged as a top priority (Brodeur et al., 2020 ; Hamermesh, 2020 ). As the adverse impact on psychological well-being caused by the pandemic goes well beyond an organization’s control, the ability of an organization to prepare for, respond, and adapt to disruptive events can help establish ways to foster employees’ psychological resilience. In this regard, this research contributes to the theoretical development of affective inputs in response to event uncertainty in relation to employees’ sense of job insecurity.

Third, we demonstrated that an individual’s perceived control over disruptive events matters when modeling organizational adaptive responses to external threats. People who consider a disruptive event to be external and controllable tend to have an active mindset in searching for event-relevant information (Huang & Yang, 2020 ). Hence, they are likely to be more approachable to organizational support in challenging or threatening times. Relevant to the COVID-19 pandemic, recent research suggests that individuals respond to the same disruptive event to varying degrees with respect to event novelty, disruption, and criticality, resulting in different interpretations of the event, as well as subsequent levels of perceived job insecurity (Lin et al., 2021 ). In brief, accounting for event characteristics in the form of perceived control represents an important integration of previous literature on POS effects and research on emotions under external uncertainty.

Practical implications

Navigating external disruptions, organizations that have embraced digital technologies for virtual collaboration and business practices as the new normal are more likely to be well positioned to sustain the challenges of the future workplace (Papadopoulos et al., 2020 ; Shah et al., 2020 ). The ability to adopt a ‘new’ normal requires organizations to build a stronger and more resilient response mechanism that can help employees adjust to ever-changing and disruptive circumstances while simultaneously caring for their physical and mental well-being (Caligiuri et al., 2020 ; Hu et al., 2020 ). In this context, an important resource at organizations’ disposal is organizational support, with an important communicative function role that extends into building an organizational platform that strengthens physical and mental health among its employees (Carnevale & Hatak, 2020 ). More specifically, the pandemic has offered a great opportunity for organizations to display their human side by offering tools and solutions that help foster emotional well-being and organizational identification. For instance, building a digital workplace signifies organizational support in the shape of the commitment of organizations to connect with their employees and illustrates their concern and care for their employees’ well-being and resilience in disruptive times (Gigauri, 2020 ).

In view of our findings, POS can foster not only social identity with the organization, but also regulate emotional well-being (or lockdown loneliness under the pandemic context) and, as such, offers an important resource for employees to withstand unexpected stressful changes in the external environment. When employees are faced with increasing emotional instability due to unexpected events, it is essential that organizations promote well-being through measures of precaution and provide leadership that encourages aspirations of thriving through adversity (Brown & Roloff, 2015 ; Feeney & Collins, 2015 ). This means that POS should go beyond the traditional approaches of care and social exchange functions. In doing so, the focus should be on cultivating self-regulatory resources and social identity cues. Furthermore, our findings also demonstrate the contingent conditions of perceived control for a better understanding of the effectiveness of organizational support, especially in times of uncertainty. Hence, individuals’ interpretations and reactions to disruptive situations should not be underestimated, especially when external threats are perceived as novel, disruptive, and critical (Lin et al., 2021 ; Morgeson et al., 2015 ).

Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused an abrupt shift from the traditional ‘office workplace’ to working from home during the pandemic, turning remote work into a permanent feature of the new occupational landscape (Carnevale & Hatak, 2020 ; Donthu & Gustafsson, 2020 ; Kaushik & Guleria, 2020 ). Adapting to this new reality, and given our observations, when redesigning or crafting jobs, it is desirable to integrate aspects, such as emotional management and psychological well-being, into the narrative (Kniffin et al., 2021 ). For instance, a transition to telework or other alternative work arrangements will require thoughtful leadership to adapt to the new normal by focusing on the communicative function of POS for building organizational resilience (Brown & Roloff, 2015 ).

Limitations and future research

There are several limitations associated with this study. The first-wave data were collected a few months after the nationwide lockdown in China. Hence, the retrospective nature of the data might suffer from retrieval bias in respondents (Huber & Power, 1985 ). To address this retrospective aspect of the survey, participants were asked to “think aloud” about what they experienced (Kuusela & Paul, 2000 ). In a follow-up robustness test of the model, we collected “experienced” data during the second wave of lockdown. In the follow-up study, the moderating role of perceived control was no longer significant—somehow different from the observations made in the first wave. It appears that risk perceptions changed and collectively evolved as the coronavirus pandemic progressed over time. Taken together, our results suggest that event characteristics and individuals’ interpretations are relevant to theory development for organizational adaptive practices to external threats (Lin et al., 2021 ).

Another concern entails common method variance (CMV), which cannot be completely ruled out due to the nature of the data. However, it should be noted that attempts were undertaken to limit its effects at the research design stage. Additionally, statistical tests were conducted to alleviate the concern of CMV. Despite the limited potential for CMV, future research should attempt to corroborate the causal relationships in our research model by engaging in creative research designs (e.g., lab experiments) to validate the underlying theoretical processes.

Similar to the observation above, another potential drawback is the cross-sectional design of this study, which may have failed to map the effects of within-subject variation in experienced perceived control, lockdown loneliness, and job insecurity. Longitudinal designs could test for such variability and offer more insights into the causality of the relationships between the core variables. Finally, further investigation concerning the generalizability of the findings to other country contexts or unexpected life events should occur. Unlike many other countries, China implemented some of the most stringent and prolonged national COVID-19 lockdowns that shaped the perception and experience of lockdown loneliness. Notwithstanding potential cross-country differences, lockdown loneliness has been widely considered a global phenomenon; therefore, the study’s findings offer an important platform for future research that helps to advance our knowledge about ways to cope with the negative impacts of adverse events on psychological well-being.

The overall goodness-of-fit of our hypothesized model was further tested with other alternative model specifications. Model 1 included direct effects only pertaining POS and perceived control, respectively, to lockdown loneliness and job insecurity. Model 2 included both the direct effects of POS on lockdown loneliness and job insecurity, and the interaction effects of POS × perceived control onto lockdown loneliness and job insecurity. According to Williams and Holahan ( 1994 ), among the parsimony-based fit indices for multiple-indicator models, the AIC value performed the best—the lower AIC indicates a better balance of model fit with parsimony. We found that the overall goodness-of-fit of these alternative models (AIC = 58,202.865 for Model 1; AIC = 58,189.597 for Model 2) were all inferior to that of our hypothesized model (AIC = 58,041.627).

Ajzen, I. (2002). Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32 (4), 665–683.

Article Google Scholar

Anderson, C. J., & Pontusson, J. (2007). Workers, worries and welfare states: Social protection and job insecurity in 15 OECD countries. European Journal of Political Research, 46 (2), 211–235.

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14 (1), 20–39.

Baran, B. E., Shanock, L. R., & Miller, L. R. (2012). Advancing organizational support theory into the twenty-first century world of work. Journal of Business and Psychology, 27 (2), 123–147.

Bentley, T. A., Teo, S. T. T., McLeod, L., Tan, F., Bosua, R., & Gloet, M. (2016). The role of organisational support in teleworker wellbeing: A socio-technical systems approach. Applied Ergonomics, 52 , 207–215.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent–child attachment and healthy human development . Basic Books.

Google Scholar

Brammer, S., Branicki, L., & Linnenluecke, M. K. (2020). COVID-19, societalization, and the future of business in society. Academy of Management Perspectives, 34 (4), 493–507.

Brodeur, A., Clark, A. E., Fleche, S., & Powdthavee, N. (2020). COVID-19, lockdowns and well-being: Evidence from Google Trends. Journal of Public Economics, 193 , 104346.

Brown, J. D., & Siegel, J. M. (1988). Attributions for negative life events and depression: The role of perceived control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54 (2), 316–322.

Brown, L. A., & Roloff, M. E. (2015). Organizational citizenship behavior, organizational communication, and burnout: The buffering role of perceived organizational support and psychological contracts. Communication Quarterly, 63 (4), 384–404.

Butt, A. S. (2021). Supply chains and COVID-19: Impacts, countermeasures and post-COVID-19 era. The International Journal of Logistics Management . https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-02-2021-0114

Cable, N. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic: Urgent needs to support and monitor long-term effects of mental strain on people. American Journal of Public Health, 110 (11), 1595–1596.

Caligiuri, P., De Cieri, H., Minbaeva, D., Verbeke, A., & Zimmermann, A. (2020). International HRM insights for navigating the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for future research and practice. Journal of International Business Studies, 51 (5), 697–713.

Callison, C., & Zillmann, D. (2002). Company affiliation and communicative ability: How perceived organizational ties influence source persuasiveness in a company-negative news environment. Journal of Public Relations Research, 14 (2), 85–102.

Campbell, M. C., Inman, J. J., Kirmani, A., & Price, L. L. (2020). In times of trouble: A framework for understanding consumers’ responses to threats. Journal of Consumer Research, 47 (3), 311–326.

Carnevale, J. B., & Hatak, I. (2020). Employee adjustment and well-being in the era of COVID-19: Implications for human resource management. Journal of Business Research, 116 , 183–187.

Carr, E., & Chung, H. (2014). Employment insecurity and life satisfaction: The moderating influence of labour market policies across Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 24 (4), 383–399.

Cheng, T., Mauno, S., & Lee, C. (2012). The buffering effect of coping strategies in the relationship between job insecurity and employee well-being. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 35 (1), 71–94.

Cooke, F. L., Dickmann, M., & Parry, E. (2021). IJHRM after 30 years: Taking stock in times of COVID-19 and looking towards the future of HR research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32 (1), 1–23.

De Massis, A. V., & Rondi, E. (2020). COVID-19 and the future of family business research. Journal of Management Studies, 57 (8), 1727–1731.

Debata, B., Patnaik, P., & Mishra, A. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic! It’s impact on people, economy, and environment. Journal of Public Affairs, 20 (4), e2372.

DeCoster, J., Gallucci, M., & Iselin, A. M. R. (2011). Best practices for using median splits, artificial categorization, and their continuous alternatives. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology, 2 (2), 197–209.

Donthu, N., & Gustafsson, A. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. Journal of Business Research, 117 , 284–289.

Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39 (2), 239–263.

Dutton, J. E., Roberts, L. M., & Bednar, J. (2010). Pathways for positive identity construction at work: Four types of positive identity and the building of social resources. Academy of Management Review, 35 (2), 265–293.

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71 (3), 500–507.

Faraji-Rad, A., & Pham, M. T. (2017). Uncertainty increases the reliance on affect in decisions. Journal of Consumer Research, 44 (1), 1–21.

Feeney, B. C., & Collins, N. L. (2015). A new look at social support: A theoretical perspective on thriving through relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 19 (2), 113–147.

Feldman, G., Hayes, A., Kumar, S., Greeson, J., & Laurenceau, J. P. (2007). Mindfulness and emotion regulation: The development and initial validation of the cognitive and affective mindfulness scale-revised (CAMS-R). Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 29 (3), 177–190.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18 (3), 382–388.

Frazier, P., Keenan, N., Anders, S., Perera, S., Shallcross, S., & Hintz, S. (2011). Perceived past, present, and future control and adjustment to stressful life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100 (4), 749–765.

Freedy, J. R., Saladin, M. E., Kilpatrick, D. G., Resnick, H. S., & Saunders, B. E. (1994). Understanding acute psychological distress following natural disaster. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 7 (2), 257–273.

Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69 (8), 3192–3198.

Fung, T. K. F., Griffin, R. J., & Dunwoody, S. (2018). Testing links among uncertainty, affect, and attitude toward a health behavior. Science Communication, 40 (1), 33–62.

Gerhard, C., Klein, A. G., Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., Gäde, J., & Brandt, H. (2015). On the performance of likelihood-based difference tests in nonlinear structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 22 (2), 276–287.

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age . Polity Press.

Gigauri, I. (2020). Effects of Covid-19 on human resource management from the perspective of digitalization and work-life-balance. International Journal of Innovative Technologies in Economy, 4 (31), 1–10.

Gigliotti, R., Vardaman, J., Marshall, D. R., & Gonzalez, K. (2019). The role of perceived organizational support in individual change readiness. Journal of Change Management, 19 (2), 86–100.

Greenhalgh, L., & Rosenblatt, Z. (1984). Job insecurity: Toward conceptual clarity. Academy of Management Review, 9 (3), 438–448.

Gustafsson, S., Gillespie, N., Searle, R., Hailey, V. H., & Dietz, G. (2021). Preserving organizational trust during disruption. Organization Studies, 42 (9), 1409–1433.

Haak-Saheem, W. (2020). Talent management in Covid-19 crisis: How Dubai manages and sustains its global talent pool. Asian Business & Management, 19 (3), 298–301.

Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th ed.). Pearson Education.

Hamermesh, D. S. (2020). Life satisfaction, loneliness and togetherness, with an application to Covid-19 lock-downs. Review of Economics of the Household, 18 (4), 983–1000.

Harman, H. H. (1976). Modern factor analysis . University of Chicago Press.

Hartmann, N. N., & Lussier, B. (2020). Managing the sales force through the unexpected exogenous COVID-19 crisis. Industrial Marketing Management, 88 , 101–111.

He, H., & Brown, A. D. (2013). Organizational identity and organizational identification: A review of the literature and suggestions for future research. Group & Organization Management, 38 (1), 3–35.

Henry, M. S., Le Roux, D. B., & Parry, D. A. (2021). Working in a post Covid-19 world: Towards a conceptual framework for distributed work. South African Journal of Business Management, 52 (1), 2155.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44 (3), 513–524.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6 (4), 307–324.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84 (1), 116–122.

Horn, S., Sekiguchi, T., & Weiss, M. (2021). Thrown off track? Adjustments of Asian business to shock events. Asian Business & Management, 20 (4), 435–455.

Hu, J., He, W., & Zhou, K. (2020). The mind, the heart, and the leader in times of crisis: How and when COVID-19-triggered mortality salience relates to state anxiety, job engagement, and prosocial behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105 (11), 1218–1233.

Huang, Y., & Yang, C. (2020). A metacognitive approach to reconsidering risk perceptions and uncertainty: Understand information seeking during COVID-19. Science Communication, 42 (5), 616–642.

Huber, G. P., & Power, D. J. (1985). Retrospective reports of strategic-level managers: Guidelines for increasing their accuracy. Strategic Management Journal, 6 (2), 171–180.

Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging, 26 (6), 655–672.

Kahlor, L. (2010). PRISM: A planned risk information seeking model. Health Communication, 25 (4), 345–356.

Kaushik, M., & Guleria, N. (2020). The impact of pandemic COVID-19 in workplace. European Journal of Business and Management, 12 (15), 1–10.

Kehner, D., Locke, K. D., & Aurain, P. C. (1993). The influence of attributions on the relevance of negative feelings to personal satisfaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 19 (1), 21–29.

Klein, A., & Moosbrugger, H. (2000). Maximum likelihood estimation of latent interaction effects with the LMS method. Psychometrika, 65 (4), 457–474.

Klein, C. T. F., & Helweg-Larsen, M. (2002). Perceived control and the optimistic bias: A meta-analytic review. Psychology & Health, 17 (4), 437–446.

Kniffin, K. M., Narayanan, J., Anseel, F., Antonakis, J., Ashford, S. P., Bakker, A. B., Bamberger, P., Bapuji, H., Bhave, D. P., Choi, V. K., Creary, S. J., Demerouti, E., Flynn, F. J., Gelfand, M. J., Greer, L. L., Johns, G., Kesebir, S., Klein, P. G., Lee, S. Y., ... Van Vugt, M. (2021). COVID-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. American Psychologist, 76 , 63–77.

Kurtessis, J. N., Eisenberger, R., Ford, M. T., Buffardi, L. C., Stewart, K. A., & Adis, C. S. (2017). Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. Journal of Management, 43 (6), 1854–1884.

Kuusela, H., & Paul, P. (2000). A comparison of concurrent and retrospective verbal protocol analysis. American Journal of Psychology, 113 (3), 387–404.

Lam, L. W., Liu, Y., & Loi, R. (2016). Looking intra-organizationally for identity cues: Whether perceived organizational support shapes employees’ organizational identification. Human Relations, 69 (2), 345–367.

Lattin, J., Carroll, J., & Green, P. (2003). Analyzing multivariate data . Brooks/Cole.

Lee, C., Ashford, S. J., & Bobko, P. (1990). Interactive effects of “Type A” behavior and perceived control on worker performance, job satisfaction, and somatic complaints. Academy of Management Journal, 33 (4), 870–881.

Li, J., Ghosh, R., & Nachmias, S. (2020). In a time of COVID-19 pandemic, stay healthy, connected, productive, and learning: Words from the editorial team of HRDI. Human Resource Development International, 23 (3), 199–207.

Lin, W., Shao, Y., Li, G., Guo, Y., & Zhan, X. (2021). The psychological implications of COVID-19 on employee job insecurity and its consequences: The mitigating role of organization adaptive practices. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106 , 317–329.

Liu, J., Hong, C., & Yook, B. (2022). CEO as “chief crisis officer” under COVID-19: A content analysis of CEO open letters using structural topic modeling. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 16 (3), 444–468.

Liu, J., Wang, H., Hui, C., & Lee, C. (2012). Psychological ownership: How having control matters. Journal of Management Studies, 49 (5), 869–895.

Liu, Y., Lee, J. M., & Lee, C. (2020). The challenges and opportunities of a global health crisis: The management and business implications of COVID-19 from an Asian perspective. Asian Business & Management, 19 (3), 277–297.

Luchetti, M., Lee, J. H., Aschwanden, D., Sesker, A., Strickhouser, J. E., Terracciano, A., & Sutin, A. R. (2020). The trajectory of loneliness in response to COVID-19. American Psychologist, 75 , 897–908.

Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (1991). Eliminating defense and agreement bias from measures of the sense of control: A 2 × 2 index. Social Psychology Quarterly, 54 (2), 127–145.

Morgeson, F. P. (2005). The external leadership of self-managing teams: Intervening in the context of novel and disruptive events. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90 , 497–508.

Morgeson, F. P., Mitchell, T. R., & Liu, D. (2015). Event system theory: An event-oriented approach to the organizational sciences. Academy of Management Review, 40 (4), 515–537.

Neves, P., & Eisenberger, R. (2012). Management communication and employee performance: The contribution of perceived organizational support. Human Performance, 25 (5), 452–464.

Newsom, J. T., Knapp, J. E., & Schulz, R. (1996). Longitudinal analysis of specific domains of internal control and depressive symptoms in patients with recurrent cancer. Health Psychology, 15 , 323–331.

Oehmen, J., Locatelli, G., Wied, M., & Willumsen, P. (2020). Risk, uncertainty, ignorance and myopia: Their managerial implications for B2B firms. Industrial Marketing Management, 88 , 330–338.

Palmwood, E. N., & McBride, C. A. (2019). Challenge vs. threat: The effect of appraisal type on resource depletion. Current Psychology, 38 (6), 1522–1529.

Papadopoulos, T., Baltas, K. N., & Balta, M. E. (2020). The use of digital technologies by small and medium enterprises during COVID-19: Implications for theory and practice. International Journal of Information Management, 55 , 102192.

Pham, M. T., Lee, L., & Stephen, A. T. (2012). Feeling the future: The emotional oracle effect. Journal of Consumer Research, 39 (3), 461–477.

Podsakoff, N. P., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88 (5), 879–903.

Poon, J. M. L. (2003). Moderating effect of perceived control on perceptions of organizational politics outcomes. International Journal of Organization Theory & Behavior, 7 (1), 22–40.

Probst, T. M., Lee, H. J., & Bazzoli, A. (2020). Economic stressors and the enactment of CDC-recommended COVID-19 prevention behaviors: The impact of state-level context. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105 , 1397–1407.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87 , 698–714.

Rockstuhl, T., Eisenberger, R., Shore, L. M., Kurtessis, J. N., Ford, M. T., Buffardi, L. C., & Mesdaghinia, S. (2020). Perceived organizational support (POS) across 54 nations: A cross-cultural meta-analysis of POS effects. Journal of International Business Studies, 51 (6), 933–962.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80 , 1–28.

Schmitz, N., Neumann, W., & Oppermann, R. (2000). Stress, burnout and locus of control in German nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 37 (2), 95–99.

Schrempft, S., Jackowska, M., Hamer, M., & Steptoe, A. (2019). Associations between social isolation, loneliness, and objective physical activity in older men and women. BMC Public Health, 19 (1), 74.

Sguera, F., Bagozzi, R. P., Huy, Q. N., Boss, R. W., & Boss, D. S. (2020). What we share is who we are and what we do: How emotional intimacy shapes organizational identification and collaborative behaviors. Applied Psychology, 69 (3), 854–880.

Shah, S. G. S., Nogueras, D., Van Woerden, H. C., & Kiparoglou, V. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic: A pandemic of lockdown loneliness and the role of digital technology. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22 (11), e22287.

Shoss, M. K. (2017). Job insecurity: An integrative review and agenda for future research. Journal of Management, 43 (6), 1911–1939.

Skinner, E. A. (1996). A guide to constructs of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71 , 549–570.

Slaughter, J. E., Gabriel, A. S., Ganster, M. L., Vaziri, H., & MacGowan, R. L. (2021). Getting worse or getting better? Understanding the antecedents and consequences of emotion profile transitions during COVID-19-induced organizational crisis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106 , 1118–1136.

Smidts, A., Pruyn, A. T. H., & Van Riel, C. B. M. (2001). The impact of employee communication and perceived external prestige on organizational identification. Academy of Management Journal, 44 (5), 1051–1062.

Spector, P. E. (1986). Perceived control by employees: A meta-analysis of studies concerning autonomy and participation at work. Human Relations, 39 (11), 1005–1016.

Spicer, A. (2020). Organizational culture and COVID-19. Journal of Management Studies, 57 (8), 1737–1740.

Tajfel, H. (1978). The achievement of inter-group differentiation. In H. Tajfel (Ed.), Differentiation between social groups (pp. 77–100). Academic Press.

Thompson, S. C., Sobolew-Shubin, A., Galbraith, M. E., Schwankovsky, L., & Cruzen, D. (1993). Maintaining perceptions of control: Finding perceived control in low-control circumstances. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64 , 293–304.

Tuan, L. T. (2022). Leader crisis communication and salesperson resilience in face of the COVID-19: The roles of positive stress mindset, core beliefs challenge, and family strain. Industrial Marketing Management, 102 , 488–502.

Williams, L. J., Hartman, N., & Cavazotte, F. (2010). Method variance and marker variables: A review and comprehensive CFA marker technique. Organizational Research Methods, 13 (3), 477–514.

Williams, L. J., & Holahan, P. J. (1994). Parsimony-based fit indices for multiple-indicator models: Do they work? Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 1 (2), 161–189.

Yue, C. A., Men, L. R., & Ferguson, M. A. (2021). Examining the effects of internal communication and emotional culture on employees’ organizational identification. International Journal of Business Communication, 58 (2), 169–195.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Editor-in-Chief and the reviewers for their insights and guidance in helping us improve the quality of the paper. The assistance provided by Lin Huang and Wenting Xiao of WJX and Hui Liao, Wei Wei, and Jiehao Wu of GrowthEase was greatly appreciated. We are also grateful to the assistance in data analysis provided by Professor Mengcheng Wang of Guangzhou University.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics and Management, Yuanpei College, Shaoxing University, 2799 Qunxian Middle Road, Shaoxing, 312000, Zhejiang, China

Luyang Zhou & Hong Tao

School of Business, Shaoxing University, 900 Chengnan Road, Shaoxing, 312000, Zhejiang, China

Luyang Zhou, Shengxiao Li & Hong Tao

Department of Marketing, International Business, and Strategy, Goodman School of Business, Brock University, 1812 Sir Isaac Brock Way, St. Catharines, ON, L2S 3A1, Canada

Lianxi Zhou

Department of Organizational Behavior, Human Resource Management, Entrepreneurship, and Ethics, Goodman School of Business, Brock University, 1812 Sir Isaac Brock Way, St. Catharines, ON, L2S 3A1, Canada

Dave Bouckenooghe

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hong Tao .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Zhou, L., Li, S., Zhou, L. et al. The effects of perceived organizational support on employees’ sense of job insecurity in times of external threats: an empirical investigation under lockdown conditions in China. Asian Bus Manage 22 , 1567–1591 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-023-00219-4

Download citation

Received : 25 August 2021

Accepted : 06 March 2023

Published : 24 March 2023

Issue Date : September 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-023-00219-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- External threats

- Uncertainty

- Emotional well-being

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 25 June 2020

Perceived organizational support and job satisfaction: a moderated mediation model of proactive personality and psychological empowerment

- Annum Tariq Maan 1 ,

- Ghulam Abid 1 ,

- Tahira Hassan Butt 1 ,

- Fouzia Ashfaq 2 &

- Saira Ahmed 3

Future Business Journal volume 6 , Article number: 21 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

42k Accesses

66 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

Drawing on social exchange theory, the purpose of this study is to examine the mediating role of psychological empowerment and moderating role of proactive personality in the relationship between POS and job satisfaction. The data were collected from 936 employees working in various manufacturing and service sectors by using self-report survey questionnaires by employing time-lagged cross-sectional study design. The study findings demonstrate that POS positively influenced psychological empowerment and job satisfaction. Moreover, it is also revealed that the relationship between POS and job satisfaction is weaker when employees’ proactive personality is higher rather than lower. The findings of the current study pose a framework for organizational representatives of both service and manufacturing industries to strengthen individual psychological empowerment and job satisfaction by offering organizational support to those individuals who are less proactive.

Introduction

A long-lasting employment bond comprises positive social exchange approaches in employee–employer relationship whereupon the needs of both parties are addressed [ 40 ]. In the exchange relationship, the employer is worried about the employees’ devotion, engagement and trustworthiness toward them, while employees are conscious about whether their employer is keeping their promises by caring their well-being [ 48 , 61 ]. The theory of organizational support and construct of perceived organizational support (POS) was developed by Eisenberger and his research fellows in [ 26 , 27 ] using social exchange theory [ 15 , 37 , 40 ]. POS is defined as the perception of employees about the degree to which their contributions at organizations are valued, which implies that their associated well-being is given full consideration [ 5 , 26 , 61 ]. The organizational support theory states that individuals form POS, a universal faith that their employer has an advantageous or a disadvantageous inclination toward them [ 40 , 61 ]. Literature also confirms that individuals’ POS helps boost their obligations toward organization in order to reciprocate favorably. Furthermore, they also want to satisfy their socioemotional needs and incorporate organizational affiliation into their social identity [ 21 , 29 ]. In addition, extant literature has shown that individuals’ POS enhances both in-role performance such as goal attainment and extra-role performance such as helping and supportive behavior toward coworkers [ 29 ].

By utilizing social exchange theory as its grounding, researchers have begun to study POS in interpersonal connections with organizations and recognized it as a vital ingredient in subordinate–manager relations [ 65 ]. Meta-analysis conducted by Rhoades and Eisenberger [ 61 ] revealed the favorable treatments such as rewards from the organization, beneficial working conditions and fairness received by employees are directly linked to POS. Moreover, POS promotes auspicious outcomes such as high job satisfaction, lower turnover, enhanced dedication, positive emotions and better performance [ 77 ]. Multi-foci methods to social exchange have highlighted the significance of many sources of support, according to which individuals develop distinct give-and-take relationships with different organizational objectives [ 51 ]. The positive association of POS with job satisfaction, performance, organizational commitment and turnover intention has gained attention in number of employee–organization-related studies [ 30 , 74 ]. Similarly, the outcomes that are relevant to organizational support are job satisfaction, innovative work behavior, learning goal orientation, core self-evaluations and organizational commitment [ 1 , 59 , 71 , 74 , 78 ]. Furthermore, the literature reveals that organizations achieve favorable outcomes if workers feel superior treatment within the organization [ 74 ].