Chapter 11. Interviewing

Introduction.

Interviewing people is at the heart of qualitative research. It is not merely a way to collect data but an intrinsically rewarding activity—an interaction between two people that holds the potential for greater understanding and interpersonal development. Unlike many of our daily interactions with others that are fairly shallow and mundane, sitting down with a person for an hour or two and really listening to what they have to say is a profound and deep enterprise, one that can provide not only “data” for you, the interviewer, but also self-understanding and a feeling of being heard for the interviewee. I always approach interviewing with a deep appreciation for the opportunity it gives me to understand how other people experience the world. That said, there is not one kind of interview but many, and some of these are shallower than others. This chapter will provide you with an overview of interview techniques but with a special focus on the in-depth semistructured interview guide approach, which is the approach most widely used in social science research.

An interview can be variously defined as “a conversation with a purpose” ( Lune and Berg 2018 ) and an attempt to understand the world from the point of view of the person being interviewed: “to unfold the meaning of peoples’ experiences, to uncover their lived world prior to scientific explanations” ( Kvale 2007 ). It is a form of active listening in which the interviewer steers the conversation to subjects and topics of interest to their research but also manages to leave enough space for those interviewed to say surprising things. Achieving that balance is a tricky thing, which is why most practitioners believe interviewing is both an art and a science. In my experience as a teacher, there are some students who are “natural” interviewers (often they are introverts), but anyone can learn to conduct interviews, and everyone, even those of us who have been doing this for years, can improve their interviewing skills. This might be a good time to highlight the fact that the interview is a product between interviewer and interviewee and that this product is only as good as the rapport established between the two participants. Active listening is the key to establishing this necessary rapport.

Patton ( 2002 ) makes the argument that we use interviews because there are certain things that are not observable. In particular, “we cannot observe feelings, thoughts, and intentions. We cannot observe behaviors that took place at some previous point in time. We cannot observe situations that preclude the presence of an observer. We cannot observe how people have organized the world and the meanings they attach to what goes on in the world. We have to ask people questions about those things” ( 341 ).

Types of Interviews

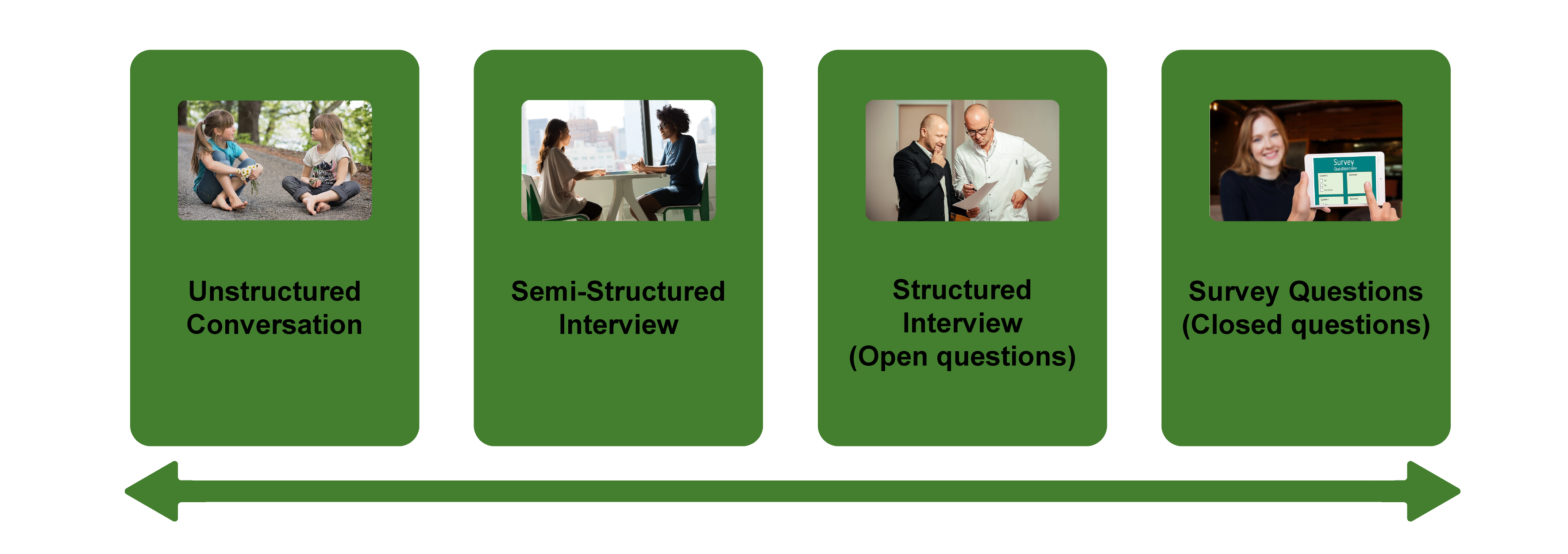

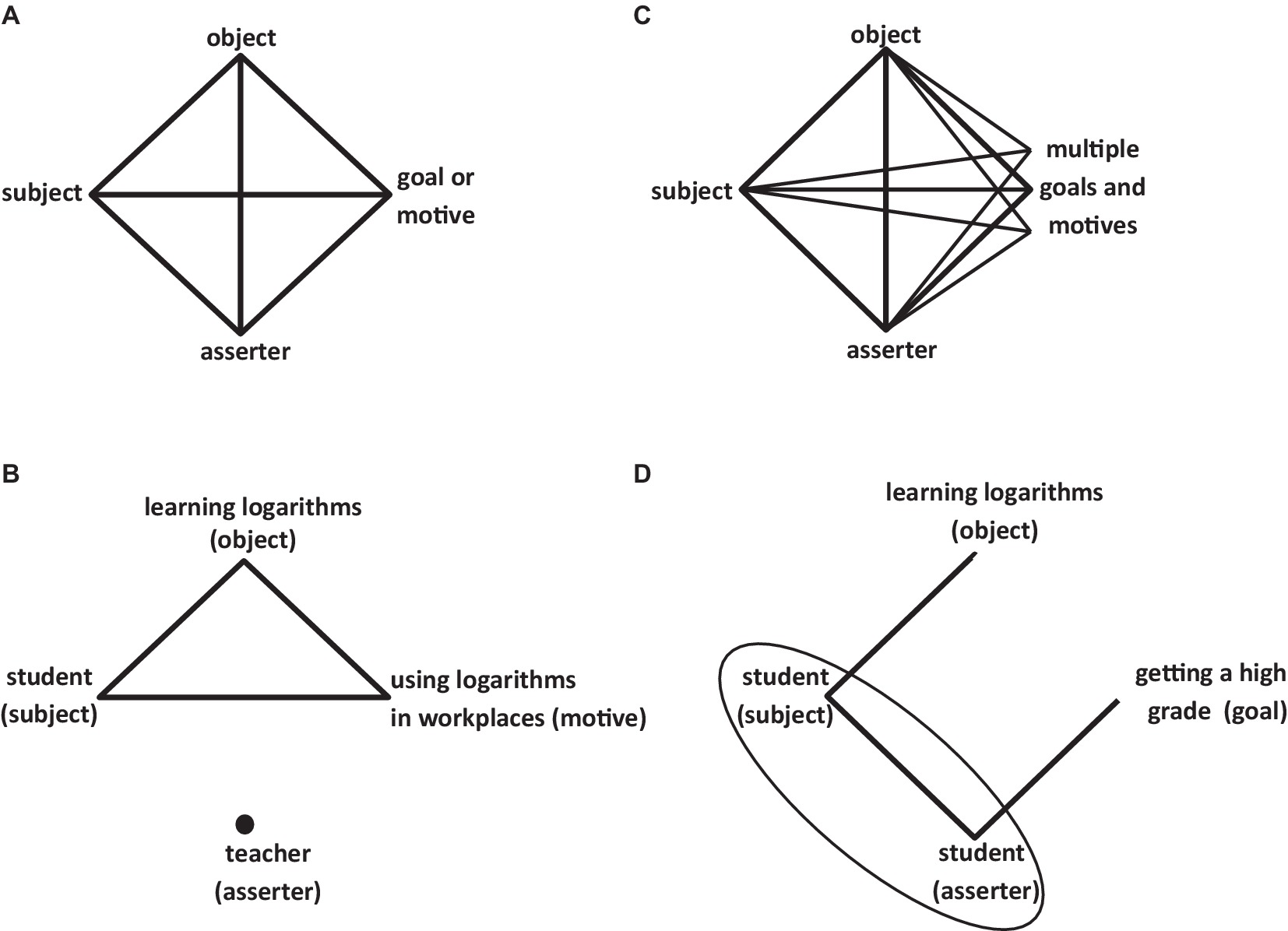

There are several distinct types of interviews. Imagine a continuum (figure 11.1). On one side are unstructured conversations—the kind you have with your friends. No one is in control of those conversations, and what you talk about is often random—whatever pops into your head. There is no secret, underlying purpose to your talking—if anything, the purpose is to talk to and engage with each other, and the words you use and the things you talk about are a little beside the point. An unstructured interview is a little like this informal conversation, except that one of the parties to the conversation (you, the researcher) does have an underlying purpose, and that is to understand the other person. You are not friends speaking for no purpose, but it might feel just as unstructured to the “interviewee” in this scenario. That is one side of the continuum. On the other side are fully structured and standardized survey-type questions asked face-to-face. Here it is very clear who is asking the questions and who is answering them. This doesn’t feel like a conversation at all! A lot of people new to interviewing have this ( erroneously !) in mind when they think about interviews as data collection. Somewhere in the middle of these two extreme cases is the “ semistructured” interview , in which the researcher uses an “interview guide” to gently move the conversation to certain topics and issues. This is the primary form of interviewing for qualitative social scientists and will be what I refer to as interviewing for the rest of this chapter, unless otherwise specified.

Informal (unstructured conversations). This is the most “open-ended” approach to interviewing. It is particularly useful in conjunction with observational methods (see chapters 13 and 14). There are no predetermined questions. Each interview will be different. Imagine you are researching the Oregon Country Fair, an annual event in Veneta, Oregon, that includes live music, artisan craft booths, face painting, and a lot of people walking through forest paths. It’s unlikely that you will be able to get a person to sit down with you and talk intensely about a set of questions for an hour and a half. But you might be able to sidle up to several people and engage with them about their experiences at the fair. You might have a general interest in what attracts people to these events, so you could start a conversation by asking strangers why they are here or why they come back every year. That’s it. Then you have a conversation that may lead you anywhere. Maybe one person tells a long story about how their parents brought them here when they were a kid. A second person talks about how this is better than Burning Man. A third person shares their favorite traveling band. And yet another enthuses about the public library in the woods. During your conversations, you also talk about a lot of other things—the weather, the utilikilts for sale, the fact that a favorite food booth has disappeared. It’s all good. You may not be able to record these conversations. Instead, you might jot down notes on the spot and then, when you have the time, write down as much as you can remember about the conversations in long fieldnotes. Later, you will have to sit down with these fieldnotes and try to make sense of all the information (see chapters 18 and 19).

Interview guide ( semistructured interview ). This is the primary type employed by social science qualitative researchers. The researcher creates an “interview guide” in advance, which she uses in every interview. In theory, every person interviewed is asked the same questions. In practice, every person interviewed is asked mostly the same topics but not always the same questions, as the whole point of a “guide” is that it guides the direction of the conversation but does not command it. The guide is typically between five and ten questions or question areas, sometimes with suggested follow-ups or prompts . For example, one question might be “What was it like growing up in Eastern Oregon?” with prompts such as “Did you live in a rural area? What kind of high school did you attend?” to help the conversation develop. These interviews generally take place in a quiet place (not a busy walkway during a festival) and are recorded. The recordings are transcribed, and those transcriptions then become the “data” that is analyzed (see chapters 18 and 19). The conventional length of one of these types of interviews is between one hour and two hours, optimally ninety minutes. Less than one hour doesn’t allow for much development of questions and thoughts, and two hours (or more) is a lot of time to ask someone to sit still and answer questions. If you have a lot of ground to cover, and the person is willing, I highly recommend two separate interview sessions, with the second session being slightly shorter than the first (e.g., ninety minutes the first day, sixty minutes the second). There are lots of good reasons for this, but the most compelling one is that this allows you to listen to the first day’s recording and catch anything interesting you might have missed in the moment and so develop follow-up questions that can probe further. This also allows the person being interviewed to have some time to think about the issues raised in the interview and go a little deeper with their answers.

Standardized questionnaire with open responses ( structured interview ). This is the type of interview a lot of people have in mind when they hear “interview”: a researcher comes to your door with a clipboard and proceeds to ask you a series of questions. These questions are all the same whoever answers the door; they are “standardized.” Both the wording and the exact order are important, as people’s responses may vary depending on how and when a question is asked. These are qualitative only in that the questions allow for “open-ended responses”: people can say whatever they want rather than select from a predetermined menu of responses. For example, a survey I collaborated on included this open-ended response question: “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?” Some of the answers were simply one word long (e.g., “debt”), and others were long statements with stories and personal anecdotes. It is possible to be surprised by the responses. Although it’s a stretch to call this kind of questioning a conversation, it does allow the person answering the question some degree of freedom in how they answer.

Survey questionnaire with closed responses (not an interview!). Standardized survey questions with specific answer options (e.g., closed responses) are not really interviews at all, and they do not generate qualitative data. For example, if we included five options for the question “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?”—(1) debt, (2) social networks, (3) alienation, (4) family doesn’t understand, (5) type of grad program—we leave no room for surprises at all. Instead, we would most likely look at patterns around these responses, thinking quantitatively rather than qualitatively (e.g., using regression analysis techniques, we might find that working-class sociologists were twice as likely to bring up alienation). It can sometimes be confusing for new students because the very same survey can include both closed-ended and open-ended questions. The key is to think about how these will be analyzed and to what level surprises are possible. If your plan is to turn all responses into a number and make predictions about correlations and relationships, you are no longer conducting qualitative research. This is true even if you are conducting this survey face-to-face with a real live human. Closed-response questions are not conversations of any kind, purposeful or not.

In summary, the semistructured interview guide approach is the predominant form of interviewing for social science qualitative researchers because it allows a high degree of freedom of responses from those interviewed (thus allowing for novel discoveries) while still maintaining some connection to a research question area or topic of interest. The rest of the chapter assumes the employment of this form.

Creating an Interview Guide

Your interview guide is the instrument used to bridge your research question(s) and what the people you are interviewing want to tell you. Unlike a standardized questionnaire, the questions actually asked do not need to be exactly what you have written down in your guide. The guide is meant to create space for those you are interviewing to talk about the phenomenon of interest, but sometimes you are not even sure what that phenomenon is until you start asking questions. A priority in creating an interview guide is to ensure it offers space. One of the worst mistakes is to create questions that are so specific that the person answering them will not stray. Relatedly, questions that sound “academic” will shut down a lot of respondents. A good interview guide invites respondents to talk about what is important to them, not feel like they are performing or being evaluated by you.

Good interview questions should not sound like your “research question” at all. For example, let’s say your research question is “How do patriarchal assumptions influence men’s understanding of climate change and responses to climate change?” It would be worse than unhelpful to ask a respondent, “How do your assumptions about the role of men affect your understanding of climate change?” You need to unpack this into manageable nuggets that pull your respondent into the area of interest without leading him anywhere. You could start by asking him what he thinks about climate change in general. Or, even better, whether he has any concerns about heatwaves or increased tornadoes or polar icecaps melting. Once he starts talking about that, you can ask follow-up questions that bring in issues around gendered roles, perhaps asking if he is married (to a woman) and whether his wife shares his thoughts and, if not, how they negotiate that difference. The fact is, you won’t really know the right questions to ask until he starts talking.

There are several distinct types of questions that can be used in your interview guide, either as main questions or as follow-up probes. If you remember that the point is to leave space for the respondent, you will craft a much more effective interview guide! You will also want to think about the place of time in both the questions themselves (past, present, future orientations) and the sequencing of the questions.

Researcher Note

Suggestion : As you read the next three sections (types of questions, temporality, question sequence), have in mind a particular research question, and try to draft questions and sequence them in a way that opens space for a discussion that helps you answer your research question.

Type of Questions

Experience and behavior questions ask about what a respondent does regularly (their behavior) or has done (their experience). These are relatively easy questions for people to answer because they appear more “factual” and less subjective. This makes them good opening questions. For the study on climate change above, you might ask, “Have you ever experienced an unusual weather event? What happened?” Or “You said you work outside? What is a typical summer workday like for you? How do you protect yourself from the heat?”

Opinion and values questions , in contrast, ask questions that get inside the minds of those you are interviewing. “Do you think climate change is real? Who or what is responsible for it?” are two such questions. Note that you don’t have to literally ask, “What is your opinion of X?” but you can find a way to ask the specific question relevant to the conversation you are having. These questions are a bit trickier to ask because the answers you get may depend in part on how your respondent perceives you and whether they want to please you or not. We’ve talked a fair amount about being reflective. Here is another place where this comes into play. You need to be aware of the effect your presence might have on the answers you are receiving and adjust accordingly. If you are a woman who is perceived as liberal asking a man who identifies as conservative about climate change, there is a lot of subtext that can be going on in the interview. There is no one right way to resolve this, but you must at least be aware of it.

Feeling questions are questions that ask respondents to draw on their emotional responses. It’s pretty common for academic researchers to forget that we have bodies and emotions, but people’s understandings of the world often operate at this affective level, sometimes unconsciously or barely consciously. It is a good idea to include questions that leave space for respondents to remember, imagine, or relive emotional responses to particular phenomena. “What was it like when you heard your cousin’s house burned down in that wildfire?” doesn’t explicitly use any emotion words, but it allows your respondent to remember what was probably a pretty emotional day. And if they respond emotionally neutral, that is pretty interesting data too. Note that asking someone “How do you feel about X” is not always going to evoke an emotional response, as they might simply turn around and respond with “I think that…” It is better to craft a question that actually pushes the respondent into the affective category. This might be a specific follow-up to an experience and behavior question —for example, “You just told me about your daily routine during the summer heat. Do you worry it is going to get worse?” or “Have you ever been afraid it will be too hot to get your work accomplished?”

Knowledge questions ask respondents what they actually know about something factual. We have to be careful when we ask these types of questions so that respondents do not feel like we are evaluating them (which would shut them down), but, for example, it is helpful to know when you are having a conversation about climate change that your respondent does in fact know that unusual weather events have increased and that these have been attributed to climate change! Asking these questions can set the stage for deeper questions and can ensure that the conversation makes the same kind of sense to both participants. For example, a conversation about political polarization can be put back on track once you realize that the respondent doesn’t really have a clear understanding that there are two parties in the US. Instead of asking a series of questions about Republicans and Democrats, you might shift your questions to talk more generally about political disagreements (e.g., “people against abortion”). And sometimes what you do want to know is the level of knowledge about a particular program or event (e.g., “Are you aware you can discharge your student loans through the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program?”).

Sensory questions call on all senses of the respondent to capture deeper responses. These are particularly helpful in sparking memory. “Think back to your childhood in Eastern Oregon. Describe the smells, the sounds…” Or you could use these questions to help a person access the full experience of a setting they customarily inhabit: “When you walk through the doors to your office building, what do you see? Hear? Smell?” As with feeling questions , these questions often supplement experience and behavior questions . They are another way of allowing your respondent to report fully and deeply rather than remain on the surface.

Creative questions employ illustrative examples, suggested scenarios, or simulations to get respondents to think more deeply about an issue, topic, or experience. There are many options here. In The Trouble with Passion , Erin Cech ( 2021 ) provides a scenario in which “Joe” is trying to decide whether to stay at his decent but boring computer job or follow his passion by opening a restaurant. She asks respondents, “What should Joe do?” Their answers illuminate the attraction of “passion” in job selection. In my own work, I have used a news story about an upwardly mobile young man who no longer has time to see his mother and sisters to probe respondents’ feelings about the costs of social mobility. Jessi Streib and Betsy Leondar-Wright have used single-page cartoon “scenes” to elicit evaluations of potential racial discrimination, sexual harassment, and classism. Barbara Sutton ( 2010 ) has employed lists of words (“strong,” “mother,” “victim”) on notecards she fans out and asks her female respondents to select and discuss.

Background/Demographic Questions

You most definitely will want to know more about the person you are interviewing in terms of conventional demographic information, such as age, race, gender identity, occupation, and educational attainment. These are not questions that normally open up inquiry. [1] For this reason, my practice has been to include a separate “demographic questionnaire” sheet that I ask each respondent to fill out at the conclusion of the interview. Only include those aspects that are relevant to your study. For example, if you are not exploring religion or religious affiliation, do not include questions about a person’s religion on the demographic sheet. See the example provided at the end of this chapter.

Temporality

Any type of question can have a past, present, or future orientation. For example, if you are asking a behavior question about workplace routine, you might ask the respondent to talk about past work, present work, and ideal (future) work. Similarly, if you want to understand how people cope with natural disasters, you might ask your respondent how they felt then during the wildfire and now in retrospect and whether and to what extent they have concerns for future wildfire disasters. It’s a relatively simple suggestion—don’t forget to ask about past, present, and future—but it can have a big impact on the quality of the responses you receive.

Question Sequence

Having a list of good questions or good question areas is not enough to make a good interview guide. You will want to pay attention to the order in which you ask your questions. Even though any one respondent can derail this order (perhaps by jumping to answer a question you haven’t yet asked), a good advance plan is always helpful. When thinking about sequence, remember that your goal is to get your respondent to open up to you and to say things that might surprise you. To establish rapport, it is best to start with nonthreatening questions. Asking about the present is often the safest place to begin, followed by the past (they have to know you a little bit to get there), and lastly, the future (talking about hopes and fears requires the most rapport). To allow for surprises, it is best to move from very general questions to more particular questions only later in the interview. This ensures that respondents have the freedom to bring up the topics that are relevant to them rather than feel like they are constrained to answer you narrowly. For example, refrain from asking about particular emotions until these have come up previously—don’t lead with them. Often, your more particular questions will emerge only during the course of the interview, tailored to what is emerging in conversation.

Once you have a set of questions, read through them aloud and imagine you are being asked the same questions. Does the set of questions have a natural flow? Would you be willing to answer the very first question to a total stranger? Does your sequence establish facts and experiences before moving on to opinions and values? Did you include prefatory statements, where necessary; transitions; and other announcements? These can be as simple as “Hey, we talked a lot about your experiences as a barista while in college.… Now I am turning to something completely different: how you managed friendships in college.” That is an abrupt transition, but it has been softened by your acknowledgment of that.

Probes and Flexibility

Once you have the interview guide, you will also want to leave room for probes and follow-up questions. As in the sample probe included here, you can write out the obvious probes and follow-up questions in advance. You might not need them, as your respondent might anticipate them and include full responses to the original question. Or you might need to tailor them to how your respondent answered the question. Some common probes and follow-up questions include asking for more details (When did that happen? Who else was there?), asking for elaboration (Could you say more about that?), asking for clarification (Does that mean what I think it means or something else? I understand what you mean, but someone else reading the transcript might not), and asking for contrast or comparison (How did this experience compare with last year’s event?). “Probing is a skill that comes from knowing what to look for in the interview, listening carefully to what is being said and what is not said, and being sensitive to the feedback needs of the person being interviewed” ( Patton 2002:374 ). It takes work! And energy. I and many other interviewers I know report feeling emotionally and even physically drained after conducting an interview. You are tasked with active listening and rearranging your interview guide as needed on the fly. If you only ask the questions written down in your interview guide with no deviations, you are doing it wrong. [2]

The Final Question

Every interview guide should include a very open-ended final question that allows for the respondent to say whatever it is they have been dying to tell you but you’ve forgotten to ask. About half the time they are tired too and will tell you they have nothing else to say. But incredibly, some of the most honest and complete responses take place here, at the end of a long interview. You have to realize that the person being interviewed is often discovering things about themselves as they talk to you and that this process of discovery can lead to new insights for them. Making space at the end is therefore crucial. Be sure you convey that you actually do want them to tell you more, that the offer of “anything else?” is not read as an empty convention where the polite response is no. Here is where you can pull from that active listening and tailor the final question to the particular person. For example, “I’ve asked you a lot of questions about what it was like to live through that wildfire. I’m wondering if there is anything I’ve forgotten to ask, especially because I haven’t had that experience myself” is a much more inviting final question than “Great. Anything you want to add?” It’s also helpful to convey to the person that you have the time to listen to their full answer, even if the allotted time is at the end. After all, there are no more questions to ask, so the respondent knows exactly how much time is left. Do them the courtesy of listening to them!

Conducting the Interview

Once you have your interview guide, you are on your way to conducting your first interview. I always practice my interview guide with a friend or family member. I do this even when the questions don’t make perfect sense for them, as it still helps me realize which questions make no sense, are poorly worded (too academic), or don’t follow sequentially. I also practice the routine I will use for interviewing, which goes something like this:

- Introduce myself and reintroduce the study

- Provide consent form and ask them to sign and retain/return copy

- Ask if they have any questions about the study before we begin

- Ask if I can begin recording

- Ask questions (from interview guide)

- Turn off the recording device

- Ask if they are willing to fill out my demographic questionnaire

- Collect questionnaire and, without looking at the answers, place in same folder as signed consent form

- Thank them and depart

A note on remote interviewing: Interviews have traditionally been conducted face-to-face in a private or quiet public setting. You don’t want a lot of background noise, as this will make transcriptions difficult. During the recent global pandemic, many interviewers, myself included, learned the benefits of interviewing remotely. Although face-to-face is still preferable for many reasons, Zoom interviewing is not a bad alternative, and it does allow more interviews across great distances. Zoom also includes automatic transcription, which significantly cuts down on the time it normally takes to convert our conversations into “data” to be analyzed. These automatic transcriptions are not perfect, however, and you will still need to listen to the recording and clarify and clean up the transcription. Nor do automatic transcriptions include notations of body language or change of tone, which you may want to include. When interviewing remotely, you will want to collect the consent form before you meet: ask them to read, sign, and return it as an email attachment. I think it is better to ask for the demographic questionnaire after the interview, but because some respondents may never return it then, it is probably best to ask for this at the same time as the consent form, in advance of the interview.

What should you bring to the interview? I would recommend bringing two copies of the consent form (one for you and one for the respondent), a demographic questionnaire, a manila folder in which to place the signed consent form and filled-out demographic questionnaire, a printed copy of your interview guide (I print with three-inch right margins so I can jot down notes on the page next to relevant questions), a pen, a recording device, and water.

After the interview, you will want to secure the signed consent form in a locked filing cabinet (if in print) or a password-protected folder on your computer. Using Excel or a similar program that allows tables/spreadsheets, create an identifying number for your interview that links to the consent form without using the name of your respondent. For example, let’s say that I conduct interviews with US politicians, and the first person I meet with is George W. Bush. I will assign the transcription the number “INT#001” and add it to the signed consent form. [3] The signed consent form goes into a locked filing cabinet, and I never use the name “George W. Bush” again. I take the information from the demographic sheet, open my Excel spreadsheet, and add the relevant information in separate columns for the row INT#001: White, male, Republican. When I interview Bill Clinton as my second interview, I include a second row: INT#002: White, male, Democrat. And so on. The only link to the actual name of the respondent and this information is the fact that the consent form (unavailable to anyone but me) has stamped on it the interview number.

Many students get very nervous before their first interview. Actually, many of us are always nervous before the interview! But do not worry—this is normal, and it does pass. Chances are, you will be pleasantly surprised at how comfortable it begins to feel. These “purposeful conversations” are often a delight for both participants. This is not to say that sometimes things go wrong. I often have my students practice several “bad scenarios” (e.g., a respondent that you cannot get to open up; a respondent who is too talkative and dominates the conversation, steering it away from the topics you are interested in; emotions that completely take over; or shocking disclosures you are ill-prepared to handle), but most of the time, things go quite well. Be prepared for the unexpected, but know that the reason interviews are so popular as a technique of data collection is that they are usually richly rewarding for both participants.

One thing that I stress to my methods students and remind myself about is that interviews are still conversations between people. If there’s something you might feel uncomfortable asking someone about in a “normal” conversation, you will likely also feel a bit of discomfort asking it in an interview. Maybe more importantly, your respondent may feel uncomfortable. Social research—especially about inequality—can be uncomfortable. And it’s easy to slip into an abstract, intellectualized, or removed perspective as an interviewer. This is one reason trying out interview questions is important. Another is that sometimes the question sounds good in your head but doesn’t work as well out loud in practice. I learned this the hard way when a respondent asked me how I would answer the question I had just posed, and I realized that not only did I not really know how I would answer it, but I also wasn’t quite as sure I knew what I was asking as I had thought.

—Elizabeth M. Lee, Associate Professor of Sociology at Saint Joseph’s University, author of Class and Campus Life , and co-author of Geographies of Campus Inequality

How Many Interviews?

Your research design has included a targeted number of interviews and a recruitment plan (see chapter 5). Follow your plan, but remember that “ saturation ” is your goal. You interview as many people as you can until you reach a point at which you are no longer surprised by what they tell you. This means not that no one after your first twenty interviews will have surprising, interesting stories to tell you but rather that the picture you are forming about the phenomenon of interest to you from a research perspective has come into focus, and none of the interviews are substantially refocusing that picture. That is when you should stop collecting interviews. Note that to know when you have reached this, you will need to read your transcripts as you go. More about this in chapters 18 and 19.

Your Final Product: The Ideal Interview Transcript

A good interview transcript will demonstrate a subtly controlled conversation by the skillful interviewer. In general, you want to see replies that are about one paragraph long, not short sentences and not running on for several pages. Although it is sometimes necessary to follow respondents down tangents, it is also often necessary to pull them back to the questions that form the basis of your research study. This is not really a free conversation, although it may feel like that to the person you are interviewing.

Final Tips from an Interview Master

Annette Lareau is arguably one of the masters of the trade. In Listening to People , she provides several guidelines for good interviews and then offers a detailed example of an interview gone wrong and how it could be addressed (please see the “Further Readings” at the end of this chapter). Here is an abbreviated version of her set of guidelines: (1) interview respondents who are experts on the subjects of most interest to you (as a corollary, don’t ask people about things they don’t know); (2) listen carefully and talk as little as possible; (3) keep in mind what you want to know and why you want to know it; (4) be a proactive interviewer (subtly guide the conversation); (5) assure respondents that there aren’t any right or wrong answers; (6) use the respondent’s own words to probe further (this both allows you to accurately identify what you heard and pushes the respondent to explain further); (7) reuse effective probes (don’t reinvent the wheel as you go—if repeating the words back works, do it again and again); (8) focus on learning the subjective meanings that events or experiences have for a respondent; (9) don’t be afraid to ask a question that draws on your own knowledge (unlike trial lawyers who are trained never to ask a question for which they don’t already know the answer, sometimes it’s worth it to ask risky questions based on your hypotheses or just plain hunches); (10) keep thinking while you are listening (so difficult…and important); (11) return to a theme raised by a respondent if you want further information; (12) be mindful of power inequalities (and never ever coerce a respondent to continue the interview if they want out); (13) take control with overly talkative respondents; (14) expect overly succinct responses, and develop strategies for probing further; (15) balance digging deep and moving on; (16) develop a plan to deflect questions (e.g., let them know you are happy to answer any questions at the end of the interview, but you don’t want to take time away from them now); and at the end, (17) check to see whether you have asked all your questions. You don’t always have to ask everyone the same set of questions, but if there is a big area you have forgotten to cover, now is the time to recover ( Lareau 2021:93–103 ).

Sample: Demographic Questionnaire

ASA Taskforce on First-Generation and Working-Class Persons in Sociology – Class Effects on Career Success

Supplementary Demographic Questionnaire

Thank you for your participation in this interview project. We would like to collect a few pieces of key demographic information from you to supplement our analyses. Your answers to these questions will be kept confidential and stored by ID number. All of your responses here are entirely voluntary!

What best captures your race/ethnicity? (please check any/all that apply)

- White (Non Hispanic/Latina/o/x)

- Black or African American

- Hispanic, Latino/a/x of Spanish

- Asian or Asian American

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Middle Eastern or North African

- Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- Other : (Please write in: ________________)

What is your current position?

- Grad Student

- Full Professor

Please check any and all of the following that apply to you:

- I identify as a working-class academic

- I was the first in my family to graduate from college

- I grew up poor

What best reflects your gender?

- Transgender female/Transgender woman

- Transgender male/Transgender man

- Gender queer/ Gender nonconforming

Anything else you would like us to know about you?

Example: Interview Guide

In this example, follow-up prompts are italicized. Note the sequence of questions. That second question often elicits an entire life history , answering several later questions in advance.

Introduction Script/Question

Thank you for participating in our survey of ASA members who identify as first-generation or working-class. As you may have heard, ASA has sponsored a taskforce on first-generation and working-class persons in sociology and we are interested in hearing from those who so identify. Your participation in this interview will help advance our knowledge in this area.

- The first thing we would like to as you is why you have volunteered to be part of this study? What does it mean to you be first-gen or working class? Why were you willing to be interviewed?

- How did you decide to become a sociologist?

- Can you tell me a little bit about where you grew up? ( prompts: what did your parent(s) do for a living? What kind of high school did you attend?)

- Has this identity been salient to your experience? (how? How much?)

- How welcoming was your grad program? Your first academic employer?

- Why did you decide to pursue sociology at the graduate level?

- Did you experience culture shock in college? In graduate school?

- Has your FGWC status shaped how you’ve thought about where you went to school? debt? etc?

- Were you mentored? How did this work (not work)? How might it?

- What did you consider when deciding where to go to grad school? Where to apply for your first position?

- What, to you, is a mark of career success? Have you achieved that success? What has helped or hindered your pursuit of success?

- Do you think sociology, as a field, cares about prestige?

- Let’s talk a little bit about intersectionality. How does being first-gen/working class work alongside other identities that are important to you?

- What do your friends and family think about your career? Have you had any difficulty relating to family members or past friends since becoming highly educated?

- Do you have any debt from college/grad school? Are you concerned about this? Could you explain more about how you paid for college/grad school? (here, include assistance from family, fellowships, scholarships, etc.)

- (You’ve mentioned issues or obstacles you had because of your background.) What could have helped? Or, who or what did? Can you think of fortuitous moments in your career?

- Do you have any regrets about the path you took?

- Is there anything else you would like to add? Anything that the Taskforce should take note of, that we did not ask you about here?

Further Readings

Britten, Nicky. 1995. “Qualitative Interviews in Medical Research.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 31(6999):251–253. A good basic overview of interviewing particularly useful for students of public health and medical research generally.

Corbin, Juliet, and Janice M. Morse. 2003. “The Unstructured Interactive Interview: Issues of Reciprocity and Risks When Dealing with Sensitive Topics.” Qualitative Inquiry 9(3):335–354. Weighs the potential benefits and harms of conducting interviews on topics that may cause emotional distress. Argues that the researcher’s skills and code of ethics should ensure that the interviewing process provides more of a benefit to both participant and researcher than a harm to the former.

Gerson, Kathleen, and Sarah Damaske. 2020. The Science and Art of Interviewing . New York: Oxford University Press. A useful guidebook/textbook for both undergraduates and graduate students, written by sociologists.

Kvale, Steiner. 2007. Doing Interviews . London: SAGE. An easy-to-follow guide to conducting and analyzing interviews by psychologists.

Lamont, Michèle, and Ann Swidler. 2014. “Methodological Pluralism and the Possibilities and Limits of Interviewing.” Qualitative Sociology 37(2):153–171. Written as a response to various debates surrounding the relative value of interview-based studies and ethnographic studies defending the particular strengths of interviewing. This is a must-read article for anyone seriously engaging in qualitative research!

Pugh, Allison J. 2013. “What Good Are Interviews for Thinking about Culture? Demystifying Interpretive Analysis.” American Journal of Cultural Sociology 1(1):42–68. Another defense of interviewing written against those who champion ethnographic methods as superior, particularly in the area of studying culture. A classic.

Rapley, Timothy John. 2001. “The ‘Artfulness’ of Open-Ended Interviewing: Some considerations in analyzing interviews.” Qualitative Research 1(3):303–323. Argues for the importance of “local context” of data production (the relationship built between interviewer and interviewee, for example) in properly analyzing interview data.

Weiss, Robert S. 1995. Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies . New York: Simon and Schuster. A classic and well-regarded textbook on interviewing. Because Weiss has extensive experience conducting surveys, he contrasts the qualitative interview with the survey questionnaire well; particularly useful for those trained in the latter.

- I say “normally” because how people understand their various identities can itself be an expansive topic of inquiry. Here, I am merely talking about collecting otherwise unexamined demographic data, similar to how we ask people to check boxes on surveys. ↵

- Again, this applies to “semistructured in-depth interviewing.” When conducting standardized questionnaires, you will want to ask each question exactly as written, without deviations! ↵

- I always include “INT” in the number because I sometimes have other kinds of data with their own numbering: FG#001 would mean the first focus group, for example. I also always include three-digit spaces, as this allows for up to 999 interviews (or, more realistically, allows for me to interview up to one hundred persons without having to reset my numbering system). ↵

A method of data collection in which the researcher asks the participant questions; the answers to these questions are often recorded and transcribed verbatim. There are many different kinds of interviews - see also semistructured interview , structured interview , and unstructured interview .

A document listing key questions and question areas for use during an interview. It is used most often for semi-structured interviews. A good interview guide may have no more than ten primary questions for two hours of interviewing, but these ten questions will be supplemented by probes and relevant follow-ups throughout the interview. Most IRBs require the inclusion of the interview guide in applications for review. See also interview and semi-structured interview .

A data-collection method that relies on casual, conversational, and informal interviewing. Despite its apparent conversational nature, the researcher usually has a set of particular questions or question areas in mind but allows the interview to unfold spontaneously. This is a common data-collection technique among ethnographers. Compare to the semi-structured or in-depth interview .

A form of interview that follows a standard guide of questions asked, although the order of the questions may change to match the particular needs of each individual interview subject, and probing “follow-up” questions are often added during the course of the interview. The semi-structured interview is the primary form of interviewing used by qualitative researchers in the social sciences. It is sometimes referred to as an “in-depth” interview. See also interview and interview guide .

The cluster of data-collection tools and techniques that involve observing interactions between people, the behaviors, and practices of individuals (sometimes in contrast to what they say about how they act and behave), and cultures in context. Observational methods are the key tools employed by ethnographers and Grounded Theory .

Follow-up questions used in a semi-structured interview to elicit further elaboration. Suggested prompts can be included in the interview guide to be used/deployed depending on how the initial question was answered or if the topic of the prompt does not emerge spontaneously.

A form of interview that follows a strict set of questions, asked in a particular order, for all interview subjects. The questions are also the kind that elicits short answers, and the data is more “informative” than probing. This is often used in mixed-methods studies, accompanying a survey instrument. Because there is no room for nuance or the exploration of meaning in structured interviews, qualitative researchers tend to employ semi-structured interviews instead. See also interview.

The point at which you can conclude data collection because every person you are interviewing, the interaction you are observing, or content you are analyzing merely confirms what you have already noted. Achieving saturation is often used as the justification for the final sample size.

An interview variant in which a person’s life story is elicited in a narrative form. Turning points and key themes are established by the researcher and used as data points for further analysis.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Topic Guides

- Research Methods Guide

- Interview Research

Research Methods Guide: Interview Research

- Introduction

- Research Design & Method

- Survey Research

- Data Analysis

- Resources & Consultation

Tutorial Videos: Interview Method

Interview as a Method for Qualitative Research

Goals of Interview Research

- Preferences

- They help you explain, better understand, and explore research subjects' opinions, behavior, experiences, phenomenon, etc.

- Interview questions are usually open-ended questions so that in-depth information will be collected.

Mode of Data Collection

There are several types of interviews, including:

- Face-to-Face

- Online (e.g. Skype, Googlehangout, etc)

FAQ: Conducting Interview Research

What are the important steps involved in interviews?

- Think about who you will interview

- Think about what kind of information you want to obtain from interviews

- Think about why you want to pursue in-depth information around your research topic

- Introduce yourself and explain the aim of the interview

- Devise your questions so interviewees can help answer your research question

- Have a sequence to your questions / topics by grouping them in themes

- Make sure you can easily move back and forth between questions / topics

- Make sure your questions are clear and easy to understand

- Do not ask leading questions

- Do you want to bring a second interviewer with you?

- Do you want to bring a notetaker?

- Do you want to record interviews? If so, do you have time to transcribe interview recordings?

- Where will you interview people? Where is the setting with the least distraction?

- How long will each interview take?

- Do you need to address terms of confidentiality?

Do I have to choose either a survey or interviewing method?

No. In fact, many researchers use a mixed method - interviews can be useful as follow-up to certain respondents to surveys, e.g., to further investigate their responses.

Is training an interviewer important?

Yes, since the interviewer can control the quality of the result, training the interviewer becomes crucial. If more than one interviewers are involved in your study, it is important to have every interviewer understand the interviewing procedure and rehearse the interviewing process before beginning the formal study.

- << Previous: Survey Research

- Next: Data Analysis >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2023 10:42 AM

Research Methodologies: Research Instruments

- Research Methodology Basics

- Research Instruments

- Types of Research Methodologies

Header Image

Types of Research Instruments

A research instrument is a tool you will use to help you collect, measure and analyze the data you use as part of your research. The choice of research instrument will usually be yours to make as the researcher and will be whichever best suits your methodology.

There are many different research instruments you can use in collecting data for your research:

- Interviews (either as a group or one-on-one). You can carry out interviews in many different ways. For example, your interview can be structured, semi-structured, or unstructured. The difference between them is how formal the set of questions is that is asked of the interviewee. In a group interview, you may choose to ask the interviewees to give you their opinions or perceptions on certain topics.

- Surveys (online or in-person). In survey research, you are posing questions in which you ask for a response from the person taking the survey. You may wish to have either free-answer questions such as essay style questions, or you may wish to use closed questions such as multiple choice. You may even wish to make the survey a mixture of both.

- Focus Groups. Similar to the group interview above, you may wish to ask a focus group to discuss a particular topic or opinion while you make a note of the answers given.

- Observations. This is a good research instrument to use if you are looking into human behaviors. Different ways of researching this include studying the spontaneous behavior of participants in their everyday life, or something more structured. A structured observation is research conducted at a set time and place where researchers observe behavior as planned and agreed upon with participants.

These are the most common ways of carrying out research, but it is really dependent on your needs as a researcher and what approach you think is best to take. It is also possible to combine a number of research instruments if this is necessary and appropriate in answering your research problem.

Data Collection

How to Collect Data for Your Research This article covers different ways of collecting data in preparation for writing a thesis.

- << Previous: Research Methodology Basics

- Next: Types of Research Methodologies >>

- Last Updated: Sep 27, 2022 12:28 PM

- URL: https://paperpile.libguides.com/research-methodologies

Research Interviews: An effective and insightful way of data collection

Research interviews play a pivotal role in collecting data for various academic, scientific, and professional endeavors. They provide researchers with an opportunity to delve deep into the thoughts, experiences, and perspectives of an individual, thus enabling a comprehensive understanding of complex phenomena. It is important for researchers to design an effective and insightful method of data collection on a particular topic. A research interview is typically a two-person meeting conducted to collect information on a certain topic. It is a qualitative data collection method to gain primary information.

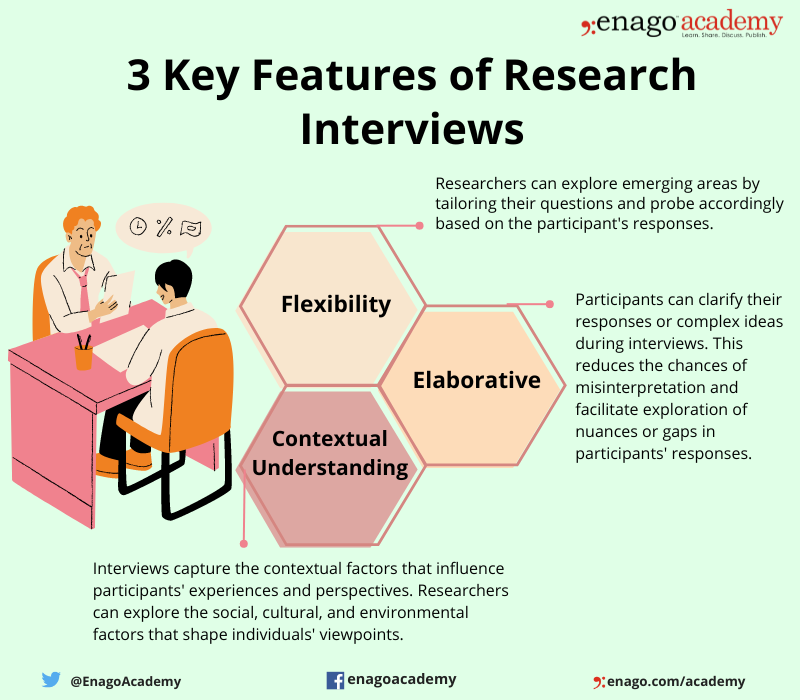

The three key features of a research interview are as follows:

Table of Contents

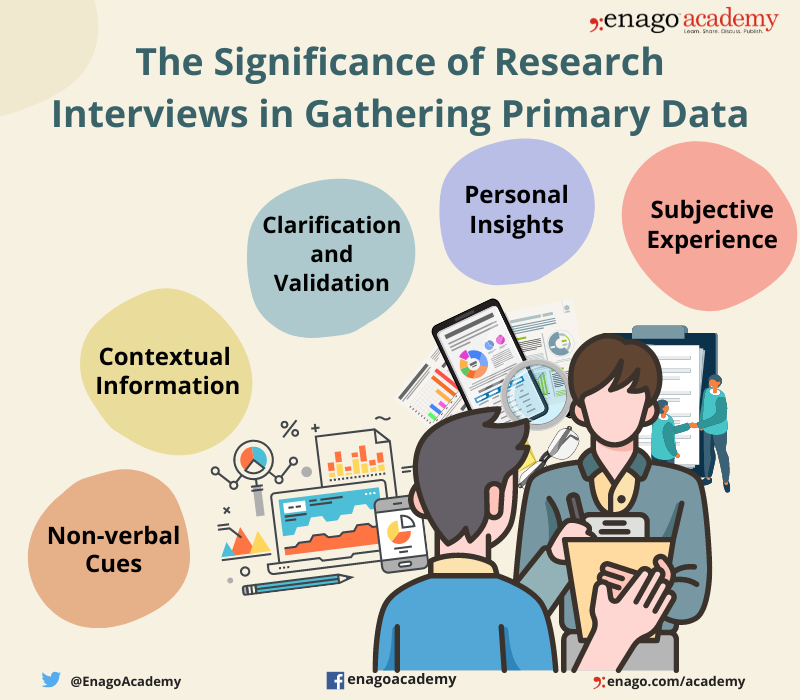

The Significance of Research Interviews in Gathering Primary Data

The role of research interviews in gathering first-hand information is invaluable. Additionally, they allow researchers to interact directly with participants, enabling them to collect unfiltered primary data.

1. Subjective Experience

Research interviews facilitate in-depth exploration of a research topic. Thus, by engaging in one-to-one conversation with participants, researchers can delve into the nuances and complexities of their experiences, perspectives, and opinions. This allows comprehensive understanding of the research subject that may not be possible through other methods. Also, research interviews offer the unique advantage of capturing subjective experiences through personal narratives. Moreover, participants can express their thoughts, feelings, and beliefs, which add depth to the findings.

2. Personal Insights

Research interviews offer an opportunity for participants to share their views and opinions on the objective they are being interviewed for. Furthermore, participants can express their thoughts and experiences, providing rich qualitative data . Consequently, these personal narratives add a human element to the research, thus enhancing the understanding of the topic from the participants’ perspectives. Research interviews offer the opportunity to uncover unanticipated insights or emerging themes. Additionally, open-ended questions and active listening can help the researchers to identify new perspectives, ideas, or patterns that may not have been initially considered. As a result, these factors can lead to new avenues for exploration.

3. Clarification and Validation

Researchers can clarify participants’ responses and validate their understanding during an interview. This ensures accurate data collection and interpretation. Additionally, researchers can probe deeper into participants’ statements and seek clarification on any ambiguity in the information.

4. Contextual Information

Research interviews allow researchers to gather contextual information that offers a comprehensive understanding of the research topic. Additionally, participants can provide insights into the social, cultural, or environmental factors that shape their experiences, behaviors, and beliefs. This contextual information helps researchers place the data in a broader context and facilitates a more nuanced analysis.

5. Non-verbal Cues

In addition to verbal responses, research interviews allow researchers to observe non-verbal cues such as body language, facial expressions, and tone of voice. Additionally, non-verbal cues can convey information, such as emotions, attitudes, or levels of comfort. Furthermore, integrating non-verbal cues with verbal responses provides a more holistic understanding of participants’ experiences and enriches the data collection process.

Research interviews offer several advantages, making them a reliable tool for collecting information. However, choosing the right type of research interview is essential for collecting useful data.

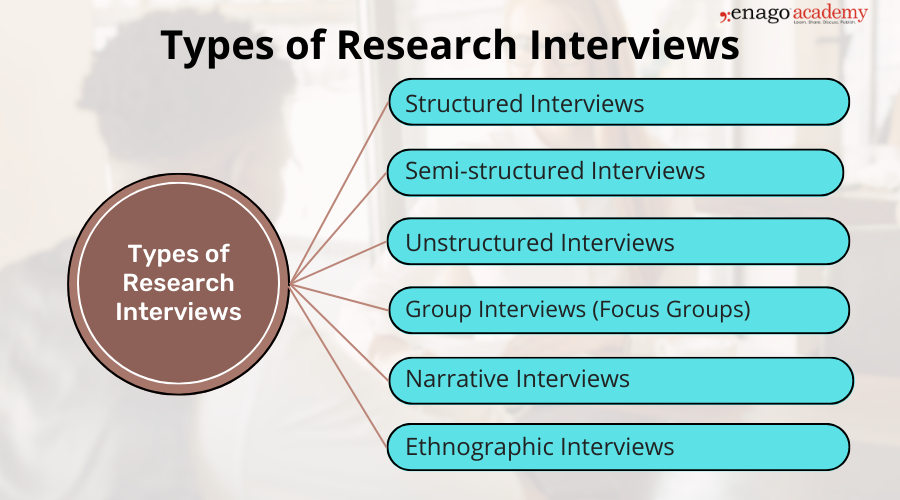

Types of Research Interviews

There are several types of research interviews that researchers can use based on their research goals , the nature of their study, and the data they aim to collect. Here are some common types of research interviews:

1. Structured Interviews

- Structured interviews are standardized and follow a fixed format.

- Therefore, these interviews have a pre-determined set of questions.

- All the participants are asked the same set of questions in the same order.

- Therefore, this type of interview facilitates standardization and allows easy comparison and quantitative analysis of responses.

- As a result, structured interviews are used in surveys or studies which aims for a high level of standardization and comparability.

2. Semi-structured Interviews

- Semi-structured interviews offer a flexible framework by combining pre-determined questions.

- So, this gives an opportunity for follow-up questions and open-ended discussions.

- Researchers have a list of core questions but can adapt the interview depending on the participant’s responses.

- Consequently, this allows for in-depth exploration while maintaining some level of consistency across interviews.

- As a result, semi-structured interviews are widely used in qualitative research, where content-rich data is desired.

3. Unstructured Interviews

- Unstructured interviews provide the greatest flexibility and freedom in the interview process.

- This type do not have a pre-determined set of questions.

- Thus, the conversation flows naturally based on the participant’s responses and the researcher’s interests.

- Moreover, this type of interview allows for open-ended exploration and encourages participants to share their experiences, thoughts, and perspectives freely.

- Unstructured interviews useful to explore new or complex research topics, with limited preconceived questions.

4. Group Interviews (Focus Groups)

- Group interviews involve multiple participants who engage in a facilitated discussion on a specific topic.

- This format allows the interaction and exchange of ideas among participants, generating a group dynamic.

- Therefore, group interviews are beneficial for capturing diverse perspectives, and generating collective insights.

- They are often used in market research, social sciences, or studies demanding shared experiences.

5. Narrative Interviews

- Narrative interviews focus on eliciting participants’ personal stories, views, experiences, and narratives. Researchers aim to look into the individual’s life journey.

- As a result, this type of interview allows participants to construct and share their own narratives, providing rich qualitative data.

- Qualitative research, oral history, or studies focusing on individual experiences and identities uses narrative interviews.

6. Ethnographic Interviews

- Ethnographic interviews are conducted within the context of ethnographic research, where researchers immerse themselves in a specific social or cultural setting.

- These interviews aim to understand participants’ experiences, beliefs, and practices within their cultural context, thereby understanding diversity in different ethnic groups.

- Furthermore, ethnographic interviews involve building rapport, observing the participants’ daily lives, and engaging in conversations that capture the nuances of the culture under study.

It must be noted that these interview types are not mutually exclusive. Therefore, researchers often employ a combination of approaches to gather the most comprehensive data for their research. The choice of interview type depends on the research objectives and the nature of the research topic.

Steps of Conducting a Research Interview

Research interviews offer several benefits, and thus careful planning and execution of the entire process are important to gather in-depth information from the participants. While conducting an interview, it is essential to know the necessary steps to follow for ensuring success. The steps to conduct a research interview are as follows:

- Identify the objectives and understand the goals

- Select an appropriate interview format

- Organize the necessary materials for the interview

- Understand the questions to be addressed

- Analyze the demographics of interviewees

- Select the interviewees

- Design the interview questions to gather sufficient information

- Schedule the interview

- Explain the purpose of the interview

- Analyze the interviewee based on his/her responses

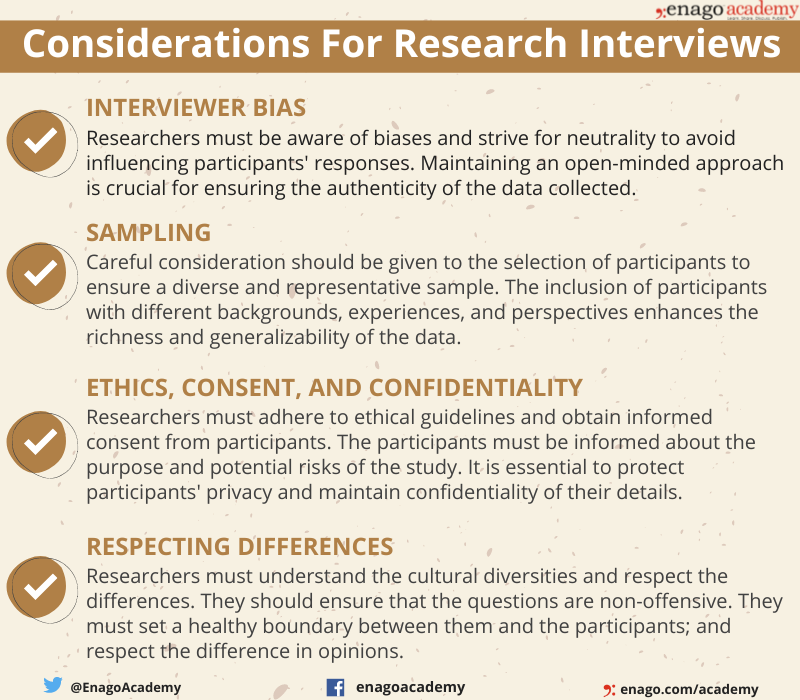

Considerations for Research Interviews

Since the flexible nature of research interviews makes them an invaluable tool for data collection, researchers must consider certain factors to make the process effective. They should avoid bias and preconceived notion against the participants. Furthermore, researchers must comply with ethical considerations and respect the cultural differences between them and the participants. Also, they should ensure careful tailoring of the questions to avoid making them offensive or derogatory. The interviewers must respect the privacy of the participants and ensure the confidentiality of their details.

By ensuring due diligence of these considerations associated with research interviews, researchers can maximize the validity and reliability of the collected data, leading to robust and meaningful research outcomes.

Have you ever conducted a research interview? What was your experience? What factors did you consider when conducting a research interview? Share it with researchers worldwide by submitting your thought piece on Enago Academy’s Open Blogging Platform .

Frequently Asked Questions

• Identify the objectives of the interview • State and explain the purpose of the interview • Select an appropriate interview format • Organize the necessary materials for the Interview • Check the demographics of the participants • Select the Interviewees or the participants • Prepare the list of questions to gather maximum useful data from the participants • Schedule the Interview • Analyze the participant based on his/ her Responses

Interviews are important in research as it helps to gather elaborative first-hand information. It helps to draw conclusions from the non-verbal views and personal experiences. It reduces the ambiguity of data through detailed discussions.

The advantages of research interviews are: • It offers first-hand information • Offers detailed assessment which can result in elaborate conclusions • It is easy to conduct • Provides non-verbal cues The disadvantages of research interviews are: • There is a risk of personal bias • It can be time consuming • The outcomes might be unpredictable

The difference between structured and unstructured interview are: • Structured interviews have well-structured questions in a pre-determined order; while unstructured interviews are flexible and do not have a pre-planned set of questions. • Structured interview is more detailed; while unstructured interviews are exploratory in nature. • Structured interview is easier to replicate as compared to unstructured interview.

Focus groups is a group of multiple participants engaging in a facilitated discussion on a specific topic. This format allows for interaction and exchange of ideas among participants.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Industry News

- Trending Now

Breaking Barriers: Sony and Nature unveil “Women in Technology Award”

Sony Group Corporation and the prestigious scientific journal Nature have collaborated to launch the inaugural…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

- Promoting Research

Plain Language Summary — Communicating your research to bridge the academic-lay gap

Science can be complex, but does that mean it should not be accessible to the…

Science under Surveillance: Journals adopt advanced AI to uncover image manipulation

Journals are increasingly turning to cutting-edge AI tools to uncover deceitful images published in manuscripts.…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Demystifying the Role of Confounding Variables in Research

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Qualitative Data Collection Tools Design, Development, and Applications

- Felice D. Billups - Johnson & Wales University, USA

- Description

Qualitative Data Collection Tools is a new and unique supplementary text that will guide students and new researchers to design, develop, pilot, and employ qualitative tools in order to collect qualitative data. An often-omitted subject in general qualitative textbooks, qualitative tools form the backbone of the data collection process. Students and new researchers are frequently left to create their own qualitative tools from scratch, an unnecessary hurdle in the qualitative research design process. Author Felice D. Billups has used her experience as a qualitative researcher, and in teaching and advising students about qualitative research, to develop the templates in this book as a starting point for readers conducting original qualitative research. The author briefly describes each method of data collection and offers readers suggestions for using and adapting the qualitative instrument templates within the text. Templates of interview protocols, focus group moderator guides, content analysis tools, document analysis tools, reflective questionnaires, diary and journal logs, and observational rubrics give the reader either a cut-and-paste solution for their own research or a starting point to design their own personalized qualitative tools. The first three chapters illuminate the qualitative data collection process and the role each type of qualitative tool plays in that process. The next six chapters provide detailed guides and numerous templates for each qualitative data collection method, covering interviews, focus groups, conversation and discourse analysis, observations, document analysis, field notes, journaling, and other reflective practices. A final chapter pulls together the multifaceted nature of qualitative research design and connects each tool back to the methodology to ensure trustworthiness and rigor in the data collection and instrument development process. Exemplars populate the appendices, offering readers concrete inspiration for ways to use and adapt the tools provided. If you have ever puzzled over how to best to design qualitative tools in order to guide and structure your qualitative data collection, or if you are embarking on your first qualitative study, Qualitative Data Collection Tools will give you a practical starting point to help make your qualitative data collection process easier and more organized.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

I think that the more exposure that students have to instrumentation the more informed that can be when they build their own research studies.

[This text] offers a rich and much-needed perspective in the field of qualitative research.

A comprehensive guide for the novice and even intermediate qualitative researcher. I highly recommend this easy-to-follow textbook for anyone considering a qualitative study.

This new book fills a dire need in qualitative research--effectively and rigorously designing qualitative interview instruments and observation and artifact rubrics. (The author) has skillfully woven together necessary elements of qualitative design, research strategies, and research question development in order for researchers to operationalize their curiosities into successful, effective, and ethical research studies. I am particularly taken by the tone of the book. (The author) has written a book that challenges yet scaffolds readers to produce qualitative research studies with integrity and rigor.

This is a very practical text for doctoral students learning research, in particular for those doctoral students in professional non-traditional doctoral degree programs who have never been exposed to the process of conducting qualitative research. The text brings students through the journey of qualitative data collection and provides a how-to approach to qualitative methodology.

Practical, clear and concise, and has lots of templates for new researchers

It depends on the students research design- qualitative research design I have recommended it to student

This is a great resource

A valuable text for under and post graduates and for early career researchers. I would have liked to see a little more on the various uses of observations but otherwise a comprehensive text. Thank you.

- Covers an often-omitted subject in general qualitative textbook

- Benefits from the extensive qualitative research experience of its author

- Provides starting point templates for readers conducting original qualitative research

- Offers readers suggestions for using and adapting the qualitative instrument templates

- Ties each template back to methods and methodology to ensure trustworthiness and rigor

- Provides templates of interview protocols, focus group moderator guides, content analysis tools, document analysis tools, reflective questionnaires, diary and journal logs, and observational rubrics

- Gives the reader either a cut-and-paste solution for their own research or a starting point to design their own personalized qualitative tools.

Sample Materials & Chapters

Chapter 1. The Qualitative Data Collection Cycle

Chapter 6. Focus Group Moderator Guides

Chapter 2. Using the Research Question to Guide Qualitative Data Collection Tool

For instructors

Select a purchasing option, related products.

This title is also available on SAGE Research Methods , the ultimate digital methods library. If your library doesn’t have access, ask your librarian to start a trial .

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 05 October 2018

Interviews and focus groups in qualitative research: an update for the digital age

- P. Gill 1 &

- J. Baillie 2

British Dental Journal volume 225 , pages 668–672 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

27k Accesses

48 Citations

20 Altmetric

Metrics details

Highlights that qualitative research is used increasingly in dentistry. Interviews and focus groups remain the most common qualitative methods of data collection.

Suggests the advent of digital technologies has transformed how qualitative research can now be undertaken.

Suggests interviews and focus groups can offer significant, meaningful insight into participants' experiences, beliefs and perspectives, which can help to inform developments in dental practice.

Qualitative research is used increasingly in dentistry, due to its potential to provide meaningful, in-depth insights into participants' experiences, perspectives, beliefs and behaviours. These insights can subsequently help to inform developments in dental practice and further related research. The most common methods of data collection used in qualitative research are interviews and focus groups. While these are primarily conducted face-to-face, the ongoing evolution of digital technologies, such as video chat and online forums, has further transformed these methods of data collection. This paper therefore discusses interviews and focus groups in detail, outlines how they can be used in practice, how digital technologies can further inform the data collection process, and what these methods can offer dentistry.

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

Interviews in the social sciences

Principal component analysis

Introduction.

Traditionally, research in dentistry has primarily been quantitative in nature. 1 However, in recent years, there has been a growing interest in qualitative research within the profession, due to its potential to further inform developments in practice, policy, education and training. Consequently, in 2008, the British Dental Journal (BDJ) published a four paper qualitative research series, 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 to help increase awareness and understanding of this particular methodological approach.

Since the papers were originally published, two scoping reviews have demonstrated the ongoing proliferation in the use of qualitative research within the field of oral healthcare. 1 , 6 To date, the original four paper series continue to be well cited and two of the main papers remain widely accessed among the BDJ readership. 2 , 3 The potential value of well-conducted qualitative research to evidence-based practice is now also widely recognised by service providers, policy makers, funding bodies and those who commission, support and use healthcare research.

Besides increasing standalone use, qualitative methods are now also routinely incorporated into larger mixed method study designs, such as clinical trials, as they can offer additional, meaningful insights into complex problems that simply could not be provided by quantitative methods alone. Qualitative methods can also be used to further facilitate in-depth understanding of important aspects of clinical trial processes, such as recruitment. For example, Ellis et al . investigated why edentulous older patients, dissatisfied with conventional dentures, decline implant treatment, despite its established efficacy, and frequently refuse to participate in related randomised clinical trials, even when financial constraints are removed. 7 Through the use of focus groups in Canada and the UK, the authors found that fears of pain and potential complications, along with perceived embarrassment, exacerbated by age, are common reasons why older patients typically refuse dental implants. 7

The last decade has also seen further developments in qualitative research, due to the ongoing evolution of digital technologies. These developments have transformed how researchers can access and share information, communicate and collaborate, recruit and engage participants, collect and analyse data and disseminate and translate research findings. 8 Where appropriate, such technologies are therefore capable of extending and enhancing how qualitative research is undertaken. 9 For example, it is now possible to collect qualitative data via instant messaging, email or online/video chat, using appropriate online platforms.

These innovative approaches to research are therefore cost-effective, convenient, reduce geographical constraints and are often useful for accessing 'hard to reach' participants (for example, those who are immobile or socially isolated). 8 , 9 However, digital technologies are still relatively new and constantly evolving and therefore present a variety of pragmatic and methodological challenges. Furthermore, given their very nature, their use in many qualitative studies and/or with certain participant groups may be inappropriate and should therefore always be carefully considered. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to provide a detailed explication regarding the use of digital technologies in qualitative research, insight is provided into how such technologies can be used to facilitate the data collection process in interviews and focus groups.

In light of such developments, it is perhaps therefore timely to update the main paper 3 of the original BDJ series. As with the previous publications, this paper has been purposely written in an accessible style, to enhance readability, particularly for those who are new to qualitative research. While the focus remains on the most common qualitative methods of data collection – interviews and focus groups – appropriate revisions have been made to provide a novel perspective, and should therefore be helpful to those who would like to know more about qualitative research. This paper specifically focuses on undertaking qualitative research with adult participants only.

Overview of qualitative research

Qualitative research is an approach that focuses on people and their experiences, behaviours and opinions. 10 , 11 The qualitative researcher seeks to answer questions of 'how' and 'why', providing detailed insight and understanding, 11 which quantitative methods cannot reach. 12 Within qualitative research, there are distinct methodologies influencing how the researcher approaches the research question, data collection and data analysis. 13 For example, phenomenological studies focus on the lived experience of individuals, explored through their description of the phenomenon. Ethnographic studies explore the culture of a group and typically involve the use of multiple methods to uncover the issues. 14